Abstract

Bronchoalveolar stem cells (BASCs) are mobilized during injury and identified as lung progenitor cells, but the molecular regulation of this population of cells has not been elucidated. Secreted frizzled-related protein 1 (SFRP1) is a critical molecule involved in alveolar duct formation in the lung and here we demonstrate its importance in controlling cell differentiation during lung injury. Mice lacking SFRP1 exhibited a rapid repair response leading to aberrant proliferation of differentiated cells. Furthermore, SFRP1 treatment of BASCs maintained these cells in a quiescent state. In vivo overexpression of SFRP1 after injury suppressed differentiation and resulted in the accumulation of BASCs correlating with in vitro studies. These findings suggest that SFRP1 expression in the adult maintains progenitor cells within their undifferentiated state and suggests that manipulation of this pathway is a potential target to augment the lung repair process during disease.—Shiomi, T., Sklepkiewicz, P., Bodine, P. V. N., D'Armiento, J. M. Maintenance of the bronchial alveolar stem cells in an undifferentiated state by secreted frizzled-related protein 1.

Keywords: lung, progenitor cell, SFRP1, Wnt, mouse

The lung is an intricate structure of cells precisely organized for appropriate gas exchange; therefore, regeneration of lung tissue after injury is a complex event. To protect the lung from permanent damage, internal maintenance programs that involve signaling molecules and pathways important for lung development (1, 2) are activated in the adult lung. Studies have shown that the lung maintenance program is central in generating the heterogeneity of lung destruction in emphysema (2).

During lung injury, several lung cell types participate in the repair process. These differing cell types maintain normal alveolar homeostasis through the secretion of various growth factors [hepatocyte growth factor (HGF; ref. 3), keratinocyte growth factor (KGF; refs. 4, 5), and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF; ref. 6)]. The growth factors then promote cell survival and proliferation, with recent studies demonstrating that mesenchymal stem cells facilitate lung repair through the secretion of such growth factors. For example, transplantation of mesenchymal stem cells after acute lung injury improves regeneration, which is hypothesized to occur through the regulation of endogenous tissue stem and progenitor cells. Identification of factors that support the growth of progenitor cells and maintain cell survival is therefore critical to identify potential target pathways that can protect the lung from damage.

Recently, we identified the expression of secreted frizzled-related protein 1 (SFRP1), a Wnt signaling modulator, in human emphysema tissue and demonstrated through the analysis of null mice its critical function during lung development (7). Therefore, to determine whether SFRP1 exhibited a dual role in the control of lung repair, we investigated the function of SFRP1 under conditions of cell regeneration and repair using in vitro cell systems and two mouse models of lung injury. These studies revealed not only an important role for SFRP1 in cell proliferation and differentiation through modulation of the Wnt signaling pathway, but also that SFRP1 is a critical regulator of lung progenitor cell differentiation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mice

All protocols were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Columbia University. Sfrp1−/− mice were crossed into the C57BL/6J background for 10 generations (8) and wild-type (WT) age-matched littermates were utilized as a control for all studies.

Naphthalene and bleomycin administration

Naphthalene (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) was dissolved in corn oil (Sigma-Aldrich; 27.5 mg/ml). The mice were administered 10 ml/kg body weight of naphthalene (275 mg/kg body weight) by intraperitoneal injection. Corn oil was injected for the control studies. For the bleomycin lung injury model, bleomycin (Sigma-Aldrich) was dissolved in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and given intratracheally (5 U/kg body weight) by MicroSprayer (Penn-Century, Philadelphia, PA, USA). PBS was used as control. We tested 5 mice for each time point in each condition (WT/Sfrp1−/− and bleomycin-treated/PBS control).

Histological studies

The mice were euthanized, and a 20-gauge catheter was placed into the trachea and then secured with a suture. The lungs were pressure perfused at 25 cmH2O with 10% formalin for 24 h. Paraffin-embedded tissues were prepared and sections mounted onto slides and stained with hematoxylin and eosin (HE) for histological evaluation. For immunohistochemistry (IHC), the sections were deparaffinized and rehydrated. Antigen retrieval was performed by 20 min of microwaving in tris-(hydroxymethyl) aminomethane (Tris) buffer (pH 9.0). After treatment, sections were incubated with primary antibodies for surfactant protein C (SP-C; 1:2000; AbCam, Cambridge, MA, USA) and CC10 (1:500; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA, USA) overnight at 4°C, followed by incubation with Alexa Fluor 488- and 546-labeled anti-rabbit and anti-goat antibodies (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) and 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI; Invitrogen). For proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA) and Ki-67 staining, sections were incubated with anti-PCNA antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) or anti Ki-67 antibody (BioGenex Laboratories, San Ramon, CA, USA) and pan-cytokeratin (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) or biotinylated cluster of differentiation 45 (CD45; BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA) after the retrieval treatment. Vector Mouse on Mouse Kit (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA, USA) and Impress (Vector Laboratories) or alkaline phosphatase-labeled ABC complex (Vector Laboratories) was used to detect the signal in further steps.

