Abstract

Objective To investigate the association between treatment with an angiotensin receptor blocker and clinical outcomes in patients with ST segment elevation myocardial infarction with preserved left ventricular systolic function.

Design A prospective cohort study using data from a nationwide large scale registry.

Setting 53 hospitals involved in treatment of acute myocardial infarction in Korea.

Participants Between November 2005 and September 2010, we studied 6698 patients with ST segment elevation myocardial infarction who underwent primary percutaneous coronary intervention and had a left ventricular ejection fraction ≥40%.

Main outcome measures Cardiac death or myocardial infarction. Patients were divided into an angiotensin receptor blocker group (n=1185), an angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitor group (n=4564), and a group who did not receive any renin angiotensin system blocker (n=949). Propensity score matching analysis was also performed.

Results Cardiac death or myocardial infarction occurred in 21 patients (1.8%) in the angiotensin receptor blocker group, 77 patients (1.7%) in the ACE inhibitor group, and 33 patients (3.5%) in the no renin angiotensin system blocker group. After propensity score matching (1175 pairs), there was no significant difference in the rate of cardiac death or myocardial infarction between the angiotensin receptor blocker group and ACE inhibitor group (21 (1.8%) v 23 (2.0%), adjusted hazard ratio 0.65, 95% confidence interval 0.30 to 1.38; P=0.65). The angiotensin receptor blocker group had a lower rate of cardiac death or myocardial infarction than the no renin angiotensin system blocker group in matched populations (803 pairs) (14 (1.7%) v 25 (3.1%), 0.35, 0.14 to 0.90; P=0.03).

Conclusion Angiotensin receptor blocker showed beneficial effects comparable with ACE inhibitors in patients with ST segment elevation myocardial infarction with preserved left ventricular systolic function. Angiotensin receptor blockers could be used as an alternative to ACE inhibitors in such patients.

Introduction

Angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors are beneficial and strongly recommended in patients with ST segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) with heart failure or left ventricular systolic dysfunction.1 2 ACE inhibitors can also be useful in STEMI patients with preserved left ventricular systolic function.3 4 Up to 20% of patients, however, cannot tolerate ACE inhibitors because of adverse reactions such as the development of cough and angio-oedema.5 6 Angiotensin receptor blockers could be an alternative to ACE inhibitors in STEMI patients with heart failure or left ventricular systolic dysfunction, particularly those who are intolerant to ACE inhibitors.3 4 No data are available, however, on the role of angiotensin receptor blocker in patients with STEMI and preserved left ventricular systolic function. Additionally, current guidelines do not cover the use of angiotensin receptor blocker in low risk patients with STEMI. As angiotensin receptor blockers are equivalent to ACE inhibitors in patients who have vascular disease or high risk diabetes but do not have heart failure,7 they could be beneficial in STEMI patients with preserved left ventricular systolic function. We sought to investigate the association between treatment with an angiotensin receptor blocker at discharge and clinical outcomes in STEMI patients with preserved left ventricular systolic function after primary percutaneous coronary intervention. We used data from a nationwide large scale registry dedicated to myocardial infarction.

Methods

Study population

The study population was selected from the Korean Acute Myocardial Infarction Registry (KAMIR). This is a nationwide prospective multicentre registry of patients presenting with acute myocardial infarction from 53 centres.8 9 10 Participating centres have a high volume of patients and have facilities for primary percutaneous coronary intervention and onsite cardiac surgery. Between November 2005 and September 2010, the registry prospectively enrolled 20 344 consecutive patients with acute myocardial infarction. A trained study coordinator collected clinical, laboratory, and outcome data using a standardised case report form and protocol. When necessary, we documented additional information by contacting the principal investigators at each hospital or reviewing hospital records, or both. The registry is sponsored by the Korean Society of Cardiology.

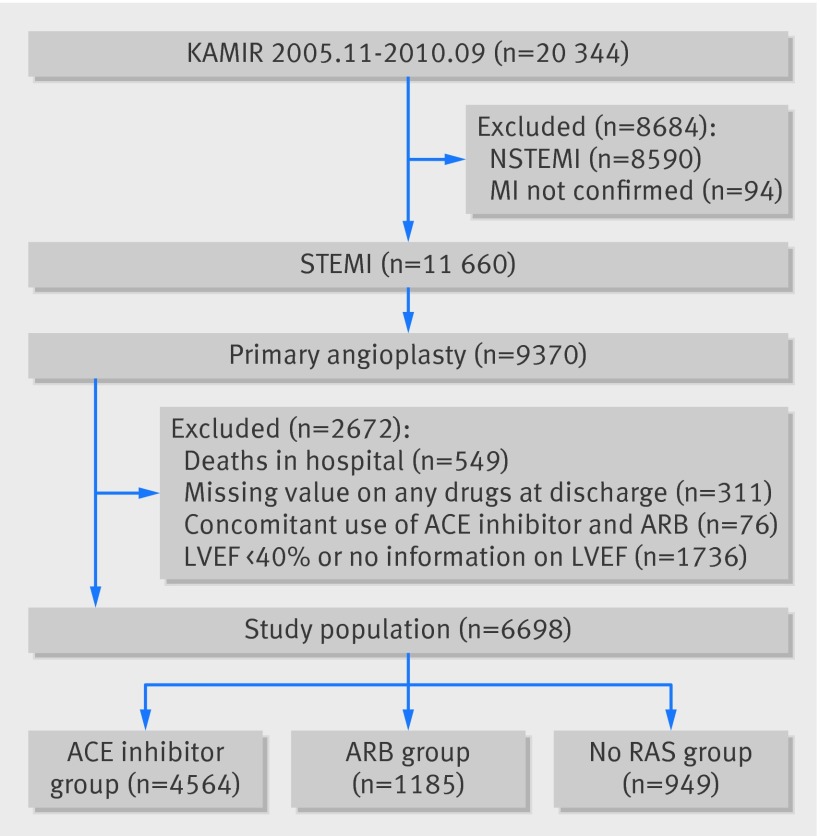

Inclusion criteria for the present analysis were consecutive patients aged ≥18; ST segment elevation >1 mm in at least two contiguous leads or a presumably new left bundle branch block with increased cardiac enzyme activity (troponin or fraction of biochemical markers of creatine kinase); and patients undergoing primary percutaneous coronary intervention. We excluded patients who died in hospital; lacked documentation of drugs prescribed at discharge; concomitantly used an ACE inhibitor and angiotensin receptor blocker; or had a left ventricular ejection fraction <40% or lacked information on left ventricular ejection fraction. From registered patients, we ultimately included 6698 in this analysis (fig 1). Patients were divided into an angiotensin receptor blocker group, ACE inhibitor group, or no renin angiotensin system blocker group according to the use of angiotensin receptor blocker or ACE inhibitors at discharge.

