Abstract

Background

Parenteral opioids are used for pain relief in labour in many countries throughout the world.

Objectives

To assess the acceptability, effectiveness and safety of different types, doses and modes of administration of parenteral opioids given to women in labour.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group’s Trials Register (30 April 2011) and reference lists of retrieved studies.

Selection criteria

We included randomised controlled trials examining the use of intramuscular or intravenous opioids (including patient controlled analgesia) for women in labour. We looked at studies comparing an opioid with another opioid, placebo, other non-pharmacological interventions (TENS) or inhaled analgesia.

Data collection and analysis

At least two review authors independently assessed study eligibility, collected data and assessed risk of bias.

Main results

We included 57 studies involving more than 7000 women that compared an opioid with placebo, another opioid administered intramuscularly or intravenously or compared with TENS to the back. The 57 studies reported on 29 different comparisons, and for many outcomes only one study contributed data. Overall, the evidence was of poor quality regarding the analgesic effect of opioids, satisfaction with analgesia, adverse effects and harm to women and babies. There were few statistically significant results. Many of the studies had small sample sizes, and low statistical power. Overall findings indicated that parenteral opioids provided some pain relief and moderate satisfaction with analgesia in labour, although up to two-thirds of women who received opioids reported moderate or severe pain and/or poor or moderate pain relief one or two hours after administration. Opioid drugs were associated with maternal nausea, vomiting and drowsiness, although different opioid drugs were associated with different adverse effects. There was no clear evidence of adverse effects of opioids on the newborn. We did not have sufficient evidence to assess which opioid drug provided the best pain relief with the least adverse effects.

Authors’ conclusions

Parenteral opioids provide some relief from pain in labour but are associated with adverse effects. Maternal satisfaction with opioid analgesia was largely unreported but appeared moderate at best. This review needs to be examined alongside related Cochrane reviews examining pain management in labour. More research is needed to determine which analgesic intervention is most effective, and provides greatest satisfaction to women with acceptable adverse effects for mothers and their newborn.

Medical Subject Headings (MeSH): Analgesia, Obstetrical [*methods]; Analgesics, Opioid [*administration & dosage; adverse effects]; Injections, Intramuscular; Injections, Intravenous; Labor Pain [*drug therapy]; Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic

MeSH check words: Female, Humans, Pregnancy

BACKGROUND

This review is one in a series of Cochrane reviews examining pain management in labour. These reviews contribute to an overview of systematic reviews of pain management for women in labour (Jones 2011b) and share a generic protocol (Jones 2011a).

Description of the condition

Pain during labour is normal, being one of the few examples of pain which does not signal pathology or harm. This does not make the experience of pain any less, but it may alter the way pain is perceived, both by the woman in labour and those providing care.

Characteristics of labour pain

Pain during labour is intermittent, accompanying uterine contractions (Findley 1999). Characteristically the pain intensifies as the contraction increases, reaching a peak when the contraction is at its strongest, then diminishing as the uterus relaxes. Between contractions the uterus is at rest and there is usually no associated pain. As labour progresses the uterine contractions grow stronger, more frequent and longer lasting; at the same time they become more painful. Typically the strongest, most frequent, and most painful, uterine contractions occur at the end of the first stage of labour as the cervix reaches full dilatation. While the vast majority of women will describe at least some stages of labour as painful, the severity of reported pain varies considerably (Findley 1999).

Pain relief in labour - physiology and pain perceptions

Labour pain as perceived by women is a unique, subjective and complex neuro-hormonal phenomenon, which involves the interaction of physiological and psychological factors (Genesi 1998a; Genesi 1998b; Trout 2004). Several factors have been shown to reduce pain experienced by women in labour. These include continuous support of a caregiver, attendance of a birth companion and a relaxed birth environment (Hodnett 2002). Two other key determinants that may influence the pain level that a woman experiences are feeling in control of her behaviour, and the care she receives. The extent to which a woman can actively participate in negotiating the care she receives has also been linked to overall maternal satisfaction with the childbirth experience (Green 2003; Hodnett 2002). The degree to which a woman is satisfied with the birth experience is not, therefore, solely associated with the pain felt. Having more control will foster a woman’s sense of self-belief and confidence in her capacity to labour and give birth, which will also affect her pain perception (Lowe 1993; Lowe 1996). From the clinical point of view, the management of pain during labour involves much more than simply the provision of a pharmacological intervention. Related Cochrane reviews have demonstrated the value of continuous support, midwifery models and non-pharmacological approaches to managing pain in labour (Barragán 2011; Cluett 2009; Dowswell 2009; Hatem 2008; Hodnett 2007; Hunter 2007).

A caregiver’s perception of a woman’s labour pain may be different from what the woman is actually experiencing (Callister 1995). A large UK survey that collected maternal and midwifery assessments of pain relief found that midwives rated pethidine more positively than the women who received it (Chamberlain 1993). Practitioners’ attitudes to maternal pain vary (Leap 2004), wherein some adopt a rescue position to relieve the pain and recommend the use of analgesia, whilst others facilitate the woman to optimise coping mechanisms, using strategies involving breathing and/or relaxation techniques and positions that offer her more comfort. Women’s attitudes towards, and preferences for, intrapartum pain relief vary widely. Whilst some women prefer to labour without the use of pharmacological analgesia, others opt, for example, to use epidural analgesia throughout labour. Good communication and sensitive support from caregivers improves a woman’s experience of labour, and her overall satisfaction with care, regardless of her choice of pain relief or levels of reported pain (Hodnett 2002). It is important that decisions for coping with the pain of labour are based on informed choice (Green 2003; Hawkins 2003).

Pain relief in labour - the use of opioids

The use of pain-relieving drugs during labour is now standard care in many countries throughout the world (Findley 1999; Reynolds 2000). The extent of usage of parenteral opioids during labour is unclear; however, most obstetric units in developed countries offer intramuscular opioids, along with facilities for epidural analgesia. Opioids are relatively inexpensive, and use of the opioid drugs pethidine, meptazinol or diamorphine during labour is common midwifery and obstetric practice in some countries. In other parts of the world, parenteral opioids commonly used in labour include morphine, nalbuphine, fentanyl and more recently remifentanil (Evron 2007). Worldwide, pethidine is the most commonly used opioid (Bricker 2002). In the UK, a midwife can take responsibility for giving a woman an intramuscular injection of either pethidine or diamorphine, without a prescription from a medical practitioner, whether she is working in the hospital or community care setting (MHRA 2007).

In the UK, estimates for opioid use showed that 34% of women overall used pethidine or another opioid during labour, with variation between NHS Hospital Trusts between 5% and 66% (Healthcare Commission 2007). A survey of 4800 women reported that 32.9% used pethidine or another opioid, and 10.5% of these women also had an epidural (Redshaw 2007). The use of an opioid varied by parity, with more nulliparae reporting use (with or without an epidural) compared with multiparous women. Use of pethidine in the UK has declined from 42% in 1995 to 33% in 2006, yet the proportion of women who received an epidural has changed little over this time period: 27% in 1995 and 28% in 2006 (Redshaw 2007). In the USA, 39% to 56% of women received an opioid during labour (Hawkins 1999). Studies in New Zealand and the UK have revealed that more than 95% of hospitals surveyed routinely offered intramuscular pethidine (Lee 2004; Saravanakumar 2007). In the UK study, approximately half (49%) of the units surveyed offered patient-controlled intravenous opioid analgesia for use in labour (Saravanakumar 2007).

Some maternity practitioners have voiced concerns about the use of parenteral opioid analgesia during labour. These centre on doubt about analgesic effectiveness, and anxiety about the sedative effects on women and babies. Concerns relating to maternal outcomes include an impaired capacity to engage in decision making about care, nausea and/or vomiting, and the slowing down of gastric emptying, which increases the risk of inhalation of gastric contents should a general anaesthetic be required in an emergency situation. If a woman feels drowsy or sedated, she is less likely to mobilise and adopt an upright position, and as a result this may lengthen her labour, and make it more painful (Lawrence 2009).

Effects on the baby

Opioids readily cross the placenta by passive diffusion. It is estimated that it can take a newborn three to six days to eliminate pethidine, and its metabolite, norpethidine, from its system (Hogg 1977). Pethidine has been shown to significantly affect fetal heart rate variability, accelerations and decelerations during labour (Sekhavat 2009; Solt 2002). Changes in normal fetal heart indices have consequences for the woman. She will be required to have electronic fetal heart rate monitoring (EFM) if she is in hospital, and transfer to hospital if she is in a community setting. Results from observational studies have reported effects of opioids on the newborn that include inhibited sucking at the breast and decreased alertness, resulting in delayed effective breastfeeding (Nissen 1995; Ransjo-Arvidson 2001; Righard 1990).

Why it is important to do this review

This review evaluates effects of parenteral opioids for analgesia in labour. The use of intramuscular injection of opioid analgesia in labour became a traditional part of midwifery practice without evidence from randomised controlled trials for its analgesic effectiveness, impact on labour outcomes or acceptability to women. It is thought its perceived analgesic efficacy may be due, at least in part, to its sedative effects rather than a true reduction in perceived pain (NICE 2007). There remains uncertainty amongst practitioners as to which opioid provides the most effective pain relief, and whether opioids used during labour are acceptable to women. The most effective and acceptable mode of administration also remains unknown. In addition, there are concerns about the potential adverse effects associated with the use of opioids in labour, particularly the effects on the newborn in relation to infant feeding.

At present, the choice of opioid for analgesia in labour depends on what is available in different hospitals. However, no matter what facilities and drugs are available, women often have no choice as to which drug is used, and healthcare professionals have little information to guide decision-making. Whilst there have been previous reviews on this topic (Bricker 2002; Elbourne 2006) this review provides an up-to-date summary of existing knowledge. We aim to provide best evidence to facilitate discussions between maternity practitioners and women to enable them to make informed decisions about their choice of analgesia during labour.

OBJECTIVES

To assess the effectiveness, safety and acceptability to women of different types, doses and modes of administration of parenteral opioid analgesia in labour. A second objective is to assess the effects of opioids in labour on the baby in terms of safety, condition at birth and early feeding.

METHODS

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Randomised controlled trials. We did not include quasi-randomised trials. We included studies presented only in abstracts provided that there was enough information to allow us to assess eligibility and risk of bias; if there was insufficient information we attempted to contact study authors.

Types of participants

Women in labour. We have excluded studies focusing specifically and exclusively on women in high-risk groups, or women in premature labour (before 37 weeks’ gestation), but have included studies which include such women as part of a broader sample.

Types of interventions

Parenteral opioids (intramuscular and intravenous drugs, including patient controlled analgesia).

Drugs for comparison include pethidine or meperidine, nalbuphine, butorphanol, diamorphine, buprenorphine, meptazinol, pentazocine, tramadol, alfentanil, sufentanil, remifentanil and fentanyl.

The following comparisons were eligible for the review.

An opioid versus placebo using the same route of administration.

An opioid versus another opioid using the same route of administration.

An opioid plus an add-on drug versus another opioid plus the same add-on drug using the same route of administration.

One opioid versus the same opioid but a different dose.

We planned to use trialists’ definitions of higher and lower doses of the same drugs, as high and low doses are different for different opioids.

Where different doses of the same drug were compared with the same comparator (e.g. 40 mg pethidine versus placebo, and 80 mg pethidine versus placebo), we planned to use subgroup analyses to examine findings.

This review is one in a series of Cochrane reviews examining pain management in labour. These reviews contribute to an overview of systematic reviews of interventions for pain management in labour (Jones 2011b), and share a generic protocol (Jones 2011a). To avoid duplication, the different methods of pain management have been listed in a specific order, from one to 15. Individual reviews focusing on particular interventions include comparisons with only the intervention above it on the list. Methods of pain management identified in the future will be added to the end of the list. The current list is as follows.

Placebo/no treatment

Hypnosis

Biofeedback (Barragán 2011)

Intracutaneous or subcutaneous sterile water injection (Derry 2011)

Immersion in water (Cluett 2009)

Aromatherapy (Smith 2011b)

Relaxation techniques (yoga, music, audio)

Acupuncture or acupressure (Smith 2011a)

Manual methods (massage, reflexology)

Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) (Dowswell 2009)

Inhaled analgesia

Opioids (this review)

Non-opioid drugs (Othman 2011)

Local anaesthetic nerve blocks (Novikova 2011)

Epidural (including combined spinal epidural) (Anim-Somuah 2005; Simmons 2007)

Accordingly, this review includes comparisons of an opioid with: 1. placebo/no treatment; 2. hypnosis; 3. biofeedback; 4. intracutaneous or subcutaneous sterile water injection; 5. immersion in water; 6. aromatherapy; 7. relaxation techniques (yoga, music, audio); 8. acupuncture or acupressure; 9. manual methods (massage, reflexology); 10. TENS; 11. inhaled analgesia; or 12. another opioid (as specified above).

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

Maternal satisfaction with analgesia measured during labour.

Maternal satisfaction with analgesia in labour measured during the postnatal period.

Secondary outcomes

For women

Maternal pain score or pain measured in labour.

Additional analgesia required: epidural.

Maternal sleepiness during labour.

Nausea and vomiting in labour.

Caesarean section.

Assisted vaginal birth.

Postpartum haemorrhage (as defined by the trial authors).

Breastfeeding at discharge.

Breastfeeding in the postnatal period (four to six weeks).

Sense of control in labour (as defined by trialists).

Satisfaction with childbirth experience (as defined by trialists).

Effect (negative) on mother/baby interaction.

For babies

Fetal heart rate changes in labour (persistent decelerations or tachycardia).

Naloxone administration.

Neonatal resuscitation.

Apgar score less than seven at one minute.

Apgar score less than seven at five minutes.

Apgar score less than seven at ten minutes.

Admission to special care baby unit/neonatal intensive care unit (as defined by trialists).

Newborn neuro-behavioural scores.

Neurodevelopment outcomes during infancy.

Other

Cost (as defined by trialists).

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

We contacted the Trials Search Co-ordinator to search the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group’s Trials Register (30 April 2011).

The Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group’s Trials Register is maintained by the Trials Search Co-ordinator and contains trials identified from:

quarterly searches of the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL);

weekly searches of MEDLINE;

weekly searches of EMBASE;

handsearches of 30 journals and the proceedings of major conferences;

weekly current awareness alerts for a further 44 journals plus monthly BioMed Central email alerts.

Details of the search strategies for CENTRAL, MEDLINE and EMBASE, the list of handsearched journals and conference proceedings, and the list of journals reviewed via the current awareness service can be found in the ‘Specialized Register’ section within the editorial information about the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group.

Trials identified through the searching activities described above are each assigned to a review topic (or topics). The Trials Search Co-ordinator searches the register for each review using the topic list rather than keywords.

Searching other resources

We searched the reference lists of background review articles and the reference lists of papers retrieved by the search described above. We did not apply any language restrictions.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Four review authors (R Ullman, T Dowswell, L Smith, E Burns) independently assessed for inclusion all the studies identified as a result of the search strategy. Two authors assessed each report and we resolved any disagreement through discussion or, if required, we consulted a third author.

Data extraction and management

We designed a form to collect data. For each report, two review authors independently collected the data using the agreed form (all review authors were involved in data collection). We resolved discrepancies through discussion or, if required, we consulted a third author. We entered data into Review Manager software (RevMan 2011) and checked them for accuracy.

When information in trial reports was unclear, we attempted to contact authors of the original reports to provide further details.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two review authors independently assessed risk of bias for each included study using the criteria described in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011) and outlined below. We resolved any disagreement by discussion, or by involving a third assessor.

(1) Random sequence generation (checking for possible selection bias)

We described for each included study the method used to generate the allocation sequence in sufficient detail to allow an assessment of whether it should produce comparable groups.

We will assessed the method as:

low risk of bias (any truly random process, e.g. random number table; computer random number generator);

high risk of bias (any non-random process, e.g. odd or even date of birth; hospital or clinic record number); or

unclear risk of bias.

(2) Allocation concealment (checking for possible selection bias)

We described for each included study the method used to conceal allocation to interventions prior to assignment and assessed whether intervention allocation could have been foreseen in advance of, or during recruitment, or changed after assignment. We assessed the methods as:

low risk of bias (e.g. telephone or central randomisation; consecutively numbered sealed opaque envelopes);

high risk of bias (open random allocation; unsealed or non-opaque envelopes, alternation; date of birth);

unclear risk of bias.

(3.1) Blinding of participants and personnel (checking for possible performance bias)

We described for each included study the methods used, if any, to blind study participants and personnel from knowledge of which intervention a participant received. We considered studies to be at low risk of bias if they were blinded, or if judged that the lack of blinding would be unlikely to affect results. We assessed blinding separately for different outcomes or classes of outcomes.

We assessed the methods as:

low, high or unclear risk of bias for participants;

low, high or unclear risk of bias for personnel;

(3.2) Blinding of outcome assessment (checking for possible detection bias)

We described for each included study the methods used, if any, to blind outcome assessors from knowledge of which intervention a participant received. We assessed blinding separately for different outcomes or classes of outcomes.

We assessed methods used to blind outcome assessment as:

low, high or unclear risk of bias.

(4) Incomplete outcome data (checking for possible attrition bias due to the amount, nature and handling of incomplete outcome data)

We described for each included study, and for each outcome or class of outcomes, the completeness of data including attrition and exclusions from the analysis. We stated whether attrition and exclusions were reported, the numbers included in the analysis at each stage (compared with the total randomised participants), reasons for attrition or exclusion where reported, and whether missing data were balanced across groups or were related to outcomes:

low risk of bias (e.g. no missing outcome data; missing outcome data balanced across groups);

high risk of bias (e.g. numbers or reasons for missing data imbalanced across groups; ‘as treated” analysis done with substantial departure of intervention received from that assigned at randomisation);

unclear risk of bias.

(5) Selective reporting (checking for reporting bias)

We described for each included study how we investigated the possibility of selective outcome reporting bias and what we found. We assessed the methods as:

low risk of bias (where it is clear that all of the study’s prespecified outcomes and all expected outcomes of interest to the review have been reported);

high risk of bias (where not all the study’s prespecified outcomes have been reported; one or more reported primary outcomes were not prespecified; outcomes of interest are reported incompletely and so cannot be used; study fails to include results of a key outcome that would have been expected to have been reported);

unclear risk of bias.

(6) Other bias (checking for bias due to problems not covered by (1) to (5) above)

We describe for each included study any important concerns we have about other possible sources of bias, for example was there a potential source of bias related to the specific study design? Was the trial stopped early due to some data-dependent process? Was there extreme baseline imbalance? Has the study been claimed to be fraudulent?

We assessed whether each study was free of other problems that could put it at risk of bias:

low risk of other bias;

high risk of other bias;

unclear whether there is risk of other bias.

(7) Overall risk of bias

We made explicit judgements about whether studies were at high risk of bias, according to the criteria given in the Handbook (Higgins 2011). With reference to (1) to (6) above, we assessed the likely magnitude and direction of the bias and whether we considered it likely to impact on the findings. We aimed to explore the impact of the level of bias through undertaking sensitivity analyses - see Sensitivity analysis.

