Abstract

Research exhibits a robust relation between child hurricane exposure, parent distress, and child posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). This study explored parenting practices that could further explicate this association. Participants were 381 mothers and their children exposed to Hurricane Katrina. It was hypothesized that 3–7 months (T1) and 14–17 months (T2) post-Katrina: (a) hurricane exposure would predict child PTSD symptoms after controlling for history of violence exposure and (b) hurricane exposure would predict parent distress and negative parenting practices, which, in turn, would predict increased child PTSD symptoms. Hypotheses were partially supported. Hurricane exposure directly predicted child PTSD at T1 and indirectly at T2. Additionally, several significant paths emerged from hurricane exposure to parent distress and parenting practices, which were predictive of child PTSD.

Children who experience a natural disaster are at risk for developing symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD; Norris et al., 2002; Osofsky, Osofsky, Kronenberg, Brennan, & Cross, 2009). Although research suggests that many children who report PTSD symptoms following a natural disaster quickly experience significant symptom reduction, a subset experience chronic distress (La Greca, Silverman, Vernberg, & Prinstein, 1996; Weems et al., 2010). Indeed, Weems and colleagues found that PTSD symptoms in Hurricane Katrina-exposed youth did not significantly decline from 24 to 30 months postdisaster.

Weems and Overstreet (2009) hypothesized that large-scale disasters can disrupt ecological systems (Brofenbrenner, 1979) that influence child development and may account for differential outcomes in disaster-exposed youth. To date, research has focused largely on contexts proximal to the child, or microsystem influences, relevant to the family environment (Norris et al., 2002). For instance, post-Katrina studies document a significant association between child hurricane exposure, parent distress, and negative child psychological outcomes (Scheeringa & Zeenah, 2008; Spell et al., 2008). However, little research has focused on related microsystem factors that can further explicate this association. Experts have postulated that parent disaster-related distress may disrupt positive, effective parenting practices and discipline, which can increase the risk for poor child outcomes (Costa, Weems, & Pina, 2009; Gerwitz, Forgatch, & Wieling, 2008; Scaramella, Sohr-Preston, Callahan, & Mirabile, 2008).

The purpose of the current study is to further examine microsystem influences that might affect the PTSD risk for children exposed to Katrina by using a prospective design with information collected from both parents and children. Of particular interest are the interrelationships between hurricane exposure and parenting variables that would be amenable to change through clinical intervention. Such variables include parent distress (broadly defined as parent psychopathology, parent social support, and parent mal-adaptive coping) and parenting practices. The association among the parent distress variables is documented in the disaster literature and each variable has demonstrated unique associations with parenting practices and related child outcomes in nondisaster research (e.g., Leung & Slep, 2006; McKee, Harvey, Danforth, Ulaszek, & Friedman, 2004); however, the contributions of these variables to parenting practices in disaster circumstances have not been explored. Two commonly researched parenting practices known to affect children’s adjustment following traumatic experiences—corporal punishment and inconsistent child routines (e.g., Gershoff, 2002; Nordahl, Ingul, Nordvik, & Wells, 2006)—were selected for investigation. Unlike almost all other postdisaster studies, data were collected from both children and parents. Lastly, children’s history of community violence exposure was included as a control variable, given its prevalence in the sample and its association with PTSD in children (Fowler, Tompsett, Braciszewski, Baltes, & Jacques-Tiura, 2009; Zinzow et al., 2009).

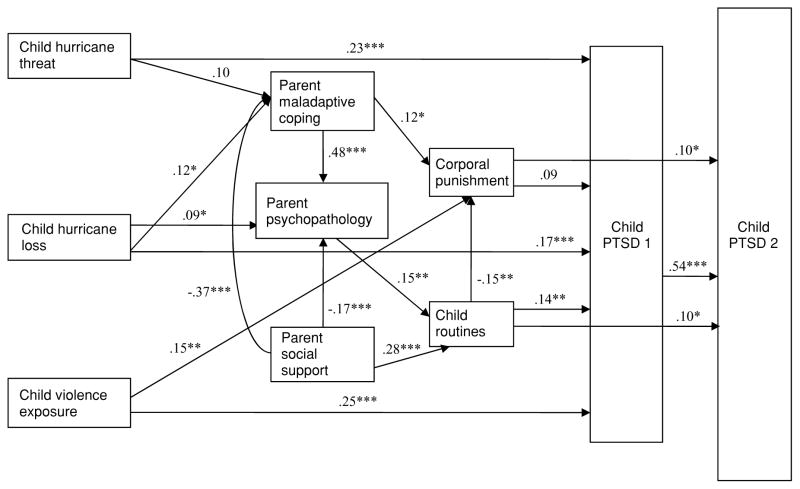

Figure 1 presents the proposed model and hypothesized relationships among the variables of interest. It was hypothesized that as hurricane exposure increased, child risk for PTSD would increase. Based on prior research documenting an interaction effect between child hurricane exposure and parent psychopathology (Spell et al., 2008), it also was hypothesized that the negative effects of hurricane exposure on child PTSD would be exacerbated by the associations between parent psychopathology, related parent distress, and negative parenting practices, such that children at greatest risk for chronic PTSD would be those whose parents reported greater levels of distress, more use of corporal punishment, and less-consistent child routines. Finally, it was postulated that these paths would remain significant even after controlling for other child trauma experiences (violence exposure) that could account for the rates of PTSD symptoms in the sample studied.

