Abstract

This study investigated response rates to the Self-Management and Research Technology Project, a 6-week text message program for adolescents with type 1 diabetes designed to provide diabetes self-management reminders and education. The rate of response to texts was high, with 78% of texts responded to during the 6-week period. Girls and participants who self-reported sending a large number of personal daily texts had higher response rates; other demographic and medical variables were unrelated to text response rates. Inclusion of mobile health technologies such as text messages in clinical care may be a unique, relevant method of intervention for youths with type 1 diabetes, regardless of age, socioeconomic status, or glycemic control.

Type 1 diabetes is a lifelong condition usually diagnosed in childhood and affecting 1 in 400 children < 20 years of age.1 Its management requires daily blood glucose monitoring, insulin administration, carbohydrate counting, and physical activity monitoring. Many adolescents experience a decline in glycemic control; recent studies have shown that only 14% of adolescents with type 1 diabetes meet the American Diabetes Association’s glycemic control recommendations.2,3 Furthermore, the novelty and utility of behavioral interventions delivered in person have often plateaued by adolescence.4,5

Mobile technology may offer a particularly useful way to deliver health information to adolescents. Indeed, 77% of adolescents own a mobile phone, 63% communicate via text messages daily, and adolescents are amenable to receiving health information via text messages.6,7 A recent review of the literature regarding text message interventions for youths with type 1 diabetes indicated that texting to teens with diabetes is feasible and can be enjoyable to youths;8 however, the text message programs had limitations: many did not require participants to respond, did not allow researchers to monitor text message receipt, provided access to a cell phone as an incentive, and included non–text message intervention components. Further systematic analysis of the feasibility of text message programs for adolescents with type 1 diabetes is warranted.

The project reported here is a pilot study designed to investigate whether adolescents will use a type 1 diabetes text message program (the Self-Management and Research Technology [SMART] Project) and to determine whether there are groups of adolescents who are more likely to respond to type 1 diabetes texts. Unique to the SMART Project is that adolescents choose specific times to receive texts that are convenient to their schedule, and researchers can monitor responses. The primary aim of this study is to describe recruitment, retention rates, and response rates to SMART Project text messages. We hypothesized that participants’ response rates would decrease over the course of the 6-week program. The second aim of this study was to explore demographic and medical variables associated with response rates. Based on previous research, we hypothesized that older, female participants who have better glycemic control would respond to a higher percentage of SMART Project text messages.

Methods

Study participants

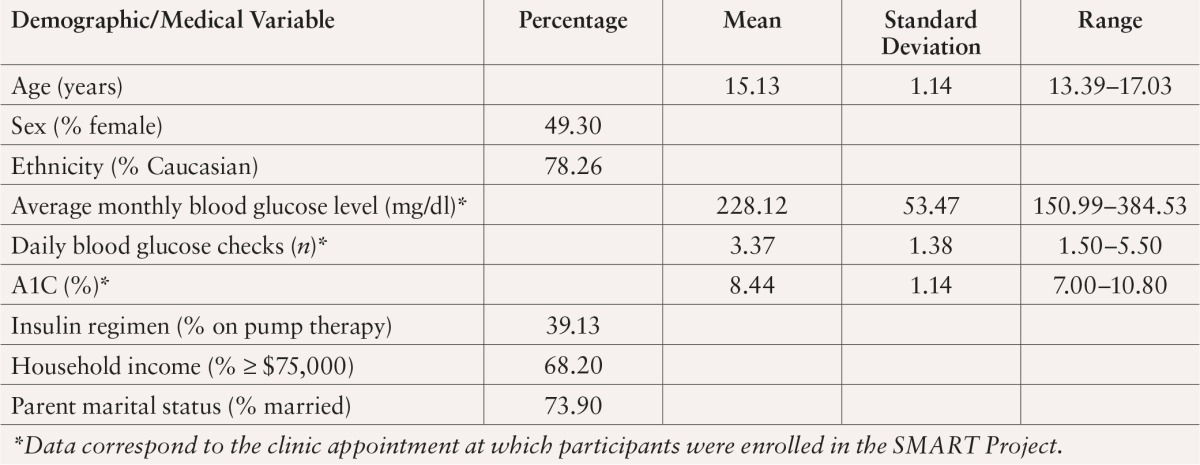

SMART Project study participants included 23 adolescents, aged 13–17 years, who had been diagnosed with type 1 diabetes for at least 1 year and who were followed by the endocrinology department at a Mid-Atlantic children’s hospital (Table 1). Participants were excluded if they were not on a basal-bolus insulin regimen (via multiple daily injections or insulin pump), did not have a cell phone with an unlimited text message plan, were diagnosed with severe psychopathology and/or developmental/physical disabilities, were not fluent in English, or did not have parental consent.

