Abstract

Oceanic iron (Fe) fertilization experiments have advanced the understanding of how Fe regulates biological productivity and air–sea carbon dioxide (CO2) exchange. However, little is known about the production and consumption of halocarbons and other gases as a result of Fe addition. Besides metabolizing inorganic carbon, marine microorganisms produce and consume many other trace gases. Several of these gases, which individually impact global climate, stratospheric ozone concentration, or local photochemistry, have not been previously quantified during an Fe-enrichment experiment. We describe results for selected dissolved trace gases including methane (CH4), isoprene (C5H8), methyl bromide (CH3Br), dimethyl sulfide, and oxygen (O2), which increased subsequent to Fe fertilization, and the associated decreases in concentrations of carbon monoxide (CO), methyl iodide (CH3I), and CO2 observed during the Southern Ocean Iron Enrichment Experiments.

Previous iron (Fe) fertilization experiments have been conducted in the North (1) and equatorial Pacific (2, 3) and in the Southern Ocean (4, 5). The Southern Ocean, the largest of the high-nutrient low-chlorophyll regions, represents 6% of the global ocean and has the potential to enhance carbon sequestration by Fe fertilization (6–9), which could slow carbon dioxide (CO2) accumulation in the atmosphere and potentially help alleviate global warming.

Experimental Methods

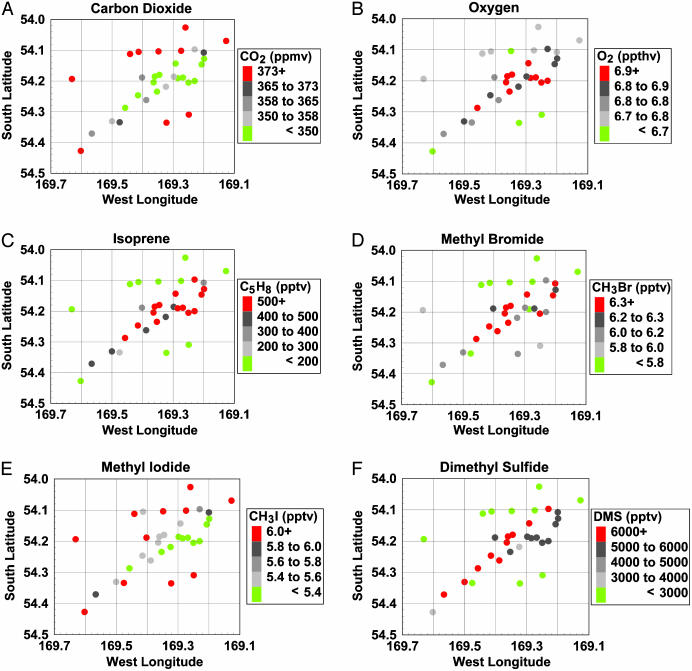

The experimental design and other results of the Southern Ocean Iron Enrichment Experiment (SOFeX) are presented in an overview paper (8). Of the two regions fertilized with Fe during SOFeX, we focus here on the region north of the Antarctic Polar Front. An area ≈15 × 15 km at 56.2°S, 172.0°W (southeast of New Zealand in the southwest Pacific sector of the Southern Ocean) was fertilized with a solution of acidified iron sulfate (FeSO4) over 48 h to a concentration of ≈1.2 × 10–9 mol·liter–1 (1.2 nM) beginning on January 12, 2002. The background Fe concentration ([Fe]) was ≈0.1 nM. A second (36 h) application of FeSO4 (≈1.2 nM) ended on January 17. These Fe additions were intended to simulate glacial era concentrations of iron in the Southern Ocean (8, 10). The region, or patch, was allowed time to bloom and then was surveyed over a 50-h period, between February 8 and 10, 4 weeks after the first Fe application. By this time the patch had reached a surface area that was a factor of 10 larger than during the initial Fe addition with iron concentrations in the patch of ≈0.3 nM (8). During this survey we approached the patch from the South working our way northeast, while crisscrossing the patch. After the shape and orientation of the patch became apparent [elongated and stretching from the southwest to the northeast (11)], more intensive sampling began along the patch. Observations of fluorescence, the partial pressure of CO2 in seawater (pCO2) (Fig. 1A), dissolved O2 (Fig. 1B), chlorophyll, and primary productivity indicated a pronounced change in biological activity in the mixed layer (upper 40–50 m), and the enhanced ocean color in the patch was visible from space (11). Correlations with CO2, O2, and fluorescence are used to indicate that the observed changes in trace gases, measured from surface water, were indeed associated with biological processes within the fertilized patch.

