Abstract

Targetoid Hemosiderotic Hemangioma, also known as Hobnail Hemangioma, is a lesion of vascular origin, probably lymphatic. The most common clinical feature is a solitary violaceous papule surrounded by a pale, thin area and a peripheral ecchymotic ring, simulating a target. Histopathologically, there is a biphasic pattern, with dilated vessels in the superficial dermis and pseudoangiosarcomatous pattern in the deep dermis, and endothelial cells with hobnail morphology. A simple excision is curative. We report a rare case of Targetoid Hemosiderotic Hemangioma.

Keywords: Hemangioma, Pathology, Vascular diseases

INTRODUCTION

Targetoid Hemosiderotic Hemangioma (THH), also known as Hobnail Hemangioma, is a vascular, benign solitary lesion of unknown origin, probably lymphatic, which affects young or middle-aged people.1-3 The term THH describes the clinical lesion that presents as a small violaceous papule surrounded by a pale, thin area and a peripheral ecchymotic ring.3 The term Hobnail Hemangioma, on the other hand, was proposed to describe a histological feature of the lesion: the hobnail appearance of the endothelial cell. We report a rare case of THH.1

CASE REPORT

A 29-year-old male patient, born and residing in São Paulo-SP, presented violaceous, targetoid lesions consisting of a papular center surrounded by a paler, intermediate area and a peripheral purpuric halo. The lesion measured about 3 x 2 cm, was located on the upper back and had been present for 1 year (Figure 1). An incisional biopsy of the lesion showed angiomatous proliferation in the dermis and nuclear atypia, suggesting a diagnosis of angiokeratoma or Kaposi's sarcoma (Figures 2-6). The diagnosis was made after review of the slide, which showed epidermis with mild acanthosis. In the superficial dermis, dilated vessel proliferation had an aspect compatible with lymphatic capillary, sometimes showing endothelial cells with a hobnail aspect, giving prominence to the lumens. More deeply, vascular spaces become sometimes slit-like, appearing to dissect through collagen bundles. Presence of extravasated erythrocytes and hemosiderin deposits at the periphery of the lesion. These findings, correlated with the clinical feature of targetoid lesion, allowed us to make the diagnosis of THH. The patient opted for a total removal of the lesion.

FIGURE 1.

Violaceous, targetoid lesion consisting of a papular center surrounded by a paler, intermediate area and a peripheral purpuric halo on the upper back

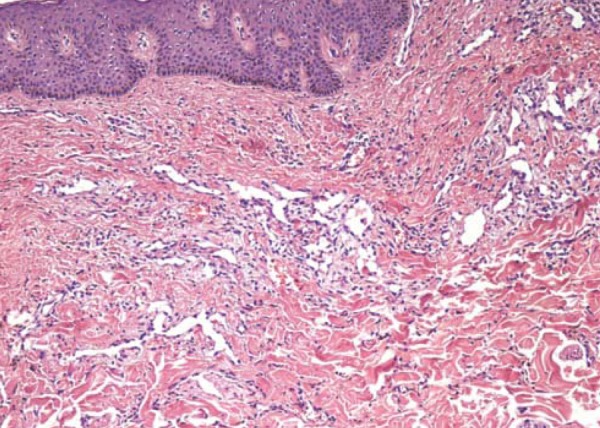

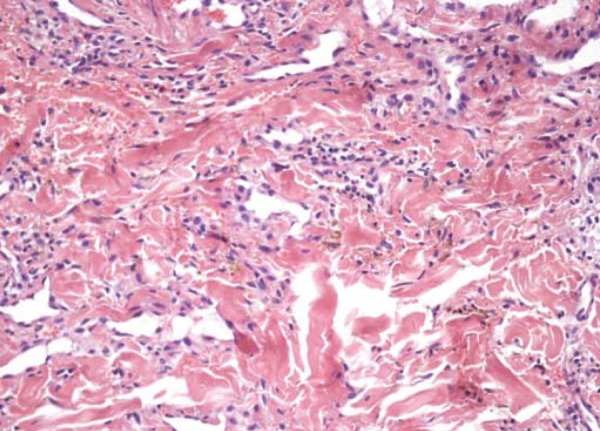

FIGURE 2.

100x. Dermal angiomatous proliferation with dilated vessels in the superficial dermis and dissecting collagen bundles in the middle and deep dermis

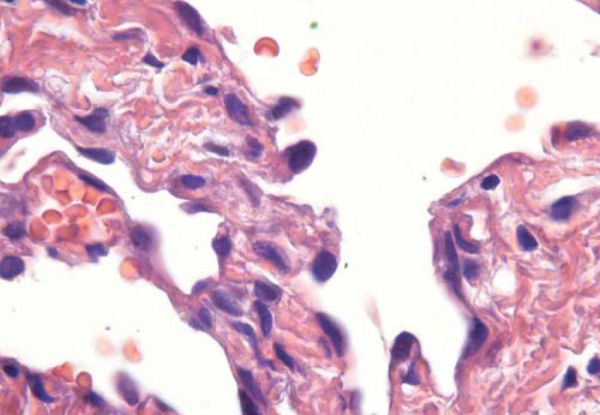

FIGURE 6.

