Background: PI3Kγ is implicated in insulin secretion and actin remodeling and is activated by glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide (GIP).

Results: GIP activates Ras-related-C3 botulinum toxin substrate-1 (Rac1), induces actin remodeling, and amplifies β-cell insulin secretion in a PI3Kγ-dependent manner.

Conclusion: Insulin secretion induced by GIP requires PI3Kγ.

Significance: Understanding the β-cell signaling pathway will help us understand β-cell dysfunction in diabetes.

Keywords: Actin, Exocytosis, Insulin, Pancreatic Islet, Phosphatidylinositide 3-Kinase (PI 3-Kinase), Ras-related C3 Botulinum Toxin Substrate 1 (Rac1), Type 2 Diabetes

Abstract

PI3Kγ, a G-protein-coupled type 1B phosphoinositol 3-kinase, exhibits a basal glucose-independent activity in β-cells and can be activated by the glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide (GIP). We therefore investigated the role of the PI3Kγ catalytic subunit (p110γ) in insulin secretion and β-cell exocytosis stimulated by GIP. We inhibited p110γ with AS604850 (1 μmol/liter) or knocked it down using an shRNA adenovirus or siRNA duplex in mouse and human islets and β-cells. Inhibition of PI3Kγ blunted the exocytotic and insulinotropic response to GIP receptor activation, whereas responses to the glucagon-like peptide-1 or the glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonist exendin-4 were unchanged. Downstream, we find that GIP, much like glucose stimulation, activates the small GTPase protein Rac1 to induce actin remodeling. Inhibition of PI3Kγ blocked these effects of GIP. Although exendin-4 could also stimulate actin remodeling, this was not prevented by p110γ inhibition. Finally, forced actin depolymerization with latrunculin B restored the exocytotic and secretory responses to GIP during PI3Kγ inhibition, demonstrating that the loss of GIP-induced actin depolymerization was indeed limiting insulin exocytosis.

Introduction

Both rodent and human β-cells express G-protein-coupled receptors that are activated by peptide hormones of the secretin family: glucose-dependent insulinotropic peptide (GIP)4 and glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) (1–5). GIP and GLP-1 are released from the intestine following a nutrient stimulus and potentiate insulin secretion from pancreatic β-cells (6–9).

Type 2 diabetes and metabolic syndrome are associated with disturbances in the incretin-signaling pathway (10, 11). Although still controversial, a number of studies suggest that secretion of GIP (but not its stimulatory action) is preserved in type 2 diabetes (12–14), whereas the action of GLP-1 is maintained, but its secretion is blunted (10, 13–15).

GIP and GLP-1 bind distinct seven-transmembrane domain G-protein-coupled receptors (GIP-R and GLP-1-R) (1, 2, 5, 16). GIP-R and GLP-1-R activation leads to the activation of adenylate cyclase and a rise in intracellular cAMP. This potentiates insulin secretion through both PKA and the guanine nucleotide exchange factor Epac and an increase in cytosolic Ca2+ (17–21). Certain anti-diabetic agents, such as the incretin mimetic class of drugs, exploit this pathway by activating the GLP-1 receptor (22, 23).

Class 1 PI3Ks are implicated in incretin receptor signaling (24–26). The nonselective PI3K inhibitor wortmannin partially inhibits GIP stimulated insulin secretion in a clonal β-cell line, in a manner independent of cAMP generation (26). Although the best studied PI3Ks (type 1A) are activated through tyrosine kinase receptors (27), the lone type 1B PI3K isoform PI3Kγ is activated by G-protein βγ subunits (28). Furthermore, GIP is shown to directly activate PI3Kγ in INS-1 cells, as measured by an increase in the production of its main phosphorylation product phosphatidylinositol 3,4,5-trisphosphate (25). We demonstrated previously that PI3Kγ is required for a robust insulin secretory response by promoting actin depolymerization and insulin granule recruitment to the plasma membrane (29).

Given the importance of incretin action to secretory dysfunction in type 2 diabetes, we now examine the requirement for PI3Kγ in incretin-stimulated insulin secretion. We demonstrate that pharmacological inhibition, or shRNA-mediated knockdown of p110γ impairs the insulinotropic effect of GIP-R (but not GLP-1-R) activation in mouse and human islets. We show that GIP is a potent stimulator of insulin granule exocytosis, an effect that is blunted with p110γ inhibition or knockdown. Furthermore, we show that p110γ inhibition prevents GIP-induced actin depolymerization, likely by preventing activation of the small GTPase protein Rac1. Finally, we show that forced actin depolymerization restores the insulinotropic effect of GIP in cells lacking functional p110γ. Thus, we demonstrate that in addition to the classical cAMP pathway, PI3K signaling through p110γ is required for the full insulinotropic effect of GIP.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Cells and Cell Culture

Islets from male C57/BL6 mice were isolated by collagenase digestion and then handpicked. Human islets from 14 healthy donors (53 ± 5 years of age) were from either the Clinical Islet Laboratory at the University of Alberta or the IsletCore program at the Alberta Diabetes Institute. Islets were dispersed to single cells in Ca2+-free buffer. INS-1 832/13 cells were a gift of Prof. Christopher Newgard (Duke University). Islet and cell culture was as described previously (29, 30). All studies were approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee and the Human Research Ethics Board at the University of Alberta.

DNA and Adenovirus Constructs

The p110γ shRNA and scrambled control sequence were previously characterized (29). Expression was via recombinant adenovirus produced by transferring the expression cassettes into the Adeno-X viral vector (Clontech) followed by adenovirus production in HEK293 cells as previously described (29) An additional siRNA sequence tested was from Applied Biosystems (catalog no. 4390771; Burlington, Canada). An Allstars negative control siRNA was from Qiagen (catalog no. 1027284).

Pharmacologic Inhibitors and Peptides

AS6048505 (2,2-difluoro-benzo[1,3] dioxol-5-ylmethylene)-thiazolidine-2,4-dione) (Selleckchem, Houston, TX) is a selective, competitive inhibitor of p110γ (IC50 = 250 nmol/liter for p110γ versus 4.5 μmol/liter for p110α and >20 μmol/liter for p110β) (31). It exhibits no notable activity against a wide array of kinases at concentrations of 1 μmol/liter. Latrunculin B, a potent actin-depolymerizing agent, was from Sigma-Aldrich. GIP and GLP-1(7–36) peptides were from AnaSpec (Fremont, CA). Exendin-4 was from Sigma-Aldrich.

Immunoblotting

Cell lysates were subjected to SDS-PAGE and transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes (Millipore, Billerica, MA), probed with primary antibodies (anti-p110α, anti-p110β, and anti-p110γ (Cell Signaling Technology, Beverly, MA); anti-β-actin (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA); and anti-Rac1 (Cytoskeleton, Denver, CO)). Detection was with peroxidase-conjugated secondary anti-rabbit and anti-mouse antibodies (GE Healthcare), and visualization by chemiluminescence (ECL-Plus; GE Healthcare) and exposure to x-ray film (Fujifilm, Tokyo, Japan).

Quantitative PCR

RNA was extracted using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen) from dispersed mouse β-cells 48 h post transfection with siRNA constructs. Real time quantitative PCR assays were carried out on the 7900HT Fast Real-Time PCR system using Fast SYBR Green Master Mix (Applied Biosystems) as the amplification system. Primers were as follows: mouse p110γ forward, 5′-CATCAATAAAGAGAGAGTGCCCTTCGTCCTAAC-3′; mouse p110γ reverse, 5′-CTAGGTAAGCTCTAACACAGACATCCTGATTTC-3′; mouse cyclophilin forward, 5′-CGCGTCTCCTTCGAGCTGTTTGC-3′; and mouse cyclophilin reverse, 5′-GTGTAAA GTCACCACCCTGGCACATGAATC-3′.

Rac1 Activation Assays

INS-1 cells were treated overnight with AS604850 (1 μmol/liter) or DMSO vehicle. Cells were preincubated for 2 h in 1 mmol/liter glucose Krebs Ringer buffer (KRB; 115 mmol/liter NaCl, 5 mmol/liter KCl, 24 mmol/liter NaHCO3, 2.5 mmol/liter CaCl2, 1 mmol/liter MgCl2, and 10 mmol/liter HEPES, pH 7.4) and then stimulated for 25 min with either 1 or 16.7 mmol/liter glucose KRB. For GIP stimulation experiments, 100 nmol/liter GIP was included in the 1 or 16.7 mmol/liter glucose KRB. Rac1 activity was determined with GST-p21-activated kinase binding domain as described in the Rac1 pulldown activation biochem kit manual (Cytoskeleton, Inc., Denver, CO).

Insulin Secretion Measurements

Islets (either mouse or human) were treated overnight with 1 μmol/liter AS604850, (or vehicle) or infected with a p110γ shRNA adenovirus (or scrambled control) for 72 h. Static insulin secretion measurements were performed at 37 °C in KRB, as described previously (29, 30). GIP (100 nmol/liter), Ex-4 (100 nmol/liter), GLP-1 (10 nmol/liter), or latrunculin B (10 μmol/liter) was present during the 60-min 16.7-mmol/liter glucose KRB stimulation as indicated. Human islet perifusion was performed at 37 °C using a Brandel SF-06 system (Gaithersburg, MD) after a 2-h preincubation in KRB with 1 mmol/liter glucose. Thirty-five islets per lane were perifused (0.5 ml/min) with KRB with glucose as indicated. Samples stored at −20 °C were assayed for insulin via enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (MSD, Rockville, MD).

