Abstract

Summary

Background

Characterisation of risk groups who may benefit from pneumococcal vaccination is essential for the generation of recommendations and policy.

Methods

We reviewed the literature to provide information on the incidence and risk of invasive pneumococcal disease (IPD) in at-risk children in Europe and North America. The PubMed database was searched using predefined search terms and inclusion/exclusion criteria for papers reporting European or North American data on the incidence or risk of IPD in children with underlying medical conditions.

Results

Eighteen references were identified, 11 from North America and 7 from Europe, with heterogeneous study methods, periods and populations. The highest incidence was seen in US children positive for human immunodeficiency virus infection, peaking at 4167 per 100,000 patient-years in 2000. Studies investigating changes in incidence over time reported decreases in the incidence of IPD between the late 1990s and early 2000s. The highest risk of IPD was observed in children with haematological cancers or immunosuppression. Overall, data on IPD in at-risk children were limited, lacking incidence data for a wide range of predisposing conditions. There was, however, a clear decrease in the incidence of IPD in at-risk children after the introduction of 7-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine into immunisation programmes, as previously demonstrated in the general population.

Conclusion

Despite the heterogeneity of the studies identified, the available data show a substantial incidence of IPD in at-risk children, particularly those who are immunocompromised. Further research is needed to determine the true risk of IPD in at-risk children, particularly in the post-PCV period, and to understand the benefits of vaccination and optimal vaccination schedules.

Review criteria

The PubMed database was searched using predefined search terms, with predefined inclusion and exclusion criteria applied to the search results. Information from papers identified relevant to the research questions was tabulated in full, and summarised in the body of the manuscript.

Message for the clinic

Data on the incidence of IPD in children with underlying medical conditions are limited, and more research is needed to determine the true risk of disease. The available data show a substantial incidence of IPD in at-risk children, particularly those who are immunocompromised, with a corresponding increase in risk compared with healthy children.

Introduction

Invasive pneumococcal disease (IPD), which includes potentially fatal conditions such as meningitis, septicaemia and pneumonia, is responsible for an estimated 11% of all deaths worldwide in children aged < 5 years 1. Before 2000, the only pneumococcal vaccine available was a 23-valent purified capsular polysaccharide vaccine (PPV-23), which is associated with poor or absent immunogenicity in children < 2 years of age and immunodeficient patients, and failure at any age to induce immunological memory following revaccination 2.

A seven-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV-7) against key Streptococcus pneumoniae serotypes was licenced in the USA in February 2000 and subsequently in the European Union and Canada 3,4. Since then, many countries have introduced universal PCV immunisation programmes (between 2006 and 2008 in Europe, for example). In the USA and Canada, pneumococcal vaccination is recommended for universal childhood vaccination in children under 59 months of age, and in older children (60–71 months and >60 months of age, respectively) in individuals at high risk of IPD 5,6. In some European countries, such as the UK, France and Germany, PCV-7 was first recommended only for children at high risk of pneumococcal infection before being introduced into national immunisation programmes 3. These universal vaccination programmes with PCV-7 have led to major improvements in public health, with significant decreases in the incidence of vaccine-type IPD and, to a lesser extent, a decrease in overall IPD in most countries 4,7–10. As the introduction of PCV-7, however, the epidemiology of S. pneumoniae has evolved, with changes in serotype distribution 11. Higher valent PCVs – PCV-10 and PCV-13 – have subsequently been introduced to adapt to these changes and have gradually superseded PCV-7 2.

In children, PCV-10 is licenced for those aged 6 weeks to 5 years, and PCV-13 is licenced for those aged 6 weeks to 17 years 12–14 – these vaccines are currently used in general childhood immunisation programmes – whereas PPV-23 is recommended for children ≥2 years of age in whom there is an increased risk of morbidity and mortality from pneumococcal disease 15. Some health authorities and scientific societies, however, also recommend the use of PCV-13 in a broader range of individuals at increased risk of IPD, particularly, those with underlying medical conditions such as innate or acquired immunodeficiency, deficient splenic function, cochlear implants or cerebrospinal fluid leak 16–19. Characterisation of those risk groups who may benefit from PCV-13 is essential for the generation of recommendations and for helping policy makers to produce policy for vaccination programmes based on the best available evidence 20,21. We conducted, therefore, a literature review to provide up-to-date information on the incidence and risk of invasive IPD in Europe and North America in children with underlying conditions that place them at increased risk of IPD.

Methods

A search of the PubMed database was conducted using the following search string: ‘pneumococc* AND (pneumonia OR sinusitis OR meningitis OR bacteremia OR bacteraemia OR sepsis OR osteomyelitis OR septic arthritis OR endocarditis OR peritonitis OR pericarditis OR cellulitis OR soft tissue infection OR brain abscess OR mastoiditis OR empyema OR septicaemia OR “invasive pneumococcal disease” OR “invasive pneumococcal infection”)’. A built-in PubMed filter was used to limit the search to studies in children (0–18 years of age), and search results were limited to papers published in English between 1 January 2005 and 31 July 2012.

Papers were included in the review if they reported data from Europe or North America on the incidence or risk of IPD in ‘at-risk’ children, defined as those with underlying medical conditions placing them at increased risk of IPD (Table1).

Table 1.

Risk categories for invasive pneumococcal disease included in the review*

| Immunocompetent at-risk groups | Immunocompromised at-risk groups |

|---|---|

|

|

Definition of some individual risk categories (e.g. chronic/severe asthma) may vary between publications and between guidelines.

CNS, central nervous system; CVID, common variable immunodeficiency; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; HL, Hodgkin lymphoma; IPD, invasive pneumococcal disease; NHL, non-Hodgkin lymphoma; SCID, severe combined immunodeficiency.

