Abstract

Objective:

To systematically review the psychometric properties of instruments used to screen for major depressive disorder or assess depression symptom severity among African youth.

Methods:

Systematic search terms were applied to seven bibliographic databases: African Journals Online, the African Journal Archive, CINAHL, Embase, MEDLINE, PsycINFO, and the WHO African Index Medicus. Studies examining the reliability and/or validity of depression assessment tools were selected for inclusion if they were based on data collected from youth (any author definition) in an African member state of the United Nations. We extracted data on study population characteristics, sampling strategy, sample size, the instrument assessed, and the type of reliability and/or validity evidence provided.

Results:

Of 1,027 records, we included 23 studies of 10,499 youth in 10 African countries. Most studies reported excellent scale reliability, but there was much less evidence of equivalence or criterion-related validity. No measures were validated in more than two countries.

Conclusions:

There is a paucity of evidence on the reliability or validity of depression assessment among African youth. The field is constrained by a lack of established criterion standards, but studies incorporating mixed methods offer promising strategies for guiding the process of cross-cultural development and validation.

Keywords: depressive disorder, reproducibility of results, adolescent, child, Africa

Introduction

Mental disorders are a leading cause of disease burden worldwide, including in low- and middle-income countries (Ferrari et al. 2013; Whiteford et al. 2013). Systematic data on the burden of mental disorders among youth, especially in African countries, are scarce. The few studies conducted among African youth suggest the burden of mental disorders is substantial. For example, in their recently published systematic review of community-based studies conducted among children and adolescents in six sub-Saharan African countries, Cortina et al. (2012) found that one in seven children were assessed as having significant psychological difficulties while 1 in 10 were diagnosed with a psychiatric disorder.

The paucity of data on mental health problems among African youth is likely due to a number of factors, including the low priority assigned to mental health in these countries (Tomlinson and Lund 2012), limited human resources for mental health (Saxena et al. 2007), and the stigma attached to people with mental disorders (Barke, Nyarko, and Klecha 2011; Crabb et al. 2012; Gureje et al. 2005; Kapungwe et al. 2010). The lack of culturally relevant mental health assessment tools compounds difficulties in screening (Kagee et al. 2013) and further exacerbates these disparities. As highlighted by Cortina et al. (2012), most existing assessment tools for children and adolescents are based on data collected in Western populations. Yet the extent to which these instruments can reliably and/or validly assess depression among African youth is unclear.

Another important reason why problems with the reliability and/or validity of depression assessment might be anticipated in African settings is that, while many symptoms of depression may be universal, mental illness constructs are likely to be burdened with ethnocentric conceptualization. Ethnographic and epidemiologic data suggest that the presentation of these disorders varies substantially across cultures, potentially rendering existing measures incompatible with local concepts of distress (Aidoo and Harpham 2001; Betancourt et al. 2009b; Okello 2006; Okello and Ekblad 2006; Ventevogel et al. 2013). The experience of sadness or depressed mood may not even be a core presenting feature of affective disturbance in some cultural contexts (Bebbington 1993; Tomlinson et al. 2007). Thus, existing depression instruments may have utility if modified appropriately for the local context. However, it is possible that simple literal translation of existing depression instruments may not be sufficient to ensure reliable and/or valid assessments.

As emphasized in the recent World Health Organization (2013) Mental Health Action Plan, strengthening mental health policy, planning, and evaluation in low- and middle-income countries requires quality data, generated through research and evidence-based practice. Previously published reviews have summarized the reliability and validity of instruments for assessing depression among adults (Sweetland, Belkin, and Verdeli 2014) and among pregnant or postpartum women (Tsai et al. 2013). This paper seeks to address a major gap in the literature by systematically reviewing the psychometric properties of instruments used to screen for major depressive disorder or assess depression symptom severity among African youth.

Methods

Study selection

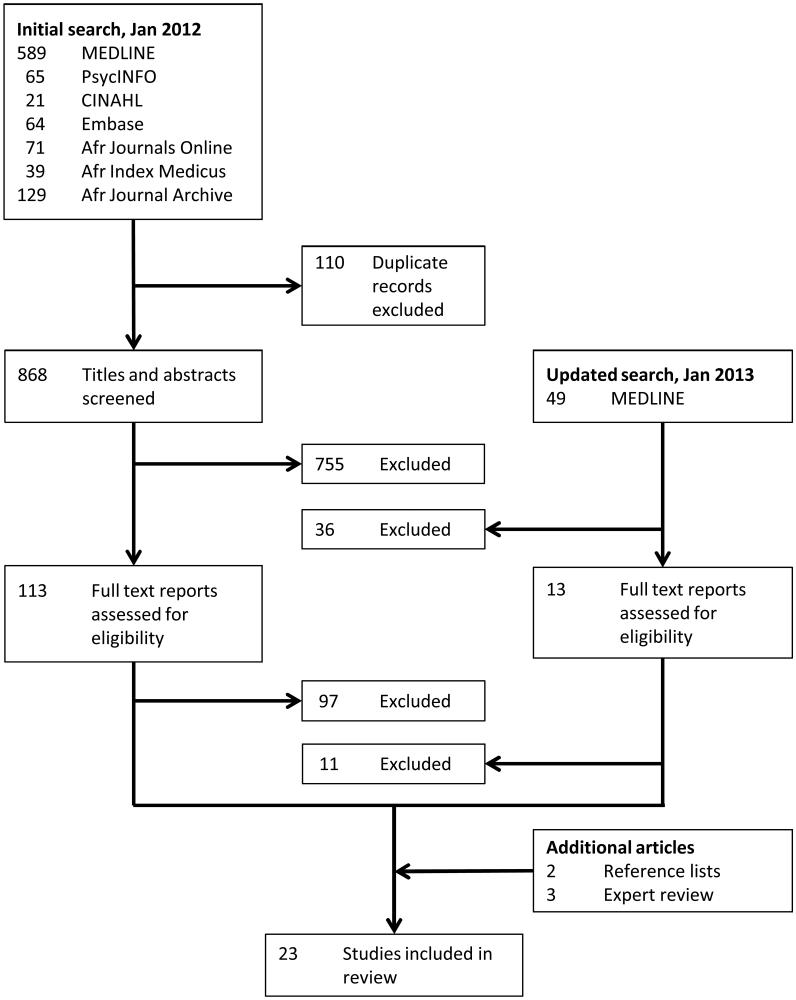

The systematic evidence search, which was conducted January-May 2012, employed seven bibliographic databases: African Journals Online, the African Journal Archive, the Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature, Embase, the Medical Literature Analysis and Retrieval System Online (MEDLINE), PsycINFO, and the World Health Organization African Index Medicus. The specific search terms applied to these databases are listed in Appendix 1. In January 2013 we updated the MEDLINE search to identify articles published in the intervening 6-12 months. All citations from each database’s inception to the search date were imported into the EndNote reference management software program (Version X5, Thomson Reuters, New York, NY), and the “Find Duplicates” algorithm was used to identify duplicate references. One study author (A.C.T.) screened the titles, abstracts, and full texts of the articles to identify potentially relevant articles for inclusion in the study. In addition, we searched the reference lists of articles selected for inclusion and queried colleagues in departments of psychiatry and psychology at other African academic institutions, in order to identify additional potentially relevant articles for inclusion.

