Abstract

To evaluate the treatment outcome of antiretroviral therapy, depending on the use and utility of a concept of resistance-guided switch, patients from the Frankfurt HIV cohort have been followed for 24 weeks. If available, prior resistance data have been evaluated and patients were grouped into their expected viral response. The data of 354 patients were thus analyzed, taking into account the Genotypic Sensitivity Score of the administered medication (> or ≤ 2). When looking at the proportion of patients who achieved a viral load of less than 50/ml, the response rates differed significantly better for patients with a favourable resistance scoring as compared to an unfavourable one (71.9 % as compared to 56.0%, p = 0.008). Interestingly, patients with a favourable resistance score also showed a better immunological response, as measured by median CD4 cell count of 391/μl (Interquartal Range: 250 – 530/μl) against 287/μl (Interquartal Range: 174 – 449/μl) and a larger total increase of 141/μl against 38/μl. A significant virological and immunological benefit could be demonstrated for patients of a cohort with resistance-guided antiretroviral therapy adjustments.

Keywords: genotypic resistance test, immunological response, virological response, low level replication

Introduction

Combination antiretroviral therapy (cART) is the standard of care for HIV-infected patients today, as it significantly reduces morbidity and mortality [1], but HIV-1 resistance may challenge the therapeutic benefit for affected patients significantly. Thus, in case of virological failure, antiretroviral therapy switch should be guided by antiretroviral drug resistance analysis results.

The introduction of new agents and even drug-classes (e.g. integrase inhibitors, co-receptor-antagonists) were major achievements for salvage therapies. Second-generation non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NNRTI) and more potent protease inhibitors (PI), as well as entry-and integrase-inhibitors, all available just around 2008 could successfully be used [2, 3]. Even newer antiretroviral drug classes could overcome existing antiretroviral drug class resistance, as demonstrated by the MOTIVATE-studies for Maraviroc in use for salvage therapy patients [4, 5]. However even compounds from new antiretroviral drug classes could be affected by unknown, archived pre-existing backbone resistance, in particular for compounds characterized by a low barrier for resistance, such as raltegravir, e.g. demonstrated in the SWITCHMRK-studies [6].

The consequences of recent developments was to attempt complete suppression of HIV-1 replication (<50 copies/ml) for all patients again, even for the extensively treatment experienced. From a clinical perspective however, the limit of 200 copies/ml might be acceptable, especially for patients treated with protease inhibitor containing regimens.

Virological and immunological response data on Frankfurt HIV Cohort patients, could allow evaluation of the treatment outcome, depending on the use and utility of a concept of resistance-guided switch for antiretroviral therapy in extensively treatment experienced patients as described elsewhere [7]. The additional purpose of this study was to explore the effect of different levels of viral replication on immunological outcome and CD4 cell evolution, respectively, and to determine risk factors for clinical non-response after antiretroviral therapy switch.

Patients and Methods

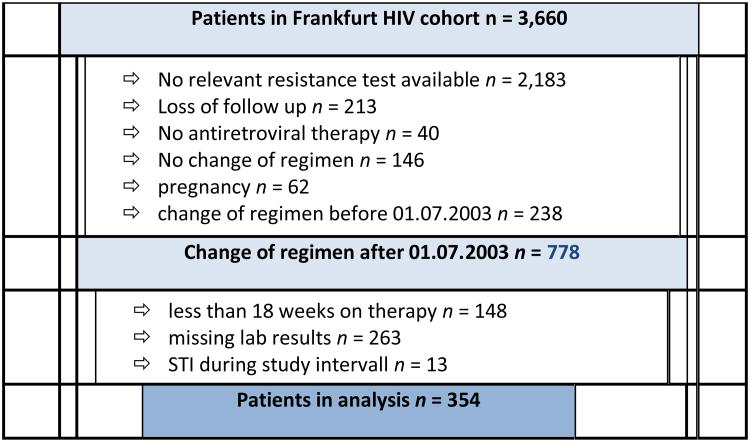

The Frankfurt HIV cohort includes 3,660 patients who have been followed since 1987. For this analysis, patients were included who had a change or an initiation of their therapeutic regimen after July 1st, 2003, and who had an available resistance test as well as available baseline-, week 4, 12 and 24 viral load and CD4 cell count results (n =778). Of these patients, those were chosen who were at least 18 weeks on therapy, had available laboratory results and had not had a treatment interruption (n=354). The details of patient selection are displayed in figure 1.

