Abstract

Background

The mutually exclusive pattern of the major driver oncogenes in lung cancer suggests that other mutually exclusive oncogenes exist. We performed a systematic search for tyrosine kinase (TK) fusions by screening all TKs for aberrantly high RNA expression levels of the 3′ kinase domain (KD) exons relative to more 5′ exons.

Methods

We studied 69 patients (including 5 never smokers and 64 current or former smokers) with lung adenocarcinoma negative for all major mutations in KRAS, EGFR, BRAF, MEK1, and HER2, and for ALK fusions (termed “pan-negative”). A NanoString-based assay was designed to query the transcripts of 90 TKs at two points: 5′ to the KD and within the KD or 3′ to it. Tumor RNAs were hybridized to the NanoString probes and analyzed for outlier 3′ to 5′ expression ratios. Presumed novel fusion events were studied by rapid amplification of cDNA ends (RACE) and confirmatory RT-PCR and FISH.

Results

We identified 1 case each of aberrant 3′ to 5′ ratios in ROS1 and RET. RACE isolated a GOPC-ROS1 (FIG-ROS1) fusion in the former and a KIF5B-RET fusion in the latter, both confirmed by RT-PCR. The RET rearrangement was also confirmed by FISH. The KIF5B-RET patient was one of only 5 never smokers in this cohort.

Conclusion

The KIF5B-RET fusion defines an additional subset of lung cancer with a potentially targetable driver oncogene enriched in never smokers with “pan-negative” lung adenocarcinomas. We also report for the first time in lung cancer the GOPC-ROS1 fusion previously characterized in glioma.

Keywords: lung cancer, kinase, gene fusion, RET, ROS1, ALK

INTRODUCTION

The management of lung adenocarcinoma has been transformed by the discovery of targetable driver oncogenes such as EGFR mutations and ALK fusions [1, 2]. It has also become apparent that these major driver oncogenes, along with KRAS, HER2, and others, are mutually exclusive. Indeed, this remarkable, mutually exclusive pattern of mutations suggests that other, mutually exclusive driver oncogenes remain to be discovered. Based on extensive genotyping data generated by our group and others [3–5], it is estimated that 60–65% of lung adenocarcinomas in the U.S. contain one of the following known driver oncogenes, all mutually exclusive with rare exceptions: KRAS, EGFR, ALK fusion, BRAF, HER2, NRAS, MEK1. This pattern of mutations in over 60% of cases suggests a general dependence of lung adenocarcinoma on mutational activation of certain downstream signaling pathways (MAPK, AKT) and provides a rationale for a systematic screen of the remaining, “pan-negative” cases for other driver oncogenes. As part of such a screening effort, we have employed an RNA-based approach to systematically search for evidence of novel tyrosine kinase fusions in “pan-negative” lung adenocarcinomas.

The overall rationale for our exon-level mRNA-based screen for the detection of fusion genes is based on the observation that most gene fusions that lead to the formation of a chimeric fusion protein cause an intragenic discontinuity in the RNA expression level of the exons that are 5′ or 3′ to the fusion point in one or both of the fusion partners. This is attributable to the differences in the strength or activity of the promoters of the two translocation partner genes. Additionally, in some cases, the non-oncogenic, reciprocal fusion gene may be lost due to an unbalanced translocation event. We have recently demonstrated the successful application of this general strategy in the detection of gene fusions without prior knowledge of the genetic background of a given case, by identifying a novel, highly recurrent HEY1-NCOA2 fusion in the mesenchymal subtype of chondrosarcoma based on analysis of Affymetrix Exon Array data [6]. Here, we developed an efficient NanoString-based strategy that follows the same principle but is focused on tyrosine kinases as more immediately actionable gene fusions. We describe below how the application of this comprehensive NanoString-based assay for tyrosine kinases with outlier 5′ to 3′ expression ratios in “pan-negative” lung adenocarcinomas led to the identification of novel KIF5B-RET and GOPC-ROS1 fusions.

MATERIALS & METHODS

Assay Validation Samples and Negative Control Samples

To validate the performance of the NanoString assay design, we used cell lines and patient tumor samples with known fusions. The cell lines included H2228 and H3122 (both EML4-ALK+ lung adenocarcinomas), K299 (NPM1-ALK+ anaplastic large cell lymphoma), HCC78 (CD74-ROS1+ lung adenocarcinoma), and U118 (FIG-ROS1+ glioma). The patient tumor samples, tested under MSKCC IRB protocols as described in more detail below, included 75 lung adenocarcinoma samples of which 24 were positive for, and 51 were negative for, evidence of ALK fusion by ALK FISH and at least one other method, either EML4-ALK RT-PCR or IHC using the D5F3 ALK monoclonal antibody (Cell Signaling). As negative control samples to establish the range of normal 5′:3′ expression ratio variability for each gene in the NanoString assay, we included 17 KRAS-mutated lung adenocarcinomas, 11 EGFR-mutated lung adenocarcinomas, and 37 samples of non-neoplastic lung tissue procured at time of lung cancer surgery.