Fig 1 Group distribution in registry. KAMIR=Korean Acute Myocardial Infarction Registry, MI=myocardial infarction, STEMI=ST segment elevation myocardial infarction, NSTEMI=non-ST segment elevation myocardial infarction, ARB=angiotensin receptor blocker, No RAS=no renin angiotensin system blocker, LVEF=left ventricular ejection fraction

Percutaneous coronary intervention procedure

Coronary interventions were performed with a standard technique. All patients received a 300 mg loading dose of aspirin and a 300-600 mg loading dose of clopidogrel before the intervention, unless they had previously received these antiplatelet drugs. Anticoagulation during percutaneous coronary interventions was performed according to current practice guidelines established by the Korean Society of Interventional Cardiology. Decisions as to whether to perform thrombus aspiration or to use glycoprotein IIb/IIIa receptor inhibitors or intravascular ultrasonography were left to the operator’s discretion. Drug eluting stents were used without restriction. The duration of dual antiplatelet therapy was determined by operators.

Definitions and outcomes

Primary percutaneous coronary intervention was defined as percutaneous coronary revascularisation performed within 12 hours of onset of symptoms without antecedent treatment with a fibrinolytic agent as the initial treatment or with ongoing ischaemia between 12 and 24 hours.4 All deaths were considered to be cardiac unless a definite non-cardiac cause could be established. Myocardial infarction was defined as recurrent symptoms with new changes on electrocardiography compatible with myocardial infarction or levels of cardiac marker at least twice the upper limit of normal.11 All events were identified by the patient’s physician and confirmed by the principal investigator of each hospital. The primary outcome was cardiac death or myocardial infarction during follow-up. Secondary outcomes included all cause death, cardiac death, and myocardial infarction during follow-up.

Statistical analysis

We used t tests or Wilcoxon rank sum tests, when applicable, to compare continuous variables and χ2 tests for categorical data. Survival curves were constructed with Kaplan-Meier estimates and compared with the log rank test. The Cox proportional hazards model was used to compare the risks of adverse cardiac events between the angiotensin receptor blocker and ACE inhibitor groups and between the angiotensin receptor blocker and no renin angiotensin system blocker groups, respectively.

We included in multivariate models those covariates that were significant on univariate analysis and those that were clinically relevant. The propensity scores were estimated with multiple logistic regression analysis. We developed a full non-parsimonious model that included all variables as shown in tables 1 and 2 . Each pair was matched by a greedy algorithm and the nearest available pair matching method among patients with an individual propensity score. The covariate balance achieved by matching was assessed by calculating the absolute standardised differences in covariates between the two groups. An absolute standardised difference of <10.0% for the measured covariate suggests an appropriate balance between the groups. In the propensity score matched population, we compared continuous variables with a paired t test or the Wilcoxon signed rank test and categorical variables with the McNemar’s or Bowker’s test of symmetry. The reduction in the risk of an outcome was compared with the stratified Cox regression model. We included covariates with an absolute standardised difference of >10% in the multivariate models because the combination of regression adjustment in matched samples generally produces the least biased estimate.12

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of patients with ST segment elevation myocardial infarction with preserved left ventricular systolic function according to treatment at discharge. Figures are numbers (percentage) of patients unless stated otherwise

| Variables | ARB (n=1185) | ACEI (n=4564) | No RAS (n=949) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ARB v ACEI | ARB v no RAS | ||||

| Mean (SD) age (years) | 63.0 (12.9) | 61.4 (12.7 | 62.8 (12.8) | <0.001 | 0.78 |

| Men | 867 (73.2) | 3491 (76.5) | 699 (73.7) | 0.02 | 0.80 |

| Medical history: | |||||

| Diabetes mellitus | 279 (23.5) | 1038 (22.7) | 220 (23.2) | 0.56 | 0.84 |

| Hypertension | 620 (52.3) | 2001 (43.8) | 385 (40.6) | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Dyslipidaemia | 104 (8.8) | 502 (11.0) | 98 (10.3) | 0.03 | 0.22 |

| Smoking | 508 (42.9) | 2288 (50.1) | 460 (48.5) | <0.001 | 0.01 |

| Chronic kidney disease | 9 (0.8) | 27 (0.6) | 7 (0.7) | 0.51 | 0.95 |

| Family history of CAD | 90 (7.6) | 385 (8.4) | 66 (7.0) | 0.35 | 0.57 |

| Previous history of MI | 67 (5.7) | 198 (4.3) | 50 (5.3) | 0.05 | 0.70 |

| Previous history of PCI | 66 (5.6) | 161 (3.5) | 43 (4.5) | 0.001 | 0.28 |

| Previous CABG | 3 (0.3) | 10 (0.2) | 6 (0.6) | 0.74 | 0.20 |

| Previous CVA | 61 (5.1) | 222 (4.9) | 37 (3.9) | 0.69 | 0.17 |

| Previous history of heart failure | 16 (1.4) | 17 (0.4) | 5 (0.5) | <0.001 | 0.06 |

| Killip class ≥III on admission | 110 (9.3) | 404 (8.9) | 124 (13.1) | 0.64 | 0.005 |

| Mean (SD) left ventricle ejection fraction | 53.8 (9.2) | 54.1 (8.8) | 53.5 (9.4) | 0.33 | 0.43 |

| Mean (SD) serum creatinine (µmol/L) | 97.24 (81.33) | 91.94 (64.53) | 97.24 (60.11) | 0.02 | 0.96 |

| Mean (SD) symptom to balloon time (min) | 369.8 (300.3) | 363.4 (290.4) | 383.6 (304.9) | 0.50 | 0.30 |

| Drugs at discharge: | |||||

| Aspirin | 1175 (99.2) | 4529 (99.2) | 920 (96.9) | 0.79 | <0.001 |

| Clopidogrel | 1174 (99.1) | 4474 (98.0) | 909 (95.8) | 0.02 | <0.001 |

| β blocker | 956 (80.7) | 3961 (86.8) | 570 (60.1) | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Statins | 967 (81.6) | 3810 (83.5) | 755 (79.6) | 0.13 | 0.23 |

ARB=angiotensin receptor blocker; ACEI=angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor; CABG=coronary artery bypass grafting; CAD=coronary artery disease; CVA=cerebrovascular event; MI=myocardial infarction; PCI=percutaneous coronary intervention; RAS=renin angiotension system.

