Abstract

Background

We report intra- and postoperative complications of unicompartmental knee arthroplasty (UKA).

Methods

This study was conducted on 246 cases of UKA which were performed for degenerative osteoarthritis confined to the medial compartment, from May 2002 to May 2010, for which follow-up periods longer than one year were available. Complications were divided into intra- and postoperative complications. Pre- and postoperative clinical scores, the range of motion, and radiologic findings were analyzed.

Results

Complications developed in a total of 24 cases (9.8%, 24/246). Among them, 6 cases had intraoperative complications while 18 had postoperative complications. Among the 6 intraoperative complications, one fracture of the medial tibial condyle, two fractures of the intercondylar eminence, one rupture of the medial collateral ligament, one widening of the peg hole leading to femoral component malposition and late failure, and one total knee arthroplasty (TKA) conversion of a large bony defect of tibial avascular necrosis were observed. Among the 18 postoperative complications, four cases of aseptic loosening of the femoral component, one soft tissue impingement due to malalignment, nine cases of polyethylene bearing dislocation, one case of suprapatellar bursitis, one periprosthetic fracture, one TKA conversion due to medial component overhanging, and one TKA conversion due to pain of unexplained cause were observed.

Conclusions

The mid-term clinical outcomes of UKA were excellent in our study. However, the incidence of complications was very high (9.8%). To prevent intra- and postoperative complications, proper selection of the patients and accurate surgical techniques are required.

Keywords: Unicompartmental knee arthroplasty, Intraoperative complications, Postoperative complications

Recently, good clinical outcomes for unicompartmental knee arthroplasty (UKA) were reported.1) Clinical results comparable to total knee arthroplasty (TKA) have been reported, even when including long-term follow-up. Many studies have reported satisfactory results regarding the clinical outcomes after UKA, such as reduction of pain after surgery, restoration of the range of motion, correction of angle deformity, and improvement of clinical knee scores as well as functional scores.2,3,4,5) In addition, UKA, which is limited to a single compartment, can remove the small bony lesion of the joint line only in patients with osteoarthritis; thus, it has the advantages of minimizing bone resection, reducing the use of polyethylene and bone cement, and preserving more normal knee functions in comparison with TKA, thereby resulting in a shorter operation time and fast recovery. Hence, the morbidity period after surgery is short, and good joint motion can be obtained.6)

However, UKA also has some shortcomings, such as difficulties in the surgical techniques, subluxation of the tibiofemoral joint due to inaccurate location, migration of prosthesis, infection, and bone defects developed during revision. Despite the above mentioned technical difficulties, complications of UKA have rarely been reported.7,8,9)

In this study, we reported the intraoperative complications that were developed during the procedure and the postoperative complications during the follow-up periods, together with a review of the literature.

METHODS

We retrospectively reviewed 245 patients (246 knees) who underwent medial UKA between May 2002 and May 2010 for degenerative arthritis developed in the medial compartment of the knee, and tracked the follow-up for more than 1 year. There were 37 men and 208 women; overall mean age was 64.3 years (range, 50 to 76 years). The mean follow-up period was 2.8 years (range, 1 to 8 years) (Table 1). For all patients, arthroscopy was performed before the procedure for accurate selection of UKA candidates. During the arthroscopic evaluations, patients with torn anterior cruciate ligaments or with articular cartilage defects higher than grade 3 or 4 (outerbridge classification) in the lateral compartment were excluded. Patients with previous high tibial osteotomy, a femorotibial angle of more than valgus 15° or varus 10°, lateral unicompartmental replacement, and ligamentous laxity and instability were also excluded. All UKA procedures were performed with Oxford Uni (Biomet Ltd., Bridgent, UK), and were carried out by the two senior authors. Approval was obtained from the Institutional Review Board of The Catholic University of Korea.

