Abstract

Osteoarthritis-related joint pain is prevalent and potentially disabling. United Kingdom clinical guidelines suggest that patients should be supported to self-manage in primary care settings. However, the processes and mechanisms that influence patient consultation decisions for joint pain are not comprehensively understood. We recruited participants (N = 22) from an existing longitudinal survey to take part in in-depth interviews and a diary study. We found that consultation decisions and illness actions were ongoing social processes. The need for and benefits of consulting were weighed against the value of consuming the time of a professional who was considered an expert. We suggest that how general practitioners manage consultations influences patient actions and is part of a broader process of defining the utility and moral worth of consulting. Recognizing these factors will improve self-management support and consultation outcomes.

Keywords: health care, users’; experiences; interviews, semistructured; musculoskeletal disorders; relationships, patient-provider; self-care

It has been estimated that up to 8.5 million people in the United Kingdom could be affected by chronic joint pain that can be attributed to osteoarthritis (Arthritis Care, 2012). Osteoarthritis (OA) has been described as a serious and life-altering joint disease which causes pain and disability, impacts on quality of life, interferes with work productivity, results in joint replacement, and generates inordinate socioeconomic costs worldwide (Lubar et al., 2010). United Kingdom policymakers advocated that to address the personal impact and cost to the state, encouraging self-management of OA should be central to interventions and best practice in primary care (Department of Health [DoH], 2006).

The National Institute of Clinical Excellence (NICE) provided guidelines to outline core recommended treatments for OA: information provision and advice, aerobic and local strengthening exercises, and weight loss if overweight or obese. They also recommended a number of adjunctive treatments such as the use of transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) machines, supports, or other aids and devices (NICE, 2008).

Different groups of people have attached different meanings to the concept of self-management. Kendall and Rogers (2007) highlighted that the professional interpretation of self-management often focused on patients managing symptoms and complying with medical routines. For patients, lay self-management is the process of managing self, social relationships, symptoms, and medical routines (Kendall & Rogers). Thus, it has been argued that self-management support should draw on patient experiences and existing strategies and concerns when offering biomedically oriented advice as appropriate (Kennedy, Rogers, & Bower, 2007; NICE, 2008).

Researchers have suggested that lay joint pain self-management takes the form of deploying strategies to continue valued everyday activities (Grime, Richardson, & Ong, 2010; Morden, Jinks, & Ong, 2011; Ong, Jinks, & Morden, 2011). Conversely, other evidence has suggested that some patients could require additional biomedically oriented help and support if they struggle to remain active or need help to lose weight (Holden, Nicholls, Young, Hay, & Foster, 2012; Morden, Jinks, & Ong, 2013; Pouli, Das Nair, Lincoln, & Walsh, 2013).

Policies and guidelines that promote the provision of supported self-management implicitly suggest that patients will consult. This assumption is not unproblematic, and we discuss the reasons for this below. We contend that there is a need to differentiate between research that has reported lay activities of self-management (Morden et al., 2011; Ong et al., 2011) and the related, but discrete activity of help seeking. We do so to provide a rounded perspective of how health services can help provide supported self-management if and when patients require additional help, support, and advice.

From the perspective of the patient with joint pain, two factors have inhibited the promotion of self-management in primary care settings. First, people have not always sought help for their joint pain when they experienced symptoms (Bedson, Mottram, Thomas, & Peat, 2007). Research has found that lay people hold socioculturally situated understandings that joint pain is related to aging or a biographically situated process of “wear and tear” associated with use of the joint (Busby, Williams, & Rogers, 1997; Grime et al., 2010; Sanders, Donovan, & Dieppe, 2002). Therefore, joint pain has not been thought of as a disease or illness that automatically needs treatment (Gignac et al., 2006; Jinks, Ong, & Richardson, 2007; Sanders et al., 2002). Additionally, decisions to consult have been based on subjective definitions of normal and abnormal symptoms (Grime et al.).

Furthermore, researchers have suggested that patients worry about “bothering” their general practitioner (GP) by consulting for joint pain (Mann & Gooberman-Hill, 2011, p. 966). People with joint pain have positioned other people’s serious (usually life-threatening) conditions as more in need of medical care; this then contributed to people deciding not to consult (Jinks et al., 2007). Moreover, people hold preformed beliefs about what medicine can offer if they were to consult for joint pain for the first time. Researchers have found that patients think GPs have a limited repertoire of treatments (Jinks et al., 2007; Sanders et al., 2002), a view that stems from stories shared within social networks (Maly & Krupa, 2007). In some cases lay understandings of OA have resulted in delays to treatment and a reduction in potential therapeutic and preventive benefits from self-management interventions (Sanders et al.).

Second, and overlapping with the above, health care professionals have acknowledged that guidelines for OA management are often not implemented and that patients with OA are not managed optimally (Mann & Gooberman-Hill, 2011). Related to this, people with a history of consulting their GP for joint pain have indicated ambivalence about reconsulting because they thought that they were not offered constructive advice. People perceived joint pain to be attributed to wear and tear or natural aging, were offered mostly pharmacological treatments (which patients were not always happy to take), or thought that the GP could offer little in the way of effective treatment or cure (Gignac et al., 2006; Jinks et al., 2007). Consequently, patients have interpreted that joint pain is an unimportant condition and that little can be done medically (Busby et al., 1997; Gignac et al.; Jinks et al., 2007; Maly & Krupa, 2007; Sanders et al., 2002).

Although previous research findings offered insights into why people had or had not chosen to consult or reconsult, a comprehensive theoretical framework for understanding help seeking for OA-related joint pain has not been developed (Busby et al., 1997; Gignac et al., 2006; Grime et al., 2010; Jinks et al., 2007; Mann & Gooberman-Hill, 2011; Sanders et al., 2002). Noting Calnan, Wainwright, O’Neil, Winterbottom, and Watkins’ (2007) suggestion that illness actions tend to be undertheorized, we have drawn on a study exploring patients’ self-management strategies and report on emergent findings relating to consultation decisions. We have explored people’s justifications for new consultations with their GP for joint pain and the effect of these on patients’ future likelihood of consultation.

