Abstract

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) encapsulated within microparticles (MPs) are likely to have a role in cell-to-cell signaling in a variety of diseases, including atherosclerosis. However, little is known about the mechanisms by which different cell types release and transfer miRNAs. Here, we examined TNF-α-induced release of MP-encapsulated miR-126, miR-21, and miR-155 from human aortic endothelial cells (ECs) and their transfer to recipient cells. ECs were treated with TNF-α (100 ng/ml) in the presence or absence of inhibitors that target different MP production pathways. MPs released in response to TNF-α were characterized by: 1) 70–80% decrease in miRNA/MP levels for miR-126 and -21 but a significant increase in pre-miR-155 and miR-155 (P < 0.05), 2) 50% reduction in uptake by recipient cells (P < 0.05), and 3) diminished ability to transfer miRNA to recipient cells. Cotreatment of donor ECs with TNF-α and caspase inhibitor (Q-VD-OPH, 10 μM) produced MPs that had: 1) 1.5- to 2-fold increase in miRNA/MP loading, 2) enhanced uptake by recipient cells (2-fold), and 3) increased ability to transfer miR-155. Cotreatment of ECs with TNF-α and Rho-associated kinase (ROCK) inhibitor (10 μM) produced MPs with features similar to those produced by TNF-α treatment alone. Our data indicate that TNF-α induced the production of distinct MP populations: ROCK-dependent, miRNA-rich MPs that effectively transferred their cargo and were antiapoptotic, and caspase-dependent, miRNA-poor MPs that were proapoptotic. These data provide insight into the relationship between MP production and extracellular release of miRNA, as well as the potential of encapsulated miRNA for cell-to-cell communication.

Keywords: miRNA release and transfer, TNF-α, atherosclerosis, microparticles, extracellular RNA, endothelial cells

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are a class of short (∼22 nucleotides), highly conserved, single-stranded, noncoding RNAs that posttranscriptionally regulate gene expression (2, 12, 23). With over 2,000 mature miRNAs annotated in the human genome to date, they have emerged as important regulatory molecules that fine-tune protein expression, thereby modulating most aspects of cellular homeostasis (35, 46). However, miRNA-mediated gene repression is complex, and, in addition to their role in normal physiological functions, miRNAs have recently been implicated in a wide array of pathological processes (29, 48), including cardiovascular disease (24). In fact, miRNAs are now recognized as important regulatory molecules in endothelial cells (ECs), vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMCs), platelets, and immune cells that contribute to the initiation and progression of atherosclerosis (24).

While the majority of miRNAs are located within the cell cytoplasm, recent studies have detected miRNAs extracellularly, in various body fluids, including blood (15, 64). Interestingly, the expression of extracellular miRNAs does not necessarily correlate with their respective concentration in maternal cells, suggesting that miRNA release is not random but governed by tightly controlled export mechanisms (13, 22, 49). Extracellular miRNAs are transported in the blood via membrane-encapsulated vesicles [microparticles (MPs), exosomes and apoptotic bodies (34, 49, 55)] or by complexing with extracellular proteins or lipoproteins (1, 8, 17, 26, 34, 52). These transport modalities stabilize and protect miRNAs from degradation by endogenous RNase (10, 20, 37). The regulated packaging, release, and dedicated transport suggest a role for miRNAs in cell-to-cell communication; however, fundamental principles of extracellular miRNA release and transfer remain to be defined.

The EC monolayer, which lines the luminal surface of blood vessels, is an active interface between blood and the vessel wall that regulates vascular homeostasis by responding to and communicating various anti- and proatherogenic stimuli and signals (47). In fact, EC dysfunction and disrupted communication between ECs, VSMCs, platelets, and immune cells are now considered central to all stages of atherosclerosis (44, 45). Recent studies suggest that miRNAs have an integral role in these processes (39, 41, 57, 59, 60, 63) as they are exported from ECs in a tightly regulated, stimulus-dependent manner (13, 22, 33, 55). Changes in the extracellular expression profile and transport of EC-derived miRNAs are likely to reveal important signaling pathways responsible for atherosclerosis in its early stages.

Here, we focused on MP-mediated miRNA transport because MPs are abundant in the plasma, relatively large (100–1,000 nm), and capable of transporting a significant amount of miRNAs. Prior studies have shown that MPs can efficiently transfer their miRNA cargo to various recipient cells with a subsequent change in target gene expression and function (1, 4, 16, 27, 32, 34, 52, 55, 61). However, MP-mediated intercellular communication is likely disrupted under pathological conditions contributing to the development of vascular disease (18). In the current study, we show that TNF-α altered miRNA-mediated communication by endothelial MPs, but TNF-α also induced the production of distinct MP populations that vary in their efficiency of conveying information to recipient cells. These data provide novel insight into miRNA release from ECs and how MP-encapsulated miRNAs may ultimately influence the initiation and progression of atherosclerosis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell culture.

Human aortic endothelial cells (HAECs; Lonza, Walkersville, MD) were cultured in EBM-2 medium in the presence of 5% CO2 at 37°C and were used between passages 4 and 8. Culture medium was changed to fresh Opti-MEM (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA) at the beginning of each experiment, and cells were incubated with vehicle only (control) or TNF-α (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) at a final concentration of 100 ng/ml for 24 h. In separate experimental arms cells were cotreated with TNF-α and the pancaspase inhibitor Q-VD-OPH at 10 μM (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) (5) or the Rho-activated kinase (ROCK) inhibitor Y-27632 at 10 μM (Fisher Scientific, Suwanee, GA) for 24 h. Culture medium was collected at the end of the incubation period, and cells were harvested to extract intracellular miRNA content as detailed below.

MP isolation and quantification.