Table 1.

Demographic and Medical Information (n = 23)

Study procedure

Identification of eligible participants was conducted by reviewing clinic lists. Patients who met initial SMART Project eligibility criteria were mailed recruitment letters and a postcard that could be returned if they did not wish to be contacted. Patients were contacted by phone 1 week later to assess their eligibility and complete verbal consent.

Patients who provided consent attended an orientation to the SMART Project during a regularly scheduled clinic appointment. Informed assent and parental consent were obtained, participants were oriented to the SMART Project, and adolescents completed a demographics and medical history questionnaire. Participants were registered in the SMART Project program, a two-way text message software program contracted through Reify Health of Baltimore, Md., and the timing of texts was customized according to their schedules. Participants were instructed to choose morning (before school), afternoon (after school), evening (before bed), and weekend mid-morning times. Glucose meters were downloaded, and medical charts were reviewed for A1C results. Participants were compensated with a $25 gift card.

Subsequently, participants received text messages for 6 weeks. During Week 1, participants were prompted to text their blood glucose levels three times per day (morning, afternoon, and evening). During Weeks 2–5, they received text messages 2 times per day (morning and either afternoon or evening) regarding topics related to type 1 diabetes, including blood glucose monitoring (Week 2), nutrition (Week 3), physical activity (Week 4), and sleep/mood (Week 5). Texts included two parts: type 1 diabetes–related information and tips and a request to respond to a specific question. During Week 6, participants again were prompted to text their blood glucose levels three times per day. Participants received a confirmation text for all texts they sent. Immediately after completion of the 6-week program, participants completed follow-up questionnaires.

Study measures

Sociodemographic and medical questionnaires.

Participants reported their age, sex, race/ethnicity, family income, parents’ marital status, and insulin regimen using the Demographics—General Information and Medical Information questionnaires.

Glycemic control.

A1C was calculated for each participant at the clinic appointment that was closest in time to their orientation to the SMART Project and recorded by a research team member. Thus, all A1C values reflected adolescents’ glycemic control during the months immediately before participation started. All assays were conducted with a DCA 2000+ analyzer (Siemens/Bayer, Munich, Germany), a point-of-care type 1 diabetes management platform that performs an A1C test in minutes.9

Blood glucose data.

Participants’ glucose meters were downloaded at the clinical appointment during which they were oriented to the SMART Project to obtain blood glucose data from the 30 days before their enrollment. These data were used to calculate their number of daily blood glucose checks and average daily blood glucose level.

Cell phone use.

A four-item questionnaire was developed by our team to assess adolescents’ cell phone use. Participants reported how many days per week they used their cell phone to text, how many texts they sent per day, how many days per week they talked on their cell phone, and how many hours they talk on the phone per day.

Text message data.

Participants’ responses to SMART Project text messages were collected via the Reify Health software program, and the time and verbatim text of text messages were downloaded. From these data, response rates and response latency were calculated. Overall and weekly response rates were calculated as the percentage of texts to which an adolescent responded. For Weeks 1 and 6, adolescents were supposed to text their blood glucose levels three times per day (morning, afternoon, and evening); thus, the denominator in the Week 1 and Week 6 equations was 21 (3 times per day × 7 days). For Weeks 2–5, adolescents were supposed to respond to two texts per day (morning and either afternoon or evening); thus, the denominator in the equations for Weeks 2–5 was 14 (2 times per day × 7 days). Finally, the denominator for the overall Week 1–Week 6 response rate was 98 (the sum of texts they were asked to send each week). Response latency was calculated as the number of minutes before the adolescent responded.

Data analysis

All statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS 20th ed. (International Business Machines, Armonk, N.Y.). Descriptive statistics were generated to assess adolescents’ demographic and medical characteristics and their SMART Project text message response rate and latency by week and time of day. Correlational analyses were conducted to determine whether adolescents’ demographic and medical characteristics were related to their text message response rates.

Study Results

Aim 1: Adolescent recruitment/retention and SMART Project response patterns

Recruitment letters were mailed to 97 patients initially identified as eligible through screening. Fifty-five percent were reached by phone by a research assistant to discuss the project and assess their eligibility. Seventeen patients declined to participate, 10 were ineligible, and three verbally consented but did not complete an orientation session. Thus, 23 adolescents (54% of eligible participants) consented and were enrolled in the SMART Project. Retention was high; 96% of participants responded to texts throughout the 6 weeks of the SMART Project and completed follow-up data collection.

