Abstract

Hydrogen sulphide (H2S) is known to play a vital role in human physiology and pathology which stimulated interest in understanding complex behaviour of H2S. Discerning the pathways of H2S production and its mode of action is still a challenge owing to its volatile and reactive nature. Herein we report azide functionalized metal-organic framework (MOF) as a selective turn-on fluorescent probe for H2S detection. The MOF shows highly selective and fast response towards H2S even in presence of other relevant biomolecules. Low cytotoxicity and H2S detection in live cells, demonstrate the potential of MOF towards monitoring H2S chemistry in biological system. To the best of our knowledge this is the first example of MOF that exhibit fast and highly selective fluorescence turn-on response towards H2S under physiological conditions.

Hydrogen sulphide (H2S), a colourless flammable gas, released from geothermal, anthropogenic and biological sources is well-known for its lethal effects upon overexposure1,2. However, this traditionally considered toxic chemical species has recently emerged as a third gasotransmitter gas (biological signalling molecule) after nitric oxide (NO) and carbon monoxide (CO)3,4,5,6. Organisms ranging from bacteria to mammals use H2S for signal transduction, immune response and energy production7,8,9,10,11. H2S therapy can also be used as a treatment to create hypothermia/hypometabolic state in surgical situations, to benefit conditions like trauma, reperfusion injury, and pyrexia12. The abnormal levels of H2S in cells known to be related to Alzheimer's disease13, diabetes14, Down's syndrome15, and cancer16. This makes H2S a potential target in the diagnostics and treatments of above diseases. Despite all recent progresses, efforts elucidating the molecular mechanism of H2S in physiological and pathological processes are still on-going.

Considering the complex biological functions of H2S selective and real-time detection of endogenous H2S is necessary to expand our knowledge about its exact physiological and pathological role. But due to its volatile and reactive nature, the accurate detection of H2S heavily depends on sample preparation and detection methods17,18. In this regard the fluorescence based methods are preferred because of their high sensitivity, simplicity, short response time, non-invasive nature, real-time monitoring and precludes other sample processing19,20. An efficient fluorescent probe should show significant change in fluorescence in response to H2S, high selectivity over other interfering biological substances, react fast enough (within minutes or even seconds) with H2S and should be cell permeable17,18. In particular, fluorescence turn-on probes are preferred to avoid false response and improved signal to noise ratio as the detection occurs relative to dark background. Combining all the properties in one probe is a challenge, thus the development of fluorescent probe for H2S is an active area of the current research.

Metal-organic frameworks (MOFs) composed of metal centers and organic struts have shown great potential in storage/separation, selective sensing, biomedical applications, etc21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28. Especially, the luminescent MOFs (LMOFs) have been utilized for detecting range of organic molecules and ions29,30,31,32,33,34,35. The designable architecture and choice of luminescent building units allows the fine tuning of luminescence properties of LMOFs. Also the molecular size exclusion (molecular sieving effect) can be used as a tool to nullify interference from potentially competing molecules and can act as pre-concentrator36. The tunable pore size also allows control over MOF analyte interactions improving sensitivity and molecular diffusion to modulate the response time. Finally, the high chemical stability and pre/post-synthetic modifications provides ample opportunities for MOF functionalization37. Owing to these advantages, MOF based fluorescence turn-on probe for H2S can be a promising material for visualizing and real-time monitoring of H2S. But MOFs exhibiting fluorescence turn-on in response to analyte are rare; in addition to this MOFs which shows both high selectivity along with turn-on response are still rare38.

Although, very recently MOFs have been used for selective adsorption and delivery of H2S, but utilization of the same as selective turn-on probe of H2S has not been reported24,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48. H2S detection in a living system relies on selective interactions, bioorthogonal to native cellular processes. The H2S mediated reduction of azide to amine is a well-known bioorthogonal reaction which works under physiological conditions49. The amine functionalized MOF UiO-66@NH2 (1-NH2) composed of non-toxic and poorly absorbed zirconium metal attracted our attention. 1-NH2 is luminescent and chemically stable, which may allow the post synthetic modification of amine functionality to azide 1-N350. In addition to this, the UiO-66 analogues remain highly stable in physiological pH conditions for hours24. Thus we sought to utilize 1-N3 as switch to probe H2S under physiological pH conditions (Fig. 1).

