Abstract

Objective

Cancer patients and their family caregivers often report elevated levels of depressive symptoms, along with poorer mental and physical health (quality of life: QOL). Although the mutuality in distress between patients and their caregivers is relatively well known, unknown are the degree to which caregivers’ depressive symptoms independently predict their patient’s QOL and vice versa, and whether the relations vary by cancer type or gender.

Methods

Colorectal or lung cancer patients and their caregivers (398 dyads) provided complete data for study variables (212 colorectal cancer patient dyads, 186 lung cancer patient dyads; 257 male patient dyads, 141 female patient dyads). Patients’ depressive symptoms and QOL were measured approximately 4 and 12 months post-diagnosis; caregivers’ depressive symptoms and QOL were measured approximately 5 months post-diagnosis.

Results

The Actor Partner Interdependence Model confirmed that each person’s depressive symptom level was uniquely associated with his/her own concurrent QOL. Female patients’ depressive symptoms were also related to their caregivers’ poorer physical and better mental health, particularly when the pair’s depressive symptoms were at similarly elevated level. On the other hand, male patients’ elevated depressive symptoms were related to their caregivers’ poorer mental health.

Conclusions

Findings suggest that QOL among patients and their family caregivers is interdependent. In light of this interdependency, psychosocial interventions for managing depressive symptoms should target both patients and their family caregivers, from which both may benefit by not only alleviating depressive symptoms but also improving quality of life.

Keywords: Depressive Symptoms, Quality of Life, Dyadic Adjustment, Gender, Cancer, Oncology

Cancer imposes challenges not only on the individual diagnosed with cancer, but also on his or her family members. Not surprisingly, both cancer patients and their family caregivers report elevated levels of dysphoric mood or depressive symptoms [1–3] and sometimes clinical levels of depression [4, 5] around the time of diagnosis and treatment. Individuals diagnosed with cancer often do not deal with their cancer alone but share their concerns with their families. Indeed, three reviews examining the relationship between the cancer patient’s psychological distress (anxiety and depression) and the caregiver’s distress suggest that they are related at a small to moderate degree [4, 6, 7]. The similarity in dysphoric mood between cancer patients and their family caregivers suggests dyadic mutuality, which is defined here as one person’s dysphoria tending to influence the other so that they come to resemble each other [7–9].

Psychological distress is known to be a significant negative factor in mental and physical health (i.e., quality of life: QOL) [10], not only of cancer patients [11] but also of family caregivers [9]. In a study of breast and prostate cancer patients and their spousal caregivers, for example, each one’s distress was a major predictor of his/her QOL. In addition, the extent to which the distress levels were similar between patients and their caregivers was independently associated with each person’s QOL [9]. These findings highlight the importance of dyadic mutuality in the relation between distress and QOL for both cancer patients and their family caregivers. What remains unclear, however, is the extent to which mutuality effects would be replicated with depressive symptoms as opposed to general distress or anxiety and whether the mutuality in depressive symptoms around the time of diagnosis predicts changes in patients’ quality of life by the end of the first year after the diagnosis (Exploratory Aim 1).

Another important finding of the Kim et al. [11] study was that wife caregivers’ elevated psychological distress was associated with poorer physical health of their husbands with prostate cancer (cross-over effect). A similar pattern, however, was not found among breast cancer patients and their husband caregivers. Since the two cancers studied were gender-specific, it was impossible to tell whether the cross-over effect was attributable to the patients’ gender or to their role as a patient or a caregiver. The study reported here addresses that question in a sample of patients with colorectal or lung cancer, two cancers that are non-gender-specific and have similar incidence rates between genders. Because no study to our knowledge has tested dyadic effects on QOL with non-gender-specific cancers, we simply explored comparability of associations between lung and colorectal cancers, instead of generating a specific hypothesis (Exploratory Aim 2).

Gender may also influence the association between depressive symptoms and QOL in interpersonal relationships in two ways [12]. First, women often play a significant role in the dyad’s socioemotional life [13, 14] and the woman’s mood often becomes a reference marker in interpersonal relationships [6, 7]. Thus, an emotionally less resourceful woman (due in part to her dysphoric mood) may impair her partner’s QOL, in addition to the dysphoric mood’s adverse impact on her own QOL. We hypothesized that the cross-over effect of depressive symptoms of women (either patients or caregivers) on their partner’s (either caregivers’ or patients’) QOL would be greater than the similar effect of depressive symptoms of males on their partners’ QOL (Hypothesis 1).

Second, as women are more likely than men to be sensitive to interpersonal issues, women may be more likely to perceive a lack of emotional mutuality or reciprocity as an indicator of their own deficiencies in interpersonal sensitivity [15, 16]. This could lead to feelings of isolation and social inadequacy, contributing to women’s poorer QOL [12, 17]. Thus, we hypothesized that greater dissimilarity in depressive symptoms between patients and caregivers [18, 19] would predict women’s poorer QOL within the dyads (Hypothesis 2).

Past research has also shown that a number of other factors beyond depressive mood have a significant impact on QOL within the cancer context. For example, age [20] and (co)morbidity [21, 22] for both patients and caregivers, and stage of cancer for patients [23] affect QOL. Therefore, in our analyses examining effects of depressive symptom (dis)similarity within dyads on QOL, these other factors are included as covariates.

Method

Participants and Procedure

The Cancer Care Outcomes Research and Surveillance (CanCORS) consortium was developed to assess the cancer care patterns and outcomes of patients diagnosed with colorectal or lung cancer [24]. Patients participating in CanCORS were identified by state cancer registries or health-care systems. Patients 21 years of age and older with newly diagnosed invasive non-small-cell or small-cell lung cancer or adenocarcinoma of the colon or rectum were eligible for study. Patient data were collected approximately 5 months (T1) and 12 months post-diagnosis (T2). Patients at T1 were asked to identify the person who was most likely to provide care for them when it was needed. Caregiver data was collected from the identified caregivers once. Both patients and caregivers received mailed packages including self-administered questionnaires specific to their role, information about the study, a postage-paid return envelope, and $20 incentive. Further information about the CanCORS study is provided in more detail elsewhere 25,26]. Data reported here are from the first cohort of the CanCORS.

Of 696 dyads of patients at T1 and their caregiver who participated in the present study, a total of 398 patient-caregiver dyads provided valid data for the study variables. Demographic and medical characteristics of participants are reported in Table 1. The time since cancer diagnosis was on average 153 days (5.1 months) for patients and 219 days (7.3 months) for caregivers (SD= 54 and 78 days, respectively) when the participants completed the initial survey.

Table 1.

