Abstract

Objectives:

To examine patients’ perspectives regarding long-term vitamin K antagonist (VKA) therapy and the potential transition to new oral anticoagulants (NOACs) such as dabigatran and rivaroxaban, and to determine if factors such as residential location affect these opinions.

Design, setting and participants:

Patients on VKA therapy for at least 12 weeks completed a questionnaire specifically designed for the study. They were recruited while attending point-of-care international normalized ratio (INR) testing at six South Australian general practice clinics during the period July–September 2013.

Main outcome measures:

Opinions of current VKA therapy, level of awareness of NOACs, and ratings of potential benefits and deterrents of transition to NOACs were sought.

Results:

Data from 290 participants were available for analysis (response rate 95.4%). The majority of the sample (79.5%, 229/288) were either satisfied or very satisfied with current VKA therapy. The mean score for the potential benefits of transition to NOACs was 7.6 (±4.2) out of a possible 20, which was significantly lower than the mean score 10.9 (±4.5) for the perceived deterrents to transition (p < 0.001). Rural patients (82.0%, 82/100) were significantly more likely (p = 0.001) to have not heard of NOACs than metropolitan patients (50.3%, 95/189) and also perceived significant less benefits in a transition to NOACs (p = 0.001).

Conclusion:

When considering potential transition from VKAs to NOACs it is important for prescribers to consider that some patients, in particular those from a rural location, may not perceive a significant benefit in transitioning or may have particular concerns in this area.

Keywords: Warfarin, oral anticoagulants, vitamin K antagonists, INR, patient preferences

Introduction

Vitamin K antagonists (VKAs) have been for many years the only class of oral medications available for long-term anticoagulation therapy. Of these, warfarin is the most common. To review, it limits the function of the vitamin K dependent clotting factors and protein C and protein S [Tadros and Shakib, 2010]. Notwithstanding their popularity, several factors make VKAs far from ideal. A key issue is their very narrow therapeutic windows, with research demonstrating the difficulty of maintaining plasma concentrations within desired targets, even in structured clinical trials [Lopes et al. 2010]. This difficulty is thought to be in part due to a range of genetic polymorphisms that alter the pharmacokinetics of VKAs in many individuals [Ageno et al. 2012; Weitz and Gross, 2012]. In addition, VKAs are known to interact with more than 250 other medications, as well as alcohol and a variety of foods [Tadros and Shakib, 2010], which may also result in less than desirable plasma concentrations [Corbi et al. 2011].

For these reasons it is necessary for patients to have frequent tests to check their standardized prothrombin time, expressed as an international normalized ratio (INR), and adjust dosages if required. Although this process has been simplified somewhat in recent years by the introduction of point-of-care INR testing, it is still thought to represent such a burden that it is believed to contribute significantly to the underuse of VKAs in situations where they are otherwise clinically indicated [Connolly et al. 2009; Johnson, 2013; Lopes et al. 2010; Pugh et al. 2011]. This situation has been a significant driver in the development of new oral anticoagulants (NOACs) that may require less monitoring and have less impact on the lifestyle of patients.

Instead of affecting multiple aspects of the coagulation cascade, these NOACs target single clotting enzymes, most commonly acting as inhibitors of either thrombin (e.g. dabigatran) or factor Xa (e.g. rivaroxaban and apixiban) [Camm, 2009; Weitz and Gross, 2012]. Multiple phase III trials have shown these agents to be noninferior to VKAs in terms of reduction in stroke and systemic embolism and also adverse reactions, with some studies even finding areas of significant superiority [Granger et al. 2011; Patel et al. 2011].

In such trials NOACs have been prescribed at fixed doses without regular laboratory monitoring of coagulation parameters, and without an increase in adverse outcomes [Connolly et al. 2009; Granger et al. 2011; Lopes et al. 2010; Patel et al. 2011]. However, NOACs have their own drawbacks. For example, currently there are no available agents that reverse their anticoagulant effect (cf. low-dose phytonadione in the case of VKAs), and the standard methods for assessing coagulation time, such as INR, are of limited use [Ageno et al. 2012; Becattini et al. 2012; Weitz and Gross, 2012].

