Abstract

Objectives. We surveyed young men on their experiences of police encounters and subsequent mental health.

Methods. Between September 2012 and March 2013, we conducted a population-based telephone survey of 1261 young men aged 18 to 26 years in New York City. Respondents reported how many times they were approached by New York Police Department officers, what these encounters entailed, any trauma they attributed to the stops, and their overall anxiety. We analyzed data using cross-sectional regressions.

Results. Participants who reported more police contact also reported more trauma and anxiety symptoms, associations tied to how many stops they reported, the intrusiveness of the encounters, and their perceptions of police fairness.

Conclusions. The intensity of respondent experiences and their associated health risks raise serious concerns, suggesting a need to reevaluate officer interactions with the public. Less invasive tactics are needed for suspects who may display mental health symptoms and to reduce any psychological harms to individuals stopped.

The criminal justice system has been recognized increasingly as a threat to physical and mental health.1–3 Changes in policing practices in the past 2 decades have brought a growing number of urban residents into contact with the criminal justice system,4 making the consequences of such contact increasingly important to understand. In the past 20 years, many cities have shifted to a proactive policing model in which officers actively engage citizens in high-crime areas to detect imminent criminal activity or disrupt circumstances interpreted as indicia that “crime is afoot.”5

One way proactive policing is sanctioned constitutionally is through a tactic known as Terry stops,6 in which police temporarily detain and perhaps frisk or search persons they suspect are, were, or are about to be engaged in criminal activity. Between 2004 and 2012, the New York City Police Department recorded more than 4 million such stops.7 Large cities such as Philadelphia, Pennsylvania,8 and Los Angeles, California,9 have experienced similar practices, and a survey of Chicago, Illinois, public school students10 found that police had stopped and questioned about half and “told them off or told them to move on.” A quarter to a third of these students reported having been searched by police. Overall, the burden of police contact in each of these cities falls predominantly on young Black and Latino males,8,10,11 with significant disparities in police conduct across neighborhoods.12,13

Recent studies suggest that Terry stops are often harsh encounters in which physical violence, racial/ethnic degradation, and homophobia are commonplace,14,15 raising the potential for adverse mental health effects. We examined associations between involuntary police contact and mental health among young men in New York City, where Terry stops and proactive policing (commonly known as “stop and frisk” activity) have been the subject of contentious debate and litigation.11,16,17

Public perceptions of stop and frisk vary widely, with some observers raising concerns about the aggressive nature of many stops18 and their shaky constitutional grounds.19 Others dismiss these concerns as outweighed by the benefit of crime deterrence20 or as inconveniences that should be accepted as a “fact of urban life.”21

Most of what is known about New Yorkers’ police contact is derived from observational incident-level data,12,16 journalistic accounts,18,19,21 or convenience samples22 and suggests a complex and conflicted relationship between community members and the police. However, such accounts provide only limited insight into the broader implications of the practice. We have advanced understanding of the cumulative experiences of young men with these police encounters using a population-based survey.

BACKGROUND

Police contact may threaten the health of individuals stopped in several ways. In New York City, approximately half of recorded stops involve the physical contact of a frisk, and officers describe approximately 20% as involving the “use of force.”11 The physically invasive, often rough manner in which officers approach citizens raises the risk of injury. Qualitative research suggests that young men are often thrown to the ground or slammed against walls in these encounters.15,23 Individuals stopped by the police may also face emotional trauma from such treatment in the face of unwarranted accusations of wrongdoing.

Proactive police stops are predicated on low levels of suspicion and rarely result in arrest, summons, or seizure of contraband,12 suggesting that the vast majority of individuals stopped have done nothing wrong.24 Contacts of this nature may trigger stigma and stress responses and depressive symptoms.25 These stresses can be compounded when police use harsh language, such as racial invective or taunts about sexuality.14 Finally, to the extent that individuals stopped believe that they were targeted because of their race or ethnicity or may be targeted again, they may experience symptoms tied to the stresses of perceived or anticipated racism.26,27

On the other hand, a visible, proactive police presence can improve individual and population health through improved public safety and feelings of security.28 Although these benefits may accrue predominantly to those not personally stopped, even youths who experience aggressive police contact may receive safety benefits along with any adverse effects.29 In addition, the literature on procedural justice29–31 suggests that police encounters conducted fairly and respectfully can enhance police–community relations and promote the well-being of those stopped.

