Abstract

Systematic reviews comprehensively summarize evidence about the effectiveness of conservation interventions. We investigated the contribution to management decisions made by this growing body of literature. We identified 43 systematic reviews of conservation evidence, 23 of which drew some concrete conclusions relevant to management. Most reviews addressed conservation interventions relevant to policy decisions; only 35% considered practical on-the-ground management interventions. The majority of reviews covered only a small fraction of the geographic and taxonomic breadth they aimed to address (median = 13% of relevant countries and 16% of relevant taxa). The likelihood that reviews contained at least some implications for management tended to increase as geographic coverage increased and to decline as taxonomic breadth increased. These results suggest the breadth of a systematic review requires careful consideration. Reviews identified a mean of 312 relevant primary studies but excluded 88% of these because of deficiencies in design or a failure to meet other inclusion criteria. Reviews summarized on average 284 data sets and 112 years of research activity, yet the likelihood that their results had at least some implications for management did not increase as the amount of primary research summarized increased. In some cases, conclusions were elusive despite the inclusion of hundreds of data sets and years of cumulative research activity. Systematic reviews are an important part of the conservation decision making tool kit, although we believe the benefits of systematic reviews could be significantly enhanced by increasing the number of reviews focused on questions of direct relevance to on-the-ground managers; defining a more focused geographic and taxonomic breadth that better reflects available data; including a broader range of evidence types; and appraising the cost-effectiveness of interventions.

Contribuciones de las Revisiones Sistemáticas a las Decisiones de Manejo

Resumen

Las revisiones sistemáticas resumen integralmente la evidencia sobre la efectividad de las intervenciones de conservación. Investigamos la contribución de las decisiones de manejo hechas por este creciente cuerpo de literatura. Identificamos 43 revisiones sistemáticas de evidencia de conservación, 23 de las cuales hicieron algunas conclusiones concretas relevantes al manejo. La mayoría de las revisiones se dirigían a intervenciones de conservación relevantes a las decisiones políticas; sólo el 35% consideraba intervenciones de manejo sobre-la-causa prácticas. La mayoría de las revisiones cubrieron solo una pequeña fracción de la amplitud geográfica y taxonómica a la que buscaban dirigirse (mediana = 13% de los países relevantes y 16% de los taxones relevantes). La probabilidad de que las revisiones tuvieran por lo menos algunas implicaciones para el manejo tendió a incrementar conforme la cobertura geográfica incrementaba y a declinar conforme aumentaba la amplitud taxonómica. Estos resultados sugieren que la amplitud de una revisión taxonómica requiere de una consideración cuidadosa. Las revisiones identificaron una media de 312 estudios primarios relevantes pero excluyeron 88% de estos por deficiencias en el diseño o fallas para coincidir con otros criterios de inclusión. Las revisiones resumieron en promedio 248 juegos de datos y 112 años de actividad de investigación, pero la probabilidad de que sus resultados tuvieran por lo menos algunas implicaciones para el manejo no incrementaron mientras la cantidad de investigación primaria resumida aumentaba. En algunos casos, las conclusiones fueron elusivas a pesar de la inclusión de cientos de conjuntos de datos y años de actividad de investigación acumulada. Las revisiones sistemáticas son una parte importante del juego de herramientas en la toma de decisiones de conservación, aunque consideramos que los beneficios de las revisiones sistemáticas podrían ser mejorados significativamente al incrementar el número de revisiones centradas en preguntas con relevancia directa a administradores sobre-la-causa; definiendo una amplitud geográfica y taxonómica más enfocada que reflejo los datos disponibles; incluyendo un rango más amplio de tipos de evidencia; y evaluando la efectividad de costo de las intervenciones.

Keywords: conservation management, conservation policy, decision making, environmental evidence, evidence-based conservation, implementation gap, brecha de implementación, conservación basada en evidencias, evidencia ambiental, manejo de conservación, política de conservación, toma de decisiones

Introduction

Despite the aim of conservation science being to inform and guide management (Meffe et al. 2006), decision makers report that it can be difficult and time-consuming to access available science (Fazey et al. 2004; Zavaleta et al. 2008) and that research findings can be challenging to interpret (Pullin & Knight 2005). Debate in the literature and conflicting research findings can also cause managers to mistrust scientific information (Young & Van Aarde 2011). Compounding these challenges, the peer-reviewed literature often does not address questions of direct relevance to conservation managers (Whitten et al. 2001; Fazey et al. 2005) or deliver information when needed (Kareiva et al. 2002; Linklater 2003). These impediments to using science to guide practice have contributed to the poor use of empirical evidence to inform management decisions (Sutherland et al. 2004; Cook et al. 2010).

The challenge of translating science into practice is not unique to conservation but is common to many applied disciplines (Pfeffer & Sutton 1999; Pullin & Knight 2001). Concern about the lack of evidence in medical practice (Forsyth 1963; Cochrane 1972; Maynard & Chalmers 1997) stimulated an evidence revolution (Pullin & Knight 2001) that promoted randomized, controlled trials as the standard for credible evidence (Stevens & Milne 1997). To help practitioners manage the rapid increase in available evidence (Chalmers 1993), systematic reviews were developed as a tool to collate (systematically search the available literature), filter (identify credible sources of evidence), synthesize (analyze the body of evidence to determine the overall effect of an intervention), and disseminate the evidence for the effectiveness of potential and currently used treatment options on a topic for practitioners (Higgins & Green 2011). The rigorous methodological and statistical protocol associated with systematic reviews minimizes bias and improves their transparency and repeatability (Pullin & Stewart 2006; Newton et al. 2007). These factors make systematic reviews more comprehensive and less open to potential bias than other review formats that summarize the literature in an unstructured way (e.g., narrative reviews) (Roberts et al. 2006). A distinct focus on making recommendations for management and a systematic search of both the peer-reviewed and gray literatures generally distinguish systematic reviews from traditional meta-analytical studies. The practice of systematic reviews has been widely adopted in medicine, health sciences, education, criminology, and several other disciplines (Hansen & Rieper 2009).

The benefits of an evidence-based approach to medical practice have led several authors to promote systematic reviews as a tool for integrating science into conservation practice (e.g., Pullin & Knight 2001; Fazey et al. 2004; Sutherland et al. 2004). Systematic reviews facilitate evidence-based conservation practice by providing managers with an overview of relevant, trustworthy empirical evidence pertinent to a decision (Pullin & Stewart 2006). The evidence movement has been instrumental in highlighting the importance of evaluating the effectiveness of management interventions (Ferraro & Pattanayak 2006) so that decision makers do not waste time and money on ineffective or potentially harmful management interventions (Pullin & Knight 2001). By combining the replicates from multiple studies, systematic review can also maximize the value of primary research, generating greater explanatory power, which may reveal effects not detected by the original individual studies (Mulrow 1994).

To facilitate systematic reviews and make them freely available to managers, the Collaboration for Environmental Evidence (CEE) (www.environmentalevidence.org) was developed (Pullin & Knight 2009). The collaboration was modeled on the Cochrane Collaboration for medical practice and the Campbell Collaboration for social programs. The CEE has developed detailed guidelines (Pullin & Stewart 2006; CEBC 2010) to assist authors wishing to conduct systematic reviews of conservation interventions.

