Background: During Myxococcus xanthus sporulation, a rigid coat is assembled on the cell surface.

Results: The coat consists of oligosaccharides (1:17 Glc:GalNAc) and glycine, which are absent or unprocessed in exo or nfs mutants.

Conclusion: The spore coat glycan is secreted by Exo and rigidified by Nfs machineries.

Significance: The spore coat is a novel de novo synthesized structural glycan layer.

Keywords: Gram-negative Bacteria, Membrane Protein, Peptidoglycan, Polysaccharide, Sporulation

Abstract

Myxococcus xanthus is a Gram-negative deltaproteobacterium that has evolved the ability to differentiate into metabolically quiescent spores that are resistant to heat and desiccation. An essential feature of the differentiation processes is the assembly of a rigid, cell wall-like spore coat on the surface of the outer membrane. In this study, we characterize the spore coat composition and describe the machinery necessary for secretion of spore coat material and its subsequent assembly into a stress-bearing matrix. Chemical analyses of isolated spore coat material indicate that the spore coat consists primarily of short 1–4- and 1–3-linked GalNAc polymers that lack significant glycosidic branching and may be connected by glycine peptides. We show that 1–4-linked glucose (Glc) is likely a minor component of the spore coat with the majority of the Glc arising from contamination with extracellular polysaccharides, O-antigen, or storage compounds. Neither of these structures is required for the formation of resistant spores. Our analyses indicate the GalNAc/Glc polymer and glycine are exported by the ExoA-I system, a Wzy-like polysaccharide synthesis and export machinery. Arrangement of the capsular-like polysaccharides into a rigid spore coat requires the NfsA–H proteins, members of which reside in either the cytoplasmic membrane (NfsD, -E, and -G) or outer membrane (NfsA, -B, and -C). The Nfs proteins function together to modulate the chain length of the surface polysaccharides, which is apparently necessary for their assembly into a stress-bearing matrix.

Introduction

Diverse bacterial genera have evolved to withstand unfavorable environmental conditions by differentiating into resting stages, termed spores or cysts (1). These entities are metabolically quiescent and display increased resistance to physical and chemical stresses. Spores, in particular, are resistant to high temperatures, sonic disruption, degradative enzymes, and periods of desiccation. Spore differentiation has been most intensively studied for endospores, such as those produced by the Gram-positive Bacillus subtilis. Endospores are produced within the protective environment of a mother cell that supplies many of the enzymes necessary to build the spore coat (2). An entirely different model system for spore differentiation is that of the Gram-negative Myxococcus xanthus in which the entire 0.5 × 7-μm rod-shaped vegetative cell rearranges into a spherical spore of ∼1.7 μm in diameter without the protective environment of a mother cell.

A core feature of environmentally resistant spores is a dramatically altered cell envelope that contributes to the resistance features of spores. The composition and assembly of the spore cell envelope varies considerably between different spore formers, and many details of the respective assembly process have not yet been determined (3–6). In the case of B. subtilis, the spore coat is composed of an altered and thickened peptidoglycan sacculus (termed the spore cortex) surrounded by a protein-rich coat (4); some spores additionally contain a mucous layer apparently composed of soluble peptidoglycan fragments (7). In contrast, the M. xanthus spore coat material is primarily carbohydrate-rich and must be deposited on the outside of the outer membrane in a process that is directed from within the sporulating cell. Interestingly, in M. xanthus, the peptidoglycan layer appears to be degraded during spore differentiation, and the spore coat layer likely replaces its function (5, 8).

Our previous work identified two genetic loci, exoA–H and nfsA–H, important for production and assembly of the spore coat, respectively (5, 9). Disruption of either (or both) of these loci results in a phenotype in which cells initiate shape re-arrangement from rod to sphere but subsequently revert to rod-shaped cells. Reversion is preceded by a transient stage of cell fragility and severe shape deformations (branching and formation of spiral cells) that are reminiscent of phenotypes observed in certain Escherichia coli mutants defective in peptidoglycan synthesis (10). Electron microscopy analyses revealed that an exoC mutant lacks an obvious spore coat, whereas a ΔnfsA–H mutant produces a highly amorphous unstructured spore coat reminiscent of capsular material (5). Together, these observations suggest that assembly of a rigid, stress-bearing spore coat prior to removal of the periplasmic peptidoglycan is an essential step of spore differentiation.

The exact function of the Exo and Nfs machineries is not known. Some of the Exo proteins share homology with polysaccharide secretion machinery (5, 11), and the Nfs proteins share homology with proteins (Glt) that may power the M. xanthus gliding motility machinery (12). It has been demonstrated that both the Glt and Nfs machinery appear to be involved in protonmotive force-dependent possessive transport processes, but the consequence and details of this mechanism remain undiscovered (13).

In this study, we set out to clarify the function of the Nfs and Exo protein machineries by characterizing the composition of the M. xanthus spore coat in exo and nfs mutants relative to the wild type. Composition and subunit linkage analysis of spore coat material isolated from the wild type suggest that the spore coat primarily consists of 1–4- and 1–3-linked GalNAc polymers with very little O-glycosidic branching. We confirmed that glycine is a major component of the spore coat material, but we demonstrated that glucose, which is 1–4 linked, is only a minor component of the spore coat material; the majority of the detected glucose arises from contamination with storage compounds and EPS3 and/or O-antigen. We show that ExoA–I are essential for export of at least the GalNAc and glycine components and that NfsA–H form cell envelope spanning machinery, which is necessary for appropriate processing of surface polysaccharides into short surface oligosaccharides necessary to form a rigid three-dimensional network.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Bacterial Strains and Growth Conditions

Bacterial strains and plasmids are listed in Table 1. M. xanthus strains were cultivated at 32 °C on CYE medium plates or in CYE broth (14, 15). CYE agar was supplemented with 10 μg ml−1 oxytetracycline or 100 μg ml−1 kanamycin, where necessary. E. coli strains were grown at 37 °C on LB medium plates or broth (16), supplemented with 50 μg ml−1 kanamycin, 100 μg ml−1 ampicillin, or 100 μg ml−1 spectinomycin, as appropriate.

TABLE 1.

Strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain or plasmid | Genotype | Ref. or source |

|---|---|---|

| M. xanthus | ||

| DK1622 | Wild type | 59 |

| PH1261 | DK1622 ΔexoC | 5 |

| PH1200 | DK1622 ΔnfsA-H | 9 |

| PH1303 | DK1622 ΔexoB | This study |

| PH1304 | DK1622 ΔexoD | This study |

| PH1265 | DK1622 ΔexoE | This study |

| PH1507 | DK1622 ΔexoF | This study |

| PH1508 | DK1622 ΔexoG | This study |

| PH1264 | DK1622 ΔexoH | This study |

| PH1511 | DK1622 ΔexoI | This study |

| PH1509 | DK1622 ΔMXAN_1035 | This study |

| PH1270 | DK1622 wzm::ΩKanR | This study |

| PH1285 | DK1622 wzm::ΩKanR epsV::pCH19 | This study |

| PH1296 | DK1622 ΔexoC wzm::ΩKanR epsV::pCH19 | This study |

| HK1321 | DK1622 wzm::ΩKanR | 18, 60 |

| E. coli | ||

| TOP10 | Host for cloning [F− mcrA Δ(mrr-hsdRMS-mcrBC) Φ80lacZΔM15ΔlacX74 deoR recA1 arsD139 Δ(ara-leu)7697 galU halK rpsL (Strr) endA1 nupG] | Invitrogen |

| BL21(DE3) | Host for overexpression (fhuA2 [lon] ompT gal (λ DE3) [dcm] ΔhsdS) | Novagen |

| Plasmids | ||

| pBJ114 | Backbone for in-frame deletions; galK, KanR | 61 |

| pUC19 | cloning vector, AmpR | Thermo Scientific |

| pSW30 | Source of TcR cassette | 62 |

| pCDF-Duet | PrT7, SpcR | Novagen |

| pCOLA-Duet | PrT7, KanR | Novagen |

| pCH14–2 | pBJ114 ΔexoE (codons 5–451) | This study |

| pCH15–1 | pBJ114 ΔexoH (codons 11–374) | This study |

| pCH48 | pBJ114 ΔexoG (codons 16–337) | This study |

| pCH49 | pBJ114 ΔexoF (codons 26–351) | This study |

| pCH50 | pBJ114 ΔexoI (codons 8–381) | This study |

| pCH51 | pBJ114 ΔexoB (codons 16–388) | This study |

| pCH63 | pBJ114 ΔexoD (codons 7–215) | This study |

| pCH62 | pBJ114 ΔMXAN_1035 (codons 14–473) | This study |

| pCH19 | Internal fragments of epsV (codons 323–500) and TcR in pUC19 | This study |

| pCH20 | The nfsA–C coding region in pCDF-Duet | This study |

| pCH21 | The nfsD–H coding region in pCOLA-Duet | This study |

| pCH57 | The coding region of nfsC in pCDF-Duet | This study |

Plasmid and Strain Construction

Primers used to generate plasmids are listed in supplemental Table S1. The template for PCR amplifications was genomic DNA isolated from M. xanthus strain DK1622, unless otherwise indicated. The insert regions for all plasmids generated was sequenced to confirm the absence of PCR-generated errors. At least three independent M. xanthus clones for each mutant were tested to confirm stable and identical phenotypes.

Constructs used to generate markerless in-frame deletions in M. xanthus genes were constructed, as described previously (15), in which DNA fragments of ∼500 bp up- and downstream of the target gene were individually amplified and then fused. The resulting inserts were then cloned into pBJ114 (galK, kanR) using the EcoRI/HindIII sites (plasmids pCH48 and pCH50), KpnI/HindIII sites (pCH62), or EcoRI/BamHI sites (all other plasmids). The resulting plasmids were introduced into M. xanthus DK1622 cells by electroporation, and homologous recombination into the chromosomes was selected by resistance to kanamycin. Deletions were selected by galactose-mediated counter selection (17) as described previously in detail (15).

