Abstract

Objective

It is widely known that cigarette use and depressive symptoms co-occur during adolescence and young adulthood and that there are gender differences in smoking initiation, progression, and co-occurrence with other drug use. Given that females have an earlier onset of depressive symptoms while males have an earlier onset of cigarette use, this study explored the possible bidirectional development of cigarette use and depressive symptoms by gender across the transition from adolescence to young adulthood. Gender differences in the stability and crossed effects of depressive symptoms and cigarette smoking during the transition to young adulthood, controlling for other known risk factors, were examined using a nationally representative longitudinal sample.

Methods

A bivariate auto-regressive multi-group structural equation model examined the longitudinal stability and crossed relationships between a latent construct of depressive symptoms and cigarette smoking over four waves of data. Data for this study came from four waves of participants (N=6,501) from the National Longitudinal Survey of Adolescent Health. At each of four waves, participants completed a battery of measures including questions on depressive symptoms and an ordinal measure of number of cigarettes smoked per day.

Results

The best fitting bivariate autoregressive models were gender-specific, included both crossed and parallel associations between depressive symptoms and cigarette use during the transition to adulthood, and controlled for wave-specific parental smoking, alcohol use, and number of friends who smoke. For females, greater depressive symptoms at each wave, except the first one, were associated with greater subsequent cigarette use. There were bidirectional associations between depressive symptoms and cigarette use only for females during young adulthood, but not for males.

Conclusions

The development of depressive symptoms and cigarette use from adolescence and into young adulthood follows similar patterns for males and females. Controlling for the correlation and stability between initial levels of depressive symptoms and cigarette use from adolescence into young adulthood, there remains a crossed association between cigarette use and depressive symptoms specific for females during young adulthood. The findings suggest that prevention interventions focused on mental health should include warnings that cigarette use may exacerbate depressive symptoms.

Keywords: gender differences, longitudinal, depressive symptoms, cigarettes smoked per day, adolescence, young adulthood, emerging adulthood, auto regressive model, comorbidity

Adolescent cigarette use continues to be a risk factor for the progression to heavier cigarette use (Rose, Dierker, & Donny, 2010), the onset of nicotine dependence (Breslau, Fenn, & Peterson, 1993), and other health-related problems (Dierker, Selya, Piasecki, Rose, & Mermelstein, 2013; Kandel, Davies, Karus, & Yamaguchi, 1986). Consistently, studies report a co-occurrence between cigarette use and depressive symptoms (Dierker, Avenevoli, Merikangas, Flaherty, & Stolar, 2001) and cigarette use during adolescence may be a risk factor for the onset of depressive symptoms (Benjet, Wagner, Borges, & Medina-Mora, 2004). Early work in this area found higher rates of depression among individuals who were regular smokers (Glassman et al., 1990). Longitudinal studies have suggested that frequent cigarette use during adolescence increases the odds of developing major depression during young adulthood (Brook, Cohen, & Brook, 1998), and that among individuals not experiencing major depression or drug dependence during adolescence, frequent use of cigarettes was associated with the onset of major depression during early adulthood (Brown, Lewinsohn, Seeley, & Wagner, 1996).

In recent years increased focus has been placed on understanding depressive symptoms, rather than clinical diagnoses of depression, as risk factors for cigarette use. This focus is supported by findings that indicate that depressive symptoms are important in the pathway to developing major depressive disorder (Pine, Cohen, Gurley, Brook, & Ma, 1998). Indeed, smokers with subthreshold levels of depression are more likely than smokers without any depressive symptoms to continue smoking (Weinberger & McKee, 2012). However, some work has reported a decrease in cigarette use among adolescents with high levels of depressive symptoms (Fischer, Najman, Williams, & Clavarino, 2012). A possible reason for the inconsistent finding may be that few studies have examined the bidirectional associations between depressive symptoms and cigarette use.

Gender Differences

It is well established that male adolescents begin smoking earlier (Okoli, Greaves, & Fagyas, 2013) and experience a higher prevalence of experimental smoking than females (Harrell, Bangdiwala, Deng, Webb, & Bradley, 1998; Ng, Freeman, Fleming, & et al., 2014). During early adolescence, however, more rapid increases in cigarette use are found among females than males (Gabrhelik et al., 2012; Sweeting, Jackson, & Haw, 2011).

Higher rates of depressive symptoms among females have been widely known to first appear in adolescence (Zahn-Waxler, Shirtcliff, & Marceau, 2008; Cohen et al., 1993). Females use emotional coping to deal with stressors (Nolen-Hoeksema, 2012) and although males’ cigarette use onset is earlier, it has been suggested that females turn to cigarettes to suppress the experience of emotions (Fucito, Juliano, & Toll, 2010). Thus, the longitudinal association between depressive symptoms and cigarette use may differ by gender.

Other Substance Use

Nationally representative estimates suggest that about 10% to 15% of adolescents and 35% to 45% of young adults report concurrent use of alcohol and cigarettes in the past year (Anthony & Echeagaray-Wagner, 2000). Adolescents who use cigarettes report daily use of other drugs such as marijuana and alcohol compared to adolescents who do not smoke (Duhig, Cavallo, McKee, George, & Krishnan-Sarin, 2005). The concurrent use of marijuana and alcohol predict higher levels of nicotine addiction (Bonilha et al., 2013). Further, young adults who are light smokers are more likely to smoke while having a drink and to smoke a greater number of cigarettes while drinking than young adults who are heavier smokers (Jackson, Colby, & Sher, 2010; Jackson, Sher, & Schulenberg, 2005).

