Abstract

Young children who are exposed to traumatic events are at risk for developing posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). While effective psychosocial treatments for childhood PTSD exist, novel interventions that are more accessible, efficient, and cost-effective are needed to improve access to evidence-based treatment. Stepped care models currently being developed for mental health conditions are based on a service delivery model designed to address barriers to treatment. This treatment development article describes how trauma-focused cognitive-behavioral therapy (TF-CBT), a well-established evidence-based practice, was developed into a stepped care model for young children exposed to trauma. Considerations for developing the stepped care model for young children exposed to trauma, such as the type and number of steps, training of providers, entry point, inclusion of parents, treatment components, noncompliance, and a self-correcting monitoring system, are discussed. This model of stepped care for young children exposed to trauma, called Stepped Care TF-CBT, may serve as a model for developing and testing stepped care approaches to treating other types of childhood psychiatric disorders. Future research needed on Stepped Care TF-CBT is discussed.

Keywords: stepped care, posttraumatic stress disorder, trauma-focused cognitive-behavioral therapy, young children

Young children are exposed to a wide range and frequency of traumatic events (Finkelhor, Ormrod, & Turner, 2009), conferring substantial risk for the development of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD; Finklehor et al., 2009; Scheeringa & Zeanah, 2008). Evidence-based practices (EBP) for young children exposed to trauma have been established (e.g., Cohen, Deblinger, Mannarino, & Steer, 2004; Scheeringa, Weems, Cohen, Amaya-Jackson, & Guthrie, 2011), but many children in need of EBP do not receive it (Essau, Conradt, & Petermann, 2002). Reasons why include limited availability of trained therapists, costs, stigma, and logistical barriers such as time, work demands, child care, and transportation (Bringewatt & Gershoff, 2010).

Service delivery approaches that address treatment barriers are critically needed. Stepped care is one such approach that may provide treatment in a more efficient, accessible, and cost- effective way than standard treatment delivery systems. For example, stepped care models provide treatment in steps where the patient is carefully monitored for improvement, and the patient ends treatment once improvements have been obtained. Stepped care delivery models usually begin with less therapist time and more convenient interventions for patients, and, if indicated based on a predetermined criteria, progress to more intensive care (e.g., weekly therapist-directed therapy). Alternatively, standard treatment delivery systems often have one mode of treatment that demands intensive therapist time and requires the patient to attend weekly sessions until the entire treatment model is completed.

Stepped care approaches are being developed to address mental health conditions (National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health, 2011) such as adult depression (Franx, Oud, Lange, Wensing, & Gro, 2012), obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD; Tolin, Diefenbach, & Gilliam, 2011), and childhood anxiety (van der Leeden et al., 2011). Franx et al. (2012) suggest that there are challenges as well as advantages to implementing stepped care in different settings. A challenge may be that clinicians will need to routinely utilize structured measurement tools to determine if additional steps are indicated. An advantage may be that clinicians may not spend as much time with patients who are receiving the less intensive steps and will be able to provide different treatment options to patients instead of one standard treatment.

The evidence on stepped care models is preliminary but promising. In one of the first randomized clinical trials comparing a two-step treatment for adult OCD versus standard therapist-directed treatment, results suggest that there were equally significant decreases in OCD symptoms and similar satisfaction scores among the two conditions. Importantly, stepped care treatment had significantly lower costs to patients and third-party payers than standard care (Tolin et al., 2011). In one of the first open trials of a stepped care model for childhood anxiety (e.g., separation anxiety, social phobia, specific phobia, and generalized anxiety disorder), 133 children (ages 8 to 12 years) participated in a three-step CBT protocol that added more sessions with intensifying parent involvement with each step. Step One consisted of 10 child and 4 parent CBT sessions, with Steps Two and Three each adding 5 parent-child CBT sessions. Intent-to-treat analysis indicated that 45% of the children responded to Step One, 17% responded to Step Two, and 11% responded to Step Three, for a total of 74% of the children no longer meeting criteria for an anxiety disorder (van der Leeden et al., 2011).

A stepped care model with two steps has been developed for young children exposed to trauma. This stepped care model for children exposed to trauma is called Stepped Care TF-CBT. Step One is based on Preschool PTSD Treatment (Scheeringa et al., 2011), Trauma-Focused Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (TF-CBT; Cohen et al., 2004), research on the use of minimal therapist assistance (Hirai & Clum, 2006; Salloum, 2010), telehealth, bibliotherapy (e.g., Lyneham & Rapee, 2006), and computer-assisted treatments (e.g., Khanna & Kendall, 2008). Step One involves parent-led therapist-assisted treatment which includes three face-to-face meetings with a therapist, bibliotherapy where the parent and child have 11 parent-child meetings at home working in an empirically based CBT workbook, weekly telephone support, and web-based psychoeducation. Step Two is standard TF-CBT, therapist-directed treatment.

The purpose of this article is to discuss specific considerations for the development of Stepped Care TF-CBT, and to describe this stepped care model for young children exposed to trauma. Specific considerations for the development of Stepped Care TF-CBT that are addressed include therapeutic approach, types of steps, number of steps, training of providers, entry point, and inclusion of parents. The components of Stepped Care TF-CBT include Step One, Maintenance Phase, and Step Two. Each component is described and issues such as noncompliance, determining responder status and monitoring treatment, flexibility, and implementation are discussed. A case example to illustrate Stepped Care TF-CBT is provided.

Stepped Care

Generally, there are two guiding principles underlying stepped care models. First, the initial step needs to be intensive enough to lead to likely improvements and least restrictive in terms of the therapist time. Other factors that minimize clients’ time and inconveniences may also be considered as least restrictive when developing the steps. Provider cost (i.e., therapist time) is a major factor when developing stepped care with health care costs a major concern. Second, stepped care models need to be “self-correcting” with systematic monitoring systems that indicate when the client needs to be stepped up (Bower & Gilbody, 2005, p. 11). Self-correcting monitoring systems have preestablished criteria with selected measures that are used to indicate if treatment should end or if more treatment is needed. Self-correcting monitoring systems recognize that not all individuals need the full package of evidence-based treatments. The underlying assumptions of stepped care models are that the lower-intensity steps are equivalent in outcomes to standard care at least for a proportion of clients, are more efficient and reduce provider costs, and are acceptable to providers and consumers (Bower & Gilbody).

