Abstract

Purpose of review

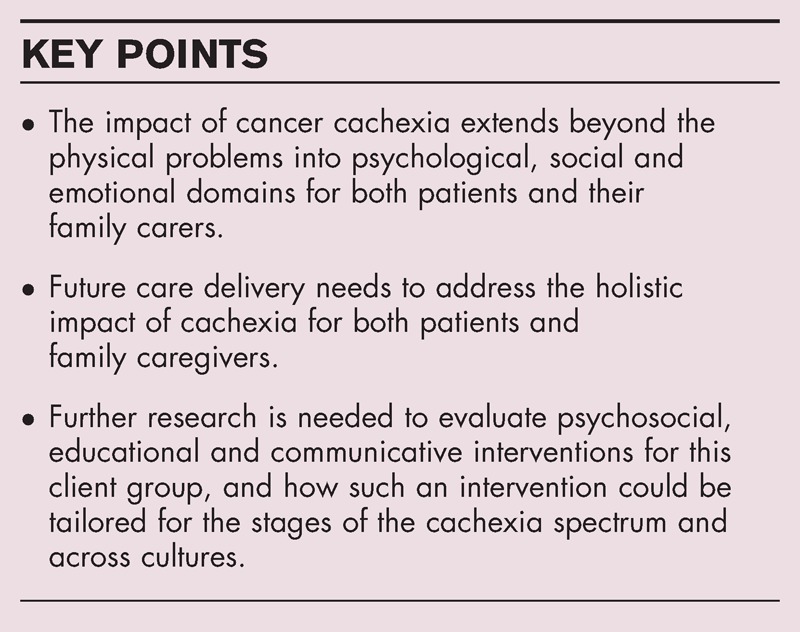

Cancer cachexia has a substantial impact on both patients and their family carers. It has been acknowledged as one of the two most frequent and devastating problems of advanced cancer. The impact of cachexia spans biopsychosocial realms. Symptom management in cachexia is fraught with difficulties and globally, there remains no agreed standard care or treatment for this client group. There is a need to address the psychosocial impact of cachexia for both patients and their family carers.

Recent findings

Patients living at home and their family carers are often left to manage the distressing psychosocial impacts of cancer cachexia themselves. Successful symptom management requires healthcare professionals to address the holistic impact of cancer cachexia. High quality and rigorous research details the existential impact of cachexia on patients and their family carers. This information needs to inform psychosocial, educational and communicative supportive healthcare interventions to help both patients and their family carers better cope with the effects of cachexia.

Summary

Supportive interventions need to inform both patients and their family carers of the expected impacts of cachexia, and address how to cope with them to retain a functional, supported family unit who are informed about and equipped to care for a loved one with cachexia.

Keywords: cancer cachexia, psychosocial, supportive healthcare intervention

INTRODUCTION

Cachexia is a devastating syndrome present in cancer, end-stage renal disease, congestive heart failure, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and many other chronic illness [1]. It has been acknowledged as one of the two most frequent and devastating problems of advanced cancer [2]. Globally, cancer cachexia is responsible for 2 million deaths annually and is known to severely impede the quality of life [3]. It is a complex multifaceted condition and although great advances have been made in understanding cachexia in the last 2 decades, there is a still a paucity of understanding the nuances of its pathophysiology. In consequence, there is currently no standardized treatment for the physical manifestations of cachexia and there is a gap in its clinical management [4▪]. This gap is not only in relation to the potential biological modalities, but also in terms of recognizing and responding to the psychosocial impact of cachexia for both patients and their family carers [5]. This review will focus on the latter aspect of the management of cachexia and discuss how supportive psychosocial, educational and communicative healthcare interventions for both patients and their family carers would help them better cope with the effects of cachexia.