Additionally, individuals who use cigarettes and alcohol are at increased risk for depression (Epstein, Induni, & Wilson, 2009). Increases in depressive symptoms are associated with monthly use of cigarettes and alcohol among young female adolescents, but only monthly alcohol use among young male adolescents is associated with symptoms of depression (Kubik, Lytle, Birnbaum, Murray, & Perry, 2003). Cigarette use continues to be a risk factor for the depressive symptoms, even when controlling for the use of other substances (Brown, Lewinsohn, Seeley, & Wagner, 1996), suggesting that cigarette use may contribute a specific risk factor to the onset of depressive symptoms. In relation to depression, individuals who use only cigarettes experience higher depressive symptoms than those who use cigarettes concurrently with other substances (Bonn-Miller, Zvolensky, & Johnson, 2010). Thus, the association between cigarette use and depressive symptoms is often exacerbated by the use of other substances.

In addition, several characteristics of the adolescent familial and social environments are known to make contributions to adolescent cigarette use and depression. These are discussed next.

Parental smoking

Considerable work has suggested that parental use of cigarettes influences adolescents’ early initiation of cigarette use (Chassin, Presson, Pitts, & Sherman, 2000; Flay et al., 1994) and decreased cessation among established smokers (Chassin, Presson, Rose, & Sherman, 1996). Recent studies have found that a strong predictor of adolescent cigarette use is whether parents are active regular smokers and whether both parents smoke (Gilman et al., 2009).

Friends who smoke

Adolescents’ peers and friends are significant sources of influence on adolescent cigarette use (Kobus, 2003) and having more friends who smoke increase the odds that adolescents will engage in moderate to heavy cigarette use (Goodman & Capitman, 2000). Further, adolescents who spend time in and around social networks with higher smoking prevalence are more likely to use cigarettes (Ennett et al., 2006).

Income

The way in which income is associated with adolescent cigarette use is less clear. Some studies suggest that low levels of family income increase the risk of adolescent cigarette use (Hanson & Chen, 2007; Stanton, Oei, & Silva, 1994). Other studies report a positive relationship between income, in particular having access to discretionary income (Hong, Rice, & Johnson, 2011), and cigarette use (Ben Lakhdar, Cauchie, Vaillant, & Wolff, 2012). Further, the effect of income on adolescent cigarette use may not be limited to the adolescents’ family and personal income, but aspects of the broader community's income may also play a role in the regular smoking among this age group (Mistry et al., 2011).

Some previous studies have examined how these two constructs influence each other (e.g., depressive symptoms) by controlling for concurrent or previous levels of the other construct (e.g., cigarette use) (Fischer et al., 2012; Low et al., 2012; Mickens et al., 2011). The exact unfolding of the co-occurrence between depressive symptoms and cigarette use during the transition from adolescence to adulthood may involve bidirectional effects (Bares & Andrade, 2012; Leung, Gartner, Hall, Lucke, & Dobson, 2012). Accounting for the development of each construct longitudinally and simultaneously in one model may provide insights into how each problem behavior influences the other and doing so is possible by building recursive structural equation models (Kline, 2011). Given previous findings on gender differences in the development of depressive symptoms (Zahn-Waxler et al., 2008) and cigarette use (Okoli et al., 2013), this study's main hypothesis was that depressive symptoms would lead to greater levels of cigarette use for females but to a lesser degree for males. Thus, it was expected that depressive symptoms for males would have a weaker influence on cigarette use than for females across time. The present study examined how males and females differ in the association between depressive symptoms and number of cigarettes consumed per day from adolescence to young adulthood after controlling for known correlates, risk factors, and for the stability of each construct over time.

METHODS

Sample and Participants

The data for this study came from participants in the National Longitudinal Survey of Adolescent Health (Add Health), a nationally representative, probability-based sample of adolescents in the United States who, during the 1994-95 school year, were enrolled in grades 7-12 (http://www.cpc.unc.edu/projects/addhealth). The design of the study and the details regarding data collection are available in previous publications (Harris et al., 2003; Resnick et al., 1997). Following the baseline assessment that occurred in the 1994-95 school year, participants were followed three additional times. The second assessment occurred one year after the first (1995-1996), while the third assessment was undertaken 5 years after the second assessment (2000-2001). The fourth, and most recent, assessment occurred six years after the third assessment (2006-2007). After a full and complete discussion about the study, Add Health participants provided written informed consent prior to participating in any study activities. The University of North Carolina School of Public Health Institutional Review Board approved and, monitored the study.

Data from the four assessments, which spanned 12 years between adolescence and young adulthood, were used for this study. The analytic sample included participants who smoked at any of the four assessments in the Add Health survey.

Assessments and Measures

Cigarettes per day

Each participant reported on the number of cigarettes smoked per day in the previous 30 days at each wave of data collection. In the first, second and fourth assessments in the Add Health survey, participants were asked to report on the number of cigarettes that they smoked per day in the previous month. In the third wave of the assessments, however, participants were instead presented with an ordinal set of response options to indicate the cigarettes they smoked per day in the previous month. To create a more parallel measure of cigarettes per day across all of the waves, the original cigarettes per day variable measured at the first, second, and fourth waves was recoded for this study. The resulting variable at each wave was an ordinal variable where 0 indicated “No cigarettes per day”, 1 “Between 1 and 10 cigarettes per day”, 2 “Between 11 and 20 cigarettes per day, and 3 “More than 21 cigarettes per day”. Participants who had not smoked in the previous 30 days or who reported never smoking were included as smoking 0 cigarettes in the analyses. Table 1 presents the percent of participants by wave who fell into the four categorical response options of cigarette use.