We make an empirical and theoretical contribution to the field and suggest that help seeking for joint pain needs to be understood as a complex process (Biddle, Donovan, Sharp, & Gunnell, 2007; Calnan et al., 2007). We contend that particular attention needs to be paid to how people perceive the role of the GP and the moral discourses surrounding appropriate use of health services. Thus, we argue that understanding help seeking (either new or follow-up consultations) needs to be set against the dynamic interplay of individual meaning making, knowledge gained from social networks, relationships with health providers, and wider sociopolitical discourses. Taken together, these factors underpin a process of defining the utility and moral worth of consulting, and we suggest a theoretical framework for understanding decision making about help seeking. Finally, we outline how our findings have relevance to proposals to embed proposed systematic approaches to OA care into primary care settings (DoH, 2006; Porcheret, Healey, & Dziedzic, 2011).

Methods

Drawing From Grounded Theory

We conducted the study using some of the principles of grounded theory. Grounded theory was originally developed by Glaser and Strauss (1967), who required a rigorous model of analysis for qualitative researchers. The analytical practice of grounded theory involves repeated comparisons of transcripts by inductively closely coding data, focused recoding to organize initial codes and themes more conceptually, memo writing to aid the generation of themes and concepts, and ultimately development of a core theory or concept grounded in data. The process of constant comparison ensures continuity of coding, strength of interpretation and categorization, and theory building (Charmaz, 2006; Glaser & Straus).

Sampling and data collection in a grounded theory study are cyclical and intertwined. Sampling is distinguished between initial sampling, or the people who are identified as key to understanding the topic of investigation, and theoretical sampling. In other words, once preceding batches of data have been collected and analyzed, researchers will sample for participants to explore what might not be answered in earlier rounds of data collection; thus, the sampling strategy is theoretical. The goal of theoretical sampling is to ensure that emergent categories or themes are saturated and are thus robust (Charmaz, 2006; Glaser & Straus, 1967).

Competing derivatives of grounded theory have been developed in which the proponents differed in their stance regarding what constitutes appropriate use of the method (Charmaz, 2006). Charmaz argued that the procedural steps of grounded theory are a set of “principles and practices” (p. 9) that should be used flexibly to suit the circumstances and needs of individual research projects. Equally, she also emphasized the value of work that only uses “specific aspects of the approach” (p. 9).

Layder (1998) critiqued grounded theory for not incorporating previous knowledge and research. The focus on generating theory grounded in data excludes what has gone before, thus bracketing off useful opportunities to explore theoretical and empirical tensions (Layder). We followed the stance of Charmaz (2006) and used elements of grounded theory methodology to suit the nature of our study and the constraints we faced with regard to sampling (discussed in more detail below). We also followed Layder, remained alive to emergent findings, and tested findings against existing theories and ideas. Below we detail how we employed some of the principles of grounded theory in our study.

Sample and Recruitment

We report on findings that emerged from a study in which we investigated (a) whether nonconsulting people with knee joint pain engaged in any self-management; and (b) what factors promoted or inhibited self-management. We initially focused on this group because the knee is the most commonly affected joint site (Jinks et al., 2011) and there is evidence that people who do not consult their GP for joint pain are less likely to self-manage their knee pain (Jinks et al., 2007). We identified potential participants from respondents (N = 567) to a preexisting, separately funded, longitudinal survey of joint pain sufferers aged 50+ in the west Midlands region of the United Kingdom (Thomas et al., 2004). Potential recruits were identified using self-reported information collected in the survey questionnaire. Our sampling criteria included those who had not consulted for knee pain within the previous year and who indicated that they suffered from moderate or severe pain, based on self-completion of the Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index (Bellamy, 1996).

Finally, only those who had ticked a box on the questionnaire giving consent to be contacted about future studies were included in our sample frame; none of the survey participants had requested not to be contacted. We sent 112 out of the original 567 people who met our sampling criteria an invitation letter and information sheet about this study. The reality of contemporary research funding, research governance, and ethical regulation has often precluded undertaking lengthy theoretical collection of data (Barbour, 2001; Charmaz, 2006). This was the case in our study, and because of funding and resource constraints we could not undertake longitudinal theoretical sampling. Although we did not undertake theoretical sampling, we did, however, tailor questions and topics as an ongoing process of analysis and conducted interviews and diary studies in batches. This was a limitation of the study, and we offer additional reflections in the discussion.

Our final sample featured 22 participants who took part in the study (13 women, 9 men), with ages ranging from 56 to 90 years (mean = 66). We initially sampled for knee pain, but participants often had pain in multiple joint sites, which is common (Peat, Thomas, Wilkie, & Croft, 2006), and this was reflected in the final sample and findings. As the study progressed, two categories emerged from our data. Because we could identify only participants who had not consulted within the past year, 13 participants had visited their GP previously for chronic knee pain or other joint complaints, such as hip pain or hand pain; this group formed a consulting category. The remaining 9 participants had not consulted for musculoskeletal conditions at all and formed a nonconsulter category.

Data Collection

Prior to interviews taking place, written informed consent to participate and be audio recorded was obtained from participants. We obtained ethical approval from the local branch of a United Kingdom research ethics committee, and we worked to the principles laid out in the British Sociological Association’s (2002) code of ethical conduct. We collected data in three stages. First, participants were interviewed using a semistructured approach. A topic guide was used during baseline interviews (all interviews were conducted by the first author) to prompt discussion about the participants’ history and understandings of knee pain, their use of self-management, any previous consultations for joint pain, why they might start a new consultation for joint pain, and their expectations of consultations.

