Abstract

The literature on integrated care is limited with respect to practical learning and experience. Although some attention has been paid to organizational processes and structures, not enough is paid to people, relationships, and the importance of these in bringing about integration. Little is known, for example, about provider engagement in the organizational change process, how to obtain and maintain it, and how it is demonstrated in the delivery of integrated care. Based on qualitative data from the evaluation of a large-scale integrated care initiative in London, United Kingdom, we explored the role of provider engagement in effective integration of services. Using thematic analysis, we identified an evolving engagement narrative with three distinct phases: enthusiasm, antipathy, and ambivalence, and argue that health care managers need to be aware of the impact of professional engagement to succeed in advancing the integrated care agenda.

Keywords: Europe, Western; health care; health care professionals; relationships, health care; research, qualitative

A number of integrated care initiatives are ongoing in health care systems in the United Kingdom, continental Europe, the United States, Australia, and New Zealand (Øvretveit, Hansson, & Brommels, 2010; Rosen, Lewis, & Mountford, 2011; S. Shaw & Levenson, 2011; Trivedi & Grebla, 2011). These initiatives reflect a growing awareness that existing care models, tending to be siloed and fragmented, are no longer adequate to meet the needs of a growing elderly population with complex, multiple health needs (Ham & Curry, 2011; Lewis, Rosen, Goodwin, & Dixon, 2010; Powell-Davies et al., 2006). The ethos behind integrated care is to put patients first and empower health professionals through improved coordination of care among specialists, general practitioners (GPs), and social care services (Goodwin et al., 2012; Ham & De Silva, 2009), with the ultimate goal of improving health outcomes and reducing health care costs. Although there is a growing body of literature that describes effective integration elements and approaches (Goodwin et al., 2012; Light & Dixon, 2004; Shapiro & Smith, 2003), literature on practical learning and experience from the United Kingdom is limited (RAND Europe and Ernst & Young, 2012). Considerable attention has been paid to organizational processes and structures, but little is known about the perceptions and experiences of health care providers working in the integrated care setting, in particular, how the perceived reasons for their engagement as providers of care, or the implications of these, play out in the implantation and delivery of integrated health and social care.

In the health care sector, greater staff engagement in planning, commissioning, and development of services is crucial in ensuring that service changes are properly planned and effectively implemented (Richman, 2006; Spurgeon, Clark, & Ham, 2011). Enhanced staff engagement is thought to lead to clearer benefits for patients, better health care outcomes, and value for money (Bakker & Schaufeli, 2008; Clark, 2012; MacLeod & Clarke, 2009). However, in the United Kingdom, initiatives aimed at improving quality of care have not generally succeeded in securing full engagement of health care professionals (Gollop, Whitby, Buchanan, & Ketley, 2004; Jorm & Kam, 2004; Shekelle, 2002). Many factors are thought to interact to facilitate or inhibit engagement, and there are likely to be subtle differences in how to best harness the interest and involvement of each professional.

In the integrated care context, securing engagement is even more complex, because of the challenges inherent in collaborative working across professional boundaries and different organizations. Overcoming these challenges has proved to be difficult both in the United Kingdom and in the United States. The experience from United States suggests that professional beliefs and values present significant obstacles to creating culture of change. For instance, Gitterman, Weiner, Domino, Mckethan, and Enthoven (2003) argue that, for the Kaiser Permanente model to succeed, a set of wider socioeconomic and political factors had to be in place to enable the internal cultural drivers. Similarly, Sidorov (2003) shows how an attempt to merge hospital systems was unsuccessful because of the wrong management techniques resulting from underestimating the role of cultural differences between the two organizations. Because integrating health and social care requires changes in behavior and practice, it is important to understand which factors drive and affect the engagement of professionals in delivering improvements in quality and better health care outcomes.

In this article, we explore health care professionals’ engagement in implementing and delivering integrated health and social care as part of a large-scale integrated care pilot (ICP) in North West London, UK. To illuminate the dynamics of this engagement, we are informed by Saks (2006), who described engagement as “a distinct and unique construct consisting of cognitive, emotional, and behavioral components . . . associated with individual role performance” (p. 602). For Saks, engagement was experienced emotionally and cognitively and could be demonstrated behaviorally. Following Kahn (1990), Harter, Schmidt, and Hayes (2002), and Schaufeli, Salanova, Gonzalez-Roma, and Bakker (2002), Saks conceptualized engagement as an absorption of resources and the degree to which one is attentive to one’s work. For engagement to occur, employees need physical, emotional, and psychological resources (K. Shaw, 2005). Cognitive resources relate to employees’ beliefs, working conditions, and leaders; emotional resources concern how employees feel about each of those three factors and whether they have positive or negative attitudes toward the organization and its leaders; behavioral resources concern the physical energy displayed and exercised by individuals in undertaking their roles (Harter et al., 2002; Maslach & Leiter, 2001). Seen from this perspective, engagement is understood as the extent to which people perform their own work role and is related to their emotional experiences (May, Gilson, & Harter, 2004; Saks, 2006).