Fig. 1.

Concentration of dissolved gases measured in and around the fertilized patch. Surface-water measurements made 4 weeks after the initial iron fertilization. Note that the samples were taken over a period of 50 h.

Thirty-two whole air samples and 32 equilibrator samples were collected beginning February 8. Whole air was drawn from an inlet situated near the top of the bow mast, which was located ≈15 m above the average waterline. The air was drawn through 1/4′′ stainless steel tubing by a metal bellows pump operating at a rate of 15 liters/min at a back pressure of 1.5 atmospheres. The air traveled a distance of 80 m from the sample inlet to the laboratory located near the stern of the R/V Revelle. This air was used to fill individual 2-liter stainless steel sample flasks and to provide makeup gas for the equilibrator. A flow restrictor was used to allow for a 4-min integrated air sample. Care was taken not to sample air when the relative wind direction and speed indicated exhaust from the ships engines might be sampled. Such samples could not be entirely avoided, and data affected by the ship's exhaust were excluded. Ethene is an excellent marker of recent combustion. Seven of the 32 air samples had ethene mixing ratios two times its median value, indicating that some exhaust was sampled. Of these seven affected samples, one isoprene sample appears to be augmented (nearly twice the mixing ratio of the highest unaffected sample), one CO sample was clearly influenced (100 parts per 109 by volume), none of the methane samples were affected, one CH3Br sample may have been slightly augmented and was three standard deviations higher than the average, none of the CH3I samples were affected by exhaust, and no outliers were observed for dimethyl sulfide (DMS).

The equilibrator had been used on previous cruises by T. Takahashi (Columbia University, New York) and was a smaller version of the original Weiss design (12, 13). Two-liter equilibrator samples of dissolved gases were collected over an 18-min period at a constant rate by using an Entech Instruments (Simi Valley, CA) passive sampler. The water inlet was 5 m below the waterline near the port bow. Water flow from the ship's uncontaminated seawater system to the equilibrator was 4 liters/min.

Isoprene, CH3Br, CH3I, and DMS were analyzed at the University of California, Irvine, laboratory with a system employing five different gas chromatographic columns, each coupled to either a mass spectrometer detector, electron capture detector, or flame ionization detector (14, 15). CO and CH4 were quantified from a portion of the samples and were analyzed on separate systems (16, 17). The analytical accuracy was 1% for CH4, 5% for CO, CH3I, CH3Br, and isoprene, and 10% for DMS. The sampling/analytical precision of these compounds was estimated from the equilibrator measurements taken outside of the patch: the actual precision was better than 4% for isoprene, 2% for CH3Br, 3% for CH3I, 6% for DMS, 4% for CO, and 0.1% for methane. The whole-air samples were collected and analyzed to calculate the saturation anomalies (SAs) (Table 1). A positive SA implies a net flux from the ocean to the air. The patch produced a minimal effect on the air being sampled because the narrowness of the patch and the wind directions did not allow much time for contact with the patch. One DMS air sample did show some augmentation [182 parts per 1012 by volume (pptv), or greater than twice the median value] and one isoprene sample was 19 pptv (≥16 pptv above background), possibly attributable to the Fe fertilization.

Table 1. Statistics of dissolved gases sampled in and out of the fertilized patch.

| Equilibrator samples

|

||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| In-patch

|

Out-of-patch

|

R correlation coefficient

|

Air samples

|

|||||||||

| Compound | Average | SD | SA, %† | Average | SD | SA, % | Change, %‡ | O2 | Fluorescence | CO2 | Average | SD |

| O2, ppmv | 6,920 | 10 | 6,690 | 17 | 3.4 | 1 | 0.76 | -0.95 | ||||

| Fluorescence, V | 12.3 | 0.7 | 2.4 | 0.2 | 400 | 0.76 | 1 | -0.84 | ||||

| CO2, ppmv | 346 | 1 | 376.7 | 0.8 | -8.3 | -0.95 | -0.84 | 1 | ||||

| CH4, ppmv§ | 1.739 | 0.004 | 2.4 | 1.722 | 0.002 | 1.4 | 0.99 | 0.47 | 0.39 | -0.40 | 1.698 | 0.001 |

