Abstract

A growing body of evidence suggests that BRAF inhibitors, in addition to their acute tumor growth-inhibitory effects, can also promote immune responses to melanoma. The present studies aimed to define the immunologic basis of BRAF-inhibitor therapy using the Braf/Pten model of inducible, autochthonous melanoma on a pure C57BL/6 background. In the tumor microenvironment, BRAF inhibitor PLX4720 functioned by on-target mechanisms to selectively decrease both the proportions and absolute numbers of CD4+Foxp3+ regulatory T cells (Treg) and CD11b+Gr1+ myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSC), while preserving numbers of CD8+ effector T cells. In PLX4720-treated mice, the intratumoral Treg populations decreased significantly, demonstrating enhanced apopotosis. CD11b+ myeloid cells from PLX4720-treated tumors also exhibited decreased immunosuppressive function on a per-cell basis. In accordance with a reversion of tumor immune suppression, tumors that had been treated with PLX4720 grew with reduced kinetics after treatment was discontinued, and this growth delay was dependent on CD8 T cells. These findings demonstrate that BRAF inhibition selectively reverses two major mechanisms of immunosuppression in melanoma, and liberates host adaptive antitumor immunity.

Keywords: PLX4720, Regulatory T cells, Myeloid-derived suppressor cells, CD8 T cells, tumor microenvironment

INTRODUCTION

BRAF inhibitors are small-molecule drugs that impair melanoma cell proliferation and survival by targeting the oncogenic driver mutation BRAFV600E, expressed by~50% of metastatic melanomas (1). The prototype BRAF inhibitor vemurafenib induces dramatic responses in patients (2), however resistance typically develops within a year (1). A growing body of evidence now suggests that vemurafenib also influences immune responses to melanoma (3–5), although better insights into this phenomenon are needed. In melanoma patients, vemurafenib has been shown to increase the numbers of CD8 T cells (4, 5) and CD4 T cells (4), as well as the expression of T-cell functional markers, and melanoma differentiation antigens (5) in the tumor microenvironment. Increased frequency of tumor antigen-specific CD8 T cells has also been found in the blood of vemurafenib-treated patients (6), suggesting a possible T-cell cross-priming. Despite this, vemurafenib treatment increased the expression of T-cell exhaustion markers within tumors (5), and decreased the peripheral lymphocyte counts (7). Thus, whether T cells contribute to the efficacy of BRAF inhibitors remains an open question.

Studies in immune competent mice have begun to address this question, although different models have yielded conflicting answers. In the transplantable SM1WT1 model, the vemurafenib analog PLX4720 improved intratumoral ratios of CD8 to regulatory T cells (Treg), and CD8 T cells were absolutely required for drug efficacy (8). Accordingly, in a transplantable tumor model derived from Tyr::CreER/BrafCA/Ptenlox/lox (Braf/Pten) mice, the tumor growth-inhibitory effects of PLX4720 depended on CD8 T cells (9). However in autochthonous Braf/Pten tumor-bearing mice, PLX4720 indiscriminately decreased the frequencies of immune cells in tumors on a C57BL/6 background (10), while demonstrating a dependency on CD4 T cells for elimination of tumors on a mixed genetic background (11). Thus, the immunologic effects of BRAF inhibitors appear variable and may depend heavily on the tumor model and genetic background under study.

The present studies revisit the immunologic implications of BRAF inhibition in the Braf/Pten inducible autochthonous melanoma model on a pure C57BL/6 background. We find that BRAFV600E inhibition initiates a quantitative loss of both Tregs and myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSC) from the tumor microenvironment. Accordingly, short-term BRAF inhibition enables subsequent control of small melanomas by the host CD8 T cells. Despite this, we show that PLX4720 efficiently arrests melanoma growth even in the absence of host T cells. These studies confirm that BRAF inhibitors perturb two major mechanisms of tumor immune suppression, and highlight CD8 T cell-dependent tumor control as a secondary mechanism of BRAF-inhibitor action.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mice and tumor inductions

Studies were performed in accordance with the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee Guidelines at Dartmouth. Tyr::CreER+/−BrafCA/+Ptenlox/lox(Braf/Pten) mice (12) were bred onto a B6 background, and confirmed by the DartMouse™ speed congenic facility. Experiments utilized mice of a single gender. Tumors were induced in 3–4 week-old mice by intradermal injection of 4-hydroxy-tamoxifen (10μl of a 20 μM solution in DMSO). As a control, 6–8 week old C57BL/6 mice (The Jackson Laboratory) were inoculated intradermally with 1×105 B16-F10 cells (a gift from Alan Houghton; tested by IMPACT and authenticated at the U. of Missouri RADIL, March 2013). Where indicated, C57BL/6 mice, and RAG1−/− mice (Jackson Laboratory, bred in-house) were dorsally grafted with ~1 cm2 sections of tail skin from Braf/Pten mice, and tumors were induced one week later by topical application of 4-hydroxy-tamoxifen.