Despite the heated debate on police practices,18,20,21 little is known about the health implications of involuntary contact with the police. Shedd32 suggests high rates of distress and perceptions of injustice among Chicago youths who are stopped, whereas Brunson and Weitzer15 identify feelings of “hopelessness” and being “dehumanized.” These studies paint a rich picture of aggressive policing experienced by many youths and suggest the potential for health consequences; however, these links have not been tested. Limited data are available to assess the health implications of police encounters, particularly for the urban youths at greatest risk for contact.

METHODS

We fielded a population-based survey of young men in New York City on the extent and nature of their experiences with the police and the association between these contacts and dimensions of their mental health. Between September 2012 and March 2013, we surveyed men aged 18 to 26 years, reflecting the demographic concentration of police stops in that age bracket. We selected participants using a stratified random sample dividing New York City into 146 “neighborhood clusters,” combinations of the city’s 295 neighborhoods33 that are geographically adjacent and of comparable racial/ethnic composition and median income. We stratified these clusters into deciles on the basis of the number of stops recorded in 2008 and 2009 and randomly sampled clusters within deciles.

We recruited 1261 participants from 37 clusters using a combination of random digit dialing and consumer telephone lists (including both landline and cell phone numbers) and surveyed them by telephone. When the person answering the telephone was a male resident of New York City aged 18 to 26 years, interviewers invited him to participate—interviewers asked others answering the telephone to refer a male resident aged 18 to 26 years in the household. Participants received a $25 incentive for their involvement.

The American Association for Public Opinion Research minimum response rate (i.e., the number of complete interviews divided by the total number of interviews, noninterviews, and cases of unknown eligibility34) was 32%. The American Association for Public Opinion Research minimum cooperation rate (i.e., the proportion of eligible respondents completing the survey) was 52%. The survey lasted approximately 25 minutes and asked participants about their experiences with the New York City Police Department, their perceptions of police conduct during these encounters, and their recent mental health.

Measurement

Interviewers asked participants about their experiences with the police: whether and how many times they had been stopped, where the encounters took place, and police conduct during the encounter, including whether officers asked them to show identification, frisked or searched them, used harsh or racially tinged language, or threatened or used physical force. Individuals stopped multiple times reported on their most memorable incident (their “critical encounter”). We combined these indicators into an additive scale of police intrusion (α = .68) in the respondent’s critical encounter. Police intrusion and other scale items are available as a supplement to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org. Participants also reported their perceptions of procedural justice—the procedural fairness, interpersonal respect, and ethicality with which the police exercised their authority—in their critical encounter35 and globally,36 with higher values indicating more just procedures (α = .94 and α = .83, respectively).

Respondents reported on 2 domains of mental health. Those stopped by the police completed an Impact of Event Scale–Revised, which assessed symptoms of trauma related to recent stressful events.37 The scale contains 3 subscales (intrusion, avoidance, and hyperarousal) summed to measure posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD; α = .78). In addition, all participants, with and without police experience, reported their anxiety levels using the Brief Symptom Inventory38 anxiety subscale (α = .84), with high scores indicating more distress.

Finally, because mental health outcomes are multiply determined, and many factors predicting health are also correlated with police contact, our analyses controlled for several demographic and socioeconomic covariates, including self-reported race/ethnicity, educational attainment, residence in public housing, and criminal activity, on the basis of a 5-item variety score (α = .61).39,40

Analytical Approach

We first estimated the probability that participants experienced the “treatment” of contact with the police in the year leading up to their interview as a function of their race/ethnicity, age, education, criminal participation, public housing residence, and neighborhood cluster. This model, which we call model 0, allows estimation of a predicted probability of the “treatment” of being stopped. In subsequent models we followed Bang and Robins41 by predicting mental health and controlling for the inverse probability of treatment as a proxy for selection into police contact.

We estimated all mental health models using ordinary least squares regressions with robust SEs and fixed effects for neighborhood cluster. We estimated SEs to reflect the multiple imputation. We next examined the associations between self-reported police contact and mental health. In model 1, we estimated the extent to which the number of times the police stopped respondents predicted mental health (anxiety or PTSD), controlling again for covariates (race/ethnicity, education, residence in public housing, and criminal activity) and neighborhood fixed effects as well as the selection parameter.