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics of Study Participants (N = 6,501)

| Wave 1 (n=6,501) | Wave 2 (n=4,737) | Wave 3 (n=4,799) | Wave 4 (n=5,026) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| M (SD) | M (SD) | M (SD) | M (SD) | |

| Age | 16.03 (1.77) | 16.63 (1.59) | 22.23 (1.87) | 29.01 (1.78) |

| Income | -- | -- | $7,827.80 (12,784) | -- |

| CES-D (short form) | 9.07 (2.76) | 4.21 (4.42) | 4.88 (3.94) | 5.59 (4.11) |

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | |

| Female | 3,314 (52.0%) | 2,486 (53%) | 2,605 (54.3%) | 2,729 (54.30%) |

| Parental Smoking | 2,235 (35.1%) | -- | -- | -- |

| Peer Smoking | -- | -- | -- | |

| No friends | 3,517 (55.2%) | 2,387 (50.4%) | -- | -- |

| One friend | 1,292 (20.3%) | 1,037 (21.9%) | -- | -- |

| Two friends | 772 (12.1%) | 607 (12.8%) | -- | -- |

| Three or more friends | 788 (12.4%) | 702 (14.8%) | -- | -- |

| Cigarettes smoked (per day) | ||||

| Non-smoker | 4,798 (75 .3%) | 3,254 (68.7%) | 3,292 (68.6%) | 3,206 (63.8%) |

| Less than 10 | 1,229 (19.3%) | 1,179 (24.9%) | 791 (16.5%) | 1,150 (22.9%) |

| Between 11 and 20 | 282 (4.4%) | 251 (5.3%) | 537 (11.2%) | 562 (11.2%) |

| 21 or more | 59 (0.9%) | 56 (1.2%) | 177 (3.7%) | 105 (2.1%) |

Note. CES-D = Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale. Not all variables were assessed at all waves of data collection.

Depressive symptoms

Depressive symptoms were assessed in the Add Health survey using the short version of the Center for Epidemiological Studies-Depression scale (Radloff, 1977, 1991). Participants were asked to indicate how often in the previous week they experienced different emotional states on a 4-point scale ranging from 0=Never or rarely to 3=Most of the time for each of the 9 items. Some of the items include “I felt everything I did was an effort” and “I was bothered by things that usually do not bother me”. The full set of items have been published elsewhere (Andresen, Malmgren, Carter, & Patrick, 1994). Due to the positive wording of four of the CES-D items, (“I felt happy”, “I enjoyed life”, “I felt hopeful about the future”, and “I felt as good as other people”), they were reversed coded. The reliabilities for the depression items at each wave were 0.79 (Wave 1), 0.80 (Wave 2), 0.81 (Wave 3), and 0.81 (Wave 4). For descriptive purposes, Table 1 presents the means and standard deviations of each wave of the CES-D Short Form, calculated from all of the items at each wave.

The covariates used in the analyses included adolescent self-reports of age at the time of the baseline survey (Wave 1), number of friends who smoke measured at Waves 1 and 2, parental smoking (available only at Wave 1), and income (available only at Wave 3). Due to the design of the Add Health survey, not all of the covariates were available in all four of the waves. Table 1 lists descriptive statistics for the study variables by wave.

Parental smoking

In two separate questions, participants reported whether their mother or father had ever smoked. A binary variable was created to indicate whether their mother or father did not smoke (coded as 0) or whether both parents smoked (coded as 1).

Number of friends who smoke

Participants indicated how many of their best friends smoke at least 1 cigarette a day. This was an ordinal variable that ranged from 0 (“None”) to 3 (“Three of my best friends”.)

Income

During the Wave 3 assessment, participants were asked to report on the total annual income they received from wages. This variable was entered as a continuous variable.

Analysis Plan

The first step of the analyses began by subjecting the items of the depressive symptom scale at each wave to a confirmatory factor analysis. Second, upon confirming the structure of the depressive symptoms scale, a latent construct of depressive items measuring symptoms was constructed at each wave for the entire sample and separately by gender (Model 1). A measurement model with loadings that were equated by gender (Model 2) was run and compared to Model 1. Several bivariate auto regressive models were then tested beginning with a simple parallel model in which the latent construct of depressive symptoms was allowed to influence subsequent measures of the same construct and the ordered categorical indicator of cigarettes used per day was allowed to influence cigarette use at subsequent waves (Model 3). A second model (Model 4) was run equating the loadings of the stability paths in each gender and compared to Model 3. In a step-wise fashion, paths were then added between depressive symptoms to cigarette use and from cigarette use to depressive symptoms (Model 5). Then, the crossed paths were equated by gender (Model 6) and compared to a model were the paths were freely estimated (Model 5) to determine the presence of gender differences in the loadings. Lastly, covariates were added to the gender-specific models with stability and crossed paths (Model 7). Model fit indices (Root Mean Square Error of Approximation, RMSEA; Comparative Fit Index, CFI; and Tucker Lewis Index, TLI) were examined for each model and are presented in Table 3 (Kline, 2011). The chi-square difference test for nested models was used to compare model fit and presented in Table 3. The analyses were conducted in Mplus, Version 7 (Muthén & Muthén, 1998-2012).

Table 3.