With evidence-based conservation being embraced by the conservation community as a desirable approach to decision making, it is timely to review the benefits to conservation practice arising from systematic reviews. We examined how the method of systematic review has been applied to evidence about the effectiveness of conservation interventions and the benefits they have provided to conservation practice. We measured the level of guidance systematic reviews offer conservation managers and quantified the types of conservation questions being addressed; geographic and taxonomic breadth of reviewed topics; and the quantity of primary research available in a format suitable for systematic review. We considered the benefits to environmental management arising from systematic reviews and how systematic reviews might be improved.

Methods

Criteria and Method for Selection of Systematic Reviews

We based selection of systematic reviews on the criteria outlined in the guidelines for systematic reviews of conservation evidence published by Pullin and Roberts (2006). Accordingly, we ensured that reviewers had clearly defined a question focused on evaluating the effectiveness of a conservation intervention with implications for management or policy; used a systematic and objective approach to search the literature without limiting the publication period; established clear and transparent criteria for the inclusion of studies in the review; synthesized available data through a meta-analysis or scoring system; and discussed the findings in relation to the implications for management or policy.

Pullin and Roberts (2006) recommend that authors formulate the review question in consultation with managers and stakeholders, assess the methodological quality of relevant studies, evaluate the sources of heterogeneity in the data sets and document the data extracted from studies included in the review. Published reviews often do not document such steps, although this did not disqualify them from our sample because lack of documentation does not mean these steps were not conducted. Formal quantitative analyses within systematic reviews ideally involve a meta-analysis that includes summary effect sizes for each data set weighted according to some measure of its importance (Pullin & Stewart 2006). However, we included systematic reviews that used any quantitative approach to meta-analysis or used a scoring approach, where the results of each study were tallied according to whether the intervention yielded positive, negative, or equivocal results.

To identify relevant studies, we used electronic searches of ISI Web of Knowledge (i.e., ISI Web of Science: Science Citation Index Expanded 1945–present and ISI Proceedings: Science and Technology Proceedings 1990–present) and Google Scholar and searched for the terms “systematic review” and “conservation.” We refined each of these searches by excluding results from unrelated disciplines, such as medicine, chemistry, or physics, to limit the number of irrelevant articles returned. We also searched the online CEE library for systematic reviews listed as completed. We extracted several pieces of information from each review that met our selection criteria (summarized later and detailed in Supporting Information).

Types and Breadth of Reviews

We determined whether the key audience for the review findings was policy makers or on-the-ground managers (Supporting Information).

We were interested in whether there is a trade-off between the geographic and taxonomic breadth of a review and whether it had direct implications for management. We used the selection criteria described in the review to establish the intended breadth of the review (the pool of research from which data could be drawn—e.g., all birds). We then used the data captured within the meta-analysis to determine the realized coverage of the review (e.g., number of bird species with data included in the meta-analysis). We measured geographic scope by the number of countries relevant to the review topic and realized geographic coverage by the proportion of the geographic scope for which data were represented in the meta-analysis. Taxonomic scope was the number of species relevant to the review topic, and taxonomic coverage was the proportion of the taxonomic scope with data included in the meta-analysis. We estimated taxonomic scope when the definition was ecological rather than strictly taxonomic (e.g., ground- and cliff-nesting birds). If reliable estimates could not be found, we omitted the review from the analysis of scope. In many cases, such as when estimates could be obtained for only some taxonomic groups, only the minimum number of taxa could be estimated. For the purpose of analyses, we normalized the geographic and taxonomic coverage variables by log10 transformation.

Evidence Captured by Reviews

To estimate the level of evidence available for each systematic review, we recorded the number of studies the review authors reported as relevant to the review topic after evaluating the title and abstract. Although we assumed abstracts accurately reflected the contents of the paper, if this was not always the case, our results will overestimate the number of relevant studies. Although the majority of authors reported the number of relevant studies, in some cases it was necessary to contact the corresponding author to request these data. We also recorded the number of studies that met the criteria for inclusion in each review. This figure captures the studies included in the meta-analysis and, if relevant, those studies included only in sections of the review that provide a qualitative synthesis of the relevant literature.

To capture the research effort underpinning a meta-analysis, we recorded the number of independent statistical units included in each meta-analysis. We also calculated the total number of years of data collection embodied in the primary studies being reviewed. Although both these measures of research effort are imperfect, they are indicative of the effort involved in generating the primary literature underpinning a topic. Where the number of years of research effort was not reported in a systematic review, we examined the original primary studies to extract the number of years of data collection reported therein. When this figure could not be obtained, we generated an estimate from the available data. Five systematic reviews had 65–129 primary studies in the meta-analysis, and owing to the time-consuming nature of examining each primary study, we used a random sample of one-third of studies to generate the number of years of data collection. For analyses the number of independent data sets and number of years of data collection were normalized by log10 transformation.

Findings from Reviews

The goal of systematic review is to provide a dispassionate synthesis of the best available evidence, not to be prescriptive about how a practitioner should act. Practitioners must still interpret this information according to the relevant socioeconomic and ecological circumstances (Chalmers 1993). Therefore, we evaluated the findings arising from the data synthesis, given the limitations of each review, and classified them according to their implications for management practice (Table 1) and conservation science. Where possible, we recorded the overall effect size emerging from meta-analyses. We then investigated whether attributes of the reviews contributed to the degree to which they could unambiguously inform management decisions.

Table 1.

Description of the categories used to identify whether systematic reviews of conservation evidence have implications for management

| Implications for management | Description | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Yes | The review presents unequivocal evidence across the full scope of the review with direct implications for the conduct of management. | Culling is not an effective method of reducing the abundance of yellow-legged gulls (Larus michahellis) to protect threatened waterbirds (Oro & Martínez-Abraín 2007). |

| Some direct implications | Findings partially address the scope of the review, providing guidance relevant to some management contexts. This includes reviews that lack data on some of the relevant management alternatives and those where findings vary according to the environments and taxonomic groups being considered. | Two of 4 herbicides significantly reduce Rhododendron ponticum, but the best concentration and method of application cannot be determined. Results for the other herbicides were inconclusive (Tyler et al. 2006).Some mammal and bird populations are displaced by road infrastructure, but the effect varies with the habitat type and species considered (Benítez-López et al. 2009). |

| No | No conclusions can be drawn from the review due to insufficient data, equivocal evidence for the effectiveness of an intervention, or confounding variables in the original studies. | All studies had poor design and no conclusions could be drawn (Isasi-Catalá 2010).Herbicides used close to conservation areas appear to decrease invertebrates but most studies did not control for the use of fertilizers or were greenhouse trials (Frampton & Dorne 2007). |

Results

Number of Systematic Reviews

We conducted literature searches in March 2012 and located 3375 articles (ISI Web of Knowledge, n = 42; Google Scholar, n = 3290; CEE, n = 43). The majority of articles was irrelevant because they were duplicate records; discussed rather than conducted a systematic review; did not address a conservation intervention; were systematic reviews of taxonomy; or were related to medical interventions. After reviewing these articles, 43 met our criteria for systematic reviews of conservation evidence (Supporting Information). Supporting Information provides a list of studies that met some of our criteria and the reasons they were ultimately excluded.