Results

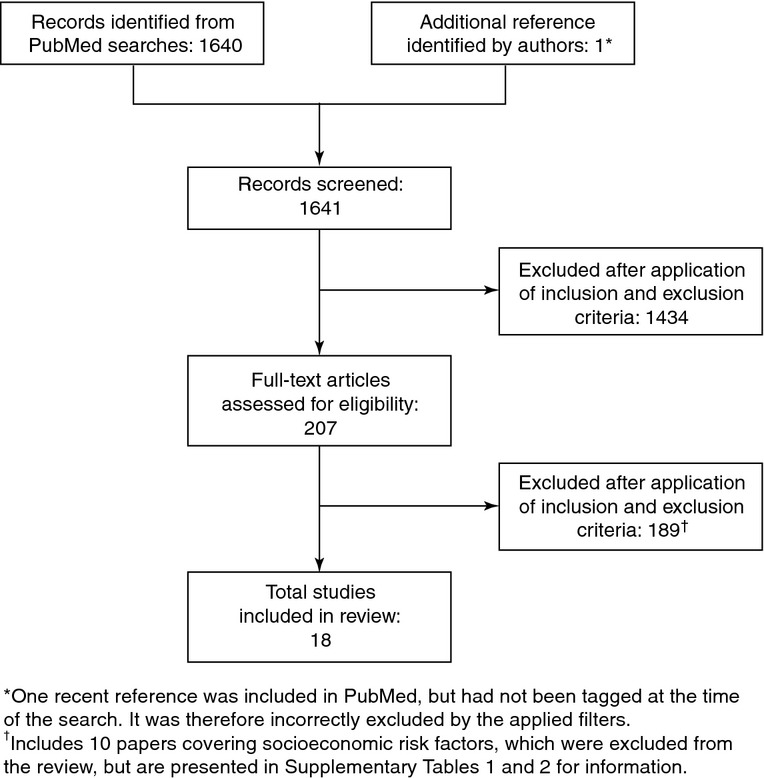

In total, 1640 references were identified by the literature search, of which 1435 were excluded on the basis of the title or abstract; the remaining 18 references met the inclusion and exclusion criteria (Figure1) 22–39. A further 10 papers were identified that reported incidence of IPD in indigenous populations and specific ethnic populations considered to be at increased risk of IPD 40–49. While these socioeconomic risk groups are outside the scope of this review, the details of these papers are presented in supplementary tables for the reader's interest (Tables S1 and S2).

Figure 1.

Results of literature search and evaluation of identified studies according to Preferred Reporting Terms for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses

Of the 18 included studies, six looked at several different time points within a specific period (1989–2006 24, 1995–2002 25,31, 1995–2004 26, 1996–2005 27 and 2001–2007 39). The other studies reported overall data in a single period of time: 1963–2003 23, 1964–2003 36, 1977–2005 32, 1980–2005 37, 1990–2001 28, 1995–2000 29, 1995–2002 35, 1996–2002 38, 1997–2003 34, 1997–2004 30, 2001–2004 33 and 2008–2009 22. Half of the studies were conducted in the USA 24–27,30,33,35,38,39, three studies in the UK 22,23,29, two each in Canada 28,31 and Denmark 32,37, and one each in Germany 34 and Sweden 36. All 18 studies were conducted in children, although only two included children of any age from 0 to 18 years 24,31. The remaining studies limited the age range of the children included (Tables2 and 3).

Table 2.

Incidence of general invasive pneumococcal disease in children

| Citation (country) | Methodology | Age range (years [median]) | N * | Time period | Incidence (per 100,000 patient-years) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Asplenia/splenic dysfunction | |||||

| van Hoek 2012 (UK) 22 | National GP database study | 2–15 [–] | 11 | 08–09 | 19 |

| Chronic heart disease | |||||

| van Hoek 2012 (UK) 22 | National GP database study | 2–15 [–] | 48 | 08–09 | 16 |

| Chronic renal disease | |||||

| van Hoek 2012 (UK) 22 | National GP database study | 2–15 [–] | 33 | 08–09 | 46 |

| Chronic liver disease | |||||

| van Hoek 2012 (UK) 22 | National GP database study | 2–15 [–] | 9 | 08–09 | 117 |

| Chronic respiratory disease | |||||

| van Hoek 2012 (UK) 22 | National GP database study | 2–15 [–] | 19 | 08–09 | 50 |

| Coeliac disease | |||||

| Thomas 2008 (UK) 23 | Regional hospitalisation database | < 15 [–] | ∽2200 | 63–03 | 113† |

| Diabetes | |||||

| van Hoek 2012 (UK) 22 | National GP database study | 2–15 [–] | 9 | 08–09 | 15 |

| HIV infection | |||||

| Steenhoff 2008 (PA, USA) 24 | Retrospective cohort study | 0.2–16.8 [6.3] | 20 | 89–06 | 1200 |

| 89–95 | 1862 | ||||

| 1996 | 2128 | ||||

| 97–99 | 292 | ||||

| 2000 | 3101 | ||||

| 01–06 | 860 | ||||

| 0.2–< 5 [–] | – | 89–95 | 2174 | ||

| 1996 | 2273 | ||||

| 97–99 | 0 | ||||

| 2000 | 0 | ||||

| 01–06 | 1724 | ||||

| 5–16.8 [–] | – | 89–95 | 1000 | ||

| 1996 | 2000 | ||||

| 97–99 | 444 | ||||

| 2000 | 4167 | ||||

| 01–06 | 716 | ||||

| van Hoek 2012 (UK) 22 | National GP database study | 2–15 [–] | 6 | 08–09 | 398 |

| Immunosuppression | |||||

| van Hoek 2012 (UK) 22 | National GP database study‡ | 2–15 [–] | 174 | 08–09 | 162 |

| Sickle-cell disease | |||||

| Adamkiewicz 2008 (GA, USA) 25 | Surveillance database study | ≤10 [–] | 1247 | 95–99 | 170 |

| 2000 | 140 | ||||

| 2001 | 70 | ||||

| 2002 | 40 | ||||

| Halasa 2007 (TN, USA) 26 | Database (Medicaid) study | < 5 [–] | 21 | 95–99 | 2044 |

| 2000 | 1077 | ||||

| 01–04 | 134 | ||||

| < 2 [–] | 16 | 95–99 | 3630 | ||

| 2000 | 3012 | ||||

| 01–04 | 335 | ||||

| Poehling 2010 (TN, USA) 27 | State-managed healthcare database study (Hb S or C trait) | < 5 [–] | 38 | 96–05 | 139.8 |

| 21 | 96–00 | 260.8 | |||

| 7 | 01–05 | 46.0 | |||

| State-managed healthcare database study (Hb S trait) | < 5 [–] | 30 | 96–05 | 142.6 | |

| 19 | 96–00 | 300.9 | |||

| 3 | 01–05 | 25.6 | |||

| State-managed healthcare database study (Hb C trait) | < 5 [–] | 8 | 96–05 | 130.1 | |

| 2 | 96–00 | 115.0 | |||

| 4 | 01–05 | 113.7 | |||

| Transplant recipients | |||||

| Tran 2005 (ON, Canada) 28 | Retrospective single-centre study | < 5 [–] | 522 | 90–01 | 176 |

| General high-risk patients | |||||

| Melegaro 2006 (UK) 29 | National hospital database study§ | < 1 month [–] | – | 95–00 | 75.3 |

| 1–11 months [–] | 38.6 | ||||

| 1–4 [–] | 11.6 | ||||

| 5–9 [–] | 2 | ||||

| 10–14 [–] | 1 | ||||

| van Hoek 2012 (UK) 22 | National GP database study¶ | 2–15 [–] | 261 | 08–09 | 46 |

Total number of patients in analysis.

