Abstract

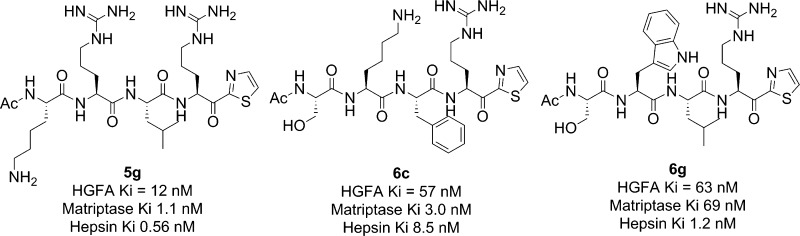

Hepatocyte growth factor activators (HGFA), matriptase, and hepsin are S1 family trypsin-like serine proteases. These proteases proteolytically cleave the single-chain zymogen precursors, pro-HGF (hepatocyte growth factor), and pro-MSP (macrophage stimulating protein) into active heterodimeric forms. HGF and MSP are activating ligands for the oncogenic receptor tyrosine kinases (RTKs), c-MET and RON, respectively. We have discovered the first substrate-based ketothiazole inhibitors of HGFA, matriptase and hepsin. The compounds were synthesized using a combination of solution and solid-phase peptide synthesis (SPPS). Compounds were tested for protease inhibition using a kinetic enzyme assay employing fluorogenic peptide substrates. Highlighted HGFA inhibitors are Ac-KRLR-kt (5g), Ac-SKFR-kt (6c), and Ac-SWLR-kt (6g) with Kis = 12, 57, and 63 nM, respectively. We demonstrated that inhibitors block the conversion of native pro-HGF and pro-MSP by HGFA with equivalent potency. Finally, we show that inhibition causes a dose-dependent decrease of c-MET signaling in MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells. This preliminary investigation provides evidence that HGFA is a promising therapeutic target in breast cancer and other tumor types driven by c-MET and RON.

Keywords: serine protease, peptidomimetic, breast cancer, HGFA, matriptase, hepsin, HGF, MSP, c-MET, RON, growth factor, kinase, cell signaling, ketothiazole, solid-phase peptide synthesis, inhibitor

Increased activation and signaling of the oncogenic receptor tyrosine kinases (RTKs) c-MET and RON1 triggers many downstream phenotypic changes necessary for tumor metastasis2−4 including cell migration, invasion, proliferation, differentiation, survival, and angiogenesis. Targeting c-MET and RON kinase cell signaling pathways with RTK inhibitors5 is a well-developed strategy for treating metastatic cancer. In fact, coexpression of c-MET and RON has been recently identified in several tumor types including bladder, ovarian, and node-negative breast cancer.6−15 Crosstalk between c-MET and RON16 has been shown in some cases to result from the formation of c-MET/RON heterodimers,17 which is a mechanism tumors can utilize to promote a metastatic phenotype. Many potent kinase inhibitors of c-MET and some for RON have been developed, but most reported inhibitors are multitargeted and lack sufficient selectivity. With the exception of antibodies to c-MET18 and HGF,19,20 only limited studies have explored nonkinase extracellular targets upstream of c-MET or RON kinase receptor activation. One such target is hepatocyte growth factor activator (HGFA) that has highly upregulated function in a number of different tumor types both in patient-derived cell lines21 and in patient tissue samples most widely studied so far in breast cancer.

HGFA is a member of the S1 trypsin-like serine protease family exemplified by thrombin and the coagulation proteases but most structurally similar to Factor XIIa.22 Characteristic of other coagulation cascade proteases, HGFA circulates in plasma as an inactive form and pro-HGFA at relatively high levels (40 nM). pro-HGFA is produced by the liver and is activated by other serine proteases in the plasma including thrombin23 and kallikrein-1 related (KLK) peptidases.24 Its biological function is a proteolytic process and activates the c-MET and RON tyrosine kinase ligands, HGF (hepatocyte growth factor), and MSP (macrophage stimulating protein), respectively, primarily in injured tissues.25 HGF and MSP are members of the plasminogen family of proteins that are secreted as inactive single-chain zymogens, pro-HGF, and pro-MSP. The latter are the only two known HGFA substrates and are enzymatically hydrolyzed at the Arg494-Val495 and the Arg483-Val484 peptide bonds, respectively, by either activated HGFA26 or the cell-surface serine proteases matriptase27 and hepsin.28 Subsequent to enzymatic hydrolysis, the α-chain N-terminal fragment and β-chain C-terminal fragments of the processed growth factor spontaneously form a two-chain disulfide bridged heterodimer capable of binding to the extracellular domain of its respective receptor tyrosine kinase and causing its activation. The processing of HGF and MSP is thus critical for cell signaling through c-MET and RON.

