Abstract

Background:

It has been shown that rates of ambulatory follow-up after traumatic injury are not optimal, but the association with insurance status has not been studied.

Aims:

To describe trauma patient characteristics associated with completed follow-up after hospitalization and to compare relative rates of healthcare utilization across payor types.

Setting and Design:

Single institution retrospective cohort study.

Materials and Methods:

We compared patient demographics and healthcare utilization behavior after discharge among trauma patients between April 1, 2005 and April 1, 2010. Our primary outcome of interest was outpatient provider contact within 2 months of discharge.

Statistical Analysis:

Multivariate logistic regression was used to determine the association between characteristics including insurance status and subsequent ambulatory and acute care.

Results:

We reviewed the records of 2906 sequential trauma patients. Patients with Medicaid and those without insurance were significantly less likely to complete scheduled outpatient follow-up within 2 months, compared to those with private insurance (Medicaid, OR 0.67, 95% CI 0.51-0.88; uninsured, OR 0.29, 95% CI 0.23-0.36). Uninsured and Medicaid patients were twice as likely as privately insured patients to visit the Emergency Department (ED) for any reason after discharge (uninsured patients (Medicaid, OR 2.6, 95% CI 1.50-4.53; uninsured, OR 2.10, 94% CI 1.31-3.36).

Conclusion:

We found marked differences between patients in scheduled outpatient follow-up and ED utilization after injury associated with insurance status; however, Medicaid seemed to obviate some of this disparity. Medicaid expansion may improve outpatient follow-up and affect patient outcome disparities after injury.

Keywords: Follow-up, health care costs, re-injury, trauma

INTRODUCTION

Injury is the leading cause of death of all Americans aged 1-35, and one of the leading causes of death and disability in the world. In 2004, traumatic injury accounted for 30 million emergency room visits in the United States and 10% of the nation's total medical expenditures.[1] Longitudinal psychological and medical sequelae are common after trauma, and a significant proportion of traumas are re-injuries to the same individual.[2,3,4,5,6,7]

One of the important components of improving outcomes and decreasing disparities is the ability to detect early post-operative wound infections, poorly healing injuries, and mental health disturbances, such as acute traumatic stress disorder (ATSD) or post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), which may occur post-discharge. For this reason, trauma outpatient follow-up is very important, but compliance can be poor. Clinical factors such as older age and lower severity of injury that predict ambulatory failure to follow-up in trauma patients.[8,9] But socioeconomics and accessibility likely also play a role, as lower neighborhood income determined by census tract and being uninsured or having public insurance have been shown to be associated with higher emergency department (ED) utilization after trauma.[10]

The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (PPACA) seeks to improve health in part through extension of Medicaid insurance benefits to cover an additional 15 million young and middle-aged adults.[11,12] Trauma patients are typically young and frequently uninsured. They may be particularly affected by the planned changes in insurance coverage, and may lead to cost savings by decreasing costly ED visits and unplanned re-admissions, from early detection of potential complications.[13] Social and mental health sequelae may also be addressed earlier and potentially prevent re-injury, depression, or health-related hospitalizations. We aimed to determine the effects of patient insurance status, inpatient consultations with post-discharge care planning, and post-discharge completion of scheduled follow-up on successful ambulatory follow-up and avoidance of ED utilization after trauma, and implications of the PPACA on our results.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

We conducted a retrospective analysis of clinical and administrative data and rates of healthcare utilization among trauma patients. The study was conducted at an urban level I trauma center in Chicago. All trauma patients discharged alive from the trauma service between April 1, 2005 and April 1, 2010 were included in this study. The state of Illinois has a standard set of trauma activation criteria that are based on both mechanism (e.g. motor vehicle collision with speeds greater than 35 mph) and physiology (advanced pregnancy, systolic blood pressure less than 90 mmHg). A typical trauma service is a heterogeneous mix of patients who have suffered gunshot wounds, stab wounds, car crashes, falls, and other injuries, but typically have required surgery or have suffered polytrauma with injuries to several organ systems or parts of the body. Patients who suffered isolated orthopedic or neurologic injuries and admitted to other services were not included in this analysis.

Patients were identified using the hospital trauma registry for this period (n = 3530) and were matched to clinical data stored in the hospital's electronic data warehouse (EDW). The EDW contains patient demographic and clinical information derived from the hospital electronic medical record as well as visit information from the outpatient clinics of the hospital's physician practice group. Using Structured Query Language (SQL) syntax, the EDW was queried to find matching records based on a unique patient identifier consisting of the date of initial Emergency Department (ED) arrival, patient name, date of birth, and medical record number as recorded in the trauma registry. The final match rate was 94.3% (3328/3530).

