Abstract

Summary

Background

Drug-induced subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus (SCLE) has been known in the literature since 1985 and is increasingly recognized.

Objectives

To identify and describe patients with proton pump inhibitor (PPI)-induced SCLE.

Methods

A retrospective medical chart review of patients diagnosed with lupus erythematosus at the Department of Dermatology and Allergy Centre was carried out over a 19-year period. A causality assessment to PPI was performed using the Naranjo probability scale.

Results

Twenty-four patients with PPI-induced SCLE were identified (21 women and three men). Nineteen patients were newly identified cases, with a mean age of 61 years. These patients had 24 episodes of PPI-induced SCLE comprising lansoprazole (12), omeprazole (six), esomeprazole (four) and pantoprazole (two). Four patients had multiple episodes and three patients reacted to different PPIs. The incubation period was on average 8 months (range 1 week to 3·5 years) and the resolution period was on average 3 months (range 4 weeks to 8 months). Antinuclear antibodies were positive in 61% of tested patients, most frequently with a speckled pattern. Positive anti-Ro/SSA antibodies were found in 73%, anti-La/SSB antibodies in 33% and antihistone antibodies in 8% of tested patients at the time of the eruption. The skin rash was often widespread with a tendency to bullous lesions and focal skin necrosis.

Conclusions

We present the largest case series of PPI-induced SCLE reported to date, and our patient cohort reveals the lack of attention to this condition. The diagnosis may be suspected on the clinical picture, and most patients have anti-Ro/SSA antibodies, while antihistone antibodies have no value in the diagnostic process. Cross-reactivity can be seen between different PPIs.

What's already known about this topic?

Eighteen cases of proton pump inhibitor (PPI)-induced cutaneous lupus erythematosus (CLE) have been reported in the literature since 2001.

What does this study add?

Nineteen new patients with 24 episodes of PPI-induced subacute CLE (SCLE) are reported.

Cross-reactivity between different PPIs is demonstrated.

Patients with previous CLE or other autoimmune diseases may be particularly prone to PPI-induced or exacerbated SCLE.

The diagnosis is challenged by the variation in time from prescription of the culprit drug to the appearance of SCLE.

Subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus (SCLE) may be induced or aggravated by drugs. This has been known in the literature for almost 30 years, since Reed et al.1 reported five cases of SCLE induced by hydrochlorothiazide. Since then, the numbers of reported cases and inducing drugs have increased significantly. This paper contributes with additional cases of proton pump inhibitor (PPI)-induced SCLE, a field that has not yet been fully explored.

No standard diagnostic criteria for drug-induced lupus erythematosus (DILE) are defined, but it has been stated that DILE is a lupus-like syndrome temporally related to drug exposure, which resolves after discontinuation of the offending drug.2,3 DILE with predominant skin involvement includes drug-induced SCLE (DI-SCLE) and drug-induced discoid lupus erythematosus (DI-DLE).2–4 DI-DLE is a rare disorder, presenting mainly with classic discoid skin lesions in photosensitive areas and induced by fluorouracil agents and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), but some cases triggered by pantoprazole and antitumour necrosis factor-α agents have been reported.3,5 DI-SCLE is the most common form of DILE, with two major morphological variants: annular polycyclic and papulosquamous, both typically occurring on sun-exposed areas corresponding to the V-neck, back, shoulders and extensor sides of the upper extremities.2,3,6 Furthermore, a morphological variant of SCLE with targetoid (erythema multiforme-like) lesions has been described, and recognized as Rowell syndrome by some authors.4 The pathogenesis of DI-SCLE is not completely understood. A possible mechanism could be that the eliciting drug induces a photosensitivity state, followed by the induction of skin lesions via an isomorphic response in a predisposed individual.7 Furthermore, a multifaceted mechanism has been proposed with additional trigger factors such as ultraviolet radiation, photosensitizing chemicals, cigarette smoking and infections, together with an autoimmune response with elevated titres of anti-Ro/SSA autoantibodies.8 To date, more than 50 commonly used drugs have been linked to DI-SCLE.6,7,9,10 The most frequently implicated drugs are thiazide diuretics, calcium-channel blockers and terbinafine. Other provoking medications are beta blockers, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, chemotherapeutics, antihistamines, immunomodulators, antiepileptics, statins, biologics, PPIs, NSAIDs and hormone-altering drugs.3,7

Patients and methods

Study design

This was a retrospective review of medical records from patients referred to the Department of Dermatology and Allergy Centre, Odense University Hospital, Denmark, between January 1994 and October 2013. Five patients previously reported in the literature were not included.