In model 2, we assessed the implications of both the volume of contact participants experienced and how they were treated in their critical encounter. This model replicated the first, estimating an effect of intrusive treatment in reported critical stops. In the anxiety model, which included respondents not stopped in the previous year, we identified those not stopped by a dummy variable, and they had an “intrusion” index of zero as well as their estimated selection parameter.

Finally, we assessed the role of the procedural justice context in predicting mental health, particularly whether perceived procedural justice moderated the associations between stop conduct and mental health. Model 3 replicated model 2, adding controls for perceived procedural justice in the respondents’ critical encounter and globally. Model 3 also included interactions between both measures of procedural justice and the indicator of invasive treatment.

We hypothesized that both health outcomes were linked to stop experience but that these links were largely tied to how respondents were treated in the course of stops. We expected that people reporting more intrusive critical stops would experience more mental health symptoms; however, we expected fewer symptoms among those who perceived more procedural justice in police activity. Moreover, we hypothesized that perceived procedural justice would attenuate any adverse associations between health and invasive stop activity.

Analysis Samples

We estimated each model for all respondents reporting the outcome of interest. We imputed missing data on predictor variables using the MI procedure in Stata version 12.0 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX).42 We have reported results derived from imputed data, with subsequent discussion of sensitivity to complete case analysis.

We have reported results derived from an unweighted sample, with subsequent discussion of sensitivity to a weighting strategy that reflects the oversample of high-stop neighborhoods and the mix of random digit dialing and list-based sampling.

RESULTS

Table 1 shows that consistent with the neighborhood sampling strategy, respondents were predominantly racial and ethnic minorities (80.00% non-White), young (average age = 22 years), more likely to have completed high school than are those aged 18 to 26 years citywide (87.71% vs 82.86% of those aged 18–26 years in New York City33), but less likely to have completed college (19.19% vs 24.57%33). Nearly 13.00% reported living in public housing. The measure of respondents’ self-reported criminal activity was highly skewed, with 78.00% of respondents reporting no criminal activity, and a small number of respondents (∼3.00%) reporting 3 or more types of illegal activities.

TABLE 1—

Summary Statistics of Analysis Sample of Observed Cases: Survey of Associations Between Police Contact and Mental Health, New York City, September 2012–March 2013

| Variable | Mean (SD) or % |

| Health outcomes | |

| Anxiety (BSI subscale, asked of all) | 8.53 (6.89) |

| Trauma (IES–R, asked if stopped in the past year) | 3.49 (2.58) |

| Race/ethnicity | |

| White | 20 |

| Black | 30 |

| Hispanic | 35 |

| Other or unknown | 15 |

| Respondent age, y | 22.03 (2.50) |

| Education | |

| Did not complete high school | 12 |

| High school graduate only | 31 |

| Some college or technical training | 37 |

| College graduate or more | 19 |

| Public housing residents | 13 |

| Self-reported criminal activity | 0.32 (0.75) |

| Experience with the police | |

| Ever stopped | 85 |

| Number of stops in lifetime | 8.64 (17.86) |

| Stopped past year | 46 |

| Perceived procedural justice, global | 17.84 (6.23) |

| Critical stop experience, asked if stopped in the past year | |

| Perceived procedural justice, critical encounter | 28.57 (13.40) |

| Intrusion scale | 3.43 (2.38) |

Note. BSI = Brief Symptom Inventory; IES–R = Impact of Event Scale–Revised. Percentages may not total 100 because of rounding.

Respondents reported high rates of police contact; 85% reported at least 1 police stop, and 46% reported being stopped at least once in the year they were surveyed. Like the distribution of criminal involvement, the distribution of police contact was highly skewed. Although 80% of respondents reported being stopped 10 times or fewer, more than 5% of respondents reported being stopped more than 25 times, and 1% of respondents reported more than 100 stops.

Probability of Police Contact

Individuals reporting more extensive criminal histories faced a greater probability of having been stopped (P < .001); differences in stop probability by race/ethnicity, educational attainment, and public housing residence were not statistically significant at traditional levels.

The lack of observed racial/ethnic differences in model 0 was notable because of the extreme racial/ethnic differences observed in citywide stop patterns, but it is largely explained by the control for neighborhood cluster, an association that has also been observed citywide.11

Health Outcomes

Tables 2 and 3 and Figure 1 show the associations between reported police contact and mental health. Model 1 shows that young men who reported more police contact also reported higher anxiety scores, controlling for their demographic characteristics and criminal involvement. Other observed factors were also significant predictors: respondents who reported higher levels of criminal involvement reported more anxiety, although Black and Hispanic respondents reported significantly less anxiety than did White respondents. Differences by race/ethnicity and criminal involvement were robust across models.