Testing Structure of CES-D Depressive Symptoms by Wave

| Model | Description | n | RMSEA [90% CI] | CFI | TLI | χ2 (df), p-level | Models tested |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Measurement - free loadings by gender | Female = 3,355 | 0.041 [0.041 - 0.042] | 0.932 | 0.932 | ||

| Male = 3,146 | |||||||

| 2 | Measurement - equate loadings by gender | Female = 3,355 | 0.040 [0.039 - 0.041] | 0.935 | 0.936 | 110.401 (28), p<0.0001 | 2 v 1 |

| Male = 3,146 | |||||||

| 3 | Stability paths - free loadings by gender | Female = 3,355 | 0.037 [0.036 - 0.038] | 0.922 | 0.921 | ||

| Male = 3,146 | |||||||

| 4 | Stability paths - equate loadings by gender | Female = 3,355 | 0.037 [0.036 - 0.038] | 0.922 | 0.921 | 16.840 (6), p<0.01 | 4 v 3 |

| Male = 3,146 | |||||||

| 5 | Cross paths - free loadings by gender | Female = 3,355 | 0.038 [0.037 - 0.038] | 0.92 | 0.918 | ||

| Male = 3,146 | |||||||

| 6 | Cross paths - equate loadings by gender | Female = 3,355 | 0.037 [0.037 - 0.038] | 0.92 | 0.919 | 1.402 (2), p=0.4960 | 6 v 5 |

| Male = 3,146 | |||||||

| 7 | Final model with covariates | Female = 3,355 | 0.030 [0.029 - 0.030] | 0.944 | 0.942 | ||

| Male = 3,146 |

Note. CES-D = Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale; RMSEA = Root Mean Square Error of Approximation; CFI = Comparative Fit Index; TLI = Tucker Lewis Index; CI = confidence interval.

RESULTS

The analytic sample (N=6,501) included participants who had data on all of the four waves. The average age of the sample at the first assessment was 16.01 (SD=1.77) and over 50% of the sample was female across all four assessments, see Table 1. Over a third of the sample had begun the study with one or both parents who had ever smoked. Further, over half of the sample at the outset of the study had no friends who smoked while 12% had three or more friends who used tobacco, see Table 1.

At the first assessment, the average depressive symptom score was 9.07 (SD=2.76) and about 75% of the participants were non-smokers, see Table 1. Less than 1% of the participants at the first assessment reported smoking over 20 cigarettes per day. At the second assessment, fewer participants were non-smokers and 25% of them reported smoking less than 10 cigarettes per day. At each of the four assessments, confirmatory factor analyses revealed adequate fit of the 9 items of the Center for Epidemiologic Scale-Depression (see Table 2).

Table 2.

Testing Structure of CES-D Depressive Symptoms by Wave

| Total |

Males |

Females |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wave | n | RMSEA [90% CI] | CFI | TLI | n | RMSEA | CFI | TLI | n | RMSEA | CFI | TLI |

| 1 | 6491 | 0.076 [0.073-0.080] | 0.964 | 0.952 | 3141 | 0.00 [0.00-0.00] | 1.00 | 1.00 | 3350 | 0.00 [0.00-0.00] | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 2 | 4831 | 0.083 [0.078-0.087] | 0.964 | 0.952 | 2313 | 0.00 [0.00-0.00] | 1.00 | 1.00 | 2518 | 0.00 [0.00-0.00] | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 3 | 4881 | 0.092 [0.087-0.096] | 0.958 | 0.944 | 2253 | 0.00 [0.00-0.00] | 1.00 | 1.00 | 2628 | 0.00 [0.00-0.00] | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 4 | 5113 | 0.082 [0.077-0.086] | 0.967 | 0.956 | 2352 | 0.00 [0.00-0.00] | 1.00 | 1.00 | 2760 | 0.00 [0.00-0.00] | 1.00 | 1.00 |

Note. RMSEA = Root Mean Square Error of Approximation; CFI = Comparative Fit Index; TLI = Tucker Lewis Index; CI = confidence interval.

Model Testing

The results of the models tested are presented in Table 3. Models 1 and 2 tested the measurement invariance and non-invariance for the depressive symptoms latent construct. The results revealed that restricting the loadings of the latent construct of depressive symptoms across time to be equal by gender deteriorated the fit of the model, χ2(28, N = 6,501) = 110.40, p<.0001 (see Table 3); and subsequent models allowed the loadings to be estimated freely in each gender. Models 3 and 4 tested whether the stability paths between depressive symptoms at each wave (i.e., dep1 → dep2) and cigarette use at each wave (i.e. cig1 → cig2) could be equated across gender. The results indicated that equating males and females to have the same stability paths for these construct worsened the fit of the model, χ2(6, N = 6,501) = 16.84, p<.01. Subsequent models did not restrict the stability paths to be the same in each gender group. Next, in Models 5 and 6 the cross paths (i.e., dep1→ cig2) were added to the emerging gender-specific model and tested by equating the cross paths, one at a time, by gender. The cross paths that did not deteriorate the fit of the model were between Wave 2 depressive symptoms to Wave 3 cigarette use and the Wave 2 cigarette use to Wave 3 depressive symptoms, χ2(2, N = 6,501) = 1.40, p=0.4960. The restrictions of equating all other paths resulted in worse model fit.

