Abstract

Objectives. We examined the association between Black ethnic density and depressive symptoms among African Americans. We sought to ascertain whether a threshold exists in the association between Black ethnic density and an important mental health outcome, and to identify differential effects of this association across social, economic, and demographic subpopulations.

Methods. We analyzed the African American sample (n = 3570) from the National Survey of American Life, which we geocoded to the 2000 US Census. We determined the threshold with a multivariable regression spline model. We examined differential effects of ethnic density with random-effects multilevel linear regressions stratified by sociodemographic characteristics.

Results. The protective association between Black ethnic density and depressive symptoms changed direction, becoming a detrimental effect, when ethnic density reached 85%. Black ethnic density was protective for lower socioeconomic positions and detrimental for the better-off categories. The masking effects of area deprivation were stronger in the highest levels of Black ethnic density.

Conclusions. Addressing racism, racial discrimination, economic deprivation, and poor services—the main drivers differentiating ethnic density from residential segregation—will help to ensure that the racial/ethnic composition of a neighborhood is not a risk factor for poor mental health.

Recent years have seen an increase in the number of studies examining the association between the residential concentration of racial/ethnic minorities (ethnic density) and health, with increasingly sophisticated statistical techniques and theoretical frameworks helping to identify the relevance of ethnic density effects. Despite these improvements, the association between ethnic density and health, given the concentration of poverty in areas of higher ethnic density, is still a puzzling phenomenon.

The literature is characterized by inconclusive findings in both the direction and the size of ethnic density effects. Reviews have asserted that ethnic density effects are stronger for mental health1 than for physical health, mortality, and health behaviors,2 but even among the latter set of outcomes, protective ethnic density effects are more common than adverse associations.2 One common finding among ethnic density studies, regardless of health outcome, is the variation in results across and within racial/ethnic groups. For example, US studies often report protective associations among Latinos but mostly detrimental associations for African Americans,2 and the few studies that have examined subgroups among broad “US Black” ethnic categories have found differences by age,3 gender,4,5 and nativity.6,7 Determining the specific populations for which ethnic density effects are protective or detrimental can help in achieving a greater understanding of the potential mechanisms by which ethnic density is associated with health.

Another methodological improvement that would clarify the association between ethnic density and health is adequate adjustment for area resource deprivation. The positive correlation that exists between ethnic density and deprivation, and the established association between area deprivation and poor health,8 may have a twofold effect in concealing ethnic density effects: first, by overriding protective effects of ethnic density; second, by complicating analytical attempts at disentangling harmful deprivation effects from protective ethnic density benefits, even with the use of multilevel methods. Reviews of the literature have highlighted the inadequate adjustment for area deprivation as one of the main limitations in current studies, most of which control for only 1 measure of area deprivation (e.g., median income) or, in some cases, do not adjust for any relevant confounders.1,2

Although the appropriate adjustment for area deprivation is critical for detecting ethnic density effects, it is not sufficient. To properly capture the associations between ethnic density, area resource deprivation, and health, the potential suppressing effects of area deprivation in the association between ethnic density and health should be modeled. Detrimental ethnic density effects may not be due to the concentration of ethnic minorities in an area but to the concurrent concentration of poverty and social adversity,9 and appropriate modeling can portray the relative contribution of ethnic density and area deprivation to health.

In addition to differentiating ethnic density effects between subgroups and accurately modeling and adjusting for area deprivation, the possible nonlinearity in the association between ethnic density and health, and the potential thresholds at which ethnic density exerts protective or nonprotective effects on health, need to be addressed.10 The combination of methods and theoretical frameworks aiming to understand the importance of concentrated poverty and threshold effects for ethnic density might also be useful in clarifying the difference between ethnic density and residential segregation. Although ethnic density is framed in terms of social support, racial/ethnic diversity, and a stronger sense of community, residential segregation is a direct consequence of current and historical racism and discrimination, and is recognized as a determinant of racial/ethnic health inequalities.11 However, both ethnic density and residential segregation are conceptualized through use of a measure of racial/ethnic residential concentration, and it is unclear at what point the hypothesized protective benefits of ethnic density are overcome by the pernicious effects of racial residential segregation. Understanding this difference and its drivers has important implications for social and public health policy, as it would allow the promotion of factors that harness the protective effects of ethnic density while targeting the factors related to racial residential segregation.

We examined the association between Black ethnic density and depressive symptoms among African Americans in the National Survey of American Life (NSAL), to ascertain (1) the differential effects of ethnic density across subgroups of African American NSAL respondents and (2) the protective or detrimental thresholds of Black ethnic density. We addressed these 2 study aims while accounting for, and adequately modeling, the potential suppressing effects of area resource deprivation on the association between ethnic density and an important mental health outcome.