Discovery Samples

We identified 69 “pan-negative” lung adenocarcinomas with frozen tumor available for RNA extraction based on data from ongoing reflex clinical genotyping of resected lung adenocarcinomas at MSKCC. These samples were not selected for demographic features or smoking history and these data are listed in Supplementary Table 1. The summary of the data for these parameters are as follows: 64 smokers (50 former smokers including 5 with 5 pack-years or less, 14 current) and 5 never smokers (all female); 66 white non-Hispanic and 3 Hispanic or Black. There were no Asian patients in this study population. The genotyping process used to identify these samples as “pan-negative” for all known lung adenocarcinoma driver oncogenes is outlined in Figure 1, and briefly summarized here: tumor samples were subjected to extended molecular testing under MSKCC IRB protocols, consisting of a prospective screen for all recurrent mutations in 8 key genes (EGFR, HER2, KRAS, NRAS, BRAF, MEK1, PIK3CA, AKT1) in all lung adenocarcinomas using the Sequenom platform. The panel interrogates these 8 genes for the presence of 91 point mutations [4, 5]. EGFR exon 19 deletions, exon 20 insertions and HER2 exon 20 insertions were screened by PCR product sizing assays [7, 8]. Cases containing PIK3CA mutations, even as the sole detectable mutation, were not excluded because PIK3CA mutations are known to frequently co-occur with other driver mutations [9]. Cases negative with the preceding assays (except PIK3CA) were then screened by FISH for evidence of ALK fusions using the Abbott/Vysis ALK breakapart FISH assay.

Figure 1. Overall strategy for identification of “pan-negative” tumors for discovery of novel tyrosine kinase fusions.

Note that samples with PIK3CA mutations were not excluded from further analysis because of their known frequent overlap with other major driver mutations. See Materials and Methods for further details.

NanoString assay for kinase fusions

The NanoString nCounter system is a fluorescence-based platform to detect individual mRNA molecules without PCR amplification in a quantitative and highly multiplexed fashion [10, 11]. In this system, each capture probe and reporter probe together query a contiguous 100 bp region and only 100 ng RNA is needed per reaction. Our NanoString assay design (Figure 2) was based upon the known genomic properties of existing tyrosine kinase fusions, namely that these fusions invariably occur upstream of the exons encoding the kinase domain. The exons encoding the kinase domain GXGXXG motif for all 90 tyrosine kinases and 3 serine/threonine kinases (BRAF, ARAF, CRAF) were identified as described elsewhere [12]. All exons were labeled according to ENSEMBL numbering. Based on this mapping, two 100 bp regions were selected for each gene transcript, a 5′ probe pair located far upstream of the kinase domain exons, and the second located within those exons or further 3′. The 100 bp regions were selected to straddle exon boundaries to reduce the risk of interfering signal from genomic DNA. Detailed sequence information for all the kinase gene target regions is provided in Supplementary Table 2. Each sample was analyzed using 100 to 200 ng of total RNA per assay. All kinase genes and control genes were assayed simultaneously in multiplexed reactions. The raw data were normalized to the nCounter system spike-in positive and negative controls in each sample. The normalized results are expressed as the relative mRNA level. NanoString count data were converted to the log2 scale (1 was added to all data to avoid problems with zeros). The data were then normalized with the quantile method using the normalizeBetweenArrays procedure from the Bioconductor R-package. The 3′/5′ ratios were calculated for each kinase gene in the assay and samples with outlier ratios were visualized on log scale plots. Samples with specific tyrosine kinase genes with 3′/5′ ratios below −4 on the log2 scale were considered outliers if only seen in rare pan-negative samples and none of the other control samples.

Figure 2. Principle of NanoString assay for evidence of tyrosine kinase fusions.

As functional tyrosine kinase fusions invariably occur upstream of the exons encoding the kinase domain, probes were designed to measure the expression at two regions for each gene transcript, a 5′ probe pair located far upstream of the kinase domain exons, and the second located within those exons or further 3′. Kinase fusions often cause an imbalance in the RNA expression level of these two regions attributable to stronger activation of the promoter of the fusion partner gene and/or, in some cases, loss of the non-oncogenic, reciprocal fusion gene due to an unbalanced translocation event. The 3′/5′ expression ratios are calculated for each kinase gene in the assay and samples with outlier ratios were visualized on log scale plots.

5′ RACE

Rapid amplification of cDNA ends was performed with the use of 5′ RACE system (5′ system for Rapid Amplification of cDNA Ends, version 2.0, Invitrogen, CA). The primers used to identify aberrant ROS1 transcript in RNA in 5′ RACE reaction are ROS1-GSP1 primer (5′-GAGGAGACCTTCTTACTTATTT-3′) for cDNA synthesis and ROS1–GSP2 (5′-AAGACAAAGAGTTGGCTGAGCTGCG-3′) and ROS1-GSP3 (5′-CTGGCATAGAAGATTAAAGAATC-3′) for a nested PCR reaction. The primers used to identify aberrant RET transcript in RNA in 5′ RACE reaction are RET-GSP1 primer (5′-GATGAACGAGCTTCATCTCGGC-3′) for cDNA synthesis and RET-GSP 2 (5′-GACGTTGAACTCTGACAGCAGGTCTC-3′) and RET-GSP3 (5′-CTAGAGTTTTTCCAAGAACCAAGTTCTTC-3′) for the nested PCR reaction. For sequencing, the RACE PCR product was cloned using TOPO TA Cloning Kit (Invitrogen), purified with Qiaprep Spin Miniprep Kit (QIAGEN) and sequenced by Sanger sequencing.

