Abstract

Mammalian reproduction is critically dependent on the trophoblast cell lineage, which assures proper establishment of maternal-fetal interactions during pregnancy. Specification of trophoblast cell lineage begins with the development of the trophectoderm (TE) in preimplantation embryos. Subsequently, other trophoblast cell types arise with progression of pregnancy. Studies with transgenic animal models as well as trophoblast stem/progenitor cells have implicated distinct transcriptional and epigenetic regulators in trophoblast lineage development. This review focuses on our current understanding of transcriptional and epigenetic mechanisms regulating specification, determination, maintenance and differentiation of trophoblast cells.

Keywords: Placenta, Trophectoderm, Trophoblast, Transcription, Epigenetics

Introduction

Mammalian reproduction is uniquely characterized by the formation of placenta, a transient extraembryonic organ that mediates dynamic interaction between embryonic and maternal tissues and ensures successful development of the embryo proper. This intimate relationship between the embryo and mother is crucially dependent upon trophoblast cells as they mediate uterine implantation, initiate the process of placentation, and modulate vascular, endocrine, and immunological properties to support successful pregnancy. Improper TE specification, results in either arrested preimplantation development or defective embryo implantation (Cockburn and Rossant 2010, Pfeffer and Pearton 2012, Roberts and Fisher 2011, Rossant and Cross 2001), which are the leading causes of early pregnancy failure. After embryo implantation, defective development and function of trophoblast cells can lead to pregnancy failure and pregnancy-associated pathological conditions such as preeclampsia and intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR) (Myatt 2006, Pfeffer and Pearton 2012, Redman and Sargent 2005, Rossant and Cross 2001). Thus, a proper understanding of regulatory mechanisms that control specification, differentiation and function of trophoblast cell types is critical for advancement of infertility treatment, and the improvement of reproductive health. However, our scope for studying molecular mechanisms in regulating human trophoblast development are restricted due to ethical reasons and lack of proper model systems. Thus, the majority of our understanding of transcriptional mechanisms that regulate trophoblast development come from studies in rodent models.

Humans possess hemochorial placenta, in which the maternal blood is in direct contact with chorionic trophoblast cells, thereby facilitating nutrient exchanges between mother and the fetus. Interestingly, rodents, like mouse and rat, also possess hemochorial placenta (Rossant and Cross 2001, Soares, et al. 2012). Both rodent and human placentation is associated with invasion of trophoblast cells into the uterine wall and remodeling of uterine spiral arteries with invasive trophoblast cells. Despite several differences between rodent and human placentation (Carter 2007), they share similar regulatory mechanisms controlling placental development (Pfeffer and Pearton 2012, Rossant and Cross 2001). Therefore, analyses of mutant mice provide opportunities to understand functional importance of transcription factors in trophoblast development in hemochorial placentation. Successful derivation of trophoblast stem cells (TSCs) from rodent blastocysts (Asanoma, et al. 2011, Tanaka, et al. 1998) has also provided excellent cell-based systems for biochemical analyses including mechanistic studies on chromatin. The majority of the following discussion will be focused on our understanding from studies in rodent models.

Placental Development and Trophoblast Cell Types in Rodents and Human

Development of trophoblast cell lineage is a multi-step process (Fig. 1). Specification of the TE, one of the first two cell lineages within the preimplantation embryo (Kunath, et al. 2004, Rossant 2004), initiates trophoblast development. The other earliest lineage is the inner cell mass (ICM), which contributes to the embryo proper. Studies in rodent models indicate that trophectodermal cells, overlaying the ICM (polar TE), contribute to the majority of the trophoblast tissue and therefore are considered to be the TSC population (Rossant 2001). Establishment of bona fide TSC populations from rodent blastocysts (Asanoma, et al. 2011, Tanaka, et al. 1998) further supports this concept.

Figure 1. Different Stages of Mouse Trophoblast Development.

A, Establishment of the TE in preimplantation embryo initiates trophoblast development. B, Panels show location of trophoblast progenitors in E7.5 mouse conceptus. Panel (a) shows EPC in an E7.5 mouse embryo. Panel (b) shows a cross section of an E7.5 mouse embryo and a cartoon to indicate localization of primary TGCs and trophoblast progenitors. C, Cartoons indicate different regions of a mouse placenta (panel a) and differentiated trophoblast subtypes and their localization at the maternal-fetal interface (panel b).

Rodent blastocysts implant to the uterus through mural trophectodermal cells that are not in contact with the ICM (Fig. 1A). After implantation, cells of mural TE differentiate into post-mitotic primary trophoblast giant cells (primary TGCs) (Rossant and Cross 2001, Simmons and Cross 2005, Watson and Cross 2005). In contrast, proliferation and differentiation of polar TE results in the formation of the ectoplacental cone (EPC) and the chorion (Fig. 1B and (Simmons and Cross 2005), which arise during gastrulation (∼7.0-7.25 dpc). The EPC is developed from polar TE-derived extra-embryonic ectoderm (ExE) and contributes to the formation of the junctional zone, a compact layer of cells sandwiched between the labyrinth zone and the maternal decidua (Fig. 1C, panel a). Development of the labyrinth zone (Fig. 1C, panel a) starts with the attachment of the allantois to the chorion (Fig. 1B, panel b) at ∼E8.5 (Cross, et al. 2006, Simmons and Cross 2005). The chorion is a bilayered tissue with a layer of ExE-derived chorionic ectoderm (ChE), which contains trophoblast stem/progenitor cells. Subsequent to chorio-allantoic attachment, differentiation and morphogenesis of chorionic trophoblast progenitors and establishment of vascular network from the allantoic mesoderm (Cross, et al. 2006) leads to formation of the labyrinth zone, which mediates nutrient exchange between the fetus and mother.

Although the gross architecture of a rodent placenta has been known for many years, a more complete understanding of the hierarchy of the murine trophoblast cell lineage has only been obtained recently (Mould, et al. 2012, Simmons, et al. 2007, Ueno, et al. 2013, Uy, et al. 2002). Establishment of FGF4-dependent TSCs from dissociated ExEs/EPCs and ChEs from postimplantation mouse embryos (Tanaka, et al. 1998, Uy, et al. 2002) confirmed the presence of trophoblast cells with TSC-potential within those tissues. However, studies in mice predicted that a bonafide TSC population does not persist after the closure of EPC cavity (Uy, et al. 2002). Rather, recent studies (Mould, et al. 2012, Simmons, et al. 2007, Ueno, et al. 2013) in mice suggested the presence of specific progenitor populations within the junctional and labyrinth zones that could differentiate into specific specialized trophoblast cells of the mature placenta.

Development of the junctional zone from the EPC is associated with the derivation of multiple specialized trophoblast cells, namely (i) spongiotropblasts, (ii) glycogen cells and (iii) secondary TGCs [Fig. 1C, panel b (top)]. Based on the localization and gene expression patterns (Hu and Cross 2010, Simmons, et al. 2007), three subtypes of secondary TGCs were classified within the junctional zone and the decidua. These include the (i) maternal arterial canal associated TGCs (c-TGCs), (ii) parietal-TGCs (p-TGCs) lining the implantation site and (iii) spiral artery associated TGCs (SpA-TGC), which along with glycogen cells invade into the decidua and therefore are denoted invasive trophoblasts. Some of these invasive trophoblasts then associate with the uterine spiral arteries and remodel the arterial endothelium to establish endovascular trophoblast population. Interestingly, lineage-tracing studies indicated that these secondary TGCs could originate from different precursors. For example, PR domain zinc finger protein 1 (PRDM1)-positive proliferating cells within the spongiotrophoblasts are implicated (Mould, et al. 2012) as the precursors for the SpA-TGCs, whereas trophoblast specific protein alpha (Tpbpa)-positive precursors within the EPC could give rise to all three TGC subtypes (Hu and Cross 2010, Simmons, et al. 2007).

In addition to the above three TGC subtypes, maternal blood sinusoids within the labyrinth zone of mouse placenta contain the sinusoidal TGCs [s-TGCs; Fig. 1C, panel b (bottom)] (Hu and Cross 2010, Simmons, et al. 2007). Two layers of syncytiotrophoblasts (SynTB-I and SynTB-II, Fig. 1C, panel b) are also established within the labyrinth (Simmons, et al. 2008). The s-TGCs and SynTB-I/SynTB-II establish the trophoblast compartment for nutrient exchange within the rodent placenta. Interestingly, a recent study (Ueno, et al. 2013) implicated a population of Epcamhi proliferating progenitor cells as the precursors of all three trophoblast subtypes within the labyrinth. Collectively, these studies indicate a hierarchy of trophoblast development in rodents in which developmental stage-specific progenitors are derived from bonafide TSC populations. These stage-specific progenitors then differentiate to specialized trophoblast cells of a mature placenta.

