Abstract

We systematically reviewed peer-reviewed and gray literature on comprehensive adolescent health (CAH) programs (1998–2013), including sexual and reproductive health services. We screened 36 119 records and extracted articles using predefined criteria. We synthesized data into descriptive characteristics and assessed quality by evidence level.

We extracted data on 46 programs, of which 19 were defined as comprehensive. Ten met all inclusion criteria. Most were US based; others were implemented in Egypt, Ethiopia, and Mexico. Three programs displayed rigorous evidence; 5 had strong and 2 had modest evidence. Those with rigorous or strong evidence directly or indirectly influenced adolescent sexual and reproductive health.

The long-term impact of many CAH programs cannot be proven because of insufficient evaluations. Evaluation approaches that take into account the complex operating conditions of many programs are needed to better understand mechanisms behind program effects.

Global evaluation research has repeatedly shown that the evidence for and effectiveness of many adolescent pregnancy prevention programs is unclear.1,2 Kirby et al.2,3 found that numerous pregnancy prevention programs had little effect; however, among programs that were most successful, the majority used comprehensive approaches that combined activities related to health, education, and social supports. Both in the United States and globally, interest has turned to such comprehensive (sometimes also referred to as multilevel or multicomponent) strategies for improving the sexual and reproductive health (SRH) of adolescents, in addition to overall health and developmental outcomes. In the United States, the Obama administration has identified the Harlem Children’s Zone as a prototype for its Promise Neighborhoods that aim to improve child and adolescent education and development in disadvantaged neighborhoods.4 Internationally, the United Nations Population Fund and other organizations have worked together to scale up a comprehensive model for preventing early marriage and reducing adolescent fertility in 12 countries.5

Comprehensive approaches move beyond sexuality education curriculums, contraceptive distribution programs, and abstinence-only programs to build a package of services and programs that target the root causes of sexual health risk and early pregnancy. Such strategies are based on an understanding of health and development in which adolescents are nested in a network of contexts (peers, community, health services, schools, families), suggesting that comprehensive approaches hold the greatest promise. However, little is known about the range, scope, or common activities of such programs and whether such strategies can successfully improve adolescent SRH.

In this article, we explore what is known about the elements of and evidence base for comprehensive adolescent health programs that encompass SRH and other health services, educational services, and social support services. The objectives of the systematic review were to (1) describe the characteristics of evaluated comprehensive adolescent health programs, as defined in this article, (2) provide an assessment of the quality of and evidence for comprehensive adolescent health programs, and (3) identify the common elements of the strongest evaluated comprehensive adolescent health programs that show successful outcomes.

METHODS

Methods for screening, inclusion, and analysis for this article were specified in advance and documented in a protocol (available on request) based on the World Health Organization’s systematic review practices.6 We conceptualized the review and carried it out in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses statement.7

Criteria for Considering Studies for This Review

We reviewed peer-reviewed and gray literatures published between January 1998 and April 2013. We included peer-reviewed articles without language restriction, whereas we restricted the gray literature to English, Spanish, and French.

Types of participants.

The majority of program participants (80%) had to be male or female adolescents aged 10 to 19 years; however, we also considered programs targeting youths to age 24 years. Programs had to have at least 100 participants.

Types of programs.

Studies included in this review had to refer to comprehensive adolescent health programs. For the purpose of this review, we defined comprehensive programs as interventions that provide the following:

Health services: SRH services and at least 1 of the following: primary medical care, mental health care, substance use counseling, or services for physical or sexual abuse. Because early pregnancy within or outside of marriage forecloses opportunities for many adolescents, delaying pregnancy and first births is central in helping young women and men achieve their potential.1 Consequently, for the purpose of this review, comprehensive adolescent health programs needed to include SRH as part of the health services package offered.

Educational support: matriculation, retention and school completion supports, after-school programs, or services targeting out-of-school adolescents. Much as delaying marriage and early childbearing, educational achievement is critical to the health and well-being of adolescents worldwide1,5,8,9; thus, activities to enhance school retention and academic success are another central component of comprehensive programming.

Social support: Comprehensive approaches must move beyond health and education to address the social contexts and environments in which an adolescent resides. Social support mechanisms and social skill development have been found to be critical for positive adolescent and youth outcomes.10 To meet our definition of comprehensive, programs therefore had to include 1 or more of the following: social or vocational supports, family or parent engagement, life skills training, and family life or sexuality education.

In addition, we included programs only if they had documented effects through outcome or impact evaluations. Such evaluations had to have been conducted using a randomized experimental, quasi-experimental, or pre- and postoutcome measurement design with a minimum sample size of 100. For the purpose of this review, we included several studies that corresponded to the same program.

Outcome measures.

The primary outcome of interest was SRH from a broad definition, including adolescent pregnancy, contraceptive use, sexually transmitted infections, romantic relationship engagement and quality, sexual negotiation, and gender norms. Secondary outcomes included educational (school enrollment, retention, graduation rates, academic grades, college enrollment) and other health-related outcomes (mental health, social and emotional supports and networks, life skills, employment, housing).

Information Sources and Search Strategy

We used the following electronic databases: PubMed, Global Health, ERIC, Scopus, PsycINFO, MEDLINE, EMBASE, CAB, BIOSIS, POPLINE, Latin American and Caribbean Health Sciences Information, and the Pan-American Health Organization library catalog. We also searched World Health Organization online databases: Index Medicus for the World Health Organization Eastern Mediterranean Region and the African Index Medicus (Table 1 lists search terms).

TABLE 1—

Core Database Search Strategy: Peer-Reviewed and Gray Literature, January 1998–April 2013

| Focus | Search terms |

| (1) Population: adolescents | (((“Adolescent”[Mesh] OR “Adolescent Development”[Mesh] OR “Homeless Youth”[Mesh] OR “Child, Abandoned”[Mesh] OR children*[tiab] OR adolescen*[tiab] OR teen*[tiab] OR youth*[tiab] OR young adult*[tiab] OR Young women[tiab] OR young woman[tiab] OR young man[tiab] OR young men[tiab] OR Young adult[mesh]))) |

| AND | |

| (2) Comprehensive program | ((comprehensive[tiab] OR integrated[tiab] OR multi level[tiab] OR multi faceted[tiab] OR multi component[tiab] OR multilevel[tiab] OR multifaceted[tiab] OR multicomponent[tiab] OR multidimensional[tiab] OR multidimensional [tiab] OR holistic[tiab] OR holistic health[mesh]) OR “Community Networks”[Mesh] OR youth development program*[tiab] OR youth program*[tiab] OR teen program*[tiab] OR adolescent program*[tiab] OR “opportunity programme”[tiab])) |

| AND | |

| (3) Health services | (adolescent health services[mesh] OR school health services[mesh] OR reproductive health services[mesh] OR Family planning services[mesh] OR Health promotion[mesh] OR (Health[tiab] AND (care[tiab] OR program*[tiab] OR planning[tiab] OR service*[tiab])) OR Teen pregnancy[tiab])) AND (“Intervention Studies”[Mesh] OR “Programme Evaluation”[Mesh] OR “Programme Development”[Mesh] OR follow-up studies [mesh] OR (epidemiologic*[tiab]) |

| AND | |

| (4) Evaluation of some kind | (study[tiab] OR studies[tiab])) OR (intervention*[tiab] AND (study[tiab] OR studies[tiab] OR program*[tiab] OR pilot[tiab]) OR evaluat*[tiab] OR causal effect[tiab])) |