TABLE 2—

Estimated Predictors of Anxiety Symptoms (BSI Subscale) Ordinary Least Squares Parameter Estimates and SEs: Survey of Associations Between Police Contact and Mental Health, New York City, September 2012–March 2013

| Variable | Model 1, b (SE) | Model 2, b (SE) | Model 3, b (SE) |

| Stops | |||

| Total lifetime | 0.05** (0.02) | 0.04* (0.01) | 0.02 (0.01) |

| Any past year, yes or no | −0.96 (0.59) | 0.15 (1.44) | |

| Intrusion | 0.43*** (0.14) | 0.55 (0.28) | |

| Procedural justice | |||

| Global | −0.12* (0.05) | ||

| Critical stop | −0.01 (0.04) | ||

| Global × intrusion | −0.01 (0.02) | ||

| Critical × intrusion | −0.01 (0.01) | ||

| Selection parameter, IPT | −0.41 (0.78) | −0.34 (0.77) | −0.16 (0.77) |

| Race/ethnicity | |||

| Black | −2.05** (0.76) | −2.11** (0.76) | −2.36** (0.75) |

| Hispanic | −1.81** (0.64) | −1.84** (0.64) | −1.80** (0.62) |

| Other or unknown | −0.55 (0.79) | −0.64 (0.79) | −0.76 (0.77) |

| Education | |||

| < high school | 0.88 (0.77) | 0.77 (0.76) | 0.65 (0.74) |

| Some college or technical school | 0.16 (0.48) | 0.18 (0.64) | 0.08 (0.48) |

| College graduate | −0.89 (0.58) | −0.78 (0.76) | −0.91 (0.58) |

| Self-reported criminal activity | 1.58*** (0.47) | 1.44** (0.46) | 1.37** (0.45) |

| Public housing | 0.80 (0.77) | 0.58 (0.76) | 0.48 (0.76) |

| Neighborhood FE included, yes or no | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Number of observations per imputation | 1229 | 1229 | 1229 |

Note. BSI = Brief Symptom Inventory; FE = fixed effects; IPT = inverse probability of treatment. Analyses are derived from multiply imputed data (m = 50 imputations).

*P ≤ .05; **P ≤ .01; ***P ≤ .001.

TABLE 3—

Estimated Predictors of PTSD Symptoms (IES–R) Ordinary Least Squares Parameter Estimates and SEs: Survey of Associations Between Police Contact and Mental Health, New York City, September 2012–March 2013

| Variable | Model 1, b (SE) | Model 2, b (SE) | Model 3, b (SE) |

| Stops | |||

| Total lifetime | 0.03*** (0.01) | 0.02*** (0.01) | 0.01* (0.01) |

| Intrusion | 0.33*** (0.05) | 0.21** (0.10) | |

| Procedural justice | |||

| Global | 0.03 (0.04) | ||

| Critical stop | −0.09*** (0.02) | ||

| Global × intrusion | −0.02* (0.01) | ||

| Critical × intrusion | 0.01* (0.01) | ||

| Selection parameter, IPT | −0.27 (0.39) | 0.06 (0.36) | 0.34 (0.35) |

| Race/ethnicity | |||

| Black | 0.61 (0.38) | 0.51 (0.36) | 0.21 (0.32) |

| Hispanic | −0.08 (0.32) | −0.15 (0.31) | −0.12 (0.29) |

| Other or unknown | 0.31 (0.43) | −0.01 (0.41) | −0.26 (0.40) |

| Education | |||

| < high school | 0.35 (0.42) | 0.06 (0.41) | −0.08 (0.38) |

| Some college or technical school | 0.04 (0.26) | 0.06 (0.25) | −0.06 (0.23) |

| College graduate | 0.17 (0.31) | 0.32 (0.29) | 0.14 (0.27) |

| Self-reported criminal activity | 0.37 (0.21) | 0.36 (0.19) | 0.38* (0.18) |

| Public housing | 0.91* (0.38) | 0.73* (0.36) | 0.69* (0.32) |

| Neighborhood FE included, yes or no | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Number of observations per imputation | 547 | 547 | 547 |

Note. FE = fixed effects; IES–R = Impact of Event Scale–Revised; IPT = inverse probability of treatment; PTSD = posttraumatic stress disorder. Analyses are derived from multiply imputed data (m = 50 imputations). We measured PTSD only for respondents stopped once or more in the year leading up to the survey.

