Abstract

Background

The risk of Kaposi sarcoma (KS) among HIV-infected persons on antiretroviral therapy (ART) is not well defined in resource-limited settings. We studied KS incidence rates and associated risk factors in children and adults on ART in Southern Africa.

Methods

We included patient data of six ART programs in Botswana, South Africa, Zambia, and Zimbabwe. We estimated KS incidence rates in patients on ART measuring time from 30 days after ART initiation to KS diagnosis, last follow-up visit, or death. We assessed risk factors (age, sex, calendar year, WHO stage, tuberculosis, and CD4 counts) using Cox models.

Findings

We analyzed data from 173,245 patients (61% female, 8% children aged <16 years) who started ART between 2004 and 2010. 564 incident cases were diagnosed during 343,927 person-years (pys). KS incidence rate overall was 164/100,000 pys (95% confidence interval [CI] 151–178). The incidence rate was highest 30 to 90 days after ART initiation (413/100,000 pys; 95% CI 342–497) and declined thereafter (86/100,000 pys[95% CI 71–105]>2 years after ART initiation). Male sex (adjusted hazard ratio [HR] 1.34; 95% CI 1.12–1.61), low current CD4 counts (≥500 cells/µL versus <50 cells/µL, adjusted HR 0.36; 95% CI 0.23–0.55) and age (5 to 9 years versus 30 to 39 years, adjusted HR 0.20; 95% CI 0.05–0.79) were relevant risk factors for developing KS.

Interpretation

Despite ART, KS risk in HIV-infected persons in Southern Africa remains high. Early HIV testing and maintaining high CD4 counts is needed to further reduce KS-related morbidity and mortality.

Keywords: Kaposi sarcoma, incidence rate, HIV, AIDS, antiretroviral therapy, cohort study

Introduction

Kaposi sarcoma (KS) is the most common cancer in HIV-infected persons in Southern Africa. KS is caused by human herpesvirus 8 (HHV-8), which is very common in Southern Africa: 35% to 50% of HIV-infected persons living in this region are co-infected with HHV-8.1;2 HIV-infection is one of the main risk factors for developing KS and affects between 10% to 25% of the general population in Southern African countries.3 KS incidence rate in HIV-infected persons can be reduced by 70% to 90% if the HIV-infection is treated with antiretroviral therapy (ART).4–6

Since 2004, ART has become widely available in most Southern African countries,7 and hopes have arisen that the KS burden would decrease. Three studies conducted in Africa found KS incidence rates between 138/100,000 and 340/100,000 person-years in patients treated with ART.5;8;9 These estimates suggest that the risk of developing KS in patients on ART is still substantial. In order to effectively plan and implement measures to reduce the KS burden in Africa, more reliable information on the KS risk in patients on ART and associated risk factors is needed.

Our goals were to estimate the incidence rate of KS in HIV-infected children and adults on ART in Southern Africa within the framework of the International epidemiological Databases to Evaluate AIDS (IeDEA), and to identify risk factors associated with KS development in these patients.

Methods

The International epidemiological Databases to Evaluate AIDS (IeDEA)

IeDEA is a global research consortium established in 2005 with seven regional networks (including four networks in sub-Saharan Africa) that collect clinical and epidemiological data on HIV-infected people. The African networks of IeDEA have been described in detail elsewhere.10 The Southern African region of IeDEA-SA includes ART programmes in seven countries (Botswana, Malawi, Lesotho, Republic of South Africa, Zambia, Mozambique, and Zimbabwe). All cohorts have been approved by local ethics committees or institutional review boards, use standardized methods of data collection, and schedule follow-up visits at least once every six months. Data is collected on patient demographics, use of ART, CD4 cell counts, AIDS-defining events and other complications, and deaths (see www.iedea-sa.org). Cohorts transfer their data to coordinating centers at the School of Public Health and Family Medicine, University of Cape Town, South Africa and the Institute of Social and Preventive Medicine, University of Bern, Switzerland.

Inclusion criteria and definitions

We included data from cohorts in IeDEA-SA which systematically recorded KS episodes in children and adults as part of routine clinical care. We included all ART-naïve HIV-1-infected patients who started treatment between 2004 and 2010(ART had become more widely available in Southern Africa from 2004 on). Data were merged on 28th February 2011. We excluded patients who had been diagnosed with KS before or within one month after they began ART (considered as prevalent KS cases), and all patients who were not followed-up for at least 30 days. CD4 cell count at ART initiation was defined as CD4 cell count closest to ART initiation (between 180 days before till 30 days after). We defined ART as a regimen of at least three antiretroviral drugs from any drug class, including protease inhibitors, nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors, and non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors.

Statistical analysis

We calculated incidence rates by dividing the number of patients who developed KS by the number of person-years at risk. We measured time from 30 days after ART initiation until the date of KS diagnosis, the last follow-up visit, or death. We used an intent-to-continue-treatment approach not accounting for subsequent treatment changes, treatment interruptions or terminations. We present KS incidence rates for the entire period of observation as well as for different time periods after starting ART, i.e. 30 to 90 days, >3 to 6 months, >6 to 12 months, >1 to 2 years, and >2 years after ART initiation. We assessed the following risk factors for developing KS: age, sex, CD4 cell counts at ART initiation, current CD4 cell counts, current or past tuberculosis (TB), and WHO clinical stages I/II versus stages III/IV. In a sensitivity analysis we evaluated WHO clinical stages I-III versus stage IV. Risk factors for incident KS were estimated using crude and adjusted Cox proportional hazard models. The multivariable models included sex, age, calendar period, WHO clinical stage at ART initiation, and current CD4 cell counts. The selection of the included variables was not automated, but based on biological and epidemiological rationale. Children below the age of 5 years were excluded from univariable and multivariable analyses that used absolute CD4 cell counts, because CD4 cell percentages are recommended for that age group instead. To assess potential selection bias we conducted two sensitivity analyses with varying definitions of incident KS and re-examined the impact of CD4 cell counts at the time of ART initiation on the risk of developing KS: In one sensitivity analysis we included all KS cases diagnosed after ART initiation as incident KS, in a second sensitivity analysis we excluded all patients diagnosed with KS within the first six months after ART initiation as prevalent KS cases. We also assessed whether time spent on ART (1 - 6 months versus >6 months after ART initiation) affected the risk factors for developing KS. Interaction was assessed using likelihood ratio tests. Results are presented as medians with interquartile ranges (IQR), incidence rates per 100,000 person-years, Kaplan-Meier estimates of the cumulative incidence rate of KS, crude and adjusted hazard ratios with 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs). All analyses were done in MySQL (Community Server, GPL, Version 5.5.11) and R (Version 2.13.1, The R Foundation for Statistical Computing).

