Abstract

Purpose:

Trauma dogma dictates that the physiologic response to injury is blunted by beta-blockers and other cardiac medications. We sought to determine how the pre-injury cardiac medication profile influences admission physiology and post-injury outcomes.

Materials and Methods:

Trauma patients older than 45 evaluated at our center were retrospectively studied. Pre-injury medication profiles were evaluated for angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors / angiotensin receptor blockers (ACE-I/ARB), beta-blockers, calcium channel blockers, amiodarone, or a combination of the above mentioned agents. Multivariable logistic regression or linear regression analyses were used to identify relationships between pre-injury medications, vital signs on presentation, post-injury complications, length of hospital stay, and mortality.

Results:

Records of 645 patients were reviewed (mean age 62.9 years, Injury Severity Score >10, 23%). Our analysis demonstrated no effect on systolic and diastolic blood pressures from beta-blocker, ACE-I/ARB, calcium channel blocker, and amiodarone use. The triple therapy (combined beta-blocker, calcium channel blocker, and ACE-I/ARB) patient group had significantly lower heart rate than the no cardiac medication group. No other groups were statistically different for heart rate, systolic, and diastolic blood pressure.

Conclusions:

Pre-injury use of cardiac medication lowered heart rate in the triple-agent group (beta-blocker, calcium channel blocker, and ACEi/ARB) when compared the no cardiac medication group. While most combinations of cardiac medications do not blunt the hyperdynamic response in trauma cases, patients on combined beta-blocker, calcium channel blocker, and ACE-I/ARB therapy had higher mortality and more in-hospital complications despite only mild attenuation of the hyperdynamic response.

Keywords: Beta-blockers, cardiac medication, geriatric trauma, hyperdynamic response

INTRODUCTION

Geriatric trauma patients represent the fastest growing population segment seen in U. S. trauma centers.[1] This trend is partly due to greater longevity and the increasingly active lifestyle among members of this group compared with historical cohorts.[2] Trauma patients age 65 years and above are hospitalized twice as often as those in any other age group, accounting for one quarter of all trauma admissions.[3] Moreover, an increasing number of comorbidities in this population may also influence overall trauma outcomes.[3] Elderly patients frequently have cardiovascular comorbidities and often require multiple medications for management. These medications have the potential to modulate both their vital signs and clinical outcomes.[4] Except for the effects of anticoagulants, only limited data is available regarding the influence of specific cardiovascular medications on outcome after traumatic injury.[5]

Physiologic criteria such as heart rate (HR), blood pressure (BP), respiratory rate, level of consciousness, and temperature are easy to obtain but are limited in their ability to quantify the physiologic insult after injury. In general, the larger the deviation of these parameters from normal, the greater the physiologic insult from the trauma. Highly abnormal vital signs have been correlated with mortality.[6] These data are based almost exclusively on observations from young, previously healthy individuals. Given the complexities associated with hemodynamic changes of aging, many questions remain regarding the impact of hypotension and hemodynamic instability among older trauma patients, especially in the context of cardiovascular comorbidities and pre-injury cardiac medication use.

Recent literature suggests that beta blocker administration after certain traumatic injuries may improve outcomes.[7,8] However, this data is limited and there are no dedicated studies to assess the effect of pre-injury beta blockers and other cardiac medication use in the older trauma population. Traditional teaching suggests that the physiologic response to injury may be “blunted” by cardiac medication use, possibly resulting in undesirable modulation of cardiac output, reduction in tissue perfusion, and blunting of the normal “on-demand” sympathetic physiologic response. The current study sought to determine how the pre-injury cardiac medication profile influences admission physiology.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

Study design and settings

The study was approved by The Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center Institutional Review Board. We conducted a retrospective review of patients admitted to our Level I trauma center utilizing our trauma database and other records. We identified 645 trauma patients older than 45 years who were evaluated between January 2006 and July 2008. Patients who died in the trauma resuscitation room upon arrival were excluded. Preadmission medications were identified by review of the nursing admission assessment, physician admission notes, and pharmacy medication reconciliation documents. Pre-injury medication profiles were evaluated for angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors/angiotensin receptor blockers, beta-blockers, calcium channel blockers, amiodarone and any combination of the above therapies. Pre-existing conditions were evaluated and categorized. Cardiac complications tracked in this study included myocardial infarction and major arrhythmias. Admission vital signs were compared between patients based on their cardiac medication profile.

