Abstract

Traumatic events after a road traffic accident (RTA) can be physical and/or psychological. Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is one of the major psychological conditions which affect accident victims. Psychological issues may not be addressed in the emergency department(ED) immediately. There have been reports about a mismatch between the timely referrals from ED to occupational or primary care services for these issues. If left untreated, there may be adverse effects on quality of life (QOL) and work productivity. Hospital expenses, loss of income, and loss of work could create a never ending cycle for financial difficulties and burden in trauma victims. The aim of our review is to address the magnitude of PTSD in post-RTA hospitalized patients in Indian subcontinent population. We also attempted to emphasis on few management guidelines. A comprehensive search was conducted on major databases with Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) term ‘PTSD or post-traumatic stress’ and Emergency department and vehicle or road or highway or automobile or car or truck or trauma and India. Out of 120 studies, a total of six studies met our inclusion criteria and were included in the review. Our interpretation of the problem is that; hospital expenditure due to trauma, time away from work during hospitalization, and reduction in work performance, are three major hits that can lead RTA victims to financial crisis. Proposed management guidelines are; establish a coordinated triage, implementing a screening tool in the ED, and provide psychological counseling.

Keywords: Guidelines, hospitalization, India, magnitude, post-traumatic stress disorder, PTSD, road traffic accidents, RTA

INTRODUCTION

According to World Health Organization (WHO) report (2004), road traffic accidents (RTAs) are currently ranked ninth for global disease burden, and it is projected to move to the third position by 2020.[1]

India accounts for nearly 10% of the world's RTA.[2] An accident is reported every 3 min and a death every 10 min on Indian roads.[3] In 2009; 422,000 RTAs and 127,000 road traffic fatalities were reported in India.[4] Psychiatric complications associated with trauma have been reported to be globally increasing and RTA survivors do develop symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD).[5] When Joshipura et al., did a survey on 50 institutions across the country; they reported that there was a mismatch at rehabilitation facilities, where majority of them (76%) had physiotherapy services available, but only one-third had psychological counseling and occupational therapy.[3] India is expected to have a large burden of RTA-related PTSD, with an estimated economic loss of 3% of gross domestic product (GDP).[1] For the obvious reasons mentioned above, special attention is needed to reduce the psychological repercussions of RTA, which can potentially have a significant impact on productivity and on quality of life (QOL) of the victims.

With growing industrialization, road transit plays an important role in meeting the daily needs of people in a rapidly growing country like India. Overburdened road infrastructure and failure to follow traffic rules are leading to RTA, and the numbers are rising at an alarming pace.[2] Management of trauma is a multidimensional and extremely challenging task. The RTA patients are attended by emergency room (ER) physicians, orthopedic or trauma surgeons trained in managing only the physical injuries. Psychological issues which are not immediately evident end up going unrecognized, resulting in a significant impact on the victims, victim's families, and ultimately society as a whole.[6]

Psychological concerns, if not addressed appropriately, may lead to acute or chronic mental health conditions.[7] According to the latest version of Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM)-V, PTSD results from actual or threatened death, serious injury, or sexual violence. Symptoms may also manifest by intrusion symptoms like nightmares, flashbacks, and/or recurrent and intrusive distressing memories of the traumatic event. Avoidance of reminders of the trauma, negative changes in mood, cognition associated with trauma (e.g., dissociative amnesia, loss of interest, and feelings of detachment), and significant change in arousal and reactivity after trauma (unprovoked anger outburst, hypervigilance, and exaggerated startle response).[8] Immediate repercussions of acute psychological trauma include emotions like intense fear, helplessness, or horror. However, despite the high prevalence of these emotions in the immediate post-trauma period, their predictability about onset of PTSD is low and as a result of this, they were not included in DSM-V.[7,9]

The primary aim of this review was to assess what is known about PTSD in post-RTA patients requiring hospitalization in Indian subcontinent. Additionally, this review addresses the social and economic consequences of PTSD in victims of RTA.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

A search was conducted on Medline, Embase, and Scopus with Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) term Stress Disorders, Post-Traumatic, and ‘PTSD or post-traumatic stress disorder’ and Emergency department and vehicle or road or highway or automobile or car or truck or trauma and India (both as a MeSH term and a keyword).