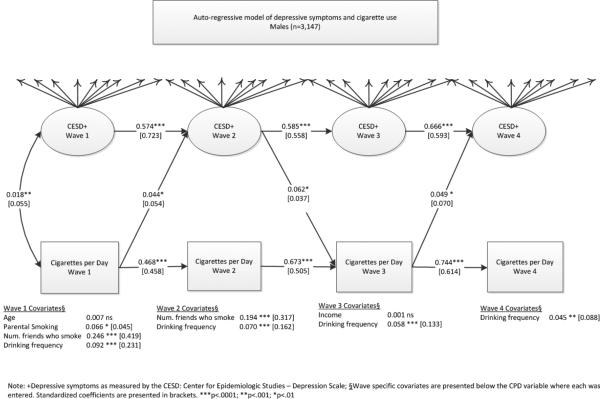

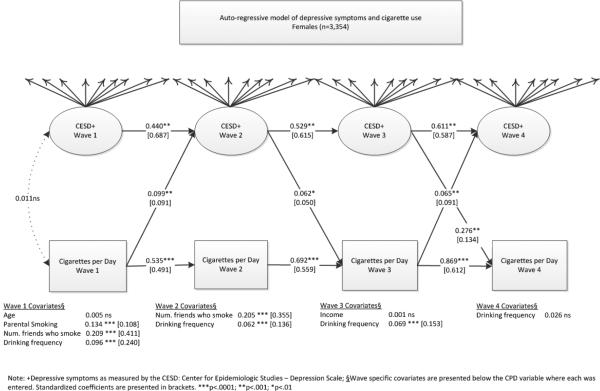

The gender-specific model had separate loadings for the measurement part of the depressive symptom latent construct by gender, separate stability paths by gender, and only two equated cross paths. Lastly, the covariates were added to the final model and the fit for this model is presented in Model 7. Figure 1 illustrates the raw and standardized coefficients (in brackets below the raw coefficients) for males and Figure 2 shows the final model for females.

Figure 1.

Longitudinal relationship between cigarettes smoked per day and a latent construct of depression for males showing significant relationship between the study variables.

Figure 2.

Longitudinal relationship between cigarettes smoked per day and a latent construct of depression for females showing significant relationship between the study variables.

Co-Occurrence between Cigarettes and Depressive Symptoms

At the initial assessment during adolescence, there was no correlation between the latent construct of depressive symptoms and cigarettes smoked per day for females (r=0.011, ns) but there was a small correlation for males (r=0.018, p=0.009). In Figure 2, the correlation for females is included as a dashed line to indicate that it was estimated in the model but found to be not significant.

Within trait stability for males

Examining the standardized path coefficients revealed that there were moderate to strong levels of stability in the development of depressive symptoms across the four waves of data. The association in depressive symptoms was strong in the first two waves and moderate between the last two for males (β1 =0.723, β =0.558, and β =0.593). The relationship between daily cigarette use revealed moderate and stable increases across time for males (β=0.458, β=0.505, β=0.614).

Cross trait effects for males

The results of the crossed effects in the final model, illustrated in Figure 1 for males, indicated that for males cigarette use at the first wave increases depressive symptoms at the next wave (β=0.054). Depressive symptoms at the second wave subsequently increased cigarette use at the third wave (β=0.037). Lastly, greater levels of cigarette use at the third wave were found to be associated with increases in depressive symptoms in the fourth wave (β=0.070). No other crossed effects were significant for males.

Within trait stability for females

For females, there were moderate levels of association across time for depressive symptoms (β=0.687, β=0.615, β=0.587) and cigarette use (β=0.491, β=0.559, β=0.612).

Cross trait effects for females

The cross paths suggest the presence of a bidirectional relationship for females. Similar to what was observed for males, increases in cigarette use at the first assessment were associated with increases in depressive symptoms at the second wave (β=0.091). Contrary to what was hypothesized, however, greater levels of depressive symptoms at the first wave were not associated with increases in cigarette use (β=0.008). Increases in depressive symptoms at the second assessment were associated with greater cigarette use at the third assessment (β=0.050). Bidirectional associations were found between cigarette use between the third and fourth waves (β=0.091) as well as between depressive symptoms at the third wave and cigarette use at the fourth wave (β=0.134) for females.

DISCUSSION

The aim of the present study was to examine the stability and crossed-effects between cigarettes smoked per day and depressive symptoms among a nationally representative sample of adolescents as they transitioned into young adulthood. Participants in this study reported smoking more cigarettes per day across time. This finding is consistent with previous work suggesting that the transition to young adulthood is the most vulnerable time for cigarette use (Tucker, Ellickson, Orlando, Martino, & Klein, 2005). There were moderate levels of stability in cigarettes smoked per day and depressive symptoms across the transition from adolescence to young adulthood for both sexes. This finding suggests that previous levels of cigarettes smoked per day predict greater cigarette use in the future for both males and females. Similarly, an additional finding of this study is that previous levels of depressive symptoms are significantly associated with future depressive symptoms for both males and females, although the degree of association or the factor loadings of the latent construct are not the same in both genders.

Finally, after taking into account the stability in these behaviors and after controlling for the influence of covariates, there were significant, gender-specific associations of influence from depressive symptoms to increases in cigarette use. For both males and females, greater levels of cigarette use during adolescence are associated with increases in depressive symptoms a year later. The magnitude of the association was greater for females and the bidirectional relationship was evident only for females in young adulthood. Controlling for the influence of initial levels of depressive symptoms and cigarette use, and their crossed influence, both males and females exhibited young adult levels of cigarette use that increased the likelihood of depressive symptoms years later.

Together these findings suggest that adolescence and young adulthood are vulnerable time periods for the feedback loop between cigarette use and depressive symptoms. Consistent with previous literature, the finding that depressive symptoms are associated with future cigarette use is consistent with previous literature reporting that individuals smoke for affect relief and mood enhancement (Mickens et al., 2011). Together with previous research (Bares & Andrade, 2012), this finding has implications for the content of preventive interventions for adolescents experiencing either cigarette use or depressive symptoms and for the bidirectional way in which cigarette use and depressive symptoms are associated in young adult females (Leung et al., 2012). Due to the correlation between these two behaviors and to the finding that increases in one behavior are likely to be associated with the other years down the road, preventive interventions need to be sensitive to providing modules addressing alternative ways to ameliorate mood as well as warn that cigarette use may exacerbate future symptoms.