Sample characteristics (N = 398 dyads)

| Patients | Caregivers | |

|---|---|---|

| Age: < 55 | 15.8% | 39.2% |

| 56 to 60 | 13.8% | 17.8% |

| 61 to 65 | 19.1% | 13.8% |

| 66 to 70 | 18.1% | 11.3% |

| 71 to 75 | 15.8% | 6.8% |

| 76 to 80 | 9.8% | 6.8% |

| > 81 | 7.5% | 4.3% |

| Gender (female) | 35.4% | 77.5% |

| Education: ≤ high school | 49.2% | 39.4% |

| college | 41.0% | 53.8% |

| > college | 9.8% | 7.1% |

| Ethnicity/Race: White | 78.6% | 76.9% |

| African American | 15.1% | 14.8% |

| Hispanic | 2.8% | 3.0% |

| Other | 3.5% | 5.3% |

| Marital Status: married | 68.3% | 79.9% |

| widowed | 12.1% | - |

| divorced | 14.1% | - |

| other | 5.5% | 20.1% |

| (Co)Morbidity | M (SD) = 1.99 (1.62) | 1.46 (1.07) |

| Relationship to the Patient: spouse | 63.8% | |

| offspring | 14.9% | |

| parent | 9.1% | |

| sibling | 5.3% | |

| other | 6.9% | |

| Cancer Site (Colorectal Cancer %) | 53.3% | |

| Stage: Stage 0 | 1.0% | |

| Stage I | 31.7% | |

| Stage II | 19.3% | |

| Stage III | 34.4% | |

| Stage IV | 13.6% | |

| # of Different Types of Treatment: 0 | 0.8% | |

| to Receive 1 | 38.4% | |

| 2 | 45.5% | |

| 3 | 15.3% |

Compared with patient-caregiver dyads who did not provide complete data for study variables, the patients in dyads who provided complete data were younger, female, had colorectal cancer rather than lung cancer, had less advanced stage of cancer, had better physical health at T1, and had more comorbidities at T2; the caregivers in dyads who provided complete data reported lower levels of depressive symptoms and fewer morbidities (ps < .05). Neither patients nor caregiver participants with complete data differed in other available study variables from those providing incomplete information (ps > .11).

Measures

Depressive Symptoms

Depressive symptoms of each participant were assessed using the 8-item CES-D for patients [26, 27] in yes or no response format and the 10-item CES-D for caregivers [28] in a 4-point response format ranging 0 to 3. Items were summed per participant and the sum scores were standardized within the patient group and (separately) the caregiver group to make the depressive symptom scores comparable between patients and caregivers. Higher scores on this composite reflected a greater level of depressive symptoms.

(Dis)Similarity in Depressive Symptoms

The extent to which a patient and his/her caregiver were similar in levels of depressive symptoms was calculated by subtracting the patient’s standardized depressive symptom score from his/her caregiver’s standardized depressive symptom score. To avoid multicollinearity, the difference score was then converted to an absolute value [18, 19]. Higher scores on the (dis)similarity in depressive symptom reflected greater discrepancy in the levels of depressive symptom within the dyad.

Cancer Type

Information about cancer type (colorectal or lung) was obtained from the state cancer registry.

Quality of Life (QOL)

Self-reported levels of QOL, namely, mental and physical health of participants were measured using the Medical Outcomes Study 12-Item Short Form Health Survey (MOS SF-12) [29]. The mental functioning score was a composite of weighted vitality, social functioning, role-emotional functioning, and mental health subscale scores. The physical functioning score was a composite of weighted physical functioning, role-physical, bodily pain, and general health subscale scores. Higher composite scores reflected better mental and physical health.

Covariates

Self-reported age and (co)morbidity of each person, and the patients’ stage of cancer (0 to IV) obtained from the cancer registry, were included in the analyses as covariates. The 15-item Adult Comorbidity Evaluation-27 [30, 31] that does not include mental morbid conditions was used for both patient and caregivers to assess the number of (co)morbidities.

Analytic Strategies

Mean differences between patients and caregivers on depressive symptoms and QOL (i.e., mental and physical health) were tested using paired t tests. The degree to which dyads were associated on these factors was tested using Pearson correlation coefficients.

The Actor Partner Interdependence Model (APIM) [19] served as the general data analytic strategy to address the central questions in this study: how depressive symptoms of both cancer patients and their caregivers relate to each person’s QOL (Exploratory Aim 1). This model terms the predictive effect of a person’s own characteristics (e.g., depressive symptoms) on that same person’s outcomes (e.g., quality of life) as an actor effect. A partner effect occurs when a person’s characteristics predict his or her partner’s outcomes. A relational effect indicates the extent to which the similarity (or dissimilarity) between patients and their caregivers in their depressive symptoms affect each person’s outcomes. The model parameters were estimated using structural equation modeling (SEM) with manifest variables (AMOS 21) [32]. The patient’s depressive symptom score, caregiver’s depressive symptom score, and absolute value of (dis)similarity in depressive symptom scores within the dyad were exogenous variables, and mental health and physical health (QOL) scores of patients at T1 and T2 and of caregivers at T1 were endogenous variables. Each person’s age and number of (co)morbidities, and the patient’s stage of cancer served as covariates.

Multiple-groups tests were conducted to determine the degree to which the model was comparable between colorectal and lung cancer patient dyads (Exploratory Aim 2) and between female and male patient dyads (Hypotheses 1 and 2). We found that the assumption of multivariate normality was violated in the data. Thus, we implemented the Bollen-Stine (BS) bootstrap method [33] for correcting chi-square values. Four model-fit indices are reported: the goodness of fit index (GFI), the confirmatory fit index (CFI), the root mean squared error of approximation (RMSEA), and standardized root mean square residual (SRMR). For the GFI, values of > .90 [34], for the CFI, values of > .95, and for the RMSEA and SRMR measures, values of < .06 [35] reflect adequate fit of a specified model to the data.

Results

Sample Characteristics

As shown in Table 1, the participants were predominantly middle-aged, Caucasian, relatively educated, and married. Patients were almost evenly divided between colorectal and lung cancers. Their cancer stage and number of different types of treatment to receive resemble incidence rate and medical practice for colorectal and lung cancer in the U.S. [36]. The majority of caregivers were the spouse of the patient.

Fewer female (35%) than male patients participated in the study. Slightly more than half of the female patients had male caregivers (N=76) and 65 female patients had female caregivers. Although these subsamples are less than the 100 that is typically recommended for APIM [19], we conducted paired sample comparisons and APIM analysis with the full female patients sample as well as two subsamples. In contrast, male patients (N=257) had predominantly female caregivers (N=242). Gender of two caregivers of male patients was missing and only 13 were male caregivers. Given this distribution, APIM analysis was conducted with male patients with any gender of caregivers and male patients with female caregivers. Paired sample comparisons, however, were conducted with full male patients and the two subsamples of male patients.