Identifying cases

Patients with a diagnosis of lupus erythematosus were identified, according to the 10th revision of the International Classification of Diseases: M32.0, DI-SLE; M32.1, SLE with organ or system involvement; M32.2, other forms of SLE; M32.9, SLE, unspecified; L93.0, DLE (chronic CLE), lupus erythematosus not otherwise specified; L93.1, SCLE; and L93.2, other local lupus erythematosus, lupus erythematosus profundus (lupus panniculitis), lupus erythematosus tumidus. Medical records were reviewed to identify possible cases.

From July 2007, all patients diagnosed with any type of CLE seen in our department were also registered using the European Society of Cutaneous Lupus Erythematosus Core Set Questionnaire, where it was noted whether there had been any sign of DILE. A screening of incident cases to identify patients with PPI-induced CLE was performed.

Collection of data

Medical records from patients with prescribed PPIs and CLE were investigated in detail. In patients with insufficient information on medication in the medical record, the personal electronic medicine profile was consulted or the general practitioner was contacted for specific information about potential prescribed PPI. Patient sex, age at first patient contact in relation to current rash, incubation period, resolution period, previous history of cutaneous symptoms, medication history, objective signs, serology, histopathological data and treatment were registered. Ethics permission was obtained from the Danish Data Protection Agency, J.nr. 2012-41-0927.

Causality assessment

The Naranjo probability scale was used to evaluate the causal relationship between medications and skin reactions in the identified cases.11 This algorithm consists of 10 questions, answered as ‘yes’, ‘no’ or ‘do not know’, resulting in a score to each question ranging from −1 to +2. Based on the total score, the adverse drug reaction (ADR) is assigned as one of the following probability categories: definite, probable, possible or doubtful. Only patients with definite, probable or possible ADRs are included in this paper.

Results

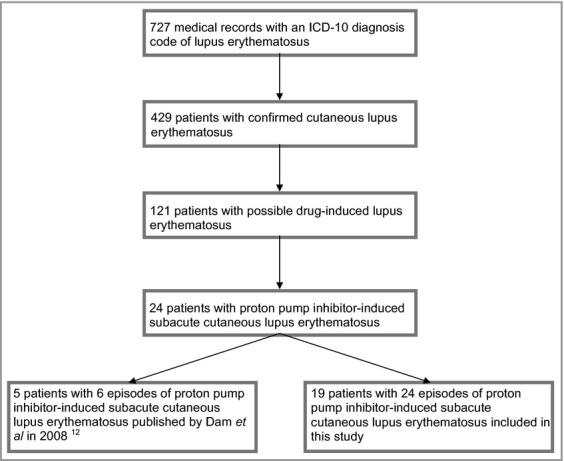

In total 727 medical records were scrutinized and 429 patients were confirmed with CLE. In 121 patients a drug was potentially inducing or aggravating lupus erythematosus, and 24 patients with a definite, probable or possible causal relationship between prescribed PPIs and CLE were identified (Fig.1). A report of five of these patients was published in 2008,12 and they were therefore not included in this study. The 19 patients represented cases of de novo PPI-induced SCLE, PPI-induced SCLE in patients with a previous history of CLE, and PPI-induced SCLE in patients with coexisting systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE). PPI-induced SCLE with targetoid lesions was also seen. The patient data are presented in Table 1, with cases listed in order of ADR probability score, with the highest probability score at the top.

Figure 1.

Recruitment of patients with proton pump inhibitor-induced subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus. ICD-10, 10th revision of the International Classification of Diseases.

Table 1.

