Abstract

Background:

Primary care has the potential to play significant roles in providing effective palliative care for non-cancer patients.

Aim:

To identify, critically appraise and synthesise the existing evidence on views on the provision of palliative care for non-cancer patients by primary care providers and reveal any gaps in the evidence.

Design:

Standard systematic review and narrative synthesis.

Data sources:

MEDLINE, Embase, CINAHL, PsycINFO, Applied Social Science Abstract and the Cochrane library were searched in 2012. Reference searching, hand searching, expert consultations and grey literature searches complemented these. Papers with the views of patients/carers or professionals on primary palliative care provision to non-cancer patients in the community were included. The amended Hawker’s criteria were used for quality assessment of included studies.

Results:

A total of 30 studies were included and represent the views of 719 patients, 605 carers and over 400 professionals. In all, 27 studies are from the United Kingdom. Patients and carers expect primary care physicians to provide compassionate care, have appropriate knowledge and play central roles in providing care. The roles of professionals are unclear to patients, carers and professionals themselves. Uncertainty of illness trajectory and lack of collaboration between health-care professionals were identified as barriers to effective care.

Conclusions:

Effective interprofessional work to deal with uncertainty and maintain coordinated care is needed for better palliative care provision to non-cancer patients in the community. Research into and development of a best model for effective interdisciplinary work are needed.

Keywords: Palliative care, primary health care, interprofessional relations, community health services, heart failure, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

What is already known about the topic?

Many people die of non-cancer diseases without enough access to palliative care.

Many patients want to be cared for at home until the last phase of their life.

Primary care plays important roles in providing palliative care in the community.

What this paper adds?

Non-cancer patients and carers expect general practitioners to provide compassionate care, have appropriate knowledge and play central roles in providing palliative care.

Continuity and coordination of the care are significant gaps in care provision.

Health-care professionals have reciprocal expectations and concerns that sometimes conflict with each other.

Uncertainty was recognised by health-care professionals as a great barrier to the provision of good palliative care.

Implications for practice, theory or policy

Effective interprofessional work needs to be enhanced in primary palliative care for non-cancer patients to deal with uncertainty and to assure continuity and coordinated care.

Research is needed on who should be the coordinators of the care, what kind of care models work and how it works.

Introduction

Palliative care has been historically developed with the focus on cancer. However, recent rapid global ageing and changes in disease prevalence, which are particularly evident in developed countries, have brought renewed attention to palliative care for chronic non-cancer diseases. Although there are increasing percentages of non-cancer patients among those utilising specialist palliative care services in the United Kingdom and the United States,1,2 many non-cancer patients are still dying in primary care settings without accessing specialist palliative care services. Considering the fact that more people wish to die at home in most developed countries than in hospitals,3,4 the role of primary care providers (PCPs) in palliative care for non-cancer patients is significant.

While some studies have shown that general practitioners (GPs) regard palliative care as a part of their responsibilities towards their patients,5–8 it has been suggested that not many non-cancer patients in the community receive adequate palliative care.7,9

The available evidence on the needs and experience of patients suffering from non-cancer diseases has been reviewed mainly in accordance with diagnoses.10,11 Yet, to our knowledge, this evidence has not been systemically reviewed to allow comparison across different perspectives, for example, those of patients, carers and health-care professionals (HCPs).

Health-care service planning must reflect the needs of service users.12 It is equally important to know the views of HCPs on the services, as the understanding of conflicts and agreement between HCPs and patients can lead to improvements in the services and clinical practice. The existing evidence regarding the different perspectives on palliative care provision to non-cancer patients in the community needs to be synthesised so as to inform clinicians and policy makers.

This review therefore identifies, critically appraises and synthesises the existing evidence on views on the provision of palliative care for non-cancer patients by PCPs and reveals any gaps in the evidence.

Methods

The definitions of terms used in this review are given in Table 1.

Table 1.

Definitions of terms.

| Palliative care: this review uses the definition of palliative care provided by WHO.13 |

| PCPs: |

| HCPs who are |

| 1. based in the community; |

| 2. taking care of a variety of patients within a certain population regardless of their diagnosis, gender or age; |

| 3. not trained to be specialists in palliative care, despite maybe having had some supplementary training in this area. |

| GPs: |

| Medical doctors who specialise in primary care; this includes ‘family physicians’. |

| Primary palliative care: |

| Palliative care provided by PCPs. |

| Carers: |

| Carers who are neither professional nor paid. These are usually family members of the patients, but may be friends or anyone who offers to care for the patients. Informal carers, family caregivers and those significant to the patients are included within this term in this review. |

WHO: World Health Organization; PCP: primary care provider; HCP: health-care professional; GP: general practitioner.

The methods for this review are structured according to The Centre for Reviews and Dissemination’s guidance for undertaking reviews in health care14 and the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement15 supplemented by guidance on narrative synthesis.16

Paper searches were conducted using MEDLINE, Embase, CINAHL, PsycINFO, Applied Social Science Abstract and the Cochrane library (all from inception to September 2012). The searches were conducted in September/October 2012.

Search terms were categorised into four groups:

Group 1: Disease diagnoses

Group 2: ‘Palliative care’

Group 3: ‘Primary care’

Group 4: ‘Attitude’

(See Appendix 1 for search terms.) These groups were combined with ‘AND’ to complete the search.

A cited reference search using SCOPUS was conducted for further identification of relevant studies. Reference lists of relevant papers were also manually searched. The content pages of Palliative Medicine (1987–1992, and January to November 2012) were hand-searched. Authors of relevant papers and principal researchers of relevant studies identified through UK Clinical Research Network Study Portfolio Database17 were asked for any further studies related to the review questions. Other search engines such as CareSearch database18 and Open Grey19 were searched to identify relevant grey literature.

Selection criteria were set to include studies reporting the views of patients/carers or professionals on primary palliative care provision to non-cancer patients in the community. The SPIDER tool enabled us to conceptualise eligibility criteria (Table 2).20

Table 2.

SPIDER tool and search term groups.

| SPIDER | In this review | Search term |

|---|---|---|

| S – sample | Patients with life-limiting diseases other than cancer | Group 1 |

| Carers | ||

| Any HCPs | ||

| PI – phenomenon of interest | Primary palliative care for non-cancer patients at home | (Group 1); Group 2; Group 3 |

| D – design | Any designs | |

| E – evaluation | ‘Views’ of participants | Group 4 |

| R – research type | Any types |

HCP: health-care professional.

In this review, ‘Sample’ of the study is patients, carers or professionals. Studies with patients or carers as participants are considered when 50% or more of the participants or the ones they cared for had non-cancer diagnoses. ‘Phenomenon of interest’ is primary palliative care provision to non-cancer patients at home. ‘Evaluation’ is participants’ views on this phenomenon. Any study designs, both quantitative and qualitative, are considered to be included.

Studies that focused on specific topics in palliative care (e.g. decision-making, symptom management, communication, euthanasia, out-of-hours care or identifying patients) were excluded. Papers that only reported patterns of service uses and did not contain any participants’ views were also excluded. Studies regarding care for special groups of patients, such as those with severe mental illnesses or those who were incarcerated, and for sexual minorities were also excluded, as the needs of these patients were assumed to be quite different from those of the majority of patients. Papers written in languages other than English, without any new empirical data or not providing sufficient information to judge their eligibility, were also excluded. We also decided to exclude the papers with limited reference to the review questions, as they were considered to have no impact on the overall conclusions.21–24

The titles and abstracts of all identified papers were screened by A.O. Of those that were selected for reading of the entire paper, 10% were randomly selected and their agreement with the eligibility requirements was confirmed by F.E.M.M. Any papers for which inclusion or exclusion was unclear were discussed to reach a consensus.