Appendix 1.

Search terms applied to bibliographic databases †

| Database | Search terms |

|---|---|

| The African Journal Archive |

depression or distress |

| African Journals online |

(depressive OR depression OR affective OR mood OR postpartum OR postnatal) AND (diagnosis OR sensitivity OR specificity OR validation OR screening OR psychometric OR “factor analysis” OR “factor structurefactor analysis” or reliability OR validity OR consistency) |

| Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature |

MH “affective disorders” OR MH “Beck Depression Inventory, revised edition” OR MH “Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale” OR MH “Edinburg Postnatal Depression Scale” OR MH “Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression” OR MH “Self-Rating Depression Scale” OR “MH Bech-Rafaelson Melanchoha Scale” OR MH AB Depression OR AB Depressive OR AB “psychological distress” OR AB idiom) AND (MH Africa OR MH refugees or MH AB Africa) AND (MH diagnosis OR MH psychometrics OR MH “factor analysis” OR MH “rehability and validity” or MH “Rasch analysis” OR AB “constmct validity” OR AB “convergent validity” OR AB “divergent validity” OR AB “discriminant validity” OR AB “content validity” OR AB “face validity” OR AB “criterion validity” OR AB “concurrent validity” OR AB “predictive validity” OR AB validity OR AB reliability OR AB consistency) |

| Embase | (depressionxl OR “distress syndrome” :cl OR “Bech-Rafaelsen Melancholia scale” :cl OR “Beck Depression lnventory”:cl OR Beck Hopelessness Scale”:cl OR “Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale”:cl OR “Edinburg Postnatal Depression Scale”:cl OR “General Health Questionnaire”:cl OR “Hamilton Scale”:cl OR “Montgomery Asberg Depression Rating Scale”:cl OR Psychiatric Symptom lndex”:cl OR “Self-Rating Depression Scale”:cl OR “Symptom Checklist 90”:cl OR depressive:ab OR depression:ab OR “psychological disttess”:ab OR idiom:ab) AND (Africa:cl OR refugee:cl OR Africa:ab) AND (“psychiatric diagnosis”cl OR diagnosis:cl OR “sensitivity and specificity”:cl OR validity:cl OR reliability:cl OR “mass screening”:cl OR “factorial analysis”:cl OR “Rasch analysis”:cl OR psychometry:cl OR screening:ab OR psychometric:ab OR “factor analysis”:ab OR “factor structure”:ab OR “Rasch analysis”:ab OR “latent ttait analysis”:ab OR “construct validity”:ab OR “convergent validity”:ab OR “divergent validity”:ab OR “discriminant validity”:ab OR “content validity”:ab OR “face validity”:ab OR “criterion validity”:ab OR “concurrent validity”:ab OR “predictive validity”:ab OR validity:ab OR reliability:ab OR “consistency”:ab) |

| Medical Literature Analysis and Retrieval System Online |

(“depressive disorder”[MeSH Terms] OR “depression”[MeSH Terms] OR “affective symptoms”[MeSH Terms] OR “mood disorders” [MeSH Terms] OR “depression postpartum” [MeSH Terms] OR “stress, psychological” [MeSH Terms] OR “depressive” [TIAB] OR “depression” [TIAB] OR “psychological distress” [TIAB] OR “idiom” [TIAB] AND (“Africa” [MeSH Terms] OR “refugees” [MeSH Terms] OR “Africa” [TIAB] AND (“diagnosis”[MeSH Terms] OR “sensitivity and specificity” [MeSH Terms] OR “reproducibility of results” [MeSH Terms] OR “validation studies as topic”[MeSH Terms] OR “validation studies”[Pubhcation type] OR “screening” [TIAB] OR “psychometric”[TIAB] OR “factor analysis”[TIAB] OR factor structure” [TIAB] OR “Rasch analysis” [TIAB] OR “latent trait analysis” [TIAB] OR “construct validity” [TIAB] OR “convergent validity” [TIAB] OR “divergent validity” [TIAB] OR “discriminant validity” [TIAB] OR “content validity” [TIAB] OR “face validity” [TIAB] OR “criterion validility” [TIAB] OR “concurrent validity” [TIAB] OR “predictive validity” [TIAB] OR “validity” [TIAB] OR “reliability”[TIAB] OR “consistency”[TIAB]) |

| PsycINFO | (DE “affective disorders” OR “DE “stress” OR AB “depressive” OR AB “depression” OR AB “psychological distress” OR AB “idiom) AND (DE “African cultural groups” OR DE “refugees” OR AB “Africa”) AND (DE “test validity” OR DE “statistical validity” OR DE “factor analysis” OR DE “screening” OR DE “psychometrics” OR AB “psychometrics” OR AB “factor analysis” OR AB “factor structure” OR AB “Rasch analysis” OR AB “latent trait analysis” OR AB “construct validity” OR AB “construct validity” OR AB “convergent validity” OR AB “divergent validity” OR AB “discriminant validity” OR AB “content validity” OR AB “face validity” OR AB “criterion validity” OR AB “concurrent validity” OR AB “predictive validity” OR AB “validity” OR AB “reliability” OR AB “consistency” |

| World Health Organization Index Medicus |

Depression or distress |

All database searches were completed on January 27, 2012, with the exception of searches conducted using the African Journal Archive, African Journals Online, and the World Health Organization African Index Medicus, which were completed May 30, 2012. The Medical Literature Analysis and Retrieval System Online search was updated on January 23, 2013.

In screening articles, we recognized that no standard definition of adolescence exists, especially cross-culturally, and that the conventional definition of “youth” as employed by the United Nations includes persons aged 24 years or younger. We therefore included studies of youth but permitted any author-provided definition to determine eligibility for inclusion. In addition, studies had to meet the following criteria: (a) data were collected from any African member state of the United Nations; (b) a questionnaire (e.g., diagnostic interview schedule, screening instrument, or symptom rating scale) was used to screen study participants for major depressive disorder or to measure depression symptom severity; and (c) the reliability and/or validity of the questionnaire was assessed. There were no language or study participant age restrictions.

We accepted a wide range of reliability and validity evidence for inclusion in this review, including: evaluations of linguistic, conceptual, or metric equivalence (Brislin, 1993); analyses of the reproducibility of scale measurements, either between raters (inter-rater reliability) or from one measurement to the next (test-retest reliability); assessments of measurement structure, either of the extent to which scale items measure the same latent construct (internal consistency) or of the scale’s overall factor structure; and/or confirmation of hypothesized relationships between the measurement scale and other variables of interest (American Educational Research Association 1999), such as a reference criterion standard (e.g., diagnosis of major depressive disorder consistent with the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders) or variables conceptually thought to be related to depression (convergent validity). Because virtually any study estimating the association between depression and another variable of interest could potentially be considered as presenting evidence of construct validity, and because Cronbach’s alpha coefficients are near-universally reported in studies not focused on psychometric assessment (such as observational and experimental studies), we excluded studies in which these were the sole form of evidence presented.

Two study authors (M.M., A.C.T.) worked independently to abstract data from the included reports, and then compared their findings, with all disagreements resolved through consensus. For each report, data were extracted on the characteristics of the study population, including sampling strategy, sample size, inclusion criteria, instrument assessed, and type of reliability and/or validity evidence provided. Due to heterogeneity in the types of measures and study designs employed, we did not attempt to summarize the data using meta-analysis.