Considerations for the Development of Stepped Care TF-CBT

Therapeutic Approach

The therapeutic approach should be one of the first considerations in developing a stepped care model for children exposed to trauma. Treatment modalities may differ within a stepped care model but there must be supporting evidence for the therapeutic methods being delivered. TF-CBT is the most well-established treatment for childhood PTSD (Silverman et al., 2008). CBT for childhood trauma has demonstrated efficacy with children of all ages, from diverse backgrounds, in individual or group settings, and with children who have experienced multiple and different types of traumatic events. In addition, CBT has shown to be effective with diverse presenting trauma symptoms (e.g., with or without full PTSD diagnosis, with or without other comorbid disorders such as depression, anxiety, behavioral problems or complex trauma presentations; e.g., Cohen et al., 2004; Scheeringa et al., 2011). Developing a stepped care model for childhood PTSD that can treat all types of traumas is important for several reasons, including generalizability, training of clinicians, and ease of implementation. Some models may use different theoretical approaches for different steps (Bower & Gilbody, 2005). Eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR), which has gained some empirical support for the treatment of childhood trauma (Fleming, 2012), could have been provided as Step One, with TFCBT as Step Two, but this approach requires clinicians to be trained and certified in two different approaches, which limits treatment availability. CBT is used to treat many disorders and the specific therapeutic methods make CBT amenable to clearly defined steps (Bower & Gilbody). Therefore, CBT, the most well-studied individual therapy model, was the therapeutic approach utilized for Stepped Care TF-CBT.

Types of Steps

It is important to consider what treatment should be provided for each step when developing a stepped care model. For example, though medication may be considered in a stepped care model (Bower & Gilbody, 2005), it was not included in Stepped Care TF-CBT because (a) psychotherapy is considered the first-line treatment before medication for childhood PTSD (Cohen et al., 2010) and (b) concerns about the acceptability of medication use in young children (Stevens et al., 2009). Self-help approaches may also be part of stepped care approaches, but were not included in the present model given limited data on the effectiveness of self-help methods for PTSD (Hirai & Clum, 2006).

Offering group treatment as a first step is a viable option within a stepped care model. For example, for war-exposed adolescents, Layne et al. (2009) developed a three-step model consisting of a classroom-based intervention to provide psychoeducation and skill building, a targeted trauma and grief-focused therapy group, and referral to community mental health for those needing additional treatment. Similarly, for children after a natural disaster, Jaycox et al. (2010) conducted a field trial with school-based group CBT as the first tier (or step) and clinic-based TF-CBT as the second tier (step two). Schools are ideal for stepped care models that begin with group intervention: they contain large numbers of children who are in need of treatment at one time, and classrooms provide ideal settings for conducting group treatment. However, school-based models may not be transportable to community mental health settings. Additionally, the last step in school-based models is often a referral to community mental health treatment, but for those children being referred, barriers such as time and transportation still remain (Jaycox et al.). Therefore, we sought to develop a TF-CBT stepped care model that could be used in outpatient and home settings.

Number of Steps

Key considerations for determining the number of steps should be length of treatment, number of assessments needed for determination of stepping up or not, and providing steps that result in significant improvements for a proportion of children. To ensure that the entire Stepped Care TFCBT protocol was not longer than the typical most well-established treatment (standard TF-CBT typically takes 12 to 16 weeks), all steps needed to be completed within 12 to 16 weeks. Patients who responded to the first step needed to have similar outcomes as those who responded after all of the steps. Therefore, the first step needed to be long enough or with enough intensity to result in a substantial number of children improving after Step One. Also, the number of steps established the number of assessments required to determine if stepping up was indicated or not. For these reasons, Stepped Care TF-CBT has two steps.

Training of Providers

Another consideration for developing stepped care for children exposed to trauma should be training of providers. Dissemination and implementation of evidence-based treatments has been a major challenge in the childhood trauma field (Self-Brown, Whitaker, Berliner, & Kolko, 2012). However, with the TF-CBT web-based course and training methods such as learning collaboratives, ongoing supervision, and train-the-trainer (Cohen & Mannarino, 2008), TF-CBT has become a widely used EBP. In fact, in a recent study of 262 clinicians providing treatment to maltreated children, TF-CBT was the most widely used evidence-based treatment (Allen, Gharagozloo, & Johnson, 2012). By using a method such as TF-CBT that is well into the dissemination phase of treatment development (e.g., CATS Consortium, 2007) in a stepped care model, training therapists on the implementation of Stepped Care TF-CBT may not take as long as it would if a completely new treatment method were being provided. However, training for Step One on how to implement the parent-led therapist-assisted treatment needed to occur even for those therapists already trained in Preschool PTSD Treatment (Scheeringa et al., 2011) and TF-CBT. Training needs depended on the level of training already obtained for Preschool PTSD Treatment (Scheeringa et al.) and TF-CBT (Cohen, Mannarino, & Deblinger, 2006). Methods for training on Stepped Care TF-CBT consisted of similar training requirements for TF-CBT (Cohen & Mannarino, 2008) such as the TF-CBT web-based course (http://tfcbt.musc.edu/), live training plus ongoing consultation and supervision, learning collaborative or mixed learning methods.

Entry Point

In terms of the organization of the steps, one question to consider should be the entry point for different patients. There has been little research to identify beforehand those children who will respond to the lower level of care, and those children who will respond only to the full treatment package of the more intensive treatment. Research is needed to examine predictors that may indicate the best initial level of care such as severity of PTSD, comorbid syndromes, cognitive factors, and neurobiological factors. With a goal of providing the least restrictive treatment as the first step, and in the absence of data on predictors to suggest which children would respond better to Step One versus starting with Step Two, Stepped Care TF-CBT currently begins all children with Step One.

Parent Role

For stepped care models with children, one consideration should be whether the first step will include the parent only, the parent and child, or the child only. Involving parents and children is critical in the treatment of young children with PTSD. Findings from three randomized clinical trials suggest that while parent-only treatment for child sexual abuse is helpful in terms of increasing parenting skills and addressing child externalizing behavior, child participation in therapy, including young children, results in greater improvements in child PTSD than parent-only treatment (Deblinger, Lippmann, & Steer, 1996; King et al., 2000). Therefore, we include parents in both steps, with the parent actually leading the treatment—with therapist assistance— in the first step. A major barrier for parents seeking and completing treatment is the desire to solve the problem on their own, resulting in reduced help-seeking behaviors (Kessler et al., 2001; Pavuluri, Luk, & McGee, 1996; Thurston & Phares, 2008). Parent-delivered treatment in which parents take responsibility for their children's improvement may address this barrier and improve parents’ self-efficacy (Leong, Cobham, de Groot, & McDermott, 2009). Having parents lead the first step also allows parents to individualize the treatment and include culturally relevant strategies since they know their child better than the therapist. These studies support the rationale for including parents and children in Stepped Care TF-CBT.