RT-PCR for KIF5B-RET

To detect the presence of the KIF5B-RET fusion transcript, we performed RT-PCR using several independent sets of forward and reverse primers, in order to ensure that the RT-PCR products were short (<350bp). Specifically, primer pairs for RT-PCR were 5′-CTGAGATGATGGCATCTTTACTA-3′ (KIF5B_Ex15) with 5′-CTTGACCACTTTTCCAAATTC-3′ (RET_Ex12) and 5′-TGAGATTGATTCTGATGACACC-3′ (KIF5B_Ex23) with 5′-AGAGTTTTCCAAGAACCAAGT-3′ (RET_Ex12). Total RNA (500 ng) was reverse-transcribed to cDNA using Superscript II Reverse Transcriptase (Invitrogen). For cDNA Synthesis, we used the gene specific RET exon 14 reverse primer, 5′-CAGGGAGCCGTATTTGGCG-3′. cDNA (corresponding to 25 ng total RNA) was subjected to PCR amplification using HotStarTaq Master Mix Kit (QIAGEN, CA). The reactions were carried out in a thermal cycler under the following conditions: 35 cycles of 94°C for 1 min 57°C for 1 min and 72°C for 2 min, with a final extension for 7 min at 72°C. For sequencing, the RT-PCR product was cloned using TOPO TA Cloning Kit (Invitrogen), purified with Qiaprep Spin Miniprep Kit (QIAGEN) and sequenced by Sanger sequencing.

RET breakapart FISH assay

A RET breakapart FISH assay was developed using bacterial artificial chromosome (BAC) clones based on the UCSC Genome Browser database (http://genome.ucsc.edu/). BAC clones were ordered from the Children’s Hospital Oakland Research Institute (Oakland, CA). BAC DNAs were extracted using BACMAX DNA purification kit (Epicentre Biotechnologies, USA) and labeled with either SpectrumOrange-dUTP (red) or SpectrumGreen-dUTP (green) using the nick-translation kit (Vysis/Abbott Molecular, USA). RET 5′-probe, a combination of BAC clones RP11-633E1 and RP11-124O11, was labeled in green; RET 3′-probe, a combination of BAC clones RP11-718J13 and RP11-54P13 was labeled in red. Four-micron (4 μm) FFPE (Formalin-Fixed Paraffin-Embedded) sections generated from FFPE blocks of tumor specimens were pretreated by deparaffinizing in xylene and dehydrating in ethanol. Dual-color FISH was performed according to the protocol for FFPE sections from Vysis/Abbott Molecular with a few modifications. FISH analysis and signal capture were performed on a fluorescence microscope (Zeiss) coupled with ISIS FISH Imaging System (Metasystems). We analyzed 100 interphase nuclei from each tumor specimen.

RESULTS

NanoString assay validation

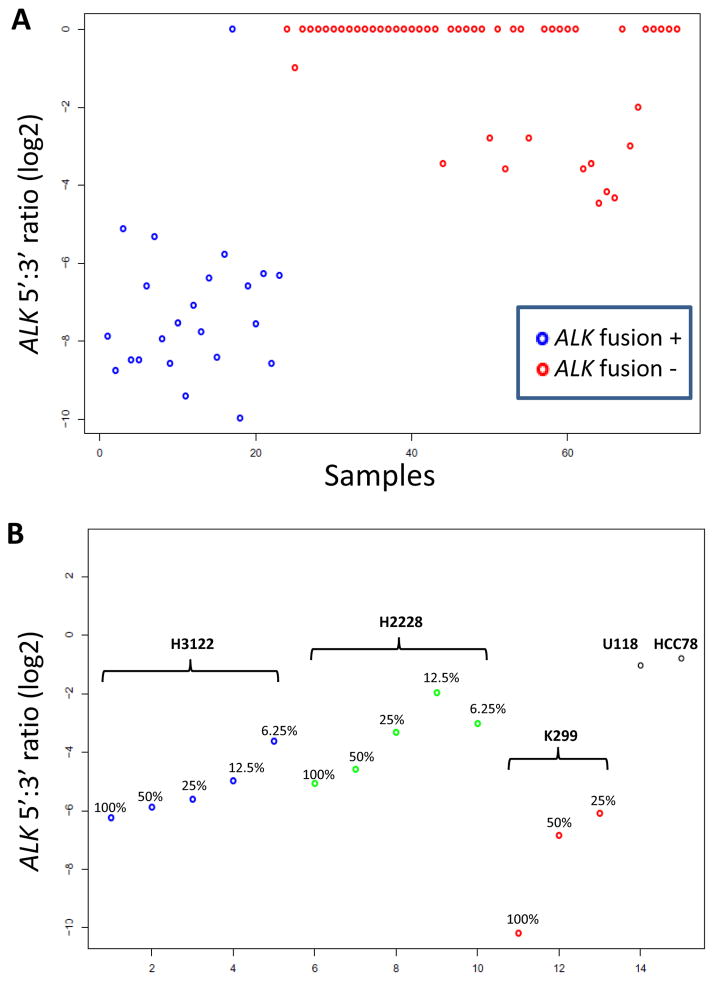

To evaluate the performance of the assay design for a known fusion, we studied 75 lung adenocarcinoma RNA samples (6 extracted from frozen tissue; 69 from FFPE blocks) of which 24 were positive for, and 51 were negative for, evidence of ALK fusion by ALK breakapart FISH and at least one other method, either EML4-ALK RT-PCR or IHC using the D5F3 ALK monoclonal antibody (Cell Signaling). The ALK 5′ to 3′ expression ratios were highly non-overlapping between the two groups, with 74/75 cases being correctly separated (Figure 3A). To gauge the sensitivity of the assay, we examined serial dilutions of RNAs from cell lines H2228, H3122 (both EML4-ALK+ lung adenocarcinomas) and K299 (NPM-ALK+ anaplastic large cell lymphoma), into RNA from the HL60 leukemia cell line (Figure 3B). We conservatively interpreted these results as suggesting that samples with at least 25% ALK-fusion positive tumor cell content should be readily detectable, an acceptable sensitivity range for a discovery assay. Other control samples that were appropriately positive included two ROS1 fusion-positive cell lines (HCC78, U118) (shown as negative controls for ALK in Figure 3B) and a papillary thyroid carcinoma sample with a known CCDC6-RET (“RET-PTC1”) fusion (not shown).