For the gray literature, we screened Web pages from major organizations working in adolescent health (list available on request) and relevant in-country government Web sites. We also used Google to search for additional information to determine program eligibility, which was not provided on organization Web sites. In cases in which program data were not available online, we attempted to communicate with study authors or program staff.

Data Collection and Analysis

We screened titles and abstracts for peer-reviewed and gray literature using an 11-item form for which a negative response to any item resulted in exclusion; all reasons for exclusion were recorded. We obtained full-text documents for all titles that passed the initial screen. Review of full-text records resulted in exclusion of additional studies for failure to meet comprehensive criteria. We then subjected all retained articles to a 56-item instrument used to extract information on (1) general study characteristics such as design, setting, and population; (2) type of adolescent health program, outcome measures, and results; and (3) evaluation design and quality.

Two of us (A. K. and J. P.) screened each title and abstract. Rating inconsistencies or disagreements were resolved through consultation with R. W. B., A. K., and J. P. extracted data from all included studies, and S. T. assisted by contacting programs for additional information when needed.

Before initiating the search process, all instruments were piloted on a random selection of 50 references encompassing the entire time period (1998–2013) to assess interobserver reliability and identify gaps in screening and data extraction forms.

Assessment of risk of bias in individual studies.

We evaluated each included study for methodological quality using the principles of Higgins et al.,11 including random selection of participants, random allocation of the intervention, blinding, attrition, intervention and control group crossover, sample size, duration of follow-up, and selective reporting.

Quality appraisal.

After data extraction, we assessed the evidence level of all programs using available evaluation data. We did not intend to conduct a formal outcome-level assessment of intervention effects and compare them in a meta-analysis because of the varied range of interventions and study designs. Rather, we conducted a quality assessment based on the extent to which the programs met the following criteria:

thorough description of all components,

use of conceptual framework or logic model,

replicated (copying the specific elements that made the program successful and applying them elsewhere),

scaled up (either to a wider geographical or institutional scale or integrated into regional or national policies),

detailed description of measures and outcomes,

significant impact on outcomes, and

published evaluation results in a peer-reviewed journal.

The program qualities were then categorized by evidence level: rigorous (experimental evaluation with random assignment of intervention and control groups), strong (quasi-experimental evaluation using pre–post, controlled assessment without randomization), and modest (pre–post assessment without randomization or control group).

Data synthesis.

We synthesized all extracted data into descriptive program characteristics and quality assessments. In addition, for programs with rigorous and strong evidence, we assessed the common elements (core activities that cut across several program models), challenges, and lessons learned. In this process, we synthesized data from several sources; we thus present results for individual programs (not studies).

Summary measures.

Because of the varied study designs and models, we were unable to use a common summary measure for program outcomes. We therefore chose not to present any numeric effect estimates such as odds ratios or differences in means in the Results section. Thus, when discussing program effects, we refer to whether programs showed a positive, a negative, or no impact on the desired outcomes.

RESULTS

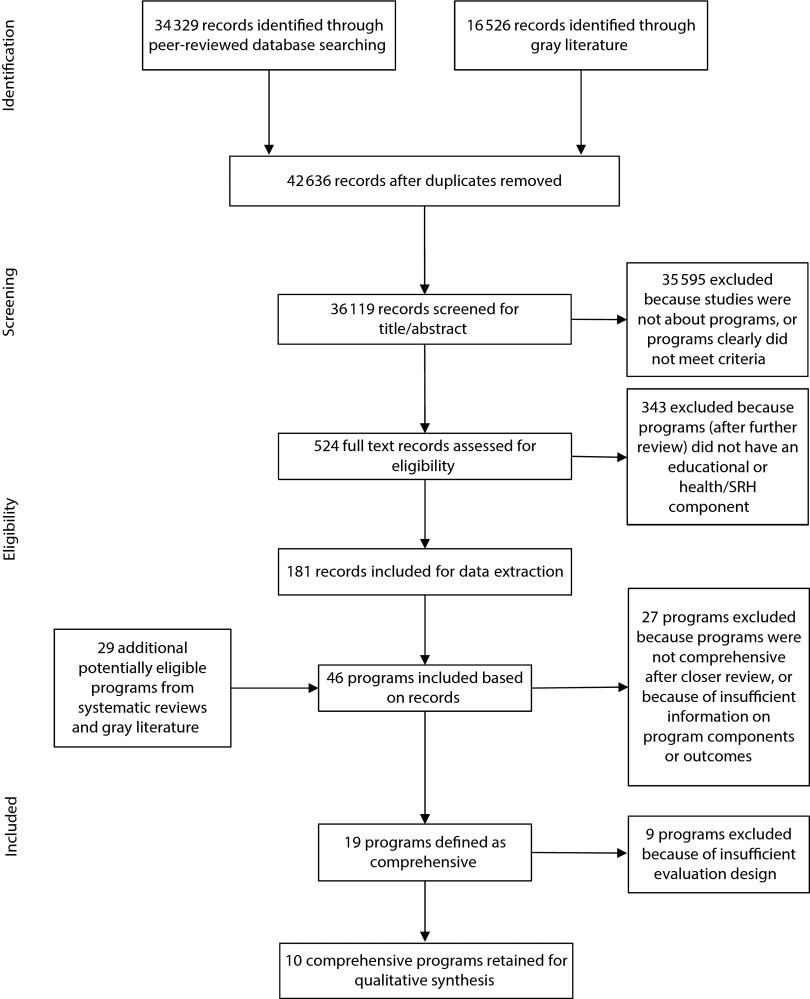

Figure 1 depicts the systematic review process of screening through data extraction and program inclusion. In total, we screened 36 119 records from both the peer-reviewed and the gray literature. We obtained full text for 524 titles, of which we retained 181 for data extraction. Studies on programs that did not have educational or SRH service components were excluded (n = 343) during the full-text review. The 181 retained articles corresponded to 46 programs for which we extracted data; however, we subsequently excluded 27 programs either because they did not meet the comprehensive criteria or because too much information was missing on program components or outcomes. In addition, we excluded 9 programs that met the criteria because of insufficient evaluation, which typically provided for a pretest-only design. These 9 programs are all listed in Appendix A (available as a supplement to this article at http://www.ajph.org). Ultimately, 10 comprehensive adolescent health programs met all the inclusion criteria for this review.