We selected depressive symptoms as the mental health outcome in this study because the literature is consistent regarding the ethnic density effects of outcomes such as psychoses, but not about the association between Black ethnic density and depression.5 Although the prevalence of major depression is lower among African Americans than among the White majority, the prevalence of depressive symptoms and chronic low mood is high among this population,12–14 and understanding any protective or risk factors of psychological distress, including at the neighborhood level, remains a priority.

We focused on African Americans because most ethnic density studies have been conducted in this population, and it is the group in which ethnic density effects have been found to be the most detrimental.1,2 Some previous studies have modeled nonlinear associations between Black ethnic density and several physical health indicators,15–18 but not mental health ones. In all of these prior studies, potential cutoff points have not been based on formal threshold examinations. In addition, prior studies have analyzed non-Hispanic Black respondents. In this study, we focused specifically on African Americans because of the documented heterogeneity of sociodemographic characteristics,19 health profiles,20–22 and ethnic density effects23 in the non-Hispanic Black population.

METHODS

The NSAL is a nationally representative household study of African Americans and Caribbean Blacks, including a sample of non-Hispanic Whites who live in areas in which at least 10% of residents are African American.24 Data were collected between February 2001 and June 2003 through use of a national multistage probability design. A total of 6082 face-to-face interviews took place with persons aged 18 years or older (72.3% response rate), including 3570 African Americans, 891 non-Hispanic Whites, and 1621 Blacks of Caribbean descent.25

We geocoded NSAL data to the 2000 US Census to obtain information on area deprivation and ethnic density. We linked census data, via special license access, to the NSAL by means of census tract Federal Information Processing Standards codes. We defined Black ethnic density as the percentage of Blacks in a census tract; we analyzed it as a continuous measure and modeled it as a 10% increase.

We measured depressive symptoms with the 12-item Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression (CES-D) Scale.26 The CES-D asks respondents how often in the past week they had experienced several symptoms, including feeling depressed, feeling like everything was an effort, and enjoying life. Response categories ranged from 0 (rarely or none of the time) to 3 (most or all of the time). We reversed positive statements so that higher scores reflect more depressive symptoms, and we modeled the CES-D scale as a continuous measure (mean = 6.70; SD = 5.70; Cronbach α = 0.76).

We examined whether the association between ethnic density and depressive symptoms among African Americans varied across the following sociodemographic characteristics: age, gender, household income, education, employment status, and area deprivation. We equivalized household income using a modified Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development (OECD) Equivalence Scale, which allowed 1.0 for the first adult in the household, 0.5 for other adults, and 0.3 for children under 17. We calculated equivalized income by dividing household disposable income by the equivalence score for the household and categorized it into 5 equally sized income quintiles. We categorized employment status as “employed or in fulltime education,” “unemployed,” “unemployed due to long term sickness,” and “looking after the home or retired.” We categorized education into “less than high school,” “high school degree or GED,” “some college,” and “college degree or more.”

In line with other studies of ethnic density using the NSAL data set,23 we assessed area deprivation with a variable composed of 4 indicators of area-level socioeconomic resource disadvantage: percentage of persons living at or below 100% of the federal poverty level, percentage of persons aged 25 years and older with less than a high school level of education, median household income, and percentage of households receiving public assistance. Exploratory factor analysis, which we used to summarize area-level socioeconomic status (SES) variables, indicated that the 4 measures were captured by a single factor, with higher scores representing higher deprivation.

We conducted analyses in 2 steps. First, we examined the assumption of linearity in the relationship between ethnic density and health and identified any threshold effects. Second, we explored differential associations between ethnic density and depressive symptoms across specific sociodemographic subgroups.

We assessed the assumption of linearity by using the likelihood ratio test to compare the goodness of fit between 2 nested models that examined the association between ethnic density and depressive symptoms. Model 1 included all covariates and a linear ethnic density term, and model 2 additionally included a squared ethnic density term. After assessing the linearity of the association, we examined the existence of any threshold by conducting a multivariable regression spline model to determine the precise level of ethnic density at which the slope of the relationship with depressive symptoms changed (i.e., the location of the knot).

After ascertaining the shape and threshold, we examined whether the association between ethnic density and depressive symptoms varied depending on sociodemographic characteristics. To explore the association between ethnic density and depressive symptoms, and the relative contribution of ethnic density and area deprivation to depressive symptoms, we fitted random-effects multilevel linear regression models in 2 sequential steps. Model 1 included Black ethnic density and all individual-level covariates, and model 2 additionally adjusted for area deprivation. This allowed us to examine the independent contributions of ethnic density and area deprivation, as well as the extent to which ethnic density effects were masked by area deprivation.

We examined the differential effects of ethnic density on depressive symptoms by stratifying the models described here by the particular sociodemographic subgroup (e.g., males) while adjusting for all other covariates. When analyzing the differential effects among the 3 measures of SES (income, education, and employment), we analyzed each measure independently without adjusting for the other SES measures, since collinearity would have made it difficult to interpret the relationship of single variables.

To incorporate the findings from the threshold examinations, we conducted all regression models in 2 separate sets of analyses: first, using a variable of ethnic density that was censored at the threshold, and second, using a measure of Black ethnic density that started at the threshold and ranged to the highest values of Black ethnic density.