Comparing Patients and Caregivers in Depressive Symptoms and QOL

Comparisons between patients and caregivers for the entire sample (top block in Table 2) revealed significant differences in physical and mental health at T1. Patients reported worse physical health and better mental health than caregivers. Patients’ physical health at both T1 and T2 were below the 25th percentile of the U.S. population norm, whereas their mental health at both times were comparable to the U.S. population norm [29]. On the other hand, caregivers’ physical and mental health both were at approximately the 48th percentile of the U.S. population norm. Levels of mental health (r=.26) and depressive symptoms (r=.27) of patients and their caregivers at T1 were positively correlated.

Table 2.

Paired t-tests and Pearson correlation coefficients comparing patients and caregivers on depressive symptoms and QOL measures

| Patients | Caregivers | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| M (SD) | M (SD) | t | r | |

| Overall (N = 398 dyads) | ||||

| Depressive Symptoms at T1 | 0.05 (1.05) | −0.05 (0.95) | 1.63 | .27*** |

| QOL: Physical Health at T1 | 38.24 (10.81) | 47.88 (11.03) | −12.88*** | .07 |

| QOL: Mental Health at T1 | 51.21 (11.28) | 47.97 (10.67) | 4.86*** | .26*** |

| QOL: Physical Health at T2 | 39.38 (12.02) | - | - | - |

| QOL: Mental Health at T2 | 52.26 (10.29) | - | - | - |

| Colorectal Cancer Dyads (N = 212 dyads) | ||||

| Depressive Symptoms at T1 | 0.05 (1.08) | −0.04 (0.99) | 1.08 | .34*** |

| QOL: Physical Health at T1 | 40.68 (11.07) | 47.01 (11.13) | −6.35*** | .14* |

| QOL: Mental Health at T1 | 50.35 (11.12) | 48.50 (11.16) | 2.04* | .30***+ |

| QOL: Physical Health at T2 | 43.03 (11.43) | - | - | - |

| QOL: Mental Health at T2 | 51.72 (10.30) | - | - | - |

| Lung Cancer Dyads (N = 186 dyads) | ||||

| Depressive Symptoms at T1 | 0.06 (1.03) | −0.06 (0.90) | 1.24 | .17* |

| QOL: Physical Health at T1 | 35.42 (9.87) | 49.01 (10.74) | −12.79*** | .02 |

| QOL: Mental Health at T1 | 52.18 (11.44) | 47.31 (10.10) | 4.92*** | .23** |

| QOL: Physical Health at T2 | 35.14 (11.33) | - | - | - |

| QOL: Mental Health at T2 | 52.81 (10.58) | - | - | - |

| Female Patients with Any Gender of Caregivers (N = 141 dyads) | ||||

| Depressive Symptoms at T1 | 0.23 (1.11) | −0.10 (0.95) | 3.18** | .29*** |

| QOL: Physical Health at T1 | 38.30 (10.36) | 49.79 (10.07) | −9.97*** | .10 |

| QOL: Mental Health at T1 | 49.84 (11.60) | 48.06 (10.39) | 1.49 | .18* |

| QOL: Physical Health at T2 | 39.54 (11.69) | - | - | - |

| QOL: Mental Health at T2 | 51.50 (10.33) | - | - | - |

| Female Patients with Male Caregivers (N = 76 dyads) | ||||

| Depressive Symptoms at T1 | 0.13 (1.13) | −0.26 (0.96) | 2.72** | .29*** |

| QOL: Physical Health at T1 | 38.36 (10.96) | 48.77 (10.34) | −6.55*** | .16 |

| QOL: Mental Health at T1 | 52.01 (11.19) | 50.08 (9.54) | 1.25 | .15 |

| QOL: Physical Health at T2 | 40.63 (11.18) | - | - | - |

| QOL: Mental Health at T2 | 53.47 (9.53) | - | - | - |

| Female Patients with Female Caregivers (N = 65 dyads) | ||||

| Depressive Symptoms at T1 | 0.34 (1.08) | 0.08 (0.91) | 1.73† | .25* |

| QOL: Physical Health at T1 | 38.23 (9.70) | 50.99 (9.68) | −7.62*** | .03 |

| QOL: Mental Health at T1 | 47.29 (11.63) | 45.70 (10.92) | 0.86 | .13 |

| QOL: Physical Health at T2 | 38.27 (12.22) | - | - | - |

| QOL: Mental Health at T2 | 49.19 (10.81) | - | - | - |

| Male Patients with Any Gender of Caregivers (N = 257 dyads) | ||||

| Depressive Symptoms at T1 | −0.05 (1.01) | −0.02 (0.95) | −0.38 | .27*** |

| QOL: Physical Health at T1 | 38.20 (11.11) | 46.92 (11.34) | −9.00*** | .05 |

| QOL: Mental Health at T1 | 51.95 (11.07) | 47.89 (10.86) | 5.05*** | .31*** |

| QOL: Physical Health at T2 | 39.26 (12.02) | - | - | - |

| QOL: Mental Health at T2 | 52.63 (10.29) | - | - | - |

| Male Patients with Female Caregivers (N = 242 dyads) | ||||

| Depressive Symptoms at T1 | −0.06 (1.00) | 0.00 (0.94) | −0.81 | .26*** |

| QOL: Physical Health at T1 | 38.27 (11.28) | 46.94 (11.29) | −8.71*** | .06 |

| QOL: Mental Health at T1 | 52.13 (10.96) | 47.76 (10.85) | 5.29*** | .31*** |

| QOL: Physical Health at T2 | 39.23 (12.01) | - | - | - |

| QOL: Mental Health at T2 | 52.72 (10.22) | - | - | - |

| Male Patients with Male Caregivers (N = 13 dyads) | ||||

| Depressive Symptoms at T1 | 0.25 (1.18) | −0.33 (1.01) | 2.00† | .54† |

| QOL: Physical Health at T1 | 36.80 (7.58) | 46.45 (12.86) | −2.21* | −.12 |

| QOL: Mental Health at T1 | 48.68 (13.05) | 50.17 (11.36) | −0.43 | .47 |

| QOL: Physical Health at T2 | 39.73 (16.50) | - | - | - |

| QOL: Mental Health at T2 | 50.93 (11.76) | - | - | - |

p < .10

p < .05

p < .01

p < .001

Note. Depressive symptom scores were standardized within patients or caregivers sample; QOL = Quality of Life

These patterns remained the same across subsamples by two types of cancer or gender of patients and caregivers (second to ninth blocks in Table 2), with four exceptions. First, colorectal cancer patients’ physical health score at T1 was significantly positively correlated with their caregivers’ physical health score. Second, female patients reported the highest and their caregivers, particularly their male caregivers, reported the lowest levels of depressive symptoms. This yielded a significant difference in depressive symptoms between patients and caregivers. Third, female patients’ mental health scores were comparable with their caregivers’ mental health scores regardless of their caregivers’ gender. Subsamples of female patients had mental health scores positively correlated with their caregivers’ but not at a statistically significant level, probably due to small sample sizes. Fourth, male patients with male caregivers reported lower mental health compared with male patients with female caregivers, whereas male caregivers of male patients reported higher mental health compared with female caregivers of male patients.