Results

Characteristics of cohorts and patients

Out of 22 cohorts in the IeDEA-SA database 16 cohorts with 141,423 patients did not systematically record KS episodes and were therefore excluded from the analysis. Another 19,519 patients were excluded for reasons detailed in Figure, Supplemental Digital Content 1.

We included data from 173,245 patients (52%) with 564 incident KS cases, drawn from six cohorts located in four countries (Botswana, South Africa, Zambia, and Zimbabwe). 87% of patients (150,732) were drawn from the Centre for Infectious Disease Research in Zambia (CIDRZ) cohort. The median age at ART initiation was 34 years (IQR 28 to 41), and most patients were female (105,787; 61%). Median CD4 cell count at ART initiation was 142 cells/µL (IQR 72 to 218).

Those we excluded had similar proportions of women and girls (60% versus 61%) and a similar age distribution (median age: both 34 years) as those we included, but were more likely to be in WHO clinical stage IV at ART initiation (29% versus 9%). We excluded a total of 2,684 KS cases from our analysis; 2,521 (94%) because they were prevalent cases.

Overall, 564 patients developed KS and 172,681 patients did not. Median age at ART initiation was similar in patients who did and did not develop KS (median age: 35 versus 34 years). KS patients had lower median CD4 cell counts at ART initiation than patients who did not develop KS (126 cells/µl versus 142 cells/µl). Median follow-up time for all included patients was 582 days (IQR 241 to 1'115 days). In individuals who developed incident KS, median time from ART initiation to diagnosis with KS was 229 days (IQR 74 to 550 days). In patients aged ≥5 years, CD4 cell counts at ART initiation were missing for 24,269 (15%) individuals who did not develop KS and 105 (19%) individuals who developed KS. Patients with missing CD4 cell counts at ART initiation were slightly more likely to be in WHO clinical stage III/IV at ART start than patients for whom CD4 cell counts at ART start were available (69% versus 60%).