FIGURE 1—

PRISMA 2009 Flow Diagram of search and data extraction.

Note. SRH = sexual and reproductive health.

Source. Liberati et al.7

Program Characteristics

Table 2 provides a brief overview of the characteristics of the 10 included programs (Appendix B, available as a supplement to this article at http://www.ajph.org, for additional detail). The earliest program started in 1984; the most recent was initiated in 2006. Five programs were still active as of November 2013. Most (n = 6) were located in the United States; 4 others were identified in Egypt (n = 1), Ethiopia (n = 2), and Mexico (n = 1).

TABLE 2—

Summary of Characteristics of Included Comprehensive Adolescent Health Programs: Peer-Reviewed and Gray Literature; January 1998–April 2013

| Program Activities (Type, Format, and Duration) |

|||||||||||

| Program Name | Implementing Organization | Funder | Start–End | Goal or Objective | Location | Target Population | Size | Health Services Inclusive of SRH | Education | Other | Evaluation Type and Significant Results |

| Programs Based in the United States | |||||||||||

| Adolescent Sibling Pregnancy Prevention Program12 | California Department of Health Services, Maternal and Child Health Branch | 1996–2006 | To reduce rates of adolescent pregnancy among siblings of pregnant or parenting adolescents, given the high rates of pregnancy in this population | California | Brothers and sisters of pregnant and parenting adolescents, aged 11–17 y (who participated in California’s Cal-Learn or Adolescent Family Life program) | ∼2000 adolescents served yearly across 18 counties | Provision of health services in line with individual needs, including family planning and abstinence counseling, access to quality reproductive health care, transportation to health facilities, incentives to avoid sexual risk taking | Academic guidance, tutoring, and assistance with library research | Education about media messages on body image and sexual behavior | Pre–post assessment with control group12 indicated reduced likelihood of pregnancy among participating adolescent girls and increased consistent condom use among boys. | |

| Assistance in getting medical insurance | Advocacy at expulsion and court hearings | The program also decreased the likelihood of truancy and gang participation among program adolescents. | |||||||||

| Field trips and group activities to improve social skills and social competency | |||||||||||

| Sports activities | |||||||||||

| Children’s Aid Society–Carrera pregnancy prevention program13–15 | Children’s Aid Society | 1984–ongoing | To help adolescents develop personal goals and the desire for a productive future, in addition to developing their sexual literacy and educating them about the consequences of sexual activity | Started in New York City, NY; now expanded to partnership sites in 13 additional states | At-risk male and female adolescents in Harlem | ∼4000 young men and women | Reproductive health care, including physical exams, testing, and contraceptive counseling; specialty care as needed | Daily academic assistance such as tutoring, homework assistance, and preparation for tests and college applications | Weekly job club | Randomized controlled trial14 showed that the intervention successfully prevented pregnancy and increased contraception use among girls (no difference among boys). Sexual knowledge increased for both genders. | |

| Annual medical and semiannual dental check-up | Weekly family life and sexuality education | The intervention also had positive impacts on other health outcomes, employment, and social networks. | |||||||||

| Daily access to counseling and personal crisis support as well as weekly discussion groups | Music, dance, drama, and individual sports | ||||||||||

| Community organizer who keeps track of all adolescents | |||||||||||

| Kansas school/community model for preventing adolescent pregnancy16 | Kansas School/Community Sexual Risk Reduction Replication Initiative; Geary County School District and community organizations in Franklin and Wichita counties, Kansas | Kansas Health Foundation | 1993–1997 | To reduce adolescent pregnancies, to delay the age of first sexual intercourse, and increase contraceptive use among sexually active adolescents | Kansas | Primarily girls and boys aged 14–17 y, though sexuality education components were taught in K–12th grade | 65 000 contacts with K–12th-grade students | Increased access to contraceptives through school clinics, increased number of supermarkets carrying contraceptives, and installation of condom vending machines at gas stations and convenience stores | Mentoring and tutoring support by staff and volunteers. Specific components varied between counties. | Comprehensive, age-appropriate sexuality education from K to 12th grade | Pre–post assessment with control group showed increased condom use and decreased pregnancy rates in intervention areas (no change in control areas).16 |

| Sexuality education for teachers and parents | |||||||||||

| Family communication | |||||||||||

| Peer support groups | |||||||||||

| Alternative after-school and summer programs | |||||||||||

| Promoting Adolescents Through Health Services (PATHS)17 | Akron Children’s Hospital and its foundation | Ohio Department of Health; Akron Children’s Hospital Foundation | Started in 1990; unclear whether still ongoing | To provide at-risk adolescents and their families with the services, skills, and contexts needed for young people to make healthy choices | Ohio | Long-term program working specifically with socioeconomically disadvantaged adolescents beginning at age 12 y and continuing through high school graduation | > 140 adolescents completed the program | Health care and supportive counseling | Homework help and tutoring and assistance with college admission during weekdays | Family life and comprehensive sexuality education | Pre–post assessment using level of program participation as the independent variable indicated that positive change in educational, employment and criminal justice outcomes increased with participation.17 |

| Vocational training | |||||||||||

| Creative arts | |||||||||||

| All activities provided during weekdays | |||||||||||

| Prime Time18–22 | University of Minnesota Prevention Research Center | CDC’s Prevention Research Centers Program and NIH | 1999–2004; 2007–2008 | To provide clinic-based adolescent development interventions to reduce sexual risk behaviors among girls at high risk for early pregnancy | Minneapolis and St. Paul, MN | Girls aged 13–17 y with high-risk SRH behaviors, aggressive and delinquent behaviors, or school-disconnected behaviors | > 120 girls | Case management in addition to clinical services, including sexual and reproductive health care | Case management, including discussion and links to school support services | Peer leadership groups; monthly case manager meetings with girls to promote positive family and school involvement, skills to avoid sexual risk taking, and other individual needs | Randomized controlled trial showed that the intervention successfully increased contraceptive use in intervention areas after 1 y.21 |

| Program duration 18 mo | Service learning groups (12- to 17-wk courses), community service engagement | The program also had a positive impact on high school graduation and college enrollment at 24-mo follow-up.20 | |||||||||