Based on 3.4 cases per 1000 patients over median follow-up of 3 years.

Includes those who are immunocompromised by disease, such as HIV or leukaemia, asplenia or splenic dysfunction.

‘High risk’ defined as diabetes mellitus, chronic renal, hepatic or pulmonary disease, neoplastic disease, chronic immunosuppression.

‘High risk’ defined as asplenia/splenic dysfunction (including sickle-cell disease and coeliac syndrome), chronic renal, hepatic, heart or respiratory disease (including organ transplantation), diabetes mellitus, immunosuppression (including HIV, leukaemia and bone marrow transplantation), cochlear implants and cerebrospinal fluid leaks.

GP, general practitioner; Hb, haemoglobin; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus.

Table 3.

Incidence of specific forms of invasive pneumococcal disease in children

| Citation (country) | Methodology | Risk category | Age range (years [median]) | N * | Time period | Incidence (per 100,000 patient-years) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Meningitis | ||||||

| Biernath 2006 (USA) 30 | Cohort study | Cochlear implants | < 6 [55 months] | 4265 | 97–04 | 120 |

| Wilson-Clark 2006 (Canada) 31b | Postal survey | Cochlear implants | <18 [–] | 482 | 95–02 | 290 |

| <6 [–] | ||||||

| < 18 [–] | – | 95–98 | 220 | |||

| 99–02 | 400 | |||||

| < 6 [–] | – | 95–98 | 150 | |||

| 99–02 | 310 | |||||

| Melegaro 2006 (UK) 29 | National hospital database study † | General high-risk patients | < 1 month [–] | – | 95–00 | 15.6 |

| 1–11 months [–] | 15.3 | |||||

| 1–4 [–] | 1.7 | |||||

| 5–9 [–] | 0.2 | |||||

| 10–14 [–] | 0.2 | |||||

| Bacteraemia | ||||||

| Steenhoff 2008 (PA, USA) 24 | Retrospective cohort study | HIV infection | – | – | 08–09 | 398 |

Total number of patients in analysis.

Includes some bacterial meningitis cases related to Neisseria meningitidis or of unknown bacterial type.

HIV, human immunodeficiency virus.

Sixteen of the 18 studies reported on IPD as a whole 22–29,32–39, although two of those 16 also looked at specific conditions (meningitis 29 and bacteraemia 24). The remaining two studies focused specifically on meningitis 30,31. With regard to outcomes, six of the 18 studies included data only on the incidence of IPD 24–26,29–31, eight included data only on risk 32–39, and the remaining four included both incidence and risk data 22,23,27,28.

Incidence of IPD

Data on the incidence of any IPD in at-risk children are shown in Table2. The overall incidence ranged from 1 to 4167 per 100,000 patient-years, with the exception of one study of human immunodeficiency virus [HIV] in US children. This study had no reported cases of IPD in children aged < 5 years after the introduction of highly active antiretroviral therapy in 1996, leading to a stated incidence of 0 in 2000 and 1997–1999 24. The highest incidence was seen in children aged > 5 years with HIV in the USA, peaking at 4167 per 100,000 patient-years in 2000 24. The incidence in children with sickle-cell disease in the USA was also high, with a peak of 3630 per 100,000 patient-years in 1995–1999 26, although two other studies reported lower incidences for a similar time period (170–301 per 100,000 patient-years) 25,27.

Across age groups, higher incidences of IPD were generally seen in younger vs. older children. In a study in children with sickle-cell disease, for example, the incidence in those aged < 2 years was 335–3630 per 100,000 patient-years, compared with 134–2044 for those aged < 5 years 26. Similarly, a study in the UK in a predefined high-risk group (diabetes mellitus, chronic renal, hepatic or pulmonary disease, neoplastic disease, chronic immunosuppression) found an incidence of 38.6–75.3 per 100,000 patient-years in children aged < 1 year, compared with 1–11.6 per 100,000 patient-years in children aged 1–14 years 29.

Three US database studies investigated the changing incidence of IPD over time in children with sickle-cell disease 25–27. All three studies showed large decreases in the incidence of IPD between the late 1990s and early 2000s, from 115–3630 per 100,000 patient-years in 1995–2000 to 26–335 in 2001–2005. Similar trends were observed in a retrospective US study in children with HIV in which the incidence decreased from 1862 in 1989–1995 to 860 in 2001–2006 24.

The incidence of IPD in different clinical presentations (meningitis and bacteraemia) in at-risk children is shown in Table3. Three studies described the incidence of meningitis (overall range: 0.2–400 per 100,000 patient-years) 29–31. One survey described an increased incidence of meningitis in children with cochlear implants between 1995–98 and 1999–2000, after the introduction of cochlear implant positioners 31. The time between implantation and meningitis infection varied from 7 months to 7.7 years (median: 11 months). In at-risk children, the reported incidence of meningitis in the UK between 1995 and 2000 was higher in children < 11 months of age than in those aged 1–14 years 29. Regarding other clinical manifestations, the incidence of bacteraemia in HIV-infected children (2008–2009) was 398 per 100,000 patient-years 24.

Risk of IPD

Thirteen studies described the risk of IPD (Table4) in 18 different risk populations. The highest risk was observed in children with haematological cancers (adjusted risk ratio: 52.1 [95% confidence interval (CI): 13.7–198.2] 32; standardised incidence ratio [age 5–9 years]: 50.6 [16.1–122.1] 34) and immunosuppressed children (odds ratio: 41.0 [95% CI: 35.0–48.0]) 22, specifically those with HIV infection (odds ratio: 100.8 [95% CI: 44.7–227.2]) 22. Lower risk ratios (≤ 1.5) were reported for respiratory conditions 32,33, gastrointestinal disease 32 (including coeliac disease 23), congenital immune deficiency 32, diabetes 32, cerebral palsy 32 and hydrocephalus 32.

Table 4.

