Abstract

Objectives. We examined mental health treatment patterns among adults with suicide attempts in the past 12 months in the United States.

Methods. We examined data from 2000 persons, aged 18 years or older, who participated in the 2008 to 2012 National Survey on Drug Use and Health and who reported attempting suicide in the past 12 months. We applied descriptive analyses and multivariable logistic regression models.

Results. In adults who attempted suicide in the past year, 56.3% received mental health treatment, but half of those who received treatment perceived unmet treatment needs, and of the 43.0% who did not receive mental health treatment, one fourth perceived unmet treatment needs. From 2008 to 2012, the mental health treatment rate among suicide attempters remained unchanged. Factors associated with receipt of mental health treatment varied by perceived unmet treatment need and receipt of medical attention that resulted from a suicide attempt.

Conclusions. Suicide prevention strategies that focus on suicide attempters are needed to increase their access to mental health treatments that meet their needs. To be effective, these strategies need to account for language and cultural differences and barriers to financial and treatment delivery.

More than 38 000 deaths were by suicide in the United States in 2010.1,2 A suicide attempt history is the strongest known clinical predictor for death by suicide.3,4 In 2012, more than 1.3 million adults aged 18 years or older (0.6%) reported that they attempted suicide in the past year.5 Mental health treatment could play a critical role in reducing suicide risk among suicide attempters.3,6–8 Promising interventions for people who attempt suicide have been developed over the past decade.6 However, many suicide attempters do not receive mental health treatment. Approximately 40% of previous 12-month suicide attempters did not receive mental health treatment in the United States in 2001 to 20039 and 2008 to 2009.10 Even in Canada, which has 1 national health care system and universal insurance coverage, approximately 40% of past 12-month suicide attempters did not receive mental health treatment in 2002.11 Thus, it is crucial to better understand mental health treatment patterns among past 12-month suicide attempters.

A few studies in the United States9,12,13 and 1 in Canada11 estimated mental health treatment rates among past 12-month suicide attempters. However, none of the existing studies examined the intensity of outpatient mental health visits and the length of stay of inpatient psychiatric treatment received by adults with recent suicide attempts in the United States. Moreover, little is known about barriers to mental health treatment in this high-risk group.

Little is known about the mental health treatment patterns among suicide attempters who received medical attention that resulted from a suicide attempt. A recent study indicated that an adverse physical health event increases mental health treatment among community-dwelling adults,14 but the applicability of this finding to adult suicide attempters is uncertain. None of the existing studies have examined whether chronic physical health conditions (e.g., heart disease, hypertension, asthma, and diabetes), emergency room (ER) visits, and receipt of medical attention resulting from a suicide attempt affected the receipt of mental health treatment among adult suicide attempters. It is unknown whether and how characteristics associated with receiving mental health treatment among suicide attempters varied by their perceived unmet treatment needs and by whether they received medical attention resulting from a suicide attempt.

Although substance use disorders (SUDs) increase the risk of suicide attempts,15,16 it is unknown whether SUDs influence receipt of mental health treatment among adult suicide attempters. Little is known about the association between the receipt of substance use treatment and receipt of mental health treatment among adult suicide attempters. Although recent involvement with the criminal justice system elevates the risk of suicide attempts,17 none of the existing studies have examined whether the number of times a person was arrested or booked affected receipt of mental health treatment among suicide attempters. In addition, none of the existing studies examined trends in mental health treatment rates among adult suicide attempters over the past 5 years. Finally, because approximately 60% of adults with past-year suicide attempts received mental health treatment in the past 12 months, the results from the existing studies11,13 on the factors associated with receipt of mental health treatment, which are based on odds ratios rather than risk ratios, might overestimate association magnitudes.18–21

Thus, using recent nationally representative data, we examined the following understudied questions:

What was the intensity of mental health treatment received by adults who had past 12-month suicide attempts?

What were the prevalence and correlates of receiving mental health treatment in the past 12 months among this population?

Did characteristics associated with receiving mental health treatment among adults with past 12-month suicide attempts vary by their perceived unmet treatment needs and receipt of medical attention resulting from a suicide attempt?

Were there trends in mental health treatment rates among this population from 2008 to 2012?

What were the self-reported reasons for not receiving mental health treatment by adult suicide attempters with perceived unmet treatment needs?

Addressing these gaps in knowledge could help develop effective suicide prevention, promote mental health treatment among adult suicide attempters, and reduce their overall risk of death by suicide.

METHODS

We examined data from 2000 persons, aged 18 years or older, who participated in the 2008 to 2012 National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH) and who reported having attempted suicide in the previous 12 months before the survey interview. NSDUH is conducted by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. It provides nationally representative data on suicide behavior and mental health treatment in the civilian, noninstitutionalized population aged 18 years or older in the United States. Data were collected by interviewers during in-person visits to households and noninstitutional group quarters. Audio computer-assisted, self-administered interviewing was used, which provided respondents with a private, confidential way to record answers.22,23

Measures

Suicide plan and attempts.

The 2008 to 2012 NSDUH questionnaires asked all adult respondents if at any time during the past 12 months they had thought seriously about trying to kill themselves. Those who reported that they had suicidal ideation were then asked if they made a plan to kill themselves, and if they tried to kill themselves in the past 12 months. Respondents with past 12-month suicide attempts were asked if they received medical attention resulting from a suicide attempt in the past 12 months.

Indicators of physical and mental health status.

The 2008 to 2012 NSDUH captured a respondent’s self-rated health and the number of ER visits (for any reason) in the past year. NSDUH assessed whether a respondent had a past 12-month major depressive episode (MDE) and SUD (alcohol, or illicit drug dependence or abuse) according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition criteria.24 NSDUH asked adult respondents if they were told by a doctor or other health professional that they had hypertension, heart disease, diabetes, and asthma in the past year. Data on these measures had good validity and reliability.25–27

Mental health treatment intensity and self-perceived unmet treatment need.

The 2008 to 2012 NSDUH asked all adults to report the number of visits to outpatient mental health treatment, the number of nights of inpatient mental health treatment, and receipt of prescription medications for mental health problems in the past year; however, the NSDUH did not collect the temporal order between the receipt of mental health treatment and suicide attempt. In addition, the NSDUH asked all respondents whether they perceived unmet needs for mental health treatment in the past 12 months (yes or no).

Receipt of substance use treatment.