Although we have obtained a more detailed knowledge of trophoblast development in rodents, our understanding of early stages of human trophoblast development is extremely poor due to ethical and experimental limitations. Human preimplantation embryos express several transcription factors that are associated with TE-development in rodents. However, a proliferating TSC/trophoblast progenitor population from human blastocyst or early postimplantation human placenta could not be established. Rather, our current understanding of trophoblast development in human came largely from studying placental tissues obtained from terminated or premature pregnancy (Maltepe, et al. 2010). Studies using first trimester human placentae demonstrated that development of proliferating villous cytotrophoblast cells (vCTBs) within chorionic villi (Figure 2A, B) is one of the early steps of human trophoblast development. Chorionic villi stem from the chorionic plate. Several of those villi anchor (anchoring villi) to the uterine decidua via formation of a cell column, derived from proliferating vCTBs (Fig. 2A). These anchoring villi thereby establish the maternal-fetal junction of a human placenta. In addition to anchoring villi, numerous floating villi are established (Fig. 2A). The vCTBs adapt two distinct differentiation fates in floating and anchoring villi to establish a mature placenta. The outer layers of both floating and anchoring villi contain SynTBs (Fig. 2A,B), which are established from fusion of cell cycle arrested vCTBs that were detached from the core mesenchyme. Thus, unlike in rodent placenta, a single layer of SynTBs is in contact with maternal blood in a human placenta.

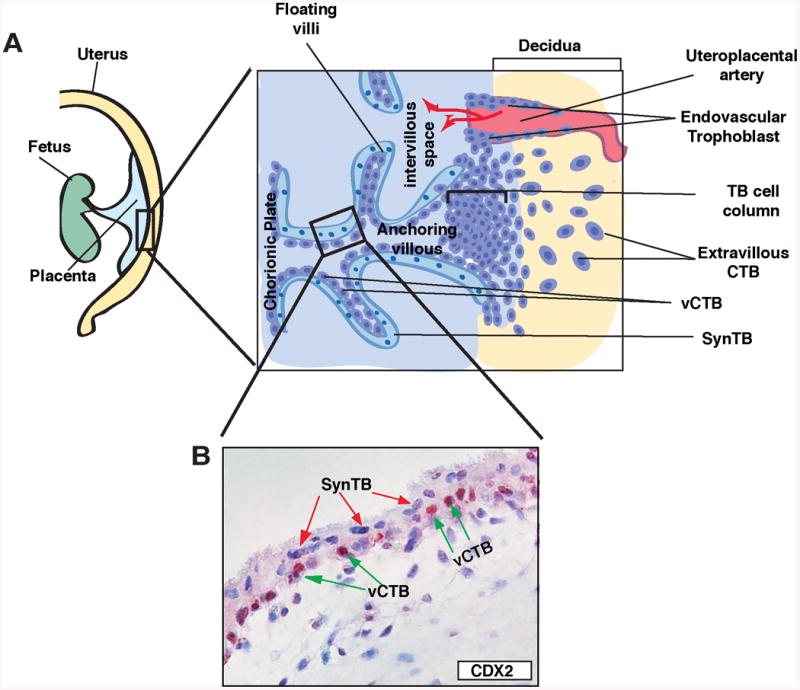

Figure 2. Trophoblast cells in a human placenta.

A, Cartoons show trophoblast cells at the maternal-fetal interface of a developing human placenta. Chorionic villi stem from the chorionic plate and contain two layers of trophoblast cells, the inner proliferating vCTBs and the outer SynTBs. In anchoring villi, maternal-fetal junctions are developed via formation of cell columns. Extravillous CTBs are immerged from the distal part of the cell column and invade into the decidua. Later, in 2nd trimester, a population of extravillous CTBs invades the uterine artery to establish endovascular trophoblasts. B, The micrograph shows two layers of trophoblasts (CTBs and SynTBs) of a first-trimester (9-week) human placenta. The mouse TSC-specific marker CDX2 is expressed in some CTBs but not in SynTBs.

At the interface of maternal-fetal junction within the anchoring villi, vCTBs adopt a different differentiation fate to establish migratory extravillous CTBs, which invade into the maternal decidua (Fig. 2A). Subsequently, a subset of the extravillous CTBs invades the uterine blood vessels. These endovascular trophoblast cells extensively remodel the vascular endothelium thereby establishing blood vessels with lining of maternal endothelium and fetal trophoblast cells. Invasion of extravillous CTBs into the decidua and establishment of endovascular trophoblast population ensure increasing supply of maternal blood to the intervillous space and enhanced nutrient exchange through the SynTBs. Defective invasion and endovascularization is considered to be the one of the major reasons for pregnancy associated disorders like Preeclampsia (Redman and Sargent 2005).

Differentiation of proliferating trophoblast progenitors in both rodents and humans leads to formation of SynTBs and invasive trophoblast cells that establish an efficient nutrient exchange interface to ensure fetal development. In addition to establishment of vascular connection and nutrient exchange, trophoblast cells secrete hormones, cytokines and angiogenic factors that alter the maternal endocrine and immune system to ensure successful progression of pregnancy. Defective development and function of trophoblast cell types may lead to multitude of pregnancy-associated disorders including preeclampsia, IUGR, pre-term birth, miscarriage and infertility.

Transcription Factors and Trophoblast Cell Lineage Development

Genetic and biochemical studies with rodent models have shown that the intricate process of trophoblast cell linage development is regulated by specific transcription factors/cofactors, which modulate gene expression (i) during TE-development from totipotent blastomeres in the preimplantation embryo, (ii) in trophoblast stem/progenitors cells after embryo implantation and at the onset of placentation, and (iii) during differentiation of trophoblast progenitors to specialized trophoblast subtypes in the developing/matured placenta. The next sections of this review will discuss transcription factors that regulate the individual steps of trophoblast development.

Transcription factors regulating TE-development in preimplantation embryo

Single cell transcriptome analyses (Burton, et al. 2013, Xue, et al. 2013, Yan, et al. 2013) confirmed that, during mouse and human preimplantation development, a minor wave of zygotic transcription starts within the one-cell stage embryo and a major wave of transcription starts in the blastomeres of two to four-cell stage embryos. Despite this early induction of zygotic transcription, blastomeres are totipotent at these developmental stages (Tarkowski and Wroblewska 1967, Veiga, et al. 1987). In mice, beginning at the late eight-cell stage, blastomeres are polarized (Johnson and Ziomek 1981) and allocated to inside and outside positions of the embryo. Subsequently, distinct transcriptional programs are established in outside versus inside cells. Expression of TE-specific genes are induced in outside cells and are reduced in inside cells of late eight- to sixteen-cell stage embryos, indicating an onset of TE-specification at these developmental stages (Home, et al. 2012, Kunath, et al. 2004, Rossant 2004, Zernicka-Goetz 2005, Zernicka-Goetz, et al. 2009). However, blastomeres at these developmental stages are still plastic and could contribute to both TE and ICM lineages. The determination of the TE-lineage happens at the blastocyst stage and is associated with the formation of the blastocoel cavity that separates the TE from the ICM lineage (Pfeffer and Pearton 2012). Thus, transcriptional regulation of TE development in preimplantation embryos can be divided into two phases, (i) specification phase (a nascent plastic stage when TE-specific transcriptional program is being established within the outer blastomeres) and (ii) determination phase (when functional specificity is established within the TE lineage allowing segregation from the ICM lineage) (Fig. 3).

Figure 3. Transcription factors regulating TE-development in mouse preimplantation embryo.

Blastomeres in early stage (2-8 cell) embryos are considered to be totipotent. However, several TE-specific factors including TEAD4 are induced during zygotic gene activation. Beginning late 8-cell stage, cells are located in an inside vs. outside position instigating TE-specification, which continues until the TE-determination phase. The determination phase ensures the development of the functional TE-lineage in a matured blastocyst. Transcription factors that are considered to be important at different stages of TE-development are indicated on top.

Studies with mutant mouse embryos and mouse TSCs implicated transcription factors, like Caudal type homeobox protein-2 (CDX2), GATA binding protein 3 (GATA3), transcription factor AP-2 gamma (TCFAP2C) and TEAD4, in regulating proper execution of specification and determination phases during TE-development (Choi, et al. 2012, Home, et al. 2009, Nishioka, et al. 2008, Niwa, et al. 2005, Ralston, et al. 2010, Yagi, et al. 2007). CDX2 was the first transcription factor, specifically implicated in TE development. CDX2 is ubiquitously expressed at the eight-cell stage. However, during the morula to blastocyst transition CDX2 becomes restricted to the outer TE lineage (Dietrich and Hiiragi 2007, Zernicka-Goetz, et al. 2009). Interestingly, lack of CDX2 in mouse embryos does not prevent blastocyst formation. Embryos lacking CDX2 fail to maintain a blastocoel cavity and are unable to implant (Strumpf, et al. 2005). Thus, CDX2 function seems to be essential for maintenance of a functional TE rather than specification of the TE-lineage from totipotent blastomeres. However, gain-of-function analyses in mouse embryonic stem cells (ESCs) showed that ectopic induction of CDX2 alone could promote a TSC-like fate in ESCs, indicating that, CDX2 function could contribute to the specification of the TE lineage and other factors might compensate the loss of CDX2 during specification of the TE-lineage (Nishiyama, et al. 2009).

Other transcription factors, such as GATA3, may compensate for CDX2 during development of the trophoblast lineage (Ralston, et al. 2010). Expression analyses of GATA3 in mouse embryos showed that both GATA3 and CDX2 follow a similar expression pattern during early mouse development (George, et al. 1994, Home, et al. 2009, Ralston, et al. 2010). RNAi-mediated knock down of GATA3 expression in mouse preimplantation embryos impairs a TE-specific transcriptional program and partially inhibits the morula to blastocyst transition (Home, et al. 2009). Furthermore, ectopic induction of GATA3 in mouse ESCs could promote a trophoblast fate (Ralston, et al. 2010). However, unlike CDX2, GATA3 induction in ESCs does not restrict them in a self-renewing TSC-like state, but rather promotes continuation of trophoblast differentiation (Ralston, et al. 2010). Thus, GATA3 might function both during TE-development as well as subsequent differentiation of other trophoblast cell types.