Figure 3. NanoString assay validation.

A. Detection of ALK fusions in lung adenocarcinoma samples using ALK 3′ to 5′ expression ratios. The lone discordant case had lower RNA quality and quantity compared to other samples. B. Serial dilutions of RNAs from cell lines with known ALK fusions. The U118 and HCC78 cell lines are shown as negative controls. Based on a cutoff of log2 ratio of −4, samples with at least 25% ALK-fusion positive tumor cell content should generally be detectable. e: exon.

Identification of ROS1 and RET fusions

We screened 90 tyrosine kinases and 3 RAF genes for aberrant 5′ to 3′ ratios in 69 pan-negative lung adenocarcinoma samples using this NanoString-based strategy. Examples of negative results plotted for other tyrosine kinases are shown in Supplementary Figure 1 for AXL, FGFR1, and MET. KRAS-mutated lung adenocarcinomas, EGFR-mutated lung adenocarcinomas, and samples of non-neoplastic lung tissue were also included as negative controls. We identified aberrant 5′ to 3′ ratios in ROS1 and RET in two cases (Figure 4), respectively, as described below.

Figure 4. NanoString Assay results for ROS1 and RET.

A & B. For both genes, the locations of the 5′ and 3′ probes are shown schematically, with the kinase domain indicated in red. Samples with outlier negative 5′:3′ ratios for ROS1 and RET are indicated by the arrows. These samples were subjected to 5′RACE leading to the identification of GOPC-ROS1 and KIF5B-RET fusions, respectively. The U118 and HCC78 cell lines are included in the ROS1 plot as positive controls. Neg: pan-negative lung adenocarcinomas (see text); KRAS: KRAS-mutated lung adenocarcinomas (n=17); EGFR: EGFR-mutated lung adenocarcinomas (n=11); normal: non-neoplastic lung tissue (n=37).

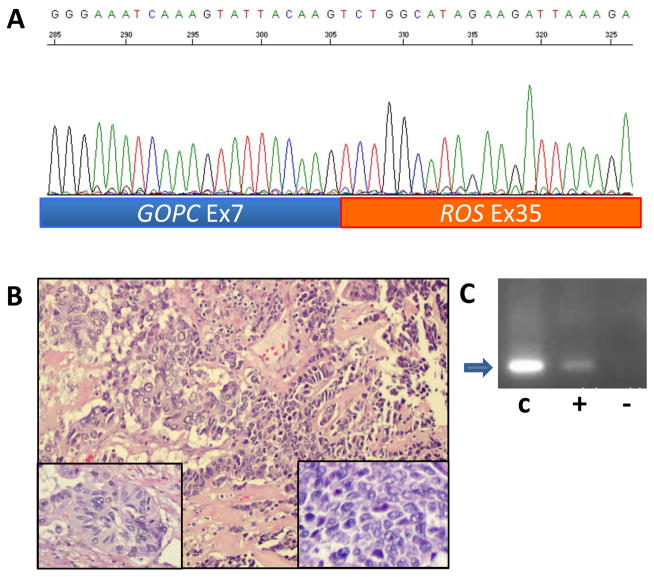

GOPC-ROS1 fusion

RACE analysis of the sample with the aberrant ROS1 5′ to 3′ ratio isolated a fusion of ROS1 to the Golgi-associated PDZ and coiled-coil motif containing (GOPC) gene, previously known as Fused in Glioblastoma (FIG) (Figure 5). This in-frame fusion of GOPC exon 7 to ROS1 exon 35 was also confirmed by an independent RT-PCR (Figure 5) and the RT-PCR product was also sequence-verified. This tumor was from a 68 year old white female former smoker with an 82 pack-year smoking history. Histologically, the tumor was a combined adenocarcinoma and small cell carcinoma (Figure 5). Routine diagnostic IHC studies showed that the small cell carcinoma component was positive for TTF-1 and CD56, and had a MIB1 proliferation rate of nearly 100%. The adenocarcinoma was weakly positive for CD56, and negative for TTF-1, Napsin-A, synaptophysin and chromogranin. Both components were negative for 4A4, 34BE12, and CK5/6, supporting the diagnosis. This patient’s stage IIIA lung cancer was resected in August 2010, followed by adjuvant cytotoxic chemotherapy completed by December 2010, without subsequent recurrence.

Figure 5. Identification of GOPC-ROS1 fusion.

A. Sequence of product of 5′RACE shows an in-frame fusion of GOPC exon 7 to ROS1 exon 35 in this cancer from a 68 year old white female with a 82 pack-year smoking history. B. Histology shows a combined small cell and adenocarcinoma. The adenocarcinoma component (left portion of field) is poorly differentiated with solid and acinar growth patterns (left inset). The small cell component of the tumor (right portion of field) is composed of organoid nests and trabeculae of densely packed cells with scant cytoplasm (right inset). The nuclei are spindle and angulated with finely granular chromatin and inconspicuous nucleoli (right inset). There is marked tumor necrosis and brisk mitotic activity in both components. C. RT-PCR confirmation of GOPC-ROS1 fusion. Lane C shows the positive control product (arrow) in the U188 cell line RNA. Lane “+” shows the same product in the tumor RNA. The RT-PCR product was also sequence-verified. Lane “−” is a negative control showing a lack of product in the tumor RNA when the RT is omitted.

