Abstract

Background

Older patients who receive hematopoietic cell transplantation (HCT) may be at risk for adverse outcomes due to age-related conditions or frailty. Geriatric assessment (GA) has been used to evaluate HCT candidates but can be time-consuming. We therefore sought to determine the predictive ability of two screening tools, the Vulnerable Elders Survey (VES-13) and the G8, for abnormal GA or frailty.

Materials and Methods

We enrolled 50 allogeneic HCT candidates age ≥60 years. The GA included measures of medical, physical, functional, and social health. Frailty was defined as 3 or more abnormalities on grip strength, gait speed, weight loss, exhaustion, and activity. We associated baseline characteristics and abnormal GA or frailty. We determined the sensitivity and predictive ability of the VES-13 and G8 for GA and frailty.

Results

Overall, 33 (66%) patients (mean age 65.4 years) had an abnormal GA, and11 patients (22%) were frail. The G8 screening tool had a higher sensitivity for an abnormal GA (69.7%), and the VES-13 had a higher specificity (100%). Both tools had similar discriminatory ability.

Conclusions

Older HCT candidates had a significant number of deficits on baseline GA and a high prevalence of frailty. Existing screening tools may not be able to replace a full GA.

Keywords: geriatric assessment, stem cell transplantation, screening tools, elderly, frailty

1. Introduction

Increasingly, older patients have been considered candidates for allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation (HCT).[1, 2] Due to reduced-intensity and nonmyeloablative strategies as well as improvements in supportive care, older persons have attained survival rates that compare reasonably to those in younger patients.[3] In addition, older persons have been carefully selected for HCT based on disease status, comorbidity, and performance status.[4] Patients 55 and older treated for acute myelogenous leukemia (AML) or myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS) with HCT had a 2-year overall survival of 46%, with a 100-day mortality rate of 6%.[5] Transplant-related mortality (TRM) rates in persons 60 and older were not significantly different from patients 50 to 60 years,[6] with TRM rates of 5% at 100 days and 19% at 1 year.[5]

Geriatric assessment (GA) could be incorporated into existing HCT care to identify patients with an increased risk of adverse outcomes.[7, 8] While higher comorbidity burden has been associated with poorer outcomes in HCT patients,[9] older persons are also at risk for other age-related conditions and geriatric syndromes associated with poor outcomes that are not routinely assessed as part of a pre-HCT evaluation.[7] GA is a multidimensional assessment not only of comorbidity, but also of other medical, social, functional, psychological risk factors in older persons.[10] GA has been validated in community dwelling older adults and in populations of older persons with cancer to identify those at increased risk of chemotoxicity, perioperative complications, disability, and mortality.[11, 12] A recent study of GA in HCT found that a substantial number of older HCT patients had comorbidity, functional limitations, and frailty, a syndrome characterized by weakness, slow gait, malnutrition, low activity level, and exhaustion.[13]

In the coming decades, the substantial increase in the older population with cancer will mean that greater numbers of older persons who may be frail or have underlying deficits may be considered for HCT. Thus, a strategy to determine patients that are fit enough for HCT could aid in treatment decision-making. However, a GA can be time-consuming and requires the input of a multidisciplinary team that includes healthcare professionals trained in the care of older persons. Thus, a screening tool that helps to determine which patients are likely to benefit from GA would be useful to select patients for this intervention. Two such screening tools, the Vulnerable Elders Survey (VES-13)[14] and the G8 Screening Tool,[15, 16] have been evaluated in older patients with cancer, but have not been adopted widely for older patients being considered for HCT.[17, 18]

As part of a longitudinal pilot study to determine whether HCT was associated with the development of frailty and functional deficits in older persons, we performed a baseline assessment for older persons that included GA and assessment for the frailty syndrome. Our purpose in this cross-sectional study was to determine the utility of the VES-13 and the G8 screening tool score to identify patients who are likely to have an abnormal GA or the presence of the frailty syndrome.

2. Patients and Methods

2.1. Study Subjects

Our study included patients evaluated in the Stem Cell Transplantation and Cellular Therapy Center at the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center between June 2010 and August 2012. We approached patients who were 60 years of age and older and English speaking who were considered for allogeneic HCT to treat hematologic disorders. We chose adults 60 and older as a group who benefit from reduced intensity induction strategies but also still have an increased risk of age-related illness.[19] All eligible patients were approached after their primary oncologic team determined that they were eligible for allogeneic HCT. An independent study coordinator collected all study data at a regularly scheduled visit prior to admission for HCT. The UT MD Anderson Cancer Center Institutional Review Board approved the study, and all enrolled subjects provided written informed consent prior to participation in the study.

2.2. Measures

All subjects completed a baseline evaluation, which included collection of demographic data and completion of a geriatric assessment (GA), Vulnerable Elders Survey (VES-13), and a frailty index. Demographic data included age, sex, race, marital status, education, and employment. Body mass index, disease status, and Karnofsky performance status were determined by the oncology team and were obtained from medical records through chart review after the baseline evaluation. Disease status at HCT was defined using established criteria based on bone marrow morphology. Criteria for response included normal cytogenetics, absence of circulating blasts, <5% marrow blasts, and platelet count ≥100 × 109/L. Laboratory values for ferritin, vitamin D, B-type natriuretic peptide, and C-reactive protein were also collected when available.