In preimplantation mouse embryos, TEAD4, a member of the TEA domain containing transcription factor family, regulates transcription of both Cdx2 and Gata3 by physically occupying their chromatin domains (Home, et al. 2012, Nishioka, et al. 2008, Ralston, et al. 2010, Yagi, et al. 2007). Loss of TEAD4 in mouse embryos prevents establishment of a TE-specific transcriptional program as characterized by loss of other TE-specific factors like CDX2 and GATA3 (Nishioka, et al. 2008, Ralston, et al. 2010, Yagi, et al. 2007). Hence, TEAD4 is indicated as the upstream factor to initiate expression of CDX2, GATA3 and other key factors for TE-specification. Furthermore, conserved nature of TEAD4 expression within mammalian TE-lineage (Home, et al. 2012) indicates that TEAD-mediated TE-specification might be a common event during preimplantation development in several mammals.

Alternative mechanisms were proposed on how TEAD4 mediates its function during preimplantation lineage development. TEAD4 is expressed in early totipotent blastomeres and is also expressed in the ICM lineage of a blastocyst. Thus, it is intriguing to understand how TEAD4 specifically establishes a TE-specific developmental mechanism. The initial model (Nishioka, et al. 2009) of TEAD4 function indicates that the hippo signaling pathway alternatively regulates nuclear access of YAP, a TEAD4 cofactor, between outer vs. inner blastomeres, with outer blastomeres having nuclear YAP and inner blastomeres lacking nuclear YAP. The model proposed that altered nuclear localization of YAP modulates TEAD4 transcriptional activity in outer vs. inner blastomeres (Cockburn, et al. 2013, Hirate, et al. 2013, Leung and Zernicka-Goetz 2013, Lorthongpanich, et al. 2013, Nishioka, et al. 2009). However, comparative analyses of endogenous TEAD4 expression in blastocysts from multiple mammalian species indicated that cells of the ICM lineage largely lack nuclear TEAD4, thereby compromising transcription of TEAD4 target genes (Home, et al. 2012). In contrast, cells of the TE-lineage maintain nuclear TEAD4, thereby allowing chromatin occupancy at target genes and regulating their transcription. Thus, an alternate hypothesis is proposed indicating that subcellular localization pattern of TEAD4 itself is important in specifying TE-specific transcriptional program in preimplantation embryos (Home, et al. 2012, Saha, et al. 2012). Another recent study (Kaneko and DePamphilis 2013) indicated that TEAD4 could alter the mitochondrial function and regulate oxidative phosphorylation in preimplantation embryos. However, during preimplantation development major shift of energy metabolism from anaerobic to oxidative phosphorylation as well as mitochondrial maturation begins at the blastocyst stage (Houghton, et al. 1996, Leese 2012), whereas energy metabolism in earlier stage embryos are mostly anaerobic. Thus, the TEAD4-mediated regulation of oxidative phosphorylation might be more important during the TE-determination phase rather than the TE-specification phase. Given the essential role of TEAD4 in TE-development, further research is necessary to make a definitive conclusion about the mode of TEAD4 function.

Along with TEAD4, other transcription factors such as TCFAP2C, KLF5 and SOX2 may function in TE-specification and blastocyst formation. TCFAP2C was shown to be important for blastocoel formation and establishment of the trophectoderm epithelium during mouse preimplantation development (Choi, et al. 2012). Interestingly, genome wide analyses revealed that a large number of genes in TSCs could be common targets for both TEAD4 and TCFAP2C (Home, et al. 2012). Thus, specification of the TE-lineage might be coordinated by both TCFAP2C and TEAD4. The cooperative interaction between TCFAP2C and CDX2 has also been indicated to be important during TE development (Kuckenberg, et al. 2010).

Kruppel-like factor 5 (KLF5) (Lin, et al. 2010) and SRY-box 2 (SOX2) (Keramari, et al. 2010) are also implicated in TE-development. However, in contrast to TEAD4, TCFAP2C, CDX2 and GATA3, the transcription factors KLF5 and SOX2 are important for formation of both ICM and TE lineages (Lin, et al. 2010). Loss of Klf5 expression prevents mouse development beyond the blastocyst stage and defective TEs function is implicated for this phenotype. However, Klf5 also regulates expression of key pluripotency factors like Oct4 and Nanog in the ICM lineage. Therefore, a cell autonomous function of KLF5 is proposed to promote proper transcriptional program in both TE and ICM lineage cells (Lin, et al. 2010). Like KLF5, SOX2 also regulates transcriptional programs in both TE and ICM lineages (Adachi, et al. 2013, Keramari, et al. 2010). It has been shown that depletion of both maternal and zygotic SOX2 reduces expression of several TE-specific genes (Keramari, et al. 2010), including TEAD4. Thus, similar to KLF5, a cell autonomous function of SOX2 might be important to promote transcriptional program at the onset of TE-specification (Fig. 3).

Transcription factors involved in proliferation and maintenance of trophoblast stem/progenitors cells after embryo implantation

Another essential stage of trophoblast lineage development is maintenance and expansion of trophoblast stem/progenitor cells in the early postimplantation embryo. In mice, eomesodermin (EOMES) expression is detected in the TE of blastocysts (Strumpf, et al. 2005) and also within the trophoblast stem/progenitors of the ExE and EPC. Although EOMES-null mouse embryos form blastocysts and undergo implantation, they die at E6.0-E7.5 due to improper differentiation of TE and defective expansion of the ExE (Strumpf, et al. 2005). Several other transcription factors have also been implicated in regulating trophoblast development in early postimplantation embryos. These include two ETS (E twenty-six)-domain containing transcription factors, E74-like factor 5 (ELF5) and ETS2. Both ELF5 (Donnison, et al. 2005, Ng, et al. 2008) and ETS2 (Georgiades and Rossant 2006) are expressed in the trophoblast stem/progenitor cells within the ExE and are essential for their maintenance (Ng, et al. 2008, Wen, et al. 2007). ExE development is defective in both ELF5 and ETS2-null embryos causing defective reciprocal interactions of ExE with the embryonic ectoderm leading to impaired gastrulation, embryo patterning and embryonic death (Donnison, et al. 2005, Georgiades and Rossant 2006, Polydorou and Georgiades 2013). Maintenance and differentiation of trophoblast stem/progenitor cells within the ExE is also regulated by transcription factor POU class 5 homeobox 1 (POU5F1) (Sebastiano, et al. 2010). POU5F1-null embryos fail to establish a normal maternal-embryonic interface due to compromised ExE development and lack of EPC formation (Sebastiano, et al. 2010). Furthermore, similar to ELF5 and ETS2 and POU5F1loss leads to early gastrulation defect (Sebastiano, et al. 2010).

The involvement of multiple transcription factors in early postimplantation trophoblast development raises the question, “how does a specific factor contribute to the maintenance or expansion of trophoblast stem/progenitor cells within ExE and EPC lineages?” One possible explanation is that these factors coordinate to maintain expression of core TSC-specific transcription factors, like CDX2, GATA3, and TCFAP2C. Although these core factors are induced in early preimplantation embryos, their expression is maintained within the ExE and EPCs (Auman, et al. 2002, Ralston, et al. 2010, Strumpf, et al. 2005). It has also been shown that disruption of ELF5, ETS2 and POU5F1 leads to loss of these core factors (e.g., CDX2) within the developing postimplantation embryo (Georgiades and Rossant 2006, Sebastiano, et al. 2010). These findings indicate that development, maintenance, expansion and function of trophoblast stem/progenitor cells within the rodent postimplantation embryo are regulated by a transcriptional circuitry involving several transcription factors.

Interestingly, similar to the trophoblast stem/progenitor cells of a developing rodent placenta, proliferating vCTBs of first trimester human placenta express key transcription factors such as CDX2 and EOMES (Fig. 2B) (Hemberger, et al. 2010). However, in vitro culture of isolated vCTBs leads to cell cycle arrest. Therefore, mechanistic studies to address role of specific transcription factors in self-renewal or differentiation of human trophoblast progenitors could not be performed using the primary vCTBs. Rather, a CDX2 expressing progenitor population within the chorionic mesenchyme of human placenta has been identified (Genbacev, et al. 2011), which in selective culture conditions adopt cell fates similar to differentiated trophoblast populations of chorionic villi. Still, the true nature of the human trophoblast stem/progenitor cells is yet to be defined and a model system similar to rodent TSCs is yet to be established. The lack of a proper model system has limited our understanding of transcriptional mechanisms that control proliferation and differentiation of human trophoblast progenitors.

Transcription factors regulating development and function of differentiated trophoblast cells

In rodents, successful completion of placentation and establishment of maternal-fetal interface is associated with development of multiple specialized trophoblast subtypes within the junctional and labyrinth zones. In humans, these processes involve differentiation of vCTBs to SynTBs and extravillous CTBs. In contrast to the proliferating trophoblast stem/progenitor population, terminally differentiated trophoblast cell types exhibit cell cycle arrest, morphological alterations, cell-cell fusion and undergo cell migration to invade the maternal decidua. However, identification of specific progenitor populations within the mouse spongiotrophoblasts and labyrinth (Mould, et al. 2012, Simmons, et al. 2007, Ueno, et al. 2013) indicates that proliferating, undifferentiated trophoblast cell populations are maintained within a maturing rodent placenta. Whereas such a progenitor population is yet to be identified in maturing human placenta, the continuous growth of human placenta during 2nd and 3rd trimester and expansion of chorionic villi imply presence of proliferating trophoblast population throughout gestation. Thus, a fine balance between cell proliferation and cellular differentiation is important during development of differentiated trophoblast populations within maturing/mature placenta and understanding transcriptional mechanisms that controls this balance is of major importance to understand trophoblast development.