KIF5B-RET fusion

RACE analysis of the sample with the most aberrant RET 5′ to 3′ ratio isolated a fusion of RET to the kinesin family 5B gene (KIF5B) (Figure 6). This in-frame fusion of KIF5B exon 15 to RET exon 12 was likewise also confirmed by sequencing of independent RT-PCR products. This patient was a 60 year old female never smoker, and the tumor was a 2.8 cm adenocarcinoma with predominantly papillary and acinar growth patterns with some solid and micropapillary components (Figure 6). The tumor nuclei displayed frequent and prominent intranuclear inclusions. In routine diagnostic IHC studies, the tumor cells were positive for CK7, TTF-1 and PE10 and negative for CK20 and thyroglobulin, consistent with pulmonary origin. Using BAC clones, we developed a FISH assay for RET rearrangement (see Methods). This showed narrow but consistent split signals in the tumor nuclei from this case (Figure 6), consistent with the signal pattern of an intra-chromosomal rearrangement such as the inversion between KIF5B and RET that would generate this gene fusion. This patient’s small, incidentally detected adenocarcinoma was resected in March 2009 without subsequent recurrence or treatment.

Figure 6. Identification of KIF5B-RET fusion.

A. Sequence of product of 5′RACE shows an in-frame fusion of KIF5B exon 15 to RET exon 12 in this cancer from a 60 year old never smoker white female. B. Histology shows lung adenocarcinoma with predominantly papillary and acinar growth patterns (left). Nuclei are pleomorphic and display prominent intranuclear pseudoinclusions (right). C. FISH analysis shows splitting of green (5′probe) and red (3′probe) signals of RET breakapart FISH assay. Inset: normal bone marrow cells showing fused or overlapping red and green signals only.

Further screening by RT-PCR for KIF5B-RET using multiple primer combinations (see Methods) did not identify any additional positive samples in 48 of the remaining 68 samples NanoString study set with sufficient material for RT-PCR.

DISCUSSION

The discovery of ALK fusions in lung adenocarcinoma in 2007 resulted in renewed interest in kinase fusions as oncogenic drivers in common solid cancers [13, 14]. Soon thereafter, based on marked tumor shrinkages observed in patients with ALK rearrangements in a phase 1 trial of crizotinib, a cohort of patients with ALK rearrangements was added and showed an overall response rate of 61% with a median response duration of 12 months and a subsequent phase 2 trial of patients with ALK-fusion-positive lung adenocarcinomas found a radiographic response rate > 50% [15]. Together, these studies led to the accelerated approval of crizotinib by the US FDA in August 2011 for this molecular subset defined by a novel kinase fusion [16, 17]. These recent developments prompted us to design and perform a more systematic screen for kinase fusions in lung adenocarcinomas without a currently known oncogenic driver, i.e. “pan-negative” lung adenocarcinomas.

Using the present NanoString-based assay to screen 69 “pan-negative” lung adenocarcinomas for evidence of fusions involving 90 tyrosine kinase genes, we identified novel ROS1 and RET fusions in two samples. This may suggest that undiscovered tyrosine kinase fusions are unlikely to account for many or most “pan-negative” lung adenocarcinomas. However, we acknowledge that there are limitations to the present assay design: the sensitivities for detecting outlier 5′ to 3′ ratios may be variable based on the expression level of the fusion gene and the expression level of the native gene in non-neoplastic cells. Furthermore, it is likely that additional 5′ and 3′ probes for each gene would allow more robust scoring of outlier 5′ to 3′ ratios. As with any high throughput genomic technology, it is not possible to experimentally validate the performance of the assay for each of the genes tested. There are also advantages to this NanoString-based assay, notably it extends the analyzable sample types beyond the high quality samples usually required for array-based platforms or next generation sequencing-based chimeric transcript detection and is, therefore, well suited to limited clinical sample RNAs (100–200ng) of variable quality extracted from either frozen tissues or formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tumor blocks. It is also relatively cost-efficient (approximately $200/sample). Our validation studies and successful identification of two novel fusions support this type of assay as a discovery platform but considerable additional validation studies would be needed to establish this as a clinical diagnostic platform for one or more tyrosine kinase fusions. Nonetheless, the labor-intensive, inherently low-throughput nature of FISH makes screening for multiple possible fusion genes (ALK, ROS1, RET) cumbersome and will drive the search for more multiplexed diagnostic approaches such as this one or others.

We have identified for the first time the fusion of ROS1 with GOPC, previously known as FIG, in a lung adenocarcinoma. Although karyotype data were not available in our case, these two genes are only 134 KB apart in the same orientation at 6q22 so this fusion is consistent with an intra-chromosomal deletion, namely del(6)(q22q22). The GOPC-ROS1 fusion has previously only been found in the U118MG human glioblastoma multiforme cell line [18]. The GOPC-ROS1 fusion protein has been shown to have constitutively active kinase activity and its transforming potential has been demonstrated in a mouse transgenic model where it resulted in glioblastomas in an Ink4a;Arf-null background [19]. ROS1 fusions in lung cancer, specifically SLC34A2-ROS1 and CD74-ROS1, were first reported by Rikova et al in 2007 [13]. Interestingly, additional ROS1 fusion partners reported since then in lung cancer have included TPM3, SDC4, EZR, and LRIG3, but not GOPC [20]. All six lung cancer ROS1 fusions tested by Takeuchi and colleagues were found to be transforming in 3T3 cells (20). Together, these data strongly support ROS1 fusions as driver events, even as possible subtle functional differences among the many related ROS1 fusions described in lung cancer remain to be explored in lung epithelial cells or transgenic mouse models in future studies.