Matriptase and hepsin are type II transmembrane serine proteases (TTSPs)29,30 present on endothelial cells. They are also members of the S1 family of serine peptidases and are upregulated and aberrantly expressed in invasive tumors. The proteolytic activity of all three proteases, matriptase, hepsin, and HGFA, is regulated by the polypeptide inhibitors HAI-1 and HAI-2, which inhibit all three proteases at low nanomolar concentration. Imbalance of normal HGFA, HAI-1, and HAI-2 expression has been demonstrated to lead to invasive phenotypes in breast and other types of cancer.31 Only limited studies have been pursued evaluating the individual roles that HGFA, matriptase, and hepsin play in cancer development or progression, and their importance in different types of cancer32 is not yet understood. Inhibitors of HGFA, matriptase, or hepsin act in the tumor pericellular microenvironment to block cell signaling by preventing activation of both c-MET and RON receptor tyrosine kinases. Thus, potent and selective inhibitors of HGFA are powerful chemical tools for studying the role and regulation of cell signaling by serine proteases and are potential therapeutics for the treatment and prevention of metastatic cancer driven by c-MET and RON cell signaling.

Potent benzamidine-based inhibitors of matriptase33 and weak inhibitors of hepsin identified through HTS34 have been reported. There are several reports of inhibitory antibodies against HGFA,35 matriptase, and hepsin, but there are no synthetic peptide-based or small molecule inhibitors of HGFA or hepsin. In this preliminary communication, we report on the design and synthesis of the first small molecular weight synthetic inhibitors of HGFA and hepsin. These inhibitors cause a dose-dependent decrease in the catalytic processing of pro-HGF and pro-MSP by HGFA and phosphorylation of c-MET in MDA-MB-231 invasive breast cancer cells.

Electrophilic ketones,36 alpha-ketoamides, and aldehydes are typical warheads used as mechanism-based inhibitors of serine proteases, which engage the catalytic active-site serine by covalent but reversible attachment. The warhead is attached at the P1 position of a peptide substrate and P1–P1′ is the site of amide bond hydrolysis indicating the P1 N-terminal amino and the P1′ C-terminal amino acid of the substrate. The covalent attachment closely mimics the tetrahedral intermediate inherent to the enzyme mechanism and is stabilized by the classical oxyanion hole in the active site of serine proteases. When HGFA was discovered and classified as a serine protease in 1992,37 it was reported that Leupeptin showed only a weak 40% inhibition of HGFA at 20 μM, and TLCK, an irreversible inhibitor, showed only 28% inhibition of HGFA at 2 mM. Furthermore, benzamidine, ordinarily an inhibitor of serine proteases at 1 mM, only showed 14% inhibition at a concentration 10-fold higher. These data suggest HGFA is unique relative to other S1 proteases and might have a different inhibitor profile and substrate specificity. Therefore, we followed a systematic approach in our design of inhibitors based on the sequences of the only known HGFA substrates, pro-HGF and pro-MSP.

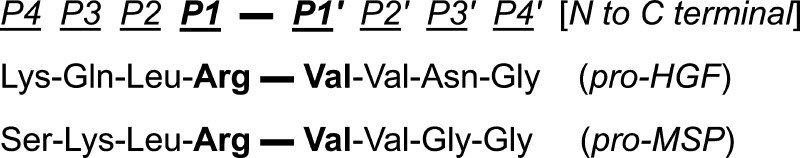

In order to rationally design mechanism-based inhibitors of HGFA, we synthesized tetrapeptide ketothiazole (KT) analogues based on the N-terminal portion (P4–P1) of the pro-HGF and pro-MSP substrate cleavage sites (Figure 1). Shown in Scheme 1, protected tripeptide acids were constructed using solid phase peptide synthesis from 2-Cl trityl resin (1). Reaction of 2 or 3 tripeptide acids with Mtr-protected Arg-KT (4) (Scheme 2)36,38 and HATU in solution gave Ac-Lys(Boc)-Gln(Trt)-Leu-Arg(Mtr)-kt and Ac-Ser(tBu)-Lys(Boc)-Leu-Arg(Mtr)-kt. Deprotection with TFA/H2O/thioanisole and purification by reversed phase HPLC gave the pro-HGF and pro-MSP substrate mimetics, Ac-Lys-Gln-Leu-Arg-kt (5) and Ac-Ser-Lys-Leu-Arg-kt (6), respectively, in good overall yield. We tested previously reported inhibitors27 and our new ketothiazoles, 5 and 6, in an HGFA enzymatic assay using the fluorogenic substrate Boc-QLR-AMC with a recombinant form of the HGFA serine protease domain (Supporting Information). The pro-HGF and pro-MSP tetrapeptides 5 and 6 showed Kis of 53 and 81 nM, respectively. We demonstrated that inhibitor 5 was competitive with the substrate at the active-site and that the inhibition is reversible (Supporting Information), consistent with other reported ketone-based serine protease inhibitors.38

Figure 1.