Figure 1.

Proposed model: Predictors of child posttraumatic stress disorder symptomatology post-Hurricane Katrina.

METHOD

Participants

Participants were 381 parent–child dyads from New Orleans and neighboring parishes affected by Hurricane Katrina. The majority of participants lived in New Orleans at the time of landfall and 74% of the sample was displaced following the storm. Most adult respondents were female caretakers, with two father participants. Child participants were fourth through eighth graders ranging in age from 8 to 16 (M = 12, SD = 2). The sample was primarily African American (68%), with 24% being Caucasian and 8% comprised of other ethnicities. The majority of the parents (63%) had completed high school; 21% obtained a college degree, and 16% reported having less than a 12th grade education. The average reported household income was under $25,000.

Measures

Children completed a Hurricane Exposure Questionnaire similar to that used in other studies of youth adjustment posthurricane (e.g., La Greca, Silverman, & Wasserstein, 1998; Vernberg, La Greca, Silverman, & Prinstein, 1996). The measure comprised 15 dichotomously rated items yielding two factors: life-threatening experiences (6 items) and loss/disruption (9 items). Factor scores are obtained by totaling item scores. The sampled items and the percentages of children who endorsed them included: “Did windows or doors break in the place you stayed during the hurricane?” (16%); “Was your home damaged badly or destroyed by the hurricane?” (45%); “Were your toys or clothes ruined by the hurricane?” (40%). Given that a similar measure completed by the parents was very highly correlated with scores on the child measure (p < .001), and the child report has been used as the primary variable of interest in past studies (e.g., Spell et al., 2008), only the child report measure was included in this study.

Children completed age-appropriate measures of community violence exposure. Scores were converted to z scores due to measure differences.

Youth 11–16 years old completed the 32-item Screen for Adolescent Violence Exposure (Hastings & Kelley, 1997), comprising three subscales (home, school, and neighborhood violence) and a total violence score. Items are rated based on frequency of occurrence (0 = never, 4 = almost always). The Screen for Adolescent Violence Exposure has adequate psychometrics (Hastings & Kelley, 1997). The combined neighborhood and school violence factors at T1 were used (α = .97 for the current sample) as a measure of violence exposure.

Youth aged 8 to 10 completed the KID-SAVE (Flowers, Hastings, & Kelley, 2000), an adaptation of the Screen for Adolescent Violence Exposure. The KID-SAVE includes 34 items, rated on frequency of occurrence (0 = never, 2 = a lot). The study used the total score of neighborhood and school violence measured at T1 (α = .89 for the current sample) as a measure of child violence exposure.

The UCLA PTSD Reaction Index Revised (Pynoos, Rodriguez, Steinberg, Stuber, & Frederick, 1998) is a revised version of the Child PTSD Reaction Index (Nader, Pynoos, Fairbanks, & Frederick, 1990). The 22 items assess PTSD symptoms in youth and have very good psychometric properties (Steinberg, Brymer, Decker, & Pynoos, 2004). The Continuous Index Summary Score was used (α = .91 for T1, α = .92 for T2 in current sample) as a measure of child PTSD at T1 and T2.

The Symptom Checklist-90-Revised (SCL-90-R; Derogatis, 1994) is a self-report measure of psychological symptoms, with adequate psychometric properties. Participants rate how much they experienced each symptom on a 5-point scale. The Global Severity Index (GSI) was used to measure parent psychopathology at T1 (α = .99).

Parents completed the Brief COPE (Carver, 1997) a 28-item scale measuring adult coping at T1. The Brief COPE yields 14 two-item scales that represent a variety of coping styles; however, as suggested by the author, factor analyses were conducted for this sample, which yielded two factors: adaptive coping (16 items; α = .91) and maladaptive coping (9 items; α = .82). Factors were determined based upon the following criteria: scree plot analysis, eigenvalues over 1.0, simple structure, and factor loadings above .40. Preliminary analyses determined a significant relation between maladaptive coping and the outcome variables of interest, thus, this subscale was included as a measure of parent maladaptive coping and included items such as “I’ve been using drugs or alcohol” and “I’ve been giving up the attempt to cope.”