We also applied propensity score matching methods to the NSAL data to produce propensity scores for living in the lowest quintile of Black ethnic density compared with living in the highest quintile, and estimated the depression score of African Americans living in neighborhoods with the highest ethnic density compared with living in neighborhoods with the lowest ethnic density. In order for propensity scores to be comparable to results of the multilevel regression models, we split the data into 2 groups: below and above the threshold. We then used propensity scores to match African Americans in the top and bottom quintile on income, education, employment status, marital status, gender, and age using a nearest-neighbor algorithm with a caliper matching of ±0.03. We used matched paired t tests to test for differences in CES-D score between individuals in the highest and lowest quintiles of the matched sets.

We conducted all analyses with Stata version 12 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX) and adjusted them for age, gender, marital status, household income, education, employment status, and area deprivation.

RESULTS

The NSAL included a total of 3570 African American respondents clustered within 381 census tracts. Black ethnic density ranged from 0.7% to 98.99%, with a mean of 56.83% (SD = 28.58).

Assumption of Linearity and Threshold Effects

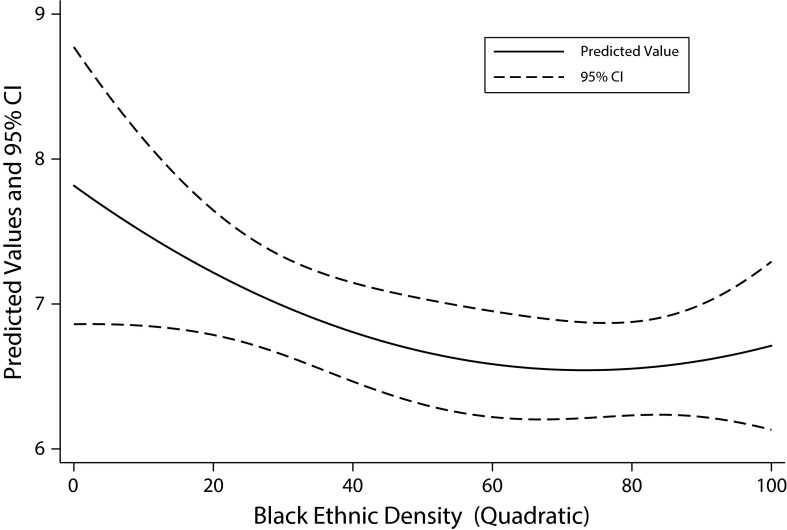

Examinations of the assumption of linearity in the association between ethnic density and depressive symptoms provided evidence for a nonlinear relationship, since a model with a quadratic ethnic density term had a slightly better fit for the data than a model with a linear term only (likelihood-ratio χ2 = 3.81; P = .051). A visual representation of the predicted values for depressive symptoms as ethnic density increased is provided in Figure 1. A curvilinear association between Black ethnic density and depressive symptoms can be observed among African Americans, with protective effects up until around 80% ethnic density, when values of depressive symptoms begin to increase. Results of the multivariable regression spline model established the location of the knot at 84.68%, which we assigned as the threshold.

FIGURE 1—

Predicted values for depressive symptoms among African Americans per 1% increase in Black ethnic density: National Survey of American Life, 2001–2003.

Note. CI = confidence interval. Depressive symptoms were measured by the 12-item Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression (CES-D) Scale.26 Model adjusts for age, gender, marital status, household income, education, employment, and area deprivation, and it takes into account area-level clustering.

An increase in Black ethnic density up to the threshold (< 84.68%) was associated with decreased values of depressive symptoms in model 1 (b = –0.09; SE = 0.05), although this association only reached statistical significance upon adjustment for area deprivation in model 2 (b = –.012; SE = 0.05; P < .05). Controlling for area deprivation strengthened the association between increased Black ethnic density and decreased depressive symptoms. When detrimental ethnic density (≥ 84.68%) was examined in model 1, a detrimental association was found whereby as ethnic density increased, so did depressive symptoms (b = 1.20; SE = 0.43; P < .01). The effect size of the association was reduced once area deprivation was adjusted for in model 2 (b = 1.02; SE = 0.46; P < .05).