In Vivo Drug Treatments and CD8 Antibody Depletions

PLX4720 was provided by Plexxikon Inc. under a Materials Transfer Agreement, and was compounded in rodent diet (417 mg/kg) by Research Diets, Inc. Mice bearing palpable melanomas were fed PLX4720-containing or control diet ad libitum, for the designated period. Anti-CD8 (mAb clone 2.43, produced in-house) was administered i.p. every four days (300 μg/dose), anti-CD4 (mAb clone GK1.5, produced in house) was administered i.p. weekly (300μg/dose).

Flow cytometry

Tumors were harvested, weighed, minced, and digested for 45 minutes, with gentle shaking, at 37°C in HBSS containing 7mg/ml collagenase D and 200 μg/ml DNase-I (Roche). Single-cell suspensions were stained with antibodies including anti-CD45-APC-Cy7, anti-CD3-Vioblue, anti-CD8-PCP, anti-CD4-FITC, anti-Foxp3-PE, anti-CD11b-APC, anti-GR-1-PE-Cy7, Anti-GATA3-PE, anti-T-bet-PE-Cy7, anti-RORγt-APC (BioLegend or eBioscience); and anti-Annexin-V-Alexa647 (BD Pharmingen). Cells were fixed/permeabilized using reagents from the Foxp3 staining kit (eBioscience). Flow cytometry was performed on a Miltenyl MACS Quant10 Analyzer. Total cells were enumerated using the flow cytometer.

Analysis of T cell cross-priming

Tumor-bearing mice received 1×105 naïve, congenically-marked (Ly5.2+) gp10025–33-specific CD8 T cells isolated from pmel TCR transgenic mice (13). Cells were magnetically purified from spleens by CD44-positive and CD8-negative selection (Miltenyi), and injected i.v. Anti-CD4 depleting antibody (mAb clone GK1.5; produced in-house) was administered i.p. (500μg per dose). Tumor-draining inguinal lymph nodes were harvested, mechanically dissociated, and analyzed by flow cytometry.

MDSC suppression assay

Tumors were digested as described above, and CD11b+ cells were isolated magnetically by positive selection (Miltenyi). Purified CD11b+ cells were combined at indicated ratios with RBC-depleted C57BL/6 mouse splenocytes, and added to a 96-well plate pre-coated with anti-CD3 (5 mg/ml, clone OKT3) and anti-CD28 (5 mg/ml, clone PV-1) (BioXcell), to a final concentration of 3×105 splenocytes/200μl/well. 72h later, supernatants were harvested and assayed for IFNγ production by ELISA (R&D Systems).