Second, we offered participants the opportunity to take part in a diary study for the 6 months following the baseline interview. Using diary methods allowed access to real-time accounts of daily life and managing illness rather than retrospective accounts provided by interviews (Milligan, Bingley, & Gatrell, 2005). Furthermore, insights into the ebbs and flows of illness experience and the strategies used by participants were obtained from completed diaries. Diaries also elicited everyday activities and events that could not be obtained in an in-depth interview. Material from the diaries helped guide conversations in the follow-up interviews (Milligan et al., 2005). Participants completed a diary for 1 week of their choosing each month for 6 months. Prompts were included with the diary which offered suggestions and direction to participants. Diaries were posted back to the researchers each month. Finally, we conducted a follow-up interview at 6 months.

Undertaking a follow-up interview offered the opportunity to gain greater depth of understanding and insights into the changing circumstances of participants (Murray et al., 2009) and complemented the use of a diary study (Milligan et al., 2005). We designed follow-up interviews after analysis of the baseline interviews and completed diaries to explore themes that emerged in more detail and to fill in gaps in knowledge. Data were collected between December 2008 and August 2009. Baseline and follow-up interviews were conducted in participants’ homes and lasted between .5 and 1.5 hours.

Saturation, in terms of being able to theoretically sample for different groups or cases and collect additional data, was not reached because of the constraints we operated under. However, interviews were conducted in batches to allow continuous coding and exploration of themes and topics that emerged. Not all of the participants took part in all stages of our fieldwork. Six participants (4 men, 2 women) participated in baseline interviews only; 1 woman completed a baseline interview and the diary study; 6 participants took part in baseline and follow-up interviews (3 men, 3 women); and 9 participants (2 men, 7 women) participated in baseline interviews, the diary study, and follow-up interviews.

Analysis

In line with the principles of grounded theory (Charmaz, 2006), we undertook initial close coding of interviews. Comparisons were made between the interviews to identify similarities and account for them. Initial codes were consolidated and developed into broader unifying themes. For example, we created initial codes relating to what patients thought would happen during consultations. These included “probable unwanted operation referral,” “offering only painkillers,” “would be dismissed with medications,” and “painkillers or nothing.”

In turn, we clustered the codes under the broader unifying theme of “perceptions of a limited repertoire for joint pain treatment.” Initial codes and themes were applied to diaries and follow-up interviews and corroborated or altered accordingly via the process of constant comparison. We also compared for changes in participants’ experiences or views on topics at different time points. This process was strengthened because we all undertook separate analysis, followed by team discussions to arrive at agreement regarding coding and interpretation (Green & Thorogood, 2004).

We maintained an audit trail of coding and recoding decisions. Memo writing helped to link conceptual thinking, coding, and recoding to the audit trail. During analysis we noted the overlap between themes and the cyclical nature of accounts of consulting. We arrived at a core concept of “defining the utility and moral worth of consulting”; we detail how we developed this concept at the end of the analysis section. Moreover, rather than solely attempting to identify a theory grounded in data, themes and the core concept were compared against existing theory and research findings (Layder, 1998) to help reach or reinforce a higher level of understanding. In the following section we report the conceptual themes we identified (and how they interconnect) before moving on to the discussion and using theory and previous research findings to help define the conceptual insight gained from the study.

Results

In this article we focus on people’s decisions about whether or not to consult a GP for their knee pain. Findings related to the everyday lay activity of self-management are reported elsewhere (Morden et al., 2011; Ong et al., 2011). Participants’ reasons for nonconsultation were multifactorial and overlapping; they included individual, organizational, and cultural elements. Our presentation of the research findings distinguishes between participants who had not previously consulted for knee pain or other musculoskeletal conditions and those who had. In doing so we highlight how people’s meaning making and reasoning about illness, what could be offered by health services, and the role of the GP were influenced by ongoing engagement with social contacts, health care, and broader societal discourses. In short, help seeking and illness actions were part of a complex and dynamic process.

Perceptions of a Limited Repertoire for Joint Pain Treatment

Participants with no history of consulting their GP for joint pain expressed that they thought the GP had little to offer them for pain over and above what they could do for themselves. One participant, a 90-year-old man, thought that consulting was pointless, stating, “Well, I come to the conclusion that they cannot do anything about it, unless I have an operation, you know. And I am a bit too old for that now.” He contextualized his statement against the consultation experiences of his friends and family who had been offered surgery. In the main, it appeared that being prescribed pain medications was interpreted as the only option for pain because this was what friends or family were offered when they consulted.

This influenced nonconsultation in one of two ways. First, participants discussed how using pain medications would not be effective or that they could be easily obtained without recourse to the GP. One participant, a 73-year-old man, framed his assertion against the experience of his wife, who had been prescribed easily procured pain medications by her GP for joint pain. He contended that seeing the GP would be ineffectual, and stated, “Painkillers are not doing anything at all. And that is all he would give me, you see.”

Second, pain medications were deemed undesirable because of side effects and negative interactions with other drugs. Participants did not think this would be a particularly helpful use of time and resources. A retired man (who also suffered from a heart condition that required a regimen of medications) commented,

Because I do not think he can do anything about it for me. They will just give you tablets, and I just do not like taking tablets. There are too many side effects with half of them. So, I just get on with it as long as I can cope. That’s it.

Again, the perception that pain medications were the only option was influenced by the experiences of family and friends. A subjective assessment of the ability to continue with usual valued activities (cope) when living with normal or accepted pain was set against the relative effectiveness or hazards of pain medications. This framed nonconsulters’ cost–benefit calculation of the utility of visiting a GP. Participants who had consulted indicated that they, too, had held similar reservations about the utility of consulting before they made the decision to do so.

Normal Symptoms, Disruption, and Consulting Behavior

Analysis revealed congruence between the accounts of consulters and nonconsulters regarding the role of symptoms and disruption influencing the decision to consult. One retired 71-year-old woman who had not consulted suggested that pain changing or intensifying, changes in self-management’s effectiveness, or mobility becoming impaired would be drivers to consult:

So it must not have been so bad to stop me from walking, but just to walk through it. No, I never saw the doctor about it. I am not saying I will not have to in future if it gets much worse, but it has got to keep me awake.