Establishment of chorioallantoic placenta is one of the key steps for successful placentation (Cross, et al. 2006, Simmons and Cross 2005) in rodents. During chorionic placenta development, the allantoic mesoderm attaches with the chorion and the chorion collapses onto the ectoplacental plate. Subsequently, invasion of the chorionic plate by the allantoic blood vessels and trophoblast syntialization establish the labyrinthine layer (Cross, et al. 2006, Simmons and Cross 2005, Simmons, et al. 2008). Analyses of mouse mutants have shown that a number of transcription factors like, distal-less homeobox 3 (DLX3) (Morasso, et al. 1999), Ets2 repressor factor (ERF) (Papadaki, et al. 2007) and ovo-like 2 (OVOL2) (Unezaki, et al. 2007) are important for proper chorioallontic fusion and labyrinth formation.

The importance of spatio-temoral regulation of trophoblast cell proliferation during rodent labyrinth formation is better understood from mouse models with mutations in transcription factor Glial cell missing 1 (GCM1), nuclear hormone receptors, ERR-β and tumor suppressor retinoblastoma (Rb). Both GCM1 and ERR-β are expressed within the trophoblast progenitors of the chorionic plate. Analyses in mutant mice (Anson-Cartwright, et al. 2000) and in TSCs (Hughes, et al. 2004) indicated that GCM1 is important to induce cell cycle arrest and formation SynTBs from chorionic trophoblast progenitors. In contrast ERR-β is important to maintain proliferating diploid trophoblast progenitors in a developing placenta (Luo, et al. 1997). The Err-β-mutant mice die at mid gestation (E9.5-E10.5) and the extraembryonic tissues in the mutant embryos are characterized with depletion of diploid trophoblast cells and increase in secondary TGCs. The interrelationship of GCM1 and ERR-β function during labyrinth formation is further evident from studies with Erf-mutant mice (Papadaki, et al. 2007), in which chorionic trophoblast cells lack GCM1 expression and maintain Err-β expression leading to impaired labyrinth formation. Interestingly, in contrast to Err-β mutant mice, Rb-mutant mice exhibit presence of an excessive amount of proliferating cells within the labyrinth and decreased syncytialization (Wu, et al. 2003), reiterating the importance of proper regulation of cell proliferation during trophoblast differentiation in labyrinth zone.

During labyrinth formation, transcriptional mechanisms are also important for establishment of proper vascular network. Evidence of this came from mice with mutations in AP1 family of transcription factors and homeobox transcription factor ESX1. AP-1 factors are dimeric complexes of Jun (c-Jun, JunB, and JunD) homodimers and Jun heterodimers with FOS (c-FOS, FOSB, FRA-1, and FRA-2). Studies in mutant mouse models indicated that FRA1 (Schreiber, et al. 2000) and JUNB (Schorpp-Kistner, et al. 1999) are crucial for proper vascular development within the labyrinth zone. Loss of these factors leads to embryonic death due to impaired vascularization in placental labyrinth. Studies with Esx1-mutant mice (Li and Behringer 1998) also provided evidence that trophoblast cells play an active role during vascular remodeling within the labyrinth zone. Esx1 is an imprinted gene and in mouse labyrinth it is exclusively expressed in trophoblast population. However, Esx1-mutant mice show an IUGR-like phenotype (Li and Behringer 1998) primarily due to defective fetal vessel growth within the layrinth zone. Collectively, studies from mutant mice demonstrated the importance of individual transcription factors for proper trophoblast differentiation and vascularization within the labyrinth zone.

Specific transcription factors have also been implicated in the development and function of differentiated trophoblast subtypes of the junctional zone. For example, heart and neural crest derivatives expressed transcript 1 (HAND1) (Riley, et al. 1998) and PRDM1 (Mould, et al. 2012) are expressed within the trophoblast progenitors of the EPC and are important for TGC development. Whereas, achaete-scute complex homolog 2 (ASCL2) is essential for spongiotrophoblast development (Tanaka, et al. 1997).

One important difference during early vs. late stages of trophoblast development is exposure to altered oxygen level. Trophoblast development during early post-implantation embryo occurs in the presence of low oxygen, whereas the later phases of trophoblast development occurs in the presence of increased levels of oxygen (Adelman, et al. 2000, Genbacev, et al. 1997, Rodesch, et al. 1992). The hypoxia inducible factors (HIFs) are essential for proper differentiation and function of trophoblast cells. HIFs are heterodimeric proteins consisting of an alpha (HIFα) and beta (ARNT) subunits. The loss of ARNT and HIF1α within mouse placenta impairs spongiotrophoblast and TGC differentiation (Cowden Dahl, et al. 2005) indicating, that HIF-signaling is important to regulate cell fate decision during differentiation of trophoblast progenitors (Fryer and Simon 2006). In addition to the defective trophoblast differentiation, loss of HIF function alters placental ultrastructure and leads to defective vasculature at placentation sites (Cowden Dahl, et al. 2005). It has also been shown that HIFs regulate expression of histone deacetylases (HDACs) in TSCs and crosstalk between the HIFs and the HDACs might balance proper TSC differentiation (Maltepe, et al. 2005). Thus, during placental development, HIF-mediated transcriptional mechanisms are important for a multitude of events including placental morphogenesis, vascular remodeling, and trophoblast fate adoption.

Polyploidy is another unique characteristic of the differentiated TGC population, although the importance of endoreplication in TGCs is poorly understood. Nevertheless, recent studies with the atypical E2F family of transcription factors, which regulate polyploidy, provided important insight during mouse placental development. E2F family consists of canonical E2F activators (E2F1, E2F2, E2F3a and E2F3b) and E2F repressors [canonical (E2F4, E2F5 and E2F6) and atypical (E2F7 and E2F8)]. Analyses of mouse mutants indicated that atypical E2F7/E2F8 repressors are essential for proper placental development and function (Ouseph, et al. 2012). Combinatorial loss of E2f7 and E2f8 leads to a severely compromised placental development which is associated with altered proliferation and differentiation of multiple differentiated trophoblast subtypes, including TGCs and spongiotrophoblasts.

Studies in knockout mice have implicated other transcription factors and cofactors such as PPAR-gamma, GATA2/GATA3, CITED1, CITED2, and TLE3 (Barak, et al. 1999, Gasperowicz, et al. 2013, Ma and Linzer 2000, Ma, et al. 1997, Parast, et al. 2009, Ray, et al. 2009, Rodriguez, et al. 2004, Withington, et al. 2006) in trophoblast development and function. Table 1 summarizes several transcription factors and cofactors that regulate development of specific trophoblast subtypes or their function. Many of the factors that are important for mouse trophoblast development are conserved in human trophoblast cells and mediate similar functions. For example, GCM1 was shown to regulate expression of retroviral syncytin genes in human trophoblast cells to promote syncytiotrophoblast formation (Liang, et al. 2010, Yu, et al. 2002). Similarly, GATA factors, FOSL1, and HIFs are implicated in regulating critical aspects of trophoblast differentiation and invasion in both human and rodents (Cheng and Handwerger 2005, Renaud, et al. 2013) (Kent, et al. 2011, Renaud, et al. 2013). However, our understanding of the global transcriptional circuitry involving these transcription factors during trophoblast development is incomplete. Future research is necessary to identify common transcriptional pathways that regulate both rodent and human trophoblast differentiation. Such studies will be important to establish a better understanding of the global transcriptional circuitry in trophoblast progenitors vs. differentiated trophoblast cells. This will serve as an important step to further comprehend the interrelationship between trophoblast development and pregnancy associated disorders.

Table 1. Key factors that are implicated in proper development and function of differentiated trophoblast cells via gene-knockout studies in mice.