Information about the studies (e.g. study aims, country, study setting, targeting diseases, participants, sampling methods, types of collected data, analysis methods) was extracted from each paper.

Amended Hawker’s criteria4,25 were used for quality assessment of the included studies. These criteria aim to assess 10 aspects of the study (including aims, method, sampling, data analysis, bias and transferability or generalisability) graded from 1 (very poor) to 4 (very good) and have the advantages of being able to be used for all qualitative, quantitative and mixed-methods studies.

Given the heterogeneity of included studies, Narrative Synthesis16 is most appropriate for data synthesis in this review. Analysis and synthesis were done by grouping the data by tabulations, thematic analysis and conceptual mapping. Each theme from selected studies was tabulated and then synthesised. The robustness of the synthesis was assessed in the form of a critical appraisal of this review process and is described in the discussion section of this paper.

Results

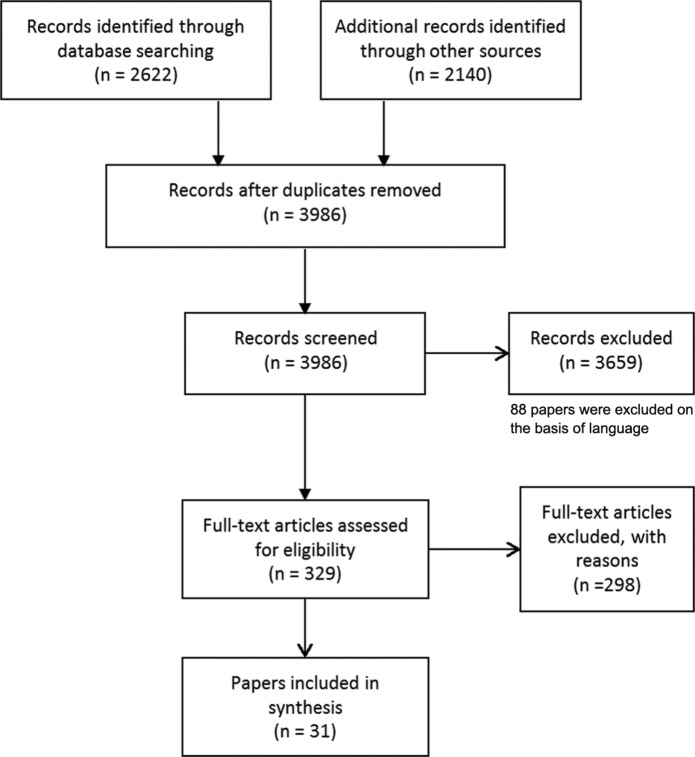

After the duplicates were removed, 3986 papers were identified for study selection. A total of 31 papers from 30 studies from 1998 to 2012 met the inclusion criteria. A PRISMA flow diagram15 of study selection is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram of study selection.15

PRISMA: Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses.

Characteristics of included studies

The overview of included studies is shown in Table 3. Apart from four studies, one from each of the United States, Australia, New Zealand and Sweden, all others were from the United Kingdom. These represent the views of 719 patients, 605 carers and over 400 professionals. Only three exclusively collected quantitative data and another three studies used mixed methods. All others were qualitative. Of the three quantitative studies, one was an intervention study31 and the other two were observational studies.45,46

Table 3.

Characteristics of included studies.

| Study | Disease | Participants | Relevant findings | Quality score |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Studies that have patients as participants | ||||

| Skilbeck et al.,26 United Kingdom | COPD | Patients (n = 63) | 47% thought the care provided by GPs was excellent, 40% good, 9% fair and 4% poor. | 27 |

| 34% received visits from the DN, but the nature of the visit was task-oriented (e.g. dressing or blood sample). | ||||

| Oliver,27 United Kingdom | COPD | Patients (n = 22) | Some patients remember negative messages such as ‘self-inflicted’, ‘nothing could be done’ at the diagnosis. | 28 |

| Relationship between HCPs can be strengthened by empathy. | ||||

| There is a reluctance to seek help because ‘nothing could be done’. | ||||

| Health-care needs as a direct intervention based on an exacerbation is noted. | ||||

| Patients think they need to be a good patient, not to be a nuisance because doctors hold immense power over decision-making. | ||||

| Primary care nurses are not considered as useful. | ||||

| Jones et al.,28 United Kingdom | COPD | Patients (n = 16) | Participants know when to call, but leave the decision to families. | 30 |

| Participants think GPs are too busy. | ||||

| Half of participants want to know more about illness, and the other half does not. | ||||

| Some think visits should be made regularly so as they would not have to ring. | ||||

| Patients attribute their ill conditions to smoking habits. | ||||

| Gysels and Higginson,29 United Kingdom | COPD | Patients (n = 18) | Patients attribute their conditions to smoking. | 32 |

| Some report GPs have lost their interest in patients when they disclose their smoking habit. | ||||

| GPs are considered helpless in treating symptoms. | ||||

| Patients experience difficulty in drawing proper attention from HCPs to their symptoms. | ||||

| DNs rarely visit patients. | ||||

| Shipman et al.,30 United Kingdom | COPD | Patients (n = 16) | Factors related to good relationship with GPs are as follows: | 32 |

| - Easy access, GPs’ willingness to visit | ||||

| - GPs’ understanding the concerns | ||||

| - Continuity of care | ||||

| Barriers to contacting GPs are as follows: | ||||

| - Physical barriers (pain, breathlessness) | ||||

| - Poor relationship with GPs, lack of continuity of care | ||||

| - Not wanting to know too much about the illness | ||||

| - Not knowing when to call | ||||

| - Not wanting to bother doctors ‘inappropriately’ | ||||

| - Feeling there is little to be done | ||||

| Contact with GPs tends to be made by proxies not by patients. | ||||

| Not much is mentioned about other members of primary care apart from GPs. | ||||

| Brumley et al.,31 United States | Cancer (47%), HF (33%), COPD (21%) | Patients (n = 298) | Coordination of care, interdisciplinary team with multi-dimensional approach and earlier involvement (prognosis with 12 months rather than 6 months) can increase the patients’ satisfaction, reduce the service use and cost. | 34 |

| Seamark et al.,32 United Kingdom | COPD | Patients (n = 10), carers (n = 8) | Conscious discussion about condition with HCPs is regarded positive. | 26 |

| Many participants deducted their conditions from the contact to HCPs. | ||||

| Specialist services are regarded as inaccessible or useless by some participants. | ||||

| Regular visits by any HCPs are considered to be a reassurance for carers. | ||||

| Edmonds et al.,33 United Kingdom | MS | Patients (n= 32) and carers (n= 17) | Lack of continuity and coordination of care both within and between social and health-care services are described as ‘compartmentalisation’. | 32 |

| Lack of organised information about EOL care is noted. | ||||

| Whitehead et al.,34 United Kingdom | MND | Patients (n = 24) and carers (n = 28) | Patients and carers experienced wide range of fears and anxiety regarding the final stages of the diseases. | 32 |

| Some participants need more information to help them make decisions regarding EOL care. | ||||

| Many participants wished to die at home. | ||||

| Carers wished to avoid hospital admission. | ||||

| Limited GP involvement and lack of continuity of care and expertise were reported. | ||||

| Accessing supportive care was described extremely difficult. | ||||

| Pinnock et al.,35 United Kingdom | COPD | Patients (n = 21), carers (n = 13) and professionals (n = 18) | Acceptance of disease leads patients not to seek out information about their condition. | 37 |