This molecular subset of lung adenocarcinoma is of immediate clinical interest given the activity of crizotinib for this target, recently demonstrated in cell line experiments and clinically in a single ROS1 FISH-positive patient who experienced a complete response to this agent [21]. The expansion of the possible ROS1 fusion partners in lung cancer to GOPC further underscores the heterogeneity of ROS1 fusions and the difficulty in using RT-PCR assays for comprehensive detection of these patients. The size of this molecular subset among lung adenocarcinomas was 1.2% (13/1116) in one study [20], 2.6% (18/644) in a second study [21], and 1.5% (2/152) in a third study limited to Asian never smokers [22]. In the present study, we found it in 1/69 “pan-negative” lung adenocarcinomas, which in our testing experience make up about 40% of lung adenocarcinomas, and therefore our overall prevalence of ROS1 fusions would be approximately 0.6%. It should be noted that certain breakapart FISH assay designs for ROS1 fusions would fail to detect the GOPC-ROS1 fusion because their 5′ probe overlaps or includes GOPC which is only 134 KB upstream and therefore no significant change in FISH signal patterns would be apparent. This is the case with a commercially available assay (Abnova) as well as the assay used by Bergethon and colleagues [21]. Therefore, studies based on such FISH assays may underestimate the prevalence of ROS1 fusions by missing GOPC-ROS1 cases. In contrast, the 5′ ROS1 probe used by Takeuchi and colleagues [20] includes the 5′ end of ROS1 and the region between ROS1 and GOPC and therefore a GOPC-ROS1 fusion case may show just a loss of the 5′ ROS1 probe in such an assay design due to the genomic interstitial deletion. If the GOPC-ROS1 fusion occurs by a more complex mechanism such as an insertion/duplication, it may not be detectable by any of these ROS1 FISH assays. Finally, we should note that, while the present paper was under review, another group has reported the detection of a GOPC-ROS1 fusion in lung cancer using immunohistochemistry for ROS1 as a screening approach [23].

More recently, as the present report was in preparation, several independent groups [20, 24–26] also reported the discovery of KIF5B-RET fusions in lung adenocarcinomas, at an overall prevalence of approximately 1.3% [27]. Based on the same estimates provided above for ROS1 fusions, our overall prevalence of RET fusions would be approximately 0.6%. Notably, our KIF5B-RET-positive tumor was detected in one of only 5 never smokers in our discovery set, suggesting that screening of “pan-negative” never smokers may be a more efficient strategy to identify this rather small subset of patients. It is possible that more cases with kinase fusions might have been detected if our study group had been intentionally enriched for never smokers. Our KIF5B-RET fusion involved exon 15 of KIF5B and exon 12 of RET, thus retaining a portion of the dimerization domain of KIF5B and the entire kinase domain of RET, analogous to RET fusions in papillary thyroid carcinoma. This fusion structure is also the most commonly reported of the seven isoforms described so far [21]. Cytogenetically, since KIF5B and RET are approximately 10.6 Mb apart on chromosome 10 in opposite orientations, the KIF5B-RET fusion may occur most simply by a pericentric inversion of 10p11.22-q11.21. RET is a well-established oncogene in thyroid cancer, both in the context of point mutations in medullary thyroid cancer and other fusions in papillary thyroid cancer [28]. The oncogenic potential of KIF5B-RET itself has been established by transfection of NIH 3T3 cells in which it leads to anchorage-independent growth in vitro and tumor formation in xenografted mice [20, 25] and by transfection of Ba/F3 cells in which it results in interleukin-3-independent growth [20, 24]. Although no human lung cancer cell line with an endogenous KIF5B-RET fusion has been identified, the phenotypes elicited in heterologous cells by transfection with KIF5B-RET cDNA are sensitive to multi-kinase inhibitors whose targets include RET, such as vandetanib, sunitinib, and sorafenib [20, 24, 25], supporting the concept of prospectively genotyping lung cancers for RET fusions to identify patients for clinical trials of such agents in this new molecular subset of lung adenocarcinoma. It is interesting to note that agents such as sunitinib [29, 30], sorafenib [31] and cabozantinib (a.k.a. XL184) in unselected non-small cell lung cancer patients have been associated with partial response rates in the 2–10% range. Given the multi-kinase targeting of these agents, it has been difficult to elucidate why some patients benefit but it is now tempting to speculate that some of these partial responses may have been in tumors containing a RET fusion.

Finally, it is notable that the two most common lung fusions so far, EML4-ALK and KIF5B-RET, are both intrachromosomal events, as is the only other RET fusion described so far in lung cancer, CCDC6-RET, reported in one case by Takeuchi et al. [20]. Although most ROS1 fusion partners are on other chromosomes, the GOPC-ROS1 fusion reported here and another recently described ROS1 fusion, EZR-ROS1 [20], are also intrachromosomal rearrangements. These observations are intriguing given the link between radiation and intrachromosomal rearrangements established in papillary thyroid cancer based on epidemiologic and mechanistic data. Specifically, papillary thyroid cancers that develop following nuclear disasters are more likely to harbor RET rearrangements (instead of BRAF or RAS mutations) [32, 33] and the fusion partners are more often CCDC6 (“RET-PTC1” fusion) and NCOA4 (“RET-PTC3” fusion), both on chromosome 10 [32]. RET fusions can be induced in vitro by irradiating human thyroid epithelial cells and these three chromosome 10 loci (RET, CCDC6, NCOA4) are often juxtaposed in the interphase nuclei of thyroid epithelial cells, which may facilitate coincident DNA strand breakage by a single radiation track and/or illegitimate recombination [34–36]. These considerations, along with the increased risk of lung cancer in atomic bomb survivors and uranium miners [37, 38], suggest that a possible etiologic role for environmental radiation should be explored in never smokers whose tumors harbor KIF5B-RET or possibly EML4-ALK.