Drawing on the qualitative evaluation of the North West London ICP, we examined the work that was carried out to achieve each of the engagement components. We explored the ways in which professionals articulated their engagement and used this to illuminate the wider organizational phenomena in play. We observed that the emotional responses evoked from the constructed interactions and relationships between health care providers and the pilot’s management team were manifested behaviorally in ways that affected providers’ participation in the planning, implementation, and delivery of integrated care. Therefore, we see engagement as a construct that provides an understanding of processes that are internal to professionals but are observable and manifested in their behaviors. These behaviors are influenced and represented by professionals’ norms, rules, values, and attitudes, and enable a picture to be built up of the way people work and interact to implement and deliver integrated care.

We acknowledge that engagement is a construct that needs to be problematized. However, we argue that its ambiguous conceptual foundation does not necessarily undermine the importance of examining engagement, but rather that there is a need for further inquiry into what engagement means in large-scale health care transformations, and to consider all of the dynamics surrounding how individuals and their organizations perceive engagement (Luisis-Lynd & Myers, 2010). Whether referring to specific components of integrated care or to the full experience, health care providers exert a critical role in creating conditions conducive to the success of bringing about change. This role can be referred to as engagement. Through a review of the literature and discussions of emerging findings from our research, and using in-depth qualitative methods, we explored primary care GPs’ and hospital consultants’ (HCs) own perceived and enacted engagement as providers of care in an integrated care context.

The North West London ICP

The population in North West London is one of the fastest growing and socioeconomically diverse in the United Kingdom, with significant inequalities in life expectancy and disease prevalence between different ethnic groups. The area is also characterized by a higher than average prevalence of diabetes (35% of the population), mainly in groups of Indian subcontinent and African Caribbean origin (Harris et al., 2012). The North West London ICP is a large-scale innovative program linking nearly 100 general practices, three community service providers, two mental health providers, two acute providers, and five local authorities. Designed to facilitate improvement in the care of more than 500,000 registered patients, the ICP is grounded in five principles: invest to save, shift care from acute care to community, raise the quality of patient care, population-based approach, and alignment of incentives and information and governance (National Health Service [NHS] North West London, 2011). At a strategic level, the ICP is driven by the Integrated Management Board (IMB), five supporting committees, and the operations team that provides day-to-day support (for a more detailed description of the pilot, see Harris et al., 2012).

At the heart of the ICP lie specifically established financial and governance arrangements, multidiscip-linary groups (MDGs), and a new information technology (IT) tool. The MDG meetings involve representatives from the ICP provider organizations, such as GPs, acute providers, mental health care, community nursing, social care, and other allied health care professionals. The primary purpose of these groups is to meet regularly to discuss care of a selected group of patients, and learn more about the local health services and their remits (Harris et al., 2012). MDGs are chaired by GPs, but managed and run by MDG coordinators, whose role is to be the first-line contact point for all stakeholders and to work with MDG members to identify areas where there are bottlenecks in the clinical pathway and map solutions. Care for patients is managed via structured care plans, which are agreed between the health care provider (usually a GP) and a patient. The implementation of the care plans can be monitored and guided through the IT tool, which enables collaborating partner organizations to share, manipulate, store, and analyze patient data. Specifically, the IT tool enables the extraction of patient data, performance management, referral support, as well as care planning and risk stratification.

Method

Background

This research formed part of a larger mixed-method evaluation of the ICP (see Curry et al., 2013; Greaves et al., 2013). The findings reported here are derived from the qualitative evaluation of providers’ perceptions and experiences. A total of 25 semistructured interviews, four focus groups with key informants, and more than 65 hours of non-participant observations of the pilot’s committee meetings were carried out between January and June 2012, following ethics research committee approval from the NHS National Research Ethics Service for City and East London (ref. 11/LO/1918), UK, in accordance with the harmonized Governance Arrangements for Research Ethics Committees (GAfREC). Consent to support and take part in activities within the ICP contributing to its evaluation was part of the agreement in organizations being involved in the pilot. Although consent was implicit in our being invited to undertake the evaluation at the MDG meetings, to ensure we met best practice standards, we sought and obtained verbal consent from the individual professionals who were present; however, there was no specific ethical requirement to do so, nor to obtain written consent.

Non-Participant Observations

We used non-participant observation to inform the design of the interview and focus group guides and to help answer the more descriptive research questions of the evaluation (DeWalt & DeWalt, 2002). It provided early lessons on the perceptions and experiences of health care professionals, permitting us to check the definitions of terms that participants used in interviews and focus groups, and to get a feel for how activities were organized and prioritized in the pilot (Marshall & Rossman, 1995). We followed Spradley’s (1980) framework for carrying out participant observation that allowed us not only to consider the pilot as a whole but also to make more selective and focused observations from meetings. The data from non-participant observations, mainly in the form of field notes, excerpts, and quotations from participants, were coded according to the primary participant and the type of the meeting observed.

Semistructured Interviews

We adopted a purposive sampling strategy, with knowledge of the group used to select representative subjects (Berg, 1995), and contacted providers via email and/or telephone to invite them to take part in the interview. We interviewed 25 providers, including GPs, general practice nurses, community matrons, mental health representatives, social workers, and practice managers. Thematization of questions and probes for the interview guide emerged from three sources:

the relevant literature,

previous non-participant observations, and

our experience and involvement in interventional and public health.