| Chaotic and long story of COPD with no beginning (contrast with HF and lung cancer) is noted. | ||||

| Illness experience is indistinguishable from their natural ageing. | ||||

| Clinicians find it more difficult making formal diagnosis of COPD and discussing about EOL care issues than with cancer patients. | ||||

| Longstanding relationship made discussing EOL care issues even more difficult. | ||||

| Death is not anticipated although some thought they would die during an exacerbation. | ||||

| Murray et al.,36 United Kingdom | HF | Patients (n = 20), carers (n = 20) and HCPs (n = ?) | Cancer care is considered to be more coordinated and resourced than HF care. | 30 |

| HF patients are less involved in decision-making. | ||||

| Primary care contacts are made mainly with GP. | ||||

| HF patients have less chance to die at home. | ||||

| GPs are frustrated by their limited role, which is to monitor and adjust the medication. | ||||

| Continuity of key professionals is hard to maintain. | ||||

| Care is based on a medical model focused on treatment. | ||||

| Boyd et al.,37 United Kingdom | HF | Patients (n = 20), carers (n = 20) and HCPs (n = 16) | GPs were regarded as the main contact and sometimes offer emotional and practical support. | 32 |

| Patients and carers are not sure about raising EOL care issues and GPs are awaiting for cues from them. | ||||

| Continuity of GPs’ care is hardly maintained. | ||||

| GPs frustrated as little could be done to help patients. | ||||

| Professionally led approach is not recognised as a partnership by patients and carers. Some GPs are not approachable for patients. | ||||

| Professionals were considered to have power over treatment and some patients prefer to leave decision-making to the professionals. | ||||

| A few patients actively avoided information. | ||||

| Information needs vary depending on patients’ preference. | ||||

| Professionals’ interest in the well-being of patients and carers was appreciated. | ||||

| Some patients thought GPs were not quick enough to prevent hospital admissions. | ||||

| HF nurse specialist home visit was considered useful, but some GPs were ambivalent, wanting the specialist nurses to have an advisory role. | ||||

| Boyd et al.,38 United Kingdom | HF | Patients (n = 36), carers (n = 30) and professionals (n = 32) | Professionals, who are supportive, continue the relationships and coordinate the care proactively, are highly valued. | 31 |

| Offering personalised information, fostering self-management, regular monitoring and holistic assessment are considered to be important. | ||||

| Tension between primary or secondary care was noted. | ||||

| It is recognised that primary care should function as a coordinator of the services. | ||||

| A lack of understanding specialists’ advisory role among HCPs is pointed out. | ||||

| Time constraints can compromise effective primary care. | ||||

| Prognostic uncertainty causes difficulty in introducing palliative care at the right timing. | ||||

| HF nurse specialists’ concerns about quality of care provided by non-specialists. | ||||

| Waterworth et al.,39 United Kingdom and New Zealand | HF | United Kingdom: patients and professionals (n = 120); New Zealand: patients and GPs (n = 25+?) | Time constraints at consultations are noted by both GPs and patients. | 29 |

| HF nurses are seen to be able to have more time with patients. | ||||

| Accessing GPs without appointment or during out-of-hours is possible for some patients, but this varies. | ||||

| Patients consider that GPs are busy. They do not want to waste GP’s time, but they also feel that their own time is wasted if their needs are not met. | ||||

| Some GPs have noticed patients’ notion of wasting GPs’ time. | ||||

| All GPs experience difficulty in prognostication and managing time to have the ‘difficult conversation’. | ||||

| Palliative care services were used to ensure ‘emotional’ time. | ||||

| Continuity of care is highly regarded. | ||||

| Hughes et al.,40 United Kingdom | MND | Patients (n= 9), carers (n = 5) and professionals (n = 15) | Conflicted views on service availability and usefulness among HCPs and patients are noted. (HCPs think MND patients are prioritised, while patients do not think so). | 33 |

| Lack of HCPs’ knowledge about MND and lack of coordination are perceived by patients. | ||||

| HCPs show their understanding of impacts of illness. | ||||

| Exley et al.,41 United Kingdom | Cancer (47%) and cardiorespiratory diseases (53%) | Patients (n = 27), carers (n = 7) and professionals (n = ?) | Little information is conveyed to GPs from hospital professionals, and GPs feel sidelined. | 29 |

| Patients and carers generally show their positive impression to their GPs. | ||||

| Non-cancer patients hesitate to ask for help to avoid ‘bothering’ GPs and DNs. | ||||

| More episodic care is provided to non-cancer patients. | ||||

| GPs are considered unable to do much to help them. | ||||

| GPs’ prompt response to ‘emergency calls’ is highly valued. | ||||

| DNs are absently referred by patients and carers. | ||||

| DNs think they are called only at a ‘crisis point’ from non-cancer patients. | ||||

| Disorganisation of out-of-hours care is pointed out by GPs. | ||||

| GPs think it is much harder to recognise the non-cancer patients dying, which leads to less communication on EOL care issues. | ||||

| Patients rely on lay understandings and interpretations to make sense of their symptoms. | ||||

| Fitzsimons et al.,42 United Kingdom | HF (n = 6), RF (n = 6), respiratory disease (n = 6) | Patients (n = 18), carers (n = 17) and professionals (n = 18) | Specialist nurses are cited as the main source of professional support and few patients cited other professional as beneficial. | 31 |

| Carers view resource availability as limited, and GPs’ time as constrained. | ||||

| Poor access to community service including appliances and financial benefits. | ||||

| Many patients show their acceptance of illness and insight to their poor prognosis. The longstanding relationship with HCPs enhances this trend. | ||||

| Some clinicians expressed difficulties in communicating poor prognosis; being afraid of taking away hope. | ||||

| Many participants have concerns about the uncertainty of the future. | ||||

| Studies that have only carers as participants | ||||

| Elkington et al.,43 United Kingdom | COPD | Bereaved carers (n = 25) | Patients do not necessarily seek help or accept offers of help. | 28 |

| Patients do not perceive there is a health problem. | ||||

| Health service provision at community level is valid in the last year of life. | ||||

| Respiratory nurses act as a link between primary and secondary care. | ||||

| Having someone who cares about (GPs or any other HCPs) and is willing to spend time with patients is appreciated. | ||||

| GPs’ attitudes (e.g. carrying on writing) and the lack of regular and active monitoring were criticised. | ||||

| Herz et al.,44 Australia | MND | Bereaved and current carers (n = 11) | Some participants view the GP as ‘an ally’ in the search for a cure. | 30 |

| The emotional cost is acknowledged by bereaved carers to be greater than physical burden. | ||||

| Lack of GPs’ knowledge about MND and their time are reported. | ||||

| Need for respite and not seeking help for emotional needs are reported by bereaved carers retrospectively. | ||||

| Addington-Hall et al.,45 United Kingdom | Stroke | Bereaved carers (n = 237) | More than three quarters of participants think that the GPs’ treatment for constipation and nausea/vomiting had relieved these symptoms ‘a lot’ or ‘some’ (88% and 79%, respectively), but smaller proportions report this degree of control of pain and breathlessness (55% and 66%, respectively). | 34 |

| 82%–90% think GPs have tried hard enough to control symptoms. | ||||

| Young et al.,46 United Kingdom | Stroke | Bereaved carers (n = 183) | 83% of participants report it is very or fairly easy to get an appointment with the GP urgently. | 27 |

| 50% discuss with GPs about worries as much as they wanted, 18% discussed but not as much as they wanted, 12% do not discuss although they had tried. | ||||