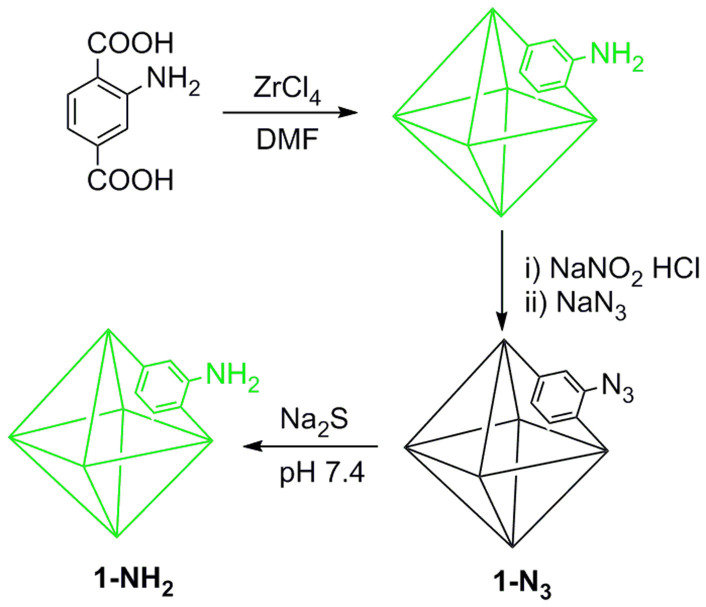

Figure 1. Schematic illustration of design of MOF based selective turn-on probe for H2S. Synthetic scheme for Zr(IV) based amine functionalized MOF 1-NH2.

Postsynthetic chemical modification of 1-NH2 to 1-N3 via diazotization route. Reduction of 1-N3 to 1-NH2 upon addition of Na2S at physiological pH giving rise to fluorescence turn-on response (H2S mediated reduction).

Herein we report, metal-organic framework 1-N3 as fluorescence turn-on probe for H2S detection. The 1-N3 shows fast and selective turn-on response towards H2S even in presence of potentially competing biomolecules under physiological conditions. Also the live cell imaging studies demonstrated that probe can sense the H2S in live cells. The high selectivity and sensitivity along with low toxicity make 1-N3 a promising material for monitoring H2S chemistry in biological system. To our knowledge this is the first example of MOF that exhibit fast and highly selective fluorescence turn-on response towards H2S under physiological conditions.

Results

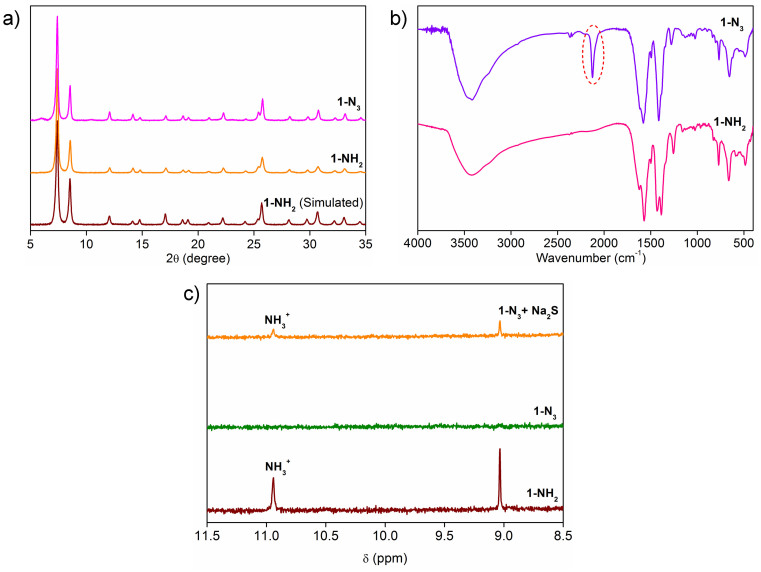

Probe 1-N3 was synthesized using 1-NH2 as precursor, as the use of azide functionalized ligand did not yield desired product. 1-NH2 was synthesized solvothermally using 2-aminoterephtalic acid and ZrCl4 with DMF as solvent51. The phase purity of bulk compound was confirmed by matching powder X-ray diffraction (PXRD) patterns of simulated and as-synthesized bulk compound (Fig. 2a). The thermogravimetric analysis revealed that MOF lose entrapped solvent molecules on heating and remains stable up to 350°C (Supplementary Fig. S1). The occluded guest molecules in 1-NH2 were exchanged with low boiling MeOH over 5 days and the exchanged MeOH molecules were then removed by thermal treatment under reduced pressure to get guest free porous 1-NH2. The activation of 1-NH2 was confirmed by N2 adsorption isotherm at 77 K (Supplementary Fig. S2). Further the chemical modification of free –NH2 to –N3 was achieved by diazotization of -NH2 followed by NaN3 treatment (for details please see experimental section). 1-N3 was then exchanged with H2O for 2 days and then activated under reduced pressure. The structural integrity of MOF upon post-synthetic modification was confirmed by PXRD patterns. The overlapping PXRD patterns of 1-NH2 and 1-N3 confirmed the structural integrity of 1-N3 (Fig. 2a). The FT-IR spectrum –N3 showed appearance of new distinct peak at 2127 cm−1 corresponding to azide group which is absent in 1-NH2 confirmed the transformation of –NH2 to –N3 (Fig. 2b). The chemical transformation was further confirmed using 1H-NMR. The 1-NH2 and 1-N3 were digested with DMSO-d6 and HF to get clear solution which was then subjected to NMR analysis. 1H-NMR of 1-NH2 showed peak corresponding to ammonium protons, this peak was absent in 1-N3 which also confirmed the successful transformation of –NH2 to –N3 (Fig. 2c).

