Abstract

The HIV epidemic is an ongoing public health problem fueled, in part, by undertesting for HIV. When HIV-infected people learn their status, many of them decrease risky behaviors and begin therapy to decrease viral load, both of which prevent ongoing spread of HIV in the community.

Some physicians face barriers to testing their patients for HIV and would rather their patients ask them for the HIV test. A campaign prompting patients to ask their physicians about HIV testing could increase testing.

A mobile health (mHealth) campaign would be a low-cost, accessible solution to activate patients to take greater control of their health, especially populations at risk for HIV. This campaign could achieve Healthy People 2020 objectives: improve patient–physician communication, improve HIV testing, and increase use of mHealth.

World AIDS Day each December reminds us of the ongoing HIV epidemic in the United States and its disproportionate toll on racial and ethnic minority communities. HIV testing is an essential strategy to curb the ongoing epidemic. When people infected with HIV learn their status, many of them decrease risky behaviors to prevent spread to others1 and begin antiretroviral therapy to decrease viral load, the main biological predictor of the ongoing spread of HIV in the community.2 Despite national recommendations to make HIV testing routine for all adults,3–6 HIV testing rates—particularly among the racial and ethnic communities hardest hit—remain low.7 Patients want to be tested.8 However, physicians face numerous HIV testing barriers, including physician discomfort with initiating HIV testing discussions,9 physicians not realizing that patients expect HIV testing to be done,8 time,10,11 and competing clinical priorities.11,12

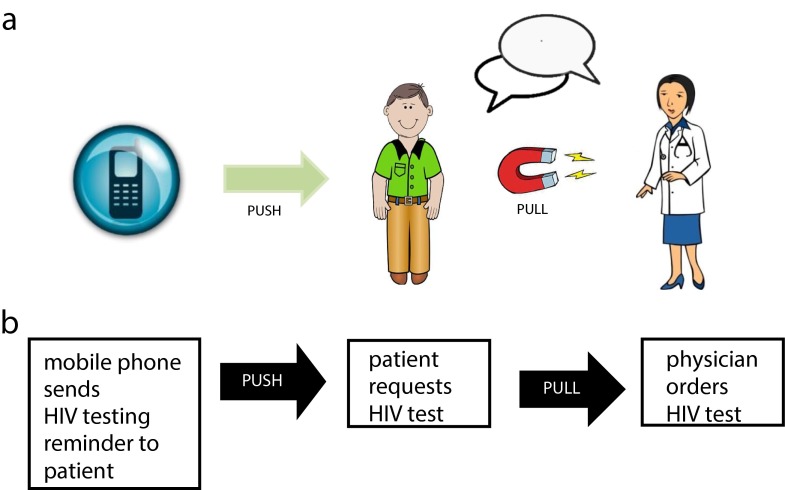

A pioneering intervention to improve HIV testing in health care settings may be a patient-initiated approach. The push–pull capacity model offers a framework to guide a solution to improve patient-initiated HIV testing.13,14 With a push–pull model, health information can be provided—or pushed—to many patients. This push creates a demand—or pull—for health services that address patient concerns. The ubiquity of cell phones and the pervasive use of text messaging provide an innovative platform for promoting an effective HIV testing campaign. Operationalizing the push–pull model through mobile health (mHealth) could be a novel approach to improving HIV testing in health care settings. This initiative would reduce demands on physicians, increase patients’ engagement in their own health, and address a significant ongoing public health problem.15 Goals of Healthy People 2020 include eliminating health disparities and increasing the number of people who have been tested for HIV.16

THE ONGOING US HIV EPIDEMIC

In the United States, more than one million people are infected with HIV,17 and approximately 50 000 new HIV infections occur yearly.18a People in the United States of lower socioeconomic status face a greater burden of HIV.18b Individuals who live below the poverty line are twice as likely to be infected with HIV as those who live above the poverty line.18