Measures of treatment effect

We carried out statistical analysis using Review Manager software (RevMan 2011). We used fixed-effect meta-analysis for combining data where trials examined the same intervention, and where we judged the trials’ populations and methods to be sufficiently similar. Where we suspected clinical or statistical heterogeneity between studies, sufficient to suggest that treatment effects might differ between trials, we carried out random-effects meta-analysis.

Dichotomous data

For dichotomous data, we have presented results as summary risk ratio with 95% confidence intervals.

Continuous data

For continuous data, we have used the mean difference if outcomes were measured in the same way (e.g. using the same pain scale) between trials. We used the standardised mean difference to combine trials that measured the same outcome, but used different scales.

Unit of analysis issues

Cluster-randomised trials

We intended to include cluster-randomised trials in the analyses along with individually randomised trials using the methods described in the Handbook (Higgins 2011). Their sample sizes would be adjusted using an estimate of the intracluster correlation coefficient (ICC) derived from the trial (if possible), or from another source. If we used ICCs from other sources, we would report this and conduct sensitivity analyses to investigate the effect of variation in the ICC. If we had identified both cluster-randomised trials and individually randomised trials, we planned to synthesise the relevant information. We would consider it reasonable to combine the results from both if there was little heterogeneity between the study designs and the interaction between the effect of intervention and the choice of randomisation unit was considered to be unlikely.

Crossover trials

We did not include crossover trials.

Dealing with missing data

For included studies, we noted levels of attrition. We planned to explore the impact of including studies with high levels of missing data (more than 10% for outcomes where data were collected in labour) in the overall assessment of treatment effect by using sensitivity analyses.

Where data were not reported for some outcomes or groups, we attempted to contact the study authors for further information. We analysed data on all participants with available data in the group to which they were allocated, regardless of whether or not they received the allocated intervention. If in the original reports participants were not analysed in the group to which they were randomised, and there was sufficient information in the trial report, we attempted to restore them to the correct group.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We examined heterogeneity between trials using the T2 and I2 statistics. If we identified heterogeneity among the trials, we planned to explore it by prespecified subgroup analysis provided data were available to do this, and by performing sensitivity analysis. Where we thought that an average treatment effect was clinically meaningful, we used a random-effects model for meta-analysis in the presence of moderate or high levels of heterogeneity (I2 greater than 30%), and for these outcomes we have reported I2, T2, the P value for the Chi2 test for heterogeneity.

Assessment of reporting biases

Where we suspected reporting bias (see ’Selective reporting bias’ above), we attempted to contact study authors asking them to provide missing outcome data. We were not able to explore possible publication bias by using funnel plots, as too few studies were included in each comparison.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We intended to conduct planned subgroup analysis using the methods described by Deeks 2001 and set out in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews (Higgins 2011).

We had planned to carry out the following subgroup analyses.

By parity (nulliparous versus multiparous women).

By spontaneous versus induced or augmented labour.

Term versus preterm birth.

Continuous support in labour versus no continuous support.

Where different doses of the same drug were examined (e.g. pethidine 40 mg or pethidine 80 mg versus a placebo), we separated analyses into subgroups to examine the impact of different doses. For fixed-effect and random-effects meta-analyses we planned to assess differences between subgroups by inspection of the subgroups’ confidence intervals: non-overlapping confidence intervals indicating a statistically significant difference in treatment effect between the subgroups.

Sensitivity analysis

We planned to carry out sensitivity analyses to explore the effect of trial quality for important outcomes in the review. Where there was risk of bias associated with a particular aspect of study quality (e.g. inadequate allocation concealment), we have explored this by sensitivity analyses.

RESULTS

Description of studies

See: Characteristics of included studies; Characteristics of excluded studies.

Results of the search

Using the search strategy, in an earlier version of this review, we identified 165 papers representing 138 studies. For this updated version we identified a further five studies (Castro 2004; El-Kerdawy 2010; Solek-Pastuszka 2009; Tawfik 1982; Thakur 2004) and an additional published report for a study which was ongoing when the earlier review was completed (Douma 2010). Following the updated search we excluded three of these studies (Castro 2004; El-Kerdawy 2010; Solek-Pastuszka 2009) and included three (Douma 2010; Tawfik 1982; Thakur 2004). In this update we have included 57 studies and excluded 86.

Included studies

We included 57 studies involving more than 7000 women (see Characteristics of included studies).

Most of the studies included in the review examined an opioid drug administered intramuscularly (IM) and compared either an opioid with placebo, or with another opioid. A smaller number of studies examined opioid drugs administered intravenously (IV), sometimes with a degree of patient control over the amount of drug infused (PCA). None of the included studies examined subcutaneous administration of opioids. Some of the studies compared opioids with other non-pharmacological interventions such as TENS (three studies). Trials with more than two arms may be included in more than one comparison.

IM comparisons

IM pethidine versus IM placebo (three studies) (Kamyabi 2003; Sliom 1970; Tsui 2004).

IM meptazinol versus IM pethidine (eight studies) (De Boer 1987; Jackson 1983; Morrison 1987; Nel 1981; Nicholas 1982; Osler 1987; Sheikh 1986; Wheble 1988). (In the studies by De Boer 1987 and Jackson 1983, women in both study groups also received add-on drugs.).

IM meptazinol versus IM pethidine PCA administration (one study) (Li 1988).

IM diamorphine versus IM pethidine (both groups had prochlorperazine) (Fairlie 1999).

IM tramadol versus IM pethidine (seven studies) (Bitsch 1980; Fieni 2000; Husslein 1987; Keskin 2003; Khooshideh 2009; Prasertsawat 1986; Viegas 1993).

In an additional study comparing tramadol with pethidine, both groups also had triflupromazine (Kainz 1992).

IM dihydrocodeine versus IM pethidine (Sliom 1970).

IM pentazocine versus IM pethidine (six studies) (Borglin 1971; Duncan 1969; Levy 1971; Moore 1970; Mowat 1970; Refstad 1980).

IM Pentazocine + promazine versus IM pethidine + promazine (Refstad 1980).

IM nalbuphine versus IM pethidine (four studies) (Lardizabal 1999; Lisboa 1997; Mitterschiffthaler 1991; Wilson 1986).

IM phenazocine versus IM pethidine (Grant 1970).

IM morphine versus pethidine (one study) (Prasertsawat 1986).

IM butorphanol versus IM pethidine (Maduska 1978).

IM tramadol versus no treatment (one study) (Li 1994).

One study compared a spasmolytic drug (Avacan ®) with IM pentazocine (Hamann 1972).

IM pentazocine versus IM Pethilorphan® (O’Dwyer 1971).

We were unable to include data from the following comparisons because of a lack of information in the reports of the studies. IM buprenorphine versus IM pethidine (Tharamas 1999).

A four-arm trial by Wahab 1988 compared nalbuphine, butorphanol, pentazocine and a placebo.

IV comparisons

-

17

IV fentanyl versus IV pethidine (one study) (Rayburn 1989).

-

18

IV nalbuphine versus IV pethidine (one study) (Giannina 1995).

-

19

IV phenazocine versus IV pethidine (one study) (Olson 1964).

-

20

IV butorphanol versus IV pethidine (three studies) (Hodgkinson 1979; Nelson 2005; Quilligan 1980).

-

21

IV morphine versus IV pethidine (two studies) (Campbell 1961; Olofsson 1996).

-

22

IV alphaprodine (nisentil) versus IV pethidine (one study) (Gillam 1958).

-

23

IV fentanyl versus butorphanol (one study) (Atkinson 1994).

IV pethidine versus no treatment (one study) (Neumark 1978). (We were unable to use data from this study for this comparison in the review. See Characteristics of included studies tables.)

IV/PCA comparisons

-

24

PCA pentazocine versus PCA pethidine (one study) (Erskine 1985).

-

25

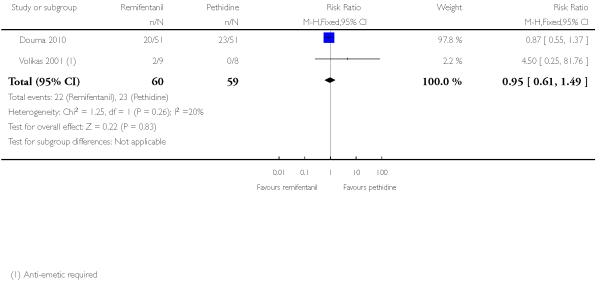

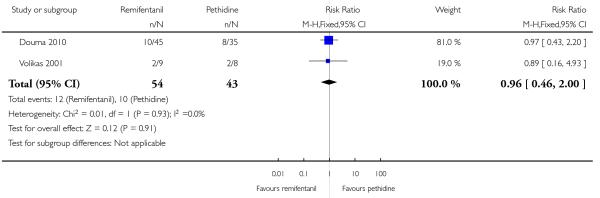

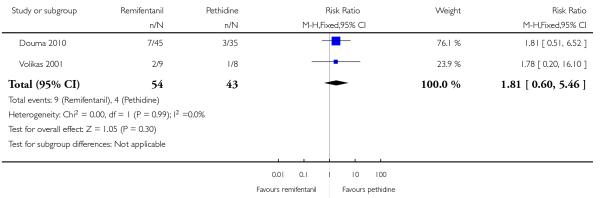

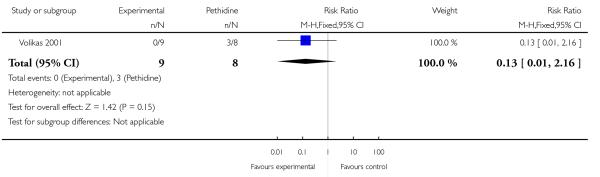

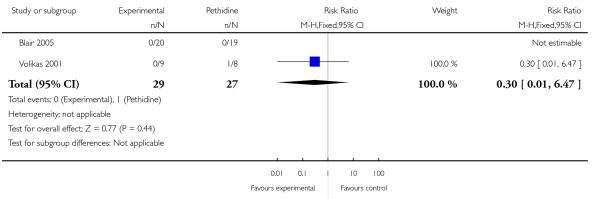

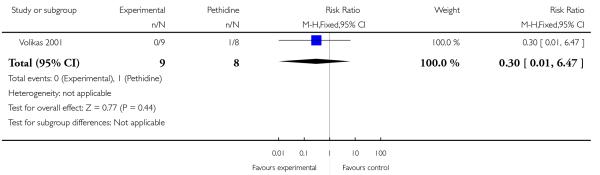

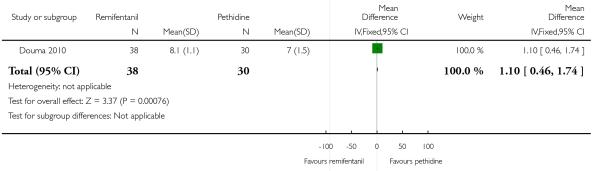

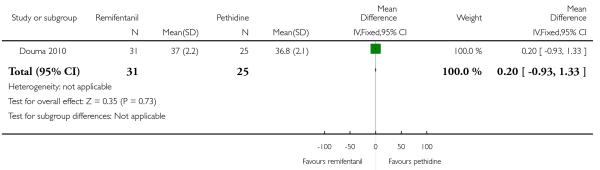

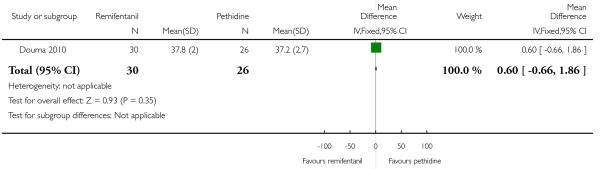

PCA remifentanil versus PCA pethidine (three studies) (Blair 2005; Douma 2010; Volikas 2001).

-

26

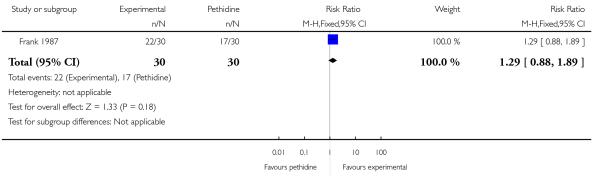

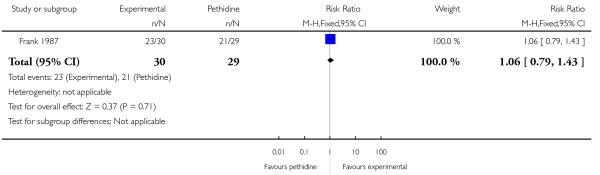

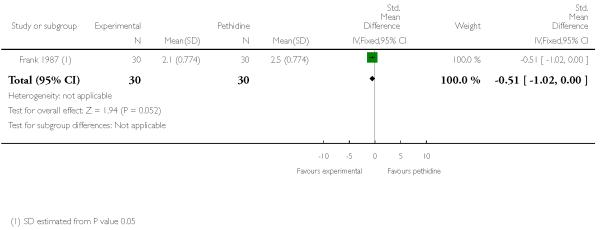

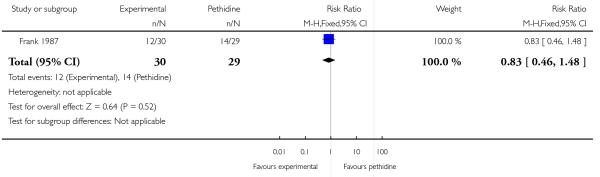

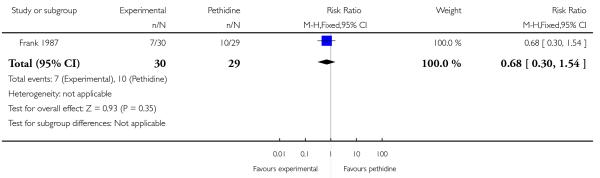

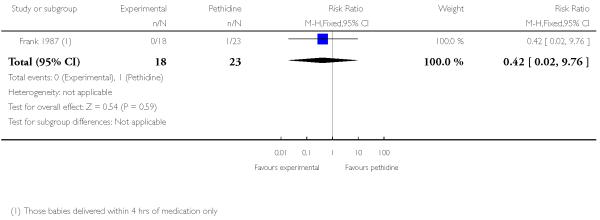

PCA nalbuphine versus PCA pethidine (one study) (Frank 1987).

-

27

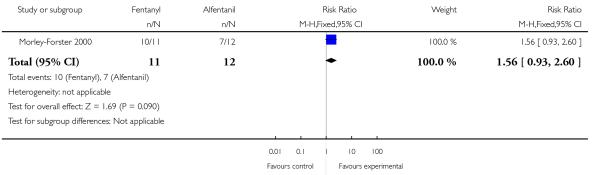

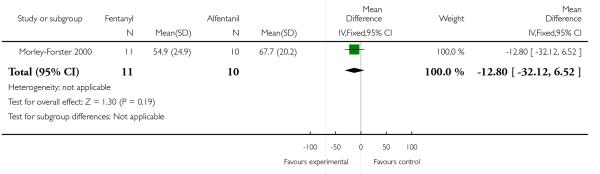

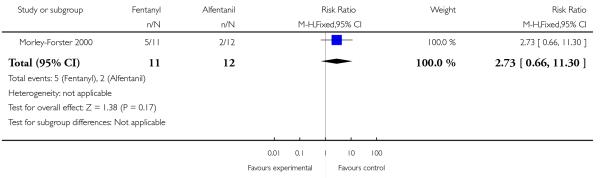

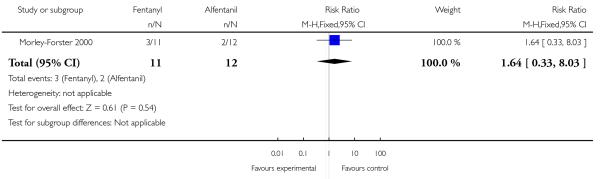

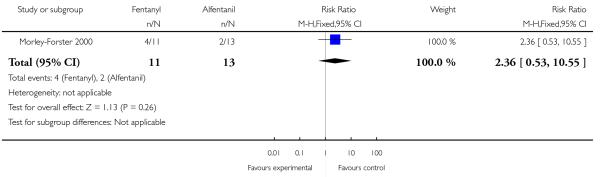

PCA fentanyl versus PCA alfentanil (one study) (Morley-Forster 2000).

-

28

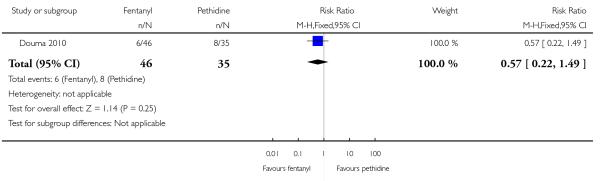

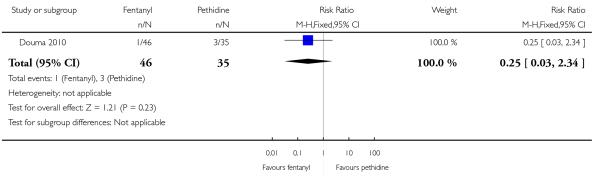

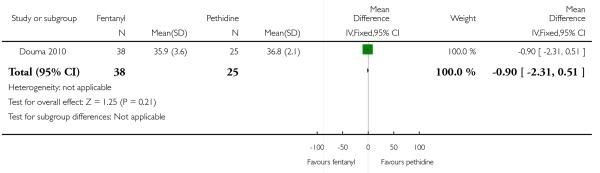

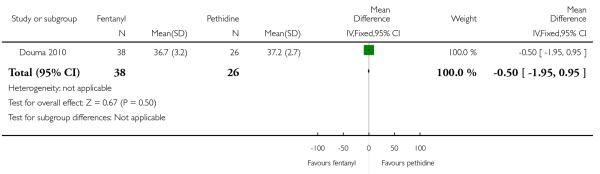

PCA fentanyl versus PCA pethidine (one study) (Douma 2010).

Opioids versus TENs

-

29

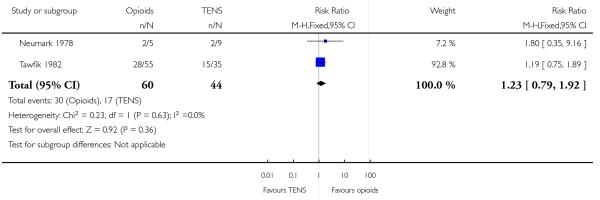

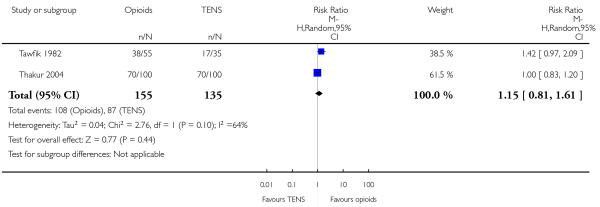

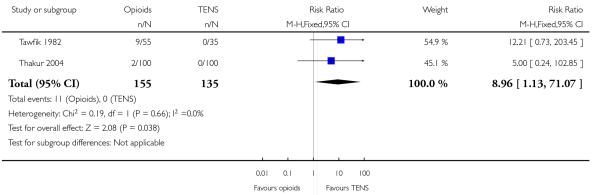

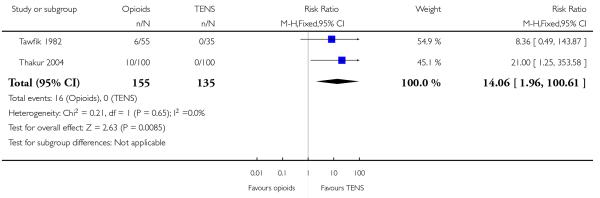

IV pethidine (50 mg) versus TENS to lower back (Neumark 1978), IM pethidine (50 mg) versus TENS to back (Tawfik 1982), IM tramadol (100 mg) versus TENS to back (Thakur 2004).