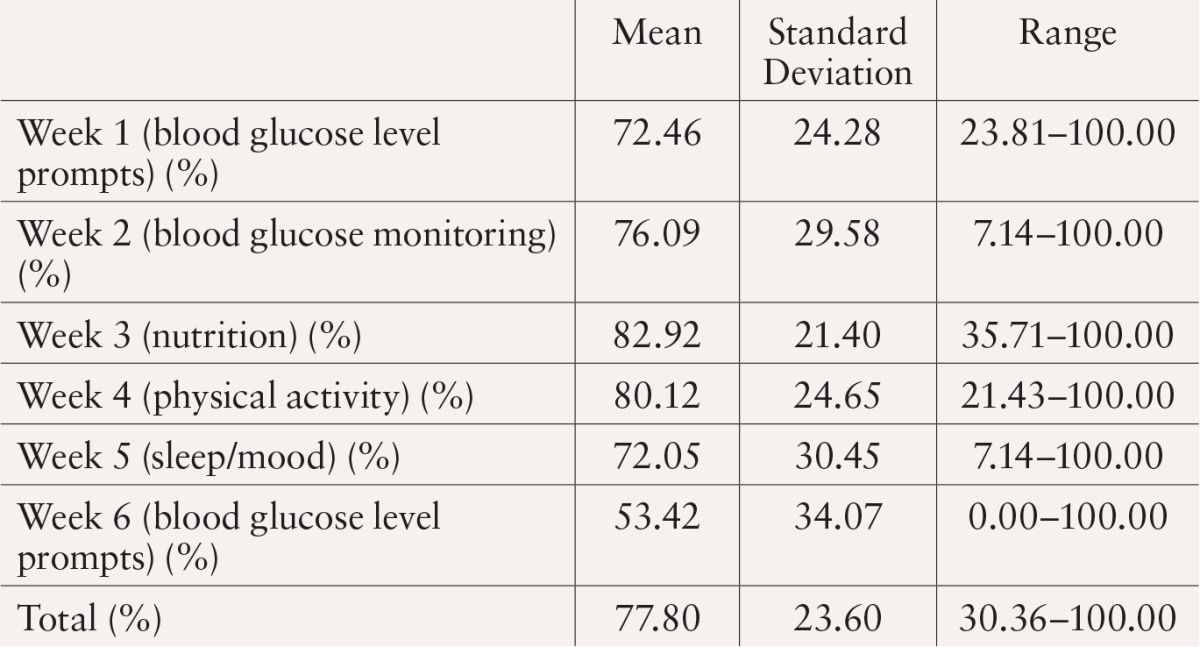

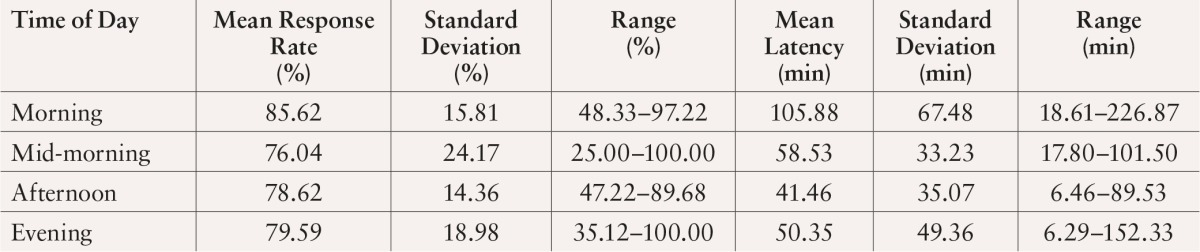

Participants responded to 78% of texts with some variability based on week (Table 2). Participants responded to the most texts during Week 3 (83%; nutrition texts) and to the least texts during Week 6 (53%; assessment phase 2; blood glucose prompt texts). Text message response rates and latencies were examined for a small, randomly selected subset of participants according to time of day (n = 8) (Table 3). Regardless of time, adolescents responded to the majority of texts (≥ 76%). Mean response latency was 64 minutes (standard deviation 148, range 6–227). Response latency was not related to response rate, regardless of time of day (P > 0.05). For example, adolescents responded to 86% of morning texts, despite the fact that it took them longer to respond to morning texts (106 minutes) than to afternoon, evening, or weekend mid-morning texts.

Table 2.