Prediction of QOL from Depressive Symptoms: Overall Sample

The SEM model implied by the APIM is one in which each person’s outcomes (i.e., the patient’s and caregiver’s physical and mental health, QOL) are predicted to be functions of each person’s depressive symptoms (actor effects), of his or her partner’s depressive symptoms (partner effects), as well as, of the difference between the two partners’ depressive symptoms (relational effects). Table 3 presents the parameter estimates. The model fit for the overall sample data was acceptable: multivariate kurtosis=18.58, p < .001, χ2(53)=149.88, GFI=.952, CFI=.939, RMSEA=.068, and SRMR=.083.

Table 3.

Depressive symptoms predicting individual’s QOL in APIM: Dissimilarity Model

| Physical Health |

Mental Health |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient at T1 |

Patient at T2 |

Caregiver | Patient at T1 |

Patient at T2 |

Caregiver | |

| Overall (N = 398 dyads) | ||||||

| Predictors: | ||||||

| Patient’s Depression | −.26*** | −.01 | −.05 | −.73*** | −.22*** | −.03 |

| Caregiver’s Depression | - | −.04 | −.18*** | - | −.03 | −.78*** |

| Dissimilarity | - | −.04 | .05 | - | .03 | −.03 |

| Covariates: | ||||||

| Individual’s Age | - | −.02 | −.28*** | - | .05 | .12*** |

| Individual’s morbidity | - | −.19*** | −.29*** | - | −.19*** | .00 |

| Stage of Cancer | - | −.04 | .08† | - | .03 | −.03 |

| T1 Physical or Mental Health | - | .51*** | - | - | .30*** | - |

| Colorectal Cancer Dyads (N = 212 dyads) | ||||||

| Predictors: | ||||||

| Patient’s Depression | −.32*** | −.12† | .02 | −.76*** | −.20* | −.06 |

| Caregiver’s Depression | - | −.08 | −.20** | - | −.06 | −.83*** |

| Dissimilarity | - | −.02 | .03 | - | −.02 | .05 |

| Covariates: | ||||||

| Individual’s Age | - | −.06 | −.28*** | - | .02 | .08* |

| Individual’s morbidity | - | −.20*** | −.32*** | - | −.17** | .02 |

| Stage of Cancer | - | −.03 | .12* | - | .05 | −.04 |

| T1 Physical or Mental Health | - | .42*** | - | - | .32*** | - |

| Lung Cancer Dyads (N = 186 dyads) | ||||||

| Predictors: | ||||||

| Patient’s Depression | −.18** | .06 | −.15* | −.71*** | −.25** | .01 |

| Caregiver’s Depression | - | .01 | −.19** | - | −.02 | −.70*** |

| Dissimilarity | - | −.04 | .10 | - | .09 | −.15** |

| Covariates: | ||||||

| Individual’s Age | - | .09 | −.30*** | - | .07 | .21*** |

| Individual’s morbidity | - | −.25*** | −.22*** | - | −.21*** | −.07 |

| Stage of Cancer | - | −.03 | .00 | - | −.01 | .03 |

| T1 Physical or Mental Health | - | .48*** | - | - | .26** | - |

| Female Patients with Any Gender of Caregivers (N = 141 dyads) | ||||||

| Predictors: | ||||||

| Patient’s Depression | −.32*** | −.05 | −.21* | −.73*** | −.03 | .08 |

| Caregiver’s Depression | - | −.01 | −.20** | - | −.10 | −.77*** |

| Dissimilarity | - | −.13† | .17* | - | .02 | −.17** |

| Covariates: | ||||||

| Individual’s Age | - | −.07 | −.27*** | - | .11 | .16*** |

| Individual’s morbidity | - | −.06 | −.23** | - | −.28*** | .03 |

| Stage of Cancer | - | −.06 | .07 | - | −.04 | .01 |

| T1 Physical or Mental Health | - | .60*** | - | - | .38*** | - |

| Female Patients with Male Caregivers (N = 76 dyads) | ||||||

| Predictors: | ||||||

| Patient’s Depression | −.38*** | .00 | −.11* | −.74*** | .09 | .13 |

| Caregiver’s Depression | - | .03 | −.34*** | - | .04 | −.79*** |

| Dissimilarity | - | −.08 | .07 | - | .04 | −.19* |

| Covariates: | ||||||

| Individual’s Age | - | −.02 | −.18† | - | .17* | .14* |

| Individual’s morbidity | - | −.03 | −.25* | - | −.36*** | .03 |

| Stage of Cancer | - | .05 | .02 | - | .10 | .08 |

| T1 Physical or Mental Health | - | .70*** | - | - | .61*** | - |

| Female Patients with Female Caregivers (N = 65 dyads) | ||||||

| Predictors: | ||||||

| Patient’s Depression | −.29* | −.15** | −.22* | −.71*** | −.17 | .03 |

| Caregiver’s Depression | - | .09 | −.09 | - | −.09 | −.74*** |

| Dissimilarity | - | −.24** | .28** | - | .03 | −.21** |

| Covariates: | ||||||

| Individual’s Age | - | −.05 | −.36*** | - | .13 | .13† |

| Individual’s morbidity | - | .01 | −.20† | - | −.21* | .06 |

| Stage of Cancer | - | −.14† | .12 | - | −.18† | −.04 |

| T1 Physical or Mental Health | - | .53*** | - | - | .18 | - |

| Male Patients with Any Gender of Caregivers (N = 257 dyads) | ||||||

| Predictors: | ||||||

| Patient’s Depression | −.22*** | .03 | −.02 | −.73*** | −.34*** | −.08* |

| Caregiver’s Depression | - | −.06 | −.15** | - | .01 | −.80*** |

| Dissimilarity | - | .03 | .00 | - | .01 | .04 |

| Covariates: | ||||||

| Individual’s Age | - | .01 | −.29*** | - | .01 | .11** |

| Individual’s morbidity | - | −.29*** | −.30*** | - | −.12* | −.02 |

| Stage of Cancer | - | −.01 | .08 | - | .06 | −.05 |

| T1 Physical or Mental Health | - | .45*** | - | - | .24** | - |

| Male Patients with Female Caregivers (N = 242 dyads) | ||||||

| Predictors: | ||||||

| Patient’s Depression | −.20*** | .01 | −.03 | −.73*** | −.38*** | −.07† |