| 28% think GPs’ care is excellent, 39% good, 22% fair, 11% poor. | ||||

| Hasson et al.,47 United Kingdom | PD | Bereaved carers (n = 15) | Respite care is viewed as essential. | 31 |

| Lack of communication between primary and secondary caregivers is noted. | ||||

| Access to palliative care and services is thought to be patchy and uncoordinated. | ||||

| GPs are generally highly rated by participants; home visits and information access on carers’ behalf are particularly appreciated. | ||||

| Some suggest GPs’ lack of detailed knowledge of disease. | ||||

| McLaughlin et al.,48 United Kingdom | PD | Carers (n = 26) | Lack of communication between primary and secondary caregivers is noted. | 28 |

| The role of GPs is highly evaluated. | ||||

| Neurologists’ involvement is also considered as important by some carers implying the GPs’ lack of knowledge. | ||||

| Communication with and access to health and social care professionals are often ad hoc. | ||||

| Carers think that they only need palliative care when they are unable to cope. | ||||

| They want open communication with professionals. | ||||

| Need for respite is reported. | ||||

| Studies that have only professionals as participants | ||||

| Disler and Jones,49 United Kingdom | COPD | DNs (n = 43) | Nursing role is reported as task-oriented, but they think the relationship is based on emotional support. | 31 |

| Some feel sidelined or roles taken over by specialists’ involvement. | ||||

| Patients’ reluctance of seeking help/ignorance of health-care needs is noted. | ||||

| Historical background of cancer-focused palliative care is noted. | ||||

| Lack of knowledge/self-confidence is reported as a barrier to get involved in EOL care. | ||||

| Unpredictable illness trajectory makes them fail to see COPD as a progressive life-limiting illness. | ||||

| Hanratty et al.,50 United Kingdom | HF | Doctors (GPs, cardiologists, geriatricians and one palliative care doctor) (n = 34) | Three types of barriers to palliative care for HF patients are identified: | 32 |

| 1. Organisational barriers (e.g. no support for GPs, need for key workers, poor support in the community). | ||||

| 2. Prognostication (e.g. bad impact of giving bad news too soon). | ||||

| 3. Doctors’ roles (e.g. GPs are considered as a centre of care, GPs think SPC inaccessible or liable to steal their patients and cardiologist often fail to recognise palliative care needs). | ||||

| Hanratty et al.,51 United Kingdom | HF | Doctors (GPs, cardiologists, geriatricians and one palliative care doctor) (n = 36) | Palliative care for HF is seen as not very medical and expectation of nurses is greater than of doctors. | 28 |

| The balance between care and survival and the transition from rescue to comfort may not be clear-cut. | ||||

| It is noted that permission to fail is given in palliative care remit. | ||||

| Elusive role of palliative care specialists and doctors is reported. | ||||

| There is a need for support of GPs. | ||||

| Waterworth et al.52 and Waterworth and Gott,53 New Zealand | HF | GPs (n = 30) | The amount of information given to patients varies. | 27/30 |

| GPs are reluctant to use the word ‘failure’. | ||||

| GPs tend to be protective and they attribute it to patients’ old age. | ||||

| Illness trajectory is recognised as slow in decline, with multiple comorbidities, complex and unpredictable. | ||||

| Need for support for carers is noted. | ||||

| Referral to palliative care is regarded as a sensitive issue. | ||||

| Hospital admissions are considered as an indication for more support input. | ||||

| Conversation about prognosis and EOL care issues is recognised as difficult. | ||||

| Support system in the community is variable. | ||||

| Practice nurses’ role is considered as follows by GPs: | ||||

| - First contact, telephone communication is key | ||||

| - Education, team approach, coordinator of the care | ||||

| - Doing home visit | ||||

| GPs’ attitudes can limit practice nurses’ role. | ||||

| HF specialists’ actual involvement is viewed as minimal because of lack of organisation, time and available HF programme. | ||||

| Brännström et al.,55 Sweden | HF | Doctors (cardiologists and internists) (n = 15) | Lack of follow-ups and continuity of care are reported. | 31 |

| Refuting opinions are conveyed in whether generalists or specialists should take responsibility of patients with severe conditions. | ||||

| Potential of HF nurses being a part of follow-up is suggested. | ||||

| Unpredictable illness trajectory is thought to make decisions about ICDs, resuscitation and active treatment difficult. | ||||

| Grisaffi and Robinson,54 United Kingdom | Dementia | GPs (n = 10) | Definition of ‘end of life’ is thought to be vague. | 27 |

| Fluctuating illness trajectory at the end of life is noted. | ||||

| Prior knowledge of the person and eliciting wishes from patients themselves are thought to be important. | ||||

| Clinical assessment of patients with multiple comorbidities is viewed as an essential skill. | ||||

| Communication issues, discontinuity of care and low awareness of professionals are raised as dementia-related issues. | ||||

| Needs for education and raising awareness are noted. | ||||

| Field,5 United Kingdom | General | GPs (n = 25) | Terminal care is thought to be equated with care of cancer patients. | 26 |

| Patients with long-term conditions are viewed as different from those dying from cancer in many ways; progression of their disease and the continuing treatment options are available. | ||||

| It is harder for GPs to define non-cancer patients as ‘terminally ill’ because of unpredictable illness trajectory. | ||||

| It is thought that it takes longer for non-cancer patients to accept that they are dying. | ||||

| It is thought to be easier for cancer patients to access palliative care. | ||||

| Non-cancer patients are viewed as unlikely to be construed as terminally ill. | ||||

COPD: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; GP: general practitioner; HCP: health-care professional; MS: multiple sclerosis; EOL: end-of-life; MND: motor neurone disease; HF: heart failure; DN: district nurse; PD: Parkinson’s disease; RF: renal failure; SPC: specialist palliative care; ICD: implantable cardioverter defibrillator.

Nine of the included studies were about chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD).26–30,32,35,43,49 Eight studies had heart failure (HF) as their main topic.36–39,50–53,55 Three studies investigated the experience of motor neurone disease (MND),34,40,44 two were on Parkinson’s disease (PD)47,48 and one each was about patients with multiple sclerosis (MS)33 and dementia.54 Two survey studies examined stroke patients.45,46

More than half of the studies (17 studies) included patients as participants.26–42 Sixteen included bereaved or current carers.32–38,40–48

The average age of patient participants was approximately 70 years, with the exception of the MND and MS studies, which had younger populations.33,34,40

Most of the COPD and HF studies recruited participants through general practices while MND and MS studies employed a variety of recruitment methods, which probably reflected the prevalence of the diseases.

The results of the quality assessment of all included studies are displayed in Table 3. The mean score was 30.1 (range from 26 to 37).

Expectations of GPs

The identified themes were categorised as follows: service users’ expectations of GPs, roles of professionals and barriers to effective primary palliative care provision to non-cancer patients.

Patients and carers expressed various expectations of GPs based upon their experience and understanding of illness either explicitly or indirectly.

Five studies (on stroke, COPD, HF and renal failure) reported high satisfaction with GPs’ care.26,41,42,45,46 The same number of studies were interested in physicians’ views on palliative care for non-cancer patients.5,51,52,54,55 Three studies on COPD attempted to depict patients’ and carers’ views on professionals other than GPs in the primary care setting, but neither patients nor carers responded.27,28,30 For this reason, expectations of GPs – that is, compassionate care, knowledge and skills, central role and quick response – are presented in this section.

