Abstract

Objective

To provide new evidence on whether and how patterns of health care utilization deviate from horizontal equity in a country with a universal and egalitarian public health care system: Italy.

Data Sources

Secondary analysis of data from the Health Conditions and Health Care Utilization Survey 2005, conducted by the Italian National Institute of Statistics on a probability sample of the noninstitutionalized Italian population.

Study Design

Using multilevel logistic regression, we investigated how the probability of utilizing five health care services varies among individuals with equal health status but different SES.

Data Collection/Extraction

Respondents aged 18 or older at the interview time (n = 103,651).

Principal Findings

Overall, we found that use of primary care is inequitable in favor of the less well-off, hospitalization is equitable, and use of outpatient specialist care, basic medical tests, and diagnostic services is inequitable in favor of the well-off. Stratifying the analysis by health status, however, we found that the degree of inequity varies according to health status.

Conclusions

Despite its universal and egalitarian public health care system, Italy exhibits a significant degree of SES-related horizontal inequity in health services utilization.

Keywords: Health care utilization, horizontal equity, SES inequity, Italy

A basic tenet of most modern democracies is that access to health care should be equitable; that is, all citizens should be granted equal opportunity to receive adequate health care—when needed—regardless of their personal characteristics, such as gender, age, race, ethnicity, and socioeconomic status (Daniels 1985; Ruger 2009). This egalitarian principle, known as horizontal equity, can be summarized in the following rule: equal access for equal need. In other words, according to the principle of horizontal equity, access to and receipt of health care should depend exclusively on need, rather than factors like ability to pay, membership in a particular social group, or possession of specific attributes (Aday and Andersen 1974; Le Grand 1987; Whitehead 1992; Culyer and Wagstaff 1993; Braveman 2006).

Although horizontal equity is a primary goal of many health care systems, its full realization can be hampered in several ways. Most research in this area has focused on the barriers to equity posed by disparities in socioeconomic status (SES), showing that a certain degree of pro-rich horizontal inequity of access to health care exists in many countries all around the world (e.g., Van Doorslaer, Masseria, and the OECD Health Equity Research Group Members 2004; Cissé, Luchini, and Moatti 2007; Lu et al. 2007; Balsa, Rossi, and Triunfo 2011). As horizontal inequity is seen as a major limitation to improving population health (WHO 2010), the extent to which it manifests itself is generally considered a key indicator of the performance of any health care system (Allin, Hernández-Quevedo, and Masseria 2009).

In this vein, the purpose of this study was to investigate whether and how patterns of access to health care deviate from the ideal of horizontal equity in a country with a universal and egalitarian public health care system: Italy. The Italian National Health Service (Servizio Sanitario Nazionale—SSN) was established in 1978 through a major reform largely inspired by the British NHS, with the declared goal of providing uniform and comprehensive care to all Italian citizens (France, Taroni, and Donatini 2005). The reform rested on the egalitarian principle that health care should be financed according to ability to pay—through general taxation—but distributed according to need, thereby setting out equity objectives in terms of both financial contribution and access to care. The SSN provides a wide array of services, including primary care through independent contracted physicians (general practitioners, GPs), outpatient specialist care, inpatient hospital care, and diagnostic services. GP visits and inpatient hospital care are free at the point of delivery for all patients; on the other hand, a small flat rate copayment is required for specialist visits and diagnostic services—although full or partial exemptions exist for several categories of patients. With some exceptions, access to specialist visits is regulated by GPs, who then act as gatekeepers. Likewise, diagnostic tests must be prescribed either by a GP or by a specialist physician.

Despite the universal and comprehensive character of the SSN, many Italian citizens seek health care from private providers that can be accessed without a referral from the SSN GP or the prescription of a SSN specialist. According to the latest available data from the Italian National Institute of Statistics (Istat 2007), 92 percent of dentist visits and 48 percent of all other specialist visits were paid out-of-pocket in 2005. Use of private providers for diagnostic services was lower but still substantial (21 percent). On the other hand, only 5 percent of hospital admissions and 4 percent of GP visits were paid out-of-pocket. The main reported reason for using private health services—instead of SSN services—was greater confidence in the provider (physician or health facility), followed by avoidance of long waiting lists and better accessibility.

The above picture of the SSN generates conflicting expectations about SES-related inequity of access to health care in Italy. The egalitarian principles underlying the SSN, as well as its ability to ensure universal and inexpensive (if not free) access to a comprehensive package of health services, suggest that achieving horizontal equity should not be an issue. Conversely, the preference of many Italian citizens for private (and relatively expensive) providers of outpatient specialist care and diagnostic services indicates that some degree of pro-rich horizontal inequity might be expected in the access to these two forms of health care.

In this regard, previous research has reached mixed conclusions. On one hand, there is a general consensus that access to outpatient specialist care is inequitable in favor of the well-off (Atella et al. 2004; Van Doorslaer, Koolman, and Jones 2004; Van Doorslaer, Masseria, and the OECD Health Equity Research Group Members 2004; Allin, Masseria, and Mossialos 2009; Bago d'Uva and Jones 2009; Masseria and Giannoni 2010). On the other hand, researchers are at odds over equity of access to GP visits and inpatient hospital care. Specifically, use of primary care was found inequitable in favor of the worse-off by some authors (Atella et al. 2004), equitable by others (Van Doorslaer, Koolman, and Jones 2004; Van Doorslaer, Masseria, and the OECD Health Equity Research Group Members 2004; Bago d'Uva and Jones 2009), and inequitable in favor of the well-off by still some others (Masseria and Giannoni 2010). Likewise, hospitalization was found sometimes equitable (Van Doorslaer, Koolman, and Jones 2004; Masseria and Giannoni 2010), and some other times inequitable in favor of the well-off (Masseria and Paolucci 2005).