| Caregiver’s Depression | - | −.05 | −.15** | - | .02 | −.80*** |

| Dissimilarity | - | .02 | .02 | - | .03 | .05* |

| Covariates: | ||||||

| Individual’s Age | - | −.02 | −.30*** | - | .05 | .12** |

| Individual’s morbidity | - | −.30*** | −.27*** | - | −.11* | −.03 |

| Stage of Cancer | - | −.04 | .08 | - | .06 | −.05 |

| T1 Physical or Mental Health | - | .47*** | - | - | .26*** | - |

p < .10

p < .05

p < .01

p < .001

Note. β = standardized coefficient; coefficients left side of “/” are for testing difference model; coefficients right side of “/” are for testing interaction model; shared p-value markers indicate the p-values in the difference model and the interaction model were at the same significance level; Depression or Dep = depressive symptoms; Dissimilarity in Depressive Symptom = absolute difference between patient’s depressive symptom and caregiver’s depressive symptom score within the dyad for testing the difference model; Product of Depressive Symptom = product of patient’s depressive symptom score with caregiver’s depressive symptom score within the dyad for testing the interaction model; Stage of Cancer: Stage 0 to IV.

As shown in the top block of Table 3 testing Exploratory Aim 1, patients’ depressive symptoms at T1 were associated with their poor physical and mental health at T1 and poor mental health at T2 (actor effects). Caregivers’ depressive symptoms were also related to their poorer physical and mental health (actor effects). Caregivers’ age was related to their own poorer physical health and better mental health, whereas patients’ age was not related to their QOL (actor effects). (Co)Morbidity was associated with poorer physical health for both patients and caregivers, and with poorer mental health only for patients (actor effects). Patients’ physical and mental health at T1 were positively related to those at T2. Beyond these individual effects, at the dyadic level, more advanced stage of cancer was marginally related to better physical health of caregivers. No partner or relational (dissimilarity) effects were significant.

Prediction of QOL from Depressive Symptoms: Comparisons by Cancer Types

Testing Exploratory Aim 2, a multiple-groups test was conducted to determine the degree to which the study model was an adequate representation for both colorectal (212 dyads) and lung cancer patients (186 dyads). The fit of the model constrained to be equal between the two cancers was marginally acceptable: χ2(145)=267.27, GFI=.917, CFI=.923, RMSEA=.046, and SRMR=.100, and was significantly worse than that of the unconstrained model: χ2diff=117.4 with degree of freedom=92, p < .04. This indicated that the relations among variables were not comparable for the two types of cancer, so the two cancers were examined separately.

Among colorectal cancer patients and their caregiver dyads (second block of Table 3), two patterns emerged that differed from the model with the overall sample. Colorectal cancer patients’ depressive symptoms at T1 became marginally significantly related to their own poorer physical health at T2. Having more advanced colorectal cancer became significantly associated with caregivers’ better physical health. Among lung cancer patients and their caregiver dyads (third block of Table 3), two different patterns emerged as well. Lung cancer patients’ depressive symptoms became significantly associated with their caregivers’ poorer physical health. In addition, when lung cancer patients and their caregivers had similar depressive symptom scores, the caregivers were more likely to report better mental health.

Prediction of QOL from Depressive Symptoms: Comparisons by Patients’ Gender

For testing Hypotheses 1 and 2, the study model was also compared by the two genders of patients: female patients (N=141 dyads) and male patients (N=257 dyads). The fit of the model constrained to be equal between the two genders was marginally acceptable: χ2(145)=289.25, GFI=.910, CFI=.912, RMSEA=.050, and SRMR=.110, and was significantly worse than that of the unconstrained model: χ2diff=139.37 with degree of freedom=92, p < .001. Thus, the two genders of patients were examined separately.

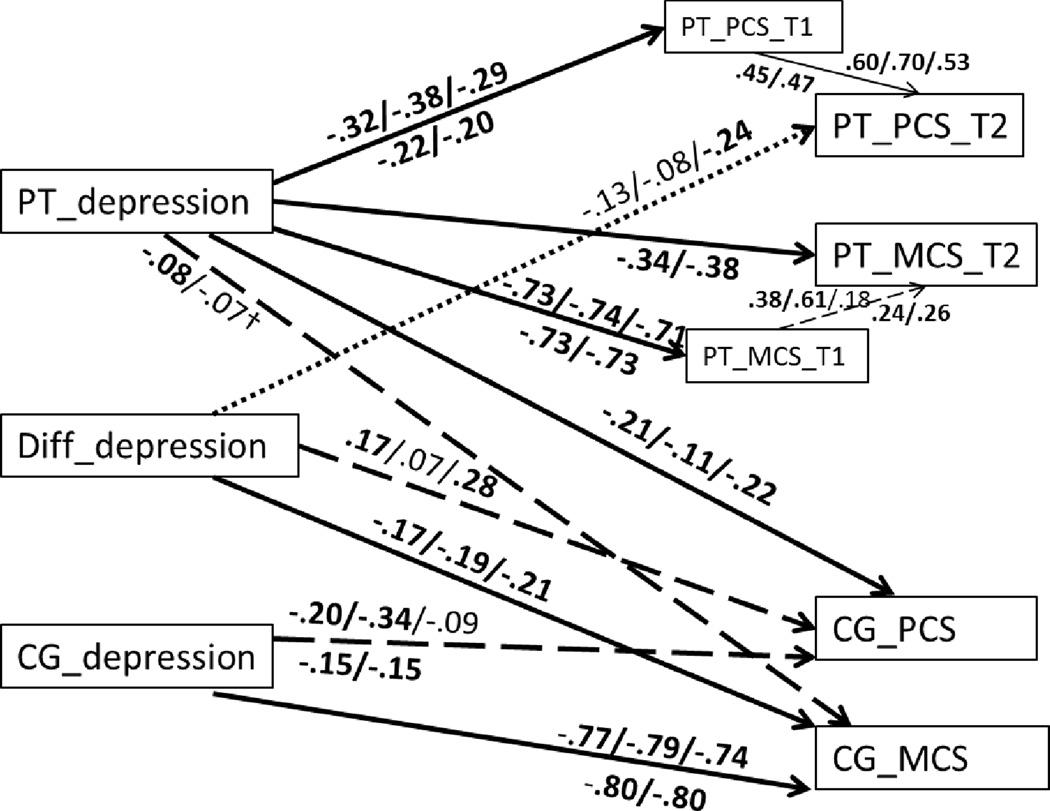

Among female patients with any gender of caregivers (fourth block in Table 3; first coefficients above path lines in Figure 1), the actor effects remained significant for both physical and mental health at T1 for both patients and caregivers. Such actor effects were not significant for patients’ physical and mental health at T2. Age actor effects and (co)morbidity actor effects remained significant, except that patients’ comorbidity on physical health at T2 became non-significant. Patients’ physical and mental health at T1 remained strongly related to those at T2, respectively. In addition, one partner effect in this model became significant: female patients’ greater depressive symptoms related to poorer physical health of their caregivers. Other partner effects were not significant.