Strains bearing interruptions in wzm or epsV were generated as follows. To be sure of an isogenic background, the DK1622 wzm::ΩkanR mutant (PH1270) was recreated by transforming DK1622 with genomic DNA isolated from strain HK1321 (18), followed by selection on CYE plates containing kanamycin. For disruption of epsV, a tetracycline-resistant suicide vector was first generated. An oxytetracycline resistance cassette was PCR-amplified from pSWU30 using primers oPH1315/oPH1316 and inserted into the BamHI and/HindIII sites of pUC19. Next, an internal fragment of epsV (codons 323–500) was PCR-amplified using primers oPH1313/oPH1314 and inserted into the EcoRI and BamHI sites, generating pCH19. To generate strain PH1285 (wzm epsV), pCH19 was introduced by electroporation into PH1270, and its integration into the epsV region via homologous recombination was selected by plating cells on CYE medium plates containing oxytetracycline and kanamycin. Strain PH1296 (ΔexoC wzm epsV) was obtained by transforming strain PH1261 (ΔexoC) with plasmid pCH19, and positive clones were selected by plating the transformants on CYE plates containing oxytetracycline followed by screening as above. The resulting strain was transformed with genomic DNA isolated from strain PH1270, and positive clones were selected on kanamycin. For all epsV strains, the successful integration of pCH19 in the genome was demonstrated by PCR amplification using primers oPH1352 and oPH1316, which bind in the region upstream of epsV and in the oxytetracycline resistance cassette, respectively.

Plasmids for production of Nfs proteins in E. coli were generated as follows. Plasmid pCH20 contained the nfsA–C region cloned into the NcoI and BamHI sites of the pCDF-Duet vector. To circumvent the intrinsic NcoI site in nfsC (near codon 327), the region was cloned in two steps. First, the 3′ fragment of nfsC was amplified using primers oPH1376/oPH1377 and cloned into the NcoI/BamHI sites of pCDF. Second, a fragment containing nfsA and -B and the 5′ nfsC region were amplified using primers oPH1374/oPH1375 and cloned into the NcoI site, generating pCH20. Plasmid pCH21 contained the nfsD–H region in the NdeI/KpnI sites of the plasmid pCOLA-Duet. As PCR amplification of the entire 8.5-kb region was not successful, the coding region was cloned in two steps by taking advantage of the native BbvCI site in the intergenic region between nfsE and nfsF. First, the nfsD–E region was amplified using primers oPH1378/oPH1392 and inserted into the NdeI/KpnI sites of the pCOLA-Duet. Second, the nfsF–H region was PCR-amplified using primers oPH1393/oPH1379 and inserted into the BbvCI/KpnI restriction sites, generating pCH21. To generate pCH57, the nfsC coding region was PCR-amplified using primers oPH1478/oPH1479 and inserted into the NdeI/KpnI sites of pCDF.

Induction of Sporulation

Sporulation was chemically induced by addition of glycerol to M. xanthus vegetative broth cultures (3, 19). Specifically, M. xanthus was inoculated into CYE broth and grown with aeration at 32 °C to an absorbance at 550 nm (A550) of 0.25–0.3. Sterile 10 m glycerol was added to 0.5 m final concentration and incubation continued as above for the indicated hours. To ensure good sporulation efficiency (∼90%), a growth medium to flask ratio of 1:12.5 with a shaking speed of 220 rpm (for 250 ml flasks) and 105 rpm (for 5-liter flasks) was used. To monitor sporulation, samples were withdrawn at various intervals after induction with glycerol and examined by differential interference contrast and/or light microscopy. Images were recorded with a Zeiss Axio Imager.M1 microscope (Carl Zeiss, Germany) equipped with a Cascade 1K camera (Visitron Systems, Germany).

To measure sporulation efficiency, cells were harvested by centrifugation (4618 × g for 10 min at 22 °C) 24 h after glycerol addition, resuspended in 500 μl of H2O, and dispersed with a FastPrep 24 cell homogenizer (MP Biomedicals, Solon, OH) for 20 s at 4.5 m/s. The spores were heated at 50 °C for 1 h and then sonicated twice using a Branson sonifier 250 (15 bursts, output 3; duty cycle 30%) with intermediate cooling. Spores were enumerated using a Helber bacterial counting chamber (Hawksley, UK). Sporulation efficiency was calculated as the number of heat- and sonication-resistant spores normalized to the number of vegetative cells immediately prior to glycerol addition (determined from the A550, where absorbance 0.7 = 4 × 108 cells ml−1). Sporulation efficiency was recorded as the average and associated standard deviation from three biological replicates and then normalized to the wild type (set at 100%).

Spore Coat Isolation

Spore coats were isolated from spores treated with glycerol for 4 h using a protocol modified from Ref. 3. 800 ml of spore culture were harvested (4618 × g for 10 min at 22 °C), and the pellets were frozen at −20 °C until use. The pellet was resuspended in 8 ml of 50 mm Tris buffer, pH 8.3, and 500-μl aliquots were added to 2-ml screw cap tubes containing 650 mg of 0.1-mm silica beads (Carl Roth, Germany). Spores were disrupted in a FastPrep 24 cell homogenizer (MP Biomedicals) six times at 6.5 m s−1 for 45 s, with 2 min cooling on ice between shaking. Complete cell lysis was confirmed by microscopy. Lysates were pooled and the volume recorded, and the protein concentration was determined by Bradford assay (Bio-Rad) according to manufacturer's instructions. Spore coat material was pelleted at 40,000 × g for 30 min at 4 °C (rotor MLA-55, Beckman Coulter, Brea, CA), washed twice with 7 ml of 50 mm Tris buffer, pH 8.3, resuspended in 3.3 ml of 100 mm ammonium acetate, pH 7, containing 200 μg ml−1 lysozyme, and incubated overnight (12–16 h) at 37 °C with shaking at 200 rpm. Spore coats were again pelleted as above, washed once, and resuspended in 7 ml of 50 mm Tris buffer, pH 8.3. 375.7 μl of 10% SDS and 35.7 μl of 20 mg ml−1 proteinase K were added, and the solution was incubated for 4 h at 37 °C with shaking at 220 rpm. The spore coats were pelleted as above, resuspended in 1% SDS, pelleted, washed twice with 7 ml of double distilled H2O, and resuspended in 300 μl of double distilled H2O.

Electron Microscopy

Samples were applied to glow-discharged carbon-coated 400 mesh copper grids and stained for 1 min at room temperature using either unbuffered 2% uranyl acetate or 1% phosphotungsten at pH 7.5. Excess stain was removed with a filter paper, and the grids were examined using a Philips CM12 microscope at an acceleration voltage of 80 kV. Images were recorded on Kodak ISO 165 black and white film at a nominal magnification of ×52,000.

Thin Layer Chromatography (TLC)

The isolated spore coat material was analyzed by TLC following modification of a protocol (20). The isolated spore coat material (∼4.5 mg) was acid-hydrolyzed by incubation in 3 m HCl at 105 °C for 3 h. To reduce the acidity, the samples were evaporated under vacuum until the volume was reduced to ∼20 μl and then diluted in 500 μl of water. This step was repeated. 2-μl samples corresponding to 0.2 mg of protein of the original lysate and 2 μl of a standard solution containing 10 mm each galactosamine, glycine, glutamate, and alanine were spotted onto a cellulose TLC plate and dried with a heat gun. The spots were resolved using a mobile phase consisting of n-butanol, pyridine, and hydrogen chloride (2.5:1.5:1). The TLC plate was dried with a heat gun, stained (25 mg of ninhydrin in 5:1 isopropyl alcohol/H2O), and then dried with a heat gun until colored spots appeared. Each of the three spots identified from the wild type sample was analyzed further by mass spectrometry. Briefly, areas corresponding to the relative position of the spots were cut from the unstained TLC plate and soaked in 20 μl of 80% acetonitrile, 0.04% TFA for 20 min at room temperature. 1 μl of the solvent was used for mass spectrometry analysis (4800Plus MALDI-TOF/TOF mass spectrometer, Applied Biosystems). An area of the TLC plate without sample material served as a negative control.

Glycosyl Composition Analysis

The glycosyl composition was determined by a combination of gas chromatography and mass spectrometry of acid-hydrolyzed per-O-trimethylsilyl derivates of the monosaccharides performed by the Complex Carbohydrate Research Center, Atlanta, GA. 200–400 μg of isolated spore coat material were supplemented with 20 μg of inositol as an internal standard and lyophilized. Methyl glycosides were then prepared from the dry sample by methanolysis in 1 m HCl in methanol at 80 °C (∼16 h), followed by re-N-acetylation with pyridine and acetic anhydride in methanol (for detection of amino sugars). The sample was then per-O-trimethylsilylated by treatment with Tri-Sil (Pierce) at 80 °C (0.5 h). These procedures were carried out as described previously (21). GC/MS analysis of the trimethylsilyl methyl glycosides was performed on an Agilent 6890N GC interfaced to a 5975B MSD, using a Supelco EC-1 fused silica capillary column (30 m × 0.25 mm inner diameter) (22). For each sample, the total mass, percent carbohydrate, and mass and corresponding molar percent of each carbohydrate detected were reported by the Complex Carbohydrate Research Center. The total mass and mass of each component were subsequently normalized to 108 cells as determined from the optical density of the culture prior to induction of sporulation (supplemental Table S2).

Glycosyl Linkage Analysis

For glycosyl linkage analysis, the spore coat polysaccharides were converted into methylated alditol acetates and analyzed by gas chromatography-mass spectrometry performed by the Complex Carbohydrate Research Center. 1.3 mg of isolated spore coat material was acetylated with pyridine and acetic anhydride and subsequently dried under nitrogen. The dried samples were suspended in 200 μl of dimethyl sulfoxide and stirred for 3 days. The polysaccharides were permethylated by treatment with sodium hydroxide for 15 min followed by the addition of methyl iodide in dry dimethyl sulfoxide for 45 min (23). The procedure was repeated once to ensure complete methylation of the polysaccharide. The polymer was hydrolyzed by the addition of 2 m TFA for 2 h at 121 °C. The carbohydrates were then reduced with NaBD4 and acetylated using a mixture of acetic anhydride and pyridine. The partially permethylated, depolymerized, reduced, and acetylated monosaccharides were then separated by gas chromatography (30-m RTX 2330 bonded phase fused silica capillary column) and analyzed by mass spectrometry using an Agilent 6890N GC interfaced to a 5975B MSD (21). All detected linkages from each residue were recorded as percent present. Detected GalNAc or Glc linkages were summed and reported as percent of total GalNAc or Glc; the average of two independent analyses was reported. Raw data and calculations are reported in supplemental Table S2.

