Abstract

Summary

Background

Oral liarozole, a retinoic acid metabolism-blocking agent, may be an alternative to systemic retinoid therapy in patients with lamellar ichthyosis.

Objective

To demonstrate the efficacy and safety of once-daily oral liarozole in the treatment of moderate/severe lamellar ichthyosis.

Methods

This was a double-blind, multinational, parallel phase II/III trial (NCT00282724). Patients aged ≥ 14 years with moderate/severe lamellar ichthyosis [Investigator's Global Assessment (IGA) score ≥ 3] were randomized 3 : 3 : 1 to receive oral liarozole (75 or 150 mg) or placebo once daily for 12 weeks. Assessments included: IGA; a five-point scale for erythema, scaling and pruritus severity; Short Form-36 health survey; Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI); and safety parameters. The primary efficacy variable was response rate at week 12 (responder: ≥ 2-point decrease in IGA from baseline).

Results

Sixty-four patients were enrolled. At week 12, 11/27 (41%; liarozole 75 mg), 14/28 (50%; liarozole 150 mg) and one out of nine (11%; placebo) patients were responders; the difference between groups (liarozole 150 mg vs. placebo) was not significant (P = 0·056). Mean IGA and scaling scores decreased from baseline in both liarozole groups at weeks 8 and 12 vs. placebo; erythema and pruritus scores were similar between treatment groups. Improvement in DLQI score was observed in both liarozole groups. Treatment with liarozole for 12 weeks was well tolerated.

Conclusions

The primary efficacy variable did not reach statistical significance, possibly owing to the small sample size following premature termination. However, once-daily oral liarozole, 75 and 150 mg, improved scaling and DLQI and was well tolerated in patients with moderate/severe lamellar ichthyosis.

What's already known about this topic?

Oral liarozole, a retinoic acid metabolism-blocking agent, may be an alternative to systemic retinoid therapy for patients with lamellar ichthyosis.

What does this study add?

While the primary endpoint was not met, compared with placebo, once-daily oral liarozole, 75 or 150 mg, decreased overall severity and scaling, but not erythema and pruritus, and improved Dermatology Life Quality Index in patients with lamellar ichthyosis.

Oral liarozole was well tolerated.

Ichthyoses comprise a large, heterogeneous group of inherited skin disorders resulting from an abnormality of the keratinization process.1,2 Lamellar ichthyosis, a member of the nonsyndromic autosomal recessive congenital ichthyosis group of ichthyoses, has an incidence of 1 : 100 000–300 000 live births.2–4 Patients with lamellar ichthyosis typically have severe generalized hyperkeratosis and dry, scaly skin across the entire body. The disorder may be associated with decreased quality of life (QoL).5,6

Treatment options for lamellar ichthyosis include mechanical scale removal, hydrating and lubricating creams or ointments, and topical keratolytic agents.2 Patients who do not respond adequately to topical agents may be treated with oral retinoids; however, dose-limiting side-effects, including mucocutaneous side-effects, increased serum triglycerides and liver enzymes, and potentially long-lasting teratogenic effects are major constraints of their use.2,7 Women are advised to delay pregnancy for a minimum of 2 years (Europe) or 3 years (U.S.A.) following therapy with acitretin.7,8

Liarozole, a retinoic acid (RA) metabolism-blocking agent (RAMBA) in clinical development, has been granted orphan drug designation for congenital ichthyosis by the European Commission and the U.S. Food and Drug Administration;9,10 such designation is not a judgement on drug effectiveness or safety. RAMBAs inhibit the CYP26-dependent 4-hydroxylation of all-trans-RA, which results in an increased concentration of endogenous all-trans-RA in tissues expressing CYP26, such as the skin.11 Azole RAMBAs, such as liarozole, and the more potent CYP26-specific compound talarozole, are expected to have less systemic toxicity than oral retinoids as they do not require high systemic exposure to RA to achieve therapeutic effects; furthermore, a long-term risk of teratogenic effects is not expected with RAMBAs, as they are quickly eliminated and all-trans-RA levels return to baseline levels within 24 h of treatment discontinuation.11 Previous studies observed clinical improvements in patients with ichthyosis receiving twice-daily oral liarozole, 75 and 150 mg, for 12 weeks.12,13 In the comparative study, liarozole was equally as effective as acitretin and showed a trend towards a more favourable tolerability profile.13 The objective of this study was to demonstrate the efficacy and safety of once-daily oral liarozole, 75 or 150 mg, vs. placebo in the treatment of patients with moderate/severe lamellar ichthyosis.

Methods

Study design

This was a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel phase II/III trial to evaluate the efficacy and safety of two once-daily doses of oral liarozole (75 and 150 mg) in the treatment of patients with moderate/severe lamellar ichthyosis (NCT00282724). The study was performed in accordance with Good Clinical Practice (ICH/CPMP/135/95) and the guiding principles of the Declaration of Helsinki,14 and had institutional review board approval from each participating centre. Patients were recruited from 16 treatment centres in nine countries between January 2006 and April 2007. Important study amendments included premature termination of the trial owing to slow recruitment and change of primary efficacy variable to response based on Investigator's Global Assessment (IGA) instead of overall scaling score.

