Abstract

Aims:

The aim of this study was to characterize positive blood alcohol among patients injured at work, and to compare the severity of injury and outcome of blood alcohol concentration (BAC) positive and negative patients.

Settings and Design:

A retrospective cohort study was performed at a Level 1 academic trauma center. Patients injured at work between 01/01/07 and 01/01/12 and admitted with positive (BAC+) vs negative (BAC−) blood alcohol were compared using bivariate analysis.

Results:

Out of 823, 319 subjects were tested for BAC (38.8%), of whom 37 were BAC+ (mean 0.151 g/dL, range 0.015-0.371 g/dL). Age (41 years), sex (97.2% men), race, intensive care unit (ICU) and hospital length of stay (LOS), and mortality were similar between groups. Nearly half of BAC+ cases were farming injuries (18, 48.6%): Eight involved livestock, five involved all-terrain vehicles (ATVs), three involved heavy equipment, one fell, and one had a firearm injury. Eight (21.6%) were construction site injuries involving falls from a roof or scaffolding, five (13.5%) were semi-truck collisions, four (10.8%) involved falls from a vehicle in various settings, and two (5.4%) were crush injuries at an oilfield. BAC+ subjects were less likely to be injured in construction sites and oilfields, including vehicle-related falls (2.3 vs 33.9%, P < 0.0001). Over half of BAC+ (n = 20, 54%) subjects were alcohol dependent; three (8.1%) also tested positive for cocaine on admission. No BAC+ subjects were admitted to rehabilitation compared to 33 (11.7%) of BAC− subjects. Workers’ compensation covered a significantly smaller proportion of BAC+ patients (16.2 vs 61.0%, P < 0.0001).

Conclusions:

Alcohol use in the workplace is more prevalent than commonly suspected, especially in farming and other less regulated industries. BAC+ is associated with less insurance coverage, which probably affects resources available for post-discharge rehabilitation and hospital reimbursement.

Keywords: Alcohol use, blood alcohol concentration, trauma, work-related injuries

INTRODUCTION

The consequences of excessive alcohol consumption have been a topic of recent discussion among many state legislatures and administrative agencies in the United States. New recommendations by the National Transportation Safety Board have encouraged states to reduce the legal limit of blood alcohol concentration (BAC) to 0.05% by volume, from its current level of 0.08.[1] These frequently discussed changes are aimed at decreasing the instance of excessive and destructive personal alcohol consumption, which is a key factor in many motor vehicle accident fatalities. In a study published in the Archives of Surgery, 47% of trauma patients tested positive for BAC at the time of admission;[2] while a recent study published in the World Journal of Surgery, only 30.7% of trauma patients who tested positive for BAC upon admission were considered intoxicated by the current legal limit in the state of Texas of BAC ≥ 0.08%.[3]

The effects of alcohol consumption have been well-documented to include a decrease in coordination and balance, as well as diminished perception, attention, and judgment.[4] This increased risk of injury extends to the operation of machinery, use of power tools, and handling of dangerous equipment; tasks that are frequently associated with occupational settings. Under dangerous working conditions, it may be simply assumed by employers or fellow workers that the consumption of alcohol, either before or during the task, should not occur. Routine or random alcohol testing is also the exception rather than the norm at most workplaces, with the exception of highly regulated fields such as the aviation industry where universal testing and a zero tolerance policy are strictly enforced. As a result, there is little documentation available on this phenomenon.

The aim of this study was to characterize the prevalence of positive blood alcohol among patients injured at work, and to compare the severity of injury and outcome of BAC positive and negative patients.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The Texas Tech University Health Sciences Center Institutional Review Board approved this retrospective cohort analysis on the outcomes of patients injured at work between 2007 and 2011 and admitted to our Level 1 Trauma Center. Trauma registry data was used to identify subjects, who were compared on the basis of positive and negative BAC and were examined on the characteristics of the place and mechanism of injury, sex, age, race, mortality, insurance status, injury severity score (ISS), complications, length of stay (LOS), and disposition, which was categorized as full recovery, moderate recovery, severe disability, and death in the trauma registry.

