Abstract

Introduction

A depth-ranging sensor (Kinect) based upper extremity motion analysis system was applied to determine the spectrum of reachable workspace encountered in facioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy (FSHD).

Methods

Reachable workspaces were obtained from 22 individuals with FSHD and 24 age- and height-matched healthy controls. To allow comparison, total and quadrant reachable workspace relative surface areas (RSA) were obtained by normalizing the acquired reachable workspace by each individual’s arm length.

Results

Significantly contracted reachable workspace and reduced RSAs were noted for the FSHD cohort compared to controls (0.473±0.188 vs. 0.747±0.082; P<0.0001). With worsening upper extremity function as categorized by the FSHD evaluation subscale II+III, the upper quadrant RSAs decreased progressively, while the lower quadrant RSAs were relatively preserved. There were no side-to-side differences in reachable workspace based on hand-dominance.

Discussion

This study demonstrates the feasibility and potential of using an innovative Kinect-based reachable workspace outcome measure in FSHD.

Key words/MESH terms: Reachable workspace, Upper extremity, Function, FSHD, Kinect

INTRODUCTION

Facioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy (FSHD) is a slowly progressive autosomal dominantly inherited myopathy with an estimated prevalence of 1:15,000–1:20,000.1–3 FSHD is caused by loss of a critical number of sub-telomeric D4Z4 macrosatellite repeats that contain copies of DUX4 homeodomain retrogene.4–6 As its clinically descriptive name implies, FSHD most notably affects facial and shoulder girdle muscles. However, patients with FSHD also develop weakness in anterolateral leg, hip girdle, distal upper extremity, and neck and back muscles. In some patients with progression of the disease to involve the lower extremity muscles, ambulation can be affected with estimates of about 20% becoming wheelchair dependent.7 However, the hallmark pattern of weakness in FSHD causing significant functional impairment occurs in the shoulder girdle.7,8 The stereotypical progression of weakness in the shoulder girdle and humeral region results in anterior rotation of shoulders (sloping shoulder posture), scapular winging, triangular shoulders, and loss of ability to abduct the arms.

Recent efforts to develop treatment for FSHD have identified a host of potential therapeutic targets for FSHD including ribonucleic acid (RNA) interference and other gene silencing strategies that block DUX4 expression or mitigate the downstream effects of DUX4 expression.9,10 In addition to agents that target the genetic mechanism producing FSHD, randomized clinical trials are being considered to determine the efficacy of several promising pharmacologic compounds (including selective androgen receptor modulators, myostatin inhibitors, and troponin activators) that aim to promote muscle growth, reduce muscle degeneration, and/or improve skeletal muscle function.11

Evaluating the efficacy of these promising therapeutic agents for FSHD will require development of appropriate clinical trial outcome measures. Traditionally, most of the efficacy trials in neuromuscular diseases have focused on mobility (6-minute walk test) and lower limb outcome measures (time to stand, time to climb 4 stairs) as their primary outcome measure.12–14 However, focusing on ambulatory outcome measures for clinical trials in FSHD would not measure the primary impairment that is most common to individuals with FSHD, weakness of the shoulder girdle and impairment of the upper extremity function. Furthermore, upper extremity function is critical to evaluate and include in clinical studies, since it is tied closely to an individual’s basic self-care activities of daily living (ADLs: feeding, grooming, dressing, and bowel and bladder care), independence, and quality of life. Several recent international workshops have highlighted the need to identify and develop innovative clinical outcome measures that can be used for efficacy studies in both ambulatory and non-ambulatory neuromuscular disease populations.15–18

To address the lack of clinical tools for evaluation of upper extremity function, we have previously developed an innovative 3-dimensional (3D) vision-based sensor system (using a single depth-ranging sensor rather than the costly traditional multi-camera motion capture system) that can unobtrusively detect an individual’s reachable workspace that reflects individual global upper extremity function.19–21 Evaluation of the developed outcome measure framework and detection system using a commercially available and cost-effective single sensor platform (Microsoft Kinect sensor) demonstrated its validity, high reliability, and promise towards clinical trials in various neuromuscular disorders.22

In this study, we assessed the applicability of the Kinect-based reachable workspace outcome measure in FSHD. Specifically, we aimed to determine the spectrum of reachable workspace in a cohort of individuals with FSHD compared with a cohort of healthy controls. In addition, we wanted to evaluate the feasibility, validity, and discriminative ability of the Kinect-based 3D upper extremity motion analysis system to assess the reachable workspace in FSHD patients.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Participants

Twenty-two subjects with FSHD (11 women, 11 men; average age: 53.7 ± 18.8 years) and 24 healthy controls (12 women, 12 men; average age: 45.9 ± 14.1 years) participated in the study. The FSHD study participants were recruited from a regional neuromuscular disease clinic. All FSHD participants were diagnosed based on confirmed genetic analysis showing loss of D4Z4 repeats of the DUX4 homeodomain retrogene at the chromosome 4q35 telomere. Healthy controls without any neuromuscular or musculoskeletal disorders were recruited through University Institutional Review Board (IRB) approved advertisements and postings. Exclusion criteria for controls consisted of individuals with impairment in arm function that prevented abduction in a full circle until they touched above the head. The study protocol was approved by the University IRB for human protection and privacy for research. Consent was obtained prior to study participation from all subjects or parents/guardians and was documented by a signed IRB approved consent form.