A compassionate attitude toward care is highly valued by patients and carers.30,37,38,42,43 In these studies, the willingness of GPs to spend time with patients and to understand their concerns is greatly welcomed. In contrast, dismissive attitudes (e.g. ‘carrying on writing’) are severely criticised.43

All three MND, two PD and one of the COPD studies convey the concerns of patients or carers over GPs’ lack of knowledge about the disease in question.29,34,40,44,47,48 The patients and carers attribute this lack of knowledge to either low prevalence of the disease40 or GPs’ time constraints.44 Lack of knowledge on the part of GPs leads to a lack of information for patients about available services40 or hinders patients from accessing general practices when needed.29 While some participants insist that GPs should have sufficient knowledge and skills, one carer of PD patients puts an emphasis on maintaining contact with neurologists for symptom management, doubting the ability of GPs in this area.48 In studies investigating HF care, some hospital doctors55 and specialist palliative care nurses38 are concerned about the quality of care provided by primary care teams.

Patients and carers report that GPs play a central role in their care.37,43 Some even convey their perceptions of GPs as partners in their journey with illness.44,47 This notion, of the GP as the central person in the care, is also shared by other HCPs including GPs themselves.37,50,51

Quick responses to urgent needs, including out-of-hours, are considered highly important by patients and carers.37,41 GPs are expected to be able to prevent unnecessary hospital admissions by responding to emergency needs. This may be related to some patients’ negative impressions of hospital admissions37 and carers’ beliefs that admission to hospital should be avoided.34,37

Roles of professionals

The unclear boundaries of the roles of each professional are recognised by HCPs themselves, as well as by patients and carers.

Both patients and nurses consider the nurses’ role to be task-oriented.26,49 However, one of the studies supporting this was ranked as relatively low in quality.26 Carers appreciate having nurses with good technical skills,34 which can be contrasted to their expectation of doctors to have a compassionate attitude. Moreover, primary care nurses think of themselves as lacking experience in end-of-life care for cardiorespiratory diseases.41,49 GPs, on the other hand, expect nurses to act as coordinators and to provide education and holistic care to patients with HF.53

Various views on the role of specialist nurses are shown across the studies. In one study conducted in a rural area, patients saw specialist respiratory nurses as less useful.32 Other studies report that nurses specialising in HF or COPD are seen as linking primary and secondary HCPs and as potentially useful.37,39,42,43,55 This disparity may be caused by the difference in settings, but it should be noted that the former study32 was assessed as low in quality and conducted by GPs, which potentially leads to bias towards generalists. Some studies show particular expectations of other HCPs for specialist HF nurses to take more active roles in the regular monitoring and coordination of care.52,55

Ambivalent feelings of PCPs towards specialist services are described in some studies, using words such as ‘sidelined’ and ‘taken over’ to express their feeling of specialist services taking over care of the patients.41,49 Those who have such feelings consider that specialist nurses should be restricted to an advisory role rather than providing direct care to the patients.41 While the importance of the role of specialist doctors in symptom management is cited by a PD carer,48 in other studies, patients cite specialist doctors as inaccessible.32 However, again, the latter study was conducted by GPs, and it is unclear whether they recruited participants from their practice, which could impact the results of the study.

Barriers to effective primary palliative care

Along with expectations, many barriers to effective primary palliative care have been identified in the included studies. The impacts of an uncertain and unpredictable illness trajectory are most frequently cited across studies.35,36,40–42,50,54,55 It is more evident that COPD starts without a clear onset and is punctuated by sporadic periods of exacerbation.26,27,35 HF and dementia, on the other hand, are conveyed as a rather gradual deterioration.39,54 The punctuated illness trajectory results in ad hoc care, which is prominent in COPD and HF.26–28,32,35,38,43,55 All HF, COPD, PD and MS patients and their carers expressed the need for continuity of care and regular monitoring.27,28,32,33,38,41,43,47,48,55

The uncertain illness trajectory results in difficulty in identifying the right timing for the transition of care.35,38,41,50,52,54 This is also related to difficulty in accepting their dying conditions for patients and carers.27,41,54

The lack of communication between care providers is also frequently pointed out.33,38,41,42,47,48,54 Not only are the boundaries of the roles of professionals unclear,38,47,50,51,55 but carers are often required to act as the coordinators of the care.33 One randomised controlled trial confirms that coordinated care can raise levels of satisfaction of patients.31

A lack of access to services for non-cancer patients is often cited across the disease groups.5,26,33,34,36,40–42,49,52 The importance of home visits to compensate for the limited access is also pointed out in the highest quality study exploring the access to general practices for people with advanced COPD.30 Some studies suggest that there are only a few existing available services,41,49 while others point out that information to access the service is not well organised.33,40

Some studies convey the patients’ notion that ‘GPs are busy’.28,38,39,44 Patients regard GPs’ time constraints as a reason for their not having received enough information or care from GPs.44 MND patients also claim that this situation has even hindered patients from seeking help from GPs.30,44 Some patients, particularly those from a COPD/HF cohort, think little or nothing could be done by HCPs to improve their situation, which is why the patients end up not seeking help.27,29,36,37,41 Some are anxious about bothering HCPs inappropriately, for fear this may have a negative impact on their treatment decision.27 Two studies respond to this notion of patients with comments from GPs, admitting that they indeed lack adequate time for sufficient care.38,52,53

Discussion

Principal findings of the review

A majority of the 30 included studies are on HF or COPD with small numbers of other diseases, for example, MND, stroke, PD, MS and dementia. In all, 27 of the studies use qualitative methods, 3 use mixed methods and another 3 are quantitative. In all, 27 studies are from the United Kingdom. The review represents the views of 719 patients, 605 carers and over 400 professionals.

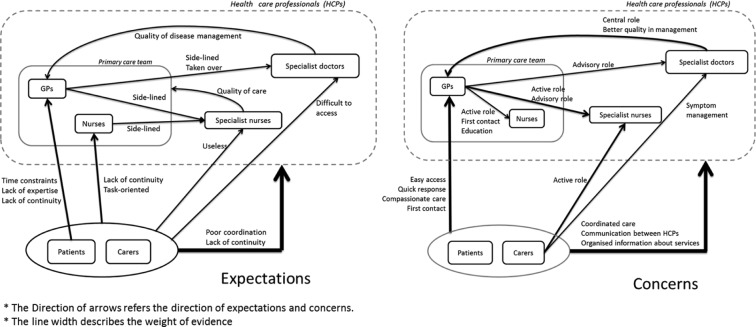

First, patients and carers highly value PCPs’ compassionate care, appropriate knowledge and skills, quick responses to urgent needs and maintenance of the coordination and continuity of care. Second, the unclear boundaries of the roles and responsibilities of each professional are recognised by HCPs themselves, as well as by patients and carers. HCPs also report their reciprocal expectations and concerns, which sometimes conflict with each other (Figure 2). While many patients, carers and other HCPs regard GPs as having a central role, GPs are juggling competing priorities with a limited amount of time, expecting nurses to take more active roles. In addition, uncertainty caused by unpredictable illness trajectory, lack of available resources and PCPs’ lack of expertise are listed as additional barriers to palliative care for non-cancer patients.

Figure 2.

Expectations and concerns between patients, carers and health-care professionals.

GP: general practitioner; HCP: health-care professional.

How the results fit in

There are two main challenges identified in this review, one is how to maintain continuity and coordination of care as a multiprofessional team and the other is how to deal with uncertainty. Patients’ expectations of GPs such as a compassionate attitude, availability for home visits and out-of-hours care to maintain continuity of care are consistent with those identified in previous studies.56–58 What has been newly added in this review is that uncertainty in non-cancer diseases makes meeting these expectations more difficult.