Sucrose Density Gradient Fractionation

Vectors pCH20, pCH21, and pCH57 (for production of NfsAB, NfsD–G, and NfsC, respectively) were expressed in E. coli BL21 DE3. For Nfs protein expression, 1 liter of LB medium supplemented with spectinomycin or kanamycin was inoculated 1:100 with an overnight culture of each strain and grown at 37 °C with shaking. At A550 of 0.3, the cells were induced with 1 mm IPTG for 1 h. Cells were then harvested at 6000 × g for 20 min at 4 °C. The cells were washed with 10 ml of 10 mm HEPES buffer, pH 7.8, at 4 °C, and the cell pellet was frozen at −20 °C until use. Pellets were thawed on ice, resuspended in 10 ml of 10 mm HEPES buffer, pH 7.8, containing 100 μl of mammalian protease inhibitor mixture (Sigma), and lysed by French press three times at ∼20,000 p.s.i. Unlysed cells were removed by centrifugation at 3500 × g for 10 min at 4 °C. The cell lysate (2.2 ml) was loaded into Beckman tubes (number 355631, Beckman) containing a cold sucrose gradient consisting of 2.6 ml 55%, 4.8 ml 50%, 4.8 ml 45%, 4.8 ml 40%, 4.8 ml 35%, 4.8 ml 30%, and 2.6 ml 25% sucrose as per Refs. 24, 25. The gradient was centrifuged at 175,000 × g for ∼16 h at 4 °C in a swinging bucket rotor (Rotor SW-32Ti, Beckman). The 1.7-ml fractions were harvested from the gradient top and stored at −20 °C until use.

Proteins were precipitated from 1.6 ml of each fraction by addition of 216 μl of ice-cold 100% TCA followed by incubation on ice for 5 min and then centrifugation at 16,200 × g for 5 min at 4 °C. The protein pellets were washed with 2 ml of 100 mm Tris, pH 8, centrifuged as above for 5 min at 4 °C, and resuspended in 100 μl of 100 mm Tris, pH 8. 100 μl of 2× LSB sample buffer (0.125 m Tris, pH 6.8, 20% glycerol, 4% SDS, 10% β-mercaptoethanol) was added, and samples were incubated at 99 °C for 5 min. 5–20 μl of each these samples were analyzed on an 11% denaturing polyacrylamide gel (26), and the proteins were visualized by Coomassie stain (0.25% (w/v) ServaR, 50% ethanol, 7% acetic acid). As controls, samples corresponding to an A550 of 0.1–0.2 of uninduced whole cells, induced whole cells, and induced cell lysate were also analyzed. To identify fractions enriched for the cytoplasmic membrane, the NADH oxidase activity was determined in each fraction (24). NADH turnover was measured by addition of 25 μl of each gradient fraction to 500 μl of activity buffer (2.5 ml 1 m Tris adjusted with acetate to pH 7.9, 100 μl of 100 mm DTT, 22.4 ml of H2O) plus 375 μl of 0.1% NaHCO3. The solution was thoroughly mixed, and 100 μl of 0.2 mg ml−1 NADH (in 0.1% NaHCO3) was added. The solution was mixed by inversion, and the absorbance at 340 nm was measured every 6 s for 1 min in a quartz cuvette. The absorbance measurements were plotted and the slope (dA) of the graph was used to calculate the NADH oxidizing activity in units (U), as U = 68 × −0.1608 × dA.

Immunoblot Analysis

Immunoblot analysis was performed as described previously using antisera at the following dilutions: anti-NfsA (1:400), anti-NfsB (1:1000), anti-NfsC and anti-NfsD (1:100), anti-NfsE (1:625), and anti-NfsG (1:500) (5). Anti-NfsC and -NfsE antisera were purified (27) prior to use.

RESULTS

EPS and/or O-antigen Co-purify with Spore Coat Sacculi but Are Not Essential Spore Components

To understand how Exo and Nfs proteins function to secrete and assemble the spore coat, we set out to examine how strains bearing deletions in these machineries affected spore coat composition and structure. For these analyses, we started with the isolation and characterization of wild type spore coat material using adaptations of a previously described protocol (3) in which cells were chemically induced to sporulate by treatment with 0.5 m glycerol for 4 h. With this protocol, wild type spores yielded ∼148 μg of isolated material per 108 cells (Table 2). To examine the appearance of the isolated material, a portion of the sample was examined by negative stain electron microscopy. Similar to previous reports (3, 8), wild type spore coats appeared as distinct spherical sacculi-containing lesions, which were likely due to the mechanical disruption of the spores during coat isolation (Fig. 1, wt).

TABLE 2.

Glycosyl composition in spore coat material isolated from strains bearing the indicated genotypes

| Genotype (strain) | μg of material per 108 cells |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WT (DK1622) | wzm epsV (PH1285) | ΔexoC (PH1261) | ΔexoC wzm epsV (PH1296) | Δnfs (PH1200) | |

| Dry weight | 148 | 89 | 46 | 8 | 180 |

| Estimated % carbohydrate | 92 | 81 | 64 | 30 | 85 |

| (N-Acetyl)galactosamine | 94 | 61 | NDa | ND | 113 |

| Glucose | 24 | 7 | 20 | 3 | 28 |

| (N-Acetyl)glucosamine | 8 | 5 | 3 | ND | 5 |

| Xylose | 5 | ND | 3 | ND | 3 |

| Rhamnose | 5 | ND | 3 | ND | 4 |

| Mannose | 1 | ND | <1 | ND | <1 |

| Galactose | <1 | ND | <1 | ≪1 | <1 |

a ND means none detected.

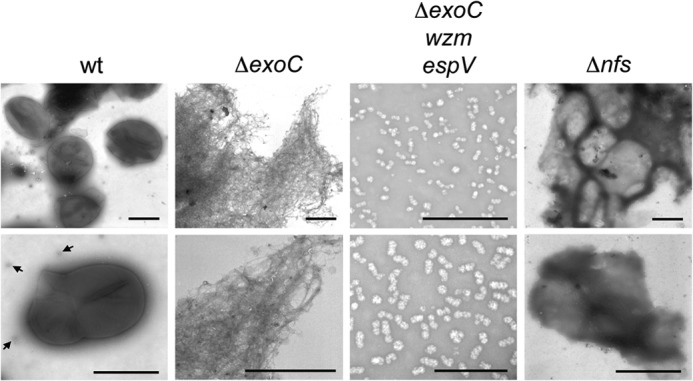

FIGURE 1.

Negative stain electron microscopy of material isolated during spore coat purification. Wild type (wt; strain DK1622), ΔexoC (PH1261), ΔexoC wzm epsV (PH1296), and ΔnfsA-H (Δnfs; PH1200) cells were induced to sporulate for 4 h by addition of glycerol and subjected to a spore coat isolation protocol. Representative pictures at lower (top panels) and higher (bottom panels) magnifications are shown. Bar corresponds to 1 μm for WT, ΔexoC, and ΔnfsA-H panels, and 500 nm for ΔexoC wzm epsV panels. Arrows point to particles in the wild type similar to those isolated from the ΔexoC wzm epsV mutant.

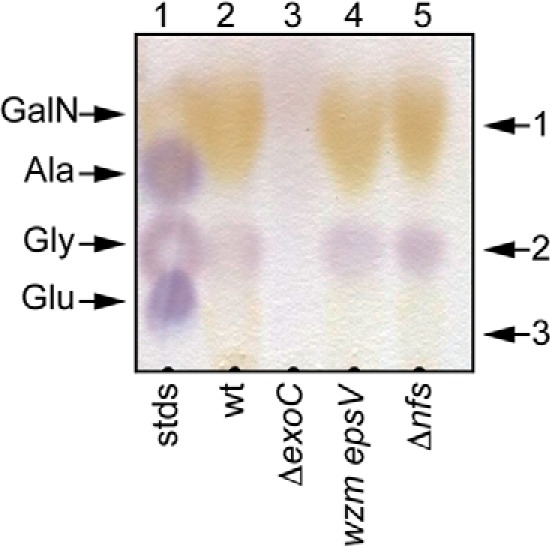

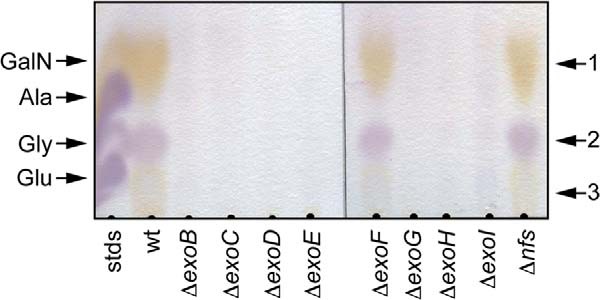

Previous analyses suggested that the wild type spore coat material contained high amounts of the carbohydrates N-acetylgalactosamine (GalNAc) and glucose (Glc) as well as the amino acids glycine (Gly) and alanine (Ala) (3, 8). To confirm the carbohydrate composition of the wild type spore coat, ultimately to enable comparison with our mutant strains, we first examined the wild type material by acid hydrolysis followed by thin layer chromatography. Resolved samples were stained with ninhydrin to detect amino acids and amino sugars (Fig. 2). As controls, glutamate (Glu), Gly, Ala, and GalN standards were separately analyzed (data not shown) or mixed and applied in a single lane (Fig. 2, lane 1). Three spots could be identified in wild type spore coat preparations as follows: 1) a yellow-stained spot (Rf = 0.19) corresponding to the GalN control; 2) a purple spot (Rf = 0.06) corresponding to the Gly control; and 3) an additional yellow spot (Rf = 0.04), which did not co-migrate with any of the standards (Fig. 2, lane 2). Each spot was scraped from the TLC plate and analyzed by mass spectrometry. Single compounds of 180.8 Da (spot 1) and 76.03 Da (spot 2) were detected; these corresponded exactly to the predicted masses of a protonated hexosamine and Gly, respectively. No compound could be detected for spot 3. Although previous analyses suggested Glc as a component of the spore coat (3), it was not detected by the ninhydrin stain as it does not contain reactive amino groups.

FIGURE 2.

Amino acid and amino sugar composition of the material recovered in a spore coat isolation protocol. Wild type (wt; DK1622), ΔexoC (PH1261), wzm epsV (PH1285), and ΔnfsA-H (Δnfs; PH1200) cells were induced to sporulate for 4 h by addition of glycerol. Material was isolated and acid-hydrolyzed, and a sample volume corresponding to 0.2 mg of protein per lane was loaded on a cellulose TLC plate and stained with ninhydrin. Marker, 2 μl of 10 mm each glutamate, glycine, alanine, and galactosamine in water. Spots 1–3, which were further analyzed by mass spectrometry, are indicated to the right.

