Abstract

Acculturation plays a critical role in the adjustment of Asian Americans, as a large proportion of them are immigrants in the U.S. However, little is known about how acculturation influences Asian American adolescents’ academic trajectories over time. Using a longitudinal sample of 444 Chinese American families (54% female children), the current study explored the effect of mothers’, fathers’, and adolescents’ individual acculturation profiles and parent-child acculturation dissonance on adolescents’ academic trajectories from 8th to 12th grade. Academic performance was measured by Grade Point Average (GPA), and by standardized test scores in English Language Arts (ELA) and Math every year. Latent growth modeling analyses showed that adolescents with a Chinese-oriented father showed faster decline in GPA, and Chinese-oriented adolescents had lower initial ELA scores. Adolescents whose parents had American-oriented acculturation profiles tended to have lower initial Math scores. These results suggest that Chinese and American profiles may be disadvantageous for certain aspects of academic performance, and bicultural adolescents and/or adolescents with bicultural parents are best positioned to achieve across multiple domains. In terms of the role of parent-child acculturation dissonance on academic trajectories, the current study highlighted the importance of distinguishing among different types of dissonance. Adolescents who were more Chinese-oriented than their parents tended to have the lowest initial ELA scores, and adolescents experiencing more normative acculturation dissonance (i.e., who were more American-oriented than their parents) had the highest initial ELA scores. No effects of parent-child acculturation dissonance were observed for GPAs or standardized Math scores. Altogether, the current findings add nuances to the current understanding of acculturation and adolescent adjustment.

Keywords: Parent-Child Acculturation, Academic Trajectory, Adolescence, Chinese American

Introduction

Asian American children are commonly perceived as academic overachievers. Compared to their peers, Asian American children tend to get better grades and obtain higher degrees (Crissey, 2007; Fuligni, 1997; Kao, 1995 ; Rosenthal & Feldman, 1991; Rumbaut, 1994). Many studies attempt to explain the relative academic success of Asian American children by examining ethnic-specific factors, such as sense of family obligation (Fuligni, Tseng, & Lam, 1999), parenting techniques unique to Asian Americans (Chao, 2001), and socioeconomic advantages (Jeong & Acock, 2014). However, only 52% of Asian Americans have a bachelor’s degree or higher (U.S. Census, 2010), which shows salient within-group variation in their academic outcomes. To date, studies that have investigated this within-group variation have relied on generational status or language proficiency as a predictor (Eng et al. 2008; Kao & Tienda, 1995; Glick & White, 2003); their results are therefore limited in terms of utility. The current study examines a more multi-faceted indicator, parent-child acculturation, in an attempt to determine whether it may be an important predictor of variation in Asian American children’s academic trajectories and outcomes.

As there is a higher proportion of immigrants among Asian Americans than among any other racial group in the U.S. (Grieco, 2009), acculturation plays an important role in the overall adjustment of this group. Using proxy measures of acculturation, such as generational status, studies have found that Asian American children of a later generation generally perform worse in school than do first and second generation children (Chao, 2001; Fuligni, 1997; Kao & Tienda, 1995). However, it is important to go beyond proxy measures like generational status, because they are not able to capture individual differences in levels of acculturation in language, attitudes and values (Yoon, et al., 2011). It is also important to take into account the family context of acculturation, as parent-child acculturation discrepancies have been shown to be a risk factor for child maladjustment (Costigan & Dokis, 2006; Kim, Chen, Li, Huang, & Moon, 2009). The current study adopted a person-centered approach to examine how the individual acculturation profiles of adolescents, fathers and mothers, as well as parent-child joint acculturation profiles, influence adolescents’ academic trajectories from early to middle adolescence in Chinese American families. Because family socioeconomic status is likely to contribute to both individual acculturation and adolescent achievement trajectories (Suárez-Orozco et al., 2010), it was included as a covariate in the current study.

Defining and Measuring Acculturation Using a Person-Centered Approach

Acculturation refers to two independent, simultaneous processes that take place in multiple dimensions when individuals from a different cultural background come into contact with the mainstream society in their host country: adapting to the language, values and behaviors of the mainstream culture while maintaining the language, values and behaviors of the heritage culture (Berry, 1997). Even though acculturation has been recognized as a bilinear, multi-dimensional construct, empirical studies have too often failed to reflect this complexity by focusing on a single aspect of acculturation (e.g., cultural behaviors; Farver, Bhadha, & Narang, 2002) in their design. Using multiple indicators of acculturation, a recent study (Weaver & Kim, 2008) identified three acculturation profiles: bicultural, more American, or more Chinese in cultural orientation. Those with a more American profile scored highest on American orientation and English language proficiency, and lowest on Chinese orientation, Chinese language proficiency, and family obligation. The opposite pattern was observed for those with a more Chinese profile. Those with a bicultural profile generally scored high on both American and Chinese orientations. The present study functions as a follow-up, and uses the same three acculturation profiles previously identified (Weaver & Kim, 2008) to examine the role of acculturation in the academic trajectories of Chinese American children.

Academic Trajectories in Asian American Adolescents

Academic performance in Asian American children has generally been studied by focusing on a single time point or by noting changes occurring between two time points. Studies that have examined academic performance over time found a faster decrease in reading and mathematics performance among Asian American children from kindergarten to the third grade, compared to their peers (Han, 2008). However, little is known about changes in academic performance among older Asian American children. It is critical to examine academic trajectories among adolescents, in particular, because they are at risk for experiencing a decline in both academic motivation and performance (Eccles et al., 1993). Studies have demonstrated a downward curvature of Grade Point Average from junior high to high school (Gutman, Sameroff, & Cole, 2003). A recent study of immigrant adolescents, including a small group of Chinese immigrants, showed that such declines were also likely to occur in this group (Suárez-Orozco et al., 2010). However, that particular study had a small sample size of Chinese American adolescents and was limited in that it used GPA as the only indicator.

When examining academic achievement among Asian American adolescents, it is important to distinguish between different aspects of performance, such as Grade Point Average and standardized test scores (Fuligni, 1997; Tran & Birman, 2010). Although Asian American adolescents usually score higher than their peers in English and mathematics classes (Witkow & Fuligni, 2005), they tend to display mixed patterns on standardized tests, often scoring similarly or higher in mathematics (Yan & Lin, 2005), and similarly or lower in reading, than their white counterparts (Aldous, 2006; Kao & Tienda, 1995). It is possible that Grade Point Average may be tied to a student’s behaviors and values (e.g., school effort and sense of family obligation), whereas standardized test scores may be more closely tied to a student’s ability in a specific subject. From this perspective, Grade Point Average and standardized test scores may show different patterns, not only in their mean levels, but also in changes over time. In order to capture these potential differences, the current study examines the trajectories of Grade Point Average and standardized test scores in English Language Arts and Math among Asian American children from early to middle adolescence. This study explores how initial levels and changes over time are each influenced both by individual acculturation and by parent-child joint acculturation.