Experimental Procedures

Clinical history, demographic and anthropometric information (age, sex, height and weight) were obtained from each subject. Arm lengths for each subject were extracted automatically from the Kinect sensor data as described previously.22 The FSHD evaluation scale23 (score: 0–15) was used to characterize quantitatively the clinical severity of the disease in all study subjects.

Briefly, the FSHD evaluation scale and “clinical score” assesses the strength and functionality of 6 muscle groups on an ordinal scale: (I) facial muscles, (II) scapular girdle muscle, (III) upper limb muscles, (IV) distal leg muscles, (V) pelvic girdle muscles, and (VI) abdominal muscles. Global upper limb function was characterized further on a 6-point scoring system by combining the values from the scapular girdle subscale (II: scored 0–3) and the upper limb subscale (III: scored 0–2) of the FSHD evaluation scale. The FSHD evaluation subscale for scapular girdle function (II) uses a scoring system where a value of 0 is given if there is no impairment, a value of 1 is given if there is mild involvement with no limitation of arm abduction, a value of 2 is given if the arm abduction is >45°, and a value of 3 is given if the arm abduction is ≤45°. For the upper limb muscle subscale (III), a value of 0 is given if there is no involvement of triceps, biceps, common finger and wrist extensors, and long finger and wrist flexors from either arm, a value of 1 is given if at least 2 of the aforementioned muscles are affected with Medical Research Council (MRC) scale strength score >3, and a value of 2 is given if at least two of the aforementioned muscles has a value ≤3 on the MRC scale (unable to move the limbs against gravity). All control subjects were healthy, and each had a combined FSHD evaluation scale score of 0. The total FSHD evaluation scale scores and the combined (additive) scores of the subscales II & III, as well as the Kinect-acquired reachable workspace data were collected in all subjects.

Upper Extremity Reachable Workspace Protocol

The experimental protocol for sensor system setup and arm movement detection followed the already published protocol.22 Subjects were seated in front of the Microsoft Kinect sensor and underwent a standardized upper extremity movement protocol under the supervision of a study clinical evaluator, as described previously.22 Briefly, a simple set of standardized movements consisted of lifting the arm from the resting position to above the head while keeping the elbow extended, performing the same movement in vertical planes at around 0, 45, 90, and 135 degrees. The second set of movements consisted of horizontal sweeps at the level of the umbilicus and shoulder. The entire sequence of movements was recorded together. The study protocol movements typically took less than 1 minute for the entire sequence of movements, yet the shoulder underwent its full range of motion (except for the extreme shoulder extension that is limited by the back of the chair). To standardize the assessment and control for execution speed, the participants followed a pre-recorded instructor’s movement through a video feedback. Subjects were instructed to reach as far as they could while keeping the elbow extended, and without leaning forward or twisting the body. If they were unable to reach further, they were instructed to return to the initial starting position with their arms at their side, and perform the next sequence of movements. In addition, the study clinical evaluator (Kinesiologist, AN) also demonstrated the movements in front of the subject to dictate the speed, monitor for excessive compensatory movements (trunk rotation or leaning forward), and further reinforce the order of movement sequence. If the subject leaned or trunk rotations were observed, the recording was repeated from the beginning with adequate rest breaks.