Findings from Reviews

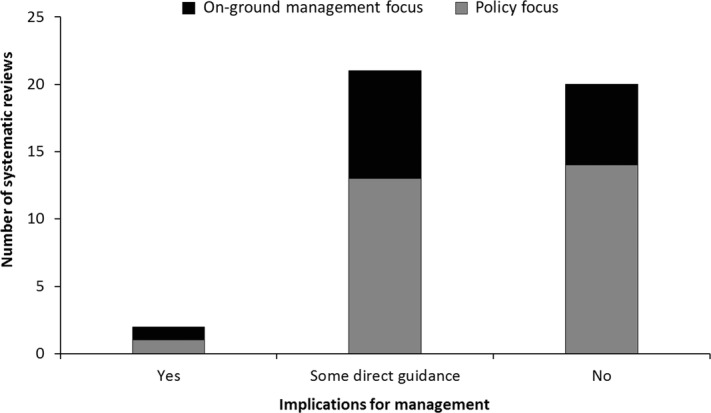

Two of the 43 reviews provided guidance across the full geographic and taxonomic breadth of the review. However, 21 reviews had direct implications for only some interventions of interest or some management contexts (Fig.1). Conclusions about the effect of the intervention could not be drawn from the remaining 20 reviews due to small sample sizes, confounding variables, or conflicting results across the primary studies (Fig.1).

Figure 1.

Number of systematic reviews (n = 43) within each recommendation category (Table 1) sorted by review topic.

Although most reviews provided only some guidance for management practice, almost all (93%) identified existing knowledge gaps and made recommendations for the direction of future research effort. A large proportion (79%) also highlighted common flaws in existing research methods and recommended changes to experimental design to improve the value of future primary research.

Types of Review Questions

Reviews tended to address questions of conservation policy (65%) (Supporting Information) relevant to the efficacy of high-level conservation tools, such as habitat corridors (Davies & Pullin 2007; Doerr et al. 2010; Eycott et al. 2010) and marine protected areas (Stewart et al. 2009a), or emerging conservation issues, such as the effect of wind farms on birds (Stewart et al. 2007a). A minority of reviews (35%) addressed issues directly relevant to on-the-ground managers (Supporting Information), such as the effectiveness of options to control individual weed species (e.g., Kabat et al. 2006; Roberts & Pullin 2006; Roberts & Pullin 2007a; Stewart et al. 2007b).

Although the topic of reviews did not affect the type of findings arising from the reviews (Fig.1), larger overall effect sizes were detected in reviews that addressed topics relevant to on-the-ground managers (mean effect size = 2.95) than reviews that addressed questions of conservation policy (mean effect size = 1.60; t = 2.62; df = 26; p = 0.03).

Breadth of Reviews

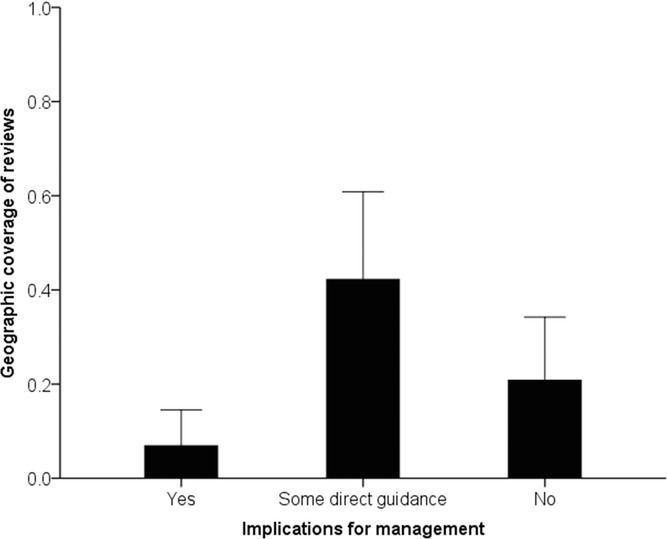

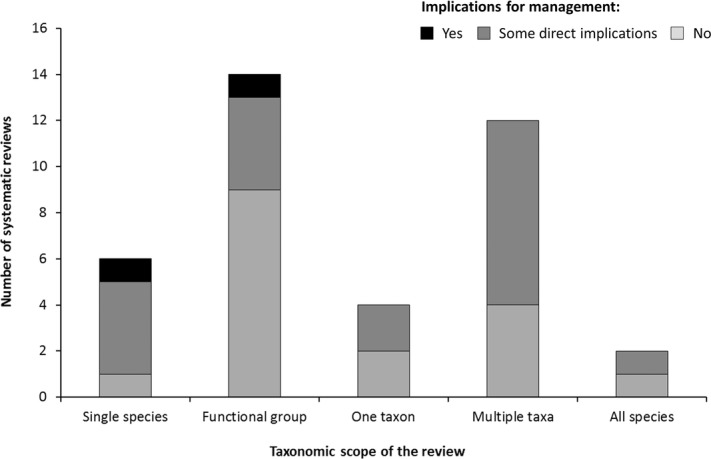

In many cases, the geographic and taxonomic scope of reviews was not clearly defined or no obvious restrictions on scope were mentioned. Thirty percent of reviews restricted the geographic scope to a small number of countries (≤10), but most reviews had a much broader geographic scope (median = 141 countries [SE 14], range = 1–196 countries) (Supporting Information). However, the realized coverage of reviews from data actually included in the meta-analysis tended to be much lower (median = 13% of countries [SE 6]) (Table 2 & Fig.2). We also found a distinct geographic bias toward western countries, particularly those in western Europe and North America. Reviews that provided some management guidance showed a non significant tendency to include data from a greater proportion of the countries relevant to the scope of the review than those that were unable to provide guidance (t = –2.02; df = 37; p = 0.33) (Fig 2). Likewise, many of the reviews had a very wide taxonomic scope (range = 1–936, 244 species) but realized a much narrower taxonomic coverage (median = 16% of species [SE 8]) (Table 2). Reviews overrepresented primary studies featuring vertebrates, particularly birds, relative to global species richness and underrepresented more diverse taxonomic groups, such as invertebrates and plants. There was no clear difference between the proportion of species represented between reviews that could or could not provide guidance to managers (t = 0.49; df = 23; p = 0.62). However, the only reviews to fully address the stated scope were restricted to a single species or small functional groups of species (Fig.3).

Table 2.

