Abstract

Telomeres are nucleoprotein structures present at the ends of eukaryotic chromosomes that play a central role in guarding the integrity of the genome by protecting chromosome ends from degradation and fusion. Length regulation is central to telomere function. To broaden our knowledge about the mechanisms that control telomere length, we have carried out a systematic examination of ≈4,800 haploid deletion mutants of Saccharomyces cerevisiae for telomere-length alterations. By using this screen, we have identified >150 candidate genes not previously known to affect telomere length. In two-thirds of the identified mutants, short telomeres were observed; whereas in one-third, telomeres were lengthened. The genes identified are very diverse in their functions, but certain categories, including DNA and RNA metabolism, chromatin modification, and vacuolar traffic, are overrepresented. Our results greatly enlarge the number of known genes that affect telomere metabolism and will provide insights into how telomere function is linked to many other cellular processes.

In most eukaryotes, telomeres consist of tandem arrays of a short G-rich repeat that protects chromosome ends from being recognized as double-strand breaks (1). Telomeres are prone to shortening at each replication event because of an inherent inability of the replication machinery to fully replicate them (2, 3). This sequence loss is normally prevented by the action of the ribonucleoprotein enzyme telomerase, which reverse-transcribes telomeric repeats onto telomeric ends (4). Addition of new sequences by telomerase is typically tightly regulated, resulting in the telomeres of many organisms being kept within particular size ranges.

Most human somatic cells do not express telomerase, and their telomeres shorten with each cell division. This shortening can eventually trigger replicative senescence by means of the activation of growth inhibition pathways dependent on Rb and p53 (5). Bypass of replicative senescence produces further telomere erosion, telomere–telomere fusions, and the eventual cell death known as crisis (6–8). Exogenous expression of the catalytic subunit of telomerase prevents both replicative senescence and crisis (9). More than 90% of human cancers display cellular immortality because of the expression of telomerase activity and the resulting stabilization of telomere lengths (10, 11). Determining the mechanisms by which telomeres and telomerase are regulated could lead to better understanding of both carcinogenesis and aging.

Much of our basic knowledge of telomere biology has come from studies of the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Telomeres in this organism are composed of tracts of heterogeneous TG1–3 sequences that normally total a few hundred base pairs in length. A large number of proteins are already known to be involved in various aspects of yeast telomere function. In addition to telomerase, these include dedicated telomere binding proteins (1, 12, 13), the Ku (Yku70/Yku80) and MRX (Mre11/Rad50/Xrs2) DNA repair complexes (reviewed in ref. 14), and certain checkpoint (15) and replication proteins (16). Genes for most of these proteins alter telomere length when mutated. Average telomere length can therefore be a very sensitive sensor of telomere function. Many genes related to telomere function in yeast have been found to have similar roles in other organisms, including humans. It is therefore reasonable to predict that identifying genes that alter yeast telomere will lead to useful insights into human telomere biology. In this work, we have used a collection of deletion mutants of all nonessential genes to systematically search for genes affecting telomere length. We report >150 genes that were not previously known to alter telomere length. These genes affect several different cell processes, including DNA and RNA metabolism, chromatin modification, and vacuolar traffic.

Materials and Methods

Strains. A collection of 4,852 haploid Saccharomyces strains (17) was used in which each strain has a single ORF replaced with the KanMX4 module, which confers G418 resistance. These strains are in the BY4741 background (MATa his3Δ leu2Δ met15Δ ura3Δ). The isogenic strain BY4742 (MATα his3Δ leu2Δ lys2Δ ura3Δ) was used for genetic analysis.

Telomere Length Measurement. DNA was prepared from cells taken directly from yeast extract/peptone/dextrose plates. In most cases, cells had been freshly stamped from thawed microtiter plate stocks. DNA from each strain was digested overnight with XhoI and run on agarose gels for 16–20 h at 1.4 V/cm. Southern blotting was performed by using Hybond-N+ membrane (Amersham Biosciences), and probed with radiolabeled telomeric probe 26G (5′-TGTGGGTGTGGTGTGTGGGTGTGGTG-3′) labeled with T4 polynucleotide kinase. All hybridizations were done in 200 mM Na2HPO4 and 2% SDS (18).

For the Southern blots shown, internal control fragments of sizes 1,865 and 644 bp, containing S. cerevisiae telomeric repeats were generated by BsmAI and TaqI digests, respectively, of the plasmid pYt103 (19). We added ≈10 ng of each digested DNA to each lane together with the XhoI digested genomic DNA. For better resolution of size differences, 25-cm-long gels were run at 1.4 V/cm for 600 min and an additional 600 min at 2 V/cm. The average telomeric length for each lane was estimated by plotting the peak of signal intensity of the shortest telomere band (Y′ telomeres) against the position of the added internal telomere size standards.

PCR. To confirm ORF deletion identity, a general primer from inside the KanMX cassette (GCCATCAAAATGTATGGATGC) and a specific primer from the 5′ UTR of each ORF (20) were used. When necessary, the reaction was repeated with the KanMX primer and a primer complementary to the UPTAG primer that was used to create the deletion strains (GATGTCCACGAGGTCTCT). This PCR product was sequenced to identify the strain by its unique tag.