Culture medium was centrifuged at 800 g for 10 min at 4°C to sediment cellular debris. The cell-free supernatant was further centrifuged at 16,000 g for 20 min at 4°C, and pelleted MPs were resuspended in 100 μl of filtered PBS. To determine the concentration of MPs in the cell medium, a previously described flow cytometry method of quantification was utilized in conjunction with Flow-Count fluorescent beads (Beckman Coulter, Indianapolis, IN) (38). In brief, a standard concentration of 10 μm beads in 10 μl solution was added to either 490 μl of PBS (control tube) or 470 μl of PBS plus 20 μl of resuspended MPs (MP tube). Using flow cytometry (FACSCalibur, BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA), we counted the number of MPs in the 500 μl analysis solution per 5,000 gated bead events. The specific MP count was calculated by subtracting the number of hits in the control tube (background) from the MP count in the sample tubes and the number of MPs per μl medium was calculated as described previously (38).

miRNA isolation and qRT-PCR analysis.

Harvested HAECs and isolated MPs were lysed with QIAzol lysis buffer (Qiagen, Valencia, CA), and their miRNA content was extracted with the commercially available miRNeasy kit (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer's protocol. The assessment of specific miRNA levels was performed by standard protocols from Applied Biosystems and Qiagen. Cycle threshold (Ct) values for the mature and precursor forms of miR-126, -21, and -155 were determined and converted into relative expression levels according to the following formula: relative expression = 2(−Ct). The expression of intracellular miRNAs was normalized to the noncoding, small nuclear RNA molecule U6, as described previously (7). For the MP fraction, the relative miRNA expression level per MP count was determined. All results are presented as fold change vs. the appropriate control.

Uptake of MPs by recipient HAECs.

Isolated MPs were incubated with 10 μM fluorescent calcein-AM (Life Technologies) for 30 min at 37°C. Labeled MPs were washed twice in filtered PBS to remove excess calcein-AM and then were resuspended in Opti-MEM. Flow cytometry (FACSCalibur) was used to count the fluorescent particles, and Opti-MEM was added to each sample as needed to adjust the final donor MP concentration to 200 MPs/μl. This donor MP suspension was added directly to confluent HAECs grown on glass cover slips in six-well plates. After 24 h incubation at 37°C, recipient HAECs were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 10 min and then washed three times with PBS. Possible autofluorescence was quenched with ammonium chloride, and samples were washed again with filtered PBS. After being blocked with 6% BSA for 1 h at room temperature, recipient cells were stained with Rhodamine RedX Phalloidin in 3% BSA (1:100, Invitrogen) for 1 h at room temperature followed by staining with DAPI in 3% BSA (1:1,000, Sigma) for 10 min. After repeat washing cycles, samples were mounted on glass slides with Vectashield and examined under the Olympus Fluoview confocal microscope (Olympus, Center Valley, PA) with a ×60 objective. Donor MP uptake was indicated by green fluorescence inside the recipient cell cytoplasm on Z-stack imaging. Automatic image analysis (Olympus) was performed to quantify MP uptake by at least 50 cells per experimental arm; results are presented as fold change vs. cells incubated with donor MPs from untreated control cells.

MP-mediated transfer of miRNAs to recipient HAECs.

Calcein-AM labeled MPs from control cells and cells treated with TNF-α (100 ng/ml) with or without caspase inhibitor or ROCK inhibitor were added to recipient HAECs at a final concentration of 200 MPs/μl for 2 h. The 2 h time point was chosen to minimize the possibility of MP-induced changes in miRNA transcription, which may occur within a 4–8 h time period based on prior publications (57). Following two consecutive washing steps to ensure the complete removal of residual MPs in the media, recipient cells were lysed and their miRNA content isolated with the miRNeasy kit (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Ct values for the mature and precursor miR-155 were determined and converted into relative expression values. Relative expression values were normalized to U6, and data from each experimental arm were compared with the control.

Apoptosis assay in MP donor and recipient cells.

Recipient cells were incubated with MPs, and caspase-3 activity was determined using the ApoAlert Caspase-3 Colorimetric Assay kit (Clontech Laboratories, Mountain view, CA) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Results were compared with the respective control group and data are presented as fold change.

Statistical analysis.

Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism software (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA). Values are expressed as means ± SD. Unpaired, two-sided Student's t-tests were used to compare data and a P value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Effect of TNF-α on the intracellular expression and release of MP-encapsulated miRNAs.

Intracellular expression of pre- and mature miR-126 was reduced in HAECs treated with TNF-α compared with untreated cells; this effect was evident as early as 2 h. Intracellular pre- and mature miR-21 levels were not significantly altered by TNF-α treatment, but pre-miR-155 expression increased dramatically within the first hour of treatment, and the increased expression was sustained for 24 h. Mature miR-155 levels followed a similar trend with an average 3.5-fold increase in expression after 24 h exposure to TNF-α.

Pre- and mature miR-126 and -21 content in MPs produced by TNF-α-treated ECs was decreased 70–80% compared with that in MPs from control cells (Fig. 1, A and B). In contrast, MPs from TNF-α-treated cells had an increased abundance of pre- and mature miR-155 (P < 0.05, Fig. 1C). The TNF-α-induced changes in MP miRNA content were associated with a fivefold increase in MP count. Together, these data indicate that TNF-α had distinct effects on intracellular expression and release of specific miRNAs.

Fig. 1.

Precursor and mature microRNA (miR)-126 (A), miR-21 (B), and miR-155 (C) content of microparticles (MPs) produced by endothelial cells (ECs) subjected to TNF-α (100 μg/ml) for 24 h. MP-encapsulated microRNA (miRNA) was assessed by the ratio of miRNA level in MP fraction divided by the number of MPs. Values expressed relative to control MPs. *P < 0.05, n = 10.

The production of MPs in response to TNF-α is due, in part, to the activation of caspase signaling pathways (14). Cotreatment of ECs with TNF-α and caspase inhibitor (Q-VD-OPH, 10 μM) attenuated apoptosis and significantly reduced MP production by donor ECs, but it did not alter TNF-α-induced changes in intracellular miRNA abundance (Fig. 2A). Interestingly, MPs produced by ECs treated with TNF-α plus caspase inhibitor were significantly enriched in miR-126, -21, and -155 and their precursors compared with MPs released from cells treated with TNF-α alone (Fig. 2B).

