Abstract

Ataxia telangiectasia-mutated and Rad3-related (ATR) plays a central role in cell-cycle regulation, transmitting DNA damage signals to downstream effectors of cell-cycle progression. In animals, ATR is an essential gene. Here, we find that Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana) atr−/− mutants were viable, fertile, and phenotypically wild-type in the absence of exogenous DNA damaging agents but exhibit altered expression of AtRNR1 (ribonucleotide reductase large subunit) and alteration of some damage-induced cell-cycle checkpoints. atr mutants were hypersensitive to hydroxyurea (HU), aphidicolin, and UV-B light but only mildly sensitive to γ-radiation. G2 arrest was observed in response to γ-irradiation in both wild-type and atr plants, albeit with slightly different kinetics, suggesting that ATR plays a secondary role in response to double-strand breaks. G2 arrest also was observed in wild-type plants in response to aphidicolin but was defective in atr mutants, resulting in compaction of nuclei and subsequent cell death. By contrast, HU-treated wild-type and atr plants arrested in G1 and showed no obvious signs of cell death. We propose that, in plants, HU invokes a novel checkpoint responsive to low levels of deoxynucleotide triphosphates. These results demonstrate the important role of cell-cycle checkpoints in the ability of plant cells to sense and cope with problems associated with DNA replication.

INTRODUCTION

The detection of DNA damage is an important aspect of damage resistance. Cells do not routinely express all DNA repair mechanisms, but instead upregulate these functions as required, concomitantly slowing the cell cycle to permit time for repair before S-phase (as replication past damaged sites may be mutagenic) or before M-phase (after which point double-strand breaks and lesions in daughter strand gaps may become far more problematic to repair). Damage is generally detected by protein complexes in the form of single-stranded DNA (Crowley and Courcelle, 2002; Zou and Elledge, 2003), created when the replication fork is physically blocked by DNA lesions or during the process of DNA repair (e.g., homologous recombination, nucleotide excision repair, and mismatch repair). These damage sensors then activate downstream checkpoint mechanisms to prevent progression into the next phase of the cell cycle as well as upregulate DNA repair (Nyberg et al., 2002).

Some damage sensors also are involved in the regulation of deoxynucleotide triphosphate (dNTP) pools, which may in turn influence the mode of DNA replication. One of the primary targets for dNTP pool regulation is the enzyme ribonucleotide reductase (RNR), which catalyzes the final reduction step in the production of dNTPs. Genetic studies in Saccharomyces cerevisiae suggest that the elevation of dNTP levels (through transcriptional and/or posttranslational regulation of RNR) in response to DNA damage may result in more efficient translesion DNA synthesis, enabling the cell to complete replication in spite of the presence of persisting lesions (Tanaka et al., 2000; Chabes et al., 2003; Yao et al., 2003).

The proteins that sense damaged or single-stranded DNAs and trigger these elaborate responses have been extensively characterized in organisms ranging from bacteria to human (Crowley and Courcelle, 2002; Melo and Toczyski, 2002). In plants, however, the regulation of DNA replication and repair and the cell cycle in response to DNA damage is only beginning to be understood.

The Schizosaccharomyces pombe Rad3 homologs (ataxia telangiectasia-mutated and Rad3-related [ATR] and ataxia telangiectasia-mutated [ATM] in mammals, Mec1 in S. cerevisiae) are essential regulators of cell-cycle checkpoints, sensing DNA damage and/or single-stranded DNA and activating downstream effectors of cell-cycle progression and DNA repair. ATM is activated primarily by DNA double-strand breaks. ATM-deficient plants and animals are hypersensitive to γ-irradiation but not to replication-blocking agents such as UV-B light, hydroxyurea (HU), or aphidicolin (Abraham, 2001; Garcia et al., 2003; K. Culligan and A. Britt, unpublished data). Furthermore, the Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana) ATM homolog is required for the transcriptional induction of repair genes in response to γ-irradiation and for efficient progression through meiosis (Garcia et al., 2003), though its role in plant cell-cycle responses to DNA damage has not yet been determined. In animals, activated ATM phoshorylates downstream components of checkpoint pathways that include p53, BRCA1, NBS1, and CHK2, initiating G1-, S-, or G2-phase arrest and/or apoptosis.

By contrast, ATR is activated primarily by agents that block the progression of replication forks. ATR dominant-negative and conditional knockout mammalian cell lines display hypersensitivity to UV-B light, HU, and aphidicolin but are also sensitive to γ-radiation. Thus, in animal cells, ATR is thought to play a more generalized role in response to DNA damage than ATM. Activated ATR phosphorylates CHK1 to initiate G2-phase arrest but may also act at other points of the cell cycle, as evidenced by ATR-dependent phosphorylation of BRCA1 (Tibbetts et al., 2000; Melo and Toczyski, 2002). However, the determination of the full extent of ATR's role in genome maintenance has been complicated by the fact that ATR homozygous knockouts die early in embryogenesis (Brown and Baltimore, 2000; de Klein et al., 2000); cre/lox-induced nulls survive only a few rounds of cell division, and the dominant-negative reduction-of-function cell lines have yielded conflicting results (Cliby et al., 1998; Wright et al., 1998). Thus, a tractable genetic system in which a null allele of ATR could be tolerated throughout the development of a higher organism would be particularly desirable.

Here, we investigate the effects of an ATR T-DNA insertion allele in the plant Arabidopsis. The allele has a 6-kb insertion within the kinase domain and is presumably null. We find that the mutant plant (atr) is viable and developmentally normal in the absence of exogenous DNA-damaging treatments but is hypersensitive to the replication-blocking agents UV-B light, HU, and aphidicolin. Thus, AtATR does appear to act as a functional homolog of its mammalian counterpart. However, the Arabidopsis atr mutants differ from mammalian mutants not only in terms of their viability but also in their degree of sensitivity to γ-radiation.

In the course of these experiments, we also observed a differential response to HU versus aphidicolin in wild-type cells, with HU primarily inducing a G1 arrest, whereas aphidicolin induced arrest in G2. This stands in contrast with the G2 arrest induced by both agents in yeast and mammals (at concentrations that allow S-phase progression) and suggests that plants may possess a novel G1 checkpoint response to low dNTP levels. The G2 arrest in response to aphidicolin was abrogated in atr mutants, suggesting that ATR regulates the G2 checkpoint response to replication blocks, as it does in mammals. Moreover, programmed cell death was observed in atr mutants in response to aphidicolin, but not HU, under our experimental conditions. We propose a model that suggests that the HU and aphidicolin hypersensitivities of atr mutants are the result of its defect in the G2 checkpoint response to blocked replication forks.

RESULTS

Identification of the ATR Ortholog in Arabidopsis

ATR orthologs, including Mec1 of S. cerevisiae and Rad3 of S. pombe, are members of a large gene family in eukaryotes that encode Ser-Thr kinases, whose C-terminal catalytic domains share similarity to yeast and mammalian phosphoinositide 3-kinases (Tibbetts and Abraham, 2000). We searched the Arabidopsis genome for homologs of ATR, using the S. pombe Rad3 C-terminal domain as a query sequence, and found several candidate genes. Phylogenetic analysis of the corresponding predicted full-length protein sequences indicated that one was an ortholog of Target of Rapamycin (TOR), one an ortholog of ATM, and one was an ortholog of ATR (Figure 1A). No other candidate genes fell into these broad categories. The ATR-orthologous sequence (previously reported in GenBank as mRNA AtRad3 [AB040133], which we designate here as AtATR) revealed high similarity throughout its entire length to other ATR proteins, but its similarity to ATM and TOR sequences was limited only to the highly conserved middle and C-terminal regions. We confirmed the GenBank sequence and intron/exon boundaries by isolating and sequencing cDNAs of AtATR (∼8.1 kb, ecotype Wassilewskija [Ws]) using RT-PCR, and the resulting sequence predicted 17 exons encoding a protein of 2702 amino acids (Figure 1B).