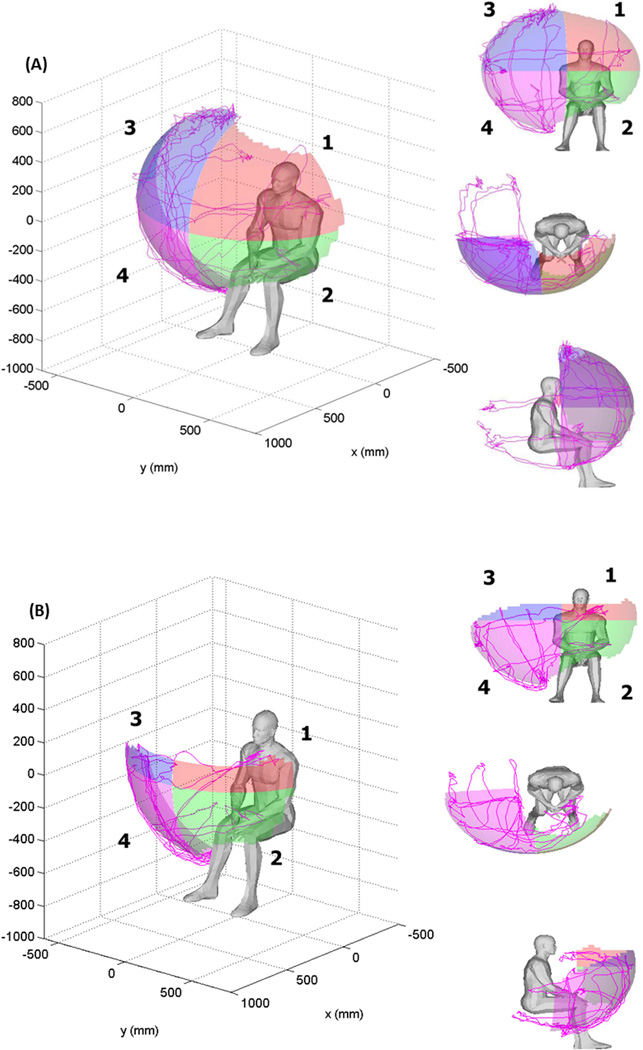

Reachable Workspace Surface Envelope Analysis

The Kinect sensor-tracked 3D hand trajectory was transformed into a body-centric coordinate system, and each individual’s reachable workspace envelope was reconstructed in a graphical output using methods described previously.19–22 Each side’s reachable workspace envelope was divided into 4 quadrants with the shoulder joint serving as the origin. The sagittal plane through the shoulder joint defined the ipsilateral and contralateral side of the workspace, while the horizontal plane at the level of the shoulder joint defined the top and bottom parts of the workspace quadrants. The quadrants are enumerated as shown in Figure 1. As previously described and validated, we calculated the absolute total reachable workspace surface envelope area (m2) as well as areas for each of the quadrants.19–22 Normalization of acquired reachable workspace by each individual’s Kinect-extracted arm length and unit hemi-sphere (relative surface area: RSA) allowed comparison between subjects. The reachable workspace RSA represents the portion of the unit hemi-sphere that is covered by an individual’s hand movement. It is determined by dividing the absolute reachable workspace surface envelope area by the factor 4πr2 × (1/2), where r represents the distance between the shoulder joint and fingertips. This allows scaling of the data by each person’s arm length to allow normalization for comparison between subjects.

Figure 1. Example graphical outputs of Kinect sensor acquired total and quadrant reachable workspace.

A healthy control individual’s reachable workspace viewed from different directions is shown, with quadrants designated by different colors and enumerated 1–4 (A). An example graphical output of the reachable workspace for an individual with moderately impaired upper extremity function is shown in (B).

Statistical Analyses

The objectives of this study are to develop and test a new outcome measure that could be used to describe the central tendency and variability of this test in subjects with upper extremity functional impairments from FSHD as compared to able-bodied healthy controls. We assessed the validity by determining whether subjects with documented impairment in ROM had significantly reduced reachable workspace. Data was checked for normality through the Shapiro Wilk test and analyzed parametrically. Differences were determined between subgroups by using an ANOVA or t-tests for 2 groups. All statistical analyses were conducted using SAS 9.2 software. For all statistical analyses, a P-value of 0.05 was accepted as the level of statistical significance.

RESULTS

Study participants

The primary aim of the study is to characterize and compare the Kinect sensor acquired reachable workspace surface envelope areas between the 2 cohorts, 22 participants with FSHD and 24 controls. There was no significant age difference between the FSHD and control cohorts (52.5 ± 19.0 years vs. 44.6 ± 15.0 years; P=0.12). In addition, there was no significant difference in heights of the 2 cohorts (FSHD mean 168.8cm, Control mean 170.3cm, P=0.47). Table 1 provides a basic description of the demographics of the FSHD cohort by age, gender, height, weight, total FSHD evaluation scale score, and combined subscale scores for II (scapular girdle involvement) and III (upper limb involvement). Of the 22 FSHD participants, only 1 was unable to complete the reachable workspace assessment due to severe upper extremity weakness. This participant was the oldest of the 3 participants with the most impaired upper extremity function score (combined FSHD subscale II & III score of 5). The remainder of the FSHD participants, encompassing various levels of overall severity (FSHD clinical scores ranging from 2 to 11) and displaying a full-spectrum of upper extremity weakness (combined FSHD subscale II and III scores ranging from 1 to 5), were able to complete the reachable workspace protocol.

Table 1.