Excluded studies

We have excluded 86 studies (see Characteristics of excluded studies).

Reasons for exclusions (some of the studies were excluded for more than one reason).

In 16 studies the focus was on epidural analgesia (Camann 1992; Evron 2007; Evron 2008; El-Kerdawy 2010; Gambling 1998; Ginosar 2003; Grandjean 1979; McGrath 1992; Morris 1994; Nafisi 2006; Polley 2000, Rabie 2006; Solek-Pastuszka 2009; Volmanen 2008; Wiener 1979; Wong 2005). The use of epidural analgesia for pain management in labour is covered in related Cochrane reviews (Anim-Somuah 2005; Simmons 2007).

In 13 studies, women in both groups received the same opioid and the focus of studies was on add-on drugs; so, for example, both groups received pethidine with one group, in addition, receiving a sedative. The focus of these trials was on the effects of the add-on drug (Aiken 1971; Ballas 1976; De Lamerens 1964; Hodgkinson 1978; Malkasian 1967; McQuitty 1967; Posner 1960; Powe 1962; Ron 1984; Roberts 1960; Spellacy 1966; Wan 1965; Williams 1962).

Eighteen studies were not randomised trials, or it was not clear that there was any random allocation to groups (Balcioglu 2007; Bredow 1992; Brelje 1966; Callaghan 1966; Cincadze 1978; Cullhed 1961; Eliot 1975; MacVicar 1960; Moore 1974; Pandole 2003; Rowley 1963; Savage 1955; Singh 2001; Soontrapa 2002; Suvonnakote 1986; Tripti 2006; Vavrinkova 2005; Volmanen 2005).

In three studies it was not clear that participants were in labour (Chang 1976; Krins 1969; Tomlin 1965).

In the study by Bare 1962 women did not receive an opioid.

In the study by Kaltreider 1967 the focus was on a high-risk group (women in preterm labour) and post-randomisation exclusions meant that results were difficult to interpret.

We excluded two studies as levels of attrition meant that results were at high risk of bias. There were serious methodological problems in the study by Robinson 1980 and complete data were available for only approximately one-third of those randomised. In the study by De Kornfeld 1964, data on pain outcomes were available for less than half the sample at one hour; results from this study were therefore very difficult to interpret.

Five trials were reported in trial registers or in brief abstracts and we were unable to assess risk of bias or extract results. We attempted to contact authors for more information without success (Goodlin 1988, Kalaskar 2007; Morgan 2004; Overton 1992; Taskin 1993).

The focus of four studies was not on pain relief, so women may have received an opioid with the purpose of promoting progress in labour (Sosa 2004; Tournaire 1980; Treisser 1981; Von Vorherr 1963). In one of these studies women were specifically excluded if they complained of pain (Sosa 2004), and in another, women in the two groups also received oxytocin with each study group receiving a different dose (Von Vorherr 1963). A further two studies did not focus on pain relief but rather on newborn serum bilirubin (McDonald 1964) or platelet function (Greer 1988).

Seven studies focused on drugs no longer in use, or drugs not used nowadays for obstetric analgesia (Cahal 1960; Cavanagh 1966; Eames 1964; Ransom 1966; Roberts 1957; Sentnor 1966; Walker 1992).

In five studies the same opioid was given to women in both arms of trials and the difference between groups was mode of administration; different modes of administration of parenteral opioids will be considered in a separate Cochrane review (Balki 2007; Isenor 1993; McInnes 2004; Rayburn 1989; Rayburn 1991).

In two studies women in one arm of the trial, as well as receiving an opioid, were also given another add-on drug that the comparison group did not receive. In these studies results are difficult to interpret, as any differences between groups may be due to the add-on drug rather than the opioid (Busacca 1982; Calderon 2006).

In the studies by Calderon 2006, Evron 2005, Li 1995, Nikkola 2000; Shahriari 2007 and Thurlow 2002, different drugs were administered using different methods, and so it is difficult to interpret results as any differences between groups may be due to drug, method or both together.

In one study the effect of the opioid analgesia was not assessed during childbirth, but for second trimester labour following termination of pregnancy (Castro 2004).

Risk of bias in included studies

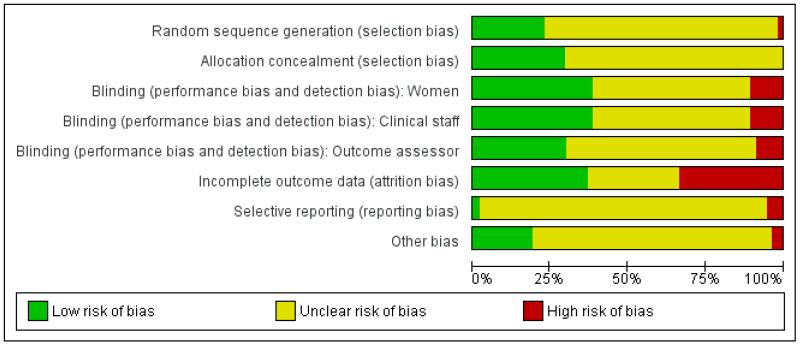

Figure 1. Risk of bias graph: review authors’ judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

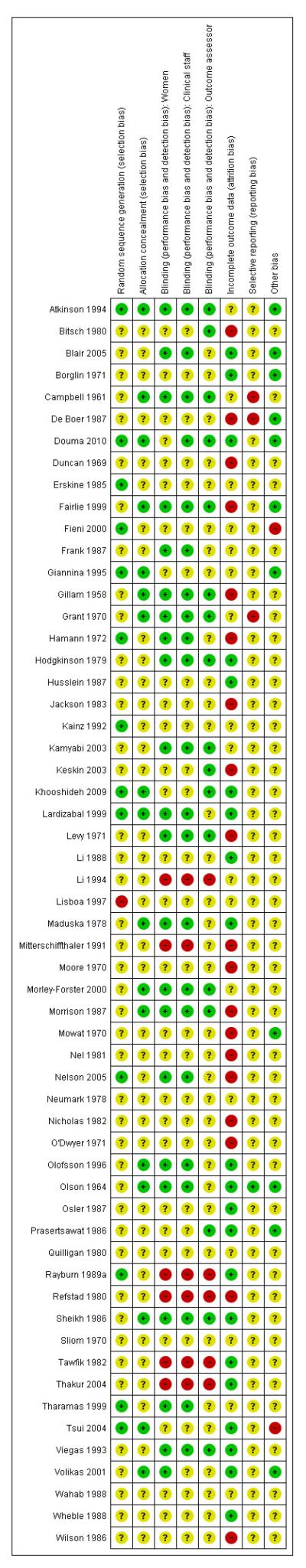

Figure 2. Risk of bias summary: review authors’ judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Allocation

Sequence generation

In eight studies, authors stated that a computer-generated random sequence was used (Atkinson 1994; Douma 2010; Fieni 2000; Giannina 1995; Khooshideh 2009; Lardizabal 1999; Nelson 2005; Tsui 2004); in two that an external randomisation service was used (Morley-Forster 2000; Rayburn 1989a); and in four studies that random number tables were consulted (Erskine 1985; Hamann 1972; Kainz 1992; Tharamas 1999). The majority of included studies did not give clear information about how the randomisation sequence was generated.

Allocation concealment

Allocation concealment was not generally described in sufficient detail to allow assessment of risk of bias; it was not always clear at what stage randomisation took place, and whether or not the person carrying out randomisation was aware of group allocation. Four studies described using numbered opaque sealed envelopes to conceal allocation (Giannina 1995; Khooshideh 2009; Tsui 2004; Volikas 2001). Seventeen studies described using identical coded drug boxes (although it may not have been clear who had access to the code or when the code was broken) (Atkinson 1994; Borglin 1971; Campbell 1961; Douma 2010; Fairlie 1999; Gillam 1958; Grant 1970; Lardizabal 1999; Levy 1971; Maduska 1978; Moore 1970; Morley-Forster 2000; Morrison 1987; Olofsson 1996; Olson 1964; Sheikh 1986; Wilson 1986). In the remaining studies it was not clear what steps were taken to conceal allocation at the point of randomisation.

Blinding

Many of the studies were described as double blind; in the majority of these trials women in the control arms were given preparations of similar appearance to those given to women in the experimental arms (either a placebo or an indistinguishable comparison drug). It was not always clear that blinding was effective; for example, some IM drugs may appear similar, but different consistencies may be apparent to experienced staff. It was also not generally clear at what point blinding ended, and whether outcome assessors were blind to group allocation.

In six studies blinding was impractical as women were given different types of treatment (e.g. IM drug versus no treatment; IM drug versus TENS) (Li 1994; Neumark 1978; Rayburn 1989a; Refstad 1980; Tawfik 1982; Thakur 2004), and in a further nine studies methods were not described or were not clear (Bitsch 1980; Erskine 1985; Fieni 2000; Giannina 1995; Husslein 1987; Keskin 2003; Lisboa 1997; Mitterschiffthaler 1991; Wahab 1988).

Incomplete outcome data

Assessing levels of attrition was very difficult in these studies, as denominators were frequently absent from results tables. In addition, even where all women appeared to be accounted for at follow-up, there were frequently missing data for specific outcomes. In some studies loss to follow-up or missing data were greater than 10% (Bitsch 1980; Fairlie 1999; Hamann 1972; Levy 1971; Moore 1970; Mowat 1970; Olson 1964; Wilson 1986), or greater than 20% (De Boer 1987; Frank 1987; Giannina 1995; Gillam 1958; Nicholas 1982; O’Dwyer 1971; Refstad 1980).

In several studies there were missing data on pain outcomes. This may have occurred because drugs were given at a late stage in labour, so that women had already given birth before the first scheduled pain assessment. For example, in Fairlie 1999 17%, and in O’Dwyer 1971 and Refstad 1980 more than one-third of women had given birth within an hour of drug administration.

In some studies women were explicitly excluded from the analysis because of factors that may have related to study medication; in Hamann 1972 13% were excluded after randomisation because they had a long labour or a caesarean section, and in Moore 1970 women were excluded because they had had additional pain relief. Wilson 1986 excluded 10% of the sample because women reported that they had had inadequate pain relief. In the study by Nelson 2005 any woman undergoing artificial rupture of membranes, commencing oxytocin or requesting epidural was excluded after randomisation and were replaced. Further, any women who reached 10 cm cervical dilation within one hour of drug administration were also excluded from the analysis; it was not clear how many women were lost and replaced for these reasons.

Selective reporting

We did not formally assess outcome reporting bias, as we had access only to published study reports and without study protocols it is difficult to assess whether all outcomes have been accounted for. We were not able to explore possible publication bias by using funnel plots as too few studies were included in different comparisons.

Other potential sources of bias

Most of the studies reported that there was no apparent baseline imbalance between groups although this was not always explicit, and where tables describing characteristics of the two groups were provided, they frequently included only a small number of obstetric or demographic variables. In the study by Tsui 2004, there was imbalance between groups in terms of the numbers of women undergoing induction of labour in the two groups (20/25 in the pethidine group and 12/25 in the placebo group), and this may have had an impact on outcomes. In the study by Rayburn 1989a women were only recruited to the study at very limited times (weekdays 8am to 3pm), and while this may not put findings at high risk of bias, it may mean that those recruited were not representative of the population served by the study hospital.

In the Characteristics of included studies and risk of bias tables we have set out more information which will assist in the interpretation of results.

Effects of interventions

In this section where several studies have contributed data to a comparison, we have reported primary and secondary outcomes separately. For some comparisons single studies provided data on a very limited number of outcomes; for these comparisons we have reported outcomes under one heading. We had planned subgroup analysis by parity, by whether or not the labour was induced or augmented, by gestational age (preterm versus term birth) and by whether or not women had continuous support during labour. In this version of the review we were unable to carry out this analysis, as data were not provided by subgroups. In addition, we did not carry out planned sensitivity analysis by study quality as for most outcomes only one or two studies contributed data, and excluding lower-quality studies from the analyses was unlikely to shed any further light on findings.

Intramuscular opioids for pain relief in labour

1. IM pethidine versus placebo

Three studies with 254 women were included in this comparison (Kamyabi 2003; Sliom 1970; Tsui 2004), although for most outcomes only a single study contributed data.

Primary outcomes

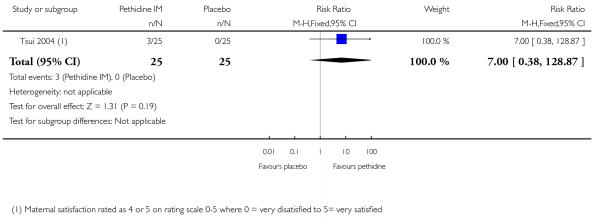

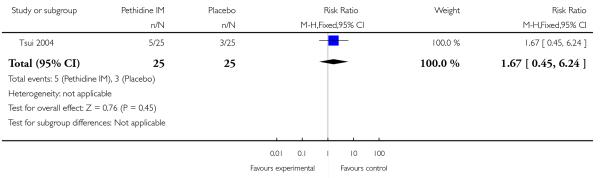

One study involving 50 women (Tsui 2004) showed no significant difference in maternal satisfaction 30 minutes after administration of study drug (risk ratio (RR) 7.00, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.38 to 128); only three of 25 women receiving pethidine and none of the women receiving placebo were ‘satisfied’ or ‘very satisfied’ with analgesia (Analysis 1.1).

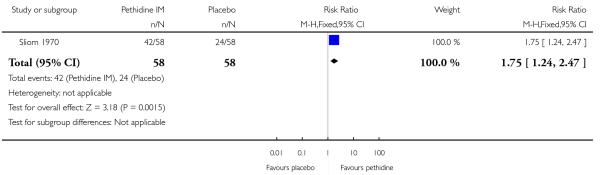

One study involving 116 women (Sliom 1970) reported significantly more women in the pethidine group with “fair” or “good” pain relief (RR 1.75, 95% CI 1.24 to 2.47) (Analysis 1.2).

Secondary outcomes

Maternal

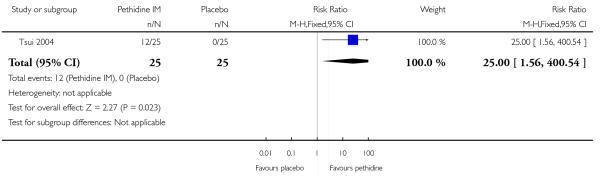

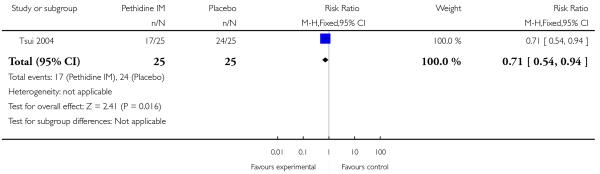

Maternal pain relief 30 minutes after study drug administration, defined as a reduction in visual analogue scale (VAS) score of at least 40 mm, was measured in one study with 50 women (Tsui 2004) and was significantly greater for pethidine 100 mg compared with placebo (RR 25, 95% CI 1.56 to 400) though the CI for this estimate is very wide (Analysis 1.3). In this study, although the majority of women in both groups required additional analgesia, this applied to fewer women with pethidine 100 mg compared with placebo (RR 0.71, 95% CI 0.54 to 0.94) (Analysis 1.4).

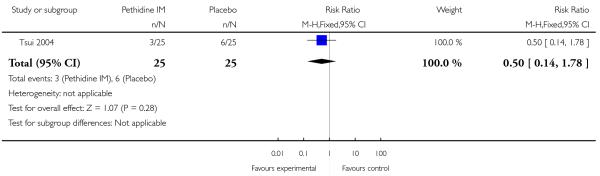

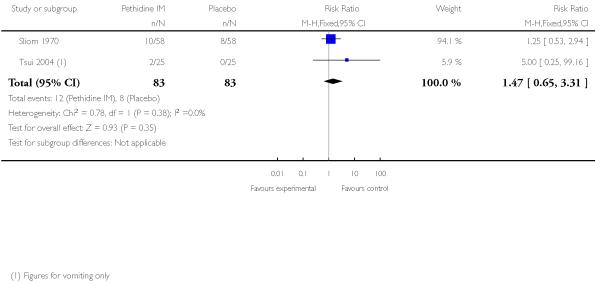

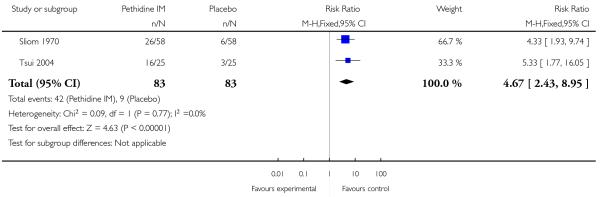

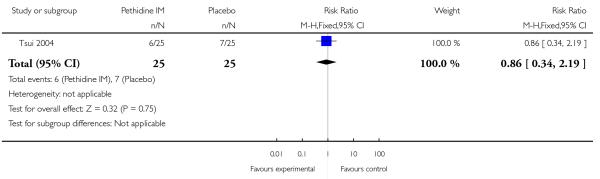

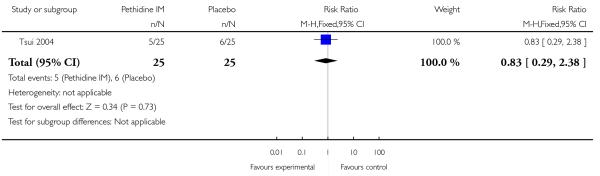

There was no evidence of differences between groups in the number of women requiring an epidural (RR 0.50, 95% CI 0.14 to 1.78) (Analysis 1.5), in the incidence of nausea and vomiting (RR 1.47, 95% CI 0.65 to 3.31) (Analysis 1.6), assisted vaginal birth (RR 0.86, 95% CI 0.34 to 2.19) (Analysis 1.8), or caesarean section (RR 0.83, 95% CI 0.29 to 2.38) (Analysis 1.9). Significantly more women reported sleepiness with pethidine 100 mg, with half of those receiving pethidine feeling sedated compared with 11% of controls (RR 4.67, 95% CI 2.43 to 8.95) (Analysis 1.7).

In one study, 12/25 women in the placebo group had pethidine at 30 minutes as rescue analgesia confounding interpretation of reported outcomes after 30 minutes (Tsui 2004).