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

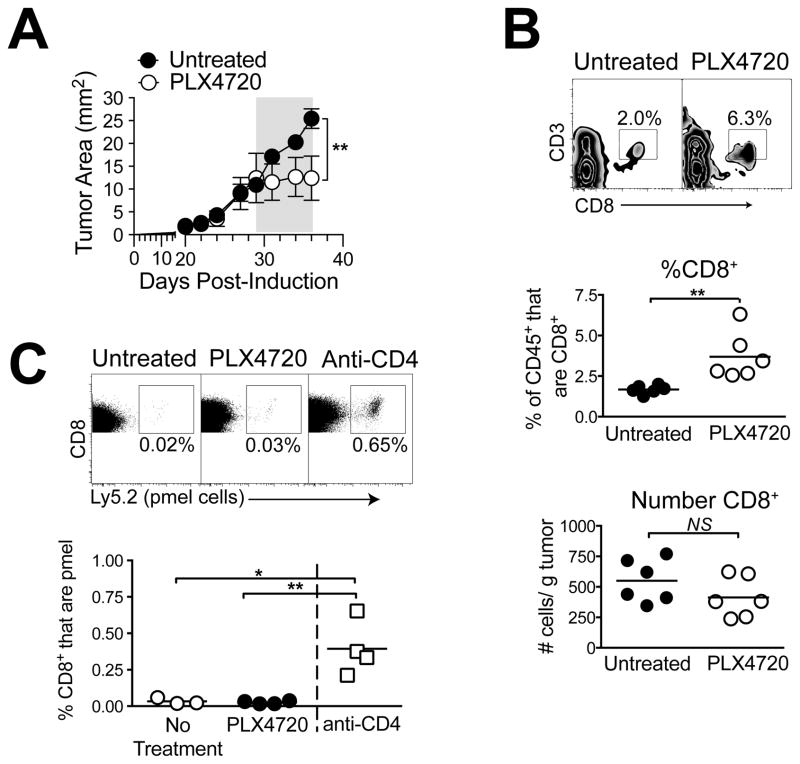

PLX4720 does not induce intratumoral accumulation or cross-priming of CD8 T cells in mice bearing autochthonous Braf/Pten melanomas

To evaluate the effects of BRAF inhibition on CD8 T-cell responses to Braf/Pten tumors, mice bearing palpable melanomas received PLX4720-containing diet, and tumors were analyzed by flow cytometry. As previously reported (10), Braf/Pten melanomas on a C57BL/6 background were sensitive to PLX4720, demonstrating immediate and stable growth arrest, although tumor regression was not observed (Figure 1A). Similar growth arrest was obtained when mice were treated with vemurafenib (PLX4032) by gavage (Supplementary Figure 1). In the tumor microenvironment, PLX4720 treatment for 10 days significantly increased CD8 T cells by proportion of CD45+ cells, but not by absolute number (Figure 1B). This is contrary to reports that CD8 T cell frequencies are decreased by PLX4720 in this model (10).

Figure 1. PLX4720 does not promote CD8 T-cell infiltration or cross-priming.

Mice bearing Braf/Pten tumors were treated with PLX4720-containing diet (A) for 7d (indicated by gray bar), and tumor growth was monitored. Symbols represent mean +/− SEM of 4–6 mice per group; statistical significance was calculated by 2-way ANOVA. (B) PLX4720 was administered for 10 days (day 28–38), and tumors were analyzed for infiltrating CD8+CD3+ T cells, by proportion gated on CD45+ cells (top and middle), and by absolute number (bottom). (C) Mice received 105 Ly5.2+ pmel cells on d 27, and were treated with PLX4720 on days 29–38, or anti-CD4 on days 29 and 35. Pmel cells were detected in tumor-draining lymph nodes on day 38. Symbols represent individual mice and horizontal lines depict means; statistical significance was calculated by 2-tailed t test. * P<0.05, ** P<0.01, NS = not significant. Experiments were conducted at least twice with similar results.

While CD8 T cell numbers were not changed by the treatment, it remained possible that BRAF-inhibition promoted the de novo priming of tumor antigen-specific CD8 T cells. To assess cross-priming, 105 naiveCD8 T cells (pmel cells) specific for the melanoma antigen gp100 were adoptively transferred into Braf/Pten tumor-bearing mice. Pmel cells did not expand in tumor-draining lymph nodes of untreated mice, however total depletion of Tregs with anti-CD4 mAb elicited pmel cell priming and accumulation as a positive control (Figure 1C), in accordance with published studies in B16 melanoma (14). Despite this, PLX4720 treatment did not induce detectable pmel cell expansion (Figure 1C). Thus BRAF inhibition did not drive cross-priming of Ag-specific T cells.