Risk of IPD in children

| Citation (country) | Methodology | Clinical manifestation | Age range (years) | N | Time period | Comparator children | Risk (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chronic organ disease | |||||||

| Heart disease | |||||||

| Hjuler 2008 (Denmark) 32 | Surveillance database study (all heart disease) | IPD | 0–17 | – | 1977–2005 | Children with no chronic diseases | aRR = 2.4 (1.6–3.4) |

| Surveillance database study (chronic heart disease) | 14 | aRR = 3.6 (1.4–9.6) | |||||

| Surveillance database study (congenital heart disease†) | 67 | aRR = 2.0 (1.4–3.1) | |||||

| Pilishvili 2010 (USA) 33 | Surveillance study | IPD | 3 months–< 5 years | – | 2001–2004 | Children without IPD | OR = 3.5 (2.1–5.7) *** |

| van Hoek 2012 (UK) 22 | National GP database study | IPD | 2–15 | 48 | 2008–2009 | No risk factors for IPD | OR = 4.1 (3.1–5.5) |

| Liver disease | |||||||

| van Hoek 2012 (UK) 22 | National GP database study | IPD | 2–15 | 9 | 2008–2009 | No risk factors for IPD | OR = 29.6 (15.3–57.2) |

| Lung disease | |||||||

| Hjuler 2008 (Denmark) 32 | Surveillance database study (all lung disease) | IPD | 0–17 | – | 1977–2005 | Children with no chronic diseases | aRR = 1.4 (1.0–1.9) |

| Surveillance database study (chronic airway disease) | 25 | aRR = 4.1 (2.1–7.9) | |||||

| Surveillance database study (asthma) | 60 | aRR = 1.1 (0.7–1.6) | |||||

| Surveillance database study (congenital respiratory malformation) | 11 | aRR = 0.9 (0.4–1.9) | |||||

| Pilishvili 2010 (USA) 33 | Surveillance study (chronic lung condition) | IPD | 3 months–< 5 years | – | 2001–2004 | Children without IPD | OR = 3.5 (1.5–8.0) *** |

| Surveillance study (asthma) | OR = 1.8 (1.5–2.2) *** | ||||||

| Talbot 2005 (USA) 35 | Nested case–control study (asthma) | IPD | 2–4 | 26 | 1995–2002 | Children without IPD | aOR = 2.3 (1.4–4.0) |

| 5–17 | 11 | aOR = 4.0 (1.5–10.7) | |||||

| van Hoek 2012 (UK) 22 | National GP database study | IPD | 2–15 | 9 | 2008–2009 | No risk factors for IPD | OR = 12.7 (8.1–20.0) |

| Renal disease | |||||||

| Hjuler 2008 (Denmark) 32 | Surveillance database study (all renal disease) | IPD | 0–17 | – | 1977–2005 | Children with no chronic diseases | aRR = 4.1 (1.5–11.1) |

| Surveillance database study (chronic renal disease) | 6 | aRR = 18.9 (2.8–127.1) | |||||

| Surveillance database study (congenital renal malformation) | 7 | aRR = 1.6 (0.4–6.3) | |||||

| Pilishvili 2010 (USA) 33 | Surveillance study (kidney disease [no dialysis]) | IPD | 3 months–< 5 years | – | 2001–2004 | Children without IPD | OR = 3.6 (1.1–11.4) * |

| Surveillance study (nephrotic syndrome or renal failure) | OR = 14.7 (2.9–76) ** | ||||||

| van Hoek 2012 (UK) 22 | National GP database study | IPD | 2–15 | 33 | 2008–2009 | No risk factors for IPD | OR = 11.7 (8.3–16.6) |

| Gastrointestinal disease | |||||||

| Hjuler 2008 (Denmark) 32 | Surveillance database study (all gastrointestinal disease) | IPD | 0–17 | – | 1977–2005 | Children with no chronic diseases | aRR = 1.5 (0.9–2.4) |

| Surveillance database study (oesophageal disease) | 8 | aRR = 1.1 (0.4–3.5) | |||||

| Genetic disease/congenital malformation | |||||||

| Hjuler 2008 (Denmark) 32 | Surveillance database study (all genetic disease) | IPD | 0–17 | – | 1977–2005 | Children with no chronic diseases | aRR = 2.1 (1.1–4.1) |

| Surveillance database study (chromosomal abnormalities) | 22 | aRR = 2.5 (1.1–5.6) | |||||

| Surveillance database study (inborn error of metabolism) | 5 | aRR = 1.1 (0.3–4.1) | |||||

| Surveillance database study (congenital gut malformation‡) | 35 | aRR = 1.7 (1.0–2.9) | |||||

| Surveillance database study (congenital CNS malformation§) | 23 | aRR = 2.9 (1.4–6.2) | |||||

| Surveillance database study (cerebral palsy) | 18 | aRR = 1.2 (0.5–3.0) | |||||

| Pilishvili 2010 (USA) 33 | Surveillance study (congenital/developmental disorders) | IPD | 3 months–< 5 years | – | 2001–2004 | Children without IPD | OR = 4.9 (3.0–8.0) *** |

| Immunosuppression | |||||||

| Asplenia/splenic dysfunction/splenectomy | |||||||

| Hjuler 2008 (Denmark) 32 | Surveillance database study | IPD | 0–17 | 6 | 1977–2005 | Children without invasive surgery | aRR = 14.4 (1.3–154.2) |

| Pilishvili 2010 (USA) 33 | Surveillance study | IPD | 3 months–< 5 years | – | 2001–2004 | Children without IPD | OR = 3.9 (0.6–23.5) |

| van Hoek 2012 (UK) 22 | National GP database study | IPD | 2–15 | 11 | 2008–2009 | No risk factors for IPD | OR = 4.7 (2.6–8.5) |

| Coeliac disease | |||||||

| Ludvigsson 2008 (Sweden) 36 | Cohort study | Sepsis | 0–15 | – | 1964–2003 | General population | HR = 3.4 (1.1–10.6) |

| HIV infection | |||||||

| van Hoek 2012 (UK) 22 | National GP database study | IPD | 2–15 | 6 | 2008–2009 | No risk factors for IPD | OR = 100.8 (44.7–227.2) |

| Immunological/metabolic disease | |||||||

| Hjuler 2008 (Denmark) 32 | Surveillance database study (all immunological/metabolic disease) | IPD | 0–17 | – | 1977–2005 | Children with no chronic diseases | aRR = 2.0 (0.9–4.2) |

| Surveillance database study (haemolytic anaemia) | 3 | aRR = 2.9 (0.6–13.8) | |||||

| Surveillance database study (autoimmune disease) | 5 | aRR = 2.6 (0.6–10.7) | |||||

| Surveillance database study (congenital immune deficiency) | 12 | aRR = 1.4 (0.4–4.8) | |||||

| Surveillance database study (diabetes) | 1 | aRR = 0.4 (0.0–14.8) | |||||

| Immunosuppression | |||||||

| Pilishvili 2010 (USA) 33 | Surveillance study (any immunocompromising condition) | IPD | 3 months–< 5 years | – | 2001–2004 | Children without IPD | OR = 4.9 (3.4–6.9) *** |

| Surveillance study (HIV or immune system disorder) | OR = 14.5 (5.7–36.8) *** | ||||||

| Surveillance study (systemic steroid use) | OR = 2.2 (1.6–3.0) *** | ||||||

| van Hoek 2012 (UK)22 | National GP database study | IPD | 2–15 | 174 | 2008–2009 | No risk factors for IPD | OR = 41.0 (35.0–48.0) |