*P ≤ .05; **P ≤ .01; ***P ≤ .001.

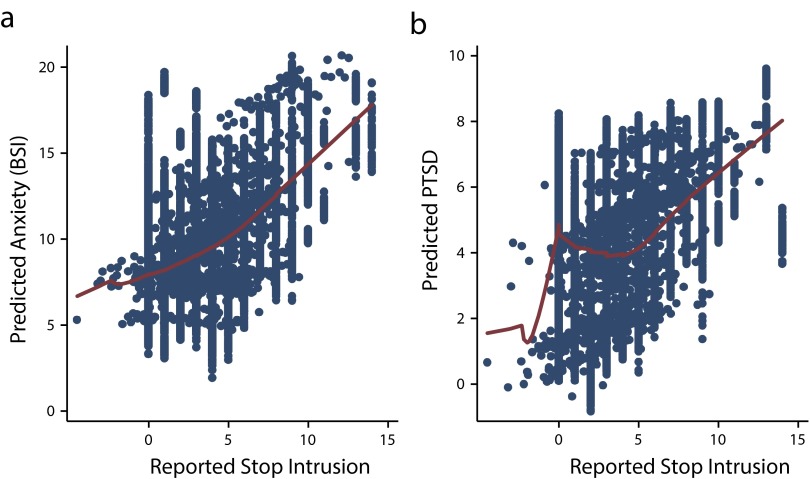

FIGURE 1—

Mental health outcomes by stop intrusion for (a) anxiety and (b) posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD): Survey of Associations Between Police Contact and Mental Health, New York City, September 2012–March 2013.

Note. BSI = Brief Symptom Inventory. Scatterplots and lowess smoothed lines are derived from predicted anxiety and PTSD symptoms as a function of stop intrusion, adjusted for race/ethnicity, education, public housing residence, criminal involvement, lifetime stop experience, and perceived procedural justice. Bandwidth = 0.8.

Model 2 shows that anxiety symptoms were significantly related to the number of times the young men were stopped and to how they perceived the critical encounter was conducted. In model 2, respondents who reported more police intrusion reported higher anxiety scores. Model 3 also suggested greater anxiety among respondents reporting more police intrusion, a relationship whose magnitude increases when considering procedural justice but that marginally loses statistical significance (P = .053). In model 3, respondents who perceived greater “global procedural justice” reported significantly less anxiety; however, procedural justice in respondents’ critical encounters was not significantly related to anxiety.

Any procedural justice attenuation of the relationship between stop intrusion and anxiety was small in magnitude and statistically insignificant (as indicated by the 2 negative interaction terms). Figure 1a presents predicted levels of anxiety as a function of stop intrusion (adjusted for the covariates and interactions of model 3) and suggests an association that grows stronger among respondents reporting more intrusive critical encounters.

Table 3 presents estimates from models predicting PTSD (e.g., the Impact of Event Scale–Revised) associated with respondents’ critical encounters with the police. Model 1 indicated more trauma symptoms among respondents reporting more lifetime stops. In this model, trauma levels were also significantly higher among public housing residents. The significance of these relationships was robust to a control for stop intrusion, presented in model 2, although their magnitudes were attenuated. In model 2, stop intrusion was a significant predictor of PTSD, with more invasive stops predicting higher levels of trauma.

Model 3, which also considered the role of procedural justice, suggests that the stop intrusion remained a statistically significant predictor of PTSD but lost more than one third of its magnitude. Perceived procedural justice in respondents’ critical encounters (although not global procedural justice) was inversely related to trauma: young men who reported fair treatment in these encounters reported fewer PTSD symptoms. As with the anxiety models, the extent to which procedural justice moderated the association between stop intrusion and related trauma was relatively small.

Although statistically significant, the interaction effects of global and critical stop procedural justice were in offsetting directions. As shown in Figure 1b, the association between stop intrusion and predicted PTSD is particularly strong at high levels of intrusion (> 5 of 14).