Studies with no RTA, no PTSD, neither PTSD or RTA, no abstract are excluded from this review.

RESULTS

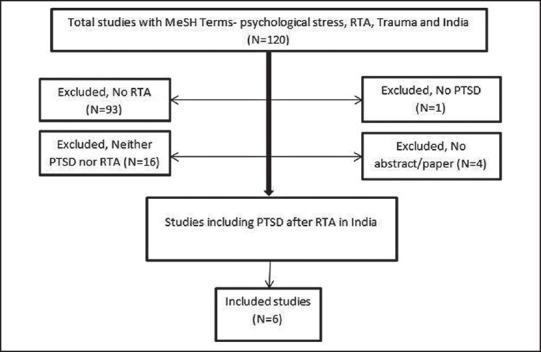

We found 120 studies that were relevant to our inclusion criteria, of which six studies were included in the review [Figure 1]. Relevant articles and other pertinent references are included in this review. Institutional review board (IRB) approval was waived because no patient chart review or data were included.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of included-excluded studies

MeSH = Medical Subject Headings, RTA = Road traffic accident, PTSD = Posttraumatic stress disorder

DISCUSSION

Why does PTSD develop after trauma?

Witnessing or experiencing a life-threatening trauma may lead to two types of injuries: “Visible physical” and “invisible emotional” injuries. The “visible physical” injuries are handled by physicians immediately as they are well-trained in doing that, but the “invisible emotional” injuries are often overlooked resulting in their persistence.

PTSD prediction

Blanchard et al., reported an association between PTSD severity, heart rate (HR), and diastolic blood pressure (DBP) recorded in the emergency department (ED) setting.[10] Patients who met criteria for PTSD at 13 months after RTA are likely to have lower HRs and lower DBP in the ED, compared to those who did not develop PTSD. Identification of patients and families at risk for PTSD symptoms using a screening tool presented some limitations, but overall acceptability of the process is high for both ED staff and patients. So, introducing a new screening tool or validating existing ones in adult ED may help in early identification and prevention of late sequelae of post-trauma effects.[11]

Screening, identification, treatment, and follow-up with psychiatric counseling are needed. Skodol et al.,[12] have recommended a two-step approach to early identification of PTSD. In the first step, self-reporting measures are administered and if the predetermined cutoff score is exceeded, a more extensive and diagnostic evaluation is recommended. This helps in early identification of the affected individuals and assisting with appropriate referrals to effective RTA-PTSD treatment. Overall, this approach affords the opportunity for clinicians to allocate the services where they are needed most. Use of psychometric measures like PCL (PTSD Check List) is very helpful in this regard. The PCL is a 17-item self-report measure reflecting DSM-IV symptoms of PTSD.[13]

Mass Transit: Buses in rural India and buses and metro trains are the most common use of mass transit in urban India. We focused on RTAs. Noncompliance with transit rules by majority of bus companies only adds to the increase in RTA and may add to the worries for PTSD incidence. We fail to find any article pertinent to PTSD and mass transit in India.

Epidemiology

PTSD is one of the major psychological conditions, which affect the accident victims.[14] Depending on the nature and magnitude of the traumatic event, the prevalence rates of PTSD in victims have been reported to range from 5 to 50%.[15] Among those who develop PTSD, 68% are in the younger age group of 20-39 years.[5]

The independent predictors of development of PTSD are: Female gender, active marital status for males and ex-marital status for women, preexisting psychiatric conditions like major depression and anxiety disorder, substance abuse, lower socioeconomic status (SES), family history of anxiety or antisocial behavior, previous exposure to trauma, and lack of post-exposure social support and adjustment.[16,17]

