Abstract

Objectives. We explored service variation among local health departments (LHDs) nationally to allow systematic characterization of LHDs by patterns in the constellation of services they deliver.

Methods. We conducted latent class analysis by using categorical variables derived from LHD service data collected in 2008 for the National Profile of Local Health Departments Survey and before service changes resulting from the national financial crisis.

Results. A 3-class solution produced the best fit for this data set of 2294 LHDs. The 3 configurations of LHD services depicted an interrelated set of narrow or limited service provision (limited), a comprehensive (core) set of key services provided, and a third class of core and expanded services (core plus), which often included rare services. The classes demonstrated high geographic variability and were weakly associated with expenditure quintile and urban or rural location.

Conclusions. This empirically derived view of how LHDs organize their array of services is a unique approach to categorizing LHDs, providing an important tool for research and a gauge to monitor how changes in LHD service patterns occur.

Nationwide shifts in public health practice in recent decades, including recent responses to economic decline,1–6 have moved many local health departments (LHDs) away from providing intensive, individually focused, personal health services and toward the transfer of public health investments into more population-focused domains of practice such as assessment, planning, and population-based primary prevention.2,4 Wide variation in the breadth and scale of services provided by LHDs nonetheless persists.5,7,8 This variation has been attributed to differences of perspective in the primary “role” of governmental public health agencies,9 the complex sources of categorical funding that often drive the array of local services delivered,7 varied legal statutes and policies,10 and assessments of local need along with the availability of community resources.7

Evidence suggests that LHD investments overall11 and in relation to specific services12 have a beneficial relationship to population health outcomes. It may also be the comprehensive and interactive nature of a specific constellation of LHD services that most effectively contributes to healthy outcomes in a community.8,13 For example, a related mix of individually focused services for women and children (e.g., the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children; family planning; and maternal and child home visits) may be most effective for families when provided together as a package by the LHD. An LHD that couples these maternal and child services with an active assessment and surveillance system that helps prioritize services among those populations for whom poor birth outcomes are particularly high may achieve even better results. The constellation of services, therefore, may be more important to the performance of an LHD in promoting health improvement than the delivery of various individual services in isolation. No apparent studies, however, have classified LHDs themselves in terms of their constellation of services provided.

Recent studies in public health systems and services research have made advancements in establishing a typology of the systems delivering local public health services.14 Using data collected in 1998 and 2006, Mays et al. developed this typology, measuring interorganizational network structures and identifying 7 local public health system configurations that include the scope of activities provided by LHDs and by other organizations in their jurisdictions.14 The urban systems they have tracked over time appear “highly adaptable” and “dynamic,” suggesting opportunities for modifying complex public health system features to improve performance.14(p103)

As central figures in these local systems, LHDs play a critical role in ensuring adequate public health service delivery. Yet little is known about how their own services tend to be organized and how their constellations of services can be adapting to change. Identifying underlying patterns in these constellations with routinely collected, national data would provide a means to monitor the adaptations of LHDs themselves and to examine how these service constellations are related to local conditions and health outcomes. We describe a major step in exploring service variation among LHDs nationally to characterize LHDs by patterns in the constellation of services they deliver.

METHODS

This study was based on survey items from the 2008 wave of the National Profile of Local Health Departments Study Series (hereafter referred to as the Profile) conducted by the National Association of County and City Health Officials (NACCHO).15 The Profile was conducted 7 times from 1989 to 2013,15 and we used the 2008 Profile in this analysis. We chose to use LHD activities from the 2008 Profile because they represented services provided in 2007, thereby depicting LHD service arrangements not yet affected by the 2008 national budget crisis, which arguably might have uniquely restricted or altered variation in the 2010 Profile data because of recession-driven budget cuts.6 Data more distal from the 2008 recession and collected in 2013 were not available at the time of this analysis.