For individuals who had consulted, triggers mirrored the projected rationales of nonconsulters. These revolved around the onset of usually severe, unusual symptoms after a period of normal, expected joint pain. One example is a participant who worked part time providing care services for older adults. An unusual new development occurred when she was “washing a lady’s feet one day.” She experienced a sharp pain in her knee and could not straighten it. The incident triggered a consultation: “That day I had to ring me son to come and bring me home because it just would not unbend. It did the following morning. That was when I went up to see [Dr. Y].”

A man described how he had consulted with his GP for knee pain because of an accident that occurred doing his manual laboring job. This meant that his pain had become more severe than usual. Thus, the changed severity and the impact on his daily life beyond what he accepted as normal made him consult: “I have had to go to the doctors. I have been on ibuprofen so as I can sleep because I do not sleep now.” Thus, abnormal pain and disruptive symptoms made him consult and use what he considered to be strong prescription pain medications, which he had been averse to previously.

The reasons why people elected to consult mirrored what would make those who had not consulted see their GP. Participants made contextual judgments of normal symptoms and consulted when interference in normal life had become an issue. Thus, it was not deemed something that immediately warranted consultation until a process of self-treatments, adaptations (reported elsewhere; see Morden et al., 2011; Ong et al., 2011), and insufferable flare-ups (and associative social disruption) had occurred. However, consulting was framed and traded off against people’s views of the GP’s role and concerns about the judicious use of health care.

Not Bothering the Busy GP

Nonconsulting participants undertook a cost–benefit analysis in relation to help seeking. This was also influenced by the organizational context of general practice, perceptions of the GP being an expert, and making appropriate choices about consulting. For a small number of participants, usually those still in employment, the organization of general practice meant it was difficult to get appointments that suited them. One woman, who worked in a professional position, noted, “To be honest, it is a bind going to doctors because you cannot get an immediate appointment. You have got to go for open surgery [walk-in consultation], and you sit and wait, and they fit you in when they can.”

More pertinently, participants depicted GP time to be something precious which could be shortened by excessive patient demand; for example, “GPs are busy, and I do not want to bother them.” Thus, knee pain was defined as something that did not require patients to ask for the GP’s time, especially because the GP would offer pain medications, which patients could easily obtain. This acted as an individual rationing device and shaped what the participants considered sufficiently serious to warrant consultation and take up valuable GP time. This was not confined to just nonconsulters, and we return to the example of consulters below. In the following sections we focus on the experiences of those who had consulted their GP and the likelihood of them consulting again. We do this to map out the process of consultation decision making at varying stages of the patient journey.

An Untreatable and Unimportant Condition

Few participants described the outcome of previous consultations positively. GPs had sometimes referred patients for testing or to specialist services. Referral was satisfactory in some cases and offered reassurance, but for many patients it achieved little and acted as a disposal device (May et al., 2004). More commonly, participants reported being offered an explanation of joint pain being a degenerative process or age-related. For example, one participant detailed how “Dr. Z said it was just through wear and tear and there was not a lot we could do about it.” Another participant reported, “Well, they just say it is your age, wear and tear, and take these tablets.” Consequently, participants interpreted that little could be done for their complaint.

Another example was given by a 58-year-old man who worked as a mechanical engineer and had long-standing problems with hip and knee pain. He had consulted his GP because pain was interfering with his work, which required being able to climb up ladders and maneuver to look at faulty equipment:

When I asked the local GP about it he indicated that it was possibly that I’d got arthritis in the right knee as well. I asked whether there was anything that could be done and the answer was, “Do not think so.”

When the interviewer inquired whether he had received additional information, advice, or support, he replied, “One hundred percent no.” People concluded that it was pointless consulting because “[it] really seems to be an area where it is solely left to the individual. You know, my experience over the years has been that it is up to the individual.” The experiences of patients in our sample who chose to consult served to reinforce existing perceptions about the utility of going to see the GP, or added an extra disincentive to seek help in the future. Consequently, one participant, a 64-year-old woman, suggested that such an outcome “[just] makes you feel as if you might as well have not bothered to go.” This ultimately meant that these participants had become very reluctant to seek help in the future because of the perceived relative unimportance GPs attributed to the condition and the lack of options offered. Arguably, participants who had not consulted at the time of interview but who chose to in the future would reach similar conclusions.

Consultations Reinforcing Not Bothering the Busy, “Expert” GP

The outcomes of consultations had a bearing on how patients positioned GPs in terms of expertise and trustworthiness. Participants either lost faith in the GP and sometimes questioned their expertise, or they depicted GPs as experts who were short of time. Both perspectives shaped the reluctance of patients to consult for joint pain in the future. Two participants expressed particular disenchantment because of their experiences.

The aforementioned man who had knee and hip pain that interfered with his work argued that going beyond the GP was required to deal with joint pain. His argument was contextualized against his extensive contact with consultant surgeons about eventual hip surgery. He said, “I think I would honestly say, without being detrimental to the GP, they are what they say. They are a general practitioner.” A woman was dubious about her designated GP rather than about all clinicians. She detailed how her disenchantment related to her husband passing away:

I do not think the doctor helps, no. He just says, “Wear and tear, age, go away and wait!” I have not got much faith in my doctor. I ought to change him, really. When he told me, when my husband had got seven cancers on the brain and he told me he was depressed, you lose all faith.

In the case of these patients, they had become extremely reluctant to reconsult because the trust and faith in the expertise of all or individual GPs had been undermined. However, despite patients thinking that little could be done for joint pain, the remainder of those who had previously sought help maintained a view that GPs are experts, which was similar to the view of those who had not consulted. Furthermore, they also invoked the everyday organizational and resource constraints applicable to general practice. In other words, participants suggested that GP time should not be wasted and that consultations should be reserved for “real” clinical problems. One man considered everyday knee pain sufficiently routine to ask the chemist1 about. He defined the expertise and time of the GP to be much more valuable than that of the pharmacist:

The doctors are the experts. The chemists are very helpful in a lot of ways; anything I’ve got which isn’t too serious, I do not personally think is too serious, I will ask the chemist about it, and if it is something that he cannot do anything about or he cannot do without a prescription, he will tell me to go and see the doctor, which is fair enough. I do not believe in wasting the doctor’s time on trivial things when somebody else can do it for you. Just a few questions, and it’s done.