| CO*, ppbv§ | 860 | 60 | 1,900 | 1,790 | 80 | 4,200 | -52 | -0.69 | -0.91 | 0.83 | 42 | 0.5 |

| Isoprene, pptv | 560 | 13 | 38,000 | 139 | 6 | 9,300 | 300 | 0.89 | 0.88 | -0.97 | LOD¶ | |

| CH3Br, pptv | 6.5 | 0.1 | -1.5 | 5.7 | 0.1 | -14 | 14 | 0.49 | 0.64 | -0.62 | 6.6 | 0.1 |

| CH3I, pptv | 4.94 | 0.07 | 1100 | 6.4 | 0.2 | 1500 | -23 | -0.82 | -0.63 | 0.84 | 0.41 | 0.01 |

| DMS, pptv | 7,600 | 480 | 11,000 | 1,560 | 90 | 2,200 | 390 | 0.76 | 0.85 | -0.85 | 69 | 5 |

Ten samples were collected inside the patch, 10 were collected outside the patch, and 12 were collected on the gradient. Thirty-two air samples were collected concurrently with the equilibrator samples. Application of the Student's t test indicates that the O2, fluorescence, CO2, CH4, CO, isoprene, CH3Br, CH3I, and DMS distributions inside and outside of the patch are distinct at a confidence level of 99.5% or higher. All of the R values (from a simple pairwise regression) indicate that a statistical significance (>95% confidence) exists in the relationship between the two parameters. ppmv, parts per 106 by volume; ppbv, parts per 109 by volume.

In-patch criteria: O2 > 6,870 ppmv, CO2 < 350 ppmv, fluorescence > 10.6 V. Out-of-patch criteria: O2 < 6,730 ppmv, CO2 > 373 ppmv, fluorescence < 3.75 V. If a sample did not meet all three criteria for either in or out of the patch, it was not used in the table. However, these samples appear in Fig. 1.

The average SA, which is the average equilibrator mixing ratio (for either in or out of patch) divided by the average air mixing ratio minus one given in percent.

Percent change is equal to 100 × (in patch value minus out of patch)/out of patch.

Eighteen samples were analyzed for CO and CH4 in the fertilized region. Seven of these samples were collected in the patch and four were collected out of the patch.

Limit of detection at or below detection limit of 3 pptv. This was assigned a value of 1.5 pptv for the computation of SA.

Continuous in situ measurements of pCO2 in surface seawater were made by using a Li-Cor (Lincoln, NE) model 6262 CO2 analyzer. The system setup and equilibration were essentially identical to that described in ref. 18. Seawater pCO2 was sampled every 10 sec for 55 min of every hour. At the top of each hour, atmospheric, blank, and standard samples of three different concentrations were run for 1 min each, which enabled correction of trends in the data as a result of instrument drift or changes in system pressure. The surface water oxygen and fluorescence measurements were made using the standard instrumentation provided by The Scripps Institution of Oceanography aboard the R/V Revelle.

Results and Discussion

Isoprene is a very reactive compound that serves as a precursor of other organic molecules, contributes to aerosol formation, and is a sink for atmospheric oxidants. Marine isoprene production appears to be closely related to phytoplankton (19, 20) with supersaturated levels observed in surface seawater (21). Isoprene levels increased by a factor of four in the patch and were strongly correlated with productivity (CO2 uptake, O2, and fluorescence) (Fig. 1C and Table 1). The strong correlations of isoprene with biological indicators suggest that its production is dominated by processes associated with biological productivity. Nonmethane hydrocarbons (NMHCs) of marine origin can significantly impact the oxidative capacity of the natural atmospheric marine boundary layer, reacting with hydroxyl (HO) and atomic chlorine (22, 23). As a result, increases in NMHCs, such as isoprene, can increase the local lifetimes of short-lived gases, such as DMS, by competing for oxidants.