Fig. 2.

Effect of TNF-α (100 ng/ml) plus caspase inhibitor on precursor and mature miR-126, -21, and -155 levels in ECs (A) and MPs (B). Relative levels of intracellular miRNA were normalized to U6 and expressed relative to TNF-α treatment alone (no significant changes, n = 6). MP-encapsulated miRNA was assessed by the ratio of miRNA level in MP fraction divided by the number of MPs. Values expressed relative to TNF-α MPs. caspase-I, caspase inhibitor. *P < 0.05, n = 6.

The RhoA/Rho kinase (ROCK) pathway has also been shown to be responsible for MP production in various cell types, including ECs (3, 53). To further evaluate this pathway's role in miRNA release, we isolated MPs produced by ECs cotreated with TNF-α and ROCK inhibitor (Y-27632, 10 μM) and assessed them for their miRNA content. The number of MPs produced under these conditions was similar to that produced in response to TNF-α alone. Compared with control, MPs released by HAECs cotreated with TNF-α plus ROCK inhibitor had decreased levels of miR-126, -155, and their precursors but no statistical change in the levels of pre- and mature miR-21 (Fig. 3B). Importantly, cotreatment with TNF-α and ROCK inhibitor modestly increased intracellular miRNA levels in HAECs (Fig. 3A), indicating that miRNA release was attenuated, which resulted in their intracellular retention under these conditions. Overall, these findings suggest that TNF-α induced the production two distinct populations of MPs from ECs: 1) ROCK-dependent miRNA-rich MPs and 2) caspase-dependent, miRNA-poor MPs.

Fig. 3.

Effect of TNF-α (100 ng/ml) plus Rho-activated kinase (ROCK) inhibition (Y-27632, 10 µM) on precursor and mature miR-126, -21, and -155 levels in ECs (A) and MPs (B). Relative levels of intracellular miRNA were normalized to U6 and expressed relative to TNF-α treatment alone (*P < 0.05, n = 5). MP-encapsulated miRNA was assessed by the ratio of miRNA level in MP fraction divided by the number of MPs. Values expressed relative to TNF-α MPs. ROCK-I, ROCK inhibitor *P < 0.05, n = 5.

Uptake and miRNA transfer efficiency of MPs generated through the caspase- and ROCK-dependent pathways.

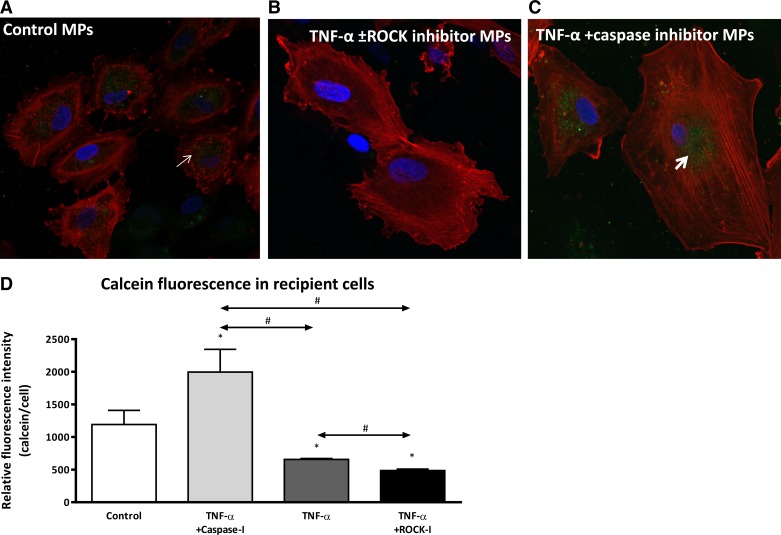

To examine the potential of different endothelial MPs to act as cell-to-cell communicators, we assessed the ability of donor MPs to be taken up and transfer their miRNA contents to recipient cells. The uptake of calcein-AM-labeled donor MPs by recipient HAECs was assessed with fluorescent microscopy and z-stack imaging, which allowed intracellular visualization of the dye. Recipient cell uptake of MPs from TNF-α- and TNF-α plus ROCK inhibitor-treated donor cells was reduced significantly compared with MPs from control HAECs (Fig. 4, A and B). In contrast, the uptake of donor MPs generated in response to TNF-α plus caspase inhibitor was increased twofold compared with control MPs and threefold vs. donor MPs released by HAECs treated with TNF-α alone or TNF-α plus ROCK inhibitor (Fig. 4C). Quantitative analysis of green fluorescence within the recipient cells confirmed the above visual observations (Fig. 4D).

Fig. 4.

MPs from TNF-α- and TNF-α plus ROCK inhibitor-treated donor ECs (B) are not taken up by recipient cells as avidly as MPs from untreated donor cells (A) or donor cells treated with TNF-α plus caspase inhibitor (C). Red, phalloidin stain for F-actin; blue, DAPI for cell nucleus; green (arrows), calcein from labeled donor MPs that had been taken up by recipient cells. Micrographs are representative of 3 separate experiments. MPs were isolated from different donor EC treatment groups, labeled with calcein-AM, and subsequently incubated with recipient ECs for 24 h. D: grouped mean green fluorescence values in recipient ECs after 24 h incubation with MPs from different donor ECs. x-Axis indicates different donor cell treatments. *P < 0.05 vs. control; #P < 0.05 between groups, n = 6.