Electrophysiology

We used the standard whole cell technique with the sine+DC lockin function of an EPC10 amplifier and Patchmaster software (HEKA Electronics, Lambrecht/Pfalz, Germany). Experiments were performed at 32–35 °C. Solutions used for capacitance measurements are previously described (29, 30). For GIP (100 nmol/liter) or Ex-4 (100 nmol/liter) stimulation experiments, the peptides were added to the bath solution prior to patch-clamping. For some experiments, the pipette solution also contained 10 μmol/liter latrunculin B. For experiments in Fig. 9C, cells were preincubated in 1 mmol/liter bath solution for 1 h and glucose or GIP were added to the bath as indicated. Capacitance responses and Ca2+ currents were normalized to initial cell size and expressed as femtofarad per picofarad and picoamperes per picofarad. Mouse β-cells were identified by size, whereas human β-cells were identified by insulin immunostaining.

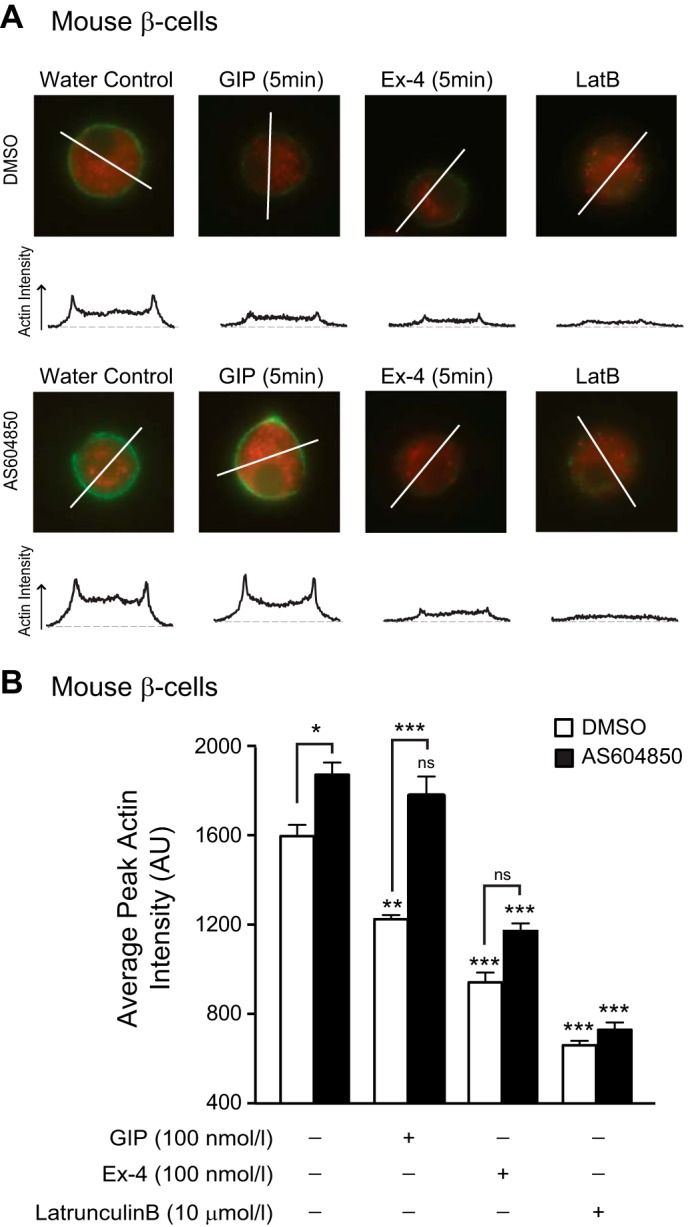

FIGURE 9.

GIP-induced actin depolymerization in mouse β-cells at low glucose is blunted by p110γ inhibition, but GIP does not stimulate exocytosis at low glucose. A, representative images, and intensity line scans for F-actin staining (green) of dispersed mouse β-cells treated overnight with either DMSO or AS604850 (1 μmol/liter) and preincubated with 2.8 mmol/liter glucose for 2 h prior to treatment with a water control, 16.7 mmol/liter glucose, GIP (100 nmol/liter), or latrunculin B (10 μmol/liter) for indicated time periods. B, average peak actin intensities following treatments are shown. C, representative capacitance recordings (left panel) and the averaged cumulative capacitance responses (right panel) from mouse β-cells preincubated with 1 mmol/liter glucose for 1 h and then treated with vehicle (gray line), GIP (100 nmol/liter; black line), or 10 mmol/liter glucose (light gray line). *, p < 0.5; **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001 compared with low glucose, or as indicated.

Actin Staining

Mouse islets were dispersed into single cells onto coverslips as previously described (29). Cells were treated overnight with the AS604850 inhibitor (1 μmol/liter) or vehicle. For Figs. 7 and 8, the glucose concentration was 11 mmol/liter. For the low glucose experiments in Fig. 9, cells were preincubated with 2.8 mmol/liter KRB for 2 h prior to treatments. For GIP, Ex-4, and latrunculin B experiments, cells were treated as indicated. Immediately following treatment, cells were fixed with Z-FIX (Anatech, Battle Creek, MI). Cells were stained for insulin with rabbit anti-insulin primary antibody (Santa Cruz, CA) and Alexa Fluor 594 goat anti-rabbit secondary antibody (Invitrogen). Cells were also stained for filamentous actin (F-actin) with Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated phalloidin (Invitrogen). The cells were imaged with a Zeiss Axio Observer.Z1 microscope and ×63 Plan ApoChromat objective (1.4 NA). Excitation was with a COLIBRITM (Carl Zeiss Canada, Toronto, Canada) LED light source with 495- or 555-nm filter set. Only insulin-positive cells were used for F-actin intensity measurement, which were analyzed using ImageJ software (National Institutes of Health).

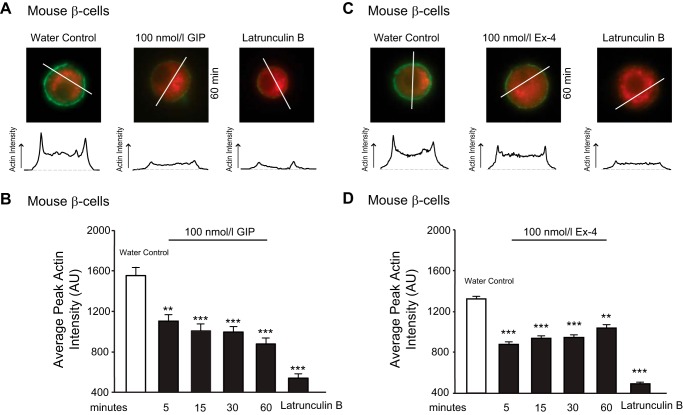

FIGURE 7.

GIP-R and GLP-1-R activation induces actin depolymerization in mouse β-cells. A, dispersed mouse β-cells (in 11 mmol/liter glucose) were treated with water control, GIP (100 nmol/liter), or latrunculin B (10 μmol/liter) for indicated time periods and subsequently fixed with Z-FIX. Cells were stained for insulin (red) and F-actin (green). Representative images are shown at top with intensity line scans for F-actin staining below. B, average peak actin intensities following treatments are shown. C and D, the same as A and B, except cells were treated with Ex-4 (100 nmol/liter) instead of GIP. **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001 compared with the water control.