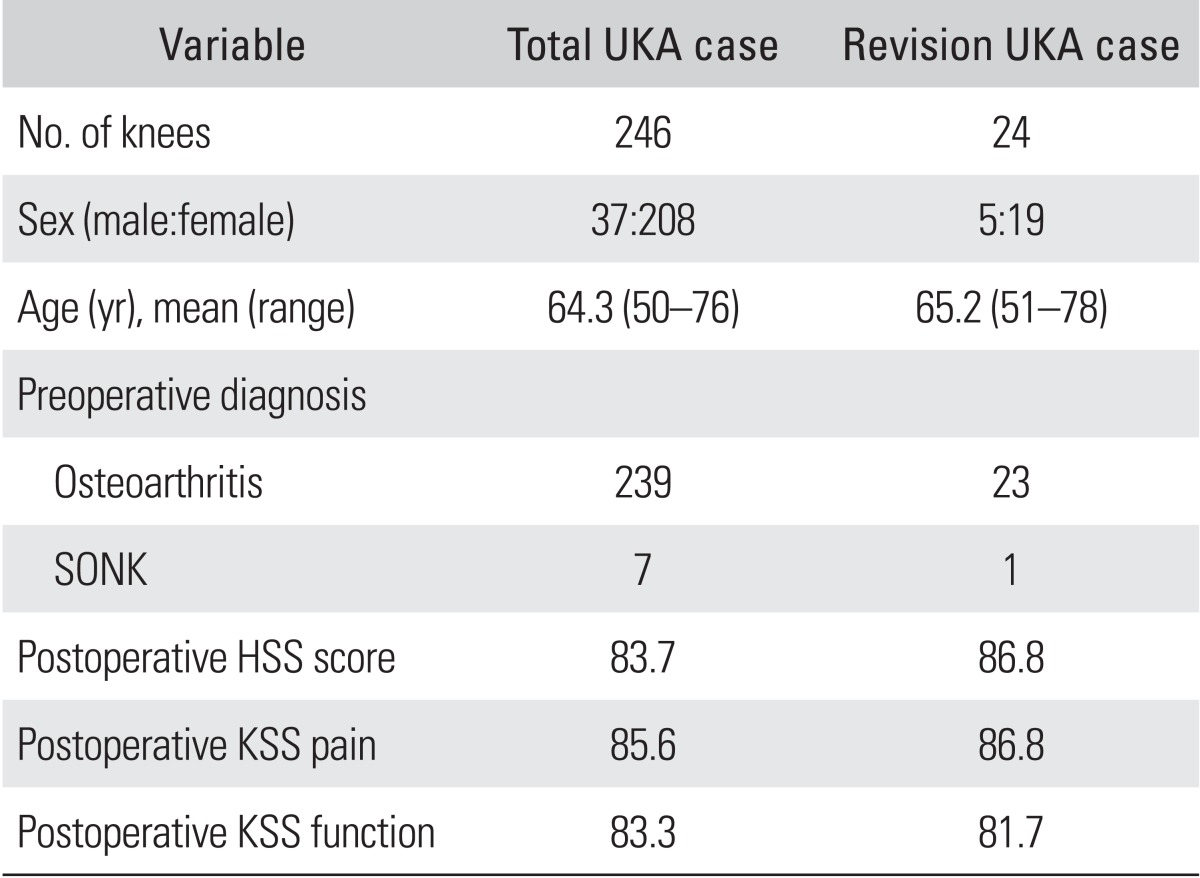

Table 1.

Patient Demographics

UKA: unicompartmental knee arthroplasty, SONK: spontaneous osteonecrosis of the knee, HSS: Knee score of the Hospital for Special Surgery, KSS: Knee Society Score.

We investigated and analyzed the complications. Complications were divided into those which occurred intraoperatively, and those which occurred postoperatively. Intraoperative complications were defined as complications that were developed while performing the UKA procedure. Postoperative complications were defined as implant-related problems, such as loosening of the components and soft tissue problems developed after UKA, including cases that underwent revision operation. The range of motion and clinical outcomes, such as Knee Society Score (KSS) and Hospital for Special Surgery (HSS) knee scores, were evaluated at final follow-up.

RESULTS

In a total of 246 cases, complications were developed in 24 cases (9.8%). They occurred in 5 men and 19 women, with a mean age of 65.2 years (range, 51 to 76 years) (Table 1). Intraoperative complications were seen in 6 cases, while postoperative complications occurred in 18 cases (Table 2). No definite complications of infection or deep vein thrombosis were observed in any of the cases.