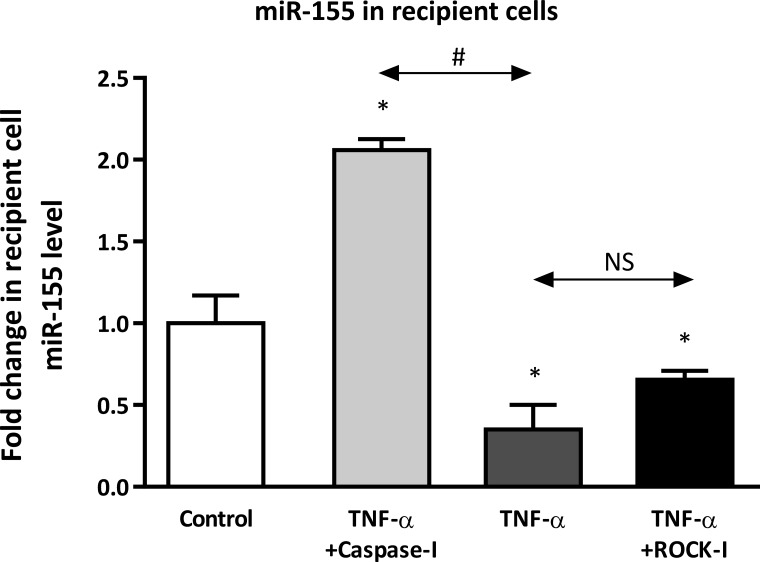

To determine whether donor MP uptake correlates with their ability to deliver their cargo, we assessed the transfer efficiency of miR-155 from control MPs and donor MPs produced in response to TNF-α alone, TNF-α plus caspase inhibitor, or TNF-α plus ROCK inhibitor. After 2 h incubation, relative miR-155 levels were determined in the recipient cells by qRT-PCR. At 2 h, changes in recipient cell miRNA levels were reflective of miRNA transfer from donor MPs rather than changes in miRNA production by recipient cells (57). We found that the transfer of miR-155 from MPs shed by TNF-α- or TNF-α plus ROCK inhibitor-treated donor HAECs was diminished compared with that of MPs from untreated donor ECs (Fig. 5), despite greater miR-155 content in donor MPs from TNF-α-treated cells (Fig. 1). As would be predicted based on calcein uptake, MPs produced by donor ECs treated with TNF-α plus caspase inhibitor were the most efficient in transferring miR-155 to recipient cells (∼2-fold increase vs. control, Fig. 5). Interestingly, the transfer of miR-126 and miR-21 from donor MPs released by cells treated with TNF-α plus caspase inhibitor was not as robust as the transfer of miR-155 (not shown). In fact, we did not observe significant transfer of miR-126 but did observe transfer of pre-miR-21, suggesting that miRNA transfer from donor MPs may be specific for both the miRNA and its mature or precursor form. Overall, these data indicate that MPs released in response to TNF-α or TNF-α plus ROCK inhibitor were impaired in their ability to serve as effective mediators of extracellular signaling, but MPs whose production was independent of caspase signaling could mediate cell-to-cell transfer of miRNA.

Fig. 5.

MPs from donor ECs treated with TNF-α or TNF-α plus ROCK inhibitor have diminished capacity to transfer miR-155 to recipient ECs, which is abrogated by caspase inhibitor. MPs were isolated from donor ECs that had been untreated (control) or treated with TNF-α with and without caspase and ROCK inhibitor for 24 h. Different groups of donor MPs were incubated with recipient ECs for 2 h. MiRNA-155 levels are expressed relative to recipient ECs incubated with MPs from control donor cells. x-Axis indicates different donor cell treatments. NS, not significant. *P < 0.05 vs. control; #P < 0.05 between groups, n = 3.

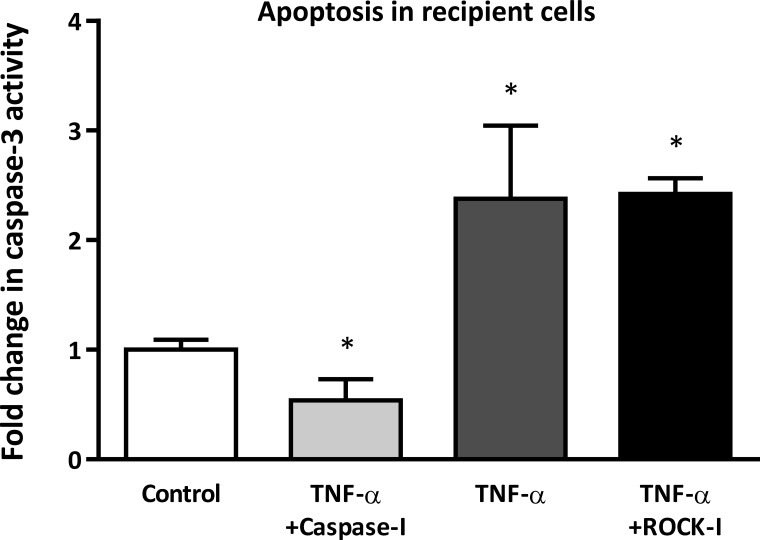

Effect of encapsulated extracellular miRNAs on the phenotype of recipient HAECs.

In vitro and in vivo, ECs demonstrate anti- or proatherogenic phenotypes in response to different biochemical (e.g., cytokines) and mechanical (e.g., shear stress) signals. For example, ECs that demonstrate an antiatherogenic phenotype are less proliferative and less migratory and have low apoptotic activity (60). To evaluate the impact of MP-mediated miRNA delivery on recipient cell phenotype, we assessed apoptosis in recipient HAECs. MiRNA-poor donor MPs from cells treated with TNF-α alone or TNF-α plus ROCK inhibitor increased apoptosis (as measured by caspase-3 activity) in recipient HAECs (Fig. 6) compared with control donor MPs. In contrast, miRNA-rich MPs released by donor ECs treated with TNF-α plus caspase inhibitor decreased apoptosis in recipient cells (Fig. 6). The effect of the miRNA-rich MPs was not due to MP-mediated transfer of caspase inhibitor from donor to recipient cells; MPs from HAECs treated with caspase inhibitor alone did not reduce TNF-α-induced apoptosis in recipient cells compared with control MPs. Together, these data indicate that miRNA-rich MPs, released in response to TNF-α but independent of caspase signaling, have a strong capacity to act as cell-to-cell communicators; these MPs are more readily taken up by recipient cells, are able to transfer their miRNA content, and promote an anti-atherogenic phenotype in recipient cells.