Approximately 50% of all trauma patients will require post-discharge follow-up, either with trauma surgery, orthopedic surgery, and/or other subspecialties. In order to focus on post-discharge same-hospital utilization, individuals who died prior to discharge and those who resided greater than 60 miles from the index hospital were excluded. We also queried the Social Security Death Index to exclude post-discharge deaths within 60 days, but found no matches. In cases when the same medical record number was associated with multiple visits, only the first visit was included in the dataset. The final dataset contained 2906 records.

Variables drawn from the EDW or the trauma registry and included in the final research dataset were patient age (continuous variable) race, insurance status, Trauma and Injury Severity Score (TRISS),[14,15] admission toxicology and blood alcohol test result, consult and care coordination service use (vascular surgery, neurosurgery, case management, social work, pastoral care), length of stay, discharge functional status (locomotion and expression Functional Independence Measure [FIM] score[16]), and ICD-9 external causes of injury codes (E-codes for falls, motor vehicle collisions, and intentional injury). ICD-9 codes were used because ICD-10 codes have not yet been adopted routinely in the state of Illinois or the rest of the U.S.

The TRISS includes neurologic evaluation through the Glasgow Coma Score, select vital signs, and an anatomic injury survey. To correct for severe negative skewness of the TRISS distribution in this population of live discharges, the score was dichotomized to reflect individuals with an admission score of .99 compared to those with a lower score. Case management services at the study hospital were responsible for coordinating post-discharge medical care, while social work consultation addressed non-medical care needs. Both services resulted from elective consultation. Mechanism of injury was described as a dichotomous variable reflecting intentional and unintentional injury based on E-codes. E-codes for gunshot wounds, stab wounds, and blunt assault were used to identify intentional injury. Death within 3 years of discharge was identified using the Social Security Death Index.

Our primary outcome of interest was outpatient provider contact within 2 months of discharge. The secondary outcomes of interest were 2 month and 1 year Emergency Department use, 2 month and 1 year inpatient re-hospitalization at the study hospital, and 3 year mortality. We also created a dummy variable for the specific post-discharge pathway identifying patients who failed ambulatory follow-up within 2 months but were seen within the ED in this period.

The study protocol was approved by the Northwestern University Institutional Review Board.

Data analysis

We calculated descriptive statistics stratified by completion of 2 month post-discharge physician follow-up to appreciate differences in patient characteristics associated with completed short term follow-up and determine demographic variables to include in the multivariate analysis. Bivariate difference testing was performed on the stratified sample with the Student t test, chi-square test, or Fisher exact test as appropriate. We then compared the relationship between the variables described above and additional outcome variables (12 month outpatient visit, 2 month and 12 month ED visit, and 12 month re-hospitalization).

Using multivariate logistic regression, we then estimated adjusted models for each of these outcomes retaining covariates demonstrating significant associations with 2 month outpatient care and accounting for patient age, sex, race/ethnicity, insurance status, severity of injury (TRISS), length of stay, function at discharge and select inpatient consultation and care coordination services. To estimate severity of illness among patients presenting to the emergency department after discharge, we compared rates of re-hospitalization at 2 months after discharge. We calculated adjusted odds ratios (OR's) and 95% confidence intervals (95% CI). A significance threshold of P < 0.05 was designated for statistical significance. Statistical analysis was performed using SAS 9.3.