Figure 1.

Details of Patient selection, finally resulting in 354 eligible patients with evaluable data.

The study was approved by local ethics committee and the data protection officer from the federal state of Hessen. Patients had given their written, informed consent prior to inclusion (Vote-No. 270109/Frankfurt University Hospital Ethics Committee). All patients are treated in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and National and Institutional Standards.

Quantitative viral load was measured by HIV-1 ribonucleic acid (RNA)-polymerase chain reaction (PCR), consistently using the COBAS AMPLICOR HIV-1 MONITOR Test v1.5 (Roche Diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany). Genotypic resistance analysis was done using the ViroSeq™ HIV-1 Genotypic System version 2 (Abbott, Wiesbaden, Germany) for patients with a detectable viral load at more than 500 copies/mL, as described elsewhere [8].

According to prior resistance test result, all patients were assigned to groups of expected complete-(eCR), or impaired/partial response expectation (ePR), taking into account the genotypic sensitivity score (GSS) for the administered medication (> or ≤2), according to HIV-GRADE assessment [9], with a minor, but practically useful modification, introducing a binary system for each chosen drug: “limited susceptibility”, “intermediate” or “resistance” assessment were counted by 0 score points, whereas “susceptible” virus was counted by 1 point. The total score point sum for the selected antiretroviral regimen combination determined for expected impaired response (ePR if >2 points), or expected complete response (eCR, if ≤2), respectively. Consequently, patients were evaluated for actual week 24 (W24)-virological response, namely achieving full suppression (complete responder/CR <50copies/mL). As statistical tests, we used for group comparisons of metric parameters, including immunological and virological results, the Wilcoxon-Mann-Whitney-U-test and Kruskal-Wallis-test with post-hoc-correction for significance according to Bonferroni-Holm; demographic characteristics were evaluated by chi2-, or Fisher's exact test. Baseline patient characteristics as risk factors for virological failure were evaluated by logistic regression analysis (Wald-test, factor decreasing model; p > 0,1). All statistical calculations were performed with IBM-SPSS 15.0 and BiAS 10.0 (Institute for Biostatistics and Mathematical Modelling, University of Frankfurt, Germany). A case-control study was performed to compare patients in both groups as well as virus-characteristics by uni- and multivariate statistics, including regression analysis, to identify reasons for non-response.

Results

Table 1 shows the baseline characteristics of all patients (n=354) in the analysis as well as for the eCR (n=263) und ePR (n=91) strata. The overall median age was at 44 years with 78.2 % of male patients in the cohort. The median CD4 cell count was 250/μl (range 1 - 1055), and 31.9 % of patients were in CDC stage C at baseline.

Table 1. Baseline Characteristics and Results for the Study Population (n=354 individuals).

| Baseline characteristics | all n = 354 | eCR n = 263 (74.3 %) | ePR n = 91 (25.7 %) | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median age in years. (range) | 44 (15 – 74) | 43 (23 -74) | 44 (15 – 74) | 0.639 |

| Male gender n (%) | 277 (78.2) | 208 (79.1) | 69 (75.8) | 0.515 |

| Median virus load log10/ml (range) | 4.58 (1.30 – 6.15) | 4.74 (1.3 – 6.95) | 3.43 (1.3 – 5.9) | < 0.001 |

| Median CD4-cell count/μl (range) | 250 (1 – 1,055) | 250 (1 – 1,055) | 249 (6 – 1,011) | 0.866 |