The introduction of NOACs for long-term anticoagulation has led to some uncertainty regarding their incorporation into clinical practice, both for patients currently maintained on VKAs and those who are commencing therapy. Some authors have suggested that if there are no contraindications, patients currently on VKAs should be transitioned to NOACs routinely given the perceived increased safety and reduction in patient burden. However, others have argued that it is unnecessary for those currently achieving stable anticoagulation with VKAs to make such a change [Becattini et al. 2012; Garcia et al. 2010; Perez et al. 2013; Weitz and Gross, 2012].

Indeed, while there is a commonly accepted perception of burden associated with VKA therapy, there is a counter argument that in reality this burden may be less significant than often described [Smith et al. 2010]. Two such illustrations are from the Birmingham Atrial Fibrillation Treatment of the Aged (BAFTA) and Randomized Evaluation of Long-term anticoagulant therapY (RE-LY) trials [Lancaster et al. 1991; Monz et al. 2013]. The BAFTA trial compared long-term aspirin with warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation. At the end of 2 years there was no significant difference in global quality of life between the two treatment groups, and only 11% of patients agreed that taking warfarin restricted their lifestyle [Lancaster et al. 1991]. Similarly, in the more recent RE-LY trial which compared long-term therapy with warfarin and dabigatran, after 12 months there were no significant group differences in either health-related or global quality of life [Monz et al. 2013].

To date, the above debate regarding the potential benefits of NOACs has not been informed by the perspectives of patients. Similarly, patient perceptions of current VKA therapy have not been well documented. These shortcomings have implications for clinical practice in that evidence-based decisions by prescribers could be compromised by the beliefs and preferences of patients. Therefore, the aim of the current study was to seek input from patients regarding long-term warfarin therapy and the potential transition to NOACs. A secondary aim was to determine if factors such as age, sex or residence affect these opinions.

Methods

Subjects and procedure

A convenience sample was recruited at patients’ regular general practice. Six clinics were sampled, of which five were in metropolitan Adelaide and one was in rural South Australia. All of the clinics used point-of-care INR testing. The first two authors regularly attended these clinics during the period July–September 2013. Potential recruits were provided with a letter of introduction and study information details. Exclusion criteria were not having a sufficient level of English to comprehend these forms, significant cognitive impairment, having been on warfarin for less than 12 weeks, or having previously taken a NOAC. Consenting patients either completed the questionnaire at the clinic or in their own time, using a reply paid envelope for its return.

Measures

A questionnaire was specifically designed for the current study (Appendix 1). Along with demographic details such as age and gender, it comprised sections on current therapy and a hypothetical switch from warfarin to a NOAC. First, patients rated the degree to which five common complaints made about warfarin therapy were a problem for them using a five-point Likert scale. As frequently identified in the literature [Corbi et al. 2011; Kneeland and Fang, 2010], these complaints were INR monitoring, frequent medical appointments, dietary restrictions, interactions with other medications, and frequent changes to dose. Responses were coded and summed to provide a total problem score (range 5–25) such that higher scores equated to greater perceived problems. A specific question about patients’ feelings toward frequent INR checks was also included. An overall satisfaction rating with warfarin therapy (five-point scale) completed the section.

The final section comprised three questions. Patients were asked whether they had heard about NOACs and, if so, the primary source of this information. They were also asked to rate the importance on a five-point scale of four potential benefits (e.g. INR monitoring not required, decreased interactions with food) and four potential deterrents (e.g. no regular monitoring, potential side effects) that may influence their switch to NOACs either positively or negatively. Each set of responses were summed, providing a total benefits score and total deterrents score (both 4–20). Higher scores reflected greater perceived benefits and greater perceived deterrents, respectively.

Ethics approval

Approval was granted by the Flinders University Social and Behavioural Research Ethics Committee.