Fig. 6.

The effect of MPs from different donor EC treatment groups on recipient cell apoptosis. Recipient ECs were incubated with MPs from untreated donor cells (control), donor cells treated with TNF-α alone, or donor cells treated with TNF-α plus inhibitor (i.e., caspase-I, ROCK-I) for 24 h, and caspase-3 activity was measured in the recipient cells. Results are expressed relative to caspase-3 activity in recipient ECs incubated with MPs from control donor cells. *P < 0.05 vs. control; n = 5.

DISCUSSION

Clinically, endothelial MPs have been considered to be markers of inflammation and endothelial dysfunction. They have been shown to disturb vascular homeostasis and contribute to the progression of vascular disease by inducing EC activation, impairing vasorelaxation, promoting arterial stiffness, and enhancing coagulation (43, 50, 51, 53). However, the deleterious role of endothelial MPs has recently been challenged because of evidence that they can also promote cell survival, induce anti-inflammatory effects, and stimulate EC regeneration (14, 25, 28, 30, 31). Here, we found that, through different signaling pathways, the inflammatory stimulus TNF-α had a dual effect on the endothelial release of MPs. This dual effect resulted in the production of different groups of MPs that could be distinguished by their miRNA content and impact on recipient cells. TNF-α-induced miRNA-rich and miRNA-poor MPs were identified when caspase and RhoA/ROCK pathways were suppressed, respectively. Because these two populations of MPs had divergent effects on recipient cells, our findings provide insight into the conflicting data regarding the anti- and proatherogenic effects of endothelial MPs. Importantly, we believe that our data support the hypothesis that miRNAs encapsulated within MPs function as intercellular communicators that can modulate vascular homeostasis.

The current study focused on three miRNAs that are highly expressed in ECs at baseline but whose intracellular expression demonstrated a range of responses to TNF-α. The concentration of TNF-α used in these experiments (100 ng/ml) was on the higher end of concentrations previously reported for in vitro studies (10–100 ng/ml), and we considered that changes in intracellular and extracellular miRNA profiles that we observed might be due to the relatively high concentration of TNF-α. However, we saw similar changes in the intra- and extracellular miRNA profiles at TNF-α concentrations of 10, 30, and 60 ng/ml, suggesting that TNF-α signaling was saturated at 10 ng/ml. However, it is possible that we might see a dose-dependent effect of TNF-α at concentrations lower than 10 ng/ml.

TNF-α treatment increased the number of MPs produced by ECs. This phenomenon has been described previously and has been attributed to activation of different signaling pathways, including caspase, RhoA/ROCK, and the p38-MAPK pathways (9, 11, 36, 58). Here, we found that TNF-α also increased the release of MP-encapsulated miR-126, -21, and -155. The separation of the two effects of TNF-α was evident when cells were cotreated with different inhibitors of endothelial MP release. Caspase inhibition, while suppressing the effect of TNF-α on overall MP production, revealed the effect of TNF-α on release of MP-encapsulated miRNAs. ROCK inhibition suppressed the effect of TNF-α on miRNA export, but it did not affect TNF-α-induced MP production.

Changes in miRNA levels in cells treated with inhibitors were consistent with the role of caspase and ROCK pathways in miRNA export: intracellular miRNA levels increased after ROCK inhibition but not after caspase inhibition. Interestingly, in ECs treated with TNF-α alone, the relationship between miRNA export and intracellular levels was variable. Whereas the release of miR-126 and -21 did not appear to be dependent on their intracellular expression, increased intracellular expression of miR-155 was associated with increased export. This finding suggests the likelihood of additional mechanisms that are involved in miRNA export upstream to RhoA/ROCK signaling. These upstream mechanisms could account for the differences in the relationship between intra- and extracellular levels of specific miRNAs. Furthermore, there is at least one other pathway known to be involved in TNF-α-induced release of MPs from ECs that we did not examine (11). The p38-MAPK pathway has been described to produce proinflammatory MPs. It is possible that this pathway is also involved in regulation of intra- and extracellular miRNA levels, although, based on the inflammatory effects of the MPs produced by this pathway, we would expect these miRNAs to be proinflammatory.

We found that both precursor and mature forms of miRNA were exported into MPs in response to TNF-α; export of both forms was dependent on RhoA/ROCK signaling. The biological significance of this finding in terms of cell-to-cell communication is uncertain, although there is at least one report that extracellular miRNA-mediated target gene suppression in recipient cells requires transfer of pre-miRNA (6). Presumably, this is due to pre-miRNA having a greater capacity to be incorporated into the recipient cell's RNA-induced silencing complex. In the current study, among the three precursor miRNAs assessed, pre-miR-155 was released into MPs most consistently in response to TNF-α. Indeed, of the three miRNAs studied, miR-155 appeared to have the greatest capacity to be stably transfer to recipient cells. Whether miRNA transfer capacity from endothelial MPs is due to the relative abundance of pre-miRNA is the subject of ongoing studies.