Survey Response

The 2008 Profile had a survey response rate of 83%, representing 2332 of the nation’s 2794 total LHDs at that time. Responses to 86 questions from the 2008 Profile’s “activities” section describe services provided by each LHD in 2007.16 The 86 service activity Profile questions were grouped by NACCHO into 11 domains such as screening for diseases or conditions, maternal and child health, epidemiology and surveillance activities, and population-based primary prevention activities. Response choices for each service related to what agency (e.g., the LHD or some other local agency) performed a specific activity or service or if that service was not available in that jurisdiction.

Among the 86 service activity items in the 2008 Profile, 42 reflected what are generally considered personal and population health activities. An LHD’s personal health services are often individually focused and serve, for example, a person or family with a specific health risk with maternal and child health services or diagnostic screening and treatment of communicable disease.17 Population health activities are those focused on the aggregate level and intended to detect or prevent disease and disability on a large scale through, for example, disease surveillance or health promotion campaigns. The remaining 44 Profile service items focused largely on the environmental health activities of LHDs, which were included by NACCHO under activity domains such as regulation and inspection.17 In discussing patterns of service provision with public health practice partners, practitioners indicated that decisions made in practice settings about an agency’s environmental health services tend to be made separately from decisions about other public health services because of issues such as the legislative mandates and the fee-based funding structures specific to environmental health. On the basis of this information and the study goal of identifying interpretable patterns in LHD service approaches, we excluded the 44 environmental health services. We also excluded 38 LHDs because they provided only environmental health services, leaving 2294 LHDs in the final data set.

We then conducted further variable reduction before examining service data for underlying latent classes, by working with an expert panel of 5 experienced researchers familiar with public health systems and NACCHO Profile services data. These researchers provided feedback and review in the sorting and validation of the 42 items into a natural depiction of how services might be conceptually grouped in practice. Finally, the study team engaged 5 more public health practice partners to examine and validate the categories derived (see the box on this page).

Grouping of 42 Service Items Into 6 General Service Categories: 2008 National Association of County and City Health Officials’ US National Profile of Local Health Departments

| Individual-focused | Population-focused |

| Basic | Basic |

| Adult immunizations (Imm) | Blood lead (Scrng) |

| Child immunizations (Imm) | Communicable or infectious disease (Epi) |

| EPSDT (MCH) | HIV/AIDS (Scrng) |

| Family planning (MCH) | Nutrition (Pop) |

| MCH home visits (MCH) | Other STDs (Scrng) |

| WIC (MCH) | Tuberculosis (Scrng) |

| Expanded | Tuberculosis (Tx) |

| Cancer (Scrng) | Tobacco (Pop) |

| Cardiovascular disease (Scrng) | Unintended pregnancy (Pop) |

| Diabetes (Scrng) | Expanded |

| High blood pressure (Scrng) | Behavioral risk factors (Epi) |

| Home health care (Other HS) | Chronic disease programs (Pop) |

| Oral health (Other HS) | Maternal and child health (Epi) |

| Prenatal care (MCH) | Physical activity (Pop) |

| Primary care (Other HS) | STDs (Tx) |

| School health (Other) | Specialized |

| Well-child clinic (MCH) | Chronic disease (Epi) |

| Specialized | Injury (Epi) |

| Behavioral or mental (Other HS) | Injury (Pop) |

| HIV/AIDS (Tx) | Mental illness (Pop) |

| Obstetrical care (MCH) | Substance abuse (Pop) |

| School-based clinics (Other) | Syndromic surveillance (Epi) |

| Substance abuse (Other HS) | Violence (Pop) |

Note. Epi = epidemiology and surveillance; EPSDT = early periodic screening, diagnosis, and treatment; Imm = immunization; MCH = maternal and child health; Pop = population-based primary prevention; Other = other activities; Other HS = other health services; Scrng = screening for diseases or conditions; STDs = sexually transmitted diseases; Tx = treatment of communicable diseases; WIC = Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children.