Box 1.

no caption available

PSYCHOSOCIAL IMPACT OF CACHEXIA

Research has demonstrated the profound existential impact of cancer cachexia on both patients and their family caregivers. As such, we know that cachexia impact is multifaceted affecting biopsychosocial domains, and impacts on patients’ self-image, self-esteem and socialization because of altered appearance attributable to weight loss [2,6–9]. Additionally, cachexia impacts on the individual members of the patients’ family and on the family functioning [6]. Conflict over food has been reported as common and distressing for patients and their families, particularly as normalization of weight loss and lack of understanding of the patients’ altered appetite can result in the family trying to pressurize patients to eat more [7]. Harrowingly, patients have reported using tactics such as social isolation and lying to their family members to avoid such conflict, and family members have also reported feelings of guilt when arguing over their loved one's lack of food intake [8]. A recent systematic review of the psychosocial effects of cancer cachexia has demonstrated that the main causes of distress for both patients and their family carers are a lack of understanding about the irreversible and progressive nature of cachexia and the role of food in its management [10].

Cachexia assessment and management are often overlooked aspects of cancer [11]. Additionally, very little work has addressed how the psychosocial aspects of this syndrome can be better managed [12]. The European clinical practice guidelines for cachexia in advanced cancer highlight that the management of cachexia should address not only the physiological assault, but also the profound psychosocial impact on both patients and their family caregivers [13]. Indeed, such management approaches could incorporate a psychosocial, educational and communicative supportive healthcare intervention for both patients and their family caregivers. Such an intervention would aim to reduce the emotional burden associated with cachexia through empowering patients and family caregivers to understand the biological mechanisms of cachexia; the management of symptoms associated with cachexia, particularly related to feeding and nutrition; and ultimately help both patients and their family caregivers better cope with the effects of cachexia and improve their quality of life. Both patients and their family caregivers have voiced their desire to have such information [7,8] and as such it would inform evidence-based practice aimed at optimizing their care [14].

IMPORTANCE OF ADDRESSING THE NEEDS OF FAMILY CARERS AS WELL AS PATIENTS

It is unusual for people to go through the cancer experience alone. In fact, cancer is commonly referred to as a disease affecting the family who travel the cancer journey together [15–17]. Across the cancer journey, family members who become caregivers are known to provide the vast majority of home care [18–20]. It is common for family members to assume their role as ‘carer’ with little or very limited training and with limited resources within the cancer care setting to support them. Additionally, although intensely affected by a loved one's cancer diagnosis, family carers normally receive little attention [16]. As previously discussed, family members, who are also caregivers, have been involved in research which has highlighted their needs when caring for a loved one with cachexia [2,6–9,21▪].

With changes in healthcare and the focus on ‘care at home’, family caregivers of those with cancer cachexia will continue to provide the vast majority of patient care. Therefore, any intervention for cachexia management must address the needs of family caregivers in an efficient and economically viable fashion to ensure it is sustainable in today's fiscal healthcare climate. This will ensure the quality of life, and quality of care received by and within the family unit can be maximized. Involving family caregivers in such interventions is reflective of the wider literature in palliative care, which has highlighted that interventions to improve family caregiver support are required [22]. Furthermore, holistic care and acknowledging the patient and family as the ‘unit of care’ echoes the ethos of palliative care, suggested by the WHO [23]. Indeed clinical, academic and policy reasons for involving family carers in intervention-focussed research have been highlighted [24], reinforcing the need to focus on psychological well being and preparedness to give care for this population.