| Peer education (12- to 23-wk training) in topics such as conflict resolution, sexual decision making, and healthy relationships | |||||||||||

| Caring Equation23 | Arlington County, Virginia, Public Schools | US Department of Health and Human Services | 2003–ongoing | To educate adolescent parents about child development, foster parenting skills, keep adolescent parents in school, encourage educational and vocational training, and provide interagency resources | Arlington County, VA | Aged 14–20 y, referred after drop out from school because of pregnancy | > 700 adolescent clients, their partners, or both | Pregnancy testing and maternity counseling | Educational and vocational training | Adoption counseling and referral services | Pre–post assessment without control group indicated positive changes in parental behaviors (e.g. fatherhood involvement) and parental attitudes (e.g. increased empathy) 6 mo after the intervention.23 |

| Primary and preventive health services (e.g. prenatal care) | Family life and sexuality education | ||||||||||

| Nutrition information and counseling | Child care or child care referral | ||||||||||

| Referral for family planning services, STI/HIV test and counseling | Transportation and outreach services for families | ||||||||||

| Mental health services | Financial, legal, and housing counseling | ||||||||||

| Domestic violence counseling | |||||||||||

| Programs based outside of the United States | |||||||||||

| Berhane Hewan9,24,25 | Population Council in collaboration with the Amhara Regional Bureau of Women, Children, and Youth | Nike Foundation, UN Foundation, UNFPA, USAID | 2004–ongoing | To establish appropriate and effective mechanisms to protect girls at risk for forced early marriage and support adolescent girls who are already married | Ethiopia (Amhara region) | Married and unmarried girls aged 10–19 y living in rural, poor areas | > 15 000 girls reached to date with activities | Supported costs for health service clinic cards | School retention incentives (e.g., materials and uniforms) for both in- and out-of-school girls | Biweekly girls’ clubs led by adult female mentor, with livelihood training for out-of-school girls | Quasi-experimental evaluation showed that the program successfully decreased the likelihood of early marriage and increased spousal communication about family planning.9 |

| Referred all participants in need for SRH services to special clinics | Out-of-school married and unmarried girls met weekly for informal literacy and other education | Community conversations about early marriage, girls’ schooling, etc., to identify problems and reach collective decisions | Results also showed that program girls were more likely to remain in school, make new friends, and have safe spaces to meet friends.9,24 | ||||||||

| Incentive (goat) promised to parents of girls who were not married before their graduation | |||||||||||

| Biruh Tesfa26,27 | Population Council in collaboration with the Ethiopian Ministry of Youth and Sport and the Amhara Regional Bureau of Youth and Sport | Nike Foundation, Turner Foundation, UN Foundation, UNFPA, USAID, PEPFAR | 2006–ongoing | To increase social networks and support networks for the poorest, most marginalized girls living in poor urban slum areas in Ethiopia and to increase the levels of HIV knowledge and experiences with VCT | Ethiopia (Addis Ababa) | Slum-dwelling, out-of-school adolescent girls (aged 10–19 y); e.g., rural–urban migrants | > 50 000 girls reached. Scaled up in 18 cities; 245 mentors in 92 meeting spaces | Annual wellness check-ups and basic health care screenings at local facilities. | Literacy and numeration education 3–5 times/wk | Girls’ groups 3–5 times/wk; 30-h life skills and HIV curriculum, and vocational support | Quasi-experimental evaluation showed that the program increased knowledge of HIV and where to get tested for HIV. |

| Basic medical care including SRH services free of charge through an arrangement with government health facilities | Help getting ID cards | Program girls were also more likely to have social support networks than peers in control areas.27 | |||||||||

| Shelter and support for victims of sexual violence. | |||||||||||

| Special program for disabled participants | |||||||||||

| Soap and sanitary napkins also provided | |||||||||||

| Ishraq28–30 | Caritas Egypt; Centre for Development and Population Activities; Population Council; Save the Children | 2001–ongoing | To educate girls in literacy and basic academic subjects, to help them understand more about their community and their rights, and to introduce them to the public sphere through safe spaces, sports, and recreational activities | Egypt (rural upper areas) | Out-of-school girls aged 13–15 y in rural upper Egypt and adolescent boys aged 13–17 y in the same areas | Directly reached > 3000 girls and > 1700 boys in 54 villages, and > 5000 parents and community leaders | Helped girls obtain ID and birth certificates, which in turn were used to get health insurance | Literacy and math courses twice a week | Village committees for community input and support | Quasi-experimental evaluation showed that the program increased family planning knowledge and successfully changed attitudes about early marriage (increased proportion desiring marriage after age 18 y) and family size (increased proportion desiring < 3 children).30 | |

| Representatives of youth clubs and schools suggested using an Ishraq-based health ID card recognized by providers at local health centers | Promotion of girls’ reentry into formal school system by age 18 y | Life skills curricula for boys and girls | Result also indicated impact on skills in math, reading, literacy, and the extent to which participants developed social networks.29 | ||||||||

| Physical activity or sports for 13 mo | |||||||||||

| Livelihood skills | |||||||||||

| Parental and community dialogues | |||||||||||

| Oportunidades (Progresa)31–36 | Mexican government | 1997–2005 | To break the cycle of poverty and to improve the education, health, nutrition, and living conditions of those in extreme poverty | Mexico (introduced in rural areas, now implemented throughout the country) | Family based, but evaluated specifically among those aged 15–24 y. Eligible families are included on the basis of poverty and need assessment scores. Families receive stipends for children aged 9–21 y. | > 5.8 million families | Health care service packages including clinical services for entire family | Conditional cash transfers provided for keeping children in school: (1) Educational grants provided from grades 3–12, conditional on at least 85% attendance and finishing a grade within 2 y, and (2) “youth with opportunities”; prospective career savings accounts for adolescents who finish high school | Conditional cash transfers provided given that participants attend rotating health promotion talks on adolescence and sexuality, family planning, and other topics | Randomized controlled trial showed short-term impacts on contraceptive knowledge and slight increase in contraceptive use among women aged 20–24 y.31 | |

| Nutrition supplement program; fixed monthly money transfer for improved food consumption | All cash transfers are provided on a monthly basis directly to the female head of the household | The program was also found to successfully affect school enrollment and educational attainment.31,36 | |||||||||

Note. CDC = Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; K = kindergarten; NIH = National Institutes of Health; PEPFAR = ; SRH = sexual and reproductive health; STI = sexually transmitted infection; UN = United Nations; UNFPA = United Nations Population Fund; USAID = US Agency for International Development; VCT = voluntary counseling and testing.

Size and target populations.