Cosegregation Test. Telomere length phenotypes of 27 candidate strains were checked by testing cosegregation of the length phenotype with the deletion (G418r). The candidate mutant strains were mated with BY4742 wild type, and the resulting heterozygous diploids were sporulated by the recommended method (17). Tetrads picked were scored for G418 resistance on yeast extract/peptone/dextrose plates supplemented with 400 mM G418 (Amersham Biosciences). Telomere length was estimated by Southern blot analysis. The presence of the KanMX cassette was confirmed by reprobing the Southern blots with a labeled ≈800-bp ScaI/NcoI fragment of pFA6 KanMX4 plasmid (21). All hybridizations with 26G and G418 were done at 55°C and 65°C, respectively.

Results

We have carried out a genome-wide screen for mutants affecting telomere length. A collection of 4,852 haploid-viable yeast strains, each deleted for a single ORF, was used. DNA from each strain in the collection was digested with XhoI, separated by gel electrophoresis under standardized conditions and subjected to Southern blot analysis with a telomere-specific probe. The telomeric probe produces a complex pattern, derived from hybridization to many telomeric fragments and to several subtelomeric repeats (22). The latter served as internal controls, because their electrophoretic mobility was usually not affected by the various mutations. The shortest fragments (≈1.3 kb in wild-type cells), resulting from Y′-containing telomeres, were the most reliable in determining telomeric length differences between strains, both because they represent multiple telomeres and because length differences are most pronounced in the shortest fragments. The next few bands, corresponding to telomeres containing an adjacent X element and no Y′ element (X′ telomeres), were also observed carefully to identify mutants with length alterations.

After the first round of screening, ≈600 mutants exhibiting possible short or long telomere phenotypes were retested by at least two additional rounds of fresh DNA preparations and Southern blotting. DNA from wild-type cells was run interspersed amongst the mutants in these gels to maximize the chances of correctly identifying mutants with modest effects on telomere length. By this very stringent criterion, 173 strains were identified that consistently exhibited either shorter or longer telomeres than wild type (Table 1). In addition, 26 other mutants were labeled as questionable gene candidates for telomere length phenotypes because they showed very mild telomere length phenotypes that failed to be detected in at least one repeat Southern blot (see Table 2, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site).

Table 1. List of S. cerevisiae genes that affect telomere length when deleted.