Figure 2. Synthesis and characterization of MOF 1-NH2 and 1-N3.

(a) PXRD patterns of MOFs 1-NH2 Simulated, 1-NH2, 1-N3 demonstrating the stability of MOF before and after chemical modification. (b) FT-IR spectra of MOFs 1-NH2 and 1-N3 clearly showing the appearance of new peak corresponding to –N3 confirming chemical modification of –NH2 to –N3 functionality in MOF. (c) 1H-NMR of acid digested MOFs 1-NH2, 1-N3 and 1-N3 upon Na2S treatment.

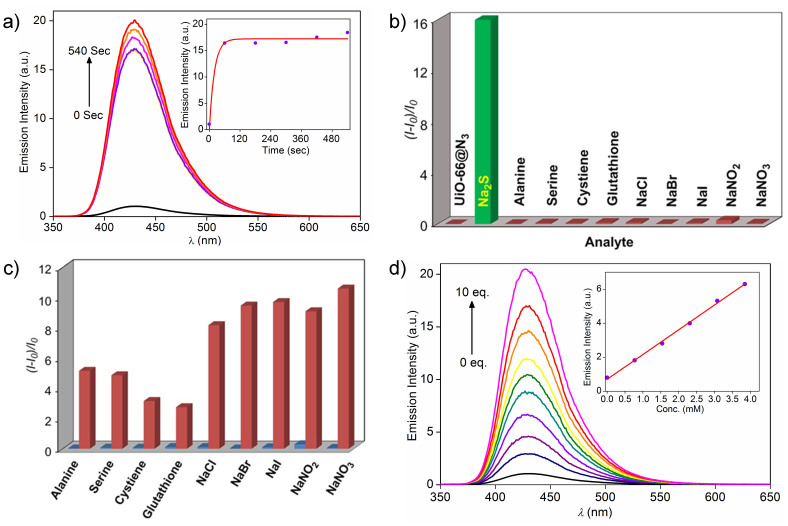

To probe the fluorescence turn-on response of 1-N3 towards H2S, 1-N3 was excited at 334 nm and the fluorescence spectrum was recorded in 350–650 nm range (in HEPES buffer 10 mM, pH 7.4). As expected, 1-N3 showed very weak fluorescence response, owing to the electron withdrawing azido group and remained in turn-off state (Fig. 3a and Supplementary Fig. S3). However, treatment of 1-N3 with 10 equivalents of Na2S (H2S source) resulted in remarkable increase in fluorescence intensity. To evaluate response time of 1-N3 towards H2S, fluorescence spectra were acquired with time (Fig. 3a). Almost 16 fold fluorescence enhancement was observed with t1/2 = 13.6 s and the reaction completes within tR = 180 s, which is comparable or better than known H2S probes17,47. Considering fast metabolism and variable nature of endogenous H2S in biological systems, the quick response shows the potential of 1-N3 in real-time intracellular H2S imaging.

Figure 3. Fast and selective turn-on response of 1-N3 towards Na2S.

(a) Fluorescence response of 1-N3 towards addition of Na2S after 0, 60, 180, 300, 420 and 540 seconds. Inset: Time dependence of emission intensity at 436 nm. (b) Relative fluorescence response of 1-N3 towards various analytes (10 equivalents/azide group) after 540 seconds of analyte addition. (c) Turn-On response of probe 1-N3 at 436 nm in presence of respective analyte (blue), followed by addition of Na2S in solution containing analyte (red). (d) Fluorescence response of 1-N3 with increasing concentrations of Na2S. All the experiments carried in HEPES buffer (10 mM, pH 7.4).

In complex biological systems highly selective response towards target analyte over potentially competing biological species is crucial for successful detection. Recently malonitrile functionalized MOF has been employed for detection of H2S by taking the advantage of reaction between malonitrile and thiol compounds with enhancement of photoluminescence. But the MOF is not selective to H2S and thiol containing amino acid cysteine (Cys) also showed fluorescence turn-on response under identical conditions47. Therefore, we examined the fluorescence response of 1-N3 towards an array of potentially interfering biological species (Fig. 3b). The reducing anions such as bromide, iodide did not show any effect on fluorescence intensity, despite the fact that the selective recognition of H2S by 1-N3 is based on H2S mediated reduction of azide to fluorescent amine. The biothiols like glutathione (GSH) and cysteine (Cys) are also known to reduce azide leading to off-target H2S detection52,53. However, addition of GSH or Cys showed negligible effect on fluorescence intensity of 1-N3 (Supplementary Fig. S4–S14).