Table 2.

Angiographic and procedural characteristics in patients with ST segment elevation myocardial infarction with preserved left ventricular systolic function according to treatment at discharge. Figures are numbers (percentage) of patients unless stated otherwise

| Variables | ARB (n=1185) | ACEI (n=4564) | No RAS (n=949) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ARB v ACEI | ARB v No RAS | ||||

| LAD infarct related artery | 651 (54.9) | 2325 (50.9) | 445 (46.9) | 0.01 | <0.001 |

| Multi-vessel coronary artery disease | 559 (47.2) | 2188 (47.9) | 469 (49.4) | 0.64 | 0.30 |

| ACC/AHA B2/C lesion | 881 (74.3) | 3652 (80.0) | 743 (78.3) | <0.001 | 0.03 |

| Pre-procedural TIMI flow grade 0 or 1 | 873 (73.7) | 3327 (72.9) | 704 (74.2) | 0.59 | 0.79 |

| Post-procedural TIMI flow grade 3 | 1112 (93.8) | 4284 (93.9) | 860 (90.6) | 0.97 | 0.005 |

| PCI with stent | 1105 (93.2) | 4306 (94.3) | 862 (90.8) | 0.15 | 0.04 |

| Mean (SD) maximal stent diameter (mm) | 3.20 (0.39) | 3.23 (0.41) | 3.20 (0.42) | 0.03 | 0.99 |

| Mean (SD) total stent length (mm) | 24.8 (5.9) | 24.7 (5.8) | 25.1 (6.3) | 0.58 | 0.16 |

| Vasopressor | 162 (13.7) | 668 (14.6) | 198 (20.9) | 0.40 | <0.001 |

| Intra-aortic balloon pump | 25 (2.1) | 120 (2.6) | 40 (4.2) | 0.31 | 0.005 |

| Defibrillator/cardioversion | 32 (2.7) | 157 (3.4) | 46 (4.8) | 0.20 | 0.009 |

| Temporary pacemaker | 56 (4.7) | 289 (6.3) | 70 (7.4) | 0.04 | 0.01 |

ARB=angiotensin receptor blocker; ACEI=angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor; RAS=renin angiotension system; ACC/AHA=American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association; LAD=left anterior descending artery; PCI=percutaneous coronary intervention; TIMI=thrombolysis in myocardial infarction.

Cumulative incidence rates of individual clinical outcomes and composite outcomes were estimated by the Kaplan-Meier method and compared by the paired Prentice-Wilcoxon test. Statistical analyses were performed with SAS 9.2 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). All tests were two tailed and P<0.05 was considered significant.

Results

Baseline and procedural characteristics

Overall population

Among the 6698 eligible patients, at discharge angiotensin receptor blockers were prescribed to 1185 patients (17.7%) and ACE inhibitors to 4564 patients (68.1%). Renin angiotensin system blockers were not prescribed to 949 patients (14.2%). Table 1 shows the baseline clinical characteristics; table 2 shows the angiographic and procedural characteristics. Compared with patients in the ACE inhibitor group, those in the angiotensin receptor blocker group were older, had higher creatinine concentrations, more had and the left anterior descending artery as the infarct related artery, but had a lower prevalence of smoking and B2/C lesions (according to the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association). Overall, those who did not receive any renin angiotensin system blocker were higher risk patients. Compared with patients in the angiotensin receptor blocker group, those in the no renin angiotensin system blocker group had a higher prevalence of smoking, Killip class ≥III, and B2/C lesions, but a lower prevalence of hypertension, left anterior descending artery as the infarct related artery, and post-procedural TIMI (thrombolysis in myocardial infarction) flow grade of 3. In addition, patients who received no renin angiotensin system blocker were less likely to have received aspirin, clopidogrel, β blockers, or percutaneous coronary intervention with a stent, but more likely to have received vasopressors, an intra-aortic balloon pump, defibrillator/cardioversion, or a temporary pacemaker.

Propensity matched population

After performing propensity score matching for the entire population, we created 1175 (angiotensin receptor blocker v ACE inhibitor) and 803 (angiotensin receptor blocker v no renin angiotensin system blocker) matched pairs of patients (see tables A and B in appendix). The C statistics for the propensity score model were 0.61 and 0.68, respectively, suggesting that the use of angiotensin receptor blocker was relatively random and would make the analysis more reliable (Hosmer-Lemeshow goodness of fit, P=0.42 and P=0.76, respectively). There were no significant differences in baseline clinical, angiographic, and procedural characteristics between the angiotensin receptor blocker and ACE inhibitor groups for the propensity matched subjects, and between the angiotensin receptor blocker and no renin angiotensin system blocker groups except for the use of β blockers.

Clinical outcomes

Overall population

The median duration of follow-up was 371 days (interquartile range 167-450). Table 3 shows the cumulative clinical outcomes of the study groups. Cardiac death or myocardial infarction occurred in 21 patients (1.8%) in the angiotensin receptor blocker group, 77 patients (1.7%) in the ACE inhibitor group (P=0.92 for comparison with angiotensin receptor blocker,) and 33 patients (3.5%) in the no renin angiotensin system blocker group (P=0.004 for comparison with angiotensin receptor blocker).

Table 3.