Statistical analysis

The primary goal was to generate point estimates of the various clinical outcomes and their associated 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) across different cardiac medication regimens. No inferential test comparing a specific clinical outcome across medications was run—therefore no p-values are presented, as this study was not powered to show equivalence. Instead the 95% CI are compared to suggest if a clinical outcome is either equivalent or not across medications. After clinical outcomes were estimated we used multivariable linear or logistic regression methods to generate adjusted point estimates of mortality, cardiac complications, and hospital length of stay along their associated 95% CI. In all regression models, we adjusted for the patient's gender, age, and injury severity score (ISS). We estimated the proportion and its 95% CI using an exact binomial method for mortality and cardiac complications. All analyses were performed using SPSS 21 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, New York).

RESULTS

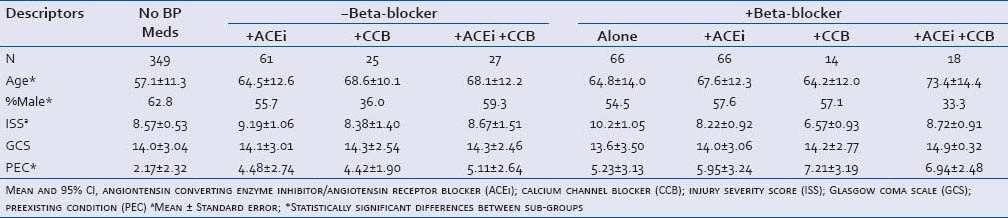

A total of 645 patient charts were reviewed with 296 on at least one cardiac medication prior to trauma and 349 on none. Table 1 contains demographic information as well as data for severity of injury, Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) and preexisting conditions (PEC), as determined at the time of the admission across cardiac medications. GCS and PEC were not statistically different across medication use as all of the confidence intervals overlapped. There were no statistically significant differences when comparing age between groups but the patients on cardiac medication tended to be older. Patients on calcium channel blockers alone and triple therapy were more likely to be female. The severity of injury was significantly lower in the amiodarone group (not shown), as well as the beta-blocker/calcium channel blocker double-therapy patients, when compared to the no cardiac medication patients. Finally, patients on any cardiac medication tended to have more PEC's than patients on no cardiac medications.

Table 1.

Demographic, injury characteristics and preexisting medical conditions of the study population by cardiac medication