Encouraged from these results selectivity of 1-N3 towards H2S in presence of these interfering analytes was also investigated. In a typical experiment, the solution containing 1-N3 and competing analyte (10 eq.) was treated with Na2S (10 eq.) and the fluorescence response was recorded after 10 min (Fig. 3c). The MOF showed turn-on response towards H2S even in presence of potentially competing analytes validating the high selectivity of 1-N3 towards H2S. Presence of competing analytes showed negligible effect on the turn-on efficiency of the H2S. Considering the complex biological system, 1-N3 can detect H2S without any interference from competing biological species avoiding off-target reactivity and false response.

The quantitative response of probe 1-N3 towards H2S was examined by fluorometric titration in HEPES buffer (10 mM pH 7.4) (Fig. 3d). The incremental addition of Na2S resulted in enhancement of characteristic fluorescence emission peak at 436 nm. The plot of fluorescence intensity at 436 nm against H2S concentration exhibited excellent linear correlationship (R = 0.99315) (Fig. 3d Inset). The H2S detection limit for 1-N3 was found to be 118 μM (signal to noise ratio, S/N = 3) which is in the range of H2S concentration found in most of the biological systems9,10,11.

To ascertain the structural integrity and the mechanism of turn-on response of 1-N3 towards H2S, PXRD and 1H-NMR experiments were carried out (Fig. 2C and Supplementary Fig. S15). The over-lapping PXRD patterns of 1-N3 before and after treatment of H2S demonstrated the stability of the probe under experimental conditions. Most importantly the 1H-NMR spectrum of 1-N3 did not show any peak corresponding to amine functionality but upon H2S treatment the peak corresponding to amine appears. This suggests that the fluorescence turn-on response of 1-N3 towards H2S is due to the reduction of ‘dark’ azido group to emissive amino group.

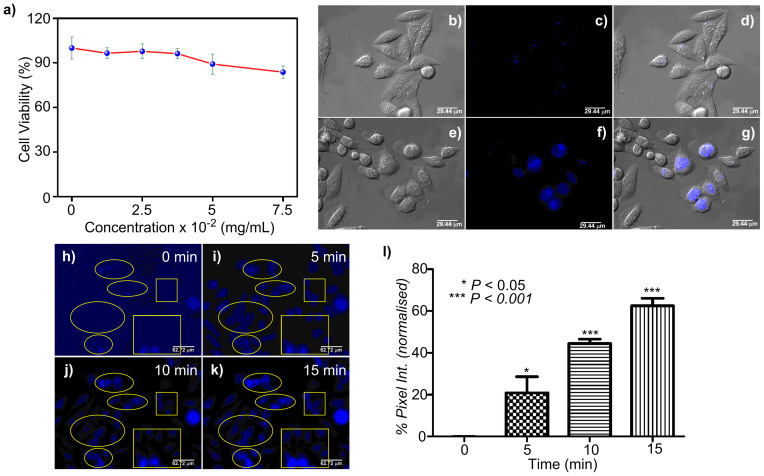

To demonstrate the sensing ability of MOF 1-N3 in the biological system cytotoxicity and live-cell imaging studies were carried out using HeLa cell line. The cytotoxicity of 1-N3 was determined by MTT assay. Various concentrations of 1-N3 were used to determine toxicity level of 1-N3 towards HeLa cell. HeLa cells upon incubation with 1-N3 for 6 h showed low toxicity and about 97% cell viability was determined at 0.025 mg/mL with comparable fluorescence turn-on response (14 fold, Supplementary Fig. S16) thus chosen as working concentration for imaging studies (Fig. 4a).

Figure 4. Cell viability assay and live cell imaging studies.

(a) HeLa cells were treated with 1-N3 before adding MTT for 6 h. Results are expressed as % of the control (100%). (b) DIC imgaes, (c) fluorescence, and (d) overlay image of HeLa cells incubated with 1-N3 for 6 h. (e-g) are respective DIC, fluorescence and overlay images of HeLa cells pre-incubated with 1-N3 followed by Na2S for 30 min. (h-k) Fluorescence images of HeLa cells incubated with probe 1-N3 followed by incubation with Na2S, acquired at different time intervals (0, 5, 10 and 15 min). Same experiment was repeated thrice and data represented in Supplementary Fig. S17. (l) Bar diagram showing statistically significant (P < 0.05 for 5 min data and P < 0.001 for 10 and 15 min data) increase in mean intensity of ROI Vs time. Statical analysis were performed by using one way ANOVA and Dunett's multiple comparison test with respect to 0 min as control.