Data analysis

All analyses were conducted using SPSS (version 22). Depending on the nature of the data, unpaired t tests (or paired for the comparison between benefits and deterrents), correlations and χ2 tests were used. Means (±SD) are reported. A p value of less than 0.05 was considered significant. The p values are two tailed if applicable. In the case of the total warfarin problem score, analyses are nonparametric as the variable demonstrated substantial nonnormality. These tests are highlighted in context. Comparisons undertaken comprised potential benefits of the transition to NOACs with potential deterrents (total sample), and sex, age, duration of therapy and residential location effects for satisfaction with, and perceived problems with, current therapy, and potential benefits and deterrents of the transition to NOACs.

Results

After applying the exclusion criteria, 304 potential patients were identified, of whom 14 declined to participate. This resulted in 290 questionnaires being available for analysis (response rate 95·4%). Of these, 11 patients declined to answer at least one item, but their remaining data were included in relevant analyses. The majority of the sample was male (57.9%, 168/290) and living in metropolitan Adelaide (65.5%, 190/290). The mean age of the sample was 74.9 ± 12.1 years (range 25–94 years), while the mean duration of warfarin therapy was 6.1 ± 5.7 years (range 0.25–41 years).

Over three-quarters of the sample (79.5%, 229/288) reported being either ‘satisfied’ or ‘very satisfied’ with their current therapy and only 4.8% (14/288) reported being ‘unsatisfied’ or ‘very unsatisfied’. The median level of perceived problems with warfarin therapy was 5 (out of 25). The individual issues, and the number of patients who considered a problem at any level, are presented in Table 1 for both the total sample and by sex. When asked specifically about frequent INR testing, 38.9% (112/288) commented that they ‘liked the confirmation that the medication is working as desired’. Only 6.9% (20/288) expressed specific dislike of the requirement.

Table 1.

Rank order of potential problems associated with warfarin therapy.

| Men |

Women |

Total sample |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | |

| Potential problems | |||

| Frequent changes to dose | 31 (18.5) | 31 (25.4) | 62 (21.4) |

| Frequency of medical appointments | 34 (20.2) | 23 (18.9) | 57 (19.7) |

| Frequency of INR testing | 24 (14.3) | 21 (17.2) | 45 (15.5) |

| Interactions with other medications | 18 (10.7) | 25 (20.5) | 43 (14.8) |

| Interactions between warfarin and food | 11 (6.5) | 23 (18.9) | 34 (11.7) |

INR, international normalized ratio.

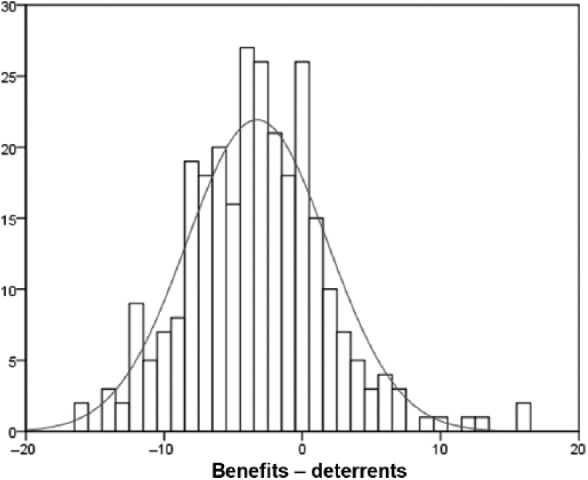

The majority of the sample had not heard about NOACs (61.2%, 177/289). Of those who had, 42/.7% (47/110) had been informed by a healthcare professional with the remainder learning from an informal source such as friends, family or the media. While there was a significant positive correlation between the potential benefits of and deterrents to NOACs (p < 0.001), the mean score for benefits (7.6 ± 4.2) was nevertheless significantly lower than the mean score for deterrents (10.9 ± 4.5) (p < 0.001). The number of patients who ranked each benefit and deterrent as ‘important’ or ‘very important’ are shown in Table 2, again for both the total sample and by sex. Further, participant mean differences between benefits and deterrents are displayed in Figure 1. These differences were normally distributed about the mean of 3.3, with evidence of some individuals strongly advocating either benefits or deterrents, respectively.