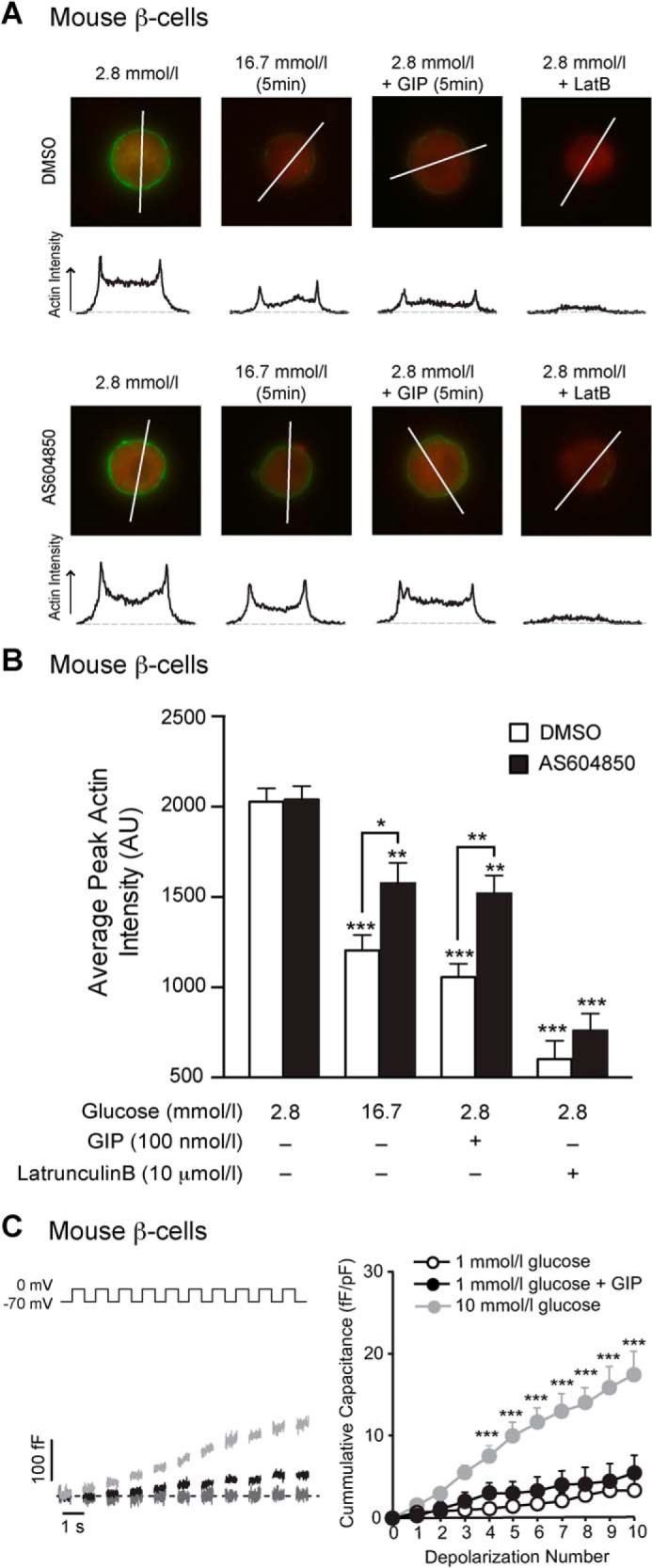

FIGURE 8.

p110γ inhibition prevents GIP-induced actin depolymerization in mouse β-cell. A, representative images, and intensity line scans for F-actin staining (green) of dispersed mouse β-cells (in 11 mmol/liter glucose) treated overnight with either DMSO or AS604850, and water control, GIP (100 nmol/liter), Ex-4 (100 nmol/liter), or latrunculin B (LatB, 10 μmol/liter) for indicated time periods. B, average peak actin intensities following treatments. *, p < 0.5; **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001 compared with the control condition, or as indicated; ns, non significant.

Statistical Analysis

For single-cell electrophysiology or imaging studies, the n values represent the number of cells studied from at least three individual experiments. For secretion and perifusion studies, the n values represent numbers of distinct islet preparations from at least three individual experiments. Electrophysiological data were extracted using FitMaster v2.32 (HEKA Electronik). All data were analyzed using the Student t test, or post hoc Tukey test following a two-way analysis of variance where more than two groups were present. Statistical outliers were removed using the Grubb's test. The data are expressed as means ± S.E., and p < 0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

p110γ Inhibition Blunts the Insulinotropic Effect of GIP-R Activation in Mouse and Human Islets

Expression of the p110γ catalytic subunit of PI3K was confirmed by Western blot in INS-1 832/13 cells, mouse islets, and human islets (Fig. 1A). The p110γ inhibitor AS604850 (1 μmol/liter, overnight) did not alter expression of p110γ protein in INS-1 832/13 cells (Fig. 1B). Because other PI3K catalytic isoforms could possibly compensate for each other, we examined the effects of AS604850 on protein expression of p110α and p110β in INS-1 832/13 cells and found no difference following overnight p110γ inhibition (Fig. 1B).

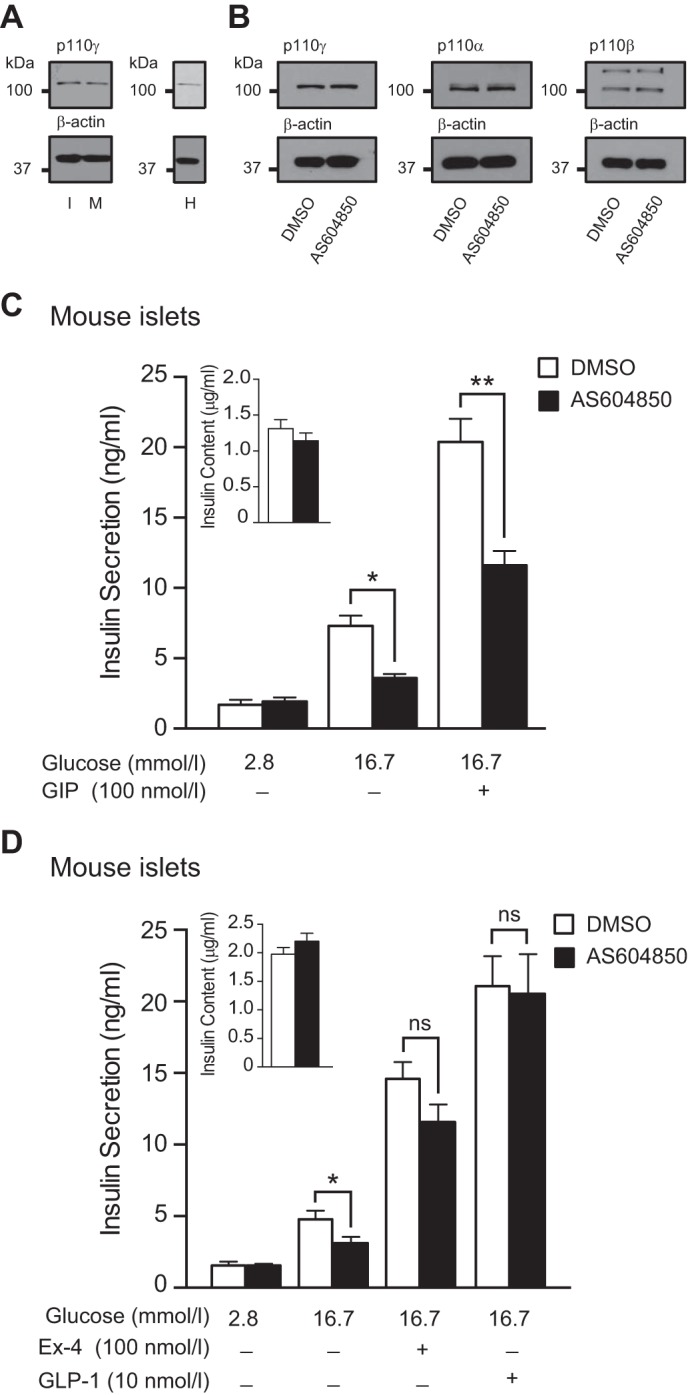

FIGURE 1.

p110γ inhibition impairs GIP-R, but not GLP-1-R-stimulated insulin secretion from mouse islets. A, expression of p110γ was confirmed by Western blot of protein lysates from INS-1 832/13 (I), mouse islets (M), and human islets (H). B, p110γ, p110α, and p110β protein expression levels from INS-1 832/13 cells following overnight treatment with either DMSO or AS604850 (1 μmol/liter). β-Actin was used as a loading control. C, glucose and GIP (100 nmol/liter; 1 h) stimulated insulin secretion was measured from mouse islets treated overnight with either DMSO (open bars) or AS604850 (1 μmol/liter; black bars). D, glucose and GLP-1-stimulated (10 nmol/liter; 1 h) or Ex-4-stimulated (100 nmol/liter; 1 h) insulin secretion was measured from mouse islets treated overnight with either DMSO (open bars) or AS604850 (1 μmol/liter; black bars). Inset shows total insulin content. *, p < 0.5; **, p < 0.01; ns, not significant.

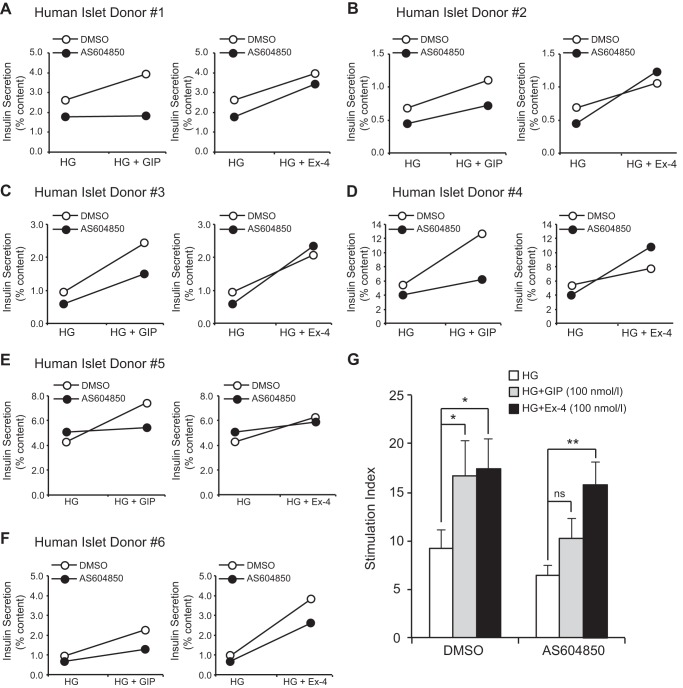

Consistent with our previous findings using a different p110γ-selective inhibitor (29), inhibition of p110γ with AS604850, (1 μmol/liter overnight) decreased glucose-stimulated insulin secretion from mouse islets by 50% (n = 18 from seven distinct experiments, p < 0.05; Fig. 1C). The insulinotropic effect of GIP (100 nmol/liter) was blunted by 46% following inhibition of p110γ (n = 17 from seven distinct experiments, p < 0.01; Fig. 1C). Insulin content was unaffected by overnight p110γ inhibition (n = 18 from seven distinct experiments, Fig. 1C (inset)), nor was there a change in GIP-R or GLP-1-R mRNA as measured by quantitative PCR (not shown). The secretory response to GIP was also blunted by p110γ inhibition in islets from six human donors (Fig. 2). This suggests that GIP-induced insulin secretion requires p110γ activity, in line with previous demonstrations that GIP can activate p110γ in INS-1 cells (25) and that GIP-dependent insulin secretion is blunted by the pan-PI3K inhibitor wortmannin (26).