Figure 1. Individual and Differences Scores of Depression Predicting Quality of Life.

Note. Coefficients are standardized coefficients, separated by “/” for different sub-samples tested by patients’ gender; coefficients above a path are for sub-samples of female patients [Female Patients with Any Gender Caregivers (N = 141) / Female Patients with Male Caregivers (N = 76) / and Female Patients with Female Caregivers (N = 65)]; coefficients below a path are for subsamples of male patients [Male Patients with Any Gender Caregivers (N = 257) / Male Patients with Female Caregivers (N = 242)]; Coefficients in bold are significant at p < .05; Solid path lines are for significant at p < .05 for all sub-samples tested within the same gender of patients; Broken lines are for significant at p < .05 for two subsamples for female patient dyads and one subsample for male patient dyads; Dotted lines are significant at p < .05 for one subsample for female patient dyads; PT = patients; CG = caregivers; PCS = physical health score; MCS = mental health score; Individuals’ age and (co)morbidity, and cancer stage were included in the analysis but omitted in figures for presentational simplicity.

Beyond these individual-level effects, at the dyadic level a greater dissimilarity in depressive symptoms became significantly associated with better physical health and worse mental health of caregivers. In addition, a greater dissimilarity was marginally related to poorer physical health of female patients at T2. In other words, over and above the effects of each person’s depressive symptoms, when there was a greater difference in depressive symptoms within the dyad, female patients tended to report poorer physical health, whereas their caregivers reported better physical health and poorer mental health. Stage of cancer was not related to the physical and mental health of either patients or caregivers.

Among male patients and their caregivers of any gender (seventh block in Table 3; first coefficients below path lines in Figure 1), the actor effects on physical and mental health at T1 for both patients and caregivers remained. An additional actor effect on patients’ mental health at T2 became significant. Age and (co)morbidity actor effects remained, except that caregivers’ age became no longer related to their mental health. Patients’ physical and mental health at T1 remained strongly related to those at T2, respectively. In addition, one partner effect became significant, this time on caregivers’ mental health: Male patients’ greater levels of depressive symptoms related to poorer mental health of their caregivers. Other partner effects were not significant.

Dissimilarity in depressive symptoms among male patient dyads was not related to anyone’s physical and mental health. Effects of cancer stage were again not significant.

Predicting QOL from Depressive Symptoms: Comparisons with Cross-Gender Dyads

When the gender of caregivers was considered as well, the model fit for cross-gender dyads (N=318) was acceptable: multivariate kurtosis=20.19, p < .001, χ2(53)=120.18, GFI=.952, CFI=.951, RMSEA=.063, and SRMR=.088. When the model was constrained by two cross-gender dyads (female patients with male caregivers vs male patients with female caregivers), it was significantly worse than that of the unconstrained model: χ2diff=127.29 with degree of freedom=92, p < .001, indicating the relations among variables were not comparable between female patients with male caregivers and male patients with female caregivers.

In the subsample of female patients with male caregivers (fifth block in Table 3; second coefficients above path lines in Figure 1), actor effects at T1, dissimilarity in depression on caregivers’ mental health, patients' depression relating to caregivers’ poorer physical health, and patients’ physical and mental health at T1 relating to those at T2 remained significant, but the path of dissimilarity relating to caregivers’ physical health became non-significant.

In the subsample of male patients with female caregivers (eighth block in Table 3; second coefficients below path lines in Figure 1), all the significant paths remained significant, with one exception of the path of patients’ depressive symptoms to caregivers’ mental health became marginally significant. As male patient with male caregiver dyads were 5% of the entire male patients, the patterns of study variables seen in male patient dyads are mainly driven by male patient with female caregiver dyads.

Predicting QOL from Depressive Symptoms: Female Same-Gender Dyads

In the subsample of female patients with female caregivers (sixth block in Table 3; third coefficients above path lines in Figure 1), all the significant paths in the full female patient model remained significant with two exceptions: patients’ mental health at T1 no longer related to that at T2; and caregivers’ depression no longer related to their own physical health. In addition, one path became significant: greater similarity in levels of depressive symptoms within the dyad became associated with patients’ poorer physical health at T2.

Summary of Findings of Model Testing

Findings illustrate that dyadic mutuality effects on QOL can be expanded to depressive symptoms among cancer patients and their caregivers when their genders were taken into consideration, accomplishing Exploratory Aim 1. Testing Exploratory Aim 2 comparing the two cancers, depressive symptoms had long term impact on colorectal cancer patients’ QOL (actor effect), whereas lung cancer patients’ elevated depressive symptoms related to their caregivers’ poorer physical health and similarity in depressive symptoms within the lung cancer dyad related to the caregivers’ better mental health (partner effects).

Testing Hypotheses 1 and 2, the concurrent actor effects on patients’ physical and mental health, and on caregivers’ mental health were found in all subsamples studied. Actor effects on caregivers’ physical health were significant for all male patient dyads but only for those female patients with male caregivers. Actor effects on patients’ mental health at T2 were only significant for male patient dyads. Partner effects on caregivers’ physical health were significant only for all female patient dyads, providing partial support of Hypothesis 1, that women’s depressive symptoms influence their partner’s physical health more than men’s do. On the other hand, partner effects on caregivers’ mental health were (marginally) significant for all male patient dyads only, supporting Hypothesis 2 that women’s mental health is affected by their male partner’s depressive mood.

Among female patient dyads, dissimilarity of depressive symptoms within the dyad was associated with caregivers’ better physical (only among female caregivers) and poorer mental health. The results suggest female caregivers of female patients were better off physically and worse off mentally when their levels of depressive symptoms were not similar to those of their patients, whereas male caregivers of female patient would be worse off mentally when their depressive mood was not at a similar level with their patient.

Discussion

This study examined the effects of depressive symptoms on quality of life, operationalized as mental and physical health, in family members dealing with cancer. Four findings particularly deserve discussion. First, caregivers reported comparable levels of depressive symptoms but poorer mental health than patients. The findings extend our current knowledge about the psychological impact that cancer can bring on, not only to patients but also to their family caregivers in lung and colorectal cancer cases. The findings also lend support to concerns that caregivers are hidden sufferers [40], as the psychological toll of cancer in the family might be greater for caregivers than patients.