Incidence rates and risk factors of developing Kaposi sarcoma

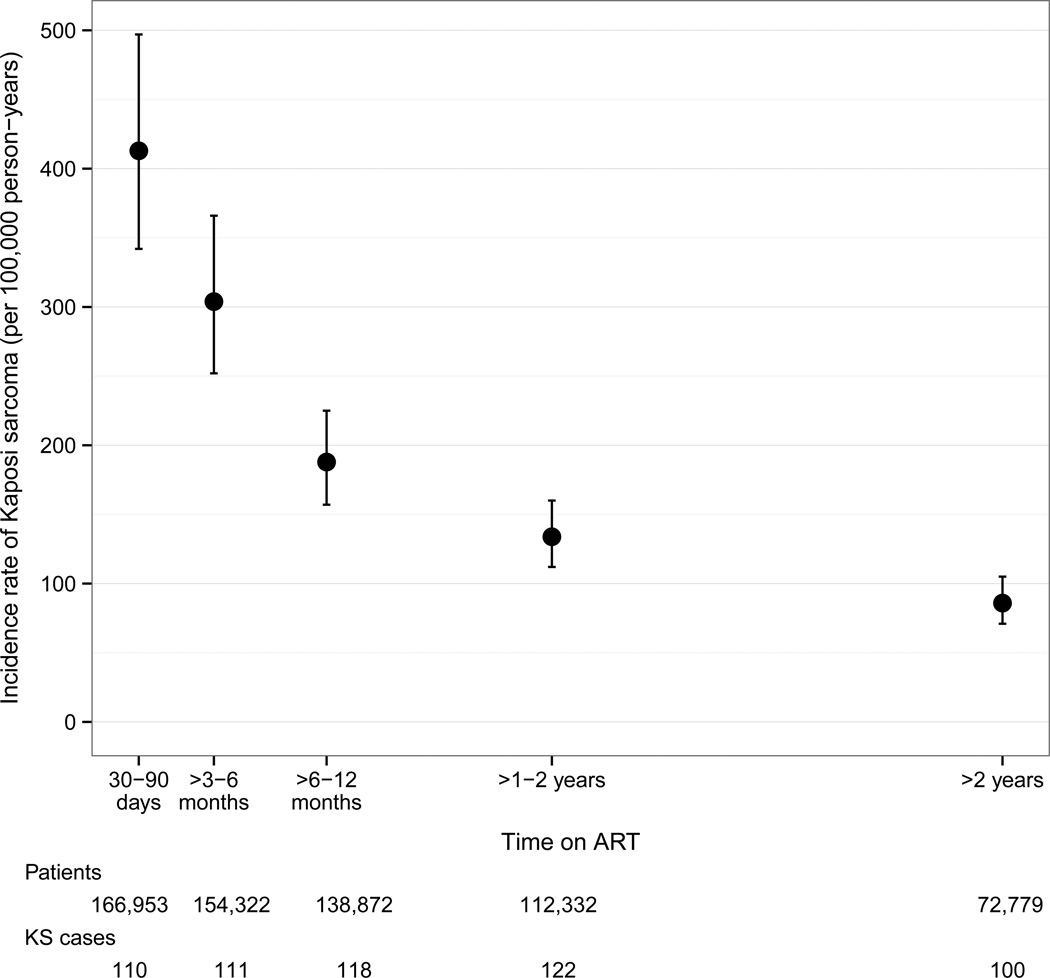

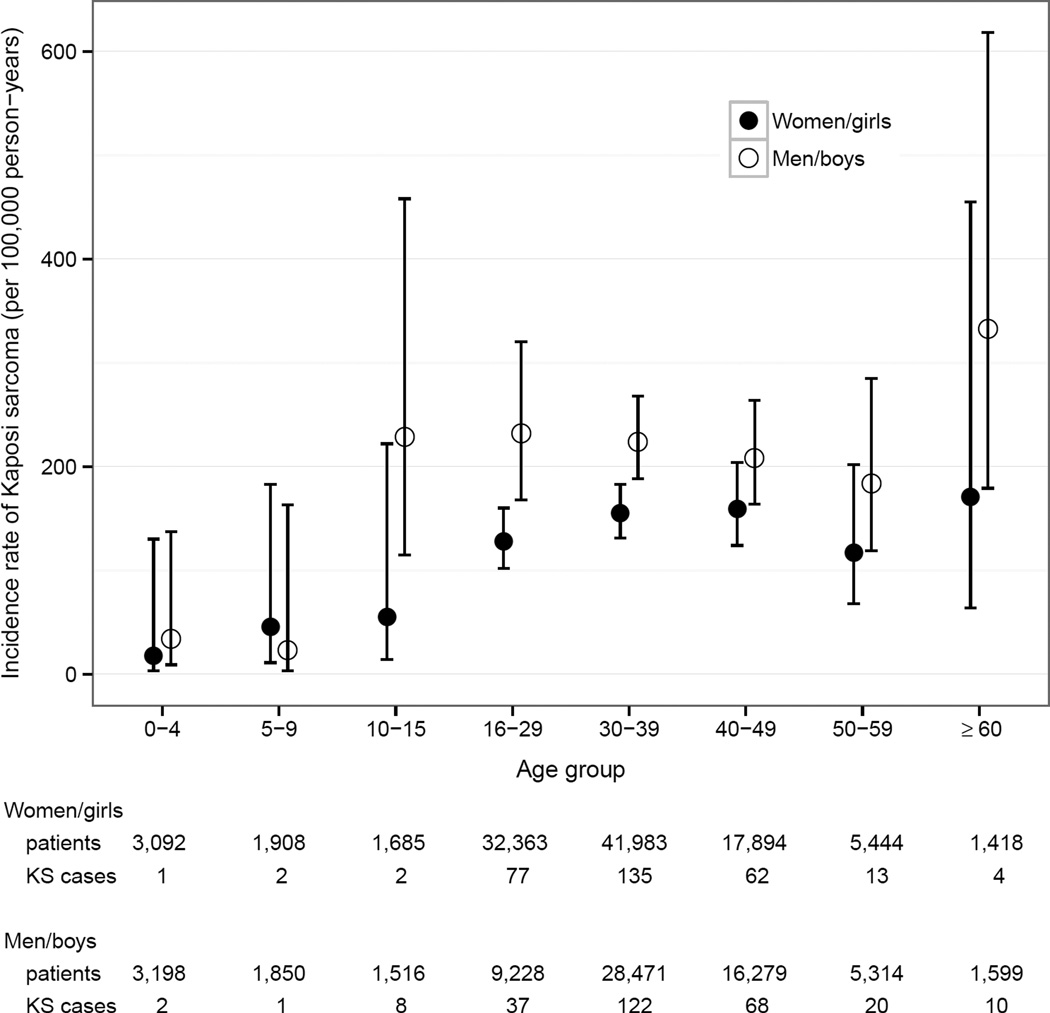

Table 1 shows the number of KS cases, person-years under observation and incidence rates. Overall, the incidence rate for KS in patients on ART was 164/100’000 person-years (95% CI 151–178). The KS incidence rate was 413/100,000 person-years (95% CI 342–497) 30 to 90 days after ART start, decreased to 188/100,000 person-years (95% CI 157–225) six to twelve months after ART initiation and reached 86/100,000 person-years (95% CI 71–105)>2 years after ART start (Figure 1). After five years on ART, the cumulative incidence of KS was 0.5% (95% CI 0.43–0.58) in women and 0.71% (95% CI 0.62–0.83) in men. KS incidence rate was lower in Zimbabwe than in Botswana, South Africa, and Zambia. However, confidence intervals overlapped widely. KS incidence rate increased steeply with age in children and young adults, reached a plateau around age 30 and increased after age 60 (Figure 2). KS incidence rate was 59/100,000 person-years in HIV-infected children and adolescents (aged <16 years) and 173/100,000 person-years in HIV-infected adults (aged ≥16 years).

Table 1.

Kaposi sarcoma incidence rates and unadjusted hazard ratios for developing Kaposi sarcoma in patients on ART.