DEVELOPING PSYCHOSOCIAL, EDUCATIONAL AND COMMUNICATIVE INTERVENTIONS

Advances in technology can be an asset when developing interventions for this client group. Alongside the known difficulties in giving verbal or written information on complex health topics [25] within a cachectic population, patients’ health status may mean they cannot take part in group sessions which require the patient to travel frequently. Therefore, interventions using a multimedia format that can be delivered at a client selected appropriate time, such as in a digital video disk (DVD), maybe better received. Indeed, DVD interventions have been shown to be an effective medium to deliver information in a palliative cancer cohort [26]. Adopting a technology-based medium for delivery of such an intervention would, therefore, appear appropriate for a cachectic population. Such interventions are termed ‘complex’ because they require theoretical understanding of how it will benefit the intended audience. For example, in an intervention being developed for advanced cancer patients with cachexia and their family caregivers, the aim of such research could be to enable patients and their family caregivers to cope with the psychosocial stressors affecting them as a result of cachexia. Therefore, it would be appropriate for a psychoeducational intervention addressing such issues to be underpinned by Lazarus and Folkman's Coping and Adaption Theory [27]. This aims to facilitate effective coping, thereby improving the patients’ and family caregivers’ overall quality of life. Additionally, such an intervention is termed ‘complex’ as it is targeted at supporting difficult behaviours (e.g. normalization of weight loss associated with cachexia). These facets of developing such an intervention cannot be underestimated, as lack of due attention to these has been cited as one of the main reason why complex healthcare interventions fail [28]. Therefore, the adoption of a guiding model when developing a supportive healthcare intervention for cachexia management is seen as a prerequisite: for example, the Medical Research Council (MRC) complex intervention–evaluation framework [29]. In the case of developing an intervention for both patients and family caregivers in relation to cachexia, this framework emphasizes the need to undertake and be reactive to preclinical work ascertaining their needs. This work has been conducted as we now have a substantial body of knowledge detailing the psychosocial needs of this client group [10]. In moving through the remaining stages of the framework, it is pertinent to ensure that this work is acknowledged and that theory-driven interventions are developed and tested which recognize and respond to the needs identified, to ensure such interventions are fit for purpose [21▪]. Importantly, evaluation of complex interventions is based in the context of ‘everyday practice’. Thus, any future intervention must be easily incorporated into the routine care and needs to be developed with not only the client group, but also the care providers to ensure both applicability and also sustainability in the current economic climate and resources available within the healthcare setting.

CURRENT AND FUTURE WORK

There is currently no standardized treatment to alleviate cachexia and improve survival. However, addressing the psychosocial aspects of this syndrome may at least improve the quality of life for both patients and their family carers. It is clear that the multidimensional impact of cachexia spans biopsychosocial domains and it affects not only the patients, but also their family carers. Nonetheless, the development and evaluation of psychosocial, educational and communicative interventions for patients with cachexia and their family carers remains in its infancy.

One study employed a mixed methods design which examined the effect of a nurse-delivered psychosocial intervention for weight and eating distress in family carers of patients with advanced cancer [9]. Results of this UK-based study indicated that the intervention which included the provision of information and support in self-management had a positive effect on the lives of carers. Indeed, the recorded change in the intensity of carer weight-related distress in the intervention group was statistically significant. Furthermore, qualitative findings from the mixed methods study provided compelling evidence to further support the potential use for such an intervention. However, we should be cautious in interpreting these results as the authors acknowledge a number of limitations in their study including small sample size, nonrandom allocation of participants, baseline differences between both groups and the possibility that the experimental group received the intervention prior to baseline data collection. Further research is required to support these initial positive results. These results are reflective of the international expert consensus on the potential of psychosocial, educational and communicative interventions to address the psychosocial impact of cancer cachexia for both patients and their families [12,30]. Acknowledging this work, a current multisite randomized control trial is running and open to recruitment in the United Kingdom, evaluating a psychoeducational intervention for patients with advanced cancer who have cachexia and their family carers [21▪]. This is the first study to develop and evaluate a psychoeducational intervention for both patients and carers. However as recruitment is ongoing, we await results from this study.

It is noteworthy that trial development and evaluation of psychosocial, educational and communicative interventions has only been conducted in the United Kingdom. There is therefore a need to ascertain whether such an intervention has international relevance, and to examine and address any cultural variances amongst differing global populations. The focus of such an intervention with this client population, regardless of the geographical location, will remain on food consumption, weight loss and family care. However, a next step is to examine whether and how this varies across different cultural contexts [31]. The test of such an intervention will, therefore, be on not only the effectiveness of the intervention, but also the replicability in light of contextual cultural factors.