P4–P4′ polypeptide sequences of pro-HGF and pro-MSP highlighting cleavage site.

Scheme 1. Synthesis of Pro-HGF and Pro-MSP P4–P1 Tetrapeptide Ketothiazoles.

Scheme 2. Synthesis of Protected Arginine Ketothiazole.

We confirmed in our assay that irreversible inhibitor TLCK showed no inhibition up to 100 μM and that Nafamostat had a Ki consistent with the single-point assay reported in 1992.39 In order to understand substrate binding pocket specificity and develop structure–activity relationships (SAR), we rationally designed two focused libraries of peptides, one directed on changes to the pro-HGF peptide and the other on pro-MSP.

Using the X-ray structure of Ac-KQLR-CMK (PDB code: 2WUC)35 and a computational model of the pro-HGF peptide, Lys-Gln-Leu-Arg-Val-Val-Asn-Gly, spanning the S4–S4′ pockets bound to the active site of HGFA (PDB code: 1YCO),40 we noted the S4 and S3 pockets are large and not well occupied by the peptide side chains Lys and Gln. In the corresponding pro-MSP peptide the P4 position is a Ser and the P3 a Lys (Figure 2). Our data from the P4–P1 ketothiazoles 5 and 6 suggest that the Ser in P4 of the pro-MSP peptide decreases substrate binding relative to pro-HGF. Therefore, we hypothesized that larger side chains in P4 and P3 should lead to enhancements in potency due to increased hydrophobic interactions with these pockets of the enzyme. We also noticed that conserved residue Trp618 (Trp215 in chymotrypsin numbering) is forming part of the S4 pocket so Trp was one of the P4 residues chosen for our initial set of compounds. We found that replacement of Lys with Trp in P4 of Ac-KQLR-kt (5) had no effect on potency (5b), while replacement of Ser of Ac-SKLR-kt (6) in P4 with Trp leads to a 2-fold increase in activity (6b) (Table 1). However, changing the Lys of 5 to Ser (5f) decreased activity 3-fold. Also forming part of the S4 pocket is Asp576, and we surmised that replacement of Lys with Arg would not only fill the pocket better but would also lead to improved interaction with the side chain of Asp576. This substitution with Arg resulted in a 4-fold enhancement of potency seen with Ac-RKLR-kt (6h). This small set of compounds demonstrates that the S4 pocket of HGFA does prefer larger side chains but does not have a preference for a basic residue at P4 like has been demonstrated for matriptase42 and hepsin.41 Although the S3 site appears large, it is also more solvent exposed, and forming part of this pocket is a salt bridge between Glu545 and Arg624. The P3 amino acid in pro-MSP is Lys suggesting a possible interaction with the side chain of Glu545. We proposed that a His or Arg side chain might be able to interact in a similar fashion but also more effectively interfere with the Arg624. We found that replacement of P3 with His resulted in similar inhibition of HGFA for the pro-HGF analogue (5a) but a 4-fold decrease in activity for the pro-MSP analogue (6a). However, the corresponding Arg replacements did give enhanced activity as predicted and exemplified by 5g (Ki = 12 nM) and 6e (Ki = 29 nM). Compound 5d with Phe on the P3 position also increased HGFA inhibition with a Ki = 41 nM. We also found substitution of the P2 Leu with Phe in the pro-HGF peptide (5c) or the pro-MSP peptide (6c) was tolerated with no change in activity. Modifying the P2 position has potential for increasing selectivity against matriptase, which prefers small hydrophobic side chains41 since the S2 pocket is attenuated compared to HGFA. SAR from this study demonstrates that HGFA prefers Arg or Trp in the S4 and S3 pockets, and cooperativity between these two pockets suggests that the best potency results when one of the side chains is basic such as Ac-WRLR-kt (5h, Ki = 21 nM) and Ac-WKLR-kt (6b, Ki = 56 nM). However, good activity is still achieved in the absence of a basic side chain when either the P4 or the P3 residue is Trp as in Ac-WQLR-kt (5b, Ki = 65 nM) and Ac-SWLR-kt (6g, Ki = 63 nM).

Figure 2.