The limitations in work and social life, and lower social support have been suggested as the main predictive factors for development of PTSD after RTA at 12 months.[18]

Knowledge gap

In India, there are no coordinated efforts at national or state level for a robust and coordinated trauma system. Consequently, the fatal accident rate (expressed per kilometer of travel) is estimated to be sevenfold worse when compared to other advanced countries.[19] Inability to reach the trauma center on time due to topographical issues and inefficient modes of transportation from rural areas exacerbate the situation.[3]

The impact of PTSD, ranked by WHO as overall age-standardized disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) are 56 in India and 58 in other developed nations.[20] In developed nations, the psychological impact after RTA has been studied extensively. Data is lacking in India.[2]

Availability of psychiatric services is not well-established in trauma units in India.[1] The psychological consequences of RTA in India have been reported to be increasing and ranges between 8.5 and 39%.[1] Singh et al., described failure to use indicator lights, speed limit restrictions, and improper road signs as the most common reasons for RTAs. Despite the efforts to improve road conditions, the burden of increasing population and unwillingness to follow basic traffic rules are causing an increase in RTA and most of the victims are at risk of developing PTSD.[4]

How could these administrative deficits be corrected and how do they impact the different aspects of an individual's life from medical, social, and psychological perspective?

Significance

QOL

QOL can be determined from one's living conditions, the ability to reach expected living goals, and includes physical health, psychological status, level of independent living, social relationships, and interaction with the environment.[21]

The effect of trauma on QOL is an important matter. PTSD symptom profiles were compared in three types of civilian trauma: Sexual assault, motor vehicle accident, and sudden loss of loved ones. The pattern of PTSD symptoms and severity of disease varied among these groups. Sexual assault demonstrated higher severity on most symptoms than RTA and sudden loss of loved ones.[22] There is limited knowledge on post-RTA QOL of the victims. Findings have suggested that PTSD may be an important predictor of health-related QOL.[23] The PTSD-related factors, which influence the QOL, can be modifiable or non-modifiable. Modifiable factors include pain, depression, psychological stress, and severity of PTSD; while non-modifiable ones are age; gender; and mechanism, type, and severity of injury. The severity of PTSD symptoms bears a direct relationship with the impact on physical and mental QOL.[24] Michaels et al., suggested that PTSD was an important factor influencing the ability to return to normal premorbid level of functioning.[25]

Matthews showed that the RTA victims who developed PTSD, were subjectively more distressed, had decreased performance at school, and had difficulty with homemaking and relationships with family or friends; in comparison to non-PTSD RTA victims.[26] PTSD-RTA victims had more difficulties with interpersonal relations and distressed subjectively compared to non-PTSD RTA victims.

Financial

Factors like financial hardships after the RTA have been reported to be independently associated with PTSD symptoms.[27] This issue becomes rather important in developing countries like India, where health insurance coverage is limited.[1]

Kar et al. described the relationship between SES and PTSD in children and adolescents one year after a super cyclone. Their findings suggest that the PTSD rates were higher in the middle SES followed by lower and the least in those who were below poverty line.[28] The economic difficulties arising from post-trauma unemployment may add to their ongoing woes. The Longitudinal Study conducted in Australia concluded that the relation between the compensation and health outcomes is somewhat complex in trauma patients.[29]

Chan et al. showed that the healthcare cost and economic loss associated with RTAs is enormous. The economic losses accounted by untreated RTA-related PTSD cases is higher as compared to treated RTA-related PTSD patients and RTA victims who did not develop PTSD.[30]