Supplementary Material

TRANSLATIONAL RELEVANCE.

The identification of druggable driver oncogenes such as mutated EGFR and HER2 and ALK fusions represents a major advance in the therapy of lung adenocarcinoma. However, the majority of lung adenocarcinoma patients still do not have a targeted treatment option. Here, we focused on lung adenocarcinoma patients without any identifiable driver oncogenes to search for new potential targets. In this enriched patient population, we used a NanoString based strategy to search for new tyrosine kinase fusion genes. With this approach we identified and confirmed 1 case each of a novel KIF5B-RET fusion and a GOPC-ROS1 (FIG-ROS1). Although RET and ROS1 fusions represent small percentages of lung adenocarcinoma, they are of immediate clinical interest. ROS1 fusions have been shown to respond clinically to targeted treatment with crizotinib and preclinical data suggest that RET fusions should respond to RET inhibitors.

Acknowledgments

Financial support: NIH P01 CA129243 (to M.L.), Uniting Against Lung Cancer (to M.L.), International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer Fellowship (to A.D.)

We thank William Pao and Juliann Chmielecki for sharing lung cancer cell lines and bioinformatic data on tyrosine kinase genes, James Fagin for advice and providing RNA from a CCDC6-RET-positive thyroid cancer, Laetitia Borsu and Adriana Heguy for assistance with the NanoString platform, and Cameron Brennan for providing U118 cell line RNA.