The primary outcome for the study was an abnormal GA, based on having 2 or more abnormal domains on GA prior to HCT. The GA included 8 domains: comorbidity, polypharmacy, nutritional status, physical performance, functional status, social support, psychological status, and cognition. Each domain was assessed using validated tools. We based our selection of tools and cut-off scores for each domain on previous studies of GA in older persons with cancer.[20] Where possible, we used tools that were either specific for the HCT population or had been used in an HCT population previously. For some GA domains that had not been assessed in HCT, we chose tools that might reasonably be sensitive and specific measures for deficits, with the understanding that the pre-HCT population may be a very highly select group of fitter patients. For example, in assessing cognitive function, we expected mild changes in various cognitive domains and would have preferred to screen for abnormalities in multiple cognitive areas.[21] However, to keep the GA to a reasonable length, we focused on brief measures of executive dysfunction, which has been described after HCT.[22] Thus, the Trail Making Tests A and B, which have been employed in the HCT population,[23] as well as the CLOX (a clock draw test), [24] which has not been used in HCT previously, were used. The summary of tools used for each domain is shown in Table 1. The GA was considered abnormal if a patient scored in the abnormal range for 2 or more of the different domains. Although this cutoff for abnormal GA has not been validated in HCT patients, a cutoff of 2 or more abnormalities on GA has been used in other studies of GA in geriatric oncology populations.[25]

Table 1.

Tools Used in the Geriatric Assessment (GA)

| Domain | Measure | Cutoff Score |

Score Range |

Description | Justification for Use in GA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Comorbidity | HCT-CI[9] | ≥3 | 0–3 | Scale that includes 17 comorbidities, organized by system. | Higher scores associated with increased risk of non-relapse mortality and decreased overall survival in HCT patients.[26, 27] |

| Polypharmacy | Medication Number | ≥9 | N/A | Number of different regularly scheduled medications (excluding as-needed medications). | Increased medication number is associated with an increased risk of adverse drug events and inappropriate medication use in the general geriatric population.[28, 29] |

| Nutritional Status | MNA[30] | <24 | 0–30 | A survey including questions on self-rated health, nutrition intake, mobility, and measures of calf and arm circumference. | A MNA score <24 had a sensitivity of 93% and specificity of 82% for nutritional deficiency in older patients with cancer.[31] |

| Physical Performance | SPPB[32] | <10 | 0–12 | Includes tests of balance, gait speed, and lower extremity strength | Scores of <10 are associated with an increased risk of disability and mortality.[32, 33] |

| Functional Status | ADL[34] | <12 | 0–12 | Ability to bathe, dress, toilet, transfer, maintain continence, and self-feed. | Impairments in ADLs and IADLs are closely associated with poor performance status in older patients cancer.[35, 36] Impaired functional status has been associated with adverse outcomes in older patients with cancer.[37, 38] |

| IADL[39] | Women: <16 Men: <8 |

0–16 | Ability to use the telephone, use transportation, maintain finances, manage medications, go shopping, do cooking, cleaning, and laundry. | ||

| Social Support | MOS[40] | <95 | 0–95 | Survey containing 19 items on emotional/informational, tangible, and affectionate support and positive social interaction. | Poor social support is associated with several psychosocial problems among older adults.[40, 41] HCT requires full support of a family member of caregiver to assist with transportation, medication monitoring, and to provide caregiving.[42] |

| Psychological Status | HADS-Anxiety and Depression[43] | >10 for each subscale | 0–21 | Survey with 7 anxiety and 7 depression questions, each scored 0 to 3. | Psychosocial distress is a significant factor in HCT patients and has been associated with increased risk of mortality.[44] [45] |

| Cognition | CLOX 1 and CLOX 2[24] | <11 for 1 <13 for 2 |

0–15 | A clock drawing test that is repeated after administrator instruction. | Cognitive changes in patients who undergo HCT may be mild and some may be reversible, including impairments in memory, processing speed, attention, concentration, and executive function.[21] |

| TMTA and TMTB[46] | >78 for TMTA >273 seconds for TMTB | N/A | Tests of the time it takes to connect a series of numbers, followed by a series of numbers and letters. |

Abbreviations: HCT-CI, Hematopoietic and Cellular Therapy-Comorbidity Index; MNA, Mini-Nutritional Assessment; SPPB, Short Physical Performance Battery; ADL, Activities of Daily Living; IADL, Instrumental Activities of Daily Living; MOS, Medical Outcomes Survey; HADS, Hospitalized Anxiety and Depression Scale; CLOX, Clock Draw Test; TMTA, Trail Making Test A; TMTB, Trail Making Test B

A secondary outcome was the prevalence of frailty based on the number of deficits on a frailty index at baseline. We used Fried’s criteria to determine frailty, which includes grip strength, gait speed, weight loss, low physical activity, and exhaustion.[47] A score of 3 or more abnormal tests defines the presence of frailty. Frailty is associated with increased risk of morbidity and mortality in community dwelling elderly persons and in older persons with cancer.[48–50]

We evaluated the ability of two screening tools to identify an abnormal GA and to identify individuals with the frailty syndrome. The VES-13 is a 13-item survey including age, self-rated health, and functional status, and is scored from 0 to 10, with 10 being the worst.[14] A cutoff of 3 or higher is considered abnormal, and each additional point on the VES-13 is associated with an incrementally higher risk of functional decline and mortality in community dwelling elders.[51] The G8 screening tool was developed for use in older persons with cancer, and includes items on age, self-rated health, nutrition, mobility, and medication use, and is scored from 0 (worst) to 17 (best), with 14 or less being a cutoff for an abnormal score.[15] The G8 screening tool score was constructed from individual items from the GA and from clinical data.

2.3. Analysis

The primary outcome was an abnormal GA, defined as 2 or more abnormal domains on GA. First, we reported means and standard deviations for the scores on each tool and reported the percent of subjects who had an abnormal domain based on established cutoff scores. The presence of frailty was a secondary outcome of interest. We reported the number and percent with abnormal results for each of the 5 frailty measures. To report associations between patient characteristics and abnormal GA or the presence of frailty, we used Chi-square tests or Fisher’s tests for categorical variables and the Wilcoxon rank sum test for continuous variables. We determined whether an abnormal GA was significantly associated with frailty and whether each the VES-13 and G8 screening scores significantly correlated with the GA or frailty score.

We calculated the sensitivity and specificity for a VES-13 score of 3 or greater and for a G8 score of 14 or less for an abnormal GA and for frailty. We constructed a receiver operating characteristics (ROC) curve and calculated the area under the curve (AUC) to determine the discriminatory ability of the VES-13 score and the G8 score to predict an abnormal GA and to predict frailty. We then tested the comparison of the AUC for the VES-13 and the G8 to determine if there was a difference in the discriminative ability of both scores for abnormal GA or frailty.