Table 2.

Rank order of potential benefits and deterrents associated with the transition to NOACs.

| Men |

Women |

Total sample |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | |

| Benefits | |||

| Fewer alterations to medication dose | 34 (20.4) | 32 (26.7) | 66 (22.9) |

| INR monitoring not required | 37 (22.2) | 26 (21.5) | 63 (21.9) |

| Fewer interactions with other medications | 21 (12.6) | 20 (16.7) | 41 (14.3) |

| Decreased interactions with food | 16 (9.6) | 19 (15.7) | 35 (12.2) |

| Deterrents | |||

| Anticoagulation unable to be reversed | 66 (40.0) | 54 (44.7) | 120 (41.9) |

| Potential side effects | 47 (28.7) | 61 (51.2) | 108 (38.2) |

| No regular INR monitoring required | 46 (28.0) | 53 (43.8) | 99 (34.7) |

| Uncertainty about a new medication | 39 (23.6) | 47 (38.8) | 86 (30.1) |

INR, international normalized ratio; NOAC, new oral anticoagulant.

Figure 1.

Frequency distribution of mean differences between perceived benefits and deterrents of new oral anticoagulants.

Gender

The mean overall satisfaction with therapy was not significantly different between men and women (p = 0.635). However, women reported a greater level of perceived problems with warfarin therapy than men (p = 0.046, Mann–Whitney U test). Regarding the switch to NOACs, potential benefits were rated equivalently (p = 0.286) by men and women while potential deterrents were rated significantly higher by women (p < 0.001).

Age

Increasing age was correlated with greater satisfaction with warfarin therapy (p = 0.009) and fewer perceived problems with warfarin (p < 0.001, Spearman’s rho). Both perceived potential benefits to transition to NOACs, and deterrents, declined with increasing age (p < 0.001, respectively).

Duration of warfarin therapy

Increasing length of time on warfarin therapy was correlated with lower satisfaction (p = 0.028) but shared no relationships with perceived problems of warfarin (p = 0.424, Spearman’s rho) or either perceived benefits (p = 0.222) or perceived deterrents (p = 0.878) of NOACs.

Residential location

The rural cohort reported a higher satisfaction with current warfarin therapy, with 85% (85/100) reporting being very satisfied compared with only 46.8% (88/188) of those from the metropolitan area (p < 0.001). Further, the warfarin problem score for the rural cohort was significantly lower than that for the metropolitan cohort (p = 0.002, Mann–Whitney U test).

Rural patients (82.0%, 82/100) were significantly more likely (p = 0.001) to have not heard of NOACs than metropolitan patients (50.3 %, 95/189). They also saw fewer benefits in a transition to NOACs (p = 0.001) than metropolitan patients, but were not significantly different to metropolitan patients in their perception of potential deterrents (p = 0.060).

Discussion

This study suggests that the commonly held belief that patients perceive many difficulties associated with VKA therapy may not be completely accurate. Almost 80% stated that they were satisfied or very satisfied with their current therapy, with less than 5% reporting any dissatisfaction. Of note is that these findings are consistent with two large randomized controlled trials which found no significant differences when comparing health-related quality of life of patients on VKAs compared with aspirin [Lancaster et al. 1991] and dabigatran [Monz et al. 2013]. Similarly, Das and colleagues assessed physical or mental aspects of quality of life of a cohort prior to starting VKA therapy and 6 months later, also finding no significant difference between time points [Das et al. 2009].