| Patients (N) |

Person- years at risk |

KS cases (N) |

Incidence rate per 100,000 pys (95% CI) |

HR | (95% CI) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All | 173,245 | 343,927 | 564 | 164 | (151 – 178) | - | - | |

| Country | Botswana | 704 | 1,490 | 2 | 134 | (34 – 537) | - | - |

| South Africa | 19,532 | 34,717 | 48 | 138 | (104 – 183) | - | - | |

| Zambia | 150,732 | 302,543 | 510 | 169 | (155 – 184) | - | - | |

| Zimbabwe | 2,277 | 5,177 | 4 | 77 | (29 – 206) | - | - | |

| Sex | Female | 105,787 | 213,306 | 296 | 139 | (124 – 156) | 1.00 | - |

| Male | 67,457 | 130,616 | 268 | 205 | (182 – 231) | 1.45 | (1.23 – 1.72) | |

|

Age at ART start [years] |

<5 | 6,290 | 11,329 | 3 | 26 | (9 – 82) | 0.15 | (0.05 – 0.45) |

| 5 – 9 | 3,758 | 8,712 | 3 | 34 | (11 – 107) | 0.20 | (0.06 – 0.62) | |

| 10 – 15 | 3,201 | 7,099 | 10 | 141 | (76 – 262) | 0.80 | (0.43 – 1.51) | |

| 16 – 29 | 41,591 | 76,325 | 114 | 149 | (124 – 179) | 0.80 | (0.64 – 0.99) | |

| 30 – 39 | 70,454 | 141,599 | 257 | 181 | (161 – 205) | 1.00 | - | |

| 40 – 49 | 34,174 | 71,570 | 130 | 182 | (153 – 216) | 1.01 | (0.82 – 1.25) | |

| 50 – 59 | 10,758 | 21,941 | 33 | 150 | (107– 212) | 0.83 | (0.58 – 1.19) | |

| ≥60 | 3,017 | 5,349 | 14 | 262 | (155 – 442) | 1.37 | (0.80 – 2.34) | |

|

Calendar year at ART start |

2004 – 2006 | 54,717 | 177,507 | 192 | 108 | (94 – 125) | 1.00 | - |

| 2007 – 2010 | 118,528 | 166,420 | 372 | 224 | (202 – 247) | 1.49 | (1.24 – 1.79) | |

|

WHO stage at ART start |

I - II | 64,121 | 117,855 | 182 | 154 | (134 – 179) | 1.00 | - |

| III - IV | 102,301 | 213,594 | 367 | 172 | (155 – 190) | 1.16 | (0.97 – 1.39) | |

| Missing | 6,823 | 12,477 | 15 | 120 | (72 – 199) | - | - | |

|

CD4 at

ART start [cells/µL]* |

<50 | 25,060 | 49,981 | 92 | 184 | (150 – 226) | 1.00 | - |

| 50 – 99 | 26,229 | 54,076 | 96 | 178 | (145 – 217) | 0.94 | (0.71 – 1.26) | |

| 100 – 199 | 51,479 | 104,069 | 156 | 150 | (128 – 175) | 0.78 | (0.60 – 1.01) | |

| 200 – 349 | 32,485 | 58,217 | 77 | 132 | (106 – 165) | 0.64 | (0.47 – 0.87) | |

| 350 – 499 | 4,511 | 8,439 | 21 | 249 | (162 – 382) | 1.23 | (0.76 – 1.98) | |

| ≥500 | 2,815 | 5,046 | 14 | 277 | (164 – 468) | 1.36 | (0.77 – 2.38) | |

| Missing | 24,374 | 52,767 | 105 | 199 | (164 – 241) | - | - | |

|

Current

CD4 [cells/µL]* |

<50 | - | 16,636 | 67 | 403 | (317 – 512) | 1.00 | - |

| 50 – 99 | - | 21,629 | 66 | 305 | (240 – 388) | 0.81 | (0.57 – 1.14) | |

| 100 – 199 | - | 62,296 | 136 | 218 | (185 – 258) | 0.65 | (0.48 – 0.87) | |

| 200 – 349 | - | 94,036 | 128 | 136 | (114 – 162) | 0.49 | (0.36 – 0.67) | |

| 350 – 499 | - | 59,652 | 75 | 126 | (100 – 158) | 0.54 | (0.38 – 0.77) | |

| ≥500 | - | 55,727 | 37 | 66 | (48 – 92) | 0.31 | (0.20 – 0.47) | |

| Missing | - | 22,619 | 52 | 230 | (175 – 302) | - | - | |

Children aged <5 years were excluded from analyses of absolute CD4 cell counts.

ART, antiretroviral therapy; CI, confidence interval; HR, Hazard ratio; KS, Kaposi sarcoma; Pys, person-years.

Figure 1.

Kaposi sarcoma incidence rates by time on ART.

Figure 2.

Kaposi sarcoma incidence rates by age groups, stratified for gender.

In univariable analyses, the risk of developing KS increased with age and with decreasing current CD4 cell counts (Table 1). Men were more likely than women to develop KS. Patients starting ART in WHO clinical stage III/IV did not have a higher risk of developing KS than patients starting ART in WHO clinical stage I/II. A sensitivity analysis showed that patients who started ART at WHO stage IV were significantly more likely to develop KS than patients starting ART at earlier WHO stages (HR 2.48, 95% CI 2.00–3.08). We found no evidence for an association between current or past TB and the risk of developing KS (data not shown). CD4 cell counts at ART initiation were not clearly associated with the risk of developing KS. In patients who started ART at CD4 cell counts <350 cells/µl, the risk of developing KS decreased with increasing CD4 cell counts at ART initiation (200–349 cells/µL versus<50 cells/µL, HR 0.64; 95% CI 0.47–0.87). In contrast, in patients with CD4 cell counts ≥350 cells/µL at ART initiation KS risk was higher than in patients with CD4 cell counts <50 cells/µL at ART initiation (HR 1.28; 95% CI 0.86–1.89). This finding was confirmed when we included prevalent KS cases and also when we excluded all persons diagnosed with KS within the first six months after ART initiation for the purpose of sensitivity analyses.