Further, this study is one of the first to explore the gender-specific distal influence of adolescent depressive symptoms on cigarette use during young adulthood among a nationally representative sample. The finding that young adult females have poorer mental health as a consequence of smoking and that smoking subsequently reduces mental health has been recently reported among an Australian sample (Leung et al., 2012). The majority of studies reporting associations between symptoms of adolescent psychopathology and substance use typically find stronger relationships with externalizing rather than internalizing problems (Fischer et al., 2012). The present study suggests that individuals with internalizing problems, including depressive symptoms, are at risk of using substances as well, even after controlling for the development of these problems over time and after taking into account a variety of important covariates.

Limitations

Due to the design of the dataset, there are large gaps between the early adulthood assessments which may underestimate the associations and cross-lag relationships examined in this study. Future studies examining assessments closer together in time may be better able to capture stronger crossed associations between these common behaviors. Despite these limitations the findings reported here provide further evidence using a nationally representative sample of adolescents that depressive symptoms and cigarette use influence each other bi-directionally and reveal a gender-specific pattern in which female depressive symptoms are associated with greater levels of subsequent smoking.

Table 4.

Standardized Factor Loadings by Wave and Gender for Depression Items

| Wave 1 | Wave 2 | Wave 3 | Wave 4 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CES-D Categorical indicator | Females | Males | Females | Males | Females | Males | Females | Males |

| Item 1 | 0.604 | 0.613 | 0.627 | 0.570 | 0.639 | 0.606 | 0.643 | 0.647 |

| Item 2 | 0.776 | 0.766 | 0.778 | 0.777 | 0.813 | 0.745 | 0.844 | 0.823 |

| Item 3 | 0.420 | 0.277 | 0.449 | 0.310 | 0.531 | 0.392 | 0.566 | 0.464 |

| Item 4 | 0.577 | 0.545 | 0.537 | 0.541 | 0.561 | 0.560 | 0.510 | 0.524 |

| Item 5 | 0.869 | 0.817 | 0.867 | 0.801 | 0.926 | 0.896 | 0.921 | 0.881 |

| Item 6 | 0.521 | 0.495 | 0.551 | 0.518 | 0.507 | 0.412 | 0.464 | 0.421 |

| Item 7 | −0.540 | −0.471 | 0.571 | 0.483 | 0.607 | 0.604 | 0.691 | 0.600 |

| Item 8 | −0.797 | −0.711 | 0.796 | 0.762 | −0.820 | −0.776 | −0.831 | −0.804 |

| Item 9 | 0.617 | 0.632 | 0.576 | 0.594 | 0.603 | 0.552 | 0.581 | 0.545 |

Note. CES-D = Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale

Table 5.

Final model estimates by gender

| Females |

Males |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parameter | Unstandardized | SE | Standardized | Unstandardized | SE | Standardized | ||

| Within trait paths | ||||||||

| CESD Wave 1 | → | CESD Wave 2 | 0.440 ** | 0.135 | 0.687 | 0.574 *** | 0.102 | 0.723 |

| CESD Wave 2 | → | CESD Wave 3 | 0.529 ** | 0.192 | 0.615 | 0.585 *** | 0.126 | 0.558 |

| CESD Wave 3 | → | CESD Wave 4 | 0.611 ** | 0.216 | 0.587 | 0.666 *** | 0.144 | 0.593 |

| CPD Wave 1 | → | CPD Wave 2 | 0.535 *** | 0.012 | 0.491 | 0.468 *** | 0.012 | 0.458 |

| CPD Wave 2 | → | CPD Wave 3 | 0.692 *** | 0.023 | 0.559 | 0.673 *** | 0.030 | 0.505 |

| CPD Wave 3 | → | CPD Wave 4 | 0.869 *** | 0.026 | 0.612 | 0.744 *** | 0.026 | 0.614 |

| Cross trait paths | ||||||||

| CESD Wave 1 | → | CPD Wave 2 | 0.005 ns | 0.010 | 0.008 | −0.013 ns | 0.019 | −0.013 |

| CESD Wave 2 | → | CPD Wave 3 | 0.062 * | 0.024 | 0.050 | 0.062 * | 0.024 | 0.037 |

| CESD Wave 3 | → | CPD Wave 4 | 0.276 ** | 0.089 | 0.134 | 0.101 ns | 0.058 | 0.052 |

| CPD Wave 1 | → | CESD Wave 2 | 0.099 ** | 0.036 | 0.091 | 0.044 * | 0.021 | 0.054 |

| CPD Wave 2 | → | CESD Wave 3 | 0.004 ns | 0.016 | 0.005 | 0.004 ns | 0.016 | 0.005 |

| CPD Wave 3 | → | CESD Wave 4 | 0.065 ** | 0.023 | 0.091 | 0.049 * | 0.02 | 0.07 |

Note

p <.05

p <.01

p <.001

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Add text here if relevant. The author thanks Dr. Kenneth S. Kendler for his input on the conceptualization of this study.

FUNDING

The preparation of this manuscript was funded in part by NIH grant DA030310.