DISCUSSION

Although proactive policing practices target high-crime, disadvantaged neighborhoods, affecting individuals already facing severe socioeconomic disadvantage, our findings suggest that young men stopped by the police face a parallel but hidden disadvantage: compromised mental health. We found that young men reporting police contact, particularly more intrusive contact, also display higher levels of anxiety and trauma associated with their experiences. Although respondents perceiving greater procedural justice from the police report fewer symptoms, stop intrusion remains tied to mental health (marginally in the case of anxiety and significantly in the case of PTSD).

Observed health implications are strongest in the most intrusive encounters; this can be seen most clearly in Figure 1b, in which predicted PTSD symptoms rise sharply at intrusion levels of 5 or more. Notably, the skewed distribution of stop intrusion suggests that this association is driven by the 25% of respondents recently stopped who report intrusion in this range. Although this represents a minority of our sample (10% overall), the group is nonnegligible; that so many respondents reported police intrusion levels predictive of PTSD symptoms is troubling.

The associations between reported stop experience and mental health were robust to missing data analysis strategy, with findings substantively similar in both the multiply imputed and complete case samples. However, in the complete case sample, the relationship between respondent perceptions of global procedural justice and anxiety, statistically significant in the imputed models, was stronger in magnitude but lost statistical significance. In addition, in the PTSD model considering stop conduct in the context of procedural justice, the number of total stops respondents reported experiencing was statistically insignificant in the complete case estimate (although similar in magnitude to the imputed estimate).

We note sensitivity to sample weighting through several small differences in our weighted and unweighted model results. The association between anxiety and stop intrusion in model 2 was only marginally significant in the weighted sample (although the magnitude remained comparable). In both samples, the association increased in magnitude but lost further significance in model 3, considering the context of procedural justice. In both samples, respondents perceiving greater global procedural justice (but not critical stop procedural justice) reported reduced anxiety symptoms; procedural justice was also associated with a slight but insignificant reduction of the link between anxiety and intrusion.

Examining PTSD in the weighted sample, findings also diverged slightly—in models 1 and 2 the selection parameter was much larger in magnitude and at least marginally significant, suggesting that respondents at greatest risk for being stopped at least once were also at the greatest risk for PTSD from these stops. Finally, race/ethnicity coefficients were larger and statistically significant in the weighted sample, suggesting higher PTSD prevalence among Black respondents.

It is notable, however, that despite these differences, the substantive associations between respondents’ experiences with the police and their mental health were strong and largely robust across samples and models—particularly among respondents reporting stops carried out in an intrusive fashion. This raises concerns that the aggressive nature of proactive policing may have implications not only for police–community relations but also for local public health. In fact, the significant associations between both health outcomes and respondent perceptions of procedural justice suggest that police–community relations and local public health are inextricably linked.

Limitations

Our analysis, particularly our collection of population-based data, represents significant progress toward understanding the implications of policing for population health. However, our findings must be interpreted with caution. First, our conclusions are limited by the cross-sectional nature of our data, and we make no causal claims. In fact, causal direction is uncertain. For example, it is possible that men’s mental health influenced their perceptions of their interactions and that those facing the greatest anxiety and stress tended to exaggerate their experiences.

Likewise, respondents displaying mental health symptoms might have attracted greater reasonable suspicion or responded to police questioning in ways that escalated their situations. The statistically significant relationships between anxiety, criminal involvement, and stop experience further underscore the complexity of relationships linking police activity and its correlates. However, the strong associations between police conduct and population health raise serious concerns about potential unintended consequences of police activity, suggesting a need for longitudinal research disentangling the causal nature of these associations.

Our conclusions are also circumscribed by somewhat low reliability of 2 key measures (police intrusion and criminal activity, α = .68 and .61, respectively) and challenges in sampling young urban men, generally understood to be a hard-to-reach population. Although our population-based sampling procedures are innovative, our cooperation rate of 52% suggests that many young men eligible for our survey declined to participate. Although this is to be expected because of the sensitive nature of police contact, our respondents reported significantly more contact with the police than expected in a random sample of young men in New York City.

We observed higher than average contact rates across races/ethnicities, with and without weighting to reflect the oversampling of high-stop neighborhoods. It is likely that young men without police experience had less interest in the study and were less likely to participate, and our participants’ stop experiences therefore cannot be assumed to generalize citywide. Nonetheless, the links between police intrusion and mental health, observed in a population-based sample reporting high rates of contact, raise public health concerns for the individuals and communities most aggressively targeted by the police.