In multivariable analyses adjusted for age, sex, current CD4 cell counts, WHO clinical stage at ART initiation and calendar year, we confirmed adulthood, male sex and low current CD4 cell counts as independent risk factors of developing KS (Table 2). In patients with current CD4 cell counts ≥500 cells/µl the risk of developing KS was reduced by 64% compared to patients with current CD4 cell counts <50 cells/µl (HR 0.36, 95% CI 0.23–0.55). KS incidence rate increased with calendar year of ART initiation. Patients who started ART between 2007 and 2010 were more likely to be diagnosed with KS than patients who started ART between 2004 and 2006 (adjusted HR 1.50, 95% CI 1.23–1.83). This finding was not explained by more severe immunosuppression in patients who started ART between 2007 and 2010. In contrast, patients who started ART in earlier years had a lower median CD4 cell count at ART initiation than patients who started between 2007 and 2010: 117 cells/ µL (IQR 55 to 188) versus 154 cells/µL (IQR 81 to 232). Patients who started ART in earlier years were also more likely to present with WHO clinical stage IV than patients who started between 2007 and 2010 (13% versus 7%). WHO stage at ART initiation was the only risk factor which showed a significant interaction with time on ART (1–6 months versus >6 months after ART initiation). In the multivariable analysis the overall HR for WHO stage III/IV versus I/II at ART initiation was 1.10, not reaching conventional levels of statistical significance. However, during the first six months of treatment the adjusted HR was 1.52 (95% CI 1.11–2.08) and HR 0.90 (95% CI 0.71–1.14) thereafter, p-value for interaction=0.023.

Table 2.

Risk factors for developing Kaposi sarcoma in patients on ART.

| Adjusted Hazard ratio (95% CI)* | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | Female | 1.00 | - |

| Male | 1.34 | (1.12 – 1.61) | |

| Age at ART start [years] | 5 – 9 | 0.20 | (0.05 – 0.79) |

| 10 – 15 | 0.74 | (0.35 – 1.57) | |

| 16 – 29 | 0.87 | (0.68 – 1.10) | |

| 30 – 39 | 1.00 | - | |

| 40 – 49 | 1.02 | (0.81 – 1.27) | |

| 50 – 59 | 0.85 | (0.58 – 1.24) | |

| ≥60 | 1.42 | (0.81 – 2.49) | |

| Calendar period at ART start | 2004 – 2006 | 1.00 | - |

| 2007 – 2010 | 1.50 | (1.23 – 1.83) | |

| WHO stage at ART start | I – II | 1.00 | - |

| III – IV | 1.10 | (0.91 – 1.32) | |

| Current CD4 [cells/µL] | <50 | 1.00 | - |

| 50 – 99 | 0.82 | (0.58 – 1.16) | |

| 100 – 199 | 0.65 | (0.48 – 0.88) | |

| 200 – 349 | 0.52 | (0.38 – 0.71) | |

| 350 – 499 | 0.59 | (0.41 – 0.84) | |

| ≥500 | 0.36 | (0.23 – 0.55) | |

ART, combined antiretroviral therapy; CI, confidence interval.

Adjusted for all variables listed, i.e. sex, age, calendar period, WHO stage, current CD4 cell count. Children aged <5 years were excluded from this analysis.

Discussion

The incidence rate of KS in HIV-infected patients treated with ART remains high (164/100‘000 person-years). KS incidence rate was 413/100,000 person-years 30 to 90 days after ART initiation and decreased to 86/100,000 person-years more than two years after ART initiation. Low current CD4 cell counts increased the risk of developing KS. Adults were more likely to develop KS than children, and men were more likely to develop KS than women.

This is one of the first reports to describe KS incidence rates in patients on ART in an African setting, and it is, to our knowledge, the first study to report KS incidence rates in HIV-infected African children on ART. We included more than 170’000 children and adults from four Southern African countries. The multi-cohort design of the study allowed us to evaluate prospectively collected information on KS cases and patient visits. Opportunistic infections and CD4 cell counts were reported regularly. CD4 cell count measurements at ART initiation were available for 85% of included patients, and WHO stages at ART start were recorded for 96% of the included participants.

However, our study was limited because we included only six of the 22 cohorts that participate in IeDEA-SA, and 87% of patients we included were drawn from the CIDRZ cohort in Zambia. Our findings are, therefore, mainly representative for Zambia, and to a lesser extent for Southern Africa as a region. Only cohorts in South Africa and Botswana collect HIV viral loads routinely. Therefore, we could not include HIV viral loads in our models. Because HHV-8 serology is generally not available, we could not assess the risk of developing KS among co-infected patients. In addition, KS is often only clinically diagnosed and not histologically confirmed. This might have led to misclassification of KS cases and consecutively an under- or overestimation of the KS incidence rate in our cohorts.

The incidence rate we estimated (in adult patients 173/100,000) is not far from incidence rates observed in adult HIV-infected patients on ART in Uganda (201/100,000), Kenya (270/100,000)8 and Switzerland (130/100,000),11 see Table 3. Fink et al. reported a substantially higher KS incidence rate (450/100,000 [95% CI 320–620]) in patients on ART in Central and South America,12 which might be explained by different definitions of incident KS cases. While Fink et al. included all KS cases that were diagnosed after ART initiation; we excluded KS cases that were diagnosed within the first month on ART as prevalent cases. Including all KS cases diagnosed after ART initiation as incident cases does not take into account potential delays in KS case ascertainment. A KS case diagnosed a few days after ART initiation might not be a true incident case, but rather a prevalent KS case which was diagnosed with a lag time. It has been shown that the KS incidence estimates decrease as the lag time accounted for increases.13 However, to date, no standard definition of incident KS exists and cut offs are chosen arbitrarily with lag times commonly ranging between 0 and 90 days.8;11;14 In our as in other studies KS incidence rate was highest within the first six months after ART initiation and declined steeply thereafter.15;16 The high KS incidence rate observed within the first six months on ART might partly be explained by prevalent cases which have been misclassified as incident cases, but also by unmasking immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome (IRIS).17 Once HIV-infected patients have been on ART for more than two years, KS incidence was relatively low (86/100,000 person-years). Of note, this relatively low incidence rate is still higher than the age standardized incidence rates of the most common cancers in the general populations of Zambia, Zimbabwe, South Africa, and Botswana combined, as estimated by GLOBOCAN 2012 (prostate cancer: 56.3/100,000 person-years, cervical cancer: 37.6/100,000 person-years).18

Table 3.