Parents completed the Interpersonal Support and Evaluation List (Cohen & Hoberman, 1983), 40 items measuring perceived social support at T1. The scale yields a total score and four subscale scores. The total score was used (α = .93 for the current sample) as a measure of parental social support.

The Alabama Parenting Questionnaire (Shelton, Frick, & Wootton, 1996) measures parenting practices and includes 42 items comprising six subscales. Parents rate the frequency with which they use each parenting behavior. Based on preliminary analyses and to avoid potential multicollinearity problems resulting from utilizing multiple highly correlated scales, this study used only the corporal punishment subscale (α = .70), which included items such as, “You hit your child with a belt” and “You slap your child.”

The Child Routines Inventory (Sytsma, Kelley, & Wymer, 2001) is a 38-item parent-report measure designed to assess youths’ daily routines. The measure yields four subscales and a total score. Parents rate how often their child completes each routine on a 5-point scale. The scale has good internal consistency (α = .90) and test-retest reliability (r = .86; Sytsma et al., 2001). The total score was used (α = .94) as a measure of child routines.

Procedure

Following institutional review board approval, six reopened schools serving children from all over the city were contacted for recruitment. Flyers soliciting participation were sent to parents through their children. Consenting parents completed the questionnaire packet and returned it in a sealed envelope via their child to classroom teachers. Approximately 36% of contacted parents agreed to participate in the study. Assenting youth completed questionnaires at school under supervision. Questionnaires were read to younger children and those with reading difficulties. Data collection with children at T2 was identical to that of T1. At T1, participants were compensated based on the preference of school personnel. Children received either $5 or a class pizza party. Parents were entered into a cash prize drawing. At T2, families were compensated $25. The current study used parent and child measures from T1 and only the UCLA PTSD Index from T2. There was an 85% retention rate for child participants from T1 to T2.

Data Analysis

Fifteen percent of study participants were missing item-level data for assessment measures included in this study. Multiple imputation (MI) techniques were used to impute or “fill in” the missing data. Multiple imputation replaces each missing value by drawing a random sample of the missing values from its distribution of complete values (observed and missing). The PROC MI and PROC MIANALYZE procedures in SAS version 9.1 were used to complete MI for this dataset.

RESULTS

Table 1 shows correlations, means, standard deviations, and Cronbach’s alpha for all variables. The mean for hurricane threat was .65 and the mean for hurricane loss/disruption was 2.97, reflecting relatively mild exposure. There was a significant decrease (p < .001) in children’s mean PTSD symptom severity from T1 (18.8) to T2 (14.8). Specifically, at T1, 13% of the sample met the PTSD cutoff (>37), the score that has the greatest sensitivity/specificity for detecting PTSD (Steinberg et al., 2004). The percentage declined to 8% at T2. Participants above the cutoff at T1 were much more likely to be above the cutoff at T2 (OR = 11.8, p < .001) compared to those below the cutoff.

Table 1.

Means, Standard Deviations, Reliability Estimates (in parentheses) and Intercorrelations for Predictor and Outcome Variables

| Measure | Range | M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Child hurricane threat | 0–6 | 0.65 | 0.91 | (.52) | |||||||||||

| 2. Child hurricane loss | 0–9 | 2.97 | 2.26 | .37*** | (.70) | ||||||||||

| 3. Child violence exposure | z-scores | −0.05 | 0.94 | .30*** | .18** | (.97) | |||||||||

| 4. Parent hurricane loss | 0–6 | 3.44 | 2.45 | .23*** | .60*** | .08 | (.67) | ||||||||

| 5. Parent hurricane threat | 0–10 | .53 | .95 | .24*** | .14* | .04 | .33*** | (.75) | |||||||

| 6. Parent psychopathology | 0–4 | .15 | .14 | .12* | .21*** | .10 | .26*** | .14* | (.99) | ||||||

| 7. Parent maladaptive coping | 1–4 | 1.52 | .56 | .19** | .21** | .15** | .23*** | .21*** | .56*** | (.82) | |||||

| 8. Parent social support | 0–120 | 81.97 | 21.57 | −.11* | −.12* | −.15** | −.14* | −.21*** | −37*** | .40*** | (.93) | ||||

| 9. Corporal punishment | 3–15 | 6.18 | 2.92 | .09 | .12* | .19** | .10 | .13* | .10 | .15** | .12* | (.70) | |||

| 10. Routines | 0–152 | 107.49 | 21.79 | −.04 | −.01 | −.10 | .02 | −.13* | .05 | −.05 | .22*** | −.18** | (.94) | ||

| 11. Child PTSD at Time 1 | 0–72 | 18.79 | 15.11 | .37*** | .32*** | .36*** | .13* | −.02 | .18** | .19** | −.15** | .16** | .09 | (.91) | |

| 12. Child PTSD at Time 2 | 0–72 | 14.78 | 13.72 | .24*** | .15** | .24*** | .05 | −.06 | .17** | .15** | −.13* | .17** | .12* | .57*** | (.92) |

Note. PTSD = posttraumatic stress disorder.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p ≤ .001.