Of the trace gases in the atmosphere, CH4 and CO exert the greatest influence on the lifetime of HO (24), which in turn influences the abundance of compounds that have HO oxidation as a significant removal mechanism. Many of the compounds oxidized by HO, such as CH4 and CH3Br, contribute to global warming and/or stratospheric ozone depletion. Methane is the second most important greenhouse gas in terms of enhanced radiative forcing of Earth's climate since preindustrial times (25) and has a small oceanic source. On a relative basis CH4 was slightly elevated inside the patch versus the region surrounding the patch and correlated best with O2 (Table 1). However, on a per mole basis methane actually exhibited the greatest increase in comparison with isoprene, CH3Br, and DMS. The increase in the concentration of CH4 was likely the result of the initial digestion of the nascent phytoplankton biomass. Continued degradation of the organic matter likely produced additional CH4.

The dominant sources of atmospheric CO are from continental surfaces and the oxidation of atmospheric CH4 by HO. However, CO is both consumed and produced in ocean waters. The oceans are supersaturated in CO and, in regions where the overlying atmosphere is relatively unpolluted, they may contribute significantly to the local atmospheric concentration of CO (26). CO concentrations decreased by ≈50% in the patch, likely the result of increased bacterial consumption (direct chemical loss or air–sea flux would have affected both regions equally), and were correlated with fluorescence, CO2 uptake, and O2 (Table 1). A discernible diurnal cycle was not observed in the surface-water CO concentrations (nor for the other surface ocean gases reported here) as was observed in other marine environments (27–29). The source of oceanic CO is photolysis of dissolved organic matter (28, 30). Large diurnal amplitudes require fast acting sinks that are provided by microbial oxidation (27). However, Southern Ocean CO biological consumption rates are very low. Thus, little or no diurnal cycle was apparent in previous CO observations in the Southern Ocean (27). The reduction in CO, relative to the control area, was probably the result of steady consumption over the course of the experiment.

Overall, the Southern Ocean region south of 45°S is a net source of an estimated 2.4 Tg·year–1 (Tg = 1012 grams) of CO (29). This source can be compared to an estimated 10 Tg·year–1 of CO consumed photochemically in the atmospheric boundary layer (750 m above sea level and lower) over this region (Y. Wang, personal communication; ref. 31). Modeling results estimate the preindustrial CO consumption to be ≈4 Tg·year–1 for this portion of the troposphere (31). If a large portion of the Southern Ocean region were fertilized with Fe, either by design or naturally by increased aeolian dust, such that the concentrations created during SOFeX covered the entire Southern Ocean south of 45°S, the net flux of CO may be cut in half, increasing the amount of tropospheric HO, the main atmospheric oxidant for many gases. However, this effect would be dampened because of the 80-day summer lifetime of CO in the surface layer over the Southern Ocean {assuming a [HO] of 6.1 × 105 radicals per cm3 (23)}, in comparison with the 14-day exchange time of the atmospheric surface layer with the free troposphere (23). By using a version of the model we developed for a photochemical study over the Southern Ocean (23), the decrease in CO flux and increase in isoprene is estimated to result in a net 7% increase of [HO] to 6.5 × 105 radicals per cm3 in the summer Southern Ocean lower atmosphere.

Inside the patch, the CH3Br concentration increased (Fig. 1D), whereas CH3I showed a net loss in comparison with the control area (Fig. 1E) and CH3Cl remained unchanged. Methyl halides are known to be produced in seawater by marine microorganisms (32–35). Some methyl halides are known to be chemically removed from seawater by nucleophilic attack (36), hydrolysis (37), and bacteria (38–40). The observed decrease in CH3I was negatively correlated with CO2 uptake and O2 (Table 1). Before SOFeX, the only significant oceanic decay process of CH3I was believed to be nucleophilic attack by Cl–, but we suggest that the decrease in CH3I concentration was probably the result of increased microbial oxidation.

The increase of methyl bromide concentrations is not likely the result of abiotic oxidation of organic mater induced by the addition of Fe (41). Chloride is present at much higher concentrations than bromide in sea water, so oxidation would have resulted in significantly increased CH3Cl production, a phenomenon not observed during SOFeX. The weaker correlation of CH3Br with productivity may indicate a decoupling of the oceanic production and removal processes. However, the production term dominated, driving the saturation anomaly from negative to nearly neutral, meaning that the fertilized patch was no longer a sink for atmospheric CH3Br. Although some regions of the oceans are a major source of CH3Br, overall the oceans may be a net sink (42). Previous measurements in the Southern Ocean (43) show that it is an important sink for atmospheric CH3Br, a result of bacterial degradation (40), consuming ≈12 Gg·year–1 and representing 6% of the total estimated global sink (S. Yvon-Lewis, personal communication; refs. 42 and 45).