To assay the Glc content, and to obtain higher resolution and quantitative glycosyl composition of the spore coat material, the sample was additionally analyzed by combined gas chromatography/mass spectrometry (GC/MS) of per-O-trimethylsilyl derivatives of monosaccharides produced by acid hydrolysis (performed at the Complex Carbohydrate Research Center). These analyses indicated the isolated wild type spore coat consisted of ∼92% carbohydrate material containing predominantly GalNAc (64 mol %) and Glc (20 mol %) with lesser amounts of N-acetylglucosamine, rhamnose, xylose, mannose, and galactose (Table 2 and supplemental Table S2). It should be noted that because of the initial methanolysis and re-N-acetylation procedure, N-acetylation of all the spore coat glucosamine pool was assumed; acetylation is consistent with previous labeling studies demonstrating incorporation of labeled acetate into the spore coat (28) (a modification that is lost during the acid hydrolysis step in the TLC analysis in Fig. 2).

Previous studies have demonstrated that almost all of the carbohydrate subunits identified in our analyses have been shown to be part of at least one of the two other cell surface polysaccharides of M. xanthus as follows: the EPS and the O-antigen (O-Ag) component of the lipopolysaccharide (LPS) (29, 30). To determine whether O-Ag or EPS plays an essential role as a source of the spore coat components, or whether these components arise as a contamination due to co-purification, we generated a double mutant bearing disruptions in genes that have previously been shown to be necessary for O-antigen (wzm) (31) and EPS (epsV) synthesis (32). The wzm epsV double mutant formed as many heat- and sonication-resistant spores as the wild type (163 ± 37% versus 100 ± 20%, respectively) suggesting that neither of these products are essential for formation of resistant spores. Isolation of spore coat material from the wzm epsV mutant yielded ∼89 μg per 108 cells corresponding to ∼60% of the material isolated from the wild type (Table 2 and supplemental Table S2). Examination of spore coat components by acid hydrolysis and ninhydrin-stained TLC revealed the same three spots identified in the wild type (Fig. 2, lane 4 versus lane 2) suggesting a similar coat composition. However, quantitative glycosyl analysis indicated that the wzm epsV double mutant sample contained ∼29, 65, and 58% of the wild type Glc, GalNAc, and GlcNAc amounts and none of the rhamnose, xylose, mannose, and galactose (Table 2 and supplemental Table S2). Together, these results suggested that some of the Glc and GalNAc identified in the spore coat material, as well as all of the rhamnose, xylose, mannose, and galactose likely come from contamination with O-Ag and/or EPS during the isolation procedure. The remaining GlcN(Ac) likely comes from peptidoglycan remnants (given that ManNAc is unstable and degraded during the analysis).

ExoC Protein Is Necessary for Export of GalNAc-, Glc-, and Gly-containing Material

Our previous data indicated that ExoC, a predicted polysaccharide co-polymerase (Table 3 and Fig. 6), is necessary for secretion of spore coat material to the cell surface (5). To confirm these data and to identify specifically which components may be secreted by ExoC, we followed a similar protocol for spore coat isolation and characterization as described for the wild type above. Consistent with the lack of spore coat material observed in our previous study, only ∼46 μg of material per 108 cells (∼31% of wild type material) could be isolated from the ΔexoC mutant (Table 2). Negative stain EM demonstrated that the ΔexoC sample consisted primarily of fibrous material associated with ring-like structures (Fig. 1, ΔexoC); importantly, no sacculi could be detected. When this material was subjected to analysis by ninhydrin-stained TLC, none of the three spots observed in the wild type sample could be detected (Fig. 2, lane 3), suggesting that exoC is necessary for incorporation of at least GalNAc and glycine into the spore coat.

TABLE 3.

Predicted characteristics of the Exo proteins

| Gene | Locus ID | Predicted function (predicted domain accession; expect value)a | Localizationb |

|---|---|---|---|

| exoA | MXAN_3225 | Polysaccharide biosynthesis/export (COG1596, 1.4e−33) | OM (11) |

| exoB | MXAN_3226 | Hypothetical protein | OM |

| exoC | MXAN_3227 | Chain length determinant family (COG3206; 1.1e−20) | CM |

| exoD | MXAN_3228 | Tyrosine kinase (TIGR03018; 6.5e−37) | S |

| exoE | MXAN_3229 | Polyprenyl glycosylphosphotransferase (TIGR03025; 7.1e−114) | CM |

| exoF | MXAN_3230 | YvcK-like (cd07187; 3.4e−126) | S |

| exoG | MXAN_3231 | N-Acetyltransferase (GNAT) (pfam13480; 2.3e−32) | S |

| exoH | MXAN_3232 | 3-Amino-5-hydroxybenzoic acid synthase family (cd00616; 6.6e−29) | S |

| exoI | MXAN_3233 | N-Acetyltransferase (GNAT) (pfam13480; 6.9e−33) | S |

FIGURE 6.

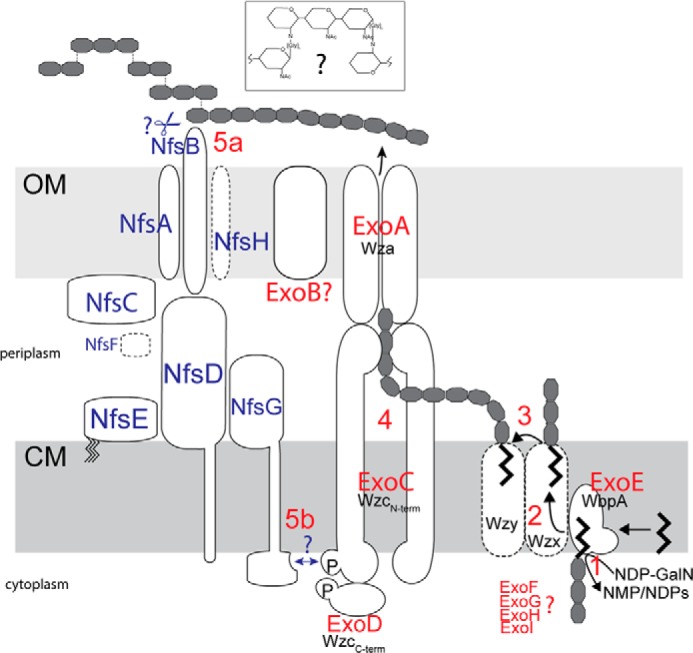

Working model of spore coat production and assembly in M. xanthus. GalNAc and Glu (11–17:1) polymers are synthesized and secreted to the cell surface by the Exo proteins (red text) and assembled into a stress-bearing structure by the Nfs proteins (blue text). The Exo proteins resemble a Wzy-dependent capsule secretion machinery; respective homologs are identified in black text. The polyisoprenoid lipid undecaprenol diphosphate (und-PP)-linked carbohydrate repeat units are generated on the inner surface of the cytoplasmic membrane (CM) by ExoE and the ExoF–I processing enzymes (step 1), translocated to the outer surface of the CM by an unidentified flippase (Wzx) (step 2), and polymerized by Wzy (likely MXAN_3026) (5) (step 3). Polymers are secreted to the cell surface by the terminal export complex consisting of ExoC/D and ExoA (step 4). The Nfs proteins are located in either the OM or CM as indicated. NfsG interacts with the AglQRS energy-harvesting complex (13) (data not shown). The Nfs proteins are necessary for assembly of the capsule-like carbohydrates into a rigid sacculus in a process that involves an apparent increase in the proportion of terminal Glc and GalNAc residues. This process may involve cleavage of polysaccharides chains on the cell surface (step 5a) or influence polysaccharide extrusion via interaction with ExoC/D (step 5b). See text for details. Inset, a possible arrangement of the spore coat in which glycine peptides (Glyn) replaces the acetyl group in certain GalNAc residues to bridge to the C1 carbon of an adjacent glycan. See text for details.

To determine specifically which components were lacking in the ΔexoC mutant, we next subjected the material isolated from ΔexoC spores to quantitative glycosyl analysis. This material consisted of less carbohydrate (approximately two-thirds of the wild type percent carbohydrate) suggesting that ΔexoC reduced total carbohydrates isolated but did not necessarily affect other spore coat components. Consistent with the TLC analyses, no GalNAc could be detected (Table 2). Interestingly however, ∼80% of the wild type Glc could still be detected. To further resolve whether ExoC is necessary for export of Glc or whether the remaining Glc arises from O-Ag and/or EPS, we generated a triple mutant bearing the epsV and wzm interruptions in the ΔexoC background. As expected, the chemically induced sporulation phenotype of this triple mutant phenocopied that of the single ΔexoC mutant; upon induction of sporulation, the cells rearranged to enlarged spheres that either failed to mature into phase bright and -resistant spores or reverted to rods (data not shown). The spore coat isolation protocol yielded ∼8 μg of material per 108 ΔexoC epsV wzm cells, corresponding to 9 and 18% of the material isolated from the epsV wzm and ΔexoC mutants, respectively (Table 2 and supplemental Table S2). Negative stain EM demonstrated that in contrast to the fibrous-like material observed in the isolated ΔexoC material (Fig. 1, ΔexoC), the ΔexoC wzm epsV material consisted entirely of kidney-shaped globules (Fig. 1, ΔexoC wzm epsV). Quantitative glycosyl analysis indicated that this sample consisted of one-third less carbohydrate relative to the wild type of which 99.8 mol % was Glc (Table 2 and supplemental Table S2). The kidney-like shape and composition of this material are strikingly similar to glycogen granules previously characterized in other bacteria such as Nostoc musorum (33) suggesting that in the absence of all these export systems, the remaining isolated carbohydrate arises from glycogen that has previously been shown to accumulate prior to the onset of sporulation in M. xanthus (34). Furthermore, such granules could also be observed in the wild type EM analyses (arrows, Fig. 1, wt lower panel). Together these results suggest that the majority of the Glc observed in the spore coat material is due to contamination with EPS/O-Ag and cytoplasmic glycogen.