NSDUH respondents were asked if they received treatment in the past 12 months for illicit drug or alcohol use at a hospital, a residential drug or alcohol rehabilitation facility, a drug or alcohol rehabilitation facility, a mental health facility, an ER, a private doctor’s office, or a prison or jail.

Sociodemographic characteristics.

We examined age, gender, race/ethnicity, education status, marital status, employment status, health insurance, family income (as a percentage of the federal poverty level using the US Census Bureau's poverty thresholds for the corresponding year: < 100%, 100%–199%, and ≥ 200%), metropolitan statistical area (yes or no), and region. We also assessed the number of times a respondent was arrested or booked in the past year.

Survey year.

We examined trends in mental health treatment rates among adults with past 12-month suicide attempts from 2008 to 2012.

Statistical Analyses

We used descriptive analyses to assess mental health treatment intensity, mental health treatment rates, self-perceived unmet need for mental health treatment, and receipt of medical attention resulting from a suicide attempt in adults with past 12-month suicide attempts.

We applied bivariate logistic regression modeling to investigate factors associated with receipt of mental health treatment in adults with past 12-month suicide attempts. We selected significant factors at the bivariate level for the multivariable logistic regression modeling. We examined significant potential interactions on receipt of mental health treatment. Using the variance inflation factors, we assessed multicollinearity during multivariable modeling. We did not find multicollinearity problems in the final multivariable model.

Using PREDMARG and PRED_EFF statements in SUDAAN,21,28 we obtained model-adjusted risk ratios (MARRs) from average marginal predictions in the final multivariable model. The final multivariable logistic regression pooled model identified 3 significant interactions: MDE and perceived unmet treatment need (P < .001), perceived unmet treatment need and receipt of medical attention (resulting from a suicide attempt; P = .007), and MDE and receipt of medical attention (P = .002). To better understand how these factors were associated with receipt of mental health treatment, we conducted stratified multivariable models by perceived unmet treatment need and receipt of medical attention. We used SUDAAN software28 to account for NSDUH’s complex sample design and sampling weights for all analyses.

RESULTS

Among adults with past 12-month suicide attempts, 56.3% received mental health treatment at some point during the year, but half of those who received treatment perceived unmet treatment needs. Among those who did not receive mental health treatment, almost one fourth perceived unmet treatment needs. Table 1 shows that among adults with past 12-month suicide attempts in the United States, 28.1% received mental health treatment but still perceived unmet treatment needs, 28.2% received mental health treatment but did not perceive unmet treatment needs, 33.4% neither received mental health treatment nor perceived unmet treatment needs, and 9.6% did not receive mental treatment but perceived unmet treatment needs in the past 12 months.

TABLE 1—

Receipt of Mental Health Treatment, Perceived Unmet Need for Mental Health Treatment, and Receipt of Medical Attention Resulting in Past Year Suicide Attempters: National Survey on Drug Use and Health, United States, 2008–2012

| Receipt of Mental Health Treatment, Unmet Need, Emergency Room Visit, and Medical Attention | %a (SE) |

| Receipt of mental health treatment and unmet need in the past year | |

| Received treatment and did not perceive unmet need | 28.2 (1.84) |

| Received treatment and perceived unmet need | 28.1 (1.70) |

| Did not receive treatment, but perceived unmet need | 9.6 (0.96) |

| Did not receive treatment and did not perceive unmet need | 33.4 (1.97) |

| Total no. of outpatient visits for mental health treatment in the past year | |

| 0 | 59.4 (2.05) |

| 1–2 | 6.6 (0.91) |

| 3–4 | 9.2 (1.01) |

| 5–8 | 7.9 (1.19) |

| 9–12 | 5.9 (1.06) |

| 13–20 | 7.8 (1.11) |

| ≥ 21 | 3.3 (1.02) |

| Total no. of nights as inpatient mental health treatment in the past year | |

| 0 | 71.2 (1.99) |

| 1–3 | 8.4 (1.21) |

| 4–8 | 9.3 (1.28) |

| 9–20 | 9.3 (1.18) |

| ≥ 21 | 1.8 (0.91) |

| No. of visits to community mental health center in the past year | |

| 0 | 79.9 (1.74) |

| 1–2 | 3.4 (0.55) |

| 3–6 | 5.4 (0.91) |

| 7–12 | 3.5 (0.91) |

| 13–20 | 2.9 (0.81) |

| ≥ 21 | 2.4 (0.61) |

| Unknown | 2.5 (0.97) |

| No. of visits to private therapist’s office (psychologist, psychiatrist, social worker, counselor) for mental health treatment in the past year | |

| 0 | 81.4 (1.67) |

| 1–2 | 2.4 (0.66) |

| 3–6 | 3.4 (0.58) |

| 7–12 | 3.5 (0.66) |

| 13–20 | 2.3 (0.62) |

| ≥ 21 | 4.8 (0.95) |

| Unknown | 2.2 (0.94) |

| No. of visits to non-clinic doctor office for mental health treatment in the past year | |

| 0 | 93.0 (1.17) |

| 1–2 | 1.6 (0.42) |

| 3–6 | 1.3 (0.32) |

| ≥ 7 | 2.6 (0.70) |

| No. of visits to outpatient medical clinic for mental health treatment in the past year | |

| 0 | 95.0 (1.12) |

| 1–2 | 2.1 (0.60) |

| 3–6 | 1.3 (0.39) |

| ≥ 7 | 1.7 (0.89) |

| No. of visits to day treatment program for mental health treatment in the past year | |

| 0 | 96.5 (0.97) |

| ≥ 1 | 2.0 (0.41) |

| No. of outpatient visits to other type of facility for mental health treatment in the past year | |

| 0 | 96.4 (0.90) |

| 1–4 | 1.5 (0.34) |

| ≥ 5 | 0.7 (0.20) |

| No. of nights in psychiatric unit of general hospital for mental health treatment in the past year | |

| 0 | 88.1 (1.28) |

| 1–3 | 3.4 (0.76) |

| ≥ 4 | 7.9 (1.13) |

| No. of nights in psychiatric hospital for mental health treatment in the past year | |

| 0 | 89.5 (1.37) |

| 1–8 | 5.2 (0.85) |

| ≥ 9 | 3.7 (0.71) |

| Unknown | 1.6 (0.90) |

| No. of nights in medical unit of general hospital for mental health treatment in the past year | |