Patients

Eligible patients were aged ≥ 14 years (Canada, Dominican Republic, France and Sweden) or ≥ 18 years (Belgium, Germany, Italy, the Netherlands and Norway) and had lamellar ichthyosis with an IGA score ≥ 3 (moderate to severe) at screening and baseline, a body weight ≥ 45 kg and otherwise good general health, and were free from any disease that could impair the evaluation of ichthyosis. Women of childbearing potential were required to use hormonal and barrier contraception during, and for 1 month after, the treatment period, and required a negative pregnancy test at screening and baseline. Exclusion criteria included: inflammatory skin disease unrelated to ichthyosis; use of topical (except emollient) or ultraviolet treatment for ichthyosis ≤ 2 weeks (≤ 4 weeks in Sweden) prior to baseline; use of systemic therapy for ichthyosis or vitamin A supplements ≤ 4 weeks prior to baseline; use of drugs metabolized by the CYP450 system during the treatment period; use of immunosuppressive drugs, including topical or systemic corticosteroids; retinoid hypersensitivity; significant hepatic, renal or immune disease, osteoporosis, or history of adrenal cortex dysfunction; heart disorders requiring treatment, myocardial infarction in the previous 24 weeks, or a history of heart failure/cardiac arrhythmia.

Interventions

Patients attended up to six study visits over 18–20 weeks (screening, baseline, weeks 4, 8 and 12, follow-up). At the screening visit, patients provided written informed consent, demographic characteristics and medical history, and were evaluated against the inclusion/exclusion criteria. Patients then entered a 2- to 4-week washout period to confirm ichthyosis severity before randomization.

At baseline, patients were re-evaluated against inclusion/exclusion criteria. Eligible patients were randomized 3 : 3 : 1 to receive once-daily liarozole 75 mg (one liarozole 75-mg tablet and one placebo tablet), liarozole 150 mg (two liarozole 75-mg tablets), or placebo (two placebo tablets) for 12 weeks using dynamic minimization to ensure balanced treatment groups within centres. Randomization was weighted towards the liarozole treatment groups owing to ichthyosis severity in patients requiring systemic treatment. Liarozole and placebo tablets (provided by Barrier Therapeutics, Geel, Belgium) were identical in appearance and packaging. Following the treatment period, patients entered a 4-week follow-up period and attended a study visit at week 16. Patients could continue mechanical scale removal and use of emollients except ≤ 12 h preceding a study visit.

Assessments

At all study visits, patients provided medication usage, underwent a physical examination and vital signs measurements, and provided blood and urine samples for clinical laboratory analyses. Patients completed a daily diary for 7 days prior to each study visit (except screening), noting concomitant medications, emollient use and mechanical scale removal.

Lamellar ichthyosis was assessed at all study visits using the IGA (5-point scale: 0, clear; 1, almost clear; 2, mild; 3, moderate; 4, severe); erythema, scaling and pruritus on the legs, trunk, palms and scalp were evaluated as marker areas on a 5-point scale (0, none; 1, mild; 2, moderate; 3, severe; 4, very severe), and an overall scaling score was calculated; individual scaling scores for each marker area were weighted (4 × score for legs + 3 × score for trunk + 1 × score for palms + 1 × score for scalp) and summed (minimum summed score, 0; maximum summed score, 36). Efficacy assessments for each individual patient were performed by the same investigator throughout the trial, or by a subinvestigator familiar with the study and subject.

Quality of life was assessed at all study visits except week 8 using the acute (1-week) recall version of the Short Form (SF)-36 health survey,15 a 36-item questionnaire with eight domains (higher scores indicate better QoL) and the Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI),16,17 a 10-item questionnaire with six domains (higher scores indicate poorer QoL).

Ophthalmological examinations (slit-lamp inspection for corneal opacity, Schirmer's tear test and fluorescein staining for corneal damage) and electrocardiographic (ECG) examinations were performed between screening and baseline, at week 4 (ECG; Germany only) and week 12. ECG examinations and clinical laboratory analyses were performed at follow-up if previous assessment revealed clinically relevant abnormalities. Concentrations of bone markers in serum [osteocalcin, intact procollagen type I N-terminal propeptide (PINP) and C-terminal cross-linking telopeptide of type I collagen (CTX)] and urine [N-terminal cross-linking telopeptide of type I collagen (NTX)] were assessed at baseline, weeks 4 and 12, and follow-up. Adverse events (AEs) were recorded and mucocutaneous symptoms possibly related to RA (cheilitis, epistaxis, hair loss) graded for severity on a 5-point Likert scale from 0 (absent) to 4 (very severe) at baseline, weeks 4, 8 and 12, and follow-up. A composite score for mucocutaneous symptoms was calculated as the sum of the severity grades. Plasma liarozole concentration was assessed prior to dosing at baseline and week 8; predose and 1–2 h postdose at weeks 4 and 12. Photographs of the two most severely affected body areas at screening were taken at all study visits.

Analysis populations

The intent-to-treat (ITT) population included all patients who received one or more doses of study medication and had postbaseline efficacy data. The safety population included all patients who were randomized into the study.