Acculturation and Academic Trajectories

Acculturation studies have identified academic benefits from involvement with both Asian and American cultures. On the one hand, adolescents who highly endorse the Asian culture tend to be more motivated and engaged in school, which may be beneficial for their GPA. For example, Chinese American adolescents with a stronger identification with their ethnic group had more positive academic attitudes, placing a higher value on the utility of education and school respect (Fuligni, Witkow, & Garcia, 2005; Kiang, Supple, Stein, Gonzalez, 2012). Asian American adolescents who indicated greater endorsement of Asian cultural values, such as family obligation, were also shown to have stronger academic motivation (Fuligni, Tseng, & Lam, 1999). On the other hand, adolescents who are more involved with the mainstream culture are generally more proficient in English, which is related to higher standardized test scores in English (Kao & Tienda, 1995). Thus, while bicultural adolescents are likely to benefit from involvement with both cultures and to exhibit higher levels of achievement (Farver et al., 2002), adolescents who are Chinese- or American-oriented may experience difficulties as a result of losing contact with the culture with which they identify less strongly.

A limitation in the literature on adolescents’ acculturation and academic adjustment is that little is known about the long-term effects of acculturation. Prior work has highlighted the utility of examining acculturation in early adolescence: during that period of time, it has marked effects on students’ later socioemotional wellbeing and achievement (Kim, Chen, Wang, Shen, & Orozco-Lapray, 2013). It is also important to examine the extent to which early acculturation influences achievement trajectories, as academic performance is often subject to substantial changes (typically declines) during adolescence (Eccles et al., 1993; Gutman, Sameroff, & Cole, 2003). Using proximal measures of acculturation, such as language proficiency, recent work has shown that adolescents’ acculturation is indeed linked to academic trajectories over time. For example, in a sample of immigrant youth, including Chinese immigrant adolescents, Suárez-Orozco et al. (2010) found that those who were more proficient in English were not only more likely than their peers to have high initial GPAs, but also less likely to experience declines in GPA over the course of five years. The current study extends this work in two ways. First, we used acculturation profiles that were based on a comprehensive set of acculturation indicators. Second, we examined the links between acculturation profiles and academic trajectories for both GPA and standardized test scores.

In addition to examining adolescents’ acculturation, the current study also attempts to explore the role that parents’ acculturation plays in the trajectories of their children’s academic performance. Informed by the literature on biculturalism, we propose that bicultural parents are most likely to have well-adjusted children with high initial achievement and less severe declines over time, because these parents benefit from their endorsement of both cultures, Chinese and American. For example, traditional Chinese culture places high value and great emphasis on education, especially on mastery of subjects like mathematics (Sy & Schulenberg, 2005), and features of the Chinese language also afford advantages for mathematics learning (Ng & Rao, 2010). On the other hand, parents who have greater involvement with the American culture may be more familiar with the educational system and more efficient in supporting their children’s education (Jeonga & Acock , 2014; Turney & Kao, 2009; Costigan & Koryzma, 2011). Thus, bicultural parents may be especially motivated and competent in supporting their children’s education in multiple domains, whereas Chinese-oriented or American-oriented parents may lack the ability to promote education in certain subjects. To get a more integrated view of the ways in which Chinese American adolescents’ academic trajectories are influenced by the phenomenon of acculturation, the current study explores how adolescents’ academic trajectories are influenced by their own acculturation profiles, by the acculturation profiles of their fathers and mothers, and by parent-child acculturation dissonance.

In immigrant families, parents and children often acculturate at different pace. Previous studies have documented lower academic achievement among adolescents experiencing parent-child acculturation discrepancy, possibly due to disrupted family functioning (Kim, Chen, Wang, Shen, & Orozco-Lapray, 2013). However, there is also evidence suggesting the importance of distinguishing among different types of acculturation dissonance (Telzer, 2010). While dissonance in which adolescents are more oriented towards the mainstream culture than their parents may help both adolescents and their parents to better meet the demands of the larger society, dissonance in which adolescents are more aligned with the heritage culture than their parents does occur, and is often considered non-normative and thus more disruptive for adolescent adjustment (Lau et al., 2005). Informed by this work, the current study identifies three types of parent-child acculturation profiles – parent-child consonance, adolescent-more-American-oriented-than-parent (normative dissonance), adolescent-more-Chinese-oriented-than-parent (non-normative dissonance) – and explores how each of them influences achievement. Given previous evidence, we propose that adolescents who are more Chinese-oriented than their parents tend to have lower academic performance and experience greater declines over time.

Present Study

The present study is part of a longitudinal study on Chinese Americans, in which data on academic performance were collected every year from early to late adolescence. In examining the role of acculturation in early adolescence for academic trajectories in later adolescence, this study had three main objectives. First, we used GPA and standardized test scores in English Language Arts and Math to examine adolescents’ academic trajectories as individual growth models. Second, we examined each individual’s acculturation profile (mother’s, father’s, and adolescent’s) to see how it might influence adolescents’ initial achievement and/or changes in achievement over time. Informed by research on the benefits of biculturalism, we expected that adolescents with more American or more Chinese profiles, and those with more American- or Chinese-oriented parents, may experience difficulties in different aspects of academic performance. Third, we explored the role of parent-child acculturation dissonance on academic trajectories over time. We expected to observe a particular disadvantage among adolescents experiencing non-normative acculturation dissonance (i.e., among adolescents who are more Chinese-oriented than their parents).

Methods

Participants

Data for the current study were drawn from a longitudinal study on 444 Chinese American families in Northern California school districts. Among these families, 408 mothers and 382 fathers participated in the current study. Slightly over half of the adolescent sample is female (n = 239, 54%). The age of the adolescents ranged from 12 to 15 (M = 13, SD = 0.73). The majority (89%) of the participating families were two-parent families. Median family income was in the range of $30,001 to $45,000. Parents reported having, on average, some high school education. The majority of parents are foreign-born (83% of fathers and 88% of mothers), and the majority of adolescents are U.S.-born (75%). The majority speaks Cantonese; less than 10% of the families speak Mandarin as their home language.