To clarify these uncertainties, in this study, we present new evidence on horizontal inequity of access to health care in Italy. Using large-scale survey data collected by the Italian National Institute of Statistics in 2005, we investigate whether and how the probability of accessing a comprehensive set of health care services varies among individuals with equal need but different SES. As regards to access, we follow Aday and Andersen's (1974, 1975, 1981) distinction between potential and realized access to health care. In their view, having access denotes a potential to utilize health services if required (service availability), while gaining access refers to the initiation into the process of actually utilizing a service. An individual in need may have access to services but, at the same time, have difficulties in utilizing them; in other words, potential access is not always converted into realized access (Aday and Andersen 1981). In this study, we focus on realized access to health care; that is, we analyze patterns of utilization of selected health care services.

The term “need” also requires some clarification. The concept of “need for health care” is rather ambiguous (Culyer 1995), but many of its definitional problems are difficult to tackle, especially in empirical research (Goddard and Smith 2001). In practice, most researchers proxy need for health care by some measure of health status (O'Donnell et al. 2008). In this study, we follow this approach and use self-rated health status as a proxy measure of need.

This study contributes to research on horizontal equity of access to health care in several ways. First, we provide the most up-to-date and comprehensive account of the Italian case so far: on one hand, we base our analysis on the most recent data available on this topic; on the other hand, we consider not only the standard indicators of access to health care (GP visits, specialist visits, and hospitalization) but also two additional indicators generally neglected in previous research: regular undertaking of basic medical tests (cholesterol level, glucose level, and blood pressure) and utilization of diagnostic services. As a proper use of such services can reduce the risk of morbidity and mortality, their inclusion in the analysis of horizontal inequity sheds further light on this phenomenon.

Second, we describe and quantitate horizontal inequity using a full range of model-based predicted probabilities of health services utilization, rather than the commonly used horizontal inequity index (O'Donnell et al. 2008). Being a unit-free measure that takes values in the interval [0,1], the horizontal inequity index facilitates comparative analysis but completely hides the absolute levels of health services utilization, thereby making for limited—and somewhat opaque—descriptions of the phenomenon. On the other hand, model-based predicted probabilities represent the association between SES and health care utilization in a fully transparent way, providing a clear and complete picture of horizontal inequity.

Finally, along with the global estimates of horizontal inequity usually found in the literature, we present the results of a stratified analysis that provides distinct estimates of inequity for each level of health status, thus allowing for a more detailed description of the phenomenon and its possible heterogeneity. To our knowledge, this is the first application of this kind of analysis in the study of horizontal inequity of access to health care.

Data, Variables, and Methods

Data

The data used in this study come from the latest edition of the Indagine sulle condizioni di salute e il ricorso ai servizi sanitari [Health Conditions and Health Care Utilization Survey], a large-scale sample survey conducted every 5/6 years by the Italian National Institute of Statistics to collect detailed information on several topics relevant to health policy (Istat 2006). The information of interest was gathered through personal interviews with a nationally representative, stratified, multistage probability sample of the noninstitutionalized Italian population; a total of 128,040 interviews were successfully completed between December 2004 and September 2005. For the purposes of this study, we restricted our analysis to respondents aged 18 or older at the interview time; after this limitation, our study sample includes 103,651 individuals belonging to 50,106 families.

Health Care Utilization

We analyzed five binary indicators of respondents' utilization of health care services, all resulting from self-reported information. (1) General practitioner visits takes value 1 if respondents visited a GP (primary care physician) in the 4 weeks before the interview, and value 0 otherwise; (2) Specialist visits takes value 1 if respondents visited a specialist physician of any kind in the 4 weeks before the interview, and value 0 otherwise; (3) Basic medical tests takes value 1 if respondents reported to check their cholesterol level, glucose level, and blood pressure at least once a year, and value 0 otherwise; (4) Diagnostic tests takes value 1 if respondents underwent one or more outpatient diagnostic tests (blood test, urinalysis, X-ray, echography, MRI, CT scan, echo Doppler, echocardiogram, ECG, EEG, mammography, pap-test, other) in the 4 weeks before the interview, and value 0 otherwise; and (5) Hospitalization takes value 1 if respondents had one or more episodes of inpatient hospital care in the 3 months before the interview, and value 0 otherwise.

Socioeconomic Status

To maximize the statistical power of our analyses, ideally we would have measured SES using a standard quantitative variable, like income or occupational prestige. As no such measure was available in our dataset, we created our own SES index. To this aim, we adopted a two-step procedure that mirrors—though on a smaller scale—the one underlying most existing SES indices. First, we defined an exhaustive set of 30 socioeconomic positions corresponding to each possible combination of two variables, each representing a relevant source of SES: labor market position (self-employed professionals, entrepreneurs, petty bourgeoisie, senior managers, junior managers, other white collars, manual and service workers, unemployed, students, other nonemployed) and educational level (up to middle school degree, high school degree, college degree, or higher). Second, using an external dataset collected by the Bank of Italy (Banca d'Italia 2008), we attributed to each of these positions a score proportional to the median equivalized net disposable income received by individuals in that position. For ease of interpretation, the 30 SES scores thus obtained were linearly transformed to a scale of 0 to 100, where 0 corresponds to poorly educated and unemployed, and 100 corresponds to senior managers with a college degree or higher.