| 0 | 93.3 (1.25) |

| ≥ 1 | 5.3 (0.93) |

| No. of nights in another type of hospital for mental health treatment in the past year | |

| 0 | 97.3 (0.75) |

| ≥ 1 | 2.1 (0.71) |

| No. of nights in residential treatment center for mental health treatment in the past year | |

| 0 | 97.8 (0.52) |

| ≥ 1 | 1.6 (0.46) |

| No. of nights in other type of facility for mental health treatment in the past year | |

| 0 | 97.5 (0.75) |

| ≥ 1 | 1.9 (0.71) |

| Received prescription medication for mental health treatment in the past year | |

| Yes | 48.6 (2.09) |

| No | 51.4 (2.09) |

| Emergency room visits for any treatment in the past year | |

| None | 33.9 (1.94) |

| 1 | 24.4 (1.85) |

| 2 | 16.1 (1.30) |

| ≥ 3 | 25.6 (2.00) |

| Receipt of medical attention as a result of a suicide attempt | |

| Yes | 60.3 (1.86) |

| No | 39.7 (1.86) |

| Stayed overnight or longer in a hospital as a result of a suicide attempt | |

| Yes | 43.2 (2.07) |

| No | 56.8 (2.07) |

Note. Annual average weighted percentages. Because of missing data, the categories of a variable may not add up to 100%. The sample size was n = 2000.

The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration requires that any description of overall sample sizes based on the restricted-use data files has to be rounded to the nearest 100, which intends to minimize the potential disclosure risk.

Mental Health Treatment Intensity

Table 1 also reveals that among past 12-month suicide attempters, 59.4% did not have an outpatient visit for mental health treatment in the past 12 months; 15.8% had 1 to 4 outpatient mental health visits, 13.8% had 5 to 12 outpatient mental health visits, and 7.8% had 13 to 20 outpatient mental health visits in the past year. A community mental health center was a common location that provided outpatient mental health services for adults with past 12-month suicide attempts: 8.8% of suicide attempters had 1 to 6 visits and 6.4% had 7 to 20 visits to a community mental health center in the past year. A private therapist’s office (psychologist, psychiatrist, social work, or counselor) was another common location that provided outpatient mental health treatment of adults with past 12-month suicide attempts: 5.8% had 1 to 6 visits, and 5.8% had 7 to 20 visits in the past year.

Among past 12-month suicide attempters, 71.2% did not receive inpatient psychiatric treatment; 8.4% stayed 1 to 3 nights, 9.3% stayed 4 to 8 nights, and 9.3% stayed 9 to 20 nights for inpatient mental health treatment in the past year. Only 11.3% of adults with past 12-month suicide attempts received inpatient mental health treatment at a psychiatric unit of a general hospital: 3.4% stayed for 1 to 3 nights, and 7.9% stayed for more than 3 nights in the past year. Approximately 8.9% of adults with past 12-month suicide attempts received inpatient mental health treatment at a psychiatric hospital: 5.2% stayed 1 to 8 nights; and 3.7% stayed more than 8 nights in the past year.

Mental Health Treatment Rates by Factors

Table 2 shows that among adults who attempted suicide in the past year, receipt of past 12-month mental health treatment was lower among non-Hispanic Blacks and Hispanics than among non-Hispanic Whites (39.7% and 44.4% vs 65.8%). Among adults with past 12-month suicide attempts, receipt of mental health treatment was lower among uninsured adults than among adults with private insurance only, Medicare beneficiaries, and Medicaid-only beneficiaries (44.7% vs 56.0%, 67.6%, and 64.8%, respectively), and was lower among adults with full-time employment than among those who did not work because of disability (44.1% vs 88.2%, respectively).

TABLE 2—

Receipt of Mental Health Treatment in the Past 12 Months Among Persons Aged 18 Years or Older Who Attempted Suicide in the Past Year: National Survey on Drug Use and Health, United States, 2008–2012

| Characteristics | Weighted Distribution of the Study Samplea (SE) | Annual Average Weighted Percentage of Receipt Mental Health Treatment (SE) | Unadjusted RR for Receipt of Mental Health Treatment (95% CI) |

| Age, y | |||

| 18–25 | 36.7 (1.64) | 46.6 (1.79) | 0.8 (0.64, 0.99) |

| 26–50 | 40.7 (1.99) | 64.6 (3.51) | 1.1 (0.88, 1.38) |

| > 51 | 22.6 (2.32) | 60.4 (4.99) | 1.0 (Ref) |

| Gender | |||

| Male | 41.9 (2.02) | 51.5 (3.13) | 1.0 (Ref) |

| Female | 58.1 (2.02) | 60.5 (2.70) | 1.2 (1.02–1.48) |

| Race/ethnicity | |||

| Non-Hispanic White | 59.8 (1.93) | 65.8 (2.54) | 1.0 (Ref) |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 17.0 (1.40) | 39.7 (4.85) | 0.6 (0.47, 0.78) |