Uncertainty is likely to contribute to other barriers to effective care, for example, provision of care on an ad hoc (rather than planned) basis and failure to identify dying. This has been recognised as a challenge in palliative care for non-cancer patients.59–61 While many efforts have been made to develop a model to predict the right timing to introduce palliative care to non-cancer patients, there are as yet no definite tools.54,62 In COPD patients, for example, the gradual deterioration punctuated with exacerbations leads to ad hoc care.

Less available services and resources for non-cancer patients in the community aggravate the situation. In general, PCPs are required to achieve more with fewer resources. Table 4 summarises these expectations and barriers.

Table 4.

Expectations and barriers in palliative care in primary care settings.

| Expectations | Barriers | |

|---|---|---|

| Common in generic palliative care in primary care settings | Willingness to spend time with patient42 | Time constraints28,38,40,42,44,52,53 |

| Continuity of care30,33,34,40,41,43,48,55 | ||

| Prominent in non-cancer conditions | Regular monitoring32,38,47,55 | Unpredictable illness trajectory26,27,35–37,40–42,50–53,55 |

| Coordinated care33,36,37,40,42,47Information needs28,33,34,36–38,40,41,48Sufficient knowledge about diseases40,44,48 | Unclear roles of specialists Conflict between care and cure50,51,55 |

|

| Patients’ lack of insight for severity27,41 | ||

| Less available services26,33,34,36,37,40–42,49,52,53 | ||

| Lack of expertise41,49 |

Figure 2 shows the reciprocal expectations and concerns between patients, carers and HCPs. What is notable is that no expectations of primary care nurses were directly expressed by patients, while concerns over their lack of continuity were voiced. This is supported by other evidence showing the low prevalence of access to community nurses.63 Moreover, no other primary care team members were discussed in the included studies. In one study, the interviewers attempted to draw out opinions about other professionals but participants did not respond,41 showing that they minimally consider other professionals in the primary care team. It is hence plausible that patients and carers predominantly consider GPs to be the main professional of their care in primary palliative care.

Regarding the role of primary care nurses, the results of the present review are by and large consistent with a previous systematic review.64 One exception is that while primary care nurses regarded palliative care as holistic care in the previous review, this was not clearly shown in the present review. Moreover, the unpredictability of illness trajectory and a lack of expertise and awareness were identified as additional barriers to provision of palliative care to non-cancer patients. This is concordant with the findings in Table 4.

From GPs’ point of view, they expect nurses to take more active roles.50–53 This might be a reflection of GPs’ excessive workloads and the expectations placed upon them. In fact, it seems impossible for GPs to take on all responsibilities given the multi-dimensional principle of palliative care.13 Taking these findings into account, it seems that collaborations between GPs and primary care nurses are not efficiently undertaken, with primary care nurses roles being minimally considered by patients.

GPs also expect specialists to play advisory roles rather than to take full responsibility for the patients. GPs expressed discomfort about their role towards the patients being completely taken over, and this discomfort was also shared by primary care nurses. On the whole, interprofessional work in primary palliative care settings is relatively ineffective despite the importance of collaboration having been repeatedly emphasised.65–67 This is even more relevant for non-cancer patients because the fluctuating trajectory of their illnesses can cause frequent exacerbations and admissions.68

This raises an issue as to how we can promote coordinated care and who should be the coordinator of the care. In the United Kingdom, the National Gold Standard Framework has been introduced as a systematic approach to enhance coordinated care.69 While its effectiveness has been shown,70–73 it is also suggested that an adequate amount of time to maintain shared vision, mutual respect and inclusive decision-making are important for its successful implementation.74 Moreover, good networks are usually based on personal liaison rather than on a systematic approach.75

Allocating key care workers has been suggested to be important to maintain the continuity of care;76 however, it is difficult from the present review to conclude who should be the coordinator of the care. While GPs are usually seen as the multidisciplinary team lead in the present review, they obviously lack time and resources. Some evidence within and outside of this review supports specialist nurses can possibly be the key workers.37,39,42,43,52,53,76 The decision is probably better made locally, however, according to available resources and local preference.

Strengths and limitations

This review, to our knowledge, is the first systematic review of views on palliative care provided by PCPs to non-cancer patients in community. It combines both qualitative and quantitative evidence with a wide range of views from different perspectives across the diseases. The completeness of the search with expert consultation and hand searching maximised the identification of the studies.

However, there are some limitations that should be considered in included studies. Many studies lacked detailed information about their participants, for example, patients’ medical conditions or specialties of HCPs and the settings in which they were working.35–38,40–42,49 Second, reporting by whom the findings are conveyed was also often missed. Despite the fact that having interviewed patients and carers together may affect the data, reports often failed to mention if they had interviewed them together or separately.34,38 Only Edmonds et al.33 mentioned this issue in their discussion.

At the review level, a majority of the included studies are from the United Kingdom, which may impact the generalisability of the findings. Cultural impacts on end-of-life care issues have to be considered when interpreting the results of this review. However, we believe our findings are useful to other nations with similar care models to that in the United Kingdom.

Another potential bias is that only one reviewer conducted the review process, with appraisals of a second reviewer at each step. As narrative synthesis is still regarded as a somewhat subjective method, having more reviewers would be preferable, but was not possible due to the limited resources available for this review.

Finally, excluding some papers with only a limited reference to the review questions21–24 can be considered a weakness. This approach was adopted to make the review more feasible and the synthesis more appropriate. Furthermore, because the synthesis does not rely on quantitative concepts, and the contents extracted from included studies were sufficient, we believe excluding these papers did not affect the overall results.

Implications for practice, policy and research

Continuity and coordination of care seemed to be significant gaps in care provision along with the great challenge of uncertainty. The important point is to acknowledge uncertainty of illness trajectory – and for HCPs to share this acknowledgement with patients and carers – and develop a joint strategy or care plan to help manage it. To accept and deal with uncertainty has in fact been suggested as being a part of medical generalist services.77 Paying attention to detail, being sensitive to patients’ and carers’ concerns and creating innovative solutions that are pertinent to compassionate care are ways to overcome the challenges caused by uncertainty.61,78

Enhancing interdisciplinary work not only increases the capacity as a team to support patients with a great extent of uncertainty in their illness trajectory but also enables more coordinated care to assure continuity. It is necessary to develop a better framework or better ways to utilise existing frameworks to achieve effective collaboration particularly in relation to palliative care for non-cancer patients. The existing care models should receive more in-depth evaluation in terms of how they work and what impact they have on multidisciplinary teams to inform future policymaking. Based on the findings of this review, as Barclay mentioned,79 palliative care specialists should probably concentrate on short-term intensive input to more complicated cases rather than maintaining long-term relationships with patients.

Conclusion

Our review found that patients expect GPs to provide compassionate care, have appropriate knowledge and play central roles in coordinated care. Uncertainty of the illness trajectory, unclear definition of the role of professionals and lack of collaboration between professionals are identified as barriers to effective primary palliative care provision to non-cancer patients. It is crucial to increase the capacity to deal with uncertainty as a team through effective interdisciplinary work. Clear role definitions of each professional and effective interprofessional collaboration will help to manage many challenges encountered in delivering palliative care to non-cancer patients in the community. Research into and development of a best model for effective interdisciplinary work are needed for better primary palliative care provision for non-cancer patients.

Acknowledgments

Thanks to Ms Denise Brady for review of search headings and to Professor Popay and colleagues for development of guidance on narrative synthesis. The authors also would like to thank Professor Masato Matsushima for his helpful comments on the paper.

Appendix

Appendix 1.