Recipient cells treated with miRNA-rich MPs had decreased apoptotic activity, a finding that suggests these MPs transferred their miRNA content, which subsequently modulated recipient cell gene expression and phenotype. We propose that these phenotype changes are due, in part, to regulation of mRNAs that are targets of miR-155. In silico analysis indicated that miR-155 directly targets the 3′-untranslated region of caspase-3 mRNA, and this prediction was validated by Wang and colleagues (54). Subsequent studies using various breast carcinoma cell lines confirmed that miR-155 is a strong regulator of caspase-3 expression and thus cellular apoptosis (40, 62). However, regulation of recipient cell gene expressions by donor MP-encapsulated extracellular miRNA is likely more complex. In fact, we believe that the impact of miRNA-rich donor MPs on recipient cell phenotype is due to targeting of different mRNAs by multiple miRNAs. Our most recent data revealed that despite the relative enrichment of miR-126, -21, and their precursors in MPs from TNF-α plus caspase-inhibitor treated donor cells, no significant transfer of pre-miR-126 or miR-126 to recipient cells was observed, while pre-miR-21 was transferred from the donor MPs. These findings suggest another layer of complexity and stringent regulation of intercellular miRNA transfer through MP uptake. Further studies are under way in our laboratory focusing on a more comprehensive analysis of MP-encapsulated miRNAs from donor ECs that are effectively transferred to recipient cells and evaluating if the transferred miRNAs suppress known and predicted mRNA targets.

While our study focused on MP-mediated miRNA transfer, it is important to acknowledge that MPs may also contain other, biologically active substances such as mRNAs, proteins, cytokines, growth factors and enzymes (19, 42). These molecules, if transferred efficiently, may ultimately affect the phenotype and function of recipient cells. In the present study we specifically measured relative miRNA expression levels in the recipient cells following incubation with the MPs for 2 h. It is highly unlikely that any of the other potentially transferred molecules would interfere with our assay or cause significant change in gene expression profiles within this limited time frame.

We found that miRNA-rich MPs and miRNA-poor MPs differed in their ability to be taken up by recipient cells. The enhanced uptake of miRNA-rich MPs is consistent with their function as communicators of extracellular miRNA signals, but this study did not address the mechanism responsible for enhanced uptake of this group of MPs. In general, uptake of MPs by recipient cells is mediated by surface proteins, which facilitate targeting of MPs to specific recipient cell types. Endothelial MPs have many proteins on their surface such as platelet endothelial cell adhesion molecule-1 (CD31), endoglin (CD105), vascular endothelial cadherin (CD144), E-selectin (CD62E), P-selectin (CD62P), intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (CD54), vascular cell adhesion protein-1 (CD106), and integrins. Whether any of these proteins are involved in the uptake of miRNA-rich MPs is currently unknown. We suspect that, similar to the dependence of miRNA export on ROCK signaling in donor cells, the expression of proteins on the surface of miRNA-rich MP that mediate uptake is also dependent on ROCK signaling.

There are relatively few studies of extracellular miRNA signaling in endothelial biology, which is in contrast to the amount of information published about the biology and function of endothelial MPs. The current study enhances our understanding of the mechanisms responsible for miRNA export from ECs but also provides insight into the relationship between extracellular miRNA signaling and the diverse functions of endothelial MPs. Ultimately, this work could lead to innovative therapies whereby production of endogenous antiatherogenic MPs is enhanced or synthetic mimics of miRNA-rich vesicles could be engineered.

GRANTS

This work was supported by a VA Merit Award (I01 BX000704 to C. D. Searles) and a National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute R01 Award (HL-109559 to C. D. Searles).

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the author(s).