| Non-Hispanic other | 8.2 (1.30) | 48.3 (8.04) | 0.7 (0.53, 1.03) |

| Hispanic | 15.1 (1.35) | 44.4 (4.85) | 0.7 (0.54, 0.85) |

| Education | |||

| < high school | 24.4 (1.64) | 54.4 (3.79) | 1.0 (0.74, 1.31) |

| High school graduate | 35.9 (1.84) | 54.8 (3.15) | 1.0 (0.75, 1.30) |

| Some college | 26.4 (1.82) | 62.1 (3.97) | 1.1 (0.85, 1.48) |

| College graduate | 13.4 (1.82) | 55.4 (7.14) | 1.0 (Ref) |

| Health insurance | |||

| Private only | 33.9 (1.98) | 56.0 (3.42) | 1.3 (1.04, 1.52) |

| Medicare | 14.3 (1.12) | 67.6 (6.46) | 1.5 (1.19, 1.93) |

| Medicaid only | 19.0 (1.54) | 64.8 (3.86) | 1.5 (1.21, 1.74) |

| No insurance coverage | 25.9 (1.75) | 44.7 (3.47) | 1.0 (Ref) |

| Other | 6.9 (1.03) | 60.8 (8.01) | 1.4 (1.01, 1.84) |

| Employment status | |||

| Full time | 30.3 (1.86) | 44.1 (3.40) | 1.0 (Ref) |

| Part time | 17.3 (1.70) | 53.0 (5.38) | 1.2 (0.93, 1.55) |

| Disabled for work | 19.6 (1.80) | 88.2 (3.32) | 2.0 (1.69, 2.37) |

| Unemployed | 13.1 (0.99) | 44.6 (4.12) | 1.0 (0.80, 1.29) |

| Other | 19.6 (1.65) | 55.8 (4.85) | 1.3 (1.01, 1.59) |

| Family income, % federal poverty levelb | |||

| < 100% | 31.2 (1.91) | 59.5 (3.53) | 1.0 (Ref) |

| 100%–199% | 25.4 (1.55) | 53.4 (3.98) | 0.9 (0.74, 1.08) |

| ≥ 200% | 42.8 (2.05) | 56.7 (3.23) | 1.0 (0.81, 1.12) |

| Marital status | |||

| Married | 27.1 (2.01) | 56.8 (4.80) | 1.1 (0.93, 1.36) |

| Widowed | 3.2 (0.81) | 52.8 (12.86) | 1.0 (0.65, 1.70) |

| Divorced/separated | 21.6 (1.88) | 71.2 (5.16) | 1.4 (1.20, 1.67) |

| Never married | 48.1 (1.96) | 50.4 (2.20) | 1.0 (Ref) |

| Metropolitan statistical area | |||

| Yes | 82.8 (1.41) | 55.4 (2.32) | 0.9 (0.75, 1.03) |

| No | 17.2 (1.41) | 63.1 (4.37) | 1.0 (Ref) |

| Region | |||

| Northeast | 17.8 (1.68) | 57.8 (4.70) | 1.1 (0.88, 1.43) |

| Midwest | 24.2 (1.60) | 65.2 (3.36) | 1.3 (1.03, 1.56) |

| South | 33.8 (1.80) | 53.8 (3.26) | 1.0 (0.84, 1.30) |

| West | 24.2 (1.91) | 51.5 (4.89) | 1.0 (Ref) |

| Hypertension | |||

| Yes | 22.0 (1.93) | 61.9 (5.43) | 1.1 (0.93, 1.35) |

| No | 78.0 (1.93) | 55.3 (2.08) | 1.0 (Ref) |

| Heart disease | |||

| Yes | 5.4 (1.17) | 71.9 (9.13) | 1.3 (0.99, 1.67) |

| No | 94.6 (1.17) | 55.9 (2.05) | 1.0 (Ref) |

| Diabetes | |||

| Yes | 8.5 (1.34) | 62.5 (8.44) | 1.1 (0.85, 1.46) |

| No | 91.5 (1.34) | 56.2 (2.06) | 1.0 (Ref) |

| Asthma | |||

| Yes | 18.3 (1.42) | 64.9 (4.02) | 1.2 (1.02, 1.37) |

| No | 81.7 (1.42) | 54.9 (2.28) | 1.0 (Ref) |

| Number of physical health conditions in the past year | |||

| 0 | 54.8 (2.01) | 53.1 (2.39) | 1.0 (Ref) |

| 1 | 32.0 (2.00) | 55.1 (3.96) | 1.0 (0.88, 1.23) |

| ≥ 2 | 13.2 (1.57) | 75.8 (4.95) | 1.4 (1.22, 1.67) |

| Self-rated health | |||

| Excellent | 12.1 (1.29) | 38.9 (5.38) | 1.0 (Ref) |

| Very good | 23.2 (1.49) | 48.4 (3.48) | 1.2 (0.92, 1.69) |

| Good | 31.1 (1.80) | 58.2 (3.34) | 1.5 (1.11, 2.01) |

| Fair/poor | 33.6 (2.07) | 67.6 (4.17) | 1.7 (1.30, 2.33) |

| Major depressive episode | |||

| Yes | 28.6 (1.94) | 75.1 (2.15) | 2.1 (1.75, 2.41) |

| No | 71.4 (1.94) | 36.3 (2.78) | 1.0 (Ref) |

| Past year substance use disorder | |||

| Illicit drug use disorder | 7.7 (0.95) | 68.2 (4.90) | 1.3 (1.06, 1.51) |

| Alcohol use disorder | 15.8 (1.28) | 57.6 (4.07) | 1.1 (0.92, 1.29) |

| Both illicit drug and alcohol use disorder | 11.4 (1.00) | 62.4 (4.22) | 1.2 (0.99, 1.40) |

| None | 65.1 (1.79) | 54.2 (2.76) | 1.0 (Ref) |

| Received substance use treatment | |||

| Yes | 10.8 (1.27) | 85.5 (3.17) | 1.6 (1.47, 1.81) |

| No | 89.2 (1.27) | 53.2 (2.12) | 1.0 (Ref) |

| Had a suicide plan in the past year | |||

| Yes | 79.5 (1.58) | 55.9 (2.29) | 0.9 (0.80, 1.09) |

| No | 20.5 (1.58) | 59.8 (3.96) | 1.0 (Ref) |

| Emergency room visits for any treatment in the past year | |||

| None | 33.9 (1.94) | 36.1 (2.99) | 1.0 (Ref) |

| 1 | 24.4 (1.85) | 66.5 (3.93) | 1.8 (1.51, 2.25) |

| 2 | 16.1 (1.30) | 54.2 (4.06) | 1.5 (1.21, 1.87) |

| ≥ 3 | 25.6 (2.00) | 75.7 (3.66) | 2.1 (1.71, 2.48) |

| Received medical attention as a result of suicide attempt | |||

| Yes | 60.3 (1.86) | 67.7 (2.95) | 1.7 (1.45, 1.96) |

| No | 39.7 (1.86) | 40.1 (2.48) | 1.0 (Ref) |

| Perceived unmet need for mental health treatment | |||

| Yes | 38.0 (1.85) | 74.6 (2.33) | 1.6 (1.43, 1.85) |

| No | 62.0 (1.85) | 45.8 (2.70) | 1.0 (Ref) |

| Number of times arrested or booked in the past year | |||

| 0 | 82.1 (1.46) | 55.0 (2.26) | 1.0 (Ref) |

| 1 | 9.3 (1.10) | 59.4 (6.04) | 1.1 (0.87, 1.34) |

| ≥ 2 | 6.5 (0.90) | 71.4 (5.55) | 1.3 (1.09, 1.54) |

| Unknown | 2.1 (0.50) | 66.6 (9.54) | 1.2 (0.91, 1.62) |

| Survey year | |||

| 2008 | 19.2 (1.68) | 62.7 (4.26) | 1.2 (0.95, 1.42) |

| 2009 | 18.3 (1.53) | 61.5 (4.30) | 1.1 (0.94, 1.40) |

| 2010 | 19.8 (1.65) | 52.6 (4.79) | 1.0 (0.77, 1.24) |

| 2011 | 20.0 (1.70) | 54.1 (4.74) | 1.0 (0.80, 1.26) |

| 2012 | 22.7 (1.60) | 54.0 (4.18) | 1.0 (Ref) |

Note. CI = confidence interval; RR = risk ratio. Annual average percentages, unadjusted analyses. The sample size was n = 2000.