ExoB-E and -G–I Are Essential for Spore Coat Synthesis

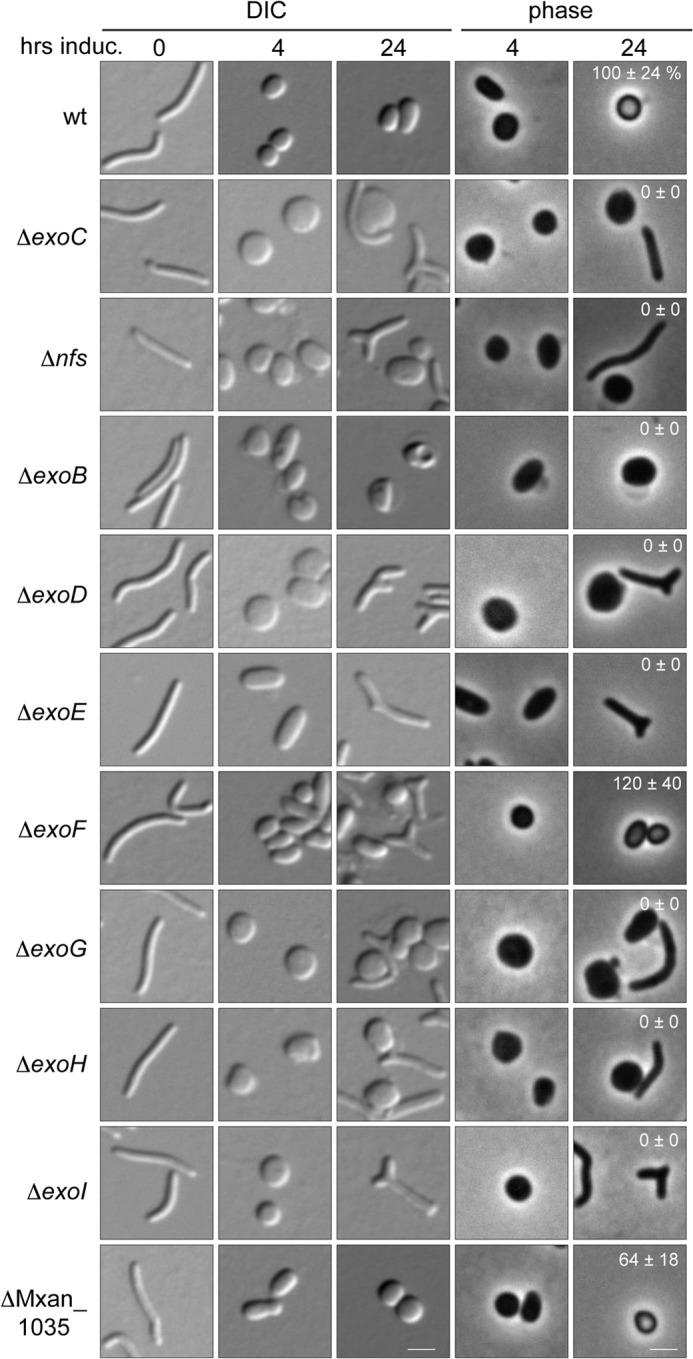

Our composition analysis suggested that at least ExoC is necessary to export spore coat polysaccharides containing GalNAc and Gly. However, exoC is encoded within an operon containing eight additional genes, exoA–I (Table 3 and Fig. 6) (5), and polysaccharide synthesis systems are often clustered and co-transcribed (35). To further define the system necessary to export spore coat material, we generated single in-frame deletion mutants of exoB, exoD, exoE, exoF, exoG, exoH, and exoI and tested the mutants for production of resistant spores; exoA deletion mutants have previously been analyzed (36). For each of these strains, as well as the control ΔexoC, ΔnfsA–H, and wild type strains, broth cultures were chemically induced to sporulate, and the cell morphology was examined by differential interference contrast (t = 0, 4, and 24 h) and phase contrast (t = 4 and 24 h) microscopy (Fig. 3). The wild type rod-shaped cells (t = 0) rearranged to spheres by 4 h after induction and became phase bright between 4 and 24 h after induction. In contrast, the ΔexoB, -D, -E, and -G–I mutants phenocopied the ΔexoC and ΔnfsA–H mutants; cells formed enlarged spheres that failed to turn phase bright and sometimes reverted to misformed rod-shaped cells. ΔexoF mutants showed a partial phenotype in that some cells became misformed after induction, but the mutant produced similar numbers (120 ± 40%) of phase bright-resistant spores as the wild type (100 ± 24%).

FIGURE 3.

Sporulation phenotype of mutants bearing individual exo gene deletions. Vegetative cells from WT (wt; DK1622), ΔexoC (PH1261), ΔnfsA–H (Δnfs; PH1200), ΔexoB (PH1303), ΔexoD (PH1304), ΔexoE (PH1265), ΔexoF (PH1507), ΔexoG (PH1508), ΔexoH (PH1264), ΔexoI (PH1511), and ΔMXAN_1305 (PH1509) were induced (induc) for sporulation with glycerol and examined by differential interference contrast (DIC) and phase microscopy at the indicated hours. Bar, 2 μm. The sporulation efficiency after 24 h of induction is displayed in white text (24-h phase pictures) as the average and associated standard deviation of three biological replicates.

To examine whether these mutants were defective in spore coat production, spore coat material was isolated from each of the single mutants, acid-hydrolyzed, and examined by ninhydrin-stained TLC. No spots corresponding to GalN(Ac) or glycine could be detected in ΔexoB–E and -G–I mutants, although ΔexoF mutants produced all spots with intensity similar to the wild type (Fig. 4). These results suggest that, with the exception exoF, all other exo genes are essential for export of a polysaccharide containing at least GalNAc and Gly.

FIGURE 4.

Amino acid and amino sugar composition of spore coat material recovered from individual exo mutants. Wild type (wt; DK1622), ΔexoB (PH1303), ΔexoD (PH1304), ΔexoE (PH1265), ΔexoF (PH1507), ΔexoG (PH1508), ΔexoH (PH1264), ΔexoI (PH1511), ΔexoC (PH1261) and ΔnfsA-H (Δnfs; PH1200) cells were induced to sporulate for 4 h by addition of glycerol. Material was isolated and acid-hydrolyzed, and a sample volume corresponding to 0.2 mg of protein per lane was loaded on a cellulose TLC plate and stained with ninhydrin. Marker, 2 μl of 10 mm glutamate, glycine, alanine, and galactosamine in water.

ExoA and ExoC/D belong to the Group C OPX and PCP-2a-like proteins, respectively, that form a terminal export complex for exopolysaccharides (Fig. 6), and these groups are predicted to be coupled to Wzy-dependent polymer biosynthesis pathways (11). In Wzy-dependent pathways, the polyisoprenoid lipid undecaprenol diphosphate-linked repeat units are generated at the inner leaflet of the cytoplasmic membrane and then moved to the outer leaflet of the inner membrane by a flippase (Wzx) homolog (Fig. 6). No flippase homologs could be identified in the exo locus (Table 3), but two homologs (MXAN_1035 and MXAN_7416) were located elsewhere in the genome. To test whether either of these genes is necessary for spore production, we attempted to generate in-frame deletions of each and to analyze the chemically induced sporulation phenotype of the resultant strains. The ΔMXAN_1035 mutant produced spherical cells that became phase bright with the same timing and morphology as the wild type, but sporulation efficiency was reduced to 64 ± 18% of the wild type (Fig. 3). These results suggested that MXAN_1035 may function as a flippase with the Exo machinery but that its function is partially redundant. We were unsuccessful in generating a deletion of MXAN_7416 and were therefore unable to examine whether this gene was involved in spore coat synthesis.

NfsA–H Mutant Cells Produce Intact Spore Coat Sacculi Composed of GalNAc, Glc, and Gly

We next turned our attention to the role of the Nfs proteins (Fig. 6) in assembly of a compact spore coat. Our previous analyses indicated that the ΔnfsA–H mutant produced loosely associated and unstructured spore coat material on the surface of the cell, which could not function as a stress-bearing layer (5). To further define the function of the Nfs proteins, we set out to characterize how the nfs mutant spore coat material differed from that of the wild type using approaches outlined for the wild type and exoC mutant. Using the spore coat isolation protocol, we obtained ∼180 μg per 108 cells, corresponding to 121% of wild type material (Table 2 and supplemental Table S2). Interestingly, negative stain electron microscopy analysis revealed that obvious spore coat sacculi could be identified, although they appeared more unstructured than the wild type and tended to clump together (Fig. 1, Δnfs). These results suggested that the nfs mutant produced an intact spore coat sacculus but that the composition or structure of the material is likely different from that of the wild type.

To address whether the composition of the nfsA–H spore coat material differed from that of the wild type, we subjected the material to acid hydrolysis followed by ninhydrin-stained TLC. All three spots observed in the wild type sample (corresponding to GalN, Gly, and the unidentified component) could be detected in the nfsA–H mutant (Fig. 2, lane 2 versus lane 5). Quantitative glycosyl composition analyses suggested that the total amount of GalNAc and Glc was increased to 121 and 113%, respectively, of the wild type (Table 2 and supplemental Table S2). An independent biological replication of these analyses confirmed that the nfs mutant produced more total material and similarly increased relative levels of GalNAc and Glc over the wild type (data not shown). The molar ratio of GalNAc to Glc in the nfs mutant was 3.4 ± 0.1 compared with the wild type ratio of 2.8 ± 0.5 (data not shown). These data indicate that the spore coat of the nfs mutant does not lack a component of the spore coat but that the Nfs complex is necessary for accumulation of appropriate levels of the spore coat material.

nfs Locus Is Necessary for Polysaccharide Chain Length Processing

Given that the nfsA–H mutant produced all the major spore coat components detected in the wild type, we next set out to determine whether the amorphous appearance of the spore coat could be a result of structural differences in polysaccharide arrangement. For this analysis, we first examined the linkages of the GalNAc and Glc residues in the spore coat material in the wild type and nfs mutant. Briefly, spore coat material was permethylated, acid-hydrolyzed, and then acetylated such that free hydroxyl groups in the residue can be distinguished from those in glycosidic bonds by methylation versus acetylation, respectively. The resulting monosaccharides were then analyzed by GC/MS to determine the relative derivative positioning.

Using this method, we first examined the wild type spore coat material and determined that GalNAc residues were 1–4-linked (44 ± 3%), 1–3-linked (15 ± 2%), or terminal (t) (41 ± 0%) (Table 4 and supplemental Table S2). Glc residues were primarily identified as 1–4-linked (64 ± 3%), 1–6-linked (6 ± 3%), and terminal (26 ± 2%). None of the GalNAc and very little of the Glc (≤2%) molecules had more than one linkage suggesting no detectable branching. Furthermore, relatively high proportions of terminal GalNAc and Glc residues were observed suggesting the chain length is relatively short. Interestingly, the ΔnfsA–H mutant spore coat material contained the same type of GalNAc and Glc linkages, but the proportion of internal residues was increased at the expense of terminal residues; GalNAc linkages detected were 1–4-linked (63 ± 8%), 1–3-linked (32 ± 5%), or terminal (3 ± 1%), and Glc linkages detected were 1–4-linked (83 ± 6%), 1–6-linked (2 ± 0%), or terminal (12 ± 3%) (Table 4 and supplemental Table S2). Thus, the ratio of terminal to internal residues was decreased in the nfs mutants suggesting that the glycan chain length is longer than in the wild type. These data suggest that the Nfs proteins may be involved in chain length determination.