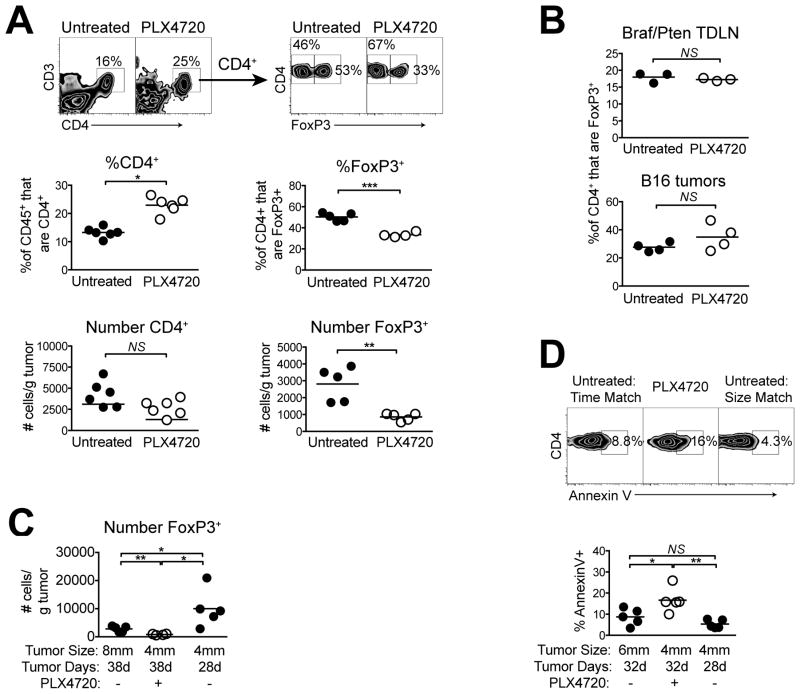

PLX4720 promotes the selective loss of regulatory T cells from the Braf/Pten tumor microenvironment

Recent reports have shown reduced intratumoral Foxp3+ Treg populations following treatment with PLX4720, however, results in one study (10) showed that this effect was not specific to Tregs, and no studies have evaluated the absolute numbers of Tregs (8, 11). To address this, we measured CD4 T-cell populations in Braf/Pten tumors following 10 days of treatment. As with CD8 T cells, PLX4720 increased totalCD4 T cells by the proportion of CD45+ cells but not the absolute number (Figure 2A). Despite this, PLX4720 markedly reduced both the proportion (of CD4+ cells) and the absolute number of Foxp3+ Tregs (Figure 2A). In contrast, Treg proportions were unchanged in Braf/Pten tumor-draining lymph nodes, and in BRAFWT B16 tumors, demonstrating that this effect was both localized and on-target (Figure 2B).

Figure 2. BRAF inhibition induces the selective loss of Tregs from Braf/Pten tumors.

Mice bearing Braf/Pten tumors were treated with PLX4720 for 10 days (days 28–38) and (A) tumors were analyzed for infiltration of CD4+CD3+ T cells by proportion gated on CD45+ cells or absolute number, or Foxp3+ Tregs by proportion gated on CD4+CD3+ cells or by absolute number. (B) Braf/Pten tumor-draining lymph nodes were analyzed (top) or B16 melanoma tumor-bearing mice were used (bottom). (C) Tumor induction was delayed by 10 days to provide an additional untreated, size-matched (4mm diameter) control group. (D) PLX4720 was administered for 4 days, and the proportion of Foxp3+CD4+ cells staining for annexin-V was then determined. Points represent individual mice and horizontal lines depict means; statistical significance was calculated by 2-tailed t test. * P<0.05, ** P<0.01, NS = not significant. Experiments were conducted at least twice with similar results.

Because PLX4720 arrested Braf/Pten tumor growth, it was possible that the reduction in Treg cell numbers was due to decreased tumor burden. Thus, Treg populations were compared in Braf/Pten tumors of 4mm vs. 8mm average diameter. Unexpectedly, the smaller tumors contained more Tregs (normalized for tumor mass) compared to that in larger tumors (Figure 2C). Moreover, 4mm untreated tumors had ~8 times the number of Tregs as compared with size-matched tumors that had been treated with PLX4720 for 10 days prior to analysis (Figure 2C). Thus, rather than decreasing Treg recruitment, PLX4720 promoted a substantial quantitative loss of pre-existing Tregs from Braf/Pten tumors.

Analysis of CD4 T-cell expression of transcription factors T-bet, GATA3, and RORγt illustrated no change within PLX4720-treated tumors, suggesting a lack of Treg cell conversion to another Th subset (Supplemental Figure 2). However, results from annexin-V staining indicated a significant increase in the proportion of Tregs undergoing apoptosis in PLX4720-treated tumors(Figure 2D). Thus, BRAF inhibition increased Treg apoptosis and led to a selective loss of these cells from the tumor microenvironment.