The questions were designed to explore providers’ experiences of delivering the pilot, the perceived impact of the pilot, interactions with other professional groups and organizations, and implications for the wider health care system. Interviews lasted between 25 and 45 minutes each, and were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim by a professional company providing medical transcription services.

Focus Groups

We conducted four focus groups in total, each lasting approximately 1 hour. They were undertaken with members of multidisciplinary groups and contained a mix of professionals including GPs, HCs, general practice and community nurses, mental health representatives, social workers, and primary and secondary care managers. Each focus group contained between four and nine professionals. Following Krueger and Casey (2000), the focus groups were facilitated by a moderator and accompanied by other members of the evaluation team. As with the interviews, the focus group data were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim by a professional company providing medical transcription services.

Data Analysis

We analyzed data thematically, using constant comparison (Glaser & Strauss, 1967) within a modified framework approach (Richie & Spencer, 1994). Two experienced qualitative researchers (Ignatowicz and Greenfield) independently coded the data from the interviews, focus groups, and notes from non-participant observations. Codes were created both horizontally (by coding each interview or focus group as a standalone hermeneutic unit) and vertically (by scanning across the data for specific terms), and then developed into categories and themes. Categories were refined and coding reviewed throughout the process for which the ATLAS software (Scientific Software Development, 1999) was used. In reporting the findings, we used direct quotes from participants, but these have been anonymized in view of the relatively small number of participants that the research drew from. In this article, we focus on the views of GPs and HCs, because these represented the largest cadre of health care professionals in the pilot.

Findings

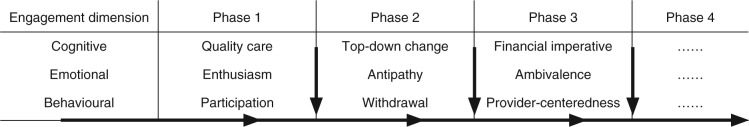

We identified an evolving engagement process with three relatively distinct phases: enthusiasm, antipathy, and ambivalence, which were reflected by cognitive, emotional, and behavioral elements. In the early stages of the pilot, providers were enthused by the vision to improve quality of care for their patients and demonstrated willing involvement and participation. Subsequently, when the pilot management shifted toward service efficiency and reorganization, providers became antipathetic toward the pilot and began to withdraw their participation. Later on, as financial gains became a dominant narrative, the remaining providers became ambivalent toward the pilot, and attentive mostly to the financial gains that the pilot could bring to their own service. These three phases appeared to be inter-dependent; however, their effective management was likely to be critical for sustainable improvements in quality, performance, and cost-effectiveness.

Quality Care Narrative Leads to Keen Participation

In the set-up stages of the pilot, a strong quality of care narrative was important in securing engagement and buy-in of GPs and HCs. Respondents reported that the vision of improving patient care was an important factor in influencing their decision to sign up. They told us that, because of the fragmentation of the health care system in the United Kingdom, single agencies are not well placed to resolve difficulties inherent in providing comprehensive care required by people with complex conditions and multiple needs:

You know, certainly in London, with diabetes, you cannot have everyone being looked after by a specialist in secondary care. It makes no financial sense, it doesn’t make good medical sense, so clearly you need to be integrated with a level you can fast-track people up and down the system and access the system when need be. (HC)

Organizations providing health care to patients with long-term conditions needed to change, and for our respondents, integrated care was the “next logical step” and the “natural choice.” GPs and consultants agreed that the principles of patient-centered care, which is tailored to the individual needs of a patient, are noble and timely. We heard that improving quality of care should be at the forefront of the pilot’s agenda and that the vision of providing patient-centered care, despite often competing priorities, seemed important in motivating professionals to work together. Some GPs and consultants indicated that they initially had taken a wait-and-see attitude to determine whether the pilot was just another temporary initiative; others talked about “reinventing the wheel.” The consultants in particular mentioned that similar initiatives had already been undertaken in their organizations, and with varying results. Nonetheless, their concern for efficiency and quality of care, a narrative that was disseminated consistently and coherently by the pilot’s management team, led most to buy in to the pilot as a potential improvement over current ways of working:

Working in the job that I do . . . I see the end product of poorly integrated care, I see the end product of . . . I’ll go onto a medical ward and I’ll see somebody whose diabetes is being cared for, but they’re ignoring their [any comorbidity] . . . because physicians are so siloed now, they’ll be ignoring the other things or they’ll be ignoring their psychiatric care. So I really see at this end how siloed care has become . . . integrated care is really important. (HC)

Both GPs and consultants agreed that this afforded the momentum and a framework to bind the professionals together, to secure initial buy-in, and provided an enabling environment for the pilot to develop.