Neonatal

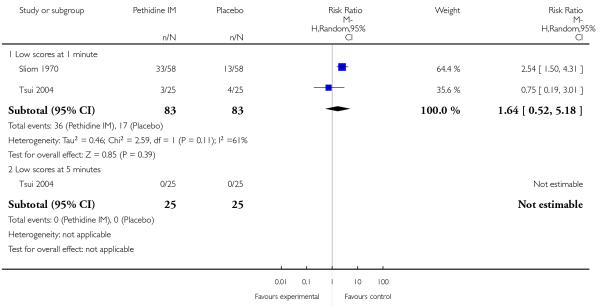

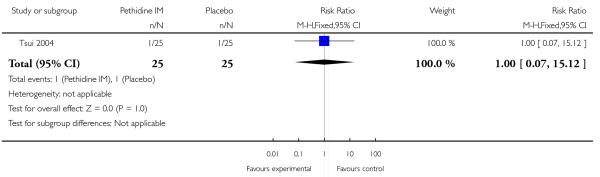

The number of babies with Apgar scores of seven or less at one minute did not differ between the placebo and pethidine groups; for this outcome we used a random-effects model because of high heterogeneity (average RR 1.64, 95% CI 0.52 to 5.18), (heterogeneity: I2 = 61%, Tau2 = 0.46, Chi2 test for heterogeneity P = 0.11) (Analysis 1.10). No babies had Apgar scores less than or equal to seven at five minutes in the one study that reported this outcome (Analysis 1.10). The incidence of newborn resuscitation and admission to neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) was low; no significant differences between groups was detected (Analysis 1.11; Analysis 1.12).

One study reported incidence of fetal respiratory depression, but the study drugs were given late in labour to assess maximum fetal effect. Participants were not included in the analysis if birth was less than 30 minutes or more than four hours after administration of study drugs (Sliom 1970).

We were unable to include any results from one study that met the inclusion criteria, as it was unclear when outcomes were measured how they were defined and how many participants were included in the analysis (Kamyabi 2003). In this study, mean Apgar scores at one minute were reported to be higher (P = 0.008) in the pethidine 75 mg group compared with placebo group (data not shown).

2. IM meptazinol versus IM pethidine

IM meptazinol versus IM pethidine was evaluated in six studies with 1898 women (Morrison 1987; Nel 1981; Nicholas 1982; Osler 1987; Sheikh 1986; Wheble 1988), and in two additional studies where women in both study groups also received add-on drugs (De Boer 1987; Jackson 1983).

Primary outcomes

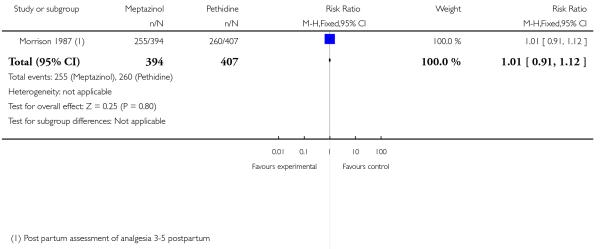

One study (Morrison 1987) involving 801 women showed no evidence of a difference between meptazinol 100 mg to 150 mg compared with pethidine 100 mg to 150 mg for assessment of analgesic effect measured at three to five days postpartum (RR 1.01, 95% CI 0.91 to 1.12) (Analysis 2.1). In this study, more than half of the women receiving either of these opioids reported that they received no or poor relief despite the fact that women in both groups could also receive an additional dose of study drug, epidural or nitrous oxide as required.

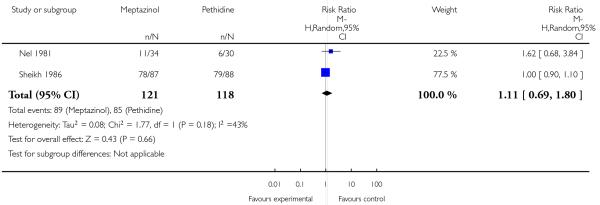

In two studies (Nel 1981; Sheikh 1986) involving 239 women, there was no evidence of a difference between groups in pain intensity one hour after administration of meptazinol 100 mg or pethidine 100 mg; more than two-thirds of women in both groups were rating their pain as severe (four or five on a five-point scale) at one hour (average RR 1.11, 95% CI 0.69 to 1.80 (random-effects; heterogeneity: I2 = 43%, Tau2 = 0.08, Chi2 test for heterogeneity P = 0.18) (Analysis 2.2).

Secondary outcomes

Maternal

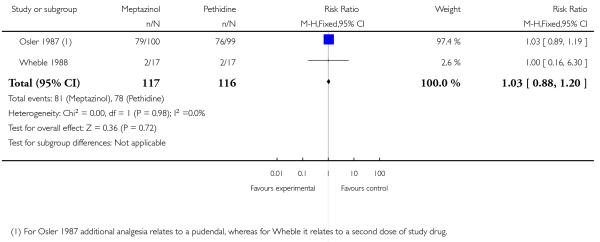

Two studies (Osler 1987; Wheble 1988) involving 233 women found no evidence of a difference in requirement for additional analgesia between those who received meptazinol compared with pethidine (RR 1.03, 95% CI 0.88 to 1.20) (Analysis 2.3). This outcome is difficult to interpret as women in the study by Osler 1987 were allowed up to three doses of study drug (meptazinol 100 mg or pethidine 75 mg). Overall, 56 women required a second dose and 15 a third dose, but the number per group was not reported. Whereas in the study by Wheble 1988, women were allowed a second dose of study drug (meptazinol 100 mg or 150 mg or pethidine 100 mg or 150 mg) or epidural or nitrous oxide at the discretion of the caregiver. Additional analgesia relates to a pudendal in the one study (Osler 1987), and a second dose of study drug in the other (Wheble 1988).

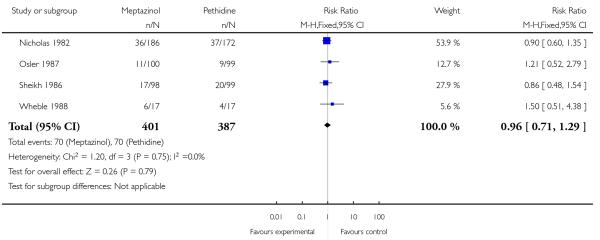

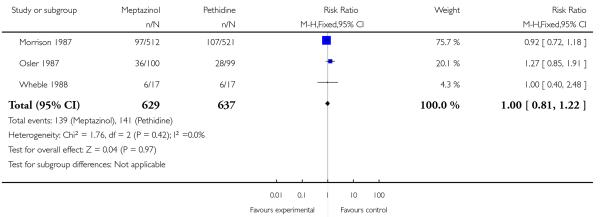

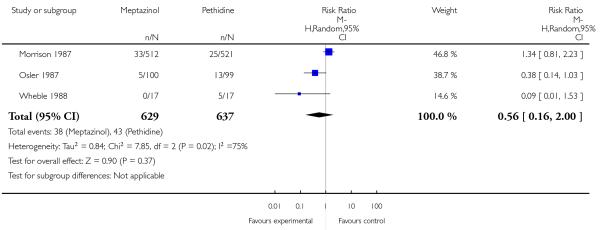

The use of epidural analgesia was similar between meptazinol and pethidine (RR 0.96, 95% CI 0.71 to 1.29) in four studies (Nicholas 1982; Osler 1987; Sheikh 1986; Wheble 1988) involving 788 women (Analysis 2.4). Instrumental birth was reported in three studies (Morrison 1987; Osler 1987; Wheble 1988) involving 1266 women, and rates were similar between groups (RR 1.00, 95% CI 0.81 to 1.22) (Analysis 2.7). Overall, there was no evidence of a difference in rates of caesarean section between meptazinol and placebo. However, substantial heterogeneity was detected; therefore, we used a random-effects model (average RR 0.56, 95% CI 0.16, 2.00) (heterogeneity: I2 = 75%, T2 = 0.84, Chi2 test for heterogeneity P = 0.02), (Analysis 2.8).

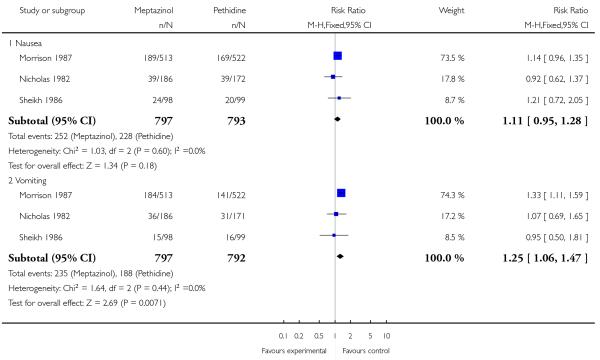

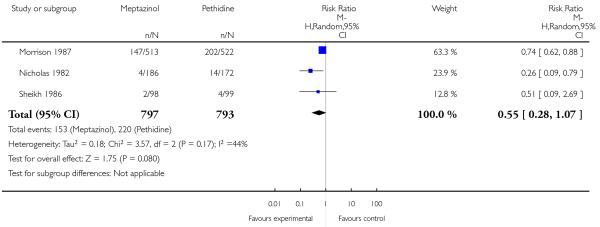

Three studies each reported nausea, vomiting and sleepiness (Morrison 1987; Nicholas 1982; Sheikh 1986). There was no evidence for a difference in nausea (RR 1.11, 95% CI 0.95 to 1.28); however, significantly more women reported vomiting (RR 1.25, 95% CI 1.06 to 1.47) with meptazinol compared with pethidine. Fewer women in the meptazinol group reported sleepiness (average RR 0.55, 95% CI 0.28 to 1.07), although there was moderate heterogeneity for this outcome (heterogeneity: I2 = 44%, T2 = 0.18, Chi2 test for heterogeneity P = 0.17) and the difference between groups did not reach statistical significance (Analysis 2.6).

Neonatal

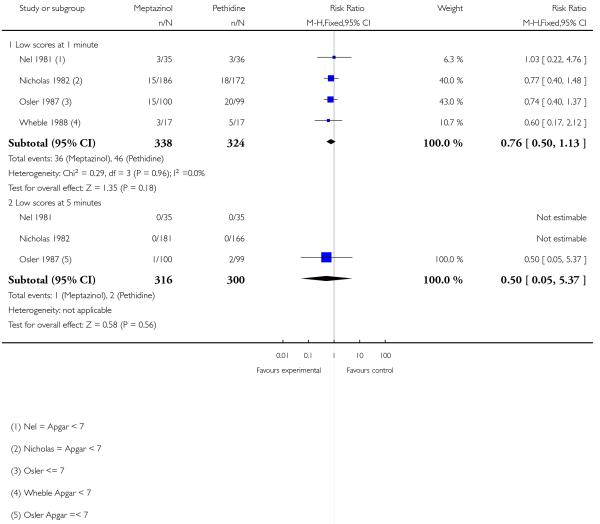

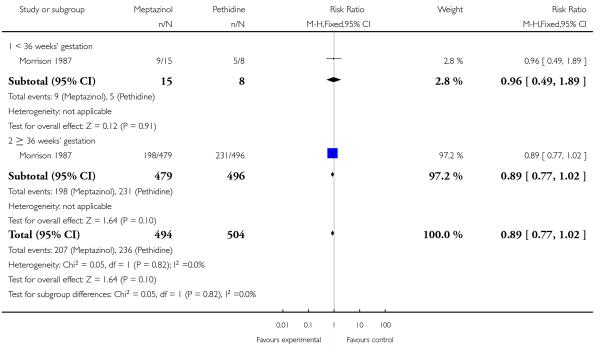

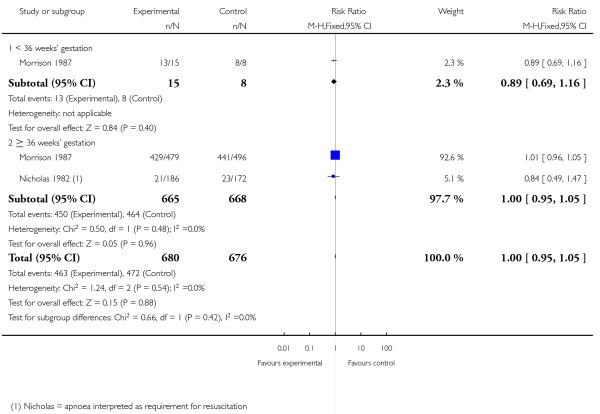

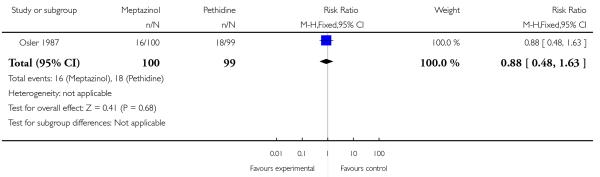

Four studies involving 662 women reported number of babies with Apgar scores less than or equal to seven at one minute (Nel 1981; Nicholas 1982; Osler 1987; Wheble 1988), and three studies reported this outcome at five minutes (Nel 1981; Nicholas 1982; Osler 1987). There was no evidence of a difference between groups at one minute (RR 0.76, 95% CI 0.50 to 1.13) or five minutes (RR 0.49, 95% CI 0.05 to 5.37) with three babies with low scores at five minutes reported in one study (Osler 1987) and none in the other two (Nel 1981; Nicholas 1982) (Analysis 2.10). We found no evidence of a difference between meptazinol compared with pethidine for naloxone administration (RR 0.89, 95% CI 0.77 to 1.02), admission to NICU (RR 0.88, 95% CI 0.48 to 1.63) or newborn resuscitation (Analysis 2.11; Analysis 2.12; Analysis 2.13). In one study (Morrison 1987), 40% of the babies were given naloxone, reflecting local practice at the time rather than low Apgar scores; with 41% of the babies having Apgar scores greater than or equal to eight at the time of administration.

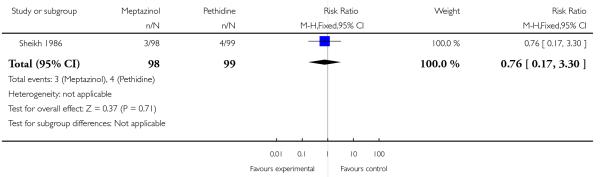

Breastfeeding problems were reported by a small number of women in one study (Sheikh 1986); there was no evidence of a difference between groups (RR 0.76, 95% CI 0.17 to 3.30).

Meptazinol versus pethidine with add-on drugs

One study compared IM meptazinol 1.8 mg/kg with IM pethidine 1.8 mg/kg; all women also received promazine 25 mg IM (Jackson 1983). A second study compared IM meptazinol 1.5 mg/kg with IM pethidine 1.5 mg/kg; all women also received metoclopramide 10 mg IM (De Boer 1987). Women could receive a second dose of study drug after three hours in both studies. Both studies were conducted to assess effects of the study drugs on the newborn only.

Primary and secondary outcomes

Maternal outcomes were not measured.

Neonatal

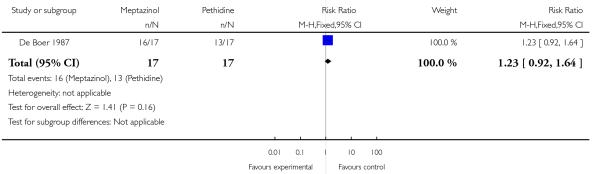

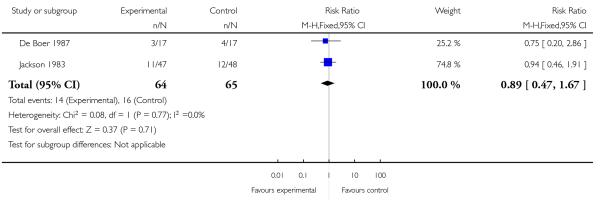

Both studies reported the number of babies with Apgar scores less than or equal to seven at one minute. There was no evidence of a difference between meptazinol compared with pethidine (RR 0.89, 95% CI, 0.47 to 1.67). In the study by De Boer 1987, Apgar at five and 10 minutes were reported as ‘similar’ in both groups and there was no evidence of difference in the number of babies with fetal heart rate changes (decelerations). In the study by Jackson 1983, no babies in either group had Apgar scores less than or equal to seven at 10 minutes. In one study (Jackson 1983), three babies in the meptazinol group and two in the pethidine group required resuscitation.

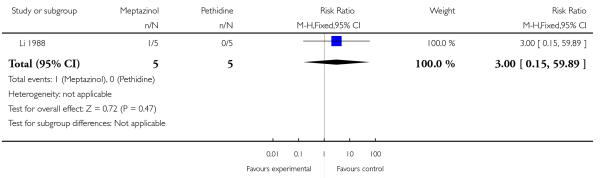

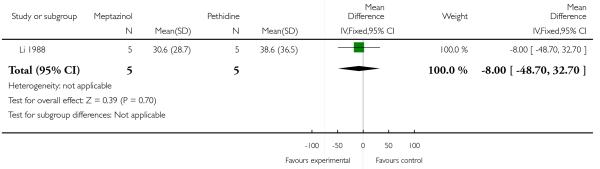

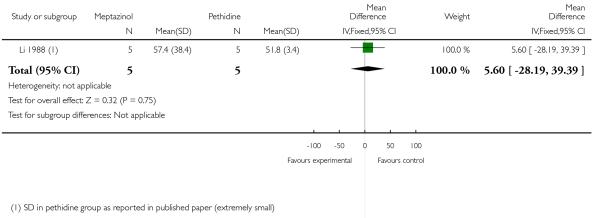

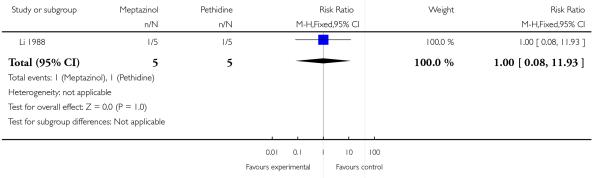

3. PCA (IM) meptazinol versus PCA (IM) pethidine

One study involving 10 women examined the feasibility of IM meptazinol versus IM pethidine with PCA administration (Li 1988).

Primary and secondary outcomes

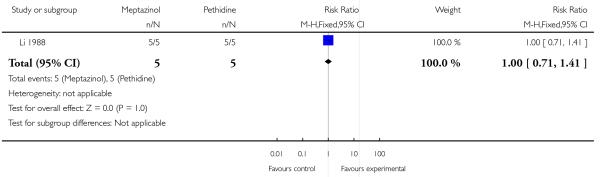

All women in both groups were satisfied with the mode of administration (Analysis 3.2).

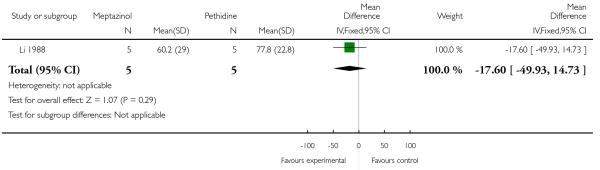

Pain scores measured one day postpartum were lower with meptazinol compared with pethidine; however, there was no evidence of a significant difference (mean difference (MD) −17.60, 95% CI −49.93 to 14.73) (Analysis 3.1). Epidural rates and nausea and drowsiness scores evaluated one day postpartum were similar between groups (Analysis 3.3; Analysis 3.4; Analysis 3.5).