Demographics of the study participants with FSHD.

| Patient ID |

Age (yrs) | Gender | Height (cm) |

Weight (kg) |

FSHD evaluation scale score (range: 0–15) |

Combined score of subscale II + III (range: 0–5) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 72.79 | M | 173.5 | 89.1 | 3 | 1 |

| 2 | 74.18 | M | 167.4 | 74.5 | 3 | 2 |

| 3 | 50.03 | M | 188.5 | 86.7 | 5 | 2 |

| 4 | 60.02 | M | 166.4 | 88.2 | 5 | 2 |

| 5 | 45.26 | M | 181.5 | 87.2 | 3 | 2 |

| 6 | 64.70 | W | 157.5 | 66.7 | 3 | 2 |

| 7 | 26.11 | W | 173.0 | 59.5 | 2 | 2 |

| 8 | 16.56 | W | 155.2 | 46.6 | 5 | 2 |

| 9 | 50.17 | W | 166.0 | 71.7 | 7 | 3 |

| 10 | 12.04 | W | 148.5 | 32.9 | 5 | 3 |

| 11 | 73.88 | W | 166.5 | 90.9 | 8 | 3 |

| 12 | 71.83 | W | 170.0 | 120.4 | 7 | 3 |

| 13 | 46.18 | M | 178.0 | 75.9 | 5 | 3 |

| 14 | 73.73 | W | 162.0 | 83.6 | 7 | 3 |

| 15 | 72.84 | M | 183.0 | 112.8 | 8 | 3 |

| 16 | 45.88 | M | 179.0 | 108.6 | 10 | 3 |

| 17 | 26.55 | W | 155.3 | 76.5 | 8 | 3 |

| 18 | 58.66 | W | 155.0 | 73.5 | 11 | 4 |

| 19 | 58.87 | W | 164.0 | 67.9 | 4 | 4 |

| 20 | 44.68 | M | 180.0 | 90.9 | 11 | 5 |

| 21 | 58.10 | M | 174.5 | 93.4 | 10 | 5 |

| 22* | 62.20 | M | 171.5 | 74.1 | 11 | 5 |

unable to complete the reachable workspace protocol.

Reachable workspace comparison between healthy controls and a cohort of individuals with FSHD

Figure 1 shows the example graphical outputs of the reachable workspace and quadrant enumeration from a healthy control and an individual with FSHD. Table 2 lists the mean relative surface area (RSA) of the reachable workspace envelope for individuals with FSHD and controls by quadrant and total area. Participants with FSHD demonstrate significantly less RSA than controls in upper quadrants 1, 3, and the ipsilateral lower quadrant 4 (P<0.01). No significant differences were observed in quadrant 2 (contralateral lower quadrant) between the cohorts (P=0.173). Figure 2 presents the difference between the mean RSA values graphically for the FSHD cohort (blue) and controls (red) on a radar plot.

Table 2.

Mean ± S.D. relative surface area (RSA) of the reachable workspace surface envelope from controls and FSHD subjects by quadrant and total area

| Quad 1 | Quad 2 | Quad 3 | Quad 4 | TOTAL | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Contralateral Quadrant | Ipsilateral Quadrant | ||||

| Cohort (n) | Upper | Lower | Upper | Lower | |

| FSHD (42) | 0.071 ± 0.072 | 0.086 ± 0.050 | 0.103 ± 0.083 | 0.211 ± 0.028 | 0.473 ± 0.188 |

| Control (48) | 0.178 ± 0.047 | 0.129 ± 0.041 | 0.214 ± 0.026 | 0.227 ± 0.011 | 0.747 ± 0.082 |

| FSHD vs. Control (P-value) | 0.0057 | 0.173 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 |

Means ± SD and sample size (n) are presented as the average for dominant and non-dominant sides (there were no significant side-to-side differences, see Table 3). FSHD vs. Control by a two-sample t-test.

Figure 2. Radar plot showing mean quadrant relative surface area (RSA) by groups.

FSHD patients are shown with a blue line, Controls are shown with a red line (plot shown from right side perspective). The asterisk (*) represents significant differences between cohorts (P<0.01).

Reachable workspace and Hand dominance

Association between reachable workspace and hand dominance for both the FSHD and control cohorts was evaluated. We observed no significant differences in reachable workspace between dominant and non-dominant sides in any quadrant for both the FSHD and control cohorts. Table 3 lists the mean relative surface area (RSA) for dominant vs. non-dominant sides of the FSHD and control cohorts by quadrant and total area.

Table 3.

