Abstract

Objectives

To assess the effect of preventive pravastatin treatment on coronary heart disease (CHD) morbidity and mortality in older persons at risk for cardiovascular disease (CVD), stratified according to plasma levels of homocysteine.

Design

A post hoc subanalysis in the PROspective Study of Pravastatin in the Elderly at Risk (PROSPER), started in 1997, which is a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial with a mean follow-up of 3.2 years.

Setting

Primary care setting in two of the three PROSPER study sites (Netherlands and Scotland).

Participants

Individuals (n = 3,522, aged 70–82, 1,765 male) with a history of or risk factors for CVD were ranked in three groups depending on baseline homocysteine level, sex, and study site.

Intervention

Pravastatin (40 mg) versus placebo.

Measurements

Fatal and nonfatal CHD and mortality.

Results

In the placebo group, participants with a high homocysteine level (n = 588) had a 1.8 higher risk (95% confidence interval (CI) = 1.2–2.5, P = .001) of fatal and nonfatal CHD than those with a low homocysteine level (n = 597). The absolute risk reduction in fatal and nonfatal CHD with pravastatin treatment was 1.6% (95% CI = −1.6 to 4.7%) in the low homocysteine group and 6.7% (95% CI = 2.7–10.7%) in the high homocysteine group (difference 5.2%, 95% CI = 0.11–10.3, P = .046). Therefore, the number needed to treat (NNT) with pravastatin for 3.2 years for benefit related to fatal and nonfatal CHD events was 14.8 (95% CI = 9.3–36.6) for high homocysteine and 64.5 (95% CI = 21.4–∞) for low homocysteine.

Conclusion

In older persons at risk of CVD, those with high homocysteine are at highest risk for fatal and nonfatal CHD. With pravastatin treatment, this group has the highest absolute risk reduction and the lowest NNT to prevent fatal and nonfatal CHD.

Keywords: homocysteine, older persons, cardiovascular risk, statins, prevention

The aim of cardiovascular risk management is to reduce the incidence of cardiovascular events in high-risk populations. Clinical cardiovascular risk scores, such as the Framingham Risk Score1 and the Systematic Coronary Risk Evaluation (SCORE),2 are used worldwide to select those with high cardiovascular risk, but their accuracy to predict risk of cardiovascular outcomes declines with advancing age.3–6 Because the prevalence and incidence of cardiovascular disease (CVD) increases exponentially with age,7–9 some have suggested that preventive treatment be offered to everyone over a specified age without measuring other risk factors,10 but others emphasize the need for risk stratification in old age.11,12 Recently, the Leiden 85-plus Study (and others) showed that homocysteine is predictive of cardiovascular events in old age.13–18

Because risk predictors are clinically meaningful only when effective preventive treatment is available,19 which treatment possibilities exist (and are appropriate) for older persons with high homocysteine to lower their cardiovascular risk needs to be established. Large randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and meta-analyses show that lowering plasma homocysteine using treatment with folate has no beneficial effect on the incidence of cardiovascular events.16,20,21 The PROspective Study of Pravastatin in the Elderly at Risk (PROSPER)22 has shown that pravastatin lowers the risk of coronary heart disease (CHD) in older people in general, but not the risk of fatal or nonfatal stroke. The current study was designed to determine whether older persons with high homocysteine levels would benefit more from this conventional preventive treatment than those with lower levels.

A post hoc subanalysis was performed in PROSPER (a large double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial) to assess the effect of pravastatin on CHD risk and mortality in older persons, stratified according to plasma level of homocysteine.

Methods

Study Design

The protocol of PROSPER has been published elsewhere.23 Briefly, in 1997 to 1999, 5,804 individuals were enrolled in Scotland (n = 2,520), Ireland (n = 2,184), and the Netherlands (n = 1,100). Men and women aged 70 to 82 were recruited, with preexisting vascular disease (coronary, cerebral, or peripheral) or at risk of such disease because of smoking, hypertension, or diabetes mellitus. Their plasma total cholesterol was required to be 154 to 347 mg/dL (4.0–9.0 mM) and their triglyceride concentrations 531 mg/dL or less (≤6.0 mM). Individuals with congestive heart failure (New York Heart Association functional class III or IV) or poor cognitive function (Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) score <24 points) were excluded. Participants were randomized to a group receiving 40 mg of pravastatin a day or to a control group receiving placebo and were followed (on average) for 3.2 years. Throughout the study, all study personnel were unaware of the allocated study medication status of the participants. The institutional ethics review boards of all centers approved the protocol, and all participants gave written informed consent.

Determination of Homocysteine

After blood was drawn, blood samples were kept at room temperature until they were processed in the laboratory to be stored in the biobank (−80°C). In 2010, homocysteine concentrations were measured in the biobank ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid plasma samples, from samples taken at baseline (blood samples, n = 5,757; missing, n = 47) and again at 6 months. Measurements were done in batches after reduction to the free form with a fluorescence polarization immunoassay (IMx analyzer; Abbott, Abbott Park, IL).

The median plasma homocysteine level was 14.1 μM (interquartile range (IQR) 11.8–17.0) in the Netherlands (n = 1,100), 17.9 μM (IQR 15.3–21.8) in Scotland (n = 2,505), and 18.8 μM (IQR 15.6–23.3) in Ireland (n = 2,152), although there were differences in standard operating procedures between the study sites. (The Dutch and Scottish blood samples were processed within 8 hours, whereas in Ireland, this processing frequently exceeded 8 hours.) Statistical analysis showed that the variance in log homocysteine for Scotland and the Netherlands was comparable (F = 2.4, P = .12), but both were significantly different from Ireland (Scotland vs Ireland, F = 5.4, P = .02; the Netherlands vs Ireland, F = 11.2, P = .001). Because plasma homocysteine levels increase by 0.5 to 1.0 μM/h in blood at room temperature,24–26 differences in lag time could explain the differences in variance between Ireland and the other countries. Therefore, it was decided to exclude participants from Ireland from this analysis.