Implications

The contentious policy debate around stop and frisk in New York City has largely focused on whether aggressive police scrutiny is a justifiable approach to crime detection and deterrence20,21—or whether disparities in offending justify racial/ethnic disparities in policing.16,43 Another debate focuses on the constitutionality of stop and frisk tactics with respect to racial/ethnic discrimination11,17 and suspicionless stops and searches.11 Notwithstanding the dearth of evidence to justify a crime-control claim, and the constitutional concerns these arguments raise, our findings suggest that any benefits achieved by aggressive proactive policing tactics may be offset by serious costs to individual and community health.

Although more work is needed to fully understand these associations, our findings are consistent with a growing literature identifying criminal justice practices as a threat to physical and mental health. Moreover, our findings suggest that these risks are not limited to individuals formally processed through an arrest or incarceration. Rather, the low levels of contact that many urban residents face on a regular basis—without formal sanctions—risk serious adverse consequences.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the Public Health Law Research Program of the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (grant 69669) and the National Institute of Justice (grant 2010-IJ-CX-0025). Additional support was provided by the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (award R24HD058486).

Chintan Turakhia, Dean Williams, Marci Schalk, and Courtney Kennedy at Abt SRBI led outstanding survey operations. Julien Teitler provided important support in the early stages of the research. Chelsea Davis provided invaluable research assistance.

Human Participant Protection

The institutional review boards at Columbia University, Yale University, and SRBI approved this study.

References

- 1.Golembeski C, Fullilove R. Criminal (in)justice in the city and its associated health consequences. Am J Public Health. 2005;95(10):1701–1706. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.063768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Johnson RC, Raphael S. The effects of male incarceration dynamics on acquired immune deficiency syndrome infection rates among African American women and men. J Law Econ. 2009;52(2):251–293. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Western B. Punishment and Inequality in America. New York, NY: Russell Sage Foundation; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brame R, Turner MG, Paternoster R, Bushway SD. Cumulative prevalence of arrest from ages 8 to 23 in a national sample. Pediatrics. 2012;129(1):21–27. doi: 10.1542/peds.2010-3710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kubrin CE, Messner SF, Deanne G, McGeever K, Stucky TD. Proactive policing and robbery rates across US cities. Criminology. 2010;48(1):57–97. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Terry v. Ohio, 392 U.S. 1 (1968)

- 7. Fagan J. Second supplemental report of plaintiff’s expert Jeffrey Fagan. Floyd et al. v. City of New York, et al. 08 Civ. 1034, SAS (2012)

- 8. Bailey et al. v. City of Philadelphia, et al. Complaint. Civ. 05952 (2010)

- 9.Ayres I, Borowsky J. A Study of Racially Disparate Outcomes in the Los Angeles Police Department. American Civil Liberties Union. Los Angeles, CA: American Civil Liberties Union of Southern California; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hagan J, Shedd C, Payne MR. Race, ethnicity, and youth perceptions of criminal injustice. Am Sociol Rev. 2005;70(3):381–407. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Fagan J. Expert testimony. Floyd et al. v. City of New York, et al. 08 Civ. 1034, SAS (2010)

- 12.Fagan J, Geller A, Davies G, West V. Street stops and broken windows revisited: the demography and logic of proactive policing in a safe and changing city. In: Rice SK, White MD, editors. Race, Ethnicity, and Policing: New and Essential Readings. New York, NY: New York University Press; 2010. pp. 309–348. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Geller A, Fagan J. Pot as pretext: marijuana, race, and the new disorder in New York City street policing. J Empirical Legal Stud. 2010;7(4):591–633. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brunson RK. “Police don’t like Black people”: African-American young men’s accumulated police experiences. Criminol Public Policy. 2007;6(1):71–102. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brunson RK, Weitzer R. Police relations with Black and White youths in different urban neighborhoods. Urban Aff Rev. 2009;44(6):858–885. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ridgeway G. Analysis of Racial Disparities in the New York Police Department’s Stop, Question, and Frisk Practices. Santa Monica, CA: RAND; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Smith DC. Report of Dennis C. Smith. David Floyd et al. v. City of New York, et al. (2010)

- 18. Rivera R. Police-stop data shows pockets where force is used more often. New York Times. August 15, 2012; A17.

- 19. Rivera R, Baker A, Roberts J. A few blocks, 4 years, 52,000 police stops. New York Times. July 12, 2010; A1.