Footnotes

Potential conflicts of interest: none to declare

Reference List

- 1.Pao W, Iafrate AJ, Su Z. Genetically informed lung cancer medicine. J Pathol. 2011;223:230–40. doi: 10.1002/path.2788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pao W, Girard N. New driver mutations in non-small-cell lung cancer. Lancet Oncol. 2011;12:175–80. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(10)70087-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Johnson BE, Kris MG, Kwiatkowski DJ, Iafrate AJ, Wistuba II, Shyr Y, et al. Clinical characteristics of planned 1000 patients with adenocarcinoma of lung (ACL) undergoing genomic characterization in the US Lung Cancer Mutation Consortium (LCMC) J Thorac Oncol. 2011;6:S346. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Arcila ME, Lau C, Jhanwar SC, Zakowski MF, Kris MG, Ladanyi M. Comprehensive analysis for clinically relevant oncogenic driver mutations in 1131 consecutive lung adenocarcinomas. Mod Pathol. 2011;24s1:404A. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kris MG, Arcila M, Lau C, Rekhtman N, Brzostowski E, Pilloff M, et al. Two year results of LC-MAP: an institutional program to routinely profile tumor specimens for the presence of mutations in targetable pathways in all patients with non-small cell lung cancers. J Thorac Oncol. 2011;6:S347. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang L, Motoi T, Khanin R, Olshen A, Mertens F, Bridge J, et al. Identification of a novel, recurrent HEY1-NCOA2 fusion in mesenchymal chondrosarcoma based on a genome-wide screen of exon-level expression data. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2012;51:127–39. doi: 10.1002/gcc.20937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Su Z, Dias-Santagata D, Duke M, Hutchinson K, Lin YL, Borger DR, et al. A platform for rapid detection of multiple oncogenic mutations with relevance to targeted therapy in non-small-cell lung cancer. J Mol Diagn. 2011;13:74–84. doi: 10.1016/j.jmoldx.2010.11.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pan Q, Pao W, Ladanyi M. Rapid PCR-based detection of epidermal growth factor receptor gene mutations in lung adenocarcinomas. J Mol Diagn. 2005;7:396–403. doi: 10.1016/S1525-1578(10)60569-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chaft JE, Arcila ME, Paik PK, Lau C, Riely GJ, Pietanza MC, et al. Coexistence of PIK3CA and other oncogene mutations in lung adenocarcinoma-rationale for comprehensive mutation profiling. Mol Cancer Ther. 2012;11:485–91. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-11-0692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Reis PP, Waldron L, Goswami RS, Xu W, Xuan Y, Perez-Ordonez B, et al. mRNA transcript quantification in archival samples using multiplexed, color-coded probes. BMC Biotechnol. 2011;11:46, 46. doi: 10.1186/1472-6750-11-46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Payton JE, Grieselhuber NR, Chang LW, Murakami M, Geiss GK, Link DC, et al. High throughput digital quantification of mRNA abundance in primary human acute myeloid leukemia samples. J Clin Invest. 2009;119:1714–26. doi: 10.1172/JCI38248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chmielecki J, Peifer M, Jia P, Socci ND, Hutchinson K, Viale A, et al. Targeted next-generation sequencing of DNA regions proximal to a conserved GXGXXG signaling motif enables systematic discovery of tyrosine kinase fusions in cancer. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:6985–96. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rikova K, Guo A, Zeng Q, Possemato A, Yu J, Haack H, et al. Global survey of phosphotyrosine signaling identifies oncogenic kinases in lung cancer. Cell. 2007;131:1190–203. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.11.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Soda M, Choi YL, Enomoto M, Takada S, Yamashita Y, Ishikawa S, et al. Identification of the transforming EML4-ALK fusion gene in non-small-cell lung cancer. Nature. 2007;448:561–6. doi: 10.1038/nature05945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kwak EL, Bang YJ, Camidge DR, Shaw AT, Solomon B, Maki RG, et al. Anaplastic lymphoma kinase inhibition in non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:1693–703. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1006448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Riely GJ, Chaft JE, Ladanyi M, Kris MG. Incorporation of crizotinib into the NCCN guidelines. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2011;9:1328–30. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2011.0113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gerber DE, Minna JD. ALK inhibition for non-small cell lung cancer: from discovery to therapy in record time. Cancer Cell. 2010;18:548–51. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2010.11.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Charest A, Lane K, McMahon K, Park J, Preisinger E, Conroy H, et al. Fusion of FIG to the receptor tyrosine kinase ROS1 in a glioblastoma with an interstitial del(6)(q21q21) Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2003;37:58–71. doi: 10.1002/gcc.10207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Charest A, Wilker EW, McLaughlin ME, Lane K, Gowda R, Coven S, et al. ROS1 fusion tyrosine kinase activates a SH2 domain-containing phosphatase-2/phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/mammalian target of rapamycin signaling axis to form glioblastoma in mice. Cancer Res. 2006;66:7473–81. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-1193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Takeuchi K, Soda M, Togashi Y, Suzuki R, Sakata S, Hatano S, et al. RET, ROS1 and ALK fusions in lung cancer. Nat Med. 2012;18:378–81. doi: 10.1038/nm.2658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bergethon K, Shaw AT, Ignatius OuSH, Katayama R, Lovly CM, McDonald NT, et al. ROS1 Rearrangements Define a Unique Molecular Class of Lung Cancers. J Clin Oncol. 2012 doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.35.6345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li C, Fang R, Sun Y, Han X, Li F, Gao B, et al. Spectrum of oncogenic driver mutations in lung adenocarcinomas from East Asian never smokers. PLoS ONE. 2011;6:e28204. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0028204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rimkunas VM, Crosby KE, Li D, Hu Y, Kelly ME, Gu TL, et al. Analysis of Receptor Tyrosine Kinase ROS1-Positive Tumors in Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer: Identification of a FIG-ROS1 Fusion. Clin Cancer Res. 2012;18:4449–57. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-3351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lipson D, Capelletti M, Yelensky R, Otto G, Parker A, Jarosz M, et al. Identification of new ALK and RET gene fusions from colorectal and lung cancer biopsies. Nat Med. 2012;18:382–4. doi: 10.1038/nm.2673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kohno T, Ichikawa H, Totoki Y, Yasuda K, Hiramoto M, Nammo T, et al. KIF5B-RET fusions in lung adenocarcinoma. Nat Med. 2012;18:375–7. doi: 10.1038/nm.2644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ju YS, Lee WC, Shin JY, Lee S, Bleazard T, Won JK, et al. A transforming KIF5B and RET gene fusion in lung adenocarcinoma revealed from whole-genome and transcriptome sequencing. Genome Res. 2012;22:436–45. doi: 10.1101/gr.133645.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pao W, Hutchinson KE. Chipping away at the lung cancer genome. Nat Med. 2012;18:349–51. doi: 10.1038/nm.2697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Castellone MD, Santoro M. Dysregulated RET signaling in thyroid cancer. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 2008;37:363–74. viii. doi: 10.1016/j.ecl.2008.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Socinski MA, Novello S, Brahmer JR, Rosell R, Sanchez JM, Belani CP, et al. Multicenter, phase II trial of sunitinib in previously treated, advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:650–6. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.13.9303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Novello S, Scagliotti GV, Rosell R, Socinski MA, Brahmer J, Atkins J, et al. Phase II study of continuous daily sunitinib dosing in patients with previously treated advanced non-small cell lung cancer. Br J Cancer. 2009;101:1543–8. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6605346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Scagliotti G, Novello S, von PJ, Reck M, Pereira JR, Thomas M, et al. Phase III study of carboplatin and paclitaxel alone or with sorafenib in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:1835–42. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.26.1321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nikiforov YE, Rowland JM, Bove KE, Monforte-Munoz H, Fagin JA. Distinct pattern of ret oncogene rearrangements in morphological variants of radiation-induced and sporadic thyroid papillary carcinomas in children. Cancer Res. 1997;57:1690–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hamatani K, Eguchi H, Ito R, Mukai M, Takahashi K, Taga M, et al. RET/PTC rearrangements preferentially occurred in papillary thyroid cancer among atomic bomb survivors exposed to high radiation dose. Cancer Res. 2008;68:7176–82. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-0293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nikiforov YE, Koshoffer A, Nikiforova M, Stringer J, Fagin JA. Chromosomal breakpoint positions suggest a direct role for radiation in inducing illegitimate recombination between the ELE1 and RET genes in radiation-induced thyroid carcinomas. Oncogene. 1999;18:6330–4. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nikiforova MN, Stringer JR, Blough R, Medvedovic M, Fagin JA, Nikiforov YE. Proximity of chromosomal loci that participate in radiation-induced rearrangements in human cells. Science. 2000;290:138–41. doi: 10.1126/science.290.5489.138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gandhi M, Evdokimova V, Nikiforov YE. Mechanisms of chromosomal rearrangements in solid tumors: the model of papillary thyroid carcinoma. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2010;321:36–43. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2009.09.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ozasa K, Shimizu Y, Suyama A, Kasagi F, Soda M, Grant EJ, et al. Studies of the mortality of atomic bomb survivors, report 14, 1950–2003: an overview of cancer and noncancer diseases. Radiat Res. 2012;177:229–43. doi: 10.1667/rr2629.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rage E, Vacquier B, Blanchardon E, Allodji RS, Marsh JW, Caer-Lorho S, et al. Risk of Lung Cancer Mortality in Relation to Lung Doses among French Uranium Miners: Follow-Up 1956–1999. Radiat Res. 2012;177:288–97. doi: 10.1667/rr2689.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.