| Sickle-cell disease | |||||||

| Pilishvili 2010 (USA)33 | Surveillance study | IPD | 3 months–< 5 years | – | 2001–2004 | Children without IPD | OR = 5.6 (1.6–19.4) ** |

| Poehling 2010 (TN, USA)27 | State-managed healthcare database study | IPD (Hb S or C trait) | < 5 [–] | 66 | 1996–2005 | White, with normal Hb | RR = 1.77 (1.22–2.55) |

| IPD (Hb S trait) | 52 | RR = 1.80 (1.20–2.69) | |||||

| IPD (Hb C trait) | 14 | RR = 1.66 (0.81–3.39) | |||||

| Transplant recipients | |||||||

| Hjuler 2008 (Denmark)32 | Surveillance database study | IPD | 0–17 | 18 | 1977–2005 | Children without invasive surgery | aRR = 14.3 (3.0–68.2) |

| Tran 2005 (ON, Canada)28 | Retrospective single-centre study | IPD | < 5 [–] | 522 | 1990–2001 | All < 2 years | p = 0.13 (no RR or OR specified) |

| All < 5 years | p < 0.001 (no RR or OR specified) | ||||||

| Neoplastic diseases | |||||||

| Hjuler 2008 (Denmark)32 | Surveillance database study (all cancers) | IPD | 0–17 | – | 1977–2005 | Children with no chronic diseases | aRR = 19.0 (8.7–41.5) |

| Surveillance database study (haematological cancers) | 44 | aRR = 52.1 (13.7–198.2) | |||||

| Surveillance database study (non-haematological cancers) | 19 | aRR = 8.9 (3.1–26.1) | |||||

| Meisel 2007 (Germany)34 | Surveillance database study (acute lymphoblastic leukaemia) | IPD | 0–4 | 5 | 1997–2003 | General population | SIR = 7.6 (2.8–17.0) *** |

| 5–9 | 4 | SIR = 50.6 (16.1–122.1) *** | |||||

| 0–14 | 9 | SIR = 11.4 (5.6–20.9) *** | |||||

| Pilishvili 2010 (USA)33 | Surveillance study (any cancer) | IPD | 3 months–< 5 years | – | 2001–2004 | Children without IPD | OR = 78.0 (10.2–593) *** |

| Thomas 2008 (UK)23 | Regional hospitalisation database | IPD | 0–15 | – | 1963–2003 | General population | Rate ratio = 1.39 (0.51–3.03) |

| Neurological disease | |||||||

| Hjuler 2008 (Denmark)32 | Surveillance database study (all neurological disease) | IPD | 0–17 | – | 1977–2005 | Children with no chronic diseases | aRR = 2.5 (1.7–3.6) |

| Surveillance database study (epilepsy¶) | 37 | aRR = 2.5 (1.5–4.2) | |||||

| Surveillance database study (hydrocephalus) | 17 | aRR = 1.0 (0.4–2.4) | |||||

| Prematurity†† | |||||||

| Hjuler 2007 (Denmark)37 | Multiple database study‡‡ | IPD | 0–< 0.5 | 22 | 1980–2005 | Gestational age 37–42 weeks | aRR = 2.59 (1.39–4.82) |

| 0.5–< 2 | 81 | aRR = 1.54 (1.18–2.02) | |||||

| 2–5 | 22 | aRR = 1.31 (0.79–2.18) | |||||

| Tobacco exposure | |||||||

| Haddad 2008 (USA intermountain west)38 | Telephone survey | IPD | < 1 | 4 | 1996–2002 | Children without IPD | OR = 0.6 (0.2–2.0) |

| 1–< 2 | 6 | OR = 1.8 (0.4–7.7) | |||||

| 2–< 5 | 5 | OR = 2.6 (0.4–15.3) | |||||

| 5–16 | 5 | OR = 1.2 (0.3–4.6) | |||||

| Pilishvili 2010 (USA)33 | Surveillance study (household exposure to smoking) | IPD | 3 months–< 5 years | – | 2001–2004 | No tobacco exposure | OR = 1.4 (1.2–1.7) *** |

| Surveillance study (> 20 cigarettes/day) | OR = 1.7 (1.2–2.4) *** | ||||||

| Surveillance study (11–20 cigarettes/day) | OR = 0.9 (0.6–1.3) | ||||||

| Surveillance study (1–10 cigarettes/day) | OR = 1.7 (1.3–2.2) *** | ||||||

| General high-risk patients | |||||||

| Haddad 2008 (USA intermountain west)38 | Telephone survey§§ | IPD | 0–16 | 32 | 1996–2002 | Children without IPD | 32 of 120 cases vs. 1 of 156 controls (no RR or OR specified) |

| Hjuler 2008 (Denmark)32 | Surveillance database study (all chronic diseases¶¶) | IPD | 0–17 | 744 | 1977–2005 | Children with no chronic diseases | aRR = 2.4 (2.0–2.9) |

| Surveillance database study (all chronic diseases excluding high-risk groups†††) | – | aRR = 2.1 (1.7–2.6) | |||||

| Hsu 2011 (MA, USA)39 | Surveillance database study‡‡‡ | IPD | 0–17 | 14 | 2001–2002 | Children with no known risk conditions | – |

| 0–17 | 23 | 2002–2003 | aOR = 1.5 (0.7–3.3) | ||||

| 0–17 | 11 | 2003–2004 | aOR = 0.9 (0.4–2.1) | ||||

| 0–17 | 20 | 2004–2005 | aOR = 1.6 (0.7–3.5) | ||||

| 0–17 | 14 | 2005–2006 | aOR = 0.8 (0.4–1.9) | ||||

| 0–17 | 13 | 2006–2007 | aOR = 0.6 (0.3–1.5) | ||||

| 5–17 | 39 | 2001–2007 | aOR = 2.8 (1.8–4.5) | ||||

| Pilishvili 2010 (USA)33 | Surveillance study§§§ | IPD | 3 months–< 5 years | – | 2001–2004 | Children without IPD | OR = 3.3 (2.4–4.5) *** |

| van Hoek 2012 (UK)22 | National GP database study¶¶¶ | IPD | 2–15 | 261 | 08–09 | No risk factors for IPD | OR = 11.7 (10.2–13.3) |

p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001.

Septal heart defects contributed to 40%.

Major contributors were biliary atresia (26%) and oesophageal atresia (20%).

Major contributors were cerebral cysts (20%), microcephalus (20%) and congenital hydrocephalus (20%).

Concomitant chronic neurological disease in 43%.

‘Prematurity’ defined as gestational age 19–36 weeks.

Databases include national Streptococcus, civil registration, childcare, birth, patient and labour market databases.