X-gal staining

The lungs from the Sfrp1+/− mice (n=5) treated with naphthalene were harvested and fixed with 0.2% w/v glutaraldehyde and 2% w/v paraformaldehyde in PBS (pH 7.4) for 1 h at 4°C. Fixative was removed with PBS, followed by the instillation of X-gal solution (20 mM potassium ferrocyanide, 20 mM potassium ferricyanide, 2 mM MgCl2, 1 mg/ml X-gal, 0.01% deoxycholic acid, and 0.02% Triton X-100 in PBS, pH 7.4). X-gal staining was performed overnight at 37°C. Lungs were again washed overnight at 4°C with PBS before the instillation of 0.4% paraformaldehyde. The lungs were then embedded in paraffin for sectioning at 5 μm.

Cell culture

Small airway epithelial cells (SAECs) were purchased and maintained in SAEC medium (Lonza, Allendale, NJ, USA). All of the experiments were performed with a cell passage of <5. Human recombinant SFRP1 for use in cell culture was purchased from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN, USA).

SFRP1 treatment of SAECs and analysis

SAECs were treated with 2.0 μg/ml of recombinant SFRP1 (R&D Systems) in culture medium. In the ceramide-induced apoptosis assay, cells were treated with C2-ceramide as described previously (9). All data were obtained with 3 independent experiments. Cell viability in the cell proliferation assay was measured by the AlamarBlue (Invitrogen) kit using the standard manufacturer's protocol. Each assay was performed in triplicate and repeated 3 times.

Lung fibroblast isolation and coculture

Freshly isolated mouse lungs were minced and cultured for 2 h with Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM; Invitrogen) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Invitrogen). After incubation, the culture dishes were washed with medium, and the attached cells were cultured and then subcultured to obtain lung fibroblasts. Isolated fibroblasts were cultured to 80% confluence and treated with 10 μg/ml mitomycin C (Sigma-Aldrich) to prevent further cell proliferation. After treatment, the SAECs were directly added to the fibroblast cell layer. For the coculture studies with BASCs, a cell culture insert was placed into the fibroblast culture wells, and the BASCs were plated onto the insert.

T-cell factor (TCF) reporter assay

TOPflash and FOPflash vectors (Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA) were transfected into SAECs with the transfection reagent (FuGene 6; Roche Applied Science, Indianapolis, IN, USA). The cells were lysed and, luciferase activity was measured (One-Glo Luciferase Assay Reagent; Promega, Madison, WI, USA) using the luminometer (Turner Biosystems, Sunnyvale, CA, USA). Each assay was performed in triplicate, and each assay was reproduced ≥3 times.

Low-density polymerase chain reaction (PCR)-based array

To analyze the effect of SFRP1 on SAECs, SAECs were treated with or without SFRP1 (2 μg/ml) and incubated 24 h. After incubation, the RNA was isolated and the downstream target genes in the Wnt signaling pathway analyzed using a real-time reverse transcription PCR (RT-PCR)-based array (PAMM-243A; Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer's protocol. The data were obtained by normalization of 3 independent experiments.

SFRP1 administration

Recombinant SFRP1 (R&D Systems) was dissolved in PBS to a concentration of 100 μg/ml, and 100 μl (10 μg)/mouse was administered intratracheally using a MicroSprayer (Penn-Century). PBS and bovine serum albumin (3%) in PBS was given intratracheally as a control. A total of 6 mice/group were tested and analyzed at d 3 and 7 after the administration of SFRP1.

BASC isolation

The BASCs were isolated as described previously (10). Briefly, mice were anesthetized, and the lung was perfused with PBS, followed by intratracheal instillation of Dispase (BD Biosciences) and 1% low-melting-point agarose (Lonza). Lungs were iced, minced, and incubated in DNase (Sigma-Aldrich) and collagenase/dispase (Roche Applied Science) in PBS for 45 min at 37°C, then filtered through strainers. After red blood cell lysis treatment, the cells were resuspended in PBS and 10% FBS. Cells were sorted by the cell sorter as described in Supplemental Data. Three independent experiments were performed for the Matrigel/SFRP1-treatment studies.

Image capturing

For bright field imaging, we captured the images with Nikon Eclipse E400 (Nikon Instruments, Melville, NY, USA) and QImaging QIClick digital camera (QImaging, Surrey, BC, Canada). For fluorescent images, the Nikon Eclipse Ti-E inverted microscope system (Nikon Instruments) and Photometrics CoolSNAP HQ2 digital camera (Tucson, AZ, USA) with Nikon NIS-Elements Software were used. For confocal microscopy imaging, the Nikon A1 laser confocal imaging system (Nikon Instruments) was used.

Morphometric and statistical analyses

Morphometric analyses were performed with ImageJ software (U.S. National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA). Statistical analyses were performed with Microsoft Excel (Microsoft, Redmond, WA, USA) and KalidaGraph software (Synergy Software, Reading, PA, USA).