1000x Detail of hobnail endothelial cells

DISCUSSION

THH was first described in 1988.3 Classically, it presents as a single, small, red-violaceous to brown targetoid lesion, surrounded by a hemorrhagic halo in the acute phase, and which can expand centrifugally. In later stages, the halo may disappear, leaving only the central papule.2-5 Some cases without targetoid formation have been reported.5 Young or middle aged individuals are more affected.2,4-7 There is no gender predominance.5 It is preferably located on the trunk or extremities.2,4-7

The wide variation in clinical appearance, especially in coloration, explains why this lesion may be clinically confused with hemangioma, dermatofibroma, reaction to insect sting, Kaposi's sarcoma, melanocytic nevus and melanoma.2-5 In these cases, dermoscopy is a useful tool that can aid in the differentiation of melanocytic lesions. Dermoscopy shows well-demarcated red or red-bluish lakes (depending on the extent of involvement in the dermis). Black macules may also be seen and represent hemorrhagic crusts.2

The exact pathogenesis of THH is unknown, although it has been postulated that trauma is one of the main causes for the targetoid appearance.3,5,7,8 Trauma could lead to the development of microshunts, in which the pressure of the capillaries would cause the filling of the lymph spaces of the lesion with erythrocytes, and contribute to the formation of aneurysmal microstructures.6 The obstruction of some efferent lymphatic vessels would result in inflammation, fibrosis and interstitial hemosiderin deposits.6,7 Hormones may also potentiate these tumors.9

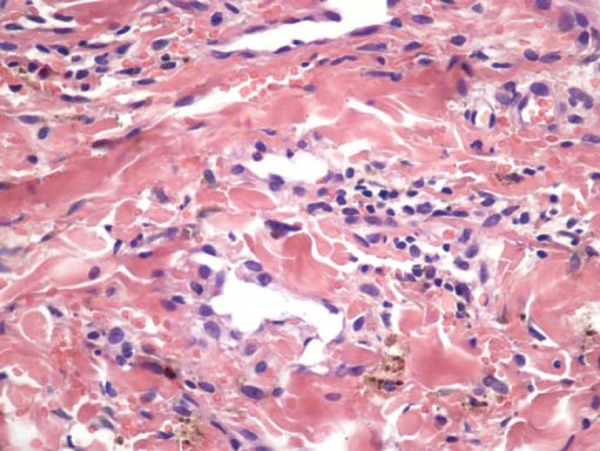

Histology varies according to the developmental stage in which the lesion was biopsied.1,3,10 In the initial stages, there is a biphasic pattern: in the papillary dermis, there are dilated vessels lined by a single layer of prominent epithelioid-like endothelial cells with solid intraluminal projections and hobnail appearance; and in the deep dermis, the vascular spaces are angulated and slit-like, resembling lymphatic vessels, which are concentrated around sweat glands, often forming small hemangiomatous nodules, dissecting the collagen bundles.3,10 Extensive extravasation of red blood cells, inflammatory lymphocytic aggregates and fibrin thrombi are present.3,4,10 In later stages, the vascular lumen appears collapsed and there is extensive deposition of hemosiderin in the stroma, as well as fibrosis.3,4

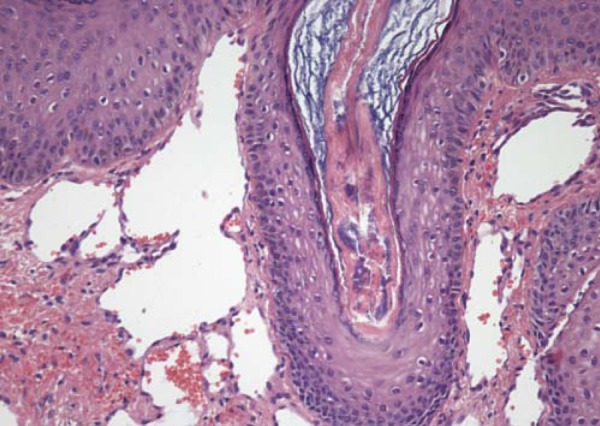

THH is a rare, benign entity that may histologically mimic malignancy, as shown in Figures 3 and 4. Dermal angiomatous proliferation with dilated vessels in the superficial dermis simulates angiokeratoma.5 Vessels that dissect collagen bundles, extravasated erythrocytes and hemosiderin deposits simulate Kaposi's sarcoma.3,4,5,10

FIGURE 3.

200x. Detail of dilated vessels in the superficial dermis simulating angiokeratoma

FIGURE 4.