Procedure

Participants were initially recruited from seven middle schools in major metropolitan areas of Northern California. With the aid of school administrators, Chinese American students were identified, and all eligible families were sent a letter describing the research project. Families that returned forms indicating parent consent and adolescent assent received a packet of questionnaires for the mother, father, and target adolescent in the household. Target adolescents who returned family questionnaires were compensated a nominal amount of money for their participation. About half (47%) of the families that were initially recruited followed through with consent, and 76% of these submitted completed questionnaires. When all the adolescents participating in the study had finished high school, the research team obtained their transcripts from the school district.

Questionnaires were prepared in English and Chinese. The questionnaires were first translated to Chinese and then back-translated to English. Any inconsistencies with the original English version scale were resolved by bilingual/bicultural research assistants with careful consideration of culturally appropriate meanings of items. Most parents (71% of fathers and 71% of mothers) used the Chinese language version of the questionnaire, and the majority (85%) of adolescents used the English version.

Attrition analyses comparing adolescents with complete information on academic performance from grade 8 to 12 (N = 396) and those with missing data in at least one wave (N = 48) revealed no significant differences between groups on key demographic variables (i.e., parental education, family income, parental marital status, parental age) with one exception: boys were more likely to have missing data than girls (χ2 (1) = 4.39, p < .05). Accordingly, adolescent gender is included as a covariate for all analyses.

Measures

Students’ academic achievement

Students’ Grade Point Averages (GPAs) from 8th to 12th grade, as well as standardized test scores from 8th to 11th grade, were obtained from school records. Students were not administered standardized tests in grade 12. GPA was measured on a scale ranging from 0 to 4 in all participating schools. Standardized test scores were based on a five point scale, ranging from 1 (far below basic) to 5 (advanced). The sample mean ranged from 3.12 (SD = .65) to 3.41 (SD = .59) for GPA, from 3.59 (SD = 1.02) to 3.95 (SD = .96) for standardized test scores in ELA, and from 3.28 (SD = 1.08) to 3.92 (SD = .85) for standardized test scores in Math. Correlations among all the achievement scores across waves were from moderate to high (r = .34 to .81).

Acculturation Profiles

Acculturation profiles for mothers, fathers, and adolescents in the current study were identified from another study (Weaver & Kim, 2008) using latent profile analysis. The following measures, assessed at the initial data collection wave, were specified as indicators in the latent profile analysis: the Vancouver Index of Acculturation’s (VIA; Ryder, Alden, & Paulhus, 2000) American and Chinese orientation scales, Chinese and English language proficiency variables, and the family obligations scale (Fuligni et al., 1999). The VIA uses a five-point scale, and includes 10 items about participants’ American orientation (i.e., cultural values and behaviors) and 10 items about their Chinese orientation. An example item is, “I often follow American cultural traditions.” The Chinese orientation items are the same as the American orientation items, except that the word “American” is changed to “Chinese.” The internal consistency for each subscale was high across waves and informants (α = .81 to .84). Chinese and English language proficiency were each measured using two items (i.e., speak/understand and read/write each language) on a five-point scale. Family obligations were measured with 12 items about the importance of being respectful and providing support to the family (e.g., “have your parents live with you when you get older”) on a five-point scale. The internal consistency was high across informants (α = .81 to .89). Both the VIA scale and the family obligation scale have been reliably measured in multiple ethnic groups, including Chinese Americans, and were also found to be related with measures of self-construal and adjustment (Fuligni, Tseng, & Lam, 1999; Ryder, Alden, & Paulhus, 2000).

Results of the latent profile analyses classified each adolescent, mother, and father in the sample into one of three profiles: Bicultural, American, or Chinese. Among adolescents, the largest cultural orientation class was American (53%), followed by Bicultural (31%) and Chinese (16%). Among fathers, the largest cultural orientation class was Chinese (50%), followed by Bicultural (35%) and American (15%). Among mothers, the largest cultural orientation class was Bicultural (47%), followed by Chinese (40%) and American (13%).

Parent-Child Acculturation Consonance/Dissonance

We identified three types of parent-child joint acculturation types based on a combination of parents’ and adolescents’ acculturation profiles. This was done separately for father-adolescent and mother-adolescent dyads. In the first group, parents and adolescents had the same acculturation profile (i.e., were parent-child consonant). There were 35% father-adolescent dyads and 38% mother-adolescent dyads classified into this group. In the second group, adolescents had a more American-oriented acculturation profile than their parents (i.e., were parent-Chinese/adolescent-Bicultural/American, or parent-Bicultural/adolescent-American). Collectively, this group represented the normative dissonant group. There were 57% father-adolescent dyads and 55% mother-adolescent dyads classified into this group. In the last group, adolescents’ acculturation profiles were more Chinese oriented than their parents’ profiles (i.e., were parent-Bicultural/adolescent-Chinese, or parent-American/adolescent Chinese/Bicultural). Collectively, this group represented the non-normative dissonant group. There were 8% father-adolescent dyads and 8% mother-adolescent dyads classified into this group.

Covariates

At the initial data collection wave, adolescents reported their sex, and fathers and mothers reported family income before taxes and highest level of education attained. Family income was assessed using a 12-point scale, from (1) “below $15,000” to (12) “$165,001 or more.” Parents’ highest level of education was assessed using a 9-point scale, ranging from (1) “no formal schooling” to (9) “finished graduate degree (medical, law, Master’s degree, etc.).” For each family, the father’s and mother’s responses were averaged.

Results

Plan of Analyses

All the analyses were conducted in Mplus 7, which handles missing data with full-information maximum likelihood (FIML) estimation. Data analyses proceeded in three steps. First, to examine the growth trajectories of students’ academic performance, an unconditional growth model was fitted separately for Grade Point Average (GPA) and standardized test scores in English Language Arts (ELA) and Math. A linear model and a quadratic model were fitted separately, and Satorra-Bentler scaled Chi-Square tests (Satorra & Bentler, 2001) were used to determine which model fit the data better. The linear and/or quadratic slopes were allowed to regress on the intercept, as students’ initial academic achievement is likely to predict their future growth rate in achievement. The residual variances of quadratic slopes were fixed at zero for model convergence (Jung & Wickrama, 2008). In some instances, the residual variances of measures at different time points were allowed to co-vary in light of high correlations.

Second, to examine the effect of individual acculturation profiles on students’ academic trajectories, dummy variables indicating the profiles of the adolescent, father, and mother were tested as predictors of the intercepts and slopes of the growth models. Because there were three possible profile types (Bicultural, Chinese, American) for each family member, two dummy-coding schemes were used, with the Chinese profile and the Bicultural profile functioning as the reference group, respectively. Conditional growth models using these two coding schemes were estimated separately for the adolescent, father, and mother in each family, resulting in a total of six models. Parent education, family income, and adolescent sex were included as covariates.