Top–Down Organizational Change Leads to Antipathetic Withdrawal

The transition from buy-in to implementation proved to be more challenging. The pilot was designed and implemented at a time when the full extent of the financial challenges in the British NHS was becoming apparent and there was a need to achieve significant savings in North West London. The vision and shared values of providing patient-centered care were still seen as important, but an over-arching economic and political imperative emerged that began to affect providers’ perceptions of the pilot’s objectives. Some hospital executive’s interests in the pilot began to contrast with the views of the health care providers who were actually delivering the integrated care:

It was seen as a bit of a, we’ve got to do this, I’ve got to be honest, and I think our kind of executive is very, is very keen on this. So whether that’s for political reasons or ideological reasons, I do not know, but it seemed to be a very good thing to be involved in. I think for those on the ground, I think we’ve got slightly different views about that. (HC)

Health care providers began to think that this was top–down politics, implemented by NHS executives who were required to meet tight budgets and timescales. As a result, many providers felt a strong sense of top–down decision-making precluding the possibility of full ownership in the pilot:

Well, I do not think I was given much choice about going into it. The consultant here actually went on long-term sick leave, and this is one of the things that he had been involved in. So I kind of ended up being involved by default really . . . so I, kind of, just got a list of dates—hundreds of dates—thrust at me and said, you need to, you need to go to these. That’s how I got involved. (HC)

This was often described as creating tension or antipathy. Providers began to feel that they were being “dragged” into the pilot:

They are massively missing the trick, because at the moment, it’s like we’re horses and they’re dragging us to water and the more they drag me, the less I will actually drink. They have to, they have to make it easy for me to want to make it work, and that’s the opposite of what I feel they’re doing at the moment. (GP)

Communication in particular seemed to be a key consideration of GPs when discussing the pilot. Comments ranged from discontentment with lack of feedback and rigor about performance to emotional frustration about the style of leadership. Many also felt that there was a disconnection between the governance decisions of IMB and the work in practice:

I just think we [GPs] live in another world. It’s like living in a bubble. They [ICP operations team] do not understand that, you know, I’ve even been to some of the IBMs or whatever you call them. You know, they say, we really, you know, admissions are going down . . . they cannot implement anything medically without the rigor of statistical analysis and back up and they’ve absolutely no evidence whatsoever. So it just didn’t ring true. . . . They are more pestilent than actually helpful. You haven’t done this, you haven’t sent your case yet for the MDG, you know, you haven’t done enough care planning. (GP)

This antipathy was intensified by the executives’ urgency to implement the pilot. A strong expectation from the health care trusts’ executives, operations team, and project leads to deliver made the GPs and consultants question its success. Although providers were keen to be part of the development of pilot’s future objectives, they were frustrated at not having been sufficiently involved in decision-making. One GP said, “There’s very little anyone can do to affect the way it’s going forward . . . decisions have already been made . . . I do not feel that we’ve been sufficiently involved in those decisions.”

GPs, in particular, were concerned about the lack of local ownership of the pilot and involvement in the process of decision-making. One respondent commented on their disappointment with the fact that, in the set-up stages, the pilot appeared to be sold to many as GP and primary care led, whereas in practice, it felt as though the model was delivered to them rather than with them:

They [the ICP] made you feel that this was all going to be your pilot and anything you wanted would be down to you locally. So they kind of made you feel that you could maybe negotiate the funding that went with it; obviously we knew the overall funding envelope. Whether it was from funding to what a care plan really was, to how the MDG would function. GPs were given the impression that this would be something that they would be very much in control of per se, but they were pretty much within reason. The minute that we first went to the negotiations around how much, let’s talk, you know, talk about either finance or how often we should meet, who should meet, what a care plan was; all this stuff was completely different, was the reality. (GP)

Both GPs and consultants were aware that there was a political pressure for the pilot to succeed, but they were confused by what they were to be measured against, or what exactly the correct outcome was supposed to be. The original patient-centered narrative had become lost within an organizational change narrative. Combined with a top–down management style, the ensuing antipathy for the ICP led to a gradual withdrawal by some health care providers, at times vocally at ICP board meetings.

Financial Imperative Leads to Provider Centeredness

Anticipated financial savings from the pilot became a dominant narrative at senior executive levels. The emergence of a narrative based on financial resilience and a sense of urgency to effect wide-scale health sector reform couched tenuously in pilot form conspired to reveal existing tensions and levels of mistrust rooted in prior histories. Our respondents reported a history of difficult relationships between some organizations that became self-reinforcing: “GPs thought it was all [name of health care organization] and there was a slight mistrust of [same name of health care organization]. No one trusted anyone in terms of what the hell this [the ICP] was about” (HC).

A major concern for the pilot’s management was how to maintain provider engagement. There was recognition among our key informants that, in the longer term, the pilot needed to focus on maintaining momentum and moving toward stabilization, as well as realizing the benefits of financial savings and quality improvements. However, the pilot was mostly regarded as unlikely to achieve its full impact within its first year. There were concerns that because the pilot was being pushed to succeed, it was not given the time needed to mature. For instance, a consultant expressed concerns about the fact that the pilot was implemented without developing the necessary infrastructure: “I mean, I know the plusses of that system—I’m not, you know, hostile against it, but you cannot just suddenly impose that system without bricks and mortar and have the critical mass of people working together” (HC). Therefore, professionals saw the pilot as being “mission impossible,” in particular because of the challenges inherent in implementing such a large health care system intervention dependent on cultural change.