Model of pro-HGF P4–P4′ peptide (cyan) bound to HGFA (PDB code: 1YCO; white),40 matriptase (PDB code: 2GV7; orange),33 and hepsin (PDB code: 1Z8G; blue).41

Table 1. HGFA, Matriptase and Hepsin Inhibitory Activity of Pro-HGF and Pro-MSP Substrate-Based Inhibitors.

| structure | HGFA Ki (nM) | matriptase Ki (nM) | hepsin Ki (nM) |

|---|---|---|---|

| nafamostat | 25 | 0.02 | 0.53 |

| leupeptin (Ac-LLR-H) | 188 | 696 | 61 |

| Ac-KQLR-kt(pro-HGF; 5) | 53 | 0.92 | 0.22 |

| Ac–KHLR-kt (5a) | 96 | 22 | 0.41 |

| Ac-WQLR-kt (5b) | 65 | 32 | 0.21 |

| Ac-KQFR-kt (5c) | 58 | 0.69 | 0.58 |

| Ac–KFLR-kt (5d) | 80 | 15 | 2.1 |

| Ac-RQLR-kt (5e) | 60 | 0.32 | 0.28 |

| Ac-SQLR-kt (5f) | 182 | 9.2 | 0.34 |

| Ac–KRLR-kt (5g) | 12 | 1.1 | 0.57 |

| Ac-WRLR-kt (5h) | 21 | 5.5 | 0.21 |

| Ac-SKLR-kt(pro-MSP; 6) | 81 | 58 | 1.2 |

| Ac–SHLR-kt (6a) | 332 | 104 | 0.60 |

| Ac-WKLR-kt (6b) | 56 | 8.6 | 0.55 |

| Ac-SKFR-kt (6c) | 57 | 3.0 | 8.5 |

| Ac-NKLR-kt (6d) | 79 | 12 | 1.4 |

| Ac–SRLR-kt (6e) | 24 | 5.8 | 0.68 |

| Ac-TKLR-kt (6f) | 103 | 8.7 | 0.61 |

| Ac–SWLR-kt (6g) | 63 | 69 | 1.2 |

| Ac-RKLR-kt (6h) | 17 | 0.83 | 0.47 |

Having this data in hand, we wanted to determine the selectivity profile of the inhibitors relative to matriptase and hepsin. We developed a similar assay using Boc-QAR-AMC as the substrate. Shown in Table 1, the majority of compounds evaluated are more selective for matriptase and hepsin; most pronounced with hepsin where some inhibitors have Kis < 1 nM. There are several compounds that are equipotent for HGFA compared to matriptase but leupeptin is 3-fold selective for HGFA over matriptase and only 3-fold favoring hepsin. The pro-HGF peptide (5) is 200-fold more potent for hepsin and 50-fold for matriptase, while the pro-MSP peptide (6) is only slightly more potent for matriptase and 70-fold potent for hepsin versus HGFA. Ac-SWLR-kt (6g) is equipotent for both HGFA and matriptase with a Ki = 66 nM but Ki = 1.2 nM for hepsin. Compound 6g, Ac-SKFR-kt (6c), Ac-KFLR-kt (5d), and Ac-SRLR-kt (6e) are promising leads for obtaining HGFA selectivity over both hepsin and matriptase.

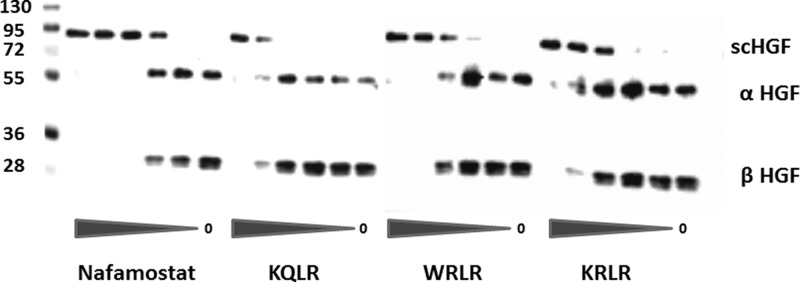

We employed a biochemical assay in order to demonstrate that inhibitors can block the proteolytic activation of the endogenous growth factors, pro-HGF and pro-MSP, by HGFA in a dose-dependent manner. In order to determine efficiency of our recombinant HGFA we performed a concentration response of HGFA using a fixed concentration of pro-HGF and pro-MSP. Since both the single chain inactive pro-HGF or pro-MSP and the active heterodimers have the same molecular weight, SDS gels were developed under reducing conditions. Lanes with pro-HGF (Figure 3) and pro-MSP (Figure 4) contain one band at 90 and 75 kDa, respectively, whereas activated HGF and MSP appear as two bands as the 60 kDa α-chain and 30 kDa β-chain in HGF and at 50 and 25 kDa for MSP (note: MSP Ab only recognizes the α-chain). Shown in Figure 4, we found that nafamostat and the three inhibitors 5, 5h, and 5g all showed a dose-dependent inhibition of pro-HGF activation with similar EC50 values in direct correlation with those found from the HGFA enzyme assay. These inhibitors in addition to 6e also all show dose-dependent inhibition of pro-MSP proteolysis by HGFA as shown in Figure 4. While it is difficult to quantitate the level of MSP activation since the pro-MSP has some active two-chain MSP present, the EC50 values correlate with the level of potency seen in the enzyme assay. These results show the inhibitors inhibit the processing of both known protein substrates of HGFA.