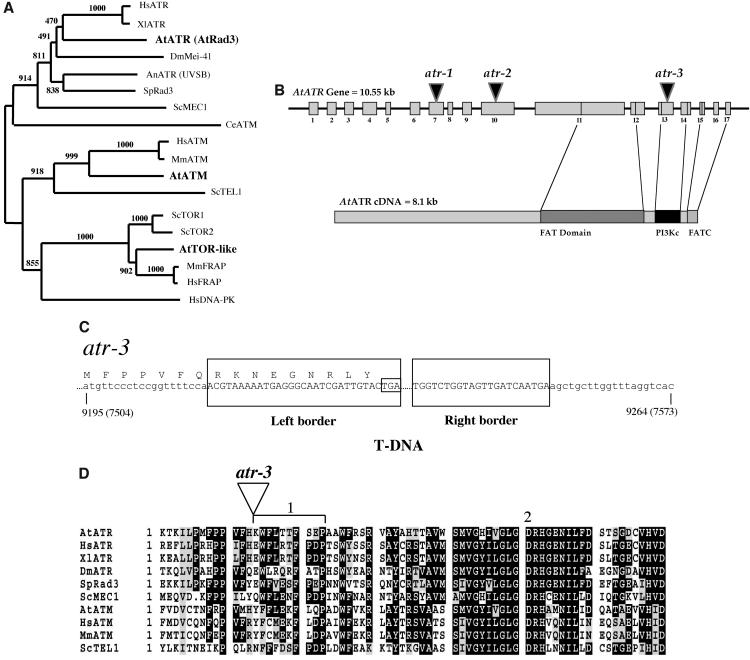

Figure 1.

Phylogenetic Analysis, Structure, and T-DNA Insertions of AtATR.

(A) The neighbor-joining tree of Rad3-like protein sequences was performed as described (Culligan et al., 2000). Numbers above each branch represent the number of times the branch was found in 1000 bootstrap replicas. Arabidopsis sequences are in bold. No DNA-PKcs (DNA–protein kinase catalytic subunit)-like sequences were identified in the Arabidopsis genome.

(B) Overview of the AtATR gene, positions of atr-1, atr-2, and atr-3 T-DNA insertions, and its corresponding cDNA structure. Numbered gray boxes indicate exons of AtATR; the positions of the T-DNA insertions are denoted as triangles. The cDNA structure (bottom) shows the corresponding highly conserved domains found in ATM, ATR, TOR, and FKBP12-rapamycin-associated protein sequences, including the kinase domain denoted as a black rectangle (PI3Kc). The cDNA sequence was confirmed by isolating and sequencing independent cDNAs of AtATR (ecotype Ws) using RT-PCR. The resulting sequence predicts 17 exons that encode a protein of 2702 amino acids.

(C) Structure of the atr-3 T-DNA insertion. Capital letters denote T-DNA insertion sequence. Corresponding amino acids are shown above the DNA sequence. The left-border sequence encodes 10 new amino acids within the AtATR reading frame before a premature stop (boxed as TGA). The approximate size of the entire insertion is 6 kb.

(D) Partial alignment of the kinase domain where atr-3 is inserted: 1 denotes a 30-bp deletion (equivalent to 10 amino acids) caused by the insertion, and 2 denotes the position of the catalytic Asp required for kinase function.

Identification of T-DNA Insertion-Mutation Alleles in AtATR

To study the function of ATR in Arabidopsis, we searched for lines with T-DNA insertions within ATR. Three independent lines were identified from different collections and were termed atr-1 (Arabidopsis Knockout Facility, ecotype Ws), atr-2 (SIGnAL database, ecotype Columbia), and atr-3 (FLAG database, ecotype Ws). atr-1 and atr-2 contain insertions in the middle of ATR, in exons 7 and 10, respectively (Figure 1B). atr-3 contains a single, ∼6-kb T-DNA insertion within the highly conserved C-terminal kinase (PI3Kc) domain (Figures 1B to 1D), which causes a 30-bp deletion adjacent to the catalytic Asp required for kinase function. RT-PCR analysis of the C-terminal region of ATR confirms that the transcript is absent in atr-3 (Figure 7). Thus, we believe atr-3 is likely to be a null mutation and have focused the majority of our characterization on this line (termed atr below). Nonetheless, all three lines exhibit a similar recessive phenotype (see below) that cosegregates with their respective T-DNA insertions in ATR.

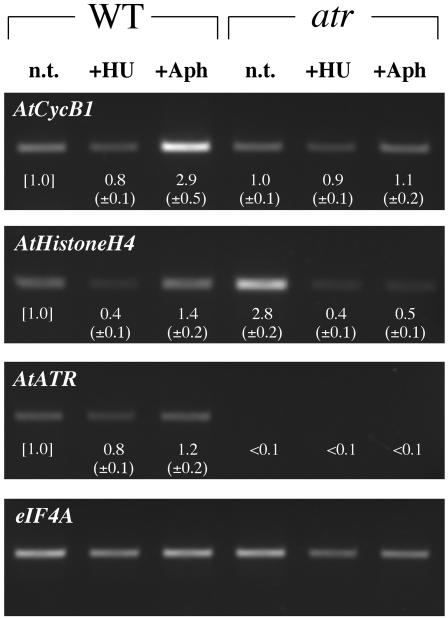

Figure 7.

Semiquantitative RT-PCR Analysis of G2-Phase and S-Phase–Specific Genes.

Wild-type and atr plants were grown as described in Figure 6. Root tips (n > 200) were excised (1 to 2 mm from the root cap) from wild-type and atr plants 4-d after transfer for RNA extraction, cDNA preparation, and RT-PCR analysis. Twenty-five microliters of each RT-PCR sample was loaded on an ethidium bromide–stained agarose gel, and representative gels are shown. All RT-PCR products were between 400 bp and 850 bp in size. The RT-PCR product of eIF4A (eukaryotic initiation factor) was employed as a standard for RT-PCR amplification. Numbers below each gel band denote its relative expression (first normalized to eIF4A) to the wild-type untreated (n.t.) sample. Standard deviations for two replicates are shown in parentheses. Aph, aphidicolin.

Neither AtATR nor AtATM Is Required during Normal Somatic Development

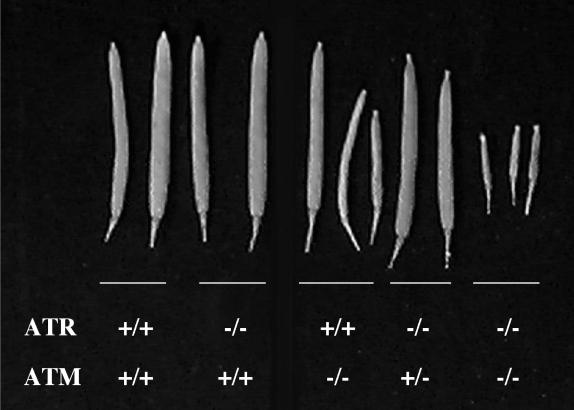

All three atr homozygous alleles are phenotypically wild-type in growth (of the root and shoot) and development (leaf and flower development, seed set and viability) under standard conditions. Thus, ATR is not essential for normal somatic development in Arabidopsis. By contrast, ATR is an essential gene in animals; ATR knockout mice die early in embryogenesis (Brown and Baltimore, 2000; de Klein et al., 2000), whereas conditional knockout human cell lines divide only a few times before dying (Cortez et al., 2001; Brown and Baltimore, 2003). Because ATR and ATM are paralogs known to play partially overlapping roles in animal cells (Abraham, 2001), it is possible that ATM could compensate for ATR deficiency in Arabidopsis. To test this hypothesis, we established atr atm double mutants and found no obvious phenotypic differences (in vegetative growth and development) when compared with wild-type or single-mutant plants, indicating that neither ATR nor ATM play an essential role during normal vegetative (somatic) growth.

The double mutants, however, were completely sterile (Figure 2). atr mutant plants are fertile and produce normal gametes; pollen staining for viable spores revealed no differences versus the wild type, and the siliques were full (normal seed set). atm mutant plants, however, are partially sterile because of abundant chromosomal fragmentation during meiosis, resulting in a reduction in viable pollen and reduced seed set (Garcia et al., 2003). We suggest that AtATM and AtATR play partially redundant roles during meiosis in Arabidopsis.

Figure 2.

Siliques Harvested from Mature Wild-Type, atr, and atm-1 (Ecotype Ws) Mutants.

Wild-type, atr−/−, and atr−/− atm+/− on average produce ∼50 seeds per silique. atm plants, which are partially sterile, produce a range of silique sizes with much fewer (<10 on average) seeds. The siliques from the double atr atm line produced no seeds and were unable to outcross as males or females, suggesting complete sterility.

AtATR Is Required for Full Transcriptional Induction of the Large Subunit of RNR, AtRNR1

In the budding yeast S. cerevisiae, Mec1 (the ATR ortholog) regulates expression of RNR at both the transcriptional and posttranscriptional levels (Zhao et al., 2001). Null alleles of mec1 are lethal, but this lethality is suppressed by mutations in genes that negatively regulate RNR (Huang et al., 1998; Zhao et al., 1998), such as the transcriptional repressor Crt1 (Huang et al., 1998) or the inhibitor of RNR activity Sml1 (Zhao et al., 1998). Derepression of RNR transcription in response to DNA damage is dependent on Mec1 and the downstream kinase Dun1, which indirectly induces an inhibitory phosphorylation of Crt1 (Elledge et al., 1992; Zhao and Rothstein, 2002). Whether Mec1 or ATR also play a role in the normal cell-cycle specific regulation of RNR transcription in unchallenged cells remains unclear.