Neonatal

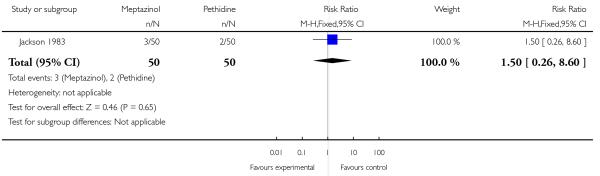

Naloxone was administered to one baby in each group (Analysis 3.6).

4. IM diamorphine + prochlorperazine versus IM pethidine + prochlorperazine

One study involving 133 women compared IM diamorphine 5 mg to 7.5 mg versus IM pethidine 100 mg to 150 mg. All women also received IM prochlorperazine 12.5 mg at the same time as the study drug (Fairlie 1999).

Primary outcomes

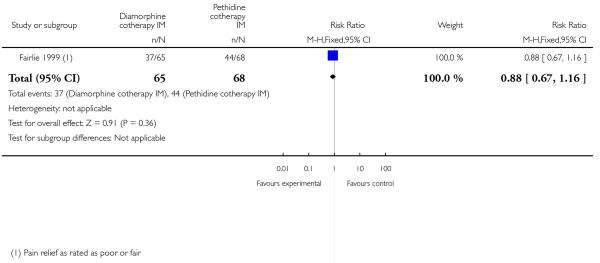

Global assessment of pain relief was evaluated at 24 hours; there was no evidence of a difference between groups in the number of women reporting ‘fair’ or ‘poor’ as opposed to ‘good’ pain relief, with more than half of the women in both groups having inadequate relief (RR 0.88, 95% CI 0.67 to 1.16) (Analysis 4.1).

Secondary outcomes

Maternal

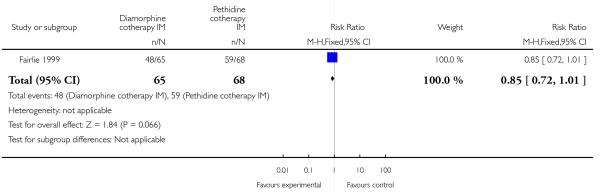

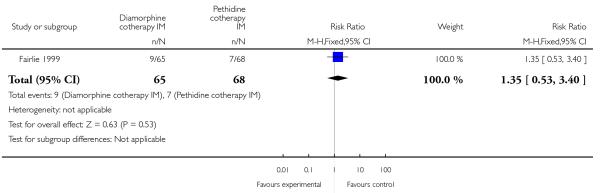

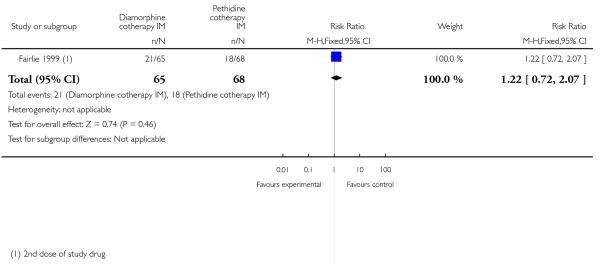

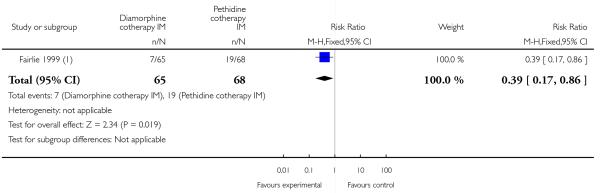

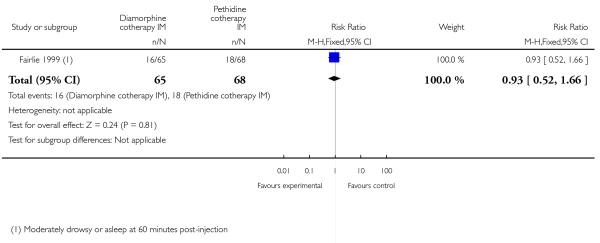

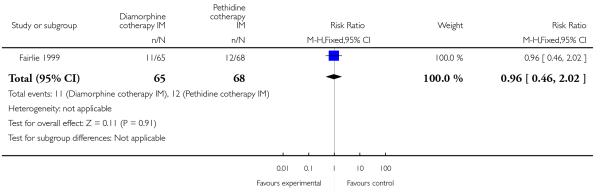

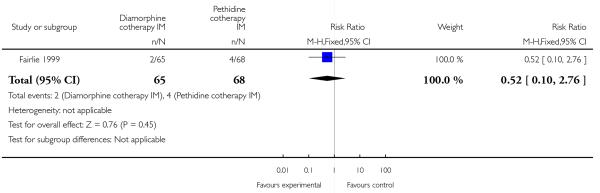

More women reported pain intensity as moderate or severe one hour post administration of study drug with pethidine compared with diamorphine, though there was no evidence of a significant difference between groups, with the majority of women in both groups reporting moderate or severe pain (RR 0.85, 95% CI 0.72 to 1.01) (Analysis 4.2). There was no evidence for a difference between groups in the number of women requiring additional analgesia (RR 1.35, 95% CI 0.53 to 3.4) (Analysis 4.3), an epidural (RR 1.22, 95% CI 0.72 to 2.07) (Analysis 4.4), assisted vaginal birth (RR 0.96, 95% CI 0.46 to 2.02) (Analysis 4.7), or caesarean section (RR 0.52, 95% CI 0.10 to 2.76) (Analysis 4.8).

The number of women vomiting was significantly lower with diamorphine compared with pethidine (RR 0.39, 95% CI 0.17 to 0.86) (Analysis 4.5), but the number of women moderately drowsy or asleep one hour after study drug administration was similar between groups (RR 0.93, 95% CI 0.52 to1.66) (Analysis 4.6).

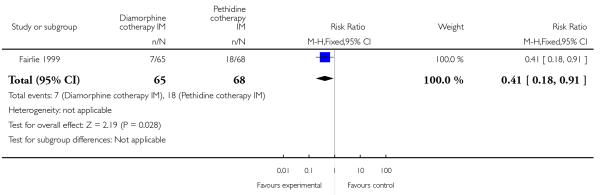

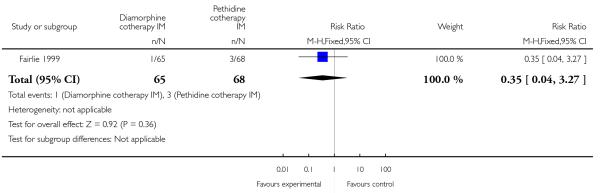

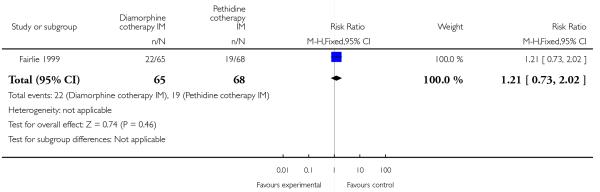

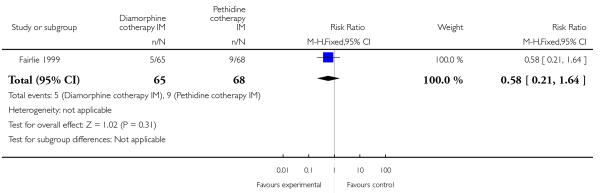

Neonatal

Significantly fewer babies had Apgar scores less than seven at one minute with diamorphine compared with pethidine (RR 0.41, 95% CI 0.18 to 0.91) (Analysis 4.9). However, there was no evidence of a difference between groups at five minutes, with few babies with an Apgar score less than seven in either group (RR 0.35, 95% CI 0.04 to 3.27) (Analysis 4.10). There were no significant differences between groups for the number of babies needing resuscitation (RR 1.21, 95% CI 0.73 to 2.02) (Analysis 4.11), or admission to NICU (RR 0.58, 95% CI 0.21 to 1.64) (Analysis 4.12).

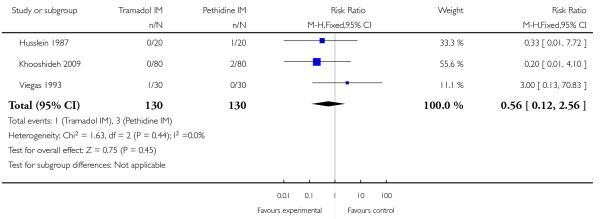

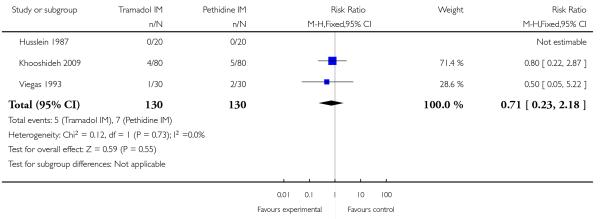

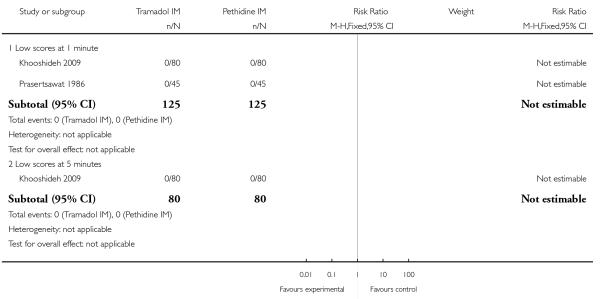

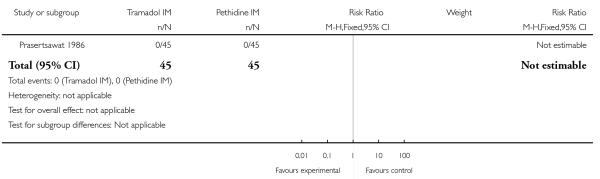

5. IM tramadol versus IM pethidine

Seven studies involving 569 women compared IM tramadol versus IM pethidine (Bitsch 1980; Fieni 2000; Husslein 1987; Keskin 2003; Khooshideh 2009; Prasertsawat 1986; Viegas 1993). Tramadol and pethidine doses varied between studies and were 50, 75 or 100 mg.

Primary and secondary outcomes

Maternal

Women’s satisfaction with pain relief was not measured in any of the studies.

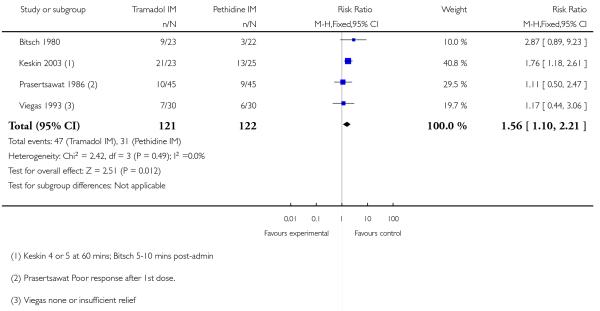

Pain intensity was defined in disparate ways in the studies; however, significantly more women had poor pain relief with tramadol compared with pethidine (RR 1.56, 95% CI 1.10 to 2.21) (Analysis 5.1).

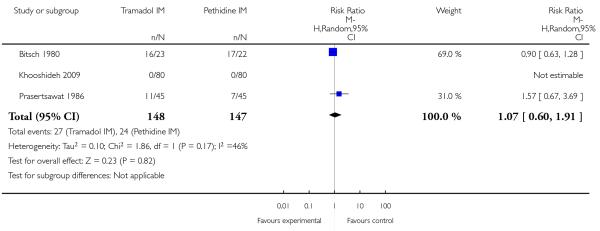

In three studies which reported requirement for additional analgesia, no evidence of a difference was detected (average RR 1.07, 95% CI 0.60 to 1.91) (Analysis 5.2).

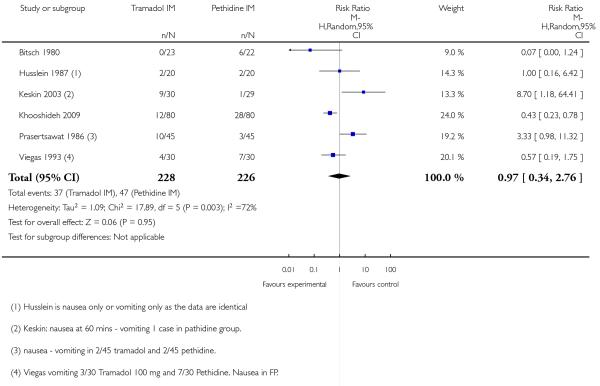

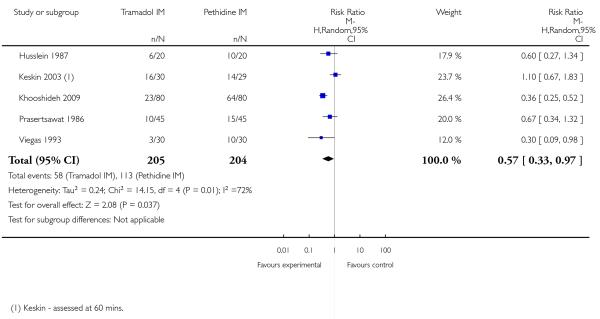

There was no evidence for a difference in incidence of nausea and/or vomiting with tramadol compared with placebo (average RR 0.97, 95% CI 0.34 to 2.76) (Analysis 5.3). There was a substantial level of heterogeneity detected for this outcome (I2 = 72%, T2 = 1.09, Chi2 test for heterogeneity P = 0.003) therefore we used a random-effects model for the analysis. More women in the pethidine group reported sleepiness and the difference between groups reached statistical significance although, again, heterogeneity was high and we used a random-effects model (average RR 0.57, 95% CI 0.33 to 0.97), (heterogeneity I2 = 72%, T2 = 0.24, Chi2 test for heterogeneity P = 0.007) (Analysis 5.4).

Neonatal

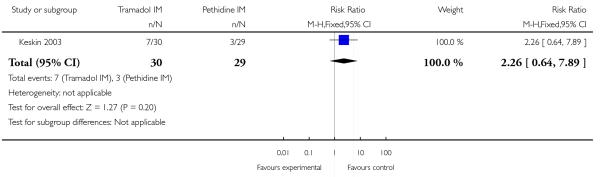

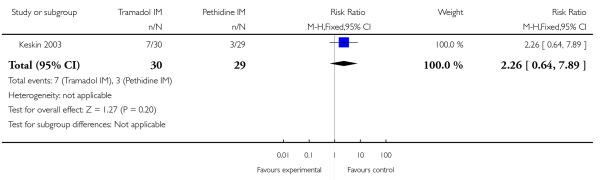

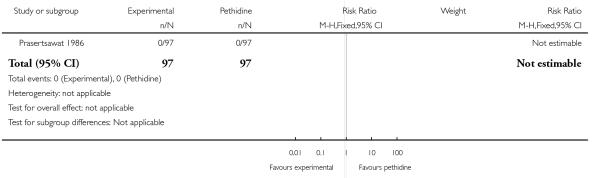

Only two studies reported Apgar scores (Khooshideh 2009; Prasertsawat 1986), and reported no babies in either group with Apgar scores less than or equal to seven at one or five minutes, and no babies requiring resuscitation (Analysis 5.7; Analysis 5.8). One study (Keskin 2003) reported the incidence of respiratory distress and admission to NICU which occurred more frequently with tramadol 100 mg compared with pethidine 100 mg, though results were not statistically significant for either outcome (RR 2.26, 95% CI 0.64 to 7.89) (Analysis 5.9; Analysis 5.10).

6. IM tramadol + triflupromazine versus IM pethidine + triflupromazine

One study involving 66 women compared tramadol 500 mg with pethidine 50 mg, and both groups also received triflupromazine 10 mg (Kainz 1992). A third study arm received tramadol 100 mg.

Primary and secondary outcomes

Maternal satisfaction with analgesic effect was not measured. The authors reported that the analgesic effect was equally good in each study arm. Data for effects on pain were not reported (P values for the change within groups were reported; not the between group differences; data not shown).

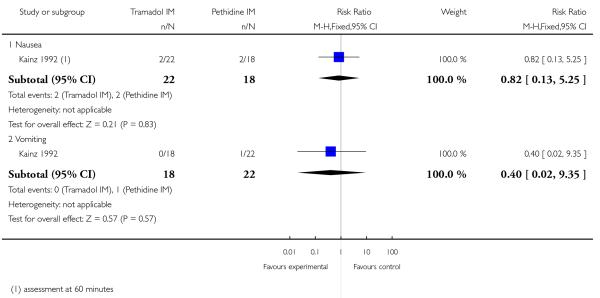

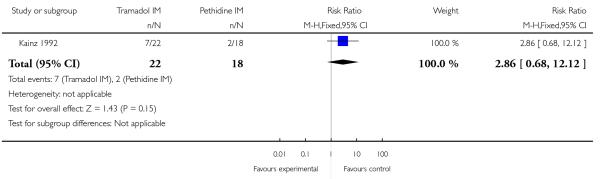

The incidence of nausea or vomiting was reported and was infrequent, with no evidence of differences between groups (RR 0.82, 95% CI 0.13 to 5.25 and RR 0.40, 95% CI 0.02 to 9.35, respectively) (Analysis 6.1). Sleepiness was more frequently reported by women who received tramadol, though no statistically significant difference between groups was detected (RR 2.86, 95% CI 0.68 to 12.12) (Analysis 6.2).

The authors report that there were no negative effects on the newborn; though no data were presented.

7. IM dihydrocodeine versus IM pethidine

One study involving 106 women compared a single dose of IM dihydrocodeine 50 mg with IM pethidine 100 mg (Sliom 1970). An additional study arm received placebo.

Primary and secondary outcomes

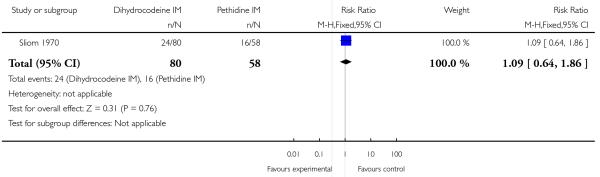

There was no evidence of a difference in pain relief between groups with a substantial proportion of women in each group reporting poor pain relief one hour after administration of study drug (RR 1.09, 95% CI 0.64 to 1.86) (Analysis 7.1).

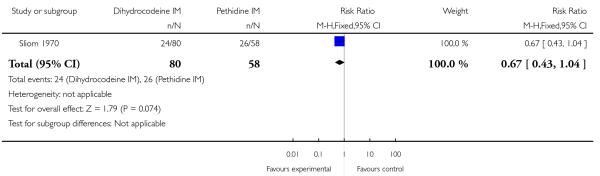

There was no evidence of a difference between dihydrocodeine and pethidine for nausea and vomiting (RR 0.87, 95% CI 0.40 to 1.88) (Analysis 7.2), or sleepiness (RR 0.67, 95% CI 0.43 to 1.04) (Analysis 7.3).