RESULTS

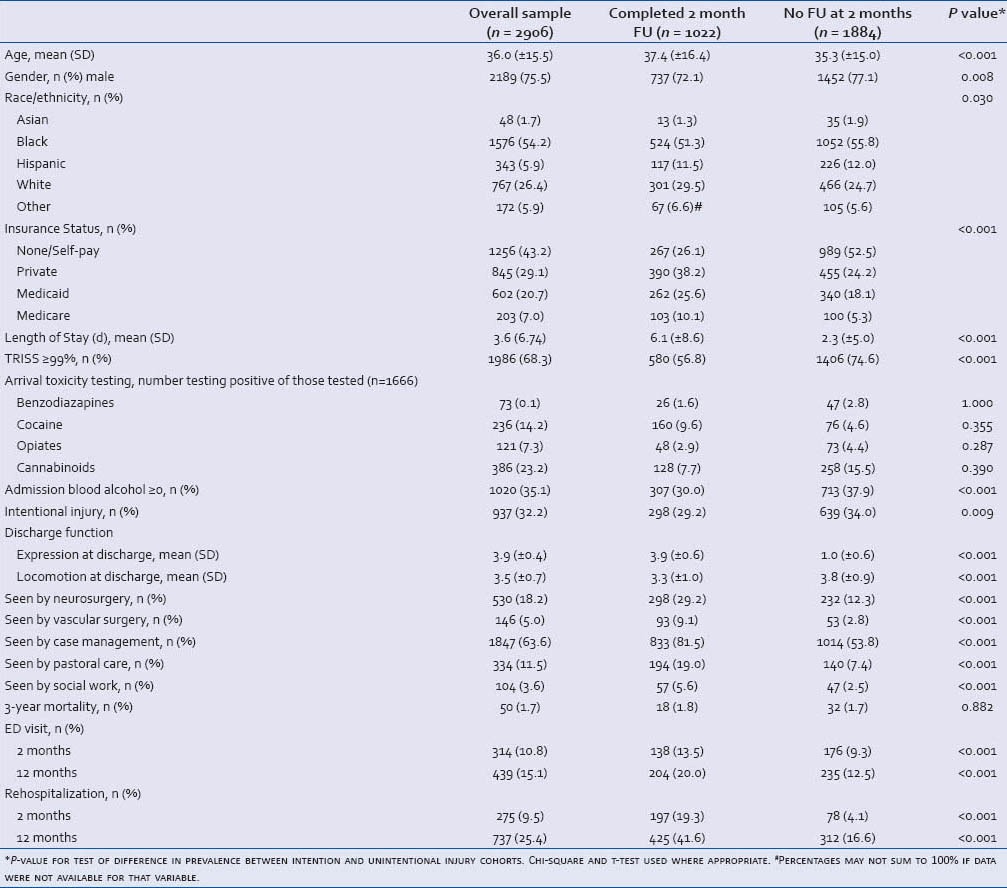

Table 1 presents descriptive characteristics and bivariate comparisons stratified by 2 month follow-up status. In unadjusted analysis, white race, having private insurance, younger age, and female gender were significantly associated with the likelihood of completed 2 month follow-up. However, the values were not dramatic for age (mean age 36 vs. 37.4 years), nor were the percentages very different for gender or race; however, insurance status differed markedly between those who followed up and those who did not, with insured patients being much more likely to complete scheduled follow-up. Unsurprisingly, length of stay and severity of injury also predicted follow-up at 2 months.

Table 1.

Sample characteristics stratified by outpatient physician follow up within 2 months of discharge

Patients who did not complete 2 month follow-up were less likely to receive case management, social work, or pastoral care visits during their hospitalization. Finally, mean FIM on discharge was higher for expression and locomotion among individuals who did not follow-up.

There were no significant differences in the rates of illicit substance positivity on admission toxicology between those who followed up and those who did not in bivariate analysis. As a result, toxicology data was excluded from multivariate models.