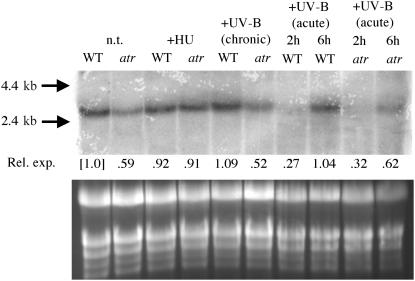

We therefore wanted to determine if RNR transcription is regulated in an AtATR-dependent manner in challenged and/or unchallenged plants. We searched GenBank and identified the Arabidopsis homolog of RNR1, the large subunit of RNR (accession number AF092841). Transcription of RNR1 has already been shown to be regulated in a cell-cycle dependent manner in tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum) (Chabouté et al., 1998, 2002), and transcription is induced by DNA damage in this plant (M.E. Chabouté, personal communication). We probed RNA gel blots with AtRNR1 and found that AtRNR1 transcript is reduced in atr mutants, down ∼40% versus the wild type under standard conditions (Figure 3), suggesting that ATR is required to support normal expression of RNR1. Plants treated with chronic doses of UV-B light, sufficient to inhibit but not eliminate growth, display a level of RNR1 transcript similar to that observed under standard (UV-free) conditions, and again atr plants exhibit reduced levels of RNR1 transcript. Interestingly, plants treated with acute doses of UV-B light displayed a transient inhibition of AtRNR1 transcript (at 2 h postirradiation), followed by a return to standard condition levels at 6 h postirradiation. This UV-induced suppression is not ATR dependent, though again, the overall level of RNR1 transcript is reduced (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

RNA Gel Blot Analysis of the Wild Type and atr.

RNA samples were prepared from 7-d-old wild-type and atr plants (whole seedlings) sown on MS agar plates plus 1 mM HU, in the presence of UV-B (chronic dose), or left untreated (n.t.). For acute doses of UV-B light, the wild type and atr were grown for 7 d on MS agar plates and irradiated with UV-B light (10 kJ/m2) in the dark and then harvested 2 h or 6 h after UV irradiation. Approximately 30 μg (lanes 1 to 6) or 25 μg (lanes 7 to 10) of total RNA from each sample was blotted and probed with a putative AtRNR1 (GenBank AF092841) mRNA sequence. The AtRNR1 mRNA sequence is 2.65 kb. The bands corresponding to 4.4 and 2.4 kb of the RNA ladder (Ambion) are shown at the left and denoted as arrows. The ethidium bromide–stained gel is shown (bottom), and the relative rates of expression (Rel. exp.) were determined with respect to wild-type no-treatment control. This experiment was repeated with independently isolated RNA samples with very similar results.

Because we used HU (an inhibitor of RNR activity) as a DNA replication-blocking agent (see below) to characterize the phenotypic effects of the atr mutant, we wanted to determine the effects of HU treatment on RNR expression in whole plants. Surprisingly, in the presence of HU, RNR1 expression is the same in both the wild type and atr (Figure 3) with levels similar to the wild type under standard conditions. This suggests that there are additional ATR-independent levels of RNR1 regulation in Arabidopsis and is consistent with previous studies showing that HU induces RNR expression in plants (Chabouté et al., 1998).

Arabidopsis atr Mutants Are Mildly Sensitive to Acute Doses of γ-Radiation but Proficient in γ-Induced G2 Arrest

Conditional mutants of ATR/Mec1 in mammalian cells and S. cerevisiae, as well as Rad3 mutants in S. pombe, are hypersensitive to γ-radiation (Jimenez et al., 1992; Cliby et al., 1998; Wright et al., 1998). Mutants of ATM/scTel1, including those in Arabidopsis, are also hypersensitive to γ-radiation (Sedgwick and Boder, 1991; Garcia et al., 2003). This sensitivity is generally interpreted as a failure of checkpoint responses to double-strand breaks (Abraham, 2001) but may also involve a failure to induce DNA repair genes (Garcia et al., 2003). To determine whether ATR plays a role in γ-resistance in Arabidopsis, we challenged wild-type, atr, and atm lines with sublethal doses of γ-radiation. In contrast with atm mutants, atr lines exhibited only mild sensitivity to γ-radiation. The root length of atr was reduced by ∼30% versus the wild type 7 d after seeds were γ-irradiated at 200 Gray (Gy), whereas atm root length was reduced by >95% (Figure 4A).

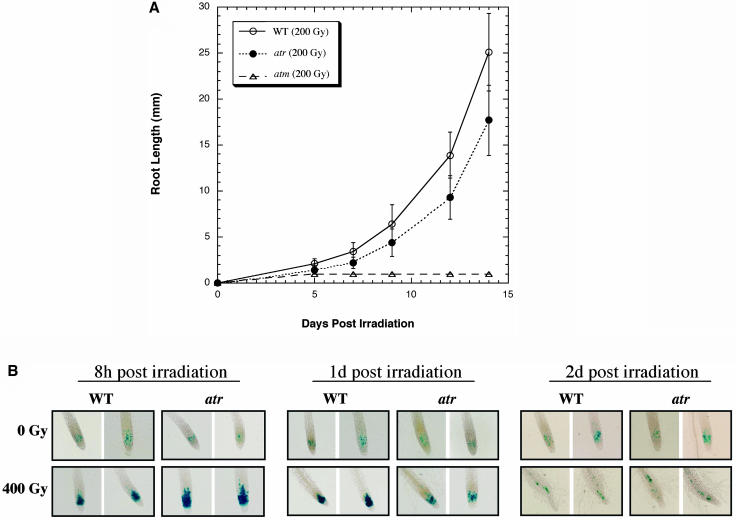

Figure 4.

Root Growth and Cell-Cycle Arrest Phenotypes of γ-Irradiated Wild-Type and atr Plants.

(A) Wild-type, atm, and atr seeds were γ-irradiated at a dose of 200 Gy. The seeds were immediately germinated on MS agar plates, and root growth was measured for 2 weeks. No-irradation controls grew as described (Garcia et al., 2003) and as in Figure 5D.

(B) Five-day-old wild-type and atr seedlings containing the PcyclinB1:GUS fusion construct (as described in the text and Figure 6) were γ-irradiated with 400 Gy, and individual wild-type and atr plants were harvested at 8 h, 1 d, and 2 d time points for GUS staining (n > 12). Two representative examples from each treatment are shown.

To determine the role of Arabidopsis ATR as a cell-cycle checkpoint regulator in response to γ-irradiation, we established homozygous wild-type and atr mutant lines carrying a cyclinB1 promoter coupled to β-glucuronidase (PcyclinB1:GUS) reporter construct. This construct harbors a GUS gene fused to a mitotic destruction sequence and a cyclinB1 promoter (Colon-Carmona et al., 1999). The GUS fusion gene is expressed upon entry into G2 (via the cyclinB1 promoter), and the fusion protein is degraded just before anaphase during mitosis. GUS-positive cells stain blue in G2/early M, allowing us to visually monitor the progression of the cell cycle in root meristems (Preuss and Britt, 2003). To determine G2-specific arrest (versus post-G2 mitotic arrest), we further stained root tips with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) to visualize mitotic nuclei. In response to 400 Gy of γ-radiation, atr mutants showed only a slightly altered cell-cycle response when compared with the wild type; both wild-type and atr meristematic cells arrest in G2 (DAPI staining revealed no accumulation of mitotic figures) but differ slightly in the timing of the response. For instance, at 8 h postirradiation, atr root tips accumulated more G2 cells versus the wild type, but at 1 d postirradiation the root tips accumulated less G2 cells versus the wild type (Figure 4B). This suggests that Arabidopsis ATR is not absolutely required for the G2 checkpoint response to acute doses of γ-radiation but does influence its rate of induction and persistence.