HIV also has a disproportional impact on racial and ethnic minorities in the United States. Despite making up only 14% and 16% of the US population, African Americans and Hispanics make up 44% and 19%, respectively, of those living with HIV.18 Despite the high prevalence of HIV in African American and Hispanic communities, African Americans and Hispanics make up a disproportionate share of those unaware of their HIV-positive status.7 Although nationally nearly 16% are unaware they are infected with HIV,18 22% of African Americans and 18% of Hispanics with HIV do not know they are infected because they have not been tested.7 In a national survey, 26% of African Americans and 44% of Hispanics reported never having been tested for HIV.19 When African Americans are finally tested, they are tested late: more than 46% of African Americans and more than 48% of Hispanics receive an AIDS diagnosis within three years of their initial HIV diagnosis.20 By contrast, 42% of Whites are diagnosed within three years of an HIV diagnosis.20

MISSED OPPORTUNITIES FOR HIV TESTING IN HEALTH CARE SETTINGS

Although the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)6 and professional medical societies3–5 have advocated routine HIV testing for all adults in high HIV prevalence health care settings since 2006, HIV testing is not widespread. HIV testing reached a peak of 39.8% of adults in 2009 but dropped to 34.7% in 2012.21 Many opportunities for HIV testing have been missed. In a 2012 national survey, 72% of participants noted that their health care provider had never suggested HIV testing to them.22 Additionally, studies in primary care settings in areas with high HIV prevalence have found that 74% of patients reported that their health care provider had not offered them HIV testing23 and 89% reported that their health care provider had never recommended HIV testing.24 Even when HIV indicators are present, many health care providers are not testing. In one study in which patients presented to care with clinical conditions suggestive of HIV, only 18% received a recommendation for HIV testing.25 A CDC report noted that patients who were diagnosed late with HIV had a median of four visits to a health care facility before their eventual HIV testing and diagnosis.26 Studies have found that of HIV-positive patients, more than 80% did not receive their diagnostic HIV test during their recent routine medical examination,27 and 71% had one or more health care encounters in the preceding year during which their health care provider did not test them for HIV.28

PATIENTS WANT TO BE TESTED BY THEIR PHYSICIANS

Numerous studies have shown that a health care provider’s recommendation to get tested for HIV can influence a patient’s decision to undergo testing.22,24,29–31 A recent national survey found that for more than one third of those surveyed, a health care provider’s recommendation to test for HIV was the reason they underwent HIV testing.22 Conversely, among participants who had never been tested for HIV, one third reported that not receiving a recommendation from a health care provider was the reason they had not been tested.22 Notably, some studies have found that patients in health care settings actually expect HIV testing to be done by their health care provider. In one study done in health care settings, nearly one in four patients expected that their provider would do HIV testing, and more than 40% of patients wanted their health care provider to do the testing.8 These findings highlight the importance of health care provider HIV testing recommendations for improving HIV testing in health care settings.

PUSH–PULL MODEL FOR IMPROVED HIV TESTING

Because of an ongoing need to improve HIV testing in the United States, in April 2013 the US Preventive Services Task Force recommended routine testing of all adolescents and adults aged 15 to 65 years.5 Given the limited success of the 2006 CDC HIV testing recommendations in making HIV testing a routine practice, for this 2013 recommendation to be realized in health care settings, a new paradigm is needed to engage both physicians and patients.6 One third of participants in a national survey reported wanting strategies to discuss HIV with their health care provider; only 46% had ever had a discussion about HIV with their health care provider.19 Furthermore, 42% wanted to know who should get tested for HIV.19

An innovative and successful strategy to improve HIV testing may be to activate the patient to initiate the discussion and request HIV testing. A recent survey found that 70% of physicians wanted their patients to ask them for an HIV test.32 Campaigns are needed that will push patients to pull their physicians to offer HIV testing. The push–pull capacity model is increasingly being recognized as important for adoption of evidence-based practices and improving public health outcomes.13,14 Push includes communicating health information to wide populations, and pull refers to creating demand for health services.13 In fact, when consumers are provided with the right information, they are then able to demand high-quality health care.15 A way to push health information to wide populations would be to use the media. Traditional media options include television, radio, and print, and new media options include the Internet, mobile phones, and social media.