The location where the traumatic injury occurred was divided into four categories: Farm, industry, street, and other. For place of injury, the category of ‘farm’ included any accident that happened on a farm or ranch, while working with farming equipment, livestock, or maintenance associated with farming. ‘Industry’ included all construction site, oilfield, and factory accidents. ‘Street’ accidents included any semi-truck collisions or accidents that occurred with a road maintenance crew. Injury mechanisms were categorized as motor vehicle collisions, falls, penetrating injuries, blunt force trauma, and fire arm injuries.

Subjects were divided into three categories based on their BAC status: Positive (BAC+), negative (BAC−), and untested-BAC. Subjects who were BAC+ or BAC− were included for comparison in this study. If a patient's injuries did not occur on the job, they were excluded from the analysis. In order to obtain detailed information about the type of work that was being done at the time of injury, as well as descriptive information about the injuries that occurred, the admission history and physical examination, initial consult documentation, and the discharge summary were reviewed by a single investigator on all BAC+ and BAC− subjects.

We performed bivariate analysis with equal variances assumed to compare the characteristics of BAC+ to BAC− subjects; Student's two-sided independent samples t-test was used for continuous variables and chi-square for categorical variables, except where the value in any one category was less than 5, in which case Fisher's exact test was used instead. Results with P ≤ 0.05 were considered to be statistically significant. Data for untested-BAC patients was included, but not compared statistically to BAC+ or BAC− patients.

RESULTS

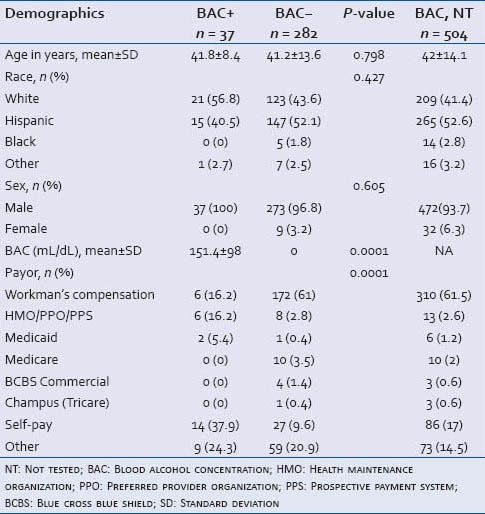

A total of 823 trauma patients sustained work-related injuries during this time period, of whom 504 (61.2%) were not tested for BAC on admission. Baseline characteristics of the subjects are summarized in Table 1. Of those who were tested, 37 (4.5%) were BAC+ and 282 (34.3%) were BAC−. Age (mean 41.8 vs 41.2 years) and sex (100 vs 96.8% male) were similar between BAC+ and BAC− groups. The BAC untested group had similar demographics.

Table 1.

Comparison of patient demographics

The range of BAC for BAC+ patients was 0.015-0.371 g/dL, with a mean of 0.151 g/dL. The highest BAC recorded in this study is equivalent to more than 15 drinks in 1 h for a 150 lb man. Based on the current legal limit of BAC in this state (0.08 g/dL), 25 BAC+ subjects were legally intoxicated (67.6%). Twenty of the BAC+ subjects (54.1%) were estimated to be alcohol-dependent after they admitted to consuming multiple alcoholic beverages a day on screening questionnaire. Additionally, three patients tested positive for cocaine on admission.

Likelihood of BAC testing

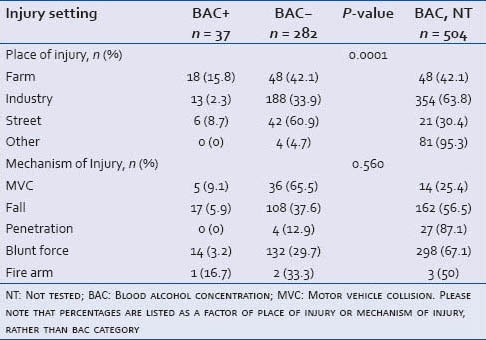

Likelihood of being tested for BAC corresponded strongly with being injured at a farming location (57.9%) or street (69.6%) vs formal industry (36.2%) (P = 0.0275). Injury mechanism involving motor vehicle collision was more likely to lead to testing (74.6%) than fall (43.5%) or blunt force trauma (32.9%) (P = 0.0001).