Need for Health Care

Respondents' potential need for health care was measured by three levels of self-rated health status (good, fair, poor) derived from the PCS-12, that is, the physical component summary scale of the standard version (4-week recall) of the 12-item short form (SF-12) health survey (Ware, Kosinski, and Keller 1996). Given the negatively skewed distribution of PCS-12 in the study sample, the three levels of health status were obtained by dividing such distribution into three equal-length intervals—approximately 11 to <31, 31 to <50, and 50–69—corresponding, respectively, to poor health (7 percent of the study sample), fair health (25 percent), and good health (68 percent).

Control Variables

Three additional categorical variables were used as controls when estimating the association between SES and health care utilization: sex, age group (18–24, 25–29, 30–39, 40–49, 50–59, 60–64, 65–69, 70–74, 75–79, 80+ years), and type of municipality of residence (metropolitan area–main city, metropolitan area–suburbs, nonmetropolitan area–up to 2,000 residents, nonmetropolitan area–2,001–10,000 residents, nonmetropolitan area–10,001–50,000 residents, nonmetropolitan area–more than 50,000 residents). Appendix Table SA1 reports basic descriptive statistics for all the variables employed in the analysis.

Analysis

Due to the multistage sampling design used to collect the data analyzed herein, and considering the binary nature of the response variables, to estimate the net association between SES and health services utilization, we used a set of three-level multilevel logistic regression models (Subramanian, Jones, and Duncan 2003; Gelman and Hill 2007) with a structure of 103,651 individuals, nested within 50,106 families, nested within 20 regions. For each response variable, we carried out two analyses: a global analysis and a stratified analysis.

The global analysis involves the entire study sample and treats health status as a standard control variable. The corresponding regression model is represented as follows:

where πijk denotes the probability of using a given health service for individual i belonging to family j and residing in region k; xijk denotes the value taken by the SES index on individual ijk; w1ijk and w2ijk denotes the values taken by the binary regressors representing health status on individual ijk; zmijk denotes the values taken by the M binary regressors representing the control variables on individual ijk; ζjk denotes the level-2 random effects; and ζk denotes the level-3 random effects. As we can see, the association between SES and health service utilization is specified as  , which clearly denotes a quadratic functional form. This form was chosen after an extensive exploratory analysis showing that the associations of interest could be reasonably represented either as (approximately) linear or as (approximately) quadratic.

, which clearly denotes a quadratic functional form. This form was chosen after an extensive exploratory analysis showing that the associations of interest could be reasonably represented either as (approximately) linear or as (approximately) quadratic.

To provide a more detailed account of horizontal inequity and its possible heterogeneity, we complemented the global analysis with a stratified analysis aimed at describing whether and how the association between SES and health service utilization varies by health status. To this purpose, we divided the study sample into three strata—one for each level of health status—and estimated the association of interest within each stratum. The regression model we used in the stratified analysis equals the one specified for the global analysis, with the obvious exception that, in the stratified analysis, the terms representing health status (δ1w1ijk + δ2w2ijk) are omitted.

To present the results of each regression model, we calculated a proper set of predictive margins (Lane and Nelder 1982; Graubard and Korn 1999). To this aim, we followed a two-step procedure. First, for each value x of SES and each combination c of values of the control variables, we computed the median predicted probability (Skrondal and Rabe-Hesketh 2009) of using health service Y:

Second, for each value x of SES, we computed the marginal median predicted probability of using health service Y net of the control variables:

where C denotes the number of possible combinations of values of the control variables; wc denotes the relative frequency of combination c in a standard population;  ; and the weighted study sample is used as the standard population.

; and the weighted study sample is used as the standard population.

For each regression model, we summarized the magnitude of horizontal inequity using a measure of the kind “ratio of high versus low” (Mackenbach and Kunst 1997), which we called the inequity ratio and defined as  , where

, where  denotes the marginal median predicted probability of using a given health service for individuals with SES = 80, and

denotes the marginal median predicted probability of using a given health service for individuals with SES = 80, and  denotes the analogous probability for individuals with SES = 20.

denotes the analogous probability for individuals with SES = 20.

All regression parameters were estimated using an MCMC-based Bayesian approach with vague priors (Gelman and Hill 2007). Accordingly, results are presented using proper functions of the posterior distribution of interest. Specifically, point estimates correspond to the mean of the posterior distribution; 95 percent confidence limits correspond to the 2.5th and 97.5th percentiles of the posterior distribution; and 50 percent confidence limits correspond to the 25th and 75th percentiles of the posterior distribution. Estimation and data analysis were carried out using the statistical packages MlwiN 2.26 (Browne 2012; Rasbash et al. 2012) and Stata 12.1 (StataCorp 2011), integrated via the user-written Stata command runmlwin (Leckie and Charlton 2013). For each regression model, Appendix Table SA2 reports mean and standard deviation of the posterior distribution of the main regression coefficients of interest.