Path analysis, specifically the CALIS procedure in SAS version 9.1.3, was used to trace the impact of child and parent variables reported at T1 on child-reported PTSD symptoms at T2. All analyses utilized the maximum likelihood method for parameter estimation on the variance-covariance matrix, rather than the correlation matrix. The analysis began with the most-saturated model and exogenous variables were allowed to covary. Highly nonsignificant paths were removed from the model and each resultant model was evaluated based on the chi-square difference test and a series of indices of close fit. Derivation of the final model was an iterative process, balancing between conservative, theoretical justifications, and best model fit. The final model (Figure 2) has good to superior fit (Bollen & Long, 1993): χ2 (20) = 14.48, p < .81; root mean square error of approximation estimate = .000, 90% confidence interval = .000–.031, with associated probability of close fit = .996; Bentler’s Comparative Fit Index = 1.00, Akaike’s information criterion = −25.52; and Hoelter’s critical N = 694. The final model accounts for 33.2% of the variance for PTSD at T2 and 28.5% for PTSD at T1. All standardized path coefficients included in Figure 2 have meaningful magnitude and are statistically significant (p < .05). Based on Hatcher’s (1994) recommendation of required sample size of at least five times the number observed variables, there was sufficient power to conduct a path analysis of 10 observed variables.

Figure 2.

Final model: Predictors of child posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) post-hurricane. (All path coefficients are standardized.)

*p < .05 **p < .01 ***p < .001.

Once the final path model was derived, direct and indirect effects were tested for their individual contribution in explaining the relationship between child variables at T1 and PTSD symptoms at T2. Because the multivariate normal distribution of direct and indirect effects could not be reasonably assumed in a finite sample, Preacher and Hayes’ (2008) method of biased-corrected bootstrap confidence intervals was used to test for significance of these effects. Effects were estimated with unstandardized regression coefficients.

As seen in Figure 2, each of the three exogenous variables, hurricane threat, loss/disruption, and community violence exposure, was statistically associated (p < .001) with higher levels of child PTSD at T1 (one unit standard deviation increase resulted in a direct increase of .23, .17, and .25 units, respectively, in child PTSD). Each exogenous variable was also indirectly associated with higher levels of child PTSD at T1 through the parent distress and parenting practices variables. Specifically, the path from hurricane threat was associated with an increase in parent maladaptive coping (β = .10) and in corporal punishment (β = .12), and marginally associated with an increase in child PTSD at T1 (β = .09). Additionally, the path from hurricane loss/disruption was associated with an increase in parent maladaptive coping (β = .12), an increase in corporal punishment (β = .12), and a marginal increase in PTSD at T1 (β = .09). The path from hurricane loss/disruption also was associated with increased parent psychopathology (β = .09), increased child routines (β = .15), and increased child PTSD at T1 (β = .14). Both hurricane threat and loss/disruption were indirectly associated with parent psychopathology through parent maladaptive coping (β = .48), making hurricane exposure indirectly associated with child routines and, ultimately, child PTSD through parent psychopathology. Interestingly, the control variable of community violence exposure was associated with increased corporal punishment (β = .15), which in turn was marginally associated with increased PTSD at T1 (β = .09).

Notably, parent social support emerged as an exogenous variable. Parent social support was positively associated with child routines (β = .28), which was associated with PTSD at T1 (β = .14). Parent social support was negatively associated with parent maladaptive coping (β = −.37), which was associated with corporal punishment and PTSD at T1. Lastly, child routines were negatively associated with corporal punishment (β = −.15).

Table 2 lists the direct effect, (total) indirect effect, and total effect (sum of direct and indirect) that each of the three child exogenous variables has on PTSD at T1. The distinctions of direct and indirect effects are based on the final path model in Figure 2. The total indirect effect of hurricane threat (0.39) is the sum of its effects on PTSD T1, via parent maladaptive coping, parent psychopathology, corporal punishment, and child routines. Similarly, the total indirect effect of hurricane loss, via parent mal-adaptive coping, parent psychopathology, corporal punishment, and child routines, is 0.13; the total indirect effect of community violence exposure on PTSD T1, via corporal punishment, is 0.27. In sum, hurricane threat has significant direct, indirect (via parent variables), and total effects on PTSD at T1. Hurricane loss has significant direct and total effects, but nonsignificant indirect effects (via parent variables) on PTSD at T1, and community violence exposure has significant direct, indirect (via parent variable), and total effects on PTSD at T1.