RESULTS

Effect of SFRP1 on the processes of lung regeneration after injury

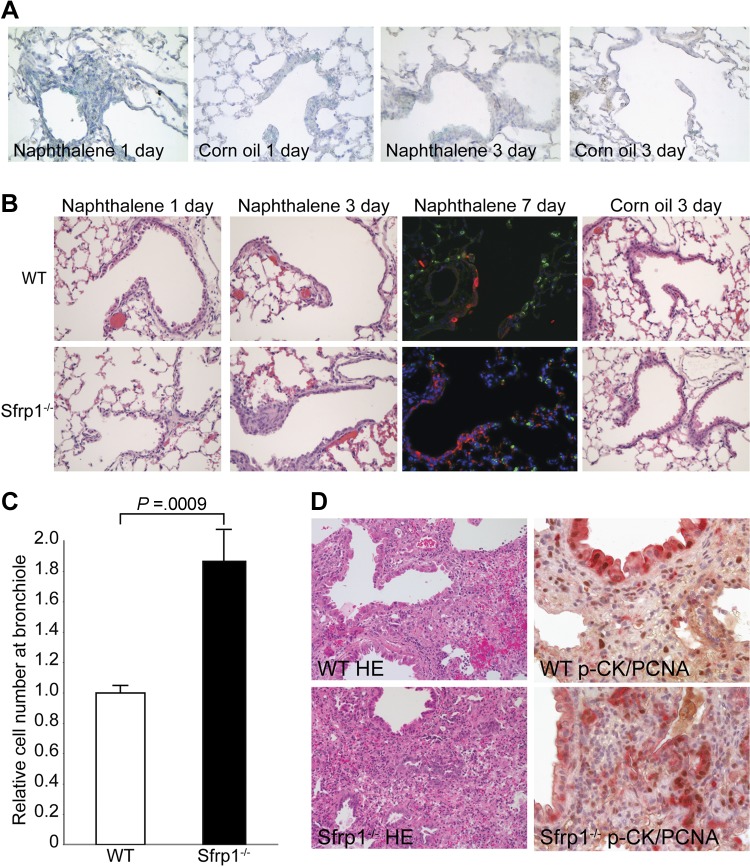

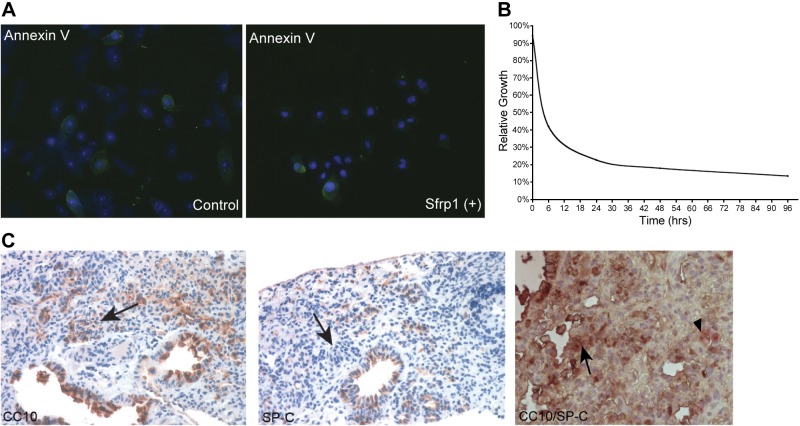

Previous studies from our laboratory demonstrated that SFRP1 is essential during lung development and is reexpressed in lung disease (11). To determine the localization of SFRP1 expression after lung injury, SFRP1-driven LacZ mice were treated with naphthalene, and SFRP1 expression was identified in the cells surrounding the injured epithelium after 1 d, which then decreased 3 d after injury (Fig. 1A). To further define the role of SFRP1 in lung injury and determine the consequence of SFRP1 loss on lung epithelial repair, we examined Sfrp1−/− mice. Sfrp1−/− mice were subjected to both the naphthalene and bleomycin models of lung injury. After naphthalene injury, both WT and Sfrp1−/− mice exhibited degeneration and necrosis of Clara cells, defined by CC10 staining, 1 d after intraperitoneal injection of naphthalene (ref. 12 and Fig. 1B). After 3 d, the Clara cells regenerated, as predicted by the naphthalene injury model (Fig. 1B). When examined histologically, Sfrp1−/− mice exhibited an increase in the number of regenerating cells within the region of the terminal bronchiole when compared to WT mice (Fig. 1B). On treatment with SFRP1, SAECs exhibited protection against ceramide-induced apoptosis (Fig. 2A) and less proliferation compared to the SFRP1-null condition (Fig. 2B). At 7 d after injury, fluorescent IHC demonstrated an increase in CC-10-positive differentiated Clara cells in the regenerative area (Fig. 1B). As expected, both WT and Sfrp1−/− mice treated with corn oil did not develop any epithelial cell damage (Fig. 1B). Quantitative morphometric analysis demonstrated 2 times more cells in the regenerating lung of Sfrp1−/− mice 3 d after injury when compared to WT mice (Fig. 1C). Next, bleomycin, which is toxic to pneumocytes and causes pulmonary fibrosis (13) in the lung, was administered intratracheally to mice using a microsprayer. At 3 wk after treatment with bleomycin, the Sfrp1−/− mice also demonstrated increased epithelial cell regeneration when compared to the WT mice (Fig. 1D, n=5/group). At that time, the lungs from the Sfrp1−/− mice exhibited a greater number of cells with nests resembling the lesions seen in human interstitial fibrosis (14) when compared to the lungs from WT mice (Fig. 1D). IHC of the lung sections revealed an increase in the number of PCNA-positive, pan-cytokeratin-positive epithelial cells (Fig. 1D) in the Sfrp1−/− mice, consistent with an active proliferative process. These proliferating cells were positive for CC10 and negative for SP-C, consistent with the phenotype of differentiated epithelial cells (Fig. 2C).