Some GPs and consultants started to question the pilot’s overall impact and the appropriateness of its interventions, particularly the multidisciplinary group meetings:

It is rare for there to be a major impact on patient care, and I cannot think of any in whom an admission has been avoided as a result of discussion [in the MDG meeting]. (GP)

Keep saying this is going to save money but most hospitals have deficits so people do not go to hospital—and that reduces funding and closure of the wards and hospitals. (HC)

The initial enthusiasm for the pilot gave way to skepticism as the “reality” of the pilot did not live up to professionals’ expectations:

It’s like a million ton super tanker going down—it cannot be stopped . . . despite countless occasions of trying to get people to see sense this is never going to work. (GP)

A washout from start to finish. It couldn’t be more different to what we were promised. Mars and Jupiter. (GP)

As gradual disillusionment with the pilot set in, coupled with the “us vs. them” sentiment developing among health care providers, health care providers began to attribute greater value to their own financial incentive structures within the pilot. GPs became more concerned with the potential for return on investment, with some complaining that payment did not reflect the time and effort that needed to be emotionally invested to achieve the pilot’s aims:

So [person’s name] found a system whereby we break even on the elderly [care plans], right? But break even? GPs do not really go for it . . . but the key thing is that, when you look at it, [person’s name] said that you’re really making a loss on it, if you are employing nurses, so you cannot ask GPs to take on something new which is either going to break even or lose them money. (GP)

I simply judge it on how much work it is and what we’re paid for. (GP)

Health care providers became far more preoccupied with the administrative, structural, and organizational issues that they faced. This was usually articulated in terms of the investment of time in attending the MDGs, duplication of work with care plans, and frustration with the IT tool. One HC told us,

No concept of the fact that my diary’s booked up three or four weeks in advance and having a very short notice to attend some MDGs, I think a major concern for me. And completely inexplicable is why they have different MDGs but at the same time on the same day, because I cannot split myself in half.

Others mentioned that if the bureaucracy and the workload remained as they were, GPs will most likely not want to stay involved: “I think the biggest challenge the ICP will face is if it does not make it more, it does not make it a leaner, more salient process for the GPs, they’ll walk actually. I’m pretty sure of that” (HC).

Although health care providers continued to participate and be involved in the pilot, they noted a palpable change in their emotional commitment to it. They became somewhat ambivalent with respect to whether the pilot was achieving the lofty goals it set out to achieve. As the financial imperative narrative took hold, and the pressure to reorganize acute and community services became the clear underlying driver for the pilot, its activity and its value came to be measured by health care providers in terms of its potential to bolster income or show value for money—not to the local health economy, nor to the patient population, but to individual providers.

Discussion

The research reported here explored professionals’ perceptions of their engagement in the development and implementation of an integrated health and social care initiative. Saks (2006) described engagement in terms of three seemingly static components. However, we noticed how engagement might change over time as an evolving process dependent on personal, social, and organizational factors. Advancing Saks, we found that the process of engagement is ongoing and fluid, requiring clear goals, credible leadership, and transparency, and for integrated care to be effective, this engagement needs to be well managed.

We noted a distinct evolving engagement experience. In the early stages, the pilot’s managers successfully harnessed health care providers’ enthusiasm for the pilot by drawing on common shared values of improving quality of patient care through improved coordination. During the following months, the predominant narrative shifted to that of service reorganization and efficiency savings, and a top–down management style that led to tension and antipathy among the health care providers. Many withdrew from the pilot, dissatisfied with both the reduced autonomy and emphasis on organizational change. In the third stage, the remaining health care providers themselves began to view the pilot more in terms of service reorganization, rather than the loftier, emotive values of patient quality of care. This manifested itself in a somewhat ambivalent preoccupation only for the financial gains and savings that the pilot could bring to their own organizations. These findings are represented schematically in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Evolving engagement experience.

As Ham, York, Sutch, and Shaw (2003) point out, the difficulties associated with managing change in health care organizations are well acknowledged. Past research, for instance, suggests that health care professionals tend not to be convinced that the change will bring improvement in patients and/or their working lives, and that factors such as increased workloads or new ways of working are often viewed negatively by professionals (Ford, Ford, & McNamara, 2002; Giangreco & Peccei, 2005; Gollop et al., 2004). The analysis of perceptions of the GPs and HCs in this study indicated the contradictions and tensions that it might involve. Their engagement was neither linear nor easily predicted; rather, the extent and type of engagement varied over time. In the light of Saks’s perspective on engagement, the health care professionals in this study exhibited different types of emotional and behavioral engagement depending on the predominant narratives at each developmental stage. A strong sense of participation and enthusiasm was reported when the prevailing narrative was patient centeredness or care quality, a tendency to withdraw and exhibit signs of antipathy when the prevailing narrative was top–down organizational change, and a general sense of ambivalence and preoccupation with own financial gain when the prevailing narrative was efficiency savings in the local health care economy.