| CDC-stage C (AIDS-definition) n (%) | 113 (31.9) | 76 (28.9) | 37 (40.7) | < 0.038 |

| Heterosexual Infection Route n (%) | 50 (14.1) | 35 (13.3) | 15 (16.4) | 0.603 |

| i.v. drug use n (%) | 38 (10.7) | 30 (11.4) | 8 (8.8) | |

| MSM n (%) | 182 (51.4) | 134 (51.0) | 48 (52.4) | |

| HIV endemic country n (%) | 17 (4.8) | 15 (5.7) | 2 (2.2) | |

| Others/unknown n (%) | 67 (18.9) | 49 (18.6) | 18 (19.8) | |

| med. yrs. of previous cART (range) | 6.78 (0 – 21.02) | 5.71 (0 – 21.0) | 8.5 (0 - 16.65) | < 0.001 |

| med. yrs. after 1st pos. HIV test (range) | 9.22 (0.13 – 22.96) | 8.47 (0.13 – 22.96) | 11.56 (1.39 – 22.81) | 0.197 |

| med. n of prev. substances n (range) | 6 (0 – 17) | 5 (0 – 16) | 8 (0-17) | < 0.001 |

| med. n of prev. regimens n (range) | 3 (0 – 7) | 2 (0 – 27) | 5 (0-21) | < 0.001 |

| med. n of subst. in last regimen (range) | 3 (0 - 7) | 3 (0 - 7) | 3 (0 – 7) | n.s. |

| Naïve patients n (%) | 63 (17.8) | 62 (23.6) | 1 (1.1) | < 0.001 |

| Reason for therapeutic change | ||||

| Virological failure n (%) | 263 (74.3) | 182 (69.2) | 81 (89.0) | <0.001 |

| Toxicity/intolerance n (%) | 13 (3.7) | 9 (3.4) | 4 (4.4) | n.s. |

| Patient decision n (%) | 3 (0.8) | 2 (0.8) | 1 (1.1) | n.s. |

| Others | 12 (3.4) | 8 (3.0) | 4 (4.4) | n.s. |

eCR – expected complete response (to administered antiretroviral regimen); ePR – expected partial response; MSM – men having sex with men; i.v. – intravenous; HIV – Human Immunodeficiency Virus; med. – median; prev. – previous; cART – combination antiretroviral therapy

There were some significant differences between eCR and ePR patients at baseline. ePR patients had significantly lower baseline virus loads and were longer on ART. Also, they had gone through more regimens and antiretroviral drugs. For the eCR patients, the proportion of naïve patients was significantly higher and patients were less frequently in CDC stage C. The reason for therapeutic change was more often virological failure for ePR group. There was however no significant difference in the median CD4 cell count between the groups.