Results

Global Analysis

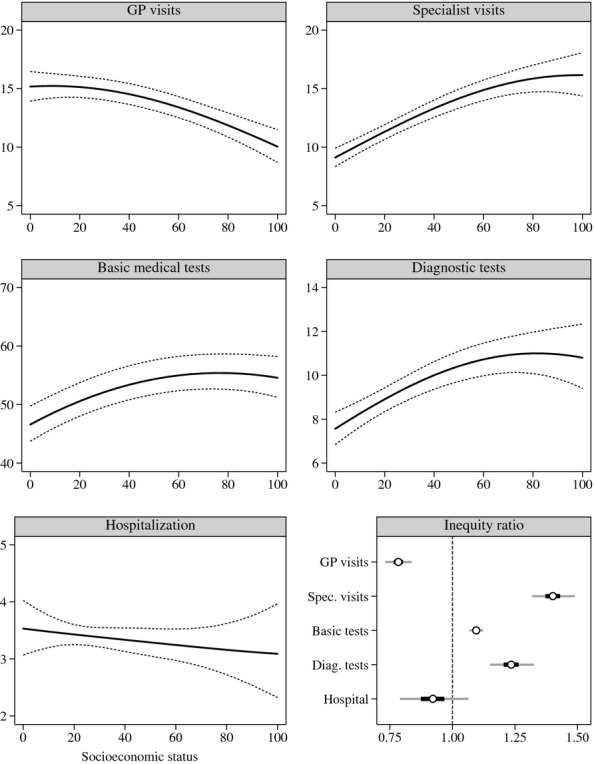

Use of primary care exhibits a negative association with SES (Figure1). Expressly, after controlling for health status and the sociodemographic covariates, the probability to visit a GP decreases with SES. For example, the point estimate of the marginal median predicted probability of having a GP visit is 15.1 percent among individuals with SES = 20, but it drops to 11.9 percent among subjects with SES = 80. This amounts to an inequity ratio of 0.78 (95 percent CI: 0.73–0.84), indicating that access to primary care is inequitable in favor of the less well-off.

Figure 1.

Global Analysis—For Each Health Care Service, the Figure Displays (a) the Marginal Median Predicted Probability (percent) of Utilization by SES: Point Estimates (Solid Lines) and 95 percent Confidence Limits (Dashed Lines); and (b) the Inequity Ratio: Point Estimate (White Circle), 50 percent Confidence Limits (Dark Gray Line), and 95 percent Confidence Limits (Light Gray Line)

Conversely, the global association between SES and specialist visits is positive (Figure1). This association is relatively strong: as indicated by the inequity ratio (ω = 1.40, 95 percent CI: 1.32–1.49), the point estimate of the marginal median predicted probability of having a specialist visit is—ceteris paribus—40 percent higher among individuals with SES = 80 than among subjects with SES = 20. Thus, access to outpatient specialist care is substantially inequitable in favor of the well-off.

A certain degree of prorich inequity is exhibited also by utilization of basic medical tests and outpatient diagnostic services (Figure1). In the former case, the magnitude of inequity appears moderate (ω = 1.10, 95 percent CI: 1.07–1.12), whereas in the latter, it reaches an appreciable level (ω = 1.24, 95 percent CI: 1.15–1.33).

Finally, access to inpatient hospital care appears evenly distributed among the Italian adult population (Figure1): overall, the association between SES and hospitalization is weak and statistically nonsignificant (ω = 0.92, 95 percent CI: 0.79–1.06).

Stratified Analysis

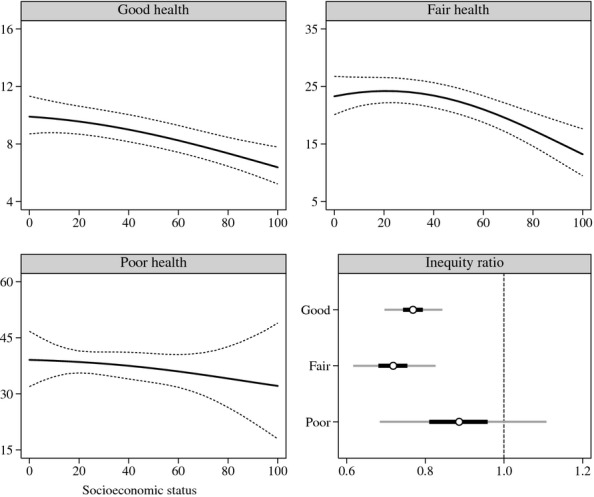

The stratified analysis by health status reveals some interesting patterns of heterogeneity in inequity of access to health services. Starting with primary care utilization, we can see that its association with SES is not constant but varies somewhat across levels of health status (Figure2). Specifically, the association appears clearly negative and of similar magnitude among individuals in good health (ω1 = 0.77, 95 percent CI: 0.70–0.84) and fair health (ω2 = 0.72, 95 percent CI: 0.62–0.83), but it becomes weaker and not significantly different from null among subjects in poor health (ω3 = 0.89, 95 percent CI: 0.68–1.11).

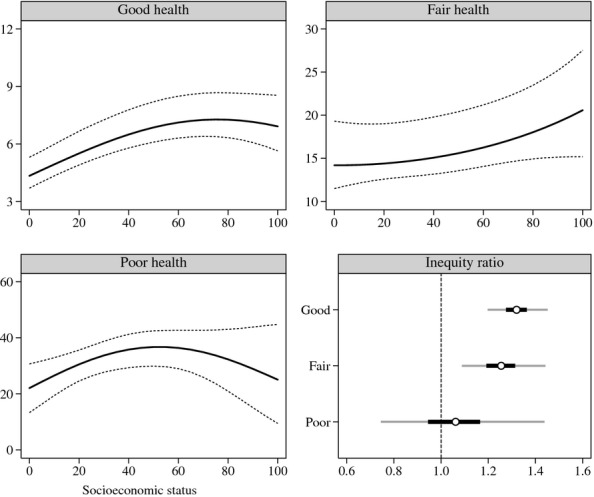

Figure 2.