Finally, to examine the effect of parent-child acculturation dissonance on students’ academic trajectories, we tested the extent to which the intercepts and slopes of the growth models were predicted by dummy variables indicating father-adolescent or mother-adolescent acculturation dissonance. Two dummy-coding schemes were created for these parent-child dissonance groups, with the parent-child consonant group and the adolescent-more-American group functioning as the reference groups, as appropriate. Three conditional growth models with the two coding schemes were estimated separately for father-adolescent and mother-adolescent joint profiles, resulting in a total of 12 models. All covariates (i.e., parent education, family income, and adolescent sex) were included in this set of analyses.

Individual Growth Models

Our first set of analyses explored academic trajectories for GPA and standardized test scores in English and Math. A linear growth model was compared with a non-linear model to determine the shape of the trajectories. For GPA, results showed a significant difference between the linear and the nonlinear model (χ2 (1) = 112.394, p < .001). Therefore, a non-linear model was adopted for students’ GPA growth. The residual variances of GPA for grades 9 and 10 were allowed to co-vary in light of the high correlation in GPA between these consecutive years. The model fit was good, χ2 (7) = 11.905, p = .104, CFI = .992, RMSEA = 0.040, SRMR = 0.047.

Similarly, for ELA, results showed a significant difference between the linear and the non-linear model (χ2 (1) = 52.685, p < .001). Therefore, a non-linear model was adopted for students’ ELA growth. The model fit was good, χ2 (3) = 19.438, p = .0002, CFI = .984, RMSEA = 0.111, SRMR = 0.031.

For Math, results showed no significant difference between the linear and the non-linear model (χ2 (1) = 1.440, p = .23). Therefore, a linear model was adopted for students’ growth in Math. The residual variances of the Math scores for grades 9 and 10, grades 10 and 11, and grades 9 and 11 were then allowed to co-vary to account for their high correlation at these grade levels. The model fit was good, χ2 (3) = 11.194, p = .011, CFI = .988, RMSEA = 0.079, SRMR = 0.025.

Acculturation Profiles as Predictors of Academic Growth

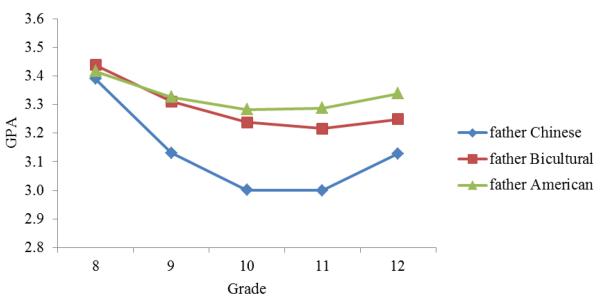

We next examined the effect of individual acculturation profiles on adolescents’ academic trajectories, controlling for demographic characteristics including parent education, family income, and adolescent sex. Analyses were conducted separately for adolescents’, fathers’, and mothers’ acculturation profiles and separately for GPA, ELA, and Math trajectories. Coefficient estimates and model fit indices are displayed in Table 2. Overall, Chinese profiles were associated with disadvantages in GPA and ELA trajectories, whereas American profiles were associated with poorer Math trajectories. Specifically, for GPA trajectories, adolescents with a Chinese-profile father were at a disadvantage. Compared to this group, adolescents with a Bicultural-profile father or an American-profile father had a significantly higher linear slope, as well as a significantly lower quadratic slope. In other words, adolescents with a Chinese-profile father experienced a faster decrease in GPA over time compared to their peers, even though their GPA increased slightly from grade 11 to 12 (see Figure 1).

Table 2.

Standardized Growth Model Coefficients for Adolescent, Father, and Mother Acculturation Profiles

| Profile Source |

Para- mete r |

Comparison Group |

GPA |

ELA |

Math |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R Chinese |

R Bicultural |

R Chinese |

R Bicultural |

R Chinese |

R Bicultural |

|||

| Teen | I | Bicultural | .11 | .40 *** | .05 | |||

| American | .13 | .01 | .50 *** | .07 | −.06 | −.11 | ||

| S | Bicultural | −.35 | −.42 | −.11 | ||||

| American | −.21 | .17 | −.58 | −.13 | −.29 | −.17 | ||

| Q | Bicultural | .12 | .23 | |||||

| American | −.02 | −.15 | .48 | .24 | ||||

|

| ||||||||

| Father | I | Bicultural | .04 | .04 | .16 | |||

| American | .02 | −.01 | −.01 | −.04 | −.16 | −.28 ** | ||

| S | Bicultural | .68 *** | .12 | .08 | ||||

| American | .63 *** | .12 | .06 | −.03 | −.02 | −.08 | ||

| Q | Bicultural | −.78 ** | −.39 | |||||

| American | −.63 ** | −.05 | −.34 | −.06 | ||||

|

| ||||||||

| Mother | I | Bicultural | −.09 | −.07 | −.07 | |||

| American | −.01 | .05 | −.02 | .03 | −.21 ** | −.16 | ||

| S | Bicultural | .11 | −.09 | −.03 | ||||

| American | .30 | .23 | .00 | .06 | −.04 | −.02 | ||

| Q | Bicultural | −.16 | .35 | |||||

| American | −.20 | −.09 | −.19 | −.42 | ||||

Note. N = 444. R = reference group, I = intercept, S = linear slope, Q = quadratic slope, GPA = Grade Point Average, ELA = English Language Arts. All the models showed a good fit to the data, CFI = .97 to .99, RMSEA = .04 to .08, SRMR = .03 to .06. The significance level of p < .01 was adopted due to multiple comparisons among acculturation profiles.

p < .01,

p < .001.

Figure 1.

Estimated effect of fathers’ acculturation profiles on trajectories of Grade Point Average (GPA)

For ELA trajectories, adolescents’ Chinese profiles showed some negative impacts. Compared to those with a Chinese profile, adolescents with a Bicultural profile or an American profile had significantly higher initial ELA scores.

For Math trajectories, both fathers’ and mothers’ American profiles showed some negative impacts. Adolescents with an American-profile father had significantly lower initial scores than those with a Bicultural-profile father. In addition, adolescents with an American-profile mother had significantly lower initial scores compared to those with a Chinese-profile mother.