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Author contributions: T.A., M.W., and C.D.S. conception and design of research; T.A., K.R., M.W., and W.D.G. performed experiments; T.A., M.W., W.D.G., and C.D.S. analyzed data; T.A., M.W., W.D.G., and C.D.S. interpreted results of experiments; T.A. and W.D.G. prepared figures; T.A. drafted manuscript; T.A., K.R., M.W., W.D.G., and C.D.S. edited and revised manuscript; W.D.G. and C.D.S. approved final version of manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Arroyo JD, Chevillet JR, Kroh EM, Ruf IK, Pritchard CC, Gibson DF, Mitchell PS, Bennett CF, Pogosova-Agadjanyan EL, Stirewalt DL, Tait JF, Tewari M. Argonaute2 complexes carry a population of circulating microRNAs independent of vesicles in human plasma. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 108: 5003–5008, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bartel DP. MicroRNAs: genomics, biogenesis, mechanism, function. Cell 116: 281–297, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bouchareb R, Boulanger MC, Fournier D, Pibarot P, Messaddeq Y, Mathieu P. Mechanical strain induces the production of spheroid mineralized microparticles in the aortic valve through a RhoA/ROCK-dependent mechanism. J Mol Cell Cardiol 67: 49–59, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Camussi G, Deregibus MC, Bruno S, Cantaluppi V, Biancone L. Exosomes/microvesicles as a mechanism of cell-to-cell communication. Kidney Int 78: 838–848, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Caserta TM, Smith AN, Gultice AD, Reedy MA, Brown TL. Q-VD-OPh, a broad spectrum caspase inhibitor with potent antiapoptotic properties. Apoptosis 8: 345–352, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen TS, Lai RC, Lee MM, Choo AB, Lee CN, Lim SK. Mesenchymal stem cell secretes microparticles enriched in pre-microRNAs. Nucleic Acids Res 38: 215–224, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Choong ML, Yang HH, McNiece I. MicroRNA expression profiling during human cord blood-derived CD34 cell erythropoiesis. Exp Hematol 35: 551–564, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cocucci E, Racchetti G, Meldolesi J. Shedding microvesicles: artefacts no more. Trends Cell Biol 19: 43–51, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Combes V, Simon AC, Grau GE, Arnoux D, Camoin L, Sabatier F, Mutin M, Sanmarco M, Sampol J, Dignat-George F. In vitro generation of endothelial microparticles and possible prothrombotic activity in patients with lupus anticoagulant. J Clin Invest 104: 93–102, 1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cortez MA, Bueso-Ramos C, Ferdin J, Lopez-Berestein G, Sood AK, Calin GA. MicroRNAs in body fluids–the mix of hormones and biomarkers. Nat Rev Clin Oncol 8: 467–477, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Curtis AM, Wilkinson PF, Gui M, Gales TL, Hu E, Edelberg JM. p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase targets the production of proinflammatory endothelial microparticles. J Thromb Haemost 7: 701–709, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dennis C. The brave new world of RNA. Nature 418: 122–124, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Diehl P, Fricke A, Sander L, Stamm J, Bassler N, Htun N, Ziemann M, Helbing T, El-Osta A, Jowett JB, Peter K. Microparticles: major transport vehicles for distinct microRNAs in circulation. Cardiovasc Res 93: 633–644, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dignat-George F, Boulanger CM. The many faces of endothelial microparticles. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 31: 27–33, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.El-Hefnawy T, Raja S, Kelly L, Bigbee WL, Kirkwood JM, Luketich JD, Godfrey TE. Characterization of amplifiable, circulating RNA in plasma and its potential as a tool for cancer diagnostics. Clin Chem 50: 564–573, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Eldh M, Ekstrom K, Valadi H, Sjostrand M, Olsson B, Jernas M, Lotvall J. Exosomes communicate protective messages during oxidative stress; possible role of exosomal shuttle RNA. PLoS One 5: e15353, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Espiritu RP, Kearns AE, Vickers KS, Grant C, Ryu E, Wermers RA. Depression in primary hyperparathyroidism: prevalence and benefit of surgery. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 96: E1737–E1745, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Finn NA, Eapen D, Manocha P, Al Kassem H, Lassegue B, Ghasemzadeh N, Quyyumi A, Searles CD. Coronary heart disease alters intercellular communication by modifying microparticle-mediated microRNA transport. FEBS Lett 587: 3456–3463, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Garcia BA, Smalley DM, Cho H, Shabanowitz J, Ley K, Hunt DF. The platelet microparticle proteome. J Proteome Res 4: 1516–1521, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gilad S, Meiri E, Yogev Y, Benjamin S, Lebanony D, Yerushalmi N, Benjamin H, Kushnir M, Cholakh H, Melamed N, Bentwich Z, Hod M, Goren Y, Chajut A. Serum microRNAs are promising novel biomarkers. PLoS One 3: e3148, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Guduric-Fuchs J, O'Connor A, Camp B, O'Neill CL, Medina RJ, Simpson DA. Selective extracellular vesicle-mediated export of an overlapping set of microRNAs from multiple cell types. BMC Genomics 13: 357, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Guo H, Ingolia NT, Weissman JS, Bartel DP. Mammalian microRNAs predominantly act to decrease target mRNA levels. Nature 466: 835–840, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gupta SK, Bang C, Thum T. Circulating microRNAs as biomarkers and potential paracrine mediators of cardiovascular disease. Circ Cardiovasc Genet 3: 484–488, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gyorgy B, Szabo TG, Pasztoi M, Pal Z, Misjak P, Aradi B, Laszlo V, Pallinger E, Pap E, Kittel A, Nagy G, Falus A, Buzas EI. Membrane vesicles, current state-of-the-art: emerging role of extracellular vesicles. Cell Mol Life Sci 68: 2667–2688, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hasselmann DO, Rappl G, Tilgen W, Reinhold U. Extracellular tyrosinase mRNA within apoptotic bodies is protected from degradation in human serum. Clin Chem 47: 1488–1489, 2001. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hristov M, Erl W, Linder S, Weber PC. Apoptotic bodies from endothelial cells enhance the number and initiate the differentiation of human endothelial progenitor cells in vitro. Blood 104: 2761–2766, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hugel B, Martinez MC, Kunzelmann C, Freyssinet JM. Membrane microparticles: two sides of the coin. Physiology (Bethesda) 20: 22–27, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Iorio MV, Croce CM. MicroRNA dysregulation in cancer: diagnostics, monitoring and therapeutics. A comprehensive review. EMBO Mol Med 4: 143–159, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jansen F, Yang X, Hoelscher M, Cattelan A, Schmitz T, Proebsting S, Wenzel D, Vosen S, Franklin BS, Fleischmann BK, Nickenig G, Werner N. Endothelial microparticle-mediated transfer of MicroRNA-126 promotes vascular endothelial cell repair via SPRED1 and is abrogated in glucose-damaged endothelial microparticles. Circulation 128: 2026–2038, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jansen F, Yang X, Hoyer FF, Paul K, Heiermann N, Becher MU, Abu Hussein N, Kebschull M, Bedorf J, Franklin BS, Latz E, Nickenig G, Werner N. Endothelial microparticle uptake in target cells is annexin I/phosphatidylserine receptor dependent and prevents apoptosis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 32: 1925–1935, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jy