A health campaign push–pull model using mobile phones—a near-universal media—could be used to create consumer demand for HIV testing in health care settings. In one study, nearly one in three patients felt that text messages about HIV prevention would be helpful.33 Periodic prompts delivered via media have been shown to be effective in reminding and motivating people to change health behaviors.34 Figure 1 illustrates how an mHealth campaign could remind and push the patient to engage and pull the physician into a discussion about HIV testing, thereby leading the physician to order the HIV test. Ideally, this mHealth campaign message using cell phones would be delivered when it is most relevant: just before a patient’s appointment with his or her physician. Notably, the health campaign push–pull model could also involve strategies that push the physician to offer HIV testing.

FIGURE 1—

Representation of an HIV testing push–pull model between patients and physicians using mobile health, both (a) graphically and (b) descriptively.

PROMISE OF MOBILE PHONES FOR AN mHEALTH CAMPAIGN

According to a National Institutes of Health Consensus Group, mHealth is the use of mobile devices to improve health research, services, and outcomes.35 Mobile phones are the most widely available and used new media technology for mHealth. Recent surveys have found that 91% of US adults own a mobile phone36 and 61% of mobile phone owners have smartphones, which have many of the functions of a computer.37 Mobile phone ownership is high even among racial and ethnic minority groups and across all education and income levels (Table 1).36 Because only 19% of smartphone users have health-related mobile applications,39 a text message–based mHealth campaign could have greater reach and impact. According to a 2013 national survey, text messaging is the most frequent activity done on a mobile phone, with 81% of US adults using their mobile phones to send and receive text messages.38 Text messaging is ubiquitous across race/ethnicity, education level, and household income (Table 1).38 Text messaging is also more frequently used than other forms of Internet messaging. Only 20% of e-mails are opened and 12% of Facebook feeds are viewed, whereas 99% of text messages are opened.40

TABLE 1—

Mobile Phone Ownership and Text Message Usage by Sociodemographic Characteristics: United States, 2013

| Sociodemographic Characteristic | Mobile Phone Ownership, % | Text Message Use, % |

| Race/ethnicity | ||

| African American | 93 | 85 |

| Hispanic | 88 | 87 |

| White | 90 | 79 |

| Education | ||

| Some college education | > 90 | > 80 |

| Without a college education | > 80 | > 70 |

| Income < $30 000 annually | 86 | 78 |

Because so many people own mobile phones and use text messaging, health campaign messages could be delivered to a large number of people at a time when the message is most relevant, for example near the time of a physician’s appointment. According to a recent survey, every 10 minutes one in five people check their phone and every 30 minutes one in four people check their phones.41 Unlike health campaigns using static media such as billboards and television, the portability of mobile phones and asynchronous nature of text messaging facilitate access of messages at a time convenient to the message receivers. Health text messages can be personalized or interactive, if desired, and these are salient features for health campaign promotion and effectiveness.42 As summarized by Cole-Lewis and Kershaw,43 text messaging offers great promise as a tool for improving health because it is commonly available, relatively low cost, in widespread use, and technologically easy to use and can be applicable to many health conditions. Studies have found that text message campaigns are successful at encouraging preventive health behaviors.42 In particular, text message interventions have been successful and engaging in promoting sexual health44 and HIV prevention.45

Although all of these qualities are attributes that make the mobile phone a highly effective option for a health campaign, only 9% of mobile phone owners say they receive text message updates or alerts about any health issue.39 Among those that do, African Americans are the most likely to receive health information via text.39 An mHealth solution may be ideal given that in a survey of more than 1000 patients, nearly one in three people felt that mHealth would offer them greater control of their health.46 Owing to the widespread ownership and use of mobile phones and their portability, people could conveniently and frequently access health text messages. On the basis of constructs from the health belief model of behavior change, which has been used to guide successful health communications campaigns,47 an mHealth campaign could provide self-efficacy and a cue to action for patients to talk to their doctors and be more engaged in their health. Further research is needed to understand what messages will stimulate behavior change.