Clinical outcomes in patients with ST segment elevation myocardial infarction with preserved left ventricular systolic function according to treatment during follow-up. Figures are numbers (percentage) of patients and hazard ratios (95% confidence interval)

| Angiotensin receptor blocker (n=1185) | Comparison group* | Unadjusted | Adjusted† | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95% CI) | P value | HR* (95% CI) | P value | ||||

| Comparison with ACE inhibitor (total population=5749) | |||||||

| Cardiac death or MI | 21 (1.8) | 77 (1.7) | 1.02 (0.63 to 1.66) | 0.92 | 0.94 (0.58 to 1.53) | 0.79 | |

| All cause death | 32 (2.7) | 64 (1.4) | 1.85 (1.21 to 2.83) | 0.01 | 1.54 (1.00 to 2.37) | 0.05 | |

| Cardiac death | 15 (1.3) | 35 (0.8) | 1.61 (0.88 to 2.96) | 0.12 | 1.33 (0.72 to 2.46) | 0.36 | |

| Myocardial infarction | 7 (0.6) | 43 (0.9) | 0.61 (0.27 to 1.35) | 0.22 | 0.59 (0.26 to 1.31) | 0.19 | |

| Comparison with no renin angiotensin system blocker (total n=2134) | |||||||

| Cardiac death or MI | 21 (1.8) | 33 (3.5) | 0.44 (0.25 to 0.76) | 0.004 | 0.49 (0.27 to 0.87) | 0.02 | |

| All cause death | 32 (2.7) | 29 (3.1) | 0.74 (0.45 to 1.23) | 0.25 | 0.82 (0.48 to 1.40) | 0.47 | |

| Cardiac death | 15 (1.3) | 18 (1.9) | 0.57 (0.29 to 1.13) | 0.11 | 0.69 (0.33 to 1.44) | 0.32 | |

| Myocardial infarction | 7 (0.6) | 15 (1.6) | 0.33 (0.13 to 0.81) | 0.02 | 0.29 (0.11 to 0.76) | 0.01 | |

*n=4564 for ACE inhibitor group and 949 for no renin angiotensin system blocker group

†For comparison with ACE inhibitor group, adjusted for age, sex, hypertension, previous history of myocardial infarction, creatinine, left anterior descending artery as infarct related artery, use of clopidogrel, β blocker, and angiotensin receptor blocker at discharge. For comparison with no renin angiotensin system blocker group, adjusted for hypertension, Killip class ≥III on admission, left anterior descending artery as infarct related artery, post-procedural TIMI flow grade 3 on culprit vessel, use of vasopressor and intra-aortic balloon pump during admission, use of aspirin, clopidogrel, β blocker, and angiotensin receptor blocker at discharge.