Study end variables

The primary efficacy variable was response rate at week 12. A patient was a responder if their IGA score decreased by ≥ 2 points from baseline. Secondary end variables were: IGA score at week 8; change from baseline in overall scaling score at weeks 8 and 12; change from baseline in severity scores for erythema and pruritus at weeks 8 and 12; SF-36 and DLQI scores; use of emollients and mechanical scale removal; safety and tolerability; and plasma liarozole concentration.

Sample size and statistical methods

A total of 98 patients were planned for enrolment to provide 90% power to detect a difference between a response rate of 0·20 (placebo group) and 0·75 (liarozole groups) and to accommodate a drop-out rate of 15%. Data from all centres were combined for analyses.

For the primary efficacy analysis (ITT population), the 150-mg liarozole group was compared with the placebo group; if a significant difference was observed, the 75-mg liarozole group was tested against the placebo group. If IGA evaluation at week 12 was missing, last observation carried forward was used. The number of responders in each liarozole group was compared with those in the placebo group using Fisher's exact test. IGA and overall erythema, scaling and pruritus scores at weeks 8 and 12 were compared between liarozole and placebo groups using the Wilcoxon–Mann–Whitney rank sum test, provided the analysis of the primary efficacy variable showed a significant result for that dosage group. Changes from baseline in QoL scores were compared between each of the liarozole groups and the placebo group using analysis of covariance (ancova); covariates included sex, age and baseline value.

The proportion of patients reporting one or more AEs was compared between the liarozole and the placebo groups using Fisher's exact test. Changes from baseline in vital signs were evaluated within each group using paired t-tests and vs. the placebo group using unpaired t-tests. Mucocutaneous symptoms were evaluated using the Wilcoxon signed rank test within each group and compared with placebo using the Wilcoxon–Mann–Whitney rank sum test. For bone markers, changes from baseline in treatment groups were compared using an ancova model; within-group changes from baseline were assessed with a paired t-test. All statistical analyses were performed using SAS software version 8.02 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, U.S.A.) and significance set as P < 0·05.

Results

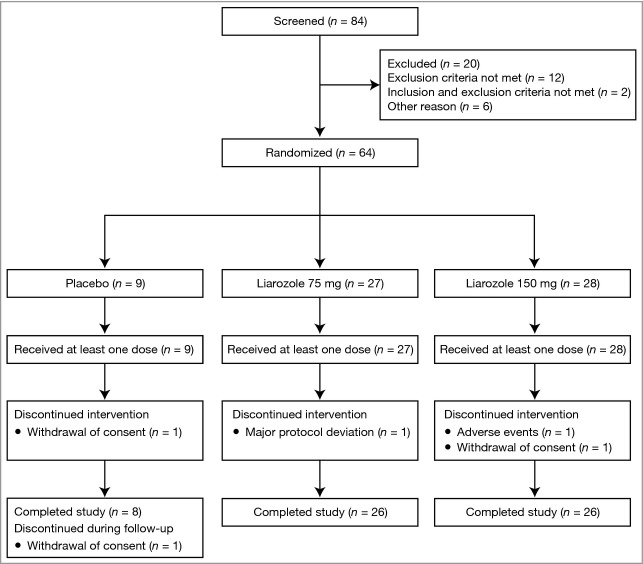

A total of 84 patients were screened; 64 patients were randomized and included in the safety and ITT populations (Fig.1). Baseline demographics were similar between treatment groups (Table 1). Patients were aged 17–70 years, predominantly white (81%; 52/64) and 52% (33/64) were male. No significant differences between treatment groups were observed for baseline bone markers. One patient (75-mg liarozole group) was taking prohibited medication at baseline (budesonide and salmeterol xinafoate aerosols for asthma).

Figure 1.

Patient flow diagram.

Table 1.

Baseline demographics and characteristics (intent-to-treat and safety population)

| Characteristic | Placebo (n = 9) | Liarozole 75 mg (n = 27) | Liarozole 150 mg (n = 28) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years), mean (SD), range | 36 (14), 19–59 | 40 (14), 18–65 | 36 (15), 17–70 |

| Sex, n (%) | |||

| Male | 5 (56) | 14 (52) | 14 (50) |

| Race, n (%) | |||

| Moroccan | – | – | 1 (4) |

| Hispanic | – | 4 (15) | 5 (18) |

| White | 8 (89) | 22 (81) | 22 (79) |

| Black | 1 (11) | 1 (4) | – |

| Height (cm), mean (SD), range | 166 (15), 137–183 | 166 (17), 132–196 | 165 (17), 130–196 |

| Weight (kg), mean (SD), range | 73 (21), 55–122 | 73 (19), 35–116 | 70 (15), 52–109 |

| Body mass index (kg m−2), mean (SD), range | 26·4 (6·8), 18·2–36·6 | 26·5 (4·9), 15·6–36·9 | 25·9 (5·4), 18·0–40·0 |

| IGA score, mean (SD), range | 3·4 (0·5), 3–4 | 3·6 (0·5), 3–4 | 3·5 (0·5), 3–4 |

| Scaling score, mean (SD), range | 26·8 (6·7), 13–34 | 27·9 (5·7), 15–36 | 28·8 (6·2), 17–36 |

| Erythema score, mean (SD), range | 13·7 (9·2), 3–28 | 15·9 (9·6), 0–36 | 14·9 (8·9), 0–36 |