| Factor/Cofactor | Family and mode of Function | Functional Importance | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| ASCL2/MASH2 | A basic helix-loop-helix (bHLH) TF; Activator of transcription | Important for Spongiotrophoblast development | Tanaka et al., 1997 |

| BLIMP1/PRDM1 | A zinc finger transcriptional repressor of transcription | Required for differentiation of endovascular TGCs | Mould et al., 2012 |

| CITED1 | An Asp/Glu-rich C-terminal (CITED) domain transcriptional coactivator. | Proper development of the spongiotrophoblast layer | Rodriguez et al., (2004) |

| CITED2 | (CITED) domain transcriptional coactivator | Proper development of spongiotrophoblast, TGCs and invasive trophoblasts | Withington et al., (2006) |

| DLX3 | Homeodomain TF, | Labrynth formation, placental vascularization | Morasso et al., (1998) |

| E2F7/E2F8 | Winged-helix; transcriptional repressor of transcription | Proper development of spongiotrophoblast and TGC layer | Ouseph et al., 2012 |

| ERF | Transcriptional repressor | chorioallantoic attachment, and absence of labyrinth | Papadaki et al., (2007) |

| FRA1 | AP-1 family member TF;Activator of Transcription | Essential for proper labyrinth formation and placental vascularization | Schreiber et al., (2000) |

| GATA2/GATA3 | GATA binding factors, Activator and repressor of transcription | Proper function and hormone production in TGCs, Vascularization at placentation site | Ma et al., 1997 |

| GCM1 | TF; with a gcm-motif, Activator of transcription | Essential for labyrinth formation and syncytiotrophoblast | Anson-Cartwright et al., (2000) |

| TLE3 | Transcriptional corepressor | proper differentiation into secondary TGCs | Gasperowicz et al., (2013) |

| Hand1 | bHLH TF; Activator and repressor of transcription | Regulates TGC formation | Riley et al. (1998) Cross et al., (1995). |

| HIFs | bHLH TFs, Activator of transcription | Proper development of multiple trophoblast subtypes, trophoblast invasion, placental vascularization | Cowden Dahl et al., (2005),Maltepe et al., (2005) |

| I-mfa | bHLH TF; Transcriptional repressor | TGC differentiation and survival | Kraut et al. (1998) |

| JunB | AP-1 family member TF; Activator of Transcription | Essential for proper labyrinth formation and vascularization | Schorpp-Kistner et al., 1999 |

| Ovol2 | Zinc-finger TF, Transcriptional activator and repressor. | Labrynth formation, placental vascularization | Unezaki et al., (2007) |

| PPARγ | Ligand-activated nuclear hormone receptor; Activator of transcription | Proper differentiation of progenitors and proper development of labyrinth and giant cell layer | Barak et al., (1999),Parast et al., (2009) |

Epigenetic Regulation of Gene Expression during Trophoblast Development

The development of distinct cell types from progenitors is often modulated by epigenetic modifications that alter nucleoprotein structure. During cell-lineage commitment, transcription factors promote expression of certain genes by recruiting specific epigenetic regulators at their chromatin domains. Alternatively, epigenetic regulators might facilitate recruitment of a transcription factor at a specific locus. Altered DNA methylation is an epigenetic mode of regulating gene expression. Other epigenetic regulators include factors that modulate histone modification patterns at chromatin domains, as well as chromatin organizers and chromatin remodeling factors. The next section will briefly describe these epigenetic modifications in the context of trophoblast development.

DNA Methylation and Trophoblast Development

In mammals, DNA methylation is mediated by a group of enzymes called, DNA methyltransferases (DNMTs). Among DNMTs, DNMT1 methylates post-replication, hemi-methylated DNA strands to restore global DNA methylation patterns. In contrast, DNMT3A and DNMT3B could mediate de novo methylation at CpG islands near the promoter region of a gene instigating transcriptional silencing. The de novo methylation by DNMT3A and DNMT3B is stimulated by their direct interaction with another structurally similar protein, DNMT3L, which by itself lacks DNA methyltransferase activity (Hata, et al. 2002). Analyses in mouse preimplantation embryos indicated that the DNA methylation patterns vary between the ICM and the TE (Santos, et al. 2002). The ICM development is associated with de novo DNA methylation. In contrast, the TE lineage virtually lacks the DNA methylation, indicating that the initial specification of the TE is not dependent upon DNA methylation. Furthermore, preimplantation mouse development is not impaired in the absence of Dnmt1, Dnmt3a and Dnmt3b (Sakaue, et al. 2010). Thus, DNA methylation is not essential for TE development. Rather, inequality of DNA methylation has been shown to be a critical epigenetic mechanism to establish distinct transcriptional programs in embryonic versus extraembryonic tissues during early postimplantation development. For example, loss of DNA methylation at key trophoblast genes, like ELF5, induces their transcription and maintains a TSC-specific transcriptional program within extraembryonic tissues of an early postimplantation mouse embryo (Ng, et al. 2008), whereas transcriptional silencing via DNA methylation prevents activation of trophoblast genes in embryonic tissues.

Throughout embryonic development, the global DNA hypomethylation is maintained within all extraembryonic lineages, including trophoblast cells (Chapman, et al. 1984, Rossant, et al. 1986). However, DNA methylation is important for normal proliferation and differentiation of trophoblast cells within the developing placenta. Genetic inactivation of Dnmt1 and Dnmt3a/Dnmt3b in mouse placenta leads to defective chorioallantoic attachment (Li, et al. 1992, Okano, et al. 1999). Loss of Dnmt3l in mouse placenta also leads to defective chorioallantoic attachment and prevents labyrinth formation (Arima, et al. 2006, Bourc'his, et al. 2001) and Dnmt3l-null placentae exhibit an abnormal spongiotrophoblast layer and higher levels of TGCs (Arima, et al. 2006). Thus, fine-tuning of DNA methylation at trophoblast chromatin is critical to regulate proper differentiation of the trophoblast progenitor.

Another unique feature in trophoblast cells is incorporation of regulatory regions/genes of retroviral origin (Chuong, et al. 2013, Haig 2012). These retroviral genes and elements are indicated to be crucial for placental evolution and function (Chuong, et al. 2013, Haig 2012, 2013). For example, expression of syncytins, which are retroviral envelope proteins, is essential to promote fusion of mononuclear trophoblasts and formation of syncytiotrophoblast layer of both human (Frendo, et al. 2003, Mi, et al. 2000) and rodent (Dupressoir, et al. 2009, Dupressoir, et al. 2011) placentas. Also, other genes of retrotransposon origin such as Peg10, Rtl1 are essential in mouse placental development (Ono, et al. 2006, Sekita, et al. 2008). Intriguingly, these genes of retroviral origin are specifically expressed within trophoblast cells and are repressed in most embryonic tissues (Ono, et al. 2001, Ono, et al. 2006, Sekita, et al. 2008) and several other genes use retroviral regulatory elements to produce placenta-specific transcripts (Chuong, et al. 2013). The reason behind the trophoblast-specific expression of retroviral genes is unknown. Probably, the global DNA-hypomethylation within trophoblast cells create a permissive epigenetic state for elevated transcription of these retroviral genes, thereby facilitating adaptation, evolution, and function of mammalian placenta.

Histone Modifications and Trophoblast Development

Along with DNA-methylation, post-translational modifications (PTMs) of histones have also been implicated in orchestrating transcriptional program during trophoblast development (Table 2). Importance of histone PTM during specification of TE lineage came from a study (Torres-Padilla, et al. 2007) showing that alteration of histone H3 arginine 26-methylation (H3R26me) is associated with TE versus ICM commitment of a blastomere. The study showed that overexpression of coactivator-associated arginine methyltransferase 1 (CARM1), which induces higher levels of H3R26me, facilitates up-regulation of Nanog and Sox2 gene expression and facilitates ICM fate in a blastomere. These studies indicate that suppression of histone H3 arginine methylation could be important to promote the TE-specific transcriptional program in blastomeres. However, additional experimentation is necessary to establish a direct link between suppression of histone H3 arginine methylation and trophoblast development. Rather, histone arginine methylation is necessary for maintenance of trophoblast progenitors in the postimplantation mouse embryo as gene knockout of histone arginine methyltransferase gene, Prmt1, impairs EPC formation in mice (Pawlak, et al. 2000).

Table 2. Summary of Histone Modifying Enzymes that are Implicated in Trophoblast Development.

| Enzyme | Function | Loss of function phenotype | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| CARM1 | Histone arginine methyltransferase (H3R26me) | Increase in H3R26 methylation; Increased expression of Nanog and Sox2; Altered cell-fate; Propensity to contribute to ICM | Torres-Padilla et al., 2007. |

| EED | PRC2 core component | Ectopic induction represses TE-specific regulators and inhibits implantation; Null embryos die at midgestation and show improper differentiation of TGCs | Saha et al., 2012, Wang et al., 2002 |

| ESET | Histone lysine methyltransferase (H3K9me3) | Peri-implantation lethality due to defective ICM development | Dodge et al. 2004, Yeap et al., 2009, Yuan et al., 2009. |

| EZH2 | A PRC2 core component; Regulates H3K27 methylation. | Early embryonic lethality with impairment of both embryonic and extraembryonic tissue development | O'Carrol et al., 2001 |

| G9a | Histone H3K9 methyltransferase | Embryonic lethality with impaired chorioallantoic fusion | Tachibana et al., 2002 |

| KDM6B | Histone H3K27 demethylase | Delayed blastocyst maturation and loss of TE function resulting in defective embryo implantation | Saha et al., 2012 |

| LSD1 | Histone H3K4 demethylase | Impaired differentiation and migration of TSCs | Zhu et al., 2014 |

| MYST1/MYST2 | Histone H3K14 acetyltransferase | Lethality after embryo implantation; Defective chorioallantoic attachment | Thomas et al., 2008, Kueh et al., 2011 |

| SUV39H1 | Histone lysine methyltransferase (H3K9me3) | Loss of TE lineage plasticity due to altered H3K9Me3 modification | Alder et al., 2010, Rugg-Gunn et al., 2010. |

| SUZ12 | A PRC2 core component; Regulates H3K27 methylation. | Early embryonic lethality with impairment of both embryonic and extraembryonic tissue development | Pasini et al., 2004 |

Histone H3 lysine 9 tri-methylation (H3K9Me3) is another histone modification that is implicated in preimplantation mouse development. H3K9Me3 modification is regulated by multiple histone methyltransferass, including ERG-associated protein with SET domain (ESET). Genetic studies in mice showed that, in ICM-lineage cells, ESET is essential to incorporate H3K9Me3 modification within the chromatin domains of key TE-specific genes, thereby suppressing their expression and the induction of the TE-fate (Yeap, et al. 2009, Yuan, et al. 2009). In contrast, another histone H3K9 methyltransferase, suppressor of variegation 3-9 homolog 1 (SUV39H1), has been implicated to suppress ICM-specific genes within the TE-lineage cells (Alder, et al. 2010, Rugg-Gunn, et al. 2010). Thus, specification of TE vs. ICM lineage is critically dependent upon well-regulated machinery, which ensures selective gene expression by regulating chromatin-domain specific H3K9Me3 incorporation. Deletion of another H3K9 methyltransferase, G9a in mouse embryo leads to embryonic lethality with impaired chorioallantoic fusion (Tachibana, et al. 2002), indicating that chromatin domain-specific incorporation of H3K9Me3 mark is also important during later stage of trophoblast development.