The size of the programs ranged from 100 to 10 000 participants, with 1 program (Oportunidades, Mexico) indicating an estimated reach by 1 or more activities of more than 100 000 adolescents.32,36 Age range varied, in that some programs included both younger and older adolescents (e.g., ages 10–19 years in Biruh Tesfa and Berhane Hewan, Ethiopia),9,27 and others targeted a narrower age range (e.g., high school students in Prime Time, Minneapolis and St. Paul, MN).19 Many programs were developed for specific populations: adolescents at high risk for delinquency (e.g. PATHS, Ohio),17 early pregnancy (e.g., Prime Time),19 or out-of-school migrant girls (e.g., Biruh Tesfa, Ethiopia).27 Adolescents growing up in poverty were also frequently targeted.13,29,31 Most programs were delivered to both male and female adolescents, but some (n = 3) focused only on girls, specifically in rural, poor areas.9,25–28 Two US-based programs (Adolescent Sibling Pregnancy Prevention Program [ASPPP] and the Caring Equation)12,23 were designed specifically for adolescent parents and their families. With the exception of Berhane Hewan,9,24 developed for married adolescent girls and those at risk for early marriage, all programs included unmarried adolescents.

Objectives.

Although many programs had similar goals, objectives varied from delaying age of marriage (Berhane Hewan)9 to breaking the cycle of poverty (Oportunidades).31 The most common objectives were adolescent pregnancy prevention and sexual risk reduction.12,14,16,19 Broader objectives to improve the overall health, well-being, and social support systems of adolescents were also common.

Activities.

Overall, programs used a wide range of activities and approaches. A common denominator was that many programs combined SRH services with in-school academic assistance or out-of-school educational supports, family life and sexuality education, and peer support and discussion groups. Some programs also included community mobilization, recreational activities, and vocational training. Duration and intensity of activities also varied substantially, from a couple of months to several years, though in many cases this was difficult to determine because of limited reporting on activity frequency or concurrence of services delivered. On the basis of available information, few programs offered both long-term and frequent activities. The Children’s Aid Society (CAS)–Carrera model is an exception, in which activities occurred daily (academic assistance, counseling), weekly (recreational activities, sexuality education), and annually (medical check-ups) throughout adolescence.13,14 By contrast, Oportunidades focused on long-term economic supports (conditional cash transfers for health services and schooling) rather than regular activities for adolescents,31,34,35 and Prime Time20 provided intensive case management activities over a shorter period (18 months).

Evaluation type and results.

Table 2 also presents the evaluation type used and corresponding results for each program. Three programs (CAS–Carrera, Oportunidades, and Prime Time) were rigorously evaluated using a randomized, experimental design; 5 others (ASPPP, Berhane Hewan, Biruh Tesfa, Kansas school/community model for preventing adolescent pregnancy, Ishraq) had a strong, quasi-experimental evaluation design; and 2 programs (PATHS and The Caring Equation) had modest evaluations using a pre–post assessment without a control or comparison group (see Appendix B for details on evaluation methods).

Programs with rigorous or strong evaluations were all found to have had direct or indirect effects on adolescent SRH. Although these effects are described in detail in Table 2, examples of direct effects include increased contraceptive use in 3 US-based programs (Prime Time among girls,18,20 CAS–Carrera among girls,14 and ASPPP among boys)12 and reduced likelihood of pregnancy among girls (CAS–Carrera, ASPPP).12,14 In Ethiopia, direct effects were seen through reduced likelihood of early marriage among girls (Berhane Hewan),9 and in Egypt, Ishraq was found to change adolescent attitudes about early marriage (increased proportion desiring to delay marriage until after age 18 years) and family size (increased proportion desiring fewer than 3 children).30 Oportunidades, however, appears to have had an indirect influence on adolescent fertility through increased schooling retention and graduation.32

Programs both in the United States and globally were found to improve school retention and graduation (CAS–Carrera, Prime Time, Berhane Hewan, Oportunidades).9,14,20,32 So, too, the Ishraq program, which specifically targets out-of-school adolescents, was found to improve math and literacy skills.29,30 In addition, results from Biruh Tesfa and Berhane Hewan in Ethiopia and Ishraq in Egypt showed that the programs improved adolescent girls’ peer social networks9,27,30; Biruh Tesfa and Berhane Hewan also improved girls’ access to safe spaces.9,27

For the 2 programs with a modest evaluation methodology (Caring Equation, PATHS),17,23 evaluation was restricted to only those who received the intervention; thus, the positive findings were difficult to ascribe specifically to the intervention.

Program Quality by Evidence Level

Table 3 presents an assessment of the extent to which each program met the quality criteria by the 3 different evidence levels. Of the 3 programs with rigorous evidence, 2 (CAS–Carrera and Oportunidades) met all quality assessment criteria, including a through description of program components, measures, and outcomes; use of a conceptual framework or logic model; replicated and scaled up; demonstrated significant positive outcomes; and published results in a peer-reviewed journal. Prime Time also met all criteria but had not been scaled up at a wider institutional level. Of the 5 programs with strong evidence, 2 (Berhane Hewan and Biruh Tesfa) met all quality criteria but 1 because whether a conceptual framework or logic model drove program activities was unclear.

TABLE 3—

Quality Assessment of Programs, by Evidence Level: Peer-Reviewed and Gray Literature; January 1998–April 2013

| Program | Describe All Components | Conceptual Framework | Replicateda | Scaled Upb | Describe Measures and Outcome | Significant Positive Impact | Peer-Reviewed Publication |

| Rigorous evidence: randomized controlled trial (experimental evaluation) | |||||||

| Children’s Aid Society–Carrera Pregnancy Prevention | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Oportunidades (Progresa) | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Prime Time | + | + | + | − | + | + | + |

| Strong evidence: pre–post, controlled assessment without randomization (quasi-experimental evaluation) | |||||||

| Berhane Hewan | + | ? | + | + | + | + | + |

| Biruh Tesfa | + | ? | + | + | + | + | + |

| Ishraq | + | ? | + | + | + | + | − |

| Adolescent Sibling Pregnancy Prevention Program | + | ? | ? | ? | + | + | + |

| Kansas adolescent pregnancy prevention school/community model | + | ? | + | − | + | + | + |

| Modest evidence: pre–post assessment without control group (nonexperimental evaluation) | |||||||

| Caring Equation | + | + | − | − | + | ? | + |

| Promoting Adolescents Through Health Services | ? | − | + | − | + | ? | + |

Replicated refers to copying the specific components that made the program successful and applying them elsewhere. Replication can occur in local, regional, national, or international settings.

Scaling up is broader than replication—it refers to when program components are rolled up at wider geographical or institutional scales or integrated in policies at regional or national levels.