Mean ± S.D. relative surface area (RSA) of the reachable workspace surface envelope from controls and FSHD subjects by quadrant and total area by dominant and non-dominant sides

| Quad 1 | Quad 2 | Quad 3 | Quad 4 | TOTAL | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Contralateral Quadrant | Ipsilateral Quadrant | |||||

| Dominance (n) | Upper | Lower | Upper | Lower | ||

| FSHD | Non-Dominant (21) | 0.085 ± 0.083 | 0.094 ± 0.047 | 0.103 ± 0.087 | 0.206 ± 0.028 | 0.487 ± 0.204 |

| Dominant (21) | 0.058 ± 0.059 | 0.079 ± 0.053 | 0.104 ± 0.082 | 0.217 ± 0.028 | 0.458 ± 0.175 | |

| Non-Dominant vs. Dominant | P=0.1416 | P=0.5595 | P=0.7826 | P=0.9954 | P=0.5027 | |

| Control | Non-Dominant (24) | 0.181 ± 0.050 | 0.132 ± 0.046 | 0.207 ± 0.026 | 0.222 ± 0.011 | 0.741 ± 0.086 |

| Dominant (24) | 0.175 ± 0.046 | 0.125 ± 0.035 | 0.221 ± 0.025 | 0.233 ± 0.009 | 0.753 ± 0.080 | |

| Non-Dominant vs. Dominant | P=0.6889 | P=0.2224 | P=0.8646 | P=0.3463 | P=0.7242 | |

Non-Dominant vs. Dominant for FSHD and Controls by a two-sample t-test, P-value as noted.

Reachable workspace by FSHD Evaluation Subscale II and III

Table 4 reports the mean reachable workspace relative surface area (RSA) for the FSHD cohort stratified by a combined FSHD evaluation subscale II and III scores. Sub-group analyses were not appropriate and unavailable due to the majority of patients disproportionately displaying evaluation scores of 2 and 3 (and small sample size in other categories).

Table 4.

Mean ± S.D. relative surface area (RSA) of the reachable workspace surface envelope from FSHD subjects by quadrant and total area by FSHD Evaluation Subscale II & III combined.

| Quad 1 | Quad 2 | Quad 3 | Quad 4 | TOTAL | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Contralateral Quadrant | Ipsilateral Quadrant | |||||

| FSHD Evaluation Subscale II & III combined score (n) |

Mean Age |

Upper | Lower | Upper | Lower | |

| 1 (2) | 72.79 | 0.152 ± 0.013 | 0.079 ± 0.019 | 0.220 ± 0.012 | 0.227 ± 0.003 | 0.678 ± 0.018 |

| 2 (14) | 48.12 | 0.114 ± 0.072 | 0.102 ± 0.061 | 0.166 ± 0.061 | 0.222 ± 0.015 | 0.605 ± 0.150 |

| 3 (18) | 52.57 | 0.058 ± 0.065 | 0.093 ± 0.040 | 0.084 ± 0.065 | 0.215 ± 0.028 | 0.449 ± 0.146 |

| 4 (4) | 58.77 | 0.014 ± 0.017 | 0.064 ± 0.032 | 0.001 ± 0.002 | 0.194 ± 0.025 | 0.273 ± 0.067 |

| 5 (4) | 51.39 | 0.001 ± 0.002 | 0.027 ± 0.028 | 0.017 ± 0.035 | 0.167 ± 0.029 | 0.213 ± 0.067 |

Means ± SD and sample size (n) are presented as the average for dominant and non-dominant sides (there were no significant side to side differences, see Table 3

As can be observed in Figure 3A and 3B, the trend shows an inverse relationship between the reachable workspace RSAs and the combined subscale II & III scores: lower combined score (less upper extremity impairment) results in larger reachable workspace RSAs. On the other hand, as the upper extremity function worsens in the FSHD cohort with higher combined subscale II and III scores, the reachable workspace gradually gets smaller with the upper quadrant RSAs (quadrants 1 and 3) being affected most dramatically.

Figure 3. Radar plot and bar graph showing mean quadrant relative surface area (RSA) for FSHD patients stratified by FSHD evaluation scale II & III combined score.

(A) FSHD patients with score of 1 shown with a dark blue line, 2 in red, 3 in green, 4 in purple, and 5 in light blue; plot shown from right side perspective. (B) Bar graph showing the gradual reduction in the total and quadrant RSAs by combined FSHD subscale II & III. (healthy control=0, and combined subscale II & III scores: 1–5).

DISCUSSION

Upper extremity function is significantly impaired in FSHD. It impacts not only the activities of daily living, but independence status and quality of life are affected as well. There are many clinical outcome measure options available for assessment of the upper extremity, including manual and quantitative muscle test (MMT, QMT), goniometry (range of motion, ROM), standardized timed function tests (9-hole peg test),24 Jebsen-Taylor hand function test,25 and motor function scales (Brooke; Disabilities of Arm, Shoulder, and Hand-DASH).26,27 Traditionally, 2 of the most commonly used measures to assess upper extremity function have been range of motion (ROM) and strength. Although ROM and strength measures provide quantitative results that can be useful for tracking segmental upper extremity function, they inherently isolate specific joint or body segments and provide limited portrayal of the global upper extremity functional deficits. In addition, ROM information is presented typically as a long list of numerical joint angles, which makes visualization of overall upper extremity functional performance challenging and non-intuitive. Furthermore, ROM and strength measures as well as many of the other clinical assessments are time-consuming, effort-intensive, and often operator experience-dependent.