| Pruritus score, mean (SD), range | 13·3 (10·2), 0–32 | 14·7 (11·0), 0–34 | 14·2 (9·0), 0–33 |

| Total symptoms score, mean (SD), range | 53·8 (18·7), 26–85 | 58·5 (19·3), 27–104 | 57·9 (16·4), 20–95 |

| Mechanical scale removal (proportion of days used during week before baseline),a mean (SD) | 0·63 (0·42) | 0·47 (0·42) | 0·59 (0·37) |

| Use of emollients during week before baseline (average score),a mean (SD) | 1·68 (0·54) | 1·43 (0·54) | 1·32 (0·51) |

| QoL scores, mean (SD) | |||

| SF-36 standardized physical component scale | 50·8 (7·9) | 49·6 (7·0) | 50·9 (5·7) |

| SF-36 standardized mental component scale | 41·4 (10·1) | 47·5 (10·2) | 46·0 (9·3) |

| DLQI | 13·7 (6·7) | 9·4 (6·7) | 7·3 (4·1)b |

| Mucocutaneous symptoms (composite score),c mean (SD) | 0·0 (0·00) | 0·36 (0·81)d | 0·82 (1·31) |

| Ophthalmological abnormalities, n (%) | 3 (33) | 14 (52) | 15 (54) |

DLQI, Dermatology Life Quality Index; IGA, Investigator's Global Assessment; QoL, quality of life; SF-36, Short Form-36 health survey.

For 7 days prior to the baseline visit (and subsequent study visits), patients completed a daily diary, noting the use of emollients (none, a little or much) and mechanical scale removal (yes or no);

n = 27;

sum of severity scores for cheilitis, epistaxis and hair loss, each graded on a 5-point scale from 0 (absent) to 4 (very severe), maximum composite score = 12;

n = 25.

Primary efficacy variable

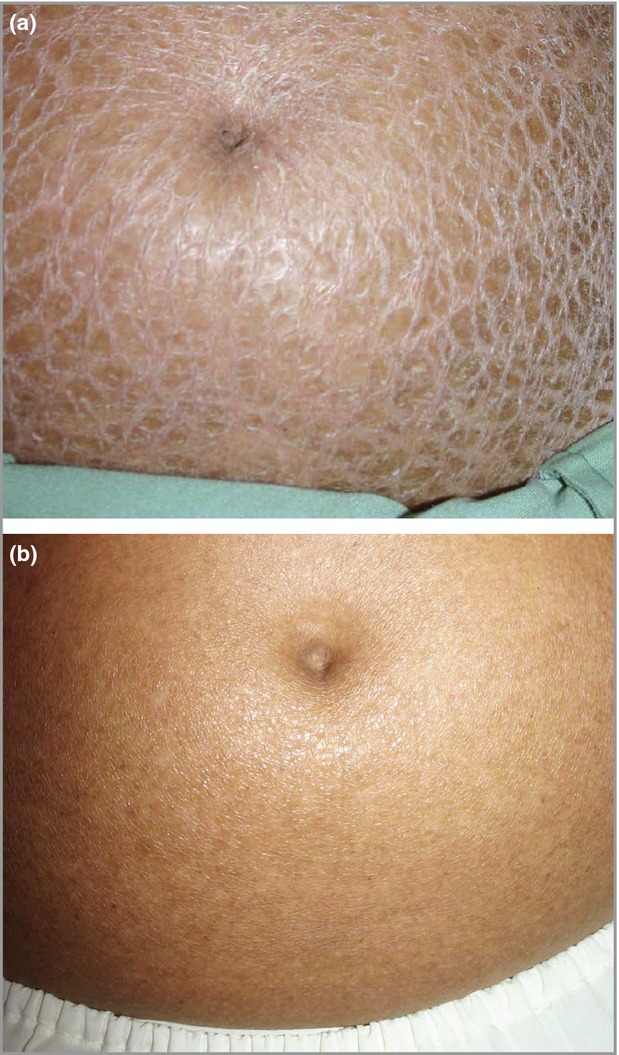

One of nine (11%) patients in the placebo group was a responder vs. 11/27 (41%) patients in the 75-mg liarozole group and 14/28 (50%) patients in the 150-mg group. However, the difference between the liarozole 150 mg and placebo groups was not significant (P = 0·056). Clinical improvement in a patient with lamellar ichthyosis following treatment with oral liarozole (150 mg) is shown in Figure2.

Figure 2.

Patient with lamellar ichthyosis (a) at baseline and (b) after 12 weeks of treatment with once-daily liarozole (150 mg). Marked improvement of scaling from severe [Investigator's Global Assessment (IGA) score of 4] at baseline to almost clear (IGA score of 1) after treatment is observed.