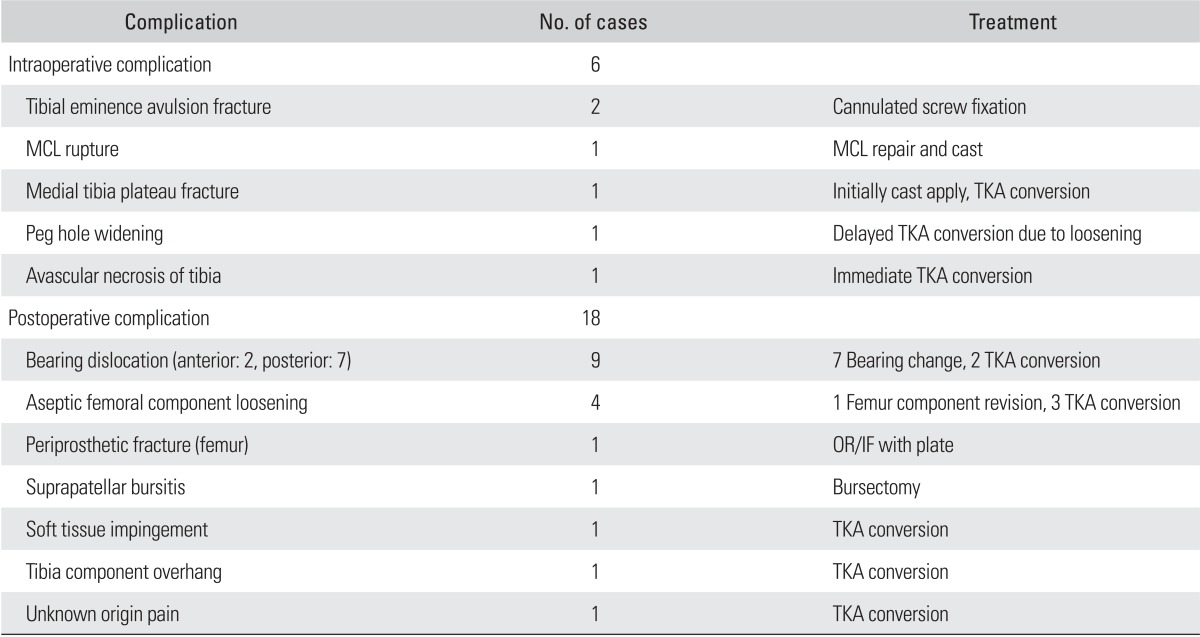

Table 2.

Complications of Unicompartmental Knee Arthroplasty

MCL: medial collateral ligament, TKA: total knee arthroplasty, OR/IF: open reduction and internal fixation.

Intraoperative Complications

Intraoperative complications were developed in a total of 6 cases (1 male, 5 female). The mean age was 70 years (range, 51 to 78 years). The following intraoperative complications were observed: fracture of the medial tibial condyle during operation (1 case), intercondylar eminence fracture (2 cases), rupture of the medial collateral ligament (1 case), TKA conversion of large bony defect of tibial avascular necrosis (1 case), and widening of the peg hole and mismatch of the posterior femoral condyle cutting level leading to femoral component malposition (1 case). The malpositioning of the femoral component eventually caused loosening of the femoral component (Table 2).

Postoperative Complications

Postoperative complications were developed in 18 cases (4 male, 14 female). The mean age was 66 years (range, 54 to 78 years). These postoperative complications were observed from 2 months to 7 years, postoperatively (mean duration, 24.6 months). The following postoperative complications were observed: aseptic loosening of the femoral component (4 cases), soft tissue impingement due to malalignment (1 case), polyethylene bearing dislocation (9 cases) and suprapatellar bursitis (1 case), periprosthetic fracture (1 case), irritation of the medial joint line due to overhanging of the tibial components by more than 5 mm (1 case), and an unexplained cause (1 case). The most common complications were polyethylene bearing dislocation (9 cases) and aseptic loosening of the femoral components (4 cases). Revision operation was performed for all of the cases with postoperative complications. Revision procedures were as follows: change of femoral component (1 case), conversion to TKA (8 cases), change of bearing components (7 cases), bursectomy of the suprapatellar bursa (1 case), and minimally invasive osteosynthesis (1 case). The mean time until reoperation was 22.3 months (range, 2 to 106 months) (Table 2).