Characteristics of 19 patients with proton pump inhibitor (PPI)-induced cutaneous lupus erythematosus (CLE)

| Patient number; sex/age (years) | Clinical data | Drug and incubation perioda | Skin biopsy | Autoantibodies | Course | Probability score | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Previous | At time of rash | After recovery | ||||||

| 1; F/63 | Systemic scleroderma since age 30 years | ANA− | Definite | |||||

| First episode: DLE | Esomeprazole 2–3 years | DLE, DIF− | ANA+ (homogeneous), histone+ | SSA+, SSB+, histone+ | CR 6 weeks after stopping esomeprazole | |||

| Second episode: SCLE (4 years later) | Pantoprazole 18 months | n.d. | Pantoprazole was stopped but the patient died 2 months later and no follow-up was performed | |||||

| 2; F/67; Fig.2a | Photosensitivity. CLE diagnosed 4 years ago, Sjögren syndrome | ANA+ (speckled), SSA+, SSB+, dsDNA− | Definite | |||||

| First episode: SCLE | Lansoprazole 8 weeks | n.d. | ANA+ (speckled), SSA+, SSB+, dsDNA−, histone− | n.d. | CR a few weeks after stopping lansoprazole | |||

| Second episode: SCLE | Lansoprazole 4–8 weeks | SCLE | CR 5 months after stopping lansoprazole | |||||

| Third episode: DLE | Lansoprazole, n.d. | n.d. | Lansoprazole has recently been withdrawn | |||||

| 3; F/30 | SLE diagnosed 8 years ago. Coeliac disease, diabetes, autoimmune thyroiditis. Six years earlier: possible exacerbation of CLE induced by lamotrigine | ANA+ (speckled), SSA+, SSB−, dsDNA−, histone− | SLE treated with prednisolone, mycophenolate mofetil and hydroxychloroquine | Definite | ||||

| First episode: SCLE | Lansoprazole 12–15 weeks | n.d. | ANA+ (speckled), SSA+, SSB+ | n.d. | CR 2 months after stopping lansoprazole | |||

| Second episode: SCLE | Omeprazole 16 weeks | One month after the episode above, omeprazole was prescribed and 4 months later the patient was referred with second SCLE. CR 6 weeks after stopping omeprazole | ||||||

| 4; F/54 | Photosensitivity. CLE diagnosed 20 years ago | n.d. | Probable | |||||

| SCLE | Lansoprazole 10 weeks | CLE, DIF+ | ANA−, SSA−, SSB−, dsDNA−, histone− | ANA−, SSA−, SSB−, dsDNA−, histone− | CR 7 months after stopping lansoprazole | |||

| 5; F/80; Fig.2b,c | Polymorphic light eruption | n.d. | Probable | |||||

| Simultaneous onset of autoimmune hepatitis and SCLE | Lansoprazole 15 months | Interphase dermatitis. CLE or EM | ANA−, SSA+, SSB−, dsDNA−, histone− | n.d. | CR 5 months after stopping lansoprazole | |||

| 6; F/86 | Photosensitivity | n.d. | Probable | |||||

| SCLE | Esomeprazole 4–8 weeks | SCLE, DIF− | ANA−, SSA+, SSB−, histone− | SSA+, SSB− | PR (a few persistent skin lesions) 5 weeks after stopping esomeprazole. She died a few months later | |||

| 7; F/62 | Arthralgias | n.d. | Probable | |||||

| SCLE | Pantoprazole 3–12 months | CLE, DIF+ | ANA+ (speckled), SSA+, SSB−, dsDNA− | ANA+ (speckled) | CR 10 weeks after stopping pantoprazole | |||

| 8; M/60; Fig.2d | Polymorphic light eruption | n.d. | Probable | |||||

| SCLE | Esomeprazole 1–2 weeks | Characteristics of both SCLE and EM | ANA+ (speckled), SSA−, SSB−, histone− | ANA+ (speckled), SSA−, SSB−, histone− | CR 8 months after stopping esomeprazole | |||

| 9; F/31 | CLE for 10 years (malar rash, chilblain lupus and SCLE). Pregnancy, lymphopenia, arthralgias | ANA+ (speckled), SSA+, SSB+, dsDNA−, histone− | Probable | |||||

| Flare in SCLE | Lansoprazole 7–8 weeks | Interphase dermatitis, suspected Rowell syndrome | ANA+ (speckled), SSA+, SSB+, dsDNA−, histone− | n.d. | CR 8 weeks after stopping lansoprazole | |||

| 10; F/28 | SLE for 12 years | ANA+ (speckled), SSA+, dsDNA+, histone+ | Probable | |||||