Patient attitudes toward the specific need for regular INR monitoring as a component of VKA therapy was also of interest. Again, although this has been described as burdensome [Corbi et al. 2011; Das et al. 2009], only 6.9% of the current patients expressed a dislike for this activity. The majority of the sample actually reported approval of the confirmation that their medication was having the desired effect. In addition, a greater proportion of participants ranked removal of INR monitoring as a significant deterrent to transition to NOACs rather than as a perceived benefit (21.9% compared with 34.7%). This variation from the common perception of INR testing as a burden may in part be due to the assumption that if monitoring were not required patients would have less frequent visits to health professionals. However, given the likelihood of medical comorbidities in the demographic commonly prescribed VKAs, frequency of visits to medical professionals may not actually be determined by the need for INR monitoring but rather by other factors such as repeat prescriptions or management of other chronic conditions. Further support for this assertion is that only 2% of patients reported frequency of medical appointments as a significant problem associated with VKA therapy. Overall, this may suggest that patients who transition from VKA to NOACs could experience some anxiety regarding the reassurance associated with INR monitoring.

Previous research has suggested that VKAs are often under prescribed despite clinical indications, which is attributed at least in part to physician apprehension regarding the perceived burden for patients [Johnson, 2013; Kneeland and Fang, 2010; Tadros and Shakib, 2010]. Findings from our study may therefore impact on clinical practice as they suggest that such apprehension in prescribing VKAs when long-term anticoagulation is medically indicated is ill founded. In addition, if the patient complaints associated with VKA therapy are not as significant as commonly stated, this alone may not be sufficient justification to transition patients who are stable to NOACs.

While numerous potential benefits of NOACs have been described in the literature, the authors are unaware of any publications that specifically describe the perspective of patients regarding potential benefits and deterrents. Overall, our sample provided a significantly lower mean score for the potential deterrents to NOACs than for potential benefits, suggesting our patients are yet to perceive a net benefit of NOACs. More specifically, a factor that a large number of patients found significant regarding NOACs was the lack of reversibility. This suggests that if in the future an agent were available that could reverse the effect of NOACs, patients may perceive these agents as a more attractive alternative to VKAs.

Regarding patient knowledge of NOACS, it is worth noting that only 17% of patients had received information from a healthcare professional. The remainder had either not heard of NOACs at all or had heard about them from an informal source such as friends or family, with the associated probability of the information being incomplete or incorrect. Therefore, if and when transition to NOACs is embraced by the majority of potential candidates, significant education will be required. Such education may be informed by our findings concerning demographic indicators of preference. Female patients rated the potential deterrents to transition as significantly greater compared with male patients, while there was no difference between sexes in the ratings given for potential benefits. Interestingly, women also identified more problems with current therapy than men. While superficially confusing, these results perhaps reinforce the long-held understanding that women are more proactive and discerning about healthcare information compared with men [Courtenay, 2000; Weisman and Teitelbaum, 1989]. With respect to residence, patients in rural locations ranked the potential benefits of transition as significantly lower than those from metropolitan areas, although there was no difference in potential deterrents. This may appear an unexpected finding given that they probably have to travel further for INR testing than their metropolitan counterparts, but it is likely that their warfarin management is incorporated into planned general practitioner visits for other health issues.

A limitation of this study is that participants had already elected to be on warfarin, potentially instead of NOACS, which could introduce bias into the responses they provided. However, the possibility of this occurring is somewhat lowered as the majority of data were collected prior to NOACs being listed on the Australian pharmaceutical benefits scheme. The fact that many participants did not have any prior knowledge of NOACs may also have affected their scoring of potential benefits and deterrents of transitioning to NOACs. Another limitation is that in creating a questionnaire specific to this topic, nonvalidated questions were used.

In summary, this study suggests that a majority of patients who are already on long-term warfarin therapy are satisfied with their current therapy and do not find regular INR monitoring to be as much of an inconvenience as is often described. If patient transition to NOACs is deemed appropriate and beneficial it is important for prescribers to have an understanding of the potential concerns patients may express in order to appreciate the interindividual variation likely to be encountered. This in turn will enable adequate counselling and targeted education through a period of significant change to an entrenched therapeutic modality.

Appendix 1.

Questionnaire that was specifically designed for the current study

Footnotes

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflict of interest statement: The authors declare no conflict of interest in preparing this article.