Dislocation of polyethylene bearing component

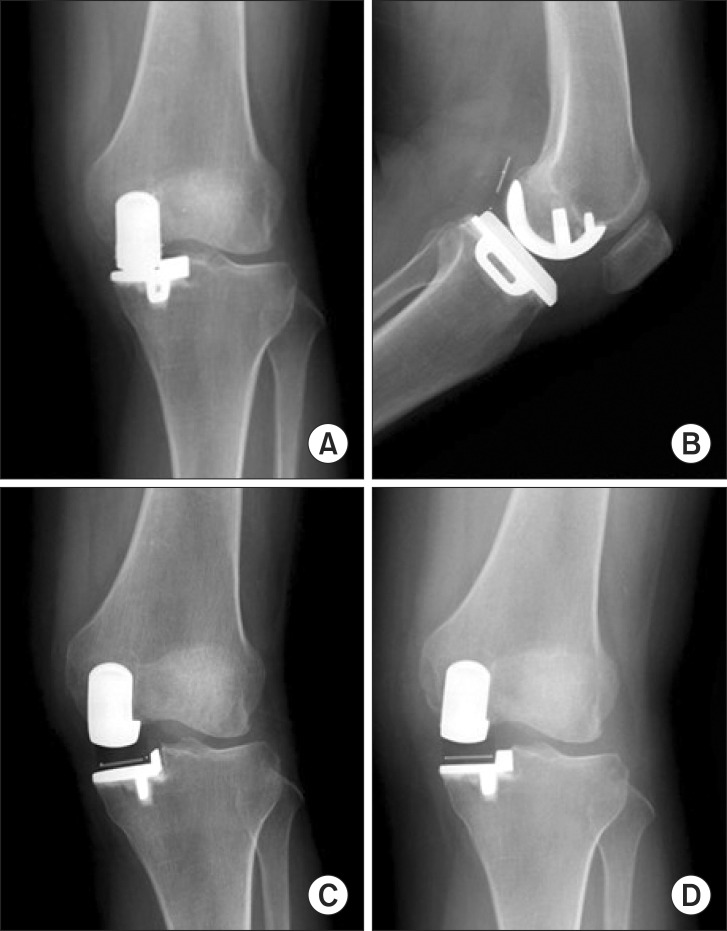

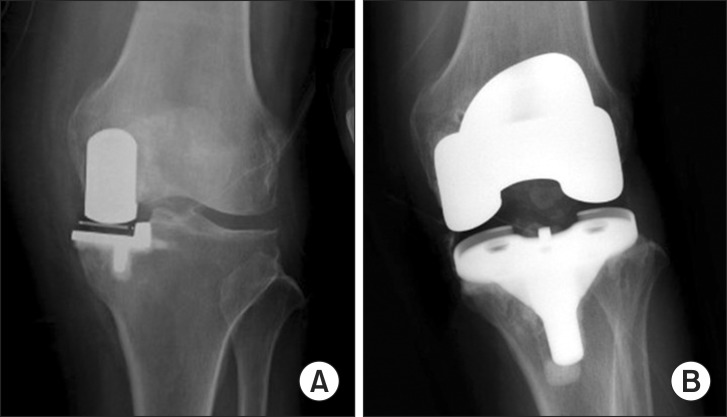

Polyethylene bearing dislocation was developed in 9 cases (3.6%), including three males and 6 females (mean age, 61.4 years; range, 54 to 70 years). This complication was developed most commonly at the average time of 3.7 months (range, 2 to 7 months) after surgery. Simple bearing dislocations were treated by changing the bearing components. Dislocated bearings were replaced with bearing components that were about 2-3 mm larger. For the cases which were accompanied with component loosening, revision TKA or UKA was performed. After change of the bearing components, the tibiofemoral angle was increased from valgus 6.5° ± 2.3° to valgus 8.5° ± 2.7°. In one case, the 3-mm dislocated bearing was replaced with an 8-mm thick bearing, after which the valgus angle was increased from 8.5° to 12.6° (Fig. 1). The patient complained of mild posterolateral knee discomfort, but her knee function was good. The valgus angle was found to have decreased at follow-up, which was suspected to be due to adaptation to the ligament tension. Interestingly, one posterior bearing dislocation recurred again after revision of the dislocation, but spontaneous reduction of the dislocated bearing was developed (Fig. 2). That patient was very satisfied with the clinical results without any problems at the 2-year follow-up.

Fig. 1.

A 3-mm dislocated bearing (A, B) was replaced with an 8-mm thick bearing (C), resulting in an increase of the valgus angle from 8.5° (A) to 12.6° (C). The final follow-up radiograph showed reduction of the valgus angle from 12.6° (C) to 9° (D).

Fig. 2.

A dislocated bearing (A) was replaced with a thicker bearing (B). Posterior bearing dislocation recurred after the revision of bearing dislocation (C), but spontaneous reduction of the dislocated bearing was observed (D).