The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration requires that any description of overall sample sizes based on the restricted-use data files has to be rounded to the nearest 100, which intends to minimize potential disclosure risk.

Federal poverty level according to the US Census Bureau's poverty thresholds for the corresponding year.

Among adults who attempted suicide in the past year, receipt of past 12-month mental health treatment was higher among those with MDEs than among those without MDEs (75.1% vs 36.3%). Mental health treatment was also higher among those with past-year substance use treatment than among those without treatment (85.5% vs 53.2%), and was higher among those who received medical attention resulting from a suicide attempt than among those who did not receive medical attention (67.7% vs 40.1%). Among adults who attempted suicide in the past year, receipt of past 12-month mental health treatment was higher among those who perceived unmet treatment needs than among those who did not perceive treatment needs (74.6% vs 45.8%). Overall, the mental health treatment rate was statistically unchanged during 2008 throughout 2012 (54.0%–62.7%).

Correlates of Receipt of Mental Health Treatment

Table 3 shows the results of the pooled multivariable logistic regression model (main effects only) and the stratified multivariable models by perceived unmet treatment needs and receipt of medical attention resulting from a suicide attempt. We summarize the main multivariable findings in the following.

TABLE 3—

Multivariable Logistic Regression Showing Factors Associated With Receipt of Mental Health Treatment in the Past 12 Months Among Adults With Past 12-Month Suicide Attempts: National Survey on Drug Use and Health, United States, 2008–2012

| Covariates | Received Mental Health Treatment vs Did Not Receive Mental Health Treatment (n = 2000) MARR (95% CI) | Received Treatment and Perceived Unmet Need vs Did Not Receive Treatment but Perceived Unmet Need (n = 800) MARR (95% CI) | Received Treatment but Did Not Perceive Unmet Need vs Neither Received Treatment nor Perceived Unmet Need (n = 1200) MARR (95% CI) | Received Mental Health Treatment and Medical Attention vs Did Not Receive Treatment but Received Medical Attention (n = 900) MARR (95% CI) | Received Mental Health Treatment but Did Not Receive Medical Attention vs Received Neither Mental Health Treatment nor Medical Attention (n = 1100) MARR (95% CI) |

| Age, y | |||||

| 18–25 | 1.1 (0.94, 1.39) | 1.0 (0.78, 1.31) | 1.3 (0.96, 1.67) | 1.1 (0.95, 1.27) | 1.2 (0.62, 2.29) |

| 26–50 | 1.3 (1.05, 1.52) | 1.1 (0.86, 1.42) | 1.3 (1.04, 1.72) | 1.1 (0.98, 1.28) | 1.6 (0.82, 3.01) |

| > 51 (Ref) | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Gender | |||||

| Male | 1.0 (0.90, 1.11) | 1.0 (0.95, 1.15) | 1.0 (0.86, 1.17) | 1.0 (0.93, 1.09) | 1.0 (0.80, 1.29) |

| Female (Ref) | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Race/ethnicity | |||||

| Non-Hispanic White (Ref) | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 0.7 (0.59, 0.80) | 0.9 (0.77, 0.97) | 0.6 (0.44, 0.73) | 0.8 (0.73, 0.90) | 0.5 (0.36, 0.75) |

| Non-Hispanic other | 0.9 (0.80, 1.11) | 1.0 (0.78, 1.20) | 1.0 (0.76, 1.19) | 0.9 (0.77, 1.11) | 1.0 (0.69, 1.41) |

| Hispanic | 0.8 (0.67, 0.95) | 0.8 (0.75, 0.97) | 0.8 (0.56, 1.01) | 0.9 (0.73, 1.00) | 0.7 (0.46, 0.99) |

| Health insurance | |||||

| Private insurance only | 1.2 (1.11, 1.40) | 1.1 (0.96, 1.16) | 1.5 (1.24, 1.87) | 1.1 (0.99, 1.26) | 1.5 (1.16, 1.97) |

| Medicare | 1.2 (0.96, 1.56) | 1.0 (0.77, 1.36) | 1.6 (1.11, 2.27) | 1.2 (0.99, 1.39) | 1.6 (0.85, 3.04) |

| Medicaid only | 1.2 (1.04, 1.40) | 1.0 (0.87, 1.21) | 1.5 (1.15, 1.91) | 1.2 (1.01, 1.41) | 1.2 (0.82, 1.65) |

| No insurance coverage (Ref) | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Other | 1.2 (0.97, 1.49) | 1.1 (0.98, 1.27) | 1.3 (0.93, 1.95) | 1.1 (0.93, 1.32) | 1.7 (1.19, 2.29) |

| Employment status | |||||

| Full time (Ref) | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Part time | 1.2 (1.03, 1.37) | 1.1 (0.94, 1.23) | 1.3 (1.06, 1.65) | 1.1 (0.96, 1.28) | 1.2 (0.92, 1.64) |

| Disabled for work | 1.6 (1.31, 1.87) | 1.3 (1.03, 1.53) | 1.9 (1.45, 2.47) | 1.4 (1.19, 1.60) | 1.7 (1.06, 2.75) |

| Unemployed | 1.1 (0.95, 1.30) | 1.1 (0.93, 1.24) | 1.2 (0.90, 1.58) | 1.2 (1.02, 1.32) | 1.0 (0.68, 1.42) |

| Other | 1.3 (1.07, 1.48) | 1.2 (1.08, 1.43) | 1.4 (1.03, 1.78) | 1.0 (0.88, 1.18) | 1.9 (1.42, 2.48) |

| Self-rated health | |||||

| Excellent (Ref) | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Very good | 1.1 (0.89, 1.26) | 1.1 (0.80, 1.41) | 1.1 (0.83, 1.39) | 1.1 (0.92, 1.24) | 1.1 (0.73, 1.53) |