- 20.MacDonald H. To see its value, see how crime rose elsewhere. 2013. Available at: http://www.nytimes.com/roomfordebate/2012/07/17/does-stop-and-frisk-reduce-crime/to-see-its-value-see-how-crime-rose-elsewhere. Accessed February 13, 2014.

- 21.Williams V, Fromer E, Fagbenle T, Stein C. The effect of stop and frisk in the Bronx. 2012. Available at: http://www.wnyc.org/story/232447-radio-rookies-kelly. Accessed February 13, 2014.

- 22.Fratello J, Rengifo AF, Trone J. Coming of Age With Stop and Frisk: Experiences, Self-Perceptions, and Public Safety Implications. New York, NY: Vera Institute of Justice; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Levine HG, Small DP. Marijuana Arrest Crusade: Racial Bias and Police Policy in New York City, 1997–2007. New York, NY: New York Civil Liberties Union; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Herbert B. Watching certain people. New York Times. March 2, 2010; A23.

- 25.Link BG, Phelan JC. Conceptualizing stigma. Annu Rev Sociol. 2001;27:363–385. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Freeman Anderson K. Diagnosing discrimination: stress from perceived racism and the mental and physical health effects. Sociol Inq. 2013;83(1):55–81. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sawyer PJ, Major B, Casad BJ, Townsend SSM, Berry Mendes W. Discrimination and the stress response: psychological and physiological consequences of anticipating prejudice in interethnic interactions. Am J Public Health. 2012;102(5):1020–1026. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Powell M. For New York police, there’s no end to the stops. New York Times. May 15, 2012; A20.

- 29.Fagan J, Tyler TR. Legal socialization of children and adolescents. Soc Justice Res. 2005;18(3):217–242. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tyler TR. Procedural justice, legitimacy, and the effective rule of law. Crime and Justice. 2003;30:431–505. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tyler TR. Enhancing police legitimacy. Ann Amer Acad Polit Soc Sci. 2004;593(1):84–99. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Shedd C. Arresting development: race, place, and the end of adolescence. Presented at Feminism Legal Theory Workshop; February 20, 2012; Columbia Law School, New York, NY.

- 33.Community Studies of New York. Guide to Infoshare online. 2007. Available at: http://www.infoshare.org/main/userguide.aspx. Accessed June 20, 2014.

- 34.Standard Definitions: Final Dispositions of Case Codes and Outcome Rates for Surveys. 7th ed. Deerfield, IL: American Association for Public Opinion Research; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tyler TR, Fagan J. Legitimacy and cooperation: why do people help the police fight crime in their communities? Ohio St. J. Crim. L. 2008;6(1):173–229. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sunshine J, Tyler TR. The role of procedural justice and legitimacy in shaping public support for policing. Law Soc Rev. 2003;37(3):513–547. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Weiss DS. The Impact of Event Scale–Revised. In: Wilson JP, Keane TM, editors. Assessing Psychological Trauma and PTSD: A Practitioner’s Handbook. 2nd ed. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Derogatis L, Melisaratos N. The Brief Symptom Inventory: an introductory report. Psychol Med. 1983;13(3):595–605. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Knight GP, Little M, Losoya SH, Mulvey EP. The self-report of offending among serious juvenile offenders: cross-gender, cross-ethnic/race measurement equivalence. Youth Violence Juv Justice. 2004;2(3):273–295. doi: 10.1177/1541204004265878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Thornberry TP, Krohn MD. The self-report method for measuring delinquency and crime. In: Duffee D, Crutchfield RD, Mastrofski S, Mazerolle L, McDowall D, Ostrom B, editors. CJ 2000: Innovations in Measurement and Analysis. Vol. 4. Washington, DC: National Institute of Justice; 2000:33–83. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bang H, Robins JM. Doubly robust estimation in missing data and causal inference models. Biometrics. 2005;61(4):962–973. doi: 10.1111/j.1541-0420.2005.00377.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.University of Wisconsin Social Science Computing Cooperative. Multiple imputation in Stata. 2012. Available at: http://www.ssc.wisc.edu/sscc/pubs/stata_mi_intro.htm. Accessed January 24, 2014.

- 43. Fermino J. Mayor Bloomberg on stop-and-frisk: It can be argued “We disproportionately stop Whites too much. And minorities too little.” New York Daily News. June 28, 2013.