Abstract

Background

Pain is frequent and distressing in people with dementia, but no randomized controlled trials have evaluated the effect of analgesic treatment on pain intensity as a key outcome.

Methods

Three hundred fifty-two people with dementia and significant agitation from 60 nursing home units were included in this study. These units, representing 18 nursing homes in western Norway, were randomized to a stepwise protocol of treating pain (SPTP) or usual care. The SPTP group received acetaminophen, morphine, buprenorphine transdermal patch and pregabalin for 8 weeks, with a 4-week washout period. Medications were governed by the SPTP and each participant's existing prescriptions. We obtained pain intensity scores from 327 patients (intervention n = 164, control n = 163) at five time points assessed by the primary outcome measure, Mobilization-Observation-Behaviour-Intensity-Dementia-2 (MOBID-2) Pain Scale. The secondary outcome was activities of daily living (ADL). We used a linear intercept mixed model in a two-way repeated measures configuration to assess change over time and between groups.

Results

The SPTP conferred significant benefit in MOBID-2 scores compared with the control group [average treatment effect (ATE) −1.388; p < 0.001] at week 8, and MOBID-2 scores worsened during the washout period (ATE = −0.701; p = 0.022). Examining different analgesic treatments, benefit was conferred to patients receiving acetaminophen compared with the controls at week 2 (ATE = −0.663; p = 0.010), continuing to increase until week 8 (ATE = −1.297; p < 0.001). Although there were no overall improvements in ADL, an increase was seen in the group receiving acetaminophen (ATE = +1.0; p = 0.022).

Conclusion

Pain medication significantly improved pain in the intervention group, with indications that acetaminophen also improved ADL function.

What's already known about this topic?

Many people with dementia experience pain regularly, but are not able to communicate this to their carers or physicians due to the limited self-report capacity inherent in the symptomatology of dementia.

Few studies have investigated the direct effect of pain treatment on pain intensity in patients suffering from dementia, with previous studies using proxy measures of behavioural symptoms.

What does this study add?

A stepwise protocol to treat pain in nursing home residents with moderate to severe dementia significantly reduced pain intensity.

Pain treatment by acetaminophen improved activities of daily living.

There is an urgent need for a standardized approach to assessment and treatment of pain for nursing home residents with dementia.

1. Introduction

Dementia affects approximately 10 million people in Europe, and this is expected to double every 20 years as the population ages (Kalaria et al., 2014). One-third of people with dementia reside in nursing homes (NHs). In addition to the distress experienced by these individuals as a result of their condition, many also experience pain (Achterberg et al., 2007). The precise prevalence of pain is unclear, but estimates indicate that up to 80% of NH patients are in acute or chronic pain (Husebo et al., 2008; Achterberg et al., 2010, 2013). The majority experience persistent pain lasting 6 months or longer (Pickering et al., 2006). The most common types of pain are musculoskeletal, such as arthritis, or neuropathic pain as result of diabetes or stroke (Scherder and Plooij, 2012). Despite the high prevalence of pain in these individuals, assessment is difficult due to the loss of cognitive and communicative abilities.

Pain is distressing for the individual who experiences it and often correlates with key symptoms, ranging from problems with coordination and memory to changes in personality and behaviour. This can also lead to an increased risk of falls (Deandrea et al., 2010; Huang et al., 2012), behavioural and psychological symptoms of dementia (BPSD) such as agitation and aggression (Hurley et al., 1992; Lin et al., 2011; Ahn and Horgas, 2013; Husebo et al., 2013), and depression (Cohen-Mansfield and Taylor, 1998). In addition, undertreated pain affects social interaction, provokes sleep disturbances and reduces quality of life (Giron et al., 2002; Cipher and Clifford, 2004; Cordner et al., 2010). Furthermore, people experiencing BPSD due to pain may be inappropriately prescribed anti-psychotic medication, which can be harmful, rather than analgesia (Corbett et al., 2012a,b).

A limitation in the existing literature is the lack of large randomized controlled trial (RCT) studies with pain intensity as the main outcome (Corbett et al., 2012a,b). To date, no large-scale pain intervention studies have focused upon improvement of pain intensity as a key outcome (Lorenz et al., 2008). Most studies, including four RCTs, have utilized measures of BPSD, mood or activities of daily living (ADL) as proxy measures of pain (Manfredi et al., 2003; Buffum et al., 2004; Chibnall et al., 2005; Kovach et al., 2006). All RCTs were performed in the NH setting and with aged patients investigating the effect of pain medication on agitation. However, none of these trials included a measure of pain or a systematic pain management protocol.

The absence of data regarding the impact of pain intensity is, in part, due to the challenge of accurately identifying pain robustly. We recently developed and tested the Mobilization-Observation-Behaviour-Intensity-Dementia-2 (MOBID-2) Pain Scale for use in NH patients with dementia (Husebo et al., 2010). This article reports secondary analyses of an 8-week RCT with follow-up assessment after a 4-week washout period to investigate the effect of pain treatment on pain intensity in NH patients with dementia, assessed by the MOBID-2 Pain Scale.

2. Methods

The trial is registered at ClinicalTrials.gov (number NCT01021696) and at the Norwegian Medicines Agency (EudraCT nr: 2008-007490-20). Ethical approval was obtained in accordance with local law, by the Regional Committee for Medical Ethics, Western Norway (REK-Vest 248.08) and by the authorized Institutional Review Board of each participating institution.

2.1 Study design

This study was an 8-week RCT comparing the effect of the stepwise protocol of treating pain (SPTP) intervention with control in people with dementia living in Norwegian NHs. The trial included a 4-week washout period with additional follow-up at 12 weeks. The recruitment strategy of 18 NHs, patient samples and full study design has been described in our previous publication (Husebo et al., 2011).