| Good | 1.2 (1.01, 1.42) | 1.1 (0.82, 1.44) | 1.4 (1.05, 1.74) | 1.2 (1.04, 1.40) | 1.1 (0.76, 1.61) |

| Fair/poor | 1.1 (0.91, 1.34) | 1.2 (0.89, 1.58) | 1.1 (0.81, 1.49) | 1.0 (0.88, 1.20) | 1.3 (0.88, 2.00) |

| Major depressive episode | |||||

| Yes | 1.5 (1.32, 1.69) | 1.1 (0.99, 1.19) | 1.9 (1.58, 2.36) | 1.5 (1.35, 1.73) | 1.3 (1.03, 1.72) |

| No (Ref) | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Emergency room visits for treatment in the past year | |||||

| None (Ref) | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| 1 | 1.4 (1.20, 1.59) | 1.1 (0.97, 1.29) | 1.6 (1.29, 1.92) | 1.4 (1.21, 1.59) | 1.4 (1.04, 1.81) |

| 2 | 1.2 (1.06, 1.41) | 1.1 (0.96, 1.29) | 1.3 (1.02, 1.61) | 1.3 (1.08, 1.47) | 1.2 (0.89, 1.51) |

| ≥ 3 | 1.4 (1.19, 1.60) | 1.2 (1.04, 1.41) | 1.4 (1.13, 1.83) | 1.3 (1.13, 1.49) | 1.5 (1.10, 1.94) |

| Received past-year substance use treatment | |||||

| Yes | 1.4 (1.23, 1.50) | 1.2 (1.08, 1.36) | 1.4 (1.17, 1.75) | 1.2 (1.03, 1.29) | 2.0 (1.58, 2.53) |

| No (Ref) | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Received medical attention as a result of suicide attempt | |||||

| Yes | 1.4 (1.26, 1.61) | 1.5 (1.34, 1.70) | 1.3 (1.06, 1.60) | 1.4 (1.25, 1.56) | 1.3 (1.05, 1.63) |

| No (Ref) | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Perceived unmet need for mental health treatment | |||||

| Yes | 1.3 (1.17, 1.49) | 1.4 (1.25, 1.56) | 1.3 (1.05, 1.63) | ||

| No | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

Note. CI = confidence interval; MARR = model-adjusted risk ratio.

Among adults who attempted suicide and perceived unmet treatment needs in the past year, those with and without MDEs had similar mental health treatment rates (model-adjusted prevalence [treatment rates]: 76.3% among those with MDEs; 70.5% among those without MDEs). However, among adults who attempted suicide but who did not perceive unmet treatment needs in the past year, those with MDEs were 93% more likely to receive mental health treatment than those without MDEs (MARR = 1.93; 95% confidence interval [CI] = 1.58, 2.36; model-adjusted treatment rates: 64.2% among those with MDEs; 33.2% among those without MDEs). The MDE effect on receipt of mental health treatment was significantly greater among those who did not perceive unmet treatment needs than among those who perceived unmet treatment needs (P < .001).

Among adults who attempted suicide and received medical attention resulting from a suicide attempt in the past year, those who perceived unmet treatment needs were 40% more likely to receive mental health treatment than those who did not perceive unmet needs (MARR = 1.40; 95% CI = 1.25, 1.56; model-adjusted treatment rates: 85.3% for those with perceived unmet treatment needs; 61.0% for those without unmet needs). Among adults who attempted suicide but who did not receive medical attention resulting from a suicide attempt in the past year, those who perceived unmet treatment needs were 31% more likely to receive mental health treatment than those who did not perceive unmet needs (MARR = 1.31; 95% CI = 1.05, 1.63; model-adjusted treatment rates: 46.1% for those with perceived unmet treatment needs; 35.3% for those without unmet needs). The effect of perceived unmet treatment need on receipt of mental health treatment was significantly greater among those who received medical attention resulting from a suicide attempt than among those who did not receive medical attention (P = .007).

Among adults who attempted suicide and received medical attention resulting from a suicide attempt in the past year, those with MDEs were 53% more likely to receive mental health treatment than those without MDEs (MARR = 1.53; 95% CI = 1.35, 1.73; model-adjusted treatment rates: 84.4% among those with MDEs; 55.2% among those without MDEs). Among adults who attempted suicide but who did not receive medical attention resulting from a suicide attempt in the past year, those with MDEs were 33% more likely to receive mental health treatment than those without MDEs (MARR = 1.33; 95% CI = 1.03, 1.72; model-adjusted treatment rates: 45.3% among those with MDEs; 34.0% among those without MDEs). The MDE effect on receipt of mental health treatment was significantly greater among those who received medical attention resulting from a suicide attempt than among those who did not receive medical attention (P = .002).

Among adults who attempted suicide and perceived unmet treatment need in the past year, non-Hispanic Blacks and Hispanics were less likely to receive mental health treatment than non-Hispanic Whites (MARRs = 0.8, 0.9). Among adult suicide attempters who did not perceive unmet treatment need, non-Hispanic Blacks were less likely to receive mental health treatment than non-Hispanic Whites (MARR = 0.6; 95% CI = 0.44, 0.73). Among adults who attempted suicide and received medical attention resulting from a suicide attempt, non-Hispanic Blacks were less likely to receive mental health treatment than non-Hispanic Whites (MARR = 0.8; 95% CI = 0.73, 0.90). Among adult suicide attempters who did not receive medical attention resulting from a suicide attempt, Hispanics and non-Hispanic Blacks were less likely to receive mental health treatment than non-Hispanic Whites (MARRs = 0.5, 0.7).

These factors were not associated with receipt of mental health treatment among suicide attempters based on the results of the multivariable analyses.

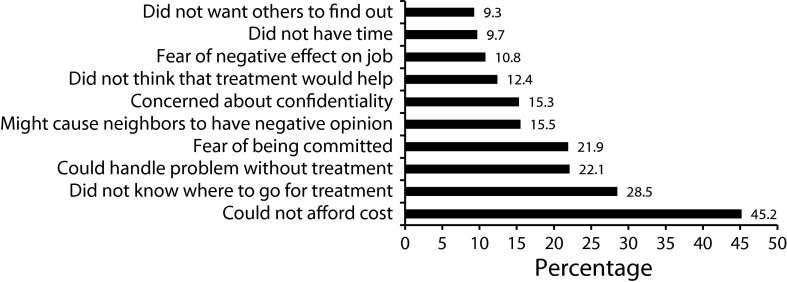

Figure 1 presents the reported reasons for not receiving mental health treatment in the past year among past-year adult suicide attempters who perceived unmet need for mental health treatment, including an inability to afford treatment (45.2%), not knowing where to go for treatment (28.5%), being able to handle mental health problems without treatment (22.1%), and having fear of being committed to treatment (21.9%).