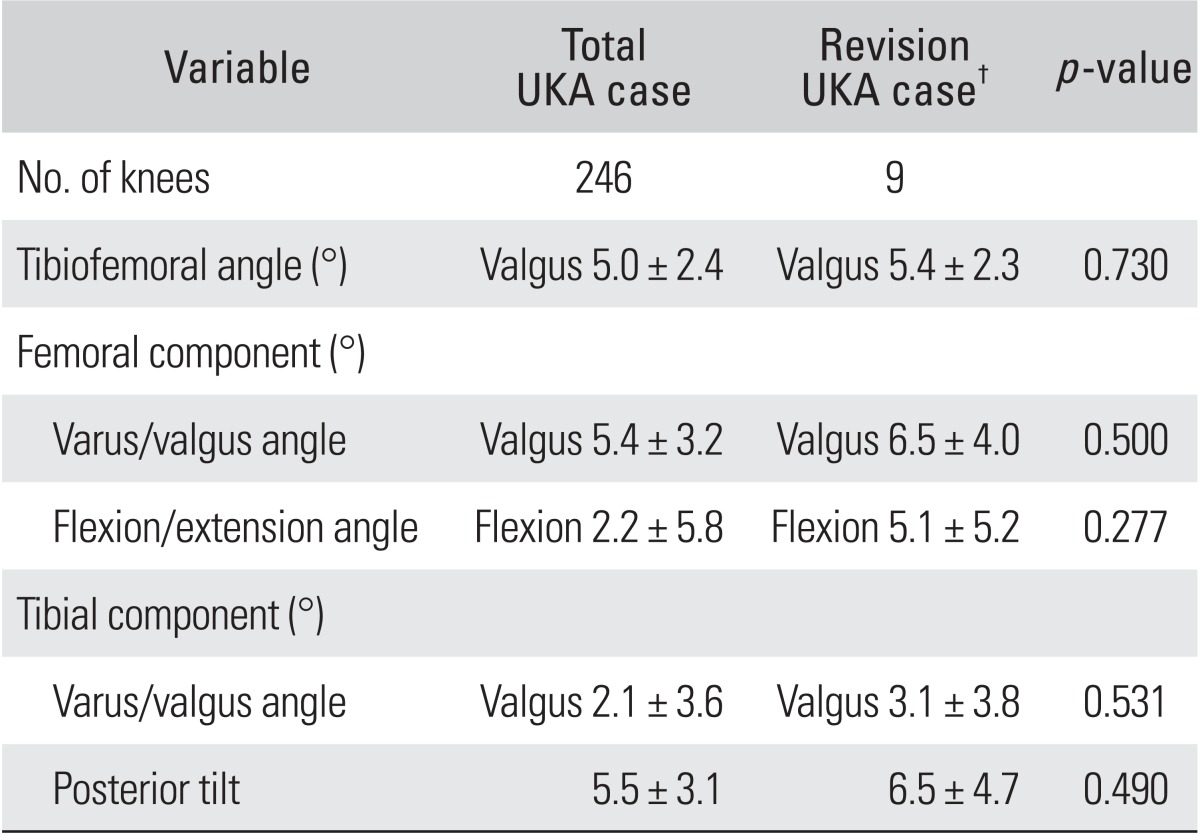

In cases for which only a bearing change was performed, the radiological parameters such as preoperative average tibiofemoral angle, varus/valgus angle and flexion/extension angle (femur), and varus/valgus angle and posterior tilt angle (tibia) were measured. In all cases, there were no signs of loosening of the tibial or femoral side. The average preoperative tibiofemoral angle was valgus 5.4° ± 2.3°. The tibiofemoral angle in the revision group was larger than that of the group without revision, but there were no significant differences between the two groups (p = 0.730) (Table 3). Varus/valgus angle (femur component) was measured as valgus 6.5° ± 4.0°; flexion/extension angle (femur component): flexion 5.1° ± 5.2°; varus/valgus angle (tibia component): valgus 3.1° ± 3.8°; and posterior tilt (tibia component) angle: 6.5° ± 4.7°. There were no significant differences between these radiologic parameters of the normal and revision (bearing change) cases.

Table 3.

Comparison of the Postoperative Radiologic Findings*

*Between the total unicompartmental knee arthroplasty (UKA) cases and the revision UKA cases due to bearing dislocation. †Revision UKA cases: cases with polyethylene bearing component dislocation only.

Femoral component loosening

In the follow-up radiologic evaluations, component loosening was found in 4 cases, 1 male and 3 female, all of which the loosening was developed in the femoral component. The mean age was 64.2 ± 12.8 years (range, 51 to 78 years). The mean time until revision surgery was 44.8 months (range, 4 to 106 months). A revision of the femoral component was performed in 1 case, and TKA conversion was performed in 3 cases. In this subgroup of femoral component loosening (4 cases), the varus/valgus angle (femur) was measured as valgus 9.1° ± 2.7°.

Miscellaneous

In the case of conversion to TKA, a 5-mm overhang of the medial compartment caused irritation of the medial aspect of the knee, resulting in cellulitis-like symptoms. We have experienced several cases of tibial component overhang, owing to the smaller posteromedial tibia size of the Korean population. However, in this case, conservative treatment such as rest and intravenous antibiotics was performed, but the pain continued. TKA conversion was performed 16 months later (Fig. 3). In another case, suprapatellar bursitis developed, and bursectomy of the suprapatellar bursa was performed (Fig. 4). After the arthroscopy which was performed before the UKA procedure, the suprapatellar bursitis was developed in the drain site. It was supposed that the cause was irritation of the bursa after intra-articular bleeding from the UKA procedure. One case of soft tissue impingement due to malalignment, and one case of unexplained severe pain also resulted in TKA conversion (Fig. 5). One periprosthetic fracture occurred in the distal femur, after which minimal invasive osteosynthesis was performed using the plate.