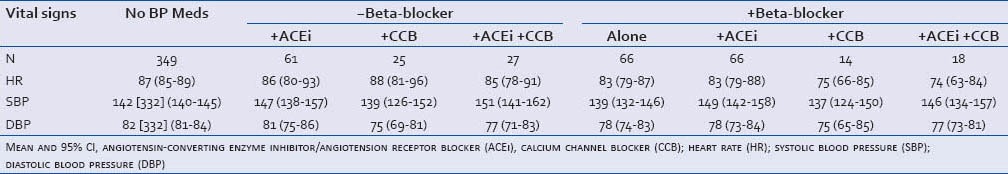

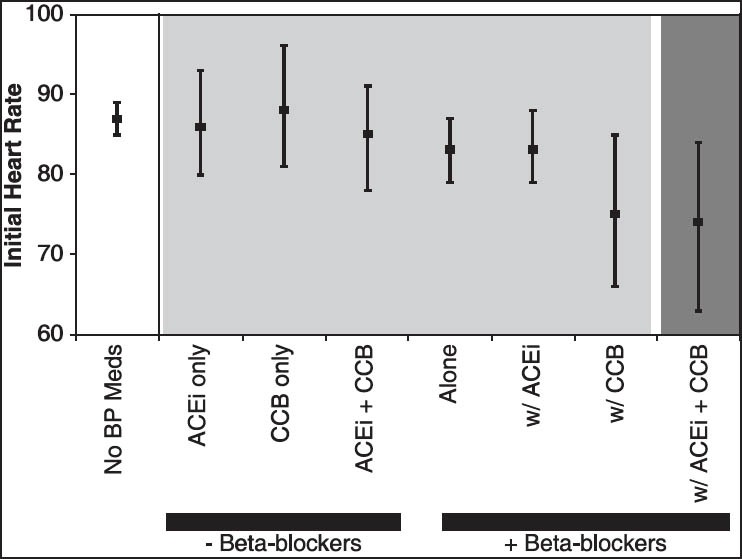

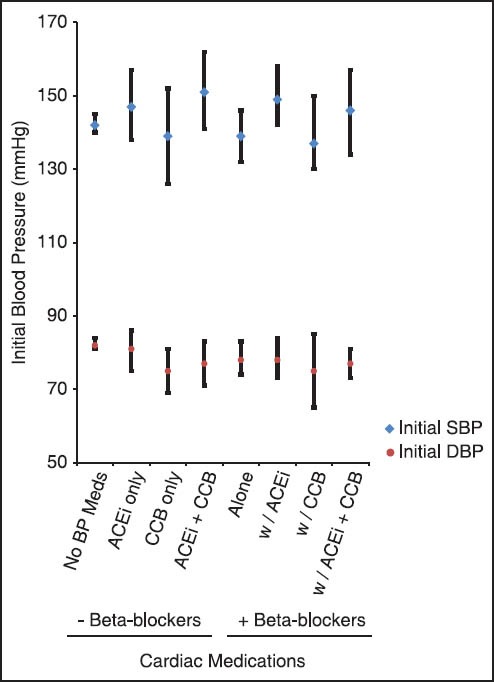

The heart rate was found to be significantly lower in patients taking the three drug combination of beta-blocker, ACE-I/ARB, and calcium channel blocker medications concurrently [Table 2, Figure 1]. Additionally, patients on beta-blocker and calcium channel blockers tended to have a lower heart rate, despite lacking statistical significance. For all the other medication groups, there were no significant differences in heart rate when compared to the non-medicated patients. Blood pressure (both systolic and diastolic) on arrival showed no significant variability between medication groups [all 95% CI overlapped, Table 2, Figure 2].

Table 2.

Mean initial heart rate (HR), systolic (SBP) and diastolic blood pressure (DBP) at time of presentation by cardiac medication

Figure 1.

Initial heart rate on admission by cardiac medication Mean and the 95% CI, beta blocker (BB), angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor/angiotensin II receptor blocker (ACEi), calcium channel blocker (CCB)

Figure 2.

Initial systolic and diastolic blood pressure on admission by cardiac medication

Mean and 95% CI. beta blockers (BB), angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors/angiontensin II receptor blockers (ACEi), calcium channel blocker (CCB), systolic blood pressure (SBP), diastolic blood pressure (DBP). Light gray background indicates no significant differences in heart rate in comparison to ‘No BP Meds’ group. Dark grey background indicates statistically significant difference between ‘+Beta-blocker w/ ACEi + CCB’ and ‘No BP Meds’ groups

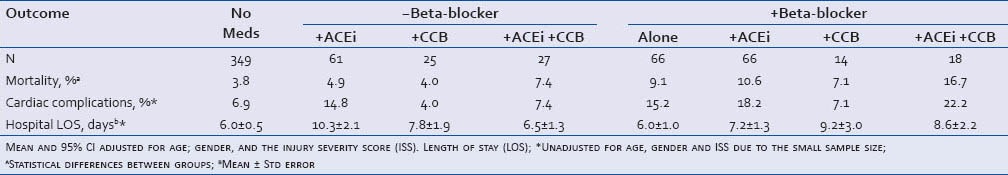

In the study sample, the beta-blocker alone and the triple therapy group had significantly higher mortality than the no blood pressure medication group [Table 3].

Table 3.