The 6 service categories that emerged grouped services by the level at which service was focused (population or individual) and then subdivided each service by how commonly it was provided. We considered each of the 42 services to be provided by the LHD if either of the choices “performed by LHD directly” or “contracted out by LHD” were chosen. Otherwise, we considered the service to not be provided by the LHD. With this definition of service provision, we produced a total count of services for each of the 6 service categories for every LHD. On the basis of the proportion of services provided in each category, we created an ordinal variable of low, medium, or high service provision range, for use in the subsequent latent class analysis (LCA). We used a measure of “low provision” to indicate when no services or less than one third of the services in a category were provided, “medium provision” when one third to two thirds of the services were provided, and “high provision” when more than two thirds of the services in a category were provided. Table 1 indicates the proportion of LHDs that provided a low, medium, or high number of the services for each of the 6 service category variables.

TABLE 1—

Percentage Distribution of Local Health Departments Providing a Low, Medium, or High Number of the Services for Each of the 6 Service Category Variables Used in the Latent Class Analysis: 2008 National Association of County and City Health Officials’ US National Profile of Local Health Departments

| % Distribution LHDs |

|||

| Services | Low No. of Services | Medium No. of Services | High No. of Services |

| Individual-focused | |||

| Basic | 19 | 29 | 52 |

| Expanded | 48 | 33 | 19 |

| Specialized | 79 | 19 | 2 |

| Population-focused | |||

| Basic | 11 | 21 | 68 |

| Expanded | 28 | 37 | 35 |

| Specialized | 64 | 23 | 13 |

Note. LHD = local health department

We examined the distribution of variables and found them to meet study team expectations of what would be typical of a national sample of LHDs. A small minority (11%) of LHDs, for example, provided or contracted out only very few in the range of common population-focused basic services (Table 1). Slightly more (21%) provided or contracted out a medium range of these services and a strong majority (68%) provided or contracted out a high range of these common LHD services that are often considered a critical component of most LHD structures.2 Similarly, a majority of LHDs (64%) provided or contracted out only a low range of the more rare population-focused specialized services and only a small minority (13%) provided a high range of these relatively rare services.

Approach

Latent class analysis is an analytic method for grouping heterogeneous items into distinct subgroups.18 The unit of analysis for this study was the response pattern to the indicator variables by LHD respondents to the 2008 Profile, which in this case were the 6 service category variables. Latent class analysis assumes there is a single, categorical latent variable that explains the heterogeneity across individual response patterns to the indicator variables, meaning that the response patterns to, or associations among, the 6 service variables of LHDs would be explained by their belonging to the same underlying class.18 In this study, the latent variable would be the approach to service provision for an LHD.

We conducted an LCA in 2013 by using the poLCA package in R version 3.1.0 (R Foundation, Vienna, Austria, 2011) with the 6 service variables derived from the expert review. We fit models with 1 to 5 classes. We chose the 3-class over the 1-, 2-, 4-, and 5-class models. The likelihood ratio test and χ2 model test were significant for all but the 5-class solution, which was expected because these tests tend to be conservative with large sample sizes and difficult to reject.19 When we used Akaike information criteria, both the 3- and 4-class solution fit similarly well. A comparison of the average posterior probabilities for each class, however, indicated that the 3-class fit was better, as each of the 3 classes had an average posterior probability of at least 0.9 and the lowest 4-class average posterior probabilities were 0.79 and 0.82. We used the Pearson χ2 test for independence and multinomial logistic regression to test final class assignments for independence with the LHD’s region, per capita LHD expenditure quintile, and whether it was in a rural, micropolitan, or metropolitan area.

We conducted a sensitivity analysis to determine whether placing service items into different groupings affected the LCA results. This analysis involved moving child immunizations and adult immunizations from the individual-focused basic grouping to the population-focused grouping. More than 90% of LHDs in the 2008 Profile offered each of these services and the placement of these 2 services as individual- or population-focused had been debated by experts in the initial reduction. The 3-class solution was robust to this check, with the 3 classes performing similarly across the 6 variables and with similar membership.