Outcomes

The outcomes, described in the design of PROSPER,23 were the incidence of fatal and nonfatal CHD (including definite or suspected CHD mortality and nonfatal myocardial infarction (MI)), nonfatal MI, CHD mortality, non-CHD mortality, and all-cause mortality. The PROSPER Endpoints Committee, which was blinded to study medication and plasma levels of homocysteine, assessed all CHD endpoints.

Data Analysis

At baseline, participants were ranked in three groups equal in size (low, medium, and high homocysteine) based on plasma homocysteine level, sex, and study site. Within each homocysteine group, the baseline characteristics of the placebo and treatment groups were compared using independent t-tests for continuous data and Pearson chi-square tests (degrees of freedom (df) = 1) for categorical data.

Predictive Value of Homocysteine in the Placebo Group

The cumulative incidence rates of fatal and nonfatal CHD and all-cause mortality for the three homocysteine groups were calculated using Kaplan–Meier curves and compared using the log rank test (df = 2). Hazard ratios (HRs) and corresponding 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs) for sex- and study site–specific tertiles of homocysteine were calculated for the endpoints using Cox proportional hazard models (reference low homocysteine), with adjustment for age. To further investigate the independent predictive value of homocysteine, baseline history of CVD, baseline Framingham risk factors (smoking, diabetes mellitus, left ventricle hypertrophy, systolic blood pressure, total cholesterol, high density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C)), and earlier published predictors in PROSPER (C-reactive protein (CRP), and creatinine clearance (Cockcroft-Gault)) were also adjusted for.

Treatment Effect Comparing the Placebo and Treatment Groups

The treatment effects of pravastatin and placebo according to homocysteine group were calculated using two methods. First, according to homocysteine group, the cumulative incidence rate for fatal and nonfatal CHD and all-cause mortality are presented for those taking placebo and those taking pravastatin with Kaplan–Meier curves and compared using the log rank test (df = 1) and Cox proportional hazard models. No adjustments were made. The presence of multiplicative interaction was formally tested by adding the interaction term (treatment × homocysteine group) to the Cox regression model. All analyses were on an intention-to-treat basis.

Second, the absolute risk reduction according to treatment with pravastatin was calculated. Differences in absolute risk reductions between the homocysteine groups were tested using a z-test. Numbers needed to treat (NNT) to benefit were calculated over the mean follow-up of the trial (3.2 years) based on the difference in cumulative proportion surviving in the placebo and pravastatin groups.27,28 Because creatinine clearance seems to be associated with homocysteine levels, a subgroup analysis for absolute risk reduction was conducted for fatal and nonfatal CHD and for all-cause mortality in participants with creatinine clearance of 30 mL/min or greater.

Influence of Treatment with Pravastatin on Homocysteine

To investigate whether pravastatin treatment influences plasma homocysteine levels, homocysteine concentrations were measured after 6 months of treatment for 1,832 participants (183 taking placebo, 1,649 taking pravastatin). The effect of pravastatin treatment on plasma homocysteine levels was tested after 6 months using linear regression analysis adjusted for baseline homocysteine.

Results

In total, 3,620 PROSPER participants from the Netherlands and Scotland were eligible for this study. Because 15 participants had missing biobank samples, and 83 had missing homocysteine measurements, 3,522 participants (1,764 placebo, 1,758 pravastatin) were included in the analyses. The cutoff values of the homocysteine tertiles (33% and 67%) in the Netherlands (n = 1,049) were 11.7 and 14.7 μM, respectively, for women and 13.5 and 16.9 μM, respectively, for men; for Scotland (n = 2,473) these limits were 15.4 and 19.6 μM, respectively, for women, and 16.9 and 21.0 μM, respectively, for men.

Baseline Characteristics

Table 1 presents baseline characteristics of the total group of participants and according to homocysteine group, stratified for placebo or pravastatin. In the total group, the mean age of participants was 75.3 ± 3.4, and 48% had a history of CVD. Mean homocysteine level at baseline was 18.3 ± 7.1 μM. There were no differences according to homocysteine group in baseline characteristics between the pravastatin and placebo groups. The proportion of participants with diabetes mellitus was lower in the high homocysteine group.

Table 1.

Baseline Participant Characteristics According to Treatment and Homocysteine Level (n = 3,522)

| Homocysteine Level | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low | Medium | High | |||||

| Characteristic | All | Placebo, n = 597 | Pravastatin, n = 575 | Placebo, n = 579 | Pravastatin, n = 598 | Placebo, n = 588 | Pravastatin, n = 585 |

| Demographic and functional characteristics | |||||||

| Study site Scotland, n (%) | 2,473 (70) | 424 (71) | 400 (70) | 400 (69) | 425 (71) | 416 (71) | 408 (70) |

| Male, n (%) | 1,765 (50) | 296 (50) | 291 (51) | 286 (49) | 304 (51) | 285 (49) | 303 (52) |

| Age, mean ± SD | 75.3 ± 3.4 | 74.9 ± 3.4 | 74.9 ± 3.3 | 75.2 ± 3.2 | 75.2 ± 3.3 | 75.6 ± 3.5 | 75.7 ± 3.4 |