Kaposi sarcoma incidence rates in patients on ART in resource-rich and resource-limited regions.

| Authors | Cohort | Country | Calendar years |

Patients on ART |

KS incidence rate per 100, 000 pys |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Resource-rich regions | N | Children | Adults | |||

| Ledergerber 199931 |

SHCS | Switzerland | 1995 – 1999 | 2,410 | NR | 140 |

| Clifford 200514 | SHCS | Switzerland | 1985 – 2003 | NR | NR | 109 |

| Franceschi 200811 |

SHCS | Switzerland | 1984 – 2006 | NR | NR | 130 |

| Suárez-García 201313 |

CoRIS/ CoRIS-MD |

Spain | 1997 – 2008 | NR | NR | 199 |

| Carrieri 200332 | DMI-2 | France | 1996 – 2001 | 2,589 | NR | 122 |

| Lacombe 201316 |

FHDH-ANRS CO4 |

France, French overseas territories |

1992 – 2009 | 40,083 | NR | 137 |

| Mocroft 200033 | EuroSIDA | Europe, Israel | 1994 – 1999 | NR | NR | 700 |

| Lodi 201029 * | CASCADE | Europe, Australia, Canada |

1986 – 2006 | 4,199 | NR | 358 |

| Yanik 201315 | CNICS | USA | 1996 – 2011 | 11,485 | NR | 304 |

| Resource-limited regions | ||||||

| Fink 201112 | CCASAnet/ IeDEA |

Caribbean, Central and South America |

2007 – 2009 | 3,372 | NR | 450 |

| Asiimwe 20129 | HBAC | Uganda | 2003 – 2008 | 1,121 | NR | 340 |

| Martin 20128 | IeDEA | Uganda | 2008 – 2011 | NR | NR | 201 |

| Martin 20128 | IeDEA | Kenya | 2008 – 2011 | NR | NR | 270 |

| Current study | IeDEA | Southern Africa | 2004 – 2010 | 173,245 | 59 | 173 |

Adapted from Semeere et al 2012.4 CASCADE, Concerted Action of Seroconversion to AIDS and Death in Europe; CCASAnet, Caribbean, Central and South American network for HIV Research; CNICS, Centers for AIDS Research (CFAR) Network of Integrated Clinical Systems; CoRIS/CoRIS-MD, Spanish cohorts of naïve HIV-infected patients; DMI-2, longitudinal database of HIV-infected individuals followed at Nice University Hospital, France; EuroSIDA, Collection of European cohort studies; FHDH-ANRS CO4, The French Hospital Database on HIV; HBAC, Home-Based AIDS Care programme; IeDEA, International epidemiological Databases to Evaluate AIDS; SHCS, Swiss HIV Cohort Study. Estimates from different studies are adjusted for different variables. ART, antiretroviral therapy; NR, not reported; pys, person-years.

Includes only men who have sex with men.

Interestingly, we found that KS incidence rates increased with calendar year. We could not find a biological explanation for this unexpected trend, and hypothesize it is caused by more accurate and intensive diagnosis and reporting in more recent years. Estimated KS incidence rates in Zambia, Botswana, and South Africa were similar, while the incidence rate in Zimbabwe was lower. The lower incidence rate could reflect the lower HHV-8 seroprevalence of 35% reported in HIV-infected persons in Zimbabwe as compared to 50% HHV-8 seroprevalencein Zambia and South Africa.1;2 It could also be due to differences in KS diagnosing and recording between the included cohorts. However, the difference in the KS incidence rates between Zimbabwe and the other countries was not statistically significant. We found that KS incidence rates increased from childhood to adulthood, and plateaued around age 30. After age 60, KS incidence rate increased again, but this increase was not statistically significant and could be a spurious finding. An increase of KS incidence rate in older adults would be in line with a previous study,19 and could be explained by ageing, which is a risk factor for developing cancer in general, and acquiring HHV-8 infection in particular: population-based studies from Africa have shown that HHV-8 seroprevalence increases with age.20–22 The same trend was described in HIV-infected persons in Ghana.23 Men were at higher risk of developing KS than women, though we found no difference in the KS incidence rate between boys and girls. Most studies in Africa found HHV-8 seroprevalence to be only slightly higher in men than women.24–26 Other mechanisms, like direct and indirect effects of sex hormones27 and sex differences in immune response to HHV-8 infection, might play a role in KS development. We found no evidence for an association between TB and KS, which is in line with a previous study.28 Advanced WHO clinical stage was a risk factor for developing KS in the first six months after ART initiation but not thereafter. This finding might be explained by survival bias of those on ART for more than six months.

Unlike other studies,9;15 we found no clear association between CD4 cell counts at ART initiation and KS incidence rate. In patients with CD4 cell counts <350 cells/µl at ART start, KS risk decreased as CD4 cell counts at ART start increased. Surprisingly, patients who started ART at CD4 cell counts ≥350 cells/µl had a higher risk of developing KS than patients who started ART at CD4 cell counts <50 cells/µl. However, this finding may result from selection bias. At the time of this study, patients were eligible for ART if they presented at WHO stage IV or with CD4 cell counts <200 or 350 cells/µl (depending on the cohort and calendar year). Patients who started ART at CD4 counts ≥350 cells/µl must have had AIDS symptoms to qualify for ART. The condition that made these patients eligible for ART might also have increased their risk of developing KS. Likewise, patients with CD4 cell counts <50 cells/µl might have already developed KS at baseline, and thus might have been excluded as prevalent cases. However, even when we included all prevalent KS cases in a sensitivity analysis the observed pattern for the association between CD4 cell counts at ART start and KS incidence rates remained similar. Missing CD4 cell counts at ART start might have also introduced a selection bias. Very sick patients in advanced WHO clinical stages are more likely to start ART without a CD4 cell count measurement than patients with early stage disease. This was also the case for our sample: patients with missing CD4 cell counts at ART initiation were more likely to be in WHO clinical stages III/IV than patients with available CD4 cell counts (69% versus 60%). Finally, current CD4 cell counts, which might be less affected by selection biases, showed a clear decline in KS risk as CD4 cells counts increased. This finding is consistent with those of previous studies conducted in high-income19;29 and low-income settings.8 Because maintaining CD4 cell counts ≥500 cells/µl decreases the risk of developing KS, it seems likely that starting ART at CD4 cell counts <500 cells/µl – as recently recommended by the WHO30 – could further reduce the incident KS burden.