Ethics statement

This study was reviewed by the Partners Human Research Committee and deemed exempt from full review because it was based on anonymous, public-use data with no identifiable information on participants.

Results

Study characteristics

Our database searches yielded 1,027 records, of which 110 were duplicates. After reviewing the remaining 917 records, we excluded 791 records on the basis of title and abstract screening. We then retrieved 126 reports, including peer-reviewed journal articles and doctoral dissertations, for full text review. Of these, 108 reports were excluded because they did not provide evidence of the reliability or validity of an instrument used to assess mental disorders among African youth. Five journal articles were identified from reference lists and by querying local experts. In all, 23 studies were included in this review. No articles written in languages other than English met inclusion criteria.

Summary statistics for the sample are provided in Table 1. A total of 10,499 youth spanning ages 3-26 years, and 1,089 adult key informants (e.g., parents, caregivers, or health care workers), participated across all studies. Most studies (17 [74%]) limited inclusion to persons 24 years of age or younger. A total of 12 studies (52%) limited inclusion to children and adolescents 18 years of age or younger. Three studies included university students up to 53 years in age but did not report stratified analyses for youth, while other studies included persons older than 18 years but described them as “adolescents.” Sample sizes (which in a few cases included both youth as well as adult key informants) ranged from 56 to 1114, with a median of 464. Most studies employed non-probability-based sampling designs, such as convenience and/or purposive samples. Studies based on probability samples were largely conducted within school settings. Slightly more than one-half of the studies were based on data obtained from school-going youth.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the sample (N=23)

| Study characteristic | Number (percentage) or median (range) |

|---|---|

| Country of origin | |

| South Africa | 7 (30) |

| Egypt | 3 (13) |

| Uganda | 3 (13) |

| Other † | 10 (43) |

| Year of publication | |

| Prior to 2010 | 9 (39) |

| 2010 | 5 (22) |

| 2011 | 6 (26) |

| 2012 | 3 (13) |

| Sample size, median (range) | 450 (10-1,216) ‡ |

| Type of instrument assessed | |

| Screening instrument or symptom rating scale | 20 (87) |

| Diagnostic interview schedule | 3 (13) |

| Study population ¶ | |

| Community | 22 (96) |

| Outpatient | 3 (13) |

| Inpatient | 1 (4) |

| Type of evidence provided ¶ | |

| Reliability | 17 (74) |

| Construct validity | 9 (39) |

| Equivalence or content validity | 7 (30) |

| Criterion-related validity | 6 (26) |

| Internal structure | 6 26) |

Includes Botswana, Democratic Republic of Congo, Ethiopia (2 studies), Kenya, Nigeria (2 studies), Rwanda (2 studies), and Tanzania

Interquartile range, 178-804

Percentages may not add up to 100, as categories are not mutually exclusive

Altogether, 15 different measurement tools were assessed for reliability and/or validity. Screening instruments such as the Center for Epidemiological Studies-Depression scale (CES-D) and Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) were the most frequently studied measures. These were typically compared to criterion standard diagnoses derived from diagnostic interview schedules. Reliability or validity evidence was obtained in two countries for several instruments: the BDI (Nigeria, South Africa), the Children’s Depression Inventory (Egypt, Tanzania), the CES-D (Rwanda, South Africa), and the Hopkins Symptom Checklist (Democratic Republic of the Congo, Uganda). However, no instrument was assessed in more than two different contexts. Only three studies explored aspects of equivalence or the validity of the diagnostic interview schedules themselves (Flisher, Sorsdahl, and Lund 2012; Kebede et al. 2000; Sharp et al. 2011).

Evidence for reliability and validity

Further details of the included studies are provided in Table 2. Most studies (16 [70%]) reported the internal consistency of the measure used, with the reported Cronbach’s alpha coefficients ranging from 0.67-0.90 (median, 0.86). Six studies (27%) reported test-retest reliability, with values ranging from 0.32-0.89 (Adewuya, Ola, and Afolabi 2006a; Adewuya, Ola, and Aloba 2007; Betancourt et al. 2012; Betancourt et al. 2009a; Flisher et al. 2012; Rothon et al. 2011). Only two studies reported inter-rater reliability (Betancourt et al. 2009a; Kebede et al. 2000).

Table 2.

Studies validating instruments for screening and measurement of depression among African youth

| Reference | Study design | Instrument(s) assessed | Evidence of reliability or validity |

|---|---|---|---|

| Abubakar and Fischer (2012) | A convenience sample of 427 working adults (25-43 years), 108 university students (19-23 years) and 696 secondary school students (14-19 years) in urban Kenya self- administered the English version of the General Health Questionnaire (GHQ-12). |

GHQ-12 | Confirmatory factor analysis was used to test five different models of the GHQ-12. The best-fitting model was a three-dimensional model of anxiety/depression, loss of confidence, and social dysfunction. The multi-dimensionality appeared to be substantively related to negative wording. |

| Adewuya et al. (2006a) | A probability sample of 512 students (15-40 years) in Nigeria self-administered English versions of the 9-item Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ) and 21-item Beck Depression Inventory (BDI). Research assistants administered the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI) in English to establish the reference criterion of major and minor depressive disorder. |

PHQ-9 BDI-21 |

The internal consistency of the PHQ-9 was 0.85. The PHQ-9 had a statistically significant correlation with the BDI (Spearman’s rho = 0.67, P<0.001). PHQ-9 scores obtained 4 weeks apart had a statistically significant correlation with each other (Spearman’s rho = 0.89, P<0.001). PHQ-9 ≥5 had 0.90 sensitivity and 0.99 specificity for detecting combined major and minor depressive disorder (AUC = 0.991). PHQ-9 ≥10 had 0.85 sensitivity and 0.99 specificity for detecting major depression (AUC = 0.985). |

| Adewuya et al. (2007) | A stratified random sample of 1,095 Nigerian adolescents (13- 18 years) in secondary school completed the 21-item BDI. The entire high-morbidity group (≥ 10) and 10% of those in the low-morbidity group (<10) were administered the Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-aged Children-Epidemiological Version 5 (K-SADS-E) by psychiatrists blinded to the BDI scores to establish the reference criterion diagnosis of major depressive disorder (MDD). |

BDI-21 | The internal consistency of the BDI was 0.82. BDI scores obtained 2 weeks apart had a statistically significant correlation (Spearman’s rho = 0.72, P<0.001). BDI ≥18 had 0.91 sensitivity and 0.97 specificity for detecting major depressive disorder (AUC = 0.985). In a separately reported analysis (Adewuya and Ologun, 2006b), significant correlates of depressive symptoms were: parental depression, interpersonal problems, self-esteem, and drinking. |

| Ambaw (2011) | A randomly selected sample of 804 orphans (11-18 years) receiving care at 16 selected orphan support organizations in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia were administered the Amharic version of the 14-item Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) by trained interviewers. |