Footnotes

REFERENCES

- Andresen EM, Malmgren JA, Carter WB, Patrick DL. Screening for depression in well older adults: Evaluation of a short form of the CES-D (Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale). American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 1994;10(2):77–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anthony JC, Echeagaray-Wagner F. Epidemiologic analysis of alcohol and tobacco use. Alcohol Research and Health. 2000;24(4):201–208. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bares CB, Andrade FH. Racial/ethnic differences in the longitudinal progression of cooccurring negative affect and cigarette use: From adolescence to young adulthood. Addictive Behaviors. 2012;37(5):632–640. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2012.01.016. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2012.01.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben Lakhdar C, Cauchie G, Vaillant NG, Wolff FC. The role of family incomes in cigarette smoking: Evidence from French students. Social Science & Medicine. 2012;74(12):1864–1873. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2012.02.036. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2012.02.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benjet C, Wagner F, Borges G, Medina-Mora M. The relationship of tobacco smoking with depressive symptomatology in the Third Mexican National Addictions Survey. Psychological Medicine. 2004;34(5):881–888. doi: 10.1017/s0033291703001600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonilha AG, de Souza EST, Sicchieri MP, Achcar JA, Crippa JAS, Baddini-Martinez J. A motivational profile for smoking among adolescents. Journal of Addiction Medicine. 2013;7(6):439–446. doi: 10.1097/01.ADM.0000434987.76599.c0. doi: 10.1097/01.ADM.0000434987.76599.c0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonn-Miller MO, Zvolensky MJ, Johnson KA. Uni-morbid and co-occurring marijuana and tobacco use: Examination of concurrent associations with negative mood states. Journal of Addictive Diseases. 2010;29(1):68–77. doi: 10.1080/10550880903435996. doi: 10.1080/10550880903435996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breslau N, Fenn N, Peterson EL. Early smoking initiation and nicotine dependence in a cohort of young adults. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 1993;33(2):129–137. doi: 10.1016/0376-8716(93)90054-t. doi: 10.1016/0376-8716(93)90054-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brook JS, Cohen P, Brook DW. Longitudinal study of co-occurring psychiatric disorders and substance use. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 1998;37(3):322–330. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199803000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown RA, Lewinsohn PM, Seeley JR, Wagner EF. Cigarette smoking, major depression, and other psychiatric disorders among adolescents. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 1996;35(12):1602–1610. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199612000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chassin L, Presson CC, Pitts SC, Sherman SJ. The natural history of cigarette smoking from adolescence to adulthood in a midwestern community sample: Multiple trajectories and their psychosocial correlates. Health Psychology. 2000;19(3):223–231. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.19.3.223. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chassin L, Presson CC, Rose JS, Sherman SJ. The natural history of cigarette smoking from adolescence to adulthood: Demographic predictors of continuity and change. Health Psychology. 1996;15(6):478–484. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.15.6.478. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.15.6.478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen P, Cohen J, Kasen S, Velez CN, Hartmark C, Johnson J, Streuning E. An epidemiological study of disorders in late childhood and adolescence—I. Age and gender-Specific prevalence. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 1993;34(6):851–867. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1993.tb01094.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dierker LC, Avenevoli S, Merikangas KR, Flaherty BP, Stolar M. Association between psychiatric disorders and the progression of tobacco use behaviors. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2001;40(10):1159–1167. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200110000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dierker LC, Selya A, Piasecki T, Rose J, Mermelstein R. Alcohol problems as a signal for sensitivity to nicotine dependence and future smoking. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2013;132:688–693. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2013.03.018. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2013.03.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duhig AM, Cavallo DA, McKee SA, George TP, Krishnan-Sarin S. Daily patterns of alcohol, cigarette, and marijuana use in adolescent smokers and nonsmokers. Addictive Behaviors. 2005;30(2):271–283. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2004.05.016. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2004.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ennett ST, Bauman KE, Hussong A, Faris R, Foshee VA, Cai L, DuRant RH. The peer context of adolescent substance use: Findings from social network analysis. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2006;16(2):159–186. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-7795.2006.00127.x. [Google Scholar]

- Epstein JF, Induni M, Wilson T. Patterns of clinically significant symptoms of depression among heavy users of alcohol and cigarettes. Preventing Chronic Disease. 2009;6(1):A09. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer JA, Najman JM, Williams GM, Clavarino AM. Childhood and adolescent psychopathology and subsequent tobacco smoking in young adults: Findings from an Australian birth cohort. Addiction. 2012;107(9):1669–1676. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2012.03846.x. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2012.03846.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flay BR, Hu FB, Siddiqui O, Day LE, Hedeker D, Petraitis J, Sussman S. Differential influence of parental smoking and friends’ smoking on adolescent initiation and escalation and smoking. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1994 Doi: 10.2307-2137279;35(3):248–265. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fucito LM, Juliano LM, Toll BA. Cognitive reappraisal and expressive suppression emotion regulation strategies in cigarette smokers. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2010;12(11):1156–1161. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntq146. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntq146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gabrhelik R, Duncan A, Lee MH, Stastna L, Furr-Holden CDM, Miovsky M. Sex specific trajectories in cigarette smoking behaviors among students participating in the Unplugged school-based randomized control trial for substance use prevention. Addictive Behaviors. 2012;37(10):1145–1150. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2012.05.023. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2012.05.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilman SE, Rende R, Boergers J, Abrams DB, Buka SL, Clark MA, Lipsitt LP. Parental smoking and adolescent smoking initiation: An intergenerational perspective on tobacco control. Pediatrics. 2009;123(2):e274–e281. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-2251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glassman AH, Helzer JE, Covey LS, Cottler LB, Stetner F, Tipp JE, Johnson J. Smoking, smoking cessation, and major depression. JAMA: The Journal of the American Medical Association. 1990;264(12):1546–1549. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman E, Capitman J. Depressive symptoms and cigarette smoking among teens. Pediatrics. 2000;106(4):748–755. doi: 10.1542/peds.106.4.748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanson MD, Chen E. Socioeconomic status and health behaviors in adolescence: A review of the literature. Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 2007;30(3):263–285. doi: 10.1007/s10865-007-9098-3. doi: 10.1007/s10865-007-9098-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrell JS, Bangdiwala SI, Deng S, Webb JP, Bradley C. Smoking initiation in youth: The roles of gender, race, socioeconomics, and developmental status. Journal of Adolescent Health. 1998;23(5):271–279. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(98)00078-0. doi:10.1016/S1054-139X(98)00078-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris KM, Florey F, Tabor J, Bearman PS, Jones J, Udry JR. The National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health: Research design. University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill; Carolina Population Center: 2003. 2008. Retrieved September, 3. [Google Scholar]