Nurturing provider engagement requires a two-way relationship (Robinson, Perryman, & Hayday, 2004) between those who deliver the integrated health and social care and leaders. For change to be successful, all professionals are expected to be actively involved in the change process (Oswald, Mossholder, & Harris, 1994), to recognize that there is a clear need for change (Armenakis & Harris, 2009), and the benefits of change need to be properly communicated to them (Dent & Goldberg, 1999). To enable engagement, the expectations and motivation of all parties involved need to be understood and managed. Managers should not expect too much too early. Challenging savings targets and ambitious goals adversely affected health care providers’ engagement in this study. The level and type of engagement might vary during an integrated care project and so structures and processes need to be developed to enable managers to monitor these changes. This will support improved communication and in turn shared responsibility for the project.

Saks (2006) argued that engagement might represent a form of obligation. Hence, if organizations offer support to their employees, they might feel obliged to become cognitively, emotionally, and physically engaged in their work role. Nevertheless, as Saks conceded, not all forms of support or resources will result in securing engagement. Reward and recognition, for example, are not related to engagement after perceived organizational support and other job characteristics are controlled for. Consistent with this perspective, the perceptions of the health care professionals in this study indicated that without support and resources from the pilot’s managers and their organizations, individuals are less likely to be cognitively, emotionally, and physically engaged.

The contribution of this research lies in its focus on provider engagement, and how it affects and drives integrated care. Representing processes of integrated care through the construct of engagement allowed us to elaborate on the complexities of implementing a large-scale program of change. We acknowledge that engagement is a multidimensional and ambiguous concept and yet, we have found the cognitive, emotional, and behavioral engagement framework to be useful in understanding the empirical findings from the ICP evaluation. The providers’ experience of the pilot can be understood in terms of their emotional engagement with prevailing narratives. It suggests that managers of organizational change processes in integrated care might benefit from using this framework to find opportunities for successful change management. Provider engagement is fluid, organic, and changeable, and managers need to be cognizant of factors that enhance or optimize it. Starting with a clear and shared goal of integrated care is important, but the clarity of goals is essential, not only as a means of generating shared objectives but also in providing ongoing momentum to integration (Rosen et al., 2011).

Given that engagement is gaining increasing prominence as a focus of organizational change and government policy in the United Kingdom, further detailed investigation is needed. The complex relationship between engagement and integrated health and social care should be an area attracting increasing attention, because there is sparse empirical data to support an evidence-based discussion. A debate is needed about how integrated care initiatives, such as the one discussed here, can be better facilitated in health care systems, where many structures and systems are seemingly working against it (Greaves, Harris, Goodwin, & Dixon, 2012).

Finally, the results of this study should be considered in the light of its limitations. The present findings rely on the observations, analyses of interviews and focus groups, and inferences of researchers and the participants to identify those factors that appeared most relevant to the perceptions of engagement. Although we reduced the likelihood of selection bias by interviewing a wide range of health professionals and by triangulating our findings with other observations and document analyses, we cannot assume that the data that we obtained are representative of the experiences of all the providers in the ICP. Our data were analyzed separately by two researchers who independently developed coding schemes before discussing any coding ambiguities, and refined codes to resolve discrepancies. However, as is usual in qualitative research, we cannot assume that our coding schemes and interpretations accurately and precisely reflect the lived experience of the providers.

Conclusion

Health care leaders and managers need to be aware of the impact of professional engagement, understand its value and drivers, and promote change in ways that appeal to health care professionals if they are to succeed in moving the integrated care agenda forward.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the support from the Imperial College Healthcare Charity and North West (NW) London National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Collaboration for Leadership in Applied Health Research & Care.

Author Biographies

Agnieszka Ignatowicz, PhD, is a research fellow in the Department of Professional Education at University of Birmingham, Birmingham, UK.

Geva Greenfield, PhD, is a research associate in the Department of Primary Care and Public Health at Imperial College London, London, UK.

Yannis Pappas, PhD, is a head of PhD School at the Institute of Health Research and a senior lecturer in health services research at University of Bedfordshire, Luton, UK.

Josip Car, MD PhD, is a clinical senior lecturer in the Department of Primary Care and Public Health at Imperial College London, London, UK.

Azeem Majeed, MD FRCGP, is a professor of primary care in the Department of Primary Care and Public Health at Imperial College London, London, UK.

Matthew Harris, DPhil MBBS, is a Commonwealth Fund Harkness fellow in healthcare policy and practice at New York University, New York, USA, and an honorary clinical lecturer in the Department of Primary Care and Public Health at Imperial College London, London, UK.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. The views presented here are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the Commonwealth Fund, its directors, officers, or staff.

Funding: The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This study was supported by Imperial College Healthcare Charity. Matthew Harris was partly funded with a U.K. National Institute for Health Research Clinical Lectureship (LDN/930/038/A).