FIGURE 2.

p110γ inhibition impairs GIP-R, but not GLP-1-R-stimulated insulin secretion from human islets. A–F, glucose-stimulated (HG) and GIP-stimulated (100 nmol/liter; 1 h; left panels) or Ex-4-stimulated (100 nmol/liter; 1 h; right panels) insulin secretion was measured from human islets treated overnight with either DMSO (open circles) or AS604850 (1 μmol/liter; black circles). Each individual donor is shown in a separate panel. G, averaged secretory responses to glucose alone (open bars) and together with GIP (100 nmol/liter; gray bars) or Ex-4 (100 nmol/liter; black bars) from the six donors, shown as the stimulation index (fold increase over a low glucose control). *, p < 0.5; **, p < 0.01 as indicated; ns, non significant.

p110γ Inhibition Does Not Impair the Insulinotropic Effect of GLP-1-R Activation in Mouse and Human Islets

p110γ−/− mice have an impaired insulin secretory response that is rescued by chronic Ex-4 administration (32, 33). We thus examined the insulinotropic effect of GLP-1 (10 nmol/liter) and the GLP-1 agonist Ex-4 (100 nmol/liter) following p110γ inhibition in isolated islets. Insulin secretion in response to either GLP-1 or Ex-4 was not blunted following p110γ inhibition in mouse islets (n = 16 from six distinct experiments Fig. 1D). Similarly, Ex-4 remained able to stimulate insulin secretion from islets of six human donors (Fig. 2). This suggests that insulin secretion stimulated by the GIP-R, but not the GLP-1-R, requires p110γ.

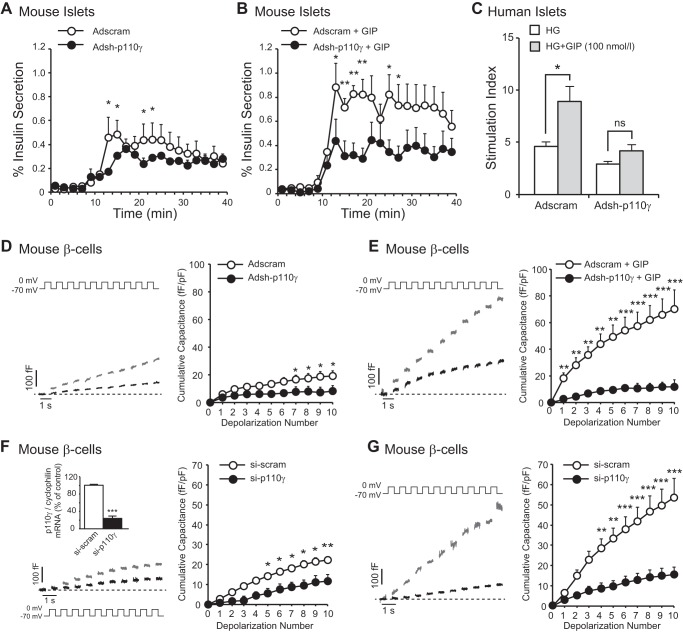

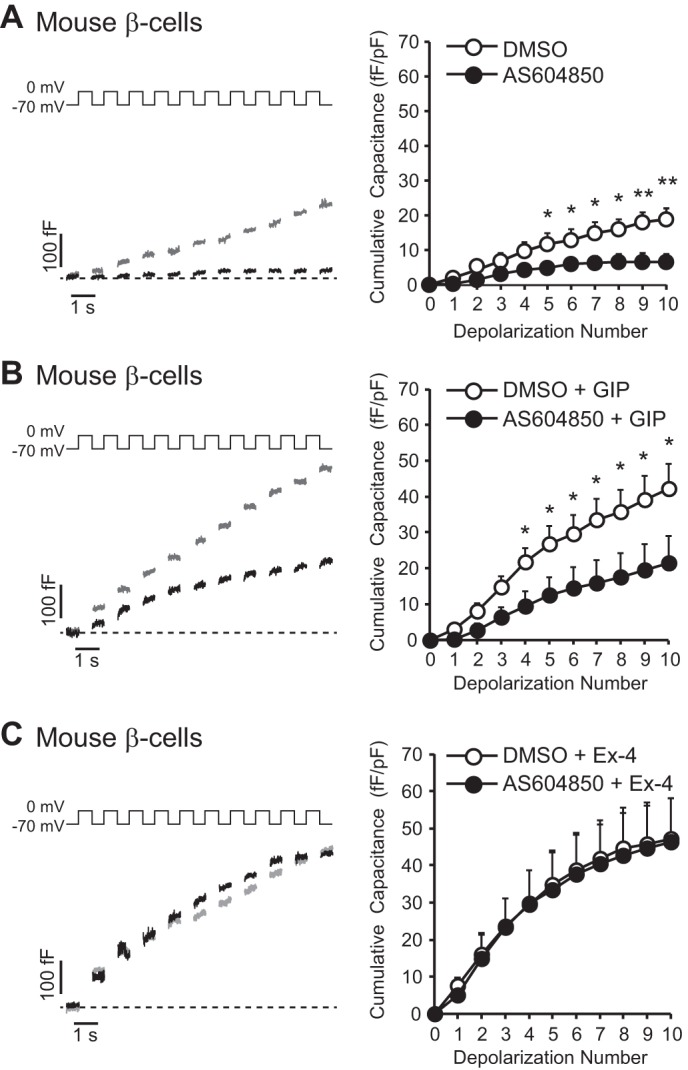

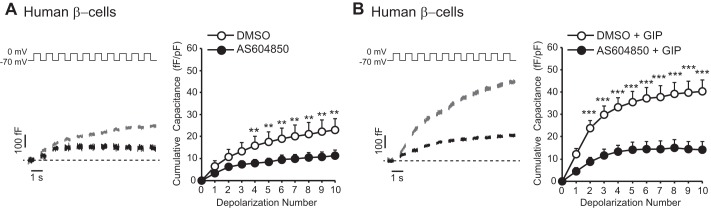

p110γ Inhibition Prevents GIP-induced Exocytosis in Mouse and Human β-Cells

We next monitored β-cell exocytosis as whole cell capacitance increases in response to a train of membrane depolarizations following p110γ inhibition. AS604850 (1 μmol/liter, overnight) decreased exocytosis by 60% (n = 15–18, p < 0.01; Fig. 3A) in mouse β-cells. GIP treatment (100 nmol/liter) increased exocytosis in control cells by 2.3-fold (n = 15–17, p < 0.05; Fig. 3, A and B), an effect that was blunted following p110γ inhibition (n = 16–17; Fig. 3B). Conversely, Ex-4 treatment (100 nmol/liter) increased exocytosis in control cells by 2.6-fold (n = 15–19, p < 0.01; Fig. 3, A and C), and p110γ inhibition did not blunt the ability of Ex-4 to stimulate the exocytotic response (n = 16–19; Fig. 3C).

FIGURE 3.

p110γ inhibition impairs GIP-potentiated exocytosis from mouse β-cells. A, representative capacitance recordings (left panel) and averaged cumulative capacitance responses (right panel) from mouse β-cells treated overnight with vehicle DMSO (gray lines, open circles) or AS604850 (1 μmol/liter; black lines, black circles). B, shows the same as A, except cells were additionally treated with GIP (100 nmol/liter; 1 h). C, shows the same as A, except cells were additionally treated with Ex-4 (100 nmol/liter; 1 h). *, p < 0.5; **, p < 0.01.

We also monitored whole cell capacitance following p110γ inhibition in human β-cells. Similar to the mouse data, inhibition of p110γ decreased the exocytotic response by 50% (n = 20–23, p < 0.01; Fig. 4A). GIP (100 nmol/liter) increased exocytosis in control cells by 1.8-fold (n = 19–23, p < 0.01; Fig. 4, A and B), and this was severely blunted following p110γ inhibition (n = 17–19; Fig. 4B).

FIGURE 4.

p110γ inhibition impairs GIP-potentiated exocytosis from human β-cells. A, representative capacitance recordings (left panel) and averaged cumulative capacitance responses (right panel) from human β-cells treated overnight with vehicle DMSO (gray lines, open circles) or AS604850 (1 μmol/liter; black lines, black circles). B, shows the same as A, except cells were additionally treated with GIP (100 nmol/liter; 1 h). **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001.

p110γ Knockdown Impairs the Response to GIP in Mouse and Human Islets

Knockdown of p110γ using an adenoviral shRNA construct (Adsh-p110γ) that we have previously shown to reduce p110γ protein expression by 78% (29) results in impaired insulin exocytosis when compared with a scrambled control. In line with our observations using pharmacological inhibition, infection of mouse islets with Adsh-p110γ impaired the insulinotropic effect of GIP (100 nmol/liter) measured during perifusion (n = 4,4, p < 0.05; Fig. 5, A and B). Similarly, the insulinotropic effect of GIP (100 nmol/liter) was also blunted in human islets infected with Adsh-p110γ (n = 6 distinct donors, p < 0.05; Fig. 5C). Insulin content was not significantly changed during any treatment conditions. Adsh-p110γ also severely impaired the ability of GIP (100 nmol/liter) to increase exocytosis in mouse β-cells (n = 15–18, p < 0.01; Fig. 5, D and E).