The defining characteristics of cancer cachexia are more developed than cachexia in others chronic illness. For example, not only has a consensus definition of cancer cachexia been developed [32], but also a classification system for cachexia in cancer has also been proposed. This has three distinct stages on a spectrum ranging from precachexia, cachexia and through to refractory cachexia [32]. Therefore, future psychosocial, educational and communicative interventions could be tailored to each stage of the cachexia journey. This is pertinent as key information, in relation to the treatment options and particularly the role of food (and nutritional supplements) in the management of cachexia, will change across the precachexia, cachexia and refractory cachexia continuum. This is supportive of the current pharmacological treatment intervention studies which recommend that interventions for cancer cachexia should be stage specific and use the classification system to guide treatment options [33]. This is because those individuals who are at an earlier stage of the classification system (precachexia) have the potential to be more responsive to biological treatment than those at the latter stages (refectory) of cachexia. However, the complexity of this must also be acknowledged as there are currently no clinically viable markers to easily classify patients across the three stages of cachexia, particularly from cachexia to refractory cachexia. Therefore, with a lack of pragmatic, therapeutically meaningful indicators, clinical diagnosis remains problematic within this patient group.

CONCLUSION

With increasing understanding of the holistic impact of cancer cachexia and no current standardized treatment for the biological management of cachexia, incorporating a psychosocial, educational and communicative intervention into cachexia management would be advantageous to both patients and their family carers. This would help ensure clinical and academic work is progressing towards patient-centred outcomes, which reflect not only the quantity, but also the quality of life. Such interventions should work to facilitate better communication with patients who have cachexia and their families, both within their family unit and with healthcare professionals. Ideally, such intervention should be stage specific across the cachexia spectrum to tailor information to precachexia, cachexia and refractory cachexia cohorts. This may help to reduce the burden to both patients and their families through providing better understanding and support during the patient's cachexia journey.

Acknowledgements

None.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES AND RECOMMENDED READING

Papers of particular interest, published within the annual period of review, have been highlighted as:

▪ of special interest

▪▪ of outstanding interest

REFERENCES

- 1.Von Haehling S, Anker SD. Cachexia as a major underestimated and unmet medical need: facts and numbers. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 2010; 1:1–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McClement S. Cancer anorexia–cachexia syndrome: psychological effect on the patient and family. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs 2005; 32:264–268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Burckart K, Beca S, Urban RJ, Sheffield-Moore M. Pathogenesis of muscle wasting in cancer cachexia: targeted anabolic and anticatabolic therapies. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care 2010; 13:410–416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4▪.Douglas E, McMillan DC. Towards a simple objective framework for the investigation and treatment of cancer cachexia: The Glasgow Prognostic Score. Cancer Treat Rev 2014; 40:685–691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This study proposes a novel scoring system to create a simple objective framework for the identification and treatment of cancer cachexia. In order to advance the management of cachexia, identification of it in clinical practice is a necessity. The work proposed by these authors aims to progress this by proposing what constitutes cachexia in cancer.