Injury mechanism and location

The injury mechanism and location characteristics are summarized in Table 2. The two most common causes of traumatic injury for BAC+ subjects were injuries from livestock (n = 8, 21.6%) and falls sustained on construction sites from roofs or scaffolding (n = 8, 21.6%). The second most common causes of injury were all-terrain vehicle (ATV) accidents (n = 5, 13.5%) and semi-truck/motor vehicle collisions (n = 5, 13.5%).

Table 2.

Comparison of injuries

Farming injuries comprised 48.6% of all BAC+ injuries. This includes eight livestock-related injuries, including trampling from bulls (n = 2, 5.4%) and falls from breaking-in horses (n = 6; 16.2%). Five subjects sustained ATV crush injuries (13.5%), two were injured by tractor rollovers (5.4%), and one sustained a hand crush injury from irrigation equipment (2.7%). One subject was injured with a firearm while killing a wild animal (2.7%) and another fell off a ladder while working on a barn (2.7%).

Despite the high overall number of construction site injuries seen at this trauma center, BAC positivity was less frequently associated with injuries occurring in industry, including construction sites, oilfields, and related vehicle falls (2.3 vs 33.9%, P < 0.0001). Of the BAC+ industry injuries, eight occurred as falls from a roof or scaffolding (21.6%), two occurred as crush injuries in an oilfield (5.4%), and three occurred as falls from a vehicle onsite (8.1%). The remaining BAC+ injuries involved semi-truck collisions (n = 5, 13.5%) and a fall from a semi-truck while on route (n = 1, 2.7%).

Payer status

Health insurance status is summarized in Table 1. Significantly more BAC− subjects were covered by Workers’ Compensation insurance than BAC+ (16.2 vs 61.0%, P < 0.0001). The most common status for BAC+ subjects was the designation of self-pay or uninsured (n = 23, 62.2%). The health insurance distribution of the group of patients that were not tested for BAC was similar to the distribution of BAC− patients. Most notably, the majority of untested patients were covered by Workman's Compensation (n = 310, 61.5%).

Six of the BAC+ subjects were covered by Workers’ Compensation despite their positive BAC; only one of those subjects was under the legal limit for intoxication with a BAC of 0.041 g/dL. The average BAC of the remaining five subjects was 0.186 g/dL. Two of these subjects were injured in a semi-truck collision, two fell from scaffolding on a construction site, and one sustained a crush injury to the hand while working in an oilfield.