Stratified Analysis of GP Visits—For Each Level of Health Status, the Figure Displays (a) the Marginal Median Predicted Probability (percent) of Utilization by SES: Point Estimates (Solid Lines) and 95 percent Confidence Limits (Dashed Lines); and (b) the Inequity Ratio: Point Estimate (White Circle), 50 percent Confidence Limits (Dark Gray Line), and 95 percent Confidence Limits (Light Gray Line)

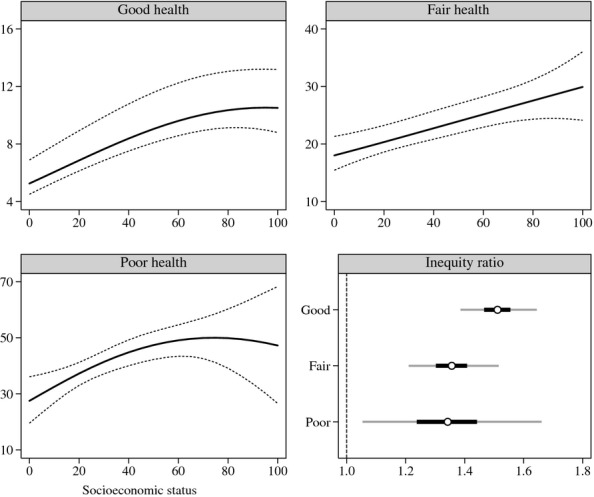

A trend toward equity—though beginning from the opposite side—emerges also from the stratified analysis of outpatient specialist care (Figure3). In this case, the point estimate of the inequity ratio appears to decrease monotonically with worsening of health status, going from ω1 = 1.51 (95 percent CI: 1.39–1.64) among individuals in good health, to ω2 = 1.36 (95 percent CI: 1.21–1.52) among those in fair health, to ω3 = 1.34 (95 percent CI: 1.05–1.66) among those in poor health. Uncertainty around point estimates, however, suggests that this trend might be an artifact of sampling error. To clarify this issue, we carried out two tests of monotonicity based on posterior distribution analysis. First, we tested strict monotonicity by computing the posterior probability of (ω1 > ω2)∧(ω2 > ω3). Second, we tested a weaker version of monotonicity according to which ω1 is greater than both ω2 and ω3; ω2 is not necessarily greater than ω3—formally: (ω1 > ω2)∧(ω1 > ω3). Assuming independence among the posterior distributions of the three inequity ratios ω1, ω2, and ω3, the posterior probability of strict monotonicity is 49 percent, while the posterior probability of weak monotonicity is 80 percent. Thus, although the hypothesis of strict monotonicity is maximally uncertain, the available evidence provides significant support for weak monotonicity, allowing us to conclude that pro-rich inequity in utilization of outpatient specialist care is very likely to decrease when health status is less than good.

Figure 3.

Stratified Analysis of Outpatient Specialist Visits—For Each Level of Health Status, the Figure Displays (a) the Marginal Median Predicted Probability (percent) of Utilization by SES: Point Estimates (Solid Lines) and 95 percent Confidence Limits (Dashed Lines); and (b) the Inequity Ratio: Point Estimate (White Circle), 50 percent Confidence Limits (Dark Gray Line), and 95 percent Confidence Limits (Light Gray Line)

Similar conclusions about decreasing inequity can be drawn from the analysis of basic medical tests and outpatient diagnostic services. As regards basic medical tests (Figure4), the inequity ratio drops from ω1 = 1.15 (95 percent CI: 1.12–1.19) among individuals in good health, to ω2 = 1.01 (95 percent CI: 0.95–1.06) among those in fair health, to ω3 = 0.92 (95 percent CI: 0.80–1.04) among those in poor health. In this case, we do not need to carry out a formal test of monotonicity to conclude that use of basic medical tests is inequitable in favor of the well-off among individuals in good health but becomes essentially equitable among those in fair and poor health.

Figure 4.

Stratified Analysis of Basic Medical Tests—For Each Level of Health Status, the Figure Displays (a) the Marginal Median Predicted Probability (percent) of Utilization by SES: Point Estimates (Solid Lines) and 95 percent Confidence Limits (Dashed Lines); and (b) the Inequity Ratio: Point Estimate (White Circle), 50 percent Confidence Limits (Dark Gray Line), and 95 percent Confidence Limits (Light Gray Line)

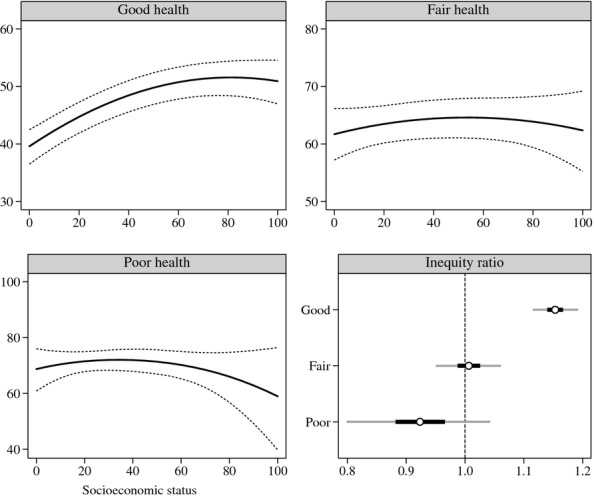

The case of diagnostic tests is somewhat less clear-cut (Figure5). As in the case of specialist visits, the point estimate of the inequity ratio decreases monotonically with worsening of health status, going from ω1 = 1.32 (95 percent CI: 1.20–1.45), to ω2 = 1.25 (95 percent CI: 1.09–1.44), to ω3 = 1.06 (95 percent CI: 0.74–1.44). However, uncertainty around point estimates requires that we test the plausibility of the observed trend. In this case, along with strict monotonicity, we tested a hypothesis of weak monotonicity according to which ω3 is less than both ω1 and ω2, but ω2 is not necessarily less tha ω1—formally: (ω3 < ω1)∧(ω1 > ω2). Based on the available evidence, the posterior probability of strict monotonicity is 59 percent, while the posterior probability of weak monotonicity is 83 percent. Thus, we can conclude that pro-rich inequity in utilization of outpatient diagnostic services is very likely to become null among people in poor health.