Methyl bromide is comparatively long-lived in the atmosphere (44, 45) (≈9 months) and constitutes about half of the atmospheric organobromine burden. Thus, CH3Br has a substantial impact on stratospheric ozone depletion. During the period 1994 through 1995, industrial usage of methyl bromide was ≈40 Gg·year–1 (46, 47) of the total methyl bromide production of 204 Gg·year–1 (45). If large-scale iron fertilization of the Southern Ocean were to occur, this significant CH3Br sink could be lost, which would offset reductions in agricultural and other industrial usage and result in an increase of ≈0.5 pptv in the global tropospheric methyl bromide mixing ratio. Because of the greater reactivity of bromine in the stratosphere relative to chlorine, this 0.5-pptv increase would be comparable with an ≈25 pptv increase in equivalent chlorine. Such an increase would delay the recovery of stratospheric ozone levels by ≈1 year.

Concentrations of DMS inside the patch were enhanced by nearly a factor of 5 with respect to the outlying region (Fig. 1F). DMS correlated well with fluorescence and CO2 uptake (Table 1). Of the volatile organic carbon gases measured during SOFeX, only DMS was quantified during previous iron fertilization experiments and was found to be enhanced in both the equatorial Pacific and Southern Ocean experiments (48). During SOFeX the response of DMS inside the patch was very similar to what was found previously for IronExII (48), although that experiment was conducted in the warm equatorial environment and observations lasted only 8 days. DMS is an important sulfur-containing trace gas (49) produced by phytoplankton (50, 51) and during the grazing of phytoplankton by microzooplankton (52). Emission of DMS from ocean waters is a major source of cloud condensation nuclei in the unpolluted marine environment. In the atmosphere, DMS is oxidized to sulfur dioxide, which can form sulfate aerosols. It is estimated that a net flux of 2.9 Tg of S per year from DMS oxidation originates from the Southern Ocean south of 40°S (M. Chin, personal communication; ref. 53). If this entire region were to respond as observed during SOFeX, the additional flux of DMS would result in a total emission of 14 Tg of S per year from the Southern Ocean region. This increase in S is comparable with the total global DMS emission estimate of 13 Tg of S per year. It is expected that this large amount of sulfur would result in a large increase in sulfate aerosol, resulting in an increased reflectivity of incoming solar radiation and leading to cooling. [It should be noted that the increase in albedo over the Southern Ocean would not scale linearly with the amount of additional DMS released because the increase in albedo, with respect to increased particles, is a very nonlinear process (54). Much of the nascent sulfuric acid formed from DMS oxidation is scavenged by sea-salt particles before being transported above the atmospheric boundary layer. The greatest probability for a DMS molecule to contribute to cloud formation occurs just after weather fronts clear the lower atmosphere of sea-salt particles. Because the production of cloud-forming particles from DMS is very episodic, it is difficult to assess the impact of iron fertilization on albedo.] Furthermore, increased aerosol acidity would allow greater dissolution, and therefore greater bioavailability, of Fe in aeolian dust (55) settling on the Southern Ocean, resulting in a positive feedback in DMS production and perturbations on other marine trace gases during glacial eras.

The changing concentrations of trace gases resulting from iron addition during SOFeX reveal some of the previously unknown or possible unintended consequences of artificial and glacial era iron fertilization on climate relevant trace gases, which are produced and consumed in the marine environment. Great uncertainties remain in the overall biochemistry of iron fertilization experiments that need to be addressed before any anthropogenic ocean fertilization efforts intended to sequester CO2 are undertaken on a massive scale. Future experimental and modeling studies are essential to determining whether benefits of carbon sequestration through intentional iron fertilization outweigh the negative perturbations to trace gases with relevance to climate and to stratospheric or local photochemistry. The changes in marine trace gases observed during SOFeX may not be representative of other marine ecosystems.