HADS | Factor analysis revealed two factors (anxiety, depression) that explained 46% of the total variance. In the overall sample, consistency of the HADS depression and anxiety sub-scales were 0.76 and 0.81 respectively. In the subsample of orphans aged 11- 15 years, the internal consistency of the depression and anxiety sub-scales were 0.77 and 0.80 respectively. |

| Bekhet and Zauszniewski (2010) | A convenience sample of 170 adolescents (17-20 years) studying at a nursing school in Egypt self-administered the 8- item Arabic version of the Depression Cognition Scale (DCS). |

DCS | The internal consistency of the DCS was 0.86. Factor analysis confirmed the presence of a single factor. The DCS had a statistically significant positive correlation with a scale measuring alienation (r=0.51, P<0.01). |

| Betancourt et al. (2009a) | A convenience sample of 178 adolescents (14-17 years) and their caregivers in two IDP camps in Gulu were administered the 60-item Acholi Psychosocial Assessment Instrument (APAI) to identify local mental health syndromes, three of which (two tam, par, and kumu) overlap with western concepts of mood disorders. Participants were randomly selected for a second interview, either 1-3 days later to determine test-re-test reliability (N = 30), or by other interviewer to determine inter- rater reliability (N = 19). Caseness was by determined by agreement between both the adolescent and the caregiver. |

APAI | For the 16-item two tam subscale, internal consistency was 0.87, split halves reliability (Spearman-Brown) was 0.88, test-retest reliability was 0.79, and inter-rater reliability was 0.86. For the 13- item kumu subscale, internal consistency was 0.87, split halves reliability was 0.88, test-retest reliability was 0.83, and inter-rater reliability was 0.92. For the 17-item par subscale, internal consistency was 0.84, split halves reliability was 0.83, test-retest reliability was 0.79, and inter-rater reliability was 0.78. Mean subscale scores were greater among adolescents identified as having those syndromes (P<0.001 for each). In a subsequent study of 667 youth, the APAI was refined using item response theory and reconfigured into a shorter, 41-item African Youth Psychosocial Assessment designed for use in assessing mental health among African youth more broadly (Betancourt et al., in press). |

| Betancourt et al. (2009b) | This was a qualitative study of 56 children (10-17 years) and 47 adult key informants living in two IDP camps in Gulu, Uganda. |

Not applicable | Key informants identified three local syndromes that overlap with mood and depressive disorders: two tam (having “lots of thoughts”), kumu (persistent grief and par (having many worries). |

| Betancourt et al. (2011) | A purposive sample of 31 adults and 43 children (10-17 years) in southwestern Rwanda was asked to free-list problems faced by HIV-affected children. A snowball sample of 90 adults (including 10 clinicians) and 38 children participated in in- depth key informant interviews to explore specific local syndromes. |

Not applicable | Participants identified local syndromes that overlap with DSM-IV criteria for dysthymia and major depressive disorder, including guhangayika (constant anxiety/stress), agahinda kenshi (persistent sorrow or sadness), and kwiheba (severe hopelessness). Umishiha (persistent irritability or anger) emerged as the syndrome most heavily influenced by repeated experience of loss and stigma due to HIV/AIDS. |

| Betancourt et al. (2012) | The Center for Epidemiological Studies-Depression scale for Children (CES-DC) was adapted by including parenthetical reminders of the conceptually equivalent Kinyarwanda symptom terms identified in a qualitative study. The modified CES-DC underwent cognitive testing with a convenience sample of 46 children and adolescents. The Pearson correlation coefficient was used to estimate test-retest reliability in a convenience sample of 34 children (10-17 years) who were re- interviewed 1-3 days after initial assessment. The intra-class correlation coefficient was used to estimate inter-rater reliability in a convenience sample of 30 children and adolescents (10-17 years). A purposive sample of 467 children and adolescents (10-17 years) in southeastern Rwanda were administered the modified CES-DC. Psychologists blind to the CES-DC scores administered the MINI for Children and Adolescents (MINIKID) to establish the reference criterion diagnosis for depressive disorder. |

CES-DC | The CES-DC had an internal consistency of 0.86. The Pearson coefficient for test-retest reliability was 0.85. The intra-class correlation within participants was 0.82. CES-DC ≥30 had 0.82 sensitivity and 0.72 specificity for detecting depression (AUC = 0.83). The CES-DC had a statistically significant association with a measure of functional disability (Pearson’s r=0.46; P<0.001). |

| Cherian, Peltzer, and Cherian (1998) | A random sample of 622 grade 11 secondary school students (17-24 years) in Northern Province, South Africa were administered the 20-item Self-Reporting Questionnaire (SRQ) by trainee teachers. |

SRQ | The SRQ had an internal consistency of 0.9. Factor analysis revealed four factors (anxiety/depression, depression, anxiety, and somatic complaints) accounting for 51% of the total variance. |

| El-Missiry et al. (2012) | A probability sample of 602 girls (14-17 years) in secondary schools in Cairo, Egypt self-administered the Arabic version of the Children’s Depression Inventory (CDI). A researcher blind to the CDI scores administered the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Diagnosis Research Version, Non-Patient Edition (SCID-I/NP) to establish the reference criterion, a combined diagnosis of major depression, dysthymia, and adjustment disorder. |

CDI | CDI ≥24 had 0.75 sensitivity and 0.98 specificity for detecting depressive disorders. CDI scores had statistically significant associations with poor academic achievement (P<0.001), termination of romantic relationships (P<0.001), a quarrelsome home environment (P<0.001), and negative life events (P=0.01). |

| Ertl et al. (2010) | A random sample of 1,114 war-affected adolescents and young adults (12-25 years) living in IDP camps in Northern Uganda were administered the 15-item HSCL. A randomly selected subset of 68 participants underwent expert validation interviews, 4-18 days after the initial interview, by blinded psychologists who administered the MINI to establish the reference criterion diagnosis for major depressive disorder. |

HSCL-15 | The HSCL-15 had an internal consistency of 0.89. HSCL-15 ≥2.65 had 0.50 sensitivity and 0.83 specificity for detecting major depressive disorder (AUC = 0.76). The widely used cutoff ≥1.75 had 0.86 sensitivity and 0.44 specificity. HSCL-15 scores had statistically significant associations with the Posttraumatic Diagnostic Scale (P<0.001), a locally-derived measure of functional impairment (P<0.001), and suicide risk (P=0.002). |

| Flisher et al. (2012) | A sample of 105 parent/caregiver and child (12-17 years) pairs from a peri-urban South African clinic and community sample participated in the study. Trained research assistants administered the Xhosa version of the Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children (DISC-IV) and then again two weeks later. |

DISC-IV | Test-retest reliabilities for parent informants were as follows: MDD (κ = 0.662), oppositional defiant disorder (ODD) (κ = 0.662), attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) (κ = 0.559), anxiety (κ = 0.448) and agarophobia (κ = 0.789). Test- retest reliabilities youth informants were: MDD (κ = 0.661), ODD (κ = 0.385), ADHD (κ = 0.227), anxiety (κ = 0.145) and agarophobia (κ = 0.579). The test-retest reliabilities of the combined parent-child algorithm lay between the parent and youth findings but only MDD yielded substantial results (κ = 0.662). |

| Ibrahim, Kelly, and Glazebrook (2012) | A probability sample of 988 Egyptian undergraduate university students (16-26 years) self-administered a modified 46-item Arabic version of the Zagazig Depression Scale. |