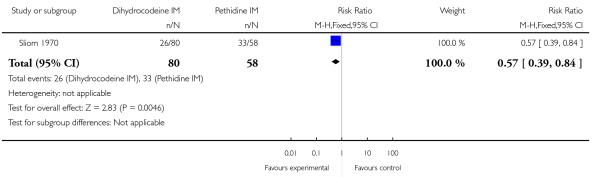

Significantly fewer babies had Apgar scores less than or equal to seven at one minute with dihydrocodeine compared with pethidine (RR 0.57, 95% CI 0.39 to 0.84) (Analysis 7.4). Apgar score at five minutes was reported as mean scores rather than number of babies in each group: there was no significant difference between groups reported (data not shown).

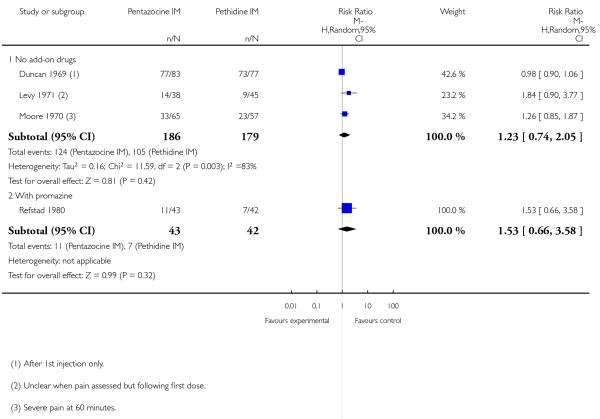

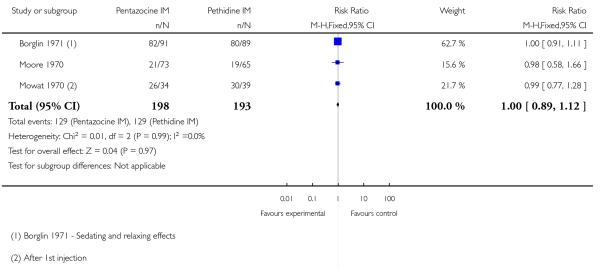

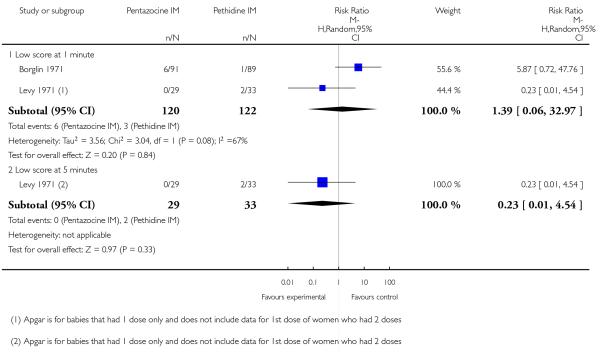

8. IM pentazocine versus pethidine

Six studies with 877 women are included in this comparison (Borglin 1971; Duncan 1969; Levy 1971; Moore 1970; Mowat 1970; Refstad 1980).

Primary outcomes

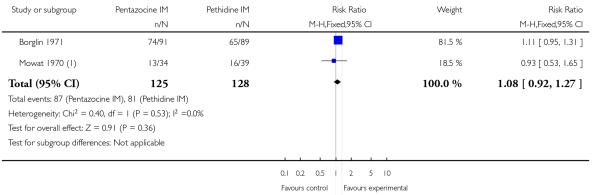

Two studies reported on the numbers of women rating pain relief as good or very good at birth (Borglin 1971; Mowat 1970), and there was no statistically significant difference between groups in either study, or when results were pooled (Analysis 8.1).

Four studies reported poor pain relief (Duncan 1969; Levy 1971; Moore 1970; Refstad 1980); more than half of the women in both groups had only partial or poor relief and there was no statistically significant difference between groups (Analysis 8.2).

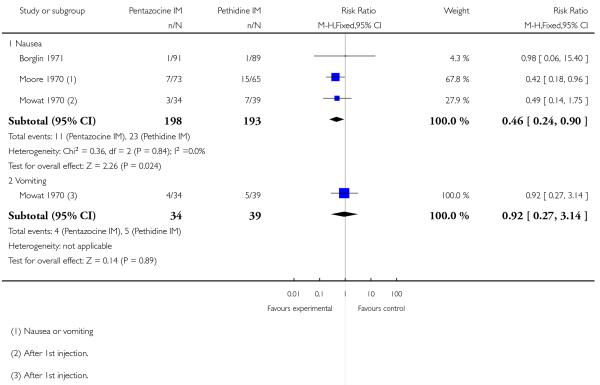

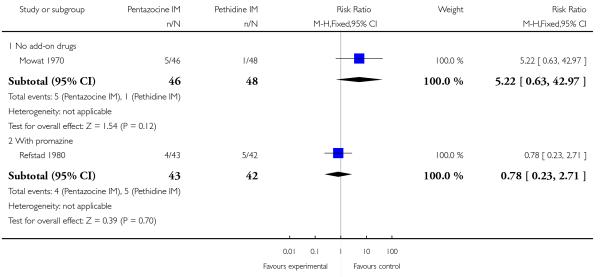

Secondary outcomes

The use of additional analgesic drugs was reported by two studies (Mowat 1970; Refstad 1980). There was no statistically significant difference between groups in either study (Analysis 8.3).

One or more studies reported nausea, vomiting, sleepiness or assisted vaginal birth; there was no significant evidence of a difference between groups for any of these outcomes (Analysis 8.4; Analysis 8.5; Analysis 8.6).

Two studies reported the incidence of low Apgar scores at one and five minutes (Borglin 1971; Levy 1971) with no statistically significant difference between groups (Analysis 8.7).

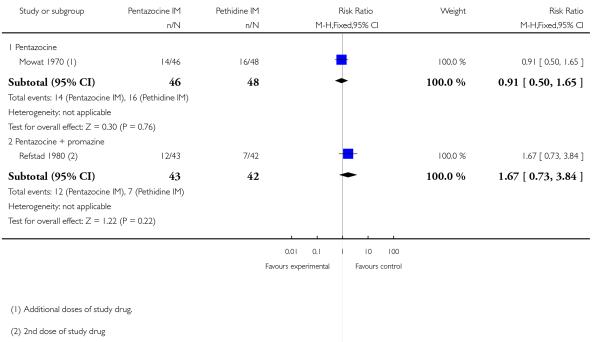

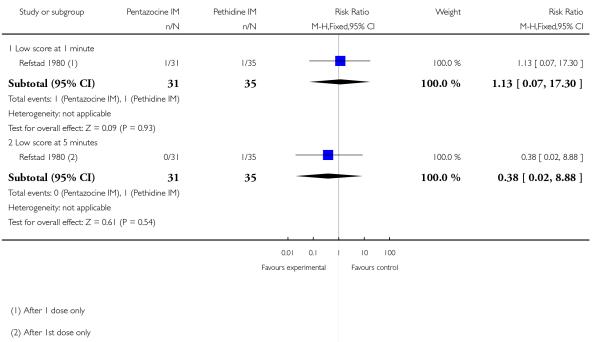

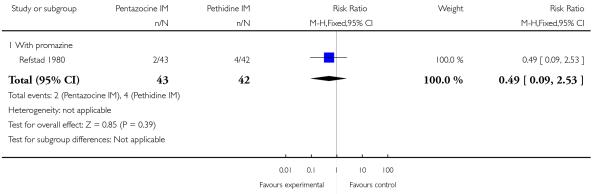

9. IM pentazocine + promazine versus pethidine + promazine

One study with 85 women contributed data to this comparison (Refstad 1980).

Primary and secondary outcomes

This study reported on only two of the review’s outcomes: low Apgar score at one and five minutes and naloxone administration. There was no statistically significant difference between groups for either outcome (Analysis 9.1; Analysis 9.2).

10. IM nalbuphine versus pethidine

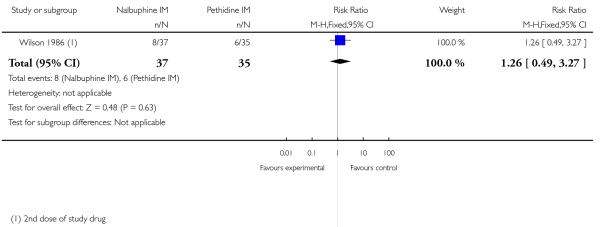

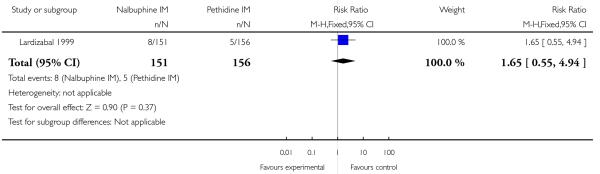

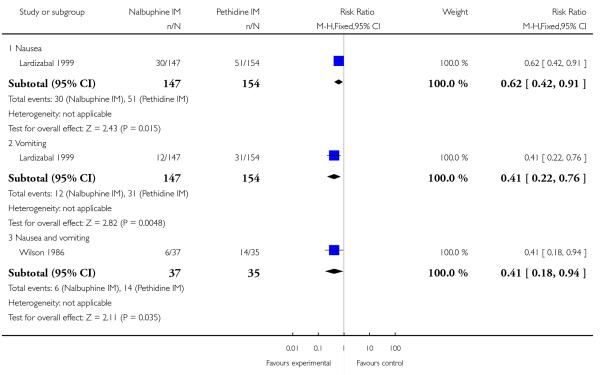

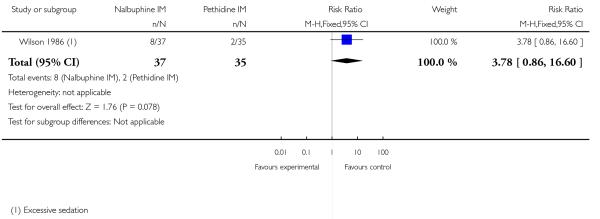

Four studies with 486 women are included in this comparison (Lardizabal 1999; Lisboa 1997; Mitterschiffthaler 1991; Wilson 1986).

Primary outcomes

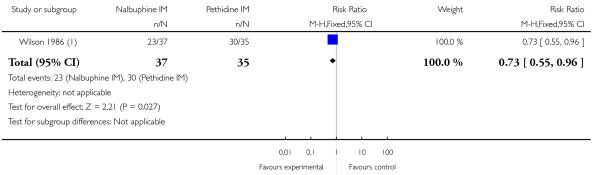

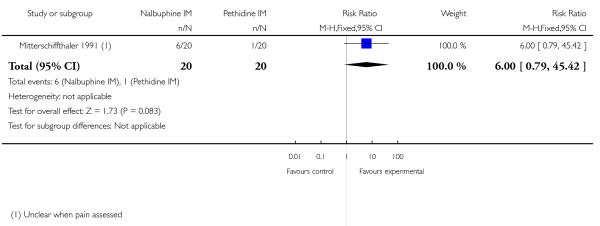

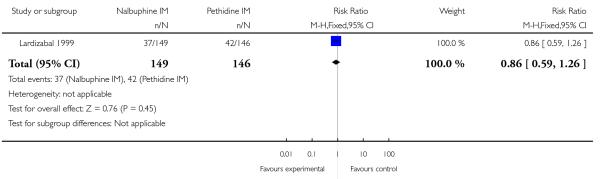

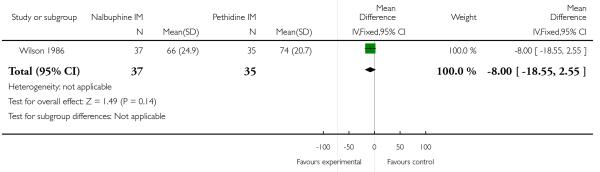

One study reported maternal satisfaction with analgesia at 24 hours (Wilson 1986). The majority of women receiving both nalbuphine and pethidine thought that analgesia had been “minimally effective” (63% and 85% respectively), although the difference between groups was statistically significant (RR 0.73, 95% CI 0.55 to 0.96) (Analysis 10.1). One study reported the number of women that were free of pain (Mitterschiffthaler 1991); the difference between groups was not statistically significant, with few women in either group having no pain (Analysis 10.2). Two studies reported pain intensity: one at 30 minutes (Lardizabal 1999) and the other at 60 minutes (Wilson 1986). There was no statistically significant difference between groups in either study (Analysis 10.3; Analysis 10.4).

Secondary outcomes

Maternal

Two studies reported the use of additional analgesia (Lardizabal 1999; Wilson 1986) and there was no statistically significant difference between groups in either study (Analysis 10.5; Analysis 10.6). One study reported nausea and vomiting as separate outcomes (Lardizabal 1999), and another reported nausea and vomiting as a single outcome (Wilson 1986). Statistically significantly fewer women who received nalbuphine reported nausea alone (RR 0.62, 95% CI 0.42 to 0.91, P = 0.02), or vomiting (RR 0.41, 95% CI 0.22 to 0.76) compared with women who received pethidine.

Likewise, fewer women who received nalbuphine reported nausea and vomiting combined (RR 0.41, 95% CI 0.18 to 0.94). There was no evidence of significant differences between groups for maternal sleepiness, assisted or caesarean births in studies reporting these outcomes (Analysis 10.8; Analysis 10.9; Analysis 10.10).

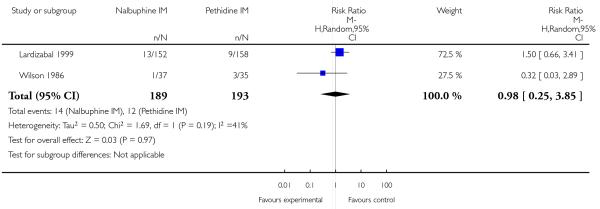

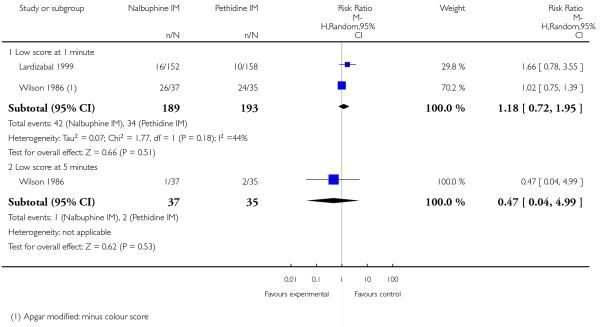

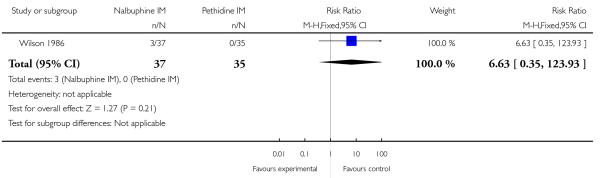

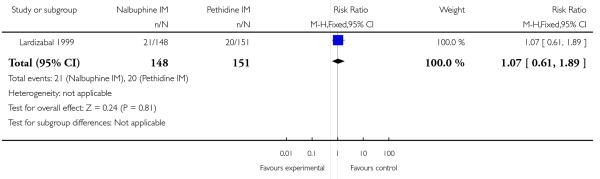

Neonatal

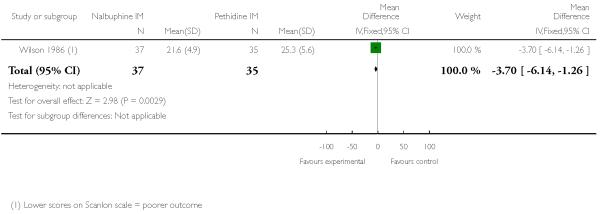

Two studies reported neonatal outcomes (Lardizabal 1999; Wilson 1986). There was no statistically significant difference between groups for low Apgar scores at one, five and 10 minutes, naloxone administration or admission to NICU (Analysis 10.11; Analysis 10.12; Analysis 10.13). One study reported a neonatal neurobehavioural score two to four hours following birth (Wilson 1986); babies of women who received nalbuphine had lower scores than babies born to women in the control group (MD −3.70, 95% CI −6.14 to −1.26).

11. IM phenazocine versus pethidine

One study with 212 women (Grant 1970) compared IM phenazocine versus IM pethidine.

Primary and secondary outcomes

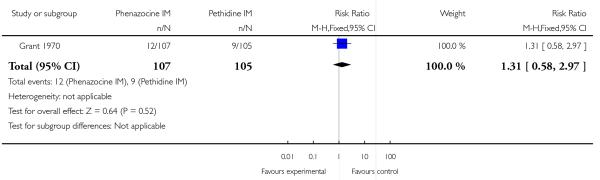

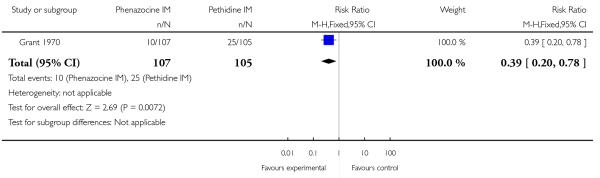

This study reported only two outcomes: epidural uptake and vomiting. There was no statistically significant difference between groups for epidural (Analysis 11.1), but fewer women who received phenazocine vomited (RR 0.39, 95% CI 0.20 to 0.78) compared with those who received pethidine.

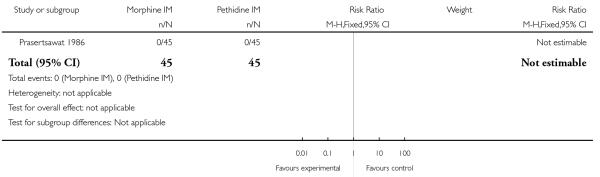

12. IM morphine versus pethidine

We included one study with 135 women in this comparison (Prasertsawat 1986).

Primary and secondary outcomes

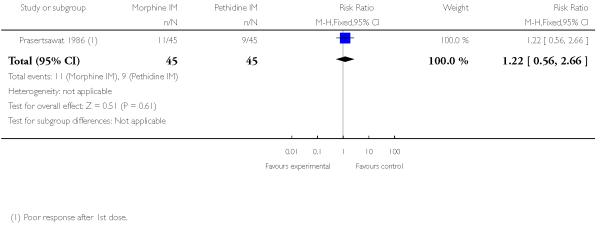

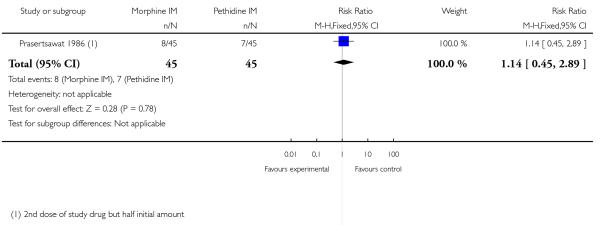

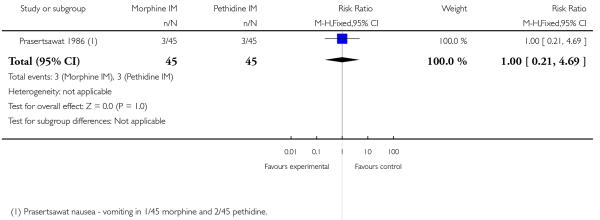

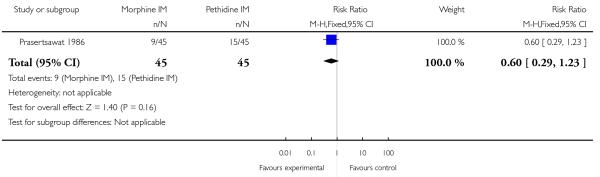

There was no statistically significant difference between groups in the number of women describing their pain relief as poor (RR 1.22, 95% CI 0.56 to 2.66), additional analgesia (Analysis 12.2), nausea and vomiting (Analysis 12.3), or maternal sleepiness (Analysis 12.4). There was also no statistically significant difference between groups for number of babies born with an Apgar score less than or equal to seven at birth (Analysis 13.1), or requiring resuscitation (Analysis 12.6).