Parent-Child Acculturation Dissonance as a Predictor of Academic Growth

Finally, we examined whether parent-child acculturation dissonance predicts adolescents’ academic trajectories, with all covariates included. Analyses were conducted separately for father-adolescent and mother-adolescent dyads and separately for each academic indicator. Model fit indices and coefficient estimates are displayed in Table 3. We observed significant effects of parent-child acculturation dissonance on ELA trajectories, but non-significant ones on GPA and Math trajectories. Specifically, adolescents whose acculturation profiles were more Chinese-oriented than their parents’ profiles generally showed the most problematic ELA trajectories: they had lower initial scores than adolescents who were more American-oriented than their parents, regardless of parent gender; they also had lower initial scores than the consonant group among mother-adolescent dyads. In contrast, adolescents who were more American-oriented than their parents showed higher initial ELA scores than the consonant group, regardless of parent gender.

Table 3.

Standardized Growth Model Coefficients for Father-Adolescent and Mother-Adolescent Joint Acculturation Profiles

| Profile Source |

Para- mete r |

Comparison Group | GPA |

ELA |

Math |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parent Teen Consonant |

Teen More American |

Parent Teen Consonant |

Teen More American |

Parent Teen Consonant |

Teen More American |

|||

| Father- Teen |

I | Teen More American | .09 | .19 ** | −.02 | |||

| Teen More Chinese | .02 | −.02 | −.14 | −.24 *** | .01 | .02 | ||

| S | Teen More American | −.53 | −.09 | .02 | ||||

| Teen More Chinese | .10 | .38 | .31 | .36 | .20 | .19 | ||

| Q | Teen More American | .49 | .03 | |||||

| Teen More Chinese | −.23 | −.49 | −.43 | −.45 | ||||

|

| ||||||||

| Mother -Teen |

I | Teen More American | .05 | .26 *** | .10 | |||

| Teen More Chinese | −.10 | −.12 | −.16 ** | −.30 *** | .04 | −.01 | ||

| S | Teen More American | −.16 | −.19 | −.02 | ||||

| Teen More Chinese | .05 | .14 | .43 | .53 | .21 | .22 | ||

| Q | Teen More American | −.01 | .41 | |||||

| Teen More Chinese | .05 | .06 | −.24 | −.46 | ||||

Note. N = 444. R = reference group, I = intercept, S = linear slope, Q = quadratic slope, GPA = Grade Point Average, ELA = English Language Arts. All the models showed a good fit to the data, CFI = .97 to .99, RMSEA = .04 to .08, SRMR = .03 to .06. The significance level of p < .01 was adopted due to multiple comparisons among acculturation profiles.

p < .01,

p < .001

Discussion

Acculturation plays a crucial role in Asian Americans’ adjustment, as about two thirds of this population are foreign-born (U.S. Census Bureau, 2007). However, little is known about the role acculturation plays in Asian American adolescents’ academic trajectories over time. Using a person-centered approach, the current study explored the effect of individual acculturation profiles (i.e., acculturation profiles of adolescents, fathers and mothers) and parent-child acculturation dissonance on Chinese American children’s academic trajectories throughout adolescence. Distinct patterns were observed for each aspect of academic performance. Specifically, Grade Point Average (GPA) decreased faster from early to middle adolescence among children whose fathers had a Chinese acculturation profile. In addition, the initial standardized test scores in English Language Arts (ELA) were lower among adolescents with a Chinese acculturation profile, and adolescents who were more Chinese-oriented than their parents tended to have the lowest ELA initial scores. Finally, the initial standardized test scores in Math tended to be lower among adolescents whose parents had an American profile.

The current study found that acculturation profiles differentially influence initial levels and also changes in levels of academic achievement over time, depending on the specific academic indicator being examined. Specifically, GPA trajectories were affected by acculturation mainly in terms of their change over time, whereas standardized test scores in English and Math were affected by acculturation mainly in terms of adolescents’ initial scores. This difference may be due to the fact that GPA and standardized test scores measure different aspects of academic performance. Standardized test scores measure ability in a specific academic subject, whereas GPA is usually a reflection of students’ school-related values and behaviors, which are more subject to change over the course of adolescence (Willingham, Pollack, & Lewis, 2002). Thus, acculturation profiles are more likely to influence changes in GPA than changes in standardized test scores. The current study highlights the importance of incorporating different indicators and using longitudinal data when examining Asian American adolescents’ academic performance.

In examining the role of adolescents’ acculturation, the current study showed that a Chinese-oriented profile was a disadvantage for standardized test scores in English. Perhaps Chinese-oriented adolescents are less involved with the mainstream culture, which typically equips individuals with English proficiency (Kao & Tienda, 1995). This finding is consistent with previous studies highlighting the achievement gap in English standardized test scores between first generation youth and those of a later generation (Kao & Tienda, 1995).

In addition to illuminating issues related to adolescents’ acculturation, the current study extends the existing literature by examining the effect of parents’ acculturation profiles on adolescents’ academic trajectories. Results demonstrate that having a father with a Chinese profile had a negative effect on adolescents’ GPA trajectories. This is consistent with prior work on acculturation and parenting, which indicates that a lack of involvement with the mainstream American culture may make it difficult for parents to be involved in the educational system (Jeonga & Acock, 2014; Turney & Kao, 2009); acculturation difficulties may also engender stress, hindering parents’ ability to support their children’s school work (Costigan & Koryzma, 2011; Kim, Shen, Huang, Wang, & Orozco-Lapray, in press). Interestingly, parental Chinese-oriented acculturation profiles had a negative impact on adolescents’ GPA trajectories only in the case of fathers. Given their traditional role as the breadwinner and head of the family (Roer-Strier, Strier, Este, Shimoni, & Clark, 2005), fathers with a Chinese profile may experience more adaptation stress compared to those with an American or Bicultural profile. This stress may compromise fathers’ ability to fulfill their parenting roles (Kim et al., in press), which may explain the faster decrease in GPAs observed among adolescents with Chinese-profile fathers.

Another major finding was that parents’ American-oriented acculturation profiles tended to be a drawback for adolescents’ standardized test scores in Math. Because Chinese is more efficient than English when it comes to representing and processing numbers (Geary, Bow-Thomas, Liu, & Siegler, 1996; Ng & Rao, 2010), parents with an American-oriented profile may be less effective in promoting Math performance in their children despite their greater familiarity with the educational system. Furthermore, the benefits of Chinese language may be able to offset the negative impact of Chinese-oriented fathers’ lack of involvement with the mainstream culture, because we did not observe disadvantaged Math trajectories among adolescents who had a Chinese-oriented father.