This selective approach to consultation was described by many participants, with the pharmacist being the first port of call for pain relief (such as gels or over-the-counter medication). Another participant, a retired 66-year-old woman, suggested that dealing with problems relating to knee pain was something outside of the remit of GPs. This, in part, was because of previous experience of consulting. She asserted, “No, basically, common sense isn’t it, er, doctors are always very busy. I mean you’re limited to five minutes when you go in.” Participants were reluctant to bother the doctor again because previous consultations engendered the idea that only limited medical treatments and advice were available.

One woman’s observation about joint pain was situated against the number of tests (monitoring) and treatments she had received for other chronic conditions such as diabetes, asthma, and cholesterol. Consequently, she positioned other conditions to be more worthy of limited practitioner time and intimated it would be inappropriate to reconsult: “I do not know what to do any more. And as I say, I do not like to mither me [bother my] doctor. He’s got enough to do.” Another example is that of a woman who suggested that there was no support available for joint pain because of the limited treatment options available, and she therefore avoided the risk of annoying her doctor with “inappropriate” appointments:

I do not go to the doctor with everything, I do not. Because I do not want the doctor to get fed up of me, anyway. I do not want the doctor to think, “Oh, she’s here again.” I think I am a bit sensitive of what the doctor might think: “Oh blimey [a British expression of surprise or alarm], she’s here again.”

The perceptions that GPs were busy and time pressed and should not be bothered by trivial complaints suggested that the participants made a moral judgment call when deciding to consult; however, this was additionally contextualized by previous experiences of consultations for joint pain. Thus, participants interpreted that they had visited the doctor with a minor complaint for which few treatment options were on offer.

Arriving at a Core Concept: Defining the Utility and Moral Worth of Consulting

The themes we identified during analysis revealed that deciding to consult involved weighing the potential outcomes of consultations; the effectiveness of existing strategies; the influence of unusual symptoms and disruptions in daily life; worries about taking up valuable GP time; the outcome of previous consultations positioning joint pain as unimportant; and the impression that it would be inappropriate to consume the time of a hard-pressed GP with a condition which is trivial.

During the process of analysis, we compared how themes related to one another conceptually and in terms of temporality, sequence of events, and causality. The themes we detail did not exist in isolation from one other in relation to people’s accounts. We realized that the themes detailed two concepts: utility and morality in relation to consulting. Furthermore, we recognized that collectively they revealed a series of intertwined, longitudinal, and cumulative actions and events. In other words, they painted a picture of individual agency set among ongoing, interlinked social processes that revealed a dynamic set of tensions which framed help seeking. If these factors are taken together, we suggest that the temporal interconnections between themes detail how participants engaged in an ongoing process of defining the utility and moral worth of consulting.

Discussion

We have situated the themes and the core concept against existing sociological literature. We have done this to reinforce the salience of a dynamic process (Calnan et al., 2007) of defining the utility and moral worth of consulting to explain illness actions in relation to joint pain. Sociologists have suggested that networks or social relationships with peers, relatives, or cultural groups mediate beliefs about possible treatments for illness (Biddle et al., 2007; Young, 2004). Participants who had not consulted previously with their GP for joint pain outlined how they thought that the GP would not be able to offer much help and would only provide a limited repertoire of treatments (Jinks et al., 2007; Maly & Krupa, 2007). This initially dissuaded participants from consulting because they deemed that it would be a waste of time, that only pain medications would be offered (which were easily obtainable anyway), or that treatments would have unpleasant side effects (Pound et al., 2005).

The perception of limited treatment options was influenced by the experiences of family and friends (Maly & Krupa, 2007). Consequently, if people thought that they could cope with what they deemed “normal” pain (Grime et al., 2010) and avoid using pain medications, then they would not necessarily consult. It has been argued that the explanation and meaning that patients give to their condition directly influences the relationships that the ill have with health care services (Biddle et al., 2007). Our analysis resonated with previous research; namely that chronic joint pain was normalized by relating it to aging (Sanders et al., 2002), and it was when pain was different (or out of the norm) and caused disruption that people considered consulting (Grime et al.).

We have previously reported that participants had often worked through a repertoire of existing self-management strategies (Morden et al., 2011; Ong et al., 2011). The exhaustion of patient-led effective strategies for ameliorating symptoms and disruption to everyday life seemed to be central in tipping the balance in favor of consulting (Calnan et al., 2007). However, consulting was a big decision for participants because they harbored concerns about wasting precious GP time, which confirmed previous findings (Mann & Gooberman-Hill, 2011). In some respects, this reflected Jinks and colleagues’ (2007) findings that people make social comparisons to determine the perceived seriousness and relative worth of illnesses; in turn, moral judgments about consulting appropriately are made.

In this case, participants considered GPs to be experts who should only be approached with serious problems. The ability to legitimate illness or disease (or otherwise) has helped to maintain the status and authority of doctors at a societal level (Jutel, 2009), with the GP in particular a powerful, readily acknowledged expert in and gatekeeper to treatment and diagnosis (Pilnick & Dingwall, 2011). In other words, the acknowledgment of medical expertise framed participants’ views about doctors as a social entity. Because participants considered the GP to be an expert, decisions were set against the idea that GP time was precious and not to be wasted.

Furthermore, McDonald and colleagues’ (2007) study highlighted macro sociopolitical factors that influenced why patients chose to consult. Rather than situate the debate against interactions between patients and GPs, they provided a Foucauldian analysis to suggest that people framed the decision to consult against contemporary discourses of choice and self-responsibility in an era of strained health care resources. Sitting alongside this concern was patients’ awareness that using scant resources deprived others of services. Thus, macro sociopolitical factors permeated help seeking and made it a moral and ethical endeavor of proving oneself to be an upstanding citizen by using health care only when absolutely necessary (McDonald et al.).