Although programs displayed their results using clearly defined outcome measures, the definitions and variables used varied. For example, the measure of contraceptive use ranged from ever use in Berhane Hewan9 to consistency of use in Prime Time18,21 and ASPPP.12 Irrespective of their evidence level, most programs assessed short-term outcomes (< 5 years)37; those that were able to track the long-standing impact of activities (e.g., CAS–Carrera)14 were generally initiatives working with participants regularly throughout adolescence.

Finally, most programs with rigorous or strong evidence not only demonstrated a positive impact on intended outcomes but had been replicated in at least 1 additional setting, been scaled up to wider geographical or institutional levels, or both. For example, Berhane Hewan has expanded from a pilot project in a single kebele (village) to reaching more than 15 000 girls in 3 Ethiopian regions.9,38

Common Elements of Programs With Rigorous or Strong Evidence

Although programs used substantially different approaches and activities, we also identified a set of common elements of comprehensive programs with rigorous or strong evaluations and a positive impact on outcomes. These elements are summarized in the box on the next page. Overall, these programs share many commonalities, such as use of empirically based and developmentally appropriate services and interventions, active engagement of young people, and the provision of skills to ensure their success. Most centrally, they all reinforce the importance of building and sustaining long-term human relations and support systems.

Common Elements of Comprehensive Adolescent Health Program With Rigorous or Strong Evidence

| Health services inclusive of sexual and reproductive health |

| • Financial support (health insurance or clinic fees) |

| • Direct provision of sexual and reproductive health services (daily access to family planning, HIV/sexually transmitted infection counseling and testing, pregnancy test) |

| • Indirect provision of sexual and reproductive health services (daily access to referrals as needed) |

| • Basic medical care (annual medical and dental check-ups) |

| • Mental health (daily access to counseling, personal crisis support) |

| Educational support |

| • Academic assistance (daily or weekly tutoring, homework help, guidance, college test and admission preparation) |

| • Conditional cash transfers (for school enrollment and retention) |

| • Out of school (weekly informal literacy and math education, promotion of reentry into formal school system) |

| Social support |

| • Community dialogues or mobilization on program topics (early marriage, pregnancy prevention) |

| • Life skills and livelihood activities (weekly discussion groups) |

| • Vocational and livelihood training (weekly) |

| • Comprehensive sexuality education (for adolescents) |

| • Family, parent, and teacher support (sexuality education, discussion groups) |

| • Recreational activities (daily or weekly access to creative arts, sports, music) |

What also becomes evident is that effective programs include 1 or more elements relating to positive youth development,39,40 defined as participation in prosocial behaviors and avoidance of health and future compromising behaviors.39 The CAS–Carrera model, for example, built alternate support systems that parallel family structures for when parental supports are not available.13–15 Berhane Hewan established social networks for married and unmarried girls.9 In addition, all programs had distinct elements of adolescent participation and leadership. In Prime Time, adolescents were trained as both peer leaders and educators.18,22 Similarly, adolescent involvement through peer support groups was a key feature of improving social networks for the poorest and most marginalized girls targeted by Biruh Tesfa.26,27

Programs with rigorous or strong evidence also provided direct access to SRH services as well as daily or weekly academic assistance. This was especially evident in the CAS–Carrera model, which focused on surrounding adolescents with supports and services from daily tutoring and college preparation to personal crisis support and contraceptive counseling.15 Both Oportunidades and Berhane Hewan provided incentives to keep adolescents in school9,32; in the case of Ishraq, community members worked together to promote out-of-school girls’ reentry into the formal school system.30

An important note is that many programs strived to have an impact not only on their participants but also on the families and communities in which they reside (e.g., the Kansas school–community model for preventing adolescent pregnancy).16 Building community support appears to be both a common and a critical element of the most rigorously evaluated programs. The use of local women as program promoters was essential to negotiating girls’ participation in Ishraq,29,30 just as community conversations were key for Amharic villages in Berhane Hewan to reach collective decisions about resisting early marriage.9

DISCUSSION

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first systematic review of the landscape of comprehensive adolescent health programs inclusive of SRH services. Our results show that over the past 15 years, a wide range of self-identified comprehensive adolescent health programs have been implemented in countries around the world; however, few have been sustained over a long period and fewer still have been rigorously evaluated. One notable exception is the CAS–Carrera program, in which sustained supports and interventions were provided to participants over years and long-term impacts were concurrently measured using a randomized evaluation design. However, the number of programs excluded from this review because of a lack of evaluation, including control or comparison groups, is remarkable.

Clearly, as Kirby2 has noted, there are resource constraints. This becomes evident from the lack of geographic diversity among programs with rigorous or strong evidence, because most programs included in the review were based in the United States. Lee-Rife et al.41 suggested that the paucity of programs and complex evaluations in low- and middle-income countries likely reflects the infrastructure and economic disadvantage of resource-poor communities. Although this may in part be the case, there are examples of outstanding and well-researched programs from low- and middle-income countries that challenge this assumption (e.g., Berhane Hewan).9,24 More important, we recognize that alternatives to randomized controlled trials are necessary to fully understand the real-life conditions under which complex, comprehensive programs operate.41–43

When we look across the most effective and well-researched comprehensive adolescent health programs, we note that they differ substantially from each other in their approaches, activities, populations, objectives, and scope. Although this makes it challenging to directly compare results, it mirrors the diverse cultural, economic, social, and political contexts in which programs are being implemented.

In addition, despite the differences, we also saw a number of common elements that cut across comprehensive programs with rigorous or strong evidence (see the box on this page). It is beyond the scope of this review to say whether these are in fact the critical elements of effective programs, and further research is needed. Nonetheless, given the empirical base on which they were developed, it reasonable to believe that these elements represent good starting points for the development of comprehensive interventions.

We should note that disaggregating the relative impact of intervention elements remains a challenge in evaluating comprehensive programs.2,3,43–45 However, the claim of some programs that one cannot separate the elements without destroying the entire model is empirically unfounded. We are aware of 1 program (Berhane Hewan in Ethiopia) that is currently exploring the impact of each of its comprehensive components.38 The lessons that will be learned will advance cost-effective programming not just there but globally. Whether in high-income or low- and middle-income countries, resource constraints should favor evidence-based programs; so, too, however, should they favor rigorously evaluating each of the components of comprehensive programs to see whether a more parsimonious (and less expensive) model might yield similar results. That work remains to be done.