| Mini-Mental State Examination score, mean ± SD | 28.2 ± 1.5 | 28.3 ± 1.4 | 28.3 ± 1.4 | 28.3 ± 1.4 | 28.2 ± 1.5 | 28.1 ± 1.5 | 28.0 ± 1.6 |

| Barthel index, mean± SD | 19.8 ± 0.7 | 19.7 ± 0.7 | 19.8 ± 0.8 | 19.8 ± 0.7 | 19.8 ± 0.5 | 19.7 ± 0.8 | 19.7 ± 0.9 |

| Instrumental activity of daily living score, mean ± SD | 13.6 ± 0.9 | 13.6 ± 0.9 | 13.6 ± 0.9 | 13.7 ± 0.9 | 13.7 ± 0.7 | 13.6 ± 1.1 | 13.5 ± 1.0 |

| Clinical history and cardiovascular risk factors | |||||||

| History of cardiovascular diseasea | 1,675 (48) | 267 (45) | 272 (47) | 269 (47) | 279 (47) | 298 (51) | 290 (50) |

| History of diabetes mellitus | 386 (11) | 88 (15) | 85 (15) | 68 (12) | 57 (9.5) | 45 (7.7) | 43 (7.4) |

| Creatinine clearance <30 mL/minb | 96 (2.7) | 12 (2.0) | 15 (2.6) | 14 (2.4) | 16 (2.7) | 17 (2.9) | 22 (3.8) |

| Body mass index, kg/m2, mean ± SD | 27.0 ± 5.5 | 26.9 ± 5.6 | 26.9 ± 5.5 | 27.3 ± 5.7 | 27.0 ± 5.3 | 27.2 ± 5.6 | 26.8 ± 5.4 |

| Current smoker | 943 (27) | 157 (26) | 137 (24) | 156 (27) | 166 (28) | 167 (28) | 160 (27) |

| Alcohol, U/wk, mean ± SDc | 5.3 ± 8.4 | 4.9 ± 7.3 | 5.0 ± 7.5 | 5.5 ± 8.7 | 5.6 ± 9.5 | 4.9 ± 7.7 | 5.7 ± 9.4 |

| Systolic blood pressure, mmHg, mean ± SD | 154.7 ± 21.4 | 153.4 ± 20.6 | 154.1 ± 21.1 | 156.0 ± 20.5 | 154.2 ± 21.2 | 155.4 ± 23.1 | 155.2 ± 21.6 |

| Total cholesterol, mg/dL, mean ± SD | 220.7 ± 35.5 | 218.4 ± 34.9 | 219.6 ± 35.8 | 220.8 ± 33.9 | 221.5 ± 35.2 | 220.2 ± 36.0 | 223.6 ± 36.9 |

| Low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, mg/dL, mean ± SD | 148.5 ± 31.0 | 146.8 ± 30.9 | 147.6 ± 30.3 | 148.9 ± 29.8 | 148.6 ± 31.1 | 147.9 ± 32.1 | 151.1 ± 32.0 |

| High-density lipoprotein cholesterol, mg/dL, mean ± SD | 49.2 ± 13.4 | 49.8 ± 12.6 | 48.8 ± 13.0 | 49.2 ± 13.0 | 49.3 ± 13.1 | 49.2 ± 14.5 | 49.3 ± 14.1 |

| Triglycerides, mg/dL, mean ± SD | 136.5 ± 61.2 | 131.4 ± 59.1 | 138.2 ± 63.4 | 136.1 ± 58.5 | 140.4 ± 66.2 | 136.5 ± 60.8 | 136.5 ± 58.4 |

| Homocysteine, μM, mean ± SD | 18.3 ± 7.1 | 13.0 ± 2.1 | 13.1 ± 2.1 | 16.8 ± 2.2 | 17.0 ± 2.2 | 25.2 ± 8.6 | 24.6 ± 8.2 |

SD = Standard Deviation.

Stable angina pectoris, intermittent claudication, stroke, transient ischemic attack, myocardial infarction, peripheral arterial disease surgery, or amputation for vascular disease ≥6 months before study entry.

Calculated using the Cockroft-Gault formula.