Second, the individual’s own depressive symptoms (actor effects), those of his or her partner (partner effects), and the similarity of those (relational effects) were all significant predictors of individual’s QOL, consistent with existing literature [e.g., 9,38]. Findings also extend knowledge by replicating the individual and dyadic effects with depressive symptoms and demonstrating differential patterns of such effects by two cancer types. Earlier depressive symptoms in the course of treatment had lasting impact on patients’ physical health around one year after the diagnosis, but only among colorectal cancer patients. This finding suggests that psychosocial programs may be beneficial for colorectal cancer patients’ health recovery upon completion of treatment, specially for whom show elevated depressive symptoms around the time of diagnosis and treatment. Similar program would be also desirable for lung cancer patients, and benefit might also be found for their caregivers’ shorter-term physical health. Our results also suggest that if such program becomes effective in reducing depressive symptoms of both lung cancer patients and their caregivers, caregivers could benefit further by improving their mental health.

Third, female patients’ greater depressive symptoms were significantly related to poorer physical health of their caregivers, whereas female caregivers’ depressive symptoms were not related to their patients’ QOL. Male patients’ greater depressive symptoms were significantly related to poorer mental health of their caregivers, whereas male caregivers’ depressive symptoms were not related to their female patients’ QOL. These cross-over effects are consistent with the general notion that gender plays a significant role in interpersonal contexts [6, 7, 12–14] and provide further evidence about the differential role of gender in different aspect of QOL: while women’s dysphoric mood when she is a patient appears to influence their family members’ poorer physical functioning, men’s dysphoric mood when he is a patient influences their family caregivers’ poorer mental functioning.

Fourth, female caregivers whose depressive symptom levels were similar to those of their female patients reported better mental health but poorer physical health. The former finding suggests the possibility that when caring for female cancer patients, female caregivers may feel psychosocially inadequate, reporting poorer mental health when they do not share similar levels of depressive mood with their patients. The latter finding suggests that the same female caregivers in such circumstance are physically energized. On the other hand, female caregivers of male patients whose depressive symptom levels differ from the patients, probably greater than the patients as univariate paired comparison results shown, reported poorer mental health. The findings contribute to the literature by providing more refined evidence about the often nuanced gender effects in the interpersonal and medical context of cancer care. Women’s QOL is differentially affected by their partners’ depressive mood depending on their stand in dysphoric mood compared with their partner’s, their partners’ gender, their role being a caregiver, and the kinds of QOL examined.

Our findings suggest that managing depressive symptoms at an earlier phase of cancer survivorship is crucial not only for female patients’ own mental health but also for the mental health of their caregivers. For female patients who experience elevated depressive symptoms or have pre-morbid depression, psychosocial programs should not only target efforts to reduce depressive symptoms in both patients and caregivers [39, 40] but also seek to educate male caregivers about how to effectively provide emotional support to their female patients. Educating caregivers regarding how best to utilize alternate or additional resources for obtaining emotional support for themselves may also be beneficial in protecting caregivers from compromised quality of life due to cancer in the family.

Limitations and Directions for Future Studies

Several limitations of our study should be noted. First, all variables were self-reported and may not reflect objective depression and health status. Future studies should include behavioral and physiological indicators of depression and quality of life as well as (co-)morbid conditions. Second, data on patients and caregivers were not collected at the same time point and only patients’ data were collected longitudinally. Future studies need to investigate longer-term effect of depressive symptoms at individual and dyadic levels on each person’s quality of life with narrower gap between patients’ and caregivers’ data collection times. Third, generalizability of the findings is limited to more likely for male patients and participants who are Caucasian, relatively educated, and relatively affluent. Future studies are needed with ethnic minorities, individuals of lower socioeconomic status, and a more even number of patients by gender. Examining other factors that may affect the dyads’ cancer experience, such as the patients’ objective functional status, the perceived burden of caregiving, and the presence of other support and services, as well as relationship satisfaction and duration, and age and lifespan development status that may affect the mutuality in depressive symptoms will be also fruitful.

Conclusions

Despite these limitations, the findings add significant information to a growing body of research on the quality of life of cancer patients and their family caregivers. Our findings suggest that when a family is dealing with a major illness such as cancer, the patients’ depressive symptoms plays a key role not only in their own but also their family caregivers’ well-being. Gender and role (female patients) also had greater influence on the association between depressive symptoms and quality of life of their own as well as their partners. Findings suggest that both cancer patients and their partners should be included in psychosocial programs that are sensitive to the role of gender and that enhance their ability to manage depression when dealing with cancer in the family.

Acknowledgement

This study was supported by grants from the National Cancer Institute (U01 CA93324, U01 CA93326, U01 CA93329, U01 CA93332, U01 CA93339, U01 CA93344, and U01 CA93348) and the Department of Veterans Affairs (CRS 02-164). Writing of this manuscript was supported by the Sylvester Comprehensive Cancer Center, University of Miami, FL, to the first author. The first author dedicates this research to the memory of Heekyoung Kim.

Footnotes

Disclaimer: None of the authors have a financial disclosure or conflict of interest. The views expressed represent those of the authors and not those of the National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health. The contributions of Joan Griffin and Julia Rowland to this article were prepared as part of their official duties as United States Federal Government employees.