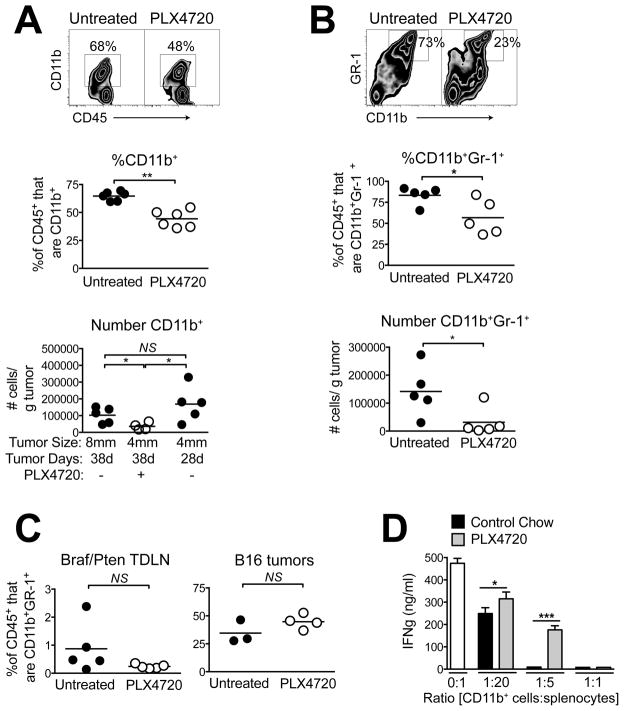

PLX4720 selectively depletes intratumoral myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSC)

Our finding that PLX4720 increased both CD8 and CD4 T cells by proportion but not in absolute number suggested that another CD45+ population was being lost within the tumors. In addition to Tregs, MDSCs are major suppressors of tumor immunity, and it has been shown recently that MDSC populations are decreased in the peripheral blood of patients receiving vemurafenib (15). In Braf/Pten tumors, total CD11b+ cells constituted a major fraction of CD45+ leukocytes, and PLX4720 significantly decreased this population by both proportion and absolute number (Figure 3A). The reduction in myeloid cell numbers was not attributed solely to reduced tumor burden, as 4mm untreated tumors had ~5-times the number of CD11b+ cells compared with 4mm tumors that had been treated with PLX4720 for 10 days prior to the analysis (Figure 3A). Thus, similar to Tregs, myeloid cells were quantitatively lost from the tumors during PLX4720 treatment. However, unlike Tregs, CD11b+ cells did not demonstrate increased apoptosis (Supplementary Figure 3), suggesting that their loss may be attributed to distinct mechanisms.

Figure 3. BRAF inhibition induces the selective loss of immunosuppressive myeloid cells from Braf/Pten tumors.

Mice bearing Braf/Pten tumors were treated with PLX4720 for 10 days (days 28–38) and (A) tumors were analyzed for CD11b+ cells or (B) CD11b+Gr1+ cells by proportion gated on CD45+ cells (top and middle) or by absolute number (bottom). (C) Braf/Pten tumor-draining lymph nodes were analyzed (top) or B16 melanoma tumor-bearing mice were used (bottom). Points represent individual mice and horizontal lines depict means; statistical significance was calculated by 2-tailed t test. (D) CD11b+ cells were isolated from pooled PLX4720-treated (gray bars) vs. untreated (black bars) tumors (n = 4–8 tumors per group) and assayed for suppression of IFNγ production by activated splenocytes (see Methods). Data represent mean +/− standard deviation. * P<0.05, ** P<0.01, *** P<0.0001, NS=not significant. Experiments were conducted at least twice with similar results.

A majority of CD11b+ cells within Braf/Pten tumors also expressed the MDSC marker Gr1, and PLX4720 decreased both the proportions and absolute numbers of CD11b+Gr1+ cells (Figure 3B). This was an on-target and localized effect of PLX4720, as it did not occur in BRAFWT B16 tumors, or in Braf/Pten tumor-draining lymph nodes (Figure 3C). To determine if PLX4720 also influences the suppressive function of intratumoral myeloid cells, CD11b+ cells were isolated from untreated vs. PLX4720-treated tumors and their ability to suppress IFNγ production by activated T cells in vitro were compared. While myeloid cells from both groups were suppressive at high myeloid cells: splenocytes ratios, cells from PLX4720-treated tumors were significantly less suppressive, on a per-cell basis, at lower ratios (Figure 3D). Thus, PLX4720 promoted a quantitative loss of CD11b+Gr1+ cells from Braf/Pten tumors, and decreased the overall immunosuppressive function of myeloid cells remaining in these tumors.