An important research question that requires further exploration is the influence of the parent's trauma exposure, distress level, anxiety or PTSD on completing the parent-led treatment and on treatment outcomes. Preliminary evidence from two case reports suggests that as long as parents can manage their posttraumatic stress symptoms sufficiently to complete the trauma-related activities with the child, children can improve in PTSD symptoms despite the parent's posttraumatic stress severity (Scheeringa et al., 2007). In an open pilot trial of a parent-only group CBT with 24 parents whose children had various types of anxiety disorders (two with PTSD) in which children completed CBT homework with their parents at home, parents with anxiety disorders reported more improvement in their children's anxiety than parents without anxiety disorders (Thienemann, Moore, & Tompkins, 2006).

Stepped Care TF-CBT Components

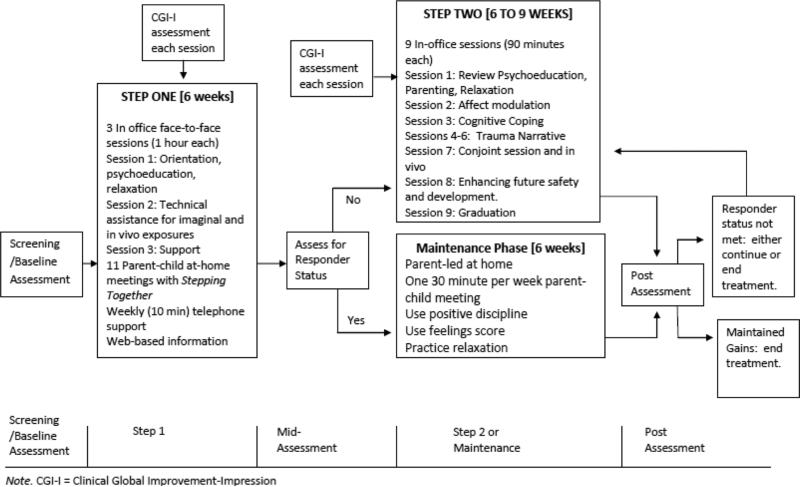

Figure 1 provides a graphic representation of the assessment and treatment flow of Stepped Care TF-CBT. The following section describes the components of Stepped Care TF-CBT.

Figure 1.

Treatment model for Stepped Care TF-CBT for young children

Step One

Step One of Stepped Care TF-CBT includes four main components: three in-office therapist-led sessions, a parent-child workbook (Stepping Together), scheduled weekly phone meetings, and information from the National Center for Childhood Traumatic Stress Network (NCTSN) website. Information from the NCTSN website (http://www.nctsn.org/) is printed and provided for parents who do not have access to the internet. However, in the United States about 68% of households have internet access (U.S. Department of Commerce, 2011). Research suggests that some face-to-face contact may increase treatment compliance and satisfaction by children and parents (Spence, Holmes, March, & Lipp, 2006). Therefore, three face-to-face therapy sessions are included in Step One. The first meeting is designed to provide a general orientation to Step One (materials, structure, rationale, schedule and time commitment, and guidelines). The second meeting is strategically timed at 2 weeks after the first in order to provide technical assistance for relaxation strategies and to help establish the trauma exposures meetings (which are called Draw It, Imagine It, and Next Step). The purpose of the final meeting is to provide support and motivation to complete Step One.

The parent-child workbook, called Stepping Together, is based on the CBT Preschool PTSD Treatment manual (Scheeringa, Amaya-Jackson, & Cohen, 2002) that has been used in a National Institute of Mental Health funded treatment study with young children experiencing PTSD due to a range of traumatic events (Scheeringa et al., 2011). Stepping Together is written at a sixth grade level and in a user-friendly format (e.g., icons, white space, call-out boxes, checklists). The techniques used in Stepping Together are consistent with the core components of effective treatment for trauma-exposed children, including stress management techniques, behavior management and skill building activities (e.g., gaining knowledge about trauma reactions and identifying feelings), having the child tell their story about the trauma in an organized fashion, and participation in structured gradual exposure to trauma reminders (Amaya-Jackson & DeRosa, 2007; NCTSN, 2012).

Stepping Together provides activities for the parent to work with the child to complete the child's book called My Steps. There are a total of 11 parent-child meetings that occur at home: after both in-office Sessions 1 and 2, there are 4 parent-child meetings at home; after in-office Session 3, there are 3 parent-child meetings at home. The first 4 parent-child meetings focus on coping skills—behavior management, relaxation, affect identification and regulation— and telling the story about what happened to identify and rate the “scariness” of the trauma reminders, developing a “scary ladder” (i.e., stress hierarchy) of trauma reminders. During the first 4 parent-child meetings, children learn about the “feelings score” and are taught to rate their feeling, such as “none scared,” “medium scared,” “a little scared,” and “a lot scared.” The feelings score helps the child identify how much s/he is experiencing the feeling and to communicate with the parent about the intensity of the feeling. Parent-child meetings 5 through 8 include trauma exposure activities where the child begins with the least scary trauma reminder, drawing a picture of the reminder, imagining it for 30 seconds and then with the parent completing a Next Step, which is an in vivo activity (i.e., exposure). The child moves up the “scary ladder” to reminders that are scarier, repeating the same steps: drawing a picture of the trauma reminder, imagining it for 30 seconds, and completing a Next Step. During the final three parent-child meetings, the child and parent complete the trauma exposure activities, discuss a relapse plan, and review the child's My Steps book, which has all of the activities and worksheets that they have worked on together. For more information about Step One, see Salloum and Storch (2011). In families with two caregivers, it is recommended that only one parent lead the parent-child meetings, while the other parent provides support and encouragement. For example, if there are several children in the family, the non-lead parent may arrange to spend time with the other children allowing the lead parent and child to have their meetings uninterrupted. It may be easier for the child to talk about the traumatic event with the lead parent versus talking with both parents.

Phone support is included to encourage compliance and completion of Step One. In fact, preliminary evidence on computer-based therapy with children with anxiety disorders suggests that adding weekly phone contact may help decrease attrition and improve completion of assignments (Carlbring et al., 2006, 2007). The purpose of the phone meetings in Step One is to provide motivation, support, and technical assistance. For example, for the first two phone calls the therapist (a) asks how the parent is doing with the parent-child workbook; (b) asks how the behavior plan is progressing and problem-solves if needed; (c) provides positive, motivational comments to encourage the parent and problem-solve if the parent has not completed the meetings; (d) asks the parent about their own social support and incorporation of relaxation management; and (e) problem-solves with the parent about potential barriers to completing treatment. The third and fourth phone calls focus on helping the parent to problem-solve ways to complete the meetings if they are behind and to address any questions or concerns they might have about the Next Steps (trauma exposures). The purpose of the fifth and sixth calls is to explain the importance of completing the final three parent-child meetings, which focus on the integration of the trauma narrative and relapse prevention, offer encouragement and support, and encourage completion of the workbook.