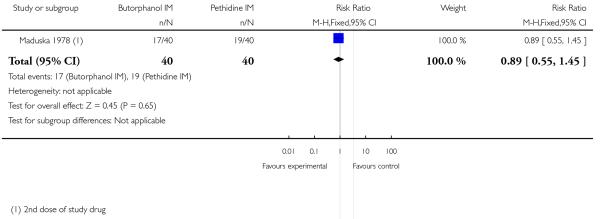

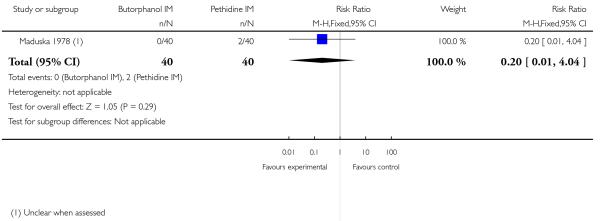

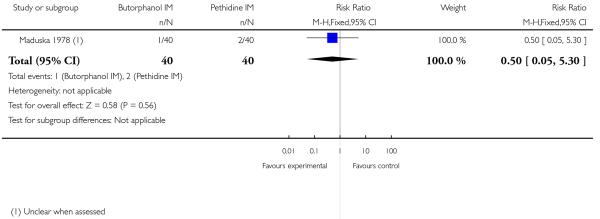

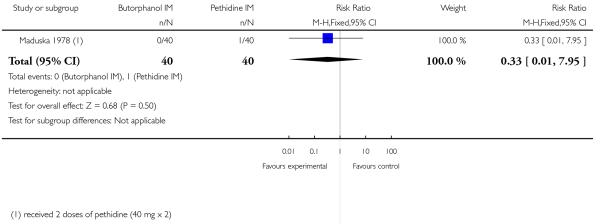

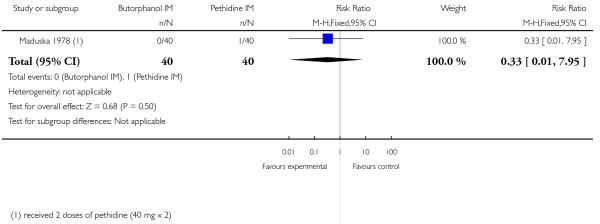

13. IM butorphanol versus pethidine

One study with 80 women compared IM butorphanol with IM pethidine (Maduska 1978).

Primary and secondary outcomes

This study did not report on the review’s primary outcomes. There was no significant evidence of differences between groups for additional analgesia (Analysis 13.1), nausea (Analysis 13.2), or vomiting (Analysis 13.3). Likewise, there was no significant difference between groups for neonatal resuscitation (Analysis 13.4) or naloxone administration (Analysis 13.5).

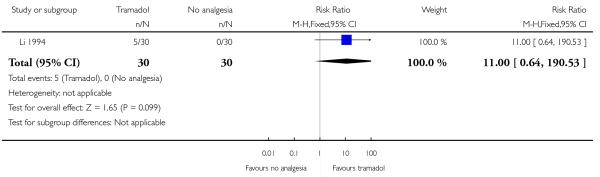

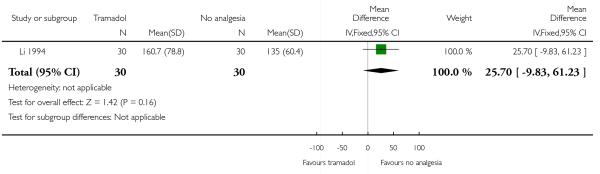

14. IM tramadol versus no treatment

One study with 60 women compared IM tramadol with no treatment (Li 1994).

Primary and secondary outcomes

This study reported only two outcomes: satisfaction with analgesia and mean blood loss at birth. Only five out of 30 of the women receiving tramadol described it as satisfactory, but the difference between groups was not significant (Analysis 14.1). There was no difference between groups for mean blood loss at birth (Analysis 14.2).

15. IM Avacan® versus IM pentazocine

We included one study with 185 women in this comparison (Hamann 1972).

Primary and secondary outcomes

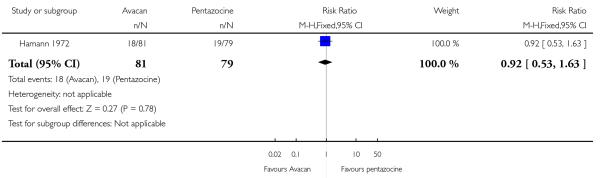

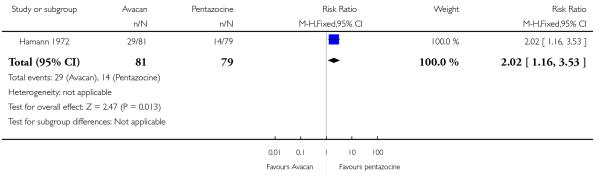

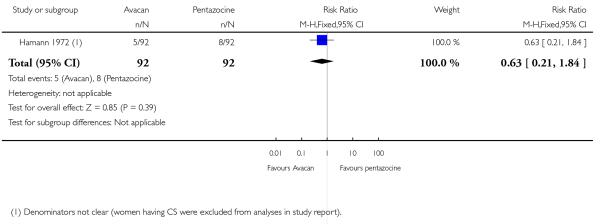

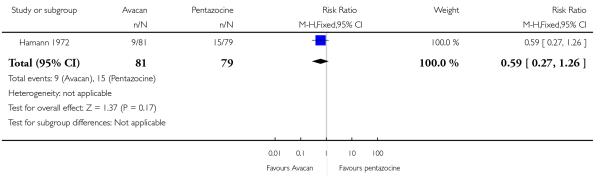

This study did not report on either of our primary outcomes. There were no statistically significant differences between groups for the uptake of nitrous oxide (Analysis 15.1). More women in the Avacan® group received a pudendal-paracervical block (RR 2.02, 95% CI 1.16 to 3.53). There was no evidence of a difference between groups for the number of women having a caesarean section, or babies born with an Apgar score less than or equal to seven at birth (Analysis 15.3; Analysis 15.4). This study did not report on any other secondary outcomes.

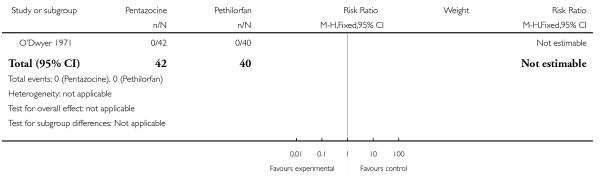

16. IM pentazocine versus IM Pethilorfan®

One trial involving 98 women compared pentazocine with Pethilorfan® (O’Dwyer 1971).

Primary and secondary outcomes

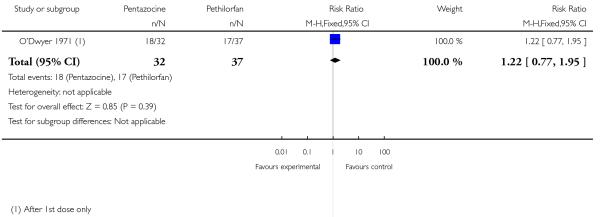

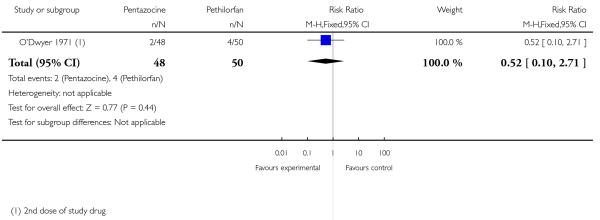

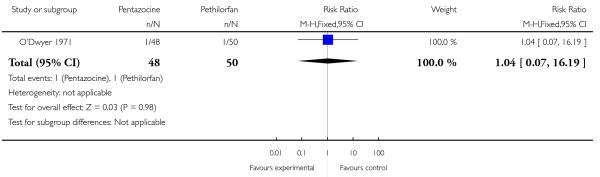

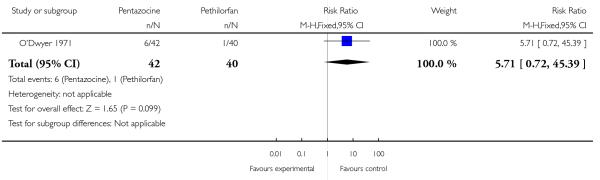

There was no statistically significant difference between study groups in the number of women saying that they did not obtain any relief from medication at one hour (RR 1.22, 95% CI 0.77 to 1.95) (Analysis 16.1).

No statistically or clinically significant differences were reported for any of the secondary outcomes recorded (additional analgesia required, assisted vaginal birth, Apgar score less than eight at one minute, Apgar score less than eight at five minutes) (Analysis 16.2; Analysis 16.3; Analysis 16.4; Analysis 16.5).

Intravenous opioids for pain relief in labour

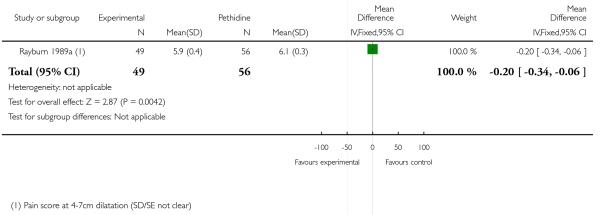

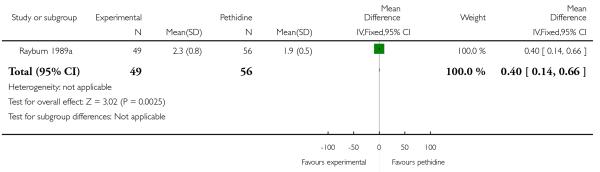

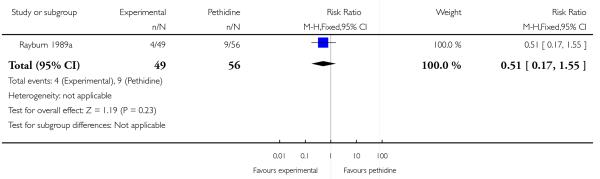

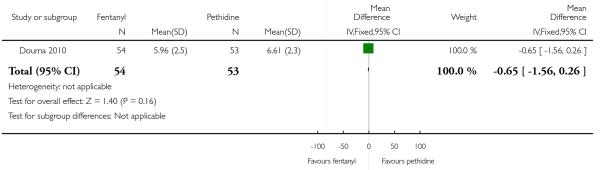

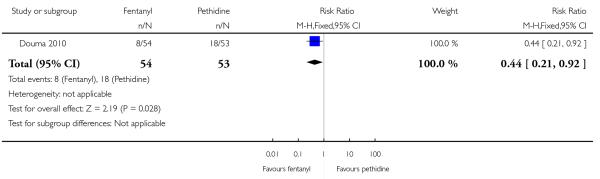

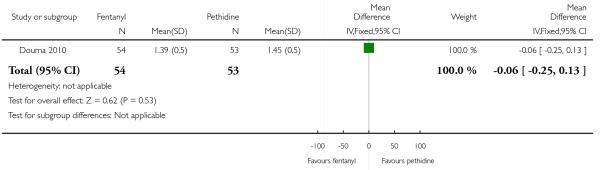

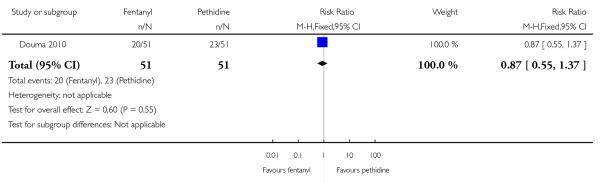

17. IV fentanyl versus IV pethidine

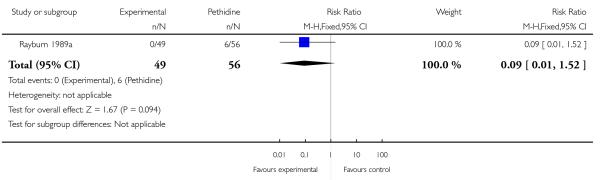

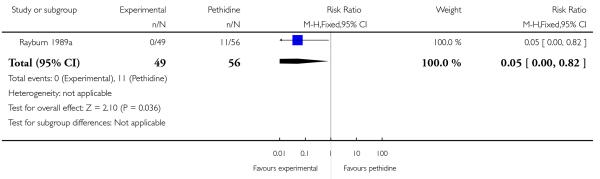

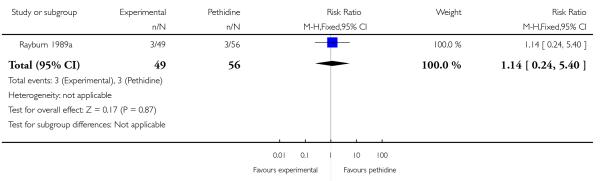

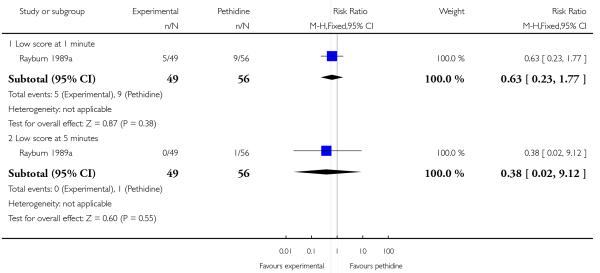

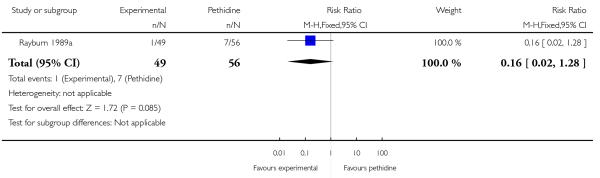

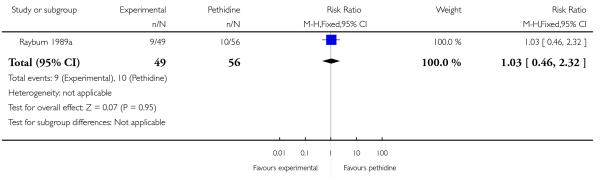

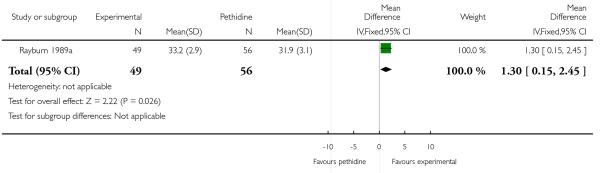

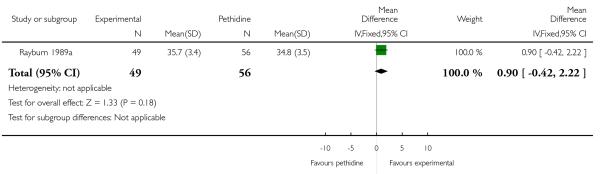

We included one study with 105 women in this comparison (Rayburn 1989a).

Primary and secondary outcomes

The mean maternal pain score was significantly lower one hour after drug administration for women allocated to the IV fentanyl compared with those in the IV pethidine group; however, women in both groups reported mean pain scores of approximately six on a 10 mm scale (MD −0.20, 95% CI −0.34 to −0.06).

Maternal sedation was significantly lower in women allocated to the IV fentanyl group compared with those in the IV pethidine group (RR 0.05, 95% CI 0.00 to 0.82). There were no statistically significant differences for all other reported outcomes including side effects, interventions in labour and outcomes for babies (Analysis 17.3; Analysis 17.4; Analysis 17.6; Analysis 17.7; Analysis 17.9; Analysis 17.11). The study, however, recruited women only during a limited time period Monday to Friday and allocation was not blinded due to the different half-lives of the treatment options.

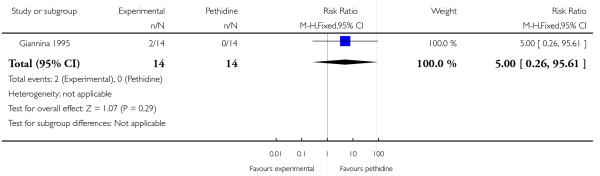

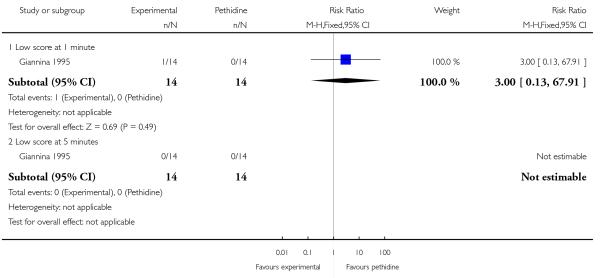

18. IV nalbuphine versus IV pethidine

We included one study involving 28 women compared IV nalbuphine with IV pethidine (Giannina 1995).

Primary and secondary outcomes

No outcomes relating to maternal pain during labour were reported.

This study reported estimable data for only two relevant secondary outcomes (caesarean section and low Apgar score at one minute), neither of which showed any significant difference between the two groups (Analysis 18.1; Analysis 18.2).

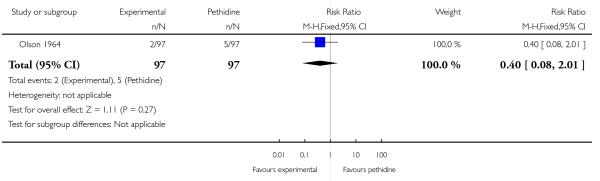

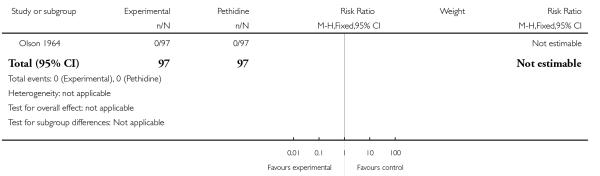

19. IV phenazocine versus IV pethidine

We included one study including 194 women compared IV phenazocine with IV pethidine (Olson 1964).

Primary and secondary outcomes

There was no statistically significant difference between groups for women’s satisfaction with pain relief (comparing the number of women with “fair” or “poor” pain relief) (RR 0.72, 95% CI 0.48 to 1.10). No other primary outcomes were reported.

Only one identified secondary outcome reported estimable data: nausea with vomiting. There was no statistically significant difference between the two groups for this outcome (Analysis 19.2).