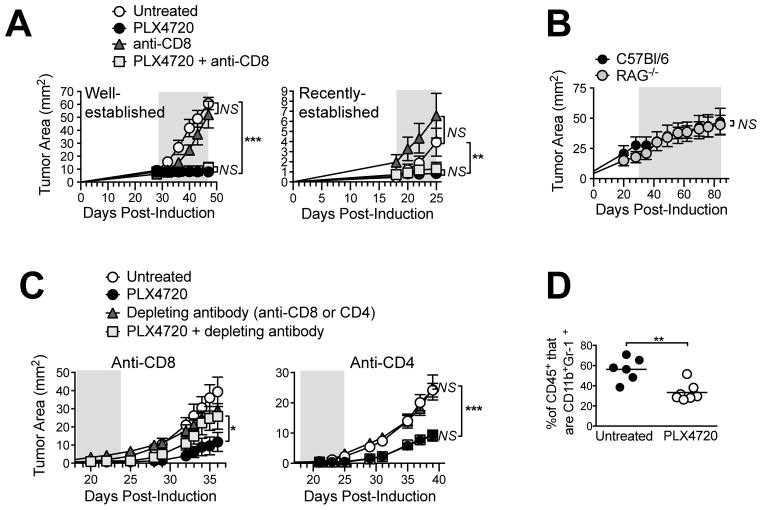

PLX4720 enables host CD8 T cell-mediated control of Braf/Pten melanomas during the post-treatment period

Our finding that BRAF inhibitions electively reduced two major immunosuppressive cell populations suggested that CD8 T cells may contribute to tumor control in PLX4720-treated mice. To assess this, PLX4720 was administered either alone or in combination withanti-CD8 depleting antibody. Total CD8 T-cell depletion (including in tumors; Supplemental Figure 4) did not diminish the efficacy of PLX4720 against well-established tumors (Figure 4A, left), or even against smaller, less established tumors (Figure 4A, right), for which immune effects would have been more pronounced. Furthermore, PLX4720 was equally as effective against autochthonous Braf/Pten tumors (growing in skin grafts) on RAG1−/− mice and C57BL/6 mice (Figure 4B), demonstrating a lack of requirement for T cells or B cells.

Figure 4. BRAF inhibition promotes CD8 T cell-mediated control of Braf/Pten tumor growth during the post-treatment period.

PLX4720 was administered for the duration depicted by gray shaded area, (A) either alone or concurrently with anti-CD8 every 4 days, (B) to RAG1−/− or C57BL/6 mice bearing Braf/Pten tumors in grafted skin (see Methods). (C) PLX4720 was administered and then discontinued, and depleting antibodies were given as indicated (left, anti-CD8, every 4 days starting on d 16; right, anti-CD4, weekly starting on d 17). Symbols represent mean +/− SEM of 3–6 mice/group; statistical significance was calculated by 2-way ANOVA. * P<0.05, ** P<0.01, *** P<0.0001. (D) Tumor-bearing mice were treated as in Figure 3, except PLX4720 was discontinued for 4 days prior to analysis for proportion of CD11b+Gr1+ cells (gated on CD45+ cells). Symbols represent individual mice and horizontal lines depict means; statistical significance was calculated by 2-tailed t test. ** P<0.01. Data are representative of two (A, B, D) or three (C) replicate experiments yielding similar results.

Despite this, a possibility remained that the dominant tumor-static effects of PLX4720 masked a weaker T-cell response, which could be interrogated during the post-treatment phase. Indeed, when PLX4720 was administered for 1 week and then discontinued, small tumors continued to grow with reduced kinetics for several days thereafter (Figure 4C, left), and this growth delay was abrogated by CD8 T-cell depletion. Anti-CD8 did not alter the growth of untreated tumors (Figure 4C, left), nor did the depletion of CD4 T cells impair drug efficacy at any point (Figure 4C, right). Thus, while immune responses may have been obfuscated by the potent tumor growth-inhibitory properties of PLX4720, BRAF inhibition elicited CD8 T cell-mediated tumor control that was evident during the post-treatment period. Moreover, while Tregs rapidly repopulated tumors after PLX4720 cessation (not shown), the proportions of MDSCs remained significantly decreased at least 4 days thereafter (Figure 4D). Therefore an ongoing reduction in MDSCs coincided with CD8 T cell-mediated tumor control in PL4720-treated mice.

The present data are consistent with CD8 T cells as a secondary and redundant mechanism of tumor control in mice treated with BRAF inhibitors. This is in contrast to recent studies using transplantable Braf/Pten tumors (9), and autochthonous Braf/Pten tumors on a mixed genetic background (11), which report an absolute dependence on CD8 and CD4 T cells, respectively. To the contrary, CD4 depletion might have slight immune-stimulatory effects in the present model, as evidenced by cross-priming of tumor-specific pmel cells (see Figure 1C). These discrepancies may underscore differences in tumor immunogenicity and cellular composition between autochthonous and transplantable tumors on different genetic backgrounds, and may portend even greater diversity among melanoma patients receiving BRAF inhibitors.