H3K27Me3 is another histone modification implicated in transcriptional repression of TE-specific genes within the ICM lineage cells (Saha, et al. 2013). H3K27Me3 modification is regulated by polycomb repressor 2 (PRC2) complex. Recently, it was reported that proper regulation of H3K27Me3 incorporation at TE-specific genes is important during preimplantation lineage development. Loss of H3K27Me3 incorporation at the TE-specific genes like Cdx2 and Gata3 is essential for proper development of the TE lineage and embryo implantation (Saha, et al. 2013). Analyses in mouse embryos indicated that coordinated regulation of lysine-specific histone demethylase 6B and embryonic ectoderm development (EED), a core component of PRC2, ensures loss of He3K27Me3 incorporation at the chromatin domains of TE/TSC-specific genes (Rugg-Gunn, et al. 2010, Saha, et al. 2013). Although loss of H3K27Me3 modification promotes TE-specific gene expression, incorporation of H3K27Me3 may be important for proper development and differentiation of trophoblast progenitors. Analyses in mouse mutants revealed that loss of EED leads to improper development of secondary TGCs (Wang, et al. 2002). Furthermore, loss of other PRC2 core components, enhancer of zeste homolog 2 (EZH2) and suppressor of zeste 12 (SUZ12), leads to embryonic death at gastrulation due to improper development of both embryonic and extraembryonic tissues (O'Carroll, et al. 2001, Pasini, et al. 2004).

Trophectodermal cells within preimplantation mouse embryos are also enriched with histone H3/H4 acetylation and histone H3 lysine 4-methylation (H3K4me) (Gupta, et al. 2008, Ma and Schultz 2008, Sarmento, et al. 2004, Wongtawan, et al. 2011). A recent study reported that Lysine-specific demethylase 1 (LSD1), which demethylates H3K4Me residue, regulates differentiation and migration of TSCs (Zhu, et al. 2014). However, functional importance of H3K4me or histone acetylation during TE development is yet to be established. Rather, mouse embryos lacking histone H3K14 acetyltransferase, MYST1 and MYST2, show impaired development after implantation along with defective chorioallantoic fusion (Kueh, et al. 2011, Thomas, et al. 2008), indicating that histone H3K14 acetylation could be an important epigenetic modification to control trophoblast differentiation.

Chromatin Remodeling Factors and Trophoblast Development

Analyses in mutant mouse embryos revealed that a subset of chromatin remodeling and/or chromatin organizer proteins are important for early trophoblast development. These include the SWI/SNF family of chromatin remodeling proteins, chromatin organizers such as SATB1 and SATB2, and an orthologue of the Drosophila nucleosome remodeling factor NURF301. This section of the review will discuss are current knowledge on the biological role of chromatin remodeling proteins in trophoblast development.

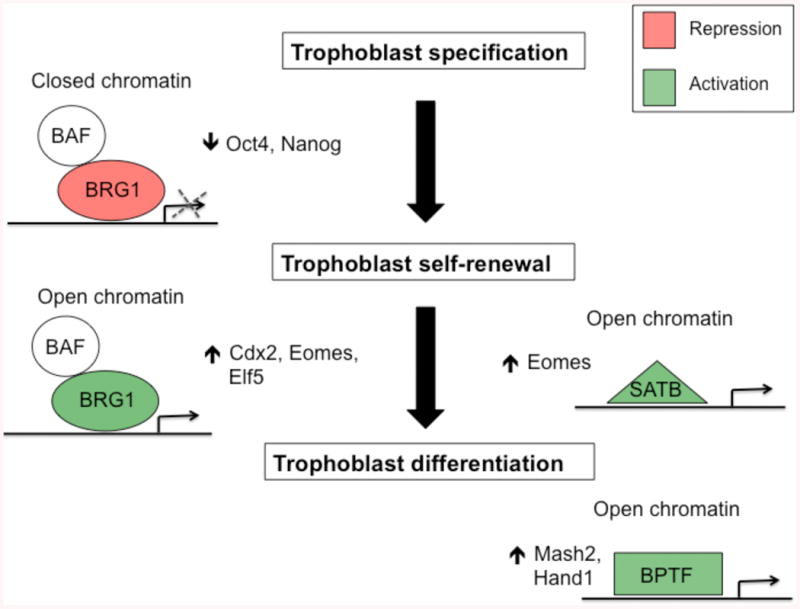

Functional studies in mice have established an important role for the SWI/SNF proteins BRG1, BAF47, and BAF155 in trophoblast development. Genetic ablation of Brg1, Baf47, and Baf155 results in developmental arrest around the blastocyst stage and failure to implant in utero (Bultman, et al. 2000, Guidi, et al. 2001, Kim, et al. 2001). Closer examination of mutant blastocysts in vitro revealed defects in hatching and/or failure to form outgrowth assays indicative of an abnormal trophoblast layer. Recent mechanistic studies have begun to shed some light on the underlying role of BRG1 in trophoblast development. For instance, chromatin immunoprecipitation on Chip (ChIP-Chip) and transcriptome analysis revealed that the pluripotency genes Oct4 and Nanog are bona fide targets of BRG1 in mouse blastocysts (Kidder, et al. 2009). Functional analysis further established that BRG1 cooperates with CDX2 to repress Oct4 in the trophoblast lineage (Wang, et al. 2010). Moreover, studies in Cdx2-inducible ESCs revealed that Oct4 and Nanog silencing is tightly associated with chromatin remodeling at key regulatory regions (Carey, et al. 2014), suggesting that BRG1-dependent chromatin remodeling activity is necessary for pluripotency gene silencing. Besides its repressive role in trophoblast development, BRG1 can also cooperate with EOMES and TCFAP2C to positively regulate Eomes, Elf5 and Cdx2 expression in undifferentiated TSCs (Kidder and Palmer 2010). Ablation of BRG1, EOMES and TCFAP2C resulted in loss of self-renewal and trophoblast differentiation. Altogether, these studies highlight a dual role for BRG1 in negatively regulating ESC genes and positively controlling TSC genes via interactions with distinct transcription factors in the trophoblast lineage.

Other putative chromatin regulators have also been implicated in trophoblast self-renewal. For example, the chromatin organizers SATB homeobox 1 (SATB1) and SATB2 have been shown to be essential for maintaining a stem-cell identity within rat TSCs (Asanoma, et al. 2012). Mechanistic analyses showed that loss of SATB proteins in TSCs resulted in reduced expression of Eomes and loss of TSC self-renewal. Along with TSC self-renewal, proper differentiation of the trophoblast lineage is imperative for development of a functional placenta. The bromodomain plant homeodomain transcription factor (BPTF), an orthologue of the Drosophila nucleosome remodeling factor NURF301, is essential for trophoblast differentiation in early postimplantation embryos (Goller, et al. 2008). BPTF-null embryos die before midgestation and are characterized with drastically reduced or absent EPCs. Several transcription factors important for trophoblast differentiation, including Ascl2 and Hand1, are downregulated in BPTF-null embryos, suggesting that BPTF may positively regulate the expression of core transcription factors necessary for differentiation and formation of a mature placenta. Future mechanistic studies should reveal the precise role of SATB proteins and BPTF in maintenance and differentiation of trophoblasts in vivo.

Discussion and future perspectives

The development of trophoblast lineage in a mammalian species is a multistage process and unique as well as overlapping transcriptional mechanisms are involved in regulating those multiple developmental stages. Defining these transcriptional mechanisms is important to better understand physiological processes that occur at the maternal-fetal interface. A better understanding of maternal-fetal interaction is necessary for success in assisted reproduction and to address therapeutic strategies for various pregnancy-associated complications such as IUGR, Preeclampsia, and pre-term birth. Stage-specific regulation of transcriptional mechanisms in trophoblast cells are often regulated by cellular signaling pathways that are instigated by growth factors, cytokines and reproductive hormones. Also, from an evolutionary perspective, the placenta is a highly active organ and placental structure and mode of function varies tremendously among different mammalian species. A major driving force behind this variation is adaptation of a species to the environment. Along with intrinsic signaling mechanisms, environmental factors might modulate transcriptional mechanisms during trophoblast development. As discussed above, a number of recent studies have enriched our understanding about transcriptional mechanisms during trophoblast development. However several limitations are also prominent.

Probably, the most obvious limitation in our understanding related to human trophoblast biology is absence of a proper cellular model to study regulatory mechanisms (including transcriptional mechanisms) controlling establishment, maintenance and differentiation of trophoblast progenitors. Although different alternative experimental approaches have been implemented to understand trophoblast development in human, the absence of a proper cellular model system greatly limits our ability to conceptualize importance of specific molecular mechanisms in pathological conditions, arising from defective trophoblast development.