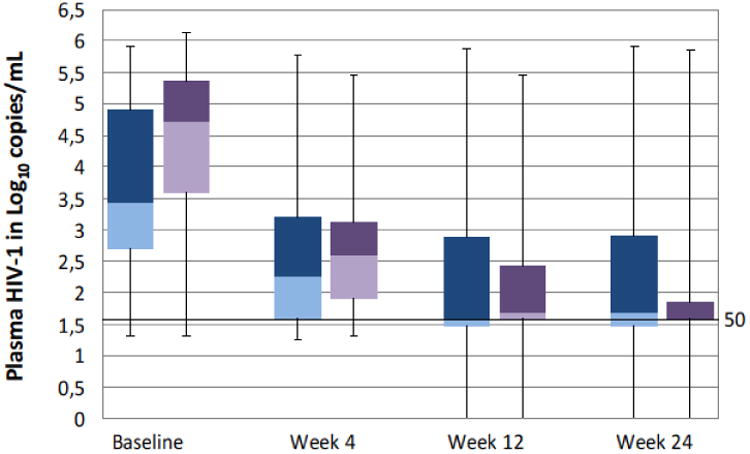

The virological response rates for all patients at week 24 was at 67.8% when taking a virus load lower than 50/ml as response criterion. Figure 2 shows the median virus loads, interquartal and total ranges at baseline, week 4, 12 and 24 for the ePR and eCR groups in comparison. It becomes evident that the median virus load is higher at baseline for eCR patients. Despite a higher baseline viral load, the success of HIV-1 suppression was better in eCR patients. When looking at the proportion of patients who achieved a viral load of less than 50/ml i.e. patients considered as actual complete responders (CR), the response rates differed significantly between patients with a previously “expected partial response” (ePR-patients: 51 of 91, or 56.0%) as compared to individuals with previously “expected complete resonse (eCR-patients: 189 of 263, or 71.9%, p = 0.008). At weeks 4 and 12, the median viral loads were even lower for ePR patients, which can however be explained by the lower baseline viral load.

Figure 2.

Medians, interquartal and total ranges for HIV-1 loads per response group.

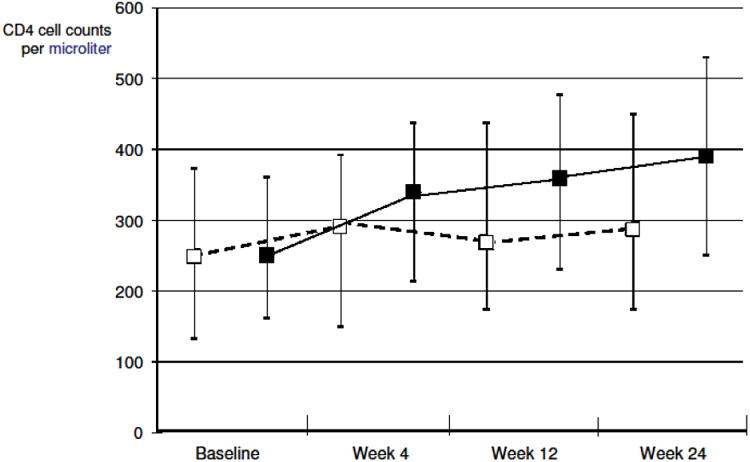

The results for the immunological response over time are displayed in figure 3. The median CD4 cell count at baseline was equal between the two groups. Not only did the patient with eCR achieve a better virological, but also a better immunological response when looking at the higher CD4 cell counts throughout weeks 4, 12 and 24. At week 24, patients with an eCR had a median CD4 cell count of 391/μl (IQR 250 – 530/μl) against 287/μl (IQR 174 – 449/μl) in the ePR group, which resulted in an increase (Δ) of +38/μl in the ePR and +141/μl in the eCR group.

Figure 3.

Medians and interquartal ranges for CD4 cell counts, as by previously expected response group (expected partial-, or expected complete response group, ePR/eCR).

A logistic regression analysis was performed in order to identify clinical risk factors for virological non-response. Factors that showed a significant association with virological non-response in the univariate regression analysis, were a longer median time on cART at baseline (p = 0.021), a higher prior number of combination regimen (p = 0.002), a higher drug exposure of individuals (p = 0.001), and finally a history of a clinical B or C CDC defining event at baseline (p = 0.009). In the multivariate model, a favourable resistance score, clinical CDC category B/C and previous virological failure remained the significantly associated factors for viral response (see table 2).

Table 2. Results of univariate (grey background) and multivariate analysis (white background) for risk of virological failure through week 24 after treatment intervention.