In order to meet these challenges in assessing upper extremity function and to provide a reliable and valid outcome measure that is scalable for clinical studies, we have developed an intuitive 3D reachable workspace outcome measure obtained via a markerless single depth-ranging camera sensor system.19,20 In our previously published studies, we demonstrated the validity and reliability of acquiring upper extremity motion data using a cost-effective and unobtrusive vision-based sensor system (Microsoft Kinect) to reconstruct a 3D reachable workspace that is reflective of an individual’s global upper extremity function.21,22 The continuous nature of the reachable workspace surface area outcome measure allows for increased sensitivity to detect subtle changes in upper extremity functional capacity as well as flexibility to apply sophisticated statistical analysis methods that would not be possible with ordinal outcome variables. Furthermore, normalization of reachable workspace by each individual’s arm length (relative surface area, RSA) allows comparison between individuals with different height/arm lengths and ages and is applicable across patient groups. As a global upper extremity functional measure, the reachable workspace can also account for factors that would otherwise alter upper extremity active range of motion (such as contractures reducing an ‘effective radius’ of the arm length used for reachable workspace).

In this study, we applied the reachable workspace outcome measure clinically to FSHD, where stereotypical shoulder girdle weakness is a prominent and debilitating feature of the disease. Specifically, we examined the applicability and discriminative ability of the Kinect-based 3D upper extremity motion analysis system to assess the reachable workspace in a cohort of individuals representing a wide spectrum of clinical phenotypes that can be encountered in FSHD population. Recently, the FSHD evaluation scale and clinical score23 was developed specifically for FSHD to provide an overall assessment of disease severity. The subscales II (scapular girdle) and III (upper limb) focus on clinical evaluation of upper extremity function. However, the ordinal nature of these scores may provide a general assessment of a patient’s ability but are limited by relative lack of granularity and sensitivity to detect subtle changes in upper extremity function.

Our data show reachable workspace RSA can be obtained from a range of phenotypes and can discriminate between healthy controls and a cohort of individuals with FSHD. Furthermore, it could characterize and differentiate FSHD individuals with mild upper extremity impairment from those with progressively worse upper extremity function, as classified by the FSHD subscales focused on the upper extremity (II and III). Importantly, the results show that reachable workspace RSA can be acquired from the full range of FSHD phenotypes spanning from the least affected (those with FSHD evaluation scale total score of 2 & combined subscale II+III score of 1) to the most severely affected (FSHD total score of 11 & combined subscale II+III score of 5). Only 1 participant who was the most severely affected and oldest was not able to undergo the reachable workspace protocol or provide a recordable reachable workspace RSA measurement. These are important issues to consider, as clinical trial design should take into account factors such as minimizing data loss and participant burden, as well as advantages for those outcome measures that can span both ambulatory and non-ambulatory subjects in rare diseases with limited participant pools for recruitment.

The study results show that the reachable workspace RSA outcome measure can provide additional granularity through analysis by side (ipsilateral versus contralateral) or by quadrants (upper versus lower). Figures 3A and 3B demonstrate the advantages or reachable workspace RSA over an ordinal clinical scale by providing additional context-rich information about an individual’s upper extremity function. As the upper extremity function worsens with progressive weakness and results in increased FSHD combined subscale II + III score, not only does the total reachable workspace contract, but the upper quadrants (1 and 3) are reduced disproportionately while the lower quadrants (2 and 4) are preserved. It appears that by the time individuals with FSHD attain a combined subscale II+III score of 4, little if any overhead reach activities can be achieved. In the context of daily living activities, this may translate to significant difficulty in oral/facial hygiene activities, hair management, or even feeding activities. In the context of clinical trials, depending on the target of the therapeutic treatment and purpose of the study, any of these endpoints may be useful as outcome variables to assess changes in upper extremity range of motion.

In addition, using the reachable workspace RSA, we undertook examination of the potential side-to-side (dominant vs. non-dominant) difference which may exist in the FSHD population. As has been shown previously, no correlation exists between upper extremity strength measure and hand dominance in FSHD28, thus our results showed no reachable workspace difference between dominant and non-dominant sides.

Some of the limitations of this study were the small sample sizes, and in particular the limited number of individuals at the extremes of the FSHD combined subscale II+III scores (0,1 and 4,5). Due to the lack of adequate numbers of participants in all groups, subgroup statistical analysis was not undertaken. In all likelihood, this lack of individuals at the extremes of the combined upper extremity FSHD subscales may be due in part to either the natural distribution of severity phenotypes found in FSHD or an artifact of ceiling and floor effects of the FSHD clinical scale. Further studies with a larger sample size that encompasses the spectrum of phenotypes in FSHD will be helpful. In addition, studies need to be performed to determine the reliability of the system to measure changes over time and sensitivity to treatment.