Figure 1.

Regeneration of the lungs of Sfrp1−/− mice after tissue injury. A) SFRP1 expression in Sfrp1+/− mice after naphthalene injury. X-gal staining was observed in mesenchymal tissue surrounding the terminal bronchial region 1 d after naphthalene injury but not in vehicle (corn oil) control. At 3 d after injury, SFRP1 expression was reduced in the injured lung, and no significant change was observed in the control lung. B) HE staining of lung tissue from WT mice and Sfrp1−/− mice after naphthalene injury. At 1 d after naphthalene administration, lungs exhibited no significant difference between these groups. After 3 d, Sfrp1−/− lungs showed more cells at the terminal bronchiole region. Fluorescent IHC of SP-C (green) and CC10 (red) exhibited more differentiated cells in regenerative area in the terminal bronchiole (mainly CC-10-positive cells) after 7 d of injury (counterstain: blue – DAPI). No difference was seen following corn oil administration (after 3 d, control). C) Morphometric analysis of the injured lung. Cell density was increased 2-fold in the lungs of Sfrp1−/− mice. Ten terminal bronchioles were counted for each mouse, and 5 mice from each group were analyzed. D) HE staining and PCNA IHC on bleomycin-treated lungs. Compared to WT lungs, Sfrp1−/− mice exhibited nests of proliferating epithelial cells adjacent to the terminal bronchioles. Cells in the nests were strongly positive for PCNA (brown). These cells were positive for pan-cytokeratin (red). See also Supplemental Fig. S1.

Figure 2.

Effect of SFRP1 on ceramide-induced apoptosis and cell proliferation. A) SFRP1 protected SAECs from ceramide-induced apoptosis. SFRP1-treated SAECs exhibited less anti-annexin V IHC staining in ceramide-induced apoptosis, representative of the typical data from 3 independent studies on different days. B) SAECs treated with SFRP1 exhibited less cell proliferation. SFRP1 treatment down-regulated the proliferation of SAECs to 30% compared to the nontreated cells. C) Expression of CC10 and SP-C on Sfrp1−/− bleomycin-treated lungs. Cells in the nests positive for PCNA were positive for CC10, but negative for SP-C. This was confirmed by double immunostaining (arrows, brown CC10; arrowhead, red SP-C).

SFRP1 regulates cell differentiation status through the Wnt signaling pathway

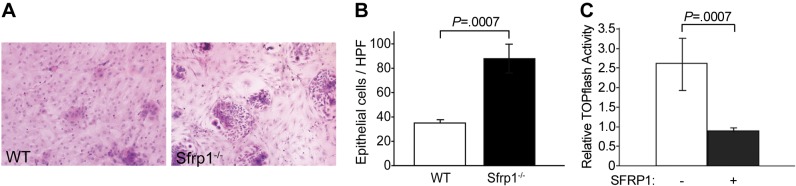

The in vivo progenitor cells mobilized during repair reside in protected locations within the tissue in close contact with other cells that provide the signal to maintain or initiate differentiation (15). In an effort to mimic the potential signaling environment between cells, coculture studies were performed to investigate the interaction between the lung epithelial cells and fibroblasts of WT and Sfrp1−/− animals. Lung fibroblasts were taken from WT and Sfrp1−/− mice, and SFRP1 production was confirmed from the cultured lung fibroblasts from WT mice (Supplemental Fig. S2). SAECs were then cocultured with the respective fibroblasts as a feeder layer. The cocultured SAECs exhibited a reduced rate of growth in the presence of fibroblasts isolated from WT mice when compared to cells grown with fibroblasts from Sfrp1−/− mice (Fig. 3A). Morphometric analysis confirmed a decrease in the growth rate of the epithelial cells grown with WT fibroblasts when compared with the epithelial cells cocultured with Sfrp1−/− fibroblasts (Fig. 3B). Through utilization of a TCF reporter transfected into SAECs, we confirmed that SFRP1 down-regulated TOPflash activity (Fig. 3C) consistent with signaling through the canonical Wnt pathway. Interestingly, SFRP1 treatment of SAECs up-regulated the expression of pluripotency-related genes, such as NANOG (16), SOX2 (16), and bone morphogenetic protein 4 (BMP4; ref. 17), and down-regulated genes associated with differentiation, such as α-type platelet-derived growth factor receptor (PDGFRA; ref. 18) and insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF1; ref. 19) (Table 1; entire data set is presented in Supplemental Table S1). The coculture studies demonstrate that SFRP1 regulation of epithelial cell growth is maintained through the classic canonical Wnt pathway.

Figure 3.