TABLE 4.

Glucose (Glc) and N-acetylgalactosamine (GalNAc) linkages identified in spore coat material isolated from wild type ΔnfsA–H (Δnfs) strains

Average and standard deviations of two independent analyses from independent biological replicates are shown. ND means none detected.

| Residue | Genotype (strain) |

|

|---|---|---|

| WT (DK1622) | Δnfs (PH1200) | |

| GalNAc | 100 | 100 |

| t-GalNAc | 41 ± 0 | 3 ± 1 |

| 4-GalNAc | 44 ± 3 | 62 ± 8 |

| 3-GalNAc | 15 ± 2 | 32 ± 5 |

| 3,4-GalNAc | ND | 1 ± 1 |

| 4,6-GalNAc | ND | 1 ± 2 |

| Glc | 100 | 100 |

| t-Glc | 26 ± 2 | 12 ± 3 |

| 6-Glc | 6 ± 3 | 2 ± 0 |

| 4-Glc | 64 ± 3 | 83 ± 6 |

| 3,4-Glc | 1 ± 2 | 1 ± 1 |

| 2,4-Glc | 1 ± 1 | 1 ± 1 |

| 4,6-Glc | 2 ± 0 | 1 ± 1 |

| 2,3,4,6-Glc | ND | 1 ± 1 |

Nfs Proteins Associate with the Inner and Outer Membrane

We hypothesized that the Nfs proteins could mediate polysaccharide chain length either by affecting the synthesis of polysaccharides, which occurs at the cytoplasmic membrane, and/or by rearranging the polysaccharides after they have been secreted to the cell surface. To begin to distinguish between these possibilities, we set out to determine the exact compartment localization of the individual Nfs proteins. Because we have previously shown that NfsA–E and -G fractionate with the M. xanthus cell envelope (5), we now examined whether these proteins fractionate with the cytoplasmic or outer membranes.

We were unable to adapt other previously employed methods for separating M. xanthus OM and CM membranes, such as outer membrane isolation (37) or sucrose density gradient fraction (38), likely because the envelope characteristics of sporulating cells differs significantly from that of the vegetative cells for which they were developed. Therefore, we set out to examine the localization patterns of the Nfs proteins produced heterologously in E. coli with the well defined and rigorous sucrose density gradient fractionation protocol (24, 39). For this approach, the nfs operon was separated in two fragments (nfsA–C and nfsD–H) and cloned behind the IPTG-dependent T7 promotor of the pCDF (generating pCH20) and pCOLA (generating pCH21) plasmids, respectively. Each plasmid was induced with IPTG alone or together in E. coli BL21(DE3). Optimal production of NfsA, -B, -D, -E, and -G could be detected when pCH20 and pCH21 were expressed independently, but NfsC, NfsF, and NfsH could not be detected (data not shown). Optimal production of NfsC could be detected if nfsC was cloned alone into pCDF (generating pCH57) and expressed alone (data not shown). NfsF and NfsH could not be detected likely because of the quality of the antisera (5).

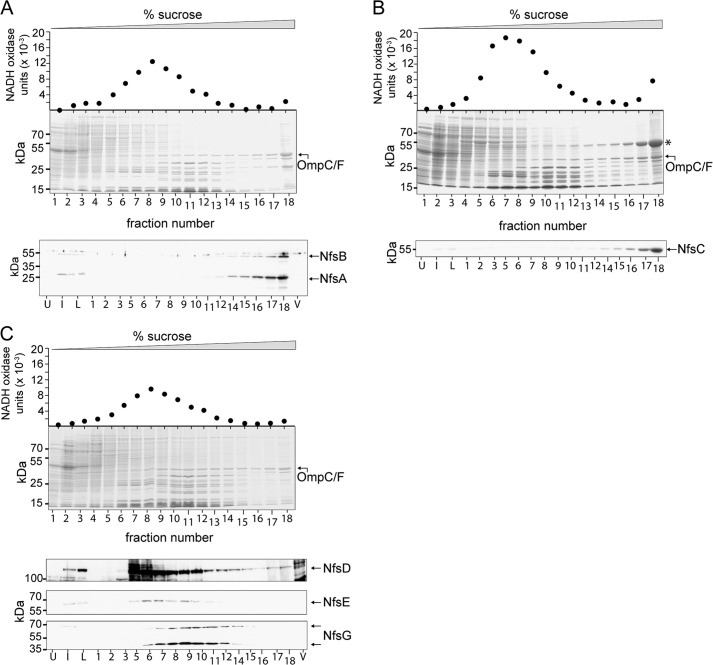

To examine the localization patterns of the NfsA and -B proteins, cell lysates from IPTG-induced E. coli BL21 expressing pCH20 were applied to a 25–55% sucrose step gradient and centrifuged to allow CMs and OMs to separate. To determine the relative position of OMs, each fraction was resolved by SDS-PAGE, stained by Coomassie Blue, and examined for the characteristic pattern of the E. coli OmpF/C proteins (Fig. 5A, lanes 15–18). To identify CM proteins, each fraction was assayed for peak NADH oxidase activity (Fig. 5A, lanes 7–11). To identify the localization of NfsA and -B, each fraction, as well as uninduced and induced whole lysates, was subjected to immunoblot analysis with anti-NfsA and anti-NfsB sera (Fig. 5A). NfsA (32 kDa) and NfsB (47 kDa) were identified in induced, but not uninduced, whole cells and in fractions 14–18 consistent with OM localization (Fig. 5A). To examine the localization pattern of NfsC, cell lysates from E. coli BL21(DE3)-expressing pCH57 were analyzed as described above, resulting in detection of NfsC in the induced, but not uninduced, whole cell fractions and in fractions 14–18, concurrent with the OmpC/F OM marker proteins (Fig. 5B). Finally, to examine the localization patterns of NfsD, -E, and -G, cell lysates from E. coli BL21(DE3)-expressing pCH21 were analyzed as described above, resulting in detection of NfsD, NfsE, and NfsG in the induced, but not uninduced, whole cell lysates and in fractions 7–12, consistent with the CM marker peak NADH oxidase activity. NfsG was detected at two co-fractionating bands suggesting the protein was partially degrading after cell lysis. These analyses strongly suggest that NfsA, consistent with its predicted β-barrel porin-like structure, NfsB, and NfsC, are OM-associated proteins, although NfsD, NfsE, and NfsG are CM-associated proteins (Fig. 6).

FIGURE 5.

Membrane localization of Nfs proteins produced in E. coli. Sucrose density gradient fractionations of E. coli BL21DE3 cells producing NfsA and -B (A), NfsC (B), or NfsD, -E, and -G (C) from plasmids pCH20, pCH57, and pCH21, respectively. A–C, top graph, NADH oxidase activity as a marker for cytoplasmic membrane fractions measured in the indicated fractions. Middle panel, total proteins from each indicated fraction resolved by denaturing PAGE followed by Coomassie stain. OmpC/F are indicated as a marker for outer membrane fractions. Asterisk represents NfsC in B. Bottom panel(s), immunoblot analysis of the indicated fractions probed with anti-NfsA and anti-NfsB antisera (A), anti-NfsC antisera (B), and anti-NfsD, anti-NfsE, or anti-NfsG sera (C) as indicated in the fractions indicated. Proteins from uninduced (U) and induced (I) whole cells from lysates of induced cells expressing the respective plasmid (L) or empty vector (V) are shown. NfsG is detected as full-length (top arrow) and degradation product (bottom arrow).

DISCUSSION

The goal of this study was to characterize the production of the M. xanthus spore coat, a remarkable cell wall-like structure that surrounds the outer membrane of sporulating M. xanthus cells and provides structural stability to the spore (5, 13). To begin to characterize this process, our approach was to take advantage of mutants in the exo and nfs operons, which we have previously shown encode proteins necessary for secretion and assembly of the spore coat, respectively (5). Thus, we performed a comparative analysis of spore coat material in these mutants versus the wild type.

Structure of the Spore Coat

Early composition analysis of the spore coat determined it consists primarily of carbohydrates (79%) with lesser amounts of protein (14%) but relatively high amounts of glycine (7%) (3). Specifically, it was proposed that the carbohydrate material consisted of GalNAc and Glc in a molar ratio of 3:1 and that Glc may form an independent polymer. Our current analyses refine these early observations. Quantitative GC/MS analysis of acid-hydrolyzed purified material confirmed that GalN (likely acetylated) and Glc are the primary carbohydrate components and can be detected in a molar ratio of 3.2:1 (supplemental Table S2). However, our further analyses suggest that the actual GalNAc/Glc ratio is much higher because the majority of the Glc (∼71%) arises from contamination with co-purifying EPS, O-Ag, or cytoplasmic storage compounds, such as glycogen (34). Although we had previously considered that the two surface polysaccharides may serve as essential components of the spore coat (either as attachment sites or saccharide sources), our observation that a mutant unable to produce EPS or O-Ag (wzm epsV) can produce resistant spores with equal efficiency as the wild type suggests they are merely contaminating substances. Consistently, the small amount of material that can be purified from the spore coat-deficient exoC mutant (5) consists of fibers that are reminiscent of isolated EPS (fibrils) (Fig. 1) (29). Furthermore, the material isolated from a triple mutant defective in spore coat and EPS/O-Ag (exoC wzm epsV) (Table 2) contained only glycogen-like particles (Fig. 1) (33) composed almost entirely (>99 mol %) of glucose (supplemental Table S2). We could detect similar particles in the wild type spore coat preparations (Fig. 1, wt, indicated by arrows), and we suggest that the co-purifying EPS-like fibers may have been trapped inside the wild type spore coat sacculi. Together, then, our results suggest that of the ∼24 μg of Glc isolated from 108 wild type cells, ∼17 μg (∼70%) arise from EPS/O-Ag (μg GlcWT − μg Glcwzm epsV), ∼4 μg (∼18%) arise from the spore coat (μg GlcWT − μg GlcexoC), and ∼2 μg (∼10%) arise from storage compounds (μg GlcexoC wzm epsV). Given that no GalNAc can be detected in the exoC mutant, we assumed that all of the isolated GalNAc arises from the spore coat material specifically. Inconsistent with this assumption, however, is the ∼35% reduction of GalNAc observed in the wzm epsV mutant compared with the wild type (61 μg versus 94 μg GalNAc per 108 cells, respectively), which could suggest that some of the GalNAc arises from EPS and/or O-Ag. One possible interpretation of this discrepancy is that ExoC contributes to GalNAc incorporation into EPS and/or O-Ag synthesis. If this is the case, the interpretation is that the spore coat material contains 61 μg of GalNAc per 108 cells, with the molecular ratio of GalNAc/Glc at 11:1 (supplemental Table S2). Alternatively, the reduction of GalNAc observed in the wzm epsV mutant may simply be an artifact arising from competition for the undecaprenyl diphosphate pool, which, in the exoC mutant, may be sequestered as spore coat precursors. In this case, we could assume the wild type spore coat contains 94 μg of GalNAc per 108 cells, and the molecular ratio of GalNAc/Glc is closer to 17:1; this is the interpretation we favor.