RESULTS

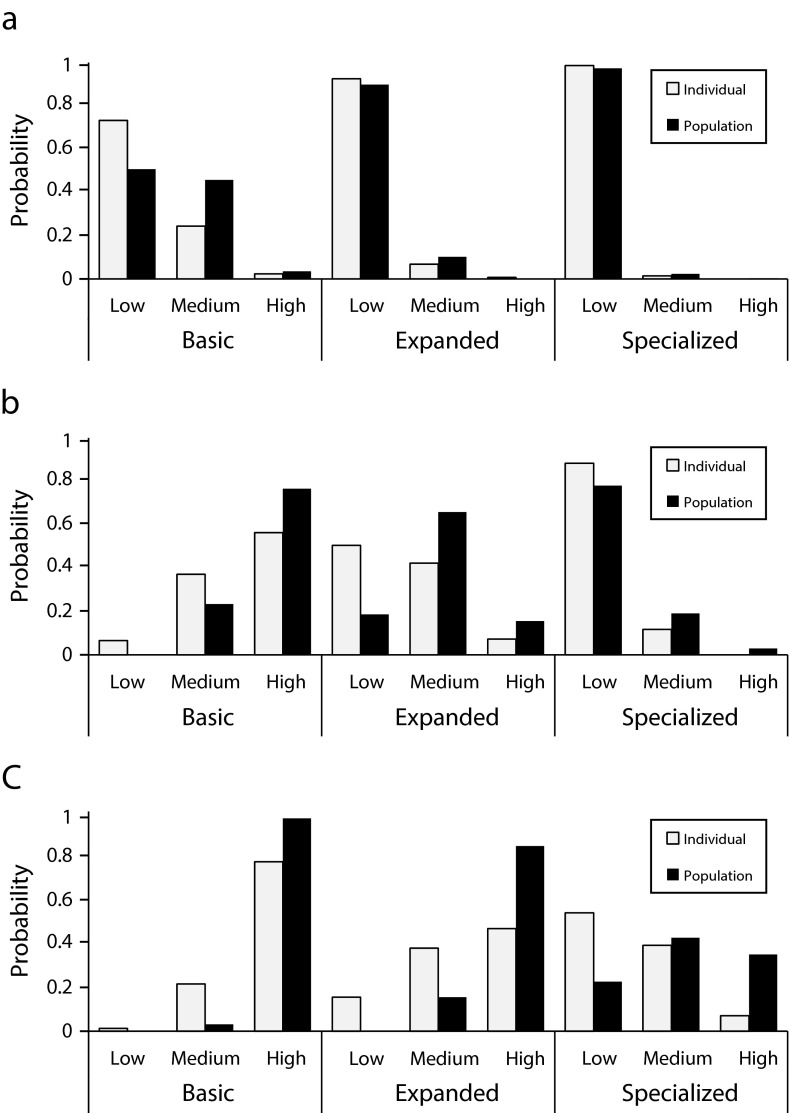

The resulting limited, core, and core-plus classes, derived from the LCA, suggest 3 different approaches to service provision that commonly depicted public health service delivery in 2007 among LHD respondents to the 2008 Profile. The names we gave to these classes represent an examination of the variable structure of each category described in the next paragraphs and depicted in Figure 1.

FIGURE 1—

Probabilities that a low, medium, or high range of service provision in each service category (individual or population-focused and basic, expanded, or specialized) is offered by each of the 3 local health department classes (a) limited, (b) core, and (c) core plus: 2008 National Association of County and City Health Officials’ US National Profile of Local Health Departments.

The LHDs in the limited class were low providers in terms of the range of expanded or specialized categories of services. These LHDs were either low- or medium-range providers of basic services, but were unlikely to be high-range providers of basic services. The LHDs in the limited class were likely to be providing more of the population-focused basic services (0.46 probability of providing a medium range of these services) than individual-focused basic services (0.24 probability of a medium range).

The LHDs in the core class were more likely to provide a high range of basic services and more likely to provide services in the expanded category than LHDs in the limited class. The LHDs in the core class were likely to provide a medium range of population-focused expanded services (0.66) whereas the probabilities of providing either a low (0.50) or a medium (0.42) range of expanded individual services were very similar. Like the limited class LHDs, core class LHDs tended to provide a very low range of specialized services.