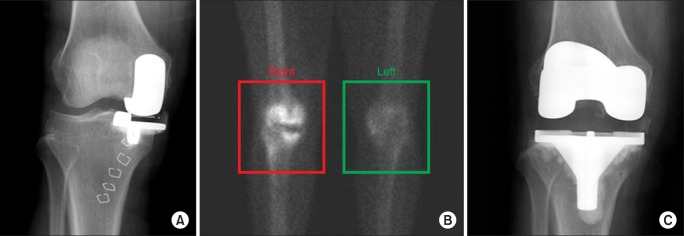

Fig. 3.

(A) A 5-mm overhang of the medial compartment caused irritation of the medial aspect of the knee, resulting in cellulitis-like symptoms. (B) A 3-phase bone scan of the right knee showed some increased radioisotope uptake on all three phases. (C) Sixteen months later, a conversion to total knee arthroplasty was performed.

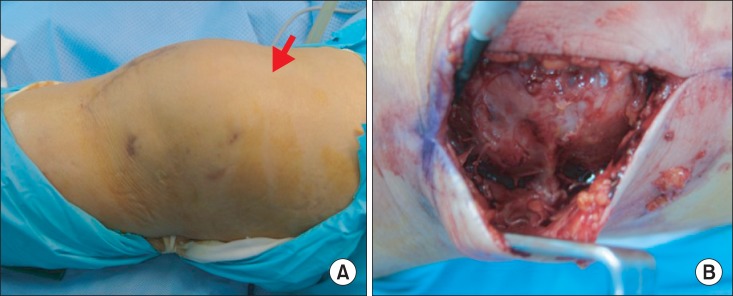

Fig. 4.

(A) Recurrent suprapatellar bursitis developed along the hemovac site (arrow). (B) Open excision was performed 4 months later.

Fig. 5.

Because of the severe unexplained pain in a 69-year-old female (A), conversion to total knee arthroplasty was performed at 2 months postsurgery (B).

At the final follow-ups, the overall HSS score had improved from an average of 70 points preoperatively to a final score of 97 points. In the complication group, the HSS score had improved from 65.7 to 83.7 points. The mean KSS (pain) and functional score of all the patients improved from 65 and 60 preoperatively to final scores of 87 and 82, respectively. At the last follow-up, the mean maximum flexion angle had improved from 7.5°-115° to 5°-119°.

DISCUSSION

There have been several complications reported after performing UKA, such as rupture of the medial or lateral collateral ligaments, dislocation of the polyethylene bearing, dissociation of the prosthesis, degenerative changes in the opposite compartment, and fracture of the medial proximal tibia.3,10,11,12,13,14) Previous literature reported that the failure was caused by the aseptic loosening of the femoral or tibial prosthesis, dislocation or instability of the prosthesis, malalignment of the prosthesis, deep infection, periprosthetic fracture, abrasion of the polyethylene liner, the progression of arthritis, etc.5,7,8,9)

UKA is a demanding procedure that requires special experience, and includes a risk of early failure. Lindstrand et al.15) reported that 8 revisions performed in 123 operated knees due to loosening, subsidence, or fracture. These revisions were performed within 1 year, and were mostly related to the operative technique used. In our series, the duration until reoperation was approximately 22.3 months. Berger et al.10) reported that only 2 patients (2 knees) out of 62 cases (mean follow-up of 12 years) with well-fixed components underwent a revision to TKA, at seven and eleven years, because of progression of patellofemoral arthritis. At the final follow-up, no radiographically loose component was found, and there was no evidence of periprosthetic osteolysis in that study.

In our study, complications developed in 9.8% of the cases. Contrary to the previous study, we also included analysis of the intraoperative complications. These problems are usually preventable by having adequate surgical techniques and plans. Also, change of initially planned UKA would require longer surgical time, and increase the perioperative complications during the procedure. This means that having an accurate surgical technique is very important in the UKA procedure. Compared to the other reports, occurrence of suprapatellar bursitis and medial tibial plateau fracture were very unusual in our series. Barrett and Scott16) suggested that errors in patient selection were responsible for the failure in 31%, and also Saldanha et al.17) also noted that 13 failures among 100 cases were due to poor patient selection. However, since arthroscopy was performed in all patients in our series and patients with higher than outerbridge grade 3 articular cartilage injury in the lateral or patellofemoral compartments were excluded, the possibility of having poor patient selection for the UKA procedure was reduced. However, 1 patient developed suprapatellar bursitis in the drain site after the arthroscopic procedure.