A web-based component used in Stepped Care TF-CBT provides psychoeducation to the parent, and through two video demonstrations helps parents teach their children the relaxation exercises and demonstrates how to perform the exposure activities. The parent-child workbook includes the address of the NCTSN website to help the parent learn more about childhood trauma. The link to this website is available on a password-accessible Stepping Together website that also contains two video demonstrations so that parents may review this information at their convenience. For parents who do not have internet access, the therapist prints the most salient handouts from the NCTSN, such as “What is Child Traumatic Stress,” and shows the parent the video demonstrations during Sessions 1 and 2.

Noncompliance With Step One

Noncompliance with Step One is addressed in four main ways. First, if parents are not completing the parent-child meetings or activities, the therapist problem-solves with the parent about ways to complete the activities as scheduled. Second, if the parent has not completed the parent-child meetings as scheduled, the parent is encouraged to make up the meetings and activities in the following week. Third, as a general rule, if the parent has not completed three of the four meetings before the first in-office therapy session, stepping up to therapist-directed care (Step Two, standard TF-CBT) may be indicated and should be discussed with the parent. Fourth, in cases where it is judged by the parent and therapist that the child requires more intensive clinical monitoring (i.e., the parent is not making significant progress in implementing Step One or the child's behavior has significantly worsened), Step One should be terminated and Step Two started.

Some children who are participating in trauma-focused therapy may have temporary periods of minor regression or worsening of symptoms before they improve. It may be that parents perceive their child is getting worse if the child starts talking more about what happened, when in fact not avoiding traumatic reminders may be a sign of the child improving. Therefore, it is important to have a monitoring system that helps define and determine significant worsening so that the child with minor worsening does not terminate Step One unnecessarily, but that the child with significant clinical worsening steps up to therapist-directed care. Also, to minimize burden on the parent, child and therapist, we recommend the use of brief rating tools such as the Clinical Global Impression–Improvement Scale (Guy, 1976; Research Unit on Pediatric Psychopharmacology Anxiety Study Group [RUPP], 2001) to be completed once a week (either in-session or via phone) by the parent and therapist, and the child, if aged 7 or above. The CGI-Improvement (Guy, 1976) modified version that has been used in child treatment trials (e.g., RUPP, 2001) is based on an 8-point rating scale of overall improvements since the first assessment (8 = very much worse; 7 = much worse; 6 = minimally worse; 5 = no change; 4 = minimally improved; 3 = improved; 2 = much improved; 1 = free of symptoms). A rating of 1, 2, or 3 is used to indicate treatment response. Clinical worsening is defined as three consecutive ratings by the therapist or parent of 6 or a rating of 7 or 8. If one party indicates clinical worsening and the other does not, the parent and therapist (and child, if age appropriate) should discuss and make a determination about continuing Step One while monitoring improvement status or stepping up. In some instances, the therapist may want to consult with another mental health professional about the severity of the clinical worsening rating to obtain another opinion and then discuss this with the parent before deciding to end Step One. In some cases, it may be decided that an additional session be conducted in Step One to address the noted concern. The use of additional sessions is discussed further in the Flexibility section below. An assessment may be conducted to provide more insight into whether Step Two is needed.

Maintenance Phase

If the child responds to Step One (see Responder Status section below), the parent and child begin the maintenance phase. The maintenance phase is designed to promote open communication between the parent and child and to encourage the parent and child to continue to use the tools they learned in Step One. During this time, parents have one 30-minute parent-child meeting per week. The purpose of these meetings is for parent and child to spend time together having fun. The parent is informed that she or he does not need to talk about the trauma anymore unless the child wants to talk about it. An aim of these meetings is to strengthen the relationship between the parent and child and it is recommended that the meetings start or end with a relaxation exercise. In fact, the parent is asked to practice the relaxation exercises three times a week with the child. Parents are also encouraged to continue praising the child for positive behavior and using the behavior plan if it was established in Step One. Lastly, parents are encouraged to continue to have the child use the feeling scores.

Step Two

If the child does not respond to Step One, s/he steps up to Step Two to receive nine (90 minute) in-office, therapist-directed TF-CBT therapy sessions. The treatment components (see Figure 1) that are common to standard TF-CBT are delivered within these sessions (see Cohen et al., 2006, for more information about standard TF-CBT). Since the child has typically already received three therapist-directed sessions in Step One, some of the components may be combined and reviewed in one session. Parents may choose to complete Step Two over 9 weeks with weekly sessions, or have some weeks with double sessions to complete treatment faster.

Flexibility

Stepped Care TF-CBT allows for two additional sessions to be provided in Step One or Two as needed. Therapists are encouraged to use these additional sessions judiciously. Examples of when additional sessions may be needed in Step One include the need to address boundary issues with a child who may be acting out sexually or inappropriately, or when safety issues need to be addressed if there is ongoing domestic violence or another traumatic event. Additional sessions may be provided in Step Two when any particular component of TF-CBT needs to be addressed further, such as when a child is having difficulty with affect modulation.

Step One Responder Status and Step Two Monitoring

The threshold to end treatment after Step One is stringent since treatment will be terminated and gains need to be maintained. The decision to end treatment after Step One is based on meeting responder status. Responder status uses multiple methods, including a semistructured diagnosis measure, below the cutoff score on a trauma symptom self-report measure and an independent evaluation of overall improvement. Responder status is defined as children who have three or fewer PTSD symptoms as measured by a semistructured diagnostic interview with parents, the Diagnostic Infant and Preschool Assessment (DIPA; Scheeringa, 2008), or a total score of 40 or less on the Trauma Symptom Checklist for Young Children Posttraumatic Stress total score (TSCYC-PTS; Briere, 2005) and a score of 3 (improved), 2 (much improved), or 1 (free of symptoms) on the Clinical Global Impression–Improvement scale (RUPP, 2001). The criterion of three or fewer PTSD symptoms is slightly below the average number of PTSD symptoms preschool children had after participating in 12 weekly therapist-directed CBT sessions for preschool PTSD (Scheeringa et al., 2011).

Step Two includes a monitoring system to individualize the optimal amount of treatment for each child. Allowing early termination of Step Two prevents children who respond before the completion of Step Two, perhaps due to the cumulative effects of Step One and Step Two treatment, from unnecessarily receiving the full treatment package.