Service organization and long-term relationships with health care practitioners (and in this case GPs specifically) have influenced how people perceived and defined the meaning of chronic conditions, often shaping how people prioritized them; this has then affected future service utilization (Lawton, Peel, Parry, Araoz, & Douglas, 2005). One tentative interpretation of accounts might be that when people had decided to consult, GPs were either not aware of the NICE OA guidelines (NICE, 2008) or had not fully implemented them. However, this is a cautious interpretation because we did not have access to the GPs’ perspectives on consultations, but it would corroborate previous research (Mann & Gooberman-Hill, 2011; Porcheret et al., 2011). What is clear is that the outcome of consultations meant that patients thought that nothing could be done and accepted pain medications, or just got on with life despite their pain even though they considered it problematic. It seemed that many people opted for the latter situation.

In this instance, the encounters with GPs served to reinforce the interpretation that OA was an unimportant condition for which little could be done (Busby et al., 1997; Gignac et al., 2006; Jinks et al., 2007; Sanders et al., 2002) and which in turn reinforced people’s reluctance to consult for joint pain. In some cases this helped to damage the position of GPs in terms of being experts and reduced patients’ trust. However, for most participants the outcome of consultations had not disrupted the perception that GPs are experts; rather, they overlapped with how people perceived health care (and general practice in particular) to be hard pressed in terms of resources. In other words, GP advice that joint pain was related to “wear and tear” and “aging,” which might have been intended to provide reassurance (Donovan & Blake, 2000), was interpreted as meaning that nothing could be done. In turn, there was a reinforcement of patient perceptions that consulting experts should be reserved for serious problems (Jinks et al., 2007) to avoid placing unwarranted pressure on health care services (McDonald et al., 2007).

Some of our findings resonated with previous research into consulting for joint pain (Busby et al., 1997; Gignac et al., 2006; Grime et al., 2010; Jinks et al., 2007; Mann & Gooberman-Hill, 2011; Sanders et al., 2002); however, much of this corpus of literature (Sanders et al. aside) has not offered a cogent theoretical perspective to explain people’s actions. We acknowledge that behavioral models for understanding patient help seeking exist (Anderson, 1995), but they have been critiqued for being static and linear and based on using predictive sociodemographic variables (Biddle et al., 2007; Pescosolido, Gardner, & Lubell, 1998). Sociologists have argued that help seeking and illness actions are a process rather than being static or linear (Biddle et al.; Calnan et al., 2007), and thus feature cyclical stages that are likely to be repeated.

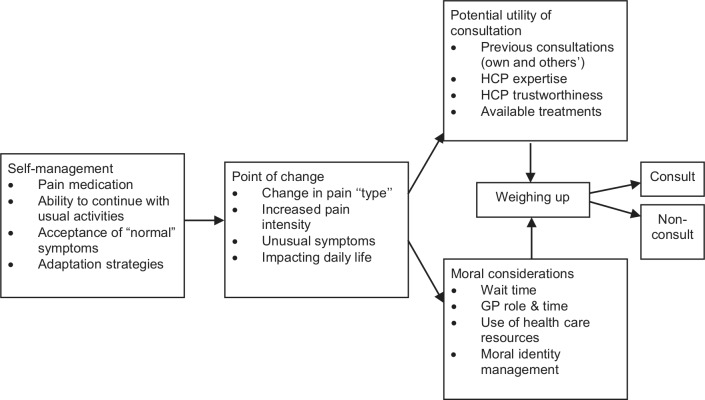

We suggest that help seeking for OA features interplay between individual meaning making, knowledge from social relationships, relationships with health services, and wider sociopolitical discourses. Thus, we infer from our findings and existing theory that people’s decision making about joint pain consultations is a dynamic, interwoven process of defining the utility and moral worth of consulting. Accordingly, we offer a theoretical framework for understanding this process (see Figure 1). In summary, help seeking for OA is a process that features a series of ongoing negotiations and assessments. These have to be understood and taken into account when exploring illness actions and help seeking.

Figure 1.

Theoretical model: The process of defining the utility and moral worth of consulting.

Note. HCP = health care providers; GP = general practitioner.

Self-management is an activity that features a mix of lay activities and recursive use of services for support, additional treatments, and advice. Therefore, it is important that services are responsive to patient needs (Kennedy et al., 2007). Thus, although it is necessary to understand patients’ existing self-management strategies and their likely support needs (Morden et al., 2011; Ong et al., 2011), we contend that understanding help seeking to be a discrete but complementary issue is also important. This is because it has implications for clinical practice and the promotion of self-management support if and when patients need help from health care.

In the case of OA, set against clinical recommendations to provide supported self-management, recognition is needed that past consultations and the existing sociopolitical context are likely to influence future consultation behavior and expectations. This then has a bearing on initial attempts to change current practice and how clinicians describe, diagnose, and treat joint pain (Porcheret et al., 2011). Failing to maintain congruence for the patient could be detrimental to the outcomes of consultations (Grime et al., 2010); but equally, leaving the patient with the idea that little can be done and that the pain is unimportant could have deleterious future consequences. Thus, joint pain consultations need to be carefully managed by GPs.

Accordingly, we recommend that GPs thoroughly discuss treatment options and self-management—for example weight-loss strategies and structured exercise—where necessary; avoid using terminology such as “wear and tear” and ascribing joint paint to getting older; and work to ensure that patients think that their complaint is valid and important (Steihaug & Malterud, 2002). Additions to guidelines that emphasize the impact of the above on patients might be of benefit to GPs and patient care. Equally, recognition is needed that current United Kingdom policies and health care organization might restrict the ability of GPs to act on such recommendations. This is because the current United Kingdom system is geared toward time-limited consultations and quality-measurement systems that do not feature musculoskeletal conditions (Steel, Maisey, Clark, Fleetcroft, & Howe, 2007). A broader focus that takes health care context into account is required to address such issues.