1 U = 60 mL distilled spirits, 170 mL wine, or 300 mL beer.

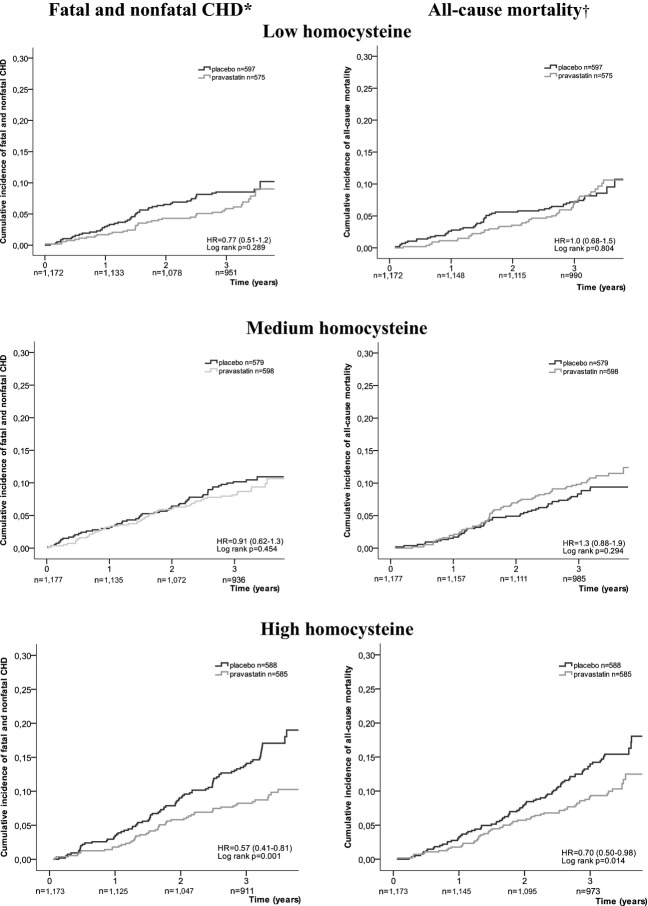

Predictive Value of Homocysteine in the Placebo Group

Figure 1 shows the cumulative incidence of fatal and nonfatal CHD and all-cause mortality for the three homocysteine groups in the placebo group. Participants with medium homocysteine levels had no greater risk of fatal and nonfatal CHD than those with low homocysteine (HR = 1.1, 95% CI = 0.76–1.6, P = .57), but those with high homocysteine had a 1.8 times greater risk (95% CI = 1.2–2.5, P = .001). For overall mortality, the HRs were 1.0 (95% CI = 0.67–1.5, P = .99) and 1.7 (95% CI = 1.2–2.5, P = .003), respectively. These estimates did not change after additional adjustments for history of CVD; Framingham risk factors; or CRP, HDL-C, and creatinine clearance (data not shown).

Figure 1.

Cumulative incidence of fatal and nonfatal coronary heart disease (CHD) and all-cause mortality depending on baseline plasma levels of homocysteine in the placebo group (n = 1,764). HR = Hazard Ratio; CI = Confidence Interval: high versus low homocysteine group, adjusted for age.

Similarly, participants with high homocysteine levels had a greater risk of nonfatal MI, CHD mortality, and non-CHD mortality. Furthermore, no differences in risk were found between the medium and low homocysteine level groups for any of these outcomes (data not shown).

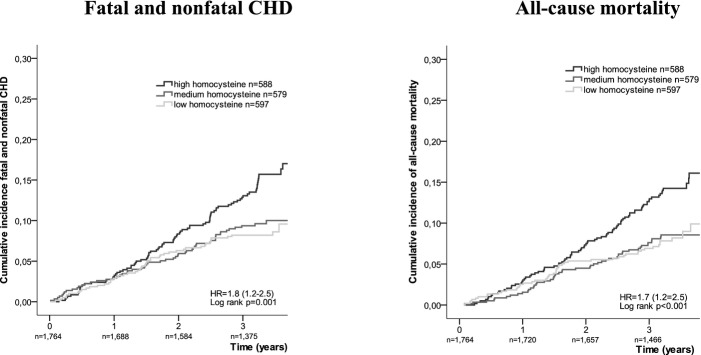

Treatment Effect Depending on Homocysteine

Figure 2 presents the cumulative incidence of fatal and nonfatal CHD and all-cause mortality in participants with and without pravastatin according to homocysteine group. In participants with high homocysteine, an HR of 0.57 (95% CI = 0.41–0.81, P = .002) was found as the treatment effect of pravastatin on fatal and nonfatal CHD, and an HR of 0.70 (95% CI = 0.50–0.98, P = .04) as the treatment effect on all-cause mortality. With medium and low homocysteine levels, there was no significant difference in cumulative incidence between placebo and pravastatin treatment.

Figure 2.

Cumulative incidence fatal and nonfatal coronary heart disease (CHD) and all-cause mortality depending on pravastatin treatment, stratified according to plasma homocysteine level at baseline. *P for multiplicative interaction = .21, †P for multiplicative interaction = .10.

Moreover, multiplicative interaction was not found between treatment and homocysteine group (fatal and nonfatal CHD: P for multiplicative interaction = .208, all-cause mortality: P for multiplicative interaction = .097; Figure 2). Similar patterns were seen for nonfatal MI and CHD mortality. For non-CHD mortality, no effect of treatment with pravastatin was found in any of the three homocysteine groups (data not shown).

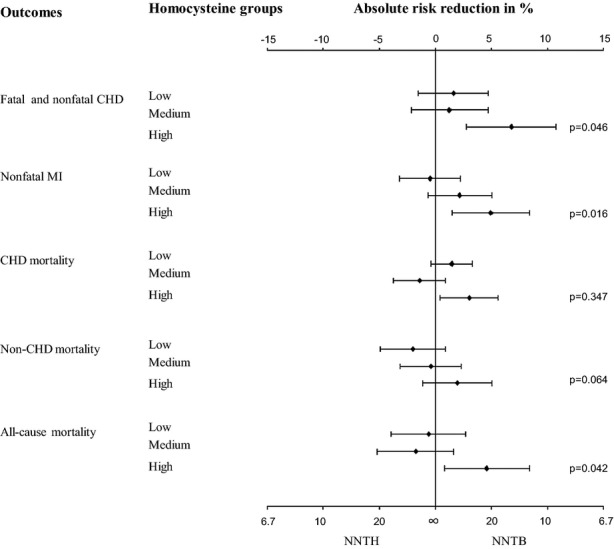

Table 2 presents absolute treatment effects of pravastatin according to homocysteine group. The absolute risk reduction in fatal and nonfatal CHD with pravastatin treatment was 1.6% (95% CI = −1.6 to 4.7) in the low homocysteine group and 6.7% (95% CI = 2.7–10.7) in the high homocysteine group (absolute risk reduction difference = 5.2%, 95% CI = 0.11–10.3, P = .046). For all-cause mortality, the absolute risk reductions were −0.66% (95% CI = −4.0 to 2.7) and 4.6% (95% CI = 0.78–8.4), respectively (absolute risk reduction difference = 5.2%, 95% CI = 0.19–10.3, P = .04).

