Abstract

American Tegumentary Leishmaniasis (ATL) is a chronic, non-contagious, infectious disease affecting millions of people worldwide. The timely and proper treatment is of great importance to prevent the disease from progressing to destructive and severe forms. Treatment for ATL recommended by the Brazilian Ministry of Health is similar for the whole country, regardless of the species of Leishmania. It is known that the response to treatment may vary with the strain of the parasite, the immune status of the patient and clinical form. We report the case of a healthy patient, coming from Manaus, Amazonas state, Brazil, who presented resistance to treatment with N-methyl-glutamine and liposomal amphotericin B, only being healed after using pentamidine.

Keywords: Leishmania guyanensis; Leishmaniasis, cutaneous; Pentamidine; Skin diseases, parasitic

INTRODUCTION

American Tegumentary Leishmaniasis (ATL) is an infectious, chronic, non-contagious disease that affects millions of people worldwide. It is caused by several species of protozoa of the Leishmania genus and transmitted to men by wild and domesticated animals through females of Phlebotominae, of which the most common is Lutzomya. The most common species in Brazil are L. (Viannia) braziliensis, Leishmania (Viannia) guyanensis, and L. (Leishmania) amazonensis.1,2 L. (V.) guyanensis is the second most prevalent species in Brazil, one of the most common in the Amazon region. In a study performed in the state of Amazonas, it was verified that in 88.1% of the patients with ATL the species found was L. guyanensis.3

ATL is currently distributed in all of the states, with the Center-West region now occupying the third place in prevalence in the national territory.1,4

It is in a phase of geographical expansion. Analyses of epidemiological studies of ATL have suggested changes in the behavior of the disease.2 Over the years, it was seen as an occupational disease, affecting adult men exposed to forest regions, but today there is increasing involvement of women and children, as a consequence of the urbanization process.1,5

The incubation period of the cutaneous form may vary from one week to one month, whereas mucosal lesions usually appear from one to two years after the onset of infection. ATL may present diverse clinical forms, from self-limiting cutaneous lesions to mucocutaneous disfiguring lesion forms, depending on the immune status of the patient and species of Leishmania. 1

ATL diagnosis encompasses epidemiological, clinical and laboratorial aspects. The association of some of these elements is frequently necessary to achieve the final diagnosis.2 Diagnosis is reached through direct research, culture in specific medium or histopathological test. Immunological tests, such as Montenegro's intradermal reaction and indirect immunofluorescence, are indirect methods used.1

Timely and adequate treatment is of great importance to prevent the evolution of the disease to destructive and severe forms, such as the mucosal form.4 Drugs currently employed present high toxicity and frequent adverse effects and none of them is sufficiently effective. 3,6 Relapse, therapeutical failure in immunodepressed patients and treatment resistance are factors that motivate the search for an ideal drug.6

The drug of choice is N-methylglucamine antimoniate (NMG). As a second-choice treatment there is pentamidine isethionate and amphotericin B. Other drugs already used for the treatment of ATL are miltefosine, azithromycin, itraconazole, ketoconazole, allopurinol, paromomycin and pentoxifylline.3,7,8

Although the ATL treatment recommended by the Health Department (Ministério da Saúde - MS) is the same for the whole country, regardless of which Leishmania species caused the disease, there are few clinical trials showing the true efficacy of these drugs. It is known that the response to the treatment with antimony may vary according to parasite strain, immune status of the patient and clinical form.3,6

CASE REPORT

Female patient, 6 years old, originally from Manaus-AM, had resided in Campo Grande-MS for the last 4 months. Two months ago she progressively developed an erythematous, crusted and erosive plaque with infiltrated edges, measuring 2.5 cm in diameter in the distal extensor region of left arm (Figure 1). Direct investigation (imprint) detected amastigote structures compatible with Leishmania sp. Histopathological examination revealed epidermis with pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia, dermis with a dense inflammatory infiltrate constituted of lymphocytes, plasmocytes, macrophages and some multinucleated giant cells. Macrophages containing corpuscles with characteristics of amastigote forms of Leishmania (Figure 2) were observed. She received N-methylglucamine (NMG) (5.3ml/day for 20 days) with discreet lesion regression. As she showed no improvement 2 months after the end of the NMG treatment, liposomal amphotericin B was initiated (total dose of 575mg). Thirty days after the treatment active lesions still persisted. Suspecting that the Leishmania was acquired in the Amazon region, we began using pentamidine, prescribing 7mg/kg IM in a single dose. The patient presented regression of the lesion and a cicatricial plaque remained (Figure 3).

FIGURE 1.

Erythematous, erosive and crusted plaque of infiltrated borders, with a 2.5cm diameter in the distal extensor region of left arm

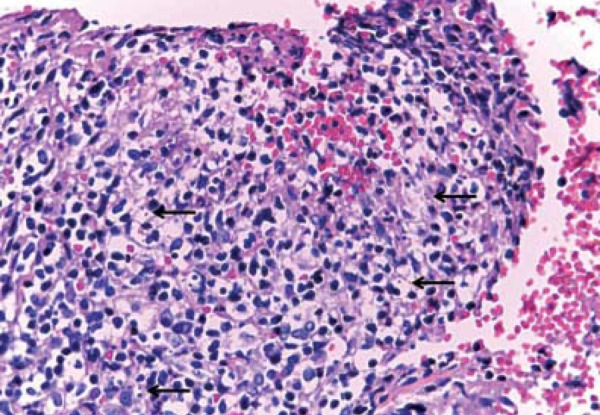

FIGURE 2.