SAEC cocultures with lung fibroblasts from WT and Sfrp1−/− mice. A) HE staining of coculture cells. Compared to the culture with WT lung fibroblasts, increased numbers of SAECs were observed in the culture with Sfrp1−/− lung fibroblast. See also Supplemental Fig. S2. B) Morphometric analysis of coculture system. Cultures with Sfrp1−/− fibroblast exhibited nearly triple the number of SAECs. C) Canonical Wnt signaling pathway activity assay. TOPflash assay exhibited down-regulation of the canonical Wnt pathway by SFRP1. See Table 1 for Wnt signaling target analysis.

Table 1.

Wnt signaling target analysis of genes up- and down-regulated by SFRP1 treatment

| Gene | Fold change |

|---|---|

| Up-regulated | |

| SOX2 | 2.06 |

| TCF4 | 2.26 |

| NANOG | 2.41 |

| BMP4 | 3.05 |

| Down-regulated | |

| PDGFRA | −2.18 |

| LEF1 | −2.74 |

| IGF1 | −3.93 |

RT-PCR based low-density array showed up-regulation of progenitor cell maintenance genes and down-regulation of differentiation induction genes by treatment with SFRP1 on SAECs.

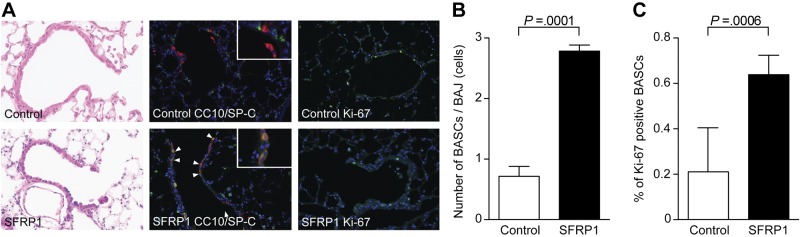

SFRP1 retains lung adult progenitor cells in an undifferentiated state in vivo

Adult lung progenitor cells originating from the terminal bronchiole region are referred to as BASCs (10, 20). These cells are characterized by double immunohistochemical staining for CC10 and SP-C. Although BASCs were initially classified as lung stem cells (10), the exact terminology of a stem cell is controversial with reference to BASCs (21), but nevertheless, these cells are a progenitor cell population within the lung (22). Since loss of SFRP1 resulted in an increase in epithelial cell proliferation, the effect of SFRP1 treatment on the lung repair process in vivo was examined by analyzing the effect of SFRP1 on the BASC population. As shown in Fig. 4A, Sfrp1-treated mice exhibit an increase in the number of cells within the bronchoalveolar junction after injury compared to control mice. The proliferating cells were confirmed to be BASCs using double IHC with laser confocal microscopy imaging (Fig. 4A) and morphometric analysis (Fig. 4B), which demonstrated that the lungs of SFRP1-treated mice displayed 3 times more BASCs as compared to WT mice after 3 d of naphthalene administration (Fig. 4B). These proliferating cells in terminal bronchiole were positive for Ki-67 (Fig. 4A, C) and no obvious positive staining for TUNEL staining was detected (data not shown).

Figure 4.

Proliferation of BASCs in SFRP1-treated mice after injury. A) Control and SFRP10-treated mice with naphthalene injury. In immunofluorescent studies with laser confocal microscopy, proliferation of BASCs (double-positive cells for green SP-C and red CC-10) was observed in SFRP1-treated mice compared to control mice (blue DAPI). These proliferative cells were positive for Ki-67 (green). B) Morphometric analysis of BASC at the bronchial alveolar junction. Ten terminal bronchioles were counted for each mouse, and 5 mice from each group were analyzed. BASCs proliferated at a rate triple that of control following SFRP1 administration. C) Ki-67-positive ratio of BASCs Ten terminal bronchioles were counted for each mouse, and 5 mice from each group were analyzed.