In the present model PLX4720 did not increase the absolute numbers of CD8 T cells in Braf/Pten tumors, or induce new CD8 T-cell priming. While robust T-cell infiltration has been described in tumors of vemurafenib-treated patients, a small fraction of the tumors do not exhibit this behavior (4, 5). In our model, the lack of CD8 T-cell infiltration could be attributed to a lack of tumor regression (Figure 1A), which may relate to PTEN deficiency (16, 17), although this remains controversial. Regardless, autochthonous Braf/Pten tumors on a C57BL/6 background may model a subset of poorly-immunogenic human melanomas that are not easily infiltrated by effector T cells.

Future studies will be required to elucidate mechanisms underlying the reduced numbers of Tregs and MDSCs in PLX4720-treated tumors. CCR2 was shown to be required for the efficacy of PLX4720 in the SM1WT1 model (18) and, while our data are more consistent with apoptosis of pre-existing Tregs, the decreased production of CCL2 by melanoma cells could potentially impair recruitment of MDSCs. Selective Treg apoptosis in GIST tumors has been shown to result from decreased indolamine-2,3-dioxygenase (19), which is worth further examination. BRAF inhibition has also been shown to decrease melanoma xenograft production of VEGF (20), which could potentially impair Treg and/or MDSC responses. It remains to be demonstrated whether the reduced Treg and/or MDSC responses are directly responsible for CD8 T-cell immunity following PLX4720 cessation, and whether the remaining Tregs exhibit decreased suppressive function. Enhanced antigen expression and presentation (3, 21) as well as off-target enhancement of T-cell function by PLX4720 (22, 23) may also contribute to the observed response.

In conclusion, the present studies demonstrate that on-target inhibition of BRAFV600E in melanoma cells has the downstream consequences of decreasing Treg and MDSC fitness within the tumor microenvironment, and promoting CD8 T cell-dependent tumor control. This work underscores an essential link between oncogenic BRAFV600E signaling and two major mechanisms of tumor immune suppression, providing additional rationale for clinical studies combining BRAF inhibitors and immunotherapies.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Financial support: This work was supported by a Development Grant from the Melanoma Research Alliance, R01 CA120777-06, ACS RSG LIB-121864, and Pilot Funds from the Norris-Cotton Cancer Center P30 CA023108. SMS was supported by T32GM00874-14, and DWM was supported by NIH R01 CA134799.