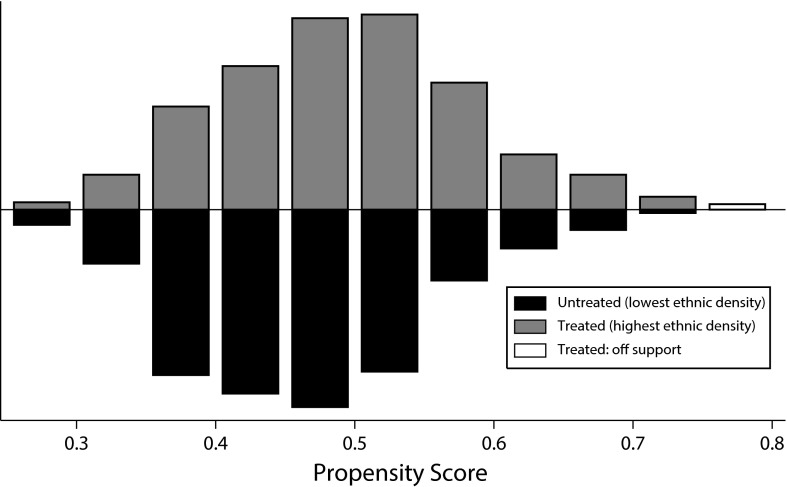

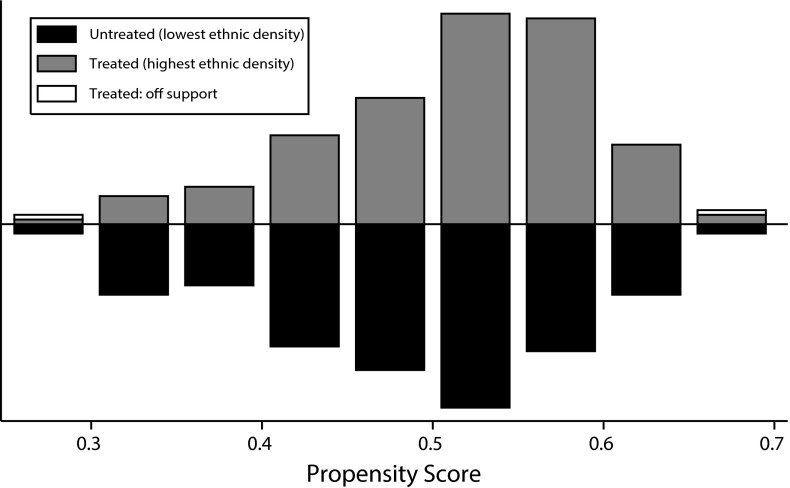

Results of the propensity score matching analyses showed sufficient overlap in propensity scores by exposure categories (lowest versus highest ethnic density) across both groups (Figures 2 and 3), with all but 3 and 2 people (in the below- and above-threshold group, respectively) matched. Similar differences from those observed in the multilevel regression models were found in the propensity score matching analyses. For analyses conducted before the threshold, the exposed group (highest quintile of ethnic density) had a significantly lower CES-D score than the unexposed group (lowest quintile of ethnic density; difference = −0.75; 95% confidence interval [CI] = −1.46, −0.04). For analyses conducted at and after the threshold, the exposed group had a significantly higher CES-D score than the unexposed group (difference = 1.78; 95% CI = 0.58, 2.98).

FIGURE 2—

Overlap in propensity scores by exposure groups (lowest versus highest Black ethnic density) for data below the threshold: National Survey of American Life, 2001–2003.

Note. The threshold of a protective effect against depressive symptoms was a Black ethnic density of 84.68%.

FIGURE 3—

Overlap in propensity scores by exposure groups (lowest vs highest Black ethnic density) for data at and above the threshold: National Survey of American Life, 2001–2003.

Note. The threshold of a protective effect against depressive symptoms was a Black ethnic density of 84.68%.

Differential Associations Across Sociodemographic Subgroups

Although the overall effect was significant in the fully adjusted models, subgroup analyses revealed that ethnic density was associated with depressive symptoms only among females. For this group, an increase in Black ethnic density up to the threshold was associated with improved mental health, whereas an increase in Black ethnic density above 84.68% was associated with an increase in depressive symptoms, even after adjustment for area deprivation (Table 1).

TABLE 1—

Differential Associations Between Black Ethnic Density (10% Increase) and Depressive Symptoms Among African Americans: National Survey of American Life, 2001–2003

| Protective Ethnic Density (Minimum to < 84.68%) |

Detrimental Ethnic Density (84.68% to Maximum) |

|||

| Characteristic | Model 1, b (SE) | Model 2, b (SE) | Model 1, b (SE) | Model 2, b (SE) |

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 0.04 (0.08) | 0.02 (0.08) | 0.78 (0.62) | 0.58 (0.68) |