Despite ART, the incidence rate of KS in HIV-infected patients remains high, and is especially high within the first six months after ART initiation. The KS burden might be further reduced by early HIV testing and maintaining high CD4 cell counts.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This study was funded by NIAID (grant number U01AI069924) and also supported by NCI (grant number 5U01A1069924-05), the Swiss Bridge Foundation and the Swiss National Science Foundation (Ambizione-PROSPER grant PZ00P3_136620_3, Marie Heim-Vögtlin grant PMCDP3_145489). We acknowledge Kali Tal and Gilles Wandeler for their editorial and clinical comments and suggestions. Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute Of Allergy And Infectious Diseases of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number U01AI069924 (PI: Egger and Davies). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. IeDEA-SA Steering Group: Frank Tanser, Africa Centre for Health and Population Studies, University of Kwazulu-Natal, Somkhele, South Africa; Christopher Hoffmann, Aurum Institute for Health Research, Johannesburg, South Africa; Benjamin Chi, Centre for Infectious Disease Research in Zambia, Lusaka, Zambia; Denise Naniche, Centro de Investigação em Saúde de Manhiça, Manhiça, Mozambique; Robin Wood, Desmond Tutu HIV Centre (Gugulethu and Masiphumelele clinics), Cape Town, South Africa; Kathryn Stinson, Khayelitsha ART Programme and Médecins Sans Frontières, Cape Town, South Africa; Geoffrey Fatti, Kheth’Impilo Programme, South Africa; Sam Phiri, Lighthouse Trust Clinic, Lilongwe, Malawi; Janet Giddy, McCord Hospital, Durban, South Africa; Cleophas Chimbetete, Newlands Clinic, Harare, Zimbabwe; Kennedy Malisita, Queen Elizabeth Hospital, Blantyre, Malawi; Brian Eley, Red Cross War Memorial Children’s Hospital and Department of Paediatrics and Child Health, University of Cape Town, Cape Town, South Africa; Michael Hobbins, SolidarMed SMART Programme, Pemba Region, Mozambique; Kamelia Kamenova, SolidarMed SMART Programme, Masvingo, Zimbabwe; Matthew Fox, Themba Lethu Clinic, Johannesburg, South Africa; Hans Prozesky, Tygerberg Academic Hospital, Stellenbosch, South Africa; Karl Technau, Empilweni Clinic, Rahima Moosa Mother and Child Hospital, Johannesburg, South Africa; Shobna Sawry, Harriet Shezi Children’s Clinic, Chris Hani Baragwanath Hospital, Soweto, South Africa.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest:

None of the authors has any conflict of interest to declare.

- Annual Meeting of American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO), Chicago, June 3–7, 2011.

- International Conference on Malignancies in AIDS and Other Acquired Immunodeficiencies (ICMAOI), Bethesda, Maryland, November 7–8, 2011.

Reference List

- 1.Campbell TB, Borok M, Ndemera B, et al. Lack of evidence for frequent heterosexual transmission of human herpesvirus 8 in Zimbabwe. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;48:1601–1608. doi: 10.1086/598978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Maskew M, MacPhail AP, Whitby D, et al. Prevalence and predictors of kaposi sarcoma herpes virus seropositivity: a cross-sectional analysis of HIV-infected adults initiating ART in Johannesburg, South Africa. Infect Agent Cancer. 2011;6:22. doi: 10.1186/1750-9378-6-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.UNAIDS. Country reports. Geneva, Switzerland: UNAIDS; 2012. Available at: http://www.unaids.org/en/regionscountries/countries/ [Google Scholar]

- 4.Semeere AS, Busakhala N, Martin JN. Impact of antiretroviral therapy on the incidence of Kaposi's sarcoma in resource-rich and resource-limited settings. Curr Opin Oncol. 2012;24:522–530. doi: 10.1097/CCO.0b013e328355e14b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bohlius J, Valeri F, Maskew M, et al. Kaposi's Sarcoma in HIV-infected patients in South Africa: Multicohort study in the antiretroviral therapy era. Int J Cancer. 2014 doi: 10.1002/ijc.28894. Epub 2 May 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Semeere A, Wenger M, Busakhala N, et al. Applying the Methods of Causal Inference to HIV-Associated Malignancies: Estimation of the Impact of Antiretroviral Therapy on Kaposi’s Sarcoma Incidence in East Africa via a Nested New User Cohort Analysis. Presented at: 14th International Conference on Malignancies in AIDS and Other Acquired Immunodeficiencies; 12–13 November 2013; Bethesda, Maryland. [Google Scholar]

- 7.UNAIDS. Regional fact sheet 2012: Sub-Saharan Africa - AIDS epidemic facts and figures. Geneva, Switzerland: UNAIDS; 2012. Available at: http://www.unaids.org/en/media/unaids/contentassets/documents/epidemiology/2012/gr2012/2012_FS_regional_ssa_en.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Martin J, Wenger M, Busakhala N, et al. Prospective evaluation of the impact of potent antiretroviral therapy on the incidence of Kaposi's Sarcoma in East Africa: Findings from the International Epidemiologic Databases to Evaluate AIDS(IeDEA) Consortium. Infect Agent Cancer. 2012;7(SUPPL. 1) [Google Scholar]