The geographic and taxonomic coverage of systematic reviews of conservation evidence

| Geographic | Taxa of | Taxonomic | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reference | Review topic | Places of interest | coveragea (%) | interest | coverageb (%) |

| Abella 2009 | effects of fire on vegetation in the Mohave and Sonoran Deserts | U.S.A. | 1 | plants | CBCc |

| Bayard & Elphick 2010 | effects of fragmentation on birds | global | CBCc | birds | 10 |

| Benitez-Lopez et al. 2009 | effects of roads and other infrastructure on mammal and bird populations | global | 9 | mammals and birds | 1 |

| Bowler et al. 2012 | effects of community forest management on global environmental benefits and local welfare | global | 5 | CBCc | CBCc |

| Brooks et al. 2006 | effects of development on ecological, economic, attitudinal, and behavioral outcomes | global | 7 | NAd | NAd |

| Bussell et al. 2010 | effects of draining and re-wetting peatland soils on carbon stores and greenhouse gas fluxes | global | 6 | bogs, fens and mires | 47 |

| Dalrymple et al. 2011 | effects of reintroductions on plant extinctions | global | 7 | plants | <1 |

| Davies & Pullin 2007 | effects of hedgerows on movement between fragments of woodland habitat | North America, Europe | 19 | woodland species | CBCc |

| Davies et al. 2008 | effects of current management recommendations on saproxylic invertebrates | global | 4 | saproxylic invertebrates | CBCc |

| Doerr et al. 2010 | effects of structural connectivity on the dispersal of native species in Australia’s fragmented landscapes | Australia | 100 | Australian flora and fauna | 1 |

| Eycott et al. 2012 | effects of landscape matric features on species movement | global | 10 | fauna | <1 |

| Frampton & Dorne 2007 | effects on invertebrates of pesticide usage at crop edges | global | <1 | terrestrial invertebrates | <1 |

| Gusset et al. 2010 | effects of wild dog (Lycaon pictus) reintroductions in South Africa | South Africa | 100 | wild dogs (L. pictus) | 100 |

| Holt et al. 2008 | effects of predation on prey abundance in the United Kingdom | U.K. | 50 | vertebrates | 3 |

| Isasi-Catalá 2010 | effects of translocating problematic jaguars (Panthera onca) on human-predator conflicts | South and Central America | 18 | jaguar (P. onca) | 100 |

| Kabat et al. 2006 | effects of control and eradication interventions on Japanese knotweed (Fallopia japonica) | Australia, Europe, North America, New Zealand | 15 | Japanese knotweed (F. japonica) | 100 |

| Kalies et al. 2010 | effects of thinning and burning in southwestern conifer forests on wildlife density and populations in the United States | U.S.A. | 100 | birds, mammals, reptiles, amphibians in southwestern conifer forests, U.S.A. | 16 |

| Kettenring & Adams 2011 | effects of control on invasive plant species | global | 13 | Plants | 4 |

| Mant et al. 2011 | effects of liming streams and rivers on fish and invertebrates | Europe, North America | 9 | fish and invertebrates | CBCc |

| Martinez-Abrain et al. 2010 | effects of recreational activities on nesting birds of prey | global | 6 | birds of prey | 4 |

| McLeod et al. 2008 | effects of controlling European red foxes (Vulpes vulpes) biological diversity and agricultural production in Australia | Australia | 100 | Australian birds, mammals, reptiles, amphibians, livestock, invertebrates, poultry | 18 |

| Newton et al. 2009 | effects of grazing on lowland heathland in northwest Europe | Europe | 12 | lowland heathland | CBCc |

| Oro & Martínez-Abraín 2007 | effects of large gulls on sympatric threatened waterbirds | Europe, Africa | 11 | threatened waterbirds | 100 |

| Peppin et al. 2010 | effects of postwildfire seeding in forests of the western United States | U.S.A. | 100 | forest species | CBCc |

| Radwan et al. 2010 | effects of reduced major histocompatibility complex diversity on vertebrate populations | global | 10 | vertebrates | <1 |

| Roberts & Pullin 2006 | effects of different management on Spartina species | global | 3 | Spartina alternifolia, S. anglica, S. densiflora, S. patens, S. x townsendii | 40 |

| Roberts & Pullin 2007a | effects of management interventions on ragwort species | U.K., Ireland, North America, Australia, New Zealand, South Africa, Argentina | 83 | ragwort (Senecio jacobaea and S. aquaticus) | 100 |

| Roberts & Pullin 2007b | effects of land-based schemes (incl. agri-environment) on farmland bird densities in the United Kingdom | U.K. | 100 | farmland birds in the United Kingdom | 31 |

| Showler et al. 2010 | effects of public access on ground-nesting and cliff-nesting birds | global | 6 | ground-nesting and cliff-nesting birds | CBC |

| Smith et al. 2010 | effects of predator removal on bird populations | global | 6 | birds | 1 |

| Smith et al. 2011 | effects of nest predator exclusion on bird populations | global | 2 | birds | <1 |

| Stacey et al. 2011 | effects of arid land springs restoration on hydrology, geomorphology, and invertebrate and plant species composition | Europe, North and South America, Australasia | 6 | invertebrate and plant species associated with land springs | CBCc |

| Stewart & Pullin 2008 | effects of grazing stock type and intensity on the conservation of mesotrophic old- meadow pasture | U.K. | 20 | mesotrophic “old meadow” pasture community | 100 |

| Stewart et al. 2005 | effects of moorland burning in heath and bogs on biological diversity and effects of burning on blanket bog | U.K., Ireland | 60 | bogs, heaths, and montane communities | 37 |

| Stewart et al. 2007a | effects of wind farms on birds | global | 4 | Birds | 23 |

| Stewart et al. 2007b | effectiveness of Asulam for bracken (Pteridium aquilinum) control in the United Kingdom | U.K. | 75 | bracken (P. aquilinum) | 100 |

| Stewart et al. 2007c | effects of salmonid stocking in lakes on native fish populations and other fauna and flora | global | 2 | freshwater fishes, reptiles, amphibians, invertebrates, and flora | <1 |

| Stewart et al. 2009a | global ecological effects of temperate marine reserves | global | 4 | marine fishes, algae, and invertebrates | 2 |

| Stewart et al. 2009b | effects of engineered in-stream structure on salmonid abundance | global | 4 | salmon species, trout species and Cottus gobio | 12 |

| Timonen et al. 2011 | woodland key habitats as biological diversity hotspots in boreal forests | Sweden, Finland, Norway, Denmark, Latvia, Lithuania, Estonia, Russia | 38 | boreal forest species | CBCc |

| Tyler et al. 2005 | effects of management interventions on American mink (Mustela vison) populations | Europe, North America | 21 | American mink (M. vison) | 100 |

| Tyler et al. 2006 | effects of management interventions on Rhododendron ponticum | U. K., Ireland, Austria, Belgium, France, Netherlands, New Zealand | 40 | R. ponticum | 100 |

| Waylen et al. 2010 | effects of local cultural context on community-based conservation interventions | global | 16 | NAd | NAd |

Percentage of relevant countries represented in the meta-analysis.

Percentage of relevant species represented in the meta-analysis.

Could not be calculated.

Not applicable.

Figure 2.

Proportion of relevant countries with data included in the meta-analysis (geographic coverage) of the systematic review on the basis of type of implications for management practice (n = 41) (error bars indicate SE).

Figure 3.

Taxonomic scope of the systematic review according to the type of implications for management practice (n =40).