To monitor if responder status is met prior to the completion of Step Two, the parent and therapist complete the CGI-I independently at the beginning of each Step Two session. If both parent and therapist note two consecutive weeks of a CGI-I score of 3 (improved), 2 (much improved), or 1 (free of symptoms), and the the child is not in the middle of the trauma narration or conjoint component, then the TSCYC-PTS is administered. If there is a total score of 40 or less on the TSCYC-PTS, the therapist discusses with the parent the option of termination or continuing treatment (i.e., parent preference). If Step Two is terminated, a final treatment session occurs to end treatment with the child, which includes discussion of progress and relapse prevention. After the final session, a postassessment is scheduled for the following week.

Implementation Considerations

Exploring how Stepped Care TF-CBT generalizes to various settings is important to the implementation of Stepped Care TF-CBT. For example, children in community-based settings often have comorbidity, including externalizing symptoms, and are from low-income families with single caregivers (Southam-Gerow, Weisz, & Kendall, 2003). It may be that these children need additional therapist-led sessions to address behavioral problems. In addition, the therapist may need to problem-solve with single caretakers about when they can find time at home to have the parent-child meetings. Further, parents who are not engaged in Step One by the second parent-child meeting need to be stepped up. Another implementation consideration is whether phone meetings and assessments for responder status are reimbursable to the provider, as well as the feasibility of implementation of Stepped Care TF-CBT over time.

There are some children for whom stepped care is contraindicated. Exclusions to participating in Stepped Care TF-CBT include the following: (a) there is no nonoffending parent to participate in treatment or a perpetrator still lives in the home (e.g. mother's boyfriend, sibling); (b) any condition that would limit the caregiver's ability to understand CBT and the child's ability to follow instructions; (c) parent reading level below the seventh grade (currently Stepping Together is only in English so fluency in English is also required); (d) parent has had substance use disorder within the past 3 months; and (e) the child or parent is suicidal.

Case Example

The following case illustrates the components of Stepped Care TF-CBT: three in-office therapist sessions, 11 parent-child meetings at home using the Stepping Together parent-child workbook, brief phone support, a web-based component, and assessments.

Presenting Problem

A 5-year-old Caucasian boy and his mother participated in Stepped Care TF-CBT. The child was experiencing posttraumatic stress symptoms due to an accident, subsequent medical procedure, and hospitalization. Three months before starting Stepped Care TF-CBT, the child was pushed off a ledge by another young boy and broke his arm. The boy was hospitalized for 3 days after the accident, had surgery on his arm, and underwent physical therapy. At baseline assessment, the mother reported the following about her child: overly worried about the use of his arm, breathing increased if he was reminded about what happened, avoided doctors and hospitals, did not want to play basketball although physically able, had difficulty falling asleep, was less happy and very clingy, and had become worried about dying. The mother reported that the teacher reported that the child was having trouble with things he did not have difficulty with before (i.e., decreased concentration). Due to the severity of the child's symptoms, the mother indicated that she expected about 50% improvement (on a scale from 1 to 100%) at the end of treatment. The child had 15 symptoms and 5 areas of impairment on the DIPA, a CGI-Severity rating of 5 “severe symptoms,” and a 39 on the TSCYC-PTS. The therapist was a registered mental health clinical intern who practiced at a nonprofit community trauma center and was trained in Stepped Care TF-CBT by the first three authors. The person who completed the assessments was a registered marriage and family therapist intern who practiced at the same community trauma center and was trained by the first, second, and last author on the assessments.

Session 1, Parent-Child Meetings 1 to 4

The therapist met with the mother and child and explained that they would have four parent-child meetings at home and they would begin to learn tools to help make the child feel better. The parent reported that she thought that since the baseline assessment, her child had “minimally improved.” The therapist met with the child and the mother in the office and had the child decorate his My Steps book. The therapist worked with the child on the first page of the book and asked the child to state what had happened that was scary. The child reported that his friend pushed him off the ledge and he broke his arm. The therapist wrote this down, but did not ask any other questions. The therapist then taught the mother and child belly breathing and muscle relaxation. The therapist then met with the mother to encourage her to go to the NCTSN website to learn more about childhood PTSD, plan the scheduled phone calls, and briefly review the first four parent-child meetings at home.

The parent and therapist spoke on the phone after the first two parent-child meetings. The parent reported that the child liked the meetings and that they both found them helpful. However, during the second week, the mother reported via the phone that her child had become “much worse” after having an experience where he swallowed water while swimming in the ocean. The parent was concerned about continuing the parent-child meetings as she reported that her child seemed to have a panic attack after the water incident. The therapist encouraged the mother to continue to use the tools that they had learned in the first three meetings, and then come in for Session 2.

Session 2, Parent-Child Meetings 5 to 8

Since the parent had not completed parent-child meeting four, the therapist completed the fourth meeting in the office with both the child and parent together. They completed the My Steps worksheet where the child is asked what happened, along with several follow-up questions such as, “What did you see?” “What did you hear?” “What did you smell?” and so on. The therapist had the mother write in the child's book as he answered the questions. She wrote, “I was playing on a wall at the party and my friend pushed me off and I landed on my arm. Mommy and my grandmother were there. They took me to the hospital. I was afraid my bone was going to come out of my arm. My arm hurt really bad, and they put these long pins in my arm.” The therapist worked with the child to complete the scary ladder. The not-too-scary thing was “watching TV at the hospital.” The two medium scary things were “when I thought my bone was going to come out of my arm” and “hearing all of the machines” (referring to the machines in the hospital), and the most scary was “getting the pins in my arm.” The parent was given Part II of the Stepping Together workbook.

During the next four parent-child meetings at home, the parent and child discussed safety such as not pushing other children or climbing on things when his mother was not around or didn't know. He continued to practice ways that he could calm himself down such as thinking about his “happy place,” using relaxation and practicing muscle exercises (which consisted of tightening his muscles and relaxing them), and using his feelings score to identify his feelings and let his mother know how he was feeling.

During the fifth parent-child meeting, the child worked on the not-too-scary reminder (watching TV at the hospital) by drawing about it, thinking about it, and then doing a Next Step. For this Next Step his mother wrote in the child's My Steps book, “Watched a Mario movie in bed with pillows propping up his left arm. We drank apple juice just like we did at the hospital. We remembered how it felt to do all this and how his arm felt. He said his scary score was 3 (a lot scared) in the beginning and then 0 (none scared) at the end when we practiced his relaxation exercise.”