| Female | −0.16 (0.06)** | −0.21 (0.07)*** | 1.52 (0.58)** | 1.34 (0.61)* |

| Age | ||||

| 18–29 | 0.02 (0.10) | 0.01 (0.11) | 2.28 (0.96)* | 1.76 (1.04) |

| 30–44 | −0.15 (0.08) | −0.16 (0.09) | 1.67 (0.79)* | 1.44 (0.84) |

| 45–59 | −0.18 (0.10) | −0.24 (0.11)* | 1.65 (0.88) | 1.79 (0.94) |

| ≥ 60 | −0.03 (0.12) | −0.08 (0.13) | −0.85 (0.75) | −0.78 (0.78) |

| Household income, quintile | ||||

| Bottom | −0.30 (0.12)** | −0.44 (0.13)*** | 1.81 (1.05) | 1.96 (1.06) |

| Second | −0.17 (0.11) | −0.30 (0.12)* | 1.01 (1.10) | 0.54 (1.13) |

| Middle | −0.10 (0.11) | −0.18 (0.11) | 0.97 (0.96) | 0.39 (1.00) |

| Fourth | 0.13 (0.11) | 0.11 (0.12) | 0.86 (0.87) | 1.03 (0.95) |

| Highest | 0.11 (0.10) | 0.24 (0.11)* | 1.76 (0.77)* | 2.00 (0.92)* |

| Educational qualifications | ||||

| < high school degree | −0.19 (0.12) | −0.21 (0.13) | 0.62 (0.95) | 0.54 (0.95) |

| High school degree or GED | −0.09 (0.08) | −0.23 (0.08)** | 0.81 (0.75) | 0.33 (0.83) |

| Some college | 0.02 (0.09) | −0.04 (0.10) | 2.47 (0.86)*** | 2.33 (0.94)** |

| ≥ college degree | 0.12 (0.11) | 0.09 (0.12) | 2.33 (0.91)** | 2.18 (0.94)* |

| Employment status | ||||

| Employed or in full-time education | −0.07 (0.06) | −0.16 (0.06)** | 1.76 (0.50)*** | 1.67 (0.54)* |

| Unemployed | −0.12 (0.18) | −0.13 (0.18) | 1.19 (1.70) | 1.20 (1.73) |

| Unemployed due to long-term sickness | 0.32 (0.23) | 0.06 (0.26) | 0.32 (2.34) | 0.64 (2.36) |

| Looking after home or retired | −0.22 (0.15) | −0.34 (0.17)* | −0.02 (0.85) | 0.04 (0.88) |

| Area deprivation, quintile | ||||

| Least deprived | −0.04 (0.09) | 2.27 (2.78) | ||

| Second | −0.13 (0.13) | 2.06 (1.07) | ||

| Middle | −0.31 (0.12)** | 2.17 (1.78) | ||

| Fourth | −0.30 (0.14)* | 0.72 (0.90) | ||

| Most deprived | 0.21 (0.01) | 0.97 (0.68) | ||

Note. Model 1 adjusts for age, gender, marital status, employment, education, and household income. Analyses for the socioeconomic position variables (income, education, and employment) adjust only for age, gender, and marital status. Model 2 additionally adjusts for area deprivation. Black ethnic density was defined as percentage Black in a census tract and was analyzed as a continuous measure and modeled as a 10% increase. Depressive symptoms were measured by the 12-item Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression (CES-D) Scale.26

*P < .05; **P < .01; ***P < .001.

A suggestion of differential effects of age was found in the association between Black ethnic density and mental health for both categories of ethnic density. For analyses of Black ethnic density below the threshold, there was a trend for a larger protective ethnic density effect for those aged 30 to 59 years than for those younger or older, although associations were statistically significant only for African Americans aged 45 to 59 years. When we analyzed ethnic density above the threshold, effects were not statistically significant for any age group, but there was a trend for detrimental ethnic density effects for African Americans younger than 60 years, such that as ethnic density increased, so did depressive symptoms. This association was not present for those aged 60 years and older.

Black ethnic density effects varied across some socioeconomic categories. In general, Black ethnic density tended to be protective for the lower socioeconomic positions and detrimental for the better-off categories. For example, in the case of household income, an increase in Black ethnic density up to the threshold was significantly associated with decreased depressive symptoms for the bottom and second income quintiles, but it was associated with increased depressive symptoms for the highest income quintile. For analyses of Black ethnic density above the threshold, a negative association between increased ethnic density and increased depressive symptoms was found to be statistically significant only for respondents in the highest household income quintile (Table 1).

In the case of employment, the detrimental association between ethnic density and depression was stronger for African Americans in the highest employment category, but we observed the protective association in both the highest and lowest employment statuses (only when we adjusted for area deprivation). We also found that the Black ethnic density effect varied between the most- and least-educated respondents. Increased Black ethnic density up to the threshold was associated with improved mental health only among people with less than a college education, an effect that was statistically significant for those with a high school degree or GED but no college education. When we modeled ethnic density after the threshold, there was a strong and statistically significant association between ethnic density and increased depressive symptoms for the 2 college-education categories, with much smaller and nonsignificant associations for the less-than-college-education categories.

When we examined the association between ethnic density and mental health across categories of area deprivation, we found that the association between increased Black ethnic density up to the threshold and decreased depressive symptoms was statistically significant for the third and fourth quintiles of deprivation, with a suggestion of similar effects for the least-deprived 2 quintiles whereby, as ethnic density increased, depressive symptoms tended to decrease. We found no associations between mental health and ethnic density at or above the threshold.