Mortality, cardiac complications and length of hospital stay

The group using amiodarone demonstrated a trend toward increased mortality, cardiac complications, and longer hospitalization when compared to the no medication group (not shown). The amiodarone group (n = 19) had an average age of 72.5 years and was 52% male. Injury severity scores were significantly lower in the amiodarone group (6.9) in comparison to the no blood pressure medication group (9.0). The GCS (14.9) and the number of pre-existing conditions (5.8) were not significantly different from the no blood pressure medications group. Comparing the ER presenting vitals, there was no significant difference between the amiodarone (HR – 85, 73-97; SBP – 135, 114-157; DBP – 78, 68-87) and the no blood pressure medication group. However, the incidence of mortality and cardiac complications was higher (5.3% and 21.1% respectively). The hospital LOS did not differ significantly, 5.4 days (vs. 6.0 days for no cardiac medication group). There were not enough patients in the amiodarone group to perform an analysis of the impact of various combinations of medications that included amiodarone. For this reason, amiodarone is not included in our tables and figures.

The triple cardiac therapy group appeared to have the worst clinical outcomes according to our measures: 16.7% mortality, a 22.2% cardiac complication rate, and an average hospital length of stay of 8.6 days (compared to the 3.8% mortality, 6.9% cardiac complications, and 6.0 average hospital LOS for the no cardiac medication group). However, the relative significance of the effects is confounded by the small sample size of the triple therapy group (n = 18).

DISCUSSION

Our study was intended to answer the question of whether pre-injury cardiac medications and the patient's hemodynamic response to trauma are inter-related. Based on our results, the concern that patients using cardiac medications pre-injury will not mount the appropriate initial physiologic response following traumatic injury appears to be unfounded. Our study demonstrates that HR, with the exception of triple-agent cardiac medication use, is unaffected by pre-injury cardiac medications. Furthermore, blood pressure, both systolic and diastolic, did not differ significantly across all groups. This suggests sufficient physiologic compensation in the triple-therapy group despite a lower heart rate. However, measures of clinical outcomes (i. e. mortality, cardiac complications, and hospital LOS) differed significantly, regardless of the lack of significant change in vital signs at emergency department presentation.

Previous analyses demonstrate that even a minor deviation from normal HR upon presentation is associated with a dramatic increase in the probability of subsequent death in the elderly population.[6] Our results suggest that, for the most part, there is a poor association between vitals upon ED presentation and clinical outcomes (ie. mortality, incidence of cardiac complications and hospital length of stay) but, certain combinations of blood pressure medication appears to have increased mortality and warrant further study.

Outcomes of trauma patients taking beta blockers at the time of their injury are mixed, with some studies showing improved outcomes and others showing increased mortality.[9] Neideen et al., looked at the pre-injury beta blocker association with mortality in elderly trauma patients and found that trauma patients without a head injury taking beta blockers had an increased odds ratio for having a fatal outcome.[10] These conclusions were based on the assumption that elderly trauma patients taking beta-blockers might appear to be less injured because beta blockade may mask the shock state or decrease the body's natural response to trauma. This could result in an extended period of under-resuscitation. At the same time it has been postulated that outcomes in trauma patients may be improved due to beta blocker use resulting in decreased myocardial oxygen demand and improved oxygen utilization.[9] Cotton et al., and Arbabi et al., have published data that beta-blockers are beneficial in trauma patients with head injury, possibly by reducing metabolic rates in brain tissue.[7,8]

Havens et al., looked at the pre-injury beta-blocker usage in trauma patients and concluded that beta blockade is associated with a lower presenting heart rate, more bradycardia and less tachycardia, but no difference in mortality or ability to achieve a normal heart rate after resuscitation.[9] Our study shows that patients taking beta-blockers have higher mortality than patients not taking any blood pressure medications in the absence of significant physiologic change (i. e. vitals). Due to the constraints of the study design, it is not possible to draw conclusions on beta-blocker administration as a problem versus an indicator of increased risk.

In-hospital mortality after trauma is not only related to the injury itself but also to comorbidities and medications the patient is taking. We have shown in our study that patients on beta-blockers, alone and in combination with other cardiac medications, tend to have an increased number of comorbidities and subsequently have a higher mortality rate. This is in concordance with several other studies that demonstrated a relationship between preexisting conditions and mortality in trauma patients that is age-dependent.[11] This offers evidence that the presence of underlying disease and multiple cardiac medications should be considered in decisions to triage and transfer patients to trauma centers.