FIGURE 5.

Knockdown of p110γ impairs GIP-amplified insulin secretion from mouse islets and exocytosis from mouse β-cells. A, insulin secretion was measured by perifusion of isolated mouse islets infected with Adsh-scram (open circles) or Adsh-p110γ (black circles). 16.7 mmol/liter glucose was perifused at 10 min. B, shows the same as A, except cells were additionally perifused with GIP (100 nmol/liter; added at 10 min). C, static insulin secretion was measured from human islets infected with Adsh-scram or Adsh-p110γ in response to high glucose alone (open bars) or with 100 nmol/liter GIP (gray bars), shown as the stimulation index (fold increase over a low glucose control). HG, 10 mmol/liter glucose-stimulated. D, representative capacitance recordings (left panel) and averaged cumulative capacitance responses (right panel) from mouse β-cells infected with Adsh-scram (gray lines, open circles) or Adsh-p110γ (black lines, black circles). E, shows the same as C, except cells were additionally treated with GIP (100 nmol/liter; 1 h). F, representative capacitance recordings (left panel) and averaged cumulative capacitance responses (right panel) from mouse β-cells transfected with si-scram (gray lines, open circles) or si-p110γ (black lines, black circles). The mRNA expression of p110γ (normalized to cyclophilin) following transfection with si-scram (open bar) or si-p110γ (black bar) is shown inset. G, shows the same as F, except cells were additionally treated with GIP (100 nmol/liter; 1 h). *, p < 0.5; **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001.

To confirm these results using a separate knockdown approach, we measured exocytosis in mouse β-cells following transfection with an siRNA duplex (si-p110γ) targeting a different region of p110γ, which decreased p110γ mRNA expression by 76% compared with a scrambled control (n = 3, p < 0.001; Fig. 5F [inset]). si-p110γ, which blunted the exocytotic response mouse β-cells (n = 12–16, p < 0.05; Fig. 5F), also severely impaired the ability of GIP (100 nmol/liter) to increase exocytosis (n = 12–15, p < 0.001; Fig. 5G).

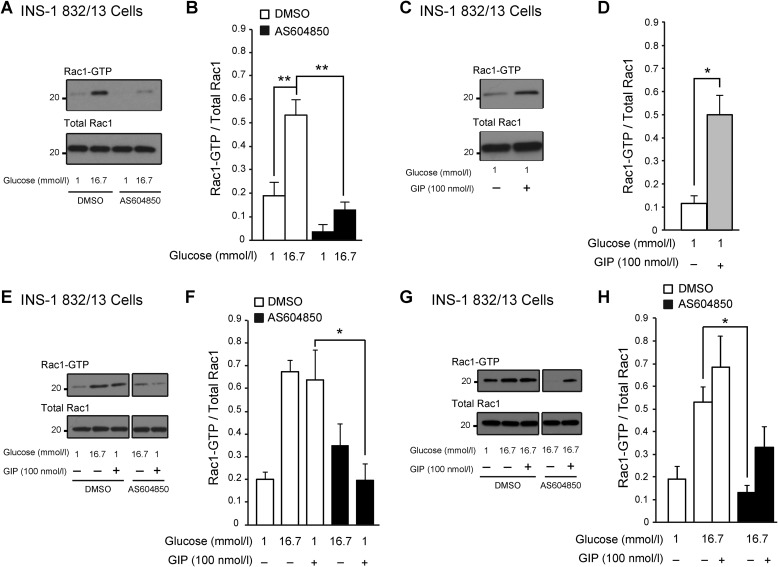

p110γ Inhibition Blunts Rac1 Activation

Next, we explored the mechanism by which p110γ inhibition impairs the insulinotropic effect of GIP. Small GTPase proteins such as Rac1 are implicated in the insulin secretory response, having well defined roles in actin remodeling (34–36). Recent studies in β-cell-specific Rac1 knock-out (βRac1−/−) mice demonstrate that Rac1 controls insulin secretion by promoting cytoskeletal rearrangement and recruitment of insulin-containing granules to the plasma membrane (37). In addition, INS-1 832/13 cells lacking Rac1 or the ability to activate Rac1 fail to reorganize actin in response to glucose and exhibit a decreased insulin secretory response (36, 37).

Because p110γ inhibition is associated with increased actin polymerization and a reduction in insulin granules at the plasma membrane (29), we examined Rac1 activation in INS-1 832/13 treated with AS604850 (1 μmol/liter, overnight). We find that p110γ inhibition severely impairs glucose-stimulated Rac1 activation, without affecting total Rac1 levels (n = 3, p < 0.01; Fig. 6, A and B). Compared with controls, glucose-stimulated Rac1 activation was decreased by 76% in AS604850-treated cells (n = 3, p < 0.01; Fig. 6, A and B).

FIGURE 6.

p110γ inhibition impairs glucose- and GIP-activated Rac1 activation in INS-1 832/13 cells. A, representative blots of activated Rac1 and total Rac1 in response to high glucose shown in cells treated overnight with either DMSO or AS604850 (1 μmol/liter). B, average Rac1 activation (normalized to total Rac1) in response to glucose shown in cells treated overnight with either DMSO (open bar) or AS604850 (1 μmol/liter; black bar). C, a representative blot of activated Rac1 in response to GIP (100 nmol/liter, 25 min). D, average Rac1 activation (normalized to total Rac1 present) in response to GIP (100 nmol/liter, 25 min; black bar). E, representative blots of activated Rac1 and total Rac1 in response to GIP (100 nmol/liter, 25 min) in cells treated overnight with either DMSO or AS604850 (1 μmol/liter) (blots shown are from different parts of the same gel). F, average Rac1 activation (normalized to total Rac1 present) in response to GIP (100 nmol/liter, 25 min; black bar) in cells treated overnight with either DMSO (open bars) or AS604850 (1 μmol/liter; black bars). G, representative blots of activated Rac1 and total Rac1 in response to glucose together with GIP (100 nmol/liter, 25 min) shown in cells treated overnight with either DMSO or AS604850 (1 μmol/liter). H, average Rac1 activation (normalized to total Rac1) in response to glucose together with GIP is shown in cells treated overnight with either DMSO (open bar) or AS604850 (1 μmol/liter; black bar). *, p < 0.5; **, p < 0.01 as indicated.

GIP Activates Rac1 in a p110γ-dependent Manner

GLP-1-R activation has been postulated to activate Rac1 through PKA-mediated activation of the serine/threonine-protein kinase PAK 1 (34). We now show that GIP stimulates Rac1 activation in INS-1 cells (Fig. 6, C and D) under low glucose conditions. GIP (100 nmol/liter, 25 min) increased Rac1 activation by 4.3-fold (n = 3, p < 0.05; Fig. 6, C and D). However, when p110γ activity was inhibited, GIP-mediated Rac1 activation was blocked (Fig. 6, E and F). When GIP (100 nmol/liter, 25 min) is present together with high glucose, we see no significant further potentiation of Rac1 activity (n = 3; Fig. 6, G and H), suggesting that this may represent a point at which glucose and GIP signaling converge.

GIP-R and GLP-1-R Activation Stimulates Actin Depolymerization

Cortical actin is an important determinant of the exocytotic response (29, 34, 38). We know that p110γ inhibition blunts exocytosis by increasing cortical actin density and limiting the number of insulin containing granules at the plasma membrane (29). Rac1 activation is necessary to induce a secretory response (36, 37) and actin reorganization in response to glucose (37). Thus, we examined whether GIP-R and GLP-1-R activation affects cortical actin. We find that both GIP (100 nmol/liter) and Ex-4 (100 nmol/liter) induce actin depolymerization in mouse β-cells. After 5 min, cortical actin was decreased by 29% (n = 55–65, p < 0.001; Fig. 7, A and B) with GIP (100 nmol/liter) and by 31% (n = 75–85, p < 0.001; Fig. 7, C and D) with Ex-4 (100 nmol/liter). This effect was maintained over 60 min (Fig. 7, B and D). In comparison, latrunculin B (10 μmol/liter, 2 min), a potent actin-depolymerizing agent, reduced actin intensity by 64–65% (n = 40–60, p < 0.001; Fig. 7, B and D).

p110γ Is Required for GIP-R-dependent (but Not GLP-1-R-dependent) Actin Depolymerization

Because p110γ inhibition prevents the insulinotropic effect of GIP and cortical actin dynamics are essential to insulin secretion (34), we investigated the role of p110γ in GIP-induced actin depolymerization. Although GIP (100 nmol/liter, 5 min) depolymerized cortical F-actin by 30% in dispersed mouse β-cells (n = 88–93 from four mice, p < 0.01; Fig. 8, A and B), this response was lost following p110γ inhibition (n = 89–90 from four mice, p = ns; Fig. 8, A and B). Both vehicle- and AS604850-treated cells responded to latrunculin B (n = 61–71 from four mice, p < 0.001; Fig. 8, A and B).