Outcomes

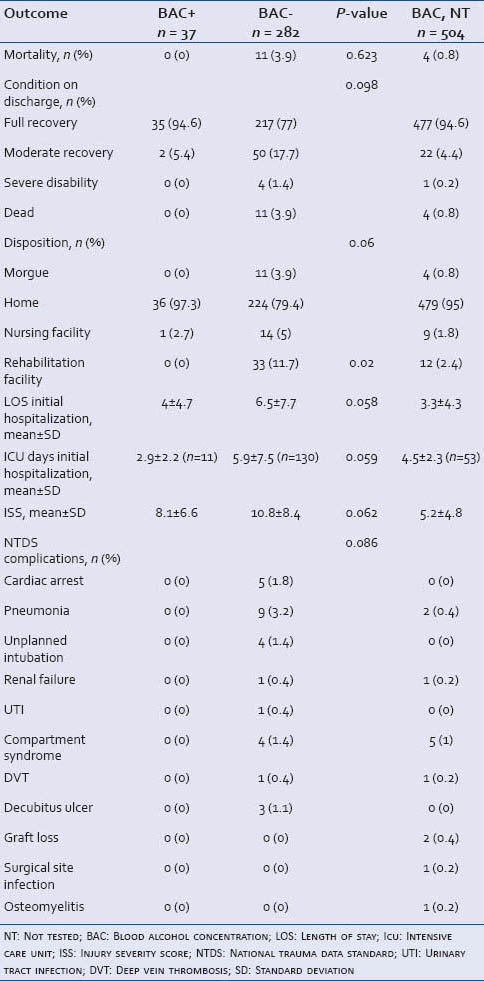

The clinical outcomes are summarized in Table 3. BAC+ subjects had a lower ISS that was nearly statistically significant (8.5 vs 11, P = 0.06). No BAC+ subjects died from their injuries or sustained any National Trauma Data Standard (NTDS) complications. However, eleven BAC- subjects (3.9%) and four untested-BAC patients (0.8%) died from their injuries. Twenty-one BAC− patients (7.4%) sustained one or more NDTS complication(s), compared to no BAC+ patients (P = 0.08). Twelve untested-BAC patients (2.4%) sustained one or more NTDS complication(s). The mean initial hospital LOS was 4 ± 4.7 days for BAC+, 6.5 ± 7.7 days for BAC− subjects, and 3.3 ± 4.3 days for untested-BAC patients. The mean initial intensive care unit (ICU) LOS was 2.9 ± 2.2 days for BAC+ (n = 11), 5.9 ± 7.5 days for BAC− subjects (n = 130), and 4.5 ± 2.3 (n = 53) for untested-BAC patients. Nearly all of the BAC+ (n = 35, 94.6%) and untested-BAC patients (n = 477, 94.6%) made a full recovery on discharge compared to 77.7% of BAC- subjects (n = 217).

Table 3.

Comparison of outcomes

In terms of disposition after discharge, no BAC+ subjects were admitted to a rehabilitation facility, compared to 33 of the BAC− subjects (P = 0.02) and 12 of the untested-BAC patients (2.4%). Of the other BAC− subjects who survived their injuries, 224 were discharged home (79.4%) and 14 went to a nursing facility (5%). Of the untested-BAC patients who survived their injuries, 479 were discharged home (95.0%) and nine went to a nursing facility (1.8%). Only one BAC+ subject was discharged to a nursing facility (2.7%); this patient had a BAC of 0.065 g/dL, within the legal limit in this state.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we sought to investigate the frequency of alcohol use among injured workers and association between clinical outcomes and alcohol positivity. To date, published research about the effects of alcohol consumption on injury has predominately focused on patients who sustained motor vehicle accidents[5] and/or traumatic brain injury.[6] In the case of motor vehicle accidents, the presence of alcohol has been independently correlated with sepsis, spinal fractures, and a longer hospital LOS. However, this same study also noted that high BAC (≥0.08) was associated with increased survival rates.[7] Additionally, traumatic brain injury patients with a high BAC (≥0.23) had a lower percentage of ICU admissions, lower hospital and ICU LOSs, and lower mortality rate in one study.[8] Due to this and similar studies, it has been speculated that positive BAC at the time of traumatic brain injury has a protective affect against permanent brain damage by reducing the neuroinflammatory response to injury.[9] It has also been suggested that inebriation causes an artificial lowering of the Glasgow Coma Scale on admission, resulting in a higher trauma score than is warranted by the actual injury, and thus the perception of better outcomes.[7] However, an association between alcohol consumption at the time of injury and worse short- and long-term survival in trauma patients has also been demonstrated.[7,10] Additionally, it has been suggested that positive BAC in trauma patients is associated with increased resource utilization, due to increased hospital and ICU LOS and increased ICU admissions.[11]

Though alcohol consumption prior to injury may be associated with a protective affect for brain injuries, the social and financial implications of a positive BAC are solely negative. Patients that test positive for alcohol intoxication while claiming a work-related injury are at an extremely high risk for losing Workers’ Compensation insurance.[12] With the loss of insurance, patients are likely to forgo necessary treatment as well as important follow-up and rehabilitation. This situation may result in patients not recovering to their full ability, leading to decreased productivity in the workforce, if they get back to work at all. In this study, BAC+ subjects were significantly less likely to undergo rehabilitation and were more likely to be uninsured, both of which may have been a direct result of alcohol positivity.

Though the presumption is that alcohol consumption should not occur at the work place, patients still arrive with positive BAC at emergency departments with traumatic injuries, claiming work-related accidents. This leads to negative financial and social complications for both the individual and the healthcare system. Based on the Workers’ Compensation code for the state of Texas, “injuries will not be covered if they were the result of the employee's…intoxication from drugs or alcohol…”.[12] At our institution, workers who are covered by Workers’ Compensation usually do not have additional insurance to cover injuries excluded from their coverage; therefore, if their claims are denied by Workers’ Compensation they are considered to be a self-paying/uninsured patient. This has significant financial implications for the healthcare system, implying that the hospital will likely not be reimbursed for any or most of the costs of care.