Secondary end variables

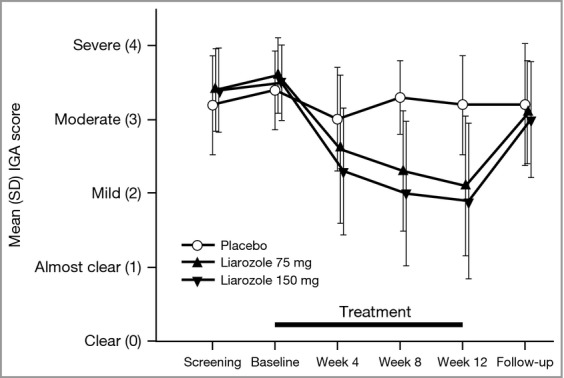

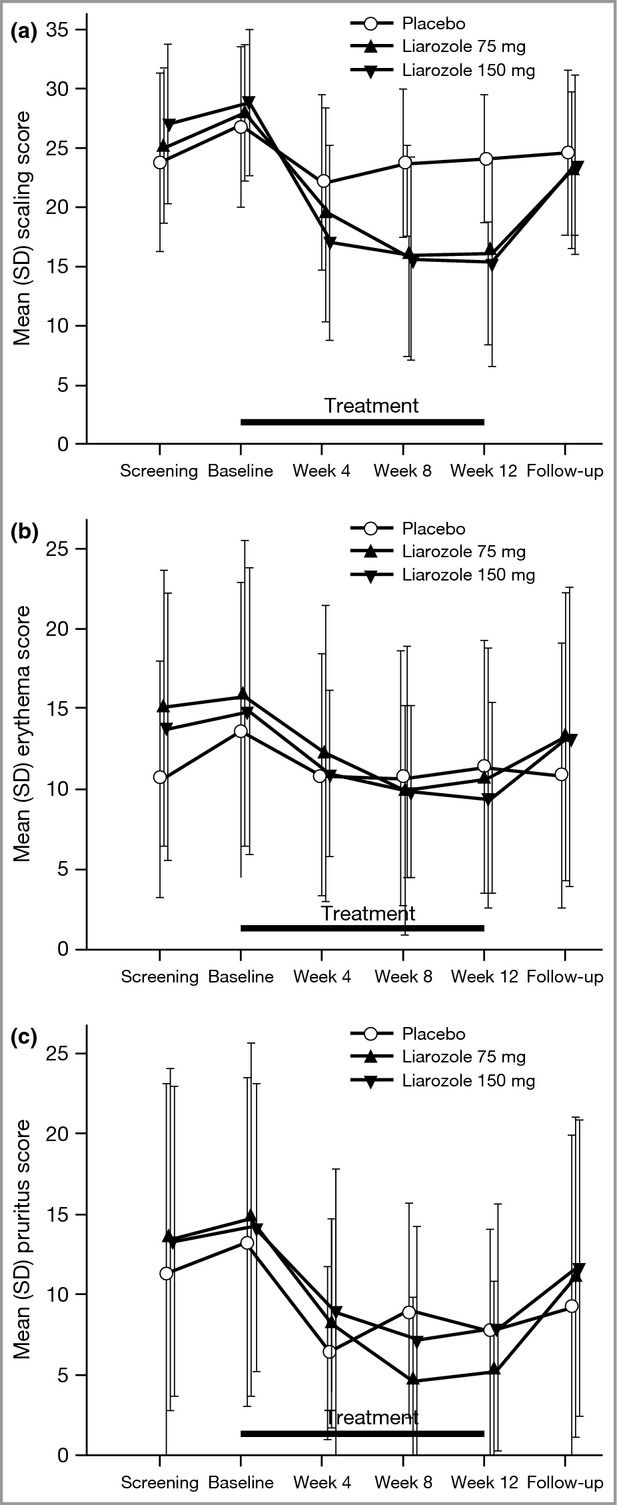

As no significant difference was demonstrated for the primary efficacy variable, formal statistical analyses were not planned to be performed on secondary efficacy variables, as per the study statistical analysis plan. Statistical analyses were, however, performed post hoc and are provided for information in Table S1 (see Supporting Information). Compared with the placebo group, mean IGA score decreased from baseline to weeks 8 and 12 in the 75- and 150-mg liarozole groups and returned to near baseline values at the follow-up visit (Fig.3). Mean scaling score, but not erythema or pruritus scores, also decreased from baseline to weeks 8 and 12 in the 75- and 150-mg liarozole groups compared with the placebo group (Fig.4). No obvious difference in the use of mechanical scale removal and emollients was observed between treatment groups. The use of emollients remained stable during the treatment period in the placebo and the 150-mg liarozole groups; a slight decrease was observed in the 75-mg liarozole group.

Figure 3.

Mean Investigator's Global Assessment (IGA) score over time (intent-to-treat population, last observation carried forward). For results of post hoc statistical analysis, see Table S1.

Figure 4.

Mean symptom scores over time: (a) scaling, (b) erythema and (c) pruritus (intent-to-treat population; last observation carried forward). For results of post hoc statistical analysis, see Table S1.