The LHDs in the core-plus class were very likely to provide a high range of basic population-focused services (0.97) and were very likely to also provide a high range of basic individual-focused services (0.77). Core-plus class LHDs were also very likely providers of a high range of expanded population-level services (0.84), and rather similarly likely to provide a medium (0.38) or high (0.47) range of expanded individual-focused services. Of all the classes, these LHDs provided the greatest range of specialized individual- and population-focused services.

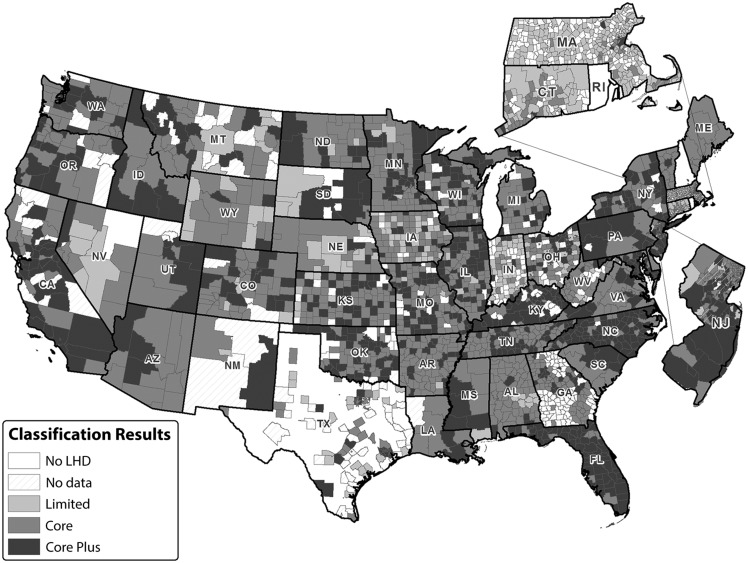

The spatial distribution of these classes, when mapped, displayed a high level of geographic variability (Figure 2). Patterns were evident within both states and regions of the country. Some states demonstrated a high degree of homogeneity among the classes of their LHDs. Florida, for example, had almost exclusively core-plus class LHDs and did not have any LHDs that fit the limited class, whereas Maine was entirely composed of core class LHDs. Many states had a mix of core and core-plus class LHDs, and others had at least some LHDs in each class. Some states, such as Iowa and Ohio, demonstrated a particularly high degree of geographic variability, displaying an almost checkerboard-like mix of all the classes. Certain regions such as the Northwest contained states (Washington, Oregon, and Idaho) that showed similar patterns of core-plus class LHDs in urban areas and core class LHDs in less-urban parts of the state. In simple multinomial logistic regression (not shown) state effects were not consistently significant, whereas regional effects on LHD class assignment were significant (P < .01) for most HHS regions.

FIGURE 2—

Results of latent class analysis of local health department service provision from 2008 National Association of County and City Health Officials’ US National Profile of Local Health Departments, mapped to 2008 local health department jurisdictional boundaries.

Note. LHD = local health department.

Simple multinomial logistic regressions (not shown) indicated that being in a metropolitan area increased the probability that an LHD was in the limited class, with micropolitan and rural LHDs having higher probabilities than metropolitan LHDs of being in the core class and core-plus class (P < .01). When we used simple multinomial logistic regression to explore this relationship, being in the limited class was much more common in the lowest quintiles of per capita expenditures, and LHDs in higher per capita quintiles were more likely to be in either core or core-plus classes (P < .01).