References

- 1.Dunn LB, Cooper BA, Neuhaus J, West C, Paul S, Aouizerat B, Abrams G, Edrington J, Hamolsky D, Miaskowski C. Identification of distinct depressive symptom trajectories in women following surgery for breast cancer. Health Psychol. 2011;30:683–692. doi: 10.1037/a0024366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Langer S, Abrams J, Syrjala K. Caregiver and patient marital satisfaction and affect following hematopoietic stem cell transplantation: A prospective, longitudinal investigation. Psycho-Oncol. 2003;12:239–253. doi: 10.1002/pon.633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pitceathly C, Maguire P. The psychological impact of cancer on patients' partners and other key relatives: a review. Euro J Cancer. 2003;39:1517–1524. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(03)00309-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kim Y, Duberstein PR, Sörensen S, Larson MR. Levels of depressive symptoms in spouses of people with lung cancer: Effects of personality, social support, and caregiving burden. Psychosomatics. 2005;46:123–130. doi: 10.1176/appi.psy.46.2.123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vanderwerker LC, Laff RE, Kadan-Lottick NS, McColl S, Prigerson HG. Psychiatric disorders and mental health service use among caregivers of advanced cancer patients. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:6899–6907. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.01.370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hagedoorn M, Sanderman R, Bolks HN, Tuinstra J, Coyne JC. Distress in couples coping with cancer: A meta-analysis and critical review of role and gender effects. Psychol Bull. 2008;134:1–30. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.134.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hodges LJ, Humphris GM, Macfarlane G. A meta-analytic investigation of the relationship between the psychological distress of cancer patients and their carers. Soc Sci Med. 2005;60:1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.04.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hagedoorn M, Puterman E, Sanderman R, Wiggers T, Baas PC, van Haastert M, DeLongis A. Is self-disclosure in couples coping with cancer associated with improvement in depressive symptoms? Health Psychol. 2011;30:753–762. doi: 10.1037/a0024374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kim Y, Kashy DA, Wellisch DK, Spillers RL, Kaw C, Smith T. Quality of life of couples dealing with cancer: Dyadic and individual adjustment among breast and prostate cancer survivors and their spousal caregivers. Ann Beh Med. 2008;35:230–238. doi: 10.1007/s12160-008-9026-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ganz PA, Desmond KA, Leedham B, Rowland J, Meyerowitz BE, Belin TR. Quality of life in long-term, disease-free survivors of breast cancer: A follow-up study. J Nat Cancer Inst. 2002;94:39–49. doi: 10.1093/jnci/94.1.39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Holland JC, Reznick I. Pathways for psychosocial care of cancer survivors. Cancer. 2005;104:2624–2637. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Miller B, Cafasso L. Gender differences in caregiving: Fact or artifact. Gerontologist. 1992;32:498–507. doi: 10.1093/geront/32.4.498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Antonoucci TC. An examination of social networks, social support, and sense of control. In: Birren JE, Schaie KW, editors. Handbook of the psychology of aging. 5th edition. San Diego, CA: Academic Press; 2001. pp. 427–453. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hoppmann CA, Gerstorf D, Luszcz A. Spousal associations between functional limitation and depressive symptom trajectories: Longitudinal findings from the Study of Asset and Health Dynamics Among the Oldest Old (AHEAD) Health Psychol. 2011;30:153–162. doi: 10.1037/a0022094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Coyne JC, Smith DA. Couples coping with a myocardial infarction: a contextual perspective on wives' distress. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1991;61:404–412. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.61.3.404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hooker K, Manoogian-O'Dell M, Monahan DJ, Frazier LD, Shifren K. Does type of disease matter? Gender differences among Alzheimer's and Parkinson's disease spouse caregivers. Gerontologist. 2000;40:568–573. doi: 10.1093/geront/40.5.568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yee JL, Schulz R. Gender differences in psychiatric morbidity among family caregivers: a review and analysis. Gerontologist. 2000;40:147–164. doi: 10.1093/geront/40.2.147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Campbell L, Kashy DA. Estimating actor, partner, and interaction effects for dyadic data using PROC MIXED and HLM: A user-friendly guide. Pers Relationship. 2002;9:327–342. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kenny DA, Kashy DA, Cook WL. Dyadic data analysis. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gilbar O. Gender as a predictor of burden and psychological distress of elderly husbands and wives of cancer patients. Psycho-Oncol. 1999;8:287–294. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1099-1611(199907/08)8:4<287::AID-PON385>3.0.CO;2-W. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kim Y, Carver CS, Cannady RS, Shaffer KM. Self-reported medical morbidity among informal caregivers of chronic illness: The case of cancer. Quality Life Res. 2013;22:1265–1272. doi: 10.1007/s11136-012-0255-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yancik R, Ganz PA, Varricchio CG, Conley B. Perspectives on comorbidity and cancer in older patients: Approaches to expand the knowledge base. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19:1147–1151. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.4.1147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Foxall MJ, Gaston-Johansson F. Burden and health outcomes of family caregivers of hospitalized bone marrow transplant patients. J Adv Nurs. 1996;24:915–923. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.1996.tb02926.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ayanian JZ, Chrischilles EA, Wallace RB, Fletcher RH, Fouad MN, Kiefe CI, Harrington DP, Weeks JC, Kahn KL, Malin JL, Lipscomb J, Potosky AL, Provenzale DT, Sandler RS, van Ryn M, West DW. Undertanding cancer treatment and outcomes: The Cancer Care Outcomes Research and Surveillance Consortium. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:2992–2996. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.06.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.van Ryn M, Sanders S, Kahn K, van Houtven C, Griffin JM, Martin M, Atienza AA, Phelan S, Finstad D, Rowland J. Objective burden, resources, and other stressors among informal cancer caregivers: A hidden quality issue? Psycho-Oncol. 2011;20:44–52. doi: 10.1002/pon.1703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Amirkhanyan AA, Wolf DA. Parent care and the stress process: Findings from panel data. J Gerontol: Soc Sci. 2006;61B:S248–S255. doi: 10.1093/geronb/61.5.s248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gallo WT, Bradley EH, Siegel M, Kasl SV. Health effects of involuntary job loss among older workers: Findings from the Health and Retirement Survey. J Gerontol: Soc Sci. 2000;55B:S131–S140. doi: 10.1093/geronb/55.3.s131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Andersen EM, Carter WB, Malmgren JM, Patrick DL. Screening for depression in well older adults: Evaluation of a short form of the CES-D. Am J Prev Med. 1994;10:77–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ware JE, Jr, Kosinski M, Keller S. SF-12 Physical and Mental Health Summary Scales: A User's Manual. 2nd ed. Boston, MA: Health Institute, New England Medical Center; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Piccirillo JF. Importance of comorbidity in head and neck cancer. Laryngoscope. 2000;110:593–602. doi: 10.1097/00005537-200004000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Piccirillo JF, Tiemey RM, Costas I, Grove L, Spiltznagel EL., Jr Prognostic importance of comorbidity in a hospital-based cancer registry. JAMA. 2004;291:2441–2447. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.20.2441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Arbuckle JL. IBM SPSS Amos 21 User’s Guide. Chicago, IL: SPSS Inc; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bollen KA, Stine RA. Bootstrapping goodness-of-fit measures in structural equation models. In: Bollen KA, Long JS, editors. Testing structural equation models. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1993. pp. 111–135. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jöreskog KG, Sörbom D. LISREL VI User's Guide. 3rd. Mooresville, IL: Scientific Software; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hu L, Bentler PM. Cutoff criteria for fit indices in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling. 1999;6:1–55. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ries LAG, Melbert D, Krapcho M, Mariotto A, Miller BA, Feuer EJ, Edwards BK. SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975–2005. [accessed September 10, 2013];National Cancer Institute, based on November 2007 SEER data submission. Available from URL: http://seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2005/

- 37.Braun M, Mikulincer M, Rydall A, Walsh A, Rodin G. Hidden morbidity in cancer: Spouse caregivers. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:4829–4834. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.10.0909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kim Y, Wellisch DK, Spillers RL. Effects of psychological distress on quality of life of adult daughters and their mothers with cancer. Psycho-Oncol. 2008;17:1129–1136. doi: 10.1002/pon.1328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jacobsen PB, Wagner LI. A new quality standard: The integration of psychosocial care into routine cancer care. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:1154–1159. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.39.5046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Northouse LL, Katapodi MC, Song L, Zhang L, Mood DW. Interventions with family caregivers of cancer patients: Meta-analysis of randomized trials. CA: Cancer J Clin. 2010;60:317–339. doi: 10.3322/caac.20081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]