| First episode: SCLE | Omeprazole 1 year | Atypical CLE or EM | ANA+ (speckled), dsDNA+ | ANA+ (speckled), dsDNA− | PR after 1 month of treatment with hydroxychloroquine | |||

| Second episode: SCLE | Lansoprazole 3–4 months | Changed omeprazole to lansoprazole after 1 month and had a flare of CLE. CR after kidney transplantation and immunosuppressive therapy | ||||||

| 11; F/68 | Photosensitivity. DLE 4 years ago | n.d. | ||||||

| SCLE | Lansoprazole 6 weeks | SCLE, DIF+ | ANA+ (nucleoli), SSA+, SSB+, dsDNA−, histone− | ANA+ (nucleoli) | CR 12 weeks after stopping lansoprazole | Probable | ||

| 12; F/57 | Photosensitivity. DLE diagnosed 22 years ago with a fluctuating course and flare-up in summer periods | ANA+ (nucleoli), dsDNA− | ||||||

| SCLE in winter period | Esomeprazole 2–3 months | SCLE | ANA+ (nucleoli), SSA+, SSB−, histone− | ANA+ (nucleoli), dsDNA− | CR 10 weeks after stopping esomeprazole | Probable | ||

| 13; F/65 | Photosensitivity. SCLE diagnosed 10 years ago, one flare after terbinafine. Sjögren syndrome | ANA−, SSA+, SSB−, histone− | Probable | |||||

| SCLE | Lansoprazole 3–4 months | SCLE, DIF− | ANA−, SSA+, SSB−, dsDNA−, histone− | n.d. | CR 6 weeks after stopping lansoprazole | |||

| 14; F/66 | SLE diagnosed 10 months ago | ANA+, dsDNA+ | Probable | |||||

| SCLE | Omeprazole 1–2 weeks | SCLE, DIF+ | n.d. | n.d. | CR 5 months after stopping omeprazole | |||

| 15; F/71 | Photosensitivity | n.d. | Probable | |||||

| SCLE | Omeprazole 2 years | SCLE, DIF− | ANA−, SSA−, SSB−, dsDNA−, histone− | n.d. | CR 2 months after stopping omeprazole | |||

| 16; F/68 | Rheumatoid arthritis | ANA− | Probable | |||||

| SCLE | Omeprazole 3·5 years | SCLE, DIF− | ANA−, dsDNA− | n.d. | CR 4 weeks after stopping omeprazole | |||

| 17; F/63 | Rheumatoid arthritis | Probable | ||||||

| SCLE | Omeprazole 3 months | CLE, DIF− | n.d. | ANA−, SSA+, SSB−, dsDNA− | n.d. | CR 4 weeks after stopping omeprazole | ||

| 18; M/78 | Earlier episode of EM induced by systemic terbinafine | ANA+ (speckled), dsDNA− | Possible | |||||

| SCLE | Lansoprazole 1–2 weeks | SCLE, DIF− | ANA+ (speckled), SSA+, SSB+, histone− | n.d. | PPI was continued up to death a few months later | |||

| 19; F/73 | Photosensitivity. Antiphospholipid syndrome. SCLE diagnosed 1 year ago, possibly induced by esomeprazole. Arthralgias | ANA−, dsDNA− | Possible | |||||

| SCLE | Lansoprazole 8–10 months | SCLE, DIF− | ANA+ (speckled), SSA−, SSB−, dsDNA−, histone−, cardiolipin+ | n.d. | Persistent active skin lesions after 2 years with ongoing lansoprazole treatment | |||

ANA, antinuclear antibodies; cardiolipin, anticardiolipin antibodies; CR, complete remission; DIF, direct immunofluorescence; DLE, discoid lupus erythematosus; dsDNA, antibodies to double-stranded DNA; EM, erythema multiforme; histone, antihistone antibodies; n.d., not determined; PR, partial remission; SCLE, subacute CLE; SLE, systemic lupus erythematosus; SSA, anti-Ro/SSA antibodies; SSB, anti-La/SSB antibodies.

Incubation period is the delay from prescription of PPI to onset of rash.