Conversely, inhibition of p110γ did not prevent actin depolymerization induced by Ex-4. Ex-4 (100 nmol/liter, 5 min) decreased F-actin density by 32% in vehicle-treated controls (n = 66–88 from four mice, p < 0.001; Fig. 8, A and B) and by 37% in AS604850-treated cells (n = 64–89 from four mice, p < 0.001; Fig. 8, A and B).

GIP-R Activation Induces Depolymerization of F-actin under Low Glucose Conditions, and This Is Blunted by p110γ Inhibition

Because we show that GIP induces Rac1 activation under low glucose conditions, we examined whether GIP also depolymerizes F-actin under this condition. Indeed, we find that GIP (100 nmol/liter, 5 min) decreased F-actin density by 48% in vehicle-treated control cells preincubated with 2.8 mmol/liter glucose for 2 h (n = 40–43 from three mice, p < 0.001; Fig. 9, A and B). This effect was significantly blunted when p110γ was inhibited (n = 40–43 from three mice, p < 0.01; Fig. 9, A and B).

GIP-R Activation Does Not Stimulate Exocytosis under Low Glucose Conditions

Because GIP-R activation depolymerizes F-actin at low glucose, we examined whether this is sufficient to potentiate depolarization-induced exocytosis in mouse β-cells. Although the exocytotic response in these cells was reduced at low glucose (1 mmol/liter), it was elevated by inclusion of 10 mmol/liter glucose in the bath (Fig. 9C). However, neither GIP (100 nmol/liter; Fig. 9C) nor latrunculin B (10 μmol/liter; not shown) was able to enhance the exocytotic response at 1 mmol/liter glucose. This is consistent with the known glucose dependence of the effects of GIP (39–41) and further reinforces the importance of additional pathways that amplify β-cell exocytosis and insulin secretion (42–44).

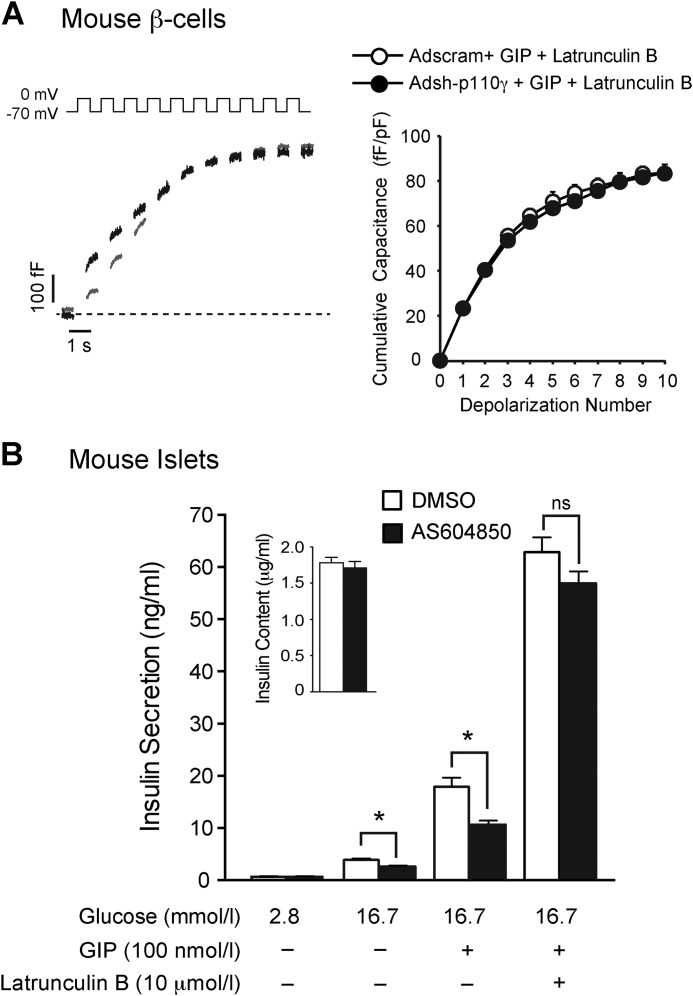

Forced Actin Depolymerization Restores GIP-mediated Exocytosis and Insulin Secretion following p110γ Inhibition or Knockdown

We next determined whether the impairment of the ability of GIP to increase exocytosis (at 5 mmol/liter glucose) and insulin secretion following p110γ inhibition is due to its inability to induce actin depolymerization. Upon intracellular dialysis of latrunculin B (10 μmol/liter via the patch-pipette), the GIP-stimulated capacitance response of mouse β-cells was unaffected by Adsh-p110γ compared with a scrambled control (n = 12–15; Fig. 10A). Accordingly, the blunted secretory response to GIP observed following p110γ inhibition was reversed by acute treatment of islets with latrunculin B (10 μmol/liter) (n = 4; Fig. 10B). These data suggest that the impaired glucose-dependent insulinotropic effect of GIP seen following p110γ inhibition is mediated by its inability to depolymerize actin.

FIGURE 10.

Forced disruption of F-actin restores the insulinotropic effects of GIP. A, representative membrane capacitance traces (left) from mouse β-cells infected with Adsh-scram (gray lines) or Adsh-p110γ (black lines), treated with GIP (100 nmol/liter, 1 h) and with 10 μmol/liter latrunculin B included in the patch pipette. At right is the average capacitance response over the course of the depolarization trains. B, glucose-stimulated insulin secretion in the presence of GIP (100 nmol/liter) and/or latrunculin B (10 μmol/liter) was measured from mouse islets treated overnight with either DMSO (open bars) or AS604850 (1 μmol/liter) (black bars). *, p < 0.05 as indicated.

DISCUSSION

We have previously shown that the G-protein-coupled PI3Kγ is a positive regulator of insulin secretion by controlling cortical actin density and targeting secretory granules to the plasma membrane (29). The two incretin hormones GIP and GLP-1 signal through distinct Gs-coupled G-protein receptors, their major mechanism of action being linked to a rise in cAMP (19, 45).

GIP can directly stimulate PI3Kγ activity, as measured by an increase in PIP3 production in insulinoma cells (25). GIP signaling has also been linked to a wortmannin-sensitive pathway (26). Conversely, the insulin secretory defect of PI3Kγ KO mice is reversed following chronic Ex-4 treatment, suggesting that PI3Kγ is not required for the insulinotropic actions of GLP-1 (32). GLP-1-R (or GIP-R) activation increases intracellular cAMP, which subsequently activates PKA. This has been postulated to activate Rac1 through PKA-mediated activation of the serine/threonine-protein kinase PAK 1 (34). Furthermore, p110γ is implicated in PAK 1 activation (albeit in a non-insulin-secreting line (46)).

Thus, we now investigated whether PI3Kγ is required for GIP-R and/or GLP-1-R-induced insulin secretion and examine the role of GIP-mediated Rac1 activation and actin remodeling. We find that selective inhibition of p110γ, or shRNA-mediated knockdown, impairs the insulinotropic effect of GIP in both mouse and human islets. This does not appear to be due to a loss of the GIP-R because mRNA expression of either this or GLP-1-R is not reduced following p110γ inhibition.

We also find that both GIP and Ex-4 are potent potentiators of insulin exocytosis and that p110γ inhibition or knockdown blocks the GIP-mediated facilitation of exocytosis. This is consistent with work by Straub et al. (26), who found that wortmannin inhibits the insulinotropic effect of GIP (but not forskolin) in HIT-T15 insulinoma cells. The authors linked this effect to the possible inhibition of a “novel exocytosis-linked G-protein βγ subunit activated PI3K,” which our work now demonstrates is PI3Kγ.

Surprisingly, our results indicate that the insulinotropic effect of GLP-1 or its agonist Ex-4 is not impaired following p110γ inhibition. The ability of Ex-4 to stimulate exocytosis or depolymerize actin is also not impaired following p110γ inhibition. These results are consistent with earlier observations showing that Ex-4 rescues the glucose-stimulated secretory defect in islets from p110γ−/− mice (33) and suggest that the GIP-R and GLP-1-R are differentially coupled to PI3Kγ.

The GLP-1-R has been linked to activation of class 1A PI3Ks through transactivation of the EGF receptor in the β-cell (47). Although it is possible, because PI3Kα and PI3Kβ (class 1A PI3Ks) also regulate insulin secretion (27, 30), that these may link the GLP-1-R to actin depolymerization, it should be noted that selective inhibition of PI3Kα potentiates glucose-stimulated insulin secretion (30). This would be inconsistent with a positive role in GLP-1-dependent insulin secretion.

Recent reports suggest that p110γ−/− mice are protected from obesity-induced inflammation and insulin resistance (48–50). These studies suggest that p110γ inhibition may be beneficial, because it would limit the inflammatory response associated with obesity. These studies were, however, done in vivo, in mice ubiquitously lacking p110γ (48–50). PI3Kγ is highly expressed in cells of the immune system (51, 52). The improvements in insulin resistance in p110γ−/− mice are largely due to protection from inflammatory stress when on a high fat diet (48–50), which may mask an underlying role of p110γ as a positive regulator of insulin secretion in β-cells. Also, any defect in the insulinotropic effects of GIP in these mice could be compensated by intact GLP-1 signaling, which is not impaired following p110γ inhibition.