Pandit et al.18) reported a ten-year survival rate of 96%, if all implant-related reoperations are considered failures and the incidence of implant-related reoperations was 2.9% during the mean follow-up of 5.6 years. The most common reason for further surgical intervention was progression of arthritis in the lateral compartment (0.9%), followed by dislocation of the bearing (0.6%), and revision for unexplained pain (0.6%). Berger et al.10) reported that progressive patellofemoral arthritis was the primary mode of failure. The postoperative tibiofemoral angle has also been considered to be a very important factor determining the prognosis of the surgery, and the level of abrasion and instability of the prosthesis. Tibial or femoral component malalignment has been found to lead to early failure.19) Malalignment of the prosthesis or the generation of excessive tension during flexion or complete extension may limit the range of motion, possibly causing loosening of the prosthesis to develop over time. Postoperative alignment was reported to be crucial for decreasing the rate of revision surgery. Perkins and Gunckle14) reported in a study with a 6-year follow-up period that the possibility of needing revision surgery was high when the postoperative tibiofemoral angle was larger than 3° varus, or larger than 7° valgus. In our small series with femoral component loosening, it was observed that valgus malalignment of the femoral components may eventually cause early femoral component loosening, but no statistical significance was obtained, owing to the small number of cases (only 5). Fracture of the medial tibial condyle during insertion of the tibial component occurred in 1 case. This was due to the natural tendency to place the tibial tray too medial in the varus knee, in order to avoid impingement on the anterior cruciate ligament. However, this practice could lead to a metaphyseal fracture of the tibia due to decreased bone support beneath the tibial components.

In our study, the most prevalent complication observed was polyethylene bearing dislocation. A bearing change can be performed for cases of simple bearing dislocation, but component revision or conversion to TKA is needed when this is accompanied by femoral or tibial component loosening. Usually in cases of bearing dislocation, the dislocated bearing was removed and a bearing approximately 2-3 mm larger was inserted. Interestingly, in one case where a bearing of 3 mm in thickness was replaced with an 8-mm bearing, excessive valgus tibiofemoral angle was developed. Generally, bearing change could be done by replacement with a 2-3 mm larger sized bearing. Since lateral compartmental arthritis may develop if excessive valgus angles are induced, careful attention should be given. In our case, the 6-month follow-up revealed the valgus tibiofemoral angle to be reduced from 12° to 8° because of ligament adaptation. Bearing dislocations have been associated with proximal tibial varus greater than 5°, excessive femoral component varus or valgus, and excessive postoperative tibial slope.20,21) In our series, the tibiofemoral angle increased from valgus 6.5° to valgus 8.5° after the bearing change. However, there were no significant differences between the several radiologic factors, such as the pre- and postoperative tibiofemoral angles, varus/valgus angles (femur, tibia component) flexion/extension angles (femur component), and posterior tilt angles (tibia component). Compared to the normal group, the tibiofemoral angle showed no significant differences in the complication group (p = 0.079). We suspected that the cause of bearing dislocation was multifactorial, and that lifestyle, including activities such as squatting, was one of the most important factors in Asian populations. Emerson et al.11) reported that mobile bearings have the disadvantages of higher complication and early revision rates, resulting from bearing dislocation and impingement syndromes caused by suboptimal operation technique or instability. Interestingly, spontaneous reduction was developed in 1 revision case in this study. After bearing change, a 2nd posterior dislocation was developed, which reduced spontaneously without additional treatment. The exact reason for this spontaneous reduction could not be identified. It was suspected that lax capsular tension might have caused spontaneous reduction of the posterior dislocated bearing. One particular case, which was not observed in other studies, was the recurrent suprapatella bursitis developed after performing arthroscopy. Even though several aspirations were performed, suprapatellar bursitis continued to progress, until open excision of the suprapatella bursitis was finally performed.

Generally, the size of the tibia of Koreans is relatively smaller than Caucasians. In one case, the protruded tibial component irritated the posteromedial area of the knee joint continuously, causing cellulitis-like symptoms and pain to develop. This protruded tibial component was finally converted into TKA. A previous study showed that Oxford designs resulted in mediolateral overhang for all the comparative anteroposterior dimensions in Asian populations.9) Manufacturing of prostheses with an adequate size to fit to the bone structure of Asian populations would be required to reduce associated complications.

In a total of 246 cases, intra- and postoperative complications were developed in 24 cases (9.8%). Bearing dislocation was the most common complication in our series. For preventing these complications and improving clinical results, an accurate preoperative surgical plan and skillful surgical technique are required.