Example 1: lansoprazole-induced de novo subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus

An 80-year-old woman (patient number 5) had a 10-year tendency to sun-induced rash on her arms, diagnosed as polymorphic light eruption. Fifteen months after the prescription of lansoprazole, she presented with a red, itchy rash on her face and trunk. Almost at the same time she was diagnosed with an autoimmune hepatitis and was started on prednisolone 30 mg daily, which also attenuated the skin symptoms. Decreasing the prednisolone dose resulted in severe flare of the rash and the patient was referred to our department. She presented with an annular, polycyclic and erythematous rash of her face and upper trunk, with confluent lesions between her shoulder blades (Fig.2b,c), clinically compatible with SCLE. Serological testing showed positive anti-Ro/SSA antibodies, whereas antinuclear antibodies (ANA), anti-La/SSB antibodies, antibodies to double-stranded (ds)DNA and antihistone antibodies were all negative. A biopsy from affected skin was dominated by epithelial necrosis and interphase dermatitis. Direct immunofluorescence (DIF) was not performed. DI-SCLE was suspected and lansoprazole was discontinued. Complete clinical remission was obtained 5 months after discontinuation of lansoprazole.

Figure 2.

Illustrations of three patients with proton pump inhibitor-induced subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus. (a) Papulosquamous subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus in patient number 2; (b,c) annular and polycyclic subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus in patient number 5; and (d) targetoid lesions in patient number 8.

Example 2: esomeprazole-induced subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus with targetoid lesions

A 60-year-old man (patient number 8), with no previous history of skin symptoms, developed a polymorphic light eruption on the chest in relation to a vacation with massive sun exposure. He was then prescribed esomeprazole because of reflux symptoms, and after 1–2 weeks a severe flare of the rash emerged, causing discontinuation of esomeprazole and referral to our department. He had a symmetrical widespread targetoid rash on the face, trunk and proximal parts of the extremities. He also had numerous bullous skin lesions on the chest and a positive Nikolsky sign (Fig.2d). Histologically the lesions showed signs of both SCLE and erythema multiforme. Blood tests showed positive ANA with a speckled pattern, and negative IgM rheumatoid factor, anti-Ro/SSA, anti-La/SSB and antihistone antibodies. The patient was treated with potassium permanganate baths, topical corticosteroids and systemic prednisolone. After 6 weeks he was in remission and at the final follow-up visit 8 months after discontinuation of esomeprazole, he was in complete remission and therapy could be stopped.

Example 3: lansoprazole-induced subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus in a patient with previous discoid lupus erythematosus

A 68-year-old woman (patient number 11) was diagnosed with DLE and went into remission. Six weeks after prescription of lansoprazole, a violaceous papulosquamous rash appeared on the neck, upper extremities, trunk and buttocks, partially with crusting but no visible bullae. Blood tests showed positive ANA with nucleoli pattern, anti-Ro/SSA antibodies and anti-La/SSB antibodies, whereas antibodies to dsDNA and histone were negative. A skin biopsy was diagnostic of SCLE. DIF showed focal granular deposition of IgG at the basement membrane zone and a dot-like fluorescence in epidermal keratinocytes. DI-SCLE was suspected and lansoprazole was discontinued. Treatment included topical corticosteroids, potassium permanganate baths and hydroxychloroquine. Complete clinical remission was obtained after 12 weeks when all treatments were stopped.

Example 4: omeprazole-induced subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus in a patient with systemic lupus erythematosus

A 66-year-old woman (patient number 14) was diagnosed with SLE (malar rash, polyarthritis, haemolysis, lymphopenia, central nervous system involvement, ANA+, dsDNA+) 10 months previously and had a secondary Sjögren syndrome. Omeprazole was prescribed and after 1–2 weeks a rash emerged with scaly erythematous and annular lesions on the back, shoulders and in the V-neck area, and more scattered on the legs. A skin biopsy showed SCLE with positive DIF; no serological measurements were performed in relation to the rash. SCLE was treated with topical corticosteroids and prednisolone. Later DI-SCLE was suspected and omeprazole was discontinued. Five months later complete clinical remission of SCLE lesions was achieved.