The results we obtained by examining adolescents’ and parents’ acculturation profiles together suggest that Bicultural profiles tended to benefit adolescents’ achievement across various academic indicators. The extent to which Chinese or American profiles were a disadvantage depended on the specific academic indicators under examination: a Chinese profile was a disadvantage for adolescents’ GPA trajectories and initial English abilities; in contrast, an American profile was disadvantageous for adolescents’ initial Math scores. As mentioned in the above discussion, lack of involvement with either culture entails loss of certain benefits (e.g., lack of involvement with American culture may relate to lack of English proficiency). Bicultural individuals are likely to benefit from their involvement in both cultures, and are thus best positioned for adaptation (Berry, Phinney, Sam, & Vedder, 2006; Nguyen & Benet-Martínez, 2013). These implications are consistent with findings from previous studies highlighting the academic advantages of bicultural or second generation children (Farver et al., 2002; Kao & Tienda, 1995).

In addition to exploring the effect of individual acculturation, the current study examined the effect of parent-child acculturation dissonance on adolescents’ academic trajectories. Dissonance in the parent-child joint acculturation profile has been theorized to compromise adolescents’ adjustment in immigrant families by increasing parent-child conflict (Telzer, 2010). However, the current study showed that parent-child dissonance was actually beneficial for adolescents’ standardized test scores in English when adolescents had a more American-oriented profile than their parents. Perhaps adolescents from these families have a greater awareness of the need to acculturate into the American culture, or perhaps their parents placed particular emphasis on these children learning English. Deleterious effects of acculturation dissonance on initial ELA scores manifested only among dyads in which adolescents were more Chinese-oriented than their parents. This finding is consistent with prior work (Lau et al., 2005; Telzer, 2010), which suggested that only those in the non-normative dissonance group (i.e., the group in which adolescents endorse the heritage culture to a greater degree than their parents) are likely to experience adaptation problems. These results highlight the importance of examining parent-child acculturation dissonance in more nuanced ways.

There are a few limitations of the current study. First, the participants were recruited from an area with a dense Chinese American population. It is not clear whether the current findings would hold for Chinese American families from other areas. Second, the data for acculturation were obtained using adolescents’ and their parents’ self-reports only. Third, acculturation was assessed only in the first wave of the study. Individual acculturation may change over the course of adolescence (Updegraff, Umaña-Taylor, McHale, Wheeler, & Perez-Brena, 2012), especially as adolescents become increasingly more engaged in peer groups and less involved in the family (Smetana, Campione-Barr, & Metzger, 2006). Future studies are needed to examine whether acculturation and adolescents’ academic performance reciprocally influence each other across time. Finally, the current study focused on the direct links between acculturation and achievement, but there may also be ways in which acculturation exerts an influence on achievement indirectly. Studies have shown that acculturation is associated with some critical components of adolescents’ academic success, such as adolescents’ academic attitudes (Fuligna, Witkow, & Garcia, 2005) and parents’ academic support (Turney & Kao, 2009). Given that the current findings establish direct links between acculturation and achievement, exploring potential mediators for this relationship is a warranted next step.

Conclusion

The existing literature has documented the impact of acculturation on Asian American adolescents’ academic achievement (Eng et al. 2008; Kao & Tienda, 1995), yet little is known about how acculturation influences their academic trajectories over time. The current study highlights the critical role played by family acculturation in early adolescence for Chinese American children’s academic trajectories throughout adolescence. Both individual and parent-child acculturation profiles influenced academic trajectories in various ways, by affecting adolescents’ initial standardized test scores in English and Math and also the change in adolescents’ GPA trajectories over time. For example, a Chinese acculturation profile tended to be disadvantageous for adolescents’ GPAs and standardized test scores in English, whereas an American profile tended to be disadvantageous for adolescents’ Math skills. Additionally, non-normative parent-child acculturation dissonance (i.e., a dynamic in which adolescents were more Chinese-oriented than their parents) was disadvantageous for adolescents’ initial English scores. Together, these findings provide a nuanced view of how various forms of acculturation influence academic achievement across adolescence. The findings also indicate that early adolescence is a critical intervention point, and they provide information that will help researchers to identify adolescents who may benefit from future intervention programs.

Table 1.

Correlations among Primary Study Variables

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | GPA08 | ||||||||||||||||

| 2. | GPA09 | .69 | |||||||||||||||

| 3. | GPA10 | .68 | .81 | ||||||||||||||

| 4. | GPA11 | .61 | .65 | .72 | |||||||||||||

| 5. | GPA12 | .53 | .60 | .66 | .69 | ||||||||||||

| 6. | ELA08 | .46 | .45 | .39 | .43 | .38 | |||||||||||

| 7. | ELA09 | .51 | .49 | .45 | .47 | .39 | .77 | ||||||||||

| 8. | ELA10 | .53 | .50 | .48 | .49 | .46 | .75 | .77 | |||||||||

| 9. | ELA11 | .52 | .47 | .48 | .48 | .45 | .72 | .77 | .81 | ||||||||

| 10. | Math08 | .45 | .42 | .36 | .36 | .34 | .48 | .46 | .48 | .50 | |||||||

| 11. | Math09 | .49 | .48 | .44 | .43 | .37 | .50 | .55 | .54 | .57 | .56 | ||||||

| 12. | Math10 | .44 | .46 | .46 | .41 | .39 | .47 | .47 | .52 | .56 | .58 | .72 | |||||

| 13. | Math11 | .44 | .37 | .39 | .44 | .42 | .46 | .48 | .52 | .58 | .58 | .70 | .70 | ||||

| 14. | P-Education | .20 | .23 | .22 | .17 | .17 | .20 | .25 | .28 | .22 | .09 | .11 | .09 | .11 | |||

| 15. | P-Income | .17 | .14 | .15 | .13 | .14 | .27 | .28 | .28 | .23 | .02 | .10 | .02 | .11 | .56 | ||

| 16. | A-Sex | .35 | .28 | .27 | .25 | .21 | .17 | .14 | .14 | .14 | .10 | .07 | .11 | .03 | .00 | − .06 | |

|

| |||||||||||||||||

| M | 3.41 | 3.16 | 3.11 | 3.12 | 3.17 | 3.59 | 3.95 | 3.89 | 3.89 | 3.92 | 3.68 | 3.58 | 3.28 | 5.88 | 3.79 | 0.54 | |

| SD | 0.59 | 0.71 | 0.71 | 0.65 | 0.56 | 1.02 | 0.96 | 0.97 | 1.05 | 0.85 | 1.01 | 1.03 | 1.08 | 1.64 | 2.48 | 0.50 | |

Note. N = 444. All coefficients with an absolute value of .10 or higher are significant at p < .05 (two-tailed).