FIGURE 1—

Self-reported reasons for not receiving mental health treatment in the past 12 months by adult suicide attempters who had an unmet need for mental health treatment: National Survey on Drug Use and Health, United States, 2008–2012.

Note. Adults (109 000; annual average) aged 18 years or older who attempted suicide in the past year and did not receive mental health treatment but perceived unmet treatment need in the past 12 months.

DISCUSSION

We showed that many adults who recently attempted suicide are not receiving mental health treatment. Only 56% of past 12-month suicide attempters received mental health treatment at some point during the past year. Approximately 41% received outpatient mental health treatment, and 15.8% had 1 to 4 outpatient mental health visits in the past 12 months. Approximately 29% received inpatient mental health treatment, and 8.4% stayed 1 to 3 nights for inpatient treatment in the past 12 months.

Furthermore, approximately half of past-year suicide attempters who received mental health treatment perceived unmet treatment needs, indicating that they might have received insufficient care. This result suggests a need for more follow-up and continuity of suicide-specific mental health treatment (e.g., dialectic behavior therapy, cognitive therapy, or integrated approaches).29–32 A significant reduction in death by suicide was found in Taiwan after that country implemented a nationwide aftercare program for suicide attempters.33

The low rate of perceived need for mental health treatment might contribute to the low mental health treatment rate among suicide attempters. More than one third of past 12-month suicide attempters neither received mental health treatment nor perceived unmet treatment needs. This is a major issue because these adults did not view their suicide attempt as a warning sign that they needed mental health treatment. Efforts are needed to promote effective public awareness programs (including at workplaces) and gatekeeper training to identify adults with high suicide risk34 and to facilitate the integration of mental health treatment into a range of settings, including the criminal justice system and ERs. It is critical to help suicide attempters understand that effective mental health treatment is available.3,6–8

We identified factors associated with receipt of mental health treatment that depended on perceived unmet treatment needs and receipt of medical attention resulting from a suicide attempt. Our results revealed specific groups of suicide attempters with low rates of mental health treatment who might particularly benefit from effective outreach efforts that promote treatment seeking. These groups included suicide attempters who neither had an MDE nor perceived unmet treatment need, suicide attempters who neither had an MDE nor received medical attention resulting from a suicide attempt, and suicide attempters who neither received medical attention resulting from a suicide attempt nor perceived unmet treatment need.

Understanding racial/ethnic disparities in suicide attempt is critical because sociocultural norms can either facilitate or inhibit suicide and suicide attempts.35,36 We found low mental health treatment rates for Hispanics and non-Hispanic Blacks. For example, among past 12-month suicide attempters who did not perceive unmet treatment need, non-Hispanic Blacks were less likely to receive mental health treatment in the past year than non-Hispanic Whites. Among suicide attempters who did not receive medical attention resulting from a suicide attempt, Hispanics and non-Hispanic Blacks were less likely to receive mental health treatment in the past year than non-Hispanic Whites. Culturally and linguistically appropriate public awareness programs and outreach efforts that effectively promote seeking help are needed to target these minority suicide attempters.

Study Limitations

Our study had several limitations. We could not examine the onset time, number, severity, and methods of suicide attempts, severity of physical conditions, and the timing of the receipt of mental health treatment because the 2008 to 2012 NSDUH did not collect these data. It was impossible to determine whether suicide attempts occurred before or after mental health treatment was received. Finally, NSDUH is a self-report survey and is subject to recall bias.

Conclusions

Despite these limitations, our study might be useful for mental health parity and health care reform efforts. The Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act requires insurance groups offering coverage for mental health or SUDs to provide the same level of benefits that they do for medical treatment. Some uninsured suicide attempters might be eligible for Medicaid or private insurance enrollment under the Affordable Care Act’s Medicaid expansion and insurance exchange programs. We found that among past-year suicide attempters who received medical attention resulting from a suicide attempt, 32% did not receive mental health treatment in the past year despite their high risk for reattempt and death by suicide. Among suicide attempters who did not receive mental health treatment but who perceived an unmet treatment need, almost half felt they could not afford the costs, and almost 30% of them did not know where to go for treatment. Our findings were consistent with results from previous studies on barriers to mental health treatment reported by suicidal hotline callers in the United States37 and on low acceptance rates for all health insurance types by psychiatrists compared with physicians in other specialties.38 Research is needed to assess the impact of the Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act and the Affordable Care Act on changes in mental health treatment rates and intensity among suicide attempters. As emphasized in the 2012 National Strategy for Suicide Prevention,3 it is crucial to promote follow-up and continuity of mental health treatment among suicide attempters and increase their access to high-quality mental health treatment.

Human Participant Protection

The data collection protocol of the National Survey on Drug Use and Health was approved by the institutional review board at RTI International.

References

- 1.The Centers of Disease Control and Prevention. Understanding Suicide. Fact Sheet. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/ViolencePrevention/pub/Suicide_factsheet.html. Accessed on January 1, 2013.