Characteristics of the included cases

In 19 patients an association between prescribed PPI and SCLE was identified with a definite (three cases), probable (14 cases) or possible (two cases) causal relationship, distributed among 17 women (89%) and two men. The mean age at the initial visit was 61 years (range 28–86). Cases with coexisting SLE and PPI-induced SCLE were younger, with a mean age of 41 years (range 28–66). Twenty-four episodes of PPI-induced CLE were identified, comprising lansoprazole in 12 cases, omeprazole in six cases, esomeprazole in four cases and pantoprazole in two cases. The incubation period (delay from prescription of PPI to onset of rash) averaged 8 months (range 1 week to 3·5 years, median 12–15 weeks), and the resolution period (time for clinical remission) averaged 3 months (range 4 weeks to 8 months, median 2 months) after discontinuation of the inciting PPI. Positive DIF was demonstrated in four of the 12 biopsies in which DIF had been performed. In 18 patients a blood test was screened for ANA at the time of the rash, showing positive ANA in 11 cases (61%), with speckled pattern in eight cases, homogeneous pattern in one case and nucleoli antibodies in two cases. Positive anti-Ro/SSA antibodies were found in 11/15 patients (73%), anti-La/SSB antibodies in five of 15 (33%), antibodies to dsDNA in one of 12 (8%) and antihistone antibodies in one of 13 tested patients (8%) at the time of the rash.

Discussion

PPIs are among the most frequently prescribed drugs in the world, and in 2010 approximately 9% of the Danish population redeemed at least one prescription for a PPI.13,14 Indications for prescribing PPIs are eradication of Helicobacter pylori, peptic ulcer disease, anastomotic ulcer after gastric resection, gastro-oesophageal reflux disease and Zollinger–Ellison syndrome. PPIs are generally well tolerated, but different adverse skin reactions can occur, such as dermatitis, lichen planus, urticaria, angio-oedema, toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN) and CLE.9,13

A literature review of PPI-induced CLE using the PubMed online database identified 18 case reports of PPI-induced SCLE and one case of PPI-induced DLE.5,12,15–23 However, the latter case did not fulfil the proposed definition of DILE, as the discoid lesions occurred after discontinuation of pantoprazole. In a Swedish case–control study of 234 patients with SCLE, 65 had received PPIs.10 A significant odds ratio of 2·9 for prescription of PPIs in the 6 months preceding a diagnosis of SCLE was reported.

In this study 19 patients with a causal relationship between prescribed PPIs and SCLE, seen in our department between January 1994 and October 2013, are presented. A further five patients were identified and a report published in 2008.12 The clinical and biochemical characteristics of the patients in this study in terms of age, sex, ANA, anti-Ro/SSA antibodies and anti-La/SSB antibodies were rather similar to the previously published data for DI-SCLE. However, we identified antihistone antibodies in only one of our patients (8%), who was known to have SLE, which is less than the 33% reported in a systematic literature review of DI-SCLE published in 2011.7 Antihistone antibodies are more important when diagnosing cases of DI-SLE, where these autoantibodies are present in up to 95% of cases.2 The incubation period in our patient cohort was on average 8 months and ranged from 1 week to 3·5 years, with a median of 12–15 weeks. This can be compared with data from the systematic review, which reported that the incubation period of DI-SCLE ranged from 3 days to 11 years (average 27·9 weeks, median 6 weeks). The resolution period in our patient cohort was on average 3 months and ranged from 4 weeks to 8 months, with a median of 2 months; this is compared with 1–32 weeks (mean 7·3 weeks, median 4 weeks) in the systematic literature review. Four of our patients had negative ANA screening but positive anti-Ro/SSA antibodies when they presented with DI-SCLE. This result emphasizes the importance of measuring specific anti-Ro/SSA antibodies.

Four of our patients had multiple episodes of PPI-induced SCLE, and three patients experienced multiple episodes induced by different PPIs. These findings support a possible class effect, meaning that an identical feature in different PPIs is responsible for the induction of SCLE. If a patient has once developed PPI-induced CLE, all PPIs should be avoided in future or prescribed only if clearly indicated. We think that all patients with earlier CLE, known photosensitivity and possibly also autoimmune diseases in general, especially Sjögren syndrome, may be prone to develop DI-SCLE.

In the systematic review it was concluded that DI-SCLE does not differ clinically, histopathologically or immunologically from idiopathic SCLE.7 However, other authors have emphasized the more disseminated cutaneous manifestations in patients with DI-SCLE, as well as the frequent occurrence of malar rash and bullous, targetoid and vasculitic manifestations.2,4,24 We also found DI-SCLE to be more widespread and inflammatory, and not uncommonly accompanied by bullous lesions and/or skin necrosis. However, no pathognomonic paraclinical or clinical features can with certainty distinguish DI-SCLE from idiopathic SCLE at the moment, and therefore it is important to have a high level of suspicion of drug effects.