Table 2.

Absolute Effect of Treatment with Pravastatin on Cardiovascular Outcomes and Mortality After 3.2 Years According to Homocysteine Level

| Placebo | Pravastatin | ARR (95% CI) | Difference in ARR (vs Low) (95% CI) | P-Valueb | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcomes and Homocysteine Groupsa | n | Cumulative Incidence of Events,% (95% CI) | n | Cumulative Incidence of Events,% (95% CI) | |||

| Fatal and nonfatal CHD | |||||||

| Low | 48 | 8.2 (6.0–10.5) | 32 | 6.7 (4.5–8.9) | 1.6 (−1.6–4.7) | Reference | |

| Medium | 54 | 9.9 (7.4–12.4) | 47 | 8.7 (6.3–11.0) | 1.2 (−2.2–4.7) | −0.32 (−5.0–4.3) | .89 |

| High | 76 | 15.9 (12.8–19.1) | 47 | 9.2 (6.7–11.7) | 6.7 (2.7–10.7) | 5.2 (0.11–10.3) | .046 |

| Nonfatal MI | |||||||

| Low | 29 | 5.1 (3.3–6.9) | 26 | 5.6 (3.6–7.7) | −0.5 (−3.2–2.2) | Reference | |

| Medium | 39 | 7.3 (5.1–9.5) | 26 | 5.1 (3.2–7.0) | 2.2 (−0.73–5.0) | 2.7 (−1.3–6.7) | .18 |

| High | 51 | 11.3 (8.5–14.1) | 32 | 6.4 (4.3–8.5) | 4.9 (1.4–8.4) | 5.5 (1.0–9.9) | .02 |

| CHD mortality | |||||||

| Low | 20 | 3.4 (1.9–4.9) | 11 | 2.0 (0.83–3.2) | 1.4 (–0.45–3.3) | Reference | |

| Medium | 18 | 3.3 (1.8–4.7) | 27 | 4.7 (3.0–6.4) | −1.5 (−3.7–0.83) | −2.9 (−5.8–0.08) | .06 |

| High | 33 | 6.5 (4.4–8.6) | 18 | 3.5 (1.9–5.1) | 3.0 (0.35–5.6) | 1.5 (−1.7–4.8) | .35 |

| Non-CHD mortality | |||||||

| Low | 25 | 4.8 (3.0–6.6) | 31 | 6.9 (4.6–9.1) | −2.1 (−4.9–0.84) | Reference | |

| Medium | 30 | 5.4 (3.5–7.3) | 32 | 5.9 (3.9–7.8) | −0.46 (−3.2–2.3) | 1.6 (−2.4–5.6) | .43 |

| High | 46 | 8.4 (6.1–10.7) | 34 | 6.5 (4.4–8.5) | 2.0 (−1.2–5.1) | 4.0 (−0.24–8.2) | .06 |

| All-cause mortality | |||||||

| Low | 45 | 8.0 (5.8–10.3) | 42 | 8.7 (6.3–11.1) | −0.66 (−4.0–2.7) | Reference | |

| Medium | 48 | 8.5 (6.2–10.8) | 59 | 10.3 (7.8–12.8) | −1.8 (−5.2–1.6) | −1.1 (−5.9–3.6) | .64 |

| High | 79 | 14.3 (11.4–17.2) | 52 | 9.8 (7.3–12.2) | 4.6 (0.78–8.4) | 5.2 (0.19–10.3) | .04 |

CI = confidence interval; CHD = coronary heart disease.

Group sizes: low: placebo n = 597, pravastatin n = 575; medium: placebo n = 579, pravastatin n = 598; high: placebo n = 588, pravastatin n = 585.

P-value of difference in absolute risk reduction (ARR) compared with reference group low homocysteine estimated using z-test.

Mean homocysteine values of 18.3 μM were found in persons with creatinine clearance of 30 mL/min or greater (n = 3,426) and of 19.0 μM (P = .29) in persons with creatinine clearance of <30 mL/min (n = 96). Because creatinine clearance is known to be associated with homocysteine level, a subgroup analysis was conducted in persons with creatinine clearance of 30 mL/min or greater. The differences in absolute risk reductions according to pravastatin treatment remained similar (fatal and nonfatal CHD 6.0%, 95% CI = 0.84–11.1, P = .02; all-cause mortality 5.8%, 95% CI = 0.70–11.0, P = .03).

For fatal and nonfatal CHD, the NNT with pravastatin to benefit for 3.2 years was 14.8 (95% CI = 9.3–36.6) in the high homocysteine group, 81.3 (95% CI = 21.5–∞) in the medium homocysteine group, and 64.5 (95% CI = 21.4–∞) in the low homocysteine group (high vs low, P = .046) (Figure 3). For all-cause mortality, a beneficial result was found in the high homocysteine group (NNT = 21.8, 95% CI = 11.9–129) but no benefit in the medium and low homocysteine groups (high vs low, P = .04).

Figure 3.