Table 2.

Unstandardized Coefficient Estimates of Exogenous Variables on PTSD at T1 and T2

| Exogenous variables | Direct and indirect effects on PTSD at T1

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Direct effect | SE | Total indirect effecta | 95% CIb | Total effect | SE | |

| Child hurricane threat | 5.46*** | 0.72 | 0.39 | 0.10–0.87 | 5.85*** | 0.72 |

| Child hurricane loss | 1.87*** | 0.32 | 0.13 | −0.01–0.46 | 2.00*** | 0.32 |

| Child violence Exposure | 5.55*** | 0.77 | 0.27 | 0.03–0.71 | 5.82*** | 0.76 |

| Exogenous variables | Direct and indirect effects on PTSD at T2

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Direct effect | SE | Total indirect effecta | 95% CIb | Total effect | SE | |

| Child hurricane threat | 0.38 | 0.76 | 3.25 | 2.13–4.62 | 3.63*** | 0.83 |

| Child hurricane loss | −0.22 | 0.30 | 1.20 | 0.74–1.73 | 0.99* | 0.34 |

| Child violence Exposure | 0.41 | 0.72 | 3.05 | 1.96–4.31 | 3.46*** | 0.79 |

Note. PTSD = Posttraumatic stress disorder.

The sum of the indirect effects each child exogenous variable has on PTSD at T1 or T2, through the parent variables.

Based on Preacher and Hayes (2008) macro for models with multiple indirect effects. Confidence Intervals are estimated using bias-corrected bootstrapping.

p < .05.

p < .001.

Posttraumatic stress disorder at T1 was the strongest predictor of PTSD at T2. The three child-reported exogenous variables were indirectly associated with PTSD at T2 through PTSD at T1, as well as through the parenting practices of corporal punishment and child routines. Additionally, the parenting practices were each significantly associated with PTSD at T2. Table 2 lists the direct effect, (total) indirect effect, and total effect (sum of direct and indirect) that each of the three child exogenous variables has on PTSD at T2. The total indirect effect of hurricane threat is the sum of its effects on PTSD T2, via parent maladaptive coping, parent psychopathology, corporal punishment, child routines, and PTSD at T1. Similarly, the total indirect effect of hurricane loss on PTSD at T2, via parent maladaptive coping, parent psychopathology, corporal punishment, child routines, and PTSD at T1 is 1.20; the total indirect effect of community violence exposure on PTSD T2, via corporal punishment and PTSD at T1, is 3.05. In summary, hurricane threat, hurricane loss, and community violence exposure do not have significant direct effects on PTSD at T2. These exogenous variables, however, have significant indirect (via parent variables and PTSD at T1) and total effects on PTSD at T2.

DISCUSSION

This study sought to explicate the current understanding of the association between child disaster exposure, parent psychopathology, and child outcome previously documented in disaster research (Scheeringa & Zeenah, 2008; Spell, et al., 2008). The role of additional microsystem influences, including parent maladaptive coping, parent social support, corporal punishment, and child routines, that could exacerbate risk of child PTSD following disaster were explored at 3–7 months and 14–17 months post-Katrina. Children’s community violence exposure was included as a control variable, given its prevalence in the sample and its association with PTSD in children (Fowler et al., 2009; Zinzow et al., 2009). Several hypotheses were postulated and predictions were partially supported.

As expected, higher hurricane exposure was related to more child PTSD symptoms at T1, with 13% of the sample reporting significant PTSD symptoms at T1. Importantly, the relationship between hurricane exposure and child PTSD at T1 remained significant after controlling for community violence exposure, indicating that hurricane exposure is a unique contributor to child PTSD even for children who have experienced other traumatic events. Hurricane exposure and violence exposure were found to be indirectly related to PTSD at T2 through PTSD at T1, suggesting that hurricane and trauma experiences can result in chronic child PTSD. Moreover, those children that reported high levels of symptoms at T1 were 12 times as likely to report significant symptoms at T2. Implications are twofold. First, the earliest possible identification and intervention with children experiencing PTSD symptoms is critical. Second, a thorough examination of trauma history may aid treatment planning postdisaster, especially considering the emerging evidence that the strength of the relationship between disaster exposure and related outcomes can change when community violence exposure is present (Aber, Gershoff, Ware, & Kotler, 2004; Chemtob, Nomura, & Abramovits, 2008).

Consistent with previous studies (Sheeringa & Zeanah, 2008; Spell et al. 2008), the association between hurricane exposure and child PTSD at T2 was impacted by microsystem influences. Specifically, a significant path emerged indicating that children who reported more hurricane loss had parents who reported more maladaptive coping, and in turn, these parents were more likely to use corporal punishment, which increased their children’s risk for PTSD symptoms at T1 and T2. Research has indicated that parent maladaptive coping in nondisaster environments is related to poor parenting and discipline practices (McKee et al., 2004); current findings suggests this association exists in postdisaster environments and exacerbates risk for child psychopathology.