Figure 5.

Stratified Analysis of Outpatient Diagnostic Tests—For Each Level of Health Status, the Figure Displays (a) the Marginal Median Predicted Probability (percent) of Utilization by SES: Point Estimates (Solid Lines) and 95 percent Confidence Limits (Dashed Lines); and (b) the Inequity Ratio: Point Estimate (White Circle), 50 percent Confidence Limits (Dark Gray Line), and 95 percent Confidence Limits (Light Gray Line)

Finally, the stratified analysis of inpatient hospital care (results not reported here) shows that access to hospitalization is essentially equitable regardless of health status.

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to investigate whether and how patterns of access to health services deviate from horizontal equity in a country with a universal and egalitarian public health care system: Italy. After observing that previous research on this topic has reached somewhat contradictory conclusions, we set out to provide new evidence based on the analysis of data drawn from a sample survey conducted in the mid 2000s. Specifically, we focused on SES-related horizontal inequity and examined whether and how the probability of utilizing a comprehensive set of health services varies among individuals with equal need but different SES. In addition to the usual estimation of global levels of horizontal inequity, we carried out a stratified analysis aimed at providing distinct estimates of inequity for each level of health status, thereby allowing for a more detailed description of the phenomenon of interest and its possible heterogeneity.

Overall, the results of this study confirm a well-established finding in the international literature on health care: even countries with a universal and egalitarian public health care system, like Italy, exhibit a certain degree of SES-related horizontal inequity in health services utilization (Van Doorslaer, Wagstaff, and Rutten 1993; Van Doorslaer, Masseria, and the OECD Health Equity Research Group Members 2004; Hanratty, Zhang, and Whitehead 2007). Specifically, we found a significant amount of pro-rich inequity in the utilization of specialist care, diagnostic services, and basic medical tests. Use of primary care was found inequitable, too, but in favor of the less well-off. Finally, we found that hospitalization is essentially equitable.

Equity in the use of inpatient hospital care was of no surprise, considering that in the Italian SSN, hospitalization is free at the point of delivery for all patients, and only a small fraction of hospital admissions (around 5 percent) is paid out-of-pocket. Likewise, the existence of a certain amount of prorich inequity in the use of specialist care and diagnostic tests was to be expected, basically for two reasons. First, access to these services requires a flat rate copayment; although this contribution is small and several categories of patients are exempted from its payment, its presence may hold lower income citizens back from seeking specialist and diagnostic care, especially when need is not apparent (Rebba 2009). Second, and foremost, some sectors of the SSN, especially in the southern regions of the country, provide low-quality services and/or are plagued by long waiting lists (Lo Scalzo et al. 2009). Such negative features inhibit the demand of citizens for public health services, leading them to turn to private health care (Rebba 2009; Baldini and Turati 2012). The ability to pay for private health services, however, is not equally distributed but increases with SES (Atella et al. 2004; Baldini and Turati 2012). Therefore, all else being equal, the total level of utilization of specialist and diagnostic care is expected to be positively associated with SES, giving rise to a certain amount of prorich inequity of access to these services.

The significant—though moderate—level of prorich inequity in the use of basic medical tests cannot be attributed directly to income-based SES disparities, as these tests are inexpensive and easily accessible. However, such inequity might easily arise from SES disparities in terms of cultural capital. Expressly, several studies have found that education is positively associated with health literacy which, in turn, affects the probability of using health services, especially those—like basic medical tests—related to prevention (Bennett et al. 2009; Berkman et al. 2011). This finding has relevant policy implications, as it suggests that the SSN should dedicate more (or better) resources to health promotion among low-educated groups, especially in the fields of primary and secondary prevention.

Finally, pro-poor inequity in the use of primary care is somewhat counterintuitive, too, given that GP visits, in the SSN, are easily accessible and free at the point of delivery for all patients. A second look at the first two panels of Figure1, however, may help in interpreting this finding. As we can see, the probability curve for GP visits is a close mirror image of the curve for specialist visits: as the former decreases, the latter increases approximately by the same amount, so that their sum within each level of SES remains about the same. This might indicate some sort of substitution effect, whereby the probability of visiting a physician of any kind is essentially constant, but the ratio of (inexpensive) GP visits to (expensive) specialist visits increases as SES decreases. In this view, access to outpatient visits of any kind appears perfectly equitable, but the quality of received care is inequitable in favor of the well-off.

The main novelty of our study is the stratified analysis of inequity by level of health status. This analysis uncovered a noteworthy pattern of heterogeneity in the phenomenon of interest: the degree of inequity in health services utilization tends to decrease as health status decreases—and, therefore, as the need for health care increases. Although this trend is neither regular nor strictly monotonic, our tests showed that it is not a mere artifact of sampling error. Thus, there are good reasons to assume that as the need for health care increases, its utilization approaches equity. This is not necessarily reassuring, however. Indeed, the presence of the highest levels of inequity among people in good health suggests that the benefits of prevention and early diagnosis are unequally distributed in favor of the well-off. This is consistent with our previous observation: when need is not apparent or immediate—that is, when health status is perceived as good or fair—low-SES groups tend to hold back their use of expensive or inefficient health services. In terms of general health inequalities, this is a relevant issue, as it implies that, on average, both low-SES groups limit their use of preventive care and postpone their access to curative care, creating the conditions for a future worsening of their health status and, eventually, for an increase in public health expenditure. In this view, the findings of our stratified analysis have relevant policy implications, as they suggest that the SSN should focus its efforts to reduce inequity of access to health care not so much on people in poor health, for whom equity is already established (or nearly so), but rather on people in good health.