Footnotes

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

References

- 1.Choy WS, Kim KJ, Lee SK, Yang DS, Lee NK. Mid-term results of oxford medial unicompartmental knee arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Surg. 2011;3(3):178–183. doi: 10.4055/cios.2011.3.3.178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Goodfellow J, O'Connor J, Murray DW. The Oxford meniscal unicompartmental knee. J Knee Surg. 2002;15(4):240–246. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Marmor L. Unicompartmental knee arthroplasty: ten- to 13-year follow-up study. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1988;(226):14–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Newman JH, Ackroyd CE, Shah NA. Unicompartmental or total knee replacement? Five-year results of a prospective, randomised trial of 102 osteoarthritic knees with unicompartmental arthritis. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1998;80(5):862–865. doi: 10.1302/0301-620x.80b5.8835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rougraff BT, Heck DA, Gibson AE. A comparison of tricompartmental and unicompartmental arthroplasty for the treatment of gonarthrosis. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1991;(273):157–164. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chassin EP, Mikosz RP, Andriacchi TP, Rosenberg AG. Functional analysis of cemented medial unicompartmental knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 1996;11(5):553–559. doi: 10.1016/s0883-5403(96)80109-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Aleto TJ, Berend ME, Ritter MA, Faris PM, Meneghini RM. Early failure of unicompartmental knee arthroplasty leading to revision. J Arthroplasty. 2008;23(2):159–163. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2007.03.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Furnes O, Espehaug B, Lie SA, Vollset SE, Engesaeter LB, Havelin LI. Failure mechanisms after unicompartmental and tricompartmental primary knee replacement with cement. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007;89(3):519–525. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.F.00210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Surendran S, Kwak DS, Lee UY, et al. Anthropometry of the medial tibial condyle to design the tibial component for unicondylar knee arthroplasty for the Korean population. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2007;15(4):436–442. doi: 10.1007/s00167-006-0188-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Berger RA, Meneghini RM, Sheinkop MB, et al. The progression of patellofemoral arthrosis after medial unicompartmental replacement: results at 11 to 15 years. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2004;(428):92–99. doi: 10.1097/01.blo.0000147700.89433.a5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Emerson RH, Jr, Hansborough T, Reitman RD, Rosenfeldt W, Higgins LL. Comparison of a mobile with a fixed-bearing unicompartmental knee implant. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2002;(404):62–70. doi: 10.1097/00003086-200211000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Koskinen E, Eskelinen A, Paavolainen P, Pulkkinen P, Remes V. Comparison of survival and cost-effectiveness between unicondylar arthroplasty and total knee arthroplasty in patients with primary osteoarthritis: a follow-up study of 50,493 knee replacements from the Finnish Arthroplasty Register. Acta Orthop. 2008;79(4):499–507. doi: 10.1080/17453670710015490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Murray DW, Goodfellow JW, O'Connor JJ. The Oxford medial unicompartmental arthroplasty: a ten-year survival study. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1998;80(6):983–989. doi: 10.1302/0301-620x.80b6.8177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Perkins TR, Gunckle W. Unicompartmental knee arthroplasty: 3- to 10-year results in a community hospital setting. J Arthroplasty. 2002;17(3):293–297. doi: 10.1054/arth.2002.30413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lindstrand A, Stenstrom A, Ryd L, Toksvig-Larsen S. The introduction period of unicompartmental knee arthroplasty is critical: a clinical, clinical multicentered, and radiostereometric study of 251 Duracon unicompartmental knee arthroplasties. J Arthroplasty. 2000;15(5):608–616. doi: 10.1054/arth.2000.6619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Barrett WP, Scott RD. Revision of failed unicondylar unicompartmental knee arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1987;69(9):1328–1335. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Saldanha KA, Keys GW, Svard UC, White SH, Rao C. Revision of Oxford medial unicompartmental knee arthroplasty to total knee arthroplasty: results of a multicentre study. Knee. 2007;14(4):275–279. doi: 10.1016/j.knee.2007.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pandit H, Jenkins C, Gill HS, Barker K, Dodd CA, Murray DW. Minimally invasive Oxford phase 3 unicompartmental knee replacement: results of 1000 cases. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2011;93(2):198–204. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.93B2.25767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hernigou P, Deschamps G. Alignment influences wear in the knee after medial unicompartmental arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2004;(423):161–165. doi: 10.1097/01.blo.0000128285.90459.12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bradley J, Goodfellow JW, O'Connor JJ. A radiographic study of bearing movement in unicompartmental Oxford knee replacements. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1987;69(4):598–601. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.69B4.3611164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Robinson BJ, Rees JL, Price AJ, et al. Dislocation of the bearing of the Oxford lateral unicompartmental arthroplasty: a radiological assessment. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2002;84(5):653–657. doi: 10.1302/0301-620x.84b5.12950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]