Percentage of Text Messages to Which Participants Responded by Week (n = 23)

Table 3.

Text Message Response Rates and Latency According to Time of Day (n = 8)

Aim 2: Medical/demographic characteristics related to text message response rate

To assess how demographic variables (age, sex, ethnicity, family income, and parent marital status) and medical variables (average monthly blood glucose level, number of daily blood glucose checks, A1C, and insulin regimen) were related to overall text response rates, a series of correlational analyses were conducted. There was a significant correlation between adolescents’ sex and overall text response rate (r = 0.41, P < 0.05); females responded to more SMART Project texts than males. Similarly, there was a significant positive correlation between the self-reported number of personal texts adolescents sent per day and the text response rate (r = 0.82, P < 0.001); adolescents who sent more personal texts per day responded to a greater number of SMART Project texts. There was also a trend for adolescents who had a lower mean monthly blood glucose level to respond to more texts (r = –0.39, P = 0.08). No other demographic or medical variables were related to text response rate.

Discussion

More than half of eligible participants were interested in and completed all 6 weeks of the SMART Project. Adolescents responded to the majority of texts within 1–2 hours, although there was some variability in response rate according to the week and in response latency according to the time of day. Adolescents responded to type 1 diabetes information and tips more than blood glucose check prompts. Specifically, adolescents responded to more texts about nutrition and physical activity than to other topics; these may be areas of particular interest for adolescents with type 1 diabetes. Adolescents also tended to respond to SMART Project texts regardless of the time of day, although it took them longer to respond to morning texts than to afternoon and evening texts. Mornings are likely to be particularly busy for adolescents as they prepare for school, so tasks such as checking type 1 diabetes–related texts are less of a priority.

Three groups of adolescents were most likely to respond to SMART Project texts: girls, adolescents who self-reported that they send a large number of daily personal texts, and adolescents with lower monthly mean blood glucose levels. That girls responded to more texts is consistent with other research documenting that girls text more than boys.6 It also makes intuitive sense that adolescents who text more and have lower blood glucose levels (i.e., who may be more adherent to their regimen) are more inclined to respond to type 1 diabetes–related texts. Future type 1 diabetes text message projects with adolescents may expect comparable results. However, it was equally notable that response rates were not related to age, ethnicity, family income, or insulin regimen; adolescents from diverse backgrounds can benefit from programs similar to the SMART Project.

There are several notable strengths of this study, including our ability to calibrate the timing of text messages to fit adolescents’ schedules and to monitor text responses. We ensured that adolescents received texts at an optimal time and calculated response rates and latencies, which have not been options in previous text message programs for youths with type 1 diabetes. We also did not include access to a cell phone as an incentive. Thus, we can confidently say that adolescents responded to SMART Project texts because they wanted to respond, not because they had to respond to use a cell phone. We also experienced minimal technical difficulties as a result of several weeks of beta testing before participant enrollment.

There are, however, study limitations that should be addressed in future research. The SMART Project had a small sample size, was conducted over a period of only 6 weeks, and provided type 1 diabetes content that varied by week rather than within each week. Some adolescents reported that they wanted to receive texts with a variety of type 1 diabetes topics throughout each week, instead of focusing on only one topic per week. Greater variety may have increased the novelty of the SMART Project and concomitant response rates.

These results contribute to a growing body of literature regarding the use of text message interventions for adolescents with type 1 diabetes. A recent review of the literature identified seven published studies that included text messages as a means of improving adolescents’ knowledge about type 1 diabetes and adherence to their treatment regimen.8 Some of these interventions focused only on blood glucose monitoring10,11 and sent all participants the same information,12,13 but there is a trend for the development of increasingly personalized text message programs that include two-way communication between participants and medical providers. For example, both Franklin et al.14 and Mulvaney et al.15 reported on text message programs that included the development of personal type 1 diabetes profiles and goals for each participant during clinic appointments, which were then used to select appropriate texts. Hanauer et al.10 included the medical team in their program, such that adolescents received health care recommendations by text if the blood glucose level they submitted was out of range. Although these programs are more time-intensive to develop and coordinate and require the participation of additional medical team members, preliminary A1C results and participant satisfaction indicate that these efforts may have a positive impact on outcomes.