To conclude, it is important to highlight the main limitations of this study. First, utilization of GP visits, specialist visits, and diagnostic tests was measured using a relatively short time frame (4 weeks); although this may help reducing recall bias, it may also mask relevant SES differences in frequency of health services utilization, especially among individuals in good health. Second, our measures of health care utilization are not fully satisfactory also for another reason: we have no way of knowing whether the episodes recorded by our response variables are instances of appropriate utilization or, rather, of overutilization (i.e., unnecessary health care use). If overutilization is confounded with appropriate utilization, then we have misclassification of the response variables which, in turn, may bias our estimates of horizontal inequity. Finally, because of limitations in the available data, our discussion of the role possibly played by the private health sector in shaping the observed patterns of horizontal inequity was only conjectural. This lack of complete information on type of provider does not alter our description of horizontal inequity per se—which, by definition, applies to the health care system as a whole—but does limit our ability to provide an empirically based interpretation of our findings in terms of public versus private.

Acknowledgments

Joint Acknowledgment/Disclosure Statement: This study is based on research undertaken by Valeria Glorioso for her Ph.D. dissertation at the Department of Sociology and Social Research of the University of Milano-Bicocca, Italy. Part of this research was carried out while Valeria Glorioso was a visiting Ph.D. student researcher at the Department of Social and Behavioral Sciences of the Harvard School of Public Health. A previous version of this study was presented at the conference “2nd ISA Forum of Sociology 2012,” Buenos Aires, August 1–4, 2012. We thank all the participants in that conference for helpful comments and suggestions; we also thank Maurizio Pisati for reading and commenting on an earlier version of this study.

Disclosures: None.

Disclaimers: None.

Supporting Information

Additional supporting information may be found in the online version of this article:

Appendix SA1: Author Matrix.

Table SA1: Prevalence (Percent) of the Variables of Interest in the Study Sample, Overall and by Health Status (for Socioeconomic Status: Mean and Standard Deviation).

Table SA2: For Each Estimated Regression Model, the Table Reports (a) Mean and Standard Deviation of the Posterior Distribution of Regression Coefficient β1 (×100); (b) Mean and Standard Deviation of the Posterior Distribution of Regression Coefficient β2 (×10,000); and (c) Statistic and p-value of the Joint Wald Significance Test for β1 and β2.

References

- Aday LA, Andersen RM. A Framework for the Study of Access to Medical Care. Health Services Research. 1974;9(3):208–20. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aday LA, Andersen RM. Development of Indices of Access to Medical Care. Ann Arbor, MI: Health Administration Press; 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Aday LA, Andersen RM. Equity of Access to Medical Care: A Conceptual and Empirical Overview. Medical Care. 1981;19(12 Suppl):4–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allin S, Hernández-Quevedo C, Masseria C. Measuring Equity of Access to Health Care. In: Smith PC, Mossialos E, Papanicolas I, Leatherman S, editors. Performance Measurement for Health System Improvement: Experiences, Challenges and Prospects. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; 2009. pp. 187–221. [Google Scholar]

- Allin S, Masseria C, Mossialos E. Measuring Socioeconomic Differences in Use of Health Care Services by Wealth versus by Income. American Journal of Public Health. 2009;99(10):1849–55. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.141499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atella V, Brindisi F, Deb P, Rosati FC. Determinants of Access to Physician Services in Italy: A Latent Class Seemingly Unrelated Probit Approach. Health Economics. 2004;13(7):657–68. doi: 10.1002/hec.860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bago d'Uva T, Jones AM. Health Care Utilisation in Europe: New Evidence from the ECHP. Journal of Health Economics. 2009;28(2):265–79. doi: 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2008.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baldini M, Turati G. Perceived Quality of Public Services, Liquidity Constraints, and the Demand of Private Specialist Care. Empirical Economics. 2012;42(2):487–511. [Google Scholar]

- Balsa AI, Rossi M, Triunfo P. Horizontal Inequity in Access to Health Care in Four South American Cities. Revista de Economía del Rosario. 2011;14(1):31–56. [Google Scholar]