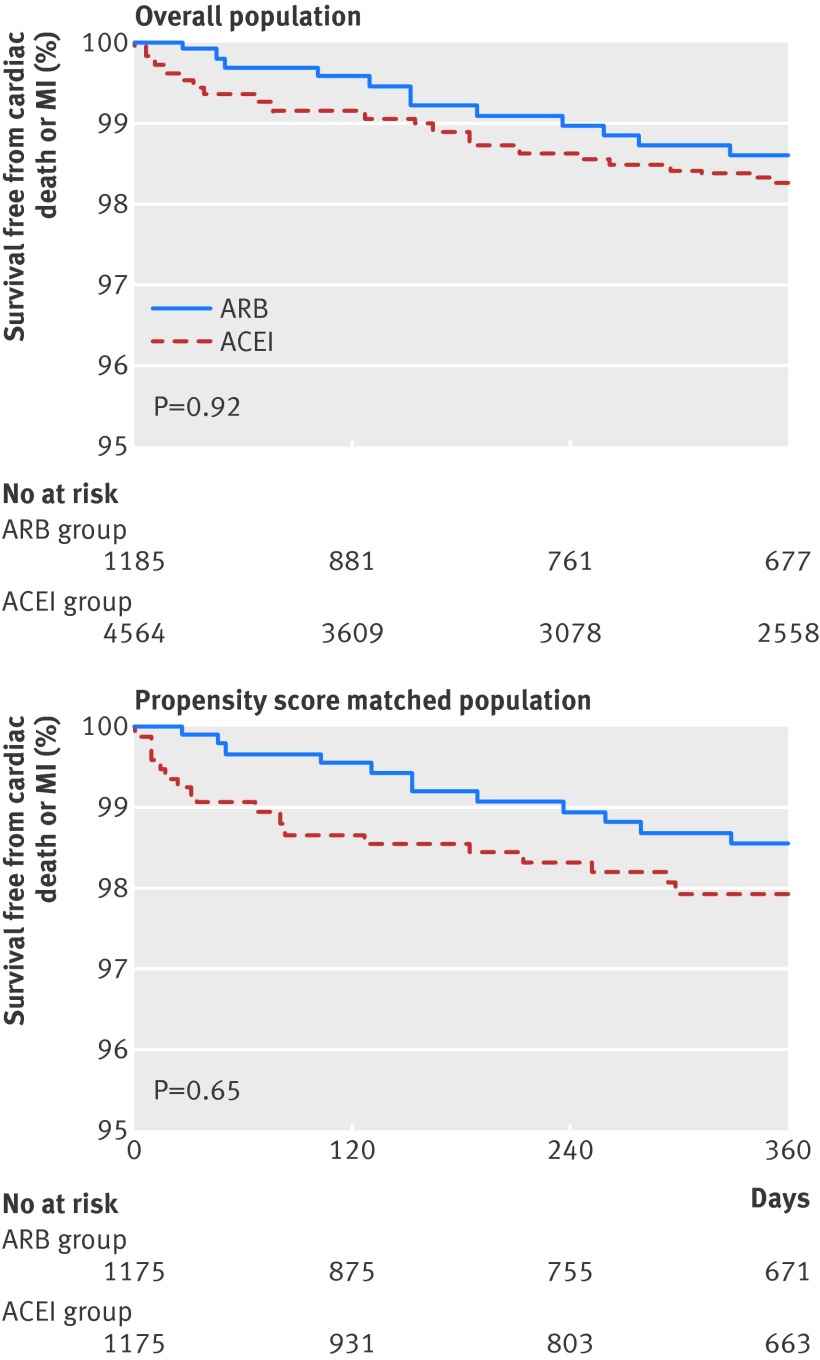

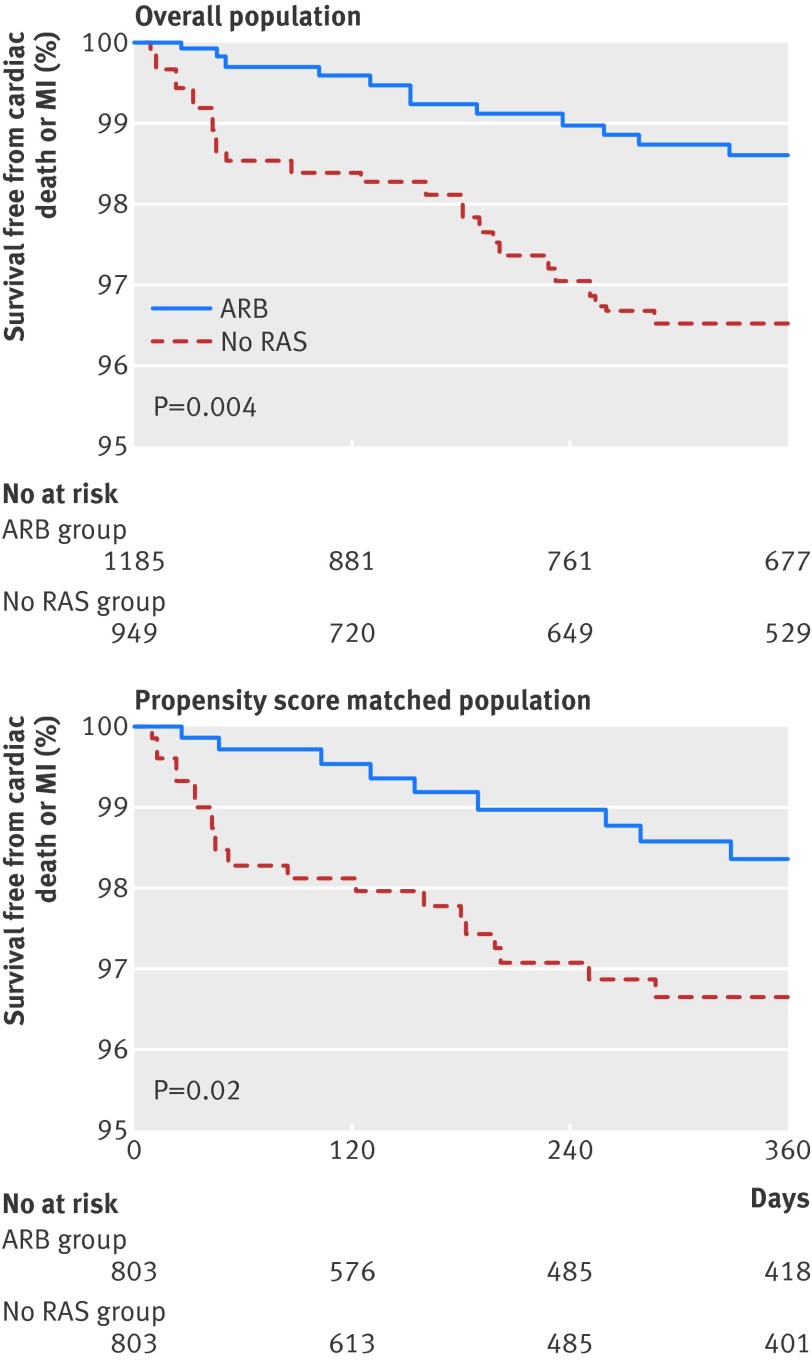

On Cox regression analysis, both angiotensin receptor blocker and ACE inhibitor groups had similar risk of cardiac death or myocardial infarction (1.8% v 1.7%; adjusted hazard ratio 0.94, 95% confidence interval 0.58 to 1.53; P=0.79) (fig 2) after adjustment for age, sex, hypertension, history of myocardial infarction, creatinine concentration, left anterior descending artery as the infarct related artery, and use of clopidogrel, β blocker, and angiotensin receptor blocker at discharge. Treatment with an angiotensin receptor blocker was associated with a lower incidence of cardiac death or myocardial infarction compared with no renin angiotensin system blocker (1.8% v 3.5%; 0.49, 0.27 to 0.87; P=0.02) (fig 3) after adjustment for hypertension, Killip class ≥III on admission, left anterior descending artery as the infarct related artery, post-procedural TIMI flow grade 3 on culprit vessel, use of vasopressor and intra-aortic balloon pump during admission, and use of aspirin, clopidogrel, β blocker, and angiotensin receptor blocker at discharge. The incidence of myocardial infarction was significantly lower in the angiotensin receptor blocker group than in the no renin angiotensin system blocker group (0.6% v 1.6%; 0.29, 0.11 to 0.76; P=0.01).

Fig 2 Kaplan-Meier curves for cardiac death or myocardial infarction (MI) with angiotensin receptor blocker (ARB) compared with ACE inhibitor in overall population and propensity matched population

Fig 3 Kaplan-Meier curves for cardiac death or myocardial infarction (MI) with angiotensin receptor blocker (ARB) compared with no renin angiotensin system (RAS) blockade in overall population and propensity matched populations

Propensity matched population

After 1:1 propensity score matching, cardiac death or myocardial infarction during follow-up was not significantly different between the angiotensin receptor blocker and ACE inhibitor groups (1.8% v 2.0%; adjusted hazard ratio 0.65, 95% confidence interval 0.30 to 1.38; P=0.65) (fig 2). Compared with no renin angiotensin system blocker, treatment with an angiotensin receptor blocker was associated with a lower incidence of cardiac death or myocardial infarction after adjustment for use of β blocker at discharge (1.7% v 3.1%; 0.35, 0.14 to 0.90; P=0.03) (fig 3 and table 4).

Table 4.

Clinical outcomes in patients with ST segment elevation myocardial infarction with preserved left ventricular systolic according to treatment at discharge and during follow-up in propensity matched population. Figures are numbers (percentage) of patients and hazard ratios (95% confidence interval)

| Propensity matched population | Angiotensin receptor blocker | Comparison group | Adjusted* HR (95% CI) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Comparison with ACE inhibitor (n=1175 in each group | ||||

| Cardiac death or MI | 21 (1.8) | 23 (2.0) | 0.65 (0.30 to 1.38) | 0.65 |

| All cause death | 32 (2.7) | 18 (1.5) | 1.23 (0.59 to 2.56) | 0.58 |

| Cardiac death | 15 (1.3) | 11 (0.9) | 1.14 (0.41 to 3.15) | 0.80 |

| Myocardial infarction | 7 (0.6) | 12 (1.0) | 0.30 (0.08 to 1.09) | 0.07 |

| Comparison with no renin angiotensin system blocker (n=803 in each group) | ||||

| Cardiac death or MI | 14 (1.7) | 25 (3.1) | 0.35 (0.14 to 0.90) | 0.03 |

| All cause death | 21 (2.6) | 23 (2.9) | 0.81 (0.36 to 1.85) | 0.62 |

| Cardiac death | 10 (1.2) | 13 (1.6) | 0.47 (0.14 to 1.56) | 0.22 |

| Myocardial infarction | 4 (0.5) | 12 (1.5) | 0.25 (0.05 to 1.18) | 0.08 |

MI=myocardial infarction.