Surprisingly, parents of children who reported higher levels of hurricane loss/or disruption reported significantly higher levels of psychological symptoms and these parents reported employing more child routines, which placed children at greater risk for chronic PTSD post-Katrina. Prior research suggests an inverse relationship between maternal psychopathology and child routines, such that women who were more distressed were less likely to maintain routines (Leiferman, Ollendick, Kunkel, & Christie, 2005). Research also has indicated that reinstitution of familiar routines is important in reducing trauma-related symptoms in children (Boyce, 1981; Foy, 1992) and many disaster-related materials suggest that child routines be resumed quickly (e.g., American Red Cross, 1992). Interestingly, in the only other published study examining child routines postdisaster, findings indicated that the reinstitution of roles and routines was the most common coping assistance provided by parents postdisaster, but that this assistance was unrelated to children’s PTSD symptom severity (Prinstein, La Greca, Vernberg, & Silverman, 1996). Perhaps the routines implemented by parents with high levels of distress in postdisaster circumstances are qualitatively different from those employed by healthier parents. Distressed parents might implement routines in a harsh or controlling manner, which can elevate child anxiety (Rapee, 1997). Clearly, more research is warranted on child routines. Although child community violence exposure was included in the model as a control variable, children who reported greater exposure to community violence had parents who used more corporal punishment, which was associated with increased child PTSD symptoms. It is plausible that the parent–child dyads experience similar amounts of community violence exposure, and research indicates that mothers with higher levels of trauma exposure are more likely to use corporal punishment (Banyard, Williams, & Siegal, 2003). Perhaps parents who experienced higher levels of violence exposure or trauma relied on corporal punishment to suppress their children’s negative behavior immediately, thereby alleviating their own distress, despite long-term negative outcomes. Future research could measure parents’ prior trauma history and parenting practices to help determine the relations among these variables in disaster-affected families.

Significant associations emerged between hurricane exposure and parent psychopathology and coping, but not for social support. It is likely that parents and children living together at the time of the hurricane had similar hurricane experiences, and though these parents were at risk for psychological challenges and poor coping postdisaster, their social support system did not appear to be as directly impacted. Perhaps because the sample of children included in this study remained in the New Orleans area and were enrolled in open schools, the social systems for these parents were not as disrupted as parents who relocated to new cities.

Consistent with past research, parents who reported more negative coping and less social support reported more psychological symptoms (Norris et al., 2002). Current findings offer further insight into the interplay of these factors on parenting practices and the direct and indirect effect on children’s mental health. Another significant association in the final model was the inverse relationship between child routines and corporal punishment. That is, families who reported more child routines and whose children were at greater risk for PTSD were often the same families that reported less corporal punishment, which decreased the risk for PTSD. Clearly, there are multiple pathways that can lead to chronic PTSD in disaster-affected youth.

There are several limitations of this study. First, outcome variables were limited to paper and pencil measures, with no inclusion of observational or interview data. Second, the harshness of the corporal punishment reported by parents was not assessed. Certainly, if parenting behavior verged on abusive, the children’s PTSD risk would be much greater (e.g., Famularo, Fenton, Kinscherff, Ayoub, & Barnum, 1994). Further, statistical methods limited the number of variables that could be included for examination in the path analyses, and, thus, did not allow for the exploration of many potentially important microsystem variables, such as parent hurricane exposure or other types of parent behaviors that may be relevant to child outcome. Lastly, the convenience sample included in this study limits the external validity of the findings for other Katrina-affected youth, as well as those impacted by other disasters.

The findings contribute to the literature in several ways. First, this study further validates that children who exhibit PTSD symptoms in the first few months following disaster should be considered at risk for chronic PTSD that can continue over a year postdisaster. Second, based on information collected from both parents and children impacted by Katrina, the results suggest there is greater complexity to the hurricane exposure-child outcome relation than is documented in past research. Although parent psychopathology has been linked to child adverse outcomes following traumatic events (e.g., Sack, Clarke, & Seely, 1995; Spell et al., 2008), current findings suggest no direct effect between parent distress variables and child PTSD once parenting practices are considered. Indeed, parent psychopathology, social support, and negative coping were only associated with child PTSD through parenting practices.

In conclusion, it is imperative that evidence-based prevention and intervention efforts targeting the development of youth PTSD symptoms early in postdisaster circumstances be widely disseminated and implemented in disaster response planning and efforts. Further, for children who develop chronic PTSD postdisaster, targeted long-term, evidence-based interventions should be made available (Weems et al., 2010). In addition, prevention work targeting important parenting practices that directly affect the risk and maintenance of PTSD under these conditions should be designed and tested.