CONCLUSIONS

This study demonstrates that this innovative approach to assessing upper extremity function by a reachable workspace outcome measure using a 3D vision-based sensor system is feasible in individuals with FSHD. Furthermore, these results suggest that the reachable workspace outcome measure displays adequate sensitivity to differentiate the varied upper extremity functional levels encountered in FSHD. A rationally-designed combination of upper extremity outcome measures including a region-specific global upper extremity outcome measure, such as the reachable workspace, complemented by targeted disease- or function-specific endpoints, may be optimal for future clinical efficacy trials. Continued progress in the development of innovative outcome measures will facilitate the overall therapeutic discovery process.

Acknowledgements

The research was supported in part by grant funds from the Center for Information Technology Research in the Interest of Society (CITRIS); National Science Foundation (NSF): #1111965; U.S. Department of Education (NIDRR): #H133B090001; and National Institutes of Health (NIH), NIAMS: U01 AR065113-01. We would like to thank the study participants for their time and effort; Craig McDonald, Erik Henricson, and Erica Goude Keller for project support; and research assistants Shakila Abdul, Michael Lee, Alex Egerter, and Ankit Mohla, for their help in preparing data for this manuscript.

ABBREVIATIONS

- 3D

Three-dimensional

- ADL

Activities of daily living

- ANOVA

Analysis of variance

- DASH

Disabilities of Arm, Shoulder, and Hand

- FSHD

Facioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy

- MMT

Manual muscle test

- MRC

Medical Research Council

- QMT

Quantitative muscle test

- RNA

Ribonucleic acid

- ROM

Range of motion

- RSA

Relative surface area

Footnotes

Disclosure:

Jay J. Han: serves as a consultant for Sanofi/Genzyme and co-founder of 5plus Inc.

Gregorij Kurillo: co-founder of 5plus Inc.

Richard T. Abresch: nothing to disclose.

Evan de Bie: nothing to disclose.

Alina Nicorici: nothing to disclose.

Ruzena Bajcsy: nothing to disclose.