Evidence Captured by Reviews

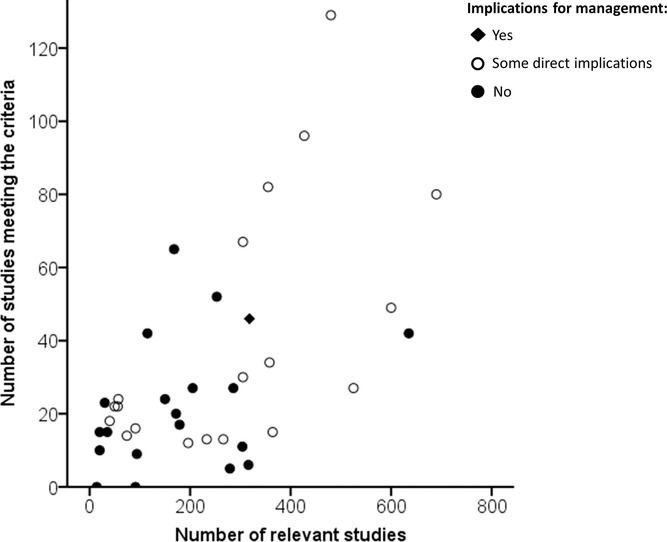

The reviews we evaluated commonly reported large numbers of relevant studies (μ = 315 [SE 85]) (Fig.4); however, the strict inclusion criteria for reviews and the limited quality of much of the available primary literature led to a median of only 12% of relevant studies being included in the meta-analysis. The reasons for this high attrition of relevant studies included: a different measure of outcome (e.g., measuring the effect of an intervention on fecundity instead of mortality); no measure of variance reported for the data set; research methods that failed to meet quality standards (e.g., no data collected prior to the intervention and lack of experimental controls); and use of multiple management interventions that masked the effect of the intervention of interest.

Figure 4.

Number of relevant studies found and those included in systematic review grouped by the type of implications for conservation practice (n =40).

Despite 88% of the available research being excluded from systematic reviews, the meta-analyses still captured a large research effort. On average, the primary studies included in each meta-analysis represented 284 independent data sets (SE 109) and a combined total of 112 years (SE 24) of data collection. However, we found no statistically significant difference between reviews that could or could not provide guidance to managers for either the number of data sets (t = –1.43; df = 37; p = 0.82) or the number of years of data collection (t = 1.60; df = 39; p = 0.11) embodied in the meta-analysis.

Discussion

We located 43 systematic reviews on the effectiveness of conservation interventions published from January 2001 through March 2012. Just over half had direct implications for conservation practice, but almost as many could not directly inform management (Fig.1). Although direct comparisons among disciplines can be problematic and the small sample size of available reviews undoubtedly limits inference, this result is consistent with reviews within the fields of medicine, social welfare, education, and criminology, where 54% of systematic reviews could not draw conclusions about the effectiveness of interventions (Hansen & Rieper 2009). Considerable time and money are required to produce a review (up to $US300,000) (CEBC 2010), so the frequency with which reviews fail to provide implications for management may discourage authors from conducting systematic reviews.

It has been suggested that systematic reviews of conservation interventions are not well suited to addressing broad policy issues (Fazey et al. 2004). Ecological phenomena vary enormously among species and environments (Hawkins et al. 2003; Magurran et al. 2010), and reviews with a policy focus tended to encompass a broad geographic and taxonomic scope, reflecting this variation. Reviews with a broader geographic scope highlighted geographic variation in the effectiveness of interventions (Fig.2), and reviews addressing more than one functional group could provide guidance only for a narrow set of management contexts within their overall breadth (Fig.3). Reviews focusing on big-picture conservation interventions tend to provide little guidance for individual conservation managers because there is often substantial heterogeneity in results across different spatiotemporal scales and for different focal species (e.g., Stewart et al. 2009a). We echo cautions raised in the medical literature that broad review questions increase the heterogeneity in the circumstances under which interventions are made, making findings harder to interpret (Higgins & Green 2011).

Taking an evidence-based approach to developing conservation policy is clearly desirable (Pullin et al. 2009). However, we found that the available data rarely justify conducting reviews with a broad geographic and taxonomic scope because only a fraction of this scope (13–16%) is actually realized. Despite attempting to address diverse taxonomic and geographic regions, the individual reviews were generally highly taxonomically and geographically biased due to limitations in the available data. Research from North America and Europe was overrepresented as was research on particular taxonomic groups, such as birds and mammals. Despite the rigor of the systematic review method, it could thus be argued that many reviews provide little information to managers that cannot be provided through traditional narrative reviews or research synopses (www.conservationevidence.com/synopses.php), which summarize the primary literature on a topic in a more informal manner. Moreover, the poor quality of much of the available literature and the restrictive criteria imposed by quantitative meta-analysis methods mean that much potentially relevant science might be excluded from a systematic review. Given the expense, time, and expertise required to conduct a systematic review, careful consideration is needed to determine which conservation questions warrant a systematic review versus a narrative review or other form of information synthesis.

The breadth of many of the reviews may explain why there were often hundreds of relevant studies reported during the literature search phase of the reviews (Fig.4) and a significant research effort (μ = 284 data sets; μ = 112 years) captured by the analyses. Research effort was unrelated to the strength of the meta-analysis, such that a review with little data was as likely to yield clear findings as one representing hundreds of data sets or years of data collection. Therefore, contrary to other disciplines that attribute high failure rates of reviews to a lack of available primary data (Hansen & Rieper 2009), it is possible that this is not a primary concern in conservation science.

One aspect of systematic reviews that we could not address is whether reviews change management practices. The types of evidence valued by managers is an understudied area (but see Pullin & Knight 2005; Cook et al. 2012), and managers’ perspectives on the value of systematic reviews and other types of information syntheses could provide valuable insight into the types of questions best suited to each approach and which research questions should be given priority (Braunisch et al. 2012). We observed a tendency for systematic reviews to address big-picture conservation issues, sometimes at the expense of relevance for on-the-ground managers. Bilateral communication between scientists and managers throughout the review process is likely to improve the relevance of systematic reviews (Cook et al. 2013).

Benefits of Systematic Reviews

We found that systematic reviews are effective at exposing important knowledge gaps. For example, studies of the effectiveness of invasive species control rarely quantify the benefits for biological diversity (Kettenring & Adams 2011). Practitioners are an important resource for identifying key knowledge gaps in conservation science (Braunisch et al. 2012). However, the well-documented mismatch between conservation science and information priorities for on-the-ground managers (e.g., Whitten et al. 2001; Fazey et al. 2005) highlights the important role systematic reviews can play in articulating key research priorities to scientists.

The research quality standards imposed by systematic reviews frequently highlight methodological problems with published research, and most reviews make recommendations for how methods should be strengthened to provide greater value for management decisions. For example, research on the effectiveness of invasive species control methods often use greenhouse studies that do not reflect management conditions (Roberts & Pullin 2007a). Likewise, when research findings are obstructed by confounding variables, reviews can highlight necessary improvements to experimental protocols (e.g., Frampton & Dorne 2007). Therefore, even when reviews fail to provide guidance for on-the-ground managers, they can yield many useful recommendations about how to improve the quality of management-relevant conservation science.

Opportunities to Improve Systematic Reviews of Conservation Evidence

We suggest there are several opportunities to improve the application of the systematic methodology to yield greater benefits for conservation management: encourage more reviews, select the appropriate topic and breadth, make better use of available data, and evaluate cost-effectiveness.

The small number of systematic reviews conducted leaves many critical conservation management issues without a comprehensive synthesis of existing evidence. The imperative for academics to publish in high-impact journals (Gibbons et al. 2008) and the considerable time and money required to conduct systematic reviews (CEBC 2010) mean they are currently relatively unattractive. Additional avenues for funding and publishing reviews are required and more open-access scientific platforms for distilling relevant information, such as Environmental Evidence, would benefit conservation managers. To streamline the review process, software now exists to capture, store, and synthesize primary data for reviews (e.g., Eco Evidence—Webb et al. 2011). Making evidence summaries available to other users through a communal database allows existing reviews to be easily updated or modified so that information can be used in new reviews. This practice reduces duplication of effort and could provide a valuable resource for decision makers searching for reliable evidence pertaining to a specific topic.