20. IV butorphanol versus IV pethidine

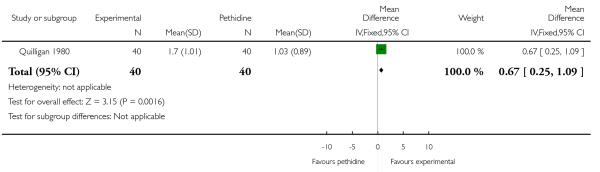

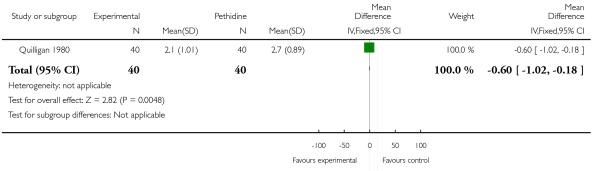

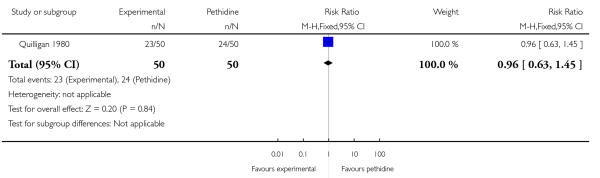

Three studies involving a total of 330 women compared IV butorphanol with IV pethidine (Hodgkinson 1979; Nelson 2005; Quilligan 1980).

Primary outcomes

One study (Quilligan 1980) involving 100 women (findings for these primary outcomes reported for 80 women) included two measures of women’s pain during labour; women’s reported pain relief and pain score. Women’s mean pain relief score was significantly higher for those in the group receiving butorphanol (MD 0.67, 95% CI 0.25 to 1.09). This finding was supported by data regarding reported pain scores one hour after drug administration which were lower for women in the butorphanol group (MD −0.60, 95% CI −1.02 to −0.18). The clinical significance of a difference of this magnitude (i.e. 0.6 on a 10-point scale) is more difficult to determine.

The other two studies comparing IV butorphanol with IV pethidine did not report any outcomes relating to women’s pain during labour.

Secondary outcomes

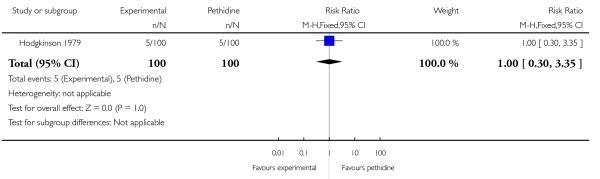

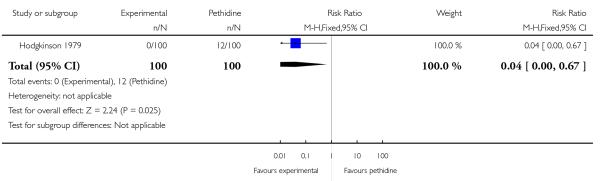

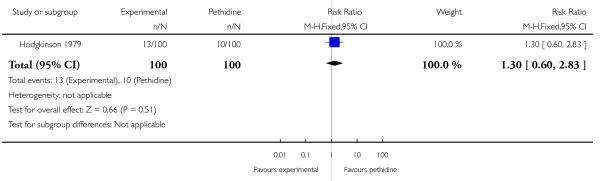

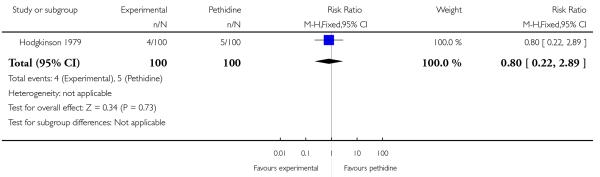

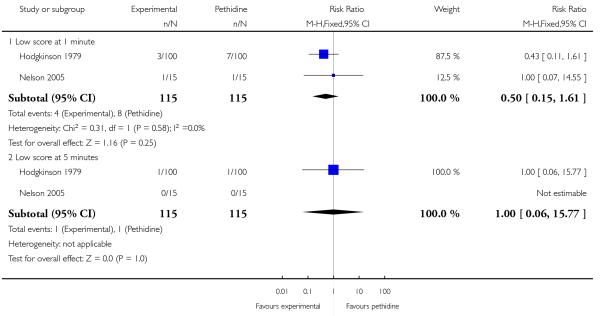

One study (Hodgkinson 1979) involving 200 women reported a lower incidence of nausea and vomiting associated with butorphanol compared with pethidine (0/100 in the butorphanol group versus 12/100 in the pethidine group; RR 0.04, 95% CI 0.00 to 0.67). Other secondary outcomes reported by one or more of the three studies within this comparison (second dose of analgesia required, epidural analgesia, assisted vaginal birth, caesarean section, Apgar score less than or equal to seven at one and five minutes) showed no statistically significant differences between groups (Analysis 20.3; Analysis 20.4; Analysis 20.6; Analysis 20.7; Analysis 20.8).

21. IV morphine versus IV pethidine

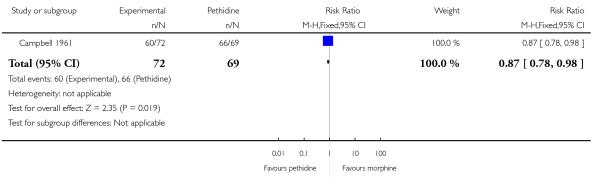

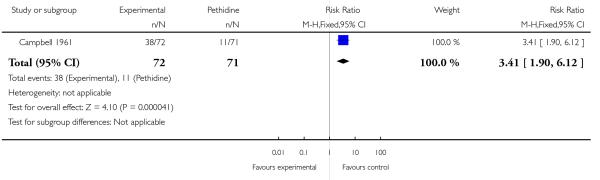

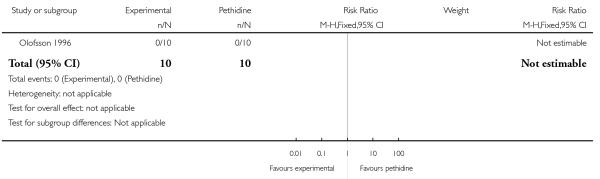

Two trials involving a total of 163 women compared IV morphine with IV pethidine (Campbell 1961; Olofsson 1996).

Primary and secondary outcomes

One study involving 143 women reported women’s satisfaction with pain relief assessed three days postpartum (Campbell 1961). Fewer women allocated to receive IV morphine during labour were satisfied with pain relief than those allocated to receive pethidine (RR 0.87, 95% CI 0.78 to 0.98), although the proportion of women who reported that they were satisfied was high in both groups (60/72 and 66/69).

Campbell 1961 also reported that women allocated to receive IV morphine were significantly more likely to request a second dose of analgesia compared with women allocated to receive IV pethidine (RR 3.41, 95% CI 1.90 to 6.12). This difference may simply reflect a lack of equivalence in the study doses of analgesia given (pethidine initial dose = 100 mg; morphine initial dose = 8 mg) rather than true differences between analgesic effects.

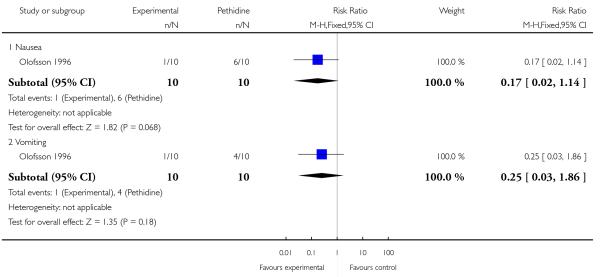

A second study which investigated this comparison (Olofsson 1996) included only 10 women in each trial arm. No statistically significant differences were found for each of the three secondary outcomes reported (nausea, vomiting and caesarean section), although the incidence of nausea was lower in the morphine group (6/10 pethidine versus 1/10 morphine; RR 0.17, 95% CI 0.02 to 1.14) (Analysis 21.3; Analysis 21.4).

22. IV nisentil versus IV pethidine

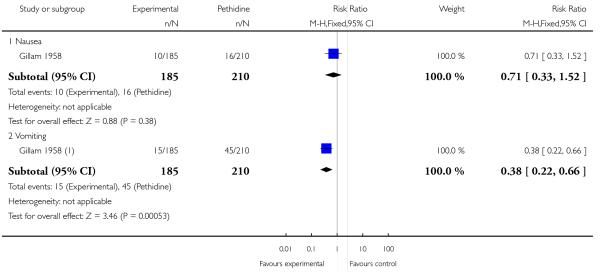

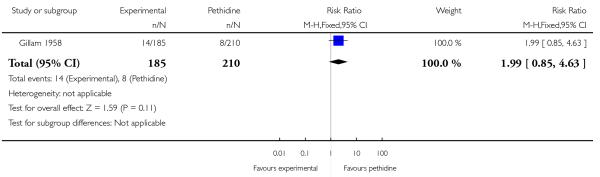

One study including 395 women compared IV nisentil with IV pethidine (Gillam 1958).

Primary and secondary outcomes

The study did not report any outcomes relating to women’s pain relief.

Women allocated to the nisentil group were less likely to suffer vomiting than those receiving pethidine (RR 0.38, 95% CI 0.22 to 0.66). There was also less risk of nausea in the nisentil group, although this difference was not statistically significant (RR 0.71, 95% CI 0.33 to 1.52).

The incidence of babies requiring resuscitation and/or ventilatory support was two times higher in babies born to women in the nisentil group (14/185) compared to those in the pethidine group (8/210) (RR 1.99, 95% CI 0.85 to 4.63). Although this difference is not statistically significant, and this finding may have occurred by chance, if this is a true reflection of differences between groups then this degree of harmful effect on newborn babies is not clinically acceptable.

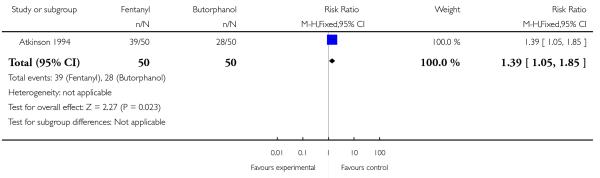

23. IV fentanyl versus IV butorphanol

One trial involving 100 women compared IV fentanyl with IV butorphanol (Atkinson 1994).

Primary and secondary outcomes

The study did not report any outcomes relating to women’s pain relief.

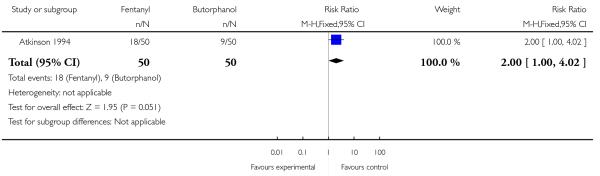

Women allocated to receive IV fentanyl were statistically significantly more likely to request additional doses of the study analgesia compared with women allocated to receive IV butorphanol (RR 1.39, 95% CI 1.05 to 1.85). The study author claims the study doses of drug were equivalent (IV fentanyl 50 to 100 mcg every one to two hours; IV butorphanol 1 to 2 mg every one to two hours). Additionally, women in the fentanyl group were twice as likely as those in the butorphanol group to go on to request an epidural (RR 2.00, 95% CI 1.00 to 4.02). Other women’s outcomes reported (drowsiness, caesarean section) showed no statistically significant difference between study groups (Analysis 23.3; Analysis 23.4).

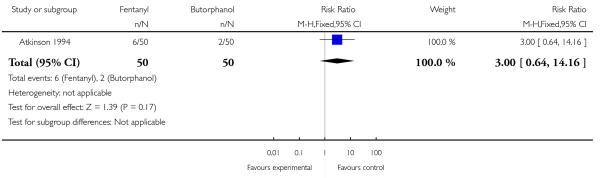

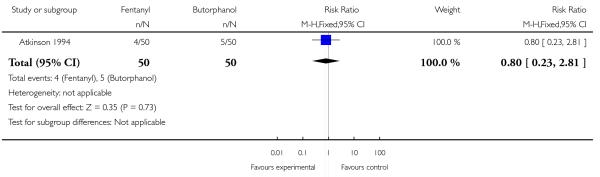

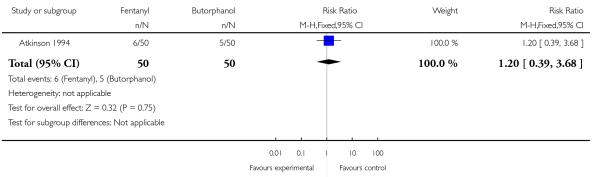

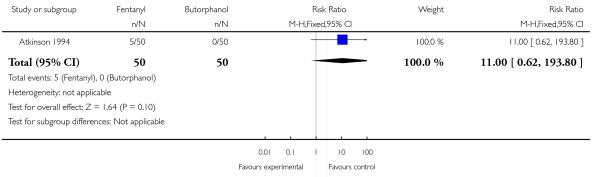

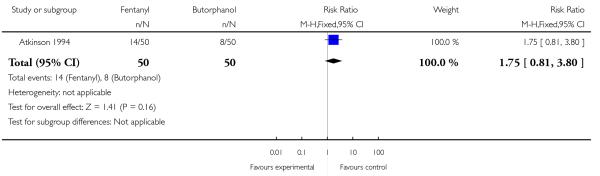

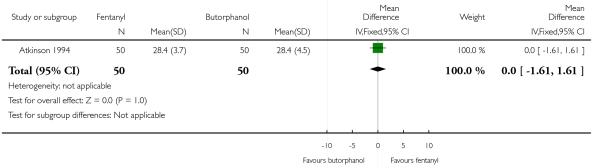

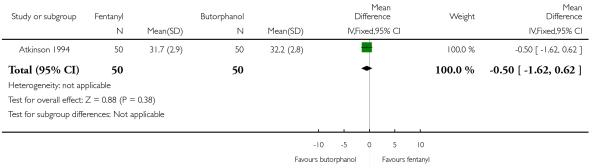

Whilst there were no statistically significant differences observed between groups for any of the neonatal outcomes reported (Apgar score less than seven at five minutes, naloxone administration, need for ventilatory support, neuro-behavioural score at two to four hours and neuro-behavioural score at 24 to 36 hours) babies born to women allocated to the fentanyl group were more likely to need ventilatory support (5/50 versus 0/50; RR 11.00, 95% CI 0.62 to 193.80) and naloxone administration (14/50 versus 8/50; RR 1.75, 95% CI 0.81 to 3.80) (Analysis 23.5; Analysis 23.6; Analysis 23.6; Analysis 23.7; Analysis 23.8; Analysis 23.9).

Intravenous patient controlled opioids for pain relief in labour

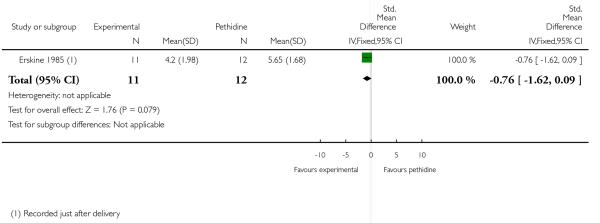

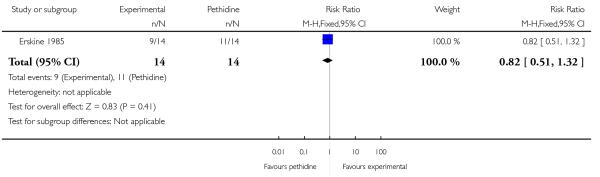

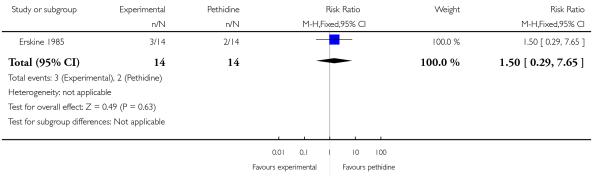

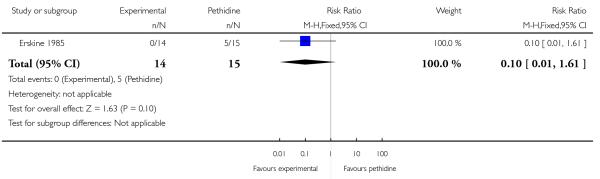

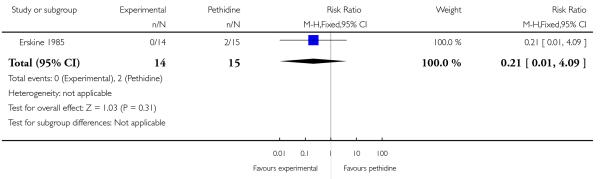

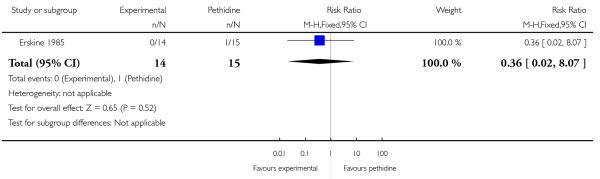

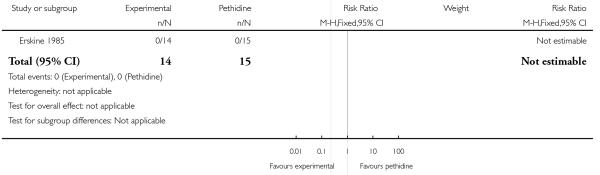

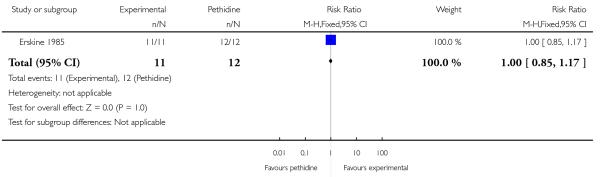

24. PCA pentazocine versus PCA pethidine

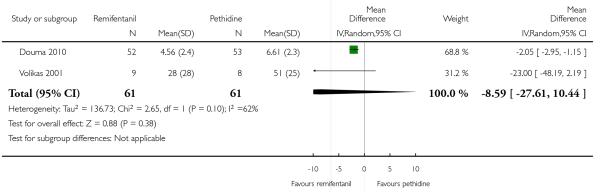

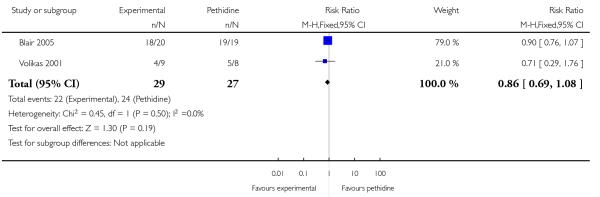

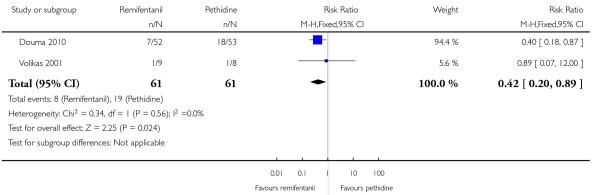

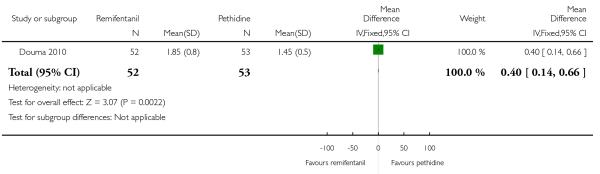

One trial involving 29 women compared PCA pentazocine with PCA pethidine (Erskine 1985).