SF-36 summary measures remained mostly stable during the study in all treatment groups, except for transient improvement at week 4 in the physical component scale for patients receiving liarozole 75 mg, and in the mental component scale for patients receiving liarozole 150 mg. During the treatment period, mean DLQI score remained stable in the placebo group, whereas an improvement in mean DLQI score was observed in both liarozole groups, followed by worsening during the follow-up period (Figure S1; see Supporting Information). These trends were observed in all domains. Mean DLQI score improved significantly from baseline at week 12 in patients receiving liarozole 75 mg vs. patients receiving placebo [mean (SD) change, −4·3 (6·0); P = 0·014]. Significant differences were observed between the 75-mg liarozole and the placebo groups for all domains at week 12 (P < 0·05) except ‘personal relationships’ and ‘work and school’. No significant difference was observed between the 150-mg liarozole and the placebo groups in change from baseline of mean DLQI score at week 12 [mean (SD) change, −2·8 (3·4); P = 0·06]; however, the 150-mg liarozole group showed a significant improvement from baseline vs. the placebo group in the ‘daily activities’ (P = 0·008), ‘leisure’ (P = 0·026), and ‘symptoms and feelings’ (P = 0·023) domains.

Pharmacokinetics

In the 75- and 150-mg liarozole groups, predose and near-peak plasma concentrations remained the same order of magnitude throughout treatment, and no accumulation occurred (Table S2; see Supporting Information).

Safety

Overall, 178 AEs were reported for 45 patients (Table S3; see Supporting Information). Both liarozole groups presented a higher number of AEs than the placebo group; however, the difference between groups was not significant (liarozole 75 or 150 mg vs. placebo, P ≥ 0·062), and AE incidence did not appear to be related to liarozole dose. The most frequently reported AEs are shown in Table 2; with the exception of nasopharyngitis and nausea, all AEs occurred more frequently in the liarozole groups than in the placebo group. Treatment-emergent AEs were mostly mild to moderate in severity; four were severe (fungal infection, intermittent chest cramp, joint pain and dry skin). Two serious AEs occurred: one patient was hospitalized for deterioration of ichthyosis during the wash-out period and was not randomized to any study treatment; one patient in the 150-mg liarozole group became pregnant 10 days after the last administration of study medication and gave birth to a child with a dilated renal pelvis during the poststudy period. This condition was considered not related to liarozole treatment.

Table 2.

Incidence of adverse events occurring in > 10% of patients and two or more patients within at least one treatment group (safety population)

| Preferred terma | Placebo group (n = 9) | Liarozole 75 mg group (n = 27) | Liarozole 150 mg group (n = 28) | Liarozole, combined groups (n = 55) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nasopharyngitis | 3 (22) | 2 (7) | 4 (11) | 6 (9) |

| Alopecia | 1 (11) | 1 (4) | 5 (11) | 6 (7) |

| Fatigue | – | 3 (11) | 3 (11) | 6 (11) |

| Arthralgia | – | 2 (7) | 4 (11) | 6 (9) |

| Headache | – | 2 (7) | 4 (11) | 6 (9) |

| Nausea | 2 (22) | 2 (7) | 1 (4) | 3 (5) |

| Pruritus | – | 3 (11) | 2 (7) | 5 (9) |

| Epistaxis | – | 4 (11) | 1 (4) | 5 (7) |

| Cheilitis | – | 3 (11) | 2 (7) | 5 (9) |

| Creatine phosphokinase increased | – | 1 (4) | 3 (11) | 4 (7) |

| Hyperhidrosis | – | 3 (11) | – | 3 (5) |

| Skin exfoliation | – | 3 (11) | – | 3 (5) |

Values shown are the number of events (percentage of patients with event).

No relevant changes from baseline were observed in the mean values of alanine aminotransferase, aspartate aminotransferase, γ-glutamyltransferase, creatine phosphokinase or plasma lipids in any treatment group. Overall, 58 patients (91%) had one or more abnormal laboratory parameters during the treatment or follow-up period, which were considered clinically relevant and related to study treatment in seven of the 64 patients (11%; Table 3).

Table 3.

Most clinically relevant treatment-related adverse events (safety population)

| Placebo group (n = 9) | Liarozole 75 mg group (n = 27) | Liarozole 150 mg group (n = 28) | Liarozole, combined groups (n = 55) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Laboratory abnormalities, n | ||||

| Increased plasma creatine phosphokinase | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| Increased alanine aminotransferase | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Increased plasma lipids | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 |

| Increased blood cell count | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Physical examination abnormalities, n | 0 | 1a | 3b | 4 |

| Vital signs abnormalities, n | 0 | 1c | 1c | 2 |

| Ophthalmological abnormalities, n | 0 | 0 | 1d | 1 |

| Electrocardiogram abnormalities, n | 0 | 0 | 2e | 2 |

| Mucocutaneous symptoms, n | 1f | 6g | 4h | 10 |

Mild shoulder pain, mild arthralgia and mild pain in extremity;

moderate rash (one patient), mild hypertension (one patient), moderate herpes simplex and moderate lymphadenopathy (one patient);

hypertension (mild in 150-mg group, moderate in 75-mg group);

moderate worsening of Schirmer's tear test and tearfilm break-up time;

moderate ventricular extrasystoles (one patient), mild abnormal electrocardiogram (not further specified) that was already reported at screening (one patient);

mild alopecia;

mild epistaxis (three patients), mild cheilitis (two patients), moderate cheilitis (one patient), moderate alopecia (one patient);

moderate epistaxis (one patient), mild alopecia (one patient), mild alopecia and mild cheilitis (two patients).