| Gene | Telomere phenotype | Function |

|---|---|---|

| DNA metabolism | ||

| EST1 | VS | Telomerase holoenzyme complex |

| EST2 | VS | Telomerase reverse transcriptase |

| EST3 | VS | Telomerase holoenzyme complex |

| TEL1 | VS | DNA damage response kinase |

| YKU70 | VS | DNA repair, Ku70/Ku80 complex |

| YKU80 | VS | DNA repair, Ku70/Ku80 complex |

| MRE11 | VS | DNA repair, MRX complex |

| RAD50 | VS | DNA repair, MRX complex |

| XRS2 | VS | DNA repair, MRX complex |

| RNH35* | VS | RNaseH, DNA replication; Int./Rif2 |

| DCC1 | S | Sister chromatid cohesion |

| HUR1 | S | DNA replication; Int./Mec3 |

| LRP1 | S | C1D ortholog, double-strand break repair |

| YPL205C | S | Overlaps with HRR25 |

| RIF1 | VL | Telomere maintenance, silencing |

| RIF2 | VL | Negative telomere regulator |

| ELG1 | VL | Genome stability |

| PIF1 | VL | Telomere maintenance, recombination |

| OGG1 | L | Base excision repair, shares PIF1 promoter |

| POL32* | sl | DNA polymerase Delta complex |

| MLH1* | sl | Mismatch DNA repair |

| CSM1 | sl | Meiotic chromosome segregation. Int./Zds2 |

| YML035C-A* | sl | Antisense to SRC1 |

| Chromatin, silencing, PolII transcription | ||

| HST1 | S | SIR2 homolog, histone deacetylase complex |

| SUM1 | S | Suppressor of sir mutants |

| RFM1 | S | Part of Hst1 histone deacetylase complex |

| SIN3 | S | Part of Rpd3 histone deacetylase complex |

| SAP30 | S | Part of Rpd3 histone deacetylase complex |

| OPI1 | S | Interacts with Sin3 |

| DEP1 | S | Part of the Rpd3 histone deacetylase complex |

| HDA2 | S | Part of the HDA histone deacetylase complex |

| CDC73 | S | Part of the Paf1 complex |

| RTF1 | S | Part of the Paf1 complex |

| BRE2 | S | Part of the SET1 histone methylase complex |

| MFT1** | ss | Tho and Paf1 complexes |

| THP2 | S | Tho and Paf1 complexes |

| SOH1** | S | Suppressor of hpr1 mutants (Tho and Paf1) |

| RPB9 | S | RNA polymerase II subunit |

| RPB4, CTF15 | S | RNA polymerase II subunit |

| SRB2 | S | Transcription, mediator complex |

| SRB5** | S | Transcription, mediator complex |

| RSC2 | S | RSC complex, chromatin modelling |

| CTK1 | S | PolII transcription regulation, protein kinase |

| SPT21** | S | PolII transcription, chromatin |

| CST6 | ss | Transcriptional activator, chromosome stability |

| NUP60* | ss | Silencing, part of the nuclear pore |

| HTL1** | VL | DNA replication and chromosome cycle |

| HPR1 | L | Tho and Paf1 complexes |

| HCM1 | L | Transcription factor (forkhead2) |

| MMS19** | L | PolII transcription (TFIIH) and repair |

| YDJ1* | sl | Forms a complex with Mms19 |

| SSN8 | L | Transcription, mediator complex |

| NUT1* | sl | Transcription, mediator complex |

| NFI1 | sl | SUMO ligase, chromatin protein |

| FMP26* | sl | Int./SAGA, reported mitochondrial protein |

| VPS65* | sl | Deletion affects SFH1 (RSC complex) |

| HMO1* | sl | ssDNA binding, HMG-box protein |

| NPL6 | sl | Protein—nucleus import |

| Vesicular traffic (vacuole, Golgi, ER, membrane synthesis) | ||

| CAX4 | VS | ER, N-glycosylation, phosphatase |

| VPS3 | S | Vacuolar sorting protein |

| VPS9 | S | Vacuolar sorting protein |

| VPS15** | S | Vacuolar sorting protein |

| VPS18 | S | Vacuolar sorting protein |

| VPS23** | S | Vacuolar sorting protein, ESCRT-I |

| VPS28** | S | Vacuolar sorting protein, ESCRT-I |

| VPS22** | S | Vacuolar sorting protein, ESCRT-II |

| VPS25** | ss | Vacuolar sorting protein, ESCRT-II |

| VPS36** | S | Vacuolar sorting protein, ESCRT-II |

| VPS32 | S | Vacuolar sorting protein, ESCRT III |

| YEL057C | S | Vacuolar sorting protein, ESCRT-III |

| BRO1 | S | Vacuolar sorting protein, after ESCRT-III |

| VPS34 | S | Vacuolar sorting protein |

| VPS39 | S | Vacuolar sorting protein |

| VPS75 | S | Vacuolar sorting protein |

| VPS43 | ss | Vacuolar sorting protein |

| APE3 | S | Vacuolar protein degradation |

| ATG11 | S | Vacuolar targeting |

| MOT3 | S | Suppressor of spt3, increased sterol levels |

| ARV1 | S | Sterol metabolism and transport |

| AGP2 | S | Carnitine transporter, fatty acid metabolism |

| YTA7 | S | Affects ergosterol and dolicol synthesis |

| PDX3** | S | Pyridoxine phosphate oxidase |

| ERJ5 | S | Golgi transport to ER |

| LST7 | S | Golgi-to-surface traffic protein |

| SUR4** | S | Fatty acid synthesis, transport |

| RPN4 | S | Ubiquitin degradation pathway |

| PMT3* | ss | Protein-O-mannosyl-transferase, ER |

| YSP3 | ss | Subtilisin-like peptidase |

| RNA metabolism | ||

| UPF1 | VS | Nonsense-mediated mRNA catabolism |

| UPF2 | VS | Nonsense-mediated mRNA catabolism |

| UPF3 | VS | Nonsense-mediated mRNA catabolism |

| KEM1 | VS | Exonuclease, mRNA degradation |

| RRP8 | sl | Methyltransferase, pre-rRNA processing |

| STO1 | sl | mRNA splicing and snRNA cap binding |

| LEA1 | sl | mRNA splicing |

| YPL105C* | sl | Unknown, Int./Mud2, Msl5 |

| YMR269W* | sl | Unknown, Int./elF2B |

| Cell polarity, cell wall, bud site selection | ||

| BEM4** | S | Cell polarity, actin organization |

| YOR322C | S | Clathrin-coated vesicles |