W, Horstman LL, Ahn YS. Microparticle size and its relation to composition, functional activity, and clinical significance. Semin Thromb Hemost 36: 876–880, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kosaka N, Iguchi H, Ochiya T. Circulating microRNA in body fluid: a new potential biomarker for cancer diagnosis and prognosis. Cancer Sci 101: 2087–2092, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kosaka N, Iguchi H, Yoshioka Y, Takeshita F, Matsuki Y, Ochiya T. Secretory mechanisms and intercellular transfer of microRNAs in living cells. J Biol Chem 285: 17442–17452, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Krutzfeldt J, Poy MN, Stoffel M. Strategies to determine the biological function of microRNAs. Nat Genet 38, Suppl: S14–S19, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Liu Y, Huang W, Zhang R, Wu J, Li L, Tang Y. Proteomic analysis of TNF-alpha-activated endothelial cells and endothelial microparticles. Mol Med Rep 7: 318–326, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mitchell PS, Parkin RK, Kroh EM, Fritz BR, Wyman SK, Pogosova-Agadjanyan EL, Peterson A, Noteboom J, O'Briant KC, Allen A, Lin DW, Urban N, Drescher CW, Knudsen BS, Stirewalt DL, Gentleman R, Vessella RL, Nelson PS, Martin DB, Tewari M. Circulating microRNAs as stable blood-based markers for cancer detection. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 105: 10513–10518, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Montes M, Jaensson EA, Orozco AF, Lewis DE, Corry DB. A general method for bead-enhanced quantitation by flow cytometry. J Immunol Methods 317: 45–55, 2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ni CW, Qiu H, Jo H. MicroRNA-663 upregulated by oscillatory shear stress plays a role in inflammatory response of endothelial cells. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 300: H1762–H1769, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ovcharenko D, Kelnar K, Johnson C, Leng N, Brown D. Genome-scale microRNA and small interfering RNA screens identify small RNA modulators of TRAIL-induced apoptosis pathway. Cancer Res 67: 10782–10788, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Qin X, Wang X, Wang Y, Tang Z, Cui Q, Xi J, Li YS J, Chien S, Wang N. MicroRNA-19a mediates the suppressive effect of laminar flow on cyclin D1 expression in human umbilical vein endothelial cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 107: 3240–3244, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ratajczak J, Miekus K, Kucia M, Zhang J, Reca R, Dvorak P, Ratajczak MZ. Embryonic stem cell-derived microvesicles reprogram hematopoietic progenitors: evidence for horizontal transfer of mRNA and protein delivery. Leukemia 20: 847–856, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rautou PE, Vion AC, Amabile N, Chironi G, Simon A, Tedgui A, Boulanger CM. Microparticles, vascular function, atherothrombosis. Circ Res 109: 593–606, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ross R. Atherosclerosis–an inflammatory disease. N Engl J Med 340: 115–126, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ross R. The pathogenesis of atherosclerosis: a perspective for the 1990s. Nature 362: 801–809, 1993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Selbach M, Schwanhausser B, Thierfelder N, Fang Z, Khanin R, Rajewsky N. Widespread changes in protein synthesis induced by microRNAs. Nature 455: 58–63, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Shyy JY, Chien S. Role of integrins in endothelial mechanosensing of shear stress. Circ Res 91: 769–775, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Thum T. MicroRNA therapeutics in cardiovascular medicine. EMBO Mol Med 4: 3–14, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Valadi H, Ekstrom K, Bossios A, Sjostrand M, Lee JJ, Lotvall JO. Exosome-mediated transfer of mRNAs and microRNAs is a novel mechanism of genetic exchange between cells. Nat Cell Biol 9: 654–659, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.VanWijk MJ, Boer K, Berckmans RJ, Meijers JC, van der Post JA, Sturk A, VanBavel E, Nieuwland R. Enhanced coagulation activation in preeclampsia: the role of APC resistance, microparticles and other plasma constituents. Thromb Haemost 88: 415–420, 2002. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.VanWijk MJ, Nieuwland R, Boer K, van der Post JA, VanBavel E, Sturk A. Microparticle subpopulations are increased in preeclampsia: possible involvement in vascular dysfunction? Am J Obstet Gynecol 187: 450–456, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Vickers KC, Palmisano BT, Shoucri BM, Shamburek RD, Remaley AT. MicroRNAs are transported in plasma and delivered to recipient cells by high-density lipoproteins. Nat Cell Biol 13: 423–433, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Vion AC, Ramkhelawon B, Loyer X, Chironi G, Devue C, Loirand G, Tedgui A, Lehoux S, Boulanger CM. Shear stress regulates endothelial microparticle release. Circ Res 112: 1323–1333, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wang HQ, Yu XD, Liu ZH, Cheng X, Samartzis D, Jia LT, Wu SX, Huang J, Chen J, Luo ZJ. Deregulated miR-155 promotes Fas-mediated apoptosis in human intervertebral disc degeneration by targeting FADD and caspase-3. J Pathol 225: 232–242, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wang K, Zhang S, Weber J, Baxter D, Galas DJ. Export of microRNAs and microRNA-protective protein by mammalian cells. Nucleic Acids Res 38: 7248–7259, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wang KC, Garmire LX, Young A, Nguyen P, Trinh A, Subramaniam S, Wang NP, Shyy JYJ, Li YS, Chien S. Role of microRNA-23b in flow-regulation of Rb phosphorylation and endothelial cell growth. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 107: 3234–3239, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wang Y, Tao J, Yang Z, Tu C, Xu MG, Wang JM, Huang YJ. [Tumor necrosis factor-alpha induces release of endothelial microparticles from human endothelial cells]. Zhonghua xin xue guan bing za zhi 33: 1137–1140, 2005. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Weber M, Baker MB, Moore JP, Searles CD. MiR-21 is induced in endothelial cells by shear stress and modulates apoptosis and eNOS activity. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 393: 643–648, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Weber M, Kim S, Patterson N, Rooney K, Searles CD. MiRNA-155 targets myosin light chain kinase and modulates actin cytoskeleton organization in endothelial cells. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 306: H1192–H1203, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Zernecke A, Bidzhekov K, Noels H, Shagdarsuren E, Gan L, Denecke B, Hristov M, Koppel T, Jahantigh MN, Lutgens E, Wang S, Olson EN, Schober A, Weber C. Delivery of microRNA-126 by apoptotic bodies induces CXCL12-dependent vascular protection. Sci Signal 2: ra81, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Zheng SR, Guo GL, Zhai Q, Zou ZY, Zhang W. Effects of miR-155 antisense oligonucleotide on breast carcinoma cell line MDA-MB-157 and implanted tumors. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev 14: 2361–2366, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Zhou J, Wang KC, Wu W, Subramaniam S, Shyy JY, Chiu JJ, Li JY, Chien S. MicroRNA-21 targets peroxisome proliferators-activated receptor-alpha in an autoregulatory loop to modulate flow-induced endothelial inflammation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 108: 10355–10360, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Zhu H, Fan GC. Extracellular/circulating microRNAs and their potential role in cardiovascular disease. Am J Cardiovasc Dis 1: 138–149, 2011. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]