In all subgroup analyses, adjusting for area deprivation strengthened the protective association between Black ethnic density below the threshold and depressive symptoms, but it decreased the strength of the detrimental effect of ethnic density at or above the threshold. For analyses at the highest levels of ethnic density, adjusting for area deprivation had a stronger effect on reducing the detrimental association between the highest levels of ethnic density and increased mental health than it had on strengthening protective ethnic density effects in the lowest levels of ethnic density.

DISCUSSION

We addressed several limitations in the literature on ethnic density by exploring whether a threshold exists in the association between Black ethnic density and depressive symptoms among African Americans, and by examining whether there are differential effects of ethnic density across sociodemographic groups.

In the first part of the analyses, we ascertained that the association between Black ethnic density and depressive symptoms among African Americans is not linear in the NSAL data set. We found that increases in ethnic density are associated with reductions in depressive symptoms up to about 85% ethnic density, when this association changes direction and ethnic density becomes detrimental. Other studies of ethnic density that have modeled nonlinear relationships between ethnic density and health have also reported that higher levels of Black ethnic density are associated with increased risk of preterm birth,16–18 low birth weight,18 and mortality.15 Although these studies neither focused specifically on African Americans nor formally assessed the existence of a threshold, results of the present and previous studies provide consistent evidence for an adverse association between Black ethnic density and health at the highest categories of ethnic density.

Theories of the ethnic density effect propose specific mechanisms that link ethnic density to improved health outcomes, including enhanced social cohesion, mutual social support, a stronger sense of community and belongingness, and a reduction in the exposure to interpersonal racism. These mechanisms are thought to provide a buffering effect from the direct or indirect consequences of discrimination and racial harassment, as well as from the detrimental effects of low status stigma.10,27–29 Findings from this and previous studies regarding the nonlinearity of Black ethnic density suggest that after a certain threshold (around 85% in the case of the association between Black ethnic density and depressive symptoms as presented here), the benefits of Black ethnic density for African Americans living in predominantly Black areas are supplanted by other conflicting, deleterious processes resulting from extreme residential concentration, a consequence of a long-standing history of institutional racism.11

The characteristics of the distinctive residential segregation experienced by African Americans are such that in the highest levels of ethnic density, the concentration of poverty, chronic underinvestment, and social isolation overshadows any potential benefits that may emerge from living among other African Americans. It is this concentration of social and economic deprivation, and not the concentration of people from a particular racial/ethnic group, that produces disenfranchisements that inhibit the emergence of any protective factors of ethnic density, as shown by the extant research on the pernicious effect of residential segregation on health.

Of particular relevance to our results are those of a previous study examining the association between ethnic density and depressive symptoms among African Americans using data from the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis.5 This study, despite theoretically distinguishing ethnic density from residential segregation, did not explicitly model the nonlinear association between ethnic density and health5 and reported a detrimental association between higher Black residential concentration and increased CES-D scores among African Americans, consistent with the residential segregation literature, and with some of our findings. Given the study’s high proportion of African American respondents in neighborhoods of the highest residential concentration (almost half the study’s African American population lived in neighborhoods with at least 75% African American ethnic density), modeling approaches similar to those employed here might have yielded empirical, in addition to theoretical, distinctions between ethnic density and residential segregation—the authors do suggest possible nonlinear associations between residential concentration and health.5 Future studies examining the association between racial/ethnic residential concentration and health that model nonlinear and threshold effects might contribute to our understanding of the power of area resource deprivation, concentrated poverty, and chronic disinvestment in trumping ethnic density effects.

We aimed to model the relationship between ethnic density and area deprivation by examining the association between Black ethnic density and depressive symptoms before and after adjusting for area deprivation; however, it is possible that at the highest levels of ethnic density our measure of neighborhood poverty could not fully capture the degree and impact of socioeconomic deprivation. We can nonetheless observe in our models a suppressing effect of area deprivation in the association between ethnic density and depressive symptoms: when ethnic density was censored at less than 84.68%, adjustments for area deprivation strengthened the protective association between Black ethnic density and decreased depressive symptoms. In fact, the association between ethnic density and depressive symptoms below the threshold reached statistical significance only after we adjusted for area deprivation. When we analyzed ethnic density at 84.68% and higher, however, adjustment for area deprivation weakened the detrimental association between Black ethnic density and increased depressive symptoms. Our findings also show that area deprivation matters more in the neighborhoods with the highest ethnic density, since changes in effect sizes were larger upon adjustment for area deprivation in the analyses in which ethnic density was modeled after the threshold.