- 2.Crosby AE, Han B, Ortega LA, Parks SE, Gfroerer J. Suicidal thoughts and behaviors among adults aged ≥18 years–United States, 2008-2009. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2011;60(13):1–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.US Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) Office of the Surgeon General and National Action Alliance for Suicide Prevention. The 2012 National Strategy for Suicide Prevention: Goals and Objectives for Action. Available at: http://www.surgeongeneral.gov/library/reports/national-strategy-suicide-prevention/full-report.pdf. Accessed October 15, 2013. [PubMed]

- 4.Suominen K, Isometsa E, Suokas J, Haukka J, Achte K, Lonnqvist J. Completed suicide after a suicide attempt: a 37-year follow-up study. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161(3):562–563. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.3.562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Results From the 2012 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Mental Health Findings. NSDUH Series H-47; HHS Publication No. SMA 13-4805. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 6.American Psychiatric Association. Practice Guideline for the Assessment and Treatment of Suicidal Behaviors. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bruce ML, Have TRT, Reynolds CF et al. Reducing suicidal ideation and depressive symptoms in depressed older primary care patients. JAMA. 2004;291(9):1081–1091. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.9.1081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.While D, Bickley H, Roscoe A et al. Implementation of mental health service recommendations in England and Wales and suicide rates, 1997–2006: a cross-sectional and before-and-after observational study. Lancet. 2012;379(9820):1005–1012. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61712-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kessler RC, Berglund P, Borges G, Nock M, Wang PS. Trends in suicide ideation, plans, gestures, and attempts in the United States, 1990-1992 to 2002-2003. JAMA. 2005;293(20):2487–2495. doi: 10.1001/jama.293.20.2487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality. The NSDUH Report: Utilization of Mental Health Services by Adults with Suicidal Thoughts and Behavior. 2011. Available at: http://www.samhsa.gov/data/2k11/WEB_SR_014/WEB_SR_014.htm. Accessed October 30, 2013.

- 11.Pagura J, Fotti S, Katz LY, Sareen J. Help seeking and perceived need for mental health care among individuals in Canada with suicidal behaviors. Psychiatr Serv. 2009;60(7):943–949. doi: 10.1176/ps.2009.60.7.943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wu P, Katic BJ, Liu X, Fan B, Fuller CJ. Mental health service use among suicidal adolescents: findings from a US national community survey. Psychiatr Serv. 2010;61(1):17–24. doi: 10.1176/ps.2010.61.1.17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ahmedani BK, Perron B, Ilgen M, Abdon A, Vaughn M, Epperson M. Suicide thoughts and attempts and psychiatric treatment utilization: informing prevention strategies. Psychiatr Serv. 2012;63(2):186–189. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201100159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yoon J, Bernel SL. The role of adverse physical health events on the utilization of mental health services. Health Serv Res. 2013;48(1):175–194. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2012.01442.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nock MK, Hwang I, Sampson NA, Kessler RC. Mental disorders, comorbidity and suicidal behavior: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Mol Psychiatry. 2010;15(8):868–876. doi: 10.1038/mp.2009.29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dougherty DM, Mathias CW, Marsh DM, Moeller FG, Swann AC. Suicidal behaviors and drug abuse: impulsivity and its assessment. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2004;76(suppl):S93–105. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2004.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cook TB. Recent criminal offending and suicide attempts: a national sample. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2013;48(5):767–774. doi: 10.1007/s00127-012-0567-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhang J, Yu KF. What’s the relative risk? A method of correcting the odds ratio in cohort studies of common outcomes. JAMA. 1998;280(19):1690–1691. doi: 10.1001/jama.280.19.1690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McNutt LA, Wu C, Xue X, Hafner JP. Estimating the relative risk in cohort studies and clinical trials of common outcomes. Am J Epidemiol. 2003;157(10):940–943. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwg074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Greenland S. Model-based estimation of relative risks and other epidemiologic measures in studies of common outcomes and in case-control studies. Am J Epidemiol. 2004;160(4):301–305. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwh221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bieler GS, Brown GG, Williams RL, Brogan DL. Estimating model-adjusted risks, risk differences, and risk ratio from complex survey data. Am J Epidemiol. 2010;171(5):618–623. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwp440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. National Survey on Drug Use and Health. Available at: http://www.oas.samhsa.gov/nsduh.htm. Accessed August 1, 2013.

- 23.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Results From the 2012 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Summary of National Findings. NSDUH Series H-46; HHS Publication No. SMA 13-4795. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 24.American Psychiatry Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 4th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatry Association; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Grucza RA, Abbacchi AM, Przybeck TR et al. Discrepancies in estimates of prevalence and correlates of substance use and disorders between two national surveys. Addiction. 2007;102(4):623–629. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2007.01745.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jordan BK, Karg R, Batts KR et al. A clinical validation of the National Survey on Drug Use and Health assessment of substance use disorders. Addict Behav. 2008;33(6):782–798. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2007.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Reliability of Key Measures in the National Survey on Drug Use and Health. Office of Applied Studies, Methodology Series M-8, HHS Publication No. SMA 09-4425. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2010. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shah B, Barnwell B, Bieler G. SUDAAN User’s Manual. Version 9.1. Research Triangle Park, NC: Research Triangle Institute; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Valenstein M, Eisenberg D, McCarthy JF et al. Service implications of providing intensive monitoring during high-risk periods for suicide among VA patients with depression. Psychiatr Serv. 2009;60(4):439–444. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.60.4.439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Linehan MM, Armstrong HE, Suarez A, Allmon DJ, Heard HL. Cognitive-behavioral treatment of chronically parasuicidal borderline patients. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1991;48(12):1060–1064. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1991.01810360024003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stanley B, Brown G, Brent DA et al. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for suicide prevention (CBT-SP): treatment model, feasibility, and acceptability. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2009;48(10):1005–1013. doi: 10.1097/CHI.0b013e3181b5dbfe. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Knox KL, Litts DA, Talcott GW, Catalano-Feig J, Caine ED. Risk of suicide and related adverse outcomes after exposure to a suicide prevention program in the US Air Force: cohort study. BMJ. 2003;327(7428):1376–1380. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7428.1376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pan YJ, Chang WH, Lee MB, Chen CH, Liao SC, Caine ED. Effectiveness of a nationwide aftercare program for suicide attempters. Psychol Med. 2013;43(7):1447–1454. doi: 10.1017/S0033291712002425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Han B, McKeon R, Gfroerer J. Suicide ideation among community-dwelling adults in the United States. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(3):488–497. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Range LM, Leach MM, McIntyre D et al. Multicultural perspectives on suicide. Aggress Violent Behav. 1999;4(4):413–430. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Orbach I. A taxonomy of factors related to suicidal behavior. Clin Psychol Sci Pract. 1997;4(3):208–224. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gould MS, Munfakh JL, Kleinman M, Lake AM. National suicide prevention lifeline: enhancing mental health care for suicidal individuals and other people in crisis. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2012;42(1):22–35. doi: 10.1111/j.1943-278X.2011.00068.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bishop TF, Press MJ, Keyhani S, Pincus HA. Acceptance of insurance by psychiatrists and the implications for access to mental health care. JAMA Psychiatry. 2014;71(2):176–181. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.2862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]