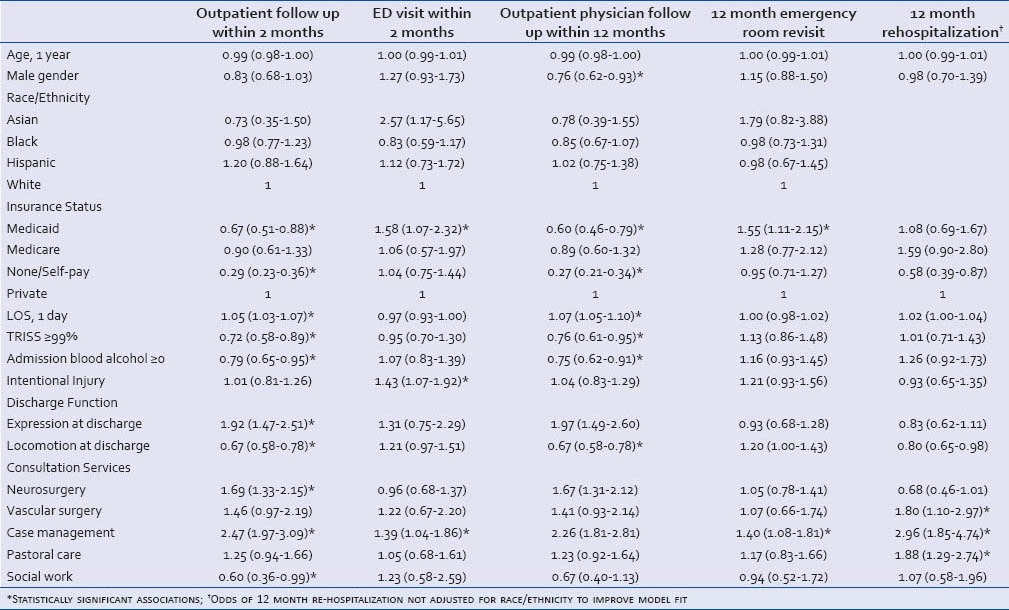

Multivariate regression models were created to determine the independent effects of covariates on primary and secondary outcomes of interest [Table 2]. Covariates included patient age, gender, race, financial status, serum alcohol, mechanism of injury, severity of injury (TRISS), length of stay, function at discharge, consult service evaluation, and discharge planning.

Table 2.

Association between patient characteristics and healthcare utilization, adjusted odds ratios (AOR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI)

Patients with Medicaid or self-pay insurance status were significantly less likely to see an outpatient physician within 2 and 12 months compared to patients with private insurance. Patients with Medicaid were significantly more likely to return for ED evaluation at 2 and 12 months compared to privately insured patients.

At 2 months after discharge, 7.9% (n = 99) of self-pay patients, 6.6% (n = 40) of Medicaid patients, and 3.7% (n = 31) of privately insured patients had sought ED care but not seen an outpatient physician (Adjusted Odds Ratio (AOR)[95% CI], 2.10[1.31-3.36] for uninsured patients compared to privately insured patients, AOR 2.61[1.50-4.53] for Medicaid patients compared to privately insured patients). There was no significant difference in the adjusted odds of this care pattern for individuals with Medicaid and those without insurance (AOR[95% CI] 1.30[0.91-1.85]). Adjusted odds of 2 month re-hospitalization was not significantly different between Medicaid patients and either uninsured (AOR[95% CI] 0.77[0.54-1.10]) or privately insured patients (AOR[95% CI] 1.18[0.81-1.02]).

Adjusting for indicators of injury severity (TRISS) and length of stay, case management evaluation was found to be associated with higher rates of both outpatient physician follow-up and ED use. Twelve month re-hospitalization was significantly less common among individuals without insurance and in individuals with improved locomotion at discharge. Better locomotion at discharge was regularly associated with lower rates of outpatient follow-up at 2 and 12 months and with higher rates of ED revisit at 2 and 12 months.

DISCUSSION

While previous studies have identified associations between insurance status and likelihood of outpatient follow-up or ED revisit,[9,10] we believe our study is the first to analyze a comprehensive database describing post-discharge hospital and ambulatory follow-up data for a population of trauma patients. We looked specifically at a particularly concerning post-discharge utilization pathway in which patients fail to see an outpatient provider but are evaluated in the emergency department in the post-discharge period. This outcome in our well-powered analysis was similar in uninsured patients and Medicaid patients and was twice as common as among privately insured individuals, even when controlling for important potential confounders such as injury mechanism, age, and race. While differences in severity of illness leading to urgent ED revisit could account for these differences, our analysis did adjust for patient clinical characteristics and there was no difference in re-hospitalization across categories. These factors suggesting that higher rates of ED use were associated with ambulatory sensitive conditions.

Our findings must be considered in light of several limitations. First, we are unable to account for care obtained at facilities not captured by our clinical database. Similar to previous work in this area,[10] we only report clinical use from one healthcare system in a major metropolitan center — patients likely sought follow-up care at other centers beyond the site of initial treatment. There are six level I trauma centers and many neighborhood hospitals in the Chicago area; our institution is located downtown and may not be as convenient or as accessible as other hospitals. However, even if Medicaid-covered individuals were receiving ambulatory care at other facilities, it would not completely explain the observed 50% increase in same hospital ED utilization compared to privately insured patients. Second, this data set describes a uniquely American trauma patient population, particularly as it relates to health care financing. Though some of these findings may be applicable to lower SES groups in other countries, this is a limitation of the work.

The isolation of individual trauma centers’ registries is a significant barrier to epidemiologic research on trauma follow-up and, importantly, risk factors for re-injury, which could be overcome through future collaboration. In addition, severity of injury and illness are likely the largest drivers of care utilization after injury. While we included some adjustment for these factors (age, LOS, TRISS, use of neurosurgery and vascular surgery consult services), it is possible that some findings may nonetheless reflect residual confounding. Finally, our cohort is relatively young, with a mean age of 36 and few elderly patients; the influence of Medicare versus Medicaid cannot be assessed with these data.