The second part of the analyses explored whether ethnic density effects are uniform across different sociodemographic groups. We found distinct differences across gender and socioeconomic position. Whereas no associations were found between Black ethnic density and mental health among African American men, African American women’s depressive symptoms were strongly associated with Black ethnic density. Gender effects of Black ethnic density have been reported in other studies,4,5 suggesting a differential engagement with the ethnic composition of the neighborhood for men and women. Other examinations of gender differences in neighborhood effects on health have also found that the residential environment may be more important for women’s health.30 The authors proposed 3 explanations for the reported results, including different perceptions of the environment, differential exposure to the various aspects of the local environment, and variations in vulnerability to aspects of the local environment.30

When we examined differentials by socioeconomic position, we found suggestions of differences in the association between Black ethnic density and depressive symptoms across individual-level socioeconomic indicators. Overall, ethnic density bestowed a protective effect on the mental health of the most disadvantaged and was detrimental for African Americans in higher socioeconomic positions. Whereas increases in Black ethnic density up to 84.68% (the threshold) were associated with decreased depressive symptoms among those in the first 2 quintiles of household income or with less than a college education, increases above the threshold were associated with higher depressive symptoms among African Americans in the highest income quintile or with at least some college education. These results suggest that, for the most affluent African Americans, the protective benefits of Black ethnic density are offset by conflicting processes, perhaps related to the mismatch between their individual-level SES and the aggregate levels of deprivation of the area where they live. The average affluent Black person lives in a poorer neighborhood than the average lower-income White resident,31 and it is likely that the socioeconomic isolation experienced by African Americans living in neighborhoods with higher levels of Black ethnic density11 restricts the opportunities for increased socioeconomic and health statuses among more affluent African Americans.

Limitations

Although this study presents important contributions to the ethnic density literature, limitations need to be acknowledged. First, even though we have established a threshold by which Black ethnic density ceases to be protective of depressive symptoms, this may be a context-specific threshold that varies among other populations or data sets. We also examined the differential associations between ethnic density and 1 mental health indicator among an individual population, African Americans, and these differential associations might not be reflected among other ethnic groups in the United States or elsewhere.

We analyzed data from the NSAL, which was collected between 2001 and 2003. Future studies on ethnic density should ideally analyze more recent data sets. However, despite its dated sample, the NSAL is one of the largest and most comprehensive surveys focused on the social circumstances and mental health of the US Black population, and it is difficult to find a publicly available data set with a similar level of detailed and relevant information.

Another limitation of our study is the cross-sectional nature of the NSAL data, which did not allow us to infer causality on the associations observed. We aimed to partly address this with the use of propensity score matching, and we did find results similar to those obtained with multilevel regression methods. We were not, however, able to assess reverse causality or cumulative exposure effects, which can be examined only with longitudinal data. Future studies using longitudinal data to examine the duration of exposure, changes in ethnic density, and lagged effects would provide a needed contribution to the literature. Despite these limitations, the findings reported here provide additional insight into the potential pathways linking ethnic density to decreased depressive symptoms, and to the detrimental association between concentrated area resource deprivation and poor mental health.

Conclusions

Strong policy implications emerge from our results: whereas the residential concentration of African Americans is protective of their mental health, the concentration of poverty and disadvantage in racial/ethnic minority communities, captured in the most extreme levels of ethnic density, exerts the opposite effect. To ensure that the racial/ethnic composition of a neighborhood is not a risk factor for poor mental health, the main drivers differentiating ethnic density from racial residential segregation—racism, racial discrimination, economic deprivation, and poor services—should be addressed.

Acknowledgments

The National Survey of American Life was funded by the National Institute of Mental Health (U01-MH57716), with supplemental support from the National Institutes of Health Office of Behavioral and Social Science Research, and by the National Institute on Aging (5R01 AG02020282), supplemented by the National Institute on Drug Abuse and the University of Michigan. L. Bécares was supported by a UK Economic and Social Research Council grant (ES/K001582/1) and by a Hallsworth Research Fellowship. This work was partially funded by an Investing in Success grant from the University of Manchester to L. Bécares.

We are grateful to the anonymous reviewers for helpful comments that improved the article.

Human Participant Protection

Approval for the National Survey of American Life study was obtained through the University of Michigan institutional review board.