- 5.Millar C, Reid J, Porter S. Refractory cachexia and truth-telling about terminal prognosis; a qualitative study. Eur J Cancer Care 2013; 22:326–333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Reid J, McKenna H, Fitzsimons D, McCance T. The experience of cancer cachexia: a qualitative study of advanced cancer patients and their family members. Int J Nurs Stud 2009; 46:606–616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Reid J, McKenna H, Fitzsimons D, McCance T. An exploration of the experience of cancer cachexia: what patients and their families want from healthcare professionals. Eur J Cancer Care 2010; 19:682–690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Reid J, McKenna H, Fitzsimons D, McCance T. Fighting over food: patient and family understanding of cancer cachexia. Oncol Nurs Forum 2009; 36:439–445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hopkinson JB, Fenlon DR, Foster CL. Outcomes of a nurse-delivered psychosocial intervention for weight- and eating-related distress in family carers of patients with advanced cancer. Int J Palliat Nurs 2013; 19:116–123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Oberholzer R, Hopkinson JB, Baumann K, et al. Psychosocial effects of cancer cachexia: a systematic literature search and qualitative analysis. J Pain Symptom Manage 2013; 46:77–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mauri D, Tsiara A, Valachis A, et al. Cancer cachexia: global awareness and guidelines implementation on the web. BMJ Support Palliat Care 2013; 3:155–160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vaughan VC, Martin P, Lewandowski PA. Cancer cachexia: impact, mechanisms and emerging treatments. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 2013; 4:95–109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Radbruch L, Elsner F, Trottenberg P, et al. Clinical practice guidelines on cancer cachexia in advanced cancer patients. Aachen: Department of Palliative Medicinen/European Palliative Care Research Collaborative; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Porter S, Millar C, Reid J. Cancer cachexia care: the contribution of qualitative research to evidence-based practice. Cancer Nurs 2012; 35:E30–E38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hopkinson J, Brown J, Okamoto I, Addington-Hall J. The effectiveness of patient–family carer (couple) intervention for the management of symptoms and other health-related problems in people affected by cancer: a systematic literature search and narrative review. J Pain Symptom Manage 2012; 43:111–142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Given BA, Given CW, Sherwood PR. Family and caregiver needs over the course of the cancer trajectory. J Support Oncol 2012; 10:57–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kim Y, Given BA. Quality of life of family caregivers of cancer survivors. Cancer 2008; 112:2556–2568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Levine C, Halper D, Peist A, Gould D. Bridging troubled waters: family caregivers, transitions, and long-term care. Health Aff (Millwood) 2010; 29:116–124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Given B, Sherwood PR. Family care for the older person with cancer. Semin Oncol Nurs 2006; 22:43–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Institute of Medicine (IOM). Retooling for an aging America: Building the Healthcare Workforce 2008. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21▪.Reid J, Scott D, Santin O, et al. Evaluation of a Psychoeducational intervention for patients with Advanced Cancer who have Cachexia and their lay Carers (EPACaCC): study protocol. J Adv Nurs 2013; http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/jan.12268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This study discusses the first psychoeducational DVD for patients with cancer cachexia and their family carers, currently being tested in a randomized controlled trial. Results from this study will make a significant contribution to knowledge and understanding in this area and will inform education, practice and policy.

- 22.Hudson P, Payne S. Family caregivers and palliative care: current status and agenda for the future. J Palliat Med 2011; 14:864–869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.World Health Organisation. http://www.who.int/cancer/palliative/definition/en/ [Accessed 23 June 2014]. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hudson P, Aranda S. The Melbourne family support program: evidence-based strategies that prepare family caregivers for supporting palliative care patients. BMJ Support Palliat Care 2013. 1–7doi:10.1136/bmjspcare-2013-000500 [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wilson EA, Makoul G, Bojarski EA, et al. Comparative analysis of print and multimedia health materials: a review of the literature. Patient Educ Couns 2012; 89:7–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Capewell CMR, Gregory W, Closs SJ, Bennett MI. Brief DVD-based educational intervention for patients with cancer pain: feasibility study. Palliat Med 2010; 24:616–622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lazarus R, Folkman S. Stress, appraisal, and coping. New York: Springer Publishing Co; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Campbell M, Murray E, Darbeyhire J, et al. Designing and evaluating complex interventions to improve healthcare. BMJ 2007; 334:455–459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Medical Research Council. A framework for the development and evaluation of RCTs for complex interventions to improve health. London: Medical Research Council; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fearon K, Strasser F, Anker SD, et al. Definition and classification of cancer cachexia: an international consensus. Lancet Oncol 2011; 12:489–495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Counihan C, Van Esterik P. Food and culture: a reader. 3rd ed.New York: Routledge; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fearon KCH. Cancer cachexia: developing multimodal therapy for a multidimensional problem. Eur J Cancer 2008; 44:1124–1132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Blum D, Stene GB, Fayers P, et al. Validation of the consensus definition for cancer cachexia and evaluation of a classification model – a study based on data from an international multicentre project (EPCRC-CSA). Ann Oncol 2014; doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdu086. [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]