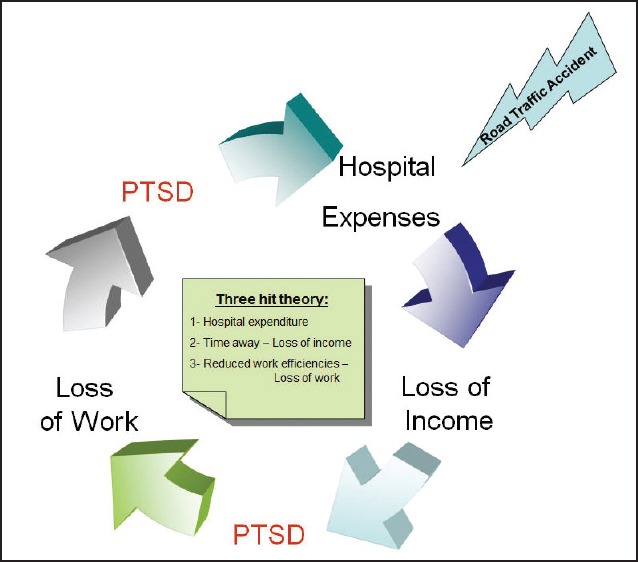

We submit the three hit theory

Post-RTA and hospital discharge patients might not be able to work due to trauma-related pain for weeks to months. Inability to work and prolonged stay at home may add to their ongoing stress. Lack of disability insurance and inadequate financial support may lead to further stress in victims. We believe that:

Hospital expenditure due to trauma,

Time away from work during hospitalization and recovery which results in loss of income, and

Reduction in work performance due to PTSD which may result in loss of work, are three major hits that a RTA victim experiences in the post-trauma period and these hits are major factors leading to financial crisis [Figure 2].

Figure 2.

‘Three Hit Theory’ for financial issues post road traffic accidents

Inadequate financial aid and delayed or insufficient insurance claims may in turn aggravate the PTSD symptoms by preventing appropriate treatment and by exacerbating the stress. We strongly believe that this theory would pave the way for establishing a policy for those who develop PTSD after RTA.[31]

Productivity

Matthews had shown that survivors of the RTA with PTSD have decreased work potential in comparison to their non-PTSD counterparts. Work potential profile (WPP) is a self-report measure of 177 items specifically designed to objectively assess the major personal characteristics, dispositions, ability, and skills that affect professional productivity. WPP is intended to describe current functioning of patients. Some of the barriers to work resumption that Matthews identified were ineffective time management, high levels of depression and anxiety, and overconcern about physical injuries.[26] They also demonstrated that early referral to occupational rehabilitation programs may help overcome these barriers to work resumption and stimulate internal motivation to return to work.

Much of this high-end technology is unavailable to victims in a developing country. It is challenging to organize a continuity care trauma system in India and even if the continuity of care is present in metropolitan cities like Delhi National Capital Region (NCR), they lack coordinated efforts.[3,32] To overcome this issue, investing into a continuity care trauma system integrated with developed technology, would be an effective long-term plan.

Administrative components

Despite an association of PTSD with high morbidity,[2] a systematic approach to deal with the consequences related to PTSD is lacking. ‘Network orientation’ is an interesting term used by Clapp and Beck[33] network orientation scale is a 20-item measure designed to assess attitudes, beliefs, and expectations regarding the usefulness of social support networks during times of need, that is, statements reflecting positive and negative attitudes toward support utilization.[33] Network orientation may be an important factor in understanding the interface between interpersonal interactions and post-trauma pathology.

Need for guidelines: Taking into account, the impact of PTSD on various aspects of the victim's life, most effective treatment strategy is an integrated, multidisciplinary approach. The steps for such an approach would involve a balance between the clinical team, psychiatric team, administrative team, government agencies, and national healthcare policy makers.[31]

The findings of this review should be of interest to the policy makers and healthcare administrators. Given the high incidence of PTSD among RTA survivors, we believe that implementing these guidelines in this vulnerable population can be of great help.

In Summary

Why so many RTA?

Overburdened road infrastructure

Inadequate traffic rules

Failure to follow traffic rules

Insufficient law enforcement mechanism

Why so much PTSD?