Future studies should be developed with the goal of increasing engagement among boys and adolescents who have higher average blood glucose levels. Hingle et al.7 reported that adolescents enjoy responding to text quizzes; thus, including a game component may be a method to encourage participation. This may take the form of a competitive, social component (either text-based or smartphone application–based) composed of text quizzes and weekly game “leaders” (i.e., the usernames of adolescents who respond the most or answer the most questions correctly). The study by Hingle et al. also revealed that adolescents prefer health text message programs that include some nonhealth information.7 Adolescents who have worse glycemic control and are less inclined to participate in a type 1 diabetes–related program may be encouraged to participate if the program includes nonhealth texts or fun facts (i.e., trivia).

Additional suggestions for future programs are the development and evaluation of the inclusion of a parent component and the possibility of integrating the SMART Project into clinical care. Although parents did not receive text messages in the current study, parents of participants provided feedback that they wanted to receive educational type 1 diabetes texts as well. Others mentioned that they would appreciate type 1 diabetes clinic appointment and/or prescription reminders via text message. Additionally, the SMART Project did not provide adolescents with feedback regarding their responses. Engagement and response rates may increase if a health care provider is available to review responses and provide real-time feedback (e.g., respond to high or low blood glucose levels with reminders about hyper- and hypoglycemia management). Finally, it will be important to determine whether SMART Project texts changed patients’ type 1 diabetes–related behavior.

Collectively, these results document the feasibility of a text message program for youths with type 1 diabetes. Adolescents who were interested in receiving type 1 diabetes–related text messages actively engaged with the program for an extended period of time. Although girls were more likely to respond to texts, most adolescents, regardless of other demographic and medical characteristics, responded to SMART Project texts. Mobile health technologies such as text messages may be a particularly relevant method of intervention for youths with type 1 diabetes.

References

- 1.American Diabetes Association: Diabetes statistics. Available from http://www.diabetes.org/diabetes-basics/diabetes-statistics. Accessed 11 March 2013

- 2.Hood K, Peterson C, Rohan J, Drotar D: Association between adherence and glycemic control in pediatric type 1 diabetes: a meta-analysis. Pediatrics 124:e1171–e1179, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Luyckx K, Seiffge-Krenke I: Continuity and change in glycemic control trajectories from adolescence to emerging adulthood: relationships with family climate and self-concept in type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Care 32:797–801, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ellis DA, Templin T, Frey MA, Cunningham P, Naar-King S, Cakan N: Use of multisystemic therapy to improve regimen adherence among adolescents with type 1 diabetes in chronic poor metabolic control: a randomized trial. Diabetes Care 28:1604–1610, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wysocki T, Harris M, Buckloh L, Mertlich D, Lochrie A, Taylor A, Sadler M, Mauras N, White NH: Effects of behavioral family system therapy for diabetes on adolescents’ family relationships, treatment adherence, and metabolic control. J Pediatr Psychol 31:928–938, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lenhart A, Teens, smartphones & texting. Available from http://pewinternet.org/Reports/2012/Teens-and-smartphones.aspx. Accessed 19 May 2013

- 7.Hingle M, Nichter M, Medeiros M, Grace S: Texting for health: the use of participatory methods to develop healthy lifestyle messages for teens. J Nutr Educ Behav 45:12–19, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Herbert L, Owen V, Pascarella L, Streisand R: Text message interventions for children and adolescents with type 1 diabetes: a systematic review. Diabetes Technol Ther 15:362–370, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Diabetes Research in Children Network (DirecNet) Study Group: A randomized multicenter trial comparing the GlucoWatch Biographer with standard glucose monitoring in children with type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Care 28:1101–1106, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hanauer DA, Wentzell K, Laffel N, Laffel LM: Computerized Automated Reminder Diabetes System (CARDS): Email and SMS cell phone text messaging reminders to support diabetes management. Diabetes Technol Ther 11:99–106, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rami B, Popow C, Horn W, Waldhoer T, Schober E: Telemedical support to improve glycemic control in adolescents with type 1 diabetes mellitus. Eur J Pediatr 165:701–705, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Newton KH, Wiltshire EJ, Elley CR: Pedometers and text messaging to increase physical activity: randomized controlled trial of adolescents with type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Care 32:813–815, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wangberg SC, Arsand E, Andersson N: Diabetes education via mobile text messaging. J Telemed Telecare 12 (Suppl. 1):55–56, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Franklin VL, Waller A, Pagliari C, Greene SA: A randomized controlled trial of Sweet Talk, a text-messaging system to support young people with diabetes. Diabet Med 23:1332–1338, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mulvaney SA, Anders S, Smith AK, Pittel EJ, Johnson KB: A pilot test of a tailored mobile and web-based diabetes messaging system for adolescents. J Telemed Telecare 18:115–118, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]