IMPLEMENTING AN mHEALTH CAMPAIGN

A successful text message mHealth campaign should be locally driven. Locally driven campaigns can address the needs of the target audience and their specific health concerns, be tailored to the information technology (IT) infrastructure of the local health system, and therefore more directly engage the local community. Such a campaign would be managed by the health system’s IT department. This type of campaign could be implemented with minimal cost because the IT department could contract with companies such as SMS Marketing 360,48 Frontline SMS,49 or Magpi,50 which offer free text-messaging platforms. Because the IT department maintains records of patients’ appointments, they could therefore easily send a health text message concomitant with preexisting appointment reminders. This timing would facilitate a cue to action for patients to discuss the text message health content with their physician at the time of their appointment.

Additionally, physicians would encourage their own patients to sign up for this local mHealth campaign. Working with the IT department would facilitate personalized messages signed by the patient’s physician. A recent study found that patients would prefer campaigns promoted by their own health care provider.32 When physicians recommend health behaviors, patients are more likely to adopt these behaviors, thus improving their health. Such a campaign could be modeled after the Kaiser Permanente Mobile Storm campaign, which has successfully sent appointment reminders, treatment reminders, and notification of completed lab results.51 Another campaign prototype is the Oregon Reminders mHealth campaign.52 This campaign sends personalized messages regarding HIV and other sexually transmitted infection testing, appointment reminders, and prescription refills.52 Patient engagement campaigns could be further strengthened by also implementing parallel physician-targeted campaigns. These campaigns would remind busy physicians to offer patient-specific preventive health screenings recommended by national guidelines. Such physician-targeted campaigns could also be mHealth based or could be done through traditional avenues, such as academic conferences, electronic medical record reminders, or continuing medical education courses.

CONCLUSIONS

More than 30 years into the HIV epidemic, the infection is still spreading because many are unaware of their positive status as a result of testing rates remaining low. The current HIV epidemic is having a disproportionate impact on African American and Hispanic communities in the United States, in part because people have not been tested for HIV. “Communication inequalities based on education, income, race, and ethnicity are likely to influence what people know about health,”53(p833) and may be contributing to HIV testing and health disparities.53–55 Because of the widespread ownership and use of mobile phones—particularly among the populations most affected by HIV—mHealth is a promising avenue for reducing these inequalities and breaching the digital divide. Because only 0.3% of health-related mobile applications were dedicated to HIV and sexually transmitted infections in 2012,39,56 a mobile phone text message–based campaign may be an ideal solution to help mitigate the ongoing HIV epidemic by improving HIV testing. It is possible that an innovative patient-initiated health campaign promoting testing—in conjunction with physicians routinely offering HIV testing—may offer the synergy needed to improve HIV testing rates in health care settings and decrease the ongoing spread of HIV in the community. This type of intervention could facilitate improved patient–physician communication and increase the use of mHealth, both key objectives of the Healthy People 2020 goals.16

Given that many people with HIV remain unaware of their HIV infection and that the US Preventive Services Task Force recently recommended routine HIV testing of all people aged 15 to 65 years, novel strategies are needed to encourage more widespread HIV testing in health care settings.5 Cross-disciplinary partnerships between health and technology fields could catalyze innovative strategies. As noted by former US Secretary of Health and Human Services Kathleen Sebelius, mHealth is “the biggest technology breakthrough of our time,” which could empower traditionally hard-to-reach patient populations to take control of their own health.57 This underused technology offers great promise to improve the health of communities facing the greatest disease burdens.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the National Institute of Mental Health (grant MH094235-01A1; PI: M. A.). This work was also supported in part by the Center for Innovations in Quality, Effectiveness, and Safety (grant CIN 13-413), Michael E. DeBakey VA Medical Medical Center, Houston, TX.

We thank Ashley Phillips for her thoughtful comments on and editorial assistance with the article.

Note. The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the National Institutes of Health or of the US Department of Veterans Affairs.