Zagazig | The Zagazig Depression Scale had an internal consistency of 0.90 and a split-half reliability of 0.89. Internal consistency of the subscales ranged between 0.64-0.79. Factor analysis revealed an 11-factor solution that explained 62% of the variance: depression, suicidal ideation, guilty feelings, insomnia, agitation/ hypochondriasis, sleep maintenance, cognitive impairment, diminished energy, weight loss, and sexual symptoms. |

| Kebede et al. (2000) | A purposive sample of 255 children and adolescents (6-18 years) was obtained from the inpatient and outpatient wards of a psychiatric hospital, a school for mentally disabled children, and the surrounding community in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. For children aged 6-11 years, the parent or primary caregiver was interviewed. One trained lay interviewer and one clinician participated in each interview; one administered the Revised Diagnostic Interview for Children and Adolescents (DICA-R) in Amharic, while both coded the responses independently. |

DICA-R | The kappa statistic for agreement on the DSM-III diagnosis of major depressive episode was 0.90. |

| Lowenthal et al. (2011) | A convenience sample of 509 HIV-positive children and adolescents (8-16 years) in two outpatient settings in Botswana were administered the Setswana version of the 35-item Pediatric Symptom Checklist-Youth Version (PSC-Y) and the CDI, while one parent/guardian was administered the PSC (i.e., adult version). The reference criterion for the PSC was “parent and clinic staff reports of concern about the child”, while the reference criterion for the PSC-Y was depressive disorder as diagnosed by the CDI. |

PSC CDI |

Internal consistency was 0.87 for the PSC-35 and 0.86 for the PSC-35-Y. PSC-35 ≥20 had 0.62 sensitivity and 0.86 specificity for detecting concern about the child (AUC = 0.85). PSC-35-Y ≥20 had 0.64 sensitivity and 0.88 specificity for detecting depression (AUC = 0.81). |

| Mels et al. (2010) | Focus group interviews with 66 key informants in the Democratic Republic of Congo were used to derive a list of locally observed symptoms. The 37-item HSCL was modified by removing two items that did not emerge in the qualitative interviews (“feeling trapped”, “using sleeping pills), condensing two items into a single item (“drinking alcohol”) and adding four frequently mentioned local idioms (“overburdened by worries”, ”talking to oneself”, “not interested in school”, “not following the rules”). The Swahili or Congolese French versions of the modified 38-item HSCL were administered to 1,046 adolescents (13-21 years) in a school-based survey. |

HSCL-38 | One item (“loss of sexual interes”) was excluded from analysis due to a high proportion of missing values, especially among participants in Catholic schools. The French version of the HSCL- 38 had an internal consistency of 0.90, with coefficients ranging from 0.76-0.89 on the four subscales (internalizing, depression, anxiety, externalizing). The Swahili version of the HSCL-38 had an internal consistency of 0.91, with a subscale coefficients ranging from 0.66-0.91. Exploratory factor analysis revealed two factors broadly categorized an internalizing and externalizing problems. The modified HSCL-38 total score had statistically significant associations with the Impact of Event Scale-Revised and its possible subscale scores, the Adolescent Complex Emergency Exposure Scale, and subjective psychological wellbeing(P<0.01). |

| Pretorius (1991) | A sample of 450 undergraduate psychology students (19-53 years) in South Africa self-administered the CES-D. |

CES-D | The CES-D had an internal consistency of 0.90. Factor analysis revealed a four-factor solution. The internal consistencies of the factor subscales were as follows: depressed affect (0.85), somatic- retarded activity (0.71), positive affect (0.73), and interpersonal relations (0.70). The 57-item Life Experiences Survey had a statistically significant association with the CES-D total score (Pearson’s r=0.21, P<0.05), as well as with three of the factors: depressed affect (r=0.18, P<0.01), somatic-retarded activity (r=0.26, P<0.01) and interpersonal relations (r=0.15, p <0.01). |

| Pretorius (1998) | A sample of 213 undergraduate psychology students (19-53 years) in South Africa self-administered the CES-D. |

CES-D | The CES-D had an internal consistency of 0.90. The CES-D had a statistically significant association with the Life Experiences Survey-Negative (Pearson’s r=0.19, P<0.05). |

| Rothon et al. (2011) | A convenience sample of 237 adolescents (14-15 years) in Cape Town, South Africa self-administered the Afrikaans or isiXhosa versions of the 13-item Short Moods and Feelings Questionnaire (SMFQ) on two occasions one week apart. |

SMFQ | The SMFQ had an internal consistency of 0.85. The correlation between SMFQ scores one week apart was 0.32 (P-value not reported). |

| Sharp et al. (2011) | A focus group interview was held in English with 10 Sesotho- speaking clinicians (five clinical psychologists, five licensed social workers, and one clinical psychology intern) in Bloemfontein, South Africa. Data were grouped into broad thematic areas. |

DISC-IV | Participants identified a number of cultural considerations that could affect the utility of the DISC in the Sesotho context. These included its rigid response structure, “Americanisms,” problems in interpretation due to widespread socioeconomic adversity, language problems, and cultural norms about psychiatric symptoms, the expression of emotion and family structure. |

| Traube et al. (2010) | After a local work group translated the CDI, field workers provided further input to modify three scale items. The CDI was then administered to four groups of children and adolescents in southwestern Tanzania (3-19 years), including orphans living in a local residential facility vs. those who were not. |

CDI | The CDI had an internal consistency of 0.67, and the subscale reliability coefficients were lower: negative mood (0.31), interpersonal problems (0.24), ineffectiveness (0.11), anhedonia (0.58), and negative self-esteem (0.34). Spearman-Brown split half reliability was 0.66. The proportion of orphans with high-risk symptoms was lower among residents of the orphan facility compared to orphans not living in the facility (14.3% vs. 47.1%). |

| Ward et al. (2003) | A convenience sample of 104 students (12-18 years) in Cape Town, South Africa self-administered the 21-item BDI in English, Afrikaans, or Xhosa. Participants completed the questionnaire again 10-14 days after the initial self- administration. |

BDI-21 | Internal consistency of the BDI was 0.86. Test-retest reliability was described as “good” but the estimated kappa coefficients were not reported. |

ADHD = Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder; AUC = area under the receiver-operating characteristics curve; BDI = Beck Depression Inventory; CDI = Child Depression Inventory; CES-DC = Center for Epidemiological Studies-Depression scale for Children; DCS = Depression Cognition Scale; DICA-R = Revised Diagnostic Interview for Children and Adolescents; DISC-IV = Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children; DSM = Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders; GHQ = General Health Questionnaire; HADS = Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale; HSCL = Hopkins Symptom Checklist; IDP = internally displaced persons; K-SADS-E = Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-aged Children-Epidemiological Version 5; MDD = Major Depressive Disorder; MINI = Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview; MINIKID = Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview for Children and Adolescents; ODD = Oppositional Defiant Disorder; PHQ = Patient Health Questionnaire; PSC-Y = Pediatric Symptom Checklist-Youth version; SCID-I/NP = Structured Clinical interview for DSM-IV Axis I Diagnosis Research Version, Non-Patient Edition; SMFQ = Short Moods and Feelings Questionnaire; SRQ = Self-Reporting Questionnaire

Construct validity was typically assessed by estimating the association between depression scores and other variables of conceptual interest. These associations were in the hypothesized direction and included variables such as family problems, functional disability, negative life experiences, and traumatic stress. Six studies (26%) assessed the factor structure of the scale within the study population (Table 3). Of these, nearly all yielded a factor structure consistent with the original scale (most of which were developed in Western countries). Seven studies (30%) investigated different aspects of equivalence, typically through the use of in-depth interviews with local informants to identify and/or understand symptom profiles of local concepts of distress

Table 3.