Additional deficiencies in our understanding originate from the differential placental ultra-structures as well as different trophoblast populations among mammalian species. For example, elegant studies have identified different specialized trophoblast populations including different subtypes of TGCs in mice. Also, specific progenitor populations, from which these specialized trophoblast populations are derived, have also been identified. However, proper importance of these trophoblast populations in relation to human trophoblast development is hard to fathom due to significantly different placental ultrastructure, differential gestational time period and differences in the actual process of placental development. Nevertheless, similarities between invasive TGCs and human extravillous CTBs, the common process of endovascular remodeling, trophoblast syncytialization, nutrient exchange between mother and fetus, and in endocrine function and immuno-modulation during rodent and human placentation provide solid platforms to ask specific questions. For example;

Several recent studies have identified new factors (like TEAD4) and signaling mechanisms (like Hippo signaling pathway) in TE-specification. However, their relevance in postimplantation trophoblast development needs to be addressed. Also, other transcription factors (CDX2, GATA3, and TCFAP2C) are implicated in both preimplantation TE-development as well as postimplantation maintenance of trophoblast progenitors. However, the precise functions of these factors or their target genes at distinct stages of trophoblast development are yet to be identified.

Multiple signaling pathways are implicated in TSC maintenance, trophoblast differentiation, invasion and endovascularization (Knofler 2010, Simmons and Cross 2005, Soares, et al. 2012). However, how these signaling pathways alter transcriptional mechanisms to establish cell type-specific gene expression programs are poorly understood.

Most of the genetic studies related to transcriptional mechanisms and trophoblast development have been performed in mouse models. However, given the variation of trophoblast cells in different species, essentiality of those mechanisms might vary from species to species. Thus, it is important to distinguish common versus unique transcriptional mechanisms of trophoblast development among multiple species. For example; a subset of chromatin remodeling/organizer proteins are critical for trophoblast development in mice. Yet, it is still not known whether these proteins are required for trophoblast development in humans or associated with pregnancy complications such as first trimester miscarriages, preeclampsia, or intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR). Studies using human trophoblast tissues from abnormal pregnancies will help answer these questions.

Several of the pregnancy-associated complications could be induced by environmental factors. However, how does a specific environmental factor modulate transcriptional mechanisms in trophoblast cells remains poorly understood.

Future studies in these contexts utilizing recent technologies like single-cell transcriptome analyses, genome-wide identification of transcription factor targets, as well gene editing tools will help to address these fundamental mechanistic questions and to better understand physiological processes for successful reproduction.

Figure 4. Role of chromatin remodeling/organizer proteins in trophoblast development.

During trophoblast specification BRG1 and BAFs (BAF47 and BAF155) negatively regulate Oct4 and Nanog expression to promote trophoblast development. Alternatively, BRG1 can positively regulate the expression of Cdx2, Eomes, and Elf5 to promote trophoblast self-renewal. The chromatin organizer SATB1/2 can also facilitate self-renewal by positively regulating Eomes expression in trophoblasts. During trophoblast differentiation the chromatin remodeling factor BPTF is necessary for transcriptional activation of Mash2 and Hand1. All three groups of proteins have established roles in inducing open and closed chromatin at target genes.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by NIH grants GM095347 to J.G.K. and HD062546, HL104322, and HL106311 to S.P.

Abbreviations

- ICM

inner cell mass

- TE

trophectoderm

- TSC

trophoblast stem cell

- EPC

ectoplacental cone

- ExE

extraembryonic ectoderm

- CTB

cytotrophoblast

- STB

syncytiotrophoblast

- TGC

trophoblast giant cell

- IUGR

intrauterine growth retardation

- CDX2

Caudal type homeobox 2

- TCFAP2C

transcription factor AP-2γ

- TEAD4

TEA domain family member 4

- GATA3

GATA binding protein 3

- GATA2

GATA binding protein 2

- EOMES

eomesodermin

- ELF5

E74-like factor

- ETS2

E twenty-six-domain transcription factor 2

- ERF

Ets2 repressor factor

- PRDM1

PR domain containing 1

- KLF5

Kruppel-like factor 5

- HIF

hypoxia inducible factor

- SOX2

SRY-box 2

- HAND1

heart and neural crest derivatives expressed transcript 1

- AP1

activator protein 1

- PTM

post-translational modifications

- GCM1

glial cell missing 1

- CITED1

Cbp/p300-interacting transactivator, with Glu/Asp-rich carboxy-terminal domain, 1

- CITED2

Cbp/p300-interacting transactivator, with Glu/Asp-rich carboxy-terminal domain, 2

- TLE3

transducin-like enhancer of split 3

- H3R26me

histone H3 arginine 26

- ESET

ERG-associated protein with SET domain

- H3K9me

Histone H3 lysine 9

- H3K27me

histone H3 lysine 27

- OVOL2

ovo-like 2

- DLX3

distal-less homeobox 3

- EED

embryonic ectoderm development

- KDM6B

lysine-specific demethylase 6B

- SUV39H1

variegation 3-9 homolog 1

- POU5f1

POU class 5 homeobox 1

- EZH2

enhancer of zeste homolog 2

- PRC2

polycomb repressor 2 complex

- H3K

histone H3 lysine

- BRG1

Brahma related gene 1

- BAF

BRG1-associated factor

- BPTF

bromodomain plant homeodomain transcription factor

- SATB1

SATB homeobox 1

- SATB2

SATB homeobox 2

- CARM1

coactivator-associated arginine methyltransferase 1

- HDAC

histone deacetylase

- DNMT

DNA methyltransferase

Footnotes

Declaration of interest: Authors have no conflict of interest to disclose.