Selected search terms

| Group 1 | non-malignan* |

| non-cancer* | |

| non-oncolog*. mp. | |

| stroke | |

| cerebrovascular* | |

| pulmonary emphysema | |

| chronic obstructive pulmonary disease/COPD | |

| neurodegenerative diseases | |

| motor neuron* disease/MND | |

| amyotrophic lateral sclerosis/ALS | |

| parkinson* disease | |

| multiple sclerosis/MS | |

| multiple system atrophy | |

| progressive supranuclear palsy | |

| acquired immunodeficiency syndrome/AIDS | |

| human immunodeficiency virus infection/HIV | |

| dementia | |

| huntington* | |

| heart failure | |

| chronic kidney failure | |

| end stage liver disease | |

| Group 2 | palliative care |

| terminal care | |

| terminally ill | |

| end of life | |

| Group 3 | family practice/family medicine/family physician |

| general practice/general practitioner | |

| primary health care | |

| community health services | |

| community health nursing | |

| public health nursing | |

| Group 4 | attitude of health personnel |

| attitude to death | |

| delivery of health care | |

| health service accessibility | |

| clinical competence |

Footnotes

Declaration of conflicting interests: The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

References

- 1. National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization. NHPCO facts and figures: hospice care in America, 2012 edition, 2012, http://www.nhpco.org/sites/default/files/public/Statistics_Research/2012_Facts_Figures.pdf

- 2. The National Council for Palliative Care. National survey of patient activity data for specialist palliative care services: MDS full report for the year 2011–2012, 2012, http://www.ncpc.org.uk/sites/default/files/MDS%20Full%20Report%202012.pdf

- 3. Fukui S, Yoshiuchi K, Fujita J, et al. Japanese people’s preference for place of end-of-life care and death: a population-based nationwide survey. J Pain Symptom Manage 2011; 42(6): 882–892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Murtagh FEM, Bausewein C, Sleeman K, et al. Understanding place of death for patients with non malignant conditions: a systematic literature review. Southampton: National Institute of Health Research, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Field D. Special not different: general practitioners’ accounts of their care of dying people. Soc Sci Med 1998; 46(9): 1111–1120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. O’Connor M, Lee-Steere R. General practitioners’ attitudes to palliative care: a Western Australian rural perspective. J Palliat Med 2006; 9(6): 1271–1281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Burt J, Shipman C, White P, et al. Roles, service knowledge and priorities in the provision of palliative care: a postal survey of London GPs. Palliat Med 2006; 20(5): 487–492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Gott M, Seymour J, Ingleton C, et al. ‘That’s part of everybody’s job’: the perspectives of health care staff in England and New Zealand on the meaning and remit of palliative care. Palliat Med 2012; 26(3): 232–241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Addington-Hall JM, Hunt K. Non-cancer patients as an under-served group. In: Cohen J, Deliens L. (eds) A public health perspective on end of life care. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012, pp. 151–159. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Gibbs JSR, McCoy ASM, Gibbs LME, et al. Living with and dying from heart failure: the role of palliative care. Heart 2002; 88(Suppl. 2): ii36–ii39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Giacomini M, DeJean D. Experiences of living and dying with COPD: a systematic review and synthesis of the qualitative empirical literature. Ont Health Technol Assess Ser 2012; 12(13): 1–47. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Lorenz KA, Shugarman LR, Lynn J. Health care policy issues in end-of-life care. J Palliat Med 2006; 9(3): 731–748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. World Health Organization. WHO definition of palliative care, 2002, http://www.who.int/cancer/palliative/definition/en/

- 14. Centre for Reviews and Dissemination. Systematic reviews: CRD’s guidance for undertaking reviews in health care. York: CRD, University of York, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. Ann Intern Med 2009; 151(4): W65–W94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Popay J, Roberts H, Sowden A, et al. Guidance on the conduct of narrative synthesis in systematic reviews: a product from the ESRC methods programme, http://www.lancaster.ac.uk/shm/research/nssr/research/dissemination/publications.php (2006)

- 17. UK Clinical Research Network Study Portfolio Database. http://public.ukcrn.org.uk/search/

- 18. CareSearch Grey Literature. http://www.caresearch.com.au/caresearch/FindingEvidence/CareSearchGreyLiterature/tabid/82/Default.aspx

- 19. Open Grey. http://www.opengrey.eu/

- 20. Cooke A, Smith D, Booth A. Beyond PICO: the SPIDER tool for qualitative evidence synthesis. Qual Health Res 2012; 22(10): 1435–1443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Waterworth S, Jorgensen D. It’s not just about heart failure – voices of older people in transition to dependence and death. Health Soc Care Community 2010; 18(2): 199–207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Wotton K, Borbasi S, Redden M. When all else has failed: nurses’ perception of factors influencing palliative care for patients with end-stage heart failure. J Cardiovasc Nurs 2005; 20(1): 18–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Davison SN, Simpson C. Hope and advance care planning in patients with end stage renal disease: qualitative interview study. BMJ 2006; 333(7574): 886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Mahtani-Chugani V, Gonzalez-Castro I, De Ormijana-Hernandez AS, et al. How to provide care for patients suffering from terminal non-oncological diseases: barriers to a palliative care approach. Palliat Med 2010; 24(8): 787–795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Hawker S, Payne S, Kerr C, et al. Appraising the evidence: reviewing disparate data systematically. Qual Health Res 2002; 12(9): 1284–1299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Skilbeck J, Mott L, Page H, et al. Palliative care in chronic obstructive airways disease: a needs assessment. Palliat Med 1998; 12(4): 245–254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Oliver S. Living with failing lungs: the doctor-patient relationship. Fam Pract 2001; 18(4): 430–439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Jones I, Kirby A, Ormiston P, et al. The needs of patients dying of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in the community. Fam Pract 2004; 21(3): 310–313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Gysels M, Higginson IJ. Access to services for patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: the invisibility of breathlessness. J Pain Symptom Manage 2008; 36(5): 451–460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Shipman C, White S, Gysels M, et al. Access to care in advanced COPD: factors that influence contact with general practice services. Prim Care Respir J 2009; 18(4): 273–278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Brumley R, Enguidanos S, Jamison P, et al. Increased satisfaction with care and lower costs: results of a randomized trial of in-home palliative care. J Am Geriatr Soc 2007; 55(7): 993–1000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Seamark DA, Blake SD, Seamark CJ, et al. Living with severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD): perceptions of patients and their carers. An interpretative phenomenological analysis. Palliat Med 2004; 18(7): 619–625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Edmonds P, Vivat B, Burman R, et al. ‘Fighting for everything’: service experiences of people severely affected by multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler 2007; 13(5): 660–667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Whitehead B, O’Brien MR, Jack BA, et al. Experiences of dying, death and bereavement in motor neurone disease: a qualitative study. Palliat Med 2011; 26(4): 368–378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Pinnock H, Kendall M, Murray SA, et al. Living and dying with severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: multi-perspective longitudinal qualitative study. BMJ 2011; 342(7791): d142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Murray SA, Boyd K, Kendall M, et al. Dying of lung cancer or cardiac failure: prospective qualitative interview study of patients and their carers in the community. BMJ 2002; 325(7370): 929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Boyd KJ, Murray SA, Kendall M, et al. Living with advanced heart failure: a prospective, community based study of patients and their carers. Eur J Heart Fail 2004; 6(5): 585–591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Boyd KJ, Worth A, Kendall M, et al. Making sure services deliver for people with advanced heart failure: a longitudinal qualitative study of patients, family carers, and health professionals. Palliat Med 2009; 23(8): 767–776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Waterworth S, Gott M, Raphael D, et al. Older people with heart failure and general practitioners: temporal reference frameworks and implications for practice. Health Soc Care Community 2011; 19(4): 412–419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Hughes RA, Sinha A, Higginson IJ, et al. Living with motor neurone disease: lives, experiences of services and suggestions for change. Health Soc Care Community 2005; 13(1): 64–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Exley C, Field D, Jones L, et al. Palliative care in the community for cancer and end-stage cardiorespiratory disease: the views of patients, lay-carers and health care professionals. Palliat Med 2005; 19(1): 76–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Fitzsimons D, Mullan D, Wilson JS, et al. The challenge of patients’ unmet palliative care needs in the final stages of chronic illness. Palliat Med 2007; 21(4): 313–322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Elkington H, White P, Addington-Hall JM, et al. The last year of life of COPD: a qualitative study of symptoms and services. Respir Med 2004; 98(5): 439–445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Herz H, McKinnon PM, Butow PN. Proof of love and other themes: a qualitative exploration of the experience of caring for people with motor neurone disease. Prog Palliat Care 2006; 14(5): 209–214. [Google Scholar]