CONCLUSION

Using a longitudinal database, which allowed for consideration of inpatient and outpatient healthcare utilization after injury, this work indicates that potential gains in health and value through improved access to outpatient services may be limited if this increased access is funded through expansion of Medicaid eligibility. While the ACA includes a two year initial period of payment equity between Medicaid and Medicare, there is reason for concern that in the long term health and savings, gains through increased access to the Medicaid program may be disappointing. Additional multicenter, prospective studies are needed to better define the improvement in healthcare access that is associated with provision of Medicaid to patients with traumatic injury.

Footnotes

Source of Support: This work was supported, in part, by a grant from the Smart Family Foundation.

Conflict of Interest: None of the authors have any conflicts of interest to disclose.

REFERENCES

- 1.CDC Injury Fact Book. Atlanta (GA): Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2006. [Last accessed on 2011 Sep 16]. National Center for Injury Prevention and Control. Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/Injury/publications/FactBook/InjuryBook2006.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kaufmann CR, Branas CC, Brawley ML. A population-based study of trauma recidivism. J Trauma. 1998;45:325–31. doi: 10.1097/00005373-199808000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Weigelt JA, Dryer D, Haley RW. The necessity and efficiency of wound surveillance after discharge. Arch Surg. 1992;127:77–82. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1992.01420010091013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Davidson GH, Hamlat CA, Rivara FP, Koepsell TD, Jurkovich GJ, Arbabi S. Long-term survival of adult trauma patients. JAMA. 2011;305:1001–7. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Holbrook TL, Hoyt DB, Coimbra R, Potenza B, Sise M, Anderson J. High rates of acute stress disorder impact quality-of-life outcomes in injured adolescents: Mechanism and gender predict acute stress disorder risk. J Trauma. 2005;59:1126–30. doi: 10.1097/01.ta.0000196433.61423.f2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Holbrook TL, Hoyt DB, Coimbra R, Potenza B, Sise M, Anderson JP. Long-term posttraumatic stress disorder persists after major trauma in adolescents: New data on risk factors and functional outcome. J Trauma. 2005;58:764–9. doi: 10.1097/01.ta.0000159247.48547.7d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Perencevich EN, Sands KE, Cosgrove SE, Guadagnoli E, Meara E, Platt R. Health and economic impact of surgical site infections diagnosed after hospital discharge. Emerg Infect Dis. 2003;9:196–203. doi: 10.3201/eid0902.020232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gabbe BJ, Simpson PM, Sutherland AM, Williamson OD, Judson R, Kossmann T, et al. Functional measures at discharge: Are they useful predictors of longer term outcomes for trauma registries? Ann Surg. 2008;247:854–9. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181656d1e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Leukhardt WH, Golob JF, McCoy AM, Fadlalla A, Malangoni MA, Claridge JA. Follow-up disparities after trauma: A real problem for outcomes research. Am J Surg. 2010;199:348–53. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2009.09.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ladha KS, Young JH, Ng DK, Efron DT, Haider AH. Factors affecting the likelihood of presentation to the emergency department of trauma patients after discharge. Ann Emerg Med. 2011;58:431–7. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2011.04.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Holahan J, Headen I. Washington, DC: Kaiser Family Foundation, Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured; 2010. [Last accessed on 2010 Aug 16]. Medicaid coverage and spending in health reform: National and State-by-State results for adults at or below 133% FPL, Executive Summary (Report No. 8076-ES) Available from: http://www.kff.org/healthreform/upload/Medicaid-Coverage-and-Spending-in-Health-Reform-National-and-State-By-State-Results-for-Adults-at-or-Below-133-FPL-Executive-Summary. pdf . [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ku L, Jones K, Shin P, Bruen B, Hayes K. The states’ next challenge — securing primary care for expanded Medicaid populations. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:493–5. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1011623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Haider AH, Chang DC, Efron DT, Haut ER, Crandall M, Cornwell EE., III Race and insurance status as risk factors for trauma mortality. Arch Surg. 2008;143:945–9. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.143.10.945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Champion HR, Sacco WJ, Hunt TK. Trauma severity scoring to predict mortality. World J Surg. 1983;7:4–11. doi: 10.1007/BF01655906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Boyd CR, Tolson MA, Copes WS. Evaluating trauma care: The TRISS method. Trauma Score and the Injury Severity Score. J Trauma. 1987;27:370–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Linacre JM, Heinemann AW, Wright BD, Granger CV, Hamilton BB. The structure and stability of the functional independence measure. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1994;75:127–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]