*Adjusted for use of β blocker at discharge.

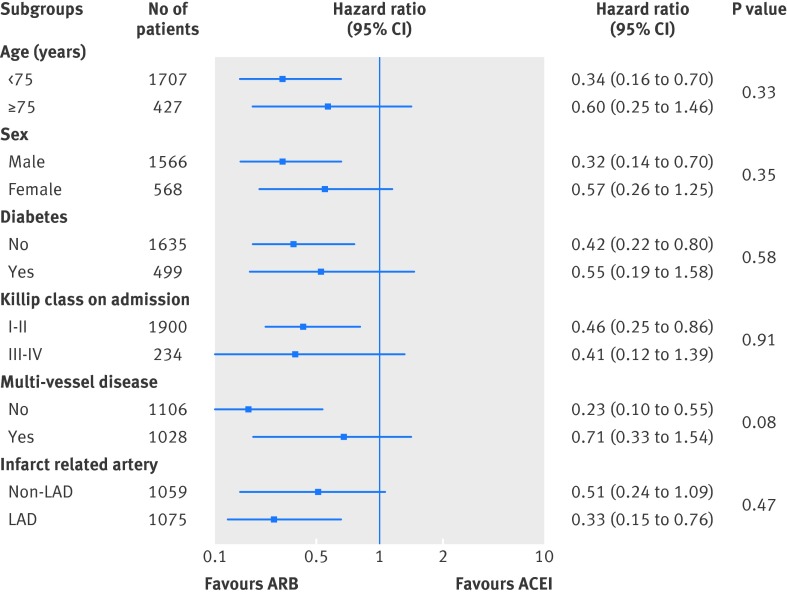

Subgroup analysis

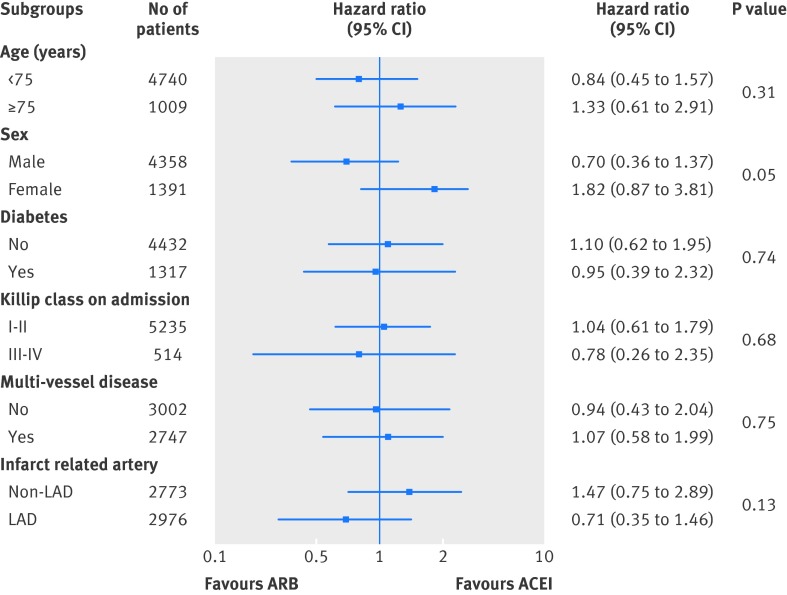

To determine whether the outcomes related to treatment with an angiotensin receptor blocker (v ACE inhibitor and no renin angiotensin system blocker) observed in the overall population were consistent, we calculated the unadjusted hazard ratio for cardiac death or myocardial infarction in various complex subgroups (figs 4 and 5 ). There were no significant interactions between the use of angiotensin receptor blocker at discharge and cardiac death or myocardial infarction in any of the subgroups. Compared with the no renin angiotensin system blocker group, the association between better outcome and treatment with angiotensin receptor blocker in terms of cardiac death or myocardial infarction was consistent across various subgroups, including in patients with non-anterior myocardial infarction, Killip class I or II, and single vessel disease in contrast with comparable results between angiotensin receptor blocker and ACE inhibitor in the rates of cardiac death or myocardial infarction (fig 5).

Fig 4 Comparative unadjusted hazard ratios of cardiac death or myocardial infarction for subgroups in overall populations between angiotensin receptor blocker (ARB) and ACE inhibitor groups. LAD=left anterior descending artery

Fig 5 Comparative unadjusted hazard ratios of cardiac death or myocardial infarction for subgroups in overall populations between angiotensin receptor blocker (ARB) and no renin angiotensin system (RAS) blockade groups. LAD=left anterior descending artery

Discussion

Principal findings

In patients with ST segment elevation myocardial infarction with preserved left ventricular systolic function who underwent primary percutaneous coronary intervention, the risk of cardiac death or myocardial infarction was similar in those treated with an angiotensin receptor blocker or ACE inhibitor and lower than in those who received no renin angiotensin system blocker. The association between treatment with an angiotensin receptor blocker and favourable outcomes in terms of cardiac death or myocardial infarction was consistent across various subgroups. We investigated this association between treatment and clinical outcomes using data from a large prospective multicentre registry in Korea.