Our results point to a mechanism by which GIP activates the small GTPase protein Rac1 to induce actin depolymerization. p110γ has previously been shown to be involved in the activation of Rac1 in immune cells (53, 54). Phosphatidylinositol 3,4,5-trisphosphate and Gβγ both activate Rac1 by activating Rac-specific guanine nucleotide exchange factors (55, 56).

Small GTPase proteins, such as Rac1, are implicated in the insulin secretory response (35–37). Insulin-producing cells lacking Rac1 or in which the ability of Rac1 to be activated is blocked lack glucose stimulated actin remodeling and show impaired insulin secretion (35–37). Dispersed β-cells from βRac1−/− mice also show a reduction in insulin granule recruitment to the plasma membrane (37), similar to what we reported previously upon loss of p110γ (29). Thus, we now suggest that the insulinotropic effects of GIP are blunted when p110γ is inhibited or knocked down. Much like glucose, GIP activates Rac1, in a manner that depends on p110γ, to induce actin remodeling.

F-actin can act as a barrier to insulin secretion by limiting vesicle fusion with the plasma membrane (29, 38, 57–59). Our finding that GIP-stimulated insulin secretion and the GIP-potentiated capacitance response were no longer different upon actin depolymerization with latrunculin B suggests that the lack of F-actin depolarization upon p110γ inhibition was indeed limiting to GIP-induced secretion. However, whereas GIP activates Rac1 and depolymerizes actin at low glucose, this alone is insufficient to potentiate depolarization-induced exocytosis in β-cells and suggests that the glucose dependence of the actions of GIP lies downstream of this pathway.

In summary, we show that the insulinotropic effect of GIP is blunted following p110γ inhibition or knockdown in both mouse and human cells. Although functional p110γ is required for glucose-stimulated insulin secretion, independent of incretin receptor activation, the fact that p110γ inhibition does not impair the insulinotropic effect of GLP-1-R activation is indicative of the requirement for p110γ in the insulinotropic effects of GIP. This PI3Kγ-dependent pathway will facilitate insulin granule access to the plasma membrane to, in concert with classical cAMP/PKA-dependent signaling, and potentiate Ca2+-dependent exocytosis and insulin secretion.

Acknowledgments

We thank Nancy Smith and James Lyon for technical assistance, Dr. Christopher Newgard (Duke University) for providing INS-1 832/13 cells, Drs. Mourad Ferdaoussi and Kunimasa Suzuki (Alberta Diabetes Institute, University of Alberta) for help with qPCR, and Drs. Tatsuya Kin and James Shapiro (Clinical Islet Laboratory, University of Alberta) for human islets. We also thank the Human Organ Procurement and Exchange (HOPE) program and the Trillium Gift of Life Network (TGLN) for their efforts in procuring human pancreata for research.

The work was supported by an operating grant to PEM from the Canadian Diabetes Association. Human islet isolations were funded in part by the Alberta Diabetes Foundation and the University of Alberta.

- GIP

- glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide

- GLP-1

- glucagon-like peptide-1

- Ex-4

- exendin-4

- KRB

- Krebs-Ringer buffer.