A p of <0.05 was considered significant for all analyses. We used Stata IC version 11.2 (Stata Corp, College Station, Texas) for all analyses in this study.

3. Results

Of 134 eligible patients approached for the study, 50 (37.3%) enrolled and completed a GA prior to HCT. Of those who did not enroll, the most common reasons were scheduling difficulties (n=50), not interested in the study (n=30), or too medically unwell to participate in physical function testing (n=4). All 50 enrolled subjects completed the baseline assessment. Two of the 50 patients ultimately did not undergo HCT due to medical illness. The mean age was 65.4 years, with a range of 60 to 73 years. Most participants were white, male, highly educated, married, and employed (Table 2). Most had acute myelogenous leukemia (AML) or myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS).

Table 2.

Characteristics of Older Patients Evaluated for HCT (N=50)

| Characteristic | Category | N (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Age Group | 60 – 64 years | 25 (50) |

| 65 – 69 years | 14 (28) | |

| 70+ years | 11 (22) | |

| Sex | Male | 35 (70) |

| Race | White | 43 (86) |

| Black | 2 (4) | |

| Hispanic | 4 (8) | |

| Other | 1 (2) | |

| Married | 41 (82) | |

| Education | Graduate Degree | 16 (32) |

| College | 23 (46) | |

| High School | 11 (22) | |

| Employed | 41 (82) | |

| BMI | 17 – 25 | 10 (20) |

| 25 – 30 | 23 (46) | |

| Over 30 | 17 (34) | |

| Diagnosis | AML/MDS | 35 (70) |

| CLL | 11 (22) | |

| Other | 4 (8) | |

| Karnofsky Performance | 15 (30) | 100 |

| Status | 90 | 29 (58) |

| 80 | 6 (12) | |

| Remission/Partial Remission at Time of HCT | 23 (46) | |

| Ferritin Level in ng/mL, mean (SD) (2 missing) | 1181 (1213) | |

| 25-Hydroxy Vitamin D in ng/mL (3 missing) | 21.6 (8.8) | |

| BNP Level in pg/mL, mean (SD) (3 missing) | 83.0 (60.9) | |

| CRP Level in mg/dL, mean (SD) (5 missing) | 6.9 (9.0) | |

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; HCT, hematopoietic cell transplantation; BNP, B-type natriuretic peptide, CRP, C-reactive protein

Overall, 33 (66%) had an abnormal GA. Comorbidity, nutrition, and social support were the most commonly abnormal domains (Table 3). Based on the HCT-CI, 12 patients had moderate comorbidity, and 29 patients had severe comorbidity. Eleven patients (22%) were frail at baseline based on having 3 or more abnormal characteristics on the frailty criteria. Forty-two patients (84%) had at least one deficit on the frailty index. Abnormalities on frailty measures were as follows: 31 (62%) had low physical activity, 24 (48%) had low grip strength, 13 (26%) reported weight loss, 11 (22%) had exhaustion, and 6 (12%) had slow gait speeds.

Table 3.

Results of Baseline Geriatric Assessment in 50 Subjects Evaluated for Allogeneic Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation

| Domain | Measure | Mean Score (±SD), Min – Max |

Number (%) with Abnormal Domain |

|---|---|---|---|

| Comorbidity | HCT-CI | 2.8 (±2), 0–7 | 29 (58) |

| Polypharmacy | Medication Number | 7.0 (±4.2), 1–17 | 14 (28) |

| Nutritional Status | MNA | 25 (±3.4), 11.5–30 | 18 (36) |

| Physical Performance | SPPB | 10.9 (±1.5), 6–12 | 9 (18) |

| Functional Status | ADL | 11.8 (±0.4), 10–12 | 8 (16) |

| IADL | 14.8 (±2.5), 9–16 | ||

| 7.9 (±0.4), 6–8 | |||

| Social Support | MOS | 89.9 (±7.5), 60–95 | 27 (54) |

| Psychological Status | HADS-Anxiety | 4.0 (±3.2), 0–13 | 5 (10) |

| HADS-Depression | 2.1 (±1.9), 0–10 | ||

| Cognition | CLOX 1 | 12.1 (±2.8), 2–15 | 8 (16) |

| CLOX 2 | 14.5 (±0.6), 13–15 | ||

| TMTA | 28.9 (±8.6), 15–54 | ||

| TMTB | 88.9 (±48.8), 23–253 |

Abbreviations: HCT-CI, Hematopoietic and Cellular Therapy-Comorbidity Index; MNA, Mini-Nutritional Assessment; SPPB, Short Physical Performance Battery; ADL, Activities of Daily Living; IADL, Instrumental Activities of Daily Living; MOS, Medical Outcomes Survey; HADS, Hospitalized Anxiety and Depression Scale; CLOX, Clock Draw Test; TMTA, Trail Making Test A; TMTB, Trail Making Test B

None of the patient characteristics or laboratory values was associated with an abnormal GA score or the presence of frailty, with the exception of an association of education with frailty (Table 4). Although Karnofsky Performance Status (KPS) was not associated with abnormal GA, all 6 persons who had a KPS of 80 had an abnormal GA. The frailty index score correlated with the GA score (Spearman’s rho = 0.42, p=0.002). None of the baseline patient characteristics were significantly associated with the presence of the frailty syndrome, including KPS.

Table 4.