References

- 1.Marks G, Crepaz N, Janssen RS. Estimating sexual transmission of HIV from persons aware and unaware that they are infected with the virus in the USA. AIDS. 2006;20(10):1447–1450. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000233579.79714.8d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cohen MS, Chen YQ, McCauley M et al. Prevention of HIV-1 infection with early antiretroviral therapy. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(6):493–505. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1105243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Qaseem A, Snow V, Shekelle P, Hopkins JR, Owens DK. Screening for HIV in health care settings: a guidance statement from the American College of Physicians and HIV Medicine Association. Ann Intern Med. 2009;150(2):125–131. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-150-2-200901200-00300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. American Medical Association. Opinion 2.23—HIV testing. 2010. Available at: http://www.ama-assn.org/ama/pub/physician-resources/medical-ethics/code-medical-ethics/opinion223.page. Accessed October 4, 2014.

- 5.Moyer VAUS Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for HIV: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement Ann Intern Med 2013159151–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Branson BM, Handsfield HH, Lampe AM et al. Revised recommendations for HIV testing of adults, adolescents, and pregnant women in health-care settings. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2006;55(RR-14):1–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Campsmith ML, Rhodes PH, Hall HI, Green TA. Undiagnosed HIV prevalence among adults and adolescents in the United States at the end of 2006. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2010;53(5):619–624. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181bf1c45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McAfee L, Tung C, Espinosa-Silva Y et al. A survey of a small sample of emergency department and admitted patients asking whether they expect to be tested for HIV routinely. J Int Assoc Provid AIDS Care. 2013;12(4):247–252. doi: 10.1177/2325957413488197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Simmons EM, Brown MJ, Sly K, Ma M, Sutton MY, McLellan-Lemal E. Barriers and facilitators to HIV testing in primary care among health care providers. J Natl Med Assoc. 2011;103(5):432–438. doi: 10.1016/s0027-9684(15)30340-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rizza SA, MacGowan RJ, Purcell DW, Branson BM, Temesgen Z. HIV screening in the health care setting: status, barriers, and potential solutions. Mayo Clin Proc. 2012;87(9):915–924. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2012.06.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Korthuis PT, Berkenblit GV, Sullivan LE et al. General internists’ beliefs, behaviors, and perceived barriers to routine HIV screening in primary care. AIDS Educ Prev. 2011;23(3 suppl):70–83. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2011.23.3_supp.70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Berkenblit GV, Sosman JM, Bass M et al. Factors affecting clinician educator encouragement of routine HIV testing among trainees. J Gen Intern Med. 2012;27(7):839–844. doi: 10.1007/s11606-012-1985-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Orleans CT. Increasing the demand for and use of effective smoking-cessation treatments—reaping the full health benefits of tobacco-control science and policy gains—in our lifetime. Am J Prev Med. 2007;33(6):S340–S348. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2007.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Curry SJ. Organizational interventions to encourage guideline implementation. Chest. 2000;118(2 suppl):40S–46S. doi: 10.1378/chest.118.2_suppl.40s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Steinhubl SR, Muse ED, Topol EJ. Can mobile health technologies transform health care? JAMA. 2013;310(22):2395–2396. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.281078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. US Department of Health and Human Services. Healthy People 2020. Available at: http://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/topics-objectives/2020-Topics-and-Objectives-Objectives-A-Z. Accessed October 4, 2014.

- 17. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV in the United States: at a glance. 2013. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/statistics_basics_factsheet.pdf. Accessed October 3, 2014.

- 18a. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV and AIDS in America: a snapshot. 2013. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/nchhstp/newsroom/docs/HIV-and-AIDS-in-America-A-Snapshot-508.pdf. Accessed October 4, 2014.

- 18b. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Today’s HIV epidemic. 2013. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/nchhstp/newsroom/docs/hivfactsheets/todaysepidemic-508.pdf. Accessed October 4, 2014.

- 19. Kaiser Family Foundation. Kaiser Family Foundation 2011 Survey of Americans on HIV/AIDS. Available at: http://kaiserfamilyfoundation.files.wordpress.com/2013/01/8186-t.pdf. Accessed October 4, 2014.