Figure 3.

Inhibition of HGFA-mediated scHGF (pro-HGF) cleavage by inhibitors. Immunoblot of scHGF cleavage reactions: Pro-HGF (30 ng) was cleaved with 1 nM HGFA in the presence of inhibitors (5-fold dilutions from 12.5 μM).

Figure 4.

Inhibition of HGFA-mediated scMSP (pro-MSP) cleavage by inhibitors. Immunoblot of scMSP cleavage reactions: Pro-MSP (50 ng) was cleaved with 10 nM HGFA in the presence of inhibitors (5-fold dilutions from 12.5 μM).

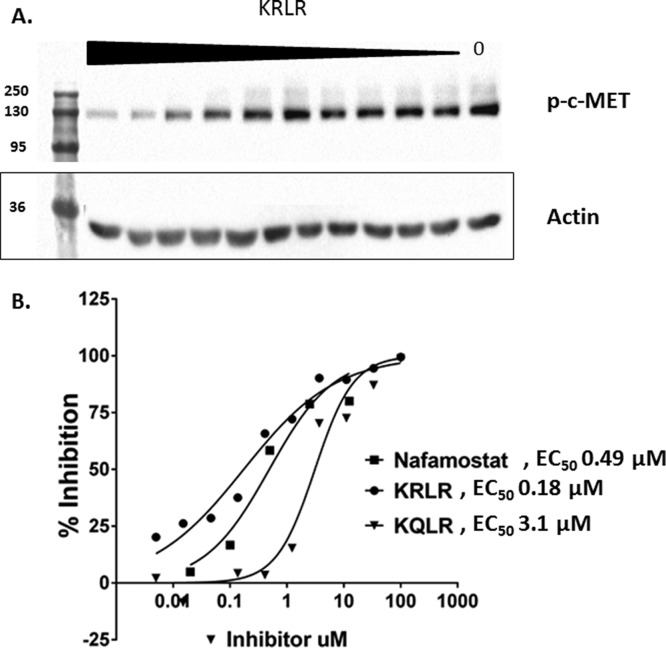

Since we demonstrated robust and potent inhibition of pro-HGF processing by HGFA inhibitors, we next wanted to show that the inhibition would have effects on cell signaling through c-MET kinase. Therefore, we developed a phosphorylation assay using the invasive breast cancer cell line, MDA-MB-231. This cell line has high expression of c-MET and pro-HGFA but not pro-HGF. We incubated HGFA with inhibitor, followed by the addition of pro-HGF in cell culture with the MBA-MB-231 cells. Shown in Figure 5, several inhibitors were effective at decreasing c-MET phosphorylation in a dose-dependent manner. Thus, inhibitors of HGFA show promise as nonkinase inhibitors of HGF-mediated c-MET kinase signaling in cancer. The most potent compound 5g had an EC50 of 180 nM.

Figure 5.

MDA-MB-231 c-MET phosphorylation of cells treated with pro-HGF/HGFA reactions (3-fold dilutions of inhibitors starting at 100 μM). (A) Immunoblot of pY1234/135 c-MET. (B) Percent inhibition of c-MET phosphorylation.

In conclusion, we have rationally designed the first peptidomimetic inhibitors of HGFA serine protease. We utilized the sequence and predicted binding conformations of the pro-HGF and pro-MSP protein substrates of HGFA to discover a series of potent mechanism-based inhibitors. We have developed an initial understanding of structure–activity relationships (SAR) for HGFA, matriptase, and hepsin by evaluating tetrapeptide ketothiazole libraries. The data from our inhibitors suggests that HGFA has an unusual inhibitor profile relative to other trypsin-like serine proteases. HGFA prefers one basic side chain in either the S3 or S4 subsites for maximal binding, but interestingly, substitution of Arg or Lys with Trp is also well-tolerated. We discovered that Ser or Trp in the P4 and Phe in the P2 position of the ketothiazole inhibitor help improve relative selectivity for HGFA over matriptase and hepsin. All inhibitors cause a dose-dependent decrease in pro-HGF and pro-MSP native substrate proteolysis and activation by HGFA. Furthermore, inhibitors causes decreased c-MET phosphorylation in MDA-MB-231 invasive breast cancer cells. This is the first demonstration that a small molecule inhibitor of HGFA can block c-MET phosphorylation and cancer cell signaling. The results from this study enable the rational design of more potent and selective inhibitors of HGFA, which can be used to study the role of these proteases in cancer and developed further as new therapeutics for metastatic cancer. We are currently pursuing structural biology data of HGFA-inhibitor binding through X-ray crystallography and are testing inhibitors for their effects on RON kinase phosphorylation and other phenotypic effects, which will be reported in due course.