References

- Armenakis A., Harris S. (2009). Reflections: Our journey in organisational change research and practice. Journal of Change Management, 9, 127–142. 10.1080/14697-010902879079 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bakker A. B., Schaufeli W. B. (2008). Positive organizational behavior: Engaged employees in flourishing organizations. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 29, 147–154. 10.1002/job.515 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Berg B. L. (1995). Qualitative research methods for the social sciences. London: Allyn & Bacon. [Google Scholar]

- Clark J. (2012). Medical engagement: Too important to be left to chance. The King’s Fund. Retrieved from http://www.kings-fund.org.uk/sites/files/kf/medical-engagement-nhs-john-clark-leadership-review2012-paper.pdf

- Curry N., Harris M., Gunn L., Pappas Y., Blunt I., Soljak M., . . . Bardsley M. (2013). Integrated care pilot in North West London: A mixed methods evaluation. International Journal of Integrated Care, 13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dent E. B., Goldberg S. G. (1999). Resistance to change: A limiting perspective. The Journal of Applied Behavioral Science, 35, 45–47. 10.1177/0021886399351005 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- DeWalt K. M., DeWalt B. R. (2002). Participant observation: A guide for fieldworkers. Walnut Creek, CA: AltaMira Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ford J. D., Ford L. W., McNamara R. T. (2002). Resistance and the background conversations of change. Journal of Organizational Change Management, 15, 105–121. 10.1108/09534810210422991 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Giangreco A., Peccei R. (2005). The nature and antecedents of middle manager resistance to change: Evidence from an Italian context. International Journal of Human Resource Management, 16, 1812–1829. 10.1080/09585190500298404 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gitterman D., Weiner B. J., Domino M. E., Mckethan A. N., Enthoven A. C. (2003). The rise and fall of a Kaiser Permanente expansion region. Milbank Quarterly, 81, 567–601. 10.1046/j.0887-378X.2003.00295.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glaser B. G., Strauss A. L. (1967). The discovery of grounded theory: Strategies for qualitative research. New York: Aldine. [Google Scholar]

- Gollop R., Whitby E., Buchanan D., Ketley D. (2004). Influencing skeptical staff to become supporters of service improvement: A qualitative study of doctors’ and managers’ views. Quality and Safety in Health Care, 13, 108–114. 10.1136/qshc.2003.007450 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodwin N., Smith J., Davies A., Perry C., Rosen R., Dixon A., . . . Ham C. (2012). Integrated care for patients and populations: Improving outcomes by working together. The King’s Fund and Nuffield Trust. Retrieved from http://www.kingsfund.org.uk/sites/files/kf/integrated-care-patients-populations-paper-nuffield-trust-kings-fund-january-2012.pdf

- Greaves F., Harris M., Goodwin N., Dixon A. (2012). The commissioning reforms in the English National Health Service (NHS) and their potential impact on primary care. Journal of Ambulatory Care Management, 35, 192–199. 10.1097/JAC.0b013e31823e838f [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greaves F., Pappas Y., Bardsley M., Harris M., Curry N., Holder H., . . . Car J. (2013). Evaluation of complex integrated care programmes: The approach in North West London. International Journal of Integrated Care, 13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ham C., Curry N. (2011). Integrated care: What is it? Does it work? What does it mean for the NHS? London: The Kings Fund; Retrieved from http://www.kingsfund.org.uk/sites/files/kf/Integrated-care-summary-Sep11.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Ham C., De Silva D. (2009). Integrating care and transforming community services: What works? Where next? (Working paper). Birmingham, UK: Health Services Management Centre, University of Birmingham; Retrieved from http://epapers.bham.ac.uk/748/ [Google Scholar]

- Ham C., York N., Sutch S., Shaw R. (2003). Hospital bed utilisation in the NHS, Kaiser Permanente, and the US Medicare programme: Analysis of routine data. British Medical Journal, 327, Article 1257. 10.1136/bmj.327.7426.1257 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris M., Greaves F., Patterson S., Jones J., Pappas Y., Majeed A., Car J. (2012). The North West London integrated care pilot: Innovative strategies to improve care coordination for the elderly and people with diabetes. Journal of Ambulatory Care Management, 35, 216–225. 10.1097/JAC.0b013e31824d15c7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harter J. K., Schmidt F. L., Hayes T. L. (2002). Business-unit level relationship between employee satisfaction, employee engagement, and business outcomes: a meta-analysis. Journal of Applied Psychology, 87, 268-79. 10.1037//0021-9010.87.2.268 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jorm C., Kam P. (2004). Does medical culture limit doctors’ adoption of quality improvement? Lessons from Camelot. Journal of Health Services Research & Policy, 9, 248–251. 10.1258/1355819042250186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahn W. A. (1990). Psychological conditions of personal engagement and disengagement at work. Academy of Management Journal, 33, 692–724. 10.2307/256287 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Krueger R., Casey M. A. (2000). Focus groups: A practical guide for applied research (3rd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis R., Rosen R., Goodwin N., Dixon J. (2010). Where next for integrated care organizations in the NHS? London: Nuffield Trust; Retrieved from http://nuffield.dh.byte-mark.co.uk/sites/files/nuffield/publication/where_next_for_integrated_care_organisations_in_the_english_nhs_230310.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Light D., Dixon M. (2004). Making the NHS more like Kaiser Permanente. British Medical Journal, 328, 763–765. 10.1136/bmj.328.7442.763 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luisis-Lynd L., Myers P. (2010). How, why and when are organizations engaging with engagement? Paper presented at the Chartered Institute of Personnel and Development Centers’ Conference, Keel University, UK. [Google Scholar]