Our study has limitations that must be acknowledged. The first is that we did not possess GPs’ accounts of consultations and thus were reliant on patients’ interpretations of events. Because we could not include the GPs’ accounts and interpretations of consultations, we recognize that accounts of interactions were partial and restricted to the meaning that patients placed on them. The second limitation relates to the constraints on funding and resources. This limited our ability to undertake theoretical sampling and recruit additional participants to explore findings in more detail. In particular, we could not obtain detailed data from ethnic minority groups, people who were aged between 45 and 55 years, or those who were, epidemiologically speaking, at the younger end of the population that encounters joint pain (NICE, 2008). This potentially obscured cultural and intergenerational factors, which might need to be explored and accounted for. However, we contend that the findings provide a theoretical framework that provides “conceptual generalizability” (Green & Thorogood, 2004, p. 197) which can be tested in future research on joint pain or other conditions.

Conclusion

This study’s findings highlight the dynamic interplay between how people contextualize illness in micro settings, the influence of interactions with health care services on illness actions, the continued understanding that GPs are holders of expert knowledge and authority, and the macro sociopolitical factors and associated morality concerns that play a role in people’s decisions to seek help. Previous attempts to understand illness actions have tended to focus on one or two of these factors. Optimizing the outcomes of consultations and self-management requires an understanding of how people balance the utility and moral worth of consulting and the complexities of why patients seek help.

Acknowledgments

We thank Janet Grime for many insightful discussions, and all the participants for their willingness to take part in the study.

Author Biographies

Andrew Morden, PhD, is a research associate at the Research Institute for Primary Care & Health Sciences, Keele University, Staffordshire, United Kingdom.

Clare Jinks, PhD, is a senior lecturer in health services research at the Research Institute for Primary Care & Health Sciences, Keele University, Staffordshire, United Kingdom.

Bie Nio Ong, PhD, is a professor of health services research at the Research Institute for Primary Care & Health Sciences, Keele University, Staffordshire, United Kingdom.

In the United Kingdom the term chemist is a colloquialism for pharmacist.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: Support was received from the National Institute for Health Research (NINR), Research for Patient Benefit program (grant number PB-PG-0107-11221). The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the National Health Service, the NIHR, or the Department of Health.

References

- Anderson R. M. (1995). Revisiting the behavioral model and access to medical care: Does it matter? Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 36, 1–10 Retrieved from www.jstor.org/stable/2137284 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arthritis Care. (2012). OA Nation 2012. Retrieved from www.arthritiscare.org.uk/LivingwithArthritis/oanation-2012

- Barbour R. (2001). Checklists for improving rigour in qualitative research: A case of the tail wagging the dog? BMJ, 322, 1115–1117. 10.1136/bmj.322.7294.1115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bedson J., Mottram S., Thomas E., Peat G. (2007). Knee pain and osteoarthritis in the general population: What influences patients to consult? Family Practice, 24(5), 443–453. 10.1093/fampra/cmm036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellamy N. (1996). WOMAC osteoarthritis index. A users guide. London, ON, Canada: University of Western Ontario. [Google Scholar]

- Biddle L., Donovan J., Sharp D., Gunnell D. (2007). Explaining non-help-seeking amongst young adults with mental distress: A dynamic interpretive model of illness behaviour. Sociology of Health and Illness, 29(7), 983–1002. 10.1111/j.1467-9566.2007.01030.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- British Sociological Association. (2002). Statement of ethical practice for the British Sociological Association. Retrieved from www.britsoc.co.uk/NR/rdonlyres/801B9A62-5CD3-4BC2-93E1-FF470FF10256/0/StatementofEthicalPractice.pdf

- Busby H., Williams G., Rogers A. (1997). Bodies of knowledge: Lay and biomedical understandings of musculoskeletal disorders. In Elston M. A. (Ed.), The sociology of medical science & technology (pp. 79–99). Oxford: Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Calnan M., Wainwright D., O’Neill C., Winterbottom A., Watkins C. (2007). Illness action rediscovered: A case study of upper limb pain. Sociology of Health and Illness, 29(3), 321–346. 10.1111/j.1467-9566.2007.00543.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charmaz K. (2006). Constructing grounded theory: A practical guide through qualitative analysis. London: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Department of Health. (2006). The musculoskeletal services framework. A joint responsibility: Doing it differently. London: HMSO. [Google Scholar]

- Donovan J. L., Blake D. R. (2000). Qualitative study of interpretation of reassurance among patients attending rheumatology clinics: “Just a touch of arthritis, doctor?” British Medical Journal, 320(7234), 541–544. 10.1136/bmj.320.7234.541 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gignac M. A. M., Davis A. M., Hawker G., Wright J. G., Mahomed N., Fortin P. R., Badley E. M. (2006). “What do you expect? You’re just getting older”: A comparison of perceived osteoarthritis-related and aging-related health experiences in middle- and older-age adults. Arthritis Care and Research, 55(6), 905–912. 10.1002/art.22338 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glaser B., Strauss A. (1967). The discovery of grounded theory. Chicago: Aldine. [Google Scholar]