Number needed to treat (NNT) with pravastatin after 3.2 years according to homocysteine level at baseline. P-value of difference between high and low homocysteine group for absolute risk reduction in% and for NNT estimated using z-test. NNTH = NNT to Harm; NNTB = NNT to Benefit; CHD = Coronary Heart Disease; MI = Myocardial Infarction.

Influence of Pravastatin on Homocysteine

After 6 months of treatment, homocysteine levels had fallen −0.52 μM (95% CI = −1.1 to 0.07) from baseline for those on pravastatin (linear regression, P = .08).

Discussion

This study suggests that homocysteine may be a promising new CHD risk predictor in older people, because high plasma homocysteine levels not only indicate older persons at high risk for fatal and nonfatal CHD and all-cause mortality, but also identify those with the highest absolute risk reduction due to the use of pravastatin and the lowest NNT to prevent fatal and nonfatal CHD.

Earlier studies showed that older persons with high homocysteine levels are at greater risk of cardiovascular events, and homocysteine level may provide additional risk stratification beyond traditional risk factors.13–18 For example, a previous study examined whether adding homocysteine to a model based on traditional CVD risk factors improved classification. In two younger population cohorts, they found that addition of homocysteine level to Framingham risk score significantly improved risk prediction.18 Moreover, for persons aged 85 and older, a previous study showed that the classic risk factors as included in the Framingham risk score no longer accurately predicted cardiovascular mortality in those with no history of CVD, whereas a single measurement of homocysteine accurately identified those at high risk of cardiovascular mortality.13 The findings of the current study not only confirm studies reporting that homocysteine predicts CHD risk in old age, but also show the independent predictive capacity in a selected population of older persons with high cardiovascular risk. A recent metaanalysis showed that a moderate homocysteine elevation due to genetic variance does not meaningfully affect CHD risk.29 This finding indicates that circulating homocysteine levels within the normal range are not causally related to CHD risk. Moreover, large RCTs and their meta-analyses show that lowering plasma homocysteine by treatment with folate has no beneficial effect on the incidence of cardiovascular events.16,20,21 Therefore, the underlying biological pathway to explain the predictive value of high homocysteine levels for CVD, if there is one, is unknown. Homocysteine may be seen as an epiphenomenon rather than a causal agent, but this does not refute its predictive abilities.

Because homocysteine was found to be not causally related to CVD, whether preventive treatment could be offered to those with high homocysteine to reduce their cardiovascular risk is unknown. In the Air Force/Texas Coronary Atherosclerosis Prevention Study (AFCAPS/TexCAPS),30 with only a small proportion of older adults, the beneficial effect of statin treatment in people with high homocysteine levels was limited to people with a low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) level higher than 149 mg/dL. There results further extend the findings from the AFCAPS/TexCAPS by demonstrating that the benefits of statin treatment may differ according to homocysteine level in high-risk individuals with an average LDL-C level of 148 mg/dL. If these findings hold true in a subsequent study, there could be a role for measurement of homocysteine levels to help guide decisions on statin use in older adults, which is a widely available treatment. This is an important criterion underlying screening.19

The present study revealed other findings that deserve further examination. First, although a clear CHD risk benefit from pravastatin therapy over the trial period of 3.2 years was found only in older persons with high and not those with low and medium homocysteine levels, a multiplicative interaction for the treatment effect was not found. Therefore, there is a possibility that pravastatin has the same treatment effect in all three homocysteine groups, although even when the relative treatment effect is similar between these groups, those at highest absolute risk will have the most benefit in terms of absolute risk reduction. This absolute risk reduction and corresponding NNT is important in clinical practice and guidelines, because it indicates the number of persons who need to be treated to prevent one event.

Second, the effect of pravastatin in the homocysteine groups does not show a linear trend. A lack of power because of a small number of events in the low and medium homocysteine level groups could explain this finding, so the possibility of random variation cannot be excluded, although it is also possible that pravastatin therapy is effective only in people with homocysteine levels greater than a certain cutoff value. The possibility of absolute cutoff values requires more in-depth study, investigated in a population with consistent blood sampling and storage procedures.

Third, it was found that plasma levels of homocysteine did not change significantly with pravastatin treatment over a 6-month period, although a small reduction was seen. Further examination is needed to determine the effect of pravastatin treatment on homocysteine levels. If pravastatin does not affect homocysteine levels, homocysteine measurement might be useful to evaluate the need for continuing preventive cardiovascular therapy in persons under pravastatin treatment.

For new biomarkers, others have investigated whether high cardiovascular risk and corresponding benefit from treatment can be predicted. A large-scale RCT31 and an earlier analysis in PROSPER32 showed that baseline CRP concentration predicts cardiovascular risk but not the relative CHD risk benefits of pravastatin therapy. Other analyses in PROSPER showed that HDL-C33 and creatinine clearance34 can predict benefit from pravastatin therapy for prevention of fatal and nonfatal CHD, although a high plasma homocysteine level remained predictive of a beneficial effect of pravastatin even in persons with creatinine clearance of 30 mL/min or greater. Furthermore, pravastatin was more effective in preventing cardiovascular events in those without diabetes mellitus.22 The current study showed that adjustment for these predictors did not influence the predictive value of homocysteine. A next step is to study the clinical value of homocysteine and other biomarkers by comparing their predictive value in combination with treatment response to develop the most-effective predictors of cardiovascular risk and treatment benefit. This is particularly important because statins are not without side effects or costs, and targeting those most at risk and with the most to gain would be clinically and economically advantageous.