REFERENCES

- 1. Thorens B., Porret A., Bühler L., Deng S. P., Morel P., Widmann C. (1993) Cloning and functional expression of the human islet GLP-1 receptor: demonstration that exendin-4 is an agonist and exendin-(9–39) an antagonist of the receptor. Diabetes 42, 1678–1682 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Dillon J. S., Tanizawa Y., Wheeler M. B., Leng X. H., Ligon B. B., Rabin D. U., Yoo-Warren H., Permutt M. A., Boyd A. E. (1993) Cloning and functional expression of the human glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor. Endocrinology 133, 1907–1910 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Volz A., Göke R., Lankat-Buttgereit B., Fehmann H. C., Bode H. P., Göke B. (1995) Molecular cloning, functional expression, and signal transduction of the GIP-receptor cloned from a human insulinoma. FEBS Lett. 373, 23–29 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Usdin T. B., Mezey E., Button D. C., Brownstein M. J., Bonner T. I. (1993) Gastric inhibitory polypeptide receptor, a member of the secretin-vasoactive intestinal peptide receptor family, is widely distributed in peripheral organs and the brain. Endocrinology 133, 2861–2870 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Gremlich S., Porret A., Hani E. H., Cherif D., Vionnet N., Froguel P., Thorens B. (1995) Cloning, functional expression, and chromosomal localization of the human pancreatic islet glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide receptor. Diabetes 44, 1202–1208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Pederson R. A., Brown J. C. (1976) The insulinotropic action of gastric inhibitory polypeptide in the perfused isolated rat pancreas. Endocrinology 99, 780–785 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Mojsov S., Weir G. C., Habener J. F. (1987) Insulinotropin: glucagon-like peptide I (7–37) co-encoded in the glucagon gene is a potent stimulator of insulin release in the perfused rat pancreas. J. Clin. Invest. 79, 616–619 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Holst J. J., Gromada J. (2004) Role of incretin hormones in the regulation of insulin secretion in diabetic and nondiabetic humans. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 287, E199–E206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Drucker D. J. (2006) The biology of incretin hormones. Cell Metab. 3, 153–165 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Nauck M., Stöckmann F., Ebert R., Creutzfeldt W. (1986) Reduced incretin effect in type 2 (non-insulin-dependent) diabetes. Diabetologia 29, 46–52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Knop F. K., Vilsbøll T., Højberg P. V., Larsen S., Madsbad S., Vølund A., Holst J. J., Krarup T. (2007) Reduced incretin effect in type 2 diabetes: cause or consequence of the diabetic state? Diabetes 56, 1951–1959 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Calanna S., Christensen M., Holst J. J., Laferrère B., Gluud L. L., Vilsbøll T., Knop F. K. (2013) Secretion of glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide in patients with type 2 diabetes: systematic review and meta-analysis of clinical studies. Diabetes Care 36, 3346–3352 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Vilsbøll T., Krarup T., Deacon C. F., Madsbad S., Holst J. J. (2001) Reduced postprandial concentrations of intact biologically active glucagon-like peptide 1 in type 2 diabetic patients. Diabetes 50, 609–613 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Nauck M. A., Heimesaat M. M., Orskov C., Holst J. J., Ebert R., Creutzfeldt W. (1993) Preserved incretin activity of glucagon-like peptide 1 [7–36 amide] but not of synthetic human gastric inhibitory polypeptide in patients with type-2 diabetes mellitus. J. Clin. Invest. 91, 301–307 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Vilsbøll T., Knop F. K. (2007) [Effect of incretin hormones GIP and GLP-1 for the pathogenesis of type 2 diabetes mellitus]. Ugeskr. Laeg. 169, 2101–2105 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Thorens B. (1992) Expression cloning of the pancreatic β cell receptor for the gluco-incretin hormone glucagon-like peptide 1. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 89, 8641–8645 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Seino S., Takahashi H., Fujimoto W., Shibasaki T. (2009) Roles of cAMP signalling in insulin granule exocytosis. Diabetes Obes. Metab. 11, (Suppl. 4) 180–188 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Yabe D., Seino Y. (2011) Two incretin hormones GLP-1 and GIP: comparison of their actions in insulin secretion and β cell preservation. Prog. Biophys. Mol. Biol. 107, 248–256 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Drucker D. J. (2013) Incretin action in the pancreas: potential promise, possible perils, and pathological pitfalls. Diabetes 62, 3316–3323 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Roscioni S. S., Elzinga C. R. S., Schmidt M. (2008) Epac: effectors and biological functions. Naunyn Schmiedeberg's Arch. Pharmacol. 377, 345–357 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Song W.-J., Seshadri M., Ashraf U., Mdluli T., Mondal P., Keil M., Azevedo M., Kirschner L. S., Stratakis C. A., Hussain M. A. (2011) Snapin mediates incretin action and augments glucose-dependent insulin secretion. Cell Metab. 13, 308–319 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Barnett A. (2007) Exenatide. Expert Opin. Pharmacother. 8, 2593–2608 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Edwards C. M. (2004) GLP-1: target for a new class of antidiabetic agents? J. R. Soc. Med. 97, 270–274 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Friedrichsen B. N., Neubauer N., Lee Y. C., Gram V. K., Blume N., Petersen J. S., Nielsen J. H., Møldrup A. (2006) Stimulation of pancreatic β-cell replication by incretins involves transcriptional induction of cyclin D1 via multiple signalling pathways. J. Endocrinol. 188, 481–492 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Trümper A., Trümper K., Trusheim H., Arnold R., Göke B., Hörsch D. (2001) Glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide is a growth factor for β (INS-1) cells by pleiotropic signaling. Mol. Endocrinol. 15, 1559–1570 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Straub S. G., Sharp G. W. (1996) Glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide stimulates insulin secretion via increased cyclic AMP and [Ca2+]1 and a wortmannin-sensitive signalling pathway. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 224, 369–374 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Kaneko K., Ueki K., Takahashi N., Hashimoto S., Okamoto M., Awazawa M., Okazaki Y., Ohsugi M., Inabe K., Umehara T., Yoshida M., Kakei M., Kitamura T., Luo J., Kulkarni R. N., Kahn C. R., Kasai H., Cantley L. C., Kadowaki T. (2010) Class IA phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase in pancreatic β cells controls insulin secretion by multiple mechanisms. Cell Metab. 12, 619–632 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Stoyanov B., Volinia S., Hanck T., Rubio I., Loubtchenkov M., Malek D., Stoyanova S., Vanhaesebroeck B., Dhand R., Nürnberg B. (1995) Cloning and characterization of a G protein-activated human phosphoinositide-3 kinase. Science 269, 690–693 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Pigeau G. M., Kolic J., Ball B. J., Hoppa M. B., Wang Y. W., Rückle T., Woo M., Manning Fox J. E., MacDonald P. E. (2009) Insulin granule recruitment and exocytosis is dependent on p110γ in insulinoma and human β-cells. Diabetes 58, 2084–2092 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Kolic J., Spigelman A. F., Plummer G., Leung E., Hajmrle C., Kin T., Shapiro A. M., Manning Fox J. E., MacDonald P. E. (2013) Distinct and opposing roles for the phosphatidylinositol 3-OH kinase catalytic subunits p110α and p110β in the regulation of insulin secretion from rodent and human β cells. Diabetologia 56, 1339–1349 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Camps M., Rückle T., Ji H., Ardissone V., Rintelen F., Shaw J., Ferrandi C., Chabert C., Gillieron C., Françon B., Martin T., Gretener D., Perrin D., Leroy D., Vitte P.-A., Hirsch E., Wymann M. P., Cirillo R., Schwarz M. K., Rommel C. (2005) Blockade of PI3Kγ suppresses joint inflammation and damage in mouse models of rheumatoid arthritis. Nat. Med. 11, 936–943 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. MacDonald P. E., Joseph J. W., Yau D., Diao J., Asghar Z., Dai F., Oudit G. Y., Patel M. M., Backx P. H., Wheeler M. B. (2004) Impaired glucose-stimulated insulin secretion, enhanced intraperitoneal insulin tolerance, and increased β-cell mass in mice lacking the p110γ isoform of phosphoinositide 3-kinase. Endocrinology 145, 4078–4083 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Li L.-X., MacDonald P. E., Ahn D. S., Oudit G. Y., Backx P. H., Brubaker P. L. (2006) Role of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinaseγ in the β-cell: interactions with glucagon-like peptide-1. Endocrinology 147, 3318–3325 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Kalwat M. A., Thurmond D. C. (2013) Signaling mechanisms of glucose-induced F-actin remodeling in pancreatic islet β cells. Exp. Mol. Med. 45, e37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Wang Z., Thurmond D. C. (2009) Mechanisms of biphasic insulin-granule exocytosis: roles of the cytoskeleton, small GTPases and SNARE proteins. J. Cell Sci. 122, 893–903 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Li J., Luo R., Kowluru A., Li G. (2004) Novel regulation by Rac1 of glucose- and forskolin-induced insulin secretion in INS-1 β-cells. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 286, E818–E827 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Asahara S., Shibutani Y., Teruyama K., Inoue H. Y., Kawada Y., Etoh H., Matsuda T., Kimura-Koyanagi M., Hashimoto N., Sakahara M., Fujimoto W., Takahashi H., Ueda S., Hosooka T., Satoh T., Inoue H., Matsumoto M., Aiba A., Kasuga M., Kido Y. (2013) Ras-related C3 botulinum toxin substrate 1 (RAC1) regulates glucose-stimulated insulin secretion via modulation of F-actin. Diabetologia 56, 1088–1097 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Jewell J. L., Luo W., Oh E., Wang Z., Thurmond D. C. (2008) Filamentous actin regulates insulin exocytosis through direct interaction with Syntaxin 4. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 10716–10726 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Holz G. G., 4th, Kühtreiber W. M., Habener J. F. (1993) Pancreatic β-cells are rendered glucose-competent by the insulinotropic hormone glucagon-like peptide-1(7–37). Nature 361, 362–365 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Kieffer T. J., Habener J. F. (1999) The glucagon-like peptides. Endocr. Rev. 20, 876–913 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. MacDonald P. E., El-Kholy W., Riedel M. J., Salapatek A. M. F., Light P. E., Wheeler M. B. (2002) The multiple actions of GLP-1 on the process of glucose-stimulated insulin secretion. Diabetes 51 (Suppl. 3) S434–S442 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Merrins M. J., Stuenkel E. L. (2008) Kinetics of Rab27a-dependent actions on vesicle docking and priming in pancreatic β-cells. J. Physiol. 586, 5367–5381 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Straub S. G., James R. F., Dunne M. J., Sharp G. W. (1998) Glucose activates both KATP channel-dependent and KATP channel-independent signaling pathways in human islets. Diabetes 47, 758–763 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. McClenaghan N. H., Flatt P. R., Ball A. J. (2006) Actions of glucagon-like peptide-1 on KATP channel-dependent and -independent effects of glucose, sulphonylureas and nateglinide. J. Endocrinol. 190, 889–896 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Campbell J. E., Drucker D. J. (2013) Pharmacology, physiology, and mechanisms of incretin hormone action. Cell Metab. 17, 819–837 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Jung I. D., Lee J., Lee K. B., Park C. G., Kim Y. K., Seo D. W., Park D., Lee H. W., Han J.-W., Lee H. Y. (2004) Activation of p21-activated kinase 1 is required for lysophosphatidic acid-induced focal adhesion kinase phosphorylation and cell motility in human melanoma A2058 cells. Eur. J. Biochem. 271, 1557–1565 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Buteau J., Foisy S., Joly E., Prentki M. (2003) Glucagon-like peptide 1 induces pancreatic β-cell proliferation via transactivation of the epidermal growth factor receptor. Diabetes 52, 124–132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Wymann M. P., Solinas G. (2013) Inhibition of phosphoinositide 3-kinase γ attenuates inflammation, obesity, and cardiovascular risk factors. Ann. N.Y. Acad. Sci. 1280, 44–47 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Becattini B., Marone R., Zani F., Arsenijevic D., Seydoux J., Montani J.-P., Dulloo A. G., Thorens B., Preitner F., Wymann M. P., Solinas G. (2011) PI3Kγ within a nonhematopoietic cell type negatively regulates diet-induced thermogenesis and promotes obesity and insulin resistance. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 108, E854–63 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Kobayashi N., Ueki K., Okazaki Y., Iwane A., Kubota N., Ohsugi M., Awazawa M., Kobayashi M., Sasako T., Kaneko K., Suzuki M., Nishikawa Y., Hara K., Yoshimura K., Koshima I., Goyama S., Murakami K., Sasaki J., Nagai R., Kurokawa M., Sasaki T., Kadowaki T. (2011) Blockade of class IB phosphoinositide-3 kinase ameliorates obesity-induced inflammation and insulin resistance. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 108, 5753–5758 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Bernstein H. G., Keilhoff G., Reiser M., Freese S., Wetzker R. (1998) Tissue distribution and subcellular localization of a G-protein activated phosphoinositide 3-kinase. An immunohistochemical study. Cell Mol. Biol. (Noisy-le-grand) 44, 973–983 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Randis T. M., Puri K. D., Zhou H., Diacovo T. G. (2008) Role of PI3Kδ and PI3Kγ in inflammatory arthritis and tissue localization of neutrophils. Eur. J. Immunol. 38, 1215–1224 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Rommel C., Camps M., Ji H. (2007) PI3Kδ and PI3Kγ: partners in crime in inflammation in rheumatoid arthritis and beyond? Nat. Rev. Immunol. 7, 191–201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Weiss-Haljiti C., Pasquali C., Ji H., Gillieron C., Chabert C., Curchod M.-L., Hirsch E., Ridley A. J., Hooft van Huijsduijnen R., Camps M., Rommel C. (2004) Involvement of phosphoinositide 3-kinase γ, Rac, and PAK signaling in chemokine-induced macrophage migration. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 43273–43284 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Innocenti M., Frittoli E., Ponzanelli I., Falck J. R., Brachmann S. M., Di Fiore P. P., Scita G. (2003) Phosphoinositide 3-kinase activates Rac by entering in a complex with Eps8, Abi1, and Sos-1. J. Cell Biol. 160, 17–23 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Welch H. C., Coadwell W. J., Ellson C. D., Ferguson G. J., Andrews S. R., Erdjument-Bromage H., Tempst P., Hawkins P. T., Stephens L. R. (2002) P-Rex1, a PtdIns(3,4,5)P3- and Gβγ-regulated guanine-nucleotide exchange factor for Rac. Cell 108, 809–821 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Tomas A., Yermen B., Min L., Pessin J. E., Halban P. A. (2006) Regulation of pancreatic β-cell insulin secretion by actin cytoskeleton remodelling: role of gelsolin and cooperation with the MAPK signalling pathway. J. Cell Sci. 119, 2156–2167 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Thurmond D. C., Gonelle-Gispert C., Furukawa M., Halban P. A., Pessin J. E. (2003) Glucose-stimulated insulin secretion is coupled to the interaction of actin with the t-SNARE (target membrane soluble N-ethylmaleimide-sensitive factor attachment protein receptor protein) complex. Mol. Endocrinol. 17, 732–742 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Orci L., Gabbay K. H., Malaisse W. J. (1972) Pancreatic β-cell web: its possible role in insulin secretion. Science 175, 1128–1130 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]