Acknowledgments

We thank Ron Bose for his help in developing the c-MET phosphorylation cell assay and Charles Craik for Matriptase and advice. We thank Tom Ellenberger and Enrico Di Cera for their help in protein expression and purification. We also thank Linda Pike for MCF7 and MDA-MB-231 cells.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- HGF

hepatocyte growth factor

- MSP

macrophage stimulating protein

- HGFA

hepatocyte growth factor activator

- kt

ketothiazole

- AMC

7-amino-4-methylcoumarin

- TLCK

N-α-tosyl-l-lysine chloromethyl ketone

- PNGB

4-nitrophenyl 4-guanidinobenzoate

- Cha

cyclohexylalanine

- RTK

receptor tyrosine kinase

- SPPS

solid-phase peptide synthesis

Supporting Information Available

Experimental details on the synthesis, purification, and characterization of Boc-QLR-AMC, 5, 6, 5a–5h, and 6a–6h are provided. Experimental details on the expression and purification of HGFA are included. Protocols and data analysis for the enzyme, biochemical, and phosphorylation assays are also supplied. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

Author Present Address

§ Department of Chemistry, University of Arkansas, Little Rock, Arkansas 72701, United States.

Author Contributions

The manuscript was written through contributions of all authors. All authors have given approval to the final version of the manuscript.