| Odds-Ratio | 95%-CI | Wald's p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Expected partial response (ePR) only | 2,003 | 1,22 – 3,29 | 0,006 |

| 1,657 | 0,99 – 2,76 | 0,053 | |

| CDC B/C | 2,195 | 1,37 – 3,51 | 0,001 |

| 1,87 | 1,15 – 3,03 | 0,011 | |

| previous virological failure | 3 | 1,63 – 5,52 | 0,001 |

| 2,442 | 1,30 – 4,58 | 0,005 |

Discussion

In this real-life cohort analysis, we examined the virological and immunological outcome of patients from a large treatment cohort who underwent resistance-guided HIV therapy modification after July 2003. This date was marked by the availability of enfuvirtide (T20) and was chosen to investigate its recent strategic value. For each individual's resistance test, a genotypic sensitivity score (GSS) was assessed and subjects were grouped into those with expected complete- and expected partial response (eCR, ePR), respectively. We were able to demonstrate that the resistance-guided switch in antiretroviral therapy was significantly associated not only with viral, but also with immunological response. In fact, the GSS result was one of the three factors remaining significantly associated with virological response, along with prior resistance and CDC stage – and this was not surprisingly for treating physicians (see table 1, reason for therapeutic change: virological failure).

The cost effectiveness of this time- and resource consuming standard of switching antiretroviral therapy in case of a virological failure, following resistance analysis, was questioned and recently challenged by the advent of new antiretroviral drugs and classes with limited cross-resistance to preexisting drugs. The proposed strategy in case of a virological failure, was to combine only new drugs and classes, taking into account possible pre-existing resistance by avoiding the clinically failing regimen components and their possible spectrum of drug cross-resistance. Our results however reconfirm for the present era the importance of the established standard of resistance-guided antiretroviral therapy modification and again underscores the importance for the outcome of the affected patients.

This study has the typical limitations of a retrospective design. As this was not a randomized trial, the ePR/eCR groups are not equally balanced, particularly with respect to the baseline virus load. However, the median baseline virus load was higher for eCR patients who responded more favourably and not vice versa.

Despite the limitations of this study, the results are in compliance with similar previous studies [7,10]. A study on 153 patients with virological failure showed a better outcome if the new drug regimen was selected based on sensitivity assessment [11]. Concerning therapy-naïve patients, there were large cohorts that have shown similar superiority of initial antiretroviral combinations with regard to transmitted drug resistance [12]. The prevalence of transmitted drug resistance was at 12% in the region in which our study was performed [13,14]. Interestingly, our data could moreover demonstrate that patients who were switched to an improved ART regimen with a favourable resistance score, had a better immunological outcome than those with an unfavourable one. This is of note, as there are large studies, that have found that the immunological outcome is similar as long as the degree of viral suppression is below 500 copies/ml [15,16] or 10,000 copies/ml [17] respectively. Although the degree of viral suppression was not correlated with the CD4 cell count response in these studies, the existence of primary antiretroviral resistance could be shown to be associated with a worse 6 month CD4 cell count increase in a large study of 504 participants [18]. Our findings do suggest that the application of drug resistance-guided therapies lead to a better suppression of HIV-1 replication and improved immunological recovery.

Taken together, the results from our study suggest that resistance guided selection of therapies do still confer an advantage nowadays, paying off in virological and immunological benefit for concerned patients, as this was demonstrated for the statistical group outcome parameters. These strategies should be applied individually wherever possible.

List of abbreviations, used within manuscript MMIM-D-14-00071 (R2)

- HIV

Human Immunodeficiency Virus

- IQR

Interquartal Range

- cART

combination antiretroviral therapy

- NRTI

nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor

- NNRTI

non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor

- PI

protease inhibitor

- CD (e.g. in CD4)

cluster of differentiation (for cell epitopes)

- RNA

ribonucleic acid

- DNA

desribonucleic acid

- PCR

polymerase chain reaction

- ml

milliliter

- μl

microliter

- GSS

Genotypic sensitivity score

- ePR

expected impaired/partial response

- eCR

expected complete response

- CDC

Centers for Diseases Control and Prevention (Atlanta GA, USA)

- MSM

men having sex with men

- i.v

intravenous (drug user)

Footnotes

Disclosures: All authors have declared no further conflict of interest, related to this article.