No relevant changes in ECG intervals were observed. Two ECG abnormalities were reported as treatment-related AEs (Table 3). Most physical examination, vital signs and ophthalmological abnormalities recorded during the treatment and follow-up phases, as appropriate, were reported at screening or baseline, and were not considered clinically relevant. Those reported as AEs possibly related to study drug are shown in Table 3. There were no significant differences between treatment groups regarding the change from baseline in severity scores for mucocutaneous symptoms. Eleven patients reported mucocutaneous symptoms that were recorded as AEs, all of which were considered to be related to the study treatment (Table 3).

Slight increases in bone resorption biomarkers (serum CTX and urinary NTX) from baseline were observed in both liarozole groups; however, this effect was of low magnitude, not dose related and did not differ significantly from the placebo group except for CTX (75-mg liarozole group) 4 weeks after discontinuation of liarozole treatment. Liarozole induced a modest, significant, dose-related decrease in the bone formation marker serum PINP from baseline in both liarozole groups (75 mg: −11·72%, P = 0·0224; 150 mg: −16·00%, P = 0·0036); this decrease was transient and returned to baseline concentrations 4 weeks after termination of liarozole treatment. No significant changes in serum bone formation marker osteocalcin were observed, except a significant increase vs. baseline (P = 0·0005) and placebo (P = 0·04) in the 75-mg liarozole group 4 weeks after therapy discontinuation. This isolated increase was not dose related.

Discussion

The primary objective of this study was to demonstrate the efficacy of two different once-daily doses of oral liarozole vs. placebo in patients with lamellar ichthyosis. In the liarozole groups, 41% (75-mg liarozole group) and 50% (150-mg liarozole group) of patients were considered responders to treatment vs. 11% of patients in the placebo group. However, the difference between the 150-mg liarozole group and the placebo group at week 12 was not significant (P = 0·056). As the study was terminated prematurely as a result of slow recruitment, failure to reach significance may have been largely due to diminished statistical power of the reduced sample size. Furthermore, the definition of a responder (≥ 2-point decrease in IGA score) may not have been ideal owing to possible spontaneous fluctuation in ichthyosis severity and low sensitivity of a subjective 5-point scale. IGA and scaling scores decreased in both liarozole treatment groups vs. the placebo group. Changes in erythema and pruritus were similar between treatment groups, and no obvious difference in the use of emollients or mechanical scale removal was observed between treatment groups, possibly due to continued daily skincare routines of many patients with lamellar ichthyosis. While QoL remained mostly stable during the study when assessed using the SF-36 health survey, a disease nonspecific assessment,15 improvement in QoL was observed at week 12 in patients receiving both liarozole doses compared with placebo using a skin disease-specific assessment (DLQI).

Once-daily liarozole, 75 or 150 mg, for 12 weeks was well tolerated. No undue accumulation of liarozole was observed in pharmacokinetic studies, and there were no relevant differences between the liarozole groups and the placebo group with regard to safety parameters. Most patients (91%) had at least one laboratory abnormality during the treatment and follow-up periods; these were considered clinically relevant in seven patients (11%) (five of whom were in the 150-mg liarozole group). Safety findings are consistent with those of previous 12-week studies of twice-daily oral liarozole at 150 and 75 mg.12,13 A modest transient decrease in PINP, a marker of type I collagen synthesis and bone formation, was observed during the trial; the long-term effect of liarozole on bone turnover is unknown.

Reduced sample size limits the efficacy conclusions that can be drawn from the study; despite this, the sample size is considerable given the rarity of the disease and the stringent eligibility criteria for study participation. Future studies should consider more congruent and effective eligibility criteria, an assessment of treatment success more consistent with clinical practice, and the low prevalence of lamellar ichthyosis, when planning the size of the study population. When limited numbers of patients can be recruited, a different randomization scheme, for example with equal size placebo and active treatment groups, would increase the power to detect a treatment effect.

In conclusion, statistical significance was not obtained for the primary efficacy variable (response rate), possibly due to decreased statistical power as a consequence of reduced sample size. Compared with placebo, oral liarozole, 75 or 150 mg, once daily for 12 weeks, reduced the overall severity of ichthyosis and scaling, but not erythema or pruritus, and improved DLQI in patients with moderate or severe lamellar ichthyosis. Oral liarozole was well tolerated.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank all participating patients and the following study investigators: A. Gånemo (Lund University, Malmö, Sweden), G. Zambruno (Istituto Dermopatico dell'Immacolata, Rome, Italy), R. Caputo (Clinica Dermatologica I, Milan, Italy), W. Gulliver (NewLab Clinical Research, Inc., St John's, Canada), N. Mørk (Rikshospitalet Universitetsklinik, Oslo, Norway), J.-F. Stalder (Nantes University Hospital, Nantes, France), D. Marcoux (CHU Sainte-Justine, Montreal, Canada), H. Boonen (Private Practice, Geel, Belgium), D. Roseeuw (University of Brussels VUB, Brussels, Belgium), W. Küster and M.-L. Preil (Tomesa Fachklinik, Bad Salzschlirf, Germany), B.P. Korge (University of Cologne, Cologne, Germany), A.P. Oranje (Erasmus MC – Sophia Children's Hospital and KinderHaven, Rotterdam, the Netherlands), H. Gollnick (University of Magdeburg, Magdeburg, Germany) and V. Oji (University Hospital Münster, Münster, Germany). The authors thank Luc Meuleners (SGS Life Science Services–Clinical Research, Mechelen, Belgium) for assistance with statistical analyses. The authors express special thanks in memory of our colleague Wolfgang Küster (TOMESA Speciality Clinic for Dermatology, Bad Salzschlirf, Germany), dedicated dermatologist and co-investigator, who did not live to see the results of this trial. The authors also thank Alyson Bexfield, PhD of Caudex Medical, Oxford, U.K. (supported by Stiefel, a GSK company, Research Triangle Park, NC, U.S.A.) for assistance with preparing the initial draft of the manuscript, collating the comments of authors, and assembling the tables.