During parent-child meeting six, the parent had the child draw a picture of the medium scary reminder (My bone was going to come out of my arm), imagine it for 30 seconds, complete a Next Step, and then practice the relaxation exercises. The parent wrote in the My Steps book for this Next Step, “We went to the wall where the accident happened. At first he was a little scared. We looked at the wall. He jumped off it with my assistance. He played with a ball he found.” During parent-child meeting seven, the child drew and imagined for 30 seconds the reminder about the machines at the hospital. For the Next Step the parent and child talked about when the child was in the hospital. The parent wrote in the My Steps book for this Next Step, “We talked about the ER and hospital stay. We remembered the sounds, visitors, and what we ate and drank.” During the eighth parent-child meeting the child drew and imagined the pins in his arm. For the Next Step the child looked at the X-ray picture of the pins in his arm. The parent wrote in the My Steps book for this Next Step, “We looked at the X-rays that shows the pins in his arm.”

Session 3, Parent-Child Meetings 9 to 12

At the third session, the child reported to the therapist that he had started playing basketball. The child and mother reviewed with the therapist his drawings in the My Steps book. When discussing the final Next Step, the therapist and mother talked with the child about the “scary pins” that were in his arm actually being “helper pins” because they made his arm feel good and he could play again. The child liked the idea of calling them helper pins. The therapist then gave Part III of Stepping Together to the parent, and they scheduled the remaining phone calls and midassessment. The therapist encouraged the child to continue to use his relaxation exercises, especially when he became scared or worried.

The parent and child completed the workbook by repeating the final Next Step, which consisted of looking again at the X-rays that showed the pins in his arms. They discussed relapse prevention such as what he can do when he gets reminded of what happened now and in the future. During these meetings they reviewed the entire My Steps book, which included reviewing all of the tools he learned as well as his story about what happened and what he did for each item on the scary ladder.

Midassessment

The child had five symptoms of PTSD and three areas of impairment on the DIPA, which was a 67% decrease in number of symptoms and 40% decrease in areas of impairment from baseline to midassessment. The TSCYC-PTS score was 37. The independent evaluators rated impairment as a 3, indicating “moderate impairment” on the CGI-Severity and the CGI-Improvement as “much improved.” The parent was asked if she thought her child needed more trauma-focused treatment or if she felt that she could comfortably stop at this time. The parent reported that with his improvements and tools that he learned, she felt comfortable stopping treatment. The parent and child then entered the maintenance phase where they continued to have parent-child meetings, and the child used his feelings score and relaxation. The parent reported spending about 30 minutes on the NCTSN website and about 10 minutes watching the stepped care demonstration videos.

Post and 3-Month Follow-up Assessment

The number of DIPA symptoms decreased from three at the postassessment to 0 at the 3-month follow-up assessment. Similarly, there were three areas of impairment endorsed at the postassessment whereas at the follow-up assessment there were no areas of impairment. The TSCYC–PTS score decreased from 39 at baseline to 32 at postassessment and 27 at follow-up assessment, resulting in a 31% decrease from baseline to follow-up assessment. The CGI-Severity rating was 2 (mild impairment) at postassessment and 0 (no impairment) at follow-up, and the CGI-Improvement remained at 2 (much improved) at the postassessment and decreased to 1 (very much improved) at the 3-month assessment.

Conclusion

This treatment development article describes the considerations that were taken into account when developing a stepped care model for young children exposed to trauma. These considerations included therapeutic approach, types of steps, number of steps, training of providers, entry point, and inclusion of parents. A specific stepped care model called Stepped Care TF-CBT, which includes Step One, Maintenance Phase, and Step Two, was described. In addition, issues such as noncompliance, determining responder status and monitoring treatment, flexibility, and implementation were discussed. A case example was described to illustrate Stepped Care TF-CBT.

Our preliminary case study (Salloum & Storch, 2011) and research from a small pilot study (Salloum et al., 2013) suggest that Stepped Care TF-CBT may be an acceptable service delivery approach to parents. For example, in a case study (e.g., Salloum & Storch) with a 5-year, 9-month-old Hispanic boy who had been physically abused and witnessed domestic violence, the child responded to treatment after Step One. After Step One his grandmother, who led the treatment, reported 32 (very satisfied) on the Client Satisfaction Questionnaire (CSQ; Nguyen, Attkisson, & Stegner, 1983), which is the highest score (range for this measure is 8 to 32). Similarly, in a small open trial with nine young children (ages 3 to 6) who participated in Stepped Care TF-CBT, five of the six children (83%) who completed Step One responded to treatment and one child responded after Step Two (two dropped out and one was withdrawn due to the parent being hospitalized). Satisfaction scores on the CSQ were 28 (SD = 7.45) at midassessment and 31.50 (SD = 1.0) at postassessment.

Currently, a randomized clinical trial comparing Stepped Care TF-CBT versus standard care TF-CBT is underway to determine to what extent there are comparable improvements in PTSD symptoms (primary outcome), internalizing and externalizing behaviors, impairment, and satisfaction levels, and to examine the percentage of children who respond to Step One. It will be important to examine if there are differential characteristics between those children who respond to Step One and those children who need to step up. Until more research on effective, less intensive first steps is conducted to differentiate predictors of responders and nonresponders, we cannot accurately match the individual to the best level of care needed (Haaga, 2000). Future studies can examine matched-care within a stepped care model. In addition, a preliminary comparison of costs associated with delivering Stepped Care TF-CBT and standard care TF-CBT needs to be conducted. As this research on stepped care for young children is underway, we are also modifying the model to be applicable to older children.

Stepped Care TF-CBT has the potential to be an evidence-based treatment that is more efficient, accessible, and cost-effective than standard TF-CBT. Studies have shown high rates of victimization among children and young children. Young children have the same rate or higher than other age groups for interpersonal violence such as witnessing domestic violence and neglect (Finkelhor, Ormrod, Turner, & Hamby, 2005). Trauma exposure can cause neurobiological, emotional, social, and cognitive impairment in young children that can derail development (Chu & Lieberman, 2010). Despite the high trauma exposure (Finkelhor et al., 2005; Finkelhor et al., 2009), accessible treatment by trained therapists to deliver EBP to children exposed to trauma remains limited (Allnock et al., 2012). Stepped Care TF-CBT may serve as a model for developing and testing stepped care approaches to treating other types of childhood psychiatric disorders. Without delivery methods that provide effective, accessible, and affordable treatment to children at an early age, young children with PTSD are at risk for a developmental trajectory of impairment and chronic distress that not only places an undue burden on the child, but imposes significant costs on society.

Highlights.

Stepped Care TF-CBT is designed to address treatment barriers.

Considerations for the development of Stepped Care TF-CBT are discussed.