When a healthcare system is faced with providing a patient with treatment and writing off those expenses, patients may be faced with premature discharge at the expense of their recovery.[13] If insurance entities denied claims to these patients, they may have been discharged early due to lack of funding to continue full treatment. The same may be true for the average ICU time that BAC+ patients spent in the hospital; consciously or unconsciously, there may be pressure within the system to expedite the discharge of patients perceived as being a drain on the system. Another possible explanation may be a higher rate of initial ICU admissions for altered sensorium among BAC+ patients despite a lack of significant injuries, which would then lead to expedient discharge once the patient was sober.

With these significant financial implications in place, another important finding was that more than half of all subjects injured at work were not tested for BAC (n = 504, 61.2%). This finding was especially true for those injured in formal industry, compared to farming and casual labor settings. It is unclear if the lack of testing is based on the assumption that patients injured at work are less likely to be intoxicated, a mere oversight on the part of the ordering physician, or if this represents a conscious or unconscious effort to avoid denial of coverage from an insurance entity.

As mentioned above, BAC+ patients were significantly less likely to be admitted to a nursing facility or rehabilitation facility. A probable contributing factor is that a BAC+ patient is more likely to lack funding for rehabilitation after being denied insurance coverage, although the trend toward reduced severity of BAC+ patient injuries may be partially responsible as well. The importance of rehabilitation for musculoskeletal injuries is widely recognized and can vastly affect how a patient recovers.[14] In the case of patients who are injured at work, if they are unable to recover fully they may not be able to return to the workforce.[15] This would have significant negative social as well as financial implications for the patient. The higher prevalence of alcohol dependence among BAC+ patients is also a negative predictor of recovery. One study concluded that patients with a history of alcohol abuse are likely to have poor rehabilitation progress as well as requiring a more costly rehabilitation effort.[16]

In this study, BAC+ patients in general had less severe injuries than BAC− patients. This finding may be responsible for the trend toward shorter lengths of stay and reduced complication and mortality rate in the BAC+ cohort. It is unclear what the causes are for this reduced severity of injuries among BAC+ patients, but there may be social factors underlying this trend. For example, a coworker, suspecting that a colleague has been drinking but unwilling to report them to a superior, may instead assign the subject a task that puts them at less risk of harming themselves or others. Less formal work environments, such as those noted in this study to have a higher incidence of BAC+ subjects, may lend themselves to this variety of informal “compensation” for a colleague's impairment. In informal working environments, the consumption of alcohol on the job or right before coming on the job may also not be frowned upon as severely as in more regulated environments. It is also possible that the perception of less severe injuries results in a reduced likelihood of BAC testing, as the untested group in this study had a lower ISS than either BAC+ or BAC− subjects, which might skew the results.

There are several limitations of this study. This study was performed retrospectively at a single institution with a large rural population base; therefore these results might not be generalizable across all settings. In addition, the small numbers of BAC+ subjects likely account for the lack of statistical significance in several variables, such as injury severity, LOS, and complication rates, due to inadequately powered analysis. This study does not take into account changes in policy for alcohol screenings that occurred for Level 1 Trauma Centers after 2011 based on a mandate by the American College of Surgeons to screen all trauma patients for alcohol use and dependence. During the time frame of this study, Level 1 Trauma Centers were required to provide 24-h laboratory in-house drug and alcohol screening; however, only victims of motor vehicle collisions who were believed to have been the driver of the vehicle were required by law to have a blood alcohol test drawn upon admission,[17] which explains the higher likelihood of BAC testing in work injuries involving motor vehicles. All analysis for mortality and injuries only considered the initial trauma admission and discharge from the hospital. Therefore, we cannot comment on the long-term complications, disabilities, or recovery of these patients. While we analyzed all information available to us in the medical record, the actual details of the workplace injury are based on subject, and witness report rather than formal workplace incident documentation, which may have provided crucial insight into the mechanisms and causes for injury that were not recorded. Given the social and financial implications of BAC positivity, it is possible that the information documented in the medical record was more subject to bias than usual, which could also affect the accuracy of our findings.