Consistent with early composition analysis (3), we could demonstrate that glycine (Gly) is readily detected in the spore coat material if the sample is analyzed by TLC. Interestingly, however, Gly could not be detected in the GC/MS analysis (Table 2 and data not shown). In the procedure used for GC/MS analysis, the lyophilized spore coat is first subjected to acid methanolysis, re-N-acetylated, and then per-O-trimethylated to volatilize components for gas chromatography. One possibility is that the Gly is lost early in the hydrolysis procedure. This could occur if the Gly was attached via an amide bond to at least a portion of the GalN (in replacement of the acetyl group; Fig. 6, inset). Such a configuration has been proposed for the heteropolysaccharide in the sheath of Leptothrix cholodnii (40). We hypothesize that in the GC/MS procedure, the initial hydrolysis step would remove the Gly (or acetyl group), and subsequently, due to the re-acetylation step, be detected only as GalNAc. In the TLC protocol, Gly or Ac groups removed during the acid hydrolysis step remain in the reaction mixture such that Gly is detected by ninhydrin stain. This hypothesis is consistent with the following observations: 1) Gly is intimately connected with the polysaccharide synthesis and secretion because no Gly could be detected in the exoC mutant (this study), and 2) Gly incorporation into spore coat material is sensitive to bacitracin, which suggests it requires a lipid-pyrophosphate carrier (28).

To begin to understand how the spore coat components could be arranged to form a cell wall-like matrix, we performed linkage analysis on the glycosyl components of the spore coat and then focused on the GalNAc and Glc units. Linkage analysis revealed that the wild type isolated spore coat material contained GalNAc in t-, 1–4-, or 1–3-linkages in a ratio of 1:1:0.4 (supplemental Table S2). Glc residues were detected primarily as t-Glc, and 1–4-Glc, in a ratio of 1:2.4 (supplemental Table S2). The high proportion of terminal to internal residues, together with no detected O-glycosidic branching, suggests the glycans are surprisingly short. With these data alone, we were unable to ascertain exactly how long the chains may be because it is unknown which proportions of these linkages are due to contaminating Glc and GalNAc from the EPS/O-Ag and glycogen, and because it is unknown whether the Glc and GalNAc are both present in a single polymer. It has been previously proposed that the GalNAc and Glc form independent polymers based on the observation that later during sporulation, the Glc content continued to accumulate while GalNAc remained constant (3). In the light of our observation that the majority of the Glc arises from contamination with non-spore coat polysaccharides, we suggest that this may have been due to the continued accumulation of glycogen.

Because the spore coat material is insoluble and highly resistant to enzymatic digestion (3), we did not ascertain its three-dimensional structure. Furthermore, initial attempts to isolate the lipid carrier-linked polysaccharide subunit, which is likely used to synthesize the polysaccharide (see discussion on Exo below), were so far unsuccessful. Nevertheless, we propose that the conspicuous absence of significant dual linked Glc or GalNAc residues suggests no branching and implies that the individual polymers are not connected via O-glycosidic bonds. To form a rigid sacculus, the spore coat glycans are likely tightly associated. How could this be mediated? In plant or fungal cell walls, the respective Glc (cellulose) or GlcNAc (chitin) polymers are held together by hydrogen bonds from the hydroxyl or amine groups (41, 42). In contrast, in peptidoglycan, glycan strands are connected via peptide bridges (43). Because a high proportion of Gly is present in the spore coat, we favor a structure in which the adjacent glycans chains are connected by Gly peptides. Although in peptidoglycan the peptide bridges are connected to the 3 carbon of ManNAc via a lactyl ether bridge, we propose (as described above) that in the spore coat a single glycine or a glycine peptide could form an N-glycosidic bond with the C1 atom of one polymer and a peptide bond with the nitrogen atom of a second polymer (Fig. 6, inset). However, it is also possible that Gly peptides are linked via the C1-end of the polymer. These possible linkages have been proposed previously in the N-glycylglucosamine cell wall of Halococcus morrhuae (44), the polyglutamine chain C1-terminally linking two cell wall polymers in the archaeon Natronococcus occultus (45), or the heteropolysaccharide in the sheath of L. cholodnii (40). We cannot, however, rule out that Gly is incorporated directly in the polymer and that adjacent strands are held together by hydrogen bonds.

Given that the nfs mutant did not lack any of the identified spore coat components, we also rationalized that the misassembled spore coat observed in this mutant might be due to perturbed glycan structure and that comparative analysis between the wild type and nfs mutant would be an important tool to examine how the spore coat is structured and assembled. The most interesting observation from linkage analysis of the nfs spore coat material is the dramatic 39% reduction of terminal GalNAc residues and the concurrent 18% increase in 4- and 3-linked GalNAc residues (supplemental Table S2). The remaining 3% loss of t-GalNAc appears to correlate with a small amount of 3,4- and 4,6-linked GalNAc residues that were not observed in the wild type material. The reduction in terminal residues observed in the nfs mutant, together with extremely few tri-linked residues, strongly suggests that the chain length of the glycans in the spore coat is dramatically increased in the nfs mutant. Interestingly, the nfs mutation also affected the Glc linkages with 14 and 4% reduction in t-Glc and 1–6-linked Glc residues, respectively, corresponding to a 19% increase in 1–4-linkages. The percent of Glc residues rearranged in the nfs mutant (19%) is similar to the proportion of Glc (18%) that we calculated as belonging to the spore coat itself (supplemental Table S2). We took advantage of this observation to calculate the fraction of Glc linkages that differed between the wild type and nfs mutant coats, and we then used these data to estimate the average chain length of the spore coat glycan. Given a terminal to internal ratio of altered Glc residues was 1:1.6, and the equivalent GalNAc ratio of 17:24.3, the average chain length of the glycans in the wild type would be 2.4 (supplemental Table S2). Assuming an equivalent proportion of Glc is incorporated in the nfs mutant spore coat, the terminal to internal ratios for Glc and GalNAc would be 1:4 and 18:664, respectively. These data suggest the average chain length in the nfs mutant is 36, 15 times longer than in the wild type. These data suggest a short chain length is necessary for appropriate packing of the chains. Although we observed qualitatively similar amounts of Gly in the wild type and nfs mutant, it is not known whether the Gly is correctly incorporated or linked, which may also contribute to the loss of the rigid sacculus.

Model for Synthesis and Assembly of the Spore Coat

Our analysis of the exo locus and Nfs proteins allows us to propose a model for how the spore coat may be synthesized and assembled (Fig. 6). Bioinformatic, biochemical, and genetic analyses strongly suggest that spore coat polysaccharides containing 1–3- and 1–4-linked GalNAc, 1–4-linked Glc (GalNAc/Glc ∼17:1), and Gly are secreted to the sporulating cell surface by the Exo proteins that function as a Wzy-dependent polysaccharide export pathway (11, 35). Specifically, we propose that ExoE, an initiating sugar transferase homolog, likely links UDP-GalNAc (or UDP-Glc) to a polyisoprenoid lipid undecaprenol diphosphate lipid carrier (Fig. 6, step 1). ExoG–I, which are predicted to be cytoplasmic proteins homologous to proteins that generate or modify nucleotide-activated sugars in pathways leading to polysaccharide synthesis (46), are likely necessary for generating precursors for ExoE and/or for modifying the undecaprenol di-phosphate-linked sugar repeat units. The complete absence of the spore coat in exoE, exoG, exoI, and exoH mutants is consistent with a defect in precursor synthesis.

The lipid-linked sugar repeat unit is predicted to be transferred to the outer leaflet of the inner membrane by a flippase (Wzx) homolog (Fig. 6, step 2) (35). Two flippase homologs can be identified in the M. xanthus genome, MXAN_1035 and MXAN_7416, which are located in the vicinity of polysaccharide synthesis protein homologs previously implicated in EPS production (32, 47). Based on the observation that deletion of MXAN_1035 had only a minor effect on sporulation, the most likely candidate is MXAN_7416. However, we were unable to delete this gene, and attempts to demonstrate interactions between the MXAN_7416 and ExoC or the putative polymerase (MXAN_3026) proteins were not yet successful (data not shown). In the periplasm, the repeat units are linked to higher molecular weight polysaccharides by a polymerase (Wzy) homolog (48), which is most likely encoded by MXAN_3026 (5) (Fig. 6, step 3).

The polymerized repeat units are then transported to the surface of the sporulating cell by a terminal transport complex consisting of at least ExoC, ExoD, and ExoA (Fig. 6). ExoA (a homolog of Wza) likely forms homomultimers in the outer membrane forming a channel through which polysaccharides are extruded (11). ExoC and -D form a split version of the copolymerase, Wzc, which contains an N-terminal co-polymerase domain localized in the cytoplasmic membrane (ExoC) fused to a cytoplasmic tyrosine kinase domain (ExoD). It has been shown that the tyrosine autophosphorylation and dephosphorylation (mediated by a dedicated phosphatase, Wzb) cycles can regulate the amount of surface polysaccharide (49) and/or the chain length of the surface polysaccharides (50) perhaps by direct contact of the N-terminal Wzc domain with the Wza oligomer. ExoA, ExoC, and ExoD are all essential for formation of resistant spores and for spore coat production (this study and Refs. 36, 51, 52), and it has been demonstrated that ExoD autophosphorylates and transfers a phosphoryl group to ExoC in vitro (Fig. 6, step 4) (52). The function of the two remaining Exo proteins (B and F) is less clear. Our studies demonstrated that ExoB, a predicted outer membrane protein, is essential for sporulation and spore coat production, but it is not clear what specific role this protein plays in polysaccharide synthesis and secretion. Finally, our results suggest that ExoF, which is predicted to reside in the cytoplasm, is partially dispensable for spore coat production because the mutant accumulated spore coat material and displayed only a minor sporulation defect. ExoF is homologous to YvcK-like proteins. The exact function of YvcK is not known, but in B. subtilis YvcK it is important for gluconeogenic growth (53), and ExoF might play a subtle role in metabolic rearrangements necessary for spore coat precursor generation by gluconeogenesis in M. xanthus (9).