Arabidopsis atr Mutants Are Hypersensitive to Replication-Blocking Agents

hsATR, scMec1, and spRad3 deficiencies are also associated with hypersensitivity to replication blocking agents. For example, yeast mec1 mutants fail to undergo the G2 arrest normally induced by stalled replication and instead proceed directly into mitosis. Consequently, mutant cells accumulate single-strand gaps and double-strand breaks, leading to cell death (Weinert et al., 1994). In animals, this failure to arrest induces apoptosis (Brown and Baltimore, 2000; Cortez et al., 2001). To determine whether ATR is required for plant cell-cycle responses to replication blocks, we challenged wild-type and homozygous atr mutant plants with the replication-blocking agents HU (1 mM), aphidicolin (12 μg/mL), and UV-B light. All of these agents inhibit replication in fundamentally different ways. HU inhibits RNR, thus depleting available dNTPs for DNA polymerases. Aphidicolin is an inhibitor of the replicative DNA polymerases δ and ɛ, and UV-B light creates physical replication blocks (e.g., cyclobutane pyrimidine dimers) in DNA. We chose to focus our analysis on root meristems because we and others (Wiedemeier et al., 2002) found that both HU and aphidicolin inhibit root growth in wild-type plants, suggesting that these agents are absorbed by the root. We germinated wild-type and homozygous atr seeds on control MS agar plates or on plates containing either HU or aphidicolin, selecting a dose of each agent that had mild but perceptible effects on growth of the wild-type root. Both the wild type and atr grew at very similar rates on control plates. On plates containing 1 mM HU, wild-type root growth was reduced ∼40%, whereas the atr root growth was reduced >95% (Figures 5A and 5D) and produced abnormally long root hairs that were densely clustered at the root tip. Moreover, lateral root growth initiated much earlier in atr on HU plates compared with control plates. The shoot was reduced in size and produced anthocyanins (stress-induced pigments), perhaps as an indirect effect of the lack of root growth. The same differences between the wild type and atr (40% versus >95% growth inhibition, overproduction of root hairs and lateral roots) were observed when germinated on plates containing 12 μg/mL of aphidicolin or when 5-d-old seedlings were transferred to plates containing HU or aphidicolin, starting ∼2 d after transfer (Figures 5C and 5D). Furthermore, chronic doses of UV-B light had a similar phenotypic effect on atr roots compared with the wild type (Figure 5B); the mutant was also retarded (to a lesser extent at this dose) in its root growth and formed root hairs at the tip of the root. Thus, three treatments that block replication but differ in the mechanism of inhibition produced similar gross phenotypic effects in atr roots.

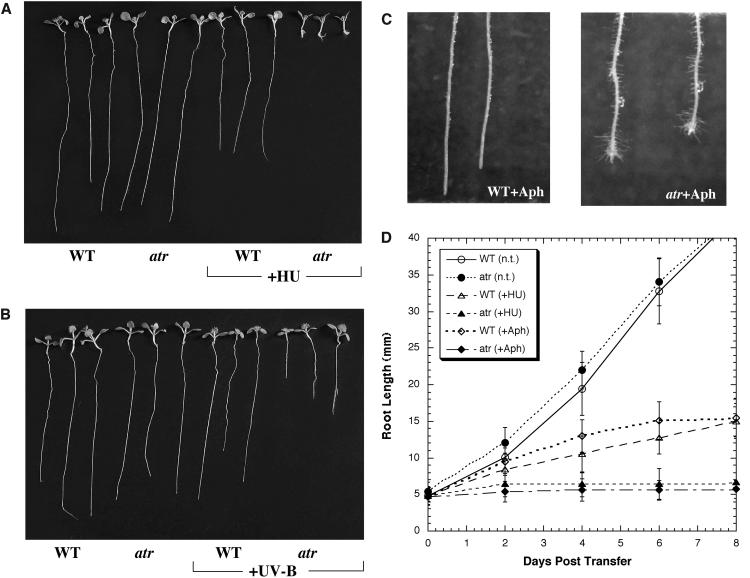

Figure 5.

Phenotypes of atr Challenged with HU, Aphidicolin, or UV-B Light.

(A) Wild-type and atr seeds were germinated on MS plates or MS plus 1 mM HU and grown for 3 weeks.

(B) Wild-type and atr seeds were germinated on MS plates and grown for 3 weeks in the presence or absence of UV-B light (see Methods).

(C) Wild-type and atr seeds were germinated on MS plates and grown for 5 d and then transferred to plates containing 12 μg/mL of aphidicolin (Aph) for 5 d.

(D) Five-day-old wild-type and atr seedlings were grown as above in the presence or absence (n.t., no treatment) of HU or aphidicolin (Aph). However, to make a more direct comparison of the effects of HU versus aphidicolin, we employed concentrations of HU and aphidicolin that inhibited wild-type root growth by ∼40% for both treatments, in this case, 1 mM HU and 12 μg/mL of aphidicolin. We measured root growth (n > 30) from each treatment for 8 d after transfer. Standard deviations are shown as error bars.

AtATR Regulates a G2 Checkpoint in Response to Replication Blocks

Mec1 and ATR are required for the G2 checkpoint response to replication blocks in fungi and mammals, respectively (Melo and Toczyski, 2002). To determine whether ATR performs a similar function in plants, we GUS and DAPI stained homozygous wild-type and atr mutant lines carrying the PcyclinB1:GUS reporter construct (described above) after growth on HU and aphidicolin. As shown in Figure 6, the wild type and atr displayed typical patterns of PcyclinB1:GUS expression on control plates (∼10 to 20 blue cells per root tip), representing the fraction of G2/early M cells present during normal growth. By contrast, the meristematic cells of aphidicolin treated wild-type plants displayed a substantial increase in the number of PcyclinB1:GUS-expressing cells and perhaps in the density of their staining (Figure 6). Using DAPI staining to visualize mitotic nuclei, we observed no significant aphidicolin-induced accumulation of mitotic figures in either wild-type or atr meristematic cells, thus ruling out post-G2 mitotic arrest as a likely cause for the PcyclinB1:GUS accumulation. This indicates that the dividing cells of wild-type plants experiencing aphidicolin-induced replicational stress spend a greater fraction of their cell cycle in G2 and that atr plants are defective in this G2 arrest (Figure 6).

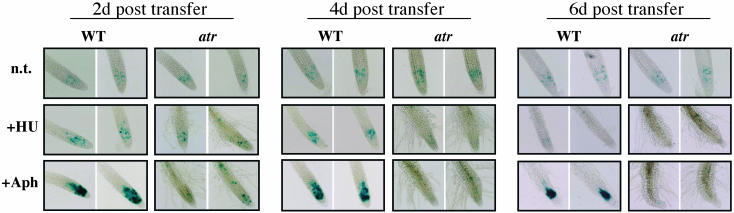

Figure 6.

GUS Staining of Root Tips.

Five-day-old wild-type and atr-3 seedlings (carrying PcyclinB1:GUS) were transferred to aphidicolin (Aph), or HU, or control (n.t.) plates, and root growth was measured every other day after transfer for 8 d (Figure 5D). Individual wild-type and atr plants were harvested at each time point for GUS staining of root tips. Wild-type and atr were grown for 5 d on MS plates and then transferred to control plates or to plates containing 1 mM HU or 12 μg/mL of aphidicolin. These experiments were repeated several times with very similar results; thus, representative pictures are shown. GUS stained root tips from 2, 4, and 6 d after transfer are shown. At least 12 individual plants were harvested and stained at each treatment and time point. Two representative examples are shown for each treatment.

In contrast with the aphidicolin response, HU did not induce G2-phase arrest in wild-type roots. In fact, a decline in the fraction of G2 cells was observed from day 4 to 6 (as measured by the lack of PcyclinB1:GUS staining; Figure 6). The cells are presumably arresting in G1- or S-phase because no increase in mitotic figures was observed via DAPI staining. This response also occurred in atr root meristems but appeared to be slightly accelerated.

To confirm the PcyclinB1:GUS analysis, we employed semiquantitative RT-PCR, with primers specific to the cyclinB1 gene (which does not amplify the PcyclinB1:GUS transcript), on untreated, HU-, or aphidicolin-treated wild-type and atr root tips. As shown in Figure 7, cyclinB1 gene expression is reduced ∼20% (relative to untreated control root tips) in the wild type when grown in the presence of HU but is elevated nearly threefold in the presence of aphidicolin, consistent with our PcyclinB1:GUS experimental conclusion that HU induces G1- or S-phase arrest and aphidicolin induces G2 arrest. Furthermore, aphidicolin-treated atr root tips display no enhancement of cyclinB1 transcript in response to aphidicolin, again suggesting the lack of G2 arrest in atr.