A register of reported side-effects to drugs, managed by The Danish Health and Medicines Authority, currently includes seven cases of CLE as adverse reactions to PPIs, along with two cases due to esomeprazole, two cases due to lansoprazole, one case due to omeprazole and two cases due to pantoprazole.25 Four cases of PPI-induced SLE and one case of lupus-like syndrome were also recognized in the database between 1 January 1989 and 23 August 2013. Omeprazole was launched on the Danish market in 1989, lansoprazole in 1994, pantoprazole in 1995 and esomeprazole in 2000. In total 236 cutaneous side-effects to PPIs have been reported, and we wonder whether some of these could have been unrecognized cases of DI-SCLE.

The applied Naranjo probability scale is not optimal to estimate the likelihood of PPI-induced CLE, but there is still no universally accepted method for causality assessment of adverse drug reactions.26 To achieve a definite designation a re-exposure to the culprit drug must take place. However, we do not rechallenge this group of patients, as it is not ethically justifiable to introduce a re-exposure when a probable causal relationship is known. Also, life-threatening cases of TEN-like acute CLE can be a risk, especially in patients with SLE.27 Similarly, it is unlikely that a repeated exposure will always lead to the same response in a given patient, as other trigger factors and the current status of the immune system are important for the induction of CLE. Therefore, in patients with a known causal relationship between PPIs and CLE, a re-exposure will occur only in case of unintended prescription of a PPI. Re-exposure of the same or another PPI was seen in four of our patients and in several other cases in the literature, emphasizing that patients should receive oral and written information and a warning should be made in the medical record to avoid accidental re-exposure.

We think that a diagnosis of DI-SCLE can be suspected on the clinical features combined with a relevant drug history, and it can be supported by histopathology and anti-Ro/SSA antibodies, while antihistone antibodies have no value in this regard. The diagnostic process is challenged by the variation in delay from prescription of the culprit drug to the appearance of DI-SCLE. This aspect is known from other kinds of adverse drug reactions, e.g. angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor-induced angio-oedema, which may also tend to be overlooked.28 Physicians should not avoid prescribing PPIs when clear indications for treatment are present, but we hope that this paper will lead to a more thoughtful prescription in patients with current or previous CLE, as well as SLE. In daily clinic it is important to screen the medication list in patients with de novo or exacerbated SCLE and to suspect SCLE in patients with a skin eruption developing after the introduction of PPIs. The clinical advantage of identifying DI-SCLE is obvious due to the reversible nature of this condition. This is beneficial in socioeconomic terms, and especially for the individual patient, who could otherwise risk treatment with potentially harmful systemic immunosuppressive drugs for a presumed idiopathic CLE, or a flare in already known CLE. When the triggering drugs are stopped, spontaneous resolution will be achieved within a few months in most cases, with no or minimal symptomatic therapy such as topical corticosteroids or additional antimalarials.

References

- 1.Reed BR, Huff JC, Jones SK, et al. Subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus associated with hydrochlorothiazide therapy. Ann Intern Med. 1985;103:49–51. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-103-1-49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Marzano AV, Vezzoli P, Crosti C. Drug-induced lupus: an update on its dermatologic aspects. Lupus. 2009;18:935–40. doi: 10.1177/0961203309106176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vedove CD, Simon JC, Girolomoni G. Drug-induced lupus erythematosus with emphasis on skin manifestations and the role of anti-TNFα agents. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2012;10:889–97. doi: 10.1111/j.1610-0387.2012.08000.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Marzano AV, Lazzari R, Polloni I, et al. Drug-induced subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus: evidence for differences from its idiopathic counterpart. Br J Dermatol. 2011;165:335–41. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2011.10397.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Correia O, Lomba Viana H, Azevedo R, et al. Possible phototoxicity with subsequent progression to discoid lupus following pantoprazole administration. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2001;26:455–6. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2230.2001.00857.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Callen JP. Drug-induced subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus. Lupus. 2010;19:1107–11. doi: 10.1177/0961203310370349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lowe G, Henderson CL, Grau RH, et al. A systematic review of drug-induced subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus. Br J Dermatol. 2011;164:465–72. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2010.10110.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zandman-Goddard G, Solomon M, Rosman Z, et al. Environment and lupus-related diseases. Lupus. 2012;21:241–50. doi: 10.1177/0961203311426568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Litt's Drug Eruption Reference Manual Database. Available at: http://www.drugeruptiondata.com (last accessed 10 December 2013)