- MacLeod D., Clarke N. (2009). Engaging for success: Enhancing performance through employee engagement. London: Department for Business, Innovation and Skills; (BIS). Retrieved from http://www.engageforsuccess.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/09/file52215.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Marshall C., Rossman G. B. (1995). Designing qualitative research. Newbury Park, CA: SAGE. [Google Scholar]

- Maslach C., Leiter M. (2001). Job burnout. Annual Review of Psychology, 52, 397–422. 10.1146/annurev.psych.52.1.397 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- May D. R., Gilson R. I., Harter L. M. (2004). The psychological conditions of meaningfulness, safety and availability and the engagement of the human spirit at work. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 77, 11–37. 10.1348/096317904322915892 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- NHS North West London. (2011). North West London integrated care pilot: Business case. Retrieved from http://www.northwestlondon.nhs.uk/_uploads/~filestore/446FFFBF-2088-4AD7-8643-C9FD60869F8D.pdf

- Oswald S. L., Mossholder K. W., Harris S. G. (1994). Vision salience and strategic involvement: Implications for psychological attachment to organization and job. Strategic Management Journal, 15, 477–489. 10.1002/smj.4250150605 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Øvretveit J., Hansson J., Brommels M. (2010). An integrated health and social care organisation in Sweden: Creation and structure of a unique local public health and social care system. Health Policy, 97, 113–121. 10.1016/j.healthpol.2010.05.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powell-Davies G., Harris M., Perkins D., Roland M., Williams A., Larsen K., McDonald J. M. (2006). Coordination of care within primary health care and with other sectors: A systematic review (Australian Primary Health Care Research Institute Stream 4). Retrieved from http://www.health.vic.gov.au/pcps/downloads/careplanning/system_review_noapp.pdf

- RAND Europe and Ernst & Young. (2012). National evaluation of the DH integrated care pilots. UK: Author; Retrieved from http://www.rand.org/pubs/technical_reports/TR1164z2.html [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richie J., Spencer L. (1994). Qualitative data analysis for applied policy research. In Bryman A., Burgess B. (Eds.), Analysing qualitative data (pp.173–194). London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Richman A. (2006). Everyone wants an engaged workforce: How can you create it? Workspan, 49, 36–39 Retrieved from http://www.wfd.com/PDFS/Engaged%20Workforce%20Amy%20Richman%20Workspan.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Robinson D., Perryman S., Hayday S. (2004). The drivers of employee engagement. Brighton, UK: Institute for Employment Studies; (Report 408). Retrieved from http://www.wellbeing4business.co.uk/docs/Article%20-%20Engagement%20research.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Rosen R., Lewis G., Mountford J. (2011). Integration in action: Four international case studies. London: Nuffield Trust; Retrieved from http://www.nuffieldtrust.org.uk/sites/files/nuffield/integration-in-action-research-report-jul11.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Saks A. M. (2006). Antecedents and consequences of employ-ee engagement. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 21, 600–619. 10.1108/02683940610690169 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schaufeli W. B., Salanova M., Gonzalez-Roma V., Bakker A. B. (2002). The measurement of engagement and burnout: A two sample confirmatory factor analytic approach. Journal of Happiness Studies, 3, 71–92. 10.1177/0013164405282471 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Scientific Software Development. (1999). Atlas.ti: Qualitative data analysis (Version 4.2) [Computer software]. Retrieved from http://www.atlasti.com/index.html

- Shapiro J., Smith S. (2003). Lessons for the NHS from Kaiser Permanente. British Medical Journal, 327, 1241–1252. 10.1136/bmj.327.7426.1241 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw K. (2005). An engagement strategy process for communicators. Strategic Communication Management, 9(3), 26–29. [Google Scholar]

- Shaw S., Levenson R. (2011). Toward integrated care in Trafford (Research report). London: Nuffield Trust; Retrieved from http://www.nuffieldtrust.org.uk/sites/files/nuffield/publi-cation/towards_integrated_care_in_trafford_report_nov11.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Shekelle P. (2002). Why don’t physicians enthusiastically support quality improvement programmes. Quality and Safety in Health Care, 11, Article 6. 10.1136/qhc.11.1.6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sidorov J. (2003, November). Case study of a failed merger of hospital systems. Managed Care. Retrieved from http://www.managedcaremag.com/sites/default/files/imported/0311/0311.peer_merger.pdf [PubMed]

- Spradley J. P. (1980). Participant observation. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston. [Google Scholar]

- Spurgeon P., Clark J., Ham C. (2011). Medical leadership: From the dark side to center stage. London: Radcliffe. [Google Scholar]

- Trivedi A., Grebla R. C. (2011). Quality and equity of care in the veterans affairs health-care system and in Medicare advantage health plans. Medical Care, 49, 560–569. 10.1097/MLR.0b013e31820fb0f6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]