In cell imaging study, very low fluorescence was observed when HeLa cells were incubated with only 1-N3 at 37°C for 6 h (Fig. 4b–d). However, when same cells were again incubated with Na2S at 37°C for 30 min under identical conditions, strong fluorescence was observed inside the cells (Fig. 4e–g). The exact mechanism of cellular uptake is not known at present, however the HeLa cells are known to take up particles less than 200 nm via endocytosis pathway54,55. These experiments suggest that the MOF 1-N3 can be used to monitor intracellular H2S and we believe that this is the first report of MOF based turn-on probe for H2S employed in living cell.

Finally, we determined the quantitative response of the fluorescence intensity in HeLa cells with time. The pixel intensity obtained from selected region of interest (ROI) versus time was plotted (Fig. 4h–l and Supplementary Fig. S17). Initially the HeLa cells were incubated with only 1-N3 after that same cells were incubated with Na2S and image were acquired after regular time intervals (Fig. 4h–k). A sharp increment was observed when the pixel intensity of selected ROIs was plotted with time (Fig. 4l). From this data it was confirmed that the increment in the fluorescence intensity was due to the increase in the intracellular concentration of H2S in the cells. These live-cell studies data supports the feasibility of this method for detection of intracellular H2S. These live-cell studies data supports the feasibility of this method for detection of intracellular H2S in case of any abnormal enhancement in H2S level. However the designed H2S sensor failed to detect the endogenously produced H2S by activating enzymes (CBS and CSE by NO) because of the amount of H2S generated by the enzyme activation is very low compared to detection limit. To address this problem studies in this line are in progress by designing a new MOF having better sensitivity.

Discussion

In conclusion, we have presented MOF based fluorescence turn-on probe for selective sensing of H2S. The MOF shows highly selective and fast fluorescence turn-on response towards H2S over potentially interfering chemical species including biothiols, amino acids and reducing anions. The low toxicity of MOF and live cell imaging studies demonstrates the potential of MOF in visualization and real-time monitoring of H2S in biological systems. To the best of our knowledge is the first example of MOF based selective turn-on probe for H2S. We anticipate that MOF based turn-on sensor for H2S are still in infancy and there is further scope for the improvement of the performance. The present report will stimulate the research in the field of MOF based sensors for H2S and other biologically important molecules to probe their physiological and pathological roles.

Methods

Materials

All the chemicals and solvents were purchased from commercial sources and used as received.

Physical Measurements

Powder X-Ray diffraction patterns (PXRD) were measured on BrukerD8 Advanced X-Ray diffractometer using Cu Kα radiation (λ = 1.5406 Å) in 5 to 40° 2θ range. The IR spectra were recorded on NICOLET 6700 FT-IR spectrophotometer using KBr pellet in 400–4000 cm−1 range. Gas adsorption analysis was performed using BelSorp-max instrument from Bel Japan. Fluorescence measurements were done using Horiba FluoroLog instrument. 1H-NMR analysis was performed using JeolECS-400 400 MHz instrument. The fluorescence images of cells were taken using Olympus Inverted IX81 equipped with Hamamatsu Orca R2 microscope.

Synthesis of 1-N3

Direct synthesis of 1-N3 using of azide functionalized ligand did not yield desired product, thus 1-N3 was synthesized starting from 1-NH2.

Synthesis of 1-NH2

1-NH2 was synthesized by slight modification of previously reported procedure50. 2-aminoterephtalic acid (0.7602 g) was dissolved in 14 mL DMF and anhydrous ZrCl4 (0.3263 g) was dissolved in 42 mL DMF. Both the solutions were then mixed and sonicated for 10 min. The mixture then distributed in 7 teflon lined autoclave vessels and heated at 120°C for 24 h. After cooling overnight, the yellowish microcrystalline material was isolated by centrifugation. The material was then rinsed three times with DMF followed by three additional washings with methanol and then dried overnight in a vacuum oven at 70°C. The unreacted starting material and occluded solvent molecules were removed by exchanging it with MeOH over 5 days and the volatile MeOH was removed under vacuum at 120°C.

Synthesis of 1-N3

Solution of NaNO2 (0.066 g) in H2O (2 mL) was drop wise added to the suspension of activated MOF 1-NH2 in H2O-HCl (1:1, 4 mL) at 0°C. After stirring for 30 min, the suspension was then added drop wise to ice cold solution of NaN3 (0.150 g) in H2O (2 mL). Upon completing the addition the solution was warmed to room temperature and stirred overnight. The suspension was then vacuum filtered and three times washed with cold water and dried under reduced pressure. The unreacted starting material was removed by exchanging it with H2O for 2 days and activated by thermal treatment at 120°C to yield 1-N3.