SFRP1 maintains BASCs in an uncommitted state in an ex vivo culture system

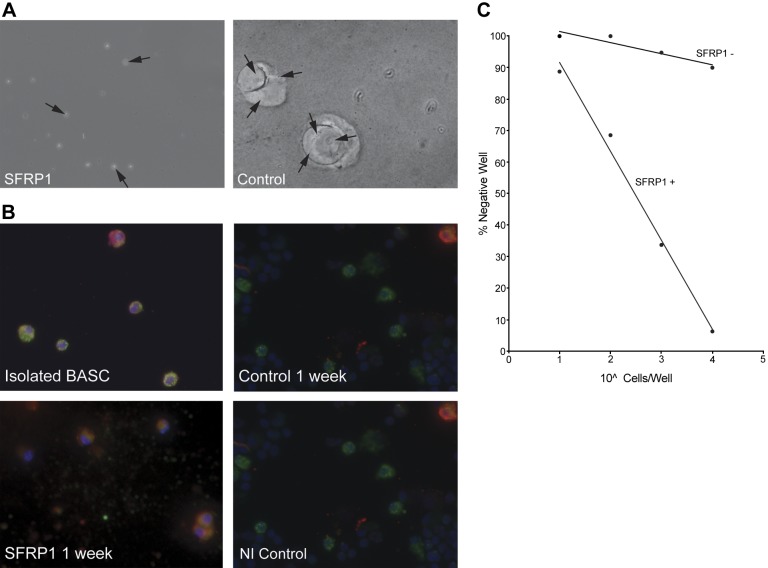

To determine the direct effect of SFRP1 on BASC differentiation, BASCs were isolated from both WT and Sfrp1−/− lungs (Supplemental Fig. S3A). Consistent with the literature describing lung progenitor cells (10, 22), the isolated BASCs stain with SP-C, CC10, and CD104 (Supplemental Fig. S3B, C). Self-renewal assays were performed as described previously (10) by examining colony-forming units from cells plated on Matrigel. By report, BASCs exhibit colony-forming units when cocultured with fibroblasts, but differentiate when cultured on Matrigel (10). The BASCs isolated in our hands from both WT and Sfrp1−/− mice behave as described in the literature (10). Interestingly, when the WT BASCs were cultured on Matrigel treated with SFRP1, the cells did not differentiate, and self-renewal colonies easily formed when compared to BASCs cultured on untreated Matrigel (Fig. 5A, B). BASCs isolated from WT mice differentiated into both Clara cells and type II pneumocytes on Matrigel, as described previously (ref, 10 and Fig. 5C), but remained in the undifferentiated state when treated with SFRP1, as demonstrated by double staining with CC10 and SP-C (Fig. 5C). Coculture of BASCs on Matrigel treated with other SFRP family members (SFRP2–5) had no effect on the behavior of the BASCs. These findings suggest a specific role for fibroblast-secreted SFRP1 in the control of BASC behavior, and moreover, supplemental recombinant SFRP1 can prevent the differentiation of BASCs.

Figure 5.

SFRP1 treatment maintains BASC progenitor cells in the undifferentiated state. A) Self-renewal assay of BASCs. BASCs cultured on Matrigel with SFRP1 maintained their small round cell shape and did not differentiate after 1 wk of culture. On the other hand, BASCs cultured on Matrigel without SFRP1 differentiated and formed organoid structures. Arrows indicate individual cells. Limiting dilution study showed the same result. See also Supplemental Fig. S3. B) SFRP1 maintains the BASC phenotype of cells cultured on Matrigel. Freshly isolated stained BASCs exhibited dual positivity in SP-C (green; dotted pattern) and CC10 (red; diffuse pattern). After 1 wk of culture on Matrigel without sFRP1, BASCs differentiated and exhibited either SP-C or CC10 positive staining. BASCs treated with SFRP1 exhibited dual positive staining, reflecting the maintenance of the undifferentiated state.

DISCUSSION

The present study has utilized gain-of-function and loss-of-function studies to demonstrate that the inhibitor of the Wnt signaling pathway, SFRP1, can maintain the lung progenitor cell population by holding BASCs in their undifferentiated state. The role of the Wnt pathway in regulation of the progenitor cell population has not been elucidated, For instance, Reynolds et al. (23) demonstrated that stabilization of β-catenin leads to the expansion of the progenitor cell pool; on the other hand, Zemke et al. (24) showed that β-catenin was not necessary for the repair of the bronchiolar epithelium. Here, we identify an important function for SFRP1 in maintaining BASCs in an undifferentiated state during injury.

These data demonstrate that regulation of BASCs is specific for SFRP1 and does not occur with other members of the SFRP family. Previous data in our laboratory have demonstrated that SFRP1 was up-regulated during smoke injury specifically in small airway epithelial cells (11) but SFRP2, and not SFRP1, is increased in bronchial epithelial cells of smokers (25). We therefore hypothesize that the SFRP family may serve as regulators of individual progenitor cell niches. Identifying the precise role of these family members in the process of lung injury is critical to understanding the hierarchy of cellular differentiation during lung repair. Alterations in SFRP expression lead to aberrant regulation of the progenitor cell populations, which could account for the varied pathological responses to similar injury in the human disease. The determination of whether the lung will develop fibrosis or apoptosis secondary to injury could be regulated through such a mechanism. These studies suggest that proper BASC maintenance during injury is exquisitely controlled through SFRP1, and disruption of this pathway can lead to unregulated growth, or alternatively, depletion of the progenitor pool.

Maintaining a cell in its undifferentiated state is believed to protect the cell from injury, as is seen with the survival of lung BASCs and variant Clara cells during naphthalene injury. Therefore, our findings indicate that up-regulation of SFRP1 after injury may be beneficial. However, this same process can limit the regenerative capacity of the lung and would result in impaired healing. If the injury process continues for a short period of time, inhibition of differentiation by SFRP1 on progenitor cells allows a sufficient number of progenitor cells to be available for the regenerative phase of the injury. However, in diseases that exhibit chronic elevation of SFRP1 expression, such as demonstrated in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (11), the progenitor cells will be unable to commit to repair and result in cell loss. In light of our studies, we hypothesize that the maintained expression of SFRP1 in emphysema leads to an insufficient supply of differentiated cells from the progenitor cell pool. We speculate that under these conditions, the repair or lung maintenance process falters, and over time with continued injury, the type II pneumocytes and Clara cells gradually decrease in number. On the other hand, in diseases such as interstitial fibrosis and lung cancer, where Wnt signaling is active with low levels of SFRP1, abnormal proliferation of progenitor cells occurs (26, 27). Therefore, the Wnt signaling pathway during injury must be kept in a tightly regulated state, with increased Wnt leading to depletion of progenitor cells and blockade of the pathway, holding progenitor cells in an undifferentiated state, unable to contribute to the repair process. The contribution of BASCs toward tissue regeneration after naphthalene injury is undefined and controversial. However, the contribution of each cell type in the tissue regeneration process may depend on the different injury stimuli or physical localization of the injured site within the lung. In our present study, we clearly demonstrate that SFRP1 can affect the differentiation of progenitor cells, and this finding is important regardless of the contribution of BASCs to each individual injury model.