Supporting Information

Additional Supporting Information may be found in the online version of this article at the publisher’s website:

Table S1. Mean (standard deviation) changes from baseline in Investigator’s Global Assessment (IGA) score and symptom scores at weeks 8 and 12, showing statistical significance for comparisons between liarozole and placebo groups (intent-to-treat population).

Table S2. Liarozole predose and near-peak plasma concentrations.

Table S3. Summary of adverse events (safety population).

Fig. S1. Change in mean Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI) over time (intent-to-treat population; last observation carried forward).

References

- 1.Oji V, Tadini G, Akiyama M, et al. Revised nomenclature and classification of inherited ichthyoses: results of the First Ichthyosis Consensus Conference in Soreze 2009. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;63:607–41. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2009.11.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vahlquist A, Ganemo A, Virtanen M. Congenital ichthyosis: an overview of current and emerging therapies. Acta Derm Venereol. 2008;88:4–14. doi: 10.2340/00015555-0415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Oji V, Traupe H. Ichthyoses: differential diagnosis and molecular genetics. Eur J Dermatol. 2006;16:349–59. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hernandez-Martin A, Garcia-Doval I, Aranegui B, et al. Prevalence of autosomal recessive congenital ichthyosis: a population-based study using the capture–recapture method in Spain. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67:240–4. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2011.07.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ganemo A, Lindholm C, Lindberg M, et al. Quality of life in adults with congenital ichthyosis. J Adv Nurs. 2003;44:412–19. doi: 10.1046/j.0309-2402.2003.02820.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kamalpour L, Gammon B, Chen KH, et al. Resource utilization and quality of life associated with congenital ichthyoses. Pediatr Dermatol. 2011;28:512–18. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1470.2011.01432.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Summary of Product Characteristics, 2011. Neotigason 10 mg capsules. Available at: http://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/medicine/21212/SPC/Neotigason+10 mg+Capsules/ (last accessed 23 October 2013)

- 8. Medication guide for patients. Soriatane capsules, 2011. Available at: http://www.fda.gov/downloads/Drugs/DrugSafety/ucm089133.pdf (last accessed 23 October 2013)

- 9.Barrier Therapeutics, Inc. Barrier Therapeutics granted European orphan drug status for liarozole, 2003. Available at: http://www.prnewswire.com/news-releases/71303547.html (last accessed 23 October 2013)

- 10.Barrier Therapeutics, Inc. Barrier Therapeutics' liarozole receives FDA orphan drug status, 2004. Available at: http://www.prnewswire.com/news-releases/barrier-therapeutics-liarozole-receives-fda-orphan-drug-status-75105912.html (last accessed 23 October 2013)

- 11.Verfaille CJ, Borgers M, van Steensel MA. Retinoic acid metabolism blocking agents (RAMBAs): a new paradigm in the treatment of hyperkeratotic disorders. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2008;6:355–64. doi: 10.1111/j.1610-0387.2007.06541.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lucker GP, Heremans AM, Boegheim PJ, et al. Oral treatment of ichthyosis by the cytochrome P-450 inhibitor liarozole. Br J Dermatol. 1997;136:71–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Verfaille CJ, Vanhoutte FP, Blanchet-Bardon C, et al. Oral liarozole vs. acitretin in the treatment of ichthyosis: a phase II/III multicentre, double-blind, randomized, active-controlled study. Br J Dermatol. 2007;156:965–73. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2006.07745.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.World Medical Association. 2008. World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki; ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. Available at: http://www.wma.net/en/30publications/10policies/b3/17c.pdf (last accessed 23 October 2013)

- 15.Ware JE., Jr SF-36 health survey update. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2000;25:3130–9. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200012150-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Finlay AY, Khan GK. Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI) – a simple practical measure for routine clinical use. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1994;19:210–16. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2230.1994.tb01167.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lewis V, Finlay AY. 10 years' experience of the Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI) J Investig Dermatol Symp Proc. 2004;9:169–80. doi: 10.1111/j.1087-0024.2004.09113.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1. Mean (standard deviation) changes from baseline in Investigator’s Global Assessment (IGA) score and symptom scores at weeks 8 and 12, showing statistical significance for comparisons between liarozole and placebo groups (intent-to-treat population).

Table S2. Liarozole predose and near-peak plasma concentrations.

Table S3. Summary of adverse events (safety population).

Fig. S1. Change in mean Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI) over time (intent-to-treat population; last observation carried forward).