Bivariate Associations Between Patient Characteristics and Abnormal Geriatric Assessment or the Presence of the Frailty Syndrome

| Characteristic | Category | N (%) with Abnormal GA |

P | N (%) with Frailty |

P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 60–64 | 16 (64.0) | 0.93 | 4 (16.0) | 0.61 |

| 65–69 | 9 (64.3) | 4 (28.6) | |||

| 70+ | 8 (72.7) | 3 (27.3) | |||

| Sex | Male | 21 (60.0) | 0.21 | 7 (20.0) | 0.71 |

| Female | 12 (80.0) | 4 (26.7) | |||

| Race | White | 27 (62.8) | 0.40 | 9 (20.9) | 0.64 |

| Non-White | 6 (85.7) | 2 (28.6) | |||

| Marital Status | Married | 26 (63.4) | 0.70 | 10 (24.4) | 0.66 |

| Not Married | 7 (77.8) | 1 (11.1) | |||

| Education | Graduate | 10 (62.5) | 0.93 | 4 (25.0) | 0.04 |

| College | 16 (69.6) | 2 (8.7) | |||

| High School | 7 (63.6) | 5 (45.5) | |||

| Employment | Employed | 26 (63.4) | 0.70 | 8 (19.5) | 0.39 |

| Retired | 7 (77.8) | 3 (33.3) | |||

| BMI | 17–25 | 7 (70.0) | 0.80 | 1 (10.0) | 0.61 |

| 25–30 | 14 (60.9) | 6 (26.1) | |||

| 30+ | 12 (70.6) | 4 (23.5) | |||

| Diagnosis | AML/MDS | 21 (63.6) | 0.14 | 7 (21.2) | 0.88 |

| CLL | 9 (90.0) | 2 (20.0) | |||

| Other | 3 (42.9) | 2 (28.6) | |||

| KPS | 100 | 8 (53.3) | 0.12 | 3 (20.0) | 0.78 |

| 90 | 19 (65.5) | 6 (20.7) | |||

| 80 | 6 (100.0) | 2 (33.3) | |||

| Remission at time of HCT | Yes | 13 (56.5) | 0.19 | 3 (13.0) | 0.19 |

| No | 20 (74.1) | 8 (29.6) | |||

| Ferritin Level | <400 ng/mL | 10 (71.4) | 0.74 | 2 (14.3) | 1.0 |

| ≥400 ng/mL | 21 (61.8) | 7 (20.6) | |||

| Vitamin D Level | >30 ng/mL | 7 (77.8) | 0.70 | 1 (11.1) | 0.67 |

| ≤30 ng/mL | 24 (63.2) | 8 (21.1) | |||

| BNP | <100 pg/mL | 20 (62.5) | 0.53 | 6 (18.8) | 1.0 |

| ≥100 pg/mL | 11 (73.3) | 3 (20.0) | |||

| CRP | <0.8 mg/dL | 2 (66.7) | 1.0 | 0 (0) | 1.0 |

| ≥0.8 mg/dL | 27 (64.3) | 8 (19.1) |

Abbreviations: KPS, Karnofsky Performance Status; BMI, body mass index; AML, acute myelogenous leukemia; MDS, myelodysplastic syndrome; HCT, hematopoietic cell transplantation; BNP, B-type natriuretic peptide; CRP, C-reactive protein