Footnotes

The Authors have no conflicts of interest

References

- 1.Bollag G, Tsai J, Zhang J, Zhang C, Ibrahim P, Nolop K, et al. Vemurafenib: the first drug approved for BRAF-mutant cancer. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2012;11:873–86. doi: 10.1038/nrd3847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chapman PB, Hauschild A, Robert C, Haanen JB, Ascierto P, Larkin J, et al. Improved survival with vemurafenib in melanoma with BRAF V600E mutation. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:2507–16. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1103782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boni A, Cogdill AP, Dang P, Udayakumar D, Njauw CN, Sloss CM, et al. Selective BRAFV600E inhibition enhances T-cell recognition of melanoma without affecting lymphocyte function. Cancer Res. 2010;70:5213–9. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-0118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wilmott JS, Long GV, Howle JR, Haydu LE, Sharma RN, Thompson JF, et al. Selective BRAF inhibitors induce marked T-cell infiltration into human metastatic melanoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2012;18:1386–94. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-2479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Frederick DT, Piris A, Cogdill AP, Cooper ZA, Lezcano C, Ferrone CR, et al. BRAF inhibition is associated with enhanced melanoma antigen expression and a more favorable tumor microenvironment in patients with metastatic melanoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2013;19:1225–31. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-12-1630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hong DS, Vence L, Falchook G, Radvanyi LG, Liu C, Goodman V, et al. BRAF(V600) inhibitor GSK2118436 targeted inhibition of mutant BRAF in cancer patients does not impair overall immune competency. Clin Cancer Res. 2012;18:2326–35. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-2515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schilling B, Sondermann W, Zhao F, Griewank KG, Livingstone E, Sucker A, et al. Differential influence of vemurafenib and dabrafenib on patients’ lymphocytes despite similar clinical efficacy in melanoma. Ann Oncol. 2014;25:747–53. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdt587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Knight DA, Ngiow SF, Li M, Parmenter T, Mok S, Cass A, et al. Host immunity contributes to the anti-melanoma activity of BRAF inhibitors. J Clin Invest. 2013;123:1371–81. doi: 10.1172/JCI66236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 9.Cooper ZA, Juneja VR, Sage PT, Frederick DT, Piris A, Mitra D, et al. Response to BRAF Inhibition in Melanoma Is Enhanced When Combined with Immune Checkpoint Blockade. Cancer Immunol Res. 2014;2:643–54. doi: 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-13-0215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hooijkaas A, Gadiot J, Morrow M, Stewart R, Schumacher T, Blank CU. Selective BRAF inhibition decreases tumor-resident lymphocyte frequencies in a mouse model of human melanoma. Oncoimmunology. 2012;1:609–17. doi: 10.4161/onci.20226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ho PC, Meeth KM, Tsui YC, Srivastava B, Bosenberg MW, Kaech SM. Immune-based antitumor effects of BRAF inhibitors rely on signaling by CD40L and IFNgamma. Cancer Res. 2014;74:3205–17. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-13-3461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dankort D, Curley DP, Cartlidge RA, Nelson B, Karnezis AN, Damsky WE, Jr, et al. Braf(V600E) cooperates with Pten loss to induce metastatic melanoma. Nat Genet. 2009;41:544–52. doi: 10.1038/ng.356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Overwijk WW, Theoret MR, Finkelstein SE, Surman DR, de Jong LA, Vyth-Dreese FA, et al. Tumor regression and autoimmunity after reversal of a functionally tolerant state of self-reactive CD8+ T cells. J Exp Med. 2003;198:569–80. doi: 10.1084/jem.20030590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhang P, Cote AL, de Vries VC, Usherwood EJ, Turk MJ. Induction of postsurgical tumor immunity and T-cell memory by a poorly immunogenic tumor. Cancer Res. 2007;67:6468–76. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-1264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schilling B, Sucker A, Griewank K, Zhao F, Weide B, Gorgens A, et al. Vemurafenib reverses immunosuppression by myeloid derived suppressor cells. Int J Cancer. 2013;133:1653–63. doi: 10.1002/ijc.28168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Trunzer K, Pavlick AC, Schuchter L, Gonzalez R, McArthur GA, Hutson TE, et al. Pharmacodynamic effects and mechanisms of resistance to vemurafenib in patients with metastatic melanoma. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:1767–74. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.44.7888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Paraiso KH, Xiang Y, Rebecca VW, Abel EV, Chen YA, Munko AC, et al. PTEN loss confers BRAF inhibitor resistance to melanoma cells through the suppression of BIM expression. Cancer Res. 2011;71:2750–60. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-2954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ngiow SF, Knight DA, Ribas A, McArthur GA, Smyth MJ. BRAF-targeted therapy and immune responses to melanoma. Oncoimmunology. 2013;2:e24462. doi: 10.4161/onci.24462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Balachandran VP, Cavnar MJ, Zeng S, Bamboat ZM, Ocuin LM, Obaid H, et al. Imatinib potentiates antitumor T cell responses in gastrointestinal stromal tumor through the inhibition of Ido. Nat Med. 2011;17:1094–100. doi: 10.1038/nm.2438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liu C, Peng W, Xu C, Lou Y, Zhang M, Wargo JA, et al. BRAF inhibition increases tumor infiltration by T cells and enhances the antitumor activity of adoptive immunotherapy in mice. Clin Cancer Res. 2013;19:393–403. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-12-1626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Donia M, Fagone P, Nicoletti F, Andersen RS, Hogdall E, Straten PT, et al. BRAF inhibition improves tumor recognition by the immune system: Potential implications for combinatorial therapies against melanoma involving adoptive T-cell transfer. Oncoimmunology. 2012;1:1476–83. doi: 10.4161/onci.21940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Koya RC, Mok S, Otte N, Blacketor KJ, Comin-Anduix B, Tumeh PC, et al. BRAF inhibitor vemurafenib improves the antitumor activity of adoptive cell immunotherapy. Cancer Res. 2012;72:3928–37. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-2837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Callahan MK, Masters G, Pratilas CA, Ariyan C, Katz J, Kitano S, et al. Paradoxical activation of T cells via augmented ERK signaling mediated by a RAF inhibitor. Cancer Immunol Res. 2014;2:70–9. doi: 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-13-0160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.