P = Parent, A = Adolescent, GPA = Grade Point Average, ELA = English Language Arts; numbers 08 to 12 denote adolescent’s grade level.

Acknowledgments

Support for this research was provided through awards to Su Yeong Kim from (1) Eunice Kennedy Shriver NICHD 5R03HD051629-02 (2) Office of the Vice President for Research Grant/Special Research Grant from the University of Texas at Austin (3) Jacobs Foundation Young Investigator Grant (4) American Psychological Association Office of Ethnic Minority Affairs, Promoting Psychological Research and Training on Health Disparities Issues at Ethnic Minority Serving Institutions Grant (5) American Psychological Foundation/Council of Graduate Departments of Psychology, Ruth G. and Joseph D. Matarazzo Grant (6) California Association of Family and Consumer Sciences, Extended Education Fund (7) American Association of Family and Consumer Sciences, Massachusetts Avenue Building Assets Fund, and (8) Eunice Kennedy Shriver NICHD 5R24HD042849-12 grant awarded to the Population Research Center at The University of Texas at Austin.

Footnotes

Author Contributions SYK conceived of the study and participated in its design and coordination and drafted portions of the manuscript; YW and QC performed the statistical analyses and drafted portions of the manuscript; YS and YH participated in the interpretation of the data and helped to draft the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Contributor Information

Su Yeong Kim, University of Texas at Austin Department of Human Development and Family Sciences 108 East Dean Keeton Street, Stop A2702 Austin, TX 78712 sykim@prc.utexas.edu (512) 471-5524.

Yijie Wang, University of Texas at Austin Department of Human Development and Family Sciences 108 East Dean Keeton Street, Stop A2702 Austin, TX 78712 yiwang@prc.utexas.edu (512) 289-8136.

Qi Chen, Department of Educational Psychology University of North Texas Denton, TX 76203-1335 Qi.Chen@unt.edu 940-565-3398.

Yishan Shen, University of Texas at Austin Department of Human Development and Family Sciences 108 East Dean Keeton Street, Stop A2702 Austin, TX 78712 ysshen@utexas.edu (512) 983-7551.

Yang Hou, University of Texas at Austin Department of Human Development and Family Sciences 108 East Dean Keeton Street, Stop A2702 Austin, TX 78712 houyang223@gmail.com (512) 660-2236.

References

- Aldous J. Family, ethnicity, and immigrant youths’ educational achievements. Journal of Family Issues. 2006;27:1633–1667. doi: 10.1177/0192513X06292419. [Google Scholar]

- Berry JW. Immigration, acculturation, and adaptation. Applied Psychology. 1997;46:5–34. doi: 10.1080/026999497378467. [Google Scholar]

- Berry JW, Phinney JS, Sam DL, Vedder P. Immigrant youth in cultural transition: Acculturation, identity, and adaptation across national contexts. Erlbaum; Mahwah, NJ: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Chao RK. Extending Research on the Consequences of Parenting Style for Chinese Americans and European Americans. Child Development. 2001;72:1832–1843. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00381. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costigan CL, Dokis DP. Relations between parent-child acculturation differences and adjustment within immigrant Chinese families. Child Development. 2006;77:1252–1267. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2006.00932.x. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2006.00932.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costigan CL, Koryzma CM. Acculturation and adjustment among immigrant Chinese parents: Mediating role of parenting efficacy. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2011;58:183–196. doi: 10.1037/a0021696. doi: 10.1037/a0021696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crissey SR. [Retrieved Janurary 28, 2009];Educational Attainment in the United States: 2007. 2007 from http://www.census.gov/prod/2009pubs/p20-560.pdf.

- Eccles JS, Midgley C, Wigfield A, Buchanan CM, Reuman D, Flanagan C, Mac Iver D. Development during adolescence: The impact of stage-environment fit on young adolescents’ experiences in schools and in families. American Psychologist. 1993;48:90–101. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.48.2.90. doi: 10.1037/10254-034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eng S, Kanitkar K, Cleveland HH, Herbert R, Fischer J, Wiersma JD. School achievement differences among Chinese and Filipino American students: acculturation and the family. Educational Psychology. 2008;28:535–550. doi: 10.1080/01443410701861308. [Google Scholar]

- Farver JAM, Bhadha BR, Narang SK. Acculturation and psychological functioning in Asian Indian adolescents. Social Development. 2002;11:11–29. doi: 10.1111/1467-9507.00184. [Google Scholar]

- Fuligni AJ. The academic achievement of adolescents from immigrant families: The roles of family background, attitudes, and behavior. Child Development. 1997;68:351–363. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1997.tb01944.x. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1997.tb01944.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuligni AJ, Tseng V, Lam M. Attitudes towards family obligations among American adolescents with Asian, Latin American, and European Backgrounds. Child Development. 1999;70:1030–1044. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00075. [Google Scholar]

- Fuligni AJ, Witkow M, Garcia C. Ethnic identity and the academic adjustment of adolescents from Mexican, Chinese, and European backgrounds. Developmental Psychology. 2005;41:799–811. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.41.5.799. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.41.5.799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geary DC, Bow-Thomas CC, Liu F, Siegler RS. Development of arithmetical competencies in Chinese and American children: Influence of age, language, and schooling. Child Development. 1996;67:2022–2044. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1996.tb01841.x. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glick JE, White MJ. The academic trajectories of immigrant youths: analysis within and across cohorts. Demography. 2003;40:759–783. doi: 10.1353/dem.2003.0034. doi: 10.1353/dem.2003.0034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grieco EM. Race and Hispanic origin of the foreign-born population in the United States: 2007, American Community Survey Reports. U.S. Census Bureau; Washington, DC: 2009. Retrieved from http://www.census.gov/prod/2010pubs/acs-11.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Gutman LM, Sameroff AJ, Cole R. Academic growth curve trajectories from 1st grade to 12th grade: Effects of multiple social risk factors and preschool child factors. Developmental Psychology. 2003;39:777–790. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.39.4.777. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.39.4.777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han W-J. The academic trajectories of children of immigrants and their school environments. Developmental Psychology. 2008;44:1572–1590. doi: 10.1037/a0013886. doi: 10.1037/a0013886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeong Y-J, Acock AC. Academic achievement trajectories of adolescents from Mexican and East Asian immigrant families in the United States. Educational Review. 2014;66:226–244. doi: 10.1080/00131911.2013.769936. [Google Scholar]