To distinguish between G1- or S-phase arrest in wild-type HU-treated roots, we employed RT-PCR analysis of the S-phase specific gene Histone H4. In plants, the expression of Histone H4 has been shown to be strongly induced upon entry into S-phase and maintained through G2 (Reichheld et al., 1995; Menges and Murray, 2002). If HU induces S-phase arrest (e.g., in wild-type root tips), we would predict a concomitant increase in S-phase–specific gene expression. Likewise, G1-phase arrest would predict a concomitant decrease in S-phase–specific gene expression. As shown in Figure 7, Histone H4 expression is reduced in HU-treated wild-type root tips and elevated in aphidicolin-treated wild-type root tips, suggesting G1- and G2-phase arrest, respectively. In the atr mutant, Histone H4 expression is elevated in the untreated root tips but is drastically reduced in the HU- and aphidicolin-treated root tips. This suggests that the atr mutant, although phenotypically normal in root growth, induces some S-phase arrest (cyclinB1 is not induced) under standard growth conditions but in the presence of replication blocking agents, arrests and/or exits the cell cycle in G1.

Altogether, these data suggest that two independent checkpoints are responsible for the arrest phenotypes observed in the wild type versus atr: an aphidicolin-induced G2 checkpoint that is AtATR dependent and a HU-induced G1 checkpoint.

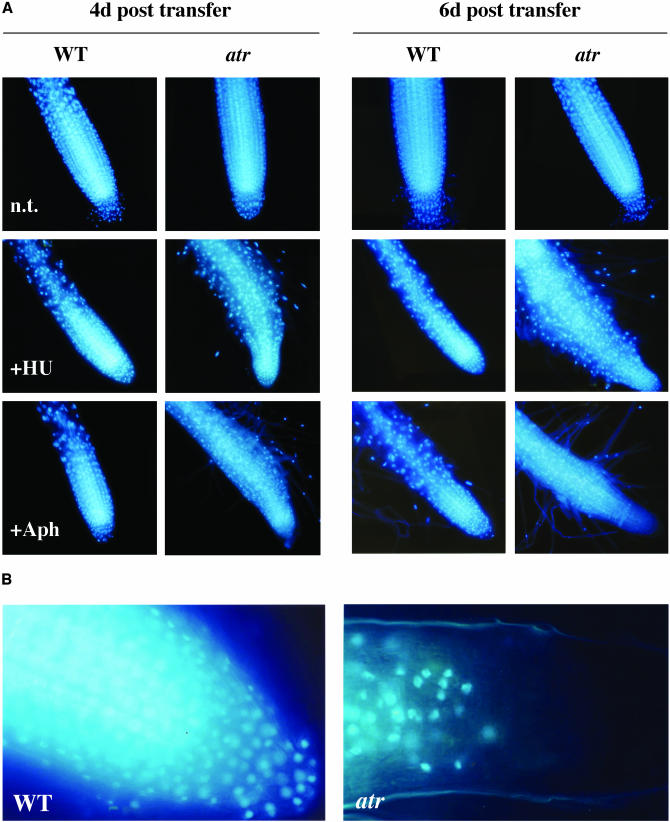

Aphidicolin, but Not HU, Induces Cell Death in atr

To further characterize the different cellular responses to HU and aphidicolin, we DAPI stained wild-type and atr root tips (time points and treatments as above) to observe the integrity of the nuclei. As seen in Figure 8A, wild-type roots had very organized meristems with round and slightly diffuse nuclei, and they retained this morphology on HU and aphidicolin. However, atr exhibited different cellular morphologies on both HU and aphidicolin. The cell files of atr meristems grown on HU were disorganized and the cells enlarged, but the nuclei were similar in appearance to the wild type (round and slightly diffuse). All cells up to the root cap had a defined nucleus (Figure 8A). The meristems of atr grown on aphidicolin also were disorganized, but the appearance of the nuclei differed from that observed in either the wild type (all conditions) or atr grown on HU. Starting on day 4, the meristematic nuclei near the tip became condensed, and DAPI staining was reduced relative to atr grown on HU or the wild type (all conditions). By day 6, most cells in the meristematic zone of aphidicolin-treated roots had completely lost their nuclei, leaving only a blue haze (Figures 8A and 8B). This indicates that atr mutant cells undergo nuclear degradation (cell death) when treated with aphidicolin, but not HU, at dose levels of both agents that inhibit wild-type growth by ∼40%. Although some cell death also can be seen at higher doses of HU (data not shown), these higher doses inhibited wild-type growth >95%. This suggests that (1) the aphidicolin-induced AtATR-dependent G2 arrest plays a critical role in protecting the genome, and (2) that additional factors, such as the G1 arrest induced by HU, may rescue atr meristems from massive genomic instability induced by progression through M-phase in the absence of complete replication.

Figure 8.

DAPI-Stained Root Tips from Wild-Type and atr Grown as in Figure 6.

(A) Shown are root tips day 4 and day 6 after transfer.

(B) Close-up of 6 d after transfer to aphidicolin wild-type (left) and atr (right) DAPI-stained root tips.

DISCUSSION

ATR plays a central role in the cell's response to DNA damage by activating cell-cycle checkpoints that allow time for DNA repair. We have shown that Arabidopsis atr mutants are viable and normal under standard growth conditions but are hypersensitive to replication blocks and mildly sensitive to γ-radiation. Furthermore, we have shown that AtATR is required for the G2-phase checkpoint in response to replication blocks but is not absolutely required in the G2-arrest response to double-strand breaks (using acute doses of γ-radiation). The differences seen in response to HU, aphidicolin, and γ-irradiation suggest that additional checkpoints also play important roles in the cell-cycle and cell-death phenotypes observed.

AtATR Plays a Relatively Minor Role in γ-Resistance

At 400 Gy of γ-radiation, the atr mutant is similar to the wild type in root growth and its ability to recover from γ-radiation treatments. By contrast, atm is not able to recover from γ-radiation doses as low as 80 Gy (Garcia et al., 2003). This suggests that AtATR plays a relatively minor role in γ-resistance versus AtATM in plants. Human cell lines expressing a dominant-negative kinase mutant of ATR have been used to characterize the relative contributions of ATR and ATM to γ-resistance (Cliby et al., 1998; Wright et al., 1998). These experiments have clearly demonstrated that ATR is involved in γ-resistance, but independent studies employing these approaches have yielded inconclusive results in the relative contributions of ATR and ATM to γ-resistance (Jimenez et al., 1992; Cliby et al., 1998; Wright et al., 1998).

The cell-cycle arrest phenotypes of atr in comparison to the wild type suggest that the mild γ-sensitivity of atr is probably not an absolute effect of an abrogated checkpoint in G2; both the wild type and atr display an accumulation of GUS within the meristem consistent with G2 arrest, although with slightly different kinetics. Although we do not yet know if AtATM contributes to the γ-induced G2 checkpoint, it is possible that AtATR and AtATM play partially redundant roles in this response. In this case, AtATM may partially compensate for AtATR deficiency throughout all or part of the cell cycle. In mammalian cells, experiments employing conditional knockout (null) alleles of ATR have demonstrated that G2 arrest is abrogated in response to γ-radiation, indicating that ATR is necessary for the G2 checkpoint in response to double-strand breaks (Brown and Baltimore, 2003). However, these experiments used synchronized cells, irradiating cells during S/G2-phase and then assaying for progression into M-phase. Because the acute doses of γ-radiation used here create double-strand breaks in all phases of the cell cycle, it is possible that ATR is primarily activated during a specific phase of the cell cycle (e.g., S-phase) in response to double-strand breaks (for review, see Abraham, 2001). In this scenario, only a fraction of the meristematic cells (most are in G1) with DNA damage would invoke ATR-dependent G2 arrest, such as cells progressing through S-phase. G1 cells that acquire damage might be activated for G2 arrest through an ATR-independent mechanism, progress through S-phase, and then arrest in G2-phase. It will be interesting to determine the cell-cycle responses to acute and chronic doses of γ-radiation in atm and atr atm double mutant plants in comparison to atr. Nonetheless, our preliminary results suggest that plants may regulate the G2-phase checkpoint in response to γ-radiation differently than animals.