Also, much work remains in effective replication. The evidence has repeatedly suggested that replicating a high-quality program is indeed a complicated process that requires a balance of fidelity to the original and adaptation to the demands of the new context. The CAS–Carrera program, for example, does not appear to have had the same impact when replicated outside of New York City as it had in the original setting.2,3

Compounding this is the fact that many programs do not have publicly accessible documentation of activities; consequently, it is not possible to replicate them. In this review, we excluded numerous programs because of insufficient or unobtainable information. If we are to learn from the work that has come before, more complete program descriptions are needed in both peer-reviewed articles and the gray literature. Reporting key elements of the program’s context, target population, specifics of the intervention, and outcomes and how they are measured is crucial to better understand the impact of the programs as well as to guide the efforts for future replication and scale-up. Additionally, an idiosyncratic aura currently surrounds the concept of comprehensive—the term means whatever the program implementer desires. We would concur with Oringanje et al.44 that consistency of language and guidelines needs to be developed to allow international comparisons. Recognizing this gap, the World Health Organization will initiate a process to develop reporting standards for programs with a focus on maternal and SRH.

Limitations

First, although we used a thorough search strategy, we were invariably constrained by search terms; therefore, we may have inadvertently overlooked some programs. Second, we were limited by the information that was available through publications, the Web, and contact with program developers and evaluators. Although we made every attempt to be thorough, the fact that we were not able to find some materials does not mean that they do not exist. However, given the effort that we made to go back to the original program implementers and evaluators, if such material does exist, it is highly inaccessible.

Third, our search of the gray literature was limited to 3 languages and the Web sites of major international organizations. It is possible that program descriptions and evaluations may be available in other languages or on other Web sites. Because of the range of interventions and study designs, we did not conduct a meta-analysis of effect estimates. Because it was beyond the scope of this article to assess program effects, all results should be interpreted with caution.

Conclusions

The results of this review indicate that comprehensive adolescent health programs that combine high-quality sexual and reproductive and other health services with educational and social support mechanisms can positively influence adolescent SRH. Common elements such as long-term commitments to adolescents, building human connections, engaging key community stakeholders, and use of skill-building activities cut across all rigorously or strongly evaluated programs. However, more research is needed to better understand the mechanisms behind program effects because the wide range of approaches used by comprehensive programs makes it challenging to directly compare results. Additionally, the long-standing impact of many programs regrettably cannot be demonstrated because of insufficient evaluation designs. There is a need for both program developers and the scientific community to recognize and use evaluation approaches that take into account the complex conditions under which comprehensive programs operate. Finally, there is a need to identify key implementation factors that can aid in the scaling up of effective models.

Acknowledgments

This review was conducted with financial support from the UNDP/UNFPA/UNICEF/WHO/The World Bank Special Programme of Research, Development and Research Training in Human Reproduction, Department of Reproductive Health and Research, World Health Organization (WHO).

We thank Lale Say, MD, at the Department of Reproductive Health and Research at WHO for her continuous support during the review process and for providing valuable input. Special acknowledgment also to the contribution of Claire Twose and Peggy Gross, information specialists at the Welsh Medical Library, Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, who designed and implemented the search of peer-reviewed literature. Last but not least, we thank program staff and evaluators who took the time to provided additional information on programs: Enrica Bertoldo, Adolescent Family Life Programme Coordinator in California; Peggy B. Smith, PhD, director of Teen Health Clinics (Baylor Teen Clinic); Jeff Randall, MD, assistant professor, and Cynthia Cupit Swenson, PhD, professor (Neighborhood Solutions); Abigail van Straaten (Children’s Aid Society–Carrera); Julie Strand, development director (Chicago Youth Programs); Fleur Pollard at the International Planned Parenthood Foundation; Ishmael Selassie, Learning Center and youth coordinator at the Pediatric Pharmacy Advocacy Group Head Office; Katie Chau, Access, Services, and Knowledge Senegal national program coordinator (Young & Wise); and John Stevenson, PhD, program assessment coordinator and emeritus of psychology (Project HOPE).

Note. The findings in this article represent the conclusions of the authors and not necessarily those of the funders.

Human Participant Protection

This study did not involve human participants and therefore did not require institutional review board approval.

References

- 1.United Nations Population Fund Motherhood in Childhood: Facing the Challenge of Adolescent Pregnancy. State of World Population 2013 New York, NY: United Nations; Population Fund2013 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kirby D. Emerging Answers 2007: Research Findings on Programs to Reduce Teen Pregnancy and Sexually Transmitted Diseases. Washington, DC: National Campaign to Prevent Teen and Unplanned Pregnancy; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kirby D, Rhodes T, Campe S. The Implementation of Multi-Component Youth Programs to Prevent Teen Pregnancy Modeled after the Children’s Aid Society Carrera Program. Scotts Valley, CA: ETR Associates; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jean-Louis B, Farrow F, Schorr L, Bell J, Fernandes Smith K. Focusing on Results in Promise Neighborhoods: Recommendations for the Federal Initiative. New York, NY: Harlem Children’s Zone, Center for the Study of Social Policy; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 5.UNFPA’s Adolescent Girls Initiative: Programme Document. New York, NY: United Nations Population Fund; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Betrán AP, Say L, Gülmezoglu AM, Allen T, Hampson L. Effectiveness of different databases in identifying studies for systematic reviews: experience from the WHO systematic review of maternal morbidity and mortality. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2005;5(1):6. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-5-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate healthcare interventions: explanation and elaboration. BMJ. 2009;339:b2700. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b2700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Collins J, Robin L, Wooley S et al. Programs-that-work: CDC’s guide to effective programs that reduce health-risk behavior of youth. J Sch Health. 2002;72(3):93–99. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.2002.tb06523.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Erulkar AS, Muthengi E. Evaluation of Berhane Hewan: A program to delay child marriage in rural Ethiopia. Int Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2009;35(1):6–14. doi: 10.1363/ifpp.35.006.09. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Morgan A, Haglund BJA. Social capital does matter for adolescent health: evidence from the English HSBC study. Health Promot Int. 2009;24(4):363–372. doi: 10.1093/heapro/dap028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Higgins JPT, Altman DG, Gøtzsche PC et al. The Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ. 2011;343:d5928. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d5928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.East P, Kiernan E, Chavez G. An evaluation of California’s Adolescent Sibling Pregnancy Prevention Program. Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2003;35(2):62–70. doi: 10.1363/3506203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Philliber Research Associates. More Than a Decade of Research on the Children’s Aid Society Carrera Adolescent Pregnancy Prevention Program: 1999-2010. Accord, NY: Philliber Research Associates; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Philliber S, Kaye JW, Herrling S, West E. Preventing pregnancy and improving health care access among teenagers: an evaluation of the Children’s Aid Society–Carrera program. Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2002;34(5):244–251. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Children’s Aid Society. Carrera Adolescent Pregnancy Prevention Program. Available at: http://www.stopteenpregnancy.org. Accessed December 17, 2013.