During lung injury, several lung cell types participate in the repair process. These differing cell types maintain normal alveolar homeostasis through the secretion of various growth factors (HGF, ref. 3; KGF, refs. 4, 5; and VEGF, ref. 6) that promote cell survival and proliferation. For instance, the type II pneumocyte is differentiated into the type I pneumocyte, and it is thought to be the primary source of type I pneumocytes, with differentiation into the type I pneumocyte one of the main functions of the type II pneumocyte. On the other hand, at least with the current knowledge, BASCs are the cells whose primary function is served as the progenitor cell and differentiates into both alveolar lineage epithelial cells (type I and type II pneumocytes) and bronchiolar lineage epithelial cells (Clara cells and ciliated cells). They are considered the reserved cells (under a normal physiological maintenance program the commitment of these cells to the program is minimal). Therefore, the progenitor functions of type II pneumocytes and BASCs are quite different in their roles in vivo. To date, however, none of the known secreted factors are demonstrated to maintain the non-lineage-committed progenitor cells in the undifferentiated state (28). Our study suggests that SFRP1 is a critical regulator of this lung progenitor cell population during injury and demonstrates that deregulated inhibition of progenitor cells as a consequence of increased SFRP1 expression results in dysfunctional lung repair, as is seen in emphysema (11). In addition, loss of sFRP1 resulted in aberrant epithelial cell proliferation in two separate animal model systems, as is seen with the deregulated proliferation of progenitor cells contributing to lung fibrosis (26) and cancer (27). Therefore, the Wnt/SFRP signaling axis is a major new pathway involved in the pathogenesis of multiple lung diseases, and this study suggests that regulation of the pathway has the potential to allow repair of damaged lung tissue.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the Keio Gijuku Fukuzawa Memorial Fund for the Advancement of Education and Research (T.S.), an American Heart Association Established Investigator Award (J.D.), and U.S. National Institutes of Health grants R01 HL086936 (J.D.) and RC1 HL100384 (J.D.).

The authors thank Tina Zelonina and Tomoe Shiomi for technical assistance, and Professor Kiran Chada (Rutgers University, New Brunswick, NJ, USA) and Monica Goldklang (Columbia University) for critical reading of the manuscript.

This article includes supplemental data. Please visit http://www.fasebj.org to obtain this information.