| BUD16** | S | Unknown, putative pyridoxal kinase |

| YPL041C | S | Int./cell wall mutants, phosphoglucomutase |

| YPL144W | S | Cell wall, phospholipids |

| SMI1 | S | Cell wall synthesis, chromatin binding |

| CCW14 | S | Cell wall structural protein |

| CSR2* | ss | Cell wall organization |

| GPB2 | ss | Pseudohyphal growth |

| SPS100 | ss | Spore wall assembly |

| LDB7 | L | Cell wall organization |

| BUD30 | sl | Bud site selection |

| BUD23* | sl | Bud site selection |

| BEM2* | sl | Polarity, cytoskeleton, budding |

| Protein modification and heat shock proteins | ||

| SSE1** | S | Antioxidative response, cochaperone |

| XDJ1** | S | Chaperone regulator |

| HSC82 | S | Heat shock protein |

| HCH1 | ss | Chaperone activator, Hsp90 suppressor |

| MAK10** | L | N-acetyltransferase |

| MAK31** | L | N-acetyltransferase |

| MAK3** | L | N-acetyltransferase |

| HSP104 | sl | Heat shock protein |

| CDH1 | sl | APC/cyclosome regulator |

| Ribosome and translation | ||

| RPP1A | VS | Large ribosomal subunit |

| RPL12B | S | Large ribosomal subunit |

| RPL13B | S | Large ribosomal subunit |

| RPL1B | S | Large ribosomal subunit |

| MRT4 | S | Ribosomal large subunit biogenesis |

| EAP1 | S | Translation regulation |

| RPS17A | VL | Small ribosomal subunit |

| RPS10A* | L | Small ribosomal subunit |

| RPS14A | L | Small ribosomal subunit |

| ASC1 | L | Ribosomal subunit |

| RPS16A* | sl | Small ribosomal subunit |

| RPS4B | sl | Small ribosomal subunit |

| HIT1*,** | sl | Ribosome assembly |

| Mitochondria | ||

| MRPL44 | S | Mitochondrial ribosomal subunit |

| MRPL38 | S | Mitochondrial ribosomal protein |

| MMM1 | S | Mitochondrial organization |

| ISA1 | S | Mitochondrial Fe/S protein maturation |

| PTC1 | S | Mitochondrial inheritance |

| TOM5* | ss | Mitochondrial outer membrane transport |

| PCP1 | ss | Mitochondrial protease |

| YIL042C | ss | Mitochondrial kinase |

| YDR115W | ss | Mitochondrial ribosomal protein |

| UGO1* | sl | Mitochondrial fusion |

| Nucleotide metabolism | ||

| PRS3 | VS | Ribose-phosphate pyrophosphokinase |

| MET7** | VS | Folylpolyglutamate synthetase |

| ADO1 | S | Adenosine kinase |

| ADE12 BRA9 | S | Adenylosuccinate synthetase |

| GCV3 | S | Folate production |

| Phosphate metabolism | ||

| PHO85** | S | Phosphate metabolism |

| PHO80** | S | Phosphate metabolism |

| GTR1 | S | Phosphate transport |

| PHO87** | L | Phosphate uptake |

| TAT2 | sl | Int./Pho23, synthetic lethality with pho85 |

| Nitrogen metabolism | ||

| URE2 | S | Nitrogen catabolite repression regulator |

| ARG2 | S | Glutamate acetyl transferase |

| Glycerol uptake | ||

| GUP1 | S | Glycerol uptake |

| GUP2* | sl | Glycerol uptake |

| Potassium transport | ||

| TRK1 | S | Potassium transporter |

| Killer toxin-related | ||

| FYV12* | sl | Killer toxin sensitive |

| KRE21 | sl | K1 killer toxin resistant |

| KRE28 | sl | Killer toxin resistant |

| PP2A-related | ||

| TPD3* | S | Phosphatase type 2A subunit |

| SIT4 | S | Phosphatase type 2A subunit |

| YOR1 | L | Multidrug resistant transporter, Int./PP2A |

| PPE1 | L | Protein modification, Int./PP2A |

| Unknown | ||

| YDL118W | VS | Unknown |

| YEL033W** | VS | Unknown (failed cosegregation test) |

| YGR042W | S | Unknown |

| YOL138C | S | Unknown |

| YMR031W-A | S | Unknown, overlaps YMR031c |

| YGL039W | sl | NADPH-related oxidoreductase |

| YOR008C-A | sl | Diepoxybutane and mitomycin C resistance |

Single knockout mutants of the listed 173 genes screened positive for telomere length defects in our analysis. Genes are grouped according to broad cellular function. The second column shows estimated average Y′ telomere lengths relative to wild-type length: ss, slightly short (<50 bp shorter than wild type); S, short (50-150 bp); VS, very short (>150 bp); sl, slightly long (<50 bp longer than wild type); L, long (50-150 bp); and VL, very long (>150 bp). Telomeric length was measured by plotting the peak signal of the shortest telomeric band (Y′ telomeres) against the positions of the added internal controls of the gels shown in Figs. 1 and 2 by using a Phospholmager and imagequant 4.1 software. Final telomeric length classification shown here is additionally based on data from other gels. Single asterisks indicate mutants that either showed average measured Y′ telomere length <25 bp different in size from those of wild-type cells in the gels shown in Figs. 1 and 2, or they showed length phenotypes inconsistent with reproducible phenotypes noted in all previous Southern blots. Because these mutants showed altered telomere lengths in all previous Southern blots, they are included in this table. Cosegregation test was carried out with the deletion mutants marked with a double asterisk. Int., interaction known with. Genes previously known to affect telomere length are indicated in bold. ER, endoplastic reticulum; snRNA, small nuclear RNA; ssDNA, single-stranded DNA; APC, antigen-presenting cell; SAGA, Spt/Ada/Gcn5 acetyltransferase; SUMO, small ubiquitin-related modifier.