References

- 1.Shaw R, Atkin K, Bécares L et al. Impact of ethnic density on adult mental disorders: narrative review. Br J Psychiatry. 2012;201(1):11–19. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.110.083675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bécares L, Shaw R, Nazroo J et al. Ethnic density effects on physical morbidity, mortality and health behaviors: a systematic review of the literature. Am J Public Health. 2012;102(12):e33–e66. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2012.300832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jackson S, Anderson R, Johnson N, Sorlie P. The relation of residential segregation to all-cause mortality: a study in black and white. Am J Public Health. 2000;90(4):615–617. doi: 10.2105/ajph.90.4.615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chang V, Hillier A, Mehta N. Neighborhood racial isolation, disorder, and obesity. Soc Forces. 2009;87(4):2063–2092. doi: 10.1353/sof.0.0188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mair C, Diez Roux A, Osypuk T, Rapp S, Seeman T, Watson K. Is neighbourhood racial/ethnic composition associated with depressive symptoms? The multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis. Soc Sci Med. 2010;71(3):541–550. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.04.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mason S, Kaufman J, Emch M, Hogan V, Savitz D. Ethnic density and preterm birth in African-, Caribbean-, and US-born non-Hispanic black populations in New York City. Am J Epidemiol. 2010;172(7):800–808. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwq209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Baker A, Hellerstedt W. Residential racial concentration and birth outcomes by nativity: do neighbors matter? J Natl Med Assoc. 2006;98(2):172–180. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pickett K, Pearl M. Multilevel analyses of neighbourhood socioeconomic context and health outcomes: a critical review. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2001;55(2):111–122. doi: 10.1136/jech.55.2.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Williams D, Mohammed S, Leavell J, Collins C. Race, socioeconomic status and health: complexities, ongoing challenges and research opportunities. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2010;1186:69–101. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.05339.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pickett K, Wilkinson R. People like us: ethnic group density effects on health. Ethn Health. 2008;13(4):321–334. doi: 10.1080/13557850701882928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Williams D, Collins C. Racial residential segregation: a fundamental cause of racial disparities in health. Public Health Rep. 2001;116(5):404–416. doi: 10.1093/phr/116.5.404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lincoln K, Chatters L, Taylor R, Jackson J. Profiles of depressive symptoms among African Americans and Caribbean blacks. Soc Sci Med. 2007;65(2):200–213. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.02.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dunlop D, Song J, Lyons J, Manheim L, Chang R. Racial/ethnic differences in rates of depression among preretirement adults. Am J Public Health. 2003;93(11):1945–1952. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.11.1945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Breslau J, Aguilar S, Kendler K, Su M, Williams D, Kessler R. Specific race-ethnic differences in risk for psychiatric disorder in a USA national sample. Psychol Med. 2006;36(1):57–68. doi: 10.1017/S0033291705006161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hutchinson R, Putt M, Dean L, Long J, Montagnet C, Armstrong K. Neighborhood racial composition, social capital and black all-cause mortality in Philadelphia. Soc Sci Med. 2009;68(10):1859–1865. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Reichman N, Teitler J, Hamilton E. Effects of neighborhood racial composition on birthweight. Health Place. 2009;15(3):784–791. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2009.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mason S, Kaufman J, Daniels J, Emch M, Hogan V, Savitz D. Neighborhood ethnic density and preterm birth across seven ethnic groups in New York City. Health Place. 2011;17(1):280–288. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2010.11.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shaw R, Pickett K, Wilkinson R. Ethnic density effects on birth outcomes and maternal smoking during pregnancy in the US Linked Birth and Infant Death data set. Am J Public Health. 2010;100(4):707–713. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.167114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kalmijn M. The socioeconomic assimilation of Caribbean American blacks. Soc Forces. 1996;74(3):911–930. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Williams D, Jackson J. Race/ethnicity and the 2000 census: recommendations for African American and other black populations in the United States. Am J Public Health. 2000;90(11):1728–1730. doi: 10.2105/ajph.90.11.1728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Williams D, Haile R, Gonzalez H, Neighbors H, Baser R, Jackson J. The mental health of black Caribbean immigrants: results from the National Survey of American Life. Am J Public Health. 2007;97(1):52–59. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2006.088211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nazroo J, Jackson J, Karlsen S, Torres M. The black diaspora and health inequalities in the US and England: does where you go and how you get there make a difference? Sociol Health Illn. 2007;29(6):811–830. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9566.2007.01043.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bécares L, Nazroo J, Jackson J, Heuvelman H. Ethnic density effects among Caribbean people in the US and England: a cross-national comparison. Soc Sci Med. 2012;75(12):2107–2115. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2012.03.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jackson J, Torres M, Caldwell C et al. The National Survey of American Life: a study of racial, ethnic and cultural influences on mental disorders and mental health. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2004;13(4):196–207. doi: 10.1002/mpr.177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Heeringa S, Torres M, Sweetman J, Baser R. Sample Design, Weighting and Variance Estimation for the 2001–2003 National Survey of American Life (NSAL) Adult Sample. Technical Report. Ann Arbor, MI: Survey Research Center of the Institute for Social Research at the University of Michigan; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Radloff L. The CES-D Scale: a self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Appl Psychol Meas. 1977;1(3):385–401. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bécares L, Nazroo J, Stafford M. The buffering effects of ethnic density on experienced racism and health. Health Place. 2009;15(3):670–678. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2008.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Halpern D, Nazroo J. The ethnic density effect: results from a national community survey of England and Wales. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2000;46(1):34–46. doi: 10.1177/002076400004600105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Smaje C. Ethnic residential concentration and health: evidence for a positive effect? Policy Polit. 1995;23(3):251–269. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stafford M, Cummins S, Macintyre S, Ellaway A, Marmot M. Gender differences in the associations between health and neighbourhood environment. Soc Sci Med. 2005;60(8):1681–1692. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.08.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Logan J. Separate and unequal: the neighborhood gap for blacks, Hispanics and Asians in metropolitan America. US2010 Project. Brown University, 2011. Available at: http://www.s4.brown.edu/us2010/Data/Report/report0727.pdf. Accessed January 10, 2013.