2.2 Eligibility criteria

Participants included in this study were people aged 65 years and older residing in a NH for at least 4 weeks. Inclusion criteria were a diagnosis of Alzheimer's disease or other dementias according to Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, a Functional Assessment Staging score >4 (Reisberg et al., 1982) and clinically relevant behavioural disturbances defined as Cohen Mansfield Agitation Inventory score ≥39 (i.e., at least 1-week history of clinically significant agitation) (Cohen-Mansfield et al., 1989; Finkel et al., 1992). Only patients with moderate or severe dementia, defined as a score of <20 on the Mini-Mental State Examination scale (MMSE) (range 0–30), were included (Folstein et al., 1975). Residents were included independent of painful diagnoses, presumed pain or ongoing pain treatment. Residents were excluded if they had an expected survival of less than 6 months, severe psychosis or allergy to any of the study drugs. Written informed consent included a description of the study design, benefit and possible side effects of the trial. We took into consideration that even individuals with mild cognitive impairment might have impaired capacity to consent to research (Warner and Nomani, 2008; Ayalon, 2009) and obtained informed consent from all patients and all surrogates/caregivers or the authorized legal representatives. Caregivers also gave consent to participate as informants.

2.3 Intervention

The SPTP followed the latest recommendations of the American Geriatric Society (AGS) Panel for pharmacological management of persistent pain in older adults (AGS Panel on Persistent Pain in Older Persons, 2009) and is described in our previous publication (Husebo et al., 2011). All patients assigned to the treatment group were investigated individually by the responsible team, which consisted of the NH physician, the patient's primary caregiver, a pain therapist (B.S.H.) and a research assistant (R.K.S.). After a thorough discussion, the team agreed on the most appropriate pain medication and dosage according to the standardized SPTP protocol. Depending upon their existing prescribed pain treatment, patients received titrated analgesia in a stepped approach. Patients previously receiving no or low dose of acetaminophen received acetaminophen orally (3 g/day) (step 1). If they already had a prescription of acetaminophen, they were adjusted to either extended release morphine orally (10 or 20 mg/day) (step 2) or buprenorphine transdermal patch (5 μg or 10 μg/h for 7 days) (step 3). If patients were already receiving step 3 medications and had neuropathic pain, they received pregabalin orally (25, 50 or 75 mg/day) (step 4), using a fixed dose regime throughout the 8-week treatment period. Most cases at steps 2–4 received combination therapy with different analgesics. Patients with swallowing difficulties started at step 3. Medication was offered at breakfast, lunch and dinner (approximately 08:00, 13:00 and 18:00 h), respectively. In patients who were not able to tolerate this treatment, the dosage was reduced or the patient was withdrawn from the study and treated as clinically appropriate. The treating physicians were instructed to keep prescriptions and doses of analgesics unchanged in the control group.

2.4 Outcome measures

Outcome measures were completed at baseline, 2, 4, 8 and 12 weeks. The MOBID-2 Pain Scale was used to assess pain intensity in the participants. MOBID-2 is a two-part staff-administered observational pain behaviour instrument, developed and tested in NH patients with advanced dementia (Husebo et al., 2010). Assessment of pain intensity is based upon the patient's immediate pain behaviour such as vocalization, facial expression and use of defensive body positions. MOBID-2 part 1 assesses pain related to the musculoskeletal system in connection with standardized, guided movements during morning care (five items). MOBID-2 part 2 assesses pain that might originate from internal organs, head and skin and is monitored over time (five items). After registration of pain behaviour, observations are inferred to pain intensity using a 10-point numerical rating scale (NRS). Caregivers are encouraged to judge whether the observed behaviour is related to pain or to dementia and psychiatric disorders. Finally, an independent overall pain intensity score is completed, again using a NRS. Previous studies on the psychometric properties of MOBID and MOBID-2 pain scale have showed that the inter- and intra-rater and test–retest reliability of the scale is very good to excellent, with Intra Class Correlations ranging from 0.80 to 0.94 and from 0.60 to 0.94, respectively (Husebo et al., 2007, 2009, 2010). Internal consistency was highly satisfactory with Cronbach's α ranging from 0.82 to 0.84. Face, construct and concurrent validity was good and it has shown good feasibility in clinical practice (Husebo et al., 2007, 2009). Indications were provided that MOBID-2 is responsive to a decrease in pain intensity after pain treatment (Husebo et al., 2014).

An additional outcome measure was physical function assessed with the Barthel ADL index (range 0–20), in which higher values indicate higher levels of activities of daily functioning and independence (Mahoney and Barthel, 1965). Safety and tolerability were monitored at each assessment, and all adverse events and vital signs were recorded.

2.5 Randomization and blinding

Randomization was executed using Stata version 8 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA). To eliminate selection bias at institution level, we defined a cluster as a single independent NH unit (with no crossover of staff), and randomized these units. Thus, patients in each cluster were randomly assigned to receive SPTP in the intervention group or continue with treatment as usual (control group), using a computer-generated list of random numbers for allocation of the clusters by the study statistician. During enrolment, two trained research assistants interviewed the patients' primary caregivers. The outcome measures and drug prescriptions were reviewed by a consultant for old age psychiatry (D.A.), an anaesthetist and pain therapist (B.S.H.), one of the research assistants (R.S.) and a senior member of staff, usually a general practitioner from the NH after completion of the enrolment process and prior to randomization. Researchers and nurses with responsibility for carrying out the intervention did not participate in data collection. Research assistants and staff members who collected the data were blinded to group allocation and type of intervention during the study period. The staff were instructed not to discuss management procedures.

2.6 Data analysis

The mean, standard deviation (SD) and range were calculated for participant demographics. We described the groups at baseline with two-sample independent t-tests for normally distributed continuous variables, chi-square test for categorical variables and Mann–Whitney test for continuous variables with non-normal distribution. Differences in mean and standard error (SE) of the mean MOBID-2 Pain Scale and ADL scores over time between treatment groups were estimated with linear random intercept quantile mixed-effect models. Mixed model regression modelled with linear random intercept permits multiple measurements per person over time, irregular intervals between measurements and allows for incomplete data on assumption that data are missing at random (Verbeke and Molenberghs, 2000). We included the NH units as a nestling level in our analysis. Statistical analyses were conducted with IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows version 21.0 (IBM Corp, Armonk, NY, USA) and R version 3.0.0 (The R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria) and package nlme-3.1-109.