Once secreted to the cell surface, the Nfs machinery is necessary for assembly of the glycans into a rigid compact cell wall-like layer capable of replacing the function of the degraded peptidoglycan (5, 9). Our data suggest this process involves significantly decreasing the average chain length of the polysaccharides from an estimated 36 residues to 2.4. The eight Nfs proteins (A–H) form a functional complex because, with the possible exception of nfsC, which was not examined, all other nfs genes are necessary for mature spore formation, and the protein stability of most of the Nfs proteins is dependent upon the presence of the others (5). Using heterologous Nfs protein production, we showed here that the Nfs machinery spans the cell envelope with both outer membrane (NfsA–C) and inner membrane (NfsD, -E, and -G)-associated proteins (Fig. 6). Specifically, we predict that NfsA (as well as NfsH, which was not analyzed here), are integral porin-like proteins because they both contain predicted β-barrel structures (5). NfsC and NfsB are likely OM-associated proteins, and reiterative BLAST analysis of NfsB further suggests cell surface localization. NfsD contains a convincing transmembrane segment near the N terminus with the majority of the protein exposed to the periplasm. NfsG likely contains an internal transmembrane segment (amino acids ∼376–390) (54) with a cytoplasmically exposed N-terminal region and a periplasmically exposed C-terminal region. NfsE is a predicted lipoprotein, and in our heterologous system it was located in the CM. This finding should be interpreted with caution because NfsE does not contain the E. coli CM localization signal (Asp at position +2) or the recently suggested M. xanthus CM localization signal (Lys at +2) (55). However, the NfsE homolog, GltE, has been previously shown to fractionate with the CM (12), although it was later depicted in the OM (13). The localization of NfsF is not clear because it cannot be detected with our antisera; however, the protein is predicted to be located in the periplasm.

What specifically does the Nfs complex do? Our analyses suggested that the Nfs complex is not only necessary for appropriate chain length of the secreted glycans but also for the appropriate total quantity because the per cell spore coat material isolated from nfs mutants was more abundant (this study and Ref. 5). It was recently demonstrated that at least NfsG rotates around the pre-spore periphery in a process likely mediated by NfsG-dependent coupling to the AglQRS complex (members of the Exb/Tol/Mot family) thought to harness protonmotive force (13). Because analysis of these proteins with respect to sequence homology reveals little as to their molecular function, how they exert the observed effects on spore coat poly/oligosaccharide chain length remains speculatory. One possibility is that the Nfs complex is necessary for cleavage of the surface polysaccharides (Fig. 6, step 5a) to subsequently mediate cross-links between glycans. Perhaps the rotating complex is necessary to provide directionality and order to this process. Although protonmotive force is clearly required for this process, the movement may be a consequence of its enzymatic processivity as peptidoglycan synthesis drives the movements of MreB-associated peptidoglycan synthase complexes (56, 57).

Given that control of polysaccharide chain length and surface abundance has previously been attributed to tyrosine phosphorylation cycles in Wzc homologs (49, 50), an alternative possibility is that the Nfs complex could affect the chain length of surface poly/oligosaccharides by modulating the activity of ExoC/D (Fig. 6, step 5b). Interestingly, a phosphopeptide binding Forkhead associated (FHA) domain (58) is predicted in the N-terminal domain of NfsG, which could provide a mechanism for direct interaction between NfsG and phosphorylated ExoC/D (and/or a putative Wzb (phosphatase) homolog that is thought to be involved in phosphotyrosine regulation of Wzc proteins (11)). It may be that shorter fragments are necessary to generate a structurally rigid matrix because they facilitate appropriate packing on the prespore surface. Perhaps the rotating Nfs complex functions as a timed regulator to generate an appropriate mix of short and long fragments by “resetting” the individual Exo complexes as it passes. Ongoing efforts to solve the three-dimensional structure of this fascinating biological structure will surely provide deeper insights as to the mechanism of action of the Nfs machinery as well as that of Exo.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge Dr. Annika Ries, Dr. Oliver Ries, and Dr. Chris van der Does for invaluable discussions, Dr. Kathleen Postle for sharing detailed density gradient fractionation protocols, and past and present members of the Higgs and Hoiczyk labs for helpful discussion and proofreading of the manuscript. We gratefully acknowledge Petra Mann for excellent technical assistance.

This work was supported by Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft Grant HI1593/2-1 (to P. H.), Wayne State University (to P. H.), and a fellowship from the International Max Planck Research School (to C. H.). This work was also supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grant GM85024 (to E. H.).

This article contains supplemental Tables 1 and 2.

- EPS

- exopolysaccharide

- O-Ag

- O-antigen

- CM

- cytoplasmic membrane

- OM

- outer membrane

- IPTG

- isopropyl β-d-1-thiogalactopyranoside

- t-

- terminal.

REFERENCES

- 1. Shimkets L., Brun Y. V. (2000) in Prokaryotic Development (Shimkets L., Brun Y. V., eds) pp. 1–7, American Society for Microbiology, Washington, D. C. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Higgins D., Dworkin J. (2012) Recent progress in Bacillus subtilis sporulation. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 36, 131–148 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Kottel R. H., Bacon K., Clutter D., White D. (1975) Coats from Myxococcus xanthus: characterization and synthesis during myxospore differentiation. J. Bacteriol. 124, 550–557 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. McKenney P. T., Driks A., Eichenberger P. (2013) The Bacillus subtilis endospore: assembly and functions of the multilayered coat. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 11, 33–44 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Müller F. D., Schink C. W., Hoiczyk E., Cserti E., Higgs P. I. (2012) Spore formation in Myxococcus xanthus is tied to cytoskeleton functions and polysaccharide spore coat deposition. Mol. Microbiol. 83, 486–505 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Flärdh K., Buttner M. J. (2009) Streptomyces morphogenetics: dissecting differentiation in a filamentous bacterium. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 7, 36–49 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Faille C., Ronse A., Dewailly E., Slomianny C., Maes E., Krzewinski F., Guerardel Y. (2014) Presence and function of a thick mucous layer rich in polysaccharides around Bacillus subtilis spores. Biofouling 30, 845–858 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Bui N. K., Gray J., Schwarz H., Schumann P., Blanot D., Vollmer W. (2009) The peptidoglycan sacculus of Myxococcus xanthus has unusual structural features and is degraded during glycerol-induced myxospore development. J. Bacteriol. 191, 494–505 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Müller F. D., Treuner-Lange A., Heider J., Huntley S. M., Higgs P. I. (2010) Global transcriptome analysis of spore formation in Myxococcus xanthus reveals a locus necessary for cell differentiation. BMC Genomics 11, 264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Nelson D. E., Young K. D. (2001) Contributions of PBP 5 and DD-carboxypeptidase penicillin binding proteins to maintenance of cell shape in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 183, 3055–3064 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Cuthbertson L., Mainprize I. L., Naismith J. H., Whitfield C. (2009) Pivotal roles of the outer membrane polysaccharide export and polysaccharide copolymerase protein families in export of extracellular polysaccharides in Gram-negative bacteria. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 73, 155–177 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Luciano J., Agrebi R., Le Gall A. V., Wartel M., Fiegna F., Ducret A., Brochier-Armanet C., Mignot T. (2011) Emergence and modular evolution of a novel motility machinery in bacteria. PLoS Genet. 7, e1002268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Wartel M., Ducret A., Thutupalli S., Czerwinski F., Le Gall A. V., Mauriello E. M., Bergam P., Brun Y. V., Shaevitz J., Mignot T. (2013) A versatile class of cell surface directional motors gives rise to gliding motility and sporulation in Myxococcus xanthus. PLoS Biol. 11, e1001728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Campos J. M., Zusman D. R. (1975) Regulation of development in Myxococcus xanthus: effect of 3′:5′-cyclic AMP, ADP, and nutrition. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 72, 518–522 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Lee B., Schramm A., Jagadeesan S., Higgs P. I. (2010) Two-component systems and regulation of developmental progression in Myxococcus xanthus. Methods Enzymol. 471, 253–278 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Maniatis T., Fritsch E. F., Sambrook J. (1982) Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual, Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY [Google Scholar]

- 17. Ueki T., Inouye S., Inouye M. (1996) Positive-negative KG cassettes for construction of multi-gene deletions using a single drug marker. Gene 183, 153–157 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Guo D., Bowden M. G., Pershad R., Kaplan H. B. (1996) The Myxococcus xanthus rfbABC operon encodes an ATP-binding cassette transporter homolog required for O-antigen biosynthesis and multicellular development. J. Bacteriol. 178, 1631–1639 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Dworkin M., Gibson S. M. (1964) A system for studying microbial morphogenesis: rapid formation of microcysts in Myxococcus xanthus. Science 146, 243–244 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Chaplin M. C. (1986) in Carbohydrate Analysis–A Practical Approach (Chaplin M. C., Kennedy J. F., eds) pp. 1–36, IRL Press, Oxford [Google Scholar]

- 21. York W., Darvill A. G., McNeil M., Stevenson T. T., Albersheim P. (1986) Isolation and characterization of plant cell walls and cell wall components. Methods Enzymol. 118, 3–40 [Google Scholar]

- 22. Merkle R. K., Poppe I. (1994) Carbohydrate composition analysis of glycoconjugates by gas-liquid chromatography/mass spectrometry. Methods Enzymol. 230, 1–15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Ciucanu I., Kerek F. (1984) A simple and rapid method for the demethylation of carbohydrates. Carbohydr. Res. 131, 209–217 [Google Scholar]

- 24. Osborn M. J., Gander J. E., Parisi E. (1972) Mechanism of assembly of the outer membrane of Salmonella typhimurium. Site of synthesis of lipopolysaccharide. J. Biol. Chem. 247, 3973–3986 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Letai T. E., Postle K. (1997) Tomb protein appears to transduce energy by shuttling between the cytoplasmic membrane and the outer membrane in Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol. 24, 271–283 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Laemmli U. K. (1970) Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature 227, 680–685 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]