CONCLUSION

Alcohol use is more prevalent than commonly suspected, especially in farming and casual labor settings, although less than half of patients injured in these settings are BAC tested. BAC positivity did not adversely affect clinical outcomes, but was associated with lack of insurance coverage.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The authors wish to acknowledge the assistance of the TTUHSC Clinical Research Institute and the UMC Trauma Services Department.

Footnotes

Source of Support: TTUHSC Clinical Research Institute and the UMC Trauma and Burn Services Department.

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Wald M. New York Times: 2013. States urged to cut limit on alcohol for drivers. http://www.nytimes.com/2013/05/15/us/legal-limitdrunken-driving-safety-board.html . [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rivara FP, Jurkovich GJ, Gurney JG, Seguin D, Fligner CL, Ries R, et al. The magnitude of acute and chronic alcohol abuse in trauma patients. Arch Surg. 1993;128:907–12. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1993.01420200081015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bilello J, McCray V, Davis J, Jackson L, Danos LA. Acute ethanol intoxication and trauma patient: Hemodynamic pitfalls. World J Surg. 2011;35:2149–53. doi: 10.1007/s00268-011-1191-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cherpitel CJ, Bond J, Ye Y, Borges G, Room R, Poznyak V, et al. Multi-level analysis of causal attribution of injury to alcohol and modifying effects: Data from two international emergency room projects. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2006;82:258–68. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2005.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stubig T, Petri M, Zeckey C, Brand S, Muller C, Otte D, et al. Alcohol intoxication in road traffic accidents leads to higher impact speed difference, higher ISS and MAIS, and higher preclinical mortality. Alcohol. 2012;46:681–6. doi: 10.1016/j.alcohol.2012.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shandro JR, Rivara FP, Wang J, Jurkovich GJ, Nathens AB, MacKenzie EJ. Alcohol and risk of mortality in patients with traumatic brain injury. J Trauma. 2009;66:1584–90. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e318182af96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Plurad D, Demetriades D, Gruzinski G, Preston C, Chan L, Gaspard D, et al. Motor vehicle crashes: The association of alcohol consumption with the typer and severity of injury and outcome. J Emerg Med. 2010;38:12–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2007.09.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Berry C, Ley EJ, Margulies DR, Mirocha J, Bukur M, Malinoski D, et al. Correlating the blood alcohol concentration with outcome after traumatic brain injury: Too much is not a bad thing. Am Surg. 2011;77:1416–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Goodman MD, Makley AT, Campion EM, Friend AL, Lentsch AB, Pritts TA. Preinjury alcohol exposure attenuates the neuroinflammatory response to traumatic brain injury. J Surg Res. 2013;184:1053–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2013.04.058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Saleh SS, Szebenyi SE. Resource use of elderly emergency department patients with alcohol-related diagnoses. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2005;29:313–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2005.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Swearingen A, Ghaemmaghami V, Loftus T, Swearingen CJ, Salisbury H, Gerkin RD, et al. Extreme blood alcohol level is associated with increased resource use in trauma patients. The Am Surg. 2010;76:20–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Workers’ Compensation policy. [Last accessed on 2013 July 6]. Available from: http://www.twc.state.tx.us/news/efte/workers_compensation.html .

- 13.Kleppel JB, Lincoln AE, Winston FK. Assessing head-injury survivors of motor vehicle crashes at discharge from trauma care. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2002;81:114–22. doi: 10.1097/00002060-200202000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Micheo W, Baerga L, Miranda G. Basic principles regarding strength, flexibility, and stability exercises. PM R. 2012;4:805–11. doi: 10.1016/j.pmrj.2012.09.583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lindahl M, Hvalsoe B, Poulsen J, Langberg H. Quality in rehabilitation after a working age person has sustained a fracture: Partnership contributes to continuity. Work. 2013;44:177–89. doi: 10.3233/WOR-121498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bombardier CH, Stroud MW, Esselman PC, Rimmele CT. Do preinjury alcohol problems predict poorer rehabilitation progress in persons with spinal cord injury? Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2004;85:1488–92. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2003.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Joint Committee on Administrative Rules. Administrative Rule. Title 77. Ch. 1. Subchapter f. Section 515.2030. 2001 [Google Scholar]