Sudden impact of trauma

Severity of trauma

Inadequate psychological care in the trauma units

Post-trauma life

Delayed insurance claims

Financial issues

Interventions:

Clinical approach

Administrative solutions

Patient family education

Insurance coverage

Management guidelines

Establish a coordinated triage for prehospital transfer, psychological care in the trauma units, and early recognition of PTSD to facilitate an appropriate referral.

Implement a screening tool in the ED, to identify patients and their families, who are at increased risk for PTSD.

Make psychological counseling available at all the trauma centers and the hospitals dealing with RTA victims.

Use ‘work potential profile’ scale in assessing the productivity of post-RTA PTSD patients.

Establish a national health care policy to provide a financial support to post-RTA PTSD patients.

Increase the awareness of PTSD and its consequences in all the Indian states using public media.

Although RTAs are commonly encountered at most hospitals, the psychological consequences of trauma are often overlooked. The government, the medical facilities, and the society must recognize it as a public health problem and enforce strong measures to manage it.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

All authors contributed to the manuscript equally, we would like to acknowledge and appreciate help in literature search by Ms. Ann Farrell from Mayo Clinic Libraries.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil.

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Joshipura MK. Trauma care in India: Current scenario. World J Surg. 2008;32:1613–7. doi: 10.1007/s00268-008-9634-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Seethalakshmi R, Dhavale HS, Gawande S, Dewan M. Psychiatric morbidity following motor vehicle crashes: A pilot study from India. J Psychiatr Pract. 2006;12:415–8. doi: 10.1097/00131746-200611000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Joshipura MK, Shah HS, Patel PR, Divatia PA, Desai PM. Trauma care systems in India. Injury. 2003;34:686–92. doi: 10.1016/s0020-1383(03)00163-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Singh A, Bhardwaj A, Pathak R, Ahluwalia SK. An epidemiological study of road traffic accident cases at a tertiary care hospital in rural Haryana. Indian J Community Health. 2011;23:53–5. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ongecha-Owuor FA, Kathuku DM, Othieno CJ, Ndetei DM. Post traumatic stress disorder among motor vehicle accident survivors attending the orthopaedic and trauma clinic at Kenyatta National Hospital, Nairobi. East Afr Med J. 2004;81:362–6. doi: 10.4314/eamj.v81i7.9192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Breslau N, Kessler RC, Chilcoat HD, Schultz LR, Davis GC, Andreski P. Trauma and posttraumatic stress disorder in the community: The 1996 Detroit Area Survey of Trauma. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1998;55:626–32. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.55.7.626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Blanchard EB, Hickling EJ, Taylor AE, Loos W. Psychiatric morbidity associated with motor vehicle accidents. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1995;183:495–504. doi: 10.1097/00005053-199508000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.American Psychiatric Association. 5th ed. Arlington: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2013. DSM-5. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Friedman MJ, Resick PA, Bryant RA, Brewin CR. Considering PTSD for DSM-5. Depress Anxiety. 2011;28:750–69. doi: 10.1002/da.20767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Blanchard EB, Hickling EJ, Galovski T, Veazey C. Emergency room vital signs and PTSD in a treatment seeking sample of motor vehicle accident survivors. J Trauma Stress. 2002;15:199–204. doi: 10.1023/A:1015299126858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ward-Begnoche WL, Aitken ME, Liggin R, Mullins SH, Kassam-Adams N, Marks A, et al. Emergency department screening for risk for post-traumatic stress disorder among injured children. Inj Prev. 2006;12:323–6. doi: 10.1136/ip.2006.011965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Skodol AE, Schwartz S, Dohrenwend BP, Levav I, Shrout PE, Reiff M. PTSD symptoms and comorbid mental disorders in Israeli war veterans. Br J Psychiatry. 1996;169:717–25. doi: 10.1192/bjp.169.6.717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Blanchard EB, Jones-Alexander J, Buckley TC, Forneris CA. Psychometric properties of the PTSD Checklist (PCL) Behav Res Ther. 1996;34:669–73. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(96)00033-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mayou R, Tyndel S, Bryant B. Long-term outcome of motor vehicle accident injury. Psychosom Med. 1997;59:578–84. doi: 10.1097/00006842-199711000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mohta M, Sethi AK, Tyagi A, Mohta A. Psychological care in trauma patients. Injury. 2003;34:17–25. doi: 10.1016/s0020-1383(02)00377-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wilcox HC, Storr CL, Breslau N. Posttraumatic stress disorder and suicide attempts in a community sample of urban american young adults. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2009;66:305–11. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2008.557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ursano RJ, Fullerton CS, Epstein RS, Crowley B, Kao TC, Vance K, et al. Acute and chronic posttraumatic stress disorder in motor vehicle accident victims. Am J Psychiatry. 1999;156:589–95. doi: 10.1176/ajp.156.4.589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yasan A, Guzel A, Tamam Y, Ozkan M. Predictive factors for acute stress disorder and posttraumatic stress disorder after motor vehicle accidents. Psychopathology. 2009;42:236–41. doi: 10.1159/000218521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wegman F. Road accidents: worldwide a problem that can be tackled successfully! AIPCR. 1996 Publication No. 13.01.B. [Google Scholar]