Acknowledgments

This article is dedicated to Murry McEachern, whose efforts in this project and many others were invaluable. We thank the crew and researchers aboard the R/V Revelle for a safe and successful research expedition, and Kenneth Coale, Ken Johnson, and Douglas Davis for comments and discussions. This work was supported by National Science Foundation Grant 0327198 and is part of the United States and International Surface Ocean and Lower Atmosphere Study.

Abbreviations: pptv, parts per 1012 by volume; SA, saturation anomaly; SOFeX, Southern Ocean Iron Enrichment Experiments.

References

- 1.Boyd, P. W., Law, C. S., Wong, C. S., Nojiri, Y., Tsuda, A., Levasseur, M., Takeda, S., Rivkin, R., Harrison, P. J., Strzepek, R. & Gower, J. (2004) Nature 428, 549–553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Coale, K. H., Fitzwater, S. E., Gordon, R. M., Johnson, K. S. & Barber, R. T. (1996) Nature 383, 495–501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cooper, D. J., Watson, A. J. & Nightingale, P. D. (1996) Nature 383, 511–513. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boyd, P. W., Watson, A. J., Law, C. S., Abraham, E. R., Trull, T., Murdoch, R., Bakker, D. C. E., Bowie, A. R., Buesseler, K. O., Chang, H., et al. (2000) Nature 407, 695–702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bakker, D. C. E., Watson, A. J. & Law, C. S. (2001) Deep Sea Res. Part II 48, 2483–2507. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sarmiento, J. L. & Orr, J. C. (1991) Limnol. Oceanogr. 36, 1928–1950. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chisholm, S. W. & Morel, F. M. M. (1991) Limnol. Oceanogr. 36, 1507–1511. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Coale, K. H., Johnson, K. S., Chavez, F. P., Buesseler, K. O., Barber, R. T., Brzezinski, M. A., Cochlan, W. P., Millero, F. J., Falkowski, P. G., Bauer, J. E., et al. (2004) Science 304, 408–414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Buesseler, K., Andrews, J., Pike, S. & Charette, M. (2004) Science 304, 414–417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mahowald, N., Kohfeld, K., Hansson, M., Balkanski, Y., Harrison, S. P., Prentice, I. C., Schulz, M. & Rodhe, H. (1999) J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 104, 15895–15916. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dalton, R. (2002) Nature 420, 722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Butler, J. H., Elkins, J. W., Brunson, C. M., Egan, K. B., Thompson, T. M., Conway, T. J. & Hall, B. D. (1988) NOAA Data Rep. ERL ARL 16, 104. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Johnson, J. E. (1999) Anal. Chim. Acta 395, 119–132. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sive, B. C. (1998) Ph.D. dissertation (Univ. of California, Irvine).

- 15.Colman, J. J., Swanson, A. L., Meinardi, S., Sive, B. C., Blake, D. R. & Rowland, F. S. (2001) Anal. Chem. 73, 3723–3731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lopez Palma, J. (2002) Ph.D. thesis (Univ. of California, Irvine).

- 17.Simpson, I. J., Blake, D. R., Rowland, F. S. & Chen, T. Y. (2002) Geophys. Res. Lett. 29, 10.1029/2001GL014521.

- 18.Friederich, G. E., Walz, P. M., Burczynski, M. G. & Chavez, F. P. (2002) Prog. Oceanogr. 54, 185–203. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Moore, R. M., Orem, D. E. & Penkett, S. A. (1994) Geophys. Res. Lett. 23, 2507–2510. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shaw, S. L., Chisholm, S. W. & Prinn, R. G. (2003) Mar. Chem. 80, 227–245. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Milne, P. J., Riemer, D. D., Zika, R. G. & Brand, L. E. (1995) Mar. Chem. 48, 237–244. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wingenter, O. W., Kubo, M. K., Blake, N. J., Smith, T. W., Jr., Blake, D. R. & Rowland, F. S. (1996) J. Geophys. Res. 101, 4331–4340. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wingenter, O. W., Blake, D. R., Blake, N. J., Sive, B. C. & Rowland, F. S. (1999) J. Geophys. Res. 104, 21819–21828. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Thompson, A. M. & Cicerone, R. J. (1986) J. Geophys. Res. 91, 10853–10864. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (1995) Climate Change, 21.

- 26.Johnson, J. E. & Bates, T. S. (1996) Global Biogeochem. Cycles 10, 347–359. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zafiriou, O. C., Andrews, S. S. & Wang, W. (2003) Global Biogeochem. Cycles 17, 10.1029/2001GB001638.