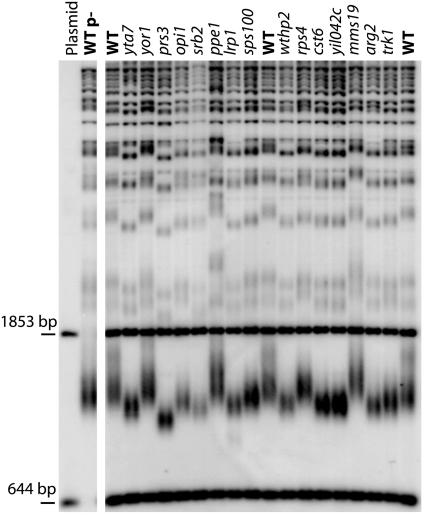

One additional DNA preparation and Southern blot analysis was then carried out to measure telomere length in each of the 173 mutants identified in the screen. The average telomeric length for the shortest telomeric fragment (Y′ telomeres) was then estimated by using fragments generated by restriction digests of a plasmid containing a cloned Saccharomyces telomere that were added to each genomic DNA sample. These telomeric fragments ran at positions above and below the Y′ telomeric bands and served as internal controls to measure size and to assure uniform migration of different samples (see Materials and Methods). Fig. 1 shows an example of one of these Southern blots, each of which was run on long gels (25 cm) to maximize resolution of telomeric length differences. The rest of these Southern blots are shown in Fig. 2, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site. Average Y′ telomere length for the wild-type strain was estimated from multiple samples run on the same gels. The change in Y′ telomere length relative to the wild type was then estimated for each of the 173 mutants. These values are presented in Table 3, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site. Of the 173 mutants in this last Southern blot analysis, 25 showed Y′ telomeres that had only slight length differences with the wild type control (<25 bp). We have not excluded them from our list because they had reproducibly shown slight length differences in all other Southern blots carried out. These mutants are marked with an asterisk in Table 1.

Fig. 1.

Representive Southern blot of mutants that alter S. cerevisiae telomere length. Southern blot of XhoI-digested DNA of single gene knockout mutants of S. cerevisiae probed with telomeric sequence. Gene or ORF names are indicated as are strain BY4741 controls (WT). Samples of DNA from mutants were combined with restriction-digested plasmid DNA to provide internal size standards. The two internal control bands are fragments of the plasmid pYt103 containing telomeric sequences that were generated by mixing separate digests done with BsmAI and with TaqI (producing the 1,835- and 644-bp fragments, respectively). The panel on the left shows a strain BY4741 control (WT p–) as well as the size standards without added yeast DNA.

The identity of each of the 173 mutants shown in Table 1 was confirmed by PCR analysis (see Materials and Methods). The sizes of the Y′ telomeres were grouped into the following categories: slightly short (<50 bp shorter than wild type), short (50–150 bp shorter than wild type), very short (>150 bp shorter than wild type), and equivalent categories for long telomere mutants (Table 1). Although consistently showing either long or short telomere length, many of the deletion strains exhibit some variation in the degree of their length phenotype when observed over repeated Southern blot analyses. We have considered the length phenotypes from all Southern blot analyses before assigning a gene to one of the phenotypic groups shown in Table 1. Of the mutants identified, 123 exhibited shorter and 50 showed longer telomeres than wild type. None of the newly identified mutants appeared to have the ever shortening phenotype characteristic of telomerase deletion mutants (23, 24). Several other mutants, listed in Table 4, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site, repeatedly had telomeres that were heterogeneous in length. Some of these appear to have Y′ telomeres of normal length but have elongated X telomeres, others displayed Y′ telomeres with a bimodal length distribution. Conceivably, the former might be altered in the uncharacterized mechanism that leads to size differences between X and Y′ telomeres (25).

We tested 27 of the mutants (marked with a double asterisk in Table 1) for cosegregation between the telomere phenotype, and we inserted the G418 resistance determinant in place of the deleted gene. All of these except one showed clear segregation of telomeric phenotype with G418 resistance. The single exception, yel033w, showed a short telomere phenotype that segregated independently from the antibiotic resistance. From our analysis, we conclude that the yel033w deletion segregates with a very slow growth phenotype and the short telomeres segregate with a suppressor mutation responsible for restored growth. Thus, YEL033W, a dubious ORF, appears to genetically interact with an unidentified gene with telomere function. Our results imply that in the vast majority of our strains, the telomere phenotype was caused by the relevant deletion.

Discussion

S. cerevisiae is the best understood system for studying telomere biology and many genes with roles in telomere function are already known in this organism. Nonetheless, our efforts have resulted in a wealth of additional candidate genes that alter telomere length when deleted. Our results indicate that a surprisingly large percentage of the yeast genome is in some way linked to telomere metabolism. The 173 genes listed in Table 1 represent ≈3.2% of the estimated 5,538 genes of S. cerevisiae. This number is certainly an underestimate of the total, given that >1,000 essential genes were not examined and because many genes known to mildly affect telomere length in other strains were not found in our screen.

Of the 32 genes previously known to exhibit a telomeric phenotype when singly deleted, our screen identified 18 (bold in Table 1). Genes not identified in our screen include some with reported phenotypes that were very mild. These include FOB1 (26), SWD1 and SWD3 (27), RRM3 (28), EBS1 (29), MLP1 and MLP2 (30), SIR3 (31), and DDC1 and RAD17 (32). We have not determined whether these genes were missed in our screen or whether they simply behave differently in our strain background. Of the four additional genes not identified in our screen, one (TOP3) (33) was not present in the collection. Two of the three others [GAL11 (34) and SIR4 (31) but not CTF18 (35)] showed mild telomere length phenotypes when individually reexamined (data not shown). It is not unexpected that mutants with slight telomere length alterations could be difficult to distinguish from wild type or even overlooked by our screen. Yeast telomeres are not only heterogeneous in size, but they are subject to size fluctuations even within clonal lineages (36). Although it is clear that our screen failed to detect all mutants with slight telomere length phenotypes, we are confident that it successfully identified the great majority of the nonessential genes that appreciably affect telomere length when deleted. Although absolute confidence that individual genes identified in this study affect telomere length will require additional experimentation, it is unlikely that our screen identified many false positives. Each mutant has had its telomere length examined several times and the identity of all has been confirmed through PCR testing. Moreover, 26 of 27 randomly sampled mutants have shown the expected meiotic cosegregation between the KanMX marker and the telomeric phenotype.