Results in related to other studies

ACE inhibitors can reduce the risk of mortality in patients with left ventricular systolic dysfunction after acute myocardial infarction.1 2 They have also been reported to be beneficial in low risk patients after myocardial infarction,13 14 although the role of routine long term treatment in low risk patients who have undergone revascularisation after STEMI is less certain. Therefore, the guidelines recommend that ACE inhibitors should be considered in all patients after STEMI in the absence of contraindications.3 4 A substantial portion of patients, however, are intolerant to ACE inhibitors. In the Valsartan in Acute Myocardial Infarction (VALIANT) trial, valsartan was non-inferior to captopril in patients with heart failure or left ventricular systolic dysfunction after acute myocardial infarction.15 Data on the use of angiotensin receptor blocker in patients with preserved left ventricular systolic function after STEMI, however, are lacking. In the ONngoing Telmisartan Alone and in combination with Ramipril Global Endpoint Trial (ONTARGET), telmisartan was equivalent to ramipril in patients with vascular disease or high risk diabetes.7 Although ONTARGET included patients with previous myocardial infarction, patients undergoing primary percutaneous coronary intervention after acute STEMI were not represented. The current guidelines do not cover the use of angiotensin receptor blocker in patients without heart failure or left ventricular systolic dysfunction after STEMI. Therefore, we investigated the association between treatment with an angiotensin receptor blocker and clinical outcomes in STEMI patients with preserved left ventricular systolic function who underwent primary percutaneous coronary intervention. As the number of patients with preserved left ventricular systolic function is much greater than the number with depressed left ventricular systolic function after STEMI,16 the establishment of the role of angiotensin receptor blocker in patients with preserved left ventricular systolic function after STEMI is important.

Strengths and potential limitations of this study

Our study showed that angiotensin receptor blockers had beneficial effects in terms of cardiac death or myocardial infarction, which were comparable with those achieved with ACE inhibitors. There were fewer cardiac deaths or myocardial infarctions in the angiotensin receptor blocker group than in the no renin angiotensin system blocker group. Patients who did not receive a renin angiotensin system blocker, however, were likely to have a higher risk profile at the time of primary percutaneous coronary intervention. These increased risks included post-procedural TIMI flow grade <3, use of vasopressors, and intra-aortic balloon pumps. Therefore, the observed benefit of angiotensin receptor blockers in our study could result from differences in the baseline characteristics between the angiotensin receptor blocker and no renin angiotensin system blocker groups. To deal with this possibility, we performed propensity score matching to adjust for the differences in clinical, angiographic, and procedural characteristics between the groups. After matching, the baseline and procedural characteristics were well balanced between the groups except for use of β blockers at discharge. Furthermore, the results were consistent in all patients and in propensity matched populations. These results are supported by the combined analysis of the Prevention Regimen For Effectively avoiding Second Strokes (PRoFESS) trial and the Telmisartan Randomised AssessmeNt Study in ACE iNtolerant subjects with cardiovascular Disease (TRANSCEND) trial, in which telmisartan reduced the risk of the composite outcome of cardiovascular death, myocardial infarction, or stroke compared with placebo.5 17 Moreover, the observed benefit of treatment with angiotensin receptor blocker in our study and in the TRANSCEND trial is mainly because of a decrease of recurrent myocardial infarction.

In our study, the association between treatment with an angiotensin receptor blocker and better outcome was consistent, and there were no significant interactions between uses of angiotensin receptor blockers at discharge and cardiac death or myocardial infarction across various subgroups. Results were significant in relatively low risk patients without diabetes, Killip class I or II, and single vessel disease. These findings suggest that angiotensin receptor blockers can be effective alternative treatments even in low risk STEMI patients. Similarly, although studied in patients without myocardial infarction setting, a recently published meta-analysis showed that angiotensin receptor blockers represent a valuable option for reducing cardiovascular mortality and morbidity in patients without heart failure.18

Our study has several limitations. Firstly, the study lacks data on the specifics of the renin angiotensin system blocker and doses administered, and we do not know how long the drugs continued to be taken after discharge. Secondly, the non-randomised nature of the registry data could have resulted in selection bias. Although we performed a propensity score matched analysis to adjust for these potential confounding factors, we could not correct for unmeasured variables. In particular, because of the limitations of our database, we did not have information on why physicians prescribed an angiotensin receptor blocker instead of an ACE inhibitor as a first choice treatment. Thirdly, given the observed clinical event rate, this study was considerably underpowered. The lack of a significant difference between the angiotensin receptor blocker and ACE inhibitor group might be because of inadequate sample size. The actual power was only around 50%, and more than 12 000 patients would be needed to achieve a power of 80% for non-inferiority of angiotensin receptor blockers to ACE inhibitors. The low event rate can be attributed to exclusion of deaths in hospital and high rates of use of statins, β blockers, or dual antiplatelet therapy. Although the absolute difference in the rates of cardiac death or myocardial infarction was relatively small between the angiotensin receptor blocker group and the no renin angiotensin system blocker group, the hazard ratio was smaller than 0.5 in both the overall and propensity score matched populations. Large scale prospective randomised controlled trials are needed to clarify the effects of long term treatment with angiotensin receptor blockers in low risk patients with STEMI undergoing primary percutaneous coronary intervention. Fourthly, adverse clinical events were not centrally adjudicated in our registry. All events were identified by the patient’s physician and confirmed by the principal investigator of each hospital. Finally, a median follow-up of 12-months might be too short to conclusively determine the long term efficacy of treatment with angiotensin receptor blockers in the setting of STEMI. Accordingly, the long term prognostic outcomes of the two groups after the index event remain unclear because our median follow-up duration was only about one year.

Conclusions

Use of angiotensin receptor blocker therapy at discharge was associated with improved rates of cardiac death or myocardial infarction in STEMI patients with preserved or slightly reduced left ventricular systolic function compared with the results obtained in patients receiving no renin angiotensin system blocker. Moreover, use of angiotensin receptor blockers at discharge resulted in clinical outcomes comparable with those obtained with the use of ACE inhibitors. Our results suggest that angiotensin receptor blockers are as beneficial as ACE inhibitors in STEMI patients with preserved left ventricular systolic function after primary percutaneous coronary intervention.

What is already known on this topic

Angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors can reduce the risk of mortality in patients with left ventricular systolic dysfunction after acute myocardial infarction

Guidelines recommend that ACE inhibitors should be considered in all patients in the absence of contraindications after ST segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) with heart failure or left ventricular systolic dysfunction

Data on the use of angiotensin receptor blockers, which could be used in patients who are intolerant to ACE inhibitors, are lacking

What this study adds

Risk of cardiac death or myocardial infarction in STEMI patients with preserved left ventricular systolic function is similar in patients treated with angiotensin receptor blockers and ACE inhibitors and lower than in those who receive no renin angiotensin system blocker

The association with favourable outcomes with angiotensin receptor blockers in terms of cardiac death or myocardial infarction was consistent across various subgroups

Angiotensin receptor blockers are as beneficial as ACE inhibitors in STEMI patients with preserved left ventricular systolic function after primary percutaneous coronary intervention

We thank Seonwoo Kim, Keumhee Cho, and Joonghyun Ahn at the Samsung Biomedical Research Institute for their statistical support.