‘High risk’ defined as any underlying chronic illness (including cancer, asplenia, lupus, renal failure, liver disease, congenital heart disease, immunosuppressive therapy to prevent transplant rejection, and CNS disorders characterised by severe developmental delay, failure to thrive, or craniofacial structural abnormalities).

The total number is lower than the number of specific chronic diseases because patients may have > 1 of the specific chronic diseases.

Excluding children with cancer, chronic renal disease, splenectomy or transplantation; not adjusted for specific chronic diseases.

‘High-risk’ defined as sickle-cell disease, congenital or acquired asplenia or splenic dysfunction, HIV infection, cochlear implants, congenital immune deficiency, diseases associated with immunosuppressive therapy or radiation therapy, chronic cardiac disease, chronic pulmonary disease, chronic renal insufficiency, cerebrospinal leaks from congenital malformation, skull fracture or neurological procedure, diabetes mellitus, premature birth (< 38 weeks) or low birth weight (< 2500 g).

‘High risk’ defined as any chronic disease.

‘High risk’ defined as asplenia/splenic dysfunction (including sickle-cell disease and coeliac syndrome), chronic renal, hepatic, heart or respiratory disease (including organ transplantation), diabetes mellitus, immunosuppression (including HIV, leukaemia and bone marrow transplantation), cochlear implants and cerebrospinal fluid leaks.

aOR, adjusted odds ratio; aRR, adjusted rate ratio; CI, confidence interval; CNS, central nervous system; GP, general practitioner; Hb, haemoglobin; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; HR, hazard ratio; IPD, invasive pneumococcal disease; OR, odds ratio; RR, relative risk; SIR, standardised incidence ratio.

Discussion

This review has revealed the limited data available on the incidence of IPD in children with underlying medical conditions. Very few publications were from European countries, although it should be noted that non-English language publications were excluded from the search. Data on incidence in children were also absent for several conditions known to increase the risk of IPD in children and adults, such as cancer, diabetes mellitus, primary immunodeficiencies and other immune-mediated conditions 50–52.

Despite the heterogeneity of study methods, periods and populations, the review clearly shows the increased risk of IPD in at-risk children, particularly those who are immunocompromised, compared with the incidence in the general paediatric population (estimated in the USA at 23.6 per 100,000 children aged < 5 years and at 2.4 per 100,000 in children aged 5–17 years) 53. The incidence of IPD was highest in children with HIV, although one study in children with sickle-cell disease showed a similarly high incidence of IPD. When children of different age groups were compared, the youngest children (i.e. infants) generally had a higher incidence of IPD than older children, although there was still a substantial risk of disease in older children.

In studies in which different time points were described there was a clear decrease in the incidence of IPD after the introduction of PCV-7 vaccination into national immunisation programmes, as has also been observed in the general paediatric and adult populations 54. Importantly, one of the case–controlled studies of IPD risk in children described a lower vaccination rate in children with IPD compared with non-IPD controls 38. While PCVs have a limited number of serotypes, those included are associated with a marked clinical burden 55–59. Vaccination of high-risk children, regardless of age, does therefore provide an opportunity to protect them against IPD. It is noteworthy that PPV-23 vaccination of children older than 2 years and at risk of IPD is recommended in some countries. Unfortunately, pneumococcal vaccination coverage in high-risk children is relatively low compared with routine childhood vaccination with PCVs 60–62. For example, an Italian study in children with HIV infection, cystic fibrosis, liver transplantation or diabetes mellitus found that pneumococcal vaccination rates were below 25% in each group 60. Thus, there is a need for education of healthcare professionals, patients and families regarding the importance of vaccination in at-risk children. The increased risk of IPD with tobacco exposure also highlights the importance of broader educational programmes covering environmental factors that may affect disease risk, particularly in children with other risk factors.

Studies of risk described an increased risk of IPD in children with underlying conditions compared with controls. The highest risk of IPD was seen in immunocompromised children, particularly in patients with HIV infection or haematological cancer. Other chronic conditions (including, among others, congenital forms of immune deficiency, renal disease and heart disease), however, showed non-significant increases in risk compared with controls. This led the authors of one study to suggest that frailty and susceptibility to disease in general, leading to frequent hospital contacts, may be as strong a predictor of IPD as a stabilised specific underlying condition 32.

The main strength of this review is the use of broad inclusion criteria relating to clinical outcomes. Limitations of the review include the predefined risk conditions, which might lead to exclusion of some risk conditions such as hydrocephalus. The studies included were very different in terms of study periods and study methods (survey, surveillance database and cohort studies), providing a very wide range of results. Precaution should be taken when interpreting and comparing these results. Definitions of conditions implying an increased risk for pneumococcal infections and some of the individual risk categories vary between publications. Thus, physicians should refer to their local guidelines and national immunisation recommendations.

In conclusion, data on the incidence of IPD in children with underlying medical conditions are limited, and much research is needed in this area to determine the risk of disease, particularly in the post-PCV period. The data available, however, clearly show a substantial incidence of IPD in at-risk children, particularly those who are immunocompromised; there is also a corresponding significant increase in risk compared with healthy children.

Recently, PCV-13 became available for the prevention of IPD, pneumonia and acute otitis media in children 6 weeks to 17 years of age, and for the prevention of IPD in adults > 50 years of age 13. Furthermore, a number of European countries are recommending the use of PCVs in individuals with underlying diseases or conditions. Current vaccination recommendations aim to protect against the maximum number of serotypes by combining PCV-13 with PPV-23 5,19. Further research is needed, however, to understand the benefits of PCVs and the optimal vaccination schedule in this population. After implementation of vaccination programmes, surveillance remains of the utmost importance to our understanding of how the risk of disease and the causative serotypes evolve.

Acknowledgments

The authors take full responsibility for the content of this article and thank Neostar Communications Limited, Oxford, UK (supported by Pfizer, France), for their assistance in preparing the manuscript, including preparing the first draft in close collaboration with the authors and the collation of author comments. Medical writing support was funded by Pfizer Pharmaceuticals, France. Employees of Pfizer Ltd, UK, and Pfizer Pharmaceuticals, France, were involved in the design, drafting, review and approval of the manuscript, and are listed as full authors.

Author contributions

All authors were involved in the concept/design of the review, analysis of the data, and drafting, critical review and approval of the manuscript.