AtATR Responses to Replication Blocks

It is clear from both yeast and animal studies that ATR plays a critical role in the G2 checkpoint response to replication blocks. Many of these studies have employed HU and/or aphidicolin as model agents for replication blocks. HU or aphidicolin treatment of wild-type yeast and animals cells (at concentrations that allow S-phase progression) results in G2 arrest. In ATR-deficient mammalian cells, progression into mitosis (without G2 delay) leads to caspase-independent chromosomal fragmentation, which in turn induces an apoptotic response (Brown and Baltimore, 2000). We have shown that atr plants are hypersensitive to the growth-inhibitory effects of HU and aphidicolin. The G2 arrest (as measured by PcyclinB1:GUS) in wild-type root meristems on aphidicolin and the concomitant lack of G2 arrest in atr root meristems indicates that ATR is required for the G2-phase checkpoint response to replication blocks. The lack of wild-type G2 arrest in response to HU, however, was surprising. Because the fundamental difference between HU and aphidicolin in blocking S-phase replication is that HU-treated cells are reduced in dNTPs, this implies that the G1 arrest is activated by a novel checkpoint responsive to low dNTPs. Previous studies in human cells demonstrated a p53-dependent G1 arrest in response to low ribonucleotide levels, but not deoxynucleotide levels (Linke et al., 1996). The response to low dNTPs may help to prevent plant cells from initiating S-phase DNA replication in the absence of sufficient dNTP pools. Because phosphate is a relatively immobile and limiting nutrient in soil (Abel et al., 2002), this checkpoint could also represent a plant-specific response that helps direct root growth away from phosphate-depleted regions of soil, eliminating growth of root meristems in phosphate-depleted regions, while promoting the formation of other lateral root meristems elsewhere along the root.

The cell death observed in atr in response to aphidicolin, but not HU, suggests that the G1 (dNTP-dependent) checkpoint may rescue atr from cell death. However, atr mutants are hypersensitive to the effects of HU on the growth of the root, a fact that may appear paradoxical given the hypothesis that this line is proficient in the G1 arrest induced by this agent. For this reason, we remind the reader that the HU-treated wild-type roots are growing, though at a slightly reduced rate. In other words, the cells are progressing through the entire cell cycle, although they are spending a relatively longer fraction of that cycle in G1. We thus propose the following model for Arabidopsis cell-cycle checkpoint regulation in response to HU. HU treatment induces two independent checkpoints in Arabidopsis: one in G1 in response to low dNTPs (AtATR independent) and one in G2 in response to replication blocks (AtATR dependent). HU-treated wild-type and atr meristematic cells arrest in G1 in response to low dNTP pools, thus retarding their entry into S-phase. The G1 checkpoint is eventually relieved after enough dNTPs accumulate to permit entry into S-phase, and some fraction of cells leak through into S-phase. The resulting S-phase–induced depletion of dNTPs in the presence of HU then results in a requirement for AtATR-dependent G2 checkpoint activation. The inability of atr to activate this G2 checkpoint results in defective DNA replication and meristematic failure.

By contrast, aphidicolin-treated atr cells do not invoke the G1 checkpoint because they have normal levels of dNTPs and enter S-phase without delay. atr cells then fail to arrest in G2 and proceed into mitosis with incompletely replicated genomes, perhaps to a much larger degree than HU-treated atr cells. This results in a majority of the daughter G1 cells having an intolerable amount of single-strand gaps and double-strand breaks, leading to meristematic failure and cell death.

The cell death seen in atr was unexpected. Mutants in DNA repair/maintenance genes in Arabidopsis, such as DNA ligase IV, ERCC1, and telomerase, do not exhibit obvious cell death, even in response to treatment with DNA damaging agents (Riha et al., 2001; Friesner and Britt, 2003; Hefner et al., 2003). A prevailing hypothesis is that plants, which have no p53 homolog, lack DNA damage–induced cell death (apoptosis). We believe the atr response to aphidicolin might be an example of programmed cell death, as indicated by the fact that all cells in the root tip die, including normally nondividing cells (e.g., epidermal cells), suggesting that the signal for the cell death is diffusible. Alternatively, it is possible that the cells surrounding the dying meristem are recruited to reconstitute the missing meristem, and this induction of the cell cycle induces their death. In this case, death might simply be the direct result of the chromosomal fragmentation induced by progression through M-phase with an incompletely replicated genome. In any event, it is clear that replication-induced checkpoints play an important role in protecting cells from the consequences of replicational stress.

AtATR-Dependent and AtATR-Independent Regulation of AtRNR1 Transcription

The regulation of RNR in yeast is well defined and involves transcriptional and posttranslational control (i.e., inhibitory protein–protein interactions, modification of protein localization, and allosteric regulation). For instance, the yeast RNR1 (large subunit) gene is expressed during vegetative growth, upregulated in late G1 and early S, and further upregulated in response to DNA damage (Elledge et al., 1992). The expression patterns of several RNR genes have been characterized in tobacco, including an RNR1-like gene (Chabouté et al., 1998, 2002). The reduced level of RNR1 transcript (Figure 3) we observed in atr versus the wild type, in the absence of DNA damaging agents or with chronic UV-B light, suggests that RNR1 is transcriptionally maintained in Arabidopsis through both AtATR-dependent and AtATR-independent mechanisms. Our analysis employing HU on whole seedlings (Figure 3) further indicate that RNR1 is regulated transcriptionally, and independently of AtATR, via a feedback-type mechanism that boosts RNR1 transcripts when dNTPs are low.

The rapid reduction of AtRNR1 transcript in response to acute doses of UV-B in wild-type and atr plants suggests an additional mode of transcriptional regulation for AtRNR1 in response to DNA damage that is independent of AtATR. In yeast, RNR upregulation in response to DNA damage is rapid, occurring within 30 min after treatment (Elledge and Davis, 1990; Elledge, 1993). It was thus surprising that under our experimental conditions, an acute dose of UV-B light caused a rapid reduction of AtRNR1 transcript within 2 h after UV-B treatment, followed by a return to no-treatment control levels within 6 h after UV-B treatment. This response could represent a process by which inhibition of AtRNR expression leads to low dNTP levels and a concomitant arrest of the cell cycle during DNA damage, possibly through the G1 checkpoint described above. A decrease in RNR expression might also be expected to inhibit the potentially mutagenic actions of bypass polymerases, which require high levels of dNTPs for activity (Johnson et al., 2001; Chabes et al., 2003). One plausible model for this mode of regulation would be that immediately after experiencing acute DNA damage, cells initially try to eliminate as much of the damage as possible via error-free pathways. Initial downregulation of dNTPs would inhibit the inherently mutagenic bypass polymerases and contribute to the arrest of the cell cycle. Return to normal levels of dNTPs then allows the cell cycle to progress and enables the cell to utilize bypass polymerases as needed to complete replication. This model is suggestive of the SOS response in Escherichia coli, wherein error-free repair mechanisms are induced early, and error-prone translesion synthesis is induced later (Goodman and Woodgate, 2000; Rangarajan et al., 2002) in response to acute induction of DNA damage.

AtATR Is Required for the Completion of Meiosis in the Absence of AtATM

Given the partial sterility of atm mutant plants and nonsterility of atr, the observation of complete sterility of the atr atm double mutant suggests that ATR can partially complement ATM function during meiosis. Although it is not clear whether ATR has a distinct meiotic function or if ATR is simply filling in for the lack of ATM (or vice versa), our experiments do at the very least suggest that ATR is present and functional during meiosis in Arabidopsis. In mammalian cells, in situ localization studies have shown that both ATM and ATR are localized to meiotic chromosomes (Keegan et al., 1996; Moens et al., 1999). Further studies using atr and atm single and double mutant plants will allow us to better understand the role of ATR in plant meiosis, possibly leading to additional insights into ATR function during animal meiosis.

Conclusions

We have shown that plants encode an ortholog of ATR and that its role in G2 checkpoint regulation is similar in many respects to its yeast and mammalian counterparts. The presence of ATM and other downstream effectors of the cell cycle and DNA repair, including BRCA1 (Lafarge and Montane, 2003) and a putative CHK1 (S.B. Preuss, K. Culligan, and A. Britt, unpublished data) for example, further suggest that G2 cell-cycle checkpoint responses to DNA damage and replication blocks are regulated in a similar fashion in plants and animals. This is not to say that plant responses to DNA damage and replication blocks are identical to that of animals; perhaps the most significant difference between plants and animals is the lack of a p53-dependent programmed cell death response to persisting DNA damage. Plants may encode an analogous pathway for the degradation of hopelessly compromised cells, as evidenced by the cell death observed in atr, but this is probably a response to massive disruption of DNA replication coupled to uninhibited progression through the cell cycle. Perhaps because plants do not die from cancer, a cell death response to minor levels of DNA damage (such as those that occur spontaneously and persist in repair defective mutants) would be counteradaptive. Because of this insensitivity (versus animals) to persisting DNA damage, plants may ultimately prove to be a robust model system for the study of many fundamental processes in cell-cycle regulation and DNA repair pathways in eukaryotes (for review, see Hays, 2002).

METHODS

Isolation of Mutants

The atr-1 allele (ecotype Ws) was isolated from the Arabidopsis Knockout Facility as described (Krysan et al., 1999). The atr-2 allele (ecotype Columbia; SALK_032841) was identified using the Salk SIGnAL Web site (http://signal.salk.edu), and the seeds obtained from the ABRC. The atr-3 allele (ecotype Ws) was identified using the FLAG database (Genoplante; http://genoplante-info.infobiogen.fr/).