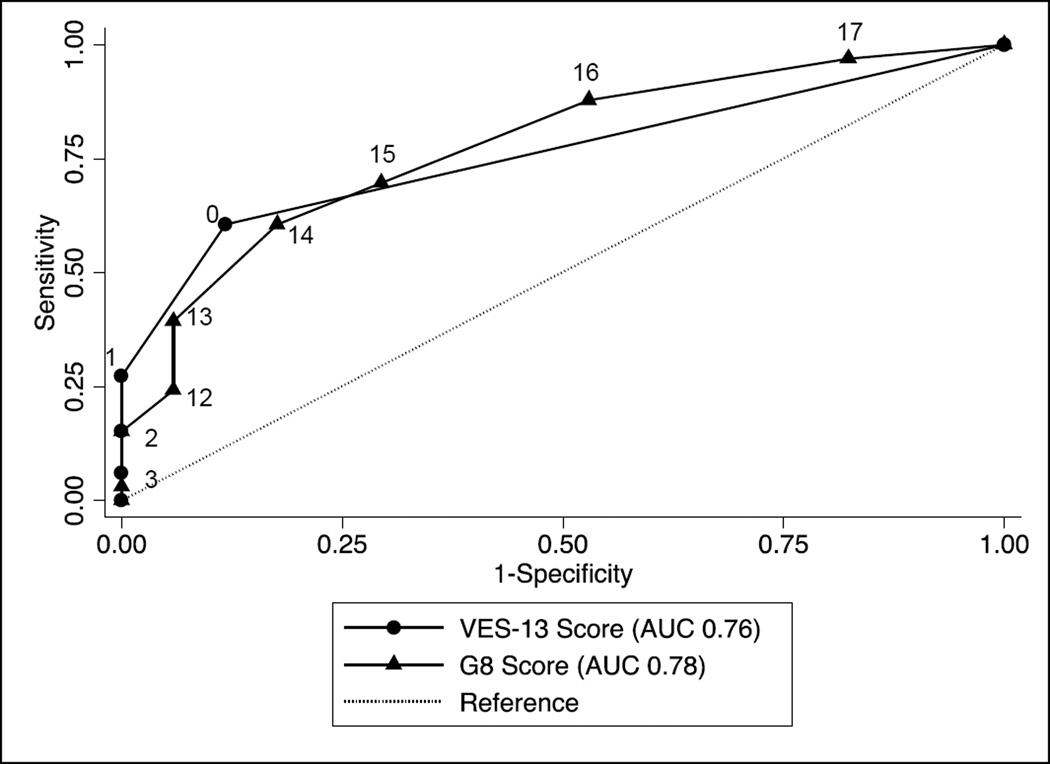

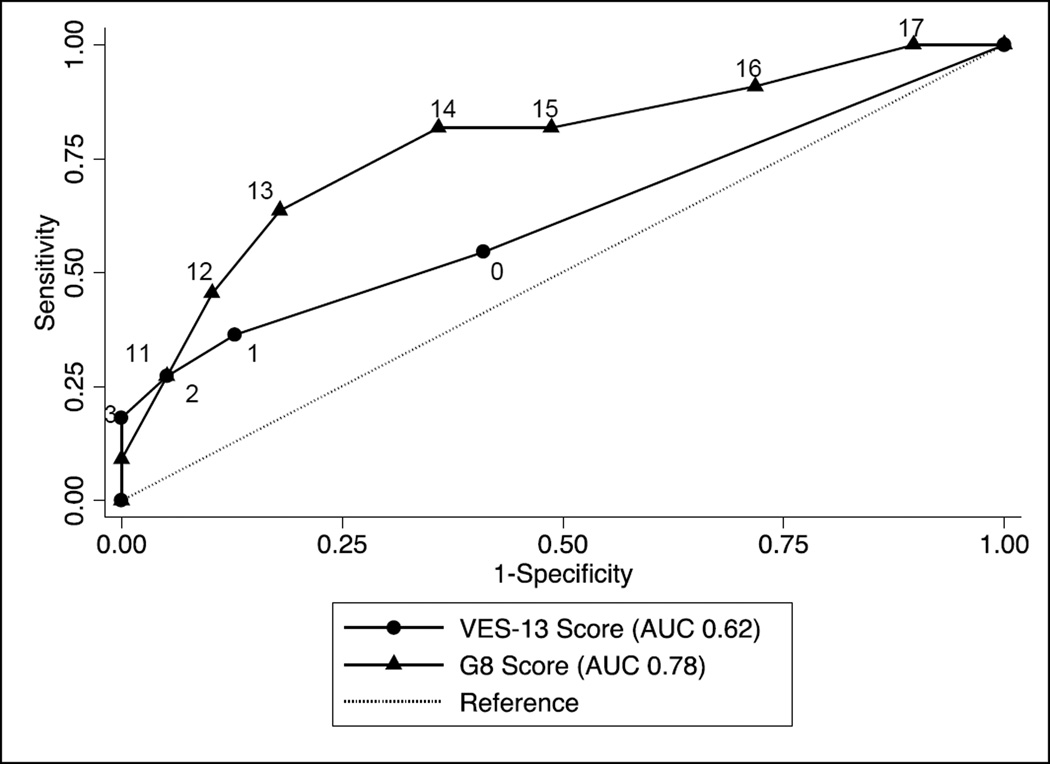

Five subjects had an abnormal VES-13 score of 3 or higher, and 28 subjects had an abnormal G8 score of 14 or lower. Both tools correlated modestly with GA. The G8 score, but not the VES-13 score, correlated with the frailty index score. Both tools discriminated moderately for an abnormal GA and for the presence of frailty. The sensitivity and specificity, negative predictive value, and area under the curve (AUC) for the receiver operating characteristics (ROC) curves for both tools to determine the GA and frailty index are shown in Table 5. The sensitivity and specificity for the VES-13 and the G8 are shown, for the accepted cutoff values as well as alternate values based on the ROC curves. Figure 1 shows the ROC curves for the VES-13 and G8 scores for GA. There was no significant difference between the AUCs for both screening tests (p=0.82). Figure 2 shows the ROC curves for the VES-13 and G8 scores for the outcome of frailty. There was no significant difference in the AUCs for the VES-13 vs. the G8 (p=0.24).

Table 5.

Discriminative Ability of the VES-13 and the G8 to Predict Abnormal Geriatric Assessment (GA) or Frailty

| GA | Frailty | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spearman’s rho (p) |

AUC (95% CI) | Sensitivity; Specificity (%) |

NPV (%) |

Spearman’s rho (p) |

AUC (95% CI) | Sensitivity; Specificity |

NPV | |

| VES-13 | 0.56 (<0.01) | 0.76 (0.65–0.87) | 0.27 (0.06) | 0.62 (0.42–0.82) | ||||

| ≥3 | 15.2; 100 | 37.8 | 27.3; 94.9 | 82.2 | ||||

| ≥1 | 60.6; 88.2 | 53.6 | 54.6; 59.0 | 82.1 | ||||

| G8 | −0.64 (<0.01) | 0.78 (0.65–0.91) | −0.46 (<0.01) | 0.78 (0.61–0.95) | ||||

| ≤14 | 69.7; 70.6 | 54.5 | 81.8; 51.3 | 90.9 | ||||

| ≤13 | 60.6; 82.4 | 51.9 | 81.8; 64.1 | 92.6 | ||||

Figure 1.

Receiver Operating Characteristics Curves for the Vulnerable Elders Survey (VES-13) and the G8 Screening Tool to Discriminate an Abnormal GA

Figure 2.

Receiver Operating Characteristics Curves for the Vulnerable Elders Survey (VES-13) and the G8 Screening Tool to Discriminate the Presence of Frailty

4. Discussion

Our study findings suggest that despite excellent performance status, a substantial proportion of older adults eligible for allogeneic HCT presented with functional deficits and geriatric syndromes as identified by a geriatric assessment. Further, nearly one-fourth met criteria for the frailty syndrome, characterized by weakness, slow gait, weight loss, exhaustion, and low activity. The G8 had a higher sensitivity for abnormal GA and for frailty, and the VES-13 had a higher specificity. The VES-13 and the G8 had a modest NPV to determine which patients were fit enough to bypass a full GA. Both screening tools had a high NPV for the presence of frailty.

Our GA findings are consistent with the study of Muffly et al.,[13] which found a high number of deficits on a GA in 166 patients 50 and older eligible for HCT. They found similar rates of significant comorbidity, nutritional impairment, and frailty syndrome as we found in our study. Patients in their study reported more impairment in ADLs and in IADLs. They had a high enrollment rate of 73% and performed a more abbreviated GA that was feasible to complete in a reasonable time. This contrasts with our study, which had a lower enrollment rate and included several additional GA measures, requiring approximately 45 minutes to complete.