Incentives for academics to publish may explain why we observed a mismatch between the narrow review questions likely to be more valuable to decision makers and the prevalence of high-level conservation questions likely to be interesting to a broad scientific audience. Knowledge maps highlight where gaps in the available literature warrant the review topic being refined to provide the greatest value for decision makers (CEBC 2010). Encouraging authors to conduct reviews with a narrower scope focused on informing on-the-ground management decisions would help streamline the review process and simplify the interpretation of findings (Higgins & Green 2011). Narrow review topics may not elucidate the sources of heterogeneity in the effectiveness of an intervention that are helpful for conservation policy; overview reviews developed for evidence-based medicine (Whitlock et al. 2008) can achieve this by drawing together the results of several narrowly focused reviews. However, the cost-effectiveness of overview reviews has not been examined.

Not all of the 88% of relevant studies excluded from reviews provide meaningful evidence. However, the stringent requirements for data inclusion in a meta-analysis undoubtedly result in potentially useful information being excluded (Pullin & Stewart 2006). To reflect a broader evidence base without compromising on the quality of science, formalized scoring approaches, such as causal criteria analyses (Norris et al. 2012) and Bayesian approaches that capture expert knowledge (Newton et al. 2007) can be used. These less-stringent methods capture up to 30% more data than meta-analysis and can test a broader range of hypotheses (Greet et al. 2011). Other disciplines have also broadened their definitions of credible evidence to suit the questions being addressed (Hansen & Rieper 2009) and are using evidence typologies to define the appropriate types of evidence according to the nature of the research question (Petticrew & Roberts 2003). Similarly, methods are being developed to identify rigorous qualitative research (Higgins & Green 2011) that can complement, enhance, extend, and supplement the quantitative analysis in systematic reviews (Petticrew & Roberts 2003; Higgins & Green 2011).

The cost of an action can materially alter conclusions about the best interventions for a given context (Baxter et al. 2006). We believe that to be of greatest valuable to managers, systematic reviews should include an explicit cost-effectiveness analysis (Segan et al. 2011). Some review authors have recognized the importance of including costs (e.g., Doerr et al. 2010; Kettenring & Adams 2011) but have been prevented from analyzing the cost-effectiveness of different interventions by poor reporting of management costs within primary studies. A further impediment is the lack of guidelines for capturing cost-effectiveness in systematic reviews of conservation interventions (Pullin & Stewart 2006).

Value of Systematic Reviews

The need for effective management highlights the value of tools to synthesize and distribute credible evidence to decision makers. Systematic reviews can be an important part of the conservation decision making tool kit; however, the current application of this method generally fails to harness their full potential, and at present systematic review is most useful for summarizing the current state of knowledge, identifying knowledge gaps, and highlighting where the quality of existing research needs to be improved. We believe that the benefits of systematic reviews could be enhanced by increasing the number of reviews focused on questions of direct relevance to on-the-ground managers, a more focused geographic and taxonomic scope that better reflects the available data, greater use of existing knowledge that includes a broader range of evidence types, and inclusion of an appraisal of the cost-effectiveness of interventions.

Acknowledgments

This research was conducted with the support of funding from the Australian Research Council Centre of Excellence in Environmental Decisions and the Environmental Decisions Hub of the National Environmental Research Program. We thank A. Pullin and W. Sutherland for valuable discussions and feedback during the development of this manuscript.

Supporting Information

A description of the variables extracted from each systematic review and the source of these data(Appendix S1), the geographic and taxonomic scope and coverage of each systematic review (Appendix S2); a list of the systematic reviews that met the criteria for inclusion in this study sorted by the audience for the review (Appendix S3), and a list of studies that failed to meet the criteria for inclusion and the rationale for exclusion (Appendix S4) are available online. The authors are solely responsible for the content and functionality of these materials. Queries (other than absence of the material) should be directed to the corresponding author.

Literature Cited

- Abella SR. Post-fire plant recovery in the Mojave and Sonoran Deserts of western North America. Journal of Arid Environments. 2009;73:699–707. [Google Scholar]

- Baxter PWJ, McCarthy MA, Possingham HP, Menkhorst PW. McLean N. Accounting for management costs in sensitivity analyses of matrix population models. Conservation Biology. 2006;20:893–905. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1739.2006.00378.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bayard TS. Elphick CS. How area sensitivity in birds is studied. Conservation Biology. 2010;24:938–947. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1739.2010.01480.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benítez-López A, Alkemade R. Verweij PA. Are mammal and bird populations declining in the proximity of roads and other infrastructure? Systematic review 68. Bilthoven, The Netherlands: Collaboration for Environmental Evidence; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Bowler DE, Buyung-Ali LM, Healey JR, Jones JPG, Knight TM. Pullin AS. Does community forest management provide global environmental benefits and improve local welfare? Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment. 2012;10:29–36. [Google Scholar]

- Braunisch V, Home R, Pellet J. Arlettaz R. Conservation science relevant to action: a research agenda identified and prioritized by practitioners. Biological Conservation. 2012;153:201–210. [Google Scholar]

- Brooks JS, Franzen MA, Holmes CM, Grote MN. Mulder MB. Testing hypotheses for the success of different conservation strategies. Conservation Biology. 2006;20:1528–1538. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1739.2006.00506.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bussell J, Jones DL, Healey JR. Pullin AS. How do draining and re-wetting affect carbon stores and greenhouse gas fluxes in peatland soils? Systematic review 49. Bangor, United Kingdom: Collaboration for Environmental Evidence; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Centre for Evidence-Based Conservation (CEBC) Guidelines for systematic review in environmental management. Version 4.0. Environmental evidence 2010. CEBC, Bangor University, Bangor, United Kingdom. Available from www.environmentalevidence.org/Authors.htm (accessed September 2012)

- Chalmers I. The Cochrane collaboration: preparing, maintaining and disseminating systematic reviews of the effects of health care. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 1993;703:156–165. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1993.tb26345.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cochrane AL. Effectiveness and efficiency: random reflections on health services. London: The Nuffield Provincial Hospitals Trust; 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Cook CN, Carter RW, Fuller RA. Hockings M. Managers consider multiple lines of evidence important for biodiversity management decisions. Journal of Environmental Management. 2012;113:341–346. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvman.2012.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook CN, Hockings M. Carter RW. Conservation in the dark? the information used to support management decisions. Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment. 2010;8:181–186. [Google Scholar]

- Cook CN, Mascia MB, Schwartz MW, Possingham HP. Fuller RA. Achieving conservation science that bridges the knowledge-action boundary. Conservation Biology. 2013;27 doi: 10.1111/cobi.12050. DOI: 10.1111/cobi.12050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalrymple SE, Stewart GB. Pullin AS. Are reintroductions an effective way of mitigating against plant extinctions? Systematic review 32. Aberdeen, United Kingdom: Collaboration for Environmental Evidence; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Davies ZG. Pullin AS. Are hedgerows effective corridors between fragments of woodland habitat? An evidence-based approach. Landscape Ecology. 2007;22:333–351. [Google Scholar]