The genes identified in our screen have very diverse functions. Although some of them are probably directly involved in telomere metabolism, most are likely to affect telomere length indirectly either by altering the activity of proteins directly involved in telomere maintenance, or by eliciting cellular mechanisms that lead to changes in telomere length. The genes most likely to be directly involved in telomere size maintenance are those affecting DNA metabolism. In addition to the known DNA repair genes involved in telomere size control, such as components of the MRX (Mre11/Rad50/Xrs2) and Ku (Yku70/Yku80) complexes, we have identified LRP1, the yeast homolog of the human protein C1D (37). In mammalian cells, this is a γ-irradiation-inducible nuclear matrix protein that activates DNA PK (38). The yeast homologue has roles both in homologous recombination and in nonhomologous end-joining (37).

DCC1 encodes a component of an replication factor C-like clamp (RLC) loader complex that works with the Trf4 DNA polymerase to ensure proper sister chromatid cohesion during DNA replication (35). Although both Δdcc1 and Δtrf4 were identified among the short telomere strains, mutations in ELG1, the main component of an alternative RLC, lead to elongated telomeres (Table 1) (39, 40) and the Δrad24 strain, defective in a third RLC (41), exhibited no telomeric phenotype (data not shown). Another mutant with links to DNA replication, the deletion of which causes telomere shortening, is RNH35. This gene encodes a RNase H required for RNA primer removal during DNA synthesis (42). Its activity may be required for the coordination between replication of subtelomeric regions by the DNA polymerases and telomeric elongation by the telomerase. A similar role has been proposed for Elg1p (40).

Genes located in the proximity of the chromosomal ends are often subjected to epigenetic silencing, also known as telomeric position effect (43). Although many mutants that affect telomeric silencing have been isolated, not all of them exhibit changes in telomere length. Our screen has identified components of several complexes previously known to affect silencing that produce short telomeres. These components include the HST1-SUM1-RFM1 histone deacetylase (44) and the SIN3, SAP30, OPI1, and DEP1 genes, encoding components of the Rpd3 histone deacetylase complex (45, 46). In addition, we have identified several components of the Paf1, Set1, and Tho complexes, which seem to interact both in chromatin remodeling and during transcription elongation (reviewed in ref. 47). Moreover, mutations in certain components of the RSC, Mediator, and CTD phosphorylation complexes, which are located at the interphase of chromatin remodeling and RNA polymerase activation, also caused shortening of the telomeres. Not all of the nonessential members of these complexes reduced telomere length, suggesting that the link to telomere homeostasis may be due to the individual proteins in these complexes. The isolation of so many mutants that lead to shortened telomeres by interfering with chromatin remodeling functions suggests that chromatin integrity/modification plays an important role in elongating telomeres. We have also identified Δnup60 as a strain exhibiting short telomeres. Nup60 is required to anchor telomeres to the nuclear periphery, and a link between telomere position within the nucleus and chromatin remodeling affecting telomeric position effect has been shown (48). It is possible that telomere elongation also requires anchoring of telomeres to the nuclear periphery.

Many genes with known vacuolar functions showed telomere length alterations when individually deleted. The yeast vacuole is the functional analogue of the mammalian lysosome, the major site of degradation of both exogenous and endogenous macromolecules (reviewed in ref. 49). Prominent amongst these genes are components of the ESCRT (endosomal sorting complex required for transport) complexes. Three ESCRT complexes are known to bind in succession to ubiquinated cargos in late endosomes and function in the sorting of proteins to be degraded by vacuole/lysosome in the multivesicular bodies pathway, a well conserved process in eukaryotes (reviewed in ref. 50). The following 10 genes involved in this process display a short telomere phenotype when deleted. These genes encode components of the ESCRT complexes: Vps23; Vps28; Vps22; Vps25; Vps36; Vps32; Yel057c; a phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase, Vps34; its associated kinase, Vps15; and a downstream player in the process, Bro1 (51–53). Additional vacuolar genes identified include those that act in vacuolar targeting and fusion.

This connection between vacuolar targeting and telomere metabolism may be due to one or more telomeric proteins being regulated by degradation in the vacuole. Interfering with the vacuolar pathway could cause an increase in the level of these proteins, creating an imbalance in telomere size. At this moment there are no obvious telomeric proteins that are known to be degraded by means of this pathway.

In contrast to the >100 genes whose mutations led to short telomeres, only 50 deletion mutants exhibited a clear phenotype of elongated telomeres. The reason for this asymmetry is unclear. It likely indicates that there are more genes connected to telomerase-mediated sequence addition than there are to the negative regulation of that process. The mutants causing lengthening were more difficult to organize in clear functional categories. In addition to ELG1, discussed above, POL32, a nonessential subunit of DNA polymerase δ (54), is a candidate for having a direct link to telomere metabolism. Two additional genes causing telomere elongation affect chromosome segregation: CSM1, encoding a component of the kinetochore, and SRC1, which affects sister-chromatid segregation (55) and seems to be a target for cyclin-dependent kinase phosphorylation (56).