- Hong T, Rice J, Johnson C. Social environmental and individual factors associated with smoking among a panel of adolescent girls. Women & Health. 2011;51(3):187–203. doi: 10.1080/03630242.2011.560241. doi: 10.1080/03630242.2011.560241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson KM, Colby SM, Sher KJ. Daily patterns of conjoint smoking and drinking in college student smokers. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2010;24(3):424–435. doi: 10.1037/a0019793. doi: 10.1037/a0019793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson KM, Sher KJ, Schulenberg JE. Conjoint developmental trajectories of young adult alcohol and tobacco use. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2005;114(4):612–626. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.114.4.612. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.114.4.612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kandel DB, Davies M, Karus D, Yamaguchi K. The consequences in young adulthood of adolescent drug involvement: An overview. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1986;43(8):746–754. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1986.01800080032005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kline RB. Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. Guilford Press; New York, NY: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Kobus K. Peers and adolescent smoking. Addiction. 2003;98:37–55. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.98.s1.4.x. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.98.s1.4.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kubik MY, Lytle LA, Birnbaum AS, Murray DM, Perry CL. Prevalence and correlates of depressive symptoms in young adolescents. American Journal of Health Behavior. 2003;27(5):546–553. doi: 10.5993/ajhb.27.5.6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leung J, Gartner C, Hall W, Lucke J, Dobson A. A longitudinal study of the bidirectional relationship between tobacco smoking and psychological distress in a community sample of young Australian women. Psychological Medicine. 2012;42(6):1273–1282. doi: 10.1017/S0033291711002261. doi: 10.1017/s0033291711002261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Low NCP, Dugas E, O'Loughlin E, Rodriguez D, Contreras G, Chaiton M, O'Loughlin J. Common stressful life events and difficulties are associated with mental health symptoms and substance use in young adolescents. BMC Psychiatry. 2012;12:116. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-12-116. doi: 10.1186/1471-244x-12-116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mickens L, Greenberg J, Ameringer KJ, Brightman M, Sun P, Leventhal AM. Associations between depressive symptom dimensions and smoking dependence motives. Evaluation & the Health Professions. 2011;34(1):81–102. doi: 10.1177/0163278710383562. doi: 10.1177/0163278710383562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mistry R, McCarthy WJ, de Vogli R, Crespi CM, Wu Q, Patel M. Adolescent smoking risk increases with wider income gaps between rich and poor. Health & Place. 2011;17(1):222–229. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2010.10.004. doi:10.1016/j.healthplace.2010.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, Muthén B. Mplus User's Guide. (Seventh ed.) 1998-2012 [Google Scholar]

- Ng M, Freeman MK, Fleming TD, Robinson M, Dwyer-Lindgren L, Thomson B, Gakidou E. Smoking prevalence and cigarette consumption in 187 countries, 1980-2012. JAMA: The Journal of the American Medical Association. 2014;311(2):183–192. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.284692. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.284692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nolen-Hoeksema S. Emotion regulation and psychopathology: The role of gender. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. 2012;8:161–187. doi: 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-032511-143109. doi: 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-032511-143109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okoli C, Greaves L, Fagyas V. Sex differences in smoking initiation among children and adolescents. Public Health. 2013;127(1):3–10. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2012.09.015. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2012.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pine DS, Cohen P, Gurley D, Brook J, Ma Y. The risk for early-adulthood anxiety and depressive disorders in adolescents with anxiety and depressive disorders. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1998;55(1):56–64. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.55.1.56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radloff LS. The CES-D scale A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement. 1977;1(3):385–401. [Google Scholar]

- Radloff LS. The use of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale in adolescents and young adults. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 1991;20(2):149–166. doi: 10.1007/BF01537606. doi: 10.1007/bf01537606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Resnick MD, Bearman PS, Blum RW, Bauman KE, Harris KM, Jones J, Shew M. Protecting adolescents from harm: Findings from the National Longitudinal Study on Adolescent Health. JAMA: The Journal of the American Medical Association. 1997;278(10):823–832. doi: 10.1001/jama.278.10.823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose JS, Dierker LC, Donny E. Nicotine dependence symptoms among recent onset adolescent smokers. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2010;106(2-3):126–132. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2009.08.012. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2009.08.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanton WR, Oei TPS, Silva PA. Sociodemographic characteristics of adolescent smokers. International Journal of the Addictions. 1994;29(7):913–925. doi: 10.3109/10826089409047917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sweeting H, Jackson C, Haw S. Changes in the socio-demographic patterning of late adolescent health risk behaviours during the 1990s: Analysis of two West of Scotland cohort studies. BMC Public Health. 2011;11:829. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-11-829. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-11-829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tucker JS, Ellickson PL, Orlando M, Martino SC, Klein DJ. Substance use trajectories from early adolescence to emerging adulthood: A comparison of smoking, binge drinking, and marijuana use. Journal of Drug Issues. 2005;35(2):307–332. [Google Scholar]

- Weinberger AH, McKee SA. Mood and smoking behavior: The role of expectancy accessibility and gender. Addictive Behaviors. 2012;37(12):1349–1352. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2012.07.010. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2012.07.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zahn-Waxler C, Shirtcliff EA, Marceau K. Disorders of childhood and adolescence: Gender and psychopathology. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. 2008;4:275–303. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.3.022806.091358. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.3.022806.091358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]