- Davies ZG, Tyler C, Stewart GB. Pullin AS. Are current management recommendations for saproxylic invertebrates effective? a systematic review. Biodiversity and Conservation. 2008;17:209–234. [Google Scholar]

- Doerr VAJ, Doerr ED. Davies MJ. Does structural connectivity facilitate dispersal of native species in Australia’s fragmented terrestrial landscapes? Systematic review 44. Canberra, Australia: Collaboration for Environmental Evidence; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Eycott A, Watts K, Brandt G, Buyung-Ali L, Bowler D, Stewart GB. Pullin AS. Do landscape matric features affect species movement? Systematic review 43. United Kingdom: Collaboration for Environmental Evidence, Farnham; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Eycott AE, Stewart GB, Buyung-Ali LM, Bowler DE, Watts K. Pullin AS. A meta-analysis on the impact of different matrix structures on species movement rates. Landscape Ecology. 2012;27:1263–1278. [Google Scholar]

- Fazey I, Fischer J. Lindenmayer DB. What do conservation biologists publish? Biological Conservation. 2005;124:63–73. [Google Scholar]

- Fazey I, Salisbury JG, Lindenmayer DB, Maindonald J. Douglas R. Can methods applied in medicine be used to summarize and disseminate conservation research? Environmental Conservation. 2004;31:190–198. [Google Scholar]

- Ferraro PJ. Pattanayak SK. Money for nothing? A call for empirical evaluation of biodiversity conservation investments. PLoS Biology. 2006;4:482–488. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0040105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forsyth G. An enquiry into drug bill. Medical Care. 1963;1:10–16. [Google Scholar]

- Frampton GK. Dorne JCM. The effects on terrestrial invertebrates of reducing pesticide inputs in arable crop edges: a meta-analysis. Journal of Applied Ecology. 2007;44:362–373. [Google Scholar]

- Gibbons P, et al. Some practical suggestions for improving engagement between researchers and policy-makers in natural resource management. Ecological Management & Restoration. 2008;9:182–186. [Google Scholar]

- Greet J, Webb JA. Cousens RD. The importance of seasonal flow timing for riparian vegetation dynamics: a systematic review using causal criteria analysis. Freshwater Biology. 2011;56:1231–1247. [Google Scholar]

- Gusset M, Stewart GB, Bowler DE. Pullin AS. Wild dog reintroductions in South Africa: a systematic review and cross-validation of an endangered species recovery programme. Journal for Nature Conservation. 2010;18:230–234. [Google Scholar]

- Hansen HF. Rieper O. The evidence movement: the development and consequences of methodologies in review practices. Evaluation. 2009;15:141–163. [Google Scholar]

- Hawkins BA, et al. Energy, water, and broad-scale geographic patterns of species richness. Ecology. 2003;84:3105–3117. [Google Scholar]

- Higgins JPT. Green S. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions. London: The Cochrane Collaboration; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Holt AR, Davies ZG, Tyler C. Staddon S. Meta-analysis of the effects of predation on animal prey abundance: evidence from UK vertebrates. PLoS ONE. 2008;3:e2400. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isasi-Catalá E. (Panthera onca) Caracas, Venezuela: Collaboration for Environmental Evidence; 2010. Is translocation of problematic jaguars. an effective strategy to resolve human-predator conflicts? Systematic Review No. 55. [Google Scholar]

- Kabat TJ, Stewart GB. Pullin AS. (Fallopia japonica) Birmingham, United Kingdom: Collaboration for Environmental Evidence; 2006. Are Japanese knotweed. control and eradication interventions effective? Systematic review 21. [Google Scholar]

- Kalies EL, Chambers CL. Covington WW. Wildlife responses to thinning and burning treatments in southwestern conifer forests: a meta-analysis. Forest Ecology and Management. 2010;259:333–342. [Google Scholar]

- Kareiva P, Marvier M, West S. Hornisher J. Slow-moving journals hinder conservation efforts. Nature. 2002;420:15. doi: 10.1038/420015a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kettenring KM. Adams CR. Lessons learned from invasive plant control experiments: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Applied Ecology. 2011;48:970–979. [Google Scholar]

- Linklater WL. Science and management in a conservation crisis: a case study with rhinoceros. Conservation Biology. 2003;17:968–975. [Google Scholar]

- Magurran AE, Baillie SR, Buckland ST, Dick JMcP, Elston DA, Scott EM, Smith RI, Somerfield PJ. Watt AD. Long-term datasets in biodiversity research and monitoring: assessing change in ecological communities through time. Trends in Ecology & Evolution. 2010;25:574–582. doi: 10.1016/j.tree.2010.06.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mant R, Jones D, Reynolds B, Ormerod S. Pullin AS. What is the impact of “liming” of streams and rivers on the abundance and diversity of fish and invertebrate populations? Bangor, United Kingdom: Collaboration for Environmental Evidence; 2011. Systematic review 21. [Google Scholar]

- Martinez-Abrain A, Oro D, Jimenez J, Stewart G. Pullin A. A systematic review of the effects of recreational activities on nesting birds of prey. Basic and Applied Ecology. 2010;11:312–319. [Google Scholar]

- Maynard A. Chalmers I. Non-random reflections on health services research: on the 25th anniversary of Archie Cochrane’s effectiveness and efficiency. London: BMJ Publishing Group; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- McLeod LJ, Saunders GR. Kabat TJ. Do control interventions effectively reduce the impact of European Red Foxes on conservation values and agricultural production in Australia? Orange, New South Wales: Collaboration for Environmental Evidence; 2008. Systematic review 24. [Google Scholar]

- Meffe GK, Ehrenfeld D. Noss RF. Conservation biology at twenty. Conservation Biology. 2006;20:595–596. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1739.2006.00441.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulrow CD. Systematic reviews—rationale for systematic reviews. British Medical Journal. 1994;309:597–599. doi: 10.1136/bmj.309.6954.597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newton AC, Stewart GB, Diaz A, Golicher D. Pullin AS. Bayesian belief networks as a tool for evidence-based conservation management. Journal for Nature Conservation. 2007;15:144–160. [Google Scholar]

- Newton AC, Stewart GB, Myers G, Diaz A, Lake S, Bullock JM. Pullin AS. Impacts of grazing on lowland heathland in north-west Europe. Biological Conservation. 2009;142:935–947. [Google Scholar]

- Norris RH, Webb JA, Nichols SJ, Stewartson MJ. Harrison ET. Analyzing cause and effect in environmental assessments: using weighted evidence from the literature. Freshwater Science. 2012;31:5–21. [Google Scholar]

- Oro D. Martínez-Abraín A. Deconstructing myths on large gulls and their impact on threatened sympatric waterbirds. Animal Conservation. 2007;10:117–126. [Google Scholar]

- Peppin D, Fule PZ, Sieg CH, Beyers JL. Hunter ME. Post-wildfire seeding in forests of the western United States: an evidence-based review. Forest Ecology and Management. 2010;260:573–586. [Google Scholar]

- Petticrew M. Roberts H. Evidence, hierarchies, and typologies: horses for courses. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health. 2003;57:527–529. doi: 10.1136/jech.57.7.527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfeffer J. Sutton RI. Knowing “what” to do is not enough: turning knowledge into action. California Management Review. 1999;42:83–108. [Google Scholar]