- Jung T, Wickrama KAS. An introduction to latent class growth analysis and growth mixture modeling. Social and Personality Psychology Compass. 2008;2:302–317. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-9004.2007.00054.x. [Google Scholar]

- Kao G. Asian Americans as model minorities? A look at their academic performance. American Journal of Education. 1995;103:121–159. doi: 10.1086/444094. [Google Scholar]

- Kao G, Tienda M. Optimism and achievement: The educational performance of immigrant youth. Social Science Quarterly. 1995;76:1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Kiang L, Supple AJ, Stein GL, Gonzalez LM. Gendered academic adjustment among Asian American adolescents in an emerging immigrant community. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2012;41:283–294. doi: 10.1007/s10964-011-9697-8. doi: 10.1007/s10964-011-9697-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim SY, Chen Q, Li J, Huang X, Moon UJ. Parent-child acculturation, parenting, and adolescent depressive symptoms in Chinese immigrant families. Journal of Family Psychology. 2009;23:426–437. doi: 10.1037/a0016019. doi: 10.1037/a0016019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim SY, Chen Q, Wang Y, Shen Y, Orozco-Lapray D. Longitudinal linkages among parent-child acculturation discrepancy, parenting, parent-child sense of alienation, and adolescent adjustment in Chinese immigrant families. Developmental Psychology. 2013 doi: 10.1037/a0029169. doi: 10.1037/a0029169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim SY, Shen Y, Huang X, Wang Y, Orozco-Lapray D. Chinese American parents’ acculturation and enculturation, bicultural management difficulty, depressive symptoms, and parenting. Asian American Journal of Psychology. doi: 10.1037/a0035929. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lau AS, McCabe KM, Yeh M, Garland AF, Wood PA, Hough RL. The acculturation gap-distress hypothesis among high-risk Mexican American families. Journal of Family Psychology. 2005;19:367–375. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.19.3.367. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.19.3.367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ng SSN, Rao N. Chinese number words, culture, and mathematics learning. Review of Educational Research. 2010;80:180–206. doi: 10.3102/0034654310364764. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen A-MD, Benet-Martínez V. Biculturalism and adjustment: A meta-analysis. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology. 2013;44:122–159. doi: 10.1177/0022022111435097. [Google Scholar]

- Roer-Strier D, Strier R, Este D, Shimoni R, Clark D. Fatherhood and immigration: challenging the deficit theory. Child and Family Social Work. 2005;10:315–329. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2206.2005.00374.x. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenthal DA, Feldman SS. The influence of perceived family and personal factors on self-reported school performance of Chinese and western high school students. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 1991;1:135–154. doi: 10.1207/s15327795jra0102_2. [Google Scholar]

- Rumbaut RG. The crucible within: Ethnic identity, self-esteem, and segmented assimilation among children of immigrants. International Migration Review. 1994;28:748–794. [Google Scholar]

- Ryder AG, Alden LE, Paulhus DL. Is acculturation unidimensional or bidimensional? A head-to-head comparison in the prediction of personality, self-identity, and adjustment. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2000;79:49–65. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.79.1.49. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.79.1.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Satorra A, Bentler PM. A scaled difference Chi-square test statistic for moment structure analysis. Psychometrika. 2001;66:507–514. doi: 10.1007/s11336-009-9135-y. doi: 10.1007/BF02296192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smetana JG, Campione-Barr N, Metzger A. Adolescent development in interpersonal and societal contexts. Annual Review of Psychology. 2006;57:255–284. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.57.102904.190124. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.57.102904.190124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suárez-Orozco C, Gaytán FX, Bang HJ, Pakes J, O’Connor E, Rhodes J. Academic trajectories of newcomer immigrant youth. Developmental Psychology. 2010;46:602–618. doi: 10.1037/a0018201. doi: 10.1037/a0018201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sy SR, Schulenberg JE. Parent beliefs and children’s achievement trajectories during the transition to school in Asian American and European American families. International Journal of Behavioral Development. 2005;29:505–515. doi: 10.1080/01650250500147329. [Google Scholar]

- Telzer EH. Expanding the acculturation gap-distress model: An integrative review of research. Human Development. 2010;53:313–340. doi: 10.1159/000322476. [Google Scholar]

- Tran N, Birman D. Questioning the model minority: Studies of Asian American academic performance. Asian American Journal of Psychology. 2010;1:106–118. doi: 10.1037/a0019965. [Google Scholar]

- Turney K, Kao G. Barriers to school involvement: Are immigrant parents disadvantaged? The Journal of Educational Research. 2009;102:257–271. doi: 10.3200/JOER.102.4.257-271. [Google Scholar]

- Updegraff KA, Umaña-Taylor AJ, McHale SM, Wheeler LA, Perez-Brena NJ. Mexican-origin youths’ cultural orientations and adjustment: Changes from early to late adolescence. Child Development. 2012;83:1655–1671. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2012.01800.x. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2012.01800.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Census Bureau . The American community—Asians: 2004, American Community Survey Reports. U.S. Census Bureau; Washington, DC: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Census [Retrieved November 11, 2012];Selected population profile in the United States, 2010 American Community Survey 1-Year Estimates. 2010 http://factfinder2.census.gov/faces/tableservices/jsf/pages/productview.xhtml?pid=ACS_10_1YR_S0201&prodType=table.

- Weaver SR, Kim SY. A person-centered approach to studying the linkages among parent– child differences in cultural orientation, supportive parenting, and adolescent depressive symptoms in Chinese American families. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2008;37:36–49. doi: 10.1007/s10964-007-9221-3. doi: 10.1007/s10964-007-9221-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willingham WW, Pollack JM, Lewis C. Grades and test scores: Accounting for observed differences. Journal of Educational Measurement. 2002;39:1–37. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-3984.2002.tb01133.x. [Google Scholar]

- Witkow MR, Fuligni AJ. Achievement goals and daily school experiences among adolescents with Asian, Latino, and European American backgrounds. Journal of Educational Psychology. 2007:584–596. doi: 10.1037/0022-0663.99.3.584. [Google Scholar]

- Yan W, Lin Q. Parent involvement and mathematics achievement: Contrast across racial and ethnic groups. The Journal of Educational Research. 2005;99:116–127. doi: 10.3200/JOER.99.2.116. [Google Scholar]

- Yoon E, Langrehr K, Ong LZ. Content analysis of acculturation research in counseling and counseling psychology: A 22-year review. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2011;58:83–96. doi: 10.1037/a0021128. doi: 10.1037/a0021128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]