Growth of Arabidopsis

For standard growth conditions, seeds were sown on 1× MS (GIBCO, Cleveland, OH) phytagel (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) agar, pH 5.8, and grown under cool-white lamps filtered through Mylar at an intensity of 100 to 150 μmol/m2/s with a 24-h day light cycle at 21°C. HU (Sigma; 500 mM stock in water) and aphidicolin (ICN Biomedicals, Basingstoke, UK; 20 μg/mL stock in DMSO) were added to MS plates (as above) to concentrations described in the text and figure legends. For experiments using aphidicolin, all control and HU plates contained an equivalent amount (0.05%) of DMSO to allow direct comparison.

UV-B and γ-Irradiation of Arabidopsis

For chronic doses of UV-B light, plants were sown on MS plates and grown with a 24-h light cycle under cool-white lamps, supplemented with UV-B light using a medium wave UV-B lamp (Spectronics, Westbury, NY; peak intensity 312 nm) filtered through three sheets of cellulose acetate (Golden State Plastics, Sacramento, CA; thickness 0.12 mm) to eliminate the UV-C (<280 nm) fraction of emitted light. The cellulose acetate was replaced every 3 d. The dose rate of UV-B was 2.5 J/s/m2. For acute doses of UV-B, 5-d-old seedlings were irradiated with a UV transilluminator (Fisher, Houston, TX), peak output at 305 nm, filtered through a single cellulose acetate sheet. UV-B intensities were measured with a UV-B radiometer with a peak response at 310 nm and a 50% response at 280 and 340 nm (UV Products, San Gabriel, CA). For γ-radiation experiments, Arabidopsis seeds and plants were irradiated using a Cs137 source (Institute of Toxicology and Environmental Health, University of California, Davis). Seeds were imbibed in water at 4°C for 3 d, irradiated, and then immediately placed on MS agar plates for germination and placed in the growth chamber; plants were grown on MS plates (for 5 d), irradiated, and then immediately returned to the growth chamber.

Preparation of RNA and RNA Gel Blotting

Total RNA was prepared from 7-d-old seedlings using an RNeasy plant mini kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). RNA was blotted onto positively charged membranes (BriteStar-Plus; Ambion, Austin, TX) and probed with a 32P radioactively labeled AtRNR1 (GenBank AF092841) cDNA fragment. This 761-bp fragment was generated with PCR primers RNR1 (5′-AAGAATGGAGTGAGGAACTCTC-3′) and RNR3 (5′-CTCAAGCAACATTAAGCATTAG-3′). The resulting bands were visualized on a Storm 860 PhosphorImager and quantified using ImageQuant software (Molecular Dynamics, Sunnyvale, CA).

Semiquantitative RT-PCR

Wild-type and atr Arabidopsis plants were sown on MS agar plates, grown for 5 d, then transferred to MS plates (n.t.), MS plates plus 1 mM HU (+HU), or MS plates plus 12 μg/mL of aphidicolin (+Aph) for 4 d of additional growth. All plants were verified for their respective phenotypes described above. Approximately 1 to 2 mm of root tips, from >200 individual plants of each treatment, were excised and pooled together for RNA extraction (RNeasy mini-prep; Qiagen). RNA samples were DNase treated (DNase set; Qiagen) and quantified. To produce cDNA for RT-PCR, 2 μg of total RNA from each condition described above was reverse transcribed, employing random hexamer primers, with a Superscript first-strand synthesis kit (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA) in a 40-μL reaction according to the manufacturers protocol. RT-PCR was performed in 50 μL reactions using Ex-Taq polymerase (Takara Bio, Otsu, Shiga, Japan), 2 μL of cDNA, and the following gene-specific primers: eIF4A-1 (5′-CTCTCGCAATCTTCGCTCTTCTCTTT-3′), eIF4A-5 (5′-TCATAGATCTGGTCCTTGAAAC-3′), CycB1-2 (5′-GTCGCTTTCTTCTTAGTAGCCTTCT-3′), CycB1-6 (5′-GGCCTCCATTCACTCTCAACAG-3′), H4-5 (5′-ATGTCTGGTCGTGGAAAGGGAG-3′), H4-8 (5′-ACCAAATTGCGTGTTTCCATTG-3′), cATR-1 (5′-CAGCGCCCAAAGAAGATCATTC-3′), and cATR-3 (5′-GGCCCGCTGAGCATGTGGGTTC-3′). All primers (except Histone H4) spanned intron-exon boundaries to eliminate the possibility of amplifying contaminating genomic DNA. PCR-cycle parameters for all primer pairs were 20 s at 94°C, 20 s at 62°C, and 45 s at 72°C. Primer pairs were first tested for log-linear amplification using 18, 21, 24, 27, and 30 cycles of PCR. The optimized number of cycles for each primer pair was: eIF4A, 23 cycles; cycB1, 27 cycles; Histone H4, 29 cycles; and ATR, 27 cycles. PCR products of ethidium bromide–stained gels were quantified using ImageQuant software as above.

GUS and DAPI Staining

GUS staining was performed as described (Jefferson et al., 1987; Preuss and Britt, 2003). DAPI staining was performed by fixing roots in a solution of ethanol and acetic acid (3:1). T he roots were then washed two times in PBS, pH 7.4, and stained in PBS containing 2.5 μg/mL of DAPI (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) for 20 min. The roots were then washed in PBS two times and mounted on slides in 50% glycerol. Slides were visualized on a Zeiss Axiophot microscope, and photographs were taken with a Zeiss MC100 camera. DAPI staining was visualized with a standard UV fluorescence filter set.

Sequence data from this article have been deposited with the EMBL/GenBank data libraries under accession numbers AB040133 and AF092841.

Acknowledgments

We thank Ying Peng for assistance in isolating the atr atm double mutant and Cheryl Whistler, Joanna Friesner, and Eli Hefner for critical reading of the manuscript. We also thank the Arabidopsis Knockout Facility (University of Wisconsin, Madison) and the SIGnAL (Salk Institute) and FLAG databases for providing T-DNA knockout resources. This work was supported by a USDA postdoctoral fellowship (2001-01860) to K.M.C. and a National Science Foundation Grant (MCB-9983142) to A.B.B.

The author responsible for distribution of materials integral to the findings presented in this article in accordance with the policy described in the Instructions for Authors (www.plantcell.org) is: Kevin M. Culligan (kmculligan@ucdavis.edu).

Article, publication date, and citation information can be found at www.plantcell.org/cgi/doi/10.1105/tpc.018903.