Supporting Information

Table S1Incidence of IPD in children from a) indigenous populations; and b) non-white ethnic groups

Table S2 Risk of IPD in indigenous populations and non-white ethnic groups

References

- O'Brien KL, Wolfson LJ, Watt JP, et al. Burden of disease caused by Streptococcus pneumoniae in children younger than 5 years: global estimates. Lancet. 2009;374:893–902. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61204-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organisation. Pneumococcal vaccines. WHO position paper - 2012. Wkly Epidemiol Rec. 2012;87:129–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Carvalho Gomes H, Muscat M, Monnet DL, Giesecke J, Lopalco PL. Use of seven-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV7) in Europe, 2001-2007. Euro Surveill. 2009;14 . pii: 19159. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McClure CA, Ford MW, Wilson JB, Aramini JJ. Pneumococcal conjugate vaccination in Canadian infants and children younger than five years of age: recommendations and expected benefits. Can J Infect Dis Med Microbiol. 2006;17:19–26. doi: 10.1155/2006/835768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nuorti JP, Whitney CG. Prevention of pneumococcal disease among infants and children - use of 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine and 23-valent pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine - recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) MMWR Recomm Rep. 2010;59:1–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desai S, McGeer A, Quach-Thanh C, Elliott D. An advisory committee statement, National Advisory Committee on Immunization (NACI): update on the use of conjugate pneumococcal vaccines in childhood. Canadian Communicable Disease Report 2010. http://www.phac-aspc.gc.ca/publicat/ccdr-rmtc/10vol36/acs-12/acs-12-eng.pdf (accessed April 2013) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Whitney CG, Farley MM, Hadler J, et al. Decline in invasive pneumococcal disease after the introduction of protein-polysaccharide conjugate vaccine. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:1737–46. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa022823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poehling KA, Talbot TR, Griffin MR, et al. Invasive pneumococcal disease among infants before and after introduction of pneumococcal conjugate vaccine. JAMA. 2006;295:1668–74. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.14.1668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gladstone RA, Jefferies JM, Faust SN, Clarke SC. Continued control of pneumococcal disease in the UK - the impact of vaccination. J Med Microbiol. 2011;60:1–8. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.020016-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isaacman DJ, McIntosh ED, Reinert RR. Burden of invasive pneumococcal disease and serotype distribution among Streptococcus pneumoniae isolates in young children in Europe: impact of the 7-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine and considerations for future conjugate vaccines. Int J Infect Dis. 2010;14:e197–209. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2009.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanquet G, Lernout T, Vergison A, et al. Impact of conjugate 7-valent vaccination in Belgium: addressing methodological challenges. Vaccine. 2011;29:2856–64. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GlaxoSmithKline UK. Synflorix Suspension for Injection in Pre-filled Syringe. Uxbridge: GlaxoSmithKline Biologicals SA; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Pfizer Limited. Prevenar 13 Suspension for Injection. Sandwich: Pfizer Limited; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- European Medicines Agency. Prevenar 13 http://www ema europa eu/ema/index jsp?curl=pages/medicines/human/medicines/001104/smops/Positive/human_smop_000452 jsp&mid=WC0b01ac058001d127 2012 (accessed February 2013)