Acknowledgments

This material is based upon work supported by the US Department of Homeland Security under Award Number: 2008-ST-061-ND 0001 and a research grant from the National Institute of Mental Health (RMH-078148A). The views and conclusions contained in this document are those of the authors and should not be interpreted as necessarily representing the official policies, either expressed or implied, of the US Department of Homeland Security.

Footnotes

This article was edited by the journal’s Editor-Elect, Daniel S. Weiss.

Contributor Information

Mary Lou Kelley, Louisiana State University.

Shannon Self-Brown, Georgia State University.

Brenda Le, Tulane University.

Julia Vigna Bosson, Louisiana State University.

Brittany C. Hernandez, Louisiana State University

Arlene T. Gordon, Louisiana State University

References

- Aber JL, Gershoff E, Ware A, Kotler J. Estimating the effects of September 11th, 2001, and other forms of violence on the mental health and social development of New York City’s youth: A matter of context. Applied Developmental Science. 2004;8:111–129. [Google Scholar]

- American Red Cross. ARC Publication No 4475. Baltimore: Author; 1992. Helping children cope with disaster. [Google Scholar]

- Banyard VL, Williams LM, Siegal JA. The impact of complex trauma and depression on parenting: An exploration of mediating risk and protective factors. Child Maltreatment. 2003;8:333–349. doi: 10.1177/1077559503257106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bollen KA, Long JS. Testing structural equation models. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Boyce WT. Interaction between social variables and stress research. Journal of Health & Social Behavior. 1981;22:194–195. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner U. The ecology of human development: Experiments by nature and design. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Carver CS. You want to measure coping but your protocol’s too long: Consider the Brief COPE. International Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 1997;4:92–100. doi: 10.1207/s15327558ijbm0401_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chemtob CM, Nomura Y, Abramovits RA. Impact of conjoined exposure to the World Trade Center attacks and the other traumatic events on the behavioral problems of preschool children. Archives of Pediatric and Adolescent Medicine. 2008;162:126–133. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2007.36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S, Hoberman H. Positive events and social supports as buffers of life change stress. Journal of Applied Social Psychology. 1983;13:99–125. [Google Scholar]

- Costa NM, Weems CF, Pina AA. Hurricane Katrina and youth anxiety: The role of perceived attachment beliefs and parenting behaviors. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 2009;23:935–941. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2009.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derogatis LR. SCL-90-R: Administration, scoring and procedures manual. Minneapolis: National Computer Systems, Inc; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Famularo R, Fenton T, Kinscherff, Ayoub C, Barnum R. Maternal and child posttraumatic stress disorder in cases of child maltreatment. Child Abuse & Neglect. 1994;18:27–36. doi: 10.1016/0145-2134(94)90093-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flowers AL, Hastings TL, Kelley ML. Development of a screening instrument for exposure to violence in children: The KID-SAVE. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment. 2000;22:91–104. [Google Scholar]

- Fowler PJ, Tompsett CJ, Braciszewski JM, Baltes BB, Jacques-Tiura AJ. Community violence: A meta-analysis on the effect of exposure and mental health outcomes of children and adolescents. Development and Psychopathology. 2009;21:227–259. doi: 10.1017/S0954579409000145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foy DW. Treating posttraumatic stress disorder: Cognitive behavioral strategies. New York: Guilford Press; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Gershoff ET. Corporal punishment by parents and associated behaviors and experiences: A meta-analytic and theoretical review. Psychological Bulletin. 2002;128:539–579. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.128.4.539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerwitz AH, Forgatch M, Wieling L. Parenting practices as potential mechanisms for child adjustment following mass trauma. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy. 2008;34:177–192. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-0606.2008.00063.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hastings TL, Kelley ML. Development and validation of the Screen for Adolescent Violence Exposure (SAVE) Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 1997;25:511–520. doi: 10.1023/a:1022641916705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatcher L. A step-by-step approach to using the SAS system for factor analysis and structural equation modeling. Cary, NC: SAS Institute Inc; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- La Greca AM, Silverman WK, Vernberg EM, Prinstein MJ. Symptoms of posttraumatic stress after Hurricane Andrew: A prospective study. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1996;64:712–723. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.64.4.712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- La Greca AM, Silverman WK, Wasserstein SB. Children’s predisaster functioning as a predictor of posttraumatic stress following Hurricane Andrew. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1998;66:883–892. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.66.6.883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leiferman JA, Ollendick TH, Kunkel D, Christie IC. Mothers’ mental distress and parenting practices with infants and toddlers. Archives of Women’s Mental Health. 2005;8:243–247. doi: 10.1007/s00737-005-0098-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leung DW, Slep AM. Predicting inept discipline: The role of parental depressive symptoms, anger, and attributions. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2006;74:524–534. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.74.3.524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKee TE, Harvey E, Danforth JS, Ulaszek WR, Friedman JL. The relation between parental coping styles and parent-child interaction before and after treatment for children with ADHD and oppositional behavior. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2004;33:158–168. doi: 10.1207/S15374424JCCP3301_15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nader KO, Pynoos R, Fairbanks L, Frederick C. Children’s PTSD reactions one year after a sniper attack at their school. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1990;147:1526–1530. doi: 10.1176/ajp.147.11.1526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nordahl HM, Ingul JM, Nordvik H, Wells A. Does maternal psychopathology discriminate between children with DSM-IV generalized anxiety disorder or oppositional defiant disorder? The predictive validity of maternal axis I and axis II psychopathology. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2006;16:87–95. doi: 10.1007/s00787-006-0578-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norris FH, Friedman MJ, Watson PJ, Byrne CM, Diaz E, Kaniasty K. 60,000 disaster victims speak, part I: An empirical review of the empirical literature, 1981–2001. Psychiatry. 2002;65:207–239. doi: 10.1521/psyc.65.3.207.20173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osofsky HJ, Osofsky JD, Kronenberg M, Brennan A, Hansel TC. Posttraumatic stress symptoms in children after Hurricane Katrina: Predicting the need for mental health services. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 2009;79:212–220. doi: 10.1037/a0016179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preacher KJ, Hayes AF. Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behavior Research Methods. 2008;40:879–891. doi: 10.3758/brm.40.3.879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prinstein MJ, La Greca AM, Vernberg EM, Silverman WK. Children’s coping assistance: How parents, teachers, and friends help children cope after a natural disaster. Journal of Child Clinical Psychology. 1996;25:463–475. [Google Scholar]