Factor stmcture of depression instruments as compared to the factor structure determined in the original publications

| Author | Instrument | Factor structure obtained in African setting |

Comparison to original study |

|---|---|---|---|

| Abubakar et al. (2012) | GHQ | Anxiety/depression, loss of confidence, social dysfunction (Kenya) |

Anxiety/depression, loss of confidence, social dysfunction (UK) (Goldberg, 1972) |

| Ambaw (2011) | HADS | Anxiety, depression (Ethiopia) |

Anxiety, depression (UK) (Moorey et al., 1991; Zigmond and Snaith, 1983) |

| Bekhet et al. (2010) | DCS | Depression (Egypt) | Depression (U.S. (Zauszniewski, 1995) |

| Ibrahim et al. (2012) | Zagazig | Depression, suicidal ideation, guilt, anxiety, insomnia, agitation, sleep maintenance, concentration, amotivation, weight loss, sexual symptoms (Egypt) |

17 factors (Egypt) (Fawzi et al., 1982) |

| Mels et al. (2010) | HSCL | Internalizing, externalizing (Democratic Republic of the Congo) |

Internalizing, externalizing (Netherlands) (Bean et al., 2007) |

| Pretorius (1991) | CES-DC | Depressed affect, somatic- retarded activity, positive affect, interpersonal relations (South Africa) |

Depressed affect, somatic-retarded activity, positive affect, interpersonal relations (U.S.) (Radloff, 1977) |

CES-DC = Center for Epidemiological Studies-Depression scale for Children; DCS = Depression Cognition Scale; GHQ = General Health Questionnaire; HADS = Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale; HSCL = Hopkins Symptom Checklist;

Six studies (26%) estimated the criterion-related validity of the mental health instrument. To establish the reference criterion diagnosis, most studies employed a structured diagnostic interview such as the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview, while others used caregiver/clinical reports of concern. Estimated sensitivity tended to be lower than specificity, with sensitivity values ranging from 0.50-0.91 (median, 0.79) and specificity values ranging from 0.72-0.99 (median, 0.92).

Discussion

In this systematic review of the psychometric properties of instruments used to screen for major depressive disorder or assess depression symptom severity among African youth, we identified only 23 unique studies of instrument reliability and/or validity. Nearly one-half of these were conducted in South Africa and Egypt, which are classified as middle-income countries according to the World Bank (2013). This relative paucity of evidence from low-income countries in Africa parallels the findings of Kieling and Rohde (2012), who found that less than 1% of all articles on child and adolescent mental health found in Web of Science over the past decade involved an author from a low-income country. While most studies investigated instrument reliability, only a minority of studies investigated aspects of equivalence, criterion-related validity, or internal structure. As with Kieling et al. (2012) we also found more evidence of scholarship in recent years, with more than half of the articles in the sample published after 2009. Continued investments in capacity building and more collaborative editorial styles would help to ensure that these trends continue (Patel and Kim 2007). While the increasing international representation is welcome, similar patterns have not been observed in the general psychiatry literature (Helal, Ahmed, and Vostanis 2011; Patel et al. 2007; Patel and Sumathipala 2001).

The paucity of evidence notwithstanding, depression instruments were generally found to reliably measure depression-like constructs and to correlate with related constructs in the expected direction. Factor analyses, when done, tended to replicate the same factor structure as the original publication. While these may suggest some degree of conceptual or metric equivalence (Geisinger 2003), such a conclusion would be limited by the important fact that no instruments were studied in more than two contexts. Furthermore, although three-quarters of the studies were limited to persons 24 years of age and younger, only half of the studies were limited to persons 18 years of age or younger. Many studies combined adolescent and young adult populations but did not investigate the impact of age on scale reliability or validity despite the known developmental transformations observed during adolescence and early young adulthood (Giedd et al. 1999; Spear 2000).

The lack of established criterion standards clearly constrains the development and validation of depression assessment among African youth. Several studies of criterion-related validity relied on diagnostic interviews, such as the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview or Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-aged Children, to establish the reference criterion diagnosis. These practices, while helpful for ensuring comparability across contexts, adopt a reference criterion informed by Western concepts of mental disorders to assess the validity of a locally derived measure (Bass, Bolton, and Murray 2007). Only three studies investigated the validity of the diagnostic interview schedules themselves.

Several studies included in our review offer a promising way to address the gap in evidence on equivalence and validity of depression assessment among African youth. Betancourt and colleagues (Betancourt et al. 2011; Betancourt et al. 2009b), Mels et al. (2010), and Ertl et al. (2010) provide prototypical examples of using mixed methods (both qualitative and quantitative) to guide the process of cross-cultural development and validation of mental health assessment tools. These studies also suggest an alternative strategy for establishing the reference criterion, i.e., parent/caregiver report. However, these are not without limitations, as parent/caregiver and youth self-report are known vary in agreement by the type of mental disorder: namely, several studies have reported greater agreement for externalizing disorders compared to internalizing disorders (Duhig et al. 2000; Weisz et al. 1993). Advancing the field of mental health research in Africa requires concerted efforts to establish local criterion standards. In the meantime, the simultaneous use of several methods to arrive at criterion diagnoses, e.g. caregiver reports combined with local clinician assessments and structured diagnostic reviews, may be advised.

The results of our systematic review should be understood with the following limitations in mind. First, as with all systematic reviews, we must consider the possibility that publication bias could explain the relative paucity of identified research. This would have led us to underestimate the total volume of published journal articles and other reports in this literature. However, because it is unclear in this context whether studies demonstrating non-reliability or non-validity would be any less likely (or more likely) to be published compared to studies demonstrating reliability or validity, we believe publication bias is unlikely to have caused us to draw erroneous conclusions about the overall reliability or validity of this research. Related to the above, it is possible that the evidence search protocol may have missed some relevant studies. However, we believe this is unlikely given the comprehensiveness of our search strategy, which included three bibliographic databases specific to African literature. The sensitivity of our search strategy can also be assessed by comparing it to the search protocols underlying other published articles. For example, Sweetland et al. (2014) searched two bibliographic databases for validity studies conducted among adults in sub-Saharan Africa and published prior to 2012, and in doing so happened to identify 11 studies of pregnant or postpartum women. In comparison, a recently published systematic review focusing on pregnant or postpartum women in sub-Saharan Africa -- which adopted a search strategy nearly identical to ours -- identified 25 studies (Tsai et al. 2013). A third limitation is that we excluded studies in which internal consistency was the only form of reliability evidence reported. Because Cronbach’s alpha coefficients are near-universally reported, this decision made the first-stage screening more tractable -- as we were therefore not obliged to read the full text of all potentially relevant observational and experimental studies to determine whether a Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was reported for any depression instruments that happened to be employed in the study. Because observational studies not focused on psychometric analysis and experimental studies tend to employ only instruments that have previously been assessed for reliability and validity, excluding these studies would have likely biased our estimates of the reliability of depression instruments towards zero.