- Sanofi Pasteur MSD Limited. Pneumovax II. Maidenhead: Sanofi Pasteur MSD Limited; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Infectious Diseases. Recommendations for the prevention of Streptococcus pneumoniae infections in infants and children: use of 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV13) and pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine (PPSV23) Pediatrics. 2010;126:186–90. doi: 10.1542/peds.2010-1280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Immunisation Advisory Committee. Pneumococcal infection. Immunisation Guidelines for Ireland. Dublin: Royal College of Physicians Ireland; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Saxon State Ministry for Social Affairs and Consumer Protection. Empfehlungen der Sächsischen Impfkommission zur Durchführung von Schutzimpfungen im Freistaat Sachsen. Dresden: Saxon State Ministry for Social Affairs and Consumer Protection; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Conseil Supérieur de la Santé. Enfants à risque accru d'infections invasives à pneumocoques. Guide de Vaccination. Brussels: Conseil Supérieur de la Santé; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Rozenbaum MH, van Hoek AJ, Fleming D, Trotter CL, Miller E, Edmunds WJ. Vaccination of risk groups in England using the 13 valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine: economic analysis. BMJ. 2012;345:e6879. doi: 10.1136/bmj.e6879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rozenbaum MH, van Hoek AJ, Fleming D, Trotter CL, Miller E, Edmunds WJ. Correction to Vaccination of risk groups in England using the 13 valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine: economic analysis. BMJ. 2012;345:e7437. doi: 10.1136/bmj.e6879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Hoek AJ, Andrews N, Waight PA, et al. The effect of underlying clinical conditions on the risk of developing invasive pneumococcal disease in England. J Infect. 2012;65:17–24. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2012.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas HJ, Wotton CJ, Yeates D, Ahmad T, Jewell DP, Goldacre MJ. Pneumococcal infection in patients with coeliac disease. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;20:624–8. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0b013e3282f45764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steenhoff AP, Wood SM, Rutstein RM, Wahl A, McGowan KL, Shah SS. Invasive pneumococcal disease among human immunodeficiency virus-infected children, 1989-2006. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2008;27:886–91. doi: 10.1097/INF.0b013e3181734f8f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adamkiewicz TV, Silk BJ, Howgate J, et al. Effectiveness of the 7-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine in children with sickle cell disease in the first decade of life. Pediatrics. 2008;121:562–9. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-0018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halasa NB, Shankar SM, Talbot TR, et al. Incidence of invasive pneumococcal disease among individuals with sickle cell disease before and after the introduction of the pneumococcal conjugate vaccine. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;44:1428–33. doi: 10.1086/516781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poehling KA, Light LS, Rhodes M, et al. Sickle cell trait, hemoglobin C trait, and invasive pneumococcal disease. Epidemiology. 2010;21:340–6. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0b013e3181d61af8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tran L, Hebert D, Dipchand A, Fecteau A, Richardson S, Allen U. Invasive pneumococcal disease in pediatric organ transplant recipients: a high-risk population. Pediatr Transplant. 2005;9:183–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3046.2005.00275.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melegaro A, Edmunds WJ, Pebody R, Miller E, George R. The current burden of pneumococcal disease in England and Wales. J Infect. 2006;52:37–48. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2005.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biernath KR, Reefhuis J, Whitney CG, et al. Bacterial meningitis among children with cochlear implants beyond 24 months after implantation. Pediatrics. 2006;117:284–9. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-0824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson-Clark SD, Squires S, Deeks S. Bacterial meningitis among cochlear implant recipients–Canada, 2002. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2006;55(Suppl 1):20–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hjuler T, Wohlfahrt J, Staum KM, Koch A, Biggar RJ, Melbye M. Risks of invasive pneumococcal disease in children with underlying chronic diseases. Pediatrics. 2008;122:e26–32. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-1510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pilishvili T, Zell ER, Farley MM, et al. Risk factors for invasive pneumococcal disease in children in the era of conjugate vaccine use. Pediatrics. 2010;126:e9–17. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-2150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meisel R, Toschke AM, Heiligensetzer C, Dilloo D, Laws HJ, von Kries R. Increased risk for invasive pneumococcal diseases in children with acute lymphoblastic leukaemia. Br J Haematol. 2007;137:457–60. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2007.06601.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talbot TR, Hartert TV, Mitchel E, et al. Asthma as a risk factor for invasive pneumococcal disease. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:2082–90. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa044113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ludvigsson JF, Olen O, Bell M, Ekbom A, Montgomery SM. Coeliac disease and risk of sepsis. Gut. 2008;57:1074–80. doi: 10.1136/gut.2007.133868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hjuler T, Wohlfahrt J, Simonsen J, et al. Perinatal and crowding-related risk factors for invasive pneumococcal disease in infants and young children: a population-based case-control study. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;44:1051–6. doi: 10.1086/512814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haddad MB, Porucznik CA, Joyce KE, et al. Risk factors for pediatric invasive pneumococcal disease in the Intermountain West, 1996-2002. Ann Epidemiol. 2008;18:139–46. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2007.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsu KK, Shea KM, Stevenson AE, Pelton SI. Underlying conditions in children with invasive pneumococcal disease in the conjugate vaccine era. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2011;30:251–3. doi: 10.1097/INF.0b013e3181fab1cf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruce MG, Deeks SL, Zulz T, et al. International Circumpolar Surveillance System for invasive pneumococcal disease, 1999-2005. Emerg Infect Dis. 2008;14:25–33. doi: 10.3201/eid1401.071315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hennessy TW, Singleton RJ, Bulkow LR, et al. Impact of heptavalent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine on invasive disease, antimicrobial resistance and colonization in Alaska Natives: progress towards elimination of a health disparity. Vaccine. 2005;23:5464–73. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2005.08.100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singleton RJ, Hennessy TW, Bulkow LR, et al. Invasive pneumococcal disease caused by nonvaccine serotypes among alaska native children with high levels of 7-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine coverage. JAMA. 2007;297:1784–92. doi: 10.1001/jama.297.16.1784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singleton RJ, Holman RC, Wenger J, et al. Trends in hospitalization for empyema in Alaska Native children younger than 10 years of age. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2011;30:528–30. doi: 10.1097/INF.0b013e3182075e74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wenger JD, Zulz T, Bruden D, et al. Invasive pneumococcal disease in Alaskan children: impact of the seven-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine and the role of water supply. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2010;29:251–6. doi: 10.1097/INF.0b013e3181bdbed5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lacapa R, Bliss SJ, Larzelere-Hinton F, et al. Changing epidemiology of invasive pneumococcal disease among White Mountain Apache persons in the era of the pneumococcal conjugate vaccine. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;47:476–84. doi: 10.1086/590001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Millar EV, Pimenta FC, Roundtree A, et al. Pre- and post-conjugate vaccine epidemiology of pneumococcal serotype 6C invasive disease and carriage within Navajo and White Mountain Apache communities. Clin Infect Dis. 2010;51:1258–65. doi: 10.1086/657070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weatherholtz R, Millar EV, Moulton LH, et al. Invasive pneumococcal disease a decade after pneumococcal conjugate vaccine use in an American Indian population at high risk for disease. Clin Infect Dis. 2010;50:1238–46. doi: 10.1086/651680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsu K, Pelton S, Karumuri S, Heisey-Grove D, Klein J. Population-based surveillance for childhood invasive pneumococcal disease in the era of conjugate vaccine. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2005;24:17–23. doi: 10.1097/01.inf.0000148891.32134.36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsu KK, Shea KM, Stevenson AE, Pelton SI. Changing serotypes causing childhood invasive pneumococcal disease: Massachusetts, 2001-2007. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2010;29:289–93. doi: 10.1097/INF.0b013e3181c15471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Vidal C, Ardanuy C, Gudiol C, et al. Clinical and microbiological epidemiology of Streptococcus pneumoniae bacteremia in cancer patients. J Infect. 2012;65:621–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2012.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pessach I, Walter J, Notarangelo LD. Recent advances in primary immunodeficiencies: identification of novel genetic defects and unanticipated phenotypes. Pediatr Res. 2009;65:3R–12. doi: 10.1203/PDR.0b013e31819dbe1e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wotton CJ, Goldacre MJ. Risk of invasive pneumococcal disease in people admitted to hospital with selected immune-mediated diseases: record linkage cohort analyses. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2012;66:1177–81. doi: 10.1136/jech-2011-200168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pilishvili T, Lexau C, Farley MM, et al. Sustained reductions in invasive pneumococcal disease in the era of conjugate vaccine. J Infect Dis. 2010;201:32–41. doi: 10.1086/648593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan TQ. Pediatric invasive pneumococcal disease in the United States in the era of pneumococcal conjugate vaccines. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2012;25:409–19. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00018-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Hoek AJ, Andrews N, Waight PA, George R, Miller E. Effect of serotype on focus and mortality of invasive pneumococcal disease: coverage of different vaccines and insight into non-vaccine serotypes. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e39150. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0039150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byington CL, Korgenski K, Daly J, Ampofo K, Pavia A, Mason EO. Impact of the pneumococcal conjugate vaccine on pneumococcal parapneumonic empyema. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2006;25:250–4. doi: 10.1097/01.inf.0000202137.37642.ab. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shouval DS, Greenberg D, Givon-Lavi N, Porat N, Dagan R. Site-specific disease potential of individual Streptococcus pneumoniae serotypes in pediatric invasive disease, acute otitis media and acute conjunctivitis. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2006;25:602–7. doi: 10.1097/01.inf.0000220231.79968.f6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruckinger S, von KR, Siedler A, van der LM. Association of serotype of Streptococcus pneumoniae with risk of severe and fatal outcome. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2009;28:118–22. doi: 10.1097/INF.0b013e318187e215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- European Antimicrobial Resistance Surveillance System. EARSS Annual Report. Bilthoven: EARSS; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Giannattasio A, Squeglia V, Lo Vecchio A, et al. Pneumococcal and influenza vaccination rates and their determinants in children with chronic medical conditions. Ital J Pediatr. 2010;36:28. doi: 10.1186/1824-7288-36-28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shankar A, Samraj R, Aiyedun V, Janda M, Ramaiah S. General practitioners' perceptions on pneumococcal vaccination for children in United Kingdom. Hum Vaccin. 2009;5:177–80. doi: 10.4161/hv.5.3.7296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Badertscher N, Morell S, Rosemann T, Tandjung R. General practitioners' experiences, attitudes, and opinions regarding the pneumococcal vaccination for adults: a qualitative study. Int J Gen Med. 2012;5:967–74. doi: 10.2147/IJGM.S38472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1Incidence of IPD in children from a) indigenous populations; and b) non-white ethnic groups

Table S2 Risk of IPD in indigenous populations and non-white ethnic groups