No patient or disease characteristics were associated with an abnormal GA or frailty in our study. The association between education and frailty appears to be spurious, as there is no clear association between increasing educational level and increasing risk of frailty. It is interesting to note that none of these factors, including performance status, were associated with abnormal GA or with frailty, as this would suggest that patient characteristics alone could not help identify those who may have relevant deficits prior to HCT. Muffly’s study also found no association between performance status and any of the individual domains on GA. In contrast, Muffly et al. found that younger patients were likely to have larger deficits on standardized measures when compared to population-based age-associated norms.[13] Our study included a more restricted age range, which did not allow for such comparisons.

Other studies of older patients with cancer have shown high numbers of deficits on geriatric assessment, which have been associated with an increased risk of treatment toxicity, perioperative complications, and mortality.[25, 52] It is important to note that GA could be useful not only to identify those patients at higher risk of such adverse outcomes, but incorporating a GA into routine care could also be helpful to aid treatment decision-making, monitor therapy response in older persons measuring outcomes like function and quality of life, and could be useful as a strategy to provide more individualized supportive care to older persons with cancer.[12] We expected our population to have lower rates of deficits on GA, given that they were younger than elderly patients in other studies and might be highly selected prior to HCT. If abnormal GA and frailty syndrome are associated with adverse outcomes after HCT, these measures could be useful to help in treatment planning for vulnerable older adults. However, the usefulness of GA in HCT may be to provide more detailed information about risks and benefits of treatment,[53] but using GA to guide interventions to treat reversible conditions prior to HCT may be less feasible. Such intervention may not be practical and may even be more harmful in patients who are candidates for allogeneic HCT for whom a delay in therapy could lead to poor outcomes.

Our objective was to find a screening tool that could be used to eliminate the need for a full GA in all HCT patients. It is very possible that older patients undergoing HCT will not be aware of the kinds of subtle vulnerabilities that a GA is designed to detect, and thus might not request such evaluation. A full GA is time-consuming and requires resources of a multidisciplinary team, as well as follow up and treatment for abnormal domains. In contrast to a recent study of 117 older patients with a variety of cancer types,[54] in our study the use of screening tools did not obviate the need for a full GA. As in our study, a recent systematic review also found that the VES-13 had low sensitivity, the G8 had low specificity, and both tools had modest NPV for use as screening for a full GA.[17] However, a study of 937 patients 70 years and older with newly diagnosed cancer, most of whom had solid tumors, found that the G8 had a reasonably high sensitivity and NPV to identify vulnerable patients, and the G8 was predictive of subsequent functional decline and decreased survival.[55] The ability of the G8 to identify vulnerable elders was highly variable according to tumor type in a cross-sectional study of 518 patients in the Elderly Cancer Patient (ELCAPA) study.[56] In addition, in the case of the VES-13 in particular, it is possible that a different cutoff score would be more useful in the HCT population. Thus, a full assessment of the prognostic value of these screening tools will require analysis of outcomes after HCT.

This study has a number of limitations that need to be acknowledged. Our study consisted of a limited sample size, and thus it is possible that we had inadequate power to determine whether screening tools could adequately identify an abnormal GA or frailty. Our enrollment rate was 37%, and we were unable to determine whether patients who were more likely to be impaired were more likely to enroll. Our results may not be generalizable to other centers providing HCT, as our screening and referral procedures and patient population may be different. This study was conducted at a single comprehensive cancer center and thus may not represent the experiences of patients treated at other academic centers or in the community. Further, we employed a GA for use in patients 60 and older, although GA is generally used in older populations; thus the performance of a GA in this younger population is uncertain. Similarly, we applied established cutoffs for abnormal scores for all of the tools employed in the GA as well as the frailty index, but such scores have not been validated to be predictive of long-term outcome in the HCT population. We thus lack a true gold standard against which to compare the VES-13 and G8 in the study.

In conclusion, although older patients are considered highly selected for HCT, the patients in this study had substantial functional and physiologic deficits as well as a high prevalence of frailty. These findings suggest the need for further evaluation of the prognostic value of abnormal GA and the presence of the frailty syndrome in older HCT patients.

Acknowledgments

Role of the Funding Source: This study was supported by the UT MD Anderson Cancer Center Institutional Research Grants program. The funding source had no role in the design, conduct, or reporting of this study.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Disclosures and Conflicts of Interest: The authors have disclosed all financial relationships. The authors feel that there are no conflicts of interest or financial relationships relevant to this manuscript.

Author Contributions:

Study concepts: H.M. Holmes, S. Yennu, S. Giralt, S.G. Mohile

Study design: All Authors

Data acquisition: H.M. Holmes, J.K.A. des Bordes, P. Kebriaei

Quality control of data and algorithms: H.M. Holmes, J.K.A. des Bordes

Data analysis and interpretation: H.M. Holmes, J.K.A. des Bordes, P. Kebriaei, S.G. Mohile