- 20.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Late HIV testing—34 states, 1996–2005. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2009;58(24):661–665. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Health Interview Survey. 2013. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nhis/earlyrelease/earlyrelease201303_10.pdf. Accessed October 4, 2014.

- 22. Washington Post; Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation. The Washington Post/Kaiser Family Foundation 2012 Survey of Americans on HIV/AIDS. Available at: http://kaiserfamilyfoundation.files.wordpress.com/2013/01/8334-t.pdf. Accessed October 4, 2014.

- 23.Arya M, Amspoker AB, Lalani N et al. HIV testing beliefs in a predominantly Hispanic community health center during the routine HIV testing era: does English language ability matter? AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2013;27(1):38–44. doi: 10.1089/apc.2012.0230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kim EK, Thorpe L, Myers JE, Nash D. Healthcare-related correlates of recent HIV testing in New York City. Prev Med. 2012;54(6):440–443. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2012.03.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liddicoat RV, Horton NJ, Urban R, Maier E, Christiansen D, Samet JH. Assessing missed opportunities for HIV testing in medical settings. J Gen Intern Med. 2004;19(4):349–356. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2004.21251.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Missed opportunities for earlier diagnosis of HIV infection—South Carolina, 1997-2005. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2006;55(47):1269–1272. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dorell CG, Sutton MY, Oster AM et al. Missed opportunities for HIV testing in health care settings among young African American men who have sex with men: implications for the HIV epidemic. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2011;25(11):657–664. doi: 10.1089/apc.2011.0203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chin T, Hicks C, Samsa G, McKellar M. Diagnosing HIV infection in primary care settings: missed opportunities. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2013;27(7):392–397. doi: 10.1089/apc.2013.0099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fernández MI, Bowen GS, Perrino T et al. Promoting HIV testing among never-tested Hispanic men: a doctor’s recommendation may suffice. AIDS Behav. 2003;7(3):253–262. doi: 10.1023/a:1025491602652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stefan MS, Blackwell JM, Crawford KM et al. Patients’ attitudes toward and factors predictive of HIV testing of academic medical clinics. Am J Med Sci. 2010;340(4):264–267. doi: 10.1097/MAJ.0b013e3181e59c3e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Petroll AE, DiFranceisco W, McAuliffe TL, Seal DW, Kelly JA, Pinkerton SD. HIV testing rates, testing locations, and healthcare utilization among urban African-American men. J Urban Health. 2009;86(1):119–131. doi: 10.1007/s11524-008-9339-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Arya M, Kallen MA, Street RL, Jr., Viswanath K, Giordano TP. African American patients’ preferences for a health center campaign promoting HIV testing: an exploratory study and future directions. J Int Assoc Provid AIDS Care. 2014 doi: 10.1177/2325957414529823. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Person AK, Blain ML, Jiang H, Rasmussen PW, Stout JE. Text messaging for enhancement of testing and treatment for tuberculosis, human immunodeficiency virus, and syphilis: a survey of attitudes toward cellular phones and healthcare. Telemed J E Health. 2011;17(3):189–195. doi: 10.1089/tmj.2010.0164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fry JP, Neff RA. Periodic prompts and reminders in health promotion and health behavior interventions: systematic review. J Med Internet Res. 2009;11(2):e16. doi: 10.2196/jmir.1138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. US Department of Health and Human Services. mHealth. 2013. Available at: http://www.webcitation.org/6FRD6pbPV. Accessed September 25, 2014.

- 36.Rainie L. Cell phone ownership hits 91% of adults. 2013. Available at: http://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2013/06/06/cell-phone-ownership-hits-91-of-adults/. Accessed October 4, 2014.

- 37. Smith A. Smartphone ownership—2013 update: Pew Research Center’s Internet & American Life Project. Available at: http://pewinternet.org/Reports/2013/Smartphone-Ownership-2013.aspx. Accessed October 4, 2014.