Funding was provided by Susan G. Komen Career Catalyst Grant CCR12222792.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Gaudino G.; Follenzi A.; Naldini L.; Collesi C.; Santoro M.; Gallo K. A.; Godowski P. J.; Comoglio P. M. RON is a heterodimeric tyrosine kinase receptor activated by the HGF homologue MSP. EMBO J. 1994, 13153524–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Organ S. L.; Tsao M. S. An overview of the c-MET signaling pathway. Ther. Adv. Med. Oncol. 2011, 31 SupplS7–S19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang M. H.; Wang D.; Chen Y. Q. Oncogenic and invasive potentials of human macrophage-stimulating protein receptor, the RON receptor tyrosine kinase. Carcinogenesis 2003, 2481291–300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benvenuti S.; Comoglio P. M. The MET receptor tyrosine kinase in invasion and metastasis. J. Cell Physiol. 2007, 2132316–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qian F.; Engst S.; Yamaguchi K.; Yu P.; Won K. A.; Mock L.; Lou T.; Tan J.; Li C.; Tam D.; Lougheed J.; Yakes F. M.; Bentzien F.; Xu W.; Zaks T.; Wooster R.; Greshock J.; Joly A. H. Inhibition of tumor cell growth, invasion, and metastasis by EXEL-2880 (XL880, GSK1363089), a novel inhibitor of HGF and VEGF receptor tyrosine kinases. Cancer Res. 2009, 69208009–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seiwert T. Y.; Jagadeeswaran R.; Faoro L.; Janamanchi V.; Nallasura V.; El Dinali M.; Yala S.; Kanteti R.; Cohen E. E.; Lingen M. W.; Martin L.; Krishnaswamy S.; Klein-Szanto A.; Christensen J. G.; Vokes E. E.; Salgia R. The MET receptor tyrosine kinase is a potential novel therapeutic target for head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Cancer Res. 2009, 6973021–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catenacci D. V. T.; Cervantes G.; Yala S.; Nelson E. A.; El-Hashani E.; Kanteti R.; El Dinali M.; Hasina R.; Bragelmann J.; Seiwert T.; Sanicola M.; Henderson L.; Grushko T. A.; Olopade O.; Karrison T.; Bang Y. J.; Kim W. H.; Tretiakova M.; Vokes E.; Frank D. A.; Kindler H. L.; Huet H.; Salgia R. RON (MST1R) is a novel prognostic marker and therapeutic target for gastroesophageal adenocarcinoma. Cancer Biol. Ther. 2011, 1219–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsu P. Y.; Liu H. S.; Cheng H. L.; Tzai T. S.; Guo H. R.; Ho C. L.; Chow N. H. Collaboration of RON and epidermal growth factor receptor in human bladder carcinogenesis. J. Urol. 2006, 17652262–2267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee W. Y.; Chen H. H. W.; Chow N. H.; Su W. C.; Lin P. W.; Guo H. R. Prognostic significance of co-expression of RON and MET receptors in node-negative breast cancer patients. Clin. Cancer Res. 2005, 1162222–2228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng H. L.; Liu H. S.; Lin Y. J.; Chen H. H. W.; Hsu P. Y.; Chang T. Y.; Ho C. L.; Tzai T. S.; Chow N. H. Co-expression of RON and MET is a prognostic indicator for patients with transitional-cell carcinoma of the bladder. Br. J. Cancer 2005, 92101906–1914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Q.; Seol D. W.; Carr B.; Zarnegar R. Co-expression and regulation of Met and Ron proto-oncogenes in human hepatocellular carcinoma tissues and cell lines. Hepatology 1997, 26159–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maggiora P.; Lorenzato A.; Fracchioli S.; Costa B.; Castagnaro M.; Arisio R.; Katsaros D.; Massobrio M.; Comoglio P. M.; Flavia Di Renzo M. The RON and MET oncogenes are co-expressed in human ovarian carcinomas and cooperate in activating invasiveness. Exp. Cell Res. 2003, 2882382–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koh Y. W.; Hwang H. S.; Jung S. J.; Park C.; Yoon D. H.; Suh C.; Huh J. Receptor tyrosine kinases MET and RON as prognostic factors in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma patients receiving R-CHOP. Cancer Sci. 2013, 10491245–1251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee C. T.; Chow N. H.; Su P. F.; Lin S. C.; Lin P. C.; Lee J. C. The prognostic significance of RON and MET receptor coexpression in patients with colorectal cancer. Dis. Colon Rectum 2008, 5181268–1274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Comperat E.; Roupret M.; Chartier-Kastler E.; Bitker M. O.; Richard F.; Camparo P.; Capron F.; Cussenot O. Prognostic value of MET, RON and histoprognostic factors for urothelial carcinoma in the upper urinary tract. J. Urol. 2008, 1793868–872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Follenzi A.; Bakovic S.; Gual P.; Stella M. C.; Longati P.; Comoglio P. M. Cross-talk between the proto-oncogenes Met and Ron. Oncogene 2000, 19273041–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCleese J. K.; Bear M. D.; Kulp S. K.; Mazcko C.; Khanna C.; London C. A. Met interacts with EGFR and Ron in canine osteosarcoma. Vet. Comp. Oncol. 2013, 112124–139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oh Y. M.; Song Y. J.; Lee S. B.; Jeong Y.; Kim B.; Kim G. W.; Kim K. E.; Lee J. M.; Cho M. Y.; Choi J.; Nam D. H.; Song P. H.; Cheong K. H.; Kim K. A. A new anti-c-Met antibody selected by a mechanism-based dual-screening method: therapeutic potential in cancer. Mol. Cells 2012, 346523–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoffski P.; Garcia J. A.; Stadler W. M.; Gil T.; Jonasch E.; Tagawa S. T.; Smitt M.; Yang X.; Oliner K. S.; Anderson A.; Zhu M.; Kabbinavar F. A phase II study of the efficacy and safety of AMG 102 in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma. BJU Int. 2011, 1085679–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tabernero J.; Elez M. E.; Herranz M.; Rico I.; Prudkin L.; Andreu J.; Mateos J.; Carreras M. J.; Han M.; Gifford J.; Credi M.; Yin W.; Agarwal S.; Komarnitsky P.; Baselga J. A pharmacodynamic/pharmacokinetic study of ficlatuzumab in patients with advanced solid tumors and liver metastases. Clin. Cancer Res. 2014, 20102793–804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parr C.; Jiang W. G. Expression of hepatocyte growth factor/scatter factor, its activator, inhibitors and the c-Met receptor in human cancer cells. Int. J. Oncol. 2001, 194857–863. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyazawa K.; Shimomura T.; Kitamura A.; Kondo J.; Morimoto Y.; Kitamura N. Molecular cloning and sequence-analysis of the cDNA for a human tissue serine protease responsible for activation of hepatocyte growth-factor- Structural similarity of the protease precursor to blood coagulation factor-XII. J. Biol. Chem. 1993, 2681410024–10028. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimomura T.; Kondo J.; Ochiai M.; Naka D.; Miyazawa K.; Morimoto Y.; Kitamura N. Activation of the zymogen of hepatocyte growth-factor activator by thrombin. J. Biol. Chem. 1993, 2683022927–22932. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mukai S.; Fukushima T.; Naka D.; Tanaka H.; Osada Y.; Kataoka H. Activation of hepatocyte growth factor activator zymogen (pro-HGFA) by human kallikrein 1-related peptidases. FEBS J. 2008, 27551003–1017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyazawa K.; Shimomura T.; Kitamura N. Activation of hepatocyte growth factor in the injured tissues is mediated by hepatocyte growth factor activator. J. Biol. Chem. 1996, 27173615–3618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimomura T.; Miyazawa K.; Komiyama Y.; Hiraoka H.; Naka D.; Morimoto Y.; Kitamura N. Activation of hepatocyte growth factor by two homologous proteases, blood-coagulation factor XIIa and hepatocyte growth factor activator. Eur. J. Biochem. 1995, 2291257–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owen K. A.; Qiu D.; Alves J.; Schumacher A. M.; Kilpatrick L. M.; Li J.; Harris J. L.; Ellis V. Pericellular activation of hepatocyte growth factor by the transmembrane serine proteases matriptase and hepsin, but not by the membrane-associated protease uPA. Biochem. J. 2010, 4262219–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ganesan R.; Kolumam G. A.; Lin S. J.; Xie M. H.; Santell L.; Wu T. D.; Lazarus R. A.; Chaudhuri A.; Kirchhofer D. Proteolytic activation of pro-macrophage-stimulating protein by hepsin. Mol. Cancer Res. 2011, 991175–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- List K. Matriptase: a culprit in cancer?. Future Oncol. 2009, 5197–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bugge T. H.; Antalis T. M.; Wu Q. Y. Type II Transmembrane Serine Proteases. J. Biol. Chem. 2009, 2843523177–23181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kataoka H.; Miyata S.; Uchinokura S.; Itoh H. Roles of hepatocyte growth factor (HGF) activator and HGF activator inhibitor in the pericellular activation of HGF/scatter factor. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2003, 222–3223–236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parr C.; Sanders A. J.; Jiang W. G. Hepatocyte growth factor activation inhibitors: therapeutic potential in cancer. Anticancer Agents Med. Chem. 2010, 10147–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinmetzer T.; Schweinitz A.; Sturzebecher A.; Donnecke D.; Uhland K.; Schuster O.; Steinmetzer P.; Muller F.; Friedrich R.; Than M. E.; Bode W.; Sturzebecher J. Secondary amides of sulfonylated 3-amidinophenylalanine. New potent and selective inhibitors of matriptase. J. Med. Chem. 2006, 49144116–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chevillet J. R.; Park G. J.; Bedalov A.; Simon J. A.; Vasioukhin V. I. Identification and characterization of small-molecule inhibitors of hepsin. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2008, 7103343–3351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ganesan R.; Eigenbrot C.; Wu Y.; Liang W. C.; Shia S.; Lipari M. T.; Kirchhofer D. Unraveling the allosteric mechanism of serine protease inhibition by an antibody. Structure 2009, 17121614–1624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin J.; Deng H.; Jin L.; Pandey P.; Quinn J.; Cantin S.; Rynkiewicz M. J.; Gorga J. C.; Bibbins F.; Celatka C. A.; Nagafuji P.; Bannister T. D.; Meyers H. V.; Babine R. E.; Hayward N. J.; Weaver D.; Benjamin H.; Stassen F.; Abdel-Meguid S. S.; Strickler J. E. Design, synthesis, and biological evaluation of peptidomimetic inhibitors of factor XIa as novel anticoagulants. J. Med. Chem. 2006, 49267781–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimomura T.; Ochiai M.; Kondo J.; Morimoto Y. A novel protease obtained from FBS-containing culture supernatant, that processes single chain form hepatocyte growth factor to two chain form in serum-free culture. Cytotechnology 1992, 83219–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colombo E.; Desilets A.; Duchene D.; Chagnon F.; Najmanovich R.; Leduc R.; Marsault E. Design and synthesis of potent, selective inhibitors of matriptase. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 2012, 37530–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng H.; Bannister T. D.; Jin L.; Babine R. E.; Quinn J.; Nagafuji P.; Celatka C. A.; Lin J.; Lazarova T. I.; Rynkiewicz M. J.; Bibbins F.; Pandey P.; Gorga J.; Meyers H. V.; Abdel-Meguid S. S.; Strickler J. E. Synthesis, SAR exploration, and X-ray crystal structures of factor XIa inhibitors containing an alpha-ketothiazole arginine. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2006, 16113049–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shia S.; Stamos J.; Kirchhofer D.; Fan B.; Wu J.; Corpuz R. T.; Santell L.; Lazarus R. A.; Eigenbrot C. Conformational lability in serine protease active sites: Structures of hepatocyte growth factor activator (HGFA) alone and with the inhibitory domain from HGFA inhibitor-1B. J. Mol. Biol. 2005, 34651335–1349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhatt A. S.; Welm A.; Farady C. J.; Vasquez M.; Wilson K.; Craik C. S. Coordinate expression and functional profiling identify an extracellular proteolytic signaling pathway. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2007, 104145771–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herter S.; Piper D. E.; Aaron W.; Gabriele T.; Cutler G.; Cao P.; Bhatt A. S.; Choe Y.; Craik C. S.; Walker N.; Meininger D.; Hoey T.; Austin R. J. Hepatocyte growth factor is a preferred in vitro substrate for human hepsin, a membrane-anchored serine protease implicated in prostate and ovarian cancers. Biochem. J. 2005, 390Pt 1125–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.