Parent-led therapist-assisted treatment is used as a first-line treatment.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank David Tolin, Ph.D., Anxiety Disorders Center, The Institute of Living and Yale University School of Medicine, for his consultation on the development of the stepped care model for young children after trauma; and Crisis Center of Tampa Bay and Mary Lee's House in Tampa, Florida, where Stepped Care TF-CBT is being developed and tested. The project was supported by National Institute of Mental Health award R34MH092373 to Dr. Salloum. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute of Mental Health or the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Alison Salloum, University of South Florida, Tampa.

Michael S. Scheeringa, Tulane University

Judith A. Cohen, Center for Traumatic Stress in Children and Adolescents, Allegheny General Hospital

Eric A. Storch, University of South Florida, Tampa

References

- Allen B, Gharagozloo L, Johnson JC. Clinician knowledge and utilization of empirically-supported treatments for maltreated children. Child Maltreatment. 2012;17:11–21. doi: 10.1177/1077559511426333. doi:10.1177/1077559511426333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allnock D, Radford L, Bunting L, Price A, Morgan-Klein N, Ellis J, Stafford A. In demand: Therapeutic services for children and young people who have experienced sexual abuse. Child Abuse Review. 2012;21:318–334. doi:10.1002/car.1205. [Google Scholar]

- Amaya-Jackson L, DeRosa RR. Treatment considerations for therapists in applying evidence-based practice to complex presentations in child trauma. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2007;20:379–390. doi: 10.1002/jts.20266. doi:10.1002/jts.20266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Briere J. Trauma Symptom Checklist for Young Children: Professional Manual. Psychological Assessment Resources, Inc.; Lutz, FL: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Bringewatt EH, Gershoff ET. Falling through the cracks: Gaps and barriers in the mental health system for America's disadvantaged children. Children and Youth Services Review. 2010;32:1291–1299. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2010.04.021. doi:10.1016/j.childyouth.2010.04.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bower P, Gilbody S. Stepped Care in psychological therapies: Access, effectiveness and efficiency. British Journal of Psychiatry. 2005;185:11–17. doi: 10.1192/bjp.186.1.11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlbring P, Bohman S, Brunt S, Buhrman M, Westling BE, Ekselius L, Andersson G. Remote treatment of panic disorder: A randomized trial of internet-based cognitive behavior therapy supplemented with telephone calls. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2006;163:2119–2125. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2006.163.12.2119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlbring P, Gunnarsdóttir M, Hedensjö L, Anderson G, Ekselius L, Furmark T. Treatment of social phobia: Randomized trial of internet-delivered cognitive behavioural therapy with telephone support. British Journal of Psychiatry. 2007;190:123–128. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.105.020107. doi:10.1192/bjp.bp.105.020107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CATS Consortium Implementing CBT for traumatized children and adolescents after September 11: Lessons learned from the child and adolescent trauma treatments and services project. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2007;36:581–592. doi: 10.1080/15374410701662725. doi: 10.1080/15374410701662725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu AT, Lieberman AF. Clinical implications of traumatic stress from birth to age five. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. 2010;6:469–94. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.121208.131204. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.121208.131204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen JA, Bukstein O, Walter H, Benson R, Chrisman A, Farchione TR, Sotck S. Practice parameters for the assessment and treatment of PTSD in children and adolescents. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2010;49:414–430. doi:10.1097/MOP.0b013e32833e14a2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen JA, Deblinger E, Mannarino AP, Steer RA. A multi-site, randomized controlled trial for sexually abused children with PTSD symptoms. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2004;43:393–402. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200404000-00005. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000111364.94169.f9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen JA, Mannarino AP. Trauma-focused cognitive behavioural therapy for children and parents. Child and Adolescent Mental Health Volume. 2008;13:158–162. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-3588.2008.00502.x. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-3588.2008.00502.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen JA, Mannarino AP. Disseminating and implementing trauma-focused CBT in community settings. Trauma Violence Abuse. 2008;9:214–226. doi: 10.1177/1524838008324336. doi: 10.1177/1524838008324336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen JA, Mannarino AP, Deblinger E. Treating trauma and traumatic grief in children and adolescents. Guilford Press; New York, NY: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Deblinger E, Lippmann J, Steer R. Sexually abused children suffering posttraumatic stress symptoms: Initial treatment outcome findings. Child Maltreatment. 1996;1:310–321. [Google Scholar]

- Essau CA, Conradt J, Petermann F. Course and outcome of anxiety disorders in adolescents. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 2002;16:67–81. doi: 10.1016/s0887-6185(01)00091-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finkelhor D, Ormrod RK, Turner H. Lifetime assessment of poly-victimization in a national sample of children and youth. Child Abuse and Neglect. 2009;33:403–411. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2008.09.012. doi:10.1016/j.chiabu.2008.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finkelhor D, Ormrod R, Turner H, Hamby SL. The victimization of children and youth: A comprehensive, national survey. Child Maltreatment. 2005;10:5–25. doi: 10.1177/1077559504271287. doi: 10.1177/1077559504271287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleming J. The effectiveness of eye movement desensitization and reprocessing in the treatment of traumatized children and youth. Journal of EMDR Practice and Research. 2012;6:16–26. doi: 10.1891/1933-3196.6.1.16. [Google Scholar]

- Franx G, Oud M, Lange J, Wensing M, Gro R. Implementing a stepped-care approach in primary care: results of a qualitative study. Implementation Science. 2012;7:1–13. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-7-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guy W. ECDEU Assessment manual for psychopharmacology. U.S. Department of Health, Education, and Welfare; Washington, DC: 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Haaga DAF. Introduction to a special issue on stepped care models in psychotherapy. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2000;4:547–548. doi: 10.1037//0022-006X.68.4.547. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirai M, Clum GA. A meta-analytic study of self-help interventions for anxiety problems. Behavior Therapy. 2006;37(2):99–111. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2005.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaycox LJ, Cohen JA, Mannarino AP, Walker DW, Langley AK, Gegenheimer K, Schonlau M. Children's mental health care following Hurricane Katrina: A field trial of trauma-focused psychotherapies. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2010;23:223–231. doi: 10.1002/jts.20518. doi: 10.1002/jts.20518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Berglund PA, Bruce ML, Koch JR, Laska EM, Leaf PJ, Wang PS. The prevalence and correlates of untreated serious mental illness. Health Services Research. 2001;36:987–1007. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khanna MS, Kendall PC. Computer-assisted CBT for child anxiety: The coping cat CD-ROM. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice. 2008;15:159–165. [Google Scholar]