Contents of this work had been presented in part at the 14th Conference of the European AIDS Clinical Society (EACS), in Brussels (Belgium), October 16-19, 2013. Abstract P 9.4

Literature

- 1.Palella FJ, Jr, Delaney KM, Moorman AC, Loveless MO, Fuhrer J, Satten GA, Aschman DJ, Holmberg SD. Declining morbidity and mortality among patients with advanced human immunodeficiency virus infection. HIV outpatient study investigators. N Engl J Med. 1998;338:853–860. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199803263381301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yazdanpanah Y, Fagard C, Descamps D, Taburet AM, Colin C, Roquebert B, Katlama C, Pialoux G, Jacomet C, Piketty C, Bollens D, Molina JM, Chêne G ANRS 139 TRIO Trial Group. High rate of virologic suppression with raltegravir plus etravirine and darunavir/ritonavir among treatment-experienced patients infected with multidrug-resistant HIV: results of the ANRS 139 TRIO trial. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;49:1441–1449. doi: 10.1086/630210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Imaz A, del Saz SV, Ribas MA, Curran A, Caballero E, Falcó V, Crespo M, Ocaña I, Diaz M, de Gopegui ER, Riera M, Ribera E. Raltegravir, etravirine, and ritonavir-boosted darunavir: a safe and successful rescue regimen for multidrug-resistant HIV-1 infection. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2009;52:382–386. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181b17f53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gulick RM, Lalezari J, Goodrich J, Clumeck N, DeJesus E, Horban A, Nadler J, Clotet B, Karlsson A, Wohlfeiler M, Montana JB, McHale M, Sullivan J, Ridgway C, Felstead S, Dunne MW, van der Ryst E, Mayer H MOTIVATE study teams. Maraviroc for previously treated patients with R5 HIV-1 infection. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:1429–1441. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0803152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fätkenheuer G, Nelson M, Lazzarin A, Konourina I, Hoepelman AI, Lampiris H, Hirschel B, Tebas P, Raffi F, Trottier B, Bellos N, Saag M, Cooper DA, Westby M, Tawadros M, Sullivan JF, Ridgway C, Dunne MW, Felstead S, Mayer H, van der Ryst E MOTIVATE 1 and MOTIVATE 2 study teams. Subgroup analyses of maraviroc in previously treated R5 HIV-1 infection. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:1442–1455. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0803154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Eron JJ, Young B, Cooper DA, Youle M, DeJesus E, Andrade-Vilaanueva J, Workman C, Zajdenverg R, Fätkenheuer G, Berger DS, Kumar PN, Rodgers AJ, Shoughnessy MA, Qalker ML, Barnard RJ, Miller MD, Dinubile MG, Nguyen BY, Leavitt R, Xu X, Sklar P SCHWITCHMARK 1 and 2 investigators. Switch to a raltegravir-based regimen versus continuation of a lopinavir-ritonavir-based regimen in stable HIV-1 infected patients with suppressed viraemia (SWITCHMRK 1 and 2): two multicentre, double-blind, randomised controlled trials. Lancet. 2010;375:396–407. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)62041-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tural C, Ruiz L, Holtzer C, Schapiro J, Viciana P, González J, Domingo P, Boucher C, Rey-Joly C, Clotet B Havana Study Group. Clinical utility of HIV-1 genotyping and expert advice: the Havana trial. AIDS. 2002;16:209–218. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200201250-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stürmer M, Berger A, Doerr HW. Modifications and substitutions of the RNA extraction module in the ViroSeqTM HIV-1 Genotyping System Version 2: effects on sensitivity and complexity of the assay. J Med Virol. 2003;71:475–479. doi: 10.1002/jmv.10527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Obermeier M, Pironti A, Berg T, Braun P, Däumer M, Eberle J, Ehret R, Kaiser R, Kleinkauf N, Korn K, Kücherer C, Müller H, Noah C, Stürmer M, Thielen A, Wolf E, Walter H. HIV-GRADE: A Publicly Available, Rules-Based Drug Resistance Interpretation Algorithm Integrating Bioinformatic Knowledge. Intervirology. 