Conclusions

We reviewed seven bibliographic databases and identified only 23 studies assessing the reliability or validity of instruments used to screen for major depressive disorder or assess depression symptom severity among African youth. While more research is needed in this field in general, we believe that much more research is needed specifically to develop or validate locally relevant criterion standards. Some of the studies identified in our review employed qualitative methods to this end, and we believe research of this nature should be adopted more widely. Until then, existing instruments, mostly based on instruments derived from Western settings, can be used to reliably assess for depression, but the overall limited evidence base is an important barrier to sound programmatic and policy development for improving mental health among African youth.

Figure 1.

Quality of Reporting of Meta-Analyses flow chart depicting the number of reports screened and included in the systematic review.

Acknowledgments

No specific funding was awarded for the conduct of this study. Dr. Tomlinson acknowledges salary support from the National Research Foundation (South Africa) and the UK Agency for International Development. Dr. Tsai acknowledges salary support from U.S. National Institutes of Health K32MH096620 and the Robert Wood Johnson Health and Society Scholars Program. We thank Jennifer A. Scott and Jennifer Q. Zhu for their assistance with data collection.

References

- Abubakar A, Fischer R. The factor structure of the 12□item General Health Questionnaire in a literate Kenyan population. Stress and Health. 2012;28:248–254. doi: 10.1002/smi.1420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adewuya AO, Ola BA, Afolabi OO. Validity of the patient health questionnaire (PHQ-9) as a screening tool for depression amongst Nigerian university students. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2006a;96:89–93. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2006.05.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adewuya AO, Ola BA, Aloba OO. Prevalence of major depressive disorders and a validation of the Beck Depression Inventory among Nigerian adolescents. European Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2007;16:287–292. doi: 10.1007/s00787-006-0557-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adewuya AO, Ologun YA. Factors associated with depressive symptoms in Nigerian adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2006b;39:105–110. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2005.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aidoo M, Harpham T. The explanatory models of mental health amongst low-income women and health care practitioners in Lusaka, Zambia. Health Policy and Planning. 2001;16:206–213. doi: 10.1093/heapol/16.2.206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ambaw F. The structure and reliability of the Amharic version of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale in orphan adolescents in Addis Ababa. Ethiopian Journal of Health Sciences. 2011;21:27–35. doi: 10.4314/ejhs.v21i1.69041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Educational Research Association APA, and National Council on Measurement in Education . Standards for educational and psychological testing. American Psychological Association; Washington, D.C.: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Barke A, Nyarko S, Klecha D. The stigma of mental illness in Southern Ghana: attitudes of the urban population and patients' views. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology. 2011;46:1191–1202. doi: 10.1007/s00127-010-0290-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bass JK, Bolton PA, Murray LK. Do not forget culture when studying mental health. The Lancet. 2007;370:918–919. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61426-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bean T, Derluyn I, Eurelings-Bontekoe E, Broekaert E, Spinhoven P. Validation of the multiple language versions of the Hopkins Symptom Checklist-37 for refugee adolescents. Adolescence. 2007;42:51–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bebbington P. Transcultural aspects of affective disorders. International Review of Psychiatry. 1993;5:145–156. [Google Scholar]

- Bekhet AK, Zauszniewski JA. Psychometric properties of the Arabic version of the Depressive Cognition Scale in first-year adolescent Egyptian nursing students. Journal of Nursing Measurement. 2010;18:143–152. doi: 10.1891/1061-3749.18.3.143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Betancourt T, Scorza P, Meyers-Ohki S, Mushashi C, Kayiteshonga Y, Binagwaho A, Stulac S, Beardslee WR. Validating the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale for Children in Rwanda. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2012;51:1284–1292. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2012.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Betancourt T, Yang F, Bolton P, Normand S-LT. Developing an African Youth Psychosocial Assessment: an application of item response theory. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research. doi: 10.1002/mpr.1420. In press. Epub 30 Jan 2014. doi: 10.1002/mpr.1420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Betancourt TS, Bass J, Borisova I, Neugebauer R, Speelman L, Onyango G, Bolton P. Assessing local instrument reliability and validity: a field-based example from northern Uganda. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology. 2009a;44:685–692. doi: 10.1007/s00127-008-0475-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Betancourt TS, Rubin-Smith JE, Beardslee WR, Stulac SN, Fayida I, Safren S. Understanding locally, culturally, and contextually relevant mental health problems among Rwandan children and adolescents affected by HIV/AIDS. AIDS Care. 2011;23:401–412. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2010.516333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Betancourt TS, Speelman L, Onyango G, Bolton P. A qualitative study of mental health problems among children displaced by war in northern Uganda. Transcultural Psychiatry. 2009b;46:238–256. doi: 10.1177/1363461509105815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brislin RW. Understanding culture's influence on behavior. 1st Harcourt Brace Jovanovich; Fort Worth: 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Cherian VI, Peltzer K, Cherian L. The factor-structure of the Self Reporting Questionnaire (SRQ-20) in South Africa. East African Medical Journal. 1998;75:654–656. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cortina MA, Sodha A, Fazel M, Ramchandani PG. Prevalence of child mental health problems in Sub-saharan Africa: a systematic review. Archives of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine. 2012;166:276–281. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2011.592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crabb J, Stewart RC, Kokota D, Masson N, Chabunya S, Krishnadas R. Attitudes towards mental illness in Malawi: a cross-sectional survey. BMC Public Health. 2012;12:541. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-12-541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duhig AM, Renk K, Epstein MK, Phares V. Interparental agreement on internalizing, externalizing, and total behavior problems: a meta□analysis. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. 2000;7:435–453. [Google Scholar]

- El-Missiry A, Soltan M, Abdel Hadi M, Sabry W. Screening for depression in a sample of Egyptian secondary school female students. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2012;136:e61–e68. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2011.06.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ertl V, Pfeiffer A, Saile R, Schauer E, Elbert T, Neuner F. Validation of a mental health assessment in an African conflict population. Psychological Assessment. 2010;22:318–324. doi: 10.1037/a0018810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fawzi M, El-Maghraby Z, El-Amin H, Sahloul M. The Zagazig Depression Scale manual. El-Nahda El-Massriya; Cairo: 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Ferrari AJ, Charlson FJ, Norman RE, Patten SB, Freedman G, Murray CJ, Vos T, Whiteford HA. Burden of depressive disorders by country, sex, age, and year: findings from the global burden of disease study 2010. Public Library of Science Medicine. 2013;10:e1001547. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flisher AJ, Sorsdahl KR, Lund C. Test-retest reliability of the Xhosa version of the Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children. Child: Care, Health and Development. 2012;38:261–265. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2214.2010.01195.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geisinger KF. Testing and assessment in cross-cultural psychology. In: Graham JR, Naglieri JA, Weiner IB, editors. Handbook of psychology. Volume 10: Assessment psychology. John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; Hoboken: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Giedd JN, Blumenthal J, Jeffries NO, Castellanos FX, Liu H, Zijdenbos A, Paus T, Evans AC, Rapoport JL. Brain development during childhood and adolescence: a longitudinal MRI study. Nature Neuroscience. 1999;2:861–863. doi: 10.1038/13158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg DP. Maudsley Monograph No. 21. Oxford University Press; London: 1972. The detection of psychiatric illness by questionnaire. [Google Scholar]