Strength and Limitations

This study was embedded in PROSPER, a large double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial in older persons. This landmark clinical cardiovascular trial was performed following guidelines of good clinical practice, including endpoints that the Endpoint Committee uniformly assessed. Because homocysteine was assessed after closure of the trial, plasma levels of homocysteine had no influence on the study procedures, clinical treatment during follow-up, or the decisions of the Endpoint Committee.

A limitation of this study is that PROSPER procedures were not originally designed to collect optimal blood samples for the assessment of plasma homocysteine. Therefore, data could be used from only two of the three PROSPER study sites, although it is possible that some samples from those two sites were stored at room temperature for up to 8 hours before they were processed in the laboratory. This could have led to artificially high homocysteine plasma levels and therefore to misclassification in a higher homocysteine group. Because it was assumed that the samples with artificially high homocysteine levels are spread nondifferential in the population, this could have resulted in underestimation of the differences in treatment effect by homocysteine levels. Because it is also known that homocysteine levels vary between countries,13,35,36 more studies are needed to validate the absolute cutoff values of homocysteine to select elderly adults at highest risk in clinical practice.

Moreover, data regarding the use of B vitamins, which lower homocysteine levels, are not available. Another limitation of this study is that the treatment-by-homocysteine group multiplicative interaction was not significant, although the difference in absolute risk reduction between high and low homocysteine was significant (P = .046 for fatal and nonfatal CHD and P = .04 for all-cause mortality). The possibility of a type 1 error from multiple comparisons cannot be excluded.

It might also be seen as a limitation that these analyses focused only on homocysteine level to predict CHD risk and treatment effect, rather than investigating the etiological mechanisms behind the findings. Predictive and etiological studies will contribute to the further development of cardiovascular risk management in older adults, both on their own merits.

Implications

A recent analysis of cost-effectiveness of statin treatment in primary care showed that, even in older adults, it is useful to stratify for risk of cardiovascular outcomes.12 The current study shows that homocysteine may predict CHD risk in the PROSPER population of older adults with high cardiovascular risks. As a consequence, individuals without traditional risk factors and thus with the lowest risks were excluded. Before these results can be implemented in current guidelines, further research is needed to find a cutoff value of homocysteine and confirm that high-risk older adults with high homocysteine levels obtain more benefit from pravastatin treatment. Moreover, whether homocysteine is useful in predicting benefits from pravastatin treatment for low- or intermediate-risk older adults remains to be investigated.

Homocysteine is a promising CHD risk predictor in old age, not only because high plasma homocysteine identifies older adults at high risk of fatal and nonfatal CHD, but also because those persons have the highest absolute risk reduction with pravastatin treatment and the lowest NNT to prevent fatal and nonfatal CHD. This is an important step in the further development of CHD risk stratification and treatment for older people.

Acknowledgments

Conflict of Interest: There are no conflicts of interest or financial interest of the authors. The work in PROSPER was supported by an unrestricted investigator-initiated grant from Bristol-Myers Squibb, USA. This granted post hoc subanalysis in the PROSPER Study was funded by an unrestricted grant from the Netherlands Organization for Health Research and Development (ZonMw; 2009).

Author Contributions: J. Gussekloo had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. Drewes: analysis and interpretation of data, drafting of the manuscript, critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content. Poortvliet: analysis and interpretation of data, critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content. Blom: study concept and design, analysis and interpretation of data, critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content, obtained funding. de Ruijter: study concept and design, critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content. Westendorp: study concept and design, acquisition of data, critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content. Stott: acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation of data, critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content. Blom, Ford, Sattar, Jukema: acquisition of data, critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content. Assendelft: study concept and design, analysis and interpretation of data, critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content. de Craen: study concept and design, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation of data, critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content. Gussekloo: study concept and design, analysis and interpretation of data, drafting of the manuscript, critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content, obtained funding.

Sponsor’s Role: The funders played no role in study design; collection, analysis, or interpretation of data; writing of the report; or the decision to submit the article for publication.

References

- Anderson KM, Odell PM, Wilson PW, et al. Cardiovascular disease risk profiles. Am Heart J. 1991;121:293–298. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(91)90861-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conroy RM, Pyorala K, Fitzgerald AP, et al. Estimation of ten-year risk of fatal cardiovascular disease in Europe: The SCORE project. Eur Heart J. 2003;24:987–1003. doi: 10.1016/s0195-668x(03)00114-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lernfelt B, Svanborg A. Change in blood pressure in the age interval 70–90. Late blood pressure peak related to longer survival. Blood Press. 2002;11:206–212. doi: 10.1080/08037050213759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schatz IJ, Masaki K, Yano K, et al. Cholesterol and all-cause mortality in elderly people from the Honolulu Heart Program: A cohort study. Lancet. 2001;358:351–355. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(01)05553-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Bemmel T, Gussekloo J, Westendorp RG, et al. In a population-based prospective study, no association between high blood pressure and mortality after age 85 years. J Hypertens. 2006;24:287–292. doi: 10.1097/01.hjh.0000200513.48441.8e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weverling-Rijnsburger AW, Blauw GJ, Lagaay AM, et al. Total cholesterol and risk of mortality in the oldest old. Lancet. 1997;350:1119–1123. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(97)04430-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lloyd-Jones D, Adams R, Carnethon M, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics—2009 update: A report from the American Heart Association Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee. Circulation. 2009;119:480–486. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.191259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDermott MM. The international pandemic of chronic cardiovascular disease. JAMA. 2007;297:1253–1255. doi: 10.1001/jama.297.11.1253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petersen S, Peto V, Rayner M, et al. European Cardiovascular Disease Statistics. London: British Heart Foundation; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Wald NJ, Simmonds M, Morris JK. Screening for future cardiovascular disease using age alone compared with multiple risk factors and age. PLoS One. 2011;6:e18742. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0018742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norheim O, Gjelsvik B, Klemsdal T, et al. Norway’s new principles for primary prevention of cardiovascular disease: Age differentiated risk thresholds. BMJ. 2011;342:d3626. [Google Scholar]