References

- Abel, S., Ticconi, C., and Delatorre, C. (2002). Phosphate sensing in higher plants. Physiol. Plant 115, 1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abraham, R. (2001). Cell cycle checkpoint signaling through the ATM and ATR kinases. Genes Dev. 15, 2177–2196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown, E., and Baltimore, D. (2003). Essential and dispensable roles of ATR in cell cycle arrest and genome maintenance. Genes Dev. 17, 615–628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown, E.J., and Baltimore, D. (2000). ATR disruption leads to chromosome fragmentation and early embryonic lethality. Genes Dev. 15, 397–402. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chabes, A., Clement, B., Domkin, V., Zhao, X., Rothstein, R., and Thelander, L. (2003). Survival of DNA damage in yeast directly depends on increased dNTP levels allowed by relaxed feedback inhibition of ribonucleotide reductase. Cell 112, 391–401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chabouté, M., Combettes, B., Clement, B., Gigot, C., and Philipps, G. (1998). Molecular characterization of tobacco ribonucleotide reductase RNR1 and RNR2. Plant Mol. Biol. 38, 797–806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chabouté, M.E., Clement, B., and Philipps, G. (2002). S phase and meristem-specific expression of the tobacco RNR1b gene is mediated by an E2F element located in the 5′ leader sequence. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 17845–17851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cliby, W., Roberts, C., Cimprich, K., Stringer, C., Lamb, J., Schreiber, S., and Friend, S. (1998). Overexpression of a kinase-inactive ATR protein causes sensitivity to DNA-damaging agents and defects in cell cycle checkpoints. EMBO J. 17, 159–169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colon-Carmona, A., You, R., Haimovitch-Gal, T., and Doerner, P. (1999). Spatio-temporal analysis of mitotic activity with a labile cyclin-GUS fusion protein. Plant J. 20, 503–508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cortez, D., Guntuku, S., Qin, J., and Elledge, S.J. (2001). ATR and ATRIP: Partners in checkpoint signaling. Science 294, 1713–1716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crowley, D.J., and Courcelle, J. (2002). Answering the call: Coping with DNA damage at the most inopportune time. J. Biomed. Biotechnol. 2, 66–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Culligan, K.M., Meyer-Gauen, G., Lyons-Weiler, J., and Hays, J.B. (2000). Evolutionary origin, diversification and specialization of eukaryotic MutS homolog mismatch repair proteins. Nucleic Acids Res. 28, 463–471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Klein, A., Muijtjens, M., van Os, R., Verhoeven, Y., Smit, B., Carr, A., Lehmann, A., and Hoeijmakers, J. (2000). Targeted disruption of the cell-cycle checkpoint gene ATR leads to early embryonic lethality in mice. Curr. Biol. 10, 479–482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elledge, S., Zhou, Z., and Allen, J.B. (1992). Ribonucleotide reductase: Regulation, regulation, regulation. Trends Biochem. Sci. 17, 119–123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elledge, S.J. (1993). DNA damage and cell cycle regulation of ribonucleotide reductase. Bioessays 15, 333–339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elledge, S.J., and Davis, R.W. (1990). Two genes differentially regulated in the cell cycle and by DNA-damaging agents encode alternative regulatory subunits of ribonucleotide reductase. Genes Dev. 4, 740–751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friesner, J.D., and Britt, A.B. (2003). Ku80- and DNA ligase IV-deficient plants are sensitive to ionizing radiation and defective in T-DNA integration. Plant J. 34, 427–440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia, V., Bruchet, H., Camescasse, D., Fabienne, G., Bouchez, D.L., and Tissier, A. (2003). AtATM is essential for meiosis and the somatic response to DNA damage in plants. Plant Cell 15, 119–132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman, M.F., and Woodgate, R. (2000). The biochemical basis and in vivo regulation of SOS-induced mutagenesis promoted by Escherichia coli DNA polymerase V (UmuD'2C). Cold Spring Harb. Symp. Quant. Biol. 65, 31–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hays, J. (2002). Arabidopsis thaliana, a versatile model system for study of eukaryotic genome-maintenance functions. DNA Repair 1, 579–600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hefner, E.A., Preuss, S.B., and Britt, A.B. (2003). Arabidopsis mutants sensitive to gamma radiation include the homolog of the human repair gene ERCC1. J. Exp. Bot. 54, 669–680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang, M., Zhou, Z., and Elledge, S. (1998). The DNA replication and damage checkpoint pathways induce transcription by inhibition of the Crt1 repressor. Cell 94, 595–605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jefferson, R., Kavanagh, T.A., and Bevan, M.W. (1987). GUS fusions: Beta-glucuronidase as a sensitive and versatile gene fusion marker in higher plants. EMBO J. 6, 3901–3907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jimenez, G., Yucel, J., Rowley, R., and Subramani, S. (1992). The rad3+ gene of Schizosaccharomyces pombe is involved in multiple checkpoint functions and in DNA repair. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 89, 4952–4956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, R., Haracska, L., Prakash, S., and Prakash, L. (2001). Role of DNA polymerase zeta in the bypass of a (6-4) TT photoproduct. Mol. Cell. Biol. 21, 3558–3563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keegan, K.S., et al. (1996). The Atr and Atm protein kinases associate with different sites along meiotically pairing chromosomes. Genes Dev. 10, 2423–2437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krysan, P.J., Young, J.C., and Sussman, M.R. (1999). T-DNA as an insertional mutagen in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 11, 2283–2290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lafarge, S., and Montane, M. (2003). Characterization of the Arabidopsis thaliana ortholog of the human breast cancer susceptibility gene 1:AtBRCA1, strongly induced by X-rays. Nucleic Acids Res. 31, 1148–1155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linke, S., Clarkin, K., Di Leonardo, A., Tsou, A., and Wahl, G. (1996). A reversible, p53-dependent G0/G1 cell cycle arrest induced by ribonucleotide depletion in the absence of detectable DNA damage. Genes Dev. 10, 934–947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melo, J., and Toczyski, D. (2002). A unified view of the DNA-damage checkpoint. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 14, 237–245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menges, M., and Murray, J.A. (2002). Synchronous Arabidopsis suspension cultures for analysis of cell-cycle gene activity. Plant J. 30, 203–212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moens, P.B., Tarsounas, M., Morita, T., Habu, T., Rottinghaus, S., Freire, R., Jackson, S., Barlow, C., and Wynshaw-Boris, A. (1999). The association of ATR protein with mouse meiotic chromosome cores. Chromosoma 108, 95–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nyberg, K.A., Michelson, R.J., Putnam, C.W., and Weinert, T.A. (2002). Toward maintaining the genome: DNA damage and replication checkpoints. Annu. Rev. Genet. 36, 617–656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preuss, S.B., and Britt, A.B. (2003). A DNA damage induced cell cycle checkpoint in Arabidopsis. Genetics 164, 323–334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rangarajan, S., Woodgate, R., and Goodman, M.F. (2002). Replication restart in UV-irradiated Escherichia coli involving pols II, III, V, PriA, RecA and RecFOR proteins. Mol. Microbiol. 43, 617–628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reichheld, J., Sonobe, S., Clément, B., Chaubet, N., and Gigot, C. (1995). Cell cycle-regulated histone gene expression in synchronized plant cells. Plant J. 7, 245–252. [Google Scholar]

- Riha, K., McKnight, T., Griffing, L., and Shippen, D. (2001). Living with genome instability: Plant responses to telomere dysfunction. Science 291, 1797–1800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sedgwick, P., and Boder, E. (1991). Ataxia-telangiectasia. In Hereditary Neuropathies and Spinocerebellar Atrophies, J.M.B.V. deJong, ed (New York: Elsevier Science Publishing), pp. 347–423.

- Tanaka, H., Arakawa, H., Yamaguchi, T., Shiraishi, K., Fukuda, S., Matsui, K., Takei, Y., and Nakamura, Y. (2000). A ribonucleotide reductase gene involved in a p53-dependent cell-cycle checkpoint for DNA damage. Nature 404, 42–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tibbetts, R.S., and Abraham, R.T. (2000). PI3K-related kinases: Roles in cell cycle regulation and DNA damage responses. In Signalling Networks and Cell Cycle Control: The Molecular Basis of Cancer and Other Diseases, J. Gutkind, ed (Totowa, NJ: Humana Press), pp. 267–301.

- Tibbetts, R.S., Cortez, D., Brumbaugh, K.M., Scully, R., Livingston, D., Elledge, S.J., and Abraham, R.T. (2000). Functional interactions between BRCA1 and the checkpoint kinase ATR during genotoxic stress. Genes Dev. 14, 2989–3002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinert, T.A., Kiser, G.L., and Hartwell, L.H. (1994). Mitotic checkpoint genes in budding yeast and the dependence of mitosis on DNA replication and repair. Genes Dev. 8, 652–665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiedemeier, A., Judy-March, J., Hocart, C., Wasteneys, G.O., Williamson, R., and Baskin, T. (2002). Mutant alleles of Arabidopsis RADIALLY SWOLLEN 4 and 7 reduce growth anisotropy without altering the transverse orientation of cortical microtubules or cellulose microfibrils. Development 129, 4821–4830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright, J., Keegan, K., Herendeen, D., Bentley, N., Carr, A., Hoekstra, M., and Concannon, P. (1998). Protein kinase mutants of human ATR increase sensitivity to UV and ionizing radiation and abrogate cell cycle checkpoint control. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95, 7445–7450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yao, R., Zhang, Z., An, X., Bucci, B., Perlstein, D.L., Stubbe, J., and Huang, M. (2003). Subcellular localization of yeast ribonucleotide reductase regulated by the DNA replication and damage checkpoint pathways. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 100, 6628–6633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, X., Chabes, A., Domkin, V., Thelander, L., and Rothstein, R. (2001). The ribonucleotide reductase inhibitor Sml1 is a new target of the Mec1/Rad53 kinase cascade during growth and in response to DNA damage. EMBO J. 20, 3544–3553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, X., Muller, E.G., and Rothstein, R. (1998). A suppressor of two essential checkpoint genes identifies a novel protein that negatively affects dNTP pools. Mol. Cell 2, 329–340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, X., and Rothstein, R. (2002). The Dun1 checkpoint kinase phosphorylates and regulates the ribonucleotide reductase inhibitor Sml1. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99, 3746–3751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zou, L., and Elledge, S.J. (2003). Sensing DNA damage through ATRIP recognition of RPA-ssDNA complexes. Science 300, 1542–1548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]