- Gureje O, Lasebikan VO, Ephraim-Oluwanuga O, Olley BO, Kola L. Community study of knowledge of and attitude to mental illness in Nigeria. British Journal of Psychiatry. 2005;186:436–441. doi: 10.1192/bjp.186.5.436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helal MN, Ahmed U, Vostanis P. Do psychiatric journals reflect universal representation? European Psychiatry. 2011;26:442. [Google Scholar]

- Ibrahim AK, Kelly SJ, Glazebrook C. Reliability of a shortened version of the Zagazig Depression Scale and prevalence of depression in an Egyptian university student sample. Comprehensive Psychiatry. 2012;53:638–647. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2011.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kagee A, Tsai AC, Lund C, Tomlinson M. Screening for common mental disorders: reasons for caution and a way forward. International Health. 2013;5:11–14. doi: 10.1093/inthealth/ihs004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kapungwe A, Cooper S, Mwanza J, Mwape L, Sikwese A, Kakuma R, Lund C, Flisher AJ, Consortium MHRP. Mental illness--stigma and discrimination in Zambia. African Journal of Psychiatry. 2010;13:192–203. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kebede M, Kebede D, Desta M, Alem A. Evaluation of the Amharic version of the diagnostic Interview of Children and Adolescents (DICA-R) in Addis Ababa. Ethiopian Journal of Health Development. 2000;14:13–22. [Google Scholar]

- Kieling C, Rohde LA. Child and adolescent mental health research across the globe. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2012;51:945–947. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2012.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowenthal E, Lawler K, Harari N, Moamogwe L, Masunge J, Masedi M, Matome B, Seloilwe E, Jellinek M, Murphy M, Gross R. Validation of the Pediatric Symptom Checklist in HIV-infected Batswana. Journal of Child and Adolescent Mental Health. 2011;23:17–28. doi: 10.2989/17280583.2011.594245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mels C, Derluyn I, Broekaert E, Rosseel Y. Community-based cross-cultural adaptation of mental health measures in emergency settings: validating the IES-R and HSCL-37A in Eastern Democratic Republic of Congo. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology. 2010;45:899–910. doi: 10.1007/s00127-009-0128-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moorey S, Greer S, Watson M, Gorman C, Rowden L, Tunmore R, Robertson B, Bliss J. The factor structure and factor stability of the hospital anxiety and depression scale in patients with cancer. British Journal of Psychiatry. 1991;158:255–259. doi: 10.1192/bjp.158.2.255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okello ES. Cultural explanatory models of depression in Uganda. Institutionen för Klinisk Neurovetenskap, Karolinska Institutet; Stockholm: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Okello ES, Ekblad S. Lay concepts of depression among the Baganda of Uganda: a pilot study. Transcultural Psychiatry. 2006;43:287–313. doi: 10.1177/1363461506064871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel V, Kim YR. Contribution of low- and middle-income countries to research published in leading general psychiatry journals, 2002-2004. British Journal of Psychiatry. 2007;190:77–78. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.106.025692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel V, Sumathipala A. International representation in psychiatric literature: survey of six leading journals. British Journal of Psychiatry. 2001;178:406–409. doi: 10.1192/bjp.178.5.406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pretorius TB. Cross-cultural application of the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale: a study of black South African students. Psychological Reports. 1991;69:1179–1185. doi: 10.2466/pr0.1991.69.3f.1179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pretorius TB. Measuring life events in a sample of South African students: comparison of the Life Experiences Survey and the Schedule of Recent Experiences. Psychological Reports. 1998;83:771–780. doi: 10.2466/pr0.1998.83.3.771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radloff LS. The CES-D scale: a self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement. 1977;1:385–401. [Google Scholar]

- Rothon C, Stansfeld SA, Mathews C, Kleinhans A, Clark C, Lund C, Flisher AJ. Reliability of self report questionnaires for epidemiological investigations of adolescent mental health in Cape Town, South Africa. Journal of Child and Adolescent Mental Health. 2011;23:119–128. doi: 10.2989/17280583.2011.634551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saxena S, Thornicroft G, Knapp M, Whiteford H. Resources for mental health: scarcity, inequity, and inefficiency. The Lancet. 2007;370:878–889. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61239-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharp C, Skinner D, Serekoane M, Ross MW. A qualitative study of the cultural appropriateness of the Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children (DISC-IV) in South Africa. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology. 2011;46:743–751. doi: 10.1007/s00127-010-0241-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spear LP. The adolescent brain and age-related behavioral manifestations. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews. 2000;24:417–463. doi: 10.1016/s0149-7634(00)00014-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sweetland AC, Belkin GS, Verdeli H. Measuring depression and anxiety in sub-Saharan Africa. Depression and Anxiety. 2014;31:223–232. doi: 10.1002/da.22142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomlinson M, Lund C. Why does mental health not get the attention it deserves? An application of the Shiffman and Smith framework. Public Library of Science Medicine. 2012;9:e1001178. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomlinson M, Swartz L, Kruger LM, Gureje O. Manifestations of affective disturbance in sub-Saharan Africa: key themes. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2007;102:191–198. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2006.09.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Traube D, Dukay V, Kaaya S, Reyes H, Mellins C. Cross-cultural adaptation of the Child Depression Inventory for use in Tanzania with children affected by HIV. Vulnerable Children and Youth Studies. 2010;5:174–187. doi: 10.1080/17450121003668343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai AC, Scott JA, Hung KJ, Zhu JQ, Matthews LT, Psaros C, Tomlinson M. Reliability and validity of instruments for assessing perinatal depression in African settings: systematic review and meta-analysis. Public Library of Science One. 2013;8:e82521. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0082521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ventevogel P, Jordans M, Reis R, de Jong J. Madness or sadness? Local concepts of mental illness in four conflict-affected African communities. Conflict and Health. 2013;7:3. doi: 10.1186/1752-1505-7-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ward CL, Flisher AJ, Zissis C, Muller M, Lombard C. Reliability of the Beck Depression Inventory and the Self-Rating Anxiety Scale in a sample of South African adolescents. Journal of Child and Adolescent Mental Health. 2003;15:73–75. doi: 10.2989/17280580309486550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weisz JR, Sigman M, Weiss B, Mosk J. Parent reports of behavioral and emotional problems among children in Kenya, Thailand, and the United States. Child Development. 1993;64:98–109. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1993.tb02897.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whiteford HA, Degenhardt L, Rehm J, Baxter AJ, Ferrari AJ, Erskine HE, Charlson FJ, Norman RE, Flaxman AD, Johns N, Burstein R, Murray CJL, Vos T. Global burden of disease attributable to mental and substance use disorders: findings from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. The Lancet. 2013;382:1575–1586. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61611-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Bank . World development indicators. World Bank; Washington, D.C.: 2013. 2013. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization . Mental health action plan 2013-2020. World Health Organization; Geneva: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Zauszniewski JA. Development and testing of a measure of depressive cognitions in older adults. Journal of Nursing Measurement. 1995;3:31–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zigmond AS, Snaith RP. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 1983;67:361–370. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1983.tb09716.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]