- Greving J, Visseren F, de Wit G, et al. Statin treatment for primary prevention of vascular disease: Whom to treat? Cost-effectiveness analysis. BMJ. 2011;342:d1672. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d1672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Ruijter W, Westendorp RG, Assendelft WJ, et al. Use of Framingham risk score and new biomarkers to predict cardiovascular mortality in older people: Population based observational cohort study. BMJ. 2009;338:a3083. doi: 10.1136/bmj.a3083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Splaver A, Lamas GA, Hennekens CH. Homocysteine and cardiovascular disease: Biological mechanisms, observational epidemiology, and the need for randomized trials. Am Heart J. 2004;148:34–40. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2004.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Humphrey LL, Fu R, Rogers K, et al. Homocysteine level and coronary heart disease incidence: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Mayo Clin Proc. 2008;83:1203–1212. doi: 10.4065/83.11.1203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wierzbicki AS. Homocysteine and cardiovascular disease: A review of the evidence. Diab Vasc Dis Res. 2007;4:143–150. doi: 10.3132/dvdr.2007.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mangoni AA, Woodman RJ. Homocysteine and cardiovascular risk an old foe creeps back. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;58:1034–1035. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2011.05.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veeranna V, Zalawadiya SK, Niraj A, et al. Homocysteine and reclassification of cardiovascular disease risk. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;58:1025–1033. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2011.05.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson JMG, Jungner G. Principles and Practice of Screening for Disease. Geneva: World Health Organization; 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Clarke R, Halsey J, Lewington S, et al. Effects of lowering homocysteine levels with B vitamins on cardiovascular disease, cancer, and cause-specific mortality: Meta-analysis of 8 randomized trials involving 37,485 individuals. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170:1622–1631. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2010.348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller ER, III, Juraschek S, Pastor-Barriuso R, et al. Meta-analysis of folic acid supplementation trials on risk of cardiovascular disease and risk interaction with baseline homocysteine levels. Am J Cardiol. 2010;106:517–527. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2010.03.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shepherd J, Blauw GJ, Murphy MB, et al. Pravastatin in elderly individuals at risk of vascular disease (PROSPER): A randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2002;360:1623–1630. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(02)11600-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shepherd J, Blauw GJ, Murphy MB, et al. The design of a prospective study of Pravastatin in the Elderly at Risk (PROSPER). PROSPER Study Group. PROspective Study of Pravastatin in the Elderly at Risk. Am J Cardiol. 1999;84:1192–1197. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(99)00533-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersson A, Isaksson A, Hultberg B. Homocysteine export from erythrocytes and its implication for plasma sampling. Clin Chem. 1992;38:1311–1315. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Refsum H, Smith AD, Ueland PM, et al. Facts and recommendations about total homocysteine determinations: An expert opinion. Clin Chem. 2004;50:3–32. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2003.021634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark S, Youngman LD, Sullivan J, et al. Stabilization of homocysteine in unseparated blood over several days: A solution for epidemiological studies. Clin Chem. 2003;49:518–520. doi: 10.1373/49.3.518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altman DG. Confidence intervals for the number needed to treat. BMJ. 1998;317:1309–1312. doi: 10.1136/bmj.317.7168.1309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altman DG, Andersen PK. Calculating the number needed to treat for trials where the outcome is time to an event. BMJ. 1999;319:1492–1495. doi: 10.1136/bmj.319.7223.1492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke R, Bennett DA, Parish S, et al. Homocysteine and coronary heart disease: Meta-analysis of MTHFR case-control studies, avoiding publication bias. PLoS Med. 2012;9:e1001177. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ridker PM, Shih J, Cook TJ, et al. Plasma homocysteine concentration, statin therapy, and the risk of first acute coronary events. Circulation. 2002;105:1776–1779. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emberson J, Bennett D, Link E, et al. C-reactive protein concentration and the vascular benefits of statin therapy: An analysis of 20,536 patients in the Heart Protection Study. Lancet. 2011;377:469–476. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)62174-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sattar N, Murray HM, McConnachie A, et al. C-reactive protein and prediction of coronary heart disease and global vascular events in the Prospective Study of Pravastatin in the Elderly at Risk (PROSPER) Circulation. 2007;115:981–989. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.643114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Packard CJ, Ford I, Robertson M, et al. Plasma lipoproteins and apolipoproteins as predictors of cardiovascular risk and treatment benefit in the PROspective Study of Pravastatin in the Elderly at Risk (PROSPER) Circulation. 2005;112:3058–3065. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.104.526848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ford I, Bezlyak V, Stott DJ, et al. Reduced glomerular filtration rate and its association with clinical outcome in older patients at risk of vascular events: Secondary analysis. PLoS Med. 2009;6:e16. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Homocysteine Studies Collaboration. Homocysteine and risk of ischemic heart disease and stroke: A meta-analysis. JAMA. 2002;288:2015–2022. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.16.2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duthie SJ, Whalley LJ, Collins AR, et al. Homocysteine, B vitamin status, and cognitive function in the elderly. Am J Clin Nutr. 2002;75:908–913. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/75.5.908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]