- 28.Bullister, J. L., Guinasso, N. L. & Schink, D. R. (1982) J. Geophys. Res. 87, 2022–2034. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bates, T. S., Kelly, K. C., Johnson, J. E. & Gammon, R. H. (1995) J. Geophys. Res. 100, 23093–23101. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zuo, Y. & Jones, R. D. (1995) Naturwissenschaften 82, 472–474. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wang, Y. & Jacob, D. J. (1998) J. Geophys. Res. 103, 31123–31135. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tokarczyk, R. & Moore, R. M. (1994) Geophys. Res. Lett. 21, 285–288. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Scarratt, M. G. & Moore, R. M. (1998) Mar. Chem. 59, 311–320. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Moore, R. M., Webb, M., Tokarczyk, R. & Wever, R. (1996) J. Geophys. Res. Oceans 101, 20899–20908. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Amachi, S., Kamagata, Y., Kanagawa, T. & Muramatsu, Y. (2001) Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 67, 2718–2722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Elliott, S. & Rowland, F. S. (1993) Geophys. Res. Lett. 20, 1043–1046. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Elliott, S. & Rowland, F. S. (1995) J. Atmos. Chem. 20, 229–236. [Google Scholar]

- 38.King, D. B. & Saltzman, E. S. (1997) J. Geophys. Res. Oceans 102, 18715–18721. [Google Scholar]

- 39.McDonald, I. R., Warner, K. L., McAnulla, C., Woodall, C. A., Oremland, R. S. & Murrell, J. C. (2002) Environ. Microbiol. 4, 193–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tokarczyk, R., Goodwin, K. D. & Saltzman, E. S. (2003) Geophys. Res. Lett. 30, 1808–1811. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Keppler, F., Eiden, R., Niedan, V., Pracht, J. & Scholer, H. F. (2001) Nature 409, 298–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yvon, S. A. & Butler, J. H. (1996) Geophys. Res. Lett. 23, 53–57. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lobert, J. M., Yvon-Lewis, S. A., Butler, J. H., Montzka, S. A. & Myers R. C. (1997) Geophys. Res. Lett. 24, 171–172. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Colman, J. J., Blake, D. R. & Rowland, F. S. (1998) Science 281, 392–396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.World Meteorological Organization (2003) Scientific Assessment of Ozone Depletion: 2002 (Global Ozone Research and Monitoring Project, Geneva), Report No. 47.

- 46.Wingenter, O. W., Wang, C. J., Blake, D. R. & Rowland, F. S. (1998) Geophy. Res. Lett. 25, 2797–2800. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Montzka, S. A., Butler, J. H., Hall, B. D., Mondeel, D. J. & Elkins, J. W. (2003) Geophys. Res. Lett. 30, 1826–1829. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Turner S. M., Nightingale, P. D., Spokes, L. J., Liddicoat, M. I. & Liss, P. S. (1996) Nature 383, 513–517. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Charlson, R. J., Lovelock, J. E., Andreae, M. O. & Warren, S. G. (1987) Nature 326, 655–661. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Turner, S. M., Malin, G., Liss, P. S., Harbour, D. S. & Holligan, P. M. (1988) Limnol. Oceanogr. 33, 364–375. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Keller, M. D., Bellows, W. K. & Guillard, R. L. (1989) in Biogenic Sulfur in the Environment, eds. Saltzman, E. S. & Cooper, W. J. (Am. Chem. Soc., Washington, DC), pp. 167–182.

- 52.Archer, S. D., Stelfox-Widdicombe, C. E., Burkill, P. H. & Malin, G. (2001) Aquat. Microb. Ecol. 23, 131–145. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Chin, M., Savoie, D. L., Huebert, B. J., Bandy, A. R., Thornton, D. C., Bates, S. T., Quinn, P. K., Saltzman, E. S. & De Bruyn, W. J. (2000) J. Geophys. Res. 105, 24689–24712. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Twomey, S. (1991) Atmos. Environ. 25, 2435–2442. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Meskhidze, N., Chameides, W. L., Nenes, A. & Chen, G. (2003) Geophys. Res. Lett. 30, 2085–2088. [Google Scholar]