DISCUSSION

Despite the tremendous variation in service delivery across LHDs in the United States,7 the 2294 LHDs in this study sorted into 3 distinct classes on the basis of the constellation of individual- and population-focused services they delivered in 2007. These results correspond to the consistent “patterns of variation,” found by Mays et al., in the clustering of local public health systems around 7 system configurations depicting LHDs’ scope of service and engagement with local organizations.14 Mays’ typology, developed among LHDs with large (> 100 000 residents) jurisdictions, was found, like the results presented here, to contrast with long-held notions of LHDs being distinctly different from each other.14

The constellations of services found here may reflect patterns of service arrangements in response to local policy, existing community services, or other underlying adaptations. The patterns within each class demonstrated a complex constellation of service that does not suggest any one class is preferable or even that a class of LHDs was largely population-focused. Instead, the LHDs showed underlying patterns of more narrowly focused or more comprehensive services that cut across orientations toward individuals or populations, indicating that these services were not provided independently but, rather, that an LHD’s service offerings were very interrelated.

Within many states only a subset of the 3 classes was present, indicating that both within-state and between-state or regional factors influenced LHD service provision variability (Figure 2). Although class membership was associated with per capita expenditure and jurisdiction rurality, these relationships were inadequate for predicting class membership for LHDs or explaining the majority of class variability, indicating that the latent classes were capturing unique information beyond what could be explained with LHD expenditures and rurality.

Mays’ study classified LHDs with a particular focus on public health delivery systems in the community. The narrow focus of the classes described here provides both a means to classify the activities of LHDs themselves by their approach to a constellation of services delivered and to create these classifications with a regular and readily available source of national LHD census data, representing a range of LHD jurisdiction sizes. Since 2005, the NACCHO Profile has had an average response rate of 81.7% and has been fielded every 2 to 3 years with public health service items emerging as a rich research resource.8,20,21 The availability of later Profile surveys suggests that these classes developed with the 2008 Profile can serve to demonstrate the utility of the approach and to provide a baseline for examination of changes to and variation in these service approaches that occur over time and in response to local conditions and the general shock of and recovery from the national recession. Mays et al. found a “high degree of structural fluidity” in configuration type across waves of survey data they collected.14(p100) Researchers can, therefore, expect that the classes presented here would also display change over time and support rigorous research for public health policy and practice. Our approach with latent class models in this context can be extended to both capturing this cross-sectional variation as we did here, as well as allowing for a dynamic formulation of classes over time (depicting how service constellations may change in number and content) and for capturing how any given LHD may transition to another set of classes or remain stable.

Limitations

We examined service constellations in terms of their scope, but data limitations precluded any measure of scale of service. An LHD depicted as core-plus could, therefore, be carrying out a small amount of activity in a wide array of service areas. Breadth of service, however, may reflect local mandates or could be an adaptive feature related to responding to local need.

Other data limitations exist in terms of the self-reported nature of the Profile survey. We intended the data reduction and LCA approach used to minimize related data irregularities. The LHDs classified in this study also only depict LHDs at 1 point in time (largely prerecession) in terms of their personal- and population-health service delivery. In this manner the results do not depict current service constellations, but do indicate the general value of the analytical approach and provide a prerecession baseline for later comparisons. Our approach also regretfully left out any classifying structure for environmental health.

Conclusions

Despite tremendous variation in local public health practice, underlying patterns appear to exist in the constellation of services LHDs provide. These patterns cut across individual- and population-focused areas of practice and suggest that services are predictably interrelated. The empirically derived patterns identified suggest that readily available and routinely gathered national data depicting characteristics of each of the nation’s LHDs can be used to monitor LHD patterns over time and may be an important means of comparative analysis, while taking changes to the Profile survey into account. How we derived these classes of LHD service delivery will also allow for a dynamic approach to classification (e.g., the number and content of classes may not be stable over time) and for observing change (or basic stability) in different service delivery patterns among our nation’s LHDs. The need for such a means to monitor these changes and its variation is particularly important at this time, with tremendous national changes under way in public health system delivery in relation to the financial crisis, recovery, and rapidly changing local policy conditions.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by The Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Nurse Faculty Scholars Program (grant 68042) and program for Public Health Practice-Based Research Networks (grant 69688).

Human Participant Protection

No human participants were included in this study so no institutional review board review was necessary.

References

- 1.National Association of County and City Health Officials. Local health department job losses and program cuts: findings from the 2013 profile study. 2013. Available at: http://www.naccho.org/topics/infrastructure/lhdbudget/upload/Survey-Findings-Brief-8-13-13-3.pdf. Accessed January 20, 2014.