- 9.Asiimwe F, Moore D, Were W, et al. Clinical outcomes of HIV-infected patients with Kaposi's sarcoma receiving nonnucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor-based antiretroviral therapy in Uganda. HIV Med. 2012;13:166–171. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1293.2011.00955.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Egger M, Ekouevi DK, Williams C, et al. Cohort Profile: The international epidemiological databases to evaluate AIDS(IeDEA) in sub-Saharan Africa. Int J Epidemiol. 2012;41:1256–1264. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyr080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Franceschi S, Maso LD, Rickenbach M, et al. Kaposi sarcoma incidence in the Swiss HIV Cohort Study before and after highly active antiretroviral therapy. Br J Cancer. 2008;99:800–804. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6604520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fink VI, Shepherd BE, Cesar C, et al. Cancer in HIV-infected persons from the Caribbean, Central and South America. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2011;56:467–473. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31820bb1c3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Suarez-Garcia I, Jarrin I, Iribarren JA, et al. Incidence and risk factors of AIDS-defining cancers in a cohort of HIV-positive adults: Importance of the definition of incident cases. Enferm Infecc Microbiol Clin. 2013;31:304–312. doi: 10.1016/j.eimc.2012.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Clifford GM, Polesel J, Rickenbach M, et al. Cancer risk in the Swiss HIV Cohort Study: associations with immunodeficiency, smoking, and highly active antiretroviral therapy. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2005;97:425–432. doi: 10.1093/jnci/dji072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yanik EL, Napravnik S, Cole SR, et al. Incidence and timing of cancer in HIV-infected individuals following initiation of combination antiretroviral therapy. Clin Infect Dis. 2013;57:756–764. doi: 10.1093/cid/cit369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lacombe JM, Boue F, Grabar S, et al. Risk of Kaposi sarcoma during the first months on combination antiretroviral therapy. AIDS. 2013;27:635–643. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32835cba6c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Letang E, Miro JM, Nhampossa T, et al. Incidence and predictors of immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome in a rural area of Mozambique. PLoS One. 2011;6:e16946. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0016946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Ervik M, et al. GLOBOCAN 2012 v1.0, Cancer Incidence and Mortality Worldwide: IARC CancerBase No. 11 [Internet] Lyon, France: International Agency for Research on Cancer; 2013. Available from: http://globocan.iarc.fr. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Guiguet M, Kendjo E, Carcelain G, et al. CD4+ T-cell percentage is an independent predictor of clinical progression in AIDS-free antiretroviral-naive patients with CD4+ T-cell counts >200 cells/mm3. Antivir Ther. 2009;14:451–457. doi: 10.1177/135965350901400311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Plancoulaine S, Abel L, van Beveren M, et al. Human herpesvirus 8 transmission from mother to child and between siblings in an endemic population. Lancet. 2000;356:1062–1065. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)02729-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mbulaiteye SM, Pfeiffer RM, Whitby D, et al. Human herpesvirus 8 infection within families in rural Tanzania. J Infect Dis. 2003;187:1780–1785. doi: 10.1086/374973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Butler LM, Were WA, Balinandi S, et al. Human herpesvirus 8 infection in children and adults in a population-based study in rural Uganda. J Infect Dis. 2011;203:625–634. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiq092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nuvor SV, Katano H, Ampofo WK, et al. Higher prevalence of antibodies to human herpesvirus 8 in HIV-infected individuals than in the general population in Ghana, West Africa. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2001;20:362–364. doi: 10.1007/s100960100517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dollard SC, Butler LM, Jones AM, et al. Substantial regional differences in human herpesvirus 8 seroprevalence in sub-Saharan Africa: insights on the origin of the "Kaposi's sarcoma belt". Int J Cancer. 2010;127:2395–2401. doi: 10.1002/ijc.25235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Malope BI, MacPhail P, Mbisa G, et al. No evidence of sexual transmission of Kaposi's sarcoma herpes virus in a heterosexual South African population. AIDS. 2008;22:519–526. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3282f46582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Newton R, Ziegler J, Bourboulia D, et al. The sero-epidemiology of Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus(KSHV/HHV-8) in adults with cancer in Uganda. Int J Cancer. 2003;103:226–232. doi: 10.1002/ijc.10817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ziegler JL, Katongole-Mbidde E, Wabinga H, et al. Absence of sex-hormone receptors in Kaposi's sarcoma. Lancet. 1995;345:925. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(95)90039-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fenner L, Reid SE, Fox MP, et al. Tuberculosis and the risk of opportunistic infections and cancers in HIV-infected patients starting ART in Southern Africa. Trop Med Int Health. 2013;18:194–198. doi: 10.1111/tmi.12026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lodi S, Guiguet M, Costagliola D, et al. Kaposi sarcoma incidence and survival among HIV-infected homosexual men after HIV seroconversion. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2010;102:784–792. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djq134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.World Health Organization. Consolidated guidelines on the use of antiretroviral drugs for treating and preventing HIV infection: Recommendations for a public health approach. 2013 Available at: http://www.who.int/hiv/pub/guidelines/arv2013/en/ [PubMed]

- 31.Ledergerber B, Egger M, Erard V, et al. AIDS-related opportunistic illnesses occurring after initiation of potent antiretroviral therapy: the Swiss HIV Cohort Study. JAMA. 1999;282:2220–2226. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.23.2220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Carrieri MP, Pradier C, Piselli P, et al. Reduced incidence of Kaposi's sarcoma and of systemic non-hodgkin's lymphoma in HIV-infected individuals treated with highly active antiretroviral therapy. Int J Cancer. 2003;103:142–144. doi: 10.1002/ijc.10790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mocroft A, Katlama C, Johnson AM, et al. AIDS across Europe, 1994–98: the EuroSIDA study. Lancet. 2000;356:291–296. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(00)02504-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.