Statistical analysis: H.M. Holmes

Manuscript preparation: H.M. Holmes, J.K.A. des Bordes, S.G. Mohile

Manuscript editing: All Authors

Manuscript review: All Authors

References

- 1.de Lima M, Giralt S. Allogeneic transplantation for the elderly patient with acute myelogenous leukemia or myelodysplastic syndrome. Semin Hematol. 2006;43:107–117. doi: 10.1053/j.seminhematol.2006.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hahn T, McCarthy PL, Jr, Hassebroek A, Bredeson C, Gajewski JL, Hale GA, et al. Significant improvement in survival after allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation during a period of significantly increased use, older recipient age, and use of unrelated donors. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:2437–2449. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.46.6193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shapira MY, Tsirigotis P, Resnick IB, Or R, Abdul-Hai A, Slavin S. Allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation in the elderly. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2007;64:49–63. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2007.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brunner AM, Kim HT, Coughlin E, Alyea EP, 3rd, Armand P, Ballen KK, et al. Outcomes in patients age 70 or older undergoing allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation for hematologic malignancies. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2013;19:1374–1380. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2013.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Alatrash G, de Lima M, Hamerschlak N, Pelosini M, Wang X, Xiao L, et al. Myeloablative reduced-toxicity i.v. busulfan-fludarabine and allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplant for patients with acute myeloid leukemia or myelodysplastic syndrome in the sixth through eighth decades of life. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2011;17:1490–1496. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2011.02.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lim Z, Brand R, Martino R, van Biezen A, Finke J, Bacigalupo A, et al. Allogeneic hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation for patients 50 years or older with myelodysplastic syndromes or secondary acute myeloid leukemia. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:405–411. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.21.8073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Artz AS. Comorbidity and beyond: pre-transplant clinical assessment. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2005;36:473–474. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1705042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Artz AS, Pollyea DA, Kocherginsky M, Stock W, Rich E, Odenike O, et al. Performance status and comorbidity predict transplant-related mortality after allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2006;12:954–964. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2006.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sorror ML, Sandmaier BM, Storer BE, Maris MB, Baron F, Maloney DG, et al. Comorbidity and disease status based risk stratification of outcomes among patients with acute myeloid leukemia or myelodysplasia receiving allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:4246–4254. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.09.7865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Extermann M, Hurria A. Comprehensive geriatric assessment for older patients with cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:1824–1831. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.10.6559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hurria A, Cirrincione CT, Muss HB, Kornblith AB, Barry W, Artz AS, et al. Implementing a geriatric assessment in cooperative group clinical cancer trials: CALGB 360401. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:1290–1296. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.30.6985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dale W, Mohile SG, Eldadah BA, Trimble EL, Schilsky RL, Cohen HJ, et al. Biological, clinical, and psychosocial correlates at the interface of cancer and aging research. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2012;104:581–589. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djs145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Muffly LS, Boulukos M, Swanson K, Kocherginsky M, Cerro PD, Schroeder L, et al. Pilot study of comprehensive geriatric assessment (CGA) in allogeneic transplant: CGA captures a high prevalence of vulnerabilities in older transplant recipients. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2013;19:429–434. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2012.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Saliba D, Elliott M, Rubenstein LZ, Solomon DH, Young RT, Kamberg CJ, et al. The Vulnerable Elders Survey: a tool for identifying vulnerable older people in the community. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2001;49:1691–1699. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2001.49281.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bellera CA, Rainfray M, Mathoulin-Pelissier S, Mertens C, Delva F, Fonck M, et al. Screening older cancer patients: first evaluation of the G-8 geriatric screening tool. Ann Oncol. 23:2166–2172. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdr587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Soubeyran PL, Bellera CA, Gregoire F. Validation fo a screening test for elderly patients in oncology. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26 Abstract 20568. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hamaker ME, Jonker JM, de Rooij SE, Vos AG, Smorenburg CH, van Munster BC. Frailty screening methods for predicting outcome of a comprehensive geriatric assessment in elderly patients with cancer: a systematic review. Lancet Oncol. 2012;13:e437–e444. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(12)70259-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mohile SG, Magnuson A. Comprehensive geriatric assessment in oncology. Interdisciplinary topics in gerontology. 2013;38:85–103. doi: 10.1159/000343608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Klepin HD, Geiger AM, Tooze JA, Kritchevsky SB, Williamson JD, Ellis LR, et al. The feasibility of inpatient geriatric assessment for older adults receiving induction chemotherapy for acute myelogenous leukemia. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2011;59:1837–1846. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2011.03614.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rodin MB, Mohile SG. A practical approach to geriatric assessment in oncology. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:1936–1944. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.10.2954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jacobs SR, Small BJ, Booth-Jones M, Jacobsen PB, Fields KK. Changes in cognitive functioning in the year after hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Cancer. 2007;110:1560–1567. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Basinski JR, Alfano CM, Katon WJ, Syrjala KL, Fann JR. Impact of delirium on distress, health-related quality of life, and cognition 6 months and 1 year after hematopoietic cell transplant. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2010;16:824–831. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2010.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Syrjala KL, Artherholt SB, Kurland BF, Langer SL, Roth-Roemer S, Elrod JB, et al. Prospective neurocognitive function over 5 years after allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation for cancer survivors compared with matched controls at 5 years. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:2397–2404. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.33.9119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Royall DR, Cordes JA, Polk M. CLOX: an executive clock drawing task. Journal of neurology, neurosurgery, and psychiatry. 1998;64:588–594. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.64.5.588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Puts MT, Hardt J, Monette J, Girre V, Springall E, Alibhai SM. Use of geriatric assessment for older adults in the oncology setting: a systematic review. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2012;104:1133–1163. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djs285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sorror ML, Storer BE, Maloney DG, Sandmaier BM, Martin PJ, Storb R. Outcomes after allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation with nonmyeloablative or myeloablative conditioning regimens for treatment of lymphoma and chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood. 2008;111:446–452. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-07-098483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hashmi S, Oliva JL, Liesveld JL, Phillips GL, 2nd, Milner L, Becker MW. The hematopoietic cell transplantation specific comorbidity index and survival after extracorporeal photopheresis, pentostatin, and reduced dose total body irradiation conditioning prior to allogeneic stem cell transplantation. Leuk Res. 2013;37:1052–1056. doi: 10.1016/j.leukres.2013.