Deletion of only a few genes affecting chromatin/silencing caused telomere elongation. These genes include two components of the Mediator complex (NUT1 and SSN8) (57, 58), two components of the RSC complex (HTL1 and SFH1) (59, 60), and several less well characterized genes. For example, NPL6 was defined as a nuclear pore component; however, it binds histone H2B and many chromatin-remodeling factors and localizes to the nucleus (61).

Among the genes with long telomeres identified in our screen, there is only one clear case for which deletion of each subunit of a known complex caused a similar telomere phenotype. Deletion of each subunit of the NatC N-terminal acetyltransferase led to elongated telomeres. N-terminal acetylation is one of the most common cotranslational modification processes in eukaryotes (reviewed in ref. 62) and is carried out by one of three complexes in a substrate-specific fashion. In several cases, genes affecting telomere length are physically next to one another. Deletion of one could potentially alter telomere length by changing the expression of its neighbor. Examples include one neighbor of STN1 and both neighbors of PIF1 (including the DNA repair gene OGG1). In addition, there are at least six more pairs of neighboring genes in our list of candidates that show telomere length phenotype when individually deleted; they are listed in Table 5, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site.

Our genome-wide approach has allowed us to identify many genes that affect telomere length control. These reveal unexpected links to various aspects of the cellular metabolism. Given the conservation of telomere maintenance mechanisms throughout evolution, analysis of these genes will certainly be relevant to other eukaryotes and may have important consequences for therapeutic treatment of cancer.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This article is dedicated to the memory of Dr. Anat Krauskopf, who died before its completion. We thank Einat Zalckvar, Keren Rabinowitz, Rotem Prizant, Christine McPhillips, Marjorie Centeno, David Lynch, Jahaira Felix, and Matt Haas for help in the early stages of this project and the members of the Krauskopf and Kupiec laboratories for support and ideas. This work was supported by grants from the Israel Science Foundation (to M.K. and A.K.) and the U.S.A.–Israel Binational Fund and Israeli Cancer Research Fund (to A.K.), and by American Federation for Aging Research Grant A00001 and National Institutes of Health Grant GM61645-01 (to M.J.M.).

This paper was submitted directly (Track II) to the PNAS office.

Abbreviation: ESCRT, endosomal sorting complex required for transport.