- 16.Paine-Andrews A, Harris KJ, Fisher JL et al. Effects of a replication of a multicomponent model for preventing adolescent pregnancy in three Kansas communities. Fam Plann Perspect. 1999;31(4):182–189. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Meltzer IJ, Fitzgibbon JJ, Leahy PJ, Petsko KE. A youth development program: lasting impact. Clin Pediatr (Phila) 2006;45(7):655–660. doi: 10.1177/0009922806291019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sieving RE, McRee AL, McMorris BJ, Pettingell SL, Beckman KJ. 4. Prime time: long-term sexual health outcomes of a clinic-linked intervention to prevent pregnancy risk behaviors. J Adolesc Health. 2013;52(2 suppl 1):S7–S8. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sieving RE, Resnick MD, Garwick AW et al. A clinic-based, youth development approach to teen pregnancy prevention. Am J Health Behav. 2011;35(3):346–358. doi: 10.5993/ajhb.35.3.8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sieving RE, McRee A-L, McMorris BJ et al. Prime Time sexual health outcomes at 24 months for a clinic-linked intervention to prevent pregnancy risk behaviors. JAMA Pediatr. 2013;167(4):333–340. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2013.1089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sieving RE, McMorris BJ, Beckman KJ et al. Prime time: 12-month sexual health outcomes of a clinic-based intervention to prevent pregnancy risk behaviors. J Adolesc Health. 2011;49(2):172–179. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2010.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sieving R, Resnick M, Fee R, Oliphant J, Pettingell S. Prime Time: a youth development approach to preventing negative sexual health outcomes. J Adolesc Health. 2003;32(2):154–155. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Robbers MLP. The caring equation: an intervention program for teenage mothers and their male partners. Child Sch. 2008;30(1):37–47. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Erulkar AS, Muthengi E. Evaluation of Berhane Hewan. A Pilot Program to Promote Education and Delay Marriage in Rural Ethiopia. New York, NY: Population Council; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Muthengi E, Erulkar A. New York, NY: Population Council; 2011. Delaying early marriage among disadvantaged rural girls in Amhara, Ethiopia, through social support, education, and community awareness. Brief no. 20. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Population Council. Biruh Tesfa: A Program for Poor, Urban Girls at Risk of Exploitation and Abuse in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Program brief. New York, NY: Population Council; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Erulkar A, Ferede A, Girma W, Ambelu W. Evaluation of “Biruh Tesfa” (Bright Future) program for vulnerable girls in Ethiopia. Vulnerable Child Youth Stud. 2013;8(2):182–192. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Population Council. Transitions to adulthood: Ishraq expands horizons for girls in rural Upper Egypt. Population Briefs. 2006;12(2) [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mona S, Abdel-Tawab N, Elsayed K, El Badawy A, Heba EK. The Ishraq Program for Out-of-School Girls: From Pilot to Scale-Up. Cairo, Egypt: Population Council; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 30.El Badawy A. Assessing the Impact of Ishraq Intervention: a Second Chance pProgram for out of School Rural Girls in Egypt. Cairo, Egypt: Population Council, West Asia and North Africa Office; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Behrman J, Parker S, Todd P. Long-Term Impacts of the Oportunidades Conditional Cash Transfer Program on Rural Youth in Mexico. Göttingen, Germany: Ibero-Amerika Institut fur Wirtschaftsforschung/Instituto Ibero-Americano de Investigaciones Económicas/Ibero-American Institute for Economic Research, Georg-August-Universität Göttingen; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fernald LC, Gertler PJ, Neufeld LM. 10-year effect of Oportunidades, Mexico’s conditional cash transfer programme, on child growth, cognition, language, and behaviour: a longitudinal follow-up study. Lancet. 2009;374(9706):1997–2005. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61676-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gulemetova-Swan M. Evaluating the Impact of Conditional Cash Transfer Programs on Adolescent Decisions About Marriage and Fertility: The Case of Oportunidades. Ann Arbor, MI: ProQuest Information & Learning; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fernald LC, Gertler PJ, Neufeld LM. Role of cash in conditional cash transfer programmes for child health, growth, and development: an analysis of Mexico’s Oportunidades. Lancet. 2008;371(9615):828–837. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60382-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Opportunidades. External evaluation results 2013. Available at: http://www.oportunidades.gob.mx/Portal/wb/Web/external_evaluation_results. Accessed December 17, 2013.

- 36.Lamadrid-Figueroa H, Angeles G, Mroz T . Impact of Oportunidades on Contraceptive Methods Use in Adolescent and Young Adult Women Living in Rural Areas, 1997–2000. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Carolina Population Center; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Edberg M. Part 3: Revised Draft UNICEF/LAC Core Indicators for MICS4 (and Beyond) With Rationale and Sample Module. Panama City, Panama: UNICEF Americas and the Caribbean Regional Office; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 38. Berhane Hewan: Supporting girls in rural Ethiopia. Identifying and costing critical strategies that impact upon child marriage, schooling and reproductive behavior (2010–15). Available at: http://www.popcouncil.org/projects/100_BerhaneHewanEthiopia.asp. Accessed December 17, 2013.

- 39.Catalano RF, Berglund ML, Ryan JAM, Lonczak HS, Hawkins JD. Positive youth development in the United States: research findings on evaluations of positive youth development programs. Ann Am Acad Political Soc Sci. 2004;591(1):98–124. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lerner RM, Brentano C, Dowling EM, Anderson PM. Positive youth development: thriving as the basis of personhood and civil society. New Dir Youth Dev. 2002;2002(95):11–33. doi: 10.1002/yd.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lee-Rife S, Malhotra A, Warner A, Glinski AM. What works to prevent child marriage: a review of the evidence. Stud Fam Plann. 2012;43(4):287–303. doi: 10.1111/j.1728-4465.2012.00327.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bamberger M, Rugh J, Mabry L. RealWorld Evaluation: Working Under Budget, Time, Data, and Political Constraints. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gavin LE, Catalano RF, David-Ferdon C, Gloppen KM, Markham CM. A review of positive youth development programs that promote adolescent sexual and reproductive health. J Adolesc Health. 2010;46(3 suppl):S75–S91. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2009.11.215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Oringanje C, Meremikwu MM, Eko H, Esu E, Meremikwu A, Ehiri JE. Interventions for preventing unintended pregnancies among adolescents. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;(4):CD005215. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005215.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Nastasi BK, Hitchcock J. Challenges of evaluating multilevel interventions. Am J Community Psychol. 2009;43(3–4):360–376. doi: 10.1007/s10464-009-9239-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]