- 45. Addington-Hall JM, Lay M, Altmann D, et al. Symptom control, communication with health professionals, and hospital care of stroke patients in the last year of life as reported by surviving family, friends, and officials. Stroke 1995; 26(12): 2242–2248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Young AJ, Rogers A, Addington-Hall JM. The quality and adequacy of care received at home in the last 3 months of life by people who died following a stroke: a retrospective survey of surviving family and friends using the Views of Informal Carers Evaluation of Services questionnaire. Health Soc Care Community 2008; 16(4): 419–428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Hasson F, Kernohan WG, McLaughlin M, et al. An exploration into the palliative and end-of-life experiences of carers of people with Parkinson’s disease. Palliat Med 2010; 24(7): 731–736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. McLaughlin D, Hasson F, Kernohan WG, et al. Living and coping with Parkinson’s disease: perceptions of informal carers. Palliat Med 2011; 25(2): 177–182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Disler R, Jones A. District nurse interaction in engaging with end-stage chronic obstructive pulmonary disease patients: a mixed methods study. J Nurs Healthc Chronic Illn 2010; 2(4): 302–312. [Google Scholar]

- 50. Hanratty B, Hibbert D, Mair F, et al. Doctors’ perceptions of palliative care for heart failure: focus group study. BMJ 2002; 325(7364): 581–585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Hanratty B, Hibbert D, Mair F, et al. Doctor’s understanding of palliative care. Palliat Med 2006; 20(5): 493–497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Waterworth S, Raphael D, Horsburgh M. Yes, but it’s somewhat difficult-managing end of life care in primary health care. Ageing Int 2010; 37(4): 459–469. [Google Scholar]

- 53. Waterworth S, Gott M. Involvement of the practice nurse in supporting older people with heart failure: GP perspectives. Prog Palliat Care 2012; 20(1): 7–12. [Google Scholar]

- 54. Grisaffi K, Robinson L. Timing of end-of-life care in dementia: difficulties and dilemmas for GPs. J Dement Care 2010; 18(3): 36–39. [Google Scholar]

- 55. Brännström M, Forssell A, Pettersson B. Physicians’ experiences of palliative care for heart failure patients. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs 2011; 10(1): 64–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Mitchell GK. How well do general practitioners deliver palliative care? A systematic review. Palliat Med 2002; 16(6): 457–464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Grande GE, Farquhar MC, Barclay SI, et al. Valued aspects of primary palliative care: content analysis of bereaved carers’ descriptions. Br J Gen Pract 2004; 54(507): 772–778. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Borgsteede S. Good end-of-life care according to patients and their GPs. Br J Gen Pract 2006; 56(522): 20–26. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Lunney JR, Lynn J, Foley DJ, et al. Pattern of functional decline at the end of life. JAMA 2003; 289(18): 2387–2392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Murray SA, Kendall M, Boyd K, et al. Illness trajectories and palliative care. BMJ 2005; 330(7498): 1007–1011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Murtagh FEM, Preston M, Higginson IJ. Patterns of dying: palliative care for non-malignant disease. Clin Med 2004; 4(1): 39–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Coventry PA, Grande GE, Richards DA, et al. Prediction of appropriate timing of palliative care for older adults with non-malignant life-threatening disease: a systematic review. Age Ageing 2005; 34(3): 218–227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Elkington H, White P, Addington-Hall JM, et al. The healthcare needs of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease patients in the last year of life. Palliat Med 2005; 19(6): 485–491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Walshe C, Luker KA. District nurses’ role in palliative care provision: a realist review. Int J Nurs Stud 2010; 47(9): 1167–1183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Barclay S, Rogers M, Todd C. Communication between GPs and cooperatives is poor for terminally ill patients. BMJ 1997; 315(7117): 1235–1236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Goldsmith J, Wittenberg-Lyles E, Rodriguez D, et al. Interdisciplinary geriatric and palliative care team narratives: collaboration practices and barriers. Qual Health Res 2010; 20(1): 93–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Meier DE, Beresford L. The palliative care team. J Palliat Med 2008; 11(5): 677–681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Low J, Pattenden J, Candy B, et al. Palliative care in advanced heart failure: an international review of the perspectives of recipients and health professionals on care provision. J Card Fail 2011; 17(3): 231–252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Thomas K, Noble B. Improving the delivery of palliative care in general practice: an evaluation of the first phase of the Gold Standards Framework. Palliat Med 2007; 21(1): 49–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Walshe C, Caress A, Chew-Graham C, et al. Implementation and impact of the Gold Standards Framework in community palliative care: a qualitative study of three primary care trusts. Palliat Med 2008; 22(6): 736–743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Munday D, Mahmood K, Dale J, et al. Facilitating good process in primary palliative care: does the Gold Standards Framework enable quality performance? Fam Pract 2007; 24(5): 486–494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. The National GSF Centre. The gold standards framework in primary care: GSF primary care briefing paper, 2009, http://www.thewpca.org/EasysiteWeb/getresource.axd?AssetID=93083&type=Full&servicetype=Attachment\FINAL%20GSF%20Brochure%20UK%20(1).pdf

- 73. Watson J, Hockley J, Murray S. Evaluating effectiveness of the GSFCH and LCP in care homes. End Life J 2010; 4(3): 42–49. [Google Scholar]

- 74. Shaw KL, Clifford C, Thomas K, et al. Review: improving end-of-life care: a critical review of the gold standards framework in primary care. Palliat Med 2010; 24(3): 317–329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Gardiner C, Gott M, Ingleton C. Factors supporting good partnership working between generalist and specialist palliative care services: a systematic review. Br J Gen Pract 2012; 62(598): e353–e362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Daley A, Matthews C, Williams A. Heart failure and palliative care services working in partnership: report of a new model of care. Palliat Med 2006; 20(6): 593–601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Royal College of General Practitioners. Medical generalism: Why expertise in whole person medicine matters London: Royal College of General Practitioners, 2012, http://www.rcgp.org.uk/policy/rcgp-policy-areas/~/media/Files/Policy/A-Z-policy/Medical-Generalism-Why_expertise_in_whole_person_medicine_matters.ashx [Google Scholar]

- 78. Murray SA, Boyd K, Sheikh A. Palliative care in chronic illness. BMJ 2005; 330(7492): 611–612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Barclay S. Palliative care for non-cancer patients: a UK perspective from primary care. In: Addington-Hall JM, Higginson IJ. (eds) Palliative care for non-cancer patients. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001, pp. 172–185. [Google Scholar]