REFERENCES

- 1.Tawil R. Facioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy. Neurotherapeutics. 2008 Oct;5(4):601–606. doi: 10.1016/j.nurt.2008.07.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Flanigan KM, Coffeen CM, Sexton L, Stauffer D, Brunner S, Leppert MF. Genetic characterization of a large, historically significant Utah kindred with facioscapulohumeral dystrophy. Neuromuscul Disord. 2001;11(6–7):525–529. doi: 10.1016/s0960-8966(01)00201-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mostacciuolo ML, Pastorello E, Vazza G, Miorin M, Angelini C, Tomelleri G, et al. Facioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy: epidemiological and molecular study in a north-east Italian population sample. Clin Genet. 2009;75(6):550–555. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.2009.01158.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.van Deutekom JC, Wijmenga C, van Tienhoven EA, Gruter AM, Hewitt JE, Padberg GW, et al. FSHD associated DNA rearrangements are due to deletions of integral copies of a 3.2 kb tandemly repeated unit. Hum Mol Genet. 1993;2:2037–2042. doi: 10.1093/hmg/2.12.2037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wijmenga C, Hewitt JE, Sandkuijl LA, Clark LN, Wright TJ, Dauwerse HG, et al. Chromosome 4q DNA rearrangements associated with facioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy. Nat Genet. 1992;2:26–30. doi: 10.1038/ng0992-26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Van der Maarel SM, Tawil R, Tapscott SJ. Facioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy and DUX4: breaking the silence. Trends Mol Med. 2011;17(5):252–258. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2011.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tawil R, Van Der Maarel SM. Facioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy. Muscle Nerve. 2006 Jul;34(1):1–15. doi: 10.1002/mus.20522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kilmer DD, Abresch RT, McCrory MA, Carter GT, Fowler WM, Jr, Johnson ER, et al. Profiles of neuromuscular diseases. Facioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 1995 Sep-Oct;74(5 Suppl):S131–S139. doi: 10.1097/00002060-199509001-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Statland JM, Tawil R. Facioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy: molecular pathological advances and future directions. Curr Opin Neurol. 2011 Oct;24(5):423–8. doi: 10.1097/WCO.0b013e32834959af. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wallace LM, Liu J, Domire JS, Garwick-Coppens SE, Guckes SM, Mendell JR, et al. RNA interference inhibits DUX4-induced muscle toxicity in vivo: implications for a targeted FSHD therapy. Mol Ther. 2012 Jul;20(7):1417–1423. doi: 10.1038/mt.2012.68. Epub 2012 Apr 17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Leung DG, Wagner KR. Therapeutic advances in muscular dystrophy. Ann Neurol. 2013 Sep;74(3):404–411. doi: 10.1002/ana.23989. Published online 2013 October 9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McDonald CM, Henricson EK, Abresch RT, Florence J, Eagle M, Gappmaier E, et al. The 6-minute walk test and other clinical endpoints in duchenne muscular dystrophy: reliability, concurrent validity, and minimal clinically important differences from a multicenter study. Muscle Nerve. 2013 Sep;48(3):357–368. doi: 10.1002/mus.23905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mendell JR, Rodino-Klapac LR, Sahenk Z, Roush K, Bird L, Lowes LP, et al. Eteplirsen for the treatment of Duchenne musculardystrophy. Ann Neurol. 2013 Nov;74(5):637–647. doi: 10.1002/ana.23982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.van der Ploeg AT, Clemens PR, Corzo D, Escolar DM, Florence J, Groeneveld GJ, et al. A randomized study of alglucosidase alfa in late-onset Pompe's disease. N Engl J Med. 2010 Apr 15;362(15):1396–1406. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0909859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bushby K, Connor E. Clinical outcome measures for trials in Duchenne muscular dystrophy: report from International Working Group meetings. Clin Investig (Lond) 2011 Sep;1(9):1217–1235. doi: 10.4155/cli.11.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mercuri E, Mayhew A, Muntoni F, Messina S, Straub V, Van Ommen GJ, et al. Towards harmonisation of outcome measures for DMD and SMA within TREAT-NMD; report of three expert workshops. Neuromuscul Disord. 2008 Nov;18(11):894–903. doi: 10.1016/j.nmd.2008.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bartels B, Pangalila RF, Bergen MP, Cobben NA, Stam HJ, Roebroeck ME. Upper limb function in adults with Duchenne muscular dystrophy. J Rehabil Med. 2011 Sep;43(9):770–775. doi: 10.2340/16501977-0841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Muntoni F. The development of antisense oligonucleotide therapies for Duchenne muscular dystrophy: report on a TREAT-NMD workshop hosted by the European Medicines Agency (EMA), on September 25th 2009. Neuromuscul Disord. 2010 May;20(5):355–362. doi: 10.1016/j.nmd.2010.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kurillo G, Han JJ, Abresch RT, Nicorici A, Yan P, Bajcsy R. Development and application of stereo camera-based upper extremity workspace evaluation in patients with neuromuscular diseases. PLoS One. 2012;7(9):e45341. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0045341. Epub 2012 Sep 17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Han JJ, Kurillo G, Abresch RT, Nicorici A, Bajcsy R. Validity, Reliability, and Sensitivity of a 3D Vision Sensor-based Upper Extremity Reachable Workspace Evaluation in Neuromuscular Diseases. PLoS Curr. 2013 Dec;12:5. doi: 10.1371/currents.md.f63ae7dde63caa718fa0770217c5a0e6. pii. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kurillo G, Han JJ, Obdržálek S, Yan P, Abresch RT, Nicorici A, et al. Upper extremity reachable workspace evaluation with Kinect. Stud Health Technol Inform. 2013;184:247–253. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kurillo G, Chen A, Bajcsy R, Han JJ. Evaluation of upper extremity reachable workspace using Kinect camera. Technol Health Care. 2013;21(6):641–656. doi: 10.3233/THC-130764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lamperti C, Fabbri G, Vercelli L, D'Amico R, Frusciante R, Bonifazi E, et al. A standardized clinical evaluation of patients affected by facioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy: The FSHD clinical score. Muscle Nerve. 2010;42:213–217. doi: 10.1002/mus.21671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sharpless JW. The nine hole peg test of finger hand co-ordination for the hemiplegic patient. In: Sharpless JW, editor. Mossman’s A Problem Oriented Approach to Stroke Rehabilitation. Springfield, Ill: Charles CT Thomas; 1982. pp. 420–423. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jebsen RH, Taylor N, Trieschmann RB, Trotter MJ, Howard LA. An objective and standardized test of hand function. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1969 Jun;50(6):311–319. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brooke M, Griggs R, Mendell J, Fenichel G, Shumate J, Pellegrino R. Clinical trial in Duchenne dystrophy. I. The design of the protocol. Muscle Nerve. 1981;4(no. 3):186–197. doi: 10.1002/mus.880040304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hudak PL, Amadio PC, Bombardier C. Development of an upper extremity outcome measure: the DASH (disabilities of the arm, shoulder and hand) [corrected]. The Upper Extremity Collaborative Group (UECG) Am J Ind Med. 1996 Jun;29(6):602–608. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0274(199606)29:6<602::AID-AJIM4>3.0.CO;2-L. Erratum in: Am J Ind Med 1996 Sep;30(3):372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Brouwer OF, Padberg GW, van der Ploeg RJ, Ruys CJ, Brand R. The influence of handedness on the distribution of muscular weakness of the arm in facioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy. Brain. 1992;115:1587–1598. doi: 10.1093/brain/115.5.1587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]