2012;55:102–107. doi: 10.1159/000331999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stephan C, Bartha V, Herrmann E, von Hentig N, Khaykin P, Knecht G, Gute P, Brodt HR, Stürmer M, Berger A, Bickel M. Impact of HIV-1 replication on immunological evolution during long-term dual-boosted protease inhibitor therapy. Med Microbiol Immunol. 2013;202:117–124. doi: 10.1007/s00430-012-0276-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Baxter JD, Mayers DL, Wentworth DN, Neaton JD, Hoover ML, Winters MA, Mannheimer SB, Thompson MA, Abraham DI, Brizz BJ, Ioannidis JP, Merigan TC. A rondomized study of antiretroviral management based on plasma genotypic antiretroviral resistance testing in patients failing therapy. CPCRA 046m Study Team for the Terry Beirn Community Programs for Clinical Research on AIDS. AIDS. 2000;14:F83–93. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200006160-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wittkop L, Günthard HF, de Wolf F, Dunn D, Cozzi-Lepori A, De Luca A, Kücherer C, Obel N, von Wyl V, Masqulier B, Stephan C, Torti C, Antinori A, Garcia F, Judd A, Porter K, Thiebaut R, Castro H, van Sighem AL, Colin C, Kjaer J, Lundgren JD, Parede R, Pozniak A, Cotet B, Phillips A, Pillay D, Chêne G EuroCoord-CHAIN Study group. Effect of transmitted drug resistance on virological and immunological CR to intital combination antiretroviral therapy for HIV (EuroCoord-CHAIN project): a European multicohort study. Lancet Inf Dis. 2011;1:363–371. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(11)70032-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bartmeyer B, Kuecherer C, Houraeau C, Erning J, Keeren K, Somogyi S, Kollan C, Jessen H, Dupke S, Hamouda O German HIV-1 Seroconverter Study group. Prevalence of transmitted drug resistance and impact of transmitted resistance on treatment success in the German HIV-1 Seroconverter Cohort. PLoS One. 2010;5:e12718. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0012718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lawyer G, Schülter E, Kaiser R, Reuter S, Oette M, Lengauer T RESINA Study Group. Endogenous or exogenous spreading of HIV-1 in Nordrhein-Westfalen, Germany, investigated by phylodynamic analysis of the RESINA Study cohort. Med Microbiol Immunol. 2012;201:259–269. doi: 10.1007/s00430-011-0228-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Le Moing V, Thiebaut R, Chene G, Leport C, Cailleton V, Michelet C, Fleury H, Herson S, Raffi F Aproco Study Group. Predictors of long-term increase in CD4(+) cell counts in human immundodieficiency virus-infected patients receiving a protease inhibitor-containing antiretroviral regimen. J Infect Dis. 2002;185:471–480. doi: 10.1086/338929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Naeth G, Ehret R, Wiesmann F, Braun P, Knechten H, Berger A. Comparison of HIV-1 viral load assay performance in immunological stable patients with low or undetectable viremia. Med Microbiol Immunol. 2013;202:67–75. doi: 10.1007/s00430-012-0249-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ledergerber B, Lundgren JD, Walker AS, Sabin C, Justice A, Reiss P, Mussini C, Wit F, d'Arminio Monforte A, Weger R, Fusco G, Staszewski S, Law M, Hogg R, Lampe F, Gill MH, Castelli F, Phillips AN PLATO collaboration. Predictors of trend in CD4-positive T-cell count and mortality among HIV-1-infected individuals with virological failure to all three antiretroviral drug classes. Lancet. 2004;364:51–62. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16589-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Poggensee G, Kücherer C, Werning J, Somogoyi S, Bieniek B, Dupke S, Jessen H, Hamouda O HIV-1 Seroconverter study group. Impact of transmission of drug-resistant HIV on the course of infection and the treatment success. Data from the German HIV-1 Seroconverter Study. HIV Med. 2007;8:511–519. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1293.2007.00504.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]