3. Results

3.1 Cohort characteristics

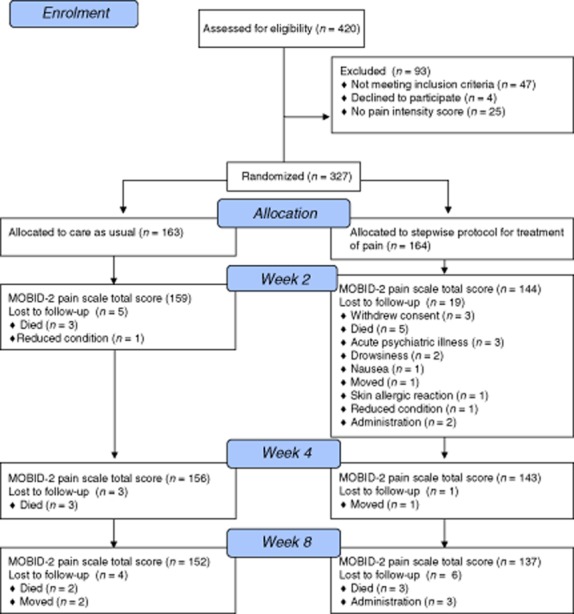

Four hundred twenty eligible patients were identified, of whom 352 were included and cluster randomized to control (n = 177, cluster n = 27) or intervention groups (n = 175, cluster n = 33). In total, 327 participants had a MOBID-2 pain score at baseline and were included in this stepwise protocol of treating pain analyses (control n = 163, intervention n = 164). Dropout rate was equally distributed between groups. The detailed flow of participants through this study is summarized in Fig. 1. Demographic data for the cohort are presented in Table 1. No differences were found between the groups at baseline.

Fig 1.

Flow chart showing patients flow through the 12-week study period including control and intervention groups.

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of the study population. Variables reported as mean (SD), medians (SE) and proportions (%)

| Characteristic | Control mean (SD) n = 163 | Intervention mean (SD) n = 164 | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Agea | 86.4 (6.7) | 85.2 (7.0) | 0.102 |

| Women (%)b | 131 (74.0) | 131 (74.9) | 0.856 |

| MMSEc,d | 8.9 (6.6) | 7.6 (6.6) | 0.065 |

| Barthel ADL indexc,e | 8.7 (5.5) | 7.8 (5.6) | 0.148 |

| MOBID-2 Pain Scalec,f | 3.7 (2.5) | 3.8 (2.7) | 0.988 |

| MOBID-2 Pain Scale ≥ 1c | 4.2 (2.2) | 4.5 (2.4) | 0.273 |

| MOBID-2 Pain Scale ≥ 2c | 4.5 (2.1) | 4.9 (2.2) | 0.213 |

| MOBID-2 Pain Scale ≥ 3c | 5.3 (1.8) | 5.4 (2.0) | 0.830 |

| No pain diagnoses in total (%)c | 29.4 | 29.4 | 0.823 |

| 1 pain diagnoses (%) | 30.8 | 30.3 | |

| 2 pain diagnoses (%) | 24.4 | 22.6 | |

| ≥3 pain diagnoses (%) | 16.0 | 18.1 | |

| Old fracture (%)b | 27.6 | 27.1 | 0.801 |

| Arthritis (%)b | 22.4 | 20.0 | 0.600 |

| Osteoporosis (%)b | 20.5 | 23.9 | 0.477 |

| Heart (%)b | 17.9 | 15.5 | 0.561 |

| Cancer (%)b | 16.7 | 20.0 | 0.448 |

| Neuropathy (%)b | 1.9 | 4.5 | 0.196 |

| Wound gangrene (%)b | 1.3 | 3.9 | 0.150 |

| Muscle spasm (%)b | 1.3 | 2.6 | 0.406 |

MMSE, Mini-Mental State Examination (scores from 0 to 30); ADL, activities of daily living (scores 0–20); MOBID-2, Mobilisation-Observation-Behaviour-Intensity-Dementia-2 Pain Scale.

t-Test for continuous variable, normally distributed.

Chi-square test for dichotomous categorical variables.

Mann–Whitney U for unequal distributed continuous variable given in medians (SE). Variables reported as mean (SD) and median (%) if not indicated otherwise.

Lower scores indicate more cognitive impairment.

Higher scores indicate better function.

Higher scores indicate more pain (scores ≥ 3 accepted as clinically relevant).

Pain diagnoses and intensity were distributed equally between control and intervention groups at baseline. Over 70% of participants had one or more diagnoses of pain (Table 1). Inferred pain intensity greater than zero was observed in over 80% of the patients (n = 282), and intensity of 3 or higher was seen in over 60% (n = 203). MOBID-2 part 1 assessment indicated that the majority of pain resulted from guided movements of the legs and from turning over in bed. MOBID-2 part 2 showed the most frequently affected sites were the pelvis/genital organs and skin (Table 2). We found no differences in pain intensity between groups with different levels of dementia assessed by MMSE (p = 0.196). Participants who were assumed to have neuropathic pain and were treated with pregabalin had significantly higher pain scores than controls and the other treatment groups at baseline (MOBID-2 pain score 6.1; p = 0.001). Pain intensity did not differ between the other groups at baseline: control group (MOBID-2 pain score 3.65), acetaminophen group (mean 3.53; p = 0.674) and morphine group (extended release morphine and buprenorphine) (mean 3.97; p = 0.469).

Table 2.

Efficacy of treating pain on different locations of pain with the sum scores of musculoskeletal pain (MOBID-2 part 1) and pain from internal organs head and skin (MOBID-2 part 2) between control group and treatment group at baseline and in week 8 (n = 327)

| Pain location | Control (n = 163) | Intervention (n = 164) | dfa | ta | pa | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline mean (SE) | Week 8 mean (SE) | Difference | Baseline mean (SE) | Week 8 mean (SE) | Difference | ||||

| Hands | 0.8 (0.2) | 1.0 (0.1) | 0.161 | 1.1 (0.2) | 0.8 (0.2) | −0.243 | 1183 | −2.457 | 0.014 |

| Arms | 1.7 (0.2) | 1.8 (0.2) | 0.119 | 1.8 (0.2) | 1.2 (0.2) | −0.677 | 1180 | −2.868 | 0.004 |

| Legs | 2.6 (0.2) | 2.2 (0.2) | −0.342 | 2.0 (0.2) | 1.6 (0.2) | −0.375 | 1174 | −0.177 | 0.859 |

| Turn over | 1.9 (0.2) | 2.0 (0.2) | 0.026 | 2.0 (0.2) | 1.3 (0.2) | −0.739 | 1156 | −2.665 | 0.008 |

| Sit | 1.6 (0.2) | 2.0 (0.2) | 0.398 | 2.1 (0.2) | 1.2 (0.2) | −0.826 | 1154 | −4.498 | <0.001 |