References

- Adachi K, Nikaido I, Ohta H, Ohtsuka S, Ura H, Kadota M, Wakayama T, Ueda HR, Niwa H. Context-dependent wiring of Sox2 regulatory networks for self-renewal of embryonic and trophoblast stem cells. Mol Cell. 2013;52:380–392. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2013.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adelman DM, Gertsenstein M, Nagy A, Simon MC, Maltepe E. Placental cell fates are regulated in vivo by HIF-mediated hypoxia responses. Genes Dev. 2000;14:3191–3203. doi: 10.1101/gad.853700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alder O, Lavial F, Helness A, Brookes E, Pinho S, Chandrashekran A, Arnaud P, Pombo A, O'Neill L, Azuara V. Ring1B and Suv39h1 delineate distinct chromatin states at bivalent genes during early mouse lineage commitment. Development. 2010;137:2483–2492. doi: 10.1242/dev.048363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anson-Cartwright L, Dawson K, Holmyard D, Fisher SJ, Lazzarini RA, Cross JC. The glial cells missing-1 protein is essential for branching morphogenesis in the chorioallantoic placenta. Nat Genet. 2000;25:311–314. doi: 10.1038/77076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arima T, Hata K, Tanaka S, Kusumi M, Li E, Kato K, Shiota K, Sasaki H, Wake N. Loss of the maternal imprint in Dnmt3Lmat-/- mice leads to a differentiation defect in the extraembryonic tissue. Dev Biol. 2006;297:361–373. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2006.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asanoma K, Kubota K, Chakraborty D, Renaud SJ, Wake N, Fukushima K, Soares MJ, Rumi MA. SATB homeobox proteins regulate trophoblast stem cell renewal and differentiation. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:2257–2268. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.287128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asanoma K, Rumi MA, Kent LN, Chakraborty D, Renaud SJ, Wake N, Lee DS, Kubota K, Soares MJ. FGF4-dependent stem cells derived from rat blastocysts differentiate along the trophoblast lineage. Dev Biol. 2011;351:110–119. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2010.12.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Auman HJ, Nottoli T, Lakiza O, Winger QS, Donaldson S, Williams T. Transcription factor AP-2gamma is essential in the extra-embryonic lineages for early postimplantation development. Development. 2002;129:2733–2747. doi: 10.1242/dev.129.11.2733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barak Y, Nelson MC, Ong ES, Jones YZ, Ruiz-Lozano P, Chien KR, Koder A, Evans RM. PPAR gamma is required for placental, cardiac, and adipose tissue development. Mol Cell. 1999;4:585–595. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80209-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourc'his D, Xu GL, Lin CS, Bollman B, Bestor TH. Dnmt3L and the establishment of maternal genomic imprints. Science. 2001;294:2536–2539. doi: 10.1126/science.1065848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bultman S, Gebuhr T, Yee D, La Mantia C, Nicholson J, Gilliam A, Randazzo F, Metzger D, Chambon P, Crabtree G, Magnuson T. A Brg1 null mutation in the mouse reveals functional differences among mammalian SWI/SNF complexes. Mol Cell. 2000;6:1287–1295. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)00127-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burton A, Muller J, Tu S, Padilla-Longoria P, Guccione E, Torres-Padilla ME. Single-cell profiling of epigenetic modifiers identifies PRDM14 as an inducer of cell fate in the mammalian embryo. Cell Rep. 2013;5:687–701. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2013.09.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carey TS, Choi I, Wilson CA, Floer M, Knott JG. Transcriptional reprogramming and chromatin remodeling accompanies oct4 and nanog silencing in mouse trophoblast lineage. Stem Cells Dev. 2014;23:219–229. doi: 10.1089/scd.2013.0328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter AM. Animal models of human placentation--a review. Placenta. 2007;28(Suppl A):S41–47. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2006.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapman V, Forrester L, Sanford J, Hastie N, Rossant J. Cell lineage-specific undermethylation of mouse repetitive DNA. Nature. 1984;307:284–286. doi: 10.1038/307284a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng YH, Handwerger S. A placenta-specific enhancer of the human syncytin gene. Biol Reprod. 2005;73:500–509. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.105.039941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi I, Carey TS, Wilson CA, Knott JG. Transcription factor AP-2gamma is a core regulator of tight junction biogenesis and cavity formation during mouse early embryogenesis. Development. 2012 doi: 10.1242/dev.086645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chuong EB, Rumi MA, Soares MJ, Baker JC. Endogenous retroviruses function as species-specific enhancer elements in the placenta. Nat Genet. 2013;45:325–329. doi: 10.1038/ng.2553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cockburn K, Biechele S, Garner J, Rossant J. The Hippo pathway member Nf2 is required for inner cell mass specification. Curr Biol. 2013;23:1195–1201. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2013.05.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cockburn K, Rossant J. Making the blastocyst: lessons from the mouse. J Clin Invest. 2010;120:995–1003. doi: 10.1172/JCI41229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cowden Dahl KD, Fryer BH, Mack FA, Compernolle V, Maltepe E, Adelman DM, Carmeliet P, Simon MC. Hypoxia-inducible factors 1alpha and 2alpha regulate trophoblast differentiation. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25:10479–10491. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.23.10479-10491.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cross JC, Nakano H, Natale DR, Simmons DG, Watson ED. Branching morphogenesis during development of placental villi. Differentiation. 2006;74:393–401. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-0436.2006.00103.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dietrich JE, Hiiragi T. Stochastic patterning in the mouse pre-implantation embryo. Development. 2007;134:4219–4231. doi: 10.1242/dev.003798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donnison M, Beaton A, Davey HW, Broadhurst R, L'Huillier P, Pfeffer PL. Loss of the extraembryonic ectoderm in Elf5 mutants leads to defects in embryonic patterning. Development. 2005;132:2299–2308. doi: 10.1242/dev.01819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dupressoir A, Vernochet C, Bawa O, Harper F, Pierron G, Opolon P, Heidmann T. Syncytin-A knockout mice demonstrate the critical role in placentation of a fusogenic, endogenous retrovirus-derived, envelope gene. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:12127–12132. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0902925106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dupressoir A, Vernochet C, Harper F, Guegan J, Dessen P, Pierron G, Heidmann T. A pair of co-opted retroviral envelope syncytin genes is required for formation of the two-layered murine placental syncytiotrophoblast. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:E1164–1173. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1112304108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frendo JL, Olivier D, Cheynet V, Blond JL, Bouton O, Vidaud M, Rabreau M, Evain-Brion D, Mallet F. Direct involvement of HERV-W Env glycoprotein in human trophoblast cell fusion and differentiation. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23:3566–3574. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.10.3566-3574.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fryer BH, Simon MC. Hypoxia, HIF and the placenta. Cell Cycle. 2006;5:495–498. doi: 10.4161/cc.5.5.2497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gasperowicz M, Surmann-Schmitt C, Hamada Y, Otto F, Cross JC. The transcriptional co-repressor TLE3 regulates development of trophoblast giant cells lining maternal blood spaces in the mouse placenta. Dev Biol. 2013;382:1–14. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2013.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Genbacev O, Donne M, Kapidzic M, Gormley M, Lamb J, Gilmore J, Larocque N, Goldfien G, Zdravkovic T, McMaster MT, Fisher SJ. Establishment of human trophoblast progenitor cell lines from the chorion. Stem Cells. 2011;29:1427–1436. doi: 10.1002/stem.686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Genbacev O, Zhou Y, Ludlow JW, Fisher SJ. Regulation of human placental development by oxygen tension. Science. 1997;277:1669–1672. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5332.1669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- George KM, Leonard MW, Roth ME, Lieuw KH, Kioussis D, Grosveld F, Engel JD. Embryonic expression and cloning of the murine GATA-3 gene. Development. 1994;120:2673–2686. doi: 10.1242/dev.120.9.2673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Georgiades P, Rossant J. Ets2 is necessary in trophoblast for normal embryonic anteroposterior axis development. Development. 2006;133:1059–1068. doi: 10.1242/dev.02277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goller T, Vauti F, Ramasamy S, Arnold HH. Transcriptional regulator BPTF/FAC1 is essential for trophoblast differentiation during early mouse development. Mol Cell Biol. 2008;28:6819–6827. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01058-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guidi CJ, Sands AT, Zambrowicz BP, Turner TK, Demers DA, Webster W, Smith TW, Imbalzano AN, Jones SN. Disruption of Ini1 leads to peri-implantation lethality and tumorigenesis in mice. Mol Cell Biol. 2001;21:3598–3603. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.10.3598-3603.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta A, Guerin-Peyrou TG, Sharma GG, Park C, Agarwal M, Ganju RK, Pandita S, Choi K, Sukumar S, Pandita RK, Ludwig T, Pandita TK. The mammalian ortholog of Drosophila MOF that acetylates histone H4 lysine 16 is essential for embryogenesis and oncogenesis. Mol Cell Biol. 2008;28:397–409. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01045-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haig D. Retroviruses and the placenta. Curr Biol. 2012;22:R609–613. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2012.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haig D. Genomic vagabonds: endogenous retroviruses and placental evolution. Bioessays. 2013;35:845–846. doi: 10.1002/bies.201300099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hata K, Okano M, Lei H, Li E. Dnmt3L cooperates with the Dnmt3 family of de novo DNA methyltransferases to establish maternal imprints in mice. Development. 2002;129:1983–1993. doi: 10.1242/dev.129.8.1983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hemberger M, Udayashankar R, Tesar P, Moore H, Burton GJ. ELF5-enforced transcriptional networks define an epigenetically regulated trophoblast stem cell compartment in the human placenta. Hum Mol Genet. 2010;19:2456–2467. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddq128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirate Y, Hirahara S, Inoue K, Suzuki A, Alarcon VB, Akimoto K, Hirai T, Hara T, Adachi M, Chida K, Ohno S, Marikawa Y, Nakao K, Shimono A, Sasaki H. Polarity-dependent distribution of angiomotin localizes Hippo signaling in preimplantation embryos. Curr Biol. 2013;23:1181–1194. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2013.05.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Home P, Ray S, Dutta D, Bronshteyn I, Larson M, Paul S. GATA3 is selectively expressed in the trophectoderm of peri-implantation embryo and directly regulates Cdx2 gene expression. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:28729–28737. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.016840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Home P, Saha B, Ray S, Dutta D, Gunewardena S, Yoo B, Pal A, Vivian JL, Larson M, Petroff M, Gallagher PG, Schulz VP, White KL, Golos TG, Behr B, Paul S. Altered subcellular localization of transcription factor TEAD4 regulates first mammalian cell lineage commitment. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:7362–7367. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1201595109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houghton FD, Thompson JG, Kennedy CJ, Leese HJ. Oxygen consumption and energy metabolism of the early mouse embryo. Mol Reprod Dev. 1996;44:476–485. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-2795(199608)44:4<476::AID-MRD7>3.0.CO;2-I. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu D, Cross JC. Development and function of trophoblast giant cells in the rodent placenta. Int J Dev Biol. 2010;54:341–354. doi: 10.1387/ijdb.082768dh. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes M, Dobric N, Scott IC, Su L, Starovic M, St-Pierre B, Egan SE, Kingdom JC, Cross JC. The Hand1, Stra13 and Gcm1 transcription factors override FGF signaling to promote terminal differentiation of trophoblast stem cells. Dev Biol. 2004;271:26–37. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2004.03.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson MH, Ziomek CA. Induction of polarity in mouse 8-cell blastomeres: specificity, geometry, and stability. J Cell Biol. 1981;91:303–308. doi: 10.1083/jcb.91.1.303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaneko KJ, DePamphilis ML. TEAD4 establishes the energy homeostasis essential for blastocoel formation. Development. 2013;140:3680–3690. doi: 10.1242/dev.093799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kent LN, Rumi MA, Kubota K, Lee DS, Soares MJ. FOSL1 is integral to establishing the maternal-fetal interface. Mol Cell Biol. 2011;31:4801–4813. doi: 10.1128/MCB.05780-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keramari M, Razavi J, Ingman KA, Patsch C, Edenhofer F, Ward MC, Kimber SJ. Sox2 is essential for formation of trophectoderm in the preimplantation embryo. PLoS One. 2010;5:e13952. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0013952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kidder BL, Palmer S. Examination of transcriptional networks reveals an important role for TCFAP2C, SMARCA4, and EOMES in trophoblast stem cell maintenance. Genome Res. 2010;20:458–472. doi: 10.1101/gr.101469.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kidder BL, Palmer S, Knott JG. SWI/SNF-Brg1 regulates self-renewal and occupies core pluripotency-related genes in embryonic stem cells. Stem Cells. 2009;27:317–328. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2008-0710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim JK, Huh SO, Choi H, Lee KS, Shin D, Lee C, Nam JS, Kim H, Chung H, Lee HW, Park SD, Seong RH. Srg3, a mouse homolog of yeast SWI3, is essential for early embryogenesis and involved in brain development. Mol Cell Biol. 2001;21:7787–7795. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.22.7787-7795.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knofler M. Critical growth factors and signalling pathways controlling human trophoblast invasion. Int J Dev Biol. 2010;54:269–280. doi: 10.1387/ijdb.082769mk. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]