- 10.Grönhagen CM, Fored CM, Linder M, et al. Subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus and its association with drugs: a population-based matched case–control study of 234 patients in Sweden. Br J Dermatol. 2012;167:296–305. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2012.10969.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Naranjo CA, Busto U, Sellers EM, et al. A method for estimating the probability of adverse drug reactions. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1981;30:239–45. doi: 10.1038/clpt.1981.154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dam C, Bygum A. Subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus induced or exacerbated by proton pump inhibitors. Acta Derm Venereol. 2008;88:87–9. doi: 10.2340/00015555-0335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chang YS. Hypersensitivity reactions to proton pump inhibitors. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012;12:348–53. doi: 10.1097/ACI.0b013e328355b8d3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Reimer C, Bytzer P. [Adverse events associated with long-term use of proton pump inhibitors] Ugeskr Laeger. 2012;174:2289–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bracke A, Nijsten T, Vandermaesen J, et al. Lansoprazole-induced subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus: two cases. Acta Derm Venereol. 2005;85:353–4. doi: 10.1080/00015550510026668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Popovic K, Wahren-Herlenius M, Nyberg F. Clinical follow-up of 102 anti-Ro/SSA-positive patients with dermatological manifestations. Acta Derm Venereol. 2008;88:370–5. doi: 10.2340/00015555-0473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Panting KJ, Pinto M, Ellison J. Lansoprazole-induced subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2009;34:733–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2230.2008.03105.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mankia SK, Rytina E, Burrows NP. Omeprazole-induced subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2010;35:e1–2. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2230.2008.03125.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McCourt C, Somerville J, McKenna K. Anti-Ro and anti-La antibody positive subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus (SCLE) induced by lansoprazole. Eur J Dermatol. 2010;20:860–1. doi: 10.1684/ejd.2010.1112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Toms-Whittle LM, John LH, Buckley DA. Drug-induced subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus associated with omeprazole. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2011;36:281–3. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2230.2010.03926.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Alcántara-González J, Truchuelo-Díez MT, González-García C, Jaén Olasolo P. Esomeprazole-induced subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2011;102:638–40. doi: 10.1016/j.ad.2010.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wee JS, Natkunarajah J, Marsden RA. A difficult diagnosis: drug-induced subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus (SCLE) triggered by omeprazole in a patient with pre-existing idiopathic SCLE. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2012;37:445–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2230.2011.04245.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Almebayadh M, Regnier-Rosencher E, Carlotti A, et al. Subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus induced and exacerbated by proton pump inhibitors. Dermatology. 2013;226:119–23. doi: 10.1159/000346694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bonsmann G, Schiller M, Luger TA, Ständer S. Terbinafine-induced subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;44:925–31. doi: 10.1067/mjd.2001.114565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Danish Health and Medicines Authority. Drug Analysis Prints: reported adverse reactions. Available at: http://laegemiddelstyrelsen.dk/da/topics/bivirkninger-og-forsoeg/bivirkninger/drug analy-sis-prints-indberettede-bivirkninger (last accessed 10 December 2013)

- 26.Agbabiaka TB, Savović J, Ernst E. Methods for causality assessment of adverse drug reactions: a systematic review. Drug Saf. 2008;31:21–37. doi: 10.2165/00002018-200831010-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ting W, Stone MS, Racila D, et al. Toxic epidermal necrolysis-like acute cutaneous lupus erythematosus and the spectrum of the acute syndrome of apoptotic pan-epidermolysis (ASAP): a case report, concept review and proposal for new classification of lupus erythematosus vesiculobullous skin lesions. Lupus. 2004;13:941–50. doi: 10.1191/0961203304lu2037sa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rasmussen ER, Mey K, Bygum A. Angiotensin-converting enzyme-induced angioedema – a dangerous new epidemic. Acta Derm Venereol. 2014 doi: 10.2340/00015555-1760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]