400x. Peripheral area of the lesion with intense red blood cell extravasation and hemosiderin deposition

It has been found that other vascular lesions may cytomorphologically have endothelial hobnail features, but not the targetoid clinical feature. In order to cover all these forms, the term Hobnail Hemangioma was proposed. Besides the THH, retiform hemangioendothelioma (considered a low-grade malignancy angiosarcoma), Dabska tumor (malignant endovascular papillary angioendothelioma) and progressive lymphangioma also belong to this group.6,10 This aspect may also be seen focally in skin or soft tissue angiosarcoma, polymorphic hemangioendothelioma and atypical vascular lesions after radiotherapy.10

In contrast to its well-characterized histology, it is unclear whether this tumor arises from endothelial cells of blood vessels or from endothelial cells of lymphatic vessels.7 Immunohistochemical studies strongly favor the second hypothesis.4,6,7,10 There is positivity for CD31 (considered a pan-endothelial marker) and VEGFR-3 (vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-3, which is a specific marker for lymphatic endothelial cells), whereas only few or no cells are positive for CD34.6,10 Although CD34 does not differentiate between endothelial cells of blood vessels and endothelial cells of lymphatic vessels, the latter are usually negative or weakly positive for this marker.10 Furthermore, there are studies that show positive results for D2-40, which is a monoclonal antibody against human podoplanin (mucoprotein expressed in lymphatic endothelial cells).6 Some markers of cell proliferation have also been investigated, such as Ki-67 and WT1 (Wilms' tumor 1) and are little or not expressed.4 This leads to the question whether hobnail hemangioma should not be considered a malformation rather than a tumor.4,7

Diagnosis is based on clinical-pathological correlation, especially of the typical morphology of the lesion.

Simple excision is curative and allows a correct histological diagnosis.1,4 Because it is a benign condition, such lesions are only removed for diagnostic or cosmetic reasons, since literature reports clearly indicate that neither local invasion nor dissemination take place. There are no reports of recurrence after excision of the lesion.4

FIGURE 5.

200x. Detail of angulated and slit-like vessels simulating Kaposi's Sarcoma

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: None

Financial funding: None

How to cite this article: Kakizaki P, Valente NYS, Paiva DLM, Dantas FLT, Gonçalves SVCB. Targetoid hemosiderotic hemangioma - Case report. An Bras Dermatol. 2014;89(6):956-9.

Study conducted at the São Paulo Hospital for State Civil Servants - São Paulo (SP), Brazil.

References

- 1.Guillou L, Calonje E, Speight P, Rosai J, Fletcher CD. Hobnail hemangioma: a pseudomalignant vascular lesion with a reappraisal of targetoid hemosiderotic hemangioma. Am J Surg Pathol. 1999;23:97–105. doi: 10.1097/00000478-199901000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sahin MT, Demir MA, Gunduz K, Ozturkcan S, Türel-Ermertcan A. Targetoid haemosiderotic haemangioma: dermoscopic monitoring of three cases and review of the literature. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2005;30:672–676. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2230.2005.01924.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Santa Cruz DJ, Aronberg J. Targetoid hemosiderotic hemangioma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1988;19:550–558. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(88)70211-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Al Dhaybi R, Lam C, Hatami A, Powell J, McCuaig C, Kokta V. Targetoid hemosiderotic hemangiomas (hobnail hemangiomas) are vascular lymphatic malformations: a study of 12 pediatric cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;66:116–120. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2011.05.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carlson JA, Daulat S, Goodheart HP. Targetoid hemosiderotic hemangioma- a dynamic vascular tumor: report of 3 cases with episodic and cyclic changes and comparison with solitary angiokeratomas. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;41:215–224. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(99)70052-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Franke FE, Steger K, Marks A, Kutzner H, Mentzel T. Hobnail hemangiomas (targetoid hemosiderotic hemangiomas) are true lymphangiomas. J Cutan Pathol. 2004;31:362–367. doi: 10.1111/j.0303-6987.2004.00192.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Trindade F, Kutzner H, Tellechea Ó, Requena L, Colmenero I. Hobnail hemangioma reclassified as superficial lymphatic malformation: a study of 52 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;66:112–115. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2011.05.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Christenson LJ, Stone MS. Trauma-induced simulator of targetoid hemosiderotic hemangioma. Am J Dermatopathol. 2001;23:221–223. doi: 10.1097/00000372-200106000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ortiz-Rey JA, González-Ruiz A, San Miguel P, Alvarez C, Iglesias B, Antón I. Hobnail haemangioma associated with the menstrual cycle. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2005;19:367–369. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2004.01168.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mentzel T, Partanen TA, Kutzner H. Hobnail hemangioma ("targetoid hemosiderotic hemangioma"): clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical analysis of 62 cases. J Cutan Pathol. 1999;26:279–286. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0560.1999.tb01845.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]