- 2.Frieden TR. Asleep at the switch: local public health programs and chronic disease. Am J Public Health. 2004;94(12):2059–2061. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.12.2059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Policy and Environmental Change: New Directions for Public Health. Final Report. Atlanta, GA: Association of State and Territorial Directors of Health Promotion and Public Health Education and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (US); 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 4.National Association of County and City Health Officials. Changes in local health department services and activities: longitudinal analysis of 2008 and 2010 profile data. 2012. Available at: http://www.naccho.org/topics/infrastructure/profile/resources/upload/ResearchBrief-Activities-final_01-25-2012.pdf. Accessed December 5, 2013.

- 5.Erwin PC. The performance of local health departments: a review of the literature. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2008;14(2):E9–E18. doi: 10.1097/01.PHH.0000311903.34067.89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bekemeier B, Chen A, Kawakyu N, Yang YR. Local public health resource allocation: limited choices and strategic decisions. Am J Prev Med. 2013;45(6):769–775. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2013.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Institute of Medicine. For the Public’s Health: Investing in a Healthier Future. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2012. Available at: http://www.iom.edu/Reports/2012/For-the-Publics-Health-Investing-in-a-Healthier-Future.aspx. Accessed December 5, 2013. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bekemeier B, Grembowski D, Yang YR, Herting JR. Are local public health department services related to racial disparities in mortality? SAGE Open. 2014;4(1):1–10. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Keane C, Marx J, Ricci E. Local health departments’ mission to the uninsured. J Public Health Policy. 2003;24(2):130–149. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Institute of Medicine. For the Public’s Health: Revitalizing Law and Policy to Meet New Challenges. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mays GP, Smith SA. Evidence links increases in public health spending to declines in preventable deaths. Health Aff (Millwood) 2011;30(8):1585–1593. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2011.0196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bekemeier B, Yang YR, Dunbar M, Pantazis A, Grembowski D. Targeted health department expenditures benefit birth outcomes at the county level. Am J Prev Med. 2014;44(6):569–577. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2014.01.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ingram RC, Scutchfield FD, Mays GP, Bhandari MW. The economic, institutional, and political determinants of public health delivery system structures. Public Health Rep. 2012;127(2):208–215. doi: 10.1177/003335491212700210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mays GP, Scutchfield FD, Bhandari MW, Smith SA. Understanding the organization of public health delivery systems: an empirical typology. Milbank Q. 2010;88(1):81–111. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0009.2010.00590.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.National Association of County and City Health Officials. National profile of local health departments study series. 2013. Available at: http://www.naccho.org/topics/infrastructure/profile. Accessed January 20, 2014.

- 16.National Association of County and City Health Officials. Profile study: data requests and technical documentation. 2013. Available at: http://www.naccho.org/topics/infrastructure/profile/techdoc.cfm. Accessed January 20, 2014.

- 17.National Association of County and City Health Officials. Washington, DC: National Association of County and City Health Officials; 2008. National profile of local health departments. Available at: http://www.naccho.org/topics/infrastructure/profile/resources/2008report/upload/NACCHO_2008_ProfileReport_post-to-website-2.pdf. Accessed December 5, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bartholomew D, Steele F, Moustaki I, Galbraith J. Analysis of Multivariate Social Science Data. 2nd ed. Boca Raton, FL: Chapman & Hall/CRC; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hagenaars JA, McCutcheon AL. Applied Latent Class Analysis. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bekemeier B, Dunbar M, Bryan B, Morris ME. Local health departments and specific maternal and child health expenditures: relationships between spending and need. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2012;18(6):615–622. doi: 10.1097/PHH.0b013e31825d9764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bekemeier B, Grembowski D, Yang YR, Herting JR. Local public health delivery of maternal child health services: are specific activities associated with reductions in Black–White mortality disparities? Matern Child Health J. 2012;16(3):615–623. doi: 10.1007/s10995-011-0794-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]