- Pullin AS. Knight TM. Effectiveness in conservation practice: pointers from medicine and public health. Conservation Biology. 2001;15:50–54. [Google Scholar]

- Pullin AS. Knight TM. Assessing conservation management’s evidence base: a survey of management-plan compilers in the United Kingdom and Australia. Conservation Biology. 2005;19:1989–1996. [Google Scholar]

- Pullin AS. Knight TM. Doing more good than harm—building an evidence-base for conservation and environmental management. Biological Conservation. 2009;142:931–934. [Google Scholar]

- Pullin AS, Knight TM. Watkinson AR. Linking reductionist science and holistic policy using systematic reviews: unpacking environmental policy questions to construct an evidence-based framework. Journal of Applied Ecology. 2009;46:970–975. [Google Scholar]

- Pullin AS. Stewart GB. Guidelines for systematic review in conservation and environmental management. Conservation Biology. 2006;20:1647–1656. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1739.2006.00485.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radwan J, Biedrzycka A. Babik W. Does reduced MHC diversity decrease viability of vertebrate populations? Biological Conservation. 2010;143:537–544. doi: 10.1016/j.biocon.2009.07.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts PD. Pullin AS. The effectiveness of management options used for the control of Spartina species. Birmingham, United Kingdom: Collaboration for Environmental Evidence; 2006. Systematic Review No. 22. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts PD. Pullin AS. The effectiveness of management interventions used to control Ragwort species. Environmental Management. 2007a;39:691–706. doi: 10.1007/s00267-006-0039-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts PD. Pullin AS. The effectiveness of land-based schemes (incl. Agri-environment) at conserving farmland bird densities within the U.K. Bangor, United Kingdom: Collaboration for Environmental Evidence; 2007b. Systematic review 11. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts PD, Stewart GB. Pullin AS. Are review articles a reliable source of evidence to support conservation and environmental management? A comparison with medicine. Biological Conservation. 2006;132:409–423. [Google Scholar]

- Segan DB, Bottrill MC, Baxter PWJ. Possingham HP. Using conservation evidence to guide management. Conservation Biology. 2011;25:200–202. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1739.2010.01582.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Showler DA, Stewart GB, Sutherland WJ. Pullin AS. What is the impact of public access on the breeding success of ground-nesting and cliff-nesting birds? Norwich, United Kingdom: Collaboration for Environmental Evidence; 2010. Systematic Review 16. [Google Scholar]

- Smith RK, Pullin AS, Stewart GB. Sutherland WJ. Effectiveness of predator removal for enhancing bird populations. Conservation Biology. 2010;24:820–829. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1739.2009.01421.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith RK, Pullin AS, Stewart GB. Sutherland WJ. Is nest predator exclusion an effective strategy for enhancing bird populations? Biological Conservation. 2011;144:1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Stacey CJ, Springer AE. Stevens LE. Have arid land springs restoration projects been effective in storing hydrology, geomorphology, and invertebrate and plant species composition comparable to natural springs with minimal anthropogenic disturbance? Flagstaff, Arizona: Collaboration for Environmental Evidence; 2011. Systematic review 87. [Google Scholar]

- Stevens A, Milne R, Scally G, editors. Progress in public health. London: Royal Society of Medical Press; 1997. The effectiveness revolution and public health; pp. 197–255. [Google Scholar]

- Stewart GB, Coles CF. Pullin AS. Applying evidence-based practice in conservation management: lessons from the first systematic review and dissemination projects. Biological Conservation. 2005;126:270–278. [Google Scholar]

- Stewart GB. Pullin AS. The relative importance of grazing stock type and grazing intensity for conservation of mesotrophic “old meadow” pasture. Journal for Nature Conservation. 2008;16:175–185. [Google Scholar]

- Stewart GB, Pullin AS. Coles CF. Poor evidence-base for assessment of windfarm impacts on birds. Environmental Conservation. 2007a;34:1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Stewart GB, Pullin AS. Tyler C. The effectiveness of asulam for bracken (Pteridium aquilinum) control in the United Kingdom: a meta-analysis. Environmental Management. 2007b;40:747–760. doi: 10.1007/s00267-006-0128-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart GB, Bayliss HR, Showler DA, Sutherland WJ. Pullin AS. What are the effects of salmonid stocking in lakes on native fish populations and other fauna and flora? Systematic Review No. 13a. Bangor, United Kingdom: Collaboration for Environmental Evidence; 2007c. [Google Scholar]

- Stewart GB, Bayliss HR, Showler DA, Sutherland WJ. Pullin AS. Effectiveness of engineered in-stream structure mitigation measures to increase salmonid abundance: a systematic review. Ecological Applications. 2009a;19:931–941. doi: 10.1890/07-1311.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart GB, Kaiser MJ, Cote IM, Halpern BS, Lester SE, Bayliss HR. Pullin AS. Temperate marine reserves: global ecological effects and guidelines for future networks. Conservation Letters. 2009b;2:243–253. [Google Scholar]

- Sutherland WJ, Pullin AS, Dolman PM. Knight TM. The need for evidence-based conservation. Trends in Ecology & Evolution. 2004;19:305–308. doi: 10.1016/j.tree.2004.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Timonen J, Gustafsson L, Kotiaho JS. Mönkkönen M. Are woodland key habitats biodiversity hotspots in boreal forests? Jyväskylä, Finland: Collaboration for Environmental Evidence; 2011. Systematic review 81. [Google Scholar]

- Tyler C, Clark E. Pullin AS. Do management interventions effectively reduce or eradicate populations of the American Mink, Mustela vison. Birmingham, United Kingdom: Collaboration for Environmental Evidence; 2005. Systematic review 7. [Google Scholar]

- Tyler C, Pullin AS. Stewart GB. Effectiveness of management interventions to control invasion by Rhododendron ponticum. Environmental Management. 2006;37:513–522. doi: 10.1007/s00267-005-0127-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waylen KA, Fischer A, McGowan PJK, Thirgood SJ. Milner-Gulland EJ. Effect of local cultural context on the success of community-based conservation interventions. Conservation Biology. 2010;24:1119–1129. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1739.2010.01446.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webb JA, Wealands SR, Lea P, Nichols SJ, de Little SC, Stewartson MJ. Norris RH. Eco evidence: using the scientific literature to inform evidence-based decision making in environmental management. In: Chan F, Marinova D, editors; Anderssen SR, editor. 19th International congress on modelling and simulation. Perth, Australia: Modelling and Simulation Society of Australia and New Zealand; 2011. pp. 2472–2478. [Google Scholar]

- Whitlock EP, Lin JS, Chou R, Shekelle P. Robinson KA. Using existing systematic reviews in complex systematic reviews. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2008;148:776–782. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-148-10-200805200-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitten T, Holmes D. MacKinnon K. Conservation biology: A displacement behavior for academia? Conservation Biology. 2001;15:1–3. [Google Scholar]

- Young KD. Van Aarde RJ. Science and elephant management decisions in South Africa. Biological Conservation. 2011;144:876–885. [Google Scholar]

- Zavaleta E, Miller DC, Salafsky N, Fleishman E, Webster M, Gold B, Hulse D, Rowen M, Tabor G. Vanderryn J. Enhancing the engagement of the U.S. private foundations with conservation science. Conservation Biology. 2008;22:1477–1484. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1739.2008.01046.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.