- BASC

- bronchoalveolar stem cell

- BMP

- bone morphogenetic protein

- CD

- cluster of designation

- DAPI

- 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole

- FBS

- fetal bovine serum

- HE

- hematoxylin and eosin

- HGF

- hepatocyte growth factor

- IGF

- insulin-like growth factor

- IHC

- immunohistochemistry

- KGF

- keratinocyte growth factor

- PBS

- phosphate-buffered saline

- PCNA

- proliferating cell nuclear antigen

- PCR

- polymerase chain reaction

- PDGFRA

- α-type platelet-derived growth factor receptor

- RT-PCR

- reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction

- SAEC

- small airway epithelial cell

- SFRP

- secreted frizzled-related protein

- SP-C

- surfactant protein C

- TCF

- T-cell factor

- VEGF

- vascular endothelial growth factor

- WT

- wild type

REFERENCES

- 1. Bourbon J. R., Boucherat O., Boczkowski J., Crestani B., Delacourt C. (2009) Bronchopulmonary dysplasia and emphysema: in search of common therapeutic targets. Trends Mol. Med. 15, 169–179 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Tuder R. M., Yoshida T., Fijalkowka I., Biswal S., Petrache I. (2006) Role of lung maintenance program in the heterogeneity of lung destruction in emphysema. Proc. Am. Thorac. Soc. 3, 673–679 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Rubin J. S., Chan A. M., Bottaro D. P., Burgess W. H., Taylor W. G., Cech A. C., Hirschfield D. W., Wong J., Miki T., Finch P. W., Aaronson S. A. (1991) A broad-spectrum human lung fibroblast-derived mitogen is a variant of hepatocyte growth factor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 88, 415–419 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Panos R. J., Rubin J. S., Csaky K. G., Aaronson S. A., Mason R. J. (1993) Keratinocyte growth factor and hepatocyte growth factor/scatter factor are heparin-binding growth factors for alveolar type II cells in fibroblast-conditioned medium. J. Clin. Invest. 92, 969–977 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ulich T. R., Yi E. S., Longmuir K., Yin S., Biltz R., Morris C. F., Housley R. M., Pierce G. F. (1994) Keratinocyte growth factor is a growth factor for type II pneumocytes in vivo. J. Clin. Invest. 93, 1298–1306 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Sakurai M. K., Lee S., Arsenault D. A., Nose V., Wilson J. M., Heymach J. V., Puder M. (2007) Vascular endothelial growth factor accelerates compensatory lung growth after unilateral pneumonectomy. Am. J. Physiol. Lung. Cell. Mol. Physiol. 292, L742–747 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Imai K., D'Armiento J. (2002) Differential gene expression of sFRP-1 and apoptosis in pulmonary emphysema. Chest 121, 7S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Bodine P. V., Zhao W., Kharode Y. P., Bex F. J., Lambert A. J., Goad M. B., Gaur T., Stein G. S., Lian J. B., Komm B. S. (2004) The Wnt antagonist secreted frizzled-related protein-1 is a negative regulator of trabecular bone formation in adult mice. Mol. Endocrinol. 18, 1222–1237 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kurinna S. M., Tsao C. C., Nica A. F., Jiffar T., Ruvolo P. P. (2004) Ceramide promotes apoptosis in lung cancer-derived A549 cells by a mechanism involving c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase. Cancer Res. 64, 7852–7856 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kim C. F., Jackson E. L., Woolfenden A. E., Lawrence S., Babar I., Vogel S., Crowley D., Bronson R. T., Jacks T. (2005) Identification of bronchioalveolar stem cells in normal lung and lung cancer. Cell 121, 823–835 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Foronjy R., Imai K., Shiomi T., Mercer B., Sklepkiewicz P., Thankachen J., Bodine P., D'Armiento J. (2010) The divergent roles of secreted frizzled related protein-1 (SFRP1) in lung morphogenesis and emphysema. Am. J. Pathol. 177, 598–607 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Mahvi D., Bank H., Harley R. (1977) Morphology of a naphthalene-induced bronchiolar lesion. Am. J. Pathol. 86, 558–572 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Adamson I. Y., Bowden D. H. (1974) The pathogenesis of bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis in mice. Am. J. Pathol. 77, 185–197 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Selman M., Pardo A. (2006) Role of epithelial cells in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: from innocent targets to serial killers. Proc. Am. Thorac. Soc. 3, 364–372 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Zhang J., Li L. (2008) Stem cell niche: microenvironment and beyond. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 9499–9503 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Okita K., Ichisaka T., Yamanaka S. (2007) Generation of germline-competent induced pluripotent stem cells. Nature 448, 313–317 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Hyatt B. A., Shangguan X., Shannon J. M. (2002) BMP4 modulates fibroblast growth factor-mediated induction of proximal and distal lung differentiation in mouse embryonic tracheal epithelium in mesenchyme-free culture. Dev. Dyn. 225, 153–165 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Mei Y., Wang Z., Zhang L., Zhang Y., Li X., Liu H., Ye J., You H. (2012) Regulation of neuroblastoma differentiation by forkhead transcription factors FOXO1/3/4 through the receptor tyrosine kinase PDGFRA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 109, 4898–4903 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Hikake T., Hayashi S., Iguchi T., Sato T. (2009) The role of IGF1 on the differentiation of prolactin secreting cells in the mouse anterior pituitary. J. Endocrinol. 203, 231–240 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Giangreco A., Reynolds S. D., Stripp B. R. (2002) Terminal bronchioles harbor a unique airway stem cell population that localizes to the bronchoalveolar duct junction. Am. J. Pathol. 161, 173–182 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Rawlins E. L., Hogan B. L. (2006) Epithelial stem cells of the lung: privileged few or opportunities for many? Development 133, 2455–2465 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Rawlins E. L., Okubo T., Xue Y., Brass D. M., Auten R. L., Hasegawa H., Wang F., Hogan B. L. (2009) The role of Scgb1a1+ Clara cells in the long-term maintenance and repair of lung airway, but not alveolar, epithelium. Cell Stem Cell 4, 525–534 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Reynolds S. D., Zemke A. C., Giangreco A., Brockway B. L., Teisanu R. M., Drake J. A., Mariani T., Di P. Y., Taketo M. M., Stripp B. R. (2008) Conditional stabilization of beta-catenin expands the pool of lung stem cells. Stem Cells 26, 1337–1346 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Zemke A. C., Teisanu R. M., Giangreco A., Drake J. A., Brockway B. L., Reynolds S. D., Stripp B. R. (2009) beta-Catenin is not necessary for maintenance or repair of the bronchiolar epithelium. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 41, 535–543 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Wang R., Ahmed J., Wang G., Hassan I., Strulovici-Barel Y., Hackett N. R., Crystal R. G. (2011) Down-regulation of the canonical Wnt beta-catenin pathway in the airway epithelium of healthy smokers and smokers with COPD. PLoS One 6, e14793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Chilosi M., Doglioni C., Murer B., Poletti V. (2010) Epithelial stem cell exhaustion in the pathogenesis of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Sarcoidosis Vasc. Diffuse Lung Dis. 27, 7–18 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Garcia Campelo M. R., Alonso Curbera G., Aparicio Gallego G., Grande Pulido E., Anton Aparicio L. M. (2011) Stem cell and lung cancer development: blaming the Wnt, Hh and Notch signalling pathway. Clin. Transl. Oncol. 13, 77–83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Gotts J. E., Matthay M. A. (2012) Mesenchymal stem cells and the stem cell niche: a new chapter. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell. Mol. Physiol. 302, L1147–1149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.