Contributor Information

Elizabeth S. Gebler-Hughes, School of Medicine, Flinders University, Adelaide, SA, Australia

Linda Kemp, School of Medicine, Flinders University, Adelaide, SA, Australia.

Malcolm J. Bond, School of Medicine, Health Sciences Building, Flinders University, GPO Box 2100, Adelaide, SA 5001, Australia

References

- Ageno W., Gallus A., Wittkowsky A., Crowther M., Hylek E., Palareti G. (2012) Oral anticoagulant therapy: antithrombotic therapy and prevention of thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines. Chest 141(Suppl. 2): e44S–e88S. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becattini C., Vedovati M., Agnelli G. (2012) Old and new oral anticoagulants for venous thromboembolism and atrial fibrillation: a review of the literature. Thromb Res 129: 392–400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camm A. (2009) The RE-LY study: Randomized Evaluation of Long-term anticoagulant therapY: dabigatran vs. warfarin. Eur Heart J 30: 2554–2555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connolly S., Ezekowitz M., Yusuf S., Eikelboom J., Oldgren J., Parekh A., et al. (2009) Dabigatran versus warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med 361: 1139–1151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corbi I., Dantas R., Pelegrino F., Carvalh A. (2011) Health related quality of life of patients undergoing oral anticoagulation therapy. Rev Lat Am Enfermagem 19: 865–873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Courtenay W. (2000) Constructions of masculinity and their influence on men’s well-being: a theory of gender and health. Soc Sci Med 50: 1385–1401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Das A., Ahmed A., Corrado O., West R. (2009) Quality of life of elderly people on warfarin for atrial fibrillation. Age Aging 38: 751–754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia D., Libby E., Crowther M. (2010) The new oral anticoagulants. Blood 115: 15–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Granger C., Alexander J., McMurray J., Lopes R., Hylek E., Hanna M., et al. (2011) Apixaban versus warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med 365: 981–992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson M. (2013) Transitions of care in patients receiving oral anticoagulants: general principles, procedures, and impact of new oral anticoagulants. J Cardiovas Nurs 28: 54–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kneeland P., Fang M. (2010) Current issues in patient adherence and persistence: focus on anticoagulants for the treatment and prevention of thromboembolism. Patient Prefer Adherence 4: 51–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lancaster T., Singer D., Sheehan M., Oertel L., Maraventano S., Hughes R., et al. (1991) The impact of long-term warfarin therapy on quality of life. Evidence from a randomized trial. Arch Intern Med 151: 1944–1949. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopes R., Alexander J., Al-Khatib S., Ansell J., Diaz R., Easton J., et al. (2010) Apixaban for reduction in stroke and other thromboembolic events in atrial fibrillation (ARISTOTLE) trial: design and rationale. Am Heart J 159: 331–339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monz B., Connolly S., Korhonen M., Noack H., Pooley J. (2013) Assessing the impact of dabigatran and warfarin on health-related quality of life: results from an RE-LY sub-study. Int J Cardiol 168: 2540–2547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel M., Mahaffey K., Garg J., Pan G., Singer D., Hacke E., et al. (2011) Rivaroxaban versus warfarin in nonvalvular atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med 365: 883–891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez A., Eraso L., Merli G. (2013) Implications of new anticoagulants in primary practice. Int J Clin Pract 67: 139–156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pugh D., Pugh J., Mead G. (2011) Attitudes of physicians regarding anticoagulation for atrial fibrillation: a systematic review. Age Ageing 40: 675–683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith M., Christensen N., Wang S., Strohecker J., Day J., Weiss J., et al. (2010) Warfarin knowledge in patients with atrial fibrillation: Implications for safety, efficacy, and education strategies. Cardiology 116: 61–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tadros R., Shakib S. (2010) Warfarin – indications, risks and drug interactions. Aust Fam Physician 39: 476–479. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weisman C., Teitelbaum M. (1989) Women and health care communication. Patient Educ Couns 13: 183–199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weitz J., Gross P. (2012) New oral anticoagulants: which one should my patient use? Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program 2012: 536–540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]