Contributors: All authors contributed to the study design. JHY, J-YH, S-HC, J-HC, SHL, MHJ, DJC, JSP, HSP, and HCG participated in the enrolment of patients, performed the procedures, and contributed to clinical follow-up. JHY, D-JC, and M-HJ participated in data collection. JHY, J-YH, YBS, S-HC, J-HC, and SHL participated in the data analysis. JHY, J-YH, JSP, HSP, and H-CG contributed to data interpretation. JHY and J-YH contributed to writing of the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript. J-YH is guarantor.

Funding: This study was supported by the Korean Society of Cardiology.

Competing interests: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form at www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf and declare: no support from any organisation for the submitted work; no financial relationships with any organisations that might have an interest in the submitted work in the previous three years; no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work.

Ethical approval: This study was approved by the local institutional review board at each hospital (approval No 05-49 of Chonnam National University Hospital).

Transparency statement: The lead authors (JYH and JHY) affirm that this manuscript is an honest, accurate, and transparent account of the study being reported; that no important aspects of the study have been omitted; and that any discrepancies from the study as planned have been explained.

Data sharing: Statistical code is available from the corresponding author.

Cite this as: BMJ 2014;349:g6650

Web Extra. Extra material supplied by the author

Appendix: Supplementary tables A and B

References

- 1.Pfeffer MA, Braunwald E, Moye LA, Basta L, Brown EJ Jr, Cuddy TE, et al. Effect of captopril on mortality and morbidity in patients with left ventricular dysfunction after myocardial infarction. Results of the survival and ventricular enlargement trial. The SAVE Investigators. N Engl J Med 1992;327:669-77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kober L, Torp-Pedersen C, Carlsen JE, Bagger H, Eliasen P, Lyngborg K, et al. A clinical trial of the angiotensin-converting-enzyme inhibitor trandolapril in patients with left ventricular dysfunction after myocardial infarction. Trandolapril Cardiac Evaluation (TRACE) Study Group. N Engl J Med 1995;333:1670-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Task Force on the management of STseamiotESoC, Steg PG, James SK, Atar D, Badano LP, Blomstrom-Lundqvist C, et al. ESC Guidelines for the management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with ST-segment elevation. Eur Heart J 2012;33:2569-619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.O’Gara PT, Kushner FG, Ascheim DD, Casey DE Jr, Chung MK, de Lemos JA, et al. 2013 ACCF/AHA guideline for the management of ST-elevation myocardial infarction: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation 2013;127:e362-425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yusuf S, Teo K, Anderson C, Pogue J, Dyal L, Copland I, et al. Effects of the angiotensin-receptor blocker telmisartan on cardiovascular events in high-risk patients intolerant to angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2008;372:1174-83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McDowell SE, Coleman JJ, Ferner RE. Systematic review and meta-analysis of ethnic differences in risks of adverse reactions to drugs used in cardiovascular medicine. BMJ 2006;332:1177-81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.ONTARGET Investigators, Yusuf S, Teo KK, Pogue J, Dyal L, Copland I, et al. Telmisartan, ramipril, or both in patients at high risk for vascular events. N Engl J Med 2008;358:1547-59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kim HK, Jeong MH, Ahn Y, Kim JH, Chae SC, Kim YJ, et al. Hospital discharge risk score system for the assessment of clinical outcomes in patients with acute myocardial infarction (Korea Acute Myocardial Infarction Registry [KAMIR] score). Am J Cardiol 2011;107:965-71 e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hong YJ, Jeong MH, Ahn Y, Kang JC. The efficacy and safety of drug-eluting stents in patients with acute myocardial infarction: results from Korea Acute Myocardial Infarction (KAMIR). Int J Cardiol 2013;163:1-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kang SH, Suh JW, Yoon CH, Cho MC, Kim YJ, Chae SC, et al. Sex differences in management and mortality of patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction (from the Korean Acute Myocardial Infarction National Registry). Am J Cardiol 2012;109:787-93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lee KH, Jeong MH, Kim HM, Ahn Y, Kim JH, Chae SC, et al. Benefit of early statin therapy in patients with acute myocardial infarction who have extremely low low-density lipoprotein cholesterol. J Am Coll Cardiol 2011;58:1664-71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rubin DB, Thomas N. Combining propensity score matching with additional adjustments for prognostic covariates. J Am Stat Assoc 2000;95:573-85. [Google Scholar]

- 13.GISSI-3: effects of lisinopril and transdermal glyceryl trinitrate singly and together on 6-week mortality and ventricular function after acute myocardial infarction. Gruppo Italiano per lo Studio della Sopravvivenza nell’infarto Miocardico. Lancet 1994;343:1115-22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Collins R, Peto R, Flather M, Parish S, Sleight P, Conway M, et al. Isis-4—a randomized factorial trial assessing early oral captopril, oral mononitrate, and intravenous magnesium-sulfate in 58,050 patients with suspected acute myocardial-infarction. Lancet 1995;345:669-85. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pfeffer MA, McMurray JJ, Velazquez EJ, Rouleau JL, Kober L, Maggioni AP, et al. Valsartan, captopril, or both in myocardial infarction complicated by heart failure, left ventricular dysfunction, or both. N Engl J Med 2003;349:1893-906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Das SR, Alexander KP, Chen AY, Powell-Wiley TM, Diercks DB, Peterson ED, et al. Impact of body weight and extreme obesity on the presentation, treatment, and in-hospital outcomes of 50,149 patients with ST-Segment elevation myocardial infarction results from the NCDR (National Cardiovascular Data Registry). J Am Coll Cardiol 2011;58:2642-50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yusuf S, Diener HC, Sacco RL, Cotton D, Ounpuu S, Lawton WA, et al. Telmisartan to prevent recurrent stroke and cardiovascular events. N Engl J Med 2008;359:1225-37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Savarese G, Costanzo P, Cleland JG, Vassallo E, Ruggiero D, Rosano G, et al. A meta-analysis reporting effects of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and angiotensin receptor blockers in patients without heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol 2013;61:131-42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix: Supplementary tables A and B