- 20.WHO. Mortality and burden of disease Estimates for WHO member states: Persons, all ages. 2004 [Google Scholar]

- 21.Frank-Stromborg M. Selecting an instrument to measure quality of life. Oncol Nurs Forum. 1984;11:88–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kelley LP, Weathers FW, McDevitt-Murphy ME, Eakin DE, Flood AM. A comparison of PTSD symptom patterns in three types of civilian trauma. J Trauma Stress. 2009;22:227–35. doi: 10.1002/jts.20406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Landolt MA, Vollrath ME, Gnehm HE, Sennhauser FH. Post-traumatic stress impacts on quality of life in children after road traffic accidents: Prospective study. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2009;43:746–53. doi: 10.1080/00048670903001919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brasel KJ, Deroon-Cassini T, Bradley CT. Injury severity and quality of life: Whose perspective is important? J Trauma. 2010;68:263–8. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e3181caa58f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Michaels AJ, Michaels CE, Moon CH, Smith JS, Zimmerman MA, Taheri PA, et al. Posttraumatic stress disorder after injury: Impact on general health outcome and early risk assessment. J Trauma. 1999;47:460–6. doi: 10.1097/00005373-199909000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Matthews LR. Work potential of road accident survivors with post-traumatic stress disorder. Behav Res Ther. 2005;43:475–83. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2004.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Khati I, Hours M, Charnay P, Chossegros L, Tardy H, Nhac-Vu HT, et al. Quality of life one year after a road accident: Results from the adult ESPARR cohort. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2013;74:301–11. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e318270d967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kar N, Mohapatra PK, Nayak KC, Pattanaik P, Swain SP, Kar HC. Post-traumatic stress disorder in children and adolescents one year after a super-cyclone in Orissa, India: Exploring cross-cultural validity and vulnerability factors. BMC Psychiatry. 2007;7:8. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-7-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.O’Donnell ML, Creamer MC, McFarlane AC, Silove D, Bryant RA. Does access to compensation have an impact on recovery outcomes after injury? Med J Aust. 2010;192:328–33. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2010.tb03532.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chan AO, Medicine M, Air TM, McFarlane AC. Posttraumatic stress disorder and its impact on the economic and health costs of motor vehicle accidents in South australia. J Clin Psychiatry. 2003;64:175–81. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v64n0210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jeavons S. Long-term needs of motor vehicle accident victims: Are they being met? Aust Health Rev. 2001;24:128–35. doi: 10.1071/ah010128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Joshipura M. Guidelines for essential trauma care: progress in India. World J Surg. 2006;30:930–3. doi: 10.1007/s00268-005-0765-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Clapp JD, Gayle Beck J. Understanding the relationship between PTSD and social support: the role of negative network orientation. Behav Res Ther. 2009;47:237–44. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2008.12.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]