- Bennett IM, Chen J, Soroui JS, White S. The Contribution of Health Literacy to Disparities in Self-rated Health Status and Preventive Health Behaviors in Older Adults. The Annals of Family Medicine. 2009;7(3):204–11. doi: 10.1370/afm.940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berkman ND, Sheridan SL, Donahue KE, Halpern DJ, Crotty K. Low Health Literacy and Health Outcomes: An Updated Systematic Review. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2011;155(2):97–107. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-155-2-201107190-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braveman P. Health Disparities and Health Equity: Concepts and Measurement. Annual Review of Public Health. 2006;27:167–94. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.27.021405.102103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Browne WJ. MCMC Estimation in MLwiN: Version 2.26. University of Bristol, Centre for Multilevel Modelling; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Cissé B, Luchini S, Moatti JP. Progressivity and Horizontal Equity in Health Care Finance and Delivery: What about Africa? Health Policy. 2007;80(1):51–68. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2006.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Culyer AJ. Need: The Idea Won't Do—But We Still Need It. Social Science & Medicine. 1995;40(6):727–30. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(94)00307-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Culyer AJ, Wagstaff A. Equity and Equality in Health and Health Care. Journal of Health Economics. 1993;12(4):431–57. doi: 10.1016/0167-6296(93)90004-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daniels N. Just Health Care. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- France G, Taroni F, Donatini A. The Italian Health-care System. Health Economics. 2005;14(S1):S187–202. doi: 10.1002/hec.1035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gelman A, Hill J. Data Analysis Using Regression and Multilevel/Hierarchical Models. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Goddard M, Smith PC. Equity of Access to Health Care Services: Theory and Evidence from the UK. Social Science & Medicine. 2001;53(9):1149–62. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(00)00415-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graubard BI, Korn EL. Predictive Margins with Survey Data. Biometrics. 1999;55(2):652–9. doi: 10.1111/j.0006-341x.1999.00652.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanratty B, Zhang T, Whitehead M. How Close Have Universal Health Systems Come to Achieving Equity in Use of Curative Services? A Systematic Review. International Journal of Health Services. 2007;37(1):89–109. doi: 10.2190/TTX2-3572-UL81-62W7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Istat. Il sistema di indagini sociali multiscopo. Istituto Nazionale di Statistica: Contenuti e metodologia delle indagini. Roma; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Istat. Condizioni di salute, fattori di rischio e ricorso ai servizi sanitari: Anno 2005. Roma: Istituto Nazionale di Statistica; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Banca d'Italia. Archivio storico dell'Indagine sui bilanci delle famiglie italiane, 1977–2006. Roma: Banca d'Italia; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Lane PW, Nelder JA. Analysis of Covariance and Standardization as Instances of Prediction. Biometrics. 1982;38(3):613–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Grand J. Equity, Health, and Health Care. Social Justice Research. 1987;1(3):257–74. [Google Scholar]

- Leckie G, Charlton C. runmlwin: A Program to Run the MLwiN Multilevel Modeling Software from within Stata. Journal of Statistical Software. 2013;52(11):1–40. [Google Scholar]

- Lo Scalzo A, Donatini A, Orzella L, Cicchetti A, Profili S, Maresso A. Italy: Health System Review. Health Systems in Transition. 2009;11(6):1–216. [Google Scholar]

- Lu J-f, Leung GM, Kwon S, Tin KYK, Van Doorslaer E, O'Donnell O. Horizontal Equity in Health Care Utilization: Evidence from Three High-income Asian Economies. Social Science & Medicine. 2007;64(1):199–212. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.08.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mackenbach JP, Kunst AE. Measuring the Magnitude of Socio-economic Inequalities in Health: An Overview of Available Measures Illustrated with Two Examples from Europe. Social Science & Medicine. 1997;44(6):757–71. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(96)00073-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masseria C, Giannoni M. Equity in Access to Health Care in Italy: A Disease-based Approach. The European Journal of Public Health. 2010;20(5):504–10. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/ckq029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masseria C, Paolucci F. Equità nell'accesso ai ricoveri ospedalieri in Europa e in Italia. Quaderni acp. 2005;12(1):3–7. [Google Scholar]

- O'Donnell O, van Doorslaer E, Wagstaff A, Lindelow M. Analyzing Health Equity Using Household Survey Data: A Guide to Techniques and Their Implementation. Washington, DC: World Bank Publications; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Rasbash J, Steele F, Browne WJ, Goldstein H. A User's Guide to MLwiN: Version 2.26. University of Bristol, Centre for Multilevel Modelling; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Rebba V. I ticket sanitari: strumenti di controllo della domanda o artefici di disuguaglianze nell'accesso alle cure? Politiche Sanitarie. 2009;10(4):221–42. [Google Scholar]

- Ruger JP. Health and Social Justice. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Skrondal A, Rabe-Hesketh S. Prediction in Multilevel Generalized Linear Models. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society: Series A (Statistics in Society) 2009;172(3):659–87. [Google Scholar]

- StataCorp. Stata Statistical Software: Release 12. College Station, TX: StataCorp LP; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Subramanian SV, Jones K, Duncan C. Multilevel Methods for Public Health Research. In: Kawachi I, Berkman LF, editors. Neighborhoods and Health. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press; 2003. pp. 65–111. [Google Scholar]

- Van Doorslaer E, Koolman X, Jones AM. Explaining Income-Related Inequalities in Doctor Utilisation in Europe. Health Economics. 2004;13(7):629–47. doi: 10.1002/hec.919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Doorslaer E, Masseria C and the OECD Health Equity Research Group Members. Towards High-Performing Health Systems: Policy Studies. Paris: OECD; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Van Doorslaer E, Wagstaff A, Rutten F. Equity in the Finance and Delivery of Health Care: An International Perspective. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Ware JE, Jr, Kosinski M, Keller SD. A 12-Item Short-Form Health Survey: Construction of Scales and Preliminary Tests of Reliability and Validity. Medical Care. 1996;34(3):220–33. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199603000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitehead M. The Concepts and Principles of Equity and Health. International Journal of Health Services. 1992;22(3):429–45. doi: 10.2190/986L-LHQ6-2VTE-YRRN. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix SA1: Author Matrix.

Table SA1: Prevalence (Percent) of the Variables of Interest in the Study Sample, Overall and by Health Status (for Socioeconomic Status: Mean and Standard Deviation).

Table SA2: For Each Estimated Regression Model, the Table Reports (a) Mean and Standard Deviation of the Posterior Distribution of Regression Coefficient β1 (×100); (b) Mean and Standard Deviation of the Posterior Distribution of Regression Coefficient β2 (×10,000); and (c) Statistic and p-value of the Joint Wald Significance Test for β1 and β2.