References

- 1.McEachern, M. J., Krauskopf, A. & Blackburn, E. H. (2000) Annu. Rev. Genet. 34, 331–358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Watson, J. D. (1972) Nat. New Biol. 239, 197–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Olovnikov, A. M. (1996) Exp. Gerontol. 31, 443–448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Greider, C. W. & Blackburn, E. H. (1985) Cell 43, 405–413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Artandi, S. E., Chang, S., Lee, S. L., Alson, S., Gottlieb, G. J., Chin, L. & DePinho, R. A. (2000) Nature 406, 641–645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Counter, C. M., Hahn, W. C., Wei, W. Y., Caddle, S. D., Beijersbergen, R. L., Lansdorp, P. M., Sedivy, J. M. & Weinberg, R. A. (1998) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95, 14723–14728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Romanov, S. R., Kozakiewicz, B. K., Holst, C. R., Stampfer, M. R., Haupt, L. M. & Tlsty, T. D. (2001) Nature 409, 633–637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhu, J., Wang, H., Bishop, J. M. & Blackburn, E. H. (1999) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96, 3723–3728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bodnar, A. G., Ouellette, M., Frolkis, M., Holt, S. E., Chiu, C.-P., Morin, G. B., Harley, C. B., Shay, J. W., Lichtsteiner, S. & Wright, W. E. (1998) Science 279, 349–352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shay, J. W. & Bacchetti, S. (1997) Eur. J. Cancer 33, 787–791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kim, N. W., Piatyszek, M. A., Prowse, K. R., Harley, C. B., West, M. D., Ho, P. L. C., Coviello, G. M., Wright, W. E., Weinrich, S. L. & Shay, J. W. (1994) Science 266, 2011–2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Berman, J., Tachibana, C. Y. & Tye, B. K. (1986) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 83, 3713–3717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Blackburn, E. H. (2000) Nature 408, 53–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bertuch, A. & Lundblad, V. (1998) Trends Cell Biol. 8, 339–342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Craven, R. J., Greenwell, P. W., Dominska, M. & Petes, T. D. (2002) Genetics 161, 493–507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Adams, A. K. & Holm, C. (1996) Mol. Cell. Biol. 16, 4614–4620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Giaever, G., Chu, A. M., Ni, L., Connelly, C., Riles, L., Veronneau, S., Dow, S., Lucau-Danila, A., Anderson, K., Andre, B. et al. (2002) Nature 418, 387–391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Church, G. M. & Gilbert, W. (1984) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 81, 1991–1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shampay, J., Szostak, J. W. & Blackburn, E. H. (1984) Nature 310, 154–157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shoemaker, D. D., Lashkari, D. A., Morris, D., Mittmann, M. & Davis, R. W. (1996) Nat. Genet. 14, 450–456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wach, A., Brachat, A., Pohlmann, R. & Philippsen, P. (1994) Yeast 10, 1793–1808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zakian, V. A. & Blanton, H. M. (1988) Mol. Cell. Biol. 8, 2257–2260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lundblad, V. & Szostak, J. W. (1989) Cell 57, 633–643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lendvay, T. S., Morris, D. K., Sah, J., Balasubramanian, B. & Lundblad, V. (1996) Genetics 144, 1399–1412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Craven, R. J. & Petes, T. D. (1999) Genetics 152, 1531–1541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Weitao, T., Budd, M. & Campbell, J. L. (2003) Mutat. Res. 532, 157–172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Roguev, A., Schaft, D., Shevchenko, A., Pijnappel, W. W., Wilm, M., Aasland, R. & Stewart, A. F. (2001) EMBO J. 20, 7137–7148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ivessa, A. S., Zhou, J. Q., Schulz, V. P., Monson, E. K. & Zakian, V. A. (2002) Genes Dev. 16, 1383–1396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhou, J., Hidaka, K. & Futcher, B. (2000) Mol. Cell. Biol. 20, 1947–1955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hediger, F., Dubrana, K. & Gasser, S. M. (2002) J. Struct. Biol. 140, 79–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Palladino, F., Laroche, T., Gilson, E., Axelrod, A., Pillus, L. & Gasser, S. M. (1993) Cell 75, 543–555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Longhese, M. P., Paciotti, V., Neecke, H. & Lucchini, G. (2000) Genetics 155, 1577–1591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kim, R. A., Caron, P. R. & Wang, J. C. (1995) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 92, 2667–2671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Suzuki, Y. & Nishizawa, M. (1994) Mol. Cell. Biol. 14, 3791–3799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hanna, J. S., Kroll, E. S., Lundblad, V. & Spencer, F. A. (2001) Mol. Cell. Biol. 21, 3144–3158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shampay, J. & Blackburn, E. H. (1988) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 85, 534–538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Erdemir, T., Bilican, B., Cagatay, T., Goding, C. R. & Yavuzer, U. (2002) Mol. Microbiol. 46, 947–957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yavuzer, U., Smith, G. C. M., Bliss, T., Werner, D. & Jackson, S. P. (1998) Genes Dev. 12, 2188–2199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ben-Aroya, S., Koren, A., Liefshitz, B., Steinlauf, R. & Kupiec, M. (2003) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 100, 9906–9911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Smolikov, S., Mazor, Y. & Krauskopf, A. (2004) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 101, 1656–1661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Green, C. M., Erdjument-Bromage, H., Tempst, P. & Lowndes, N. F. (2000) Curr. Biol. 10, 39–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chen, J. Z., Qiu, J., Shen, B. & Holmquist, G. P. (2000) Nucleic Acids Res. 28, 3649–3656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gottschling, D. (1992) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 89, 4062–4065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.McCord, R., Pierce, M., Xie, J., Wonkatal, S., Mickel, C. & Vershon, A. K. (2003) Mol. Cell. Biol. 23, 2009–2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhang, Y., Sun, Z. W., Iratni, R., Erdjument-Bromage, H., Tempst, P., Hampsey, M. & Reinberg, D. (1998) Mol. Cell 1, 1021–1031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lamping, E., Luckl, J., Paltauf, F., Henry, S. A. & Kohlwein, S. D. (1994) Genetics 137, 55–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Krogan, N. J., Dover, J., Wood, A., Schneider, J., Heidt, J., Boateng, M. A., Dean, K., Ryan, O. W., Golshani, A., Johnston, M., et al. (2003) Mol. Cell 11, 721–729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Feuerbach, F., Galy, V., Trelles-Sticken, E., Fromont-Racine, M., Jacquier, A., Gilson, E., Olivo-Marin, J. C., Scherthan, H. & Nehrbass, U. (2002) Nat. Cell Biol. 4, 214–221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Teter, S. A. & Klionsky, D. J. (2000) Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 11, 173–179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bache, K. G., Brech, A., Mehlum, A. & Stenmark, H. (2003) J. Cell Biol. 162, 435–442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bilodeau, P. S., Urbanowski, J. L., Winistorfer, S. C. & Piper, R. C. (2002) Nat. Cell Biol. 4, 534–539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Stack, J. H., Dewald, D. B., Takegawa, K. & Emr, S. D. (1995) J. Cell Biol. 129, 321–334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Nikko, E., Marini, A. M. & Andre, B. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278, 50732–50743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Gerik, K. J., Li, X., Pautz, A. & Burgers, P. M. J. (1998) J. Biol. Chem. 273, 19747–19755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Rodriguez-Navarro, S., Igual, J. C. & Perez-Ortin, J. E. (2002) Yeast 19, 43–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ubersax, J. A., Woodbury, E. L., Quang, P. N., Paraz, M., Blethrow, J. D., Shah, K., Shokat, K. M. & Morgan, D. O. (2003) Nature 425, 859–864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Tabtiang, R. K. & Herskowitz, I. (1998) Mol. Cell. Biol. 18, 4707–4718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kuchin, S., Yeghiayan, P. & Carlson, M. (1995) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 92, 4006–4010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Romeo, M. J., Angus-Hill, M. L., Sobering, A. K., Kamada, Y., Cairns, B. R. & Levin, D. E. (2002) Mol. Cell. Biol. 22, 8165–8174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Cao, Y., Cairns, B., Kornberg, R. & Laurent, B. (1997) Mol. Cell. Biol. 17, 3323–3334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Nelson, M. K., Kurihara, T. & Silver, P. A. (1993) Genetics 134, 159–173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Polevoda, B. & Sherman, F. (2003) J. Mol. Biol. 325, 595–622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.