- Green J., Thorogood N. (2004). Qualitative methods for health research. London: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Grime J., Richardson J. C., Ong B. N. (2010). Perceptions of joint pain and feeling well in older people who reported to be healthy: A qualitative study. British Journal of General Practice, 60(577), 597–603. 10.3399/bjgp10X515106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holden D. M., Nicholls M. E., Young M. J., Hay P. E., Foster P. N. (2012). The role of exercise for knee pain: What do older adults in the community think? Arthritis Care and Research, 64(10), 1554–1564. 10.1002/acr.21700 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jinks C., Ong B. N., Richardson J. (2007). A mixed methods study to investigate needs assessment for knee pain and disability: Population and individual perspectives. BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders, 8(59), 1–9. 10.1186/1471-2474-8-59 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jinks C., Vohora K., Young J., Handy J., Porcheret M., Jordan K. P. (2011). Inequalities in primary care management of knee pain and disability in older adults: An observational cohort study. Rheumatology, 50(10), 1869–1878. 10.1093/rheumatology/ker179 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jutel A. (2009). Sociology of diagnosis: A preliminary review. Sociology of Health and Illness, 31(2), 278–299. 10.1111/j.1467-9566.2008.01152.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendall E., Rogers A. (2007). Extinguishing the social?: State sponsored self-care policy and the Chronic Disease Self-management Programme. Disability and Society, 22(2), 129–144. 10.1080/09687590601141535 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy A., Rogers A., Bower P. (2007). Support for self care for patients with chronic disease. British Medical Journal, 335(7627), 968–970. 10.1136/bmj.39372.540903.94 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawton J., Peel E., Parry O., Araoz G., Douglas M. (2005). Lay perceptions of type 2 diabetes in Scotland: Bringing health services back in. Social Science and Medicine, 60(7), 1423–1435. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.08.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Layder D. (1998). Sociological practice. London: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Lubar D., White P. H., Callahan L. F., Chang R. W., Helmick C. G., Lappin D. R., Waterman M. B. (2010). A national public health agenda for osteoarthritis 2010. Seminars in Arthritis and Rheumatism, 39(5), 323–326. 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2010.02.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maly M. R., Krupa T. (2007). Personal experience of living with knee osteoarthritis among older adults. Disability and Rehabilitation, 29(18), 1423–1433. 10.1080/09638280601029985 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mann C., Gooberman-Hill R. (2011). Health care provision for osteoarthritis: Concordance between what patients would like and what health professionals think they should have. Arthritis Care & Research, 63(7), 963–972. 10.1002/acr.20459 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- May C., Allison G., Chapple A., Chew-Graham C., Dixon C., Gask L., Roland M. (2004). Framing the doctor-patient relationship in chronic illness: A comparative study of general practitioners’ accounts. Sociology of Health and Illness, 26(2), 135–158. 10.1111/j.1467-9566.2004.00384.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald R., Mead N., Cheraghi-Sohi S., Bower P., Whalley D., Roland M. (2007). Governing the ethical consumer: Identity, choice and the primary care medical encounter. Sociology of Health and Illness, 29(3), 430–456. 10.1111/j.1467-9566.2007.00493.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milligan C., Bingley A., Gatrell A. (2005). Digging deep: Using diary techniques to explore the place of health and well-being amongst older people. Social Science and Medicine, 61(9), 1882–1892. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.04.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morden A., Jinks C., Ong B. N. (2011). Lay models of self-management: How do people manage knee osteoarthritis in context? Chronic Illness, 7(3), 185–200. 10.1177/1742395310391491 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morden A., Jinks C., Ong B. N. (2013). “…I’ve found once the weight had gone off, I’ve had a few twinges, but nothing like before.” Exploring weight and self-management of knee pain. Musculoskeletal Care, 12(3), 63–73. 10.1002/msc.1054 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray S. A., Kendall M., Carduff E., Worth A., Harris F. M., Lloyd A., Sheikh A. (2009). Use of serial qualitative interviews to understand patients’ evolving experiences and needs. British Medical Journal, 339(b3702), 958–960. 10.1136/bmj.b3702 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. (2008). Osteoarthritis: National clinical guideline for care and management in adults. Retrieved from www.nice.org.uk/nicemedia/live/11926/39557/39557.pdf

- Ong B. N., Jinks C., Morden A. (2011). The hard work of self-management: Living with chronic knee pain. International Journal of Qualitative Studies of Health and Well-being, 6(3), 1–10. 10.3402/qhw.v6i3.7035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peat G., Thomas E., Wilkie R., Croft P. (2006). Multiple joint pain and lower extremity disability in middle and old age. Disability and Rehabilitation, 28(24), 1543–1550. 10.1080/09638280600646250 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pescosolido B. A., Gardner C. B., Lubell K. M. (1998). How people get into mental health services: Stories of choice, coercion and “muddling through” from “first-timers.” Social Science and Medicine, 46(2), 275–286. 10.1016/S0277-9536(97)00160-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pilnick A., Dingwall R. (2011). On the remarkable persistence of asymmetry in doctor/patient interaction: A critical review. Social Science and Medicine, 72(8), 1374–1382. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.02.033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porcheret M., Healey E., Dziedzic K. S. (2011). Uptake of best arthritis practice in primary care—No quick fixes. Journal of Rheumatology, 38(5), 791–793. 10.3899/jrheum.110093 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pouli N., Das Nair. R., Lincoln N. B., Walsh D. (2013). The experience of living with knee osteoarthritis: Exploring illness and treatment beliefs through thematic analysis. Disability and Rehabilitation, 36(7), 600–607. 10.3109/09638288.2013.805257 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pound P., Britten N., Morgan M., Yardley L., Pope C., Daker-White G., Campbell R. (2005). Resisting medicines: A synthesis of qualitative studies of medicine taking. Social Science and Medicine, 61(1), 133–155. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.11.063 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanders C., Donovan J., Dieppe P. (2002). The significance and consequences of having painful and disabled joints in older age: Co-existing accounts of normal and disrupted biographies. Sociology of Health and Illness, 24(2), 227–253. 10.1111/1467-9566.00292 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Steel N., Maisey S., Clark A., Fleetcroft R., Howe A. (2007). Quality of clinical primary care and targeted incentive payments: An observational study. British Journal of General Practice, 57(539), 449–454 Retrieved from www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2078183/ [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steihaug S., Malterud K. (2002). Recognition and reciprocity in encounters with women with chronic muscular pain. Scandinavian Journal of Primary Health Care, 20(3), 151–156. 10.1080/028134302760234591 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas E., Wilkie R., Peat G., Hill S., Dziedzic K., Croft P. (2004). The North Staffordshire Osteoarthritis Project—NorStOP: Prospective, 3-year study of the epidemiology and management of clinical osteoarthritis in a general population of older adults. BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders, 5(2). 1–7. 10.1186/1471-2474-5-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young J. T. (2004). Illness behaviour: A selective review and synthesis. Sociology of Health and Illness, 26(1), 1–31. 10.1111/j.1467-9566.2004.00376.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]