- 38. Duggan M. Cell phone activities 2013. Available at: http://www.pewinternet.org/files/old-media//Files/Reports/2013/PIP_Cell%20Phone%20Activities%20May%202013.pdf. Accessed October 4, 2014.

- 39. Fox S, Duggan M. Mobile health 2012. Available at: http://pewinternet.org/Reports/2012/Mobile-Health.aspx. Accessed October 4, 2014.

- 40. Yovanoff J. Infographic: How to Reach, Educate, and Enroll the Uninsured with Mobile. Mobile Commons; 2014. Available at: https://www.mobilecommons.com/resources/infographic-reach-educate-enroll-uninsured-mobile. Accessed September 16, 2014.

- 41. Gibbs N. Your life is fully mobile. Time Magazine; 2012. Available at: http://techland.time.com/2012/08/16/your-life-is-fully-mobile. Accessed October 4, 2014.

- 42.Fjeldsoe BS, Marshall AL, Miller YD. Behavior change interventions delivered by mobile telephone short-message service. Am J Prev Med. 2009;36(2):165–173. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2008.09.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cole-Lewis H, Kershaw T. Text messaging as a tool for behavior change in disease prevention and management. Epidemiol Rev. 2010;32(1):56–69. doi: 10.1093/epirev/mxq004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Levine D, McCright J, Dobkin L, Woodruff AJ, Klausner JD. SEXINFO: a sexual health text messaging service for San Francisco youth. Am J Public Health. 2008;98(3):393–395. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.110767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cornelius JB, Dmochowski J, Boyer C, St Lawrence J, Lightfoot M, Moore M. Text-messaging-enhanced HIV intervention for African American adolescents: a feasibility study. J Assoc Nurses AIDS Care. 2013;24(3):256–267. doi: 10.1016/j.jana.2012.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. PricewaterhouseCoopers. Emerging mHealth: paths for growth. 2012. Available at: http://www.pwc.com/en_GX/gx/healthcare/mhealth/assets/pwc-emerging-mhealth-exec-summary.pdf. Accessed October 4, 2014.

- 47. National Cancer Institute. Theory at a glance: application to health promotion and health behavior. Bethesda, MD: US Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health; 2005. NIH Pub. No. 05–3896. Available at: http://www.cancer.gov/cancertopics/cancerlibrary/theory.pdf. Accessed October 4, 2014.

- 48. SMS Marketing 360. Available at: http://www.smsmarketing360.com. Accessed April 27, 2014.

- 49. Frontline SMS. Available at: http://www.frontlinesms.com. Accessed April 27, 2014.

- 50. Magpi. Available at: http://www.magpi.org. Accessed September 16, 2014.

- 51. mobileStorm. Kaiser Permanente goes mobile with health care. 2013. Available at: http://www.mobilestorm.com/wp-content/uploads/CASE_STUDY_Kaiser_Permanente_v1-1.pdf. Accessed April 28, 2014.

- 52. Oregon Health Authority. Oregon reminders. Available at: http://www.oregonreminders.org. Accessed April 27, 2014.

- 53.Viswanath K. Science and society: the communications revolution and cancer control. Nat Rev Cancer. 2005;5(10):828–835. doi: 10.1038/nrc1718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Viswanath K. Public communications and its role in reducing and eliminating health disparities. In: Thomson G, Mitchell F, Williams F, editors. Examining the Health Disparities Research Plan of the National Institutes of Health: Unfinished Business. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2006. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Viswanath K, Ackerson LK. Race, ethnicity, language, social class, and health communication inequalities: a nationally-representative cross-sectional study. PLoS ONE. 2011;6(1):e14550. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0014550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Muessig KE, Pike EC, Legrand S, Hightow-Weidman LB. Mobile phone applications for the care and prevention of HIV and other sexually transmitted diseases: a review. J Med Internet Res. 2013;15(1):e1. doi: 10.2196/jmir.2301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Sebelius K. mHealth Summit keynote address. Available at: http://www.cancer.gov/ncicancerbulletin/121311/page4. Accessed November 15, 2013.