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Steinman MA. Polypharmacy and the balance of medication benefits and risks. The Am J Geriatr Pharmacother. 2007;5:314–316. doi: 10.1016/j.amjopharm.2007.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Steinman MA, Rosenthal GE, Landefeld CS, Bertenthal D, Sen S, Kaboli PJ. Conflicts and concordance between measures of medication prescribing quality. Med Care. 2007;45:95–99. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000241111.11991.62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vellas B, Guigoz Y, Garry PJ, Nourhashemi F, Bennahum D, Lauque S, et al. The Mini Nutritional Assessment (MNA) and its use in grading the nutritional state of elderly patients. Nutrition. 1999;15:116–122. doi: 10.1016/s0899-9007(98)00171-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Read JA, Crockett N, Volker DH, MacLennan P, Choy ST, Beale P, et al. Nutritional assessment in cancer: comparing the Mini-Nutritional Assessment (MNA) with the scored Patient-Generated Subjective Global Assessment (PGSGA) Nutrition and cancer. 2005;53:51–56. doi: 10.1207/s15327914nc5301_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Guralnik JM, Simonsick EM, Ferrucci L, Glynn RJ, Berkman LF, Blazer DG, et al. A short physical performance battery assessing lower extremity function: association with self-reported disability and prediction of mortality and nursing home admission. Journal of gerontology. 1994;49:M85–M94. doi: 10.1093/geronj/49.2.m85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Penninx BW, Ferrucci L, Leveille SG, Rantanen T, Pahor M, Guralnik JM. Lower extremity performance in nondisabled older persons as a predictor of subsequent hospitalization. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2000;55:M691–M697. doi: 10.1093/gerona/55.11.m691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Katz S, Ford AB, Moskowitz RW, Jackson BA, Jaffe MW. Studies of Illness in the Aged. The Index of Adl: A Standardized Measure of Biological and Psychosocial Function. JAMA. 1963;185:914–919. doi: 10.1001/jama.1963.03060120024016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Repetto L, Fratino L, Audisio RA, Venturino A, Gianni W, Vercelli M, et al. Comprehensive geriatric assessment adds information to Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status in elderly cancer patients: an Italian Group for Geriatric Oncology Study. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20:494–502. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.20.2.494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Serraino D, Fratino L, Zagonel V Group GIS. Prevalence of functional disability among elderly patients with cancer. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2001;39:269–273. doi: 10.1016/s1040-8428(00)00130-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ramchandran KJ, Shega JW, Von Roenn J, Schumacher M, Szmuilowicz E, Rademaker A, et al. A predictive model to identify hospitalized cancer patients at risk for 30-day mortality based on admission criteria via the electronic medical record. Cancer. 2013;119:2074–2080. doi: 10.1002/cncr.27974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Aparicio T, Jouve JL, Teillet L, Gargot D, Subtil F, Le Brun-Ly V, et al. Geriatric factors predict chemotherapy feasibility: ancillary results of FFCD 2001–02 phase III study in first-line chemotherapy for metastatic colorectal cancer in elderly patients. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:1464–1470. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.42.9894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lawton MP. The functional assessment of elderly people. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1971;19:465–481. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1971.tb01206.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sherbourne CD, Stewart AL. The MOS social support survey. Soc Sci Med. 1991;32:705–714. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(91)90150-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sherbourne CD, Meredith LS, Rogers W, Ware JE., Jr Social support and stressful life events: age differences in their effects on health-related quality of life among the chronically ill. Qual Life Res. 1992;1:235–246. doi: 10.1007/BF00435632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Beattie S, Lebel S, Tay J. The influence of social support on hematopoietic stem cell transplantation survival: a systematic review of literature. PLoS One. 2013;8:e61586. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0061586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zigmond AS, Snaith RP. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta psychiatrica Scandinavica. 1983;67:361–370. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1983.tb09716.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Prieto JM, Atala J, Blanch J, Carreras E, Rovira M, Cirera E, et al. Role of depression as a predictor of mortality among cancer patients after stem-cell transplantation. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:6063–6071. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.05.751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Prieto JM, Saez R, Carreras E, Atala J, Sierra J, Rovira M, et al. Physical and psychosocial functioning of 117 survivors of bone marrow transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant. 1996;17:1133–1142. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gaudino EA, Geisler MW, Squires NK. Construct validity in the Trail Making Test: what makes Part B harder? Journal of clinical and experimental neuropsychology. 1995;17:529–535. doi: 10.1080/01688639508405143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Fried LP, Tangen CM, Walston J, Newman AB, Hirsch C, Gottdiener J, et al. Frailty in older adults: evidence for a phenotype. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2001;56:M146–M156. doi: 10.1093/gerona/56.3.m146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tan KY, Kawamura YJ, Tokomitsu A, Tang T. Assessment for frailty is useful for predicting morbidity in elderly patients undergoing colorectal cancer resection whose comorbidities are already optimized. Am J Surg. 2012;204:139–143. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2011.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Song X, Mitnitski A, Rockwood K. Prevalence and 10-year outcomes of frailty in older adults in relation to deficit accumulation. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2010;58:681–687. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2010.02764.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Aaldriks AA, Giltay EJ, le Cessie S, van der Geest LG, Portielje JE, Tanis BC, et al. Prognostic value of geriatric assessment in older patients with advanced breast cancer receiving chemotherapy. Breast. 2013 doi: 10.1016/j.breast.2013.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Min LC, Elliott MN, Wenger NS, Saliba D. Higher vulnerable elders survey scores predict death and functional decline in vulnerable older people. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2006;54:507–511. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.00615.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Puts MT, Monette J, Girre V, Pepe C, Monette M, Assouline S, et al. Are frailty markers useful for predicting treatment toxicity and mortality in older newly diagnosed cancer patients? Results from a prospective pilot study. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2011;78:138–149. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2010.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wildes TM, Stirewalt DL, Medeiros B, Hurria A. Hematopoietic stem cell transplantation for hematologic malignancies in older adults: geriatric principles in the transplant clinic. Journal of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network : JNCCN. 2014;12:128–136. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2014.0010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Castagneto B, Di Pietrantonj C, Stevani I, Anfossi A, Arzese M, Giorcelli L, et al. The importance of negative predictive value (NPV) of vulnerable elderly survey (VES 13) as a prescreening test in older patients with cancer. Med Oncol. 2013;30:708. doi: 10.1007/s12032-013-0708-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kenis C, Decoster L, Van Puyvelde K, De Greve J, Conings G, Milisen K, et al. Performance of two geriatric screening tools in older patients with cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:19–26. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.51.1345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Liuu E, Canoui-Poitrine F, Tournigand C, Laurent M, Caillet P, Le Thuaut A, et al. Accuracy of the G-8 geriatric-oncology screeningtool for identifying vulnerable elderly patients with cancer according to tumour site: The ELCAPA-02 study. J Geriatr Oncol. 2014;5:11–19. doi: 10.1016/j.jgo.2013.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]