Epidermis with pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia, dermis with dense inflammatory infiltrate constituted of lymphocytes, plasmocytes, macrophages and some giant multinucleated cells. Macrophages were observed containing corpuscles with characteristics suggesting amastigote forms of Leishmania sp (arrows)

FIGURE 3.

Atrophic cicatricial plaque after treatment with pentamidine

DISCUSSION

In Brazil, patients with cutaneous ATL infected with L.(V.) b. or L.(V.) g. treated with NMG IV or IM during 20 days have had healing rates of 50.8% e 26.3% respectively. The conclusion was that the leishmania species constitutes a predictor in the treatment success with NMG.6

According to some studies, in the treatment of ATL by L. (V.) guyanensis, pentamidine would be the drug of choice in the state of Amazonas. Pentamidine would be an important therapeutic option for cutaneous ATL, due to its cost/benefit, besides being safe for treating cardiopaths.3

Pentamidine is a second-choice drug for the treatment of ATL that does not respond to pentavalent antimonials, or when their use is contraindicated. The papers of Pradinaud and Talhari demonstrated good results with low doses of cutaneous ATL caused by L. (V.) guyanensis - total doses close to 1.0g.3

Pentamidine is the first-line drug in Suriname and in French Guiana, where L. guyanensis predominates. In French Guiana, a cure rate of almost 100%, and in Suriname, of approximately 90% were observed.3,6

Few studies were performed in the Americas using pentamidine as a therapeutic option for ATL. The classic recommended dose is 4mg/kg/day, through deep intramuscular application, every 2 days, not exceeding the recommended total dose of 2g.3

The main adverse reactions related to pentamidine are pain, induration and sterile abscesses at the injection site, nausea, vomiting, dizziness, adynamia, myalgia, headache, hypotension, syncope, transient hypoglycemia and hyperglycemia. 3,6,9,10

ATL is a neglected disease. In general, it involves populations with a low socioeconomic level, has weak political force and is little attractive for the pharmaceutical industry. One of the great challenges is to increase investments for the search of drugs with better efficacy, safety, low cost, ease of management and sustainability. 4

We report a case of cutaneous ATL which presented treatment resistance to NMG and liposomal amphotericin B. In spite of being in a high prevalence area of ATL, we interpreted it as acquired in the city of origin (Manaus) and opted for treating it with pentamidine, for some studies demonstrate that, when treating ATL by L. (V.) guyanensis, pentamidine is the first-line drug in the state of Amazonas.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: None

Financial funding: None

How to cite this article: Couto DV, Hans-Filho G, Medeiros MZ, Vicari CFS, Barbosa AB, Takita LC. American tegumentary leishmaniasis - a case of therapeutic challenge. An Bras Dermatol. 2014;89(6):974-6.

Work performed at the Department of Dermatology, Teaching Hospital, Universidade Federal do Mato Grosso do Sul (UFMS) - Campo Grande (MS), Brazil.

References

- 1.Murback NDN, Hans-Filho G, Nascimento RAF, Nakazato KRO, Dorval MEMC. American cutaneous leishmaniasis: clinical, epidemiological and laboratory studies conducted at a university teaching hospital in Campo Grande, Mato Grosso do Sul, Brazil. An Bras Dermatol. 2011;86:55–63. doi: 10.1590/s0365-05962011000100007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Guedes ACM, Carvalho MLR, Melo MN. American tegumentary leishmaniasis: an unusual presentation. An Bras Dermatol. 2008;83:445–449. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ourives-Neves L, Chrusciak-Talhari A, Gadelha EPN, da Silva Júnior RM, Guerra JAO, Ferreira LCL, Talhari S. A randomized clinical trial comparing meglumine antimoniate, pentamidine and amphotericin B for the treatment of cutaneous leishmaniasis by Leishmania guyanensis. An Bras Dermatol. 2011;86:1092–1101. doi: 10.1590/s0365-05962011000600005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Penna GO, Domingues CM, Siqueira JB, Jr, Elkhoury AN, Cechinel MP, Grossi MA, et al. Dermatological diseases of compulsory notification in Brazil. An Bras Dermatol. 2011;86:865–877. doi: 10.1590/s0365-05962011000500002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Da-Silva LMR, Cunha PR. Urbanization of American Cutaneous Leishmaniasis in Campinas - Sao Paulo (SP) and region: problems and challenges. An Bras Dermatol. 2007;82:515–519. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lima EB, Porto C, Motta JCO, Sampaio RNR. Treatment of American cutaneous leishmaniasis. An Bras Dermatol. 2007;82:111–124. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sampaio RNR, Lucas IC, Costa Filho AV. The use of azythromycin and N-methyl glucamine for the treatment of cutaneous Leishmaniasis caused by Leishmania (Leishmania) amazonensis in C57BL6 mice. An Bras Dermatol. 2009;84:125–128. doi: 10.1590/s0365-05962009000200004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lima MVN, Oliveira RZ, Lima AP, Cerino DA, Silveira TGV. American cutaneous leishmaniasis with fatal outcome during pentavalent antimoniate treatment. An Bras Dermatol. 2007;82:269–271. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brasil. Ministério da Saúde. Secretaria de Vigilância em Saúde . Manual de Vigilância da Leishmaniose Tegumentar Americana. 2. ed. atual. Brasília: Editora do Ministério da Saúde; 2010. 180 p. (Série A. Normas e Manuais Técnicos) [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lai A Fat EJ, Vrede MA, Soetosenojo RM, Lai A Fat RF. Pentamidine, the drug of choice for the treatment of cutaneous leishmaniasis in Surinam. Int J Dermatol. 2002;41:796–800. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-4362.2002.01633.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]