Pre-injury amiodarone use was associated with high mortality, cardiac complications, and length of stay. Amiodarone users also had the highest number of comorbid conditions. The cardiovascular, pulmonary, endocrine, and other numerous effects of amiodarone may play a role in these poor outcomes, but amiodarone is typically selected in patients with more severe phenotypes of disease not amenable to other treatments.

It is important to consider our results as hypothesis-generating, with the need for further elaboration. An obvious shortcoming of our study is its retrospective nature and that it represents a single institution's experience. Pre-injury cardiac medication use was determined by the medical record, relying primarily on three sources: the physician, nurse and pharmacy documentation. Other limitations/variables not included in our model that may impact outcome included mechanism of injury, resuscitation volumes, substance abuse, advanced directives and withdrawal of care by family.

CONCLUSIONS

This study shows that single- or double-agent combinations of cardiac-specific medications have no significant effect on the hyperdynamic response in older trauma patients. There was a decrease in the heart rate of patients on three cardiac medications but no significant alteration of the blood pressure. Despite the minimal change in vitals, there were significant differences in the clinical outcomes between patients on certain pre-injury cardiac medications when compared to the no cardiac medication group. Certain combinations of pre-injury cardiac medications appear to be associated with worse clinical outcomes. This suggests the need for future investigation of pre-injury medications and trauma outcomes.

Ethics statement

Our human study has been approved by the appropriate ethics committee (Ohio State University IRB) and has therefore been performed in accordance with the ethical standards laid down in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The authors would like to acknowledge Gary Phillips, M. A. S. in the OSU Center for Biostatistics for his statistical contributions.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil.

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Mann NC, Cahn RM, Mullins RJ, Brand DM, Jurkovich GJ. Survival among injured geriatric patients during construction of a statewide trauma system. J Trauma. 2001;50:1111–6. doi: 10.1097/00005373-200106000-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jacobs DG. Special considerations in geriatric injury. Curr Opin Crit Care. 2003;9:535–9. doi: 10.1097/00075198-200312000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McGwin G, Jr, MacLennan PA, Fife JB, Davis GG, Rue LW., 3rd Preexisting conditions and mortality in older trauma patients. J Trauma. 2004;56:1291–6. doi: 10.1097/01.ta.0000089354.02065.d0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Evans DC, Cook CH, Christy JM, Murphy CV, Gerlach AT, Eiferman D, et al. Comorbidity-polypharmacy scoring facilitates outcome prediction in older trauma patients. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2012;60:1465–70. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2012.04075.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Evans DC, Gerlach AT, Christy JM, Jarvis AM, Lindsey DE, Whitmill ML, et al. Pre-injury polypharmacy as a predictor of outcomes in trauma patients. Int J Crit Illn Inj Sci. 2011;1:104–9. doi: 10.4103/2229-5151.84793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Heffernan DS, Thakkar RK, Monaghan SF, Ravindran R, Adams CA, Jr, Kozloff MS, et al. Normal presenting vital signs are unreliable in geriatric blunt trauma victims. J Trauma. 2010;69:813–20. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e3181f41af8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Arbabi S, Campion EM, Hemmila MR, Barker M, Dimo M, Ahrns KS, et al. Beta-blocker use is associated with improved outcomes in adult trauma patients. J Trauma. 2007;62:56–61. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e31802d972b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cotton BA, Snodgrass KB, Fleming SB, Carpenter RO, Kemp CD, Arbogast PG, et al. Beta-blocker exposure is associated with improved survival after severe traumatic brain injury. J Trauma. 2007;62:26–33. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e31802d02d0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Havens JM, Carter C, Gu X, Rogers SO., Jr Preinjury beta blocker usage does not affect the heart rate response to initial trauma resuscitation. Int J Surg. 2012;10:518–21. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2012.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Neideen T, Lam M, Brasel KJ. Preinjury beta blockers are associated with increased mortality in geriatric trauma patients. J Trauma. 2008;65:1016–20. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e3181897eac. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Morris JA, Jr, MacKenzie EJ, Edelstein SL. The effect of preexisting conditions on mortality in trauma patients. JAMA. 1990;263:1942–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]