Photo Physical Studies

Preparation of the medium

Deionized water was used throughout all experiments. HEPES buffer was prepared by dissolving solid HEPES (2.383 g) in deionized water (1 L) followed by adjustment of pH by 0.5 (N) NaOH solution.

Fluorescence studies

In typical experimental setup, 0.5 mg of 1-N3 was weighed and added to cuvette containing 2 mL of HEPES buffer (10 mM, pH 7.4) under constant stirring. The fluorescence spectra were recorded in range 350–650 nm by exciting 1-N3 at 334 nm with emission and excitation slits 1.5 and 1.5 respectively. To determine the fluorescence turn-on response of 1-N3 towards H2S, 10 equivalents of solid Na2S (with respect to azide functionality) was added to the cuvette and the fluorescence spectra were recorded at regular time intervals (every 60 seconds) till saturation.

Similar experiment was also performed by replacing Na2S by analyte of interest (Glutathione, Cysteine, Alanine, Serine, NaCl, NaBr, NaI, NaNO2, NaNO3).

NMR Analysis

~10 mg respective MOFs was digested with DMSO-d6 (600 μL) and 48% HF (30 μL) by sonication. Upon complete dissolution of the functionalized MOF, the clear solution was analysed by 1H-NMR.

MTT cell viability assay

Cells were dispersed in a 96-well microtiter plate at density of 104 cells per 100 μL an incubated at 37°C in a 5% CO2 for 16 hours. 1-N3 was added to each well in different concentration and incubated for another 6 hrs. DMEM solution of 1-N3 in each well was replaced by 110 μL of MTT-DMEM mixture (0.5 mg MTT/mL of DMEM) and incubated for 4 h in identical condition. After 4 h remaining MTT solution was removed and 100 μL of DMSO was added in each well to dissolve the formazan crystals. The absorbance was recorded in a microplate reader (Varioskan Flash) at the wavelength of 570 nm. All experiments were performed in quadruplicate, and the relative cell viability (%) was expressed as a percentage relative to the untreated control cells.

Cell imaging

The HeLa cells were purchased from National Centre for Cell Science, Pune (India). HeLa cells were grown in DMEM supplemented with 10% heat inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS), 100 IU/ml penicillin, 100 mg/ml streptomycin and 2 mM L-glutamine. Cultures were maintained in a humidified atmosphere with 5% CO2 at 37°C. The cultured cells were subcultured twice in each week, seeding at a density of about 15 × 104 cells/ml. Typan blue dye exclusion method was used to determine Cell viability. The fluorescence images were taken using Olympus Inverted IX81 equipped with Hamamatsu Orca R2 microscope by using DAPI filter. The 0.5 mg of 1-N3 was added to 2 mL water and sonicated for 10 minutes. The suspension was then passed through 0.2 μM filter and used for imaging study. The HeLa cells were incubated with above dispersion (50 μL) of 1-N3 in DMEM at pH 7.4, 37°C for 6 h. After washing with PBS the fluorescence images were acquired. In this case no significant fluorescence was observed. Same set of HeLa cells were treated with Na2S (8 mM) at 37°C for 30 min. After washing with PBS the fluorescence images showed blue fluorescence.

For measuring the intensity of cell fluorescence quantitatively, HeLa cells were first incubated with 1-N3 (at 37°C for 6 h) the plate was thoroughly washed with PBS and placed under the microscope fitted with an incubator. The images were taken in 5 min time intervals after addition of Na2S (10 mM). Six different region of interest (ROI) were selected and the intensity was obtained by using image j software. One way ANOVA analysis was done in GraphPad Prism5 software.

For measuring the intensity of cell fluorescence quantitatively, HeLa cells were first incubated with 1-N3 (at 37°C for 6 h) the plate was thoroughly washed with PBS and placed under the microscope fitted with an incubator. The images were taken in 5 min time intervals after addition of Na2S (10 mM). Five different region of interest (ROI) were selected and the intensity was obtained by using image j software.

Author Contributions

S.S.N. designed the project. S.S.N. and A.V.D. synthesized MOF and carried out sensing experiments. T.S. performed cell viability and imaging studies. S.S.N. wrote the manuscript. S.K.G. and P.T. supervised the work and finalized the manuscript. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Supplementary Material

SI

Acknowledgments

S. S. N. thankful to Council of Scientific & Industrial Research (CSIR) India for research fellowship. T. S. thankful to University Grants Commission (UGC) India for research fellowship. We are grateful to IISER Pune, DST (GAP/DST/CHE-12-0083), DST-SERB (SR/S1/OC-65/2012) and DAE (2011/20/37C/06/BRNS) for financial support.