- King NJ, Tonge BJ, Mullen P, Myerson N, Heyne D, Rollings S, Ollendick TH. Treating sexually abused children with posttraumatic stress symptoms: A randomized clinical trial. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2000;39:1347–1355. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200011000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Layne CM, Saltzman WR, Poppleton L, Burlingame GM, Pasalic A, Durakovic E, Pynoos RS. Effectiveness of a school-based group psychotherapy program for war-exposed adolescents: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of the American Academy for Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2009;47:1048–1062. doi: 10.1097/CHI.0b013e31817eecae. doi: 10.1097/CH1.6b0136e1817eecae. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leong J, Cobham VE, de Groot J, McDermott B. Comparing different modes of delivery: A pilot evaluation of a family-focused, cognitive-behavioral intervention for anxiety-disordered children. European Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2009;18:231–239. doi: 10.1007/s00787-008-0723-7. doi:10.1007/s00787-008-0723-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyneham HJ, Rapee RM. Evaluation of therapist-supported parent-implemented CBT for anxiety disorders in rural children. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2006;44:1287–1300. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2005.09.009. doi:10.1016/j.brat.2005.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NCTSN National Child Traumatic Stress Network Empirically Supported Treatments and Promising Practices: Core components of intervention. 2012 Retrieved from http://www.nctsnet.org/resources/topics/treatments-that-work/promising-practices.

- National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health . Common mental health disorders: Identification and pathways to care. National Institute for Clinical Excellence; London: 2011. Retrieved from http://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/CG123. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen TD, Attkisson CC, Stegner BL. Assessment of patient satisfaction: Development and refinement of a service evaluation questionnaire. Evaluation and Program Planning. 1983;6:299–313. doi: 10.1016/0149-7189(83)90010-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pavuluri MN, Luk S, McGee R. Help-seeking for behavior problems by parents of preschool children: A community study. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1996;35:215–222. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199602000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Research Unit on Pediatric Psychopharmacology Anxiety Study Group (RUPP) Fluvoxamine for the treatment of anxiety disorders in children and adolescents. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2001;344(17):1279–1285. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200104263441703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salloum A. Minimal therapist assisted cognitive behavioral therapy interventions in stepped care for childhood anxiety. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice. 2010;41:41–47. doi:10.1037/a0018330. [Google Scholar]

- Salloum A, Robst J, Scheeringa MS, Cohen JA, Wang W, Murphy T, Storch EA. Step One within stepped care trauma-focused cognitive behavioral therapy for young children: A pilot study. Child Psychiatry and Human Developmen. 2013:1–13. doi: 10.1007/s10578-013-0378-6. doi: 10.1007/s10578-013-0378-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salloum A, Storch EA. Parent-led, therapist assisted, first line treatment for young children after trauma: A case study. Child Maltreatment. 2011;16(3):227–232. doi: 10.1177/1077559511415099. doi: 10.1177/1077559511415099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheeringa MS. Diagnostic infant and preschool assessment (DIPA) manual. Department of Department of Psychiatry and Neurology, Tulane University; New Orleans, LA.: 2008. Unpublished manuscript. [Google Scholar]

- Scheeringa MS, Amaya-Jackson L, Cohen J. Preschool PTSD treatment. Unpublished treatment manual. Tulane University; New Orleans, LA.: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Scheeringa MS, Salloum A, Arnberger R, Weems C, Amaya-Jackson L, Cohen J. Feasibility and effectiveness of cognitive-behavioral therapy for posttraumatic stress disorder in preschool children: Two case reports. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2007;20(4):637–642. doi: 10.1002/jts.20232. doi:10.1002/jts.20232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheeringa MS, Weems CF, Cohen JA, Amaya-Jackson L, Guthrie D. Trauma-focused cognitive-behavioral therapy for posttraumatic stress disorder in three through six year-old children: A randomized clinical trial. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2011;52:853–860. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2010.02354.x. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7610.2010.02354.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheeringa MS, Zeanah CH. Reconsideration of harm's way: Onsets and comorbidity patterns of disorders in preschool children and their caregivers following Hurricane Katrina. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2008;37:508–518. doi: 10.1080/15374410802148178. doi: 10.1080/15374410802148178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Self-Brown S, Whitaker D, Berliner L, Kolko D. Disseminating child maltreatment interventions: Research on implementing evidence-based programs. Child Maltreatment. 2012;17:5–10. doi: 10.1177/1077559511436211. doi:10.1177/1077559511436211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silverman WK, Ortiz CD, Viswesvaran C, Burns BJ, Kolko DJ, Putnam FW, Amaya-Jackson L. Evidence-based psychosocial treatments for children and adolescents exposed to traumatic events. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2008;37:156–183. doi: 10.1080/15374410701818293. doi: 10.1080/15374410701818293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Southam-Gerow MA, Weisz JR, Kendall PC. Youth with anxiety disorders in research and service clinics: Examining client differences and similarities. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology. 2003;32:375–385. doi: 10.1207/S15374424JCCP3203_06. doi: 0.1207/S15374424JCCP3203_06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spence SH, Holmes J, March S, Lipp O. The feasibility and outcome of clinic plus internet delivery of cognitive-behavioural therapy for childhood anxiety. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2006;74:614–621. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.74.3.614. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.74.3.614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevens J, Wang W, Fan L, Edwards MC, Campo JV, Gardner W. Parental attitudes toward children's use of antidepressants and psychotherapy. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychopharmacology. 2009;19:289–296. doi: 10.1089/cap.2008.0129. doi: 10.1007/s10597-006-9048-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thienemann M, Moore P, Tompkins K. A parent-only group intervention for children with anxiety disorders: pilot study. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2006;45:37–46. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000186404.90217.02. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000186404.90217.02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thurston IB, Phares V. Mental Health Service Utilization Among African American and Caucasian Mothers and Fathers. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2008;76:1058–1067. doi: 10.1037/a0014007. doi: 0.1037/a0014007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tolin DT, Diefenbach GJ, Gilliam CM. Stepped care versus standard cognitive-behavioral therapy for obsessive-compulsive disorder: A preliminary study of efficacy and costs. Depression and Anxiety. 2011;28:314–323. doi: 10.1002/da.20804. doi: 10.1002/da.20804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Department of Commerce US. Exploring the digital nation: Computer and internet usage at home. 2011 Retrieved from http://www.ntia.doc.gov/report/2011/exploring-digital-nation-computer-and-internet-use-home.

- van der Leeden AJM, van Widenfelt BM, van der Leeden R, Liber JM, Utens EMWJ, Treffers PDA. Stepped care cognitive behavioural therapy for children with anxiety disorders: A new treatment approach. Behavioral and Cognitive Psychotherapy. 2011;39:55–75. doi: 10.1017/S1352465810000500. doi:10.1017/S1352465810000500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]