- Pynoos R, Rodriguez N, Steinberg A, Stuber M, Frederick C. The UCLA PTSD Reaction Index for DSM-IV (Revision 1) Los Angeles: UCLA Trauma Psychiatry Program; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Rapee RM. The potential role of childrearing practices in the development of anxiety and depression. Clinical Psychology Review. 1997;17:47–67. doi: 10.1016/s0272-7358(96)00040-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sack WH, Clarke GN, Seely J. Posttraumatic stress disorder across two generations of Cambodian refugees. Journal of American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1995;34:1160–1166. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199509000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saylor CF, editor. Children and disasters. New York: Plenum Press; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Scaramella LV, Sohr-Preston SL, Callahan KL, Mirabile SP. A test of the Family Stress Model on toddler-aged children’s adjustment among Hurricane Katrina impacted and non-impacted low income families. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2008;37:530–541. doi: 10.1080/15374410802148202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheeringa MS, Zeenah CH. Reconsideration of harm’s way: Onsets and comormidity patterns of disorders in preschool children and their care-givers following Hurricane Katrina. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2008;37:508–518. doi: 10.1080/15374410802148178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shelton KK, Frick PJ, Wootton J. Assessment of parenting practices in families of elementary school-age children. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology. 1996;25:317–329. [Google Scholar]

- Spell AW, Kelley ML, Self-Brown S, Davidson KL, Pellegrin A, Palcic J, et al. The moderating effects of maternal psychopathology on children’s adjustment post-Hurricane Katrina. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2008;37:553–563. doi: 10.1080/15374410802148210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinberg AM, Brymer MJ, Decker KB, Pynoos RS. The University of California at Los Angeles Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Reaction Index. Current Psychiatry Reports. 2004;6:96–100. doi: 10.1007/s11920-004-0048-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sytsma SE, Kelley ML, Wymer JH. Development and initial validation of the Child Routines Questionnaire. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment. 2001;23:241–251. [Google Scholar]

- Vernberg EM, La Greca AM, Silverman WK, Prinstein MJ. Prediction of posttraumatic stress symptoms in children after Hurricane Andrew. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1996;105:237–248. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.105.2.237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weems CF, Overstreet S. An ecological-needs-based perspective of adolescent and youth emotional development in the context of disaster: Lessons from Hurricane Katrina. In: Cherry KE, editor. Lifespan perspectives on natural disasters: Coping with Katrina, Rita and other storms. New York: Springer; 2009. pp. 27–44. [Google Scholar]

- Weems CF, Taylor LK, Cannon MF, Ruiz R, Romano DM, Scott BG, et al. Posttraumatic stress, context, and the lingering effects of the Hurricane Katrina disaster among ethnic minority youth. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2010;38:49–56. doi: 10.1007/s10802-009-9352-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zinzow HM, Ruggiero KJ, Resnick H, Saunders B, Kilpatrick D, Smith D. Prevalence and mental health correlates of witnessed parental and community violence in a national sample of adolescents. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2009;50:441–450. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2008.02004.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]