References

- Reiffenstein R. J., Hulbert W. C. & Roth S. H. Toxicology of hydrogen sulphide. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 32, 109–134 (1992). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iversen K. J. & Spencer M. J. S. Effect of ZnO Nanostructure morphology on the sensing of H2S gas. J Phys. Chem. C 117, 26106–26118 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- Szabo C. Hydrogen sulphide and its therapeutic potential. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 6, 917–935 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boehning D. & Synder S. H. Novel neural modulators. Annu. Rev. Nurosci. 26, 105–135 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang R. Two's company, three's a crowd: can H2S be the third endogenous gaseous transmitter? FASEB J. 16, 1792–1798 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey T. S. & Pluth M. D. Chemiluminescent detection of enzymatically produced hydrogen sulphide: substrate hydrogen bonding influences selectivity for H2S over biological thiols. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 135, 16697–16704 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin V. S., Lippert A. R. & Chang C. J. Cell-trappable fluorescent probes for endogenous hydrogen sulphide signalling and imaging H2O2-dependent H2S production. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 110, 7131–7135 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang G. D. et al. H2S as a physiologic vasorelaxant: hypertension in mice with deletion of cystathionine γ-lyase. Science 322, 587–590 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L., Rose P. & Moore P. K. Hydrogen Sulphide and cell signalling. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 51, 169–187 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J. et al. A ratiometric fluorescent probe for biological signalling molecule H2S: fast response and high selectivity. Chem. Eur. J. 19, 4717–4722 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu P., Zhang J., Wang S., Zhu A. & Hou X. Sensing during in-situ growth of Mn-Doped ZnS QDs: A phosphorescent sensor for detection of H2S in biological samples. Chem. Eur. J. 20, 952–956 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drew K. L., Rice M. E., Kuhn T. B. & Smith M. A. Neuroprotective adaptations in hibernation: therapeutic implications for ischemia-reperfusion, traumatic brain injury and neurodegenerative diseases. Free Radical Biol. Med. 31, 563–573 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eto K., Asada T., Arima K., Makifuchi T. & Kimura H. Brain hydrogen sulphide is severely decreased in Alzheimer's disease. Bio-chem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 293, 1485–1488 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamoun P., Belardinelli M.-C., Chabli A., Lallouchi K. & Chadefaux-Vekemans B. Endogenous hydrogen sulphide overproduction in Down syndrome. Am. J. Med. Genet. 116A, 310–311 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang W., Yang G., Jia X., Wu L. & Wang R. Activation of KATP channels by H2S in rat insulin-secreting cells and the underlying mechanisms. J. Physiol. 569, 519–531 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szabo C. et al. Tumor-derived hydrogen sulphide, produced by cystathionine-β-synthase, stimulates bioenergetics, cell proliferation, and angiogenesis in colon cancer. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 110, 12474–12479 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng H., Chen W., Burroughs S. & Wang B. Recent advances in fluorescent probes for the detection of hydrogen sulphide. Curr. Org. Chem. 17, 641–653 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- Mao G.–J. et al. High-sensitivity naphthalene-based two-photon fluorescent probe suitable for direct bioimaging of H2S in living cells. Anal. Chem. 85, 7875–7881 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu C. et al. Capture and visualization of hydrogen sulphide by a fluorescent probe. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 50, 10327–10329 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y. et al. A ratiometric fluorescent probe for rapid detection of hydrogen sulphide in mitochondria. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 52, 1688–1691 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eddaoudi M. et al. Systematic design of pore size and functionality in isoreticular MOFs and their application in methane storage. Science 295, 469–472 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takashima Y. et al. Molecular decoding using luminescence from an entangled porous framework. Nat. Commun. 2, 1–8 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kreno L. E. et al. Metal–organic framework materials as chemical sensors. Chem. Rev. 112, 1105–1125 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horcajada P. et al. Metal–organic frameworks in biomedicine. Chem. Rev. 112, 1232–1268 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuppler R. J. et al. Potential applications of metal-organic frameworks. Coord. Chem. Rev. 253, 3042–3066 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- Nagarkar S. S., Desai A. V. & Ghosh S. K. Stimulus responsive metal-organic frameworks. Chem. Asian J. 9, 2358–2376 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diring S. et al. Localized cell stimulation by nitric oxide using a photoactive porous coordination polymer platform. Nat. Commun. 4, 2684; 10.1038/ncomms3684 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoon M., Suh K., Natarajan S. & Kim K. Proton conduction in metal–rganic frameworks and related modularly built porous solids. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 52, 2688–2700 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allendorf M. D., Bauer C. A., Bhakta R. K. & Houk R. J. T. Luminescent metal–organic frameworks. Chem. Soc. Rev. 38, 1330–1352 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu Z., Deibert B. J. & Li J. Luminescent metal–organic frameworks for chemical sensing and explosive detection. Chem. Soc. Rev. 43, 5815–5840 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagarkar S. S., Joarder B., Chaudhari A. K., Mukherjee S. & Ghosh S. K. Highly selective detection of nitro explosives by a luminescent metal–organic framework. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 52, 2881–2885 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foucault-Collet A. et al. Lanthanide near infrared imaging in living cells with Yb3+ nano metal-organic frameworks. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 110, 17199–17204 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu P. et al. Luminescent metal-organic frameworks for selectively sensing nitric oxide in an aqueous solution and in living cells. Adv. Funct. Mat. 22, 1698–1703 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- Cui Y., Yue Y., Qian G. & Chen B. Luminescent functional metal–organic frameworks. Chem. Rev. 112, 1126–1162 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sen S., Nair N. N., Yamada T., Kitagawa H. & Bharadwaj P. K. High proton conductivity by a metal–organic framework incorporating Zn8O clusters with aligned imidazolium groups decorating the channels. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 134, 19432–19437 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiong R. et al. Evaluation of functionalized isoreticular metal organic frameworks (IRMOFs) as smart nonporous preconcentrators of RDX. Sens. and Actuators B 148, 459–468 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z. & Cohen S. M. Postsynthetic modification of metal–organic frameworks. Chem. Soc. Rev. 38, 1315–1329 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shustova N. B., Cozzolino A. F., Reineke S., Baldo M. & Dinca M. Selective turn-on ammonia sensing enabled by high-temperature fluorescence in metal–organic frameworks with open metal sites. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 135, 13326–13329 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamon L. et al. Comparative study of hydrogen sulphide adsorption in the MIL-53(Al, Cr, Fe), MIL-47(V), MIL-100(Cr), and MIL-101(Cr) metal−organic frameworks at room temperature. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 131, 8775–8777 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petit C., Mendoza B. & Bandosz T. J. Hydrogen sulphide adsorption on MOFs and MOF/Graphite oxide composites. ChemPhysChem 11, 3678–3684 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petit C. & Bandosz T. J. Exploring the coordination chemistry of MOF–graphite oxide composites and their applications as adsorbents. Dalton Trans. 41, 4027–4035 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allan P. K. et al. Metal–organic frameworks for the storage and delivery of biologically active hydrogen sulphide. Dalton Trans. 41, 4060–4066 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutierrez-Sevillano J. J., Martin-Calvo A., Dubbeldam D., Calero S. & Hamad S. Adsorption of hydrogen sulphide on metal-organic frameworks. RSC Adv. 3, 14737–14749 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- Chavan S. et al. Fundamental aspects of H2S adsorption on CPO-27-Ni. J. Phys. Chem. C 117, 15615–15622 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- Nickerl G. et al. Integration of accessible secondary metal sites into MOFs for H2S removal. Inorg. Chem.Front. 1, 325–330 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- Liu B. & Chen Y. Responsive lanthanide coordination polymer for hydrogen sulphide. Anal. Chem. 85, 11020–11025 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H. et al. A malonitrile-functionalized metal-organic framework for hydrogen sulfide detection and selective amino acid molecular recognition. Sci. Rep., 4, 4366; 10.1038/srep04366 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J. et al. Ag(I) binding, H2S sensing, and white-light emission from an easy-to-make porous conjugated polymer. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 136, 2818–2824 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lippert A. R., New E. J. & Chang C. J. Reaction-based fluorescent probes for selective imaging of hydrogen sulphide in living cells. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 133, 10078–10080 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kandiah M. et al. Synthesis and stability of tagged UiO-66 Zr-MOFs. Chem. Mater. 22, 6632–6640 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- Morris W., Doonan C. J. & Yaghi O. M. Postsynthetic modification of a metal–organic framework for stabilization of a hemiaminal and ammonia uptake. Inorg. Chem. 50, 6853–6855 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lippert A. R. Designing reaction-based fluorescent probes for selective hydrogen sulphide detection. J. Inorg. BioChem. 133, 136–142 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sasakura K. et al. Development of a highly selective fluorescence probe for hydrogen sulphide. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 133, 18003–18005 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vivero-Escoto J. L., Slowing I. I., Trewyn B. G. & Lin V. S. Y. Mesoporous silica nanoparticles for intracellular controlled drug delivery. small 6, 1952–1967 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin L. et al. A dual pH and temperature responsive polymeric fluorescent sensor and its imaging application in living cells. Chem. Commun. 18, 4486–4488 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

SI