| Part 1 total score | 8.7 (0.8) | 8.9 (0.7) | 0.393 | 9.0 (0.8) | 5.8 (0.8) | −3.233 | 1132 | −3.567 | <0.001 |

| Head, mouth, neck | 1.0 (0.1) | 0.9 (0.1) | −0.091 | 1.4 (0.2) | 0.8 (0.1) | −0.627 | 1184 | −2.548 | 0.011 |

| Heart, lung, chest | 0.8 (0.2) | 0.8 (0.1) | 0.049 | 0.8 (0.1) | 0.4 (0.1) | −0.426 | 1182 | −2.675 | 0.008 |

| Abdomen | 0.9 (0.1) | 0.7 (0.1) | −0.143 | 1.0 (0.2) | 0.4 (0.1) | −0.546 | 1182 | −1.823 | 0.069 |

| Pelvis, genital organs | 1.6 (0.2) | 1.6 (0.2) | −0.023 | 1.8 (0.2) | 0.8 (0.2) | −0.944 | 1182 | −3.276 | 0.001 |

| Skin | 1.7 (0.2) | 1.4 (0.2) | −0.208 | 1.5 (0.2) | 1.0 (0.2) | −0.570 | 1184 | −1.458 | 0.145 |

| Part 2 total score | 5.9 (0.5) | 5.4 (0.4) | −0.416 | 6.5 (0.5) | 3.4 (0.4) | −3.113 | 1177 | −3.766 | <0.001 |

| Overall pain intensity | 3.7 (0.2) | 3.4 (0.2) | −0.297 | 3.8 (0.2) | 2.1 (0.2) | −1.655 | 1123 | −5.277 | <0.001 |

df, degree of freedom; SE, standard error.

Part 1 = musculoskeletal pain.

Part 2 = pain related to internal organs head and skin.

Random-intercept model in a two-way repeated-measure configuration.

3.2 SPTP treatment allocation

In the intervention group, 62.8% of the patients (n = 103) started administration of acetaminophen (step 1) (i.e., acetaminophen 3 g/day), and 5.5% (n = 9) had an existing prescription of lower dose acetaminophen increased to a higher dosage. Thus, 112 patients received acetaminophen only. Three patients received step 2, all three had acetaminophen as well (two started with extended release morphine, and in one participant the primary prescription was adjusted). Step 3, the buprenorphine transdermal patch, was administered to 29 patients (17.7%), and the buprenorphine dosage was increased in an additional eight participants. In total, 37 participants were treated with buprenorphine transdermal patch, of whom 9 received the patch alone, with no other medication, due to swallowing issues. Twelve participants were treated with step 4, pregabalin, all of whom also received acetaminophen and the buprenorphine patch. All other patients (n = 28) had a combination of acetaminophen and buprenorphine.

3.3 Outcome measures

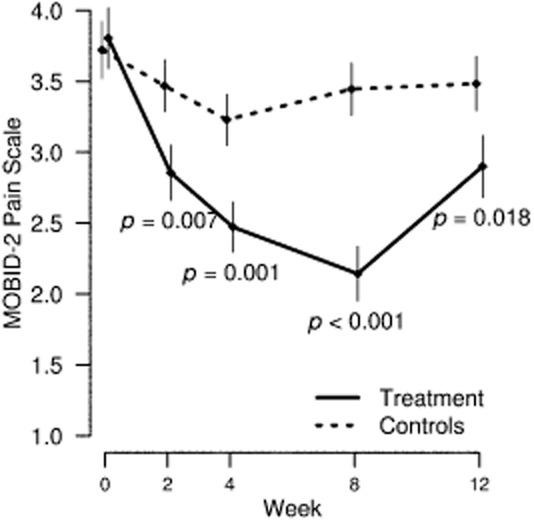

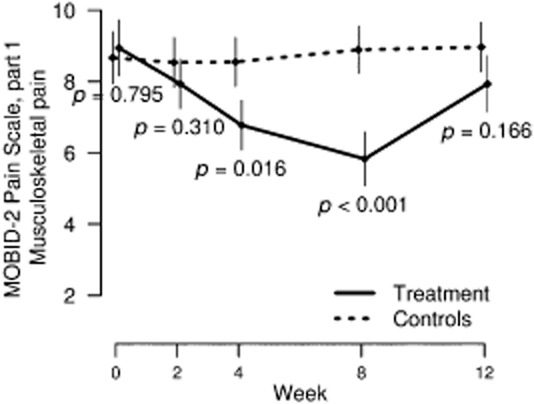

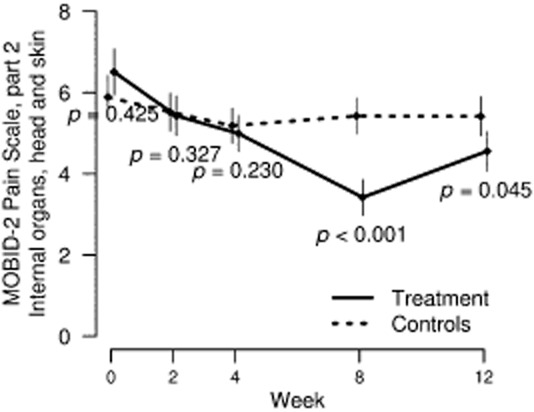

Analysis of pain intensity outcomes showed a significant improvement in the treatment group compared to controls in weeks 2 [average treatment effect (ATE) −0.703; SE 0.24; p = 0.004] and 8 (ATE = −1.393; SE 0.3; p < 0.001) (Table 2). This improvement was seen in MOBID-2 overall pain intensity (Fig. 2) in addition to specific items assessing musculoskeletal pain (Fig. 3) and pain related to internal organs, head and skin (Fig. 4). A sub-analysis of the participants who had a score of 3 or greater on the MOBID-2 Pain Scale at baseline also showed significant benefit in the treatment group compared with control (ATE = −1.739; p < 0.001) in week 8, with an average difference in pain reduction of 50% from baseline to week 8 in the treatment group.

Fig 2.

MOBID-2 Pain Scale total score with mean and standard error of the mean by control and treatment group over study period in total study sample.

Fig 3.

Mean and standard error of the mean in musculoskeletal pain (MOBID-2 Pain Scale part 1) scores by control and intervention groups over study period.

Fig 4.

Mean and standard error of the mean in pain related to internal organs, head and skin (MOBID-2 Pain Scale part 2) by control and intervention groups over study period.

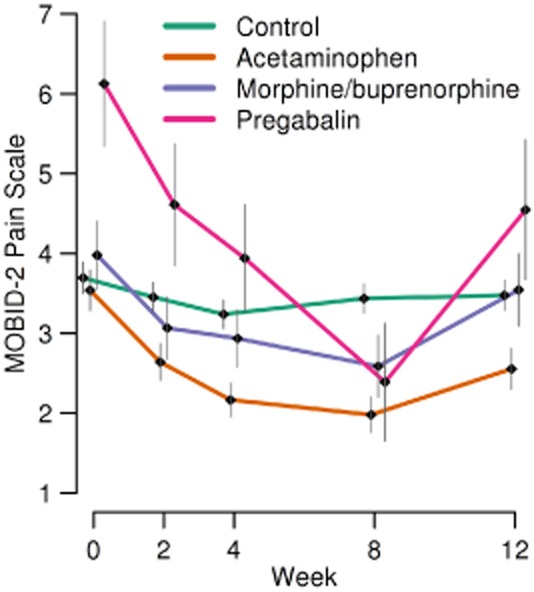

An analysis of the efficacy of different treatment approaches within the treatment group is presented in Fig. 5 and shows that participants treated with acetaminophen had significant improvement of pain at all time points, at week 2, 4 and 8, respectively (ATE = −0.67, p = 0.010; ATE = −0.92, p < 0.001; ATE = −1.30, p < 0.001). Patients treated with extended release morphine or buprenorphine transdermal patch also showed a significant decrease in MOBID-2 total scores, but not before week 8 (ATE = −1.14; p = 0.008). Patients treated with pregabalin had a clinically and statistically significant effect after 4 weeks (ATE = −1.8; p = 0.016) and showed a 61.7% reduction in pain from baseline to week 8 (ATE = −3.53; p < 0.001) compared with the control group. All participants treated with analgesia experienced worsening of pain following discontinuation of treatment during the washout period (acetaminophen: ATE = −0.76, p = 0.004; morphine or buprenorphine: ATE = −0.223, p = 0.075 pregabalin: ATE = −1.438, p = 0.075) (Fig. 5).

Fig 5.

MOBID-2 Pain Scale total score with mean and standard error of the mean, ordered by different analgesics (acetaminophen, extended release morphine and buprenorphine transdermal patch and pregabalin) and control group over study period.

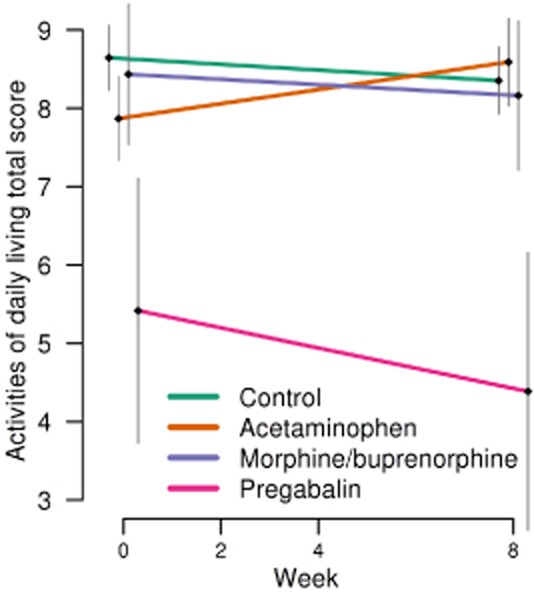

As previously reported (Husebo et al., 2011), no significant differences were seen in ADL between intervention and control groups at week 8 (p = 0.443). However, a sub-analysis of the acetaminophen group demonstrated improved ADL from baseline in the intervention group (ATE = +1.00; p = 0.022) at week 8 compared with the control group (Fig. 6). Entering NH unit as a nestling level did not alter our findings.

Fig 6.

Activity of daily living total score with mean and standard error of the mean, in order to different analgesics (acetaminophen, extended release morphine and buprenorphine transdermal patch and pregabalin) and control groups over study period.

3.4 Adverse events

Adverse events related to pain treatment interventions were registered for six patients (nausea n = 1, rash from patch n = 1, reduced appetite n = 2, somnolence/drowsiness n = 2). Most patients had acetaminophen (n = 120), but few left the study due to side effects (n = 2). Twice as many left from the opioid group (n = 4), although this group counted only 33% compared with the acetaminophen group. Pregabalin was given to 12 patients and 2 left the study. Fourteen deaths occurred during the 8-week study, of which six were participants in the intervention group.

4. Discussion

Pain is a clinically significant issue in dementia and is known to be related to the development of challenging symptoms such as BPSD and to have a significant impact on the quality of life and well-being. This article reports the first study to specifically measure the effect of pain treatment on the intensity of pain in people with dementia living in NH. This secondary analysis has shown that a stepwise approach to treating pain, which is tailored to the individual and adapted according to the patients' ongoing pain medication, significantly improved overall pain intensity in residents with moderate and severe dementia as measured by the MOBID-2 Pain Scale. Pain intensity was reduced by 45% in the intervention group after 8 weeks of treatment. All treatments resulted in benefit at the 8-week time point, with pregabalin also conferring effective pain relief by week 4, and acetaminophen providing benefit after 2 weeks. Importantly, all participants receiving analgesia experienced a significant worsening of pain when treatment was discontinued at the end of the trial. In addition to the impact on pain intensity, the study also found a significant improvement in physical function in participants receiving acetaminophen at 8 weeks. Pain is known to influence mobility and ability to perform daily tasks, and this is an important outcome. Since individuals receiving acetaminophen within step 1 of the SPTP for the full 8 weeks were predominantly experiencing mild or moderate pain, this finding indicates the additional value of analgesia for these individuals. Taken together, these findings clearly indicate the value of prompt and ongoing analgesic treatment in people with dementia where it is clinically appropriate.

Clinical guidelines for older adults have been published by the AGS panel from 1998, with regular updates in 2002 and 2009 (AGS Panel on Persistent Pain in Older Persons, 2009). The latest version also includes recommendations for accurate pain assessment in patients with dementia. However, guidelines for treatment of pain in patients with dementia are still urgently needed. We applied the recommendations from the AGS panel guidelines and focused upon titration and combination of two or more drugs with complementary mechanisms to attain improved pain reduction with less hepatic and kidney toxicity and adverse effects. Following the recommendations for clinicians, we used a maximum safe dose (<4 g/24 h) of acetaminophen for our patients (AGS Panel on Persistent Pain in Older Persons, 2009).

To our knowledge, this is also the first RCT to evaluate the anti-epileptic pregabalin to specifically treat neuropathic pain in patients with dementia. Treatment followed recommendations by the AGS panel, starting on low doses (25 mg/day), increasing to 75 mg/day where necessary. Pregabalin selectively binds to voltage-gated calcium channels in the brain and spinal cord and has been shown to decrease the release of excitatory neurotransmitter and reduce calcium channel function (Dooley et al., 2000; Fehrenbacker et al., 2003; Micheva et al., 2006). Pregabalin has shown initial benefit in an RCT of painful diabetic neuropathy (Rosenstock et al., 1982). Despite only 12 participants receiving pregabalin, the data indicate significant benefit. This finding is of particular importance due to the frequency of central neuropathic pain in people with dementia associated with white matter lesions in people who have experienced a stroke (Scherder et al., 2003; Scherder and Plooij, 2012). Studies also indicate the presence of neuropathic pain in people with vascular dementia, mixed dementia, Alzheimer's disease and frontotemporal dementia as a result of specific neuropathology (Scherder et al., 2003; Rosenstock et al., 1982; Husebo et al., 2008; Scherder and Plooij, 2012). Furthermore, diabetes is particularly common among people with dementia and is associated with considerable neuropathic pain (Wild et al., 2004; Zilliox and Russell, 2011). Pregabalin therefore warrants further investigation as an analgesic treatment option for this group.

Our dataset has revealed valuable data regarding the specific tolerability of different pharmacological treatments for pain in this patient group. The largest proportion of participants in the trial who received treatment was prescribed with acetaminophen. This treatment was extremely well tolerated. Only 2 of 120 patients left the study, both because patient's relatives withdrew consent. Acetaminophen is therefore both effective and very well tolerated by people with dementia, confirming the suitability of this agent as a first-line analgesic. Forty participants received an opioid analgesic (extended release morphine or buprenorphine transdermal patch), of whom four withdrew due to possible side effects (femur fracture, drowsiness and nausea, local reaction to the transdermal patch, appetite and eating disturbances). This outcome reflects the literature, which indicates that the opioid drug class is generally well tolerated with the most common adverse drug reactions being arrhythmia (12.1%), pruritus (10.5%), nausea (9.2%) and dizziness (4.6%) (Hamunen et al., 2008; Huang and Mallet, 2013), in addition to an increased risk of falls and hip fractures (Deandrea et al., 2010). While buprenorphine appears to be safe in people with renal impairment, it should be noted that due to the metabolic pathway of this agent, careful monitoring is required in people with hepatic impairment, and this is an important consideration when prescribing to people with dementia. The only previous RCT of an opioid for pain in dementia reported a high 47% dropout rate (Manfredi et al., 2003). Our study has demonstrated efficacy and improved tolerability with buprenorphine administered through transdermal patches, which are already in use to treat chronic nociceptive, neuropathic and cancer-related pain (Pergolizzi et al., 2010). Following recommendations by the AGS panel to keep stable blood levels, 12 patients received the buprenorphine patch only, as they already were on a strong morphine option and had swallowing difficulties.

The late-onset effect of buprenorphine transdermal patch after 8 weeks was an unexpected finding. Cognitive function and ADL function were stable over the period, suggesting that reduced pain was a treatment effect and not related to sedation. The lower tolerability of opioids in people in dementia indicates the need for an intermediate analgesic as an alternative to escalation to opioids where acetaminophen is not sufficient. There are both benefits and harms associated with the use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (Huang et al., 1999; Bannwarth, 2008), and a further evaluation of this analgesic group could be of value in informing the management of pain in people with dementia in the future.

Withdrawal among participants receiving pregabalin was relatively high in this study, with 2 of 12 participants withdrawing due to somnolence, nausea and drowsiness. This occurred despite the lower dosage used in the study (25 mg) compared with the recommended daily dose of 150 mg used in younger individuals where the safety profile is very good. This provides the first safety data for pregabalin in this patient group. However, our results have to be controlled by a clinical trial with appropriate sample size.

To date, the prevalence of pain in people with dementia in NH has not been fully established. While it was not the primary purpose of this study, baseline data indicate that almost 60% of these individuals were experiencing significant pain, with a pain score of at least 3. Furthermore, almost 70% had one or more diagnoses of pain, indicating an extensive prevalence of pain. The pattern of prescribing within the SPTP also indicates that many individuals were receiving suboptimal analgesia prior to the study commencing, most likely due to undiagnosed mild or moderate pain. These secondary findings provide further weight to the need for more effective identification of pain in dementia through an accurate and easily implementable assessment and monitoring tool. The MOBID-2 Pain Scale utilized in this study has shown excellent reliability and sensitivity to date, and this study further confirms its utility in research. It will now be essential to further establish its use in clinical practice in order to provide health-care professionals with adequate knowledge, as well as an effective pain assessment (Pieper et al., 2013).

This is the largest study to have investigated the effect of pain treatment on pain intensity in people with dementia living in NH. It has provided robust, well-powered and clinically meaningful data that demonstrate the efficacy of a stepped pharmacological treatment approach in this patient group. A possible limitation in this study may be the heterogeneous nature of the dementia cohort as no definition was made of the sub-types of dementia within the participants. However, due to the frequent absence of a differential diagnosis in people with dementia in NH, it is more meaningful to consider treatment effects in this group since it is representative of the current clinical situation and will provide information that can be directly translated to guidance for practice. The data provide robust data for the overall cohort. Efficacy data for the individual pharmacological agents are necessarily derived from smaller groups of participants due to the stepped nature of the intervention. It would therefore be a valuable next step to evaluate each of the agents in larger cohorts to confirm the efficacy demonstrated in this study. Further evaluation of alternative treatment options such as anticonvulsants, antidepressants and novel analgesics is also urgently needed in order to establish the most effective stepwise treatment regimen for this patient group.

Author contributions

B.S.H., C.B. and D.A. conceived the study, the design of the study and obtained funding. B.S.H. and R.K.S. collected data. R.K.S., R.S. and B.S.H. contributed to the statistical analysis. All authors contributed to the interpretation of the data, the carrying out of the study and the writing of the manuscript. B.S.H. and R.K.S. are guarantors for the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

We thank the patients, their relatives and the NH staff for their willingness and motivation, which made this study possible. A.C. and C.B. would like to thank the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Mental Health Biomedical Research Centre and Dementia Unit at South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust and Institute of Psychiatry at King's College London for their contribution to this work.

Clinical study registration

The trial is registered at ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT01021696 ) and at the Norwegian Medicines Agency (EudraCT nr 2008-007490-20).

Ethical approval

Regional Committee for Medical Ethics, Western Norway (REK-Vest 248.08).

Copyright

The corresponding author has the right to grant on behalf of all authors and does grant on behalf of all authors.

References

- Achterberg WP, Gambassi G, Finne-Soveri H, Liperoti R, Noro A, Frijters DH, Cherubini A, Dell'aquila H, Ribbe MW. Pain in European long-term care facilities: Cross-national study in Finland, Italy and the Netherlands. Pain. 2010;148:70–74. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2009.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Achterberg WP, Pieper MJC, van Dalen-Kok AH, de Waal MWM, Husebo BS, Lautenbacher S, Kunz M, Scherder EJA, Corbett A. Pain management in patients with dementia. Clin Interv Aging. 2013;8:1471–1482. doi: 10.2147/CIA.S36739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Achterberg WP, Pot AM, Scherder EJ, Ribbe MW. Pain in the nursing home: Assessment and treatment on different types of care wards. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2007;34:480–487. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2006.12.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- AGS Panel on Persistent Pain in Older Persons. Pharmacological management of persistent pain in older persons. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2009;57:1331–1366. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2009.02376.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahn H, Horgas A. The relationship between pain and disruptive behaviors in nursing home resident with dementia. BMC Geriatr. 2013;13:14. doi: 10.1186/1471-2318-13-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayalon L. Willingness to participate in Alzheimer's disease research and attitudes towards proxy-informed consent: Results from the Health and Retirement Study. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2009;17:65–74. doi: 10.1097/JGP.0b013e31818cd3d3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bannwarth B. Safety of the nonselective NSAID nabumetone: Focus on gastrointestinal tolerability. Drug Saf. 2008;6:485–503. doi: 10.2165/00002018-200831060-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buffum MD, Sands L, Miaskowski C, Brod M, Washburn A. A clinical trial of the effectiveness of regularly scheduled versus as-needed administration of acetaminophen in the management of discomfort in older adults with dementia. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004;57:1093–1097. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2004.52305.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chibnall JT, Tait RC, Harman B, Luebbert RA. Effect of acetaminophen on behavior, well-being, and psychotropic medication use in nursing home residents with moderate-to-severe dementia. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53:1921–1929. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53572.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cipher DJ, Clifford RA. Dementia, pain, depression, behavioral disturbances, and ADLs: Toward a comprehensive conceptualization of quality of life in long-term care. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2004;19:741–748. doi: 10.1002/gps.1155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen-Mansfield J, Marx M, Rosenthal A. A description of agitation in a nursing home. J Gerontol. 1989;44:M77–M84. doi: 10.1093/geronj/44.3.m77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen-Mansfield J, Taylor L. The relationship between depressed affect, pain and cognitive function: A cross-sectional analysis of two elderly populations. Aging Ment Health. 1998;4:313–318. [Google Scholar]

- Corbett A, Husebo BS, Malcangio M, Staniland A, Cohen-Mansfield J, Aarsland D, Ballard C. Assessment and treatment of pain in people with dementia. Nat Rev Neurol. 2012a;10:264–274. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2012.53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corbett A, Smith J, Creese B, Ballard C. Treatment of behavioral and psychological symptoms of Alzheimer's disease. Curr Treat Options Neurol. 2012b;14:113–125. doi: 10.1007/s11940-012-0166-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cordner Z, Blass DM, Rabins PV, Black BS. Quality of life in nursing home residents with advanced dementia. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2010;58:2394–2400. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2010.03170.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deandrea S, Lucenteforte E, Bravi F, Foschi R, La Vecchia C, Negri E. Risk factors for falls in community-dwelling older people a systematic review and meta-analysis. Epidemiology. 2010;21:658–668. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0b013e3181e89905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dooley DJ, Mieske CA, Borosky SA. Inhibition of K(+)-evoked glutamate release from rat neo-cortical and hippocampal slices by gabapentin. Neurosci Lett. 2000;280:107–110. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(00)00769-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fehrenbacker JC, Taylor CP, Vasko MR. Pregabalin and gabapentin reduce release of substance P and CGRP from rat spinal tissues only after inflammation or activation of protein kinase C. Pain. 2003;105:133–144. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3959(03)00173-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finkel SI, Lyons JS, Anderson RL. Reliability and validity of the Cohen-Mansfield agitation inventory in institutionalized elderly. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 1992;7:487–490. [Google Scholar]

- Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. ‘Mini-Mental State’. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975;12:189–198. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giron MST, Forsell Y, Bernsten C, Thorslund M, Winblad B, Fastbom J. Sleep problems in a very old population: Drug use and clinical correlates. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2002;57:M236–M240. doi: 10.1093/gerona/57.4.m236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamunen K, Laitinen-Parkkonen P, Paakkari P, Breivik H, Gordh T, Jensen NH, Kalso E. What do different databases tell about the use of opioids in seven European countries in 2012? Eur J Pain. 2008;6:705–715. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpain.2007.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang AR, Mallet L. Prescribing opioids in older people. Maturitas. 2013;74:123–129. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2012.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang AR, Mallet L, Rochefort CM, Eguale T, Buckeridge DL, Tamblyn R. Medication-related falls in the elderly: Causative factors and preventive strategies. Drugs Aging. 2012;5:359–376. doi: 10.2165/11599460-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang JQ, Sridhar S, Hunt RH. Gastrointestinal safety profile of nabumetone: A meta-analysis. Am J Med. 1999;6A:55S–61S. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(99)00368-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurley AC, Volicer BJ, Hanrahan PA, Houde S, Volicer L. Assessment of discomfort in advanced Alzheimer patients. Res Nurs Health. 1992;5:369–377. doi: 10.1002/nur.4770150506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Husebo BS, Ballard C, Cohen-Mansfield J, Seifert R, Aarsland D. The response of agitated behaviour to pain management in persons with dementia. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2013;12:S1064–7481. doi: 10.1016/j.jagp.2012.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Husebo BS, Ballard C, Sandvik R, Nilsen OB, Aarsland D. Efficacy of treating pain to reduce behavioural disturbances in residents of nursing homes with dementia: Cluster randomised clinical trial. BMJ. 2011;343:1–10. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d4065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Husebo BS, Strand LI, Moe-Nilssen R, Husebo BS, Ljunggren AE. Pain behavior and pain intensity in older persons with severe dementia: Reliability of the MOBID Pain Scale by video uptake. Scand J Caring Sci. 2009;23:180–189. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-6712.2008.00606.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Husebo BS, Strand LI, Moe-Nilssen R, Husebo SB, Aarsland D, Ljunggren AE. Who suffers most? Dementia and pain in nursing home patients: A cross-sectional study. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2008;9:427–433. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2008.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Husebo BS, Strand LI, Moe-Nilssen R, Husebo SB, Ljunggren AE. Mobilization-Observation-Behavior-Intensity-Dementia Pain Scale (MOBID): Development and validation of a nurse-administered pain assessment tool for use in dementia. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2007;34:67–80. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2006.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Husebo BS, Strand LI, Moe-Nilssen R, Husebo SB, Ljunggren AE. Pain in older persons with severe dementia. Psychometric properties of the Mobilization-Observation-Behaviour-Intensity-Dementia (MOBID-2) Pain Scale in a clinical setting. Scand J Caring Sci. 2010;24:380–391. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-6712.2009.00710.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Husebo BS, Ostelo R, Strand LI. The MOBID-2 pain scale: Reliability and responsiveness to pain in patients with dementia. Eur J Pain. 18:1419–1430. doi: 10.1002/ejp.507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalaria RN, Maestre GE, Arizaga R, Friedland RP, Galasko D, Hall KT, Luchsinger JA, Ogunniyi A, Perry EK, Potocnik F, Prince M, Stewart R, Wimo A, Zhang ZX, Antuono P World Federation of Neurology Dementia Research Group. Alzheimer's disease and vascular dementia in developing countries: Prevalence, management, and risk factors. Lancet Neurol. 2008;7:812–826. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(08)70169-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovach CR, Logan BR, Noonan PE, Schlidt AM, Smerz J, Simpson M, Wells T. Effects of the serial trial intervention on discomfort and behavior of nursing home residents with dementia. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen. 2006;21:147–155. doi: 10.1177/1533317506288949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin PC, Lin LC, Shyu YIL, Hua MS. Predictors of pain in nursing home residents with dementia: A cross-sectional study. J Clin Nurs. 2011;20:1849–1857. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2010.03695.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorenz KA, Lynn J, Shugarman LR, Wilkinson A, Mularski RA, Morton SC, Hughes RG, Hilton LK, Maglione M, Rhodes SL, Rolon C, Sun VC, Shekele PG. Evidence for improving palliative care at the end of life: A systematic review. Ann Intern Med. 2008;148:147–159. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-148-2-200801150-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahoney FI, Barthel DW. Functional evaluation: The Barthel index. Md State Med J. 1965;14:61–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manfredi PL, Breuer B, Wallenstein S, Stegmann M, Bottomley G, Libow L. Opioid treatment for agitation in patients with advanced dementia. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2003;18:700–705. doi: 10.1002/gps.906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Micheva KD, Taylor CP, Smith SJ. Pregabaline reduced the release of synaptic vesicles from cultured hippocampal neurons. Mol Pharmacol. 2006;70:467–476. doi: 10.1124/mol.106.023309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pergolizzi J, Aloisi AM, Dahan A, Filitz J, Langford R, Likar R, Mercandante S, Morlion B, Raffa RB, Sabatowski R, Sacerdote P, Torres LM, Weinbroum AA. Current knowledge of buprenorphine and its unique pharmacological profile. Pain Pract. 2010;5:428–450. doi: 10.1111/j.1533-2500.2010.00378.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pickering G, Jourdan D, Dubray C. Acute versus chronic pain treatment in Alzheimer's disease. Eur J Pain. 2006;10:379–384. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpain.2005.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pieper MJ, van Dalen-Kok AH, Francke AL, van der Steen JT, Scherder EJ, Husebø BS, Achterberg WP. Interventions targeting pain or behaviour in dementia: A systematic review. Ageing Res Rev. 2013;4:1042–1055. doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2013.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reisberg B, Ferris SH, de Leon MJ, Crook T. The Global Deterioration Scale for assessment of primary degenerative dementia. Am J Psychiatry. 33:104–110. doi: 10.1176/ajp.139.9.1136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenstock J, Tuckman M, LaMoreauxm L, Sharma U. Pregabalin for the treatment of painful diabetic peripheral neuropathy: A double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Pain. 2004;3:628–638. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2004.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scherder EJ, Plooij B. Assessment and management of pain, with particular emphasis on central neuropathic pain, in moderate and severe dementia. Drugs Aging. 2012;29:701–706. doi: 10.1007/s40266-012-0001-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scherder EJ, Slates J, Deijen JB, Gorter Y, Ooms ME, Ribbe M, Vuijk PJ, Feldt K, van de Valk M, Bouma A, Sergeant JA. Pain assessment in patients with possible vascular dementia. Psychiatry. 2003;2:133–145. doi: 10.1521/psyc.66.2.133.20618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verbeke G, Molenberghs G. Linear Mixed Models for Longitudinal Data. New York: Springer; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Warner J, Nomani E. Giving consent in dementia research. Lancet. 2008;19:183–185. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61049-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wild S, Roglic G, Green A, Sicree R, King H. Global prevalence of diabetes: Estimates for the year 2000 and projections for 2030. Diabetes Care. 2004;5:1047–1053. doi: 10.2337/diacare.27.5.1047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zilliox L, Russell JW. Treatment of diabetic sensory